Integration of Serum and Liver Metabolomics with Antioxidant Biomarkers Elucidates Dietary Energy Modulation of the Fatty Acid Profile in Donkey Meat

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design, Diet, and Feeding Management

| Index | 1–45 d | 46–90 d | 91–135 d | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEG | MEG | HEG | LEG | MEG | HEG | LEG | MEG | HEG | |

| Digestible energy, MJ/kg 1 | 12.08 | 13.38 | 14.40 | 13.01 | 14.27 | 15.60 | 13.54 | 14.93 | 16.23 |

| Crude protein | 14.53 | 15.06 | 15.06 | 13.02 | 13.04 | 13.17 | 12.48 | 12.67 | 12.72 |

| Ether extract | 5.69 | 6.43 | 7.13 | 6.06 | 6.50 | 6.97 | 6.47 | 6.95 | 7.32 |

| Neutral detergent fiber | 57.29 | 55.38 | 50.99 | 48.01 | 46.7 | 44.21 | 46.94 | 43.86 | 41.63 |

| Acid detergent fiber | 37.90 | 38.41 | 36.54 | 31.19 | 30.85 | 28.72 | 31.95 | 30.29 | 27.02 |

| Calcium | 1.33 | 1.38 | 1.44 | 1.48 | 1.45 | 1.43 | 1.36 | 1.40 | 1.45 |

| Phosphorus | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.63 |

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Fatty Acid Contents in Longissimus Dorsi Muscle, Subcutaneous Fat, Serum, and Liver

2.4. Lipid Metabolism Enzyme Content

2.5. Lipid Metabolism Genes and PPARγ mRNA Expression

2.6. Antioxidant Activities and Immune Signaling Molecule Levels in Serum and Liver

2.7. Serum and Liver Metabolome Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Fatty Acid Contents

| Tissue | Fatty Acids | LEG | MEG | HEG | SEM | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| longissimus thoracis muscle | n-6PUFA | |||||

| C18:2n6t | 0.042 b | 0.058 a | 0.051 ab | 0.003 | 0.014 | |

| C18:2n6c | 24.936 b | 26.322 ab | 27.169 a | 0.593 | 0.045 | |

| C18:3n6 | 0.038 | 0.034 | 0.038 | 0.002 | 0.374 | |

| C22:2n6 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.002 | 0.999 | |

| n-3PUFA | ||||||

| C18:3n3 | 1.348 b | 1.506 b | 1.809 a | 0.074 | 0.001 | |

| C20:3n3 | 0.130 b | 0.242 a | 0.218 a | 0.028 | 0.033 | |

| C20:5n3 | 0.053 | 0.068 | 0.050 | 0.011 | 0.974 | |

| Sum and Ratio 1 | ||||||

| PUFA | 27.700 | 28.300 | 29.104 | 0.484 | 0.145 | |

| n-3PUFA | 1.590 c | 1.894 b | 2.185 a | 0.076 | <0.001 | |

| n-6PUFA | 25.312 b | 27.410 a | 27.394 a | 0.609 | 0.036 | |

| n-6/n-3 | 15.094 a | 13.825 b | 12.063 c | 0.387 | <0.001 | |

| U/S | 1.699 ab | 1.640 b | 1.817 a | 0.043 | 0.026 | |

| P/S | 0.732 | 0.752 | 0.834 | 0.035 | 0.124 | |

| subcutaneous adipose | n-6PUFA | |||||

| C18:2n6t | 0.008 b | 0.012 a | 0.012 a | 0.001 | <0.001 | |

| C18:2n6 c | 25.436 c | 26.641 b | 29.392 a | 0.379 | <0.001 | |

| C18:3n6 | 0.022 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.001 | 0.800 | |

