Polyphyllin II Triggers Pyroptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Modulation of the ROS/NLRP3/Caspase-1/GSDMD Axis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cells and Animals

2.3. Cell Viability Assay

2.4. Apoptosis Assay

2.5. Cell Scratch Assay

2.6. Observation of Cell Morphology

2.7. Transmission Electron Microscopy

2.8. LDH Release Assay

2.9. ROS Assay

2.10. Ca2+ Assay

2.11. ELISA Assay

2.12. RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) Analysis

2.13. Tumor Xenograft Animal Experiments

2.14. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

2.15. Blood Biochemical Index Detection

2.16. Western Blot Analysis of Tumor

2.17. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. PPII Enhanced Cytotoxicity of HCC Cells

3.2. PPII Induced HCC Cell Pyroptosis

3.3. ROS Promote Pyroptosis in HepG2 Cells

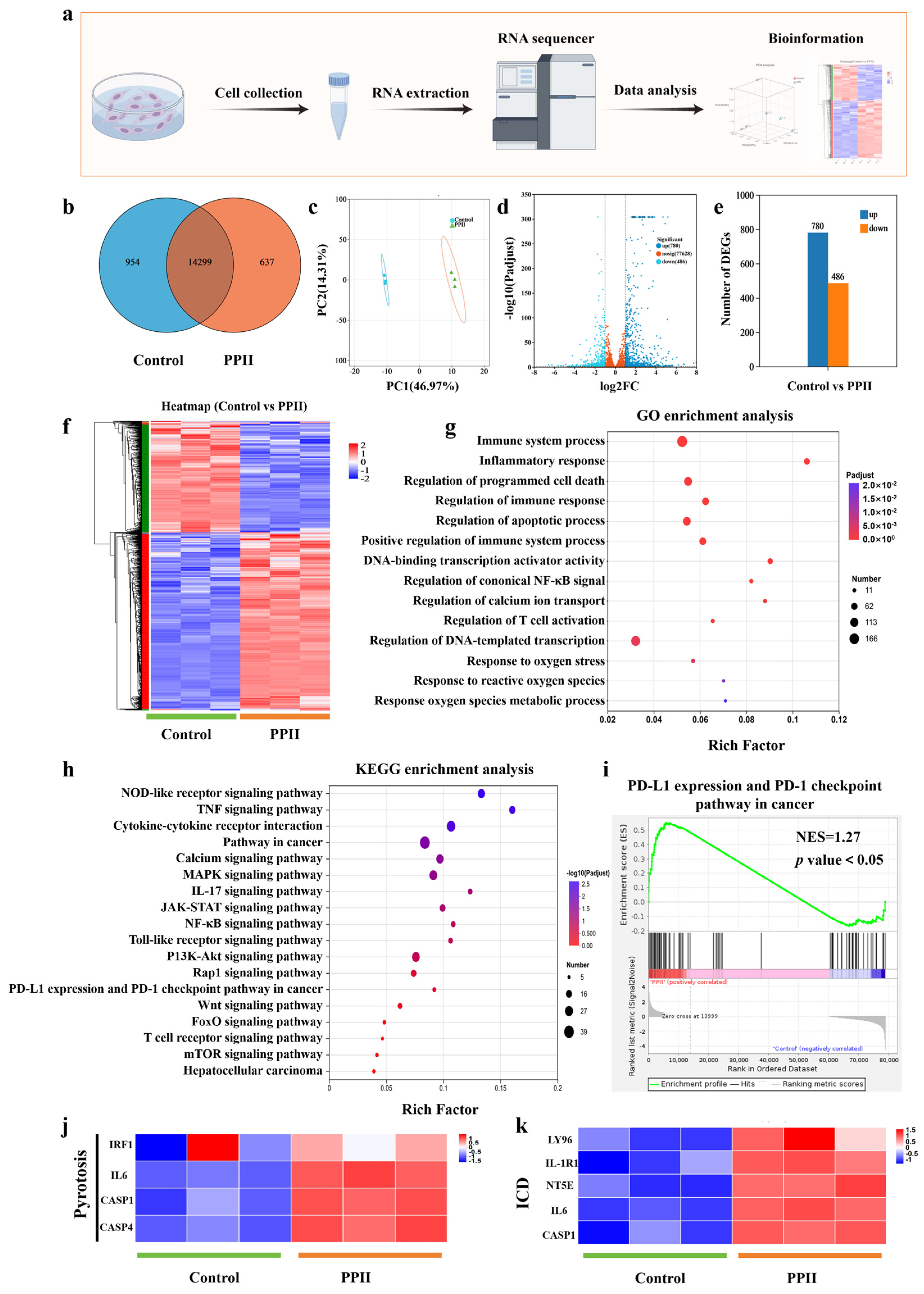

3.4. Anti-Tumor Mechanism Analysis of PPII

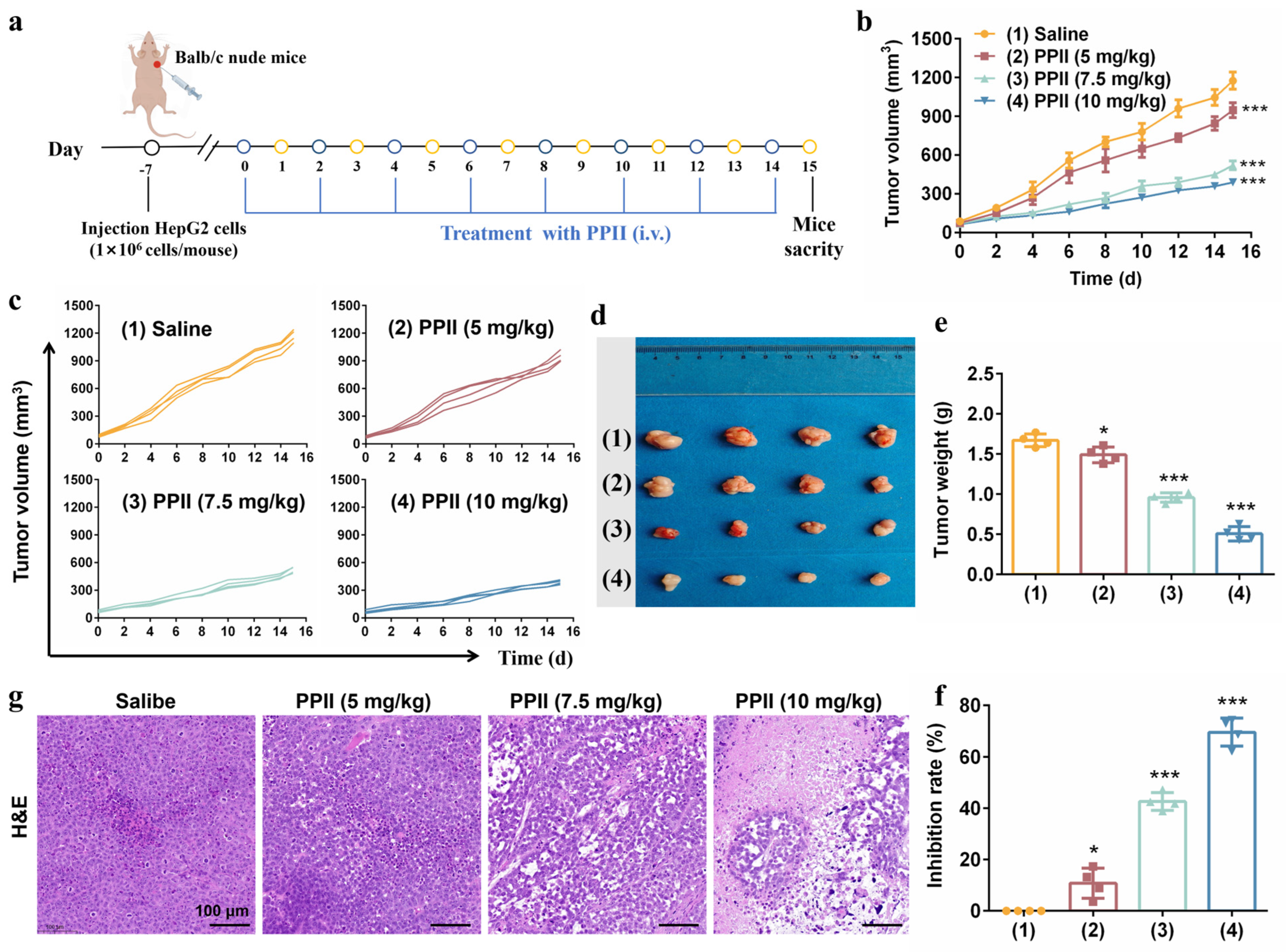

3.5. PPII Inhibited the Tumor Growth in Mice Models

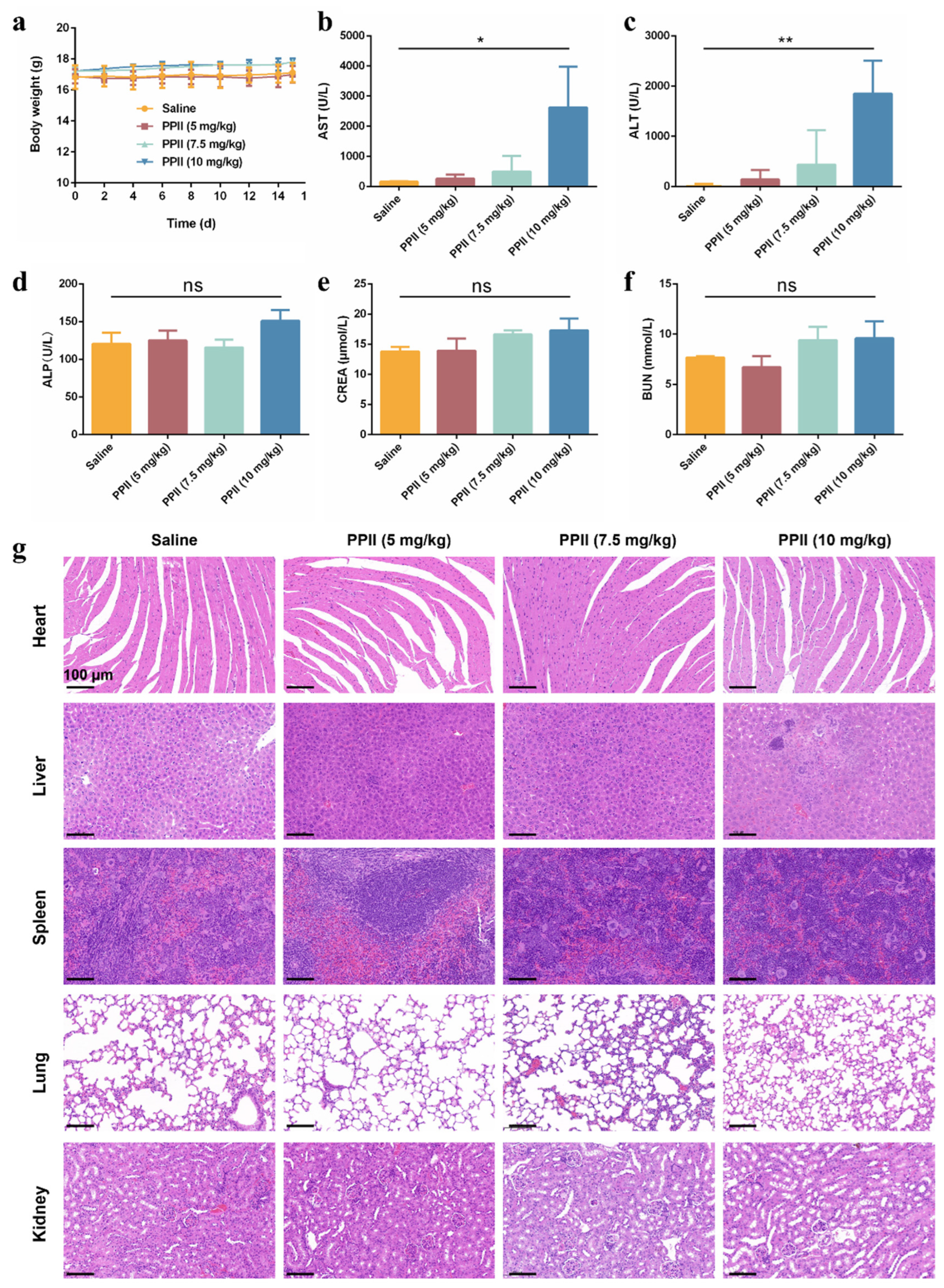

3.6. The In Vivo Biosafety of PPII

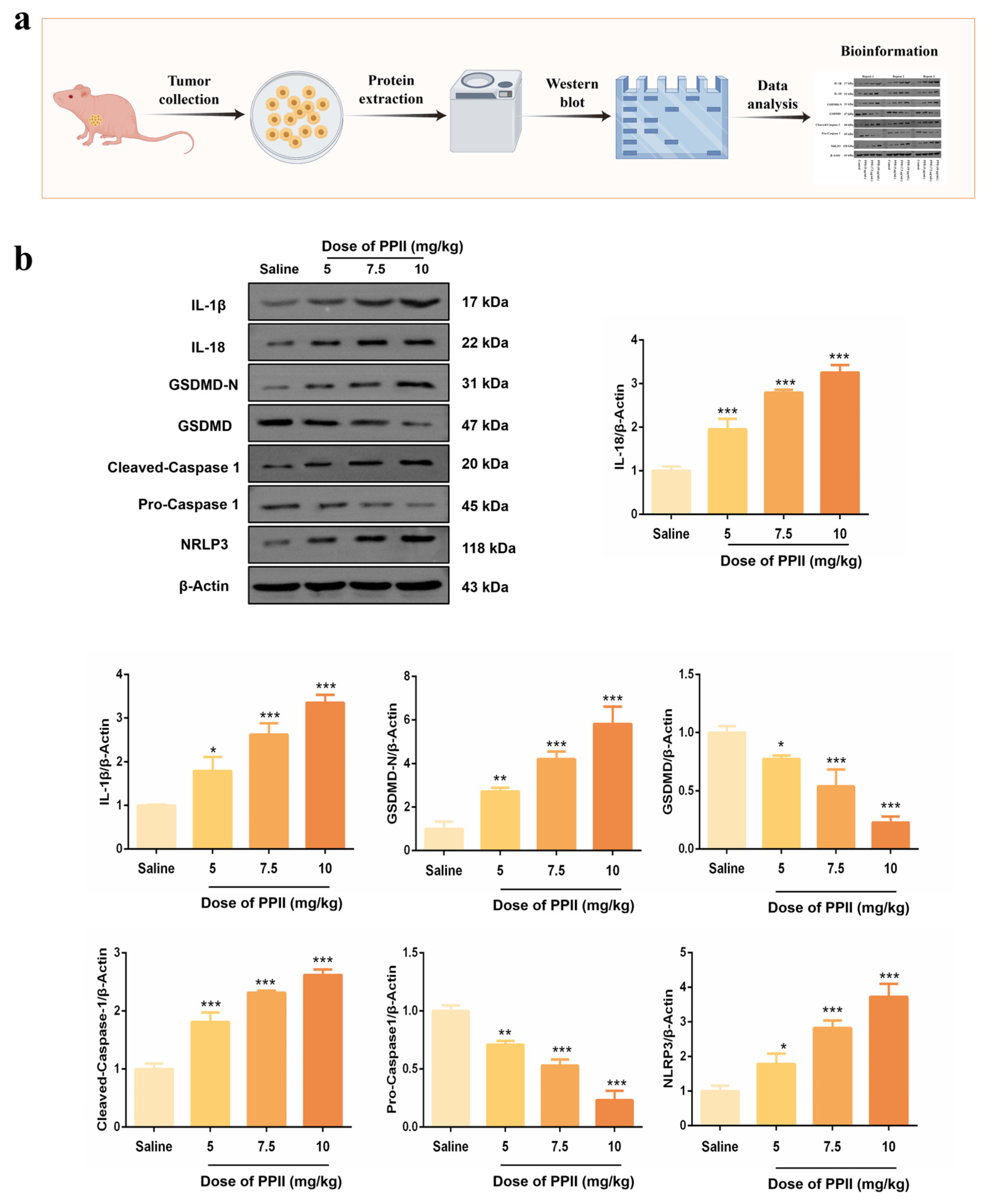

3.7. PPII Induced NLRP3/Caspase-1/GSDMD-Mediated Pyroptosis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fang, Y.; Tian, S.; Pan, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, Q.; Tang, Y.; Yu, T.; Wu, X.; Shi, Y.; Ma, P.; et al. Pyroptosis: A new frontier in cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 121, 109595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Li, S.L.; Zhang, X.Y.; Jiang, F.L.; Guo, Q.L.; Jiang, P.; Liu, Y. “Multi-in-One” Yolk-Shell