Abstract

Cervical cancer is recognized as a serious public health problem since it remains one of the most common cancers with a high mortality rate among women despite existing preventative, screening, and treatment approaches. Since Human Papillomavirus (HPV) was recognized as the causative agent, the preventative HPV vaccines have made great progress over the last few years. However, people already infected with the virus require an effective treatment that would ensure long-term survival and a cure. Currently, clinical trials investigating HPV therapeutic vaccines show a promising vaccine-induced T-cell mediated immune response, resulting in cervical lesion regression and viral eradication. Among existing vaccine types (live vector, protein-based, nucleic acid-based, etc.), deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) therapeutic vaccines are the focus of the study, since they are safe, cost-efficient, thermostable, easily produced in high purity and distributed. The aim of this study is to assess and compare existing DNA therapeutic vaccines in phase I and II trials, expressing HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins for the prospective treatment of cervical cancer based on clinical efficacy, immunogenicity, viral clearance, and side effects. Five different DNA therapeutic vaccines (GX-188E, VGX-3100, pNGVL4a-CRT/E7(detox), pNGVL4a-Sig/E7(detox)/HSP70, MEDI0457) were well-tolerated and clinically effective. Clinical implementation of DNA therapeutic vaccines into treatment regimen as a sole approach or in combination with conservative treatment holds great potential for effective cancer treatment.

1. Introduction

Cervical cancer is a largely preventable cancer of the cervix, which is the narrow part of the lower uterus that connects to the vagina. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) statistics, cervical cancer became the fourth most frequent cancer in women in 2018, with 570,000 cases, which represent 6.6% of all female cancers worldwide [1]. Similarly, cervical cancer is the 2nd most common type of cancer among females, and the 4th most common cause of cancer-related deaths (8.5%) among women in Kazakhstan [1].

Previous studies have established the strong causative association between persistent infection with certain high-risk Human Papillomavirus (HPV) types and the development of cervical cancer [2]. HPV is a small, non-enveloped deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) tumor virus, which primarily affects human vaginal and oral mucosa [2]. There are more than 100 HPV subtypes, which differ by less than 3% of their genome [3]. The most prevalent oncogenic subtypes in both symptomatic (50–70%) and asymptomatic (20–30%) women diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer are HPV-16 and HPV-18 [3].

About 90% of deaths from cervical cancer occurred in low- and middle-income countries largely due to the lack of proper prevention, early diagnosis, and effective screening [1]. In 2018, WHO started a new campaign to decrease the incidence rate, with the aim to eventually eradicate cervical cancer [4]. The campaign included three key steps, which are vaccination of 90% of girls by 15 years of age, screening provision of 70% of women by 35 years of age and again by 45, and treatment of 90% of women with diagnosed cervical neoplasia [5]. Ideally, if all countries accomplished the requirements of the campaign by 2030, it is expected to decrease the incidence of new cases by 40% and 5 million related deaths by 2050 [1]. However, it is now estimated that the annual number of new cases of cervical cancer would be increasing to 700,000, and the number of deaths would reach 400,000 by 2030 [4]. Such an increase is explained by the uneven provision of screening and vaccination among countries, since these actions have occurred mostly in high-income settings [4]. In high-income countries, screening programs cover 60% of the female population, while, in lower-middle-income countries, the figure is only 20% [4]. Although preventative measures are expected to be effective in the elimination of cervical cancer in the long term, the situation now requires a short-term solution for those already in need of better treatment and care.

Nowadays, early-stage cervical intraepithelial lesions (CIN) are treated by means of surgical resection of cancerous tissue, which include conization, loop electrical excision procedure (LEEP), and radical hysterectomy [6]. These already traumatizing procedures can be coupled with radiotherapy or chemotherapy for the purpose of treatment enhancement and prevention of relapse [6]. Since radiotherapy and cytotoxic chemotherapy target not only cancerous tissue but surrounding tissues as well, patients often suffer constitutional side effects such as fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, hair loss, or adverse events (AEs) that negatively impact patient’s quality of life like anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, neuropathy, nephro-/hepatotoxicity, premature menopause, and infertility [6]. Therefore, it is necessary to provide less toxic and traumatic treatment options, especially for patients with comorbidities. After surgical excision, quadrivalent HPV vaccination could be used for CIN2+ cervical lesions to reduce the risk of recurrent disease [7].

