Phytochemistry, Biological Activities, Molecular Mechanisms, and Toxicity of Saffron (Crocus sativus L.): A Comprehensive Overview

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

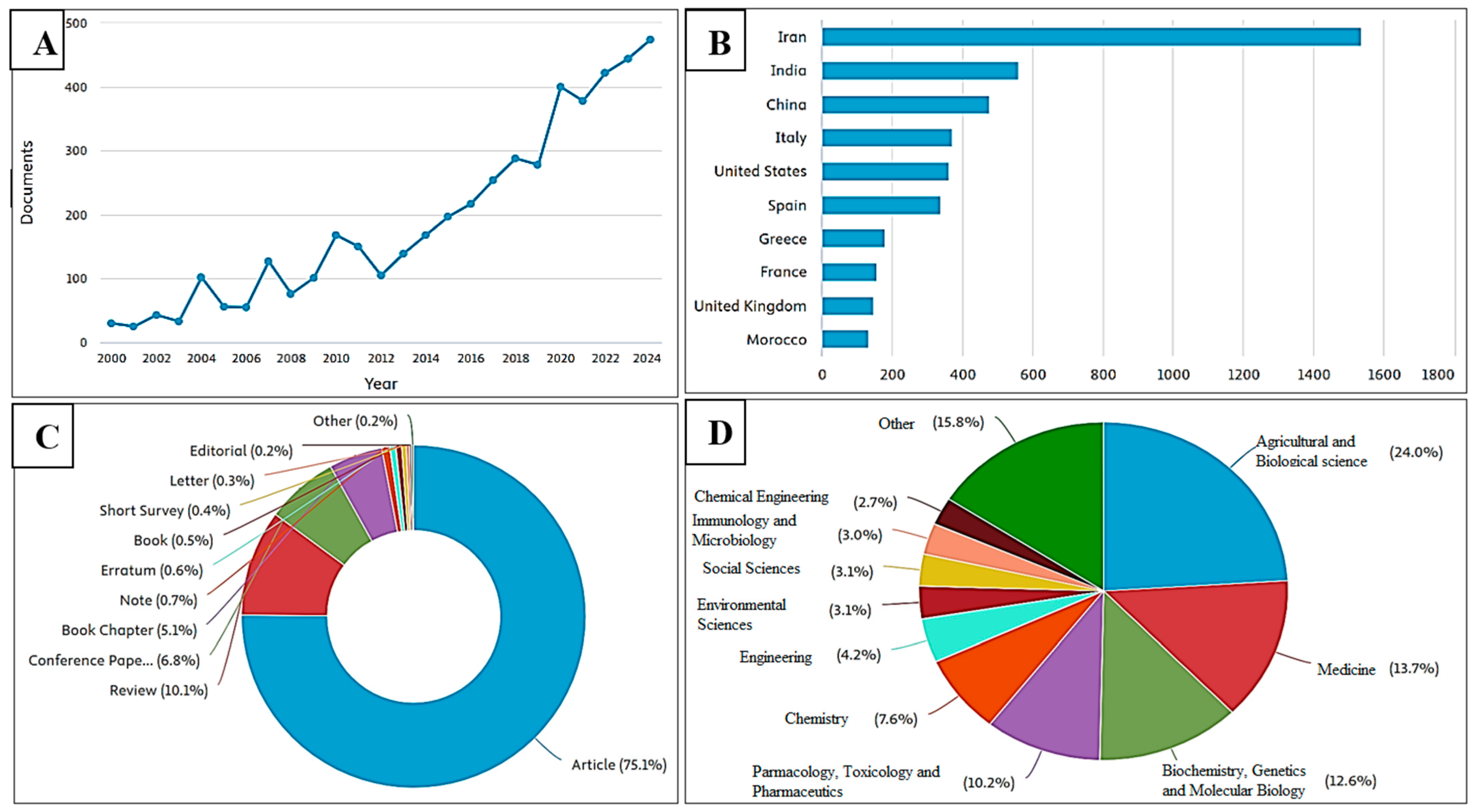

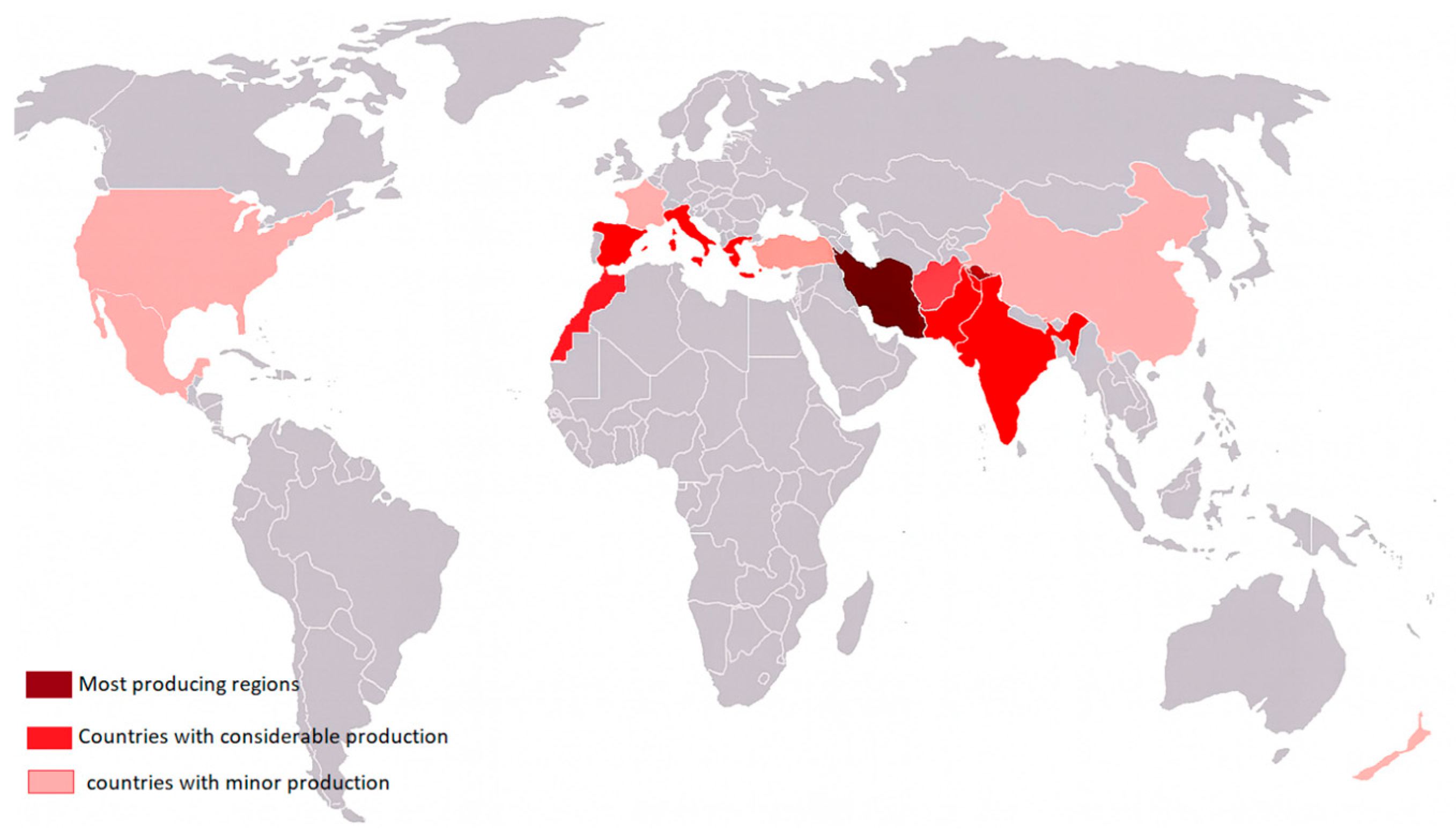

3. Evolution of Trends in Research with Crocus sativus

4. Crocus sativus Taxonomy

5. Saffron Natural Bioactive Compounds

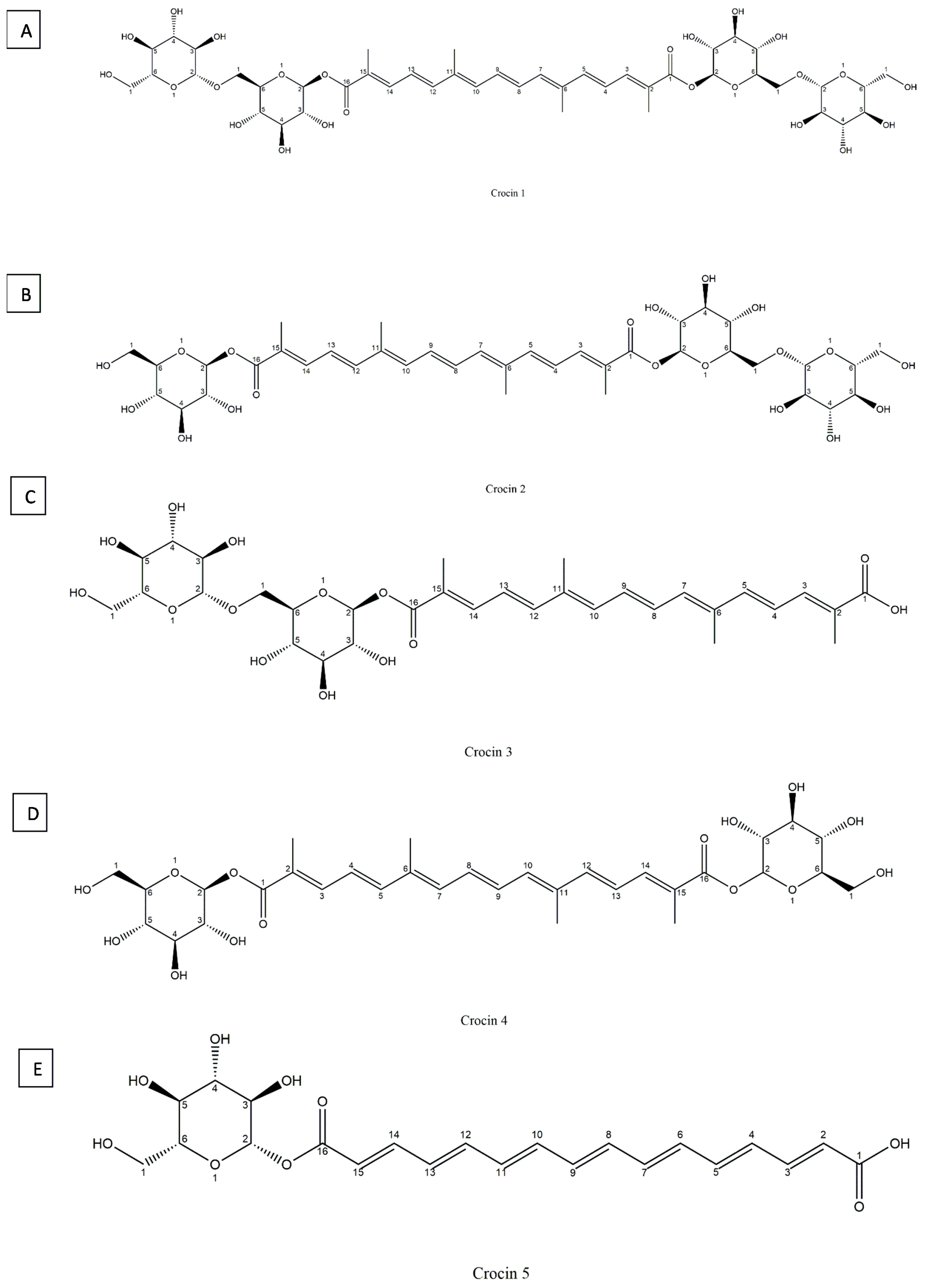

5.1. Crocin

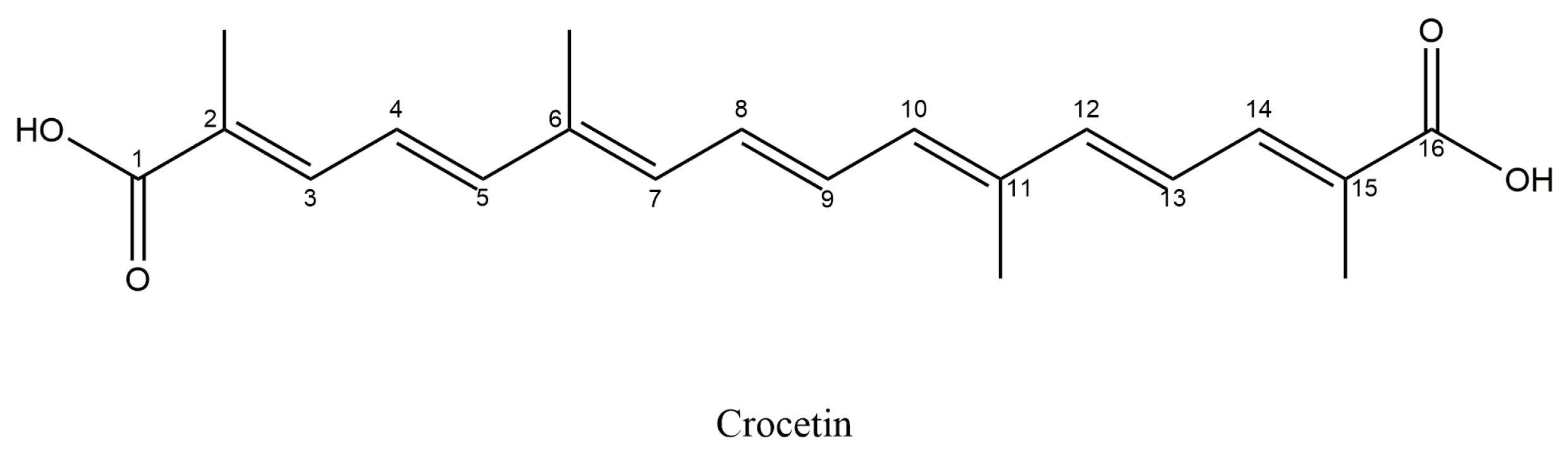

5.2. Crocetin

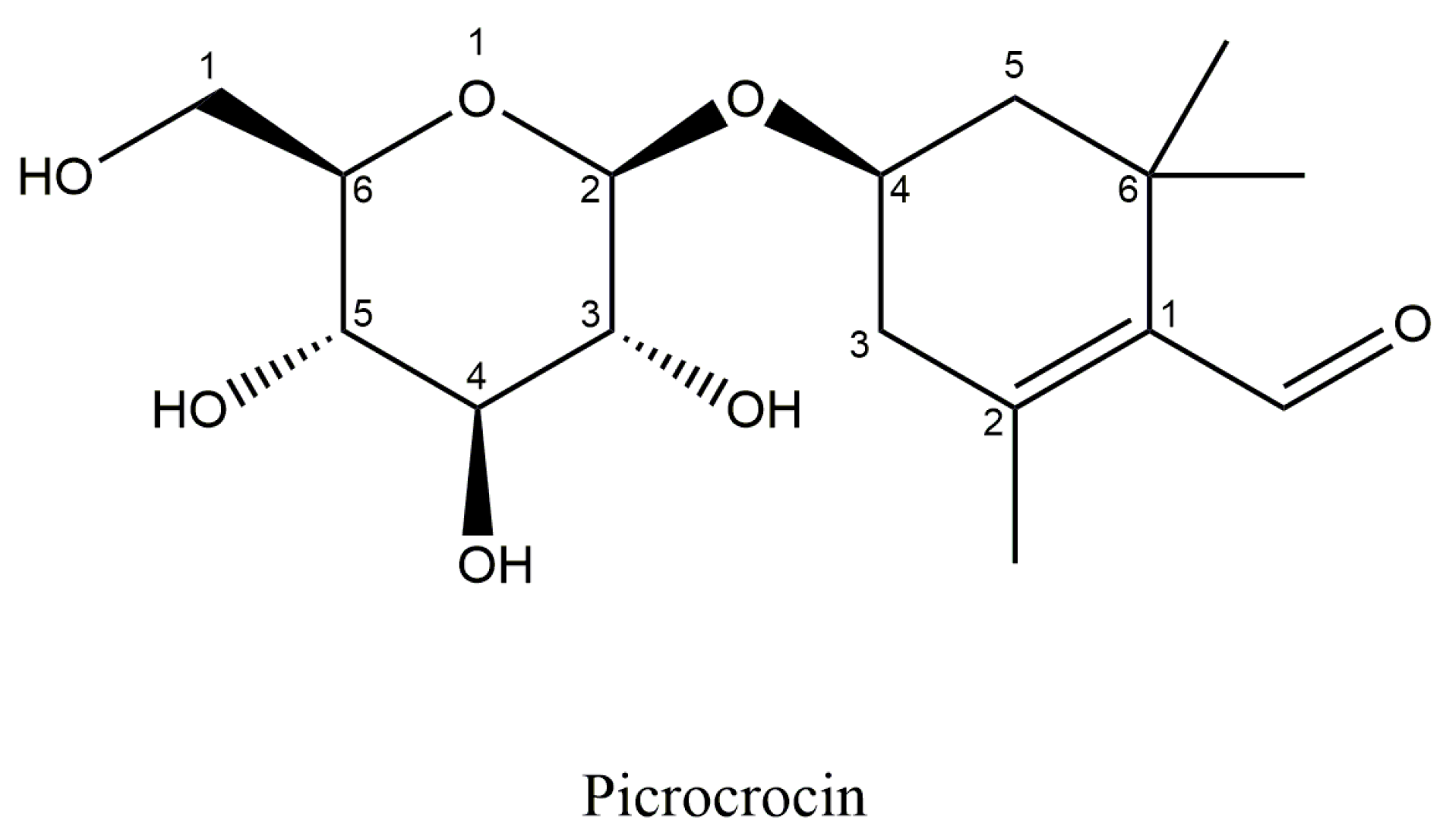

5.3. Picrocrocin

5.4. Safranal

6. Benefits of Saffron Stigmas on Human Health and Disease Conditions

6.1. Antioxidant Activity

6.2. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

6.3. Immunomodulatory Effects

6.4. Anti-Cancer Activity

6.5. Protection Against Neurological Disorders

| Treatment | Methods of Analysis | Major Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crocin (50 mg/kg, i.p.) | PTSD (3 consecutive shocks 0.6 mA, 3 s, along with a sound: 75 dB for 3 s) | Crocin+ extinction learning: ↓ PTSD-like behavior freezing; ↑ BDNF; ↑ pain threshold. | [88] |

| crocin (10, 30, and 50 mg/kg, i.p.) | Maternal Social isolation from PND 30 to 80 (50 days) | Crocin (30 and 50 mg/kg) ↑ (GSK-3beta) in the hippocampus; ↑ locomotion; enhance memory; ↓ anxiety and depressive-like behaviors; ↓ GSK-3beta level | [89] |

