Acute Impact of Polyphenol-Rich vs. Carbohydrate-Rich Foods and Beverages on Exercise-Induced ROS and FRAP in Healthy Sedentary Female Adults—A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

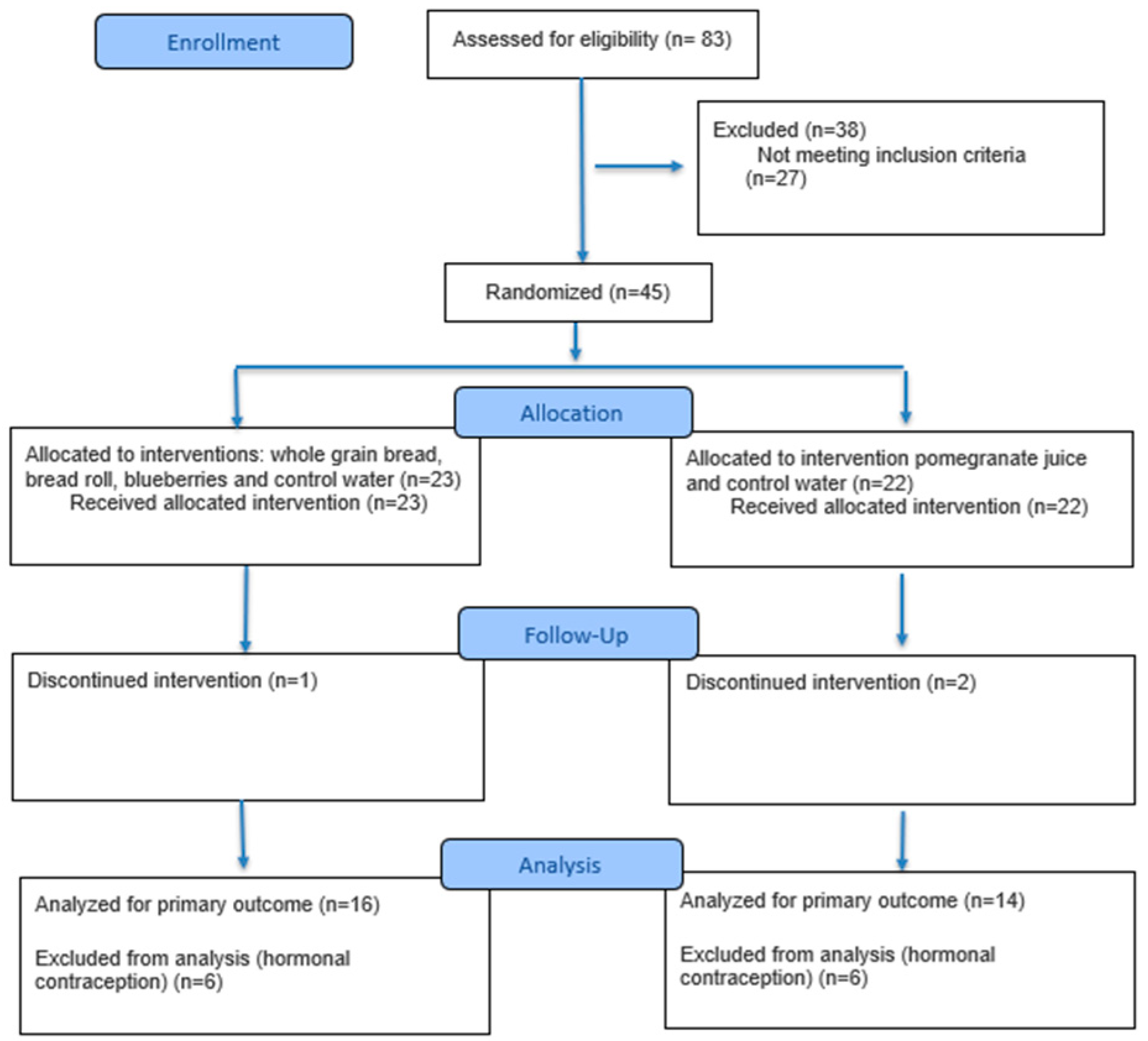

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Intervention Procedures and Sample Collection

2.4. Dietary Intervention and Blinding

2.5. Resistance-Circuit Training Protocol (HIIT)

2.6. Laboratory Measurements

2.6.1. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

2.6.2. Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP)