| C22:2n6 | 0.025 a | 0.018 b | 0.020 b | 0.001 | 0.004 | |

| n-3PUFA | ||||||

| C18:3n3 | 2.800 b | 3.140 b | 4.094 a | 0.165 | <0.001 | |

| C20:3n3 | 0.077 | 0.055 | 0.052 | 0.010 | 0.165 | |

| C20:5n3 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.221 | |

| Sum and Ratio 1 | ||||||

| PUFA | 29.421 b | 30.090 b | 34.419 a | 0.340 | <0.001 | |

| n-3PUFA | 2.917 b | 3.229 b | 4.171 a | 0.167 | <0.001 | |

| n-6PUFA | 26.446 b | 26.399 b | 30.335 a | 0.473 | <0.001 | |

| n-6/n-3 | 9.174 a | 8.166 b | 7.781 b | 0.236 | 0.005 | |

| U/S | 2.094 | 2.117 | 2.123 | 0.083 | 0.968 | |

| P/S | 0.910 b | 0.980 ab | 1.079 a | 0.039 | 0.020 | |

| serum | n-6PUFA | |||||

| C18:2n6t | 0.215 b | 0.210 b | 0.370 a | 0.028 | 0.002 | |

| C18:2n6c | 37.510 b | 38.487 b | 39.962 a | 0.351 | <0.001 | |

| C18:3n6 | 0.050 a | 0.021 b | 0.007 b | 0.006 | <0.001 | |

| C22:2n6 | 0.227 | 0.215 | 0.212 | 0.013 | 0.660 | |

| n-3PUFA | ||||||

| C18:3n3 | 0.732 b | 0.983 a | 0.910 a | 0.041 | 0.001 | |