| Crocin (0.1 to 100 μM) | MPP+-induced apoptosis to PC12 cells | Inhibition of MPP+ mitochondrial dysfunction; ↓ ER stress by regulation of CHOP-Wnt pathway, ↓ apoptosis induced by MPP+ | [103] |

| crocin (30 mg/kg, i.p.) | Repetitive mild traumatic brain injury (rmTBI) | ↓ cytokine IL-6; ↑ anti-apoptotic cytokine IL-10; ↓caspase3, Bax and P53; ↑ mRNA levels of Bcl-2, ↑ Nrf2; ↑ HO-1 and NQO-1; ↓ NF-κB | [90] |

| Crocin (10, 20, and 30 mg/kg by oral gavage) for 4 weeks | Unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS) induced anxiety and depression in rats | ↓ Serum corticosterone levels, MDA, TNF-α, IL-6; ↑ IL-10, SOD, CAT, Thiols, ↑ BDNF | [91] |

| C. sativus (50 mg/kg by oral gavage) | Lead (Pb) induced neurotoxicity in Meriones strains | ↓ Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH) to normal, restore locomotor activity by 90% | [92] |

| Crocin tablet (30 mg/day, 8 weeks) | chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) | ↓ Grade of sensory, motor, and neuropathic pain; ↓ adverse effects, lower toxicity | [99] |

| saffron methanolic extract/crocin-enrichment | Rotenone (ROT)-induced locomotor neurotoxicity in the Drosophila model | ↑ GSH.THIOLS; ↓ AChE activity and restore dopamine levels; ↑ life span; ↑ locomotor phenotype | [93] |