Therapeutic vaccines such as TheraCys, PROVENGE, and IMLYGIC used for the treatment of urothelial carcinoma in situ, prostate cancer, and advanced melanoma respectively with promising results [8]. These cancer vaccines showed greater median overall survival compared to the conservative chemotherapy approaches, resulting in the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval [8]. The development of effective therapeutic vaccines for precancerous cervical lesions and cervical cancer treatment and their implementation into clinical practice would be a huge improvement in gynecologic oncology.

Currently, HPV therapeutic vaccines under investigation include live vector vaccines (bacterial and viral vectors), subunit vaccines (peptides and protein-based vaccines), plant peptide/protein-based vaccines, nucleic acid vaccines (DNA and ribonucleic acid (RNA) replicon-based vaccines), and cell-based vaccines (dendritic cell-based vaccines and adoptive cell transfer) [2]. Among these subtypes, we are particularly interested in DNA therapeutic vaccines, since they are safe, cost-efficient, thermostable, easily produced in high purity, and distributed [2]. Unlike live vector vaccines, DNA therapeutic vaccines do not evoke neutralizing antibody production, thus allowing for repeated vaccination [9]. T cell-mediated immune response is achieved by targeting HPV E6 and E7 proteins, as they are solely responsible for the malignant transformation of cervical tissue [9]. Moreover, in a study by Daayana et al., strong adaptive immune responses to E6 and E7 were reported, and it was shown to be greater than previously reported immune responses to therapeutic HPV vaccines [2,10]. Thus, the immunogenicity of DNA vaccines expressing the HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins needs to be further investigated. Currently, the majority of DNA therapeutic vaccines are undergoing clinical trials to evaluate their safety and stability. Therefore, the aim of this article is to assess and compare existing DNA therapeutic vaccines, which are evaluated in phase I and II trials, expressing HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins for the prospective treatment of cervical cancer based on clinical efficacy, immunogenicity, viral clearance, and side effects.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) statement [11]. The study was registered in the PROSPERO database and confirmed with a registration code of CRD42021251476.

Systematic Literature Search and Eligibility Criteria

Articles were manually searched using databases as PubMed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and clinicaltrials.gov published in English from the year 2010.

The search was performed using the following keywords: “cervical cancer”, “cervical intraepithelial neoplasia”, “HPV”, “HPV-positive”, “E6 and E7 oncoproteins”, “therapeutic vaccine”, “DNA vaccine”, and “DNA therapeutic vaccine”. We used the medical subject heading (MeSH) term “Uterine Cervical Neoplasms” (MeSH Unique ID D002583) as major topic and “Vaccines” (MeSH Unique ID D014612), “E6 protein, HPV type 18” (MeSH Unique ID C052603) and “E7 protein, HPV type 16” (MeSH Unique ID C059731).

The search was narrowed by using “Cervical cancer OR Cervical Intraepithelial Lesion AND DNA therapeutic vaccines”, “DNA therapeutic vaccines AND E6 OR/AND E7 oncoproteins”. The selected studies were independently reviewed for inclusion eligibility by two reviewers (Akhatova and Aimagambetova) using standardized data collection forms. The following data were collected from the studies: the author, year of publication, number of study participants, vaccine administration strategies, and the main outcomes (clinical efficacy, viral clearance, immunogenicity, adverse events). Any discrepancy in the assessment of articles was resolved by discussion and consensus, as well as input from the third and fourth reviewers (Chan and Azizan).

The articles were selected to meet the following eligibility requirements to be included in the study: (1) research article, (2) human subject research, and (3) the study of DNA therapeutic vaccines targeting HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins. The presence of the following did not allow for the study to be included: (1) reviews and case reports, (2) irrelevance to cervical cancer or CIN, (3) mouse model studies, (4) articles on preventative HPV vaccines, and (5) the use of the inappropriate methodology. Abstracts lacking full information about predefined criteria were excluded without further review.