2.6.3. Polyphenol Detection of Intervention Foods and Beverages

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

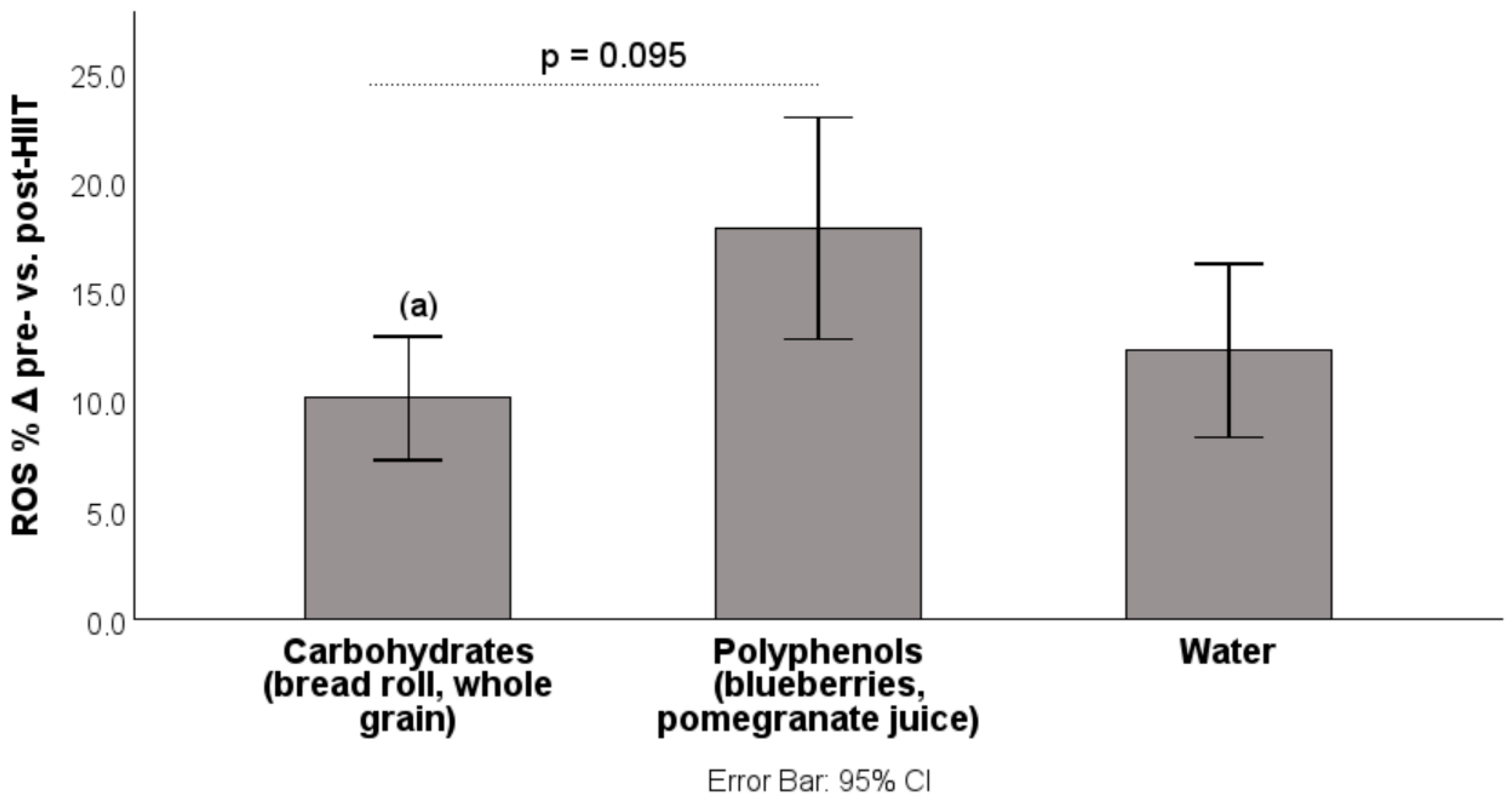

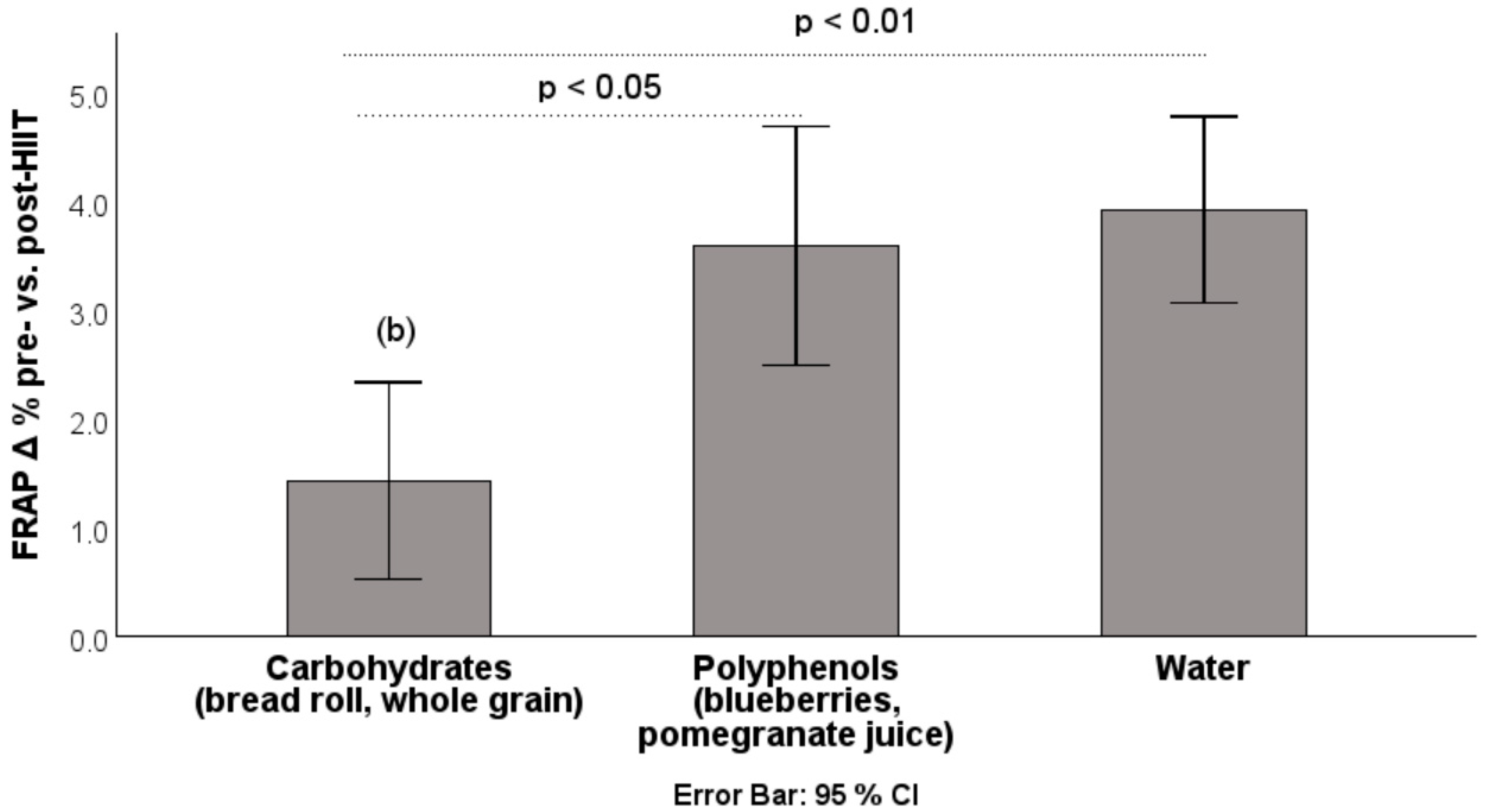

3.1. Results: Changes from Pre-HIIT to Post-HIIT

