Abstract

Epidemiologic studies from several countries have found that mortality rates associated with the metabolic syndrome are inversely associated with coffee consumption. Metabolic syndrome can lead to arteriosclerosis by endothelial dysfunction, and increases the risk for myocardial and cerebral infarction. Accordingly, it is important to understand the possible protective effects of coffee against components of the metabolic syndrome, including vascular endothelial function impairment, obesity and diabetes. Coffee contains many components, including caffeine, chlorogenic acid, diterpenes and trigonelline. Studies have found that coffee polyphenols, such as chlorogenic acids, have many health-promoting properties, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, anti-diabetes, and antihypertensive properties. Chlorogenic acids may exert protective effects against metabolic syndrome risk through their antioxidant properties, in particular toward vascular endothelial cells, in which nitric oxide production may be enhanced, by promoting endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression. These effects indicate that coffee components may support the maintenance of normal endothelial function and play an important role in the prevention of metabolic syndrome. However, results related to coffee consumption and the metabolic syndrome are heterogeneous among studies, and the mechanisms of its functions and corresponding molecular targets remain largely elusive. This review describes the results of studies exploring the putative effects of coffee components, especially in protecting vascular endothelial function and preventing metabolic syndrome.

1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome is a combination of medical conditions, including dyslipidemia, elevated blood pressure, insulin resistance, and excess body weight. An increase in the rate of adult obesity has led to increases in obesity-associated metabolic disorders, such as insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, which are major risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1]. While the mechanism underlying metabolic syndrome is poorly understood, insulin resistance appears to be an important factor [2]. The occurrence of hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and hypertension in metabolic syndrome is associated with endothelial dysfunction and promotion of atherogenesis [3]. These changes show that patients with metabolic syndrome have an increased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke [4,5], which, together, contribute to the burden of non-communicable diseases [6].

Various components of the common diet have been suggested to potentially affect endothelial function, including fruits, vegetables, olive oil and nuts [7,8,9,10]. Several epidemiological studies have shown that coffee consumption is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders and certain cancers [11]. Among the observed results, evidence suggests that individuals consuming moderate amounts of coffee might be less likely to be affected by metabolic syndrome [12,13]. Evidence has been increasing recently supporting the protective effects of coffee and its components, such as caffeine, chlorogenic acids and diterpenes, against oxidative stress and related metabolic syndrome risk [14,15]. Results from a recent meta-analysis indicated that the coffee intake was inversely related with the risk of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) [16]. These effects are likely due to the presence of chlorogenic acids and caffeine [17]. Moreover, other reports described the effect of coffee intake on lipid, protein and DNA damage, and the modulation of antioxidant capacity and antioxidant enzymes in human studies [18,19]. These results suggested that coffee consumption enhances glutathione levels and offers protection against DNA damage [19,20]. In contrast, caffeine consumption of ≥6 units/day during pregnancy is related with impaired fetal length growth [21]. Also, this report indicated that a higher caffeine intake might preferentially adversely affect fetal skeletal growth.

In metabolic syndrome, inflammation is promoted, which strongly increases the risk of systemic CVD [22,23]. Endothelial dysfunction reduces vasodilation, enhances proinflammatory status and thrombogenesis, and is the first step in the development of CVD [24]. The development of arteriosclerosis that occurs in metabolic syndrome is attributed to endothelial dysfunction. Namely, these events of endothelial dysfunction strongly induce CVD [25]. On the other hand, the intake of coffee contributes to the prevention of endothelial dysfunction and decrease in CVD. A recent study demonstrated that the inverse relationship between coffee consumption and metabolic syndrome may reflect coffee’s content of antioxidants that offer cardiovascular protection [26]. This review considers the effects of coffee polyphenols on vascular endothelial function in preventing metabolic syndrome. The association of coffee intake with metabolic syndrome and with vascular disorders induced in metabolic syndrome will be discussed.

2. Antioxidant Effects of Coffee Components

Coffee is a major source of antioxidant polyphenols in the Japanese diet [27]. As shown in Table 1, coffee has the highest total polyphenol content in beverages, followed by green tea.

Table 1.

Total polyphenol intake from beverages in the Japanese diet a.

Coffee contains over 1500 chemicals, most of which are formed during the roasting process. The total polyphenol consumption from coffee is 426 mg/day, which makes up 50% of the amount of polyphenols consumed daily in the Japanese population [27]. Typically found polyphenols include caffeine, chlorogenic acid, diterpenes and trigonelline [28]. The chemical composition of green coffee beans is shown in Table 2 [29]. The main water-soluble constituents in coffee are phenolic polymers, polysaccharides, chlorogenic acids, minerals, caffeine, organic acids, sugars, and lipids. Furthermore, the lipid-soluble constituents of coffee include mainly triacylglycerols, tocopherols, and esters of diterpene alcohols with fatty acids.

Table 2.

Comparison of chemical components of green beans in Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora.

Coffee is a major source of antioxidant polyphenols in the Japanese diet [28]. Coffee has antioxidative components and contributes to oxidative stress prevention [30]. The antioxidative compounds inhibit nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase in the mitochondria and decrease production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [31]. For this reason, coffee is understood to be a diet beverage that can inhibit oxidative stress. The coffee component induces antioxidant activity and endothelial nitric oxide (NO) production. For example, intake of caffeoylquinic (CQA, a representative of chlorogenic acid) for 8 weeks decreased NADPH-dependent ROS production and enhanced NO production in the aorta of spontaneously hypertensive rats [32]. In addition, CQA was directly related to the blocking of gene expression of the NADPH-oxidase component, p22phox [32]. These results indicate that the CQA might decrease oxidative stress and induce NO production and help to prevent endothelial dysfunction, such as vascular hypertrophy and hypertension, in spontaneously hypertensive rats.