| C20:3n3 | 0.127 | 0.146 | 0.180 | 0.017 | 0.108 | |

| C20:5n3 | 0.131 | 0.148 | 0.147 | 0.014 | 0.624 | |

| Sum and Ratio 1 | ||||||

| PUFA | 40.319 c | 42.078 b | 43.687 a | 0.375 | <0.001 | |

| n-3PUFA | 1.122 b | 1.346 a | 1.368 a | 0.059 | 0.013 | |

| n-6PUFA | 39.197 c | 40.740 b | 42.311 a | 0.446 | <0.001 | |

| n-6/n-3 | 35.661 a | 32.853 b | 32.630 b | 0.638 | 0.005 | |

| U/S | 1.873 | 1.582 | 1.602 | 0.168 | 0.939 | |

| P/S | 1.118 | 1.103 | 1.135 | 0.069 | 0.330 | |

| liver | n-6PUFA | |||||

| C18:2n6t | 0.057 | 0.060 | 0.078 | 0.007 | 0.488 | |

| C18:2n6c | 40.943 b | 41.704 b | 43.758 a | 0.396 | <0.001 | |

| C18:3n6 | 0.028 | 0.030 | 0.032 | 0.002 | 0.400 | |

| C22:2n6 | 0.035 | 0.028 | 0.036 | 0.003 | 0.099 | |

| n-3PUFA | ||||||

| C18:3n3 | 0.859 | 1.053 | 1.212 | 0.112 | 0.105 | |

| C20:3n3 | 0.102 b | 0.118 ab | 0.137 a | 0.007 | 0.013 | |

| C20:5n3 | 0.015 b | 0.028 a | 0.033 a | 0.003 | 0.001 | |

| Sum and Ratio 1 | ||||||