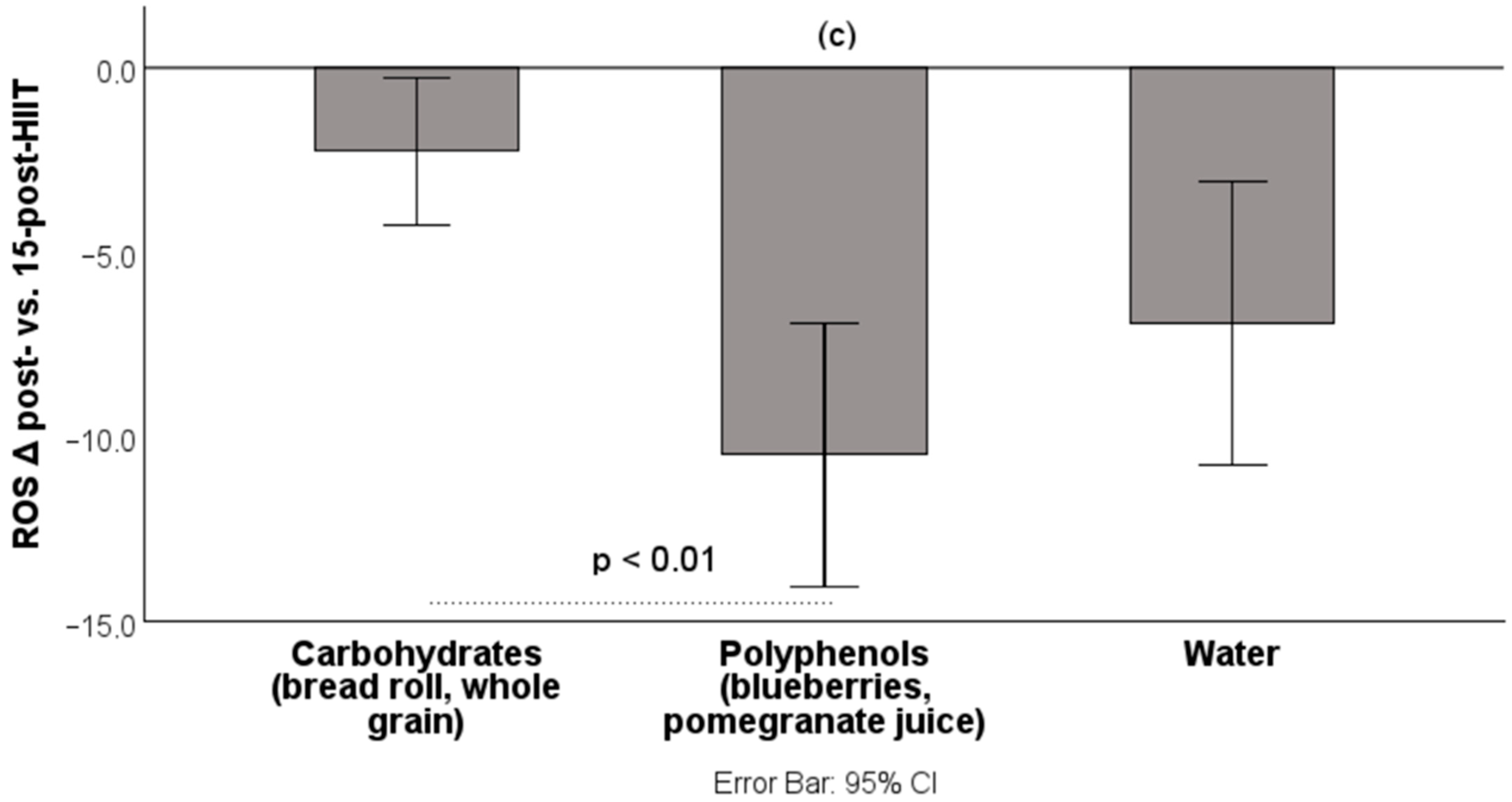

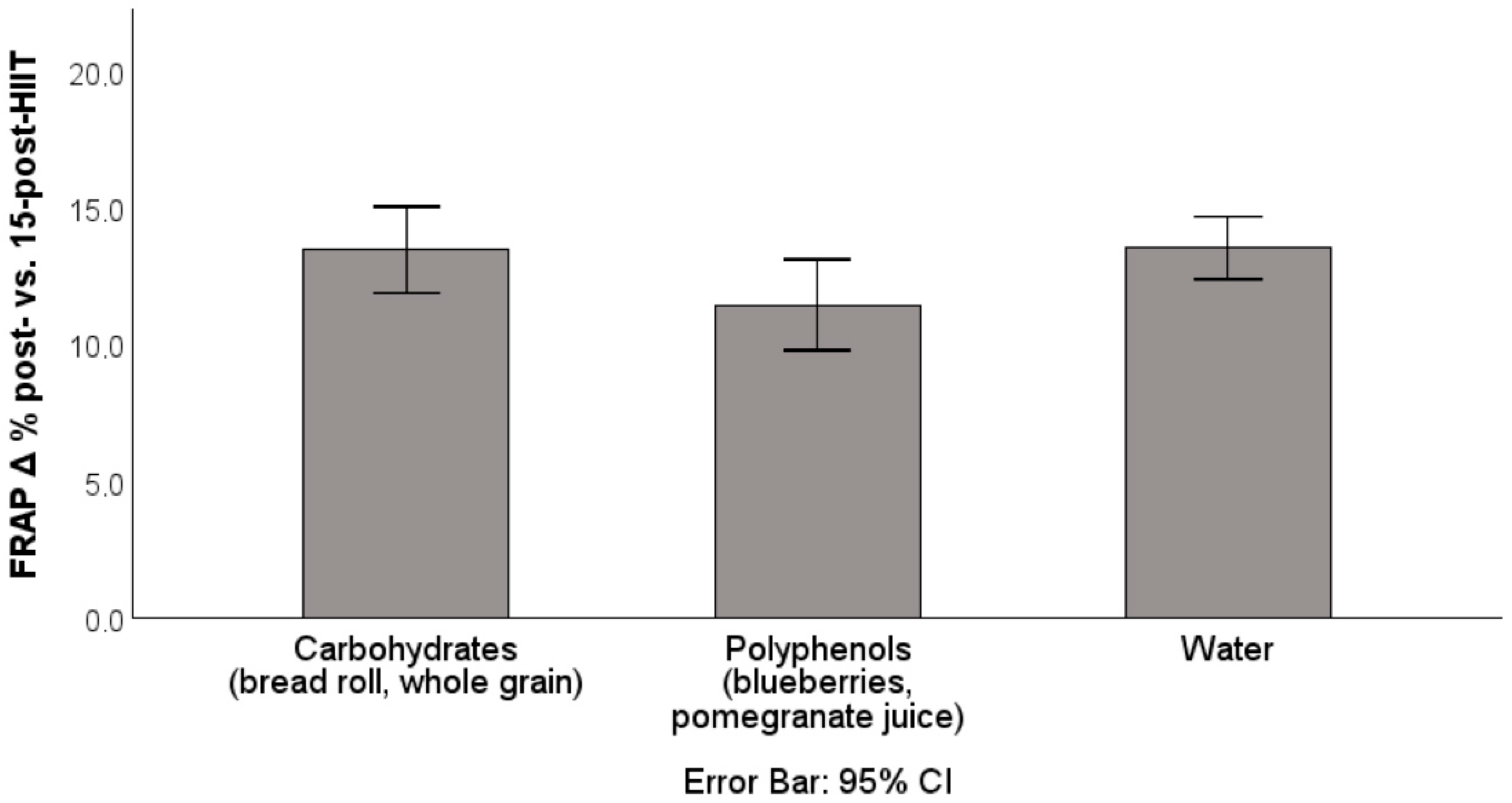

3.2. Results: Recovery Phase (Δ Post-HIIT → 15 min Post-HIIT (%-Change))

3.3. BORG Scale Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Recommendations for Athletes

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Rationale for Selecting the Nutritional Interventions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| FRAP | Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma |

| HIIT | High-Intensity Interval Training |

References

- Gomez-Cabrera, M.C.; Domenech, E.; Viña, J. Moderate exercise is an antioxidant: Upregulation of antioxidant genes by training. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Febbraio, M.A. Muscle as an endocrine organ: Focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 1379–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.K.; Duarte, J.; Kavazis, A.N.; Talbert, E.E. Reactive oxygen species are signalling molecules for skeletal muscle adaptation. Exp. Physiol. 2010, 95, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peake, J.M.; Neubauer, O.; Della Gatta, P.A.; Nosaka, K. Muscle damage and inflammation during recovery from exercise. J. Appl. Physiology 2017, 122, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Su, C.H. The impact of physical exercise on oxidative and nitrosative stress: Balancing the benefits and risks. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.L.; Kang, C.; Zhang, Y. Exercise-induced hormesis and skeletal muscle health. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 98, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Febbraio, M.A. Muscles, exercise and obesity: Skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smirnoff, N.; Cumbes, Q.J. Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of compatible so-lutes. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 1057–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauffenberger, A.; Vaccaro, A.; Aulas, A.; Vande Velde, C.; Parker, J.A. Glucose delays age-dependent proteotoxicity. Aging Cell. 2012, 11, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa-Yokoi, A.; Yabuta, Y.; Shigeoka, S. The contribution of carbo-hydrates including raffinose family oligosaccharides and sugar alcohols to protection of plant cells from oxidative damage. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008, 3, 1016–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, D.C. Influence of carbohydrate on the immune response to intensive, prolonged exercise. Exerc. Immunol. Rev. 1998, 4, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nieman, D.C.; Mitmesser, S.H. Potential Impact of Nutrition on Immune System Recovery from Heavy Exertion: A Metabolomics Perspective. Nutrients 2017, 9, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rosca, M.G.; Vazquez, E.J.; Chen, Q.; Kerner, J.; Kern, T.S.; Hoppel, C.L. Oxidation of fatty acids is the source of increased mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production in kidney cortical tubules in early diabetes. Diabetes 2012, 61, 2074–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Scalbert, A.; Johnson, I.T.; Saltmarsh, M. Polyphenols: Antioxidants and beyond. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Lafuente, A.; Guillamón, E.; Villares, A.; Rostagno, M.A.; Martínez, J.A. Flavonoids as anti-inflammatory agents: Implications in cancer and cardiovascular disease. Inflamm. Res. 2009, 58, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, R. Chemistry and Biochemistry of Dietary Polyphenols. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarewicz, M.; Drożdż, I.; Tarko, T.; Duda-Chodak, A. The interactions between polyphenols and microorganisms, especially gut microbiota. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alov, P.; Tsakovska, I.; Pajeva, I. Computational studies of free radical-scavenging properties of phenolic compounds. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2015, 15, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vertuani, S.; Angusti, A.; Manfredini, S. The antioxidants and pro-antioxidants network: An overview. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2004, 10, 1677–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Cabrera, M.C.; Ristow, M.; Viña, J. Antioxidant supplements in exercise: Worse than useless? Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Me-Tabolism 2012, 302, 476–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristow, M.; Zarse, K.; Oberbach, A.; Klöting, N.; Birringer, M.; Kiehntopf, M.; Stumvoll, M.; Kahn, C.R.; Blüher, M. Antioxidants prevent health-promoting effects of physical exercise in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 8665–8670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, P.G.; Stevenson, E.; Davison, G.W.; Howatson, G. The effects of montmorency tart cherry concentrate supplementation on recovery following pro-longed, intermittent exercise. Nutrients 2016, 8, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaton, L.E.; Davis, J.K.; Rawson, E.S.; Nuccio, R.P.; Witard, O.C.; Stein, K.W.; Baar, K.; Carter, J.M.; Baker, L.B. Selected in-season nutritional strategies to enhance recovery for team sport athletes: A practical overview. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2201–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peternelj, T.T.; Coombes, J.S. Antioxidant supplementation during exercise training: Beneficial or detrimental? Sports Med. 2011, 41, 1043–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Jendricke, P.; Centner, C.; Storck, H.; Gollhofer, A.; König, D. Acute effects of oatmeal on exercise-induced reactive oxygen species production following high-intensity interval training in women: A randomized controlled trial. Antioxidants 2020, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizheh, N.; Jaafari, M. The effect of a single bout circuit resistance exercise on homocysteine, hs-CRP and fibrinogen in sedentary middle aged men. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2011, 14, 568. [Google Scholar]