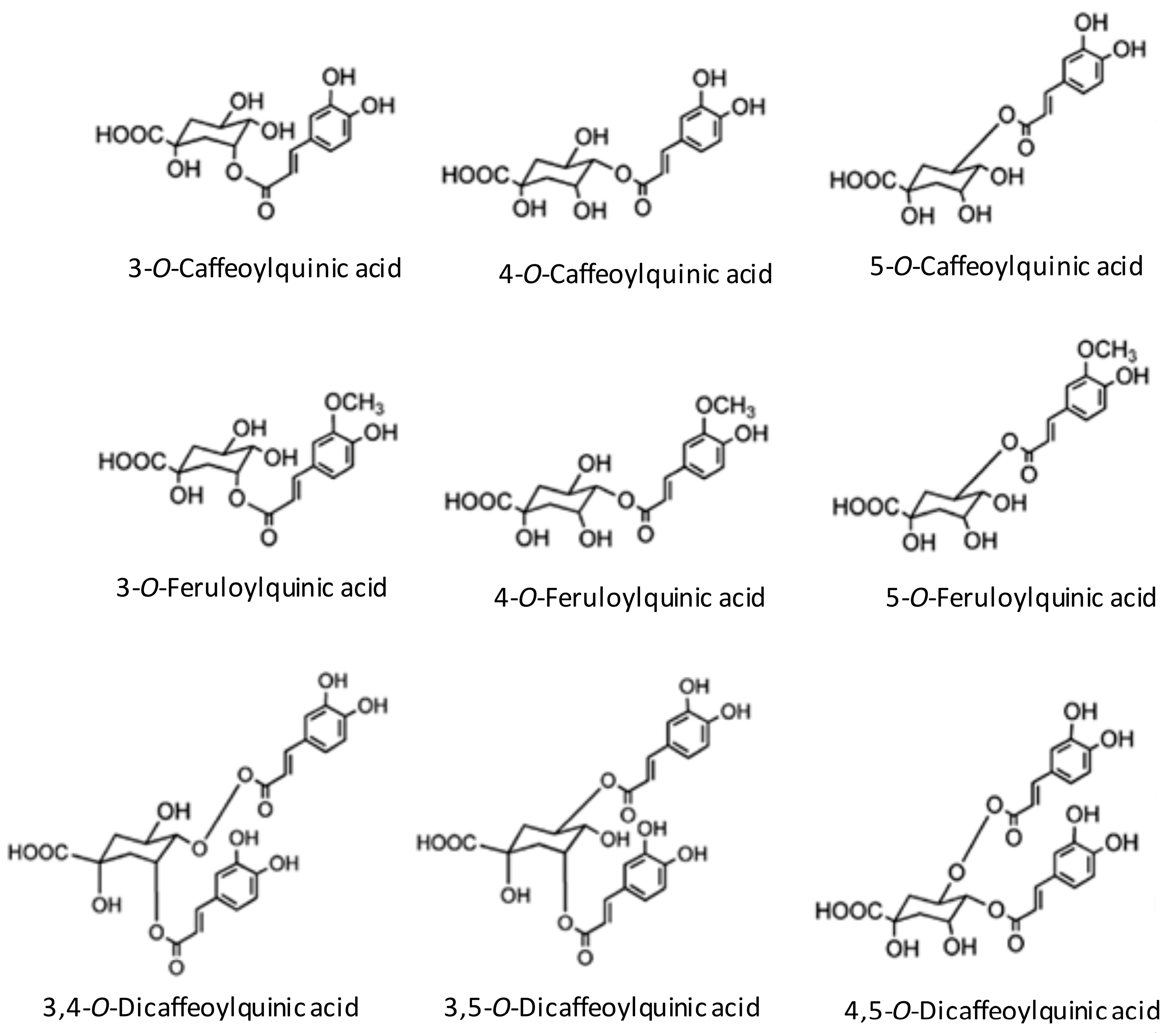

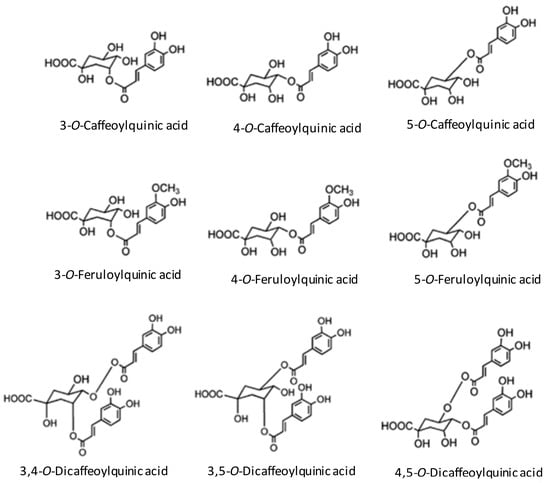

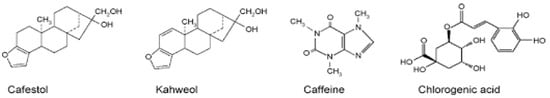

The main antioxidants in coffee are the chlorogenic acids, caffeine, and melanoidins [17]. Chlorogenic acids consist of a family of esters formed between quinic acid and caffeic acid. The subclasses of chlorogenic acids are CQA, feruloylquinic (FQA) and dicaffeoylquinic (diCQA) acid. The main chlorogenic acid subclass in coffee is CQA [17,33] (Figure 1). Following acute consumption of coffee, a significant 5.5% rise in plasma antioxidant activity in human has been demonstrated [34], including inhibition of low density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation [35,36]. Therefore, the effect of CQA may contribute to an arteriosclerotic preventive mechanism. Also, caffeine has antioxidant properties, such as the ability to scavenge hydroxyl radicals [37]. Caffeine has been shown to scavenge superoxide radicals by measurements of O2− after reaction with caffeine using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) [38,39]. These results support the findings of another study in which caffeine had antioxidative effects and inhibited peroxidation of LDL [40]. Finally, the browned material in coffee also has antioxidative effects. The taste and the color of the coffee are produced mainly by a roasting process with the Maillard reaction. These substances contribute to the antioxidation effect and oxidative stress of the coffee [41,42]. In the roasted coffee bean, melanoidin is produced from nonenzymatic browning and accounts for the coffee bean’s antioxidant activity [43]. Chlorogenic acid decreases in roasting, but melanoidins increase and may make up for the decrease in antioxidation from a loss of chlorogenic acid [44]. The antioxidative difference of the coffee changes by a roast. Differences in reactivity for roasts on antioxidants, such as chlorogenic acid, may influence the antioxidation characteristics of the coffee.

Figure 1.

Structure of main chlorogenic acids in coffee (Adapted from reference Stamach et al., 2006) [29].

3. Epidemiological Studies of Coffee Consumption and the Metabolic Syndrome

3.1. Coffee Intake and Metabolic Syndrome

Regular consumption of coffee has been associated with lower odds of having metabolic syndrome [12,13]. Clinical evidence of the effects of coffee consumption on various components of the metabolic syndrome has been provided by a cross-over, randomized controlled study, investigating men and women with normal cholesterol levels (n = 25) and those with hypercholesterolemia (n = 27) aged 18–45 years with body mass index (BMI) ranging from 18–25 kg/m2. For 8 weeks, the study subjects consumed three servings/day of a blend providing coffee polyphenols, hydroxycinnamic acids (510.6 mg) and caffeine (121.2 mg), or a control drink. In the coffee consumption groups, blood pressure, body fat percentage, and levels of leptin, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and resistin were reduced. In addition, glucose concentration, insulin resistance and triglyceride levels were reduced. Notably, these reductions were much greater in the group with hypercholesterolemia compared with the controls. These results suggest that regular coffee consumption can improve the pathologic condition of patients with metabolic syndrome-associated hypercholesterolemia.

Most of the existing evidence relies on the results of two meta-analyses showing an association between coffee consumption and metabolic syndrome in observational studies [12,13]. The meta-analyses included 13 studies with a total of 159,805 participants and showed an inverse association between regular coffee consumption and metabolic syndrome, despite evidence of heterogeneity between results of the studies included. The causes for these differences may have been variations across the studies in terms of lifestyle and the percentages of patients with metabolic syndrome as well as in coffee-drinking habits, such as adding milk, full-fat cream or sugar [45]. Several other factors may have accounted for the heterogeneity among results. For instance, most of the studies did not consider methods of preparation, type, and roasting process of coffee, which have been shown to influence the phytochemical component of the beverage [46]. Moreover, collinearity may exist with the intake of certain foods, sugar, and the presence or absence of milk [47]. Other sources of heterogeneity may be derived from lifestyle differences among individuals, for instance, the level of smoking, which has been shown to be an effect modifier of the association between coffee intake and health outcomes [48]. Third, none of the studies took into account genetic factors, which have been reported to affect the relationship between coffee and cardiovascular outcomes due to polymorphisms related to caffeine metabolization [49,50].