| saffron extract 60 mg/kg by oral gavage | diode laser burns induced ocular hypertension (OHT) | ↓ microglion, reversed OHT-induced down-regulation of P2RY12; prevented retinal ganglion cell death in OHT eyes; ↓ neuroinflammation; ↑ intraocular pressure | [104] |

| Crocin (30 mg/kg/day; i.p., for 30 days) | rotenone (ROT)-induced Parkinson’s Disease in rats | ↑ phospho-proline-rich Akt, mTOR and p-p70S6K levels; stimulated PI3K/Akt pathway; ↓ caspase-9, attenuating neurodegeneration (↑ TH and DA); Akt/mTOR activation | [94] |

| saffron extract (100 or 200 mg/kg, Ip, for 3 weeks) | cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury (I/R) in rats | ↓ MDA, ↓ NO and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP); ↑ GSH; ↓ apoptosis (↓ caspase-3 and Bax protein); ↑ vascular endothelial growth factor | [95] |

| Safranal (72.5 and 145 mg/kg, ip) | Focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury model | ↑ total sulfhydryl (SH); ↓ thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS); ↓ MDA; ↓ infarct volume and hippocampal cell loss, | [96] |

| Crocin (20 mg/kg) | Cortical impact induced traumatic brain injury (TBI) in C57BL/6 mice | ↑ neurological severity score (NSS); ↓ microglial activation; ↓ cell apoptosis; activation of Notch signaling | [105] |

| Safranal (25, 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg, ip, for 3 days) | Laminectomy-induced spinal cord injury (SCI) in rats | ↑ neurons; anti-apoptotic effect; ↓ inflammation; ↓ expression of AQP-4; ↑ IL-10 | [97] |