| PUFA | 44.01 b | 44.95 b | 47.54 a | 0.387 | <0.001 | |

| n-3PUFA | 1.020 | 1.240 | 1.390 | 0.115 | 0.067 | |

| n-6PUFA | 42.99 b | 43.70 b | 46.10 a | 0.455 | <0.001 | |

| n-6/n-3 | 45.63 a | 35.99 b | 32.81 b | 2.126 | 0.001 | |

| U/S | 1.343 b | 1.447 b | 1.678 a | 0.055 | 0.001 | |

| P/S | 1.031 b | 1.100 b | 1.415 a | 0.076 | <0.001 | |

3.2. Lipid Metabolism Enzyme Activity

3.3. Lipid Metabolism Genes and PPARγ mRNA Expression

3.4. Antioxidant Activities and Immune Signaling Molecule Levels in Serum and Liver

3.5. Serum Metabolome

3.6. Liver Metabolome

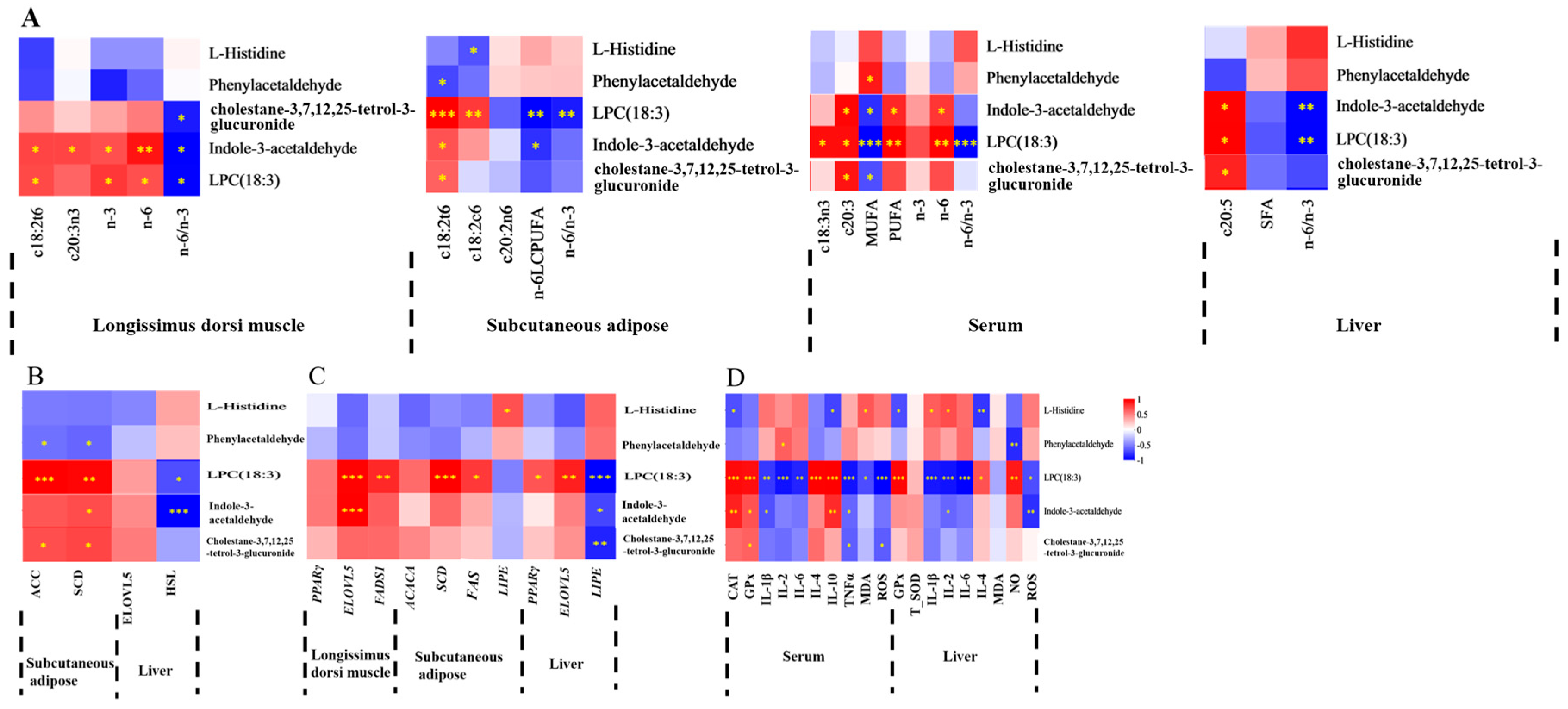

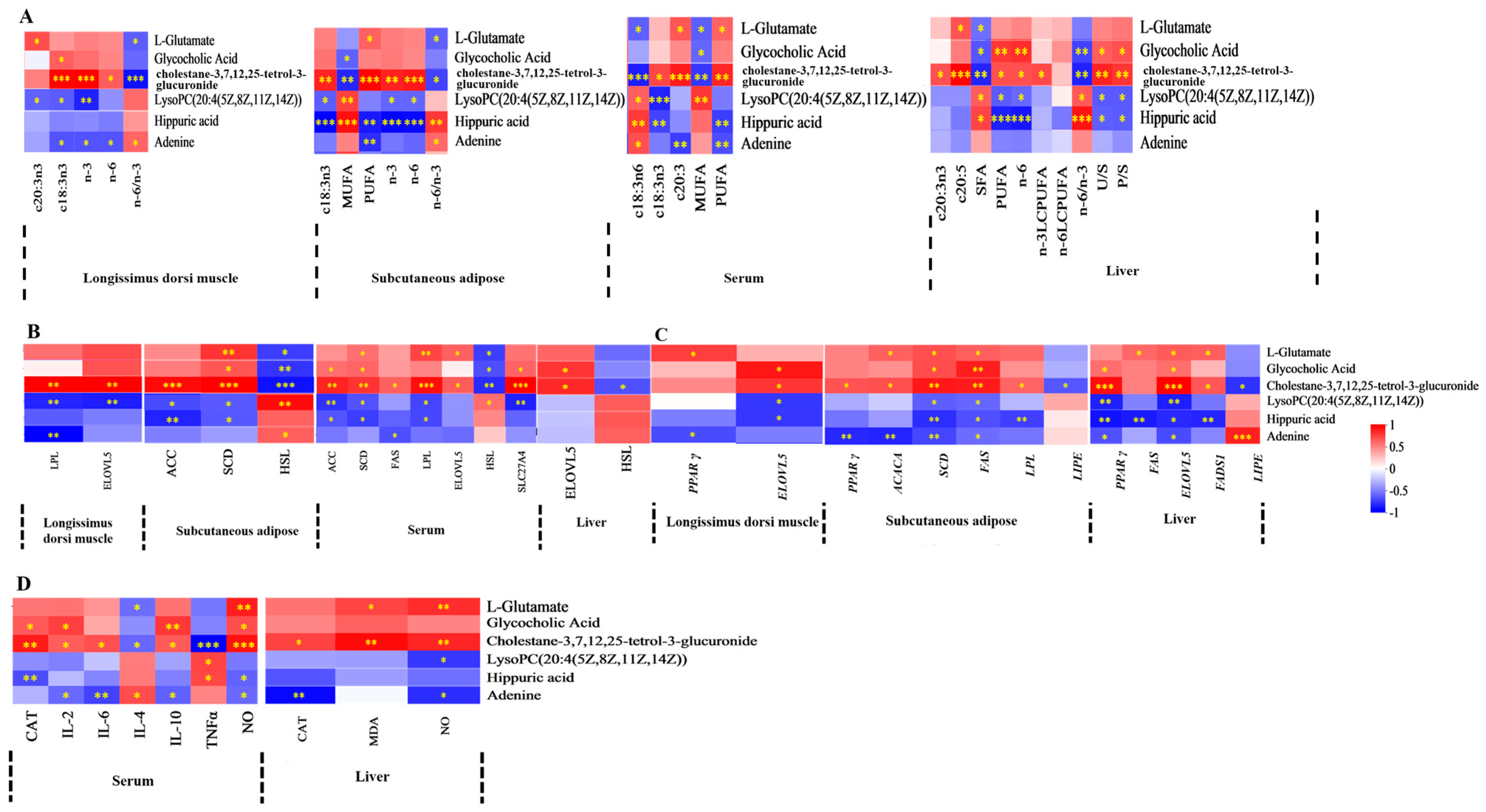

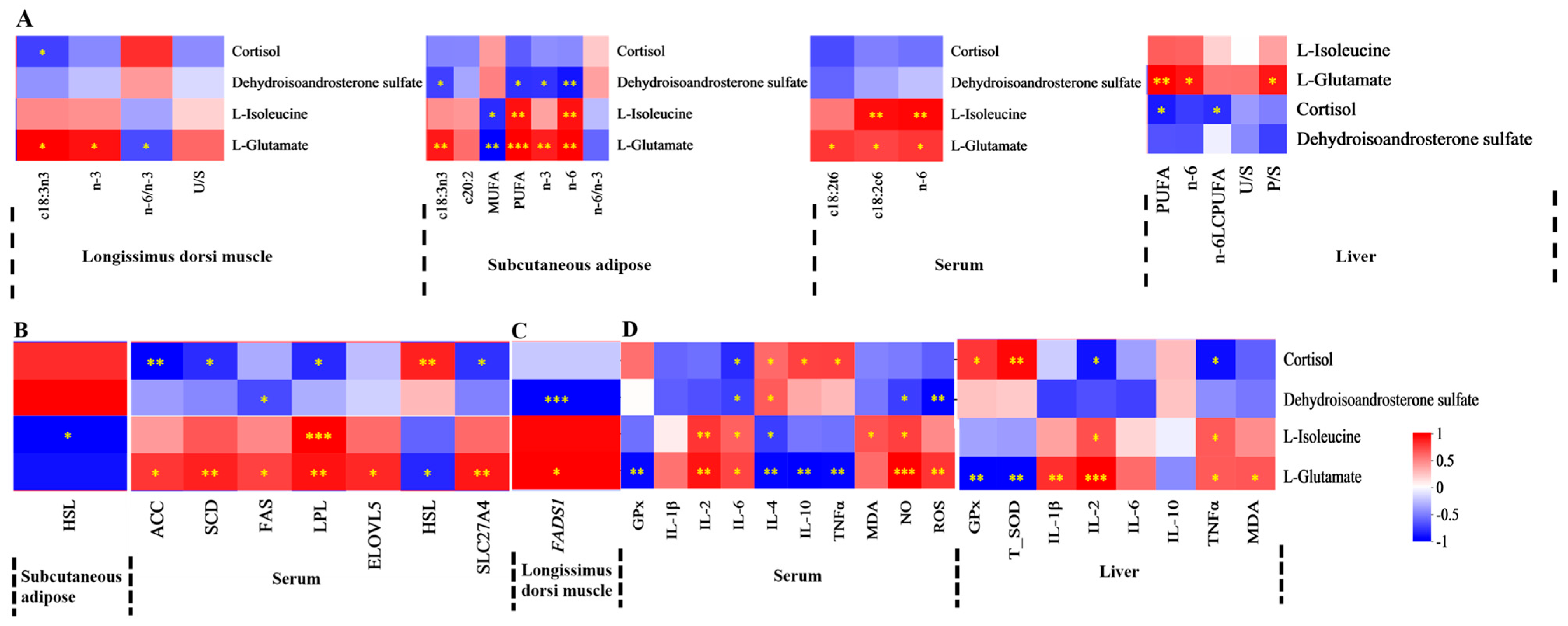

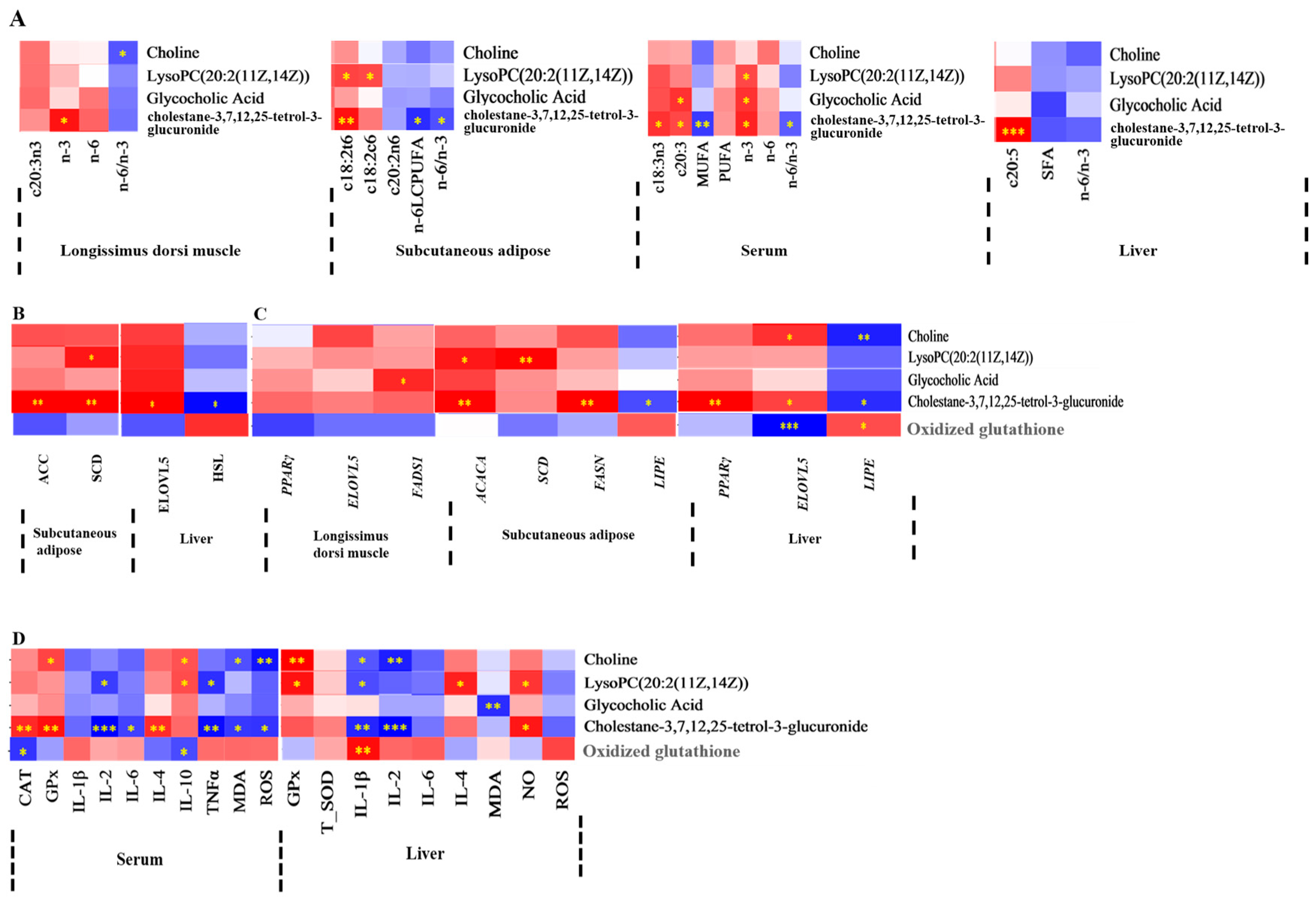

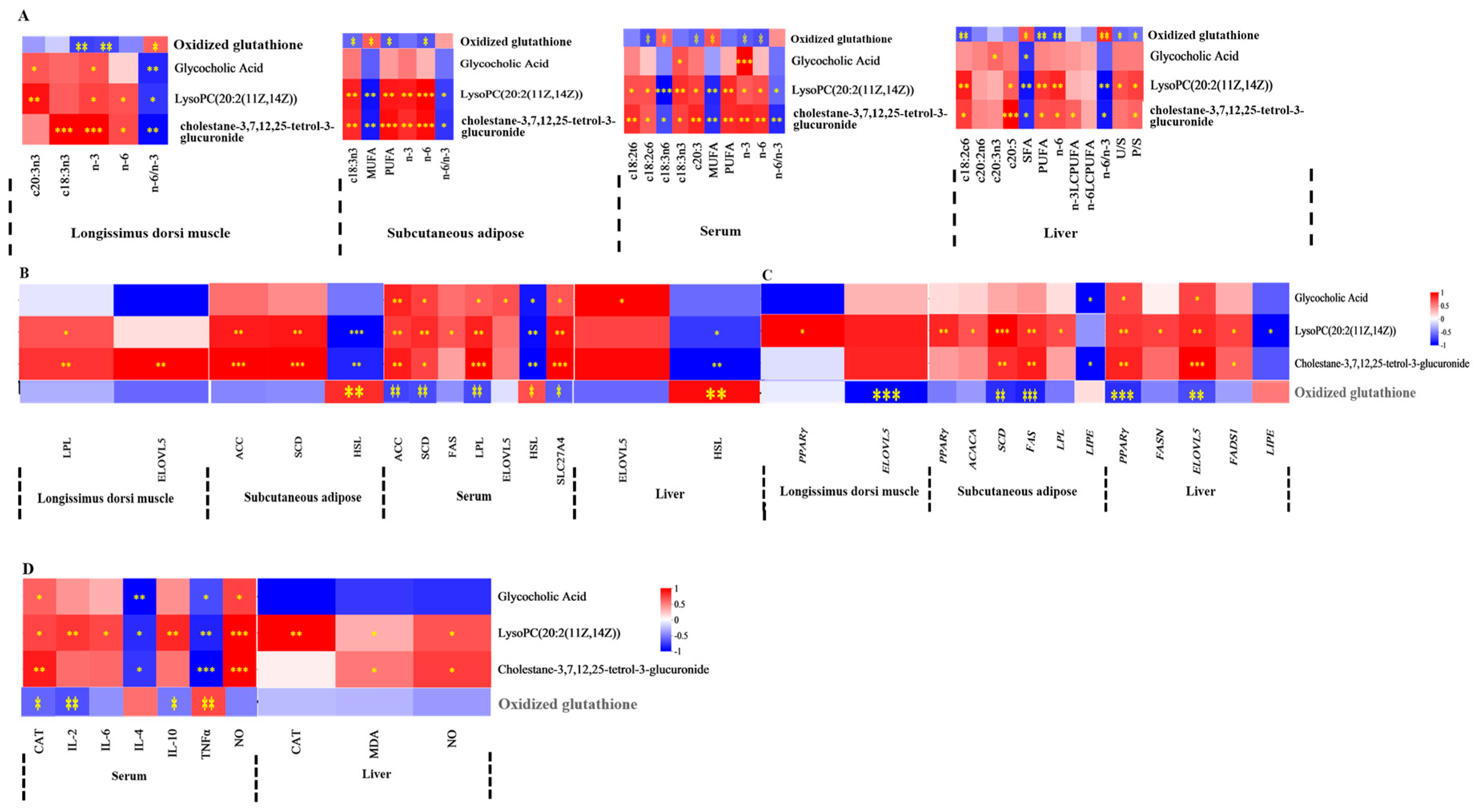

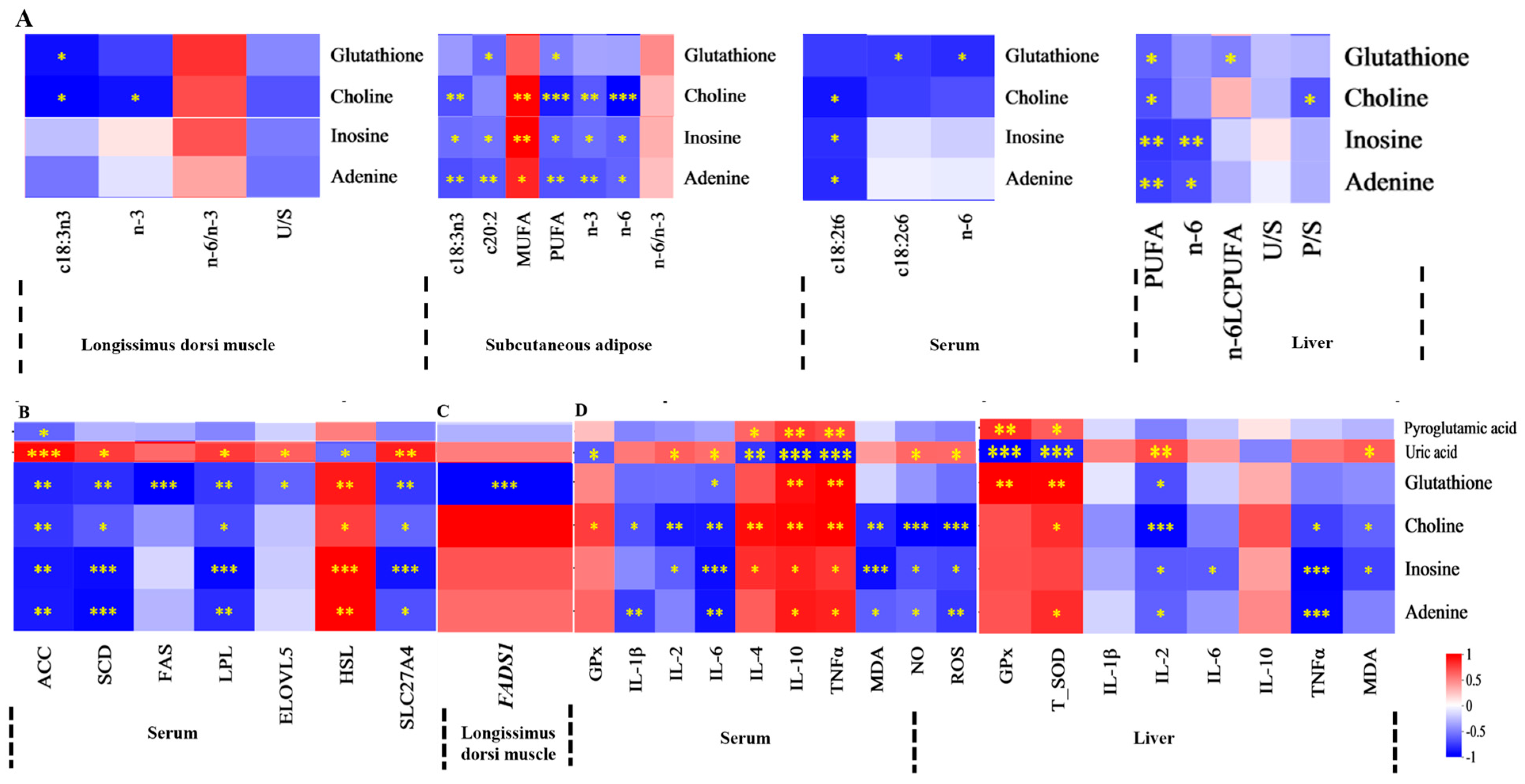

3.7. Correlations Between Serum or Liver Metabolites and FA, Lipid Metabolism Enzyme Activity, Lipid Metabolism Enzyme mRNA Expression, and Antioxidant Activities and Immune Signaling Molecule Levels