Collectively, it was shown that the association between coffee consumption and occurrence of metabolic syndrome varied greatly across studies (Table 3). In a large general population cohort study, high coffee consumption was associated with low risks of obesity, metabolic syndrome and T2DM [51]. The study results indicated that high coffee consumption was associated with decrease in obesity, metabolic syndrome and T2DM. Moreover, high coffee consumption was associated with low BMI, weight, height, systolic/diastolic blood pressure, triglycerides and cholesterol. In another study, the effects of coffee consumption in metabolic syndrome were investigated in healthy subjects: 174 men and 194 women were followed from the age of 27 years onwards [52]. This study began in 1977, along with an observational longitudinal study that examined 600 girls and boys. The strongest evidence supporting a positive health effect of coffee consumption has been for diabetes. However, this study demonstrated that long-term coffee consumption was not associated with metabolic syndrome. While coffee consumption appeared to be significantly reversely correlated with blood pressure, the relationship was no longer significant after adjustment for lifestyle covariates. In a Mendelian randomization study, we examined the relationship between coffee intake and obesity, metabolic syndrome, and T2DM in 93,179 people with T2DM in two large cohorts. A high intake of coffee was associated with a reduced risk of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type II diabetes mellitus. Furthermore, higher coffee consumption was associated with reduced BMI, weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, triglycerides and total cholesterol and increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [51]. In addition, a study of metabolic syndrome in Poland investigated the association of tea and coffee consumption with the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in 8821 subjects aged 20 years and older. The relationship of coffee intake with metabolic syndrome suggested a role for coffee intake in cardiovascular prevention. The effect of the coffee may have been caused by antioxidant action [53]. Still another study showed that the risk of metabolic syndrome was associated with coffee intake in 15,691 Korean women, indicating that coffee intake might be related to a decreased occurrence of metabolic syndrome in this population [54].

Table 3.

Characteristics of studies investigating the relationship between coffee consumption and metabolic syndrome and its components.

Furthermore, the report showed a relationship between coffee intake and metabolic syndrome in overweight and normal individuals. The studies included a questionnaire-style interview, blood pressure measurements and examination of fasting blood samples. In the obese and overweight groups, lower coffee intake compared with higher intake was associated with a higher risk of abdominal obesity, hypertension, abnormal glucose concentration, triglycerides and metabolic syndrome [55]. Another study examined the relationship between dietary lifestyle factors with metabolic syndrome. Daily drinking of 2–3 cups of coffee was inversely related to metabolic syndrome, and sleeping 7–8 h per night was related to decreased odds of metabolic syndrome [15]. In a cross-sectional study, coffee intake was inversely associated with metabolic syndrome and triglyceride levels in 1886 Italian subjects [55]. Also, in 8821 Italian subjects, coffee consumption was negatively associated with metabolic syndrome, waist circumference, hypertension and triglyceride levels [55]. The report also demonstrated that coffee intake was negatively associated with metabolic syndrome, waist circumference, hypertension and triglycerides [56]. Furthermore, in 17,953 Korean adults, when comparing those who consumed instant coffee >3 times/day with those who consumed instant coffee <1 time/week, the odds ratio for metabolic syndrome was 1.37. In addition, coffee drinkers had an increased risk of obesity, abdominal obesity and low levels of high-density lipoprotein [61]. In these studies, most of the subjects consumed milk or consumed an instant coffee mix containing sugar and powdered creamer. These results indicate that instant coffee drinkers have increased risks of these metabolic conditions, and that the consumption of the instant coffee mixture may have a noxious effect on metabolic syndrome. Therefore, the increased risk of metabolic syndrome may be attributed in part to the excessive intake of sugar and powdered creamer. Furthermore, the association between coffee and metabolic syndrome was evaluated by several large-scale prospective studies, despite results being mostly contrasting (9514 in the United States, [61]; 17,014 in Norway, [62]; and 368 in the Netherlands, [46]).

3.2. Coffee Intake and Obesity

The rate of obesity has increased on a global scale in both adults and children, is related to several comorbidities, such as hypertension and T2DM, and is strongly related to the onset of CVD [64]. In the United States, prospective studies examined the interaction of habitual coffee consumption with the genetic predisposition to obesity in relation to BMI in 5116 men and 9841 women [65]. Higher coffee consumption appeared to reduce the genetic association between obesity and BMI—individuals with greater genetic predisposition to obesity were observed to have a lower BMI, related to higher coffee consumption. Furthermore, a randomized clinical trial was performed with obese women aged 20–45 years in which an intervention group received 400 mg of coffee [66]. The body weight, body mass and fat mass indices, and waist-to-hip circumference ratio of the intervention group decreased, compared to the control group. Furthermore, the intervention group had decreased cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels, compared to the control group. In contrast, the serum adiponectins increased in the intervention group. These results indicate that consumption of coffee may reduce obesity.

3.3. Coffee Intake and Type 2 Diabetes

A meta-analysis of prospective studies (10 articles involving 491,485 participants, including 29,165 with T2DM) was performed to evaluate the relationship between coffee and caffeine consumption and T2DM incidence [67]. The relative risk of T2DM decreased with coffee intake. In addition, a relationship between T2DM incidence and coffee intake was found among non-smokers with BMI <25 kg/m2. In particular, the effect on T2DM risk was higher in women. Furthermore, a large-scale case-cohort study demonstrated evidence for an interaction of incretin-associated TCF7L2 genetic variants and an incretin-specific genetic risk score with coffee consumption in relation to T2DM risk [68]. The cohort study included 11,035 participants, among them, 8086 incident T2DM cases. However, none of these relationships were statistically significant.

In cohort study of 2332 Chinese subjects, coffee intake was indicated to be inversely related to T2DM [69]. Habitual coffee consumption was associated with a 38–46% reduced risk of T2DM, compared to than non-drinkers. In a prospective cohort study in 88,259 US women (younger and middle-aged, incident cases 1263) were examined for coffee and caffeine intake and risk of T2DM [70]. The relative risk of T2DM decreased depending on coffee intake. Coffee consumption may decrease the risk of T2DM in younger and middle-aged women. Furthermore, reports indicated that the consumption in adults of up to 3 cups a day of coffee decreased the risk of T2DM and of metabolic syndrome [71]. Recently, in a Mendelian randomization study, habitual coffee consumption was inversely associated with T2DM, along with depression and Alzheimer’s disease onset [72]. These results indicate that coffee consumption may contribute to decreases in T2DM.