Structured Nanoplatform Inducing Pyroptosis and Antitumor Immune Response Through Cascade Reactions. Small 2024, 20, e2400254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdette, B.E.; Esparza, A.N.; Zhu, H.; Wang, S. Gasdermin D in pyroptosis. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 2768–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ding, J.; Wang, C.; Zhou, X.; Gao, W.; Huang, H.; Shao, F.; Liu, Z. A bioorthogonal system reveals antitumour immune function of pyroptosis. Nature 2020, 579, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Qiu, W.; Li, S.J.; Wang, S.; Xie, J.; Yang, Q.C.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Z.; Sun, Z.J. A Dual-Responsive STAT3 Inhibitor Nanoprodrug Combined with Oncolytic Virus Elicits Synergistic Antitumor Immune Responses by Igniting Pyroptosis. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2209379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, Q.C.; Song, A.; Zhang, M.J.; Wang, W.D.; Liu, Y.T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.M.; et al. Dual-Responsive Epigenetic Inhibitor Nanoprodrug Combined with Oncolytic Virus Synergistically Boost Cancer Immunotherapy by Igniting Gasdermin E-Mediated Pyroptosis. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 20167–20180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Chen, H.; Tan, J.; Meng, Q.; Zheng, P.; Ma, P.; Lin, J. ZIF-8 Nanoparticles Evoke Pyroptosis for High-Efficiency Cancer Immunotherapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202215307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shi, D.; Guo, M.