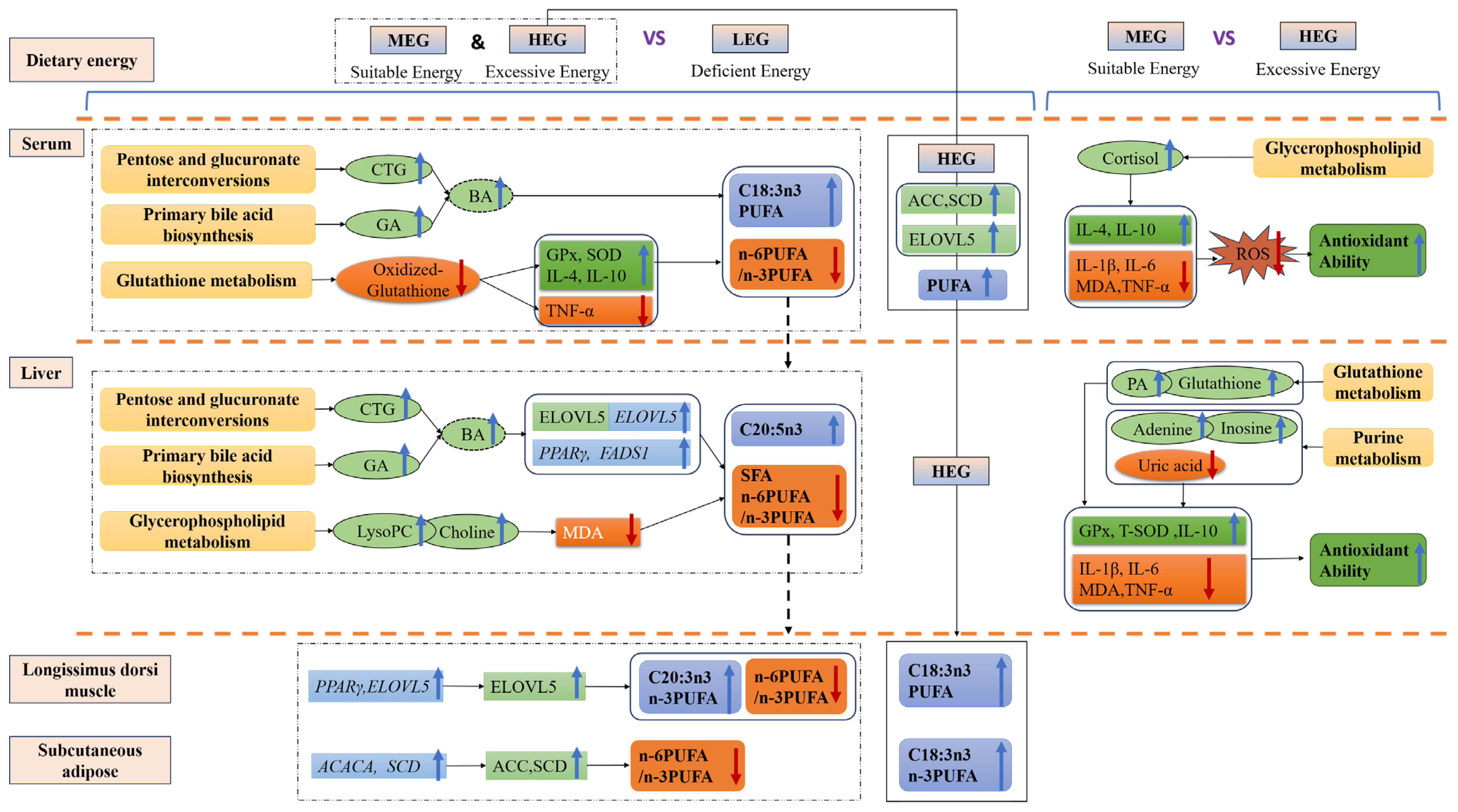

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects on Tissue Fatty Acid Profiles

4.2. Bile Acid Metabolism and FA Profile

4.3. Impaired Energy Homeostasis and Antioxidant Deficit in LEG

4.4. Metabolic Coordination and Enhanced Antioxidant Capacity in MEG

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LEG | low-energy group |

| MEG | medium-energy group |

| HEG | high-energy group |

| SFA | saturated fatty acid |

| MUFA | monounsaturated fatty acid |

| PUFA | polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| LCPUFA | long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| FAS | fatty acid synthase |

| ACC | acetyl-CoA carboxylase |

| LPL | lipoprotein lipase |

| HSL | hormone-sensitive lipase |

| SCD | stearoyl-coa desaturase |

| ELOVL | elongation of very long chain fatty acids protein |

| SLC27A4 | solute carrier family 27 member 4 |

| PPARγ | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ |

| ACACA | acetyl-coa carboxylase alpha |

| LIPE | hormone-sensitive lipase |

| FADS1 | fatty acid desaturase 1 |

| CAT | catalase |

| GPx | glutathione peroxidase |

| T-SOD | total superoxide dismutase |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| IL | interleukin |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