3.4. Coffee Intake and Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis

The relationship between non-alcoholic steatohepatitis with coffee intake was explored by several epidemiologic studies. One prospective cohort study indicated an inverse association between coffee consumption and liver cirrhosis [73,74]. This study involved a cohort of 63,275 Chinese subjects (middle-aged and older) in the Singapore Chinese Health Study [75]. Compared to non-daily coffee drinkers, those who drank two or more cups per day had a 66% reduction in mortality risk. Coffee intake was related to a decrease in the risk of mortality, except coffee intake was not associated with hepatitis B-related cirrhosis mortality. Furthermore, a cross-sectional study (n = 347) showed an inverse association between coffee consumption and liver fibrosis [76]. In the study, high coffee consumption was related to a lower occurrence of clinically significant fibrosis. This result suggests that coffee consumption may exert beneficial effects on fibrosis progression [77].

However, neither the occurrence of fatty liver, nor the prevalence of fatty liver, as assessed by ultrasonography (SteatoTest) and the hepatorenal index, were related to coffee consumption. In a cross-sectional study, the effects of coffee consumption were investigated in patients (n = 1018) with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (n = 155), hepatitis C virus (n = 378), and hepatitis B virus (n = 485). Drinking two or more cups of coffee per day was related to improvements in pathologic conditions [77]. In an epidemiological study on the association of coffee intake with chronic liver disease, 286 patients in a liver outpatient department in a hospital in Scotland completed a questionnaire regarding coffee consumption and lifestyle factors. The results indicated that coffee intake may be related to a reduced prevalence of cirrhosis in patients with chronic liver disease [78].

3.5. Coffee Intake and Atherosclerosis

A cohort study in Tokushima Prefecture, Japan, investigated the relationship between coffee intake and arterial stiffness [79]. A report indicated that the intake of coffee was inversely related to arterial stiffness in 540 Japanese men [79]. Coffee intake was inversely related to arterial stiffness, independent of atherosclerotic risk factors. This result was related partially to a decrease in circulating triglycerides. In addition, other studies suggest that the addition of milk may affect coffee’s preventive action on arteriosclerosis [46,51]. On the other hand, in a cohort study, no association was observed between coffee or caffeine intake and coronary and carotid atherosclerosis. The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study examined the relationship between coffee intake and atherosclerosis in 5115 young adults [80]. No relationship was observed between atherosclerosis and the intake of average coffee, decaffeinated coffee, or caffeine intake. Furthermore, in 6508 ethnically diverse participants, coffee intake (>1 cup per day) was not associated with coronary artery calcification or cardiovascular events [81]. In a cross-sectional study, 1929 participants without known coronary heart disease, coffee intake and calcified atherosclerotic plaques in the coronary arteries were examined [82]. The results did not support a relationship between coffee intake and coronary-artery calcification in men and women. On the other hand, caffeine consumption was marginally inversely related to coronary artery calcification. As for the intake of more than 1 cup of coffee per day, caffeine may be related to cardiovascular events. In addition to epidemiological studies, further interventional studies may be needed to confirm the causal association.

3.6. Coffee Intake and Hypertension

In a meta-analysis of seven cohort studies, including 205,349 individuals and 44,120 cases of hypertension, an increase in 1 cup/day of coffee consumption was associated with a 1% decreased risk of hypertension [83]. Results from individual cohort studies suggest that the risk of hypertension depends on the coffee intake level. In a prospective cohort study of 24,710 Finnish subjects with no history of antihypertensive drug treatment, coronary heart disease, or stroke at baseline, the association between coffee intake and the incidence of antihypertensive drug treatment was investigated. The multivariate-adjusted hazard ratios for the amount of coffee consumed daily were marginally significant for baseline systolic blood pressure [84]. Low-to-moderate coffee intake appeared to increase the risk of antihypertensive drug treatment. In a cross-sectional population-based study including 8821 adults (51.4% female) in Poland, coffee consumption was negatively related to hypertension [85]. More details on the relationship of coffee intake with hypertension will have to be determined in future studies.

4. Coffee Composition and Features

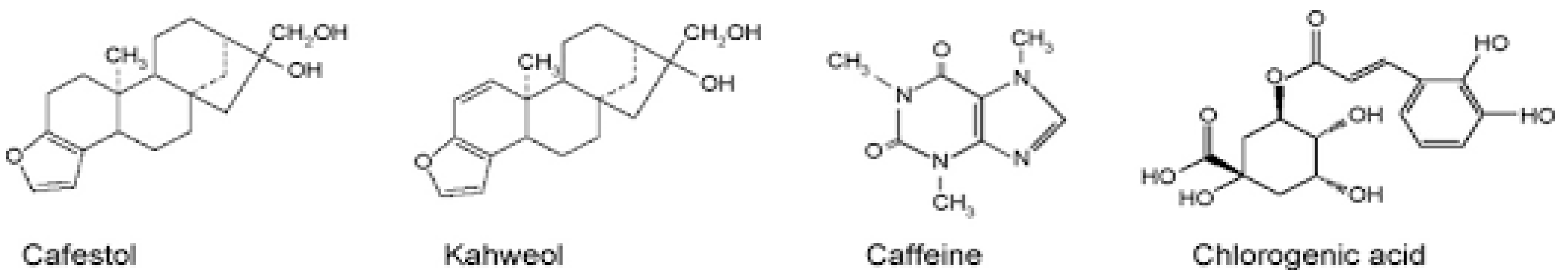

Commercially important coffee comes from the species Coffea arabica and Coffea robusta. Coffee from the arabica species has good flavor and constitutes approximately 80% of the coffee consumed in the world [14]. The composition of coffee changes with the coffee bean species and roast process conditions [41]. Specifically, Coffea arabica differs from Coffea robusta, and the roast condition differs with time or temperature. Chemical components of green beans in Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora are shown in Table 2 [16]. Preparations include boiled unfiltered coffee, filtered coffee, and decaffeinated coffee. The compositions differ across the species, degree of roasts and preparation of the coffee. A large number of different compositions are present in coffee, but caffeine, diterpene, kahweol and chlorogenic acid and other phenols are the basic components (Figure 2) [86]. Components with which metabolic syndrome prevention is expected are caffeine, diterpenes, kahweol and polyphenols. In particular, chlorogenic acid has many beneficial effects [69].

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of proposed bioactive compounds in coffee (Adapted from reference Bonita et al., 2007) [86].