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, X. Radiofrequency-Activated Pyroptosis of Bi-Valent Gold Nanocluster for Cancer Immunotherapy. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, P.; Chen, Z.; Xia, Y.; Qiao, C.; Liu, W.; Deng, H.; Li, J.; Ning, P.; et al. Pyroptosis in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Theranostics 2022, 12, 4310–4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Fu, X.; Lin, Y.; Cao, C.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, P. Caspase-3/GSDME mediated pyroptosis: A potential pathway for sepsis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 124, 111022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Jin, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Lv, X.; Ren, L.; Yang, J.; Chen, D.; Wang, B.; Yang, W.; Chen, L.; et al. HDAC11 promotes both NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD and caspase-3/GSDME pathways causing pyroptosis via ERG in vascular endothelial cells. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Xu, C.; Mao, D.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, N.; Wang, M.; Mao, N.; Wang, T.; Li, Y. Recent advances in pyroptosis, liver disease, and traditional Chinese medicine: A review. Phytother. Res. 2023, 37, 5473–5494. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, R.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Q.Q.; He, J.; Han, S.; Gao, H.; Feng, Y.; Yang, S. Cucurbitacin B inhibits non-small cell lung cancer in vivo and in vitro by triggering TLR4/NLRP3/GSDMD-dependent pyroptosis. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 170, 105748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Fan, J.; Zhou, N.; Liang, J.; Xiao, C.; Tong, C.; Wang, W.; Liu, B. Biomimetic Prussian blue nanocomplexes for chemo-photothermal treatment of triple-negative breast cancer by enhancing ICD. Biomaterials 2023, 303, 122369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Chen, G.; Zhong, M.; Lin, L.; Mai, Z.; Tang, Y.; Chen, G.; Ma, W.; Li, G.; Yang, Y.; et al. An acid-responsive MOF nanomedicine for augmented anti-tumor immunotherapy via a metal ion interference-mediated pyroptotic pathway. Biomaterials 2023, 302, 122333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Y.; Liao, Y.; Liang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhao, B.; Wen, G. Multifunctional nanoagent for enhanced cancer radioimmunotherapy via pyroptosis and cGAS-STING activation. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.T.; Chang, A.Q.; Peng, H.; Liu, J.; Yao, A.N.; Ruan, Y.D.; Zhang, P.Z.; Wang, T.S.; Qu, C.H.; Yin, X.B.; et al. Preparation and anti-tumor effect in hepatocellular carcinoma treatment of AS1411 aptamer-targeted polyphyllin II-loaded PLGA nanoparticles. J. Sci.-Adv. Mater. Dev. 2024, 9, 100755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Xin, M.; Xu, J.; Xiang, X.; Li, X.; Jiang, J.; Jia, X. Polyphyllin II induced apoptosis of NSCLC cells by inhibiting autophagy through the mTOR pathway. Pharm. Biol. 2022, 60, 1781–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, W.; Wang, Z.; Gao, J.; Ohno, Y. Polyphyllin II inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2024, 30, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zou, J.; Bui-Nguyen, T.M.; Bai, P.; Gao, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Xiao, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Paris saponin II of Rhizoma Paridis--a novel inducer of apoptosis in human ovarian cancer cells. Biosci. Trends 2012, 6, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.K.; Sun, H.T.; Jiang, X.L.; Chen, Y.F.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.Q.; Zhang, Z.; Sze, S.C.W.; Zhu, P.L.; et al. Polyphyllin II Induces Protective Autophagy and Apoptosis via Inhibiting PI3K/AKT/mTOR and STAT3 Signaling in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messmer, M.N.; Snyder, A.G.; Oberst, A. Comparing the effects of different cell death programs in tumor progression and immunotherapy. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Xu, J.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Liang, C.; Hua, J.; Meng, Q.; Yu, X.; Shi, S. Ferroptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis in anticancer immunity. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aachoui, Y.; Sagulenko, V.; Miao, E.A.; Stacey, K.J. Inflammasome-mediated pyroptotic and apoptotic cell death, and defense against infection. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013, 16, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Gan, F.; Chen, X.; Deng, K.; Crowe, S.A.; Hudson, G.A.; Belcher, M.S.; Schmidt, M.; Astolfi, M.C.T.; et al. Complete biosynthesis of QS-21 in engineered yeast. Nature 2024, 629, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, M.; Minns, M.; Greenberg, E.N.; Diaz-Aponte, J.; Pestonjamasp, K.; Johnson, J.L.; Rathkey, J.K.; Abbott, D.W.; Wang, K.; Shao, F.; et