| Crocin loaded in SLN (25, 50 mg/kg/day; orally taken for 28 days) | pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) induced oxidative damage | ↓ NO; ↑ CAT; ↑ memory; ↓ anxiety; ↓ Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-Κb) | [106] |

| Crocin (150, 300, and 600 nmol, intra-hippocampal (IH)) (5 mg/mL, i.p.) | amyloid β-induced memory deficit | ↑ spatial memory indicators; ↓ Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and cleaved Caspase-3 level; anti-apoptotic effect | [98] |

| saffron aqueous extract and crocin (15 mg twice daily, 12 weeks) | adult patients with schizophrenia | No serious side effects were observed; ↑ white blood cells | [107] |

| CSE (10, 15, and 20 mg/kg orally) | scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment, amyloid beta (Aβ) plaque, and neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) | AChE inhibition; ↓ Aβ plaque and NFT | [108] |

| Stigma of Crocus sativus | fly PD model overexpressing several mutant α-synuclein | ↑ life span; ameliorate retinal degeneration; ↑ climbing ability in the Drosophila | [109] |

| Crocin (10, 20, and 30 mg/kg orally) for weeks | Unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS) induced Depression and anxiety in rats | ↓ corticosterone, ↑ antioxidant defenses, ↓ oxidative damage, ↑ brain-derived neurotrophic factor | [91] |