The types of studies included were phase I and phase II clinical trials that were initiated and completed between 2003 and 2017, studying the clinical efficacy of DNA therapeutic vaccines expressing HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins for the treatment of cervical intraepithelial lesions of grades 2 and 3 both newly diagnosed and recurrent malignancies. The treatment of the lesion may or may not be followed by conization or loop electrosurgical excision procedure. The study population was female patients aged 18 or older with histopathologically diagnosed CIN of grades 2 and 3, known to be caused by HPV 16 and/or HPV 18 based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification results. The main outcomes of the review were clinical efficacy based on the lesion regression, viral load reduction, immunogenicity, in particular, HPV E6 and E7 specific CD8+ T cell response, and AEs after vaccination.

3. Results

3.1. Study Identification and Selection

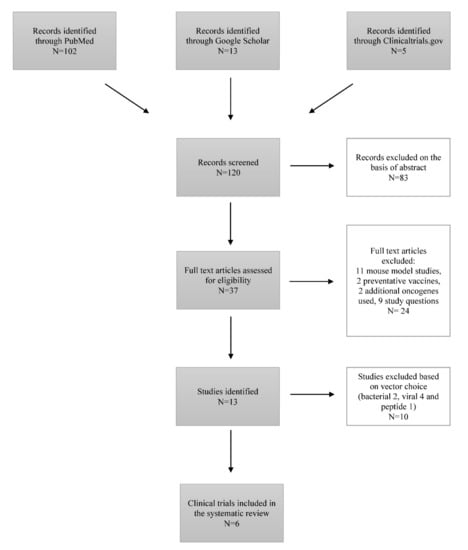

During this study, 120 articles were identified through PubMed/MEDLINE and Google Scholar searching platforms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow-chart diagram of study selection.

Eighty-three articles were excluded based on the abstract, representing literature reviews. From the remaining 37 articles, 24 articles were excluded at this stage: 11 studies were mouse model-based, 9 studies were not addressing the study question, 2 studies were regarding the preventative vaccines, and 2 studies included additional oncogenes in the development of therapeutic vaccines. We included 6 studies performed between 2003 and 2017 in our systematic review after the exclusion of 7 articles studying the effects of therapeutic vaccines with either viral, bacterial, or peptide vectors [12,13,14,15,16,17]. These six studies represented the work completed in the United States of America, Korea, Estonia, South Africa, India, Canada, Australia, and Georgia [12,13,14,15,16,17] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical trials.

Therapeutic vaccines were evaluated based on clinical efficacy (histopathological regression of the lesion to CIN < 1), viral clearance, immunogenicity, and adverse events after the vaccination. Subjects, female patients aged 18 or older with histopathologically diagnosed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia of grades 2 and 3, known to be caused by HPV 16 and/or HPV 18, received DNA therapeutic vaccines in different dose formulations and were evaluated generally within 20 weeks (36 weeks in extended trial groups) for the effects of vaccines mentioned above. Study populations ranged from 10 patients to 167, median age mostly being 21–30, except for Hasan et al. (2020) study, where the median age of participants was 51.50 years old due to more advanced stages of cancer [17].

3.2. Outcomes

3.2.1. Clinical Efficacy

Clinical efficacy was evaluated according to the histopathological regression to CIN ≤1, which is less than one-third of the thickness of the cervical epithelium, on a colposcopy-guided biopsy 15, 20, or 36 weeks after the first injection. All six studies [12,13,14,15,16,17] report tumor size decrease to some extent (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of the trials’ results.

GX-188 E in phase I trial by Kim et al. [13] showed a 78% success rate of complete response both histologically and virologically. The same vaccine in the phase II trial by Choi et al. (2019) resulted in histopathological regression to CIN < 1 in 52% of patients 20 weeks and 67% of patients 36 weeks after the first dose [12]. MEDI0457 by Hasan et al. showed 87.5% of complete response to the vaccine and 1 patient had a partial response to the treatment [17]. pNGVL4a-CRT/E7(detox) [15] and pNGVL4a-Sig/E7(detox)/HSP70 [16] vaccines both showed a similar response rate of around 30%.

3.2.2. Viral Load Clearance

Viral load was measured by means of PCR amplification to assess the clearance of HPV DNA from the cervical biopsy after vaccination. Choi et al. established that HPV clearance was associated with the histopathologic regression as 77% of regressors had no trace of HPV DNA, while only 12% of non-regressors had no viral load in the tissue biopsy [12]. Kim et al. results show that GX-188E takes time to clear off the virus [13]. MEDI0457 [17] and VGX-3100 [14] report the association between viral clearance and tumor size reduction, whilst pNGVL4a-CRT/E7(detox) [15] did not result in any difference between pre- and post-treatment viral load.