References

- Polidori, P.; Cavallucci, C.; Beghelli, D.; Vincenzetti, S. Physical and chemical characteristics of donkey meat from Martina Franca breed. Meat Sci. 2009, 82, 469–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.D.; Enser, M.; Fisher, A.V.; Nute, G.R.; Sheard, P.R.; Richardson, R.I.; Hughes, S.I.; Whittington, F.M. Fat deposition, fatty acid composition and meat quality: A review. Meat Sci. 2008, 78, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Wu, J.H. (n-3) fatty acids and cardiovascular health: Are effects of EPA and DHA shared or complementary? J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 614S–625S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumann, J.; Leichtle, A.; Thiery, J.; Fuhrmann, H. Fatty acid and peptide profiles in plasma membrane and membrane rafts of PUFA supplemented RAW264.7 macrophages. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, S.K.; Trépanier, M.O.; Bazinet, R.P. n-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids in animal models with neuroinflammation. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2013, 88, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, K.; Ma, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Peng, Q.; Hu, R.; Zou, H.; Bao, S.; Zhang, W.; Sun, B. High-energy diet improves growth performance, meat quality and gene expression related to intramuscular fat deposition in finishing yaks raised by barn feeding. Vet. Med. Sci. 2020, 6, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Bao, P.; Long, R.; Guo, X.; Ding, X.; Yan, P. The response of gene expression associated with lipid metabolism, fat deposition and fatty acid profile in the longissimus dorsi muscle of Gannan yaks to different energy levels of diets. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.H.; Jin, Y.H.; Do, S.H.; Hong, J.S.; Kim, B.O.; Han, T.H.; Kim, Y.Y. Effects of dietary energy and crude protein levels on growth performance, blood profiles, and carcass traits in growing-finishing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2019, 61, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattijssen, F.; Georgiadi, A.; Andasarie, T.; Szalowska, E.; Zota, A.; Krones-Herzig, A.; Heier, C.; Ratman, D.; De Bosscher, K.; Qi, L.; et al. Hypoxia-inducible lipid droplet-associated (HILPDA) is a novel peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) target involved in hepatic triglyceride secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 19279–19293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yuan, J.; Ma, J.; Ding, J.; Lin, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Sun, Y.; Wu, R.; Liu, C.; et al. BMP7 improves insulin signal transduction in the liver via inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 243, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chi, Y.; Yue, Y.X.; Zhao, Y.L.; Guo, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.W.; Shi, B.L.; Yan, S.M. Effects of dietary energy level on growth, fattening performance and slaughter performance of Broiler Donkeys. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 33, 2827–2835. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Du, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Y.L.; Guo, X.Y.; Guo, Y.M.; Zhang, Y.W.; Yan, S.M. Effects of dietary energy level on physicochemical properties and conventional nutrient content of Donkey meat. Feed. Ind. 2022, 43, 30–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Guo, X.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Shi, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, S. Cecal Microbial Diversity and Metabolome Reveal a Reduction in Growth Due to Oxidative Stress Caused by a Low-Energy Diet in Donkeys. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Fallon, J.V.; Busboom, J.R.; Nelson, M.L.; Gaskins, C.T. A direct method for fatty acid methyl ester synthesis: Application to wet meat tissues, oils, and feedstuffs. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 1511–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Martin, G.B.; Liu, S.L.; Shi, B.L.; Guo, X.Y.; Zhao, Y.L.; Yan, S.M. The mechanism through which dietary supplementation with heated linseed grain increases n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid concentration in subcutaneous adipose tissue of cashmere kids. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, research0034.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, H.; Cui, H.; Yu, J.; Hayat, K.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Ho, C.T. Characteristic flavor formation of thermally processed N-(1-deoxy-α-d-ribulos-1-yl)-glycine: Decisive role of additional amino acids and promotional effect of glyoxal. Food Chem. 2022, 371, 131137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, I.; Húth, B.; Füller, I.; Rózsa, L.; Holló, G.; Zsolnai, A. Effect of single nucleotide polymorphisms on intramuscular fat content in Hungarian Simmental cattle. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 1415–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, W.; Tang, X.; Huang, R.; Li, F.; Su, W.; Yin, Y.; Wen, C.; Liu, J. Comparison of the meat quality and fatty acid profile of muscles in finishing Xiangcun Black pigs fed varied dietary energy levels. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 11, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos-Filho, P.T.; Costa, H.H.A.; Vega, W.H.O.; Sousa, L.C.O.; Parente, M.O.M.; Landim, A.V. Effects of dietary energy content and source using by-products on carcass and meat quality traits of cull ewes. Animal 2021, 15, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, M.C.; Saadoun, A. An overview of the nutritional value of beef and lamb meat from South America. Meat Sci. 2014, 98, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, A.P.; Mooney, M.T.; Kerry, J.P.; Troy, D.J. Producing tender and flavoursome beef with enhanced nutritional characteristics. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2001, 60, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; Zeng, X.; Yin, P.; Zhu, J.; Chen, W.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 394, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visioli, F.; Poli, A. Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Risk. Evidence, Lack of Evidence, and Diligence. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Khalili, H.; Konijeti, G.G.; Higuchi, L.M.; de Silva, P.; Fuchs, C.S.; Willett, W.C.; Richter, J.M.; Chan, A.T. Long-term intake of dietary fat and risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut 2014, 63, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corazzin, M.; Bovolenta, S.; Saccà, E.; Bianchi, G.; Piasentier, E. Effect of linseed addition on the expression of some lipid metabolism genes in the adipose tissue of young Italian Simmental and Holstein bulls. J. Anim Sci. 2013, 91, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownsey, R.W.; Boone, A.N.; Elliott, J.E.; Kulpa, J.E.; Lee, W.M. Regulation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006, 34, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.L.; Humphrey, D.C.; Karriker, L.A.; Brown, J.T.; Skoland, K.J.; Greiner, L.L. The effects of dietary essential fatty acid ratios and energy level on growth performance, lipid metabolism, and inflammation in grow-finish pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, skad151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graugnard, D.E.; Piantoni, P.; Bionaz, M.; Berger, L.L.; Faulkner, D.B.; Loor, J.J. Adipogenic and energy metabolism gene networks in longissimus lumborum during rapid post-weaning growth in Angus and Angus x Simmental cattle fed high-starch or low-starch diets. BMC Genom. 2009, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Kothapalli, K.S.; Brenna, J.T. Desaturase and elongase-limiting endogenous long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2016, 19, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Mou, H.; He, Y.; Zhang, D.; Pan, X.; Zhou, L.; Shen, Y.; E, G. Effects of key rumen bacteria and microbial metabolites on fatty acid deposition in goat muscle. Animals 2024, 14, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, H.; Cheng, Y.; Yu, H.; Feng, N.; Huang, R.; Liu, S.; et al. High-protein diet prevents fat mass increase after dieting by counteracting Lactobacillus-enhanced lipid absorption. Nat. Metab. 2022, 4, 1713–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larabi, A.B.; Masson, H.L.P.; Bäumler, A.J. Bile acids as modulators of gut microbiota composition and function. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2172671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, D.; Luo, J.; He, Q.; Shi, H.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, H.; Chen, Z.; Yi, Y.; Loor, J.J. SCD1 alters long-chain fatty acid (LCFA) Composition and its expression is directly regulated by SREBP-1 and PPARγ 1 in dairy goat mammary cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017, 232, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Qi, S.; Si, D.; Man, Z.; Deng, S.; Liu, G.; et al. Metabolic differences in MSTN and FGF5 dual-gene edited sheep muscle cells during myogenesis. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Guo, L.; Cao, Y.; Yin, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, J.; Li, J.; Huang, X.; Li, K.; et al. High-concentrate diet decreases lamb fatty acid contents by regulating bile acid composition. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monk, J.M.; Hou, T.Y.; Turk, H.F.; McMurray, D.N.; Chapkin, R.S. n3 PUFAs reduce mouse CD4+ T-cell ex vivo polarization into Th17 cells. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, E.J.; Lee, K.E.; Nho, Y.H.; Ryu, J.; Kim, S.Y.; Yoo, J.K.; Kang, S.; Seo, S.W. Lipid extract derived from newly isolated Rhodotorula toruloides LAB-07 for cosmetic applications. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 2009–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.B.; Karoly, E.D.; Jones, J.C.; Ward, W.O.; Vallanat, B.D.; Andrews, D.L.; Schladweiler, M.C.; Snow, S.J.; Bass, V.L.; Richards, J.E.; et al. Inhaled ozone (O3)-induces changes in serum metabolomic and liver transcriptomic profiles in rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2015, 286, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Xie, S.; Chi, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, X.; Xia, D.; Ke, Y.; et al. Bile Acids Control Inflammation and Metabolic Disorder through Inhibition of NLRP3 Inflammasome. Immunity 2016, 45, 802–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; An, Y.; Xue, H.; Wang, J.; Xia, F.; Chen, X.; Cao, Y. Microbiome-metabolome responses of Fuzhuan brick tea crude polysaccharides with immune-protective benefit in cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressive mice. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fu, W.W.; Wu, R.T.; Song, Y.H.; Wu, W.Y.; Yin, S.H.; Li, W.J.; Xie, M.Y. Protective effect of Ganoderma atrum polysaccharides in acute lung injury rats and its metabolomics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 142, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebowale, T.; Shunshun, J.; Yao, K. The effect of dietary high energy density and carbohydrate energy ratio on digestive enzymes activity, nutrient digestibility, amino acid utilization and intestinal morphology of weaned piglets. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 103, 1492–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinian, S.A.; Hasanzadeh, F. Impact of high dietary energy on obesity and oxidative stress in domestic pigeons. Vet. Med. Sci. 2021, 7, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.L.; Ko, C.H. The role of oxidative stress in vitiligo: An update on its pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Cells 2023, 12, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, P.S.; Yoon, Y.; Robotham, J.L.; Anders, M.W.; Sheu, S.S. Calcium, ATP, and ROS: A mitochondrial love-hate triangle. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2004, 287, C817–C833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, K.; Das, J.; Pal, P.B.; Sil, P.C. Oxidative stress: The mitochondria-dependent and mitochondria-independent pathways of apoptosis. Arch. Toxicol. 2013, 87, 1157–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, J.; Tulassay, Z.; Lengyel, G.; Szombath, D.; Székács, B.; Adler, I.; Marczell, I.; Nagy-Répas, P.; Dinya, E.; Rácz, K.; et al. Increased total scavenger capacity in rats fed corticosterone and cortisol on lipid-rich diet. Acta Physiol. Hung. 2013, 100, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geenen, S.; Yates, J.W.; Kenna, J.G.; Bois, F.Y.; Wilson, I.D.; Westerhoff, H.V. Multiscale modelling approach combining a kinetic model of glutathione metabolism with PBPK models of paracetamol and the potential glutathione-depletion biomarkers ophthalmic acid and 5-oxoproline in humans and rats. Integr. Biol. 2013, 5, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, Y.; Gatellier, P.; Renerre, M. Lipid and protein oxidation in vitro, and antioxidant potential in meat from Charolais cows finished on pasture or mixed diet. Meat Sci. 2004, 66, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calpena, E.; Casado, M.; Martínez-Rubio, D.; Nascimento, A.; Colomer, J.; Gargallo, E.; García-Cazorla, A.; Palau, F.; Artuch, R.; Espinós, C. 5-Oxoprolinuria in Heterozygous Patients for 5-Oxoprolinase (OPLAH) Missense Changes. JIMD Rep. 2013, 7, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Vance, D.E. Phosphatidylcholine and choline homeostasis. J. Lipid Res. 2008, 49, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breksa, A.P.; Garrow, T.A. Recombinant human liver betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase: Identification of three cysteine residues critical for zinc binding. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 13991–13998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.Y.; Lin, C.H.; Lin, J.T.; Cheng, Y.F.; Chen, H.M.; Kao, S.H. Adenine causes cell cycle arrest and autophagy of chronic myelogenous leukemia K562 cells via AMP-activated protein kinase signaling. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 5575–5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinon, F.; Pétrilli, V.; Mayor, A.; Tardivel, A.; Tschopp, J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature 2006, 440, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, T.T.; Forni, M.F.; Correa-Costa, M.; Ramos, R.N.; Barbuto, J.A.; Branco, P.; Castoldi, A.; Hiyane, M.I.; Davanso, M.R.; Latz, E.; et al. Soluble Uric Acid Activates the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 39884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, L.F.; Burkhard, R.; Pett, N.; Cooke, N.C.A.; Brown, K.; Ramay, H.; Paik, S.; Stagg, J.; Groves, R.A.; Gallo, M.; et al. Microbiome-derived inosine modulates response to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Science 2020, 369, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Zhang, C.; Ren, G.; Chang, K.; He, G.; Du, Z.; Le, Y.; et al. Xie Zhuo Tiao Zhi formula modulates intestinal microbiota and liver purine metabolism to suppress hepatic steatosis and pyroptosis in NAFLD therapy. Phytomedicine 2023, 121, 155111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, T.I.R.C.; Chen, Y.; Furusho-Garcia, I.F.; Perez, J.R.O.; Hopkins, D.L. Manipulation of omega-3 PUFAs in lamb: Phenotypic and genotypic views. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2015, 14, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, T.W.; Zhang, Y.N.; Zhang, M.; Zhai, M.Q.; Wang, W.H.; Wang, C.L.; Duan, Y.; Jin, Y. Exercise influences fatty acids in the longissimus dorsi muscle of Sunit lambs and improves dressing percentage by affecting digestion, absorption, and lipid metabolism. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2024, 16, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yu, S.; Guo, J.; Wang, J.; Mei, C.; Raza, S.H.A.; Cheng, G.; Zan, L. Comprehensive analysis of transcriptome and metabolome reveals regulatory mechanism of intramuscular fat content in beef cattle. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 2911–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