| Safron (50 mg/kg) and crocin (30 mg/kg | weight drop model induced (rmTBI) | ↓ IFN-γ, TNF-α, MDA, and myeloperoxidase activity (MPO), ↑ GSH ↑ neurological, cognitive, motor, and sensorimotor functions. | [110] |

| Saffron extract (50 mg/kg, i.p.) for 5 days | Traumatic brain injury (TBI) in the Zebrafish model | anxiolytic effect, prevent fear; ↑ memory performance | [111] |

| Saffron capsule (15 mg/twice a day) for 12 weeks | Alzheimer’s Disease patients | ↓ IL-1β and MDA; ↑ total antioxidant capacity (TAC) | [100] |

| Safranal (100 mg/kg, 200 mg/kg, or 400 mg/kg) | (PTZ)-induced epileptic seizures in mice | ↓ seizure stage; ↓ hyperactivity of neurons; suppressed the NF-κB signaling pathway; ↓ TNF-α and IL-1β | [102] |

| Crocin (30 mg twice daily) | adult patients with Parkinson’s disease | Enhance daily life activities; attenuate movement disorders | [101] |

6.6. Anti-Obesity and Anti-Dyslipidemic Effects

6.7. Anti-Diabetic Effects

| Treatment | Methods of Analysis | Major Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saffron (40 and 80 mg/kg) | Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes in Rats | ↓ blood glucose levels, cholesterol, triglyceride, and LDL; ↑ HDL, SOD, CAT, and GSH; ↓ cognitive deficit | [37] |

| Saffron (120 mg/kg) for 60 days | Tartrazine-induced diabetic male rats | reduce blood glucose level and creatinine | [127] |

| Stigma extract (50 mg/kg) for 3 weeks | Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes in rats | ↓ blood glucose levels; ↓ total cholesterol and triglyceride; ↓ urea and creatinine; ↓ AST and ALT | [125] |

| Crocin (100 mg/kg, i.p.) for 2 weeks | streptozotocin-induced type-2 diabetic rats | ↑ serum insulin levels; ↑ (SOD, GSH, and CAT); improve fasting glucose levels | [126] |

| Crocin solution | Hyperglycemia. In Vivo Evidence from Zebrafish | ↓ embryo glucose levels; ↑ insulin expression; ↑ expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 (pck1) | [134] |

| saffron extract | In vitro alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase | high inhibitory activity against α-glucosidase and α-amylase | [135] |

| Saffron extract (84 mg for 6 months) | People with Diabetes Mellitus Type 1 | improves serum triglycerides | [132] |

| Crocin (150 mg/kg orally) 6 weeks | Streptozocin induced type-2 diabetes in rats | ↓ plasma TNF-α and IL-1β levels; ↓ pancreas tissue TNF-α and IFN-γ levels; ↓ inflammation and oxidative stress | [136] |

| Crocin (300 mg/kg in 1 mL PBS) for 8 weeks | Streptozocin induced type-2 diabetes in Sprague Dawley rats | ↓ fasting blood glucose levels, ↓ fat accumulation in the liver, alleviate renal fibrosis, and ↓ blood lipid levels | [128] |

| Saffron extract (0.2–1.2 mg/mL) (400 mg/kg orally) | In vitro inhibition tests of α-amylase and α-glucosidase In vivo Antihyperglycemic Activity in albino Wistar rats | ↓ postprandial hyperglycemia; inhibition activity against α-glucosidase and α-amylase | [129] |

| Crocetin | In vitro biochemical assay In silico | ↑ glucose uptake; GPR40/120 agonist; enhance insulin secretion | [130] |

| Saffron extract capsules twice a day (15 mg) for 8 weeks | A triple-blinded randomized clinical trial | ↓ fasting blood sugar | [133] |

| Crocin (50 mg/kg) for 8 weeks | In vivo investigation of the hypoglycemic effect in db/db mice | ↑ insulin and pyruvate kinase | [131] |

| Saffron extract (15, 200, and 250 mg/kg) for 8 weeks Safranal (15, 20, and 25 mg/kg) for 8 weeks | Alloxan-Induced Diabetes in rats | ↓ MDA; ↑ CAT and GSH; ↑ insulin; beta-cells regeneration | [137] |

6.8. Cardioprotective and Antihypertensive Effects

| Treatment | Methods of Analysis | Major Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crocin (50 or 10 mg/kg/day) for 1 week | Myocardial Infarction Using Sprague−Dawley rats | Lower arrhythmia score; ↑ expression of connexin 43 (Cx43) mRNA | [152] |

| Crocetin ester (25 and 50 mg/kg) for 14 days | isoproterenol (ISO)-induced acute myocardial ischemia | ↓ TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6; ↓ creatine kinase (CK) and MDA; ↑ SOD; improve histopathological alteration | [138] |

| Crocin (40 and 80 mg/kg/day i.p.) | Arsenic trioxide-induced cardiotoxicity in rats | ↓ ROS; ↑ SOD, GSH and GPx; ↓ MDA, gamma glutamyl transferase and proinflammatory cytokines; ↓ Caspase-3 and Bcl-2 | [148] |

| Crocin (100 and 200 mg/kg/day i.p.) for 14 days | Isoprenaline-induced myocardial fibrosis in mice | ↓ IL-6, IL-1, TNF-α and NF-κB, ↓ SOD and CAT; ↓ B cell lymphoma-2, Bcl-2-associated X protein, caspase-3, and cleaved caspase-3 expressions | [140] |

| Crocin (10 and 20 mg/kg, orally) for 3 weeks. | Doxorubicin-induced myocardial injury in rats | improve ECG profile; restore the balance between pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines; reduce Cardiac caspase-3 activity | [146] |

| Crocin (10, 20, and 40 µM) for 1 day | In vitro LPS-induced inflammation in cardiomyocytes | ↓ LPS toxicity (↓ TNF-α, PGE2, IL-β, and IL-6); ↑ thiols; ↓ nitric oxide | [142] |

| Crocin (20 and 40 mg/kg/24 h, for 20 days) | Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats | improved heart damage, structural changes in the myocardium, and ventricular function; it did not affect the in vitro antitumor activity of DOX | [147] |