al. N-GSDMD trafficking to neutrophil organelles facilitates IL-1beta release independently of plasma membrane pores and pyroptosis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Peng, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Yi, L.; Long, Y. Simvastatin induces pyroptosis via ROS/caspase-1/GSDMD pathway in colon cancer. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Gao, M.; Shi, X.; Yin, Y.; Liu, H.; Xie, R.; Huang, C.; Zhang, W.; Xu, S. Quercetin attenuates SiO(2)-induced ZBP-1-mediated PANoptosis in mouse neuronal cells via the ROS/TLR4/NF-kappab pathway. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, B.R. Ferroptosis turns 10: Emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic applications. Cell 2022, 185, 2401–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Ding, B.; Jiang, Z.; Xu, W.; Li, G.; Ding, J.; Chen, X. Ultrasound-Augmented Mitochondrial Calcium Ion Overload by Calcium Nanomodulator to Induce Immunogenic Cell Death. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 2088–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomello, M.; Drago, I.; Pizzo, P.; Pozzan, T. Mitochondrial Ca2+ as a key regulator of cell life and death. Cell Death Differ. 2007, 14, 1267–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Zhu, J.X.; Wang, S.H.; Li, S.Y.; Jiaoting, E.; Hu, J.H.; Mou, R.S.; Ding, H.; Yang, P.P.; Xie, R. A Copper/Ferrous-Engineering Redox Homeostasis Disruptor for Cuproptosis/Ferroptosis Co-Activated Nanocatalytic Therapy in Liver Cancer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2402022. [Google Scholar]