- Carpinelli, R.N. Challenging the American College of Sports Medicine 2009 position stand on resistance training. Med. Sport 2009, 13, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G.A.V. Psychophysical Bases of Perceived Exertion. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1954, 14, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrakic-Sposta, S.; Gussoni, M.; Montorsi, M.; Porcelli, S.; Vezzoli, A. Assessment of a Standardized ROS Production Profile in Humans by Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 2012, 973927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of ‘‘Antioxidant Power’’: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungsticacid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, R.; Yu, M.; Bruno, R.; Bolling, B.W. Phenolic and tocopherol content of autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellate) berries. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 16, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zain, M.Z.M.; Baba, A.S.; Shori, A.B. Effect of polyphenols enriched from green coffee bean on antioxidant activity and sensory evaluation of bread. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2018, 30, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herchi, W.; Sakouhi, F.; Arráez-Román, D.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Boukhchina, S.; Kallel, H.; Fernández-Gutierrez, A. Changes in the Content of Phenolic Compounds in Flaxseed Oil During Development. J. Am. Oil Chem-Ists’ Soc. 2011, 88, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.V.; Giolo, J.S.; Teixeira, R.R.; Vilela, D.D.; Peixoto, L.G.; Justino, A.B.; Caixeta, D.C.; Puga, G.M.; Espindola, F.S. Salivary and Plasmatic Antioxidant Profile following Contin-uous, Resistance, and High-Intensity Interval Exercise: Preliminary Study. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 5425021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Serafini, M.; Peluso, I. Functional foods for health: The interrelated anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory role of fruits, vegetables, herbs, spices and cocoa in humans. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 6701–6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gallego, J.; García-Mediavilla, M.V.; Sánchez-Campos, S.; Tuñón, M.J. Fruit polyphenols, immunity and inflammation. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, A.; Monteiro, R.; Mateus, N.; Azevedo, I.; Calhau, C. Effect of pomegranate (Punica granatum) juice intake on hepatic oxidative stress. Eur J Nutr. 2007, 46, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Dujaili, E.A.S.; Good, G.; Tsang, K. Consumption of Pomegranate Juice Attenuates Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress, Blood Pressure and Urinary Cortisol/Cortisone Ratio in Human Adults. EC Nutr. 2016, 4, 982–995. [Google Scholar]