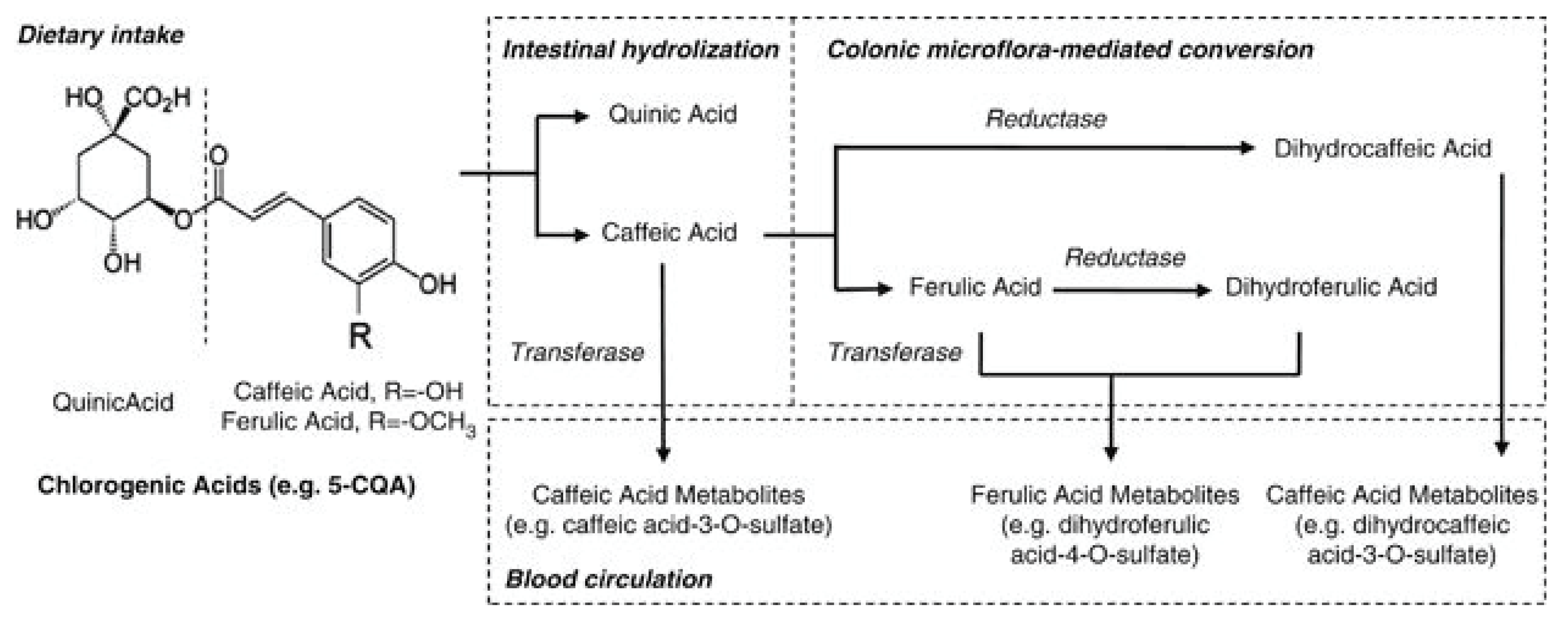

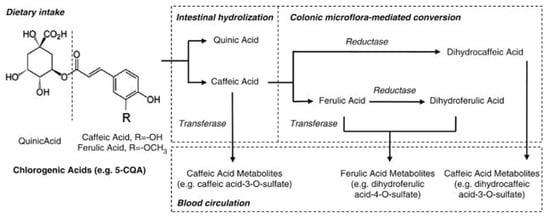

Chlorogenic acids are a family of molecules formed between quinic and cinnamic acids and metabolized to several molecules in the body (Figure 3) [87]. The most common chlorogenic acid is 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid (CQA), but it is called simply chlorogenic acid. It was reported that the chlorogenic acid content of one 200-mL cup of coffee ranges from 70 to 350 mg [88]. Trigonelline is a niacin-related compound and is another component of coffee. Trigonelline was observed to alter induction of estrogen-dependent growth through the estrogenic action in human breast cancer cells [89]. This activity indicates that trigonelline has an estrogenic effect.

Figure 3.

Main metabolic pathway of chlorogenic acids. Dietary chlorogenic acids is hydrolyzed into quinic acid, caffeic and ferulic acid, and further metabolized in small intestine and colon before entering into blood stream (Adapted from reherence Zhao et al., 2012) [87].

5. Chlorogenic Acid and Metabolic Syndrome Associated-Endothelial Dysfunction

The increase of markers of inflammation enhances global cardiovascular risk. The inflammatory response is enhanced early in adipose expansion and chronic obesity during metabolic syndrome onset [27]. Increasing evidence suggests that chronic subclinical inflammation is part of the metabolic syndrome. For example, increased serum concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and IL-6 might attenuate insulin action by inhibiting insulin signaling [88]. A number of features of metabolic syndrome are related to low-grade inflammatory pathological conditions (Table 4) [89]. Increased plasma C-reactive protein has been observed in insulin-resistant and obese subjects and is a surrogate marker for both coronary heart disease and diabetes [90]. The adipose tissue secretes several adipocytokines and induces inflammation and oxidative stress in vascular tissue. In particular, adiponectin and resistin regulate monocyte adherence to vascular endothelial cells [91]. Subsequently, enhancing monocytic migration to the subendothelial space is one of the key events in the development of atherosclerosis. Specifically, the metabolic syndrome induces vascular endothelial cell disorder and induces arteriosclerosis, and arteriosclerosis, in turn increasing the risk for conditions such as myocardial infarction or cerebral infarction. Chlorogenic acid appears to protect normal endothelial activity [92]. On the other hand, chlorogenic acid inhibited interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β)-induced gene expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 and endothelial cell selectin in human umbilical vein endothelial cells [59]. Also, chlorogenic acid blocked IL-1β-induced nuclear translocation of nuclear factor-kappaB subunits p50 and p65 and suppressed the adhesion of human lymphoma cell line, U937 cells. In addition, a recent study demonstrated the protective effects of chlorogenic acid on human umbilical vein endothelial cells [93]. Namely, chlorogenic acid induced a cell growth higher than those stimulated with inflammatory TNF-α only. Furthermore, chlorogenic acid reduced reactive oxygen species and xanthine oxidase-1 levels, and enhanced superoxide dismutase and heme oxygenase-1 levels in endothelial cells. A study described the effects of chlorogenic acid on endothelial function with oxidant-enhanced damage in isolated aortic rings from mice. Chlorogenic acid reduced HOCl-induced oxidative damage in endothelial cells. The mechanism of the beneficial effect of chlorogenic acid was associated with the production of NO and induction of heme oxygenase-1 [94]. Consumption of coffee with a high content of chlorogenic acids repaired endothelial dysfunction by decreasing oxidative stress [95]. A previous study indicated that oxidative stress has been demonstrated to play a important role in the development of endothelial dysfunction [96]. Chlorogenic acid appears to protect against endothelial dysfunction due to its antioxidant activity. Also, chlorogenic acid inhibited TNFα-induced intercellular adhesion molecule-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 expression in human endothelial cells. In addition, it has been reported that chlorogenic acid blocks α-glucosidase activities, and may thus prevent T2DM [97]. It is suggested that chlorogenic acid prevents vascular endothelial disorder through this inhibitory activity. These results suggest that chlorogenic acid prevents induced atherosclerosis that would otherwise stimulate inflammation. Lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) is a major phospholipid component of oxidized LDL and is associated with atherogenic induction [98]. A recent report indicated the effects of chlorogenic acid on intracellular calcium control in LPC-treated endothelial cells [99]. Namely, the gene expression of the transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) channel 1 was enhanced significantly by LPC treatment and inhibited by chlorogenic acid. Thus, chlorogenic acid may protect endothelial cells against LPC injury and inhibit atherosclerosis.

Table 4.

The inflammatory component of the metabolic syndrome a.

