Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants Prevent Tachypacing-Induced Contractile Dysfunction in In Vitro Cardiomyocyte and In Vivo Drosophila Models of Atrial Fibrillation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Drosophila Melanogaster

2.3. Measurement of Calcium Transient for Contractility

2.4. Cell Contractility Measurement

2.5. Measurement of Mitochondrial Respiration

2.6. Immunohistochemical Analysis of ROS Damage

2.7. SOD1 and SOD2 KD in iAMs

2.8. Drosophila Cardiac Function

2.9. ROS Measurement Drosophila

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. MitoTEMPO and Sul-238 Treatment Prevents Tachypacing-Induced Contractile Dysfunction in iAMs

3.2. MitoTEMPO and Sul-238 Treatment Prevents Tachypacing-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction in iAMs

3.3. MitoTEMPO and Sul-238 Treatment Prevents Tachypacing-Induced ROS Damage in iAMs

3.4. SOD2 Knockdown Induces Contractile Dysfunction in iAMs

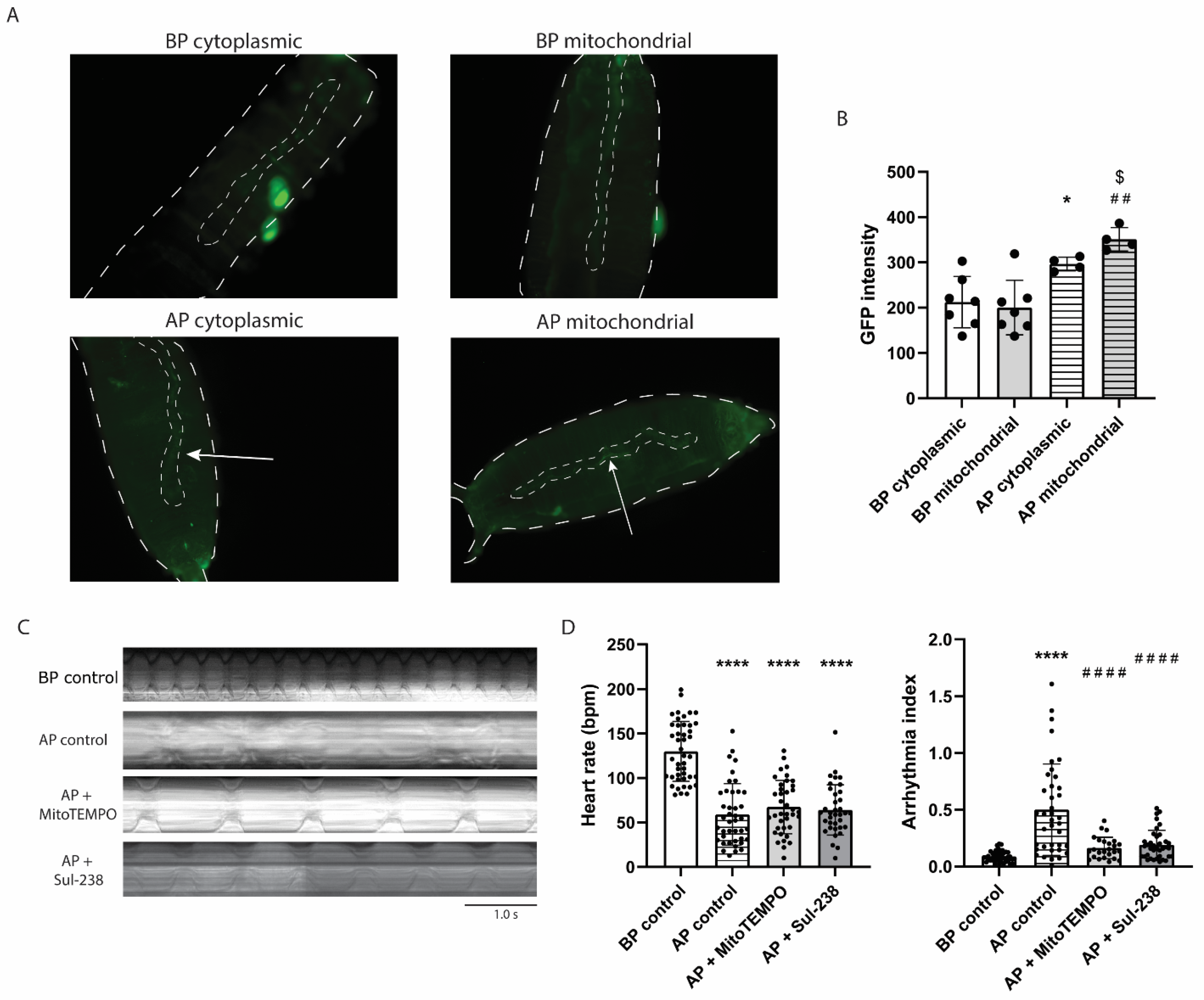

3.5. MitoTEMPO and Sul-238 Treatment Prevents Tachypacing-Induced Arrhythmia in Drosophila

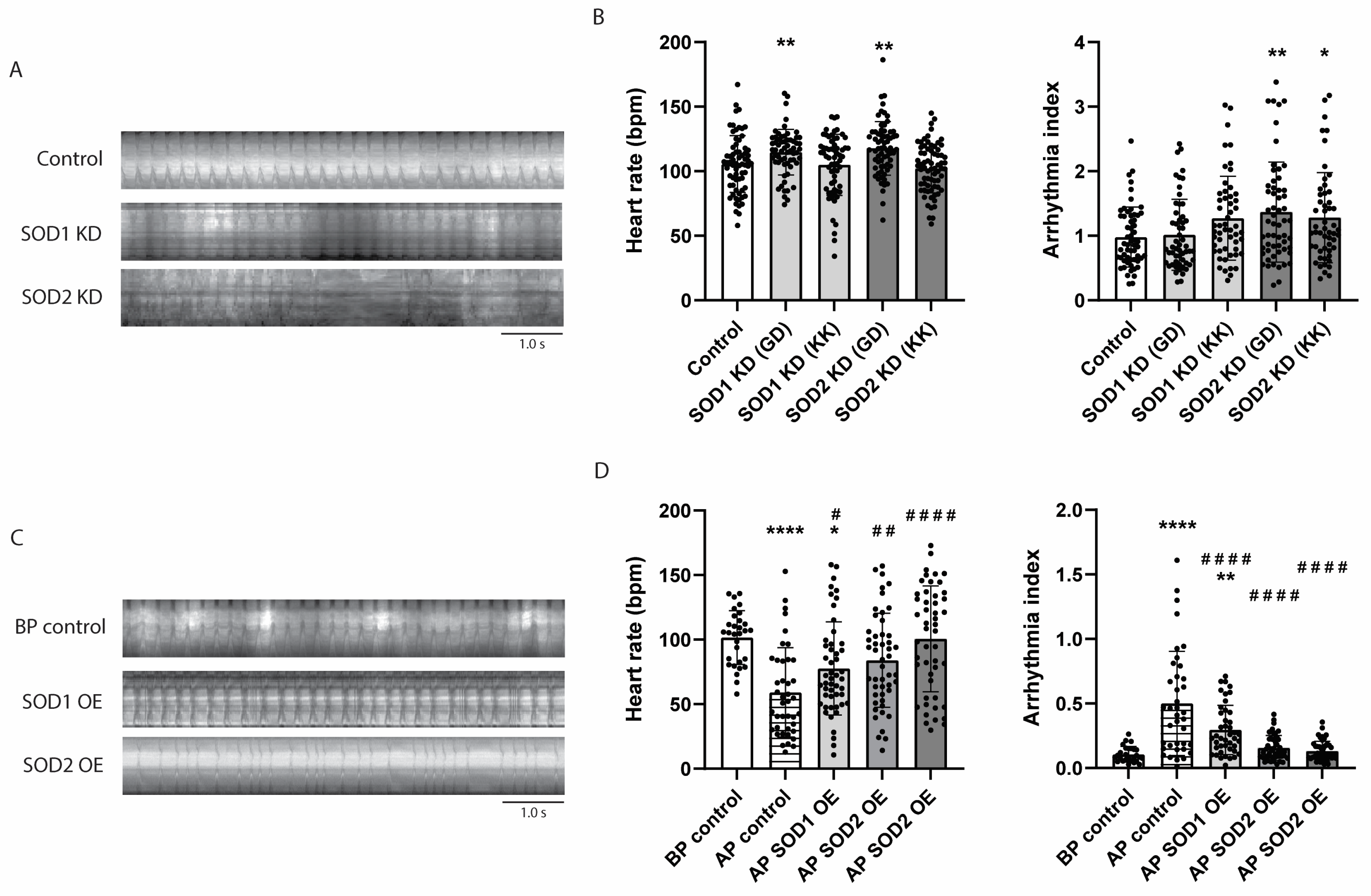

3.6. SOD2 Knockdown Causes Arrhythmia in Drosophila, Whereas Its Overexpression Prevents Tachypacing-Induced Arrhythmia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 4-HNE | 4-hydroxynonenal |

| 8-OxoG | 8-oxoguanine |

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| CaT | Calcium transient |

| iAMs | Immortalized atrial myocytes |

| MitoOxS | Mitochondrial oxidative stress |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| UAS | Upstream activating sequence |