| Crocin (3, 30, and 300 µM) | In vitro isolated rat cardiomyocytes | reduce Ca2+ flow into cardiomyocytes, resulting in negative inotropic effects on myocardial contractility | [153] |

| Safranal (0, 10, 20, 40, 80, 160, and 320 μM) | ISO-induced myocardial injury | ↓ myocardial apoptosis; downregulating the TNF signaling pathway | [141] |

| Crocin (12.5, 25, 50 mg/kg/day, i.p.) for 4 weeks | Diazinon induced cardiotoxicity | ↓ protein ubiquitylation in heart tissue; ↑ HIF-1α ubiquitylation | [151] |

| Saffron (5, 10, and 20 mg/kg/day orally) for 21 days | Isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity in rats | ↑ SOD, GSH, and CAT, ↓ MDA; ↓ left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; ↑ CK-MB and LDH | [139] |

| crocin (50 mg/kg, i.p.) | PM10-induced cardiotoxicity | Restore Hemodynamic parameters; ↓ MDA and xanthine oxidase XOX; ↑ CAT, SOD, and GPx | [149] |

| Safranal (10, 30 µM) | (H/R)-induced cardiomyocyte injury in H9c2 cardiac myoblasts | ↑ cells viability; ↓ ROS; ↓ CK-MB, LDH, MDA and intracellular Ca2; ↓ caspase-3Bax protein; ↑ Bcl-2 protein; ↑ PI3K/AKT/GSK3β. | [143] |

| Saffron extract (60 mg/kg/day orally) for 4 weeks | Ischemia-reperfusion induced myocardial injury in Wild Type and ApoE(-/-) mice | ↑ eNOS, p-Akt, p-ERK1/2, p-44/p-42 and p-GSK3b-Ser9; ↓ IL-6 and iNOS; ↓ MDA and 3-Nitrotyrosine NT; ↓ infractus size | [154] |

| Capsule of crocetin (10 mg) for 2 months | pilot, randomized, double-anonymized, placebo-controlled clinical trial | ↓ (h-FABP), cellular adhesion molecule 1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; ↑ HDL, ↓ systolic and diastolic blood pressure | [145] |

| Crocetin diamide derivatives (1, 0.2, and 0.04 μM) | In vitro hypoxia-induced injury in H9c2 cells | ↑ cell and mitochondrial viability; ↓ LDH | [155] |

| Crocin (5 and 7 mM) | Aluminum phosphide-induced cardiotoxicity in Human Cardiac Myocyte | ↓ Protein carbonyl and MDA; ↑ SOD and CAT | [150] |

| Safranal (10 μg/mL) | In vitro doxorubicin and ischemia–reperfusion induced cardiomyocyte injury | ↓ caspase-3 activity; restored contractile proteins expression; inhibited mitochondrial permeability transition pore | [144] |

| Safranal (0.075 and 0.025 mL/kg/day orally) for 9 days | Isoprenaline-induced myocardial ischemia in rats | ↓ CK, LDH, and MDA; ↑ SOD; ↓ intracellular calcium; improve heart morphology | [156] |

6.9. Hepatoprotective Effects

| Treatment | Methods of Analysis | Major Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crocin (25 and 50 mg/kg orally) | methotrexate-induced liver injury | ↓ MDA, NO, IL-1β, and d TNF-α; ↑ CAT, SOD, GSH, GPx | [158] |

| Crocin (20, 40, and 80 mg/kg orally) for 8 weeks | Carbone tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis | ↓ nuclear factor-kappa B, IL-6, TNF-α, transforming growth factor β, and α-smooth muscle actin; ↓ caspase 3/7; ↑ peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPAR-γ) | [159] |

| Crocin (30 mg/kg) for 14 days | Copper oxide nanoparticles induced hepatic disturbances | ↓ hepatic enzymes activities; ↓ inflammatory biomarkers; repair hepatic alteration | [167] |

| Crocin (10, 20, and 40 mg/kg i.p.) for 4 weeks | Ethanol toxicity in the rat | ↓ MDA; ↑ GSH; restore TNF-α and IL-6 levels; prevent apoptosis | [160] |

| Saffron extract (60 mg/kg i.p.) for 30 days | Copper Nanoparticles Induced hepatoxicity in mice | ↓ MDA, AST, ALT, and ALP; ↑ total antioxidant capacity; partial protection against necrotic cells | [168] |

| Saffron extract by the gastric tube | Silver Nanoparticles caused Hepatotoxicity | ↓ MDA, AST, ALT, and ALP; ↑ GSH | [169] |

| Crocetin (10, 30, and 50 mg/kg orally) | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in mice | ↓ AST, ALT, TC, TG, MDA, CR, UA; ↑ SOD and CAT; suppressed high-fat diet; ↓ TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β; ↑ HO-1 and Nrf2 | [165] |

| Crocin (20 mg/kg, orally) for 8 weeks | Leflunomide-induced liver injury | ↓ AST, ALT, ALP, hepatic MDA, nitrite, mTOR gene, PI3K gene, TGF-β; ↑ albumin, total protein, hepatic catalase, and GSH | [161] |

| Safranal (0.025, 0.05 and 0.1 mL/kg/day i.p.) for 14 days | acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats | ↓ MDA, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β; ↑ GSH, GPx and CAT; ↓ AST, ALT and ALP | [163] |

| Saffron phenolic-enriched fraction nanofibers loaded with C. sativus phenolic | cisplatin-induced hepatotoxicity in mice | ↑ weight; ↓ liver enzymes; ↑ GPx, SOD, CAT; ↓ iNOS and IFN-γ | [162] |

| Saffron, crocin, and safranal (100 mg/kg/day orally) for 7 days | CCL4-Induced Liver Damage | removed histological abnormalities, including necrosis, showing liver injury. | [170] |

| Saffron (150 and 300 mg/kg/day orally) for 28 days | acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity | ↓ AST, ALT, ALP, LDH; FXR up-regulation by saffron | [171] |