- Fuster-Muños, E.; Roche, E.; Funes, L.; Martínez-Peinado, P.; Sempere, J.M.; Vicente-Salar, N. Effects of Pomegranate Juice in Circulating Parameters, Cytokines, and Oxidative Stress Markers in Endurance-Based Athletes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrition 2016, 32, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, D.; Chen, A.; Grace, M.H.; Komarnytsky, S.; Lila, M.A. Inhibi-tory effects of wild blueberry anthocyanins and other flavonoids on biomarkers of acute and chronic inflammation in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 7022–7028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Moody, M.R.; Engel, D.; Walker, S.; Clubb, F.J., Jr.; Sivasubramanian, N.; Mann, D.L.; Reid, M.B. Cardiac-specific overexpression of tumor necrosis factor-α causes oxidative stress and contractile dysfunction in mouse diaphragm. Circulation 2000, 102, 1690–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, B.R.; Gholami, S.; Chua, J.S.; Kuberan, B.; Babu, P.V.A. Blueberry metabolites restore cell surface glycosaminoglycans and attenuate endothelial inflammation in diabetic human aortic endothelial cells. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 261, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Huang, L.; Yu, J. Effects of blueberry anthocyanins on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in diabetes through Nrf2/HO-1 signaling. J. Neuroimmunol. 2016, 301, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAnulty, L.S.; Nieman, D.C.; Dumke, C.L.; Shooter, L.A.; Henson, D.A.; Utter, A.C.; Milne, G.; McAnulty, S.R. Effect of blueberry ingestion on natural killer cell counts, oxidative stress, and inflammation prior to and after 2.5 h of running. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 36, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Saltin, B. Exercise as medicine–evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2025, 25, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finaud, J.; Lac, G.; Filaire, E. Oxidative Stress. Sports Med. 2006, 36, 327–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliwell, B. Free radicals and other reactive species in disease. In Proceedings of the Encyclopedia of Life Science, London, UK, 29 January 2003; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mylonas, C.; Kouretas, D. Lipid peroxidation and tissue damage. In Vivo 1999, 13, 295–309. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Cabrera, M.C.; Borrás, C.; Pallardo, F.V.; Sastre, J.; Ji, L.L.; Viña, J. Decreasing xanthine oxidase-mediated oxidative stress prevents useful cellular adaptations to exercise in rats. J. Physiol. 2005, 567, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, N.; Suvorava, T.; Rüther, U.; Jacob, R.; Meyer, W.; Harrison, D.G.; Kojda, G. Critical involvement of hydrogen peroxide in exercise-induced up-regulation of endothelial NO synthase. Cardiovasc. Res. 2005, 65, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.K.; Deminice, R.; Ozdemir, M.; Yoshihara, T.; Bomkamp, M.P.; Hyatt, H. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: Friend or foe? J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Riddell, M.C.; Takken, T.; Timmons, B.W. Carbohydrate intake reduces fat oxidation during exercise in obese boys. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 3135–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickards, L.; Lynn, A.; Harrop, D.; Barker, M.E.; Russell, M.; Ranchordas, M.K. Effect of Polyphenol-Rich Foods, Juices, and Concentrates on Recovery from Exercise Induced Muscle Damage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, C.C.; Lucey, A.; Doyle, L. Flavonoid Containing Polyphenol Consumption and Recovery from Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2021, 51, 1293–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAnulty, S.R.; McAnulty, L.S.; Morrow, J.D.; Nieman, D.C.; Owens, J.T.; Carper, C.M. Influence of carbohydrate, intense exercise, and rest intervals on hormonal and oxidative changes. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2007, 17, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Baker, J.S.; Davison, G.W.; Yan, X. Redox signaling and skeletal muscle adaptation during aerobic exercise. iScience 2024, 27, 109643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Elosua, R.; Molina, L.; Fito, M.; Arquer, A.; Sanchez-Quesada, J.L.; Covas, M.I.; Marrugat, J. Response of oxidative stress biomarkers to a 16-week aerobic physical activity program, and to acute physical activity, in healthy young men and women. Atherosclerosis 2003, 167, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, M.I.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Hess-Pierce, B.; Holcroft, D.M.; Kader, A.A. Antioxidant activity of pomegranate juice and its relationship with phenolic composition and processing. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2000, 48, 4581–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohrab, G.; Angoorani, P.; Tohidi, M.; Tabibi, H.; Kimiagar, M.; Nasrollahzadeh, J. Pomegranate (Punica granatum) juice decreases lipid peroxidation, but has no effect on plasma advanced glycated end-products in adults with type 2 diabetes: A randomized double-blind clinical trial. Food Nutr. Res. 2015, 59, 28551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Felgus-Lavefve, L.; Howard, L.; Adams, S.H.; Baum, J.I. The Effects of Blueberry Phytochemicals on Cell Models of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 1279–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martini, D.; Marino, M.; Venturi, S.; Tucci, M.; Klimis-Zacas, D.; Riso, P.; Porrini, M.; Del Bo, C. Blueberries and their bioactives in the modulation of oxidative stress, inflammation and cardio/vascular function markers: A systematic review of human intervention studies. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2023, 111, 109154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enright, L.; Slavin, J. No effect of 14 day consumption of whole grain diet compared to refined grain diet on antioxidant measures in healthy, young subjects: A pilot study. Nutr. J. 2010, 19, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chung, S.; Hwang, J.-T.; Park, S.-H. Physiological Effects of Bioactive Compounds Derived from Whole Grains on Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Liang, C.; Zuo, B.; Wang, M. Diet, oxidative stress, and the mediating role of obesity in postmenopausal women. BMC Women’s Health 2025, 25, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S.; Chan, A.W.; Collins, G.S.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Tunn, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Berkwits, M.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. CONSORT 2025 Statement: Updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. BMJ 2025, 388, e081123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nutrients/Portion | Pomegranate Juice | Blueberries | Whole-Grain Bread | Bread Roll |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portion-size | 250 mL | 125 g | 90 g | 60 g |

| Energy (kcal) | 160.0 | 62.5 | 245.7 | 207.4 |

| Fat (g) | <1.3 | 0.9 | 4.50 | 2.2 |

| - of which SFAs (g) | <0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Carbohydrates | 35.0 | 10.6 | 38.5 | 40.0 |

| - of which sugars (g) | 35.0 | 9.5 | 1.8 | 0.3 |

| Fiber (g) | 2.8 | 5.0 | 6.48 | 2.3 |

| Protein (g) | <1.3 | 0.88 | 9.63 | 5.7 |

| Sodium (g) | <0.1 | <0.1 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| Polyphenol content (mg) | 965.5 | 552.5 | 174.6 | 29.00 |

| Marker | Intervention | Baseline | Pre-HIIT | Post-HIIT | 15 min Post-HIIT | T | T × G | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROS (µmol/min) | Blueberries | 1.00 ± 0.39 | 0.84 ± 0.25 | 0.97 ± 0.33 | 0.93 ± 0.27 | <0.001 | 0.123 | 0.536 |