References

- Kornej, J.; Börschel, C.S.; Benjamin, E.J.; Schnabel, R.B. Epidemiology of Atrial Fibrillation in the 21st Century: Novel Methods and New Insights. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilaveris, P.E.; Kennedy, H.L. Silent atrial fibrillation: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and clinical impact. Clin. Cardiol. 2017, 40, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyasaka, Y.; Barnes, M.E.; Gersh, B.J.; Cha, S.S.; Bailey, K.R.; Abhayaratna, W.P.; Seward, J.B.; Tsang, T.S. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence. Circulation 2006, 114, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krijthe, B.P.; Kunst, A.; Benjamin, E.J.; Lip, G.Y.; Franco, O.H.; Hofman, A.; Witteman, J.C.; Stricker, B.H.; Heeringa, J. Projections on the number of individuals with atrial fibrillation in the European Union, from 2000 to 2060. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 2746–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfenniger, A.; Yoo, S.; Arora, R. Oxidative stress and atrial fibrillation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2024, 196, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihm, M.J.; Yu, F.; Carnes, C.A.; Reiser, P.J.; McCarthy, P.M.; Van Wagoner, D.R.; Bauer, J.A. Impaired myofibrillar energetics and oxidative injury during human atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2001, 104, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Santulli, G.; Reiken, S.R.; Yuan, Q.; Osborne, B.W.; Chen, B.X.; Marks, A.R. Mitochondrial oxidative stress promotes atrial fibrillation. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesso, H.D.; Buring, J.E.; Christen, W.G.; Kurth, T.; Belanger, C.; MacFadyen, J.; Bubes, V.; Manson, J.E.; Glynn, R.J.; Gaziano, J.M. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in men: The Physicians’ Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008, 300, 2123–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauriello, A.; Correra, A.; Molinari, R.; Del Vecchio, G.E.; Tessitore, V.; D’Andrea, A.; Russo, V. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Atrial Fibrillation: The Need for a Strong Pharmacological Approach. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trnka, J.; Blaikie, F.H.; Smith, R.A.J.; Murphy, M.P. A mitochondria-targeted nitroxide is reduced to its hydroxylamine by ubiquinol in mitochondria. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 1406–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, J.; Meng, X.; Zuo, S.; Wang, W.; Yuan, H.; Lan, M. Novel piperidine nitroxide derivatives: Synthesis, electrochemical and antioxidative evaluation. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2008, 45, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelaar, P.C.; Nakladal, D.; Swart, D.H.; Tkáčiková, Ľ.; Tkáčiková, S.; van der Graaf, A.C.; Henning, R.H.; Krenning, G. Towards prevention of ischemia-reperfusion kidney injury: Pre-clinical evaluation of 6-chromanol derivatives and the lead compound SUL-138. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 168, 106033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajmousa, G.; Vogelaar, P.; Brouwer, L.A.; van der Graaf, A.C.; Henning, R.H.; Krenning, G. The 6-chromanol derivate SUL-109 enables prolonged hypothermic storage of adipose tissue-derived stem cells. Biomaterials 2017, 119, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Star, B.S.; van der Slikke, E.C.; van Buiten, A.; Henning, R.H.; Bouma, H.R. The Novel Compound SUL-138 Counteracts Endothelial Cell and Kidney Dysfunction in Sepsis by Preserving Mitochondrial Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jüttner, A.A.; Mohammadi Jouabadi, S.; van der Linden, J.; de Vries, R.; Barnhoorn, S.; Garrelds, I.M.; Goos, Y.; van Veghel, R.; van der Pluijm, I.; Danser, A.H.J.; et al. The modified 6-chromanol SUL-238 protects against accelerated vascular aging in vascular smooth muscle Ercc1-deficient mice. J. Cardiovasc. Aging 2024, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.F. Superoxide dismutases: Ancient enzymes and new insights. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Volkers, L.; Jangsangthong, W.; Bart, C.I.; Engels, M.C.; Zhou, G.; Schalij, M.J.; Ypey, D.L.; Pijnappels, D.A.; de Vries, A.A.F. Generation and primary characterization of iAM-1, a versatile new line of conditionally immortalized atrial myocytes with preserved cardiomyogenic differentiation capacity. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 1848–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryder, E.; Blows, F.; Ashburner, M.; Bautista-Llacer, R.; Coulson, D.; Drummond, J.; Webster, J.; Gubb, D.; Gunton, N.; Johnson, G.; et al. The DrosDel Collection: A Set of P-Element Insertions for Generating Custom Chromosomal Aberrations in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 2004, 167, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellin, J.; Albrecht, S.; Kölsch, V.; Paululat, A. Dynamics of heart differentiation, visualized utilizing heart enhancer elements of the Drosophila melanogaster bHLH transcription factor Hand. Gene Expr. Patterns 2006, 6, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; MacKenzie, K.R.; Putluri, N.; Maletić-Savatić, M.; Bellen, H.J. The Glia-Neuron Lactate Shuttle and Elevated ROS Promote Lipid Synthesis in Neurons and Lipid Droplet Accumulation in Glia via APOE/D. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.C.; Barata, A.G.; Großhans, J.; Teleman, A.A.; Dick, T.P. In Vivo Mapping of Hydrogen Peroxide and Oxidized Glutathione Reveals Chemical and Regional Specificity of Redox Homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, S.C.; Sobotta, M.C.; Bausewein, D.; Aller, I.; Hell, R.; Dick, T.P.; Meyer, A.J. Redesign of genetically encoded biosensors for monitoring mitochondrial redox status in a broad range of model eukaryotes. J. Biomed. Screen. 2014, 19, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Baks-Te Bulte, L.; Wiersma, M.; Malik, N.U.; van Marion, D.M.S.; Tolouee, M.; Hoogstra-Berends, F.; et al. DNA damage-induced PARP1 activation confers cardiomyocyte dysfunction through NAD+ depletion in experimental atrial fibrillation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ke, L.; Mackovicova, K.; Van Der Want, J.J.; Sibon, O.C.; Tanguay, R.M.; Morrow, G.; Henning, R.H.; Kampinga, H.H.; Brundel, B.J. Effects of different small HSPB members on contractile dysfunction and structural changes in a Drosophila melanogaster model for Atrial Fibrillation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011, 51, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Hoogstra-Berends, F.; Zhuang, Q.; Esteban, M.A.; de Groot, N.; Henning, R.H.; Brundel, B. Converse role of class I and class IIa HDACs in the progression of atrial fibrillation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018, 125, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibertz, F.; Rubio, T.; Springer, R.; Popp, F.; Ritter, M.; Liutkute, A.; Bartelt, L.; Stelzer, L.; Haghighi, F.; Pietras, J.; et al. Atrial fibrillation-associated electrical remodelling in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived atrial cardiomyocytes: A novel pathway for antiarrhythmic therapy development. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 2623–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersma, M.; van Marion, D.M.S.; Wüst, R.C.I.; Houtkooper, R.H.; Zhang, D.; Groot, N.M.S.; Henning, R.H.; Brundel, B. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Underlies Cardiomyocyte Remodeling in Experimental and Clinical Atrial Fibrillation. Cells 2019, 8, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ježek, J.; Cooper, K.F.; Strich, R. Reactive Oxygen Species and Mitochondrial Dynamics: The Yin and Yang of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Cancer Progression. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhan, L.; Cao, H.; Li, J.; Lyu, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Ji, L.; Ren, T.; An, J.; et al. Increased mitochondrial fission promotes autophagy and hepatocellular carcinoma cell survival through the ROS-modulated coordinated regulation of the NFKB and TP53 pathways. Autophagy 2016, 12, 999–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukai, T.; Ushio-Fukai, M. Superoxide dismutases: Role in redox signaling, vascular function, and diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 1583–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowse, H.; Ringo, J.; Power, J.; Johnson, E.; Kinney, K.; White, L. A congenital heart defect in Drosophila caused by an action-potential mutation. J. Neurogenet. 