represents pathways,

represents pathways,  represents metabolites,

represents metabolites,  represents lipid metabolism enzyme activity,

represents lipid metabolism enzyme activity,  represents lipid metabolism enzyme mRNA expression,

represents lipid metabolism enzyme mRNA expression,  represents an increase, and

represents an increase, and  represents a decrease.

represents a decrease.

represents pathways,

represents pathways,  represents metabolites,

represents metabolites,  represents lipid metabolism enzyme activity,

represents lipid metabolism enzyme activity,  represents lipid metabolism enzyme mRNA expression,

represents lipid metabolism enzyme mRNA expression,  represents an increase, and

represents an increase, and  represents a decrease.

represents a decrease.

| Items | LEG | MEG | HEG | SEM | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longissimus dorsi muscle | |||||

| ACC (U/L) | 27.17 | 28.30 | 28.43 | 0.439 | 0.108 |

| LPL (U/L) | 493.86 b | 534.35 ab | 563.33 a | 14.2 | 0.009 |

| HSL (U/L) | 1063.33 | 1021.67 | 1038.73 | 28.551 | 0.592 |

| FAS (U/mL) | 1581.67 | 1719.17 | 1733.25 | 66.687 | 0.230 |

| SCD (U/L) | 98.83 | 101.34 | 104.33 | 3.326 | 0.514 |

| ELOVL2 (U/L) | 81.05 | 81.03 | 81.34 | 1.258 | 0.981 |

| ELOVL5 (U/L) | 110.27 b | 121.43 a | 127.16 a | 3.636 | 0.011 |

| SLC27A4 (U/L) | 84.77 | 92.83 | 85.61 | 3.316 | 0.193 |

| Subcutaneous adipose | |||||

| ACC (U/L) | 27.71 b | 32.37 a | 32.24 a | 0.586 | <0.001 |

| LPL (U/L) | 550.65 | 568.80 | 585.43 | 9.563 | 0.056 |

| HSL (U/L) | 1099.44 a | 1074.38 a | 958.11 b | 25.644 | 0.002 |

| FAS (U/mL) | 1696.25 | 1897.64 | 1901.56 | 65.508 | 0.061 |

| SCD (U/L) | 90.22 b | 97.74 a | 97.39 a | 0.778 | <0.001 |

| ELOVL2 (U/L) | 72.19 | 72.34 | 72.50 | 1.35 | 0.987 |

| ELOVL5 (U/L) | 62.16 | 61.73 | 61.36 | 0.343 | 0.102 |

| SLC27A4 (U/L) | 83.64 | 78.23 | 80.66 | 2.173 | 0.234 |

| Serum | |||||

| ACC (U/L) | 38.07 b | 39.88 b | 50.82 a | 1.823 | 0.002 |

| LPL (U/L) | 470.22 b | 510.22 b | 603.26 a | 16.256 | <0.001 |

| HSL (U/L) | 1427.22 a | 1385.57 a | 1259.86 b | 27.914 | 0.001 |

| FAS (U/mL) | 1852.78 b | 1926.11 b | 2161.06 a | 59.193 | 0.004 |

| SCD (U/L) | 132.28 b | 138.62 b | 176.98 a | 5.022 | <0.001 |

| ELOVL2 (U/L) | 94.05 | 96.54 | 100.55 | 3.673 | 0.464 |

| ELOVL5 (U/L) | 65.15 b | 67.85 b | 78.48 a | 1.888 | 0.005 |

| SLC27A4 (U/L) | 52.23 b | 54.39 b | 68.96 a | 1.518 | <0.001 |

| Liver | |||||

| ACC (U/L) | 31.63 | 31.99 | 33.27 | 0.673 | 0.218 |

| LPL (U/L) | 558.80 | 616.96 | 585.16 | 19.195 | 0.125 |

| HSL (U/L) | 931.96 a | 840.60 b | 849.520 b | 25.223 | 0.034 |

| FAS (U/mL) | 1856.70 | 1896.90 | 2102.70 | 78.669 | 0.083 |

| SCD (U/L) | 101.72 | 104.06 | 106.47 | 3.578 | 0.649 |

| ELOVL2 (U/L) | 89.30 | 91.00 | 89.80 | 1.865 | 0.805 |

| ELOVL5 (U/L) | 50.63 b | 59.87 a | 65.46 a | 2.081 | <0.001 |

| SLC27A4 (U/L) | 83.95 | 85.36 | 88.04 | 1.786 | 0.280 |

| Items | LEG | MEG | HEG | SEM | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longissimus dorsi muscle | |||||

| PPARγ | 1.00 b | 1.16 a | 1.23 a | 0.043 | 0.004 |

| ACACA | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.016 | 0.183 |

| LPL | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.36 | 0.115 | 0.103 |

| LIPE | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.07 | 0.297 |

| FAS | 1.00 | 1.14 | 1.04 | 0.076 | 0.418 |

| SCD | 1.00 | 1.06 | 1.21 | 0.079 | 0.172 |

| ELOVL2 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.18 | 0.063 | 0.111 |

| ELOVL5 | 1.00 b | 1.14 a | 1.14 a | 0.037 | 0.007 |

| FADS1 | 1.00 b | 1.30 a | 0.86 b | 0.059 | <0.001 |

| Subcutaneous adipose | |||||

| PPARγ | 1.00 b | 1.14 ab | 1.33 a | 0.077 | 0.049 |

| ACACA | 1.00 b | 1.28 a | 1.27 a | 0.066 | 0.011 |

| LPL | 1.00 b | 1.24 b | 1.55 a | 0.086 | 0.005 |

| LIPE | 1.00 a | 0.97 b | 0.85 b | 0.038 | 0.028 |

| FAS | 1.00 b | 1.26 a | 1.31 a | 0.052 | 0.002 |

| SCD | 1.00 b | 1.62 a | 1.60 a | 0.174 | 0.002 |

| ELOVL2 | 1.00 | 1.12 | 1.17 | 0.067 | 0.199 |

| ELOVL5 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.073 | 0.569 |

| FADS1 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 1.03 | 0.059 | 0.605 |

| Liver | |||||

| PPARγ | 1.00 b | 1.26 a | 1.33 a | 0.082 | 0.002 |

| ACACA | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.08 | 0.116 | 0.558 |

| LPL | 1.00 | 1.19 | 1.06 | 0.149 | 0.174 |

| LIPE | 1.00 a | 0.68 b | 0.83 b | 0.056 | 0.002 |

| FAS | 1.00 b | 1.09 ab | 1.16 a | 0.042 | 0.013 |

| SCD | 1.00 | 1.03 | 1.13 | 0.064 | 0.221 |

| ELOVL2 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 1.04 | 0.069 | 0.553 |

| ELOVL5 | 1.00 b | 1.09 a | 1.12 a | 0.025 | 0.002 |

| FADS1 | 1.00 b | 1.09 ab | 1.25 a | 0.051 | 0.017 |

| Item | LEG | MEG | HEG | SEM | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant enzyme activities, U/mL | |||||