| Bread roll | 1.00 ± 0.26 | 0.82 ± 0.21 | 0.93 ± 0.27 | 0.91 ± 0.26 | ||||

| Pomegranate | 1.09 ± 0.22 | 0.93 ± 0.18 | 1.18 ± 0.27 | 0.99 ± 0.28 | ||||

| Whole Grain | 0.95 ± 0.27 | 0.87 ± 0.24 | 0.93 ± 0.26 | 0.91 ± 0.22 | ||||

| Water | 0.98 ± 0.25 | 0.91 ± 0.21 | 1.03 ± 0.29 | 0.94 ± 0.22 | ||||

| FRAP [mM TEAC] | Blueberries | 828.4 ± 68.8 | 812.0 ± 80.0 | 841.0 ± 77.0 | 932.8 ± 75.3 | <0.001 | 0.346 | 0.510 |

| Bread roll | 803.2 ± 80.1 | 771.2 ± 76.2 | 788.6 ± 77.3 | 892.5 ± 69.9 | ||||

| Pomegranate | 830.7 ± 72.5 | 811.6 ± 71.2 | 843.8 ± 82.7 | 926.8 ± 86.5 | ||||

| Whole Grain | 822.3 ± 73.4 | 807.5 ± 83.1 | 811.7 ± 75.0 | 924.2 ± 80.5 | ||||

| Water | 806.6 ± 79.3 | 783.1 ± 67.2 | 818.6 ±78.8 | 928.3 ± 92.1 | ||||

| Intervention | Δ ROS Pre → Post % | Δ FRAP Pre → Post % |

|---|---|---|

| Blueberries (n = 16) | +12.96 ± 10.52 | +2.59 ± 2.41 |

| Pomegranate J. (n = 14) | +23.46 ± 14.71 | +4.75 ± 3.16 |

| Bread roll (n = 16) | +12.53 ± 9.13 | +1.68 ± 3.13 |

| Whole grains (n = 16) | +7.69 ± 5.48 | +1.20 ± 1.75 |

| Water (n = 30) | +12.29 ± 10.63 | +3.93 ± 2.29 |

| Intervention | Δ ROS Post vs. 15 Post % | Δ FRAP Post—15 Post % |

|---|---|---|

| Blueberries | −7.41 ± 5.72 | +11.44 ± 4.83 |

| Pomegranate juice | −13.99 ± 11.83 | +11.37 ± 4.08 |

| Bread roll | −2.52 ± 4.42 | +13.33 ± 3.89 |

| Whole grains | −2.00 ± 6.57 | +13.49 ± 5.00 |

| Water | −6.92 ± 10.24 | +13.47 ± 3.05 |

| Intervention | BORG Pre-HIIT | BORG Post-HIIT | Δ % Pre–Post HIIT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blueberries | 6.06 ± 0.25 | 16.78 ± 1.54 | 177.15 ± 27.20 |

| Pomegranate Juice | 6.21 ± 0.58 | 17.68 ± 1.25 | 186.39 ± 30.46 |

| Bread Roll | 6.03 ± 0.13 | 16.13 ± 1.37 | 167.47 ± 23.56 |

| Whole Grain | 6.06 ± 0.25 | 16.31 ± 1.66 | 169.35 ± 28.42 |

| Water | 6.22 ± 0.55 | 17.33 ± 1.57 | 180.93 ± 35.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gassner, M.; Bragagna, L.; Dasht Bayaz, H.H.; Stumpf-Knaus, C.; Schlosser, L.; Lemberg, J.; Brem, J.; Pignitter, M.; Strauss, M.; Wagner, K.-H.; et al. Acute Impact of Polyphenol-Rich vs. Carbohydrate-Rich Foods and Beverages on Exercise-Induced ROS and FRAP in Healthy Sedentary Female Adults—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1481. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121481

Gassner M, Bragagna L, Dasht Bayaz HH, Stumpf-Knaus C, Schlosser L, Lemberg J, Brem J, Pignitter M, Strauss M, Wagner K-H, et al. Acute Impact of Polyphenol-Rich vs. Carbohydrate-Rich Foods and Beverages on Exercise-Induced ROS and FRAP in Healthy Sedentary Female Adults—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1481. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121481

Chicago/Turabian StyleGassner, Markus, Laura Bragagna, Helia Heidari Dasht Bayaz, Caroline Stumpf-Knaus, Laura Schlosser, Julia Lemberg, Julia Brem, Marc Pignitter, Matthias Strauss, Karl-Heinz Wagner, and et al. 2025. "Acute Impact of Polyphenol-Rich vs. Carbohydrate-Rich Foods and Beverages on Exercise-Induced ROS and FRAP in Healthy Sedentary Female Adults—A Randomized Controlled Trial" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1481. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121481

APA StyleGassner, M., Bragagna, L., Dasht Bayaz, H. H., Stumpf-Knaus, C., Schlosser, L., Lemberg, J., Brem, J., Pignitter, M., Strauss, M., Wagner, K.-H., & König, D. (2025). Acute Impact of Polyphenol-Rich vs. Carbohydrate-Rich Foods and Beverages on Exercise-Induced ROS and FRAP in Healthy Sedentary Female Adults—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1481. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121481