1995, 10, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piazza, N.; Wessells, R.J. Drosophila models of cardiac disease. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2011, 100, 155–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, P.; Desplantez, T.; El-Harasis, M.A.; Chowdhury, R.A.; Ullrich, N.D.; Cabestrero de Diego, A.; Peters, N.S.; Severs, N.J.; MacLeod, K.T.; Dupont, E. Characterisation of connexin expression and electrophysiological properties in stable clones of the HL-1 myocyte cell line. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xu, X.; Jin, K.; Bais, A.S.; Zhu, W.; Yagi, H.; Feinstein, T.N.; Nguyen, P.K.; Criscione, J.D.; Liu, X.; Beutner, G.; et al. Uncompensated mitochondrial oxidative stress underlies heart failure in an iPSC-derived model of congenital heart disease. Cell Stem Cell 2022, 29, 840–855.e847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubert, M.A.; Yow, E.; Dunn, G.; Marchev, S.; Barnhart, H.; Douglas, P.S.; O’Connor, C.; Goldstein, S.; Udelson, J.E.; Sabbah, H.N. Novel Mitochondria-Targeting Peptide in Heart Failure Treatment: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Elamipretide. Circ. Heart Fail. 2017, 10, e004389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán Mentesana, G.; Báez, A.L.; Lo Presti, M.S.; Domínguez, R.; Córdoba, R.; Bazán, C.; Strauss, M.; Fretes, R.; Rivarola, H.W.; Paglini-Oliva, P. Functional and structural alterations of cardiac and skeletal muscle mitochondria in heart failure patients. Arch. Med. Res. 2014, 45, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Shangguan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Li, G. Effects of trimetazidine on mitochondrial respiratory function, biosynthesis, and fission/fusion in rats with acute myocardial ischemia. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2017, 18, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, P.; Wanagat, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liem, D.A.; Ping, P.; Antoshechkin, I.A.; Margulies, K.B.; Maclellan, W.R. Divergent mitochondrial biogenesis responses in human cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2013, 127, 1957–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jheng, H.F.; Tsai, P.J.; Guo, S.M.; Kuo, L.H.; Chang, C.S.; Su, I.J.; Chang, C.R.; Tsai, Y.S. Mitochondrial fission contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012, 32, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.; Robotham, J.L.; Yoon, Y. Increased production of reactive oxygen species in hyperglycemic conditions requires dynamic change of mitochondrial morphology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 2653–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, D.H.; Nakamura, T.; Fang, J.; Cieplak, P.; Godzik, A.; Gu, Z.; Lipton, S.A. S-nitrosylation of Drp1 mediates beta-amyloid-related mitochondrial fission and neuronal injury. Science 2009, 324, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.J.; Gan, T.Y.; Tang, B.P.; Chen, Z.H.; Mahemuti, A.; Jiang, T.; Song, J.G.; Guo, X.; Li, Y.D.; Miao, H.J.; et al. Accelerated fibrosis and apoptosis with ageing and in atrial fibrillation: Adaptive responses with maladaptive consequences. Exp. Ther. Med. 2013, 5, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiroshita-Takeshita, A.; Schram, G.; Lavoie, J.; Nattel, S. Effect of simvastatin and antioxidant vitamins on atrial fibrillation promotion by atrial-tachycardia remodeling in dogs. Circulation 2004, 110, 2313–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnes, C.A.; Chung, M.K.; Nakayama, T.; Nakayama, H.; Baliga, R.S.; Piao, S.; Kanderian, A.; Pavia, S.; Hamlin, R.L.; McCarthy, P.M.; et al. Ascorbate attenuates atrial pacing-induced peroxynitrite formation and electrical remodeling and decreases the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation. Circ. Res. 2001, 89, E32–E38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, Z.B.; Rhee, J.W.; Deng, Y.; Wang, Z.V. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cardiac Arrhythmias. Cells 2023, 12, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avula, U.M.R.; Dridi, H.; Chen, B.X.; Yuan, Q.; Katchman, A.N.; Reiken, S.R.; Desai, A.D.; Parsons, S.; Baksh, H.; Ma, E.; et al. Attenuating persistent sodium current-induced atrial myopathy and fibrillation by preventing mitochondrial oxidative stress. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e147371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olgar, Y.; Billur, D.; Tuncay, E.; Turan, B. MitoTEMPO provides an antiarrhythmic effect in aged-rats through attenuation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 136, 110961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.L.; Stuppard, R.; Mattson-Hughes, A.; Marcinek, D.J. Inducible and reversible SOD2 knockdown in mouse skeletal muscle drives impaired pyruvate oxidation and reduced metabolic flexibility. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 226, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Bhattarai, S.; Ara, H.; Sun, G.; St Clair, D.K.; Bhuiyan, M.S.; Kevil, C.; Watts, M.N.; Dominic, P.; Shimizu, T.; et al. SOD2 deficiency in cardiomyocytes defines defective mitochondrial bioenergetics as a cause of lethal dilated cardiomyopathy. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Remmen, H.; Williams, M.D.; Guo, Z.; Estlack, L.; Yang, H.; Carlson, E.J.; Epstein, C.J.; Huang, T.T.; Richardson, A. Knockout mice heterozygous for Sod2 show alterations in cardiac mitochondrial function and apoptosis. Am. J. Physiol. -Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001, 281, H1422–H1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakis, G.K.; Lick, S.; Patterson, C. Postischemic Recovery of Contractile Function is Impaired in SOD2+/− but Not SOD1+/− Mouse Hearts. Circulation 2002, 105, 981–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennicke, C.; Cochemé, H.M. Redox signalling and ageing: Insights from Drosophila. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020, 48, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wu, C.T.; Qi, X.; Meijering, R.A.; Hoogstra-Berends, F.; Tadevosyan, A.; Cubukcuoglu Deniz, G.; Durdu, S.; Akar, A.R.; Sibon, O.C.; et al. Activation of histone deacetylase-6 induces contractile dysfunction through derailment of α-tubulin proteostasis in experimental and human atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2014, 129, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Hoed, M.; Eijgelsheim, M.; Esko, T.; Brundel, B.J.; Peal, D.S.; Evans, D.M.; Nolte, I.M.; Segrè, A.V.; Holm, H.; Handsaker, R.E.; et al. Identification of heart rate-associated loci and their effects on cardiac conduction and rhythm disorders. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessells, R.J.; Fitzgerald, E.; Cypser, J.R.; Tatar, M.; Bodmer, R. Insulin regulation of heart function in aging fruit flies. Nat Genet 2004, 36, 1275–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Wang, Z.; Carmone, C.; Keijer, J.; Zhang, D. Role of Oxidative DNA Damage and Repair in Atrial Fibrillation and Ischemic Heart Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Ramos, K.S.; Baks, L.; Wiersma, M.; Lanters, E.A.H.; Bogers, A.; de Groot, N.M.S.; Brundel, B. Blood-based 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine level: A potential diagnostic biomarker for atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2021, 18, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van Rinsum, A.; Hu, L.; Qi, X.; Keijer, J.; Zhang, D. Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants Prevent Tachypacing-Induced Contractile Dysfunction in In Vitro Cardiomyocyte and In Vivo Drosophila Models of Atrial Fibrillation. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121444

van Rinsum A, Hu L, Qi X, Keijer J, Zhang D. Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants Prevent Tachypacing-Induced Contractile Dysfunction in In Vitro Cardiomyocyte and In Vivo Drosophila Models of Atrial Fibrillation. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121444

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Rinsum, Alexia, Liangyu Hu, Xi Qi, Jaap Keijer, and Deli Zhang. 2025. "Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants Prevent Tachypacing-Induced Contractile Dysfunction in In Vitro Cardiomyocyte and In Vivo Drosophila Models of Atrial Fibrillation" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121444

APA Stylevan Rinsum, A., Hu, L., Qi, X., Keijer, J., & Zhang, D. (2025). Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants Prevent Tachypacing-Induced Contractile Dysfunction in In Vitro Cardiomyocyte and In Vivo Drosophila Models of Atrial Fibrillation. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121444