| CAT | 8.26 b | 11.89 a | 11.61 a | 0.341 | 0.001 |

| GPx | 433.33 b | 500.67 a | 443.43 b | 13.342 | 0.004 |

| T-SOD | 136.76 a | 122.51 b | 119.13 b | 2.148 | 0.001 |

| Immune signaling molecule, pg/mL | |||||

| IL-1β | 26.17 a | 21.14 b | 25.35 a | 0.789 | <0.001 |

| IL-2 | 268.73 b | 233.55 c | 290.02 a | 4.675 | <0.001 |

| IL-6 | 155.97 b | 132.95 c | 168.65 a | 2.228 | <0.001 |

| IL-4 | 6.53 b | 7.80 a | 5.76 c | 0.147 | <0.001 |

| IL-10 | 8.30 c | 12.13 a | 9.42 b | 0.230 | <0.001 |

| TNF-α | 70.48 a | 46.67 b | 35.57 c | 1.767 | <0.001 |

| MDA concentration, nmol/mL | 2.16 a | 1.92 b | 2.16 a | 0.045 | 0.003 |

| NO concentration, μmol/L | 40.20 b | 39.65 b | 53.46 a | 1.601 | <0.001 |

| ROS (IU/mL) | 131.00 a | 119.32 b | 129.84 a | 1.104 | <0.001 |

| Item | LEG | MEG | HEG | SEM | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant enzyme activities, U/mgprot. | |||||

| CAT | 53.66 b | 57.93 ab | 68.29 a | 3.609 | 0.026 |

| GPx | 82.60 b | 95.21 a | 84.00 b | 2.527 | 0.004 |

| T-SOD | 89.52 b | 90.14 a | 83.48 b | 1.721 | 0.023 |

| Immune signaling molecule, pg/mgprot. | |||||

| IL-1β | 3.22 a | 2.51 b | 3.25 a | 0.188 | 0.009 |

| IL-2 | 21.46 a | 17.47 b | 20.86 a | 0.252 | <0.001 |

| IL-6 | 14.34 a | 12.50 b | 15.22 a | 0.365 | 0.002 |

| IL-4 | 0.78 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 0.046 | 0.058 |

| IL-10 | 2.15 b | 2.50 a | 2.28 b | 0.073 | 0.010 |

| TNF-α | 2.04 ab | 1.89 b | 2.27 a | 0.093 | 0.019 |

| MDA concentration, nmol/mgprot. | 1.86 b | 1.59 c | 2.13 a | 0.080 | 0.001 |

| NO concentration, μmol/gprot. | 6.64 b | 7.60 a | 7.84 a | 0.178 | <0.001 |

| ROS (IU/mgprot.) | 281.35 | 252.61 | 274.77 | 9.075 | 0.087 |

| Metabolic Pathways | p-Value | Up-Metabolites | Down-Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEG vs. LEG | |||

| Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | 0.109 | Cholestane-3,7,12,25-tetrol-3-glucuronide | |

| HEG vs. LEG | |||

| D-Glutamine and D-glutamate metabolism | 0.001 | L-Glutamate | |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 0.015 | LPC(18:3) | LysoPC(20:4(5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z)) PC(18:2(9Z,12Z)/20:4(5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z)) |

| Phenylalanine metabolism | 0.017 | Hippuric acid Benzoic acid | |

| Purine metabolism | 0.039 | Hypoxanthine | Adenine |

| Taurine and hypotaurine metabolism | 0.077 | L-Glutamate | |

| Arginine biosynthesis | 0.087 | L-Glutamate | |

| Alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism | 0.104 | L-Glutamate | |

| Glutathione metabolism | 0.136 | L-Glutamate | |

| Primary bile acid biosynthesis | 0.159 | Glycocholic Acid | |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis | 0.175 | L-Glutamate | |

| Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | 0.178 | L-Glutamate | |

| Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | 0.178 | Cholestane-3,7,12,25-tetrol-3-glucuronide | |

| Tryptophan metabolism | 0.181 | Indole-3-acetaldehyde | |

| Arginine and proline metabolism | 0.225 | L-Glutamate | |

| MEG vs. HEG | |||

| D-Glutamine and D-glutamate metabolism | 0.002 | L-Glutamate | |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis | 0.031 | L-Isoleucine L-Glutamate | |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 0.100 | PC(18:2(9Z,12Z)/20:4(5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z)) | |

| Steroid hormone biosynthesis | 0.016 | Cortisol Dehydroisoandrosterone sulfate |

| Metabolic Pathways | p-Value | Up-Metabolites | Down-Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEG vs. LEG | |||

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 0.000 | Choline, LysoPC(20:2(11Z,14Z)) | PS(18:0/20:4(8Z,11Z,14Z,17Z)) PS(18:0/22:5(7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z,19Z)) PC(15:0/18:2(9Z,12Z)) |

| Glutathione metabolism | 0.102 | Oxidized glutathione | |

| Primary bile acid biosynthesis | 0.121 | Glycocholic Acid | |

| Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | 0.137 | Cholestane-3,7,12,25-tetrol-3-glucuronide 6-Hydroxy-5-methoxyindole glucuronide | Octanoylglucuronide |

| Purine metabolism | 0.193 | Inosine | |

| HEG vs. LEG | |||

| Purine metabolism | 0.000 | Xanthine, Uric acid | Guanosine, Inosine, Adenine, ADP |

| Glutathione metabolism | 0.001 | Glutathione, Gamma-Glu-Cys Pyroglutamic acid Oxidized glutathione | |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 0.003 | LysoPC(20:0), LysoPC(18:0) PC(22:5(4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z)/P-18:0) LPC(18:1), LysoPC(20:2(11Z,14Z)) LysoPC(P-18:0), LysoPC(20:1(11Z)) LPC(18:3) | Dimethylethanolamine PS(18:0/20:4(8Z,11Z,14Z,17Z)) PS(18:0/22:5(7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z,19Z)) PC(16:0/16:0), PC(15:0/18:2(9Z,12Z)) |

| Tyrosine metabolism | 0.138 | Phenol, L-Tyrosine | |

| Primary bile acid biosynthesis | 0.332 | Glycocholic Acid | |

| Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | 0.350 | Lithocholate 3-O-glucuronide Cholestane-3,7,12,25-tetrol-3-glucuronide | Octanoylglucuronide |

| MEG vs. HEG | |||

| Purine metabolism | 0.000 | Guanosine, Inosine Adenosine diphosphate ribose Adenylosuccinate, Adenine, ADP | Xanthine Uric acid |

| Glutathione metabolism | 0.007 | Glutathione, Gamma-Glu-Cys Pyroglutamic acid | |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 0.014 | Dimethylethanolamine, Choline | LysoPC(20:0), LPC(18:1) LysoPC(P-18:0), LPC(18:3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Shi, B.; Zhang, J.; Meng, F.; Hui, F.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, X.; Yan, S. Integration of Serum and Liver Metabolomics with Antioxidant Biomarkers Elucidates Dietary Energy Modulation of the Fatty Acid Profile in Donkey Meat. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010140

Li L, Zhao Y, Guo Y, Shi B, Zhang J, Meng F, Hui F, Zhang Q, Guo X, Yan S. Integration of Serum and Liver Metabolomics with Antioxidant Biomarkers Elucidates Dietary Energy Modulation of the Fatty Acid Profile in Donkey Meat. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010140

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Li, Yanli Zhao, Yongmei Guo, Binlin Shi, Jing Zhang, Fanzhu Meng, Fang Hui, Qingyue Zhang, Xiaoyu Guo, and Sumei Yan. 2026. "Integration of Serum and Liver Metabolomics with Antioxidant Biomarkers Elucidates Dietary Energy Modulation of the Fatty Acid Profile in Donkey Meat" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010140

APA StyleLi, L., Zhao, Y., Guo, Y., Shi, B., Zhang, J., Meng, F., Hui, F., Zhang, Q., Guo, X., & Yan, S. (2026). Integration of Serum and Liver Metabolomics with Antioxidant Biomarkers Elucidates Dietary Energy Modulation of the Fatty Acid Profile in Donkey Meat. Antioxidants, 15(1), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010140