3.2.3. Immunogenicity

Immunogenicity is one of the key features of the therapeutic vaccines as it represents the potential of the vaccine to induce virus-specific T cell response, in particular HPV E6 and E7 specific CD8+ T cell immune response. IFN-γ response was measured by means of ex vivo ELISpot assay with cryopreserved and thawed peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) at pre- and post-treatment stages. The vaccine response is considered positive when the increase in T-cell frequency was at least three times greater compared to the study entry measurement. GX-188E both in phase I [13] and phase II [12] studies showed a significant increase in IFN-γ response, which was correlated with the histopathologic regression and viral clearance. Moreover, an E6 specific response was more pronounced than E7 specific [12,13]. VGX-3100 induced 9.5 times greater IFN-γ response in the treatment group compared to the placebo, which lasted as long as 24 weeks post-vaccination [14]. On the contrary, MEDI0457 induced a greater response to E7, particularly in newly diagnosed cohort 1 that persisted up to 48 weeks [17]. In cohort 1, 4 of 7 patients exhibited IFNγ-producing spots exceeding 100 SFU/106 PBMC, whereas no patients produced similar responses in cohort 2 [17]. pNGVL4a-CRT/E7(detox) and pNGVL4a Sig/E7(detox)/HSP70 showed minimal dose-dependent immune response, which was remarkable from the unvaccinated group [15,16].

3.2.4. Toxicity/Adverse Events

Overall, all vaccines were well-tolerated without vaccine-related serious adverse events. The most common adverse events were injection site pain and erythema, as well as constitutional symptoms (malaise, myalgia, and headache) [12,13,14,15,16,17]. No serious adverse events (Grade 3/4) related to the vaccination were reported. No dose-limiting toxicities were observed.

4. Discussion

This systematic review summarizes the findings of phase I and phase II clinical trials investigating the treatment of patients with histopathologically diagnosed CIN associated with HPV 16 or/and HPV 18 with DNA therapeutic vaccines. Six studies have demonstrated immunologic response in the form of lesion size regression, viral clearance, and increased T cell response of five different DNA vaccines–GX-188E (phase I and phase II), VGX-3100, pNGVL4a-CRT/E7 (detox), pNGVL4a-Sig/E7 (detox)/HSP70, MEDI0457. Vaccines were plasmid DNA encoding for either non-oncogenic E6/E7 or both, and chaperonin proteins such as HSP 70 and Calreticulin for the enhancement of the uptake by antigen-presenting cells, and MHC class I processing and presentation. MEDI0457 [17] had the same plasmid formulation as VGX-3100 [14] combined with plasmid encoding IL-12. All vaccines were well tolerated by patients, leading to only grade 1 or less systemic and local side effects.

Previous reviews have studied various existing therapeutic vaccines including live vectors, plant-based, protein, whole cell, and combinatorial vaccines [18]. This is the first systematic review of DNA therapeutic vaccines against cervical cancer expressing HPV16 and HPV18 E6 and E7 oncogenes. The feasibility of production, storage, and transportation, cost-effectiveness, the capability of multiple immunizations, and targeting different co-stimulatory genes provided the rationale for the study of DNA therapeutic vaccines [18]. However, comparatively weak immunogenicity and the risk of integration into the host genome are the main concerns, which could be addressed by modification of E6 and E7 to abolish its transformative capacity [18]. There are approaches of boosting the potency of DNA vaccines, such as increasing the number of antigen-expressing dendritic cells (DCs) by using a gene gun delivery method, enhancing antigen processing and presentation in dendritic cells via codon optimization, and improving the DCs and T-cell interaction [18]. These strategies were used in our selected studies, which led to increased antigen-specific, activated CD8+ T cell response in all of them. Patients with CIN2/3 were more likely to induce E6 and E7 specific CD8+ immune response, according to the IFNgamma ELISPOT results, compared to the invasive cervical cancer [17]. According to Hasan et al., diminished immune response in more advanced disease stages is associated with immune exhaustion, the effect of chemoradiation and selection of patients with diminished immunity against HPV [17]. The strongest evidence of the immunogenicity of DNA therapeutic vaccine VGX-3100 was observed by the increased intensity of CD8+ infiltrates in histopathologically regressed patients compared to the placebo group with regressed lesions [14].