| Saffron (40 mg/kg/day orally) for 30 days | Oxymetholone-Induced Hepatic Injury in Rats | ↓ in hepatic degenerative changes | [166] |

| Saffron (80 mg/kg i.p.) 10 days | methotrexate-induced liver toxicity in rats | ↓ AST, ALT, ALP, and LDH; ↓ MDA and nitric oxide; ameliorate morphological alterations | [172] |

| Crocin (50 mg/kg/day orally), (100 µM–300 µM) | In Vivo & In Vitro hepatocellular Carcinoma | ↓ C-reactive protein CRP; IL-6; LDH ↓ TNFα, p53, VEGF and NF-κB; anti-tumor effect on HepG2 cells | [164] |

| Stigma extract (50 mg/kg/day) for 14 days | Carbon tetrachloride induced acute liver injury in rats | ↓ AST, ALT, ALP, LDH, creatinine, and MDA; prevent body loss. | [173] |

| Crocin (50, 100, and 250 mg/kg) | sepsis-induced injury in the liver, kidney, and lungs | ↓ IL-1b, TNF-a, IL-6 and IL-10; suppressed p38 MAPK phosphorylation, NF-jB/IjBa and Bcl-2/Bax activation |

6.10. Pulmonary Protective Effects

| Treatment | Methods of Analysis | Major Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crocin (30 and 60 mg/kg i.p.) | Ovalbumin-sensitized lung tissue in mice | ↓ inflammatory cells (eosinophils, neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes); ↓ Drp1, Pgc1α, and Nrf1 levels; ↑ Mfn2 | [174] |

| Crocin (60 mg/kg orally and 50 mg/kg i.p.) for 2 weeks | acrolein-induced lung injury in albino rats | i.p. crocin ↓ MDA, TNF-α, IL-6, Protein carbonyls, 8-hydroxydeoxy guanosine levels; ↑ GSH | [175] |

| Crocin (7.5, 10, 30 mg/kg) | monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension | ↑ Oxidation resistance 1 and P21 gene expression; ↑SOD, GPx, CAT, TAC | [176] |

| Crocin (25 mg/kg orally) for 28 days | Bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis | ↓ TNF-α, MDA, and NO in lungs; ↑ GSH, CAT, GPx | [177] |

| Crocin (30 and 60 mg/kg) | allergic airway inflammation | Prevent increase in white blood cell; ↓ NF-kB and IL-17; upregulating Nrf2/HO-1 mRNA | [53] |

| Crocin (50 mg/kg i.p.) for 9 days | LPS-induced acute lung injury | ↓ Hemorrhage, inhibition of the HMGB1/TLR4 pathway | [178] |

| Crocin (30 mg/day) for 12 weeks | A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial | ↓ TOS and NF-κB; ↑ total antioxidant capacity (TAOC); improvement in patients’ exercise capacity | [182] |

| Crocin (15 mg twice a day) for 12 weeks | A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-controlled trial | ↑ pulmonary function tests and walking distance test (6MWD); ↓ TNF-α | [60] |

| Crocin (25 μM) for 48 h | Oxidative stress induced by 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide | decline the injury; reduce inflammation and ROS production; ↑ cell survival | [179] |

| Safranal (1 and 10 mg/kg) (10 and 100 ng/mL) | In vivo mouse model of Asthma In vitro cytokines induced stress in bronchial epithelial cells | ↓ NO, iNOS levels, peroxynitrite ion generation and cytochrome c; ↓ airway hyper-responsiveness and airway cellular infiltration to the lungs; ↓ Th2 type cytokine | [180] |

| C. sativus extract (20 and 80 mg/kg/day) | Paraquat-induced lung inflammation in rats | ↑ IFN-γ, IL-10, SOD, CAT, thiol and EC50; ↓ BALF and MDA; ↓ total and differential WBC | [181] |

| Saffron extract (150 and 600 mg/kg/day orally) for 15 days | Paraquat-induced lung injuries | ↑ SOD, CAT, Thiols in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF); ↓ TNF-α, IL-10, and tracheal responsiveness | [183] |

| C. sativus extract (30 mg/kg and 60 mg/kg i.p.) for 28 days | Ovalbumin (OVA)-induced asthma in rats | ↓ Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid; ↓ total protein and albumin in serum, BALF, and lung tissues; ↓ TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-13 | [184] |

6.11. Gastrointestinal Protective Effects

| Treatment | Methods of Analysis | Major Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stigmas extract (0.3 to 10 mg/mL) | In Vitro Assessment of Myorelaxant and Antispasmodic Effects | Dose-dependent antispasmodic and myorelaxant activity; | [185] |

| crocin (7.5, 15, or 30 mg/kg, i.p.) | Indomethacin-induced gastric lesions in rats | ↓ caspase-3 levels and Inos protein expression; Decrease MDA levels and mucus content | [189] |

| Crocin (50 mg/kg/day, i.p.) for 3 days | Ethanol-induced gastric injury in rats | ↑ gastric juice mucin and mucosal prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), IL-6, TNF-α, myeloperoxidase activity; ↑ SOD and glutathione; ↓ caspase-3 activity and mitigated DNA fragmentation | [191] |

| Safranal (0.063, 0.25, and 1 mg/kg) for 7 days | Indomethacin-induced gastric ulcer | Ameliorate histological changes and tissue biochemical alterations (↑ SOD and TAC, ↓ MDA, TNF-α, and caspase-3); reduce gastric mucosa lesions. | [188] |

| crocin (2.50, 10.00 and 40.00 mg/kg i.p.) | Indomethacin induced intestinal ulcer. | Down-regulate intestine weight and organo-somatic index; (↑ SOD; ↓ caspase-3, TNF-α and MDA | [187] |

| Saffron extract (7.5, 15, 20 and 25 mg/kg orally) for 11 days | DSS induced Colitis in C57BL/6 mice | restore body weight, colon length, histology score; ↓ pro-inflammatory macrophages (M1); ↓ anti-inflammatory macrophages (M2) and IL-10 | [192] |

