1. Introduction

Vaccine hesitancy is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite the availability of vaccination services” [

1,

2]. Studies in India (36%), Canada (20%), and the United States (25%) have published population-based studies on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy demonstrating that the factors that are responsible for vaccine hesitancy range from social demographics, occupation, religious beliefs, and social and environmental trust [

2,

3,

4].

Trust is a very important factor in the study of factors influencing vaccine hesitancy. A literature review of European studies from 2006 to 2014 reveals that the main concern over the decade was vaccine safety [

5]. Taylor et al. revealed that vaccine refusal was strongly associated with vaccine distrust [

6]. Under the condition of the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccination intention has been shown to be positively associated with the perceived persistence of SARS-CoV-2 [

7]. In addition, to determine the best way to increase influenza vaccination rates, the confidence in physicians and national health departments was assessed in 2018 [

8,

9]. Health-care providers are a key part in influencing public trust in scientific and epidemiological evidence [

10]. Overall, regarding the trust and factors that influence vaccine hesitancy behavior among a population, the literature studies have generally focused on health professionals and trust in vaccines, such as infectious disease specialists, medical personnel, policymakers, governments, and vaccine provider systems.

Numerous researchers have constructed models of the factors influencing the phenomenon of vaccine hesitancy, and the classification of trust has been elaborated and refined. In 2015, the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization grouped the factors into the following three aspects: (1) contextual factors, (2) individual and group influences, and (3) vaccine- or vaccination-specific issues [

11]. Many Indian scholars have also analyzed and summarized the model of factors influencing vaccine hesitancy. Umakanthan et al. found that vaccine hesitancy is comprehensive and context-specific [

2]. Zhang et al. suggested that vaccine hesitancy is influenced by confidence, that is, by trust in the efficacy and safety of the vaccine and in the health service system that provides it [

12]. Xu et al. classified the factors influencing vaccine hesitancy into social environmental, individual or group, and vaccination service factors [

13]. Yu et al. developed a framework of influences on vaccination based on the Indian population, categorizing the influences as vaccine confidence and accessibility [

11] factors [

13].

Regarding the factors influencing the phenomenon of vaccine hesitancy, trust in the vaccine itself is the focus of research, whereas research on trust in the environment other than the vaccine mainly remains at the theoretical level. In terms of trust in the environment, researchers have focused more on trust in government policies and medical personnel, whereas there are fewer studies worldwide on community and family factors mentioned by Indian researchers. Therefore, the trust in government and medical personnel, being part of the environment trust, was taken as the research object and defined as “trust in the social environment” to distinguish it from trust in the community and family. In addition, trust in the vaccine itself and trust in the social environment (including trust in the government and in medical personnel), being parts of the trust that influences vaccination intention, were included as the subjects. The following research hypotheses were formulated:

H1a. There is a significant positive association between trust in vaccines (safety and efficacy) and vaccination intention toward COVID-19 vaccines.

H1b. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a significant positive association between trust in the social environment (including government and medical personnel) and vaccination intention for COVID-19 vaccines.

Since the emergence of the concept of vaccine hesitancy, the media has received research attention for its influence on vaccine hesitancy. Umakanthan’s model of vaccine hesitancy includes trust in communication and media, and the media included traditional media, the Internet, and social media and anti-vaccination activists [

2]. Some findings suggest that social media may be an effective intervention tool to help parents to make informed decisions about vaccination for their children [

14]. Social media applications have a positive impact on people’s vaccination behavior by being informed about vaccines [

15]. The Internet is an important source for Canadian parents to find and share information about vaccines and is significantly associated with negative parental perceptions of vaccine risks [

16]. Studies in India have also confirmed that information reception from the media has a significant impact on vaccination intention. Studies on the influenza A vaccine have demonstrated that news involvement has a significant positive effect on the level of understanding [

17]. Studies on HPV vaccination intention suggest that media exposure does influence intention to receive the vaccine [

18]. In addition, some studies have explored the impact of benefit targets in health communication strategies on influenza vaccination behavior in college student populations [

19].