DNA therapeutic vaccines were also assessed based on their clinical efficacy, i.e., the ability to induce cervical lesion regression. The regression to ≤CIN1 among study participants was observed in all studies with significantly varying degrees. The study of VGX-3100 vaccine with both treatment and placebo groups showed a response rate of 49.5% vs. 30.6%, respectively [14]. Meanwhile, GX-188E vaccine has resulted in histopathological regression in 67% of patients in both phase I study and phase II studies [12,13]. Choi et al. [12] have observed an enhanced response to GX-188E over time up to 83% among those with cervical lesions <50%, probably due to the enhanced memory T cell-driven therapeutic effect. The difference in clinical benefit between VGX-3100 and GX-188E could be explained with the recruitment of CIN3 HPV-positive patients only, the lack of placebo group, and the small number of participants in the latter. pNGVL4a-CRT/E7 (detox) and pNGVL4a-Sig/E7 (detox)/HSP70 had the lowest clinical efficacy of approximately 30% response rate among all [15,16]. However, the effect of these two vaccines on the lesion regression is questionable, as this rate is similar to spontaneous remission rate over a 15-week period [15].

It was established that women, after excision of the cervical lesion, are more likely to have a relapse; therefore, viral clearance is a key factor of vaccine efficacy [18]. VGX-3100, GX-188E, and MEDI0457 effectively cleared detectable HPV DNA, which was significantly associated with histopathological regression [12,13,14,17]. In contrast, pNGVL4a-CRT/E7 (detox) has not resulted in viral load reduction [15].

Nevertheless, there are several limitations to this study. Firstly, limited data exist on the topic of DNA therapeutic vaccines, as not a single therapeutic vaccine against cervical cancer was approved. All these clinical trials were in either the phase I or phase II stage of assessing the efficacy and safety in humans. Secondly, the majority of studies enrolled a small number of participants without masking, stratification, or the control group, which poses a potential risk for bias. As vaccines investigated in this study had different structural designs, it was not feasible to make a statistical analysis of vaccine outcomes; therefore, qualitative analysis was performed overall.

5. Conclusions

As it was stated by WHO, a global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer, 90–70–90 targets for prevention, screening, and treatment are the key to success. Preventative bivalent and quadrivalent HPV vaccines have undergone significant advancement in development and implementation. However, these preventative vaccines do not elicit a therapeutic effect but could be used as an adjuvant to surgical treatment. DNA therapeutic vaccines represent a potentially safe and novel approach to cervical cancer treatment. The main goal of this review was to discuss the effectiveness of existing DNA therapeutic vaccines against cervical cancer expressing HPV 16/18 oncoproteins E6 and E7. The idea of DNA therapeutic vaccines is inducing an adaptive immune response and immunologic memory via the expression of tumor antigens and activation of antigen-presenting cells.

DNA therapeutic vaccines are currently undergoing clinical trials to improve the potency of therapeutic vaccines and clinical efficacy using strategies as a modifying route of administration, adjuvant therapy, prime-boost regimen, and co-administering with other drugs for a synergistic effect. Nowadays, despite the treatment of locally advanced disease with chemoradiation, patients have a high recurrence rate and a poor 5-year survival rate, estimated at 50% and 70%, respectively. In contrast, the MEDI0457 vaccine, which contained VGX-3100 plasmid coupled with an IL-12 expression plasmid to promote T-cell function, evaluated the disease progression-free survival (PFS) at 12 months, which was estimated as 88.9% overall. These findings strengthen the hypothesis that DNA therapeutic vaccines could effectively induce de novo or boost existing immune responses. Moreover, studies have shown that using femtosecond laser treatment could also improve transfection efficiency administered intradermally and into the lesion in vivo. Thus, continuous efforts to improve the efficacy of DNA therapeutic vaccines and implementation of therapeutic vaccines into a treatment regimen as a sole approach or in combination with conservative treatment may greatly improve the current situation.