Furthermore, the effects of the representative chlorogenic acid CQA on vascular function and blood pressure were evaluated in normotensive Wistar–Kyoto rats and spontaneously hypertensive rats [32]. CQA increased NO production and decreased ROS production. In addition, CQA reduced hypertension, and prevented the impairment of endothelial function in spontaneously hypertensive rats. NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide had a important role in the control of vascular tone in health and disease [100]. In endothelial cells, heme oxygenase-1 is induced in response to oxidative stress, which may play a role in vascular prevention. Furthermore, a report demonstrated that the pretreatment of cultured human aortic endothelial cells with 10 μM chlorogenic acid prevented endothelial cell viability following exposure to hypochlorous acid [94]. Chlorogenic acid enhanced endothelial nitric oxide synthase dimerization and induced heme oxygenase-1 protein expression in human aortic endothelial cells. These results are consistent with the endothelial protective effects of coffee consumption. These reports suggest that the coffee component, chlorogenic acid, can protect cultured endothelial cells against inflammation-enhanced endothelial dysfunction and play an important role in the prevention of atherosclerotic complications.

6. Conclusions

Metabolic syndrome is a strong risk factor for atherosclerosis-associated CVD and T2DM. Obesity due to excess energy intake strongly enhances the metabolic syndrome—concomitant obesity is the major driver of the syndrome. However, coffee polyphenols can reverse the metabolic risk factors of metabolic syndrome. Coffee polyphenols inhibit atherosclerosis-related CVD and T2DM, respectively. Coffee has many health-promoting properties, and chlorogenic acid appears to protect against metabolic syndrome through its antioxidant activity. The antioxidative effects of coffee components may be a basic feature of prevention.

Acknowledgments

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| BMI | body mass index |

| CVD | cardiovascular disease |

| CQA | 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid |

| EPR | electron paramagnetic resonance |

| IL-1β | interleukin 1 beta |

| LDL | low-density lipoprotein |

| LPC | lysophosphatidylcholine |

| NADPH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NAFLD | non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| T2DM | type 2 diabetes |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