Currently, studies on information reception in relation to vaccine hesitancy are mainly categorized based on media channels. However, in the Internet environment, multiple sources with different identities coexist in each media channel and simultaneously disseminate the vaccine information. Therefore, the identities of information disseminators should be considered to optimize the way current researchers categorize information sources. This study classified the sources of information reception into two categories, official and unofficial sources, and proposes the following research hypotheses using authority as a classification criterion.

H2a. There is a significant positive correlation between exposure to information (official sources) and vaccination intention for COVID-19 vaccines.

H2b. There is a significant negative correlation between exposure to information (unofficial sources) and vaccination intention for COVID-19 vaccines.

It has been revealed that different sources of information affect people’s degree of trust. The public is more impressed with information from media sources, such as television and the Internet, and trusts information from “friends and family” sources [

20] more. The largest source of information about breaking news is news websites, and trust in this source is generally higher [

21]. People’s degree of trust in different sources varies. Netizens have the highest trust in national media network platforms and local government websites [

22]. There is a positive correlation between the interpersonal communication or social media use and trust in rumors on the pandemic during the COVID-19 pandemic [

23]. This study proposed the following research hypotheses on the relationship between information exposure and trust among various aspects:

H3a. There is a significant positive association between exposure to media information (official sources) and trust in COVID-19 vaccines.

H3b. There is a significant positive association between exposure to media information (unofficial sources) and trust in COVID-19 vaccines.

H3c. There is a significant positive relationship between exposure to media information (official sources) and trust in the social environment.

H3d. There is a significant positive relationship between exposure to media information (unofficial sources) and trust in the social environment.

Several studies have found that trust is a mediator in the relationship between exposure to media and behavioral intention. Political trust has been shown to be a mediating variable between exposure to media and subjective well-being [

24]. Using a health belief model as a mediator, a study determined that both social media expression and acceptance were effective in encouraging enhanced health intention, but only by increasing self-efficacy and perceptions of severity [

25]. In addition, Indian adult women’s exposure to social health information and media-based health information using WeChat increased their psychological expectation of HPV vaccination behavior, which, in turn, contributes to the intention of HPV vaccination behavior [

26]. Based on the above theory and research practice, this study presented the following hypothesis:

H4. Trust among vaccines and social environment mediates between information reception and willingness to be vaccinated.

In the research framework of this study, the independent variables are the different sources of information reception, which are classified into two categories: official sources and unofficial sources using authority as the classification criterion. The mediating variable is trust, which is divided into trust in vaccines and in the social environment. The dependent variable is vaccination intention.

Data were collected by questionnaires to first conduct a descriptive analysis of the current situation of the study population in terms of information reception about the COVID-19 vaccine from various sources and the current situation of trust from all sides and vaccination intention behaviors. On this basis, the correlations between the reception from different sources and trust or vaccination intention and the correlation between different categories of trust and vaccination intention were explored. Whether trust in the safety and efficacy of the vaccine and trust in the social environment were the mediating factors between the information reception from different sources and vaccination intention was then analyzed.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have revealed significant vaccine hesitancy in the United States and Canada [

7]. In previous studies using the vaccine hesitancy model, researchers have typically focused on the trust in vaccines, such as the trust in their safety and efficacy [

7,

8,

9]. The current study presented a different picture of vaccine hesitancy in India; people’s perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine are favorable, and vaccine hesitancy has not been widespread. This confirms that trust in the social environment plays an important role in influencing people’s conduct in terms of health protection from the perspective of the prevention and control of COVID-19. Thus, exploring the strengths of India’s vaccination policies and information dissemination strategies may provide an opportunity to inform global vaccination efforts and contribute to global pandemic prevention and control. Previous studies have suggested that interpersonal communication and the dissemination of information on social media exacerbate people’s trust in false information [

23]. In contrast, this study demonstrated that unofficial sources are also indispensable health information publishers and disseminators during the current pandemic, and they help people to increase social trust and thus proactively engage in scientific health protection. In previous studies, trust has always been a mediator of interest in the relationship between behavior and intention. In addition, research on the mediators of information reception and vaccination intention has been mainly limited to the trust in the vaccine itself (safety, efficacy) [