Author Contributions

A.A. (Ayazhan Akhatova)—data collection; A.A. (Ayazhan Akhatova) and G.A.—compiled, analyzed, and reviewed the data. A.A. (Ayazhan Akhatova) and G.A. prepared the manuscript draft. C.K.C. and A.A. (Azliyati Azizan) reviewed the final manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There is no funding source to declare.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Due to the nature of the study (systematic review), ethical approval is not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Nazarbayev University School of Medicine for the support that enabled the completion of this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- World Health Organization. Cervical Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cervical-cancer#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Chabeda, A.; Yanez, R.J.R.; Lamprecht, R.; Meyers, A.E.; Rybicki, E.P.; Hitzeroth, I.I. Therapeutic vaccines for high-risk HPV-associated diseases. Papillomavirus Res. 2018, 5, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibeanu, O.A. Molecular pathogenesis of cervical cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2011, 11, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Canfell, K. Towards the global elimination of cervical cancer. Papillomavirus Res. 2019, 8, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canfell, K.; Kim, J.J.; Brisson, M.; Keane, A.; Simms, K.T.; Caruana, M.; Burger, E.A.; Martin, D.; Nguyen, D.; Bénard, É.; et al. Mortality impact of achieving WHO cervical cancer elimination targets: A comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Lancet 2020, 395, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, C.A.; James, D.; Marzan, A.; Armaos, M. Cervical cancer: An overview of pathophysiology and management. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 35, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghelardi, A.; Parazzini, F.; Martella, F.; Pieralli, A.; Bay, P.; Tonetti, A.; Svelato, A.; Bertacca, G.; Lombardi, S.; Joura, E.A. SPERANZA project: HPV vaccination after treatment for CIN2+. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 151, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeMaria, P.J.; Bilusic, M. Cancer Vaccines. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 33, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, M.A.; Farmer, E.; Huang, C.; Lin, J.; Hung, C.F.; Wu, T.C. Therapeutic DNA Vaccines for Human Papillomavirus and Associated Diseases. Hum. Gene Ther. 2018, 29, 971–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daayana, S.; Elkord, E.; Winters, U.; Pawlita, M.; Roden, R.; Stern, P.L.; Kitchener, H.C. Phase II trial of imiquimod and HPV therapeutic vaccination in patients with vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 102, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br. Med. J. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J.; Hur, S.Y.; Kim, T.J.; Hong, S.R.; Lee, J.K.; Cho, C.H.; Park, K.S.; Woo, J.W.; Sung, Y.C.; Suh, Y.S.; et al. A phase II, Prospective, Randomized, Multicenter, open-label study of GX-188E, an HPV DNA vaccine, in patients with Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia 3. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 26, 1616–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, T.J.; Jin, H.T.; Hur, S.Y.; Yang, H.G.; Seo, Y.B.; Hong, S.R.; Lee, C.W. Clearance of persistent HPV infection and cervical lesion by therapeutic DNA vaccine in CIN3 patients. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trimble, C.L.; Morrow, M.P.; Kraynyak, K.A.; Shen, X.; Dallas, M.; Yan, J.; Edwards, L.; Parker, R.L.; Denny, L.; Giffear, M.; et al. Safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of VGX-3100, a therapeutic synthetic DNA vaccine targeting human papillomavirus 16 and 18 E6 and E7 proteins for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 2078–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alvarez, R.D.; Huh, W.K.; Bae, S.; Lamb, L.S., Jr.; Conner, M.G.; Boyer, J.; Wang, C.; Hung, C.F.; Sauter, E.; Paradis, M.; et al. A pilot study of pNGVL4a-CRT/E7(detox) for the treatment of patients with HPV16+ cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3 (CIN2/3). Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 140, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trimble, C.L.; Peng, S.; Kos, F.; Gravitt, P.; Viscidi, R.; Sugar, E.; Pardoll, D.; Wu, T.C. A phase I trial of a human papillomavirus DNA vaccine for HPV16+ cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hasan, Y.; Furtado, L.; Tergas, A.; Lee, N.; Brooks, R.; McCall, A.; Golden, D.; Jolly, S.; Fleming, G.; Morrow, M.; et al. A Phase 1 Trial Assessing the Safety and Tolerability of a Therapeutic DNA Vaccination Against HPV16 and HPV18 E6/E7 Oncogenes After Chemoradiation for Cervical Cancer. Int. J. Radiat Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020, 107, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, C.-F.; Ma, B.; Monie, A.; Tsen, S.-W.; Wu, T.-C. Therapeutic human papillomavirus vaccines: Current clinical trials and future directions. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2008, 8, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).