References

- Fuster, J.J.; Ouchi, N.; Gokce, N.; Walsh, K. Obesity-induced changes in adipose tissue microenvironment and their impact on cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 1786–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckel, R.H.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, P.Z. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet 2005, 365, 1415–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vykoukal, D.; Davies, M.G. Biology of metabolic syndrome in a vascular patient. Vascular 2012, 20, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, K.; Uchiyama, S.; Iwata, M. Metabolic syndrome and its components as risk factors for first-ever acute ischemic noncardioembolic stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2009, 18, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottillo, S.; Filion, K.B.; Genest, J.; Joseph, L.; Pilote, L.; Poirier, P.; Rinfret, S.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Eisenberg, M.J. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 1113–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, W.Y.; Lee, Y.K.; Samy, A.L. Non-communicable diseases in the Asia-Pacific region: Prevalence, risk factors and community-based prevention. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2015, 28, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Landberg, R.; Naidoo, N.; van Dam, RM. Diet and endothelial function: From individual components to dietary patterns. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2012, 23, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davinelli, S.; Scapagnini, G. Polyphenols: A Promising nutritional approach to prevent or reduce the progression of prehypertension. High Blood Press Cardiovasc. Prev. 2016, 23, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, D.L.; Doughty, K.; Ali, A. Cocoa and chocolate in human health and disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 2779–27811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Vilas, J.A.; Quesada, A.R.; Medina, M.A. Hydroxytyrosol targets extracellular matrix remodeling by endothelial cells and inhibits both ex vivo and in vivo angiogenesis. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1741–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, G.; Godos, J.; Galvano, F.; Giovannucci, E.L. Coffee, Caffeine, and Health Outcomes: An Umbrella Review. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2017, 37, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marventano, S.; Salomone, F.; Godos, J.; Pluchinotta, F.; Del Rio, D.; Mistretta, A.; Grosso, G. Coffee and tea consumption in relation with non-alcoholic fatty liver and metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 1269–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, F.; Li, X.; Jiang, X. Coffee consumption and risk of the metabolic syndrome: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. 2016, 42, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lorenzo, A.; Curti, V.; Tenore, G.C.; Nabavi, S.M.; Daglia, M. Effects of tea and coffee consumption on cardiovascular diseases and relative risk factors: An update. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 2474–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, D.; Del Bo’, C.; Tassotti, M.; Riso, P.; Del Rio, D.; Brighenti, F.; Porrini, M. Coffee consumption and oxidative stress: A review of human intervention studies. Molecules 2016, 21, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, M.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Chen, M.; van Dam, R.M.; Hu, F.B. Caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes:a systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.M.; Lima, D.R. Coffee consumption, obesity and type 2 diabetes: A mini-review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 1345–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloomer, R.J.; Trepanowski, J.F.; Farney, T.M. Influence of acute coffee consumption on postprandial oxidative stress. Nutr. Metab. Insights 2013, 6, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakuradze, T.; Boehm, N.; Janzowski, C.; Lang, R.; Hofmann, T.; Stockis, J.P.; Albert, F.W.; Stiebitz, H.; Bytof, G.; Lantz, I.; et al. Antioxidant-rich coffee reduces DNA damage, elevates glutathione status and contributes to weight control: Results from an intervention study. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotyczka, C.; Boettler, U.; Lang, R.; Stiebitz, H.; Bytof, G.; Lantz, I.; Hofmann, T.; Marko, D.; Somoza, V. Dark roast coffee is more effective than light roast coffee in reducing body weight, and in restoring red blood cell vitamin E and glutathione concentrations in healthy volunteers. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 1582–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, R.; Steegers, E.A.; Obradov, A.; Raat, H.; Hofman, A.; Jaddoe, V.W. Maternal caffeine intake from coffee and tea, fetal growth, and the risks of adverse birth outcomes: the Generation R Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1691–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 2006, 444, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltiel, A.R.; Olefsky, J.M. Inflammatory mechanisms linking obesity and metabolic disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhoutte, P.M.; Shimokawa, H.; Tang, E.H.; Feletou, M. Endothelial dysfunction and vascular disease. Acta Physiol. 2009, 196, 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassi, D.; Desideri, G.; Ferri, C. Cardiovascular risk and endothelial dysfunction: The preferential route for atherosclerosis. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2011, 12, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micek, A.; Grosso, G.; Polak, M.; Kozakiewicz, K.; Tykarski, A.; Puch Walczak, A.; Drygas, W.; Kwasniewska, M.; Pajak, A. Association between tea and coffee consumption and prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Poland—Results from the WOBASZ II study (2013–2014). Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushima, Y.; Ohie, T.; Yonekawa, Y.; Yonemoto, K.; Aizawa, H.; Mori, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Taguchi, C.; et al. Coffee and green tea as a large source of antioxidant polyphenols in the Japanese population. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesil, A.; Yilmaz, Y. Review article: Coffee consumption, the metabolic syndrome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 38, 1038–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stalmach, A.; Mullen, W.; Nagai, C.; Crozier, A. On-line HPLC analysis of the antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds in brewed paper-filtered coffee. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 18, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, M.; Testa, M.F. Redox ingredients for oxidative stress prevention: The unexplored potentiality of coffee. Clin. Dermatol. 2009, 27, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andriantsitohaina, R.; Auger, C.; Chataigneau, T.; Etienne-Selloum, N.; Li, H.; Martinez, M.C.; Schini-Kerth, V.B.; Laher, I. Molecular mechanisms of the cardiovascular protective effects of polyphenols. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 1532–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, A.; Yamamoto, N.; Jokura, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Fujii, A.; Tokimitsu, I.; Saito, I. Chlorogenic acid attenuates hypertension and improves endothelial function in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Hypertens. 2006, 24, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stalmach, A.; Steiling, H.; Williamson, G.; Crozier, A. Bioavailability of chlorogenic acids following acute ingestion of coffee by humans with an ileostomy. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 501, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natella, F.; Nardini, M.; Giannetti, I.; Dattilo, C.; Scaccini, C. Coffee drinking influences plasma antioxidant capacity in humans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 6211–6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreasen, M.F.; Landbo, A.K.; Christensen, L.P.; Hansen, A.; Meyer, A.S. Antioxidant effects of phenolic rye (Secale cereale L.) extracts, monomeric hydroxycinnamates, and ferulic acid dehydrodimers on human low-density lipoproteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 4090–4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godos, J.; Pluchinotta, F.R.; Marventano, S.; Buscemi, S.; Volti, G.L.; Galvano, F.; Grosso, G. Coffee components and cardiovascular risk: Beneficial and detrimental effects. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 65, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon-Carmona, J.R.; Galano, A. Is caffeine a good scavenger of oxygenated free radicals? J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 4538–4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.S.; Devasagayam, T.P.; Jayashree, B.; Kesavan, P.C. Mechanism of protection against radiation-induced DNA damage in plasmid pBR322 by caffeine. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2001, 77, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brezova, V.; Slebodova, A.; Stasko, A. Coffee as a source of antioxidants: An EPR study. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. Caffein may antioxidant ability and oxygen radical absorbing capacity and inhibition of LDL peroxidation. Clin. Chim. Acta 2000, 295, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, G.C.; Chung, D.Y. Antioxidant effects of extracts from Cassia tora L. prepared under different degrees of roasting on the oxidative damage to biomolecules. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edeas, M.; Attaf, D.; Mailfert, A.S.; Nasu, M.; Joubet, R. Maillard reaction, mitochondria and oxidative stress: Potential role of antioxidants. Pathol. Biol. 2010, 58, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekedam, E.K.; Loots, M.J.; Schols, H.A.; Van Boekel, M.A.; Smit, G. Roasting effects on formation mechanisms of coffee brew melanoidins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 7138–7145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opitz, S.E.; Smrke, S.; Goodman, B.A.; Keller, M.; Schenker, S.; Yeretzian, C. Antioxidant generation during coffee roasting: A comparison and Interpretation from three complementary assays. Foods 2014, 3, 586–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driessen, M.T.; Koppes, L.L.; Veldhuis, L.; Samoocha, D.; Twisk, J.W. Coffee consumption is not related to the metabolic syndrome at the age of 36 years: The Amsterdam Growth and Health Longitudinal Study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 63, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprioli, G.; Cortese, M.; Sagratini, G.; Vittori, S. The influence of different types of preparation (espresso and brew) on coffee aroma and main bioactive constituents. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 66, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, P.R.; Ferrari, G.S.; Ferrari, C.K. Diet, sleep and metabolic syndrome among a legal Amazon population. Braz. Clin. Nutr. Res. 2015, 4, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, G.; Micek, A.; Godos, J.; Sciacca, S.; Pajak, A.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Galvano, F. Coffee consumption and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality in smokers and non-smokers: A dose-response meta-analysis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 31, 1191–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelis, M.C.; El-Sohemy, A.; Kabagambe, E.K.; Campos, H. Coffee, CYP1A2 genotype, and risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA 2006, 295, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palatini, P.; Ceolotto, G.; Ragazzo, F.; Dorigatti, F.; Saladini, F.; Papparella, I.; Mos, L.; Zanata, G.; Santonastaso, M. CYP1A2 genotype modifies the association between coffee intake and the risk of hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2009, 27, 1594–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordestgaard, A.T.; Thomsen, M.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Coffee intake and risk of obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: A Mendelian randomization study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Kim, K.; Park, S.M. Association between the Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome and the Level of Coffee Consumption among Korean Women. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suliga, E.; Kozie, D.; Ciesla, E.; Rebak, D.; Gluszek, S. Coffee consumption and the occurrence and intensity of metabolic syndrome: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 68, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, G.; Marventano, S.; Galvano, F.; Pajak, A.; Mistretta, A. Factors associated with metabolic syndrome in a Mediterranean population: Role of caffeinated beverages. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, G.; Stepaniak, U.; Micek, A.; Topor-Madry, R.; Pikhart, H.; Szafraniec, K.; Pajak, A. Association of daily coffee and tea consumption and metabolic syndrome: Results from the Polish arm of the HAPIEE study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Cho, S.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Park, K. Instant coffee consumption may be associated with higher risk of metabolic syndrome in Korean adults. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 106, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, A.M.; Chiu, Y.H.; Chen, L.S.; Wu, H.M.; Huang, C.C.; Boucher, B.J.; Chen, T.H. A population-based study of the association between betel-quid chewing and the metabolic syndrome in men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Takami, H.; Nakamoto, M.; Uemura, H.; Katsuura, S.; Yamaguchi, M.; Hiyoshi, M.; Sawachika, F.; Juta, T.; Arisawa, K. Inverse correlation between coffee consumption and prevalence of metabolic syndrome: baseline survey of the Japan Multi-Institutional Collaborative Cohort (J-MICC) Study in Tokushima, Japan. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 23, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.S.; Chang, Y.F.; Liu, P.Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Tsai, Y.S.; Wu, C.H. Smoking, habitual tea drinking and metabolic syndrome in elderly men living in rural community:the Tianliao old people (TOP) study 02. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38874. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura, H.; Mure, K.; Nishio, N.; Kitano, N.; Nagai, N.; Takeshita, T. Relationship between coffee consumption and prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Japanese civil servants. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 22, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutsey, P.L.; Steffen, L.M.; Stevens, J. Dietary intake and the development of the metabolic syndrome: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Circulation 2008, 117, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilsgaard, T.; Jacobsen, B.K. Lifestyle factors and incident metabolic syndrome. The Tromso Study 1979–2001. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2007, 78, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hino, A.; Adachi, H.; Enomoto, M.; Furuki, K.; Shigetoh, Y.; Ohtsuka, M.; Kumagae, S.; Hirai, Y.; Jalaldin, A.; Satoh, A.; et al. Habitual coffee but not green tea consumption is inversely associated with metabolic syndrome: an epidemiological study in a general Japanese population. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2007, 76, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavie, C.J.; Milani, R.V.; Ventura, H.O. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: Risk factor, paradox, and impact of weight loss. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 53, 1925–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Huang, T.; Kang, J.H.; Zheng, Y.; Jensen, M.K.; Wiggs, J.L.; Pasquale, L.R.; Fuchs, C.S.; Campos, H.; Rimm, E.B.; et al. Habitual coffee consumption and genetic predisposition to obesity: Gene-diet interaction analyses in three US prospective studies. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haidari, F.; Samadi, M.; Mohammadshahi, M.; Jalali, M.T.; Engali, K.A. Energy restriction combined with green coffee bean extract affects serum adipocytokines and the body composition in obese women. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 26, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, W. Coffee and caffeine intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- InterAct Consortium. Investigation of gene-diet interactions in the incretin system and risk of type 2 diabetes: The EPIC-InterAct study. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 2613–2621. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.Y.; Pi-Sunyer, F.X.; Chen, C.C.; Davidson, L.E.; Liu, C.S.; Li, T.C.; Wu, M.F.; Li, C.I.; Chen, W.; Lin, C.C. Coffee consumption is inversely associated with type 2 diabetes in Chinese. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 41, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baspinar, B.; Eskici, G.; Ozcelik, A.O. How coffee affects metabolic syndrome and its components. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 2089–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dam, R.M.; Willett, W.C.; Manson, J.E.; Hu, F.B. Coffee, caffeine, and risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective cohort study in younger and middle-aged U.S. women. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, M.K.; Leung, G.M.; Schooling, C.M. Habitual coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes, ischemic heart disease, depression and Alzheimer’s disease: A Mendelian randomization study. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, M.; Okamoto, N.; Saibara, T. The latest idea in NAFLD/NASH pathogenesis. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 3, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yki-Jarvinen, H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as a cause and a consequence of metabolic syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, G.B.; Chow, W.C.; Wang, R.; Yuan, J.M.; Koh, W.P. Coffee, alcohol and other beverages in relation to cirrhosis mortality: The Singapore Chinese Health Study. Hepatology 2014, 60, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelber-Sagi, S.; Salomone, F.; Webb, M.; Lotan, R.; Yeshua, H.; Halpern, Z.; Santo, E.; Oren, R.; Shibolet, O. Coffee consumption and nonalcoholic fatty liver onset: A prospective study in the general population. Transl. Res. 2015, 165, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodge, A.; Lim, S.; Goh, E.; Wong, O.; Marsh, P.; Knight, V.; Sievert, W.; de Courten, B. Coffee Intake Is Associated with a Lower Liver Stiffness in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Hepatitis C, and Hepatitis B. Nutrients 2017, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, H.B.; Masterton, G.S.; Hayes, P.C. An epidemiological study of the association of coffee with chronic liver disease. Scott. Med. J. 2013, 58, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uemura, H.; Katsuura-Kamano, S.; Yamaguchi, M.; Nakamoto, M.; Hiyoshi, M.; Arisawa, K. Consumption of coffee, not green tea, is inversely associated with arterial stiffness in Japanese men. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, J.P.; Loria, C.M.; Steffen, L.M.; Zhou, X.; van Horn, L.; Siscovick, D.S.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Carr, J.J. Coffee, decaffeinated coffee, caffeine, and tea consumption in young adulthood and atherosclerosis later in life: The CARDIA study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 2059–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, P.E.; Zhao, D.; Frazier-Wood, A.C.; Michos, E.D.; Averill, M.; Sandfort, V.; Burke, G.L.; Polak, J.F.; Lima, J.A.; Post, W.S.; et al. Associations of coffee, tea, and caffeine intake with coronary artery calcification and cardiovascular events. Am. J. Med. 2017, 130, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, Y.R.; Gadiraju, T.V.; Ellison, R.C.; Hunt, S.C.; Carr, J.J.; Heiss, G.; Arnett, D.K.; Pankow, J.S.; Gaziano, J.M.; Djousse, L. Coffee consumption and calcified atherosclerotic plaques in the coronary arteries: The NHLBI Family Heart Study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2017, 17, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, G.; Micek, A.; Godos, J.; Pajak, A.; Sciacca, S.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Galvano, F.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A. Long-Term Coffee Consumption Is Associated with Decreased Incidence of New-Onset Hypertension: A Dose—Response Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2017, 9, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, G.; Jousilahti, P.; Nissinen, A.; Bidel, S.; Antikainen, R.; Tuomilehto, J. Coffee consumption and the incidence of antihypertensive drug treatment in Finnish men and women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 86, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grosso, G.; Stepaniak, U.; Polak, M.; Micek, A.; Topor-Madry, R.; Stefler, D.; Szafraniec, K.; Pajak, A. Coffee consumption and risk of hypertension in the Polish arm of the HAPIEE cohort study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonita, J.S.; Mandarano, M.; Shuta, D.; Vinson, J. Coffee and cardiovascular disease: In vitro, cellular, animal, and human studies. Pharmacol. Res. 2007, 55, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Ballevre, O.; Luo, H.; Zhang, W. Antihypertensive effects and mechanisms of chlorogenic acids. Hypertens. Res. 2012, 35, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandona, P.; Aljada, A.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Inflammation: The link between insulin resistance, obesity and diabetes. Trends Immunol. 2004, 25, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paoletti, R.; Bolego, C.; Poli, A.; Cignarella, A. Metabolic syndrome, inflammation and atherosclerosis. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2006, 2, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjoholm, A.; Nystrom, T. Endothelial inflammation in insulin resistance. Lancet 2005, 365, 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kougias, P.; Chai, H.; Lin, P.H.; Yao, Q.; Lumsden, A.B.; Chen, C. Effects of adipocyte—Derived cytokines on endothelial functions: Implication of vascular disease. J. Surg. Res. 2005, 126, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochiai, R.; Sugiura, Y.; Otsuka, K.; Katsuragi, Y.; Hashiguchi, T. Coffee bean polyphenols ameliorate postprandial endothelial dysfunction in healthy male adults. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 66, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.Y.; Fu, L.; Li, C.Y.; Xu, L.P.; Zhang, L.X.; Zhang, W.M. Quercetin, Hyperin and chlorogenic acid improve endothelial function by antioxidant, antiinflammatory, and ACE inhibitory effects. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, R.; Hodgson, J.M.; Mas, E.; Croft, K.D.; Ward, N.C. Chlorogenic acid improves ex vivo vessel function and protects endothelial cells against HOCl-induced oxidative damage, via increased production of nitric oxide and induction of Hmox-1. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 27, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajikawa, M.; Maruhashi, T.; Hidaka, T.; Nakano, Y.; Kurisu, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Iwamoto, Y.; Kishimoto, S.; Matsui, S.; Aibara, Y.; et al. Coffee with a high content of chlorogenic acids and low content of hydroxyhydroquinone improves postprandial endothelial dysfunction in patients with borderline and stage 1 hypertension. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashi, Y.; Noma, K.; Yoshizumi, M.; Kihara, Y. Endothelial function and oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. Circ. J. 2009, 73, 411–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oboh, G.; Agunloye, O.M.; Adefegha, S.A.; Akinyemi, A.J.; Ademiluyi, A.O. Caffeic and chlorogenic acids inhibit key enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes (in vitro): A comparative study. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 26, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akerele, O.A.; Cheema, S.K. Fatty acyl composition of lysophosphatidylcholine is important in atherosclerosis. Med. Hypotheses 2015, 85, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.J.; Im, S.S.; Song, D.K.; Bae, J.H. Effects of chlorogenic acid on intracellular calcium regulation in lysophosphatidylcholine-treated endothelial cells. BMB Rep. 2017, 50, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griendling, K.K.; Sorescu, D.; Ushio-Fukai, M. NAD(P)H oxidase: Role in cardiovascular biology and disease. Circ. Res. 2000, 86, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).