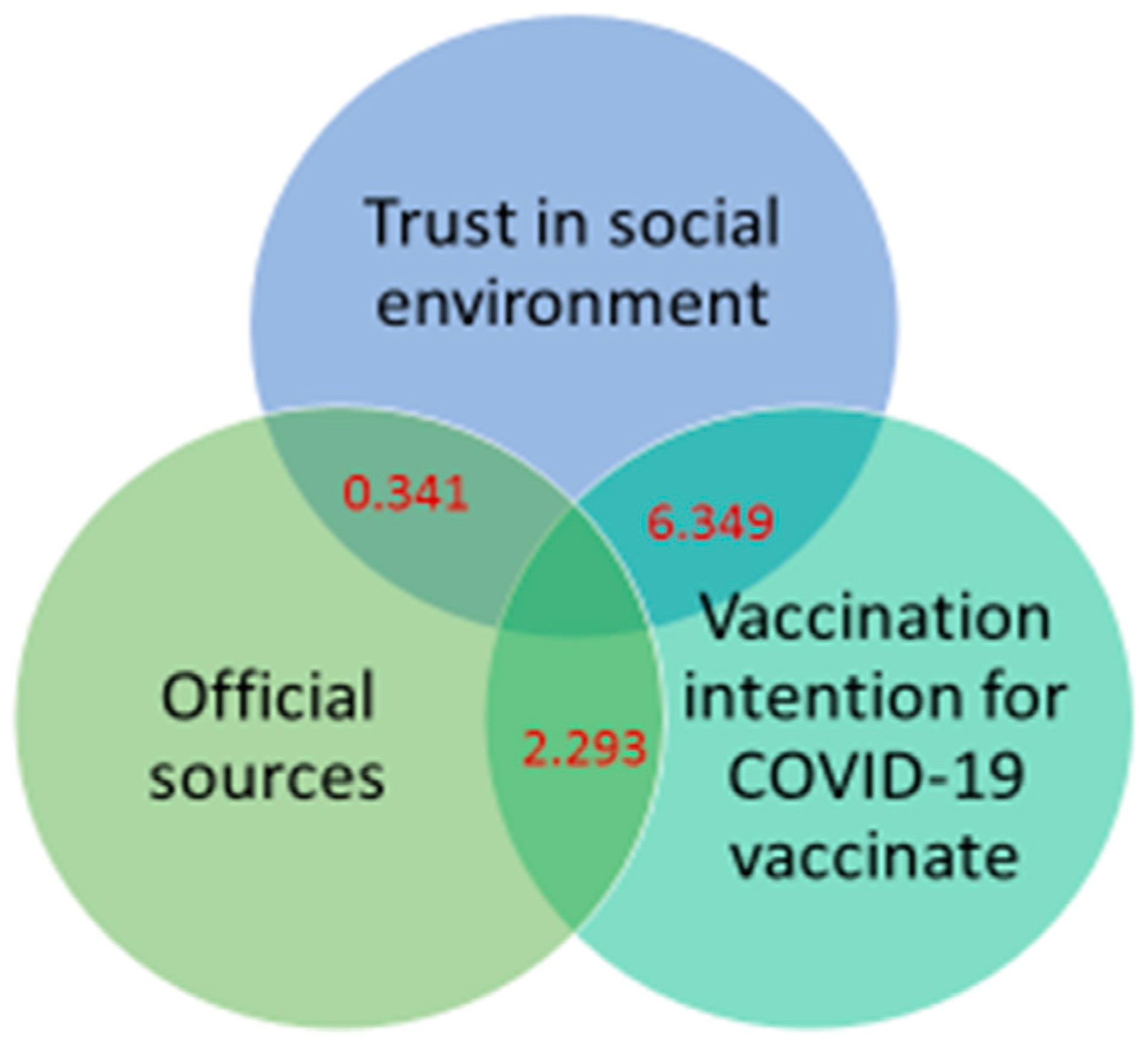

28], with little consideration of trust in the social environment. Against the background of the special environment of India, this study demonstrated that trust in the environment is an important channel linking people’s information reception and vaccination intention and taps into a new pathway for health information dissemination (as presented in

Figure 1).