- Klotz, L.O.; Sanchez-Ramos, C.; Prieto-Arroyo, I.; Urbanek, P.; Steinbrenner, H.; Monsalve, M. Redox regulation of FoxO transcription factors. Redox. Biol. 2015, 6, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, K.; Shi, Z.D.; Wei, L.Y.; Dong, Y.; Ma, Y.Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, G.Y.; Cao, M.Y.; Dong, J.J.; Chen, Y.A.; et al. Research progress of therapeutic effects and drug resistance of immunotherapy based on PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Drug Resist. Updates 2023, 66, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toldo, S.; Abbate, A. The role of the NLRP3 inflammasome and pyroptosis in cardiovascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J. Steroidal saponins PPI/CCRIS/PSV induce cell death in pancreatic cancer cell through GSDME-dependent pyroptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 673, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhou, W.; Yao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ma, X.; Zhang, B.; Yang, Z.; Tang, B.; Zhu, H.; Li, N. Targeted Positron Emission Tomography-Tracked Biomimetic Codelivery Synergistically Amplifies Ferroptosis and Pyroptosis for Inducing Lung Cancer Regression and Anti-PD-L1 Immunotherapy Efficacy. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 31401–31420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ma, X.; Liu, W.; Hu, Q.; Yang, H. Targeting Pyroptosis through Lipopolysaccharide-Triggered Noncanonical Pathway for Safe and Efficient Cancer Immunotherapy. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 8725–8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, N.; Chen, J.; Tao, Q.; Lu, C.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Peng, C. Clofarabine induces tumor cell apoptosis, GSDME-related pyroptosis, and CD8(+) T-cell antitumor activity via the non-canonical P53/STING pathway. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e010252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Shi, X.; Peng, Y.; Hu, J.; Ding, J.; Zhou, W. Anti-PD-L1 DNAzyme Loaded Photothermal Mn(2+)/Fe(3+) Hybrid Metal-Phenolic Networks for Cyclically Amplified Tumor Ferroptosis-Immunotherapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, e2102315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Chen, P.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Chen, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, S.; Ye, L.; He, Y.; et al. cGAS-STING, an important pathway in cancer immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zheng, J.; Liang, N.; Zhang, X.; Shabiti, S.; Wang, Z.; Yu, S.; Pan, Z.Y.; Li, W.; Cai, L. Bioorthogonal/Ultrasound Activated Oncolytic Pyroptosis Amplifies In Situ Tumor Vaccination for Boosting Antitumor Immunity. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 9413–9430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhaoyun, L.; Wang, H.; Yang, C.; Zhao, X.; Hui, L.; Song, J.; Ding, K.; Fu, R. Enhancing antitumor immunity via ROS-ERS and pyroptosis-induced immunogenic cell death in multiple myeloma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e011717. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.X.; Cai, M.R.; Yin, D.G.; Zhu, R.Y.; Fu, T.T.; Liao, S.L.; Du, Y.J.; Kong, J.H.; Ni, J.; Yin, X.B. Functional metal-organic framework nanoparticles loaded with polyphyllin I for targeted tumor therapy. J. Sci.-Adv. Mater. Dev. 2023, 8, 100548. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Z.; Zhao, C.; Wang, M.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, W.; Han, T.; Xia, Q.; Han, Z.; Lin, R.; Li, X. Hepatotoxicity assessment of Rhizoma Paridis in adult zebrafish through proteomes and metabolome. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 121, 109558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Fu, J.; Peng, H.; He, Y.; Chang, A.; Zhang, H.; Hao, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; et al. Co-delivery of polyphyllin II and IR780 PLGA nanoparticles induced pyroptosis combined with photothermal to enhance hepatocellular carcinoma immunotherapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, H.; Ni, B.; Chen, Q.; Wang, W.; Guo, Z.; Wang, N.; Chen, R.; Yin, X.; Qu, C.; Ni, J.; et al. Polyphyllin II Triggers Pyroptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Modulation of the ROS/NLRP3/Caspase-1/GSDMD Axis. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010075

Huang H, Ni B, Chen Q, Wang W, Guo Z, Wang N, Chen R, Yin X, Qu C, Ni J, et al. Polyphyllin II Triggers Pyroptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Modulation of the ROS/NLRP3/Caspase-1/GSDMD Axis. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010075

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Huating, Boran Ni, Qi Chen, Wenqi Wang, Zishuo Guo, Nan Wang, Rui Chen, Xingbin Yin, Changhai Qu, Jian Ni, and et al. 2026. "Polyphyllin II Triggers Pyroptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Modulation of the ROS/NLRP3/Caspase-1/GSDMD Axis" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010075

APA StyleHuang, H., Ni, B., Chen, Q., Wang, W., Guo, Z., Wang, N., Chen, R., Yin, X., Qu, C., Ni, J., & Dong, X. (2026). Polyphyllin II Triggers Pyroptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Modulation of the ROS/NLRP3/Caspase-1/GSDMD Axis. Antioxidants, 15(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010075