Based on the above findings, this study expects to provide new ideas for health communication research. First, the perception of environment is an important basis for public health actions, which can significantly influence people’s health actions. The trust in the environment drives people to take active and effective health protection initiatives. This expands the theoretical research horizon of health communication and broadens the dimension of research on health communication paths.

Second, the source of information is an important aspect in influencing public health actions, and a new pattern of health information release and dissemination is gradually taking shape. Unofficial sources have become active promoters of people’s health protection initiatives, and a new pattern of multiple dissemination of health information is emerging. In India, scholars, experts, and government officials are now utilizing various channels and discourses to disclose information and popularize health information to the public, which has increased people’s willingness to take health protection measures. Therefore, the advantages of both official and unofficial publishers should be continuously brought into play to help health communication. Third, the development of multiparty trust is necessary in health programs promoted and participated in by the media. The release and promotion of health information should focus on persuasive methods and entry angles and improve the power and influence of information dissemination in terms of knowledge popularization, news reporting, and counter-rumor; and trust in all aspects of the environment should be built to carry out scientific and effective health protection.

The social determinants have been established to hinder the progress of vaccination efforts during the previous vaccination studies. In the United States, flu vaccinations are around 60% for children and lower among adults (45%). The role of risk perception has been identified in previous studies as in our study [

29]. As seen in the literature, individuals who appraise that they are vulnerable to COVID-19 or who feel it as a life-threatening illness are more likely to get vaccinated in comparison with those who neglect or disagree COVID-19 to be life-threatening.

Literature studies have leveraged the relationship between critical information socially provided and vaccination intentions and behavior [

30]. The social trust is dependent on the information provided by the government, medical authorities, and health-care facilities. A study conducted in Italy outlined that COVID-19 vaccine acceptance is associated with trust or mistrust in biomedical research [

31]. The role of political whirlpool is highly linked to every initiative or action that the government initiates in combatting COVID-19 within a community or society. Specific political principles used by individual political parties have shown to cause more rifts in vaccine hesitancy rates mainly due to the projection of false information by the conservative media [

22]. Numerous studies and assumptions have frequently documented extensive anti-vaccine schemes and reports in the social media [

20,

21]. The defiance for public health messaging in such an environment is not simple given the “wild west” nature of social media despite recent attempts by social media platforms to flag anti-vaccine content [

13,

24]. One potential pathway is to increase trust in science and scientists and communicate the standards and regulatory process for vaccine approvals. Yet, a typical establishment approach based on science and facts is unlikely to have a direct influence given that anti-vaccine sentiments are strongly influenced by emotions, often when preferences are driven by “affect heuristic” [

25]. It is critical to develop strategies to increase trust while countering the anti-vaccine influences drawing from strategic communication principles. A series of recent studies have documented the unequal impact of COVID-19-related impact on morbidity and mortality on “vulnerable” groups and communities including people of color, immigrants, and those in low-wage occupations and lower incomes. Almost without exceptions, almost all these studies showed that the social, economic, and health burden is being faced by such groups [

26,

27,

28]. The fact that there are education- or schooling-based variations in the likelihood of obtaining vaccines warrants a more directed and strategic approach. We need to understand the reasons for reluctance among people with low schooling and how to address them. In addition, studies have documented inequalities in communication that deter access to processing of and the capacity to act on information among different social classes, which need to be addressed in the context of COVID-19 [

19,

30]. In what appears to be counterintuitive, people who are working or employed are more likely to be reluctant to obtain a vaccine compared with retired and student populations. While the issue needs to be explored further, the immediate public health implication is targeting this population in public health communications.

Limitation: The study was focused on determining sources, trust, and vaccination intention of COVID-19 vaccines. The study did not explore in detail the relation of geographic distribution, economic status, and literacy rates to vaccine hesitancy. Race and ethnicity were avoided as India has a very sparse multirace population. Since India is a large country with a high population, our study was very specific in confining to its aim to avoid statistical bias generated during multiple variables.