| Saffron extract (100 and 200 mg/kg orally) for 12 days | Acetic Acid-Induced Gastric Ulcer in male Wistar Rats | Reduce prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), ↓ MDA | [190] |

| Crocin (20 mg/kg orally) for 8 days | Acetic Acid-Induced Gastric Ulcer in male Sprague Dawley Rats | ↓ TNF-α, Ca2+ contents, LDH, CRP and Inflammatory cells; Enhance Nrf2 and HO-1 signaling and down-regulate caspase-3 activity; ↑ SOD, GSH and CAT; | [195] |

| Crocin (15 mg/kg, i.p.) for 30 min before induction of injury | Ischemia-reperfusion-induced gastric injury in rats | Decrease area of gastric lesions; ↓ caspase-3 and iNOS | [194] |

| Crocetin (100 and 200 mg/kg) | In vitro burn-induced intestinal injury | ↑ antioxidants enzymes; reduce inflammatory response (IL-6, TNF-α); improve intestinal permeability, and histological changes | [186] |

| Crocin (100 mg/kg/day orally) for 15 days | CCL-4 mediated oxidative stress in rats | Reduce histological lesions; ↓ TOS and MDA; ↑ GSH and TAS | [196] |

| Saffron aqueous extract (10 and 20 mg/kg orally) for 11 days | Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in mice | Suppress NF-κB (↓ TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6); regulate the composition of gut microbiota; diminishes the susceptibility to colitis reformulate | [197] |

| Crocin (50 mg/kg orally) for 21 days | Acrylamide induced small and large intestine damage in Wistar rats | ↑ GSH and TAS; ↓ MDA, TAS, SOD, and CAT; recover histological damage | [193] |

| Crocetin (10 and 40 mg/kg orally) for 21 days | DSS-Induced Colitis in mice | Promote inflammation, prolong recovery time from colitis, and disturb gut microbiota composition. | [198] |

| Safranal (8 and 16 mM) | DSS and Erwinia carotovora 15 (Ecc15) induced intestinal injury in Drosophila | maintain intestinal homeostasis; ↓ antimicrobial peptide (AMP) and ROS; increase the viability of intestinal epithelial cells | [199] |

| Saffron (50 mg twice daily) for 8 weeks | Open-label, single-center pilot clinical trial | Reduce abdominal pain, diarrhea and rectal bleeding; ↑ IL-10, ↓ TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-2, IL-17A | [200] |

6.12. Effects on the Reproductive System

6.13. Protection Against Skin Diseases

6.14. Bone Regenerative Effects

| Treatment | Methods of Analysis | Major Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crocin/crocetin (12.5, 25, 50 µM) | In vitro osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells | Improve bone regeneration by increasing the number of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) mediated osteoblasts | [222] |

| Crocin (40 and 80 µM) | Titanium particles induce inflammation and promote osteogenesis | Downregulate Ti particle-induced inflammation by production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (anti-inflammatory (M2) macrophage polarization); improve osteogenic differentiation | [223] |

| Crocin (10, 20 and 40 mg/kg orally) for 14 days (10, 25 and 50 μmol/L) | In vitro human BMSCs In vivo steroid-induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head | ↑ alkaline phosphatase and calcium nodules; Ameliorate osteonecrosis; ↑ expression levels of RUNX2, COL1A1, and OCN in hBMSCs and femoral head tissues; ↓ GSK-3β phosphorylation | [224] |

| Crocin and bicarbonate de sodium (500 + 80 µg) | Human fetal osteoblast (hFOB) and human osteosarcoma (MG-63) cells; In vivo rat distal femur defects study | Intensify osteoblast proliferation; reduce human osteosarcoma (MG-63) viability by 50%; pro-apoptotic mechanism against osteosarcoma | [229] |

| Crocin (50, 100, 250 and 500 µM) | AlCl3 induced cytotoxicity in rat Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells | ↑ mRNA expression of Sox-2 and E-cadherin | [227] |

| Saffron (800 µg/mL) + Pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMFs) | In vitro osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells | ↓ dose-dependently, the cell viability, ↑ ALP activity, and synergic effect of saffron and PEMPs on osteogenesis at the initial stage | [225] |

| Crocin (2.5–5 µM) + nanocurcumin (0.3 and 0.7 µM) | In vitro osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells | Help MSCs proliferate and protect them from apoptosis; increase the expression of OCT4 and SOX2 genes | [230] |

| Crocin (2–10 µM) (20–100 mg/mL) | Methylglyoxal-induced osteoclasts in RAW264.7 cell lines | ↓ osteoclast function and differentiation and bone resorption; ↓gene expression levels of TRAF6, Akt2, ERK1, OSTM1, and MMP-9; ↓bone resorption activity of osteoclasts | [226] |

| Crocin (5 or 10 mg/kg orally) for 12 weeks | Metabolic syndrome-induced osteoporosis in rats | ↓ tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase and C-terminal telopeptide and TNF-α and IL-6 oxidative stress; protect from histological change in bone; ↑ serum alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin | [228] |

6.15. Nephroprotective Effects

7. Toxicity of Saffron

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- de Araújo, F.F.; de Paulo Farias, D.; Neri-Numa, I.A.; Pastore, G.M. Polyphenols and Their Applications: An Approach in Food Chemistry and Innovation Potential. Food Chem. 2021, 338, 127535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Anil Kumar, N.V.; Zucca, P.; Varoni, E.M.; Dini, L.; Panzarini, E.; Rajkovic, J.; Tsouh Fokou, P.V.; Azzini, E.; Peluso, I. Lifestyle, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Back and Forth in the Pathophysiology of Chronic Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Pop, A.; Iordache, F.; Stanca, L.; Predoi, G.; Serban, A.I. Oxidative Stress Mitigation by Antioxidants-an Overview on Their Chemistry and Influences on Health Status. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 209, 112891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishi, S.; Nagasu, H.; Kidokoro, K.; Kashihara, N. Oxidative Stress and the Role of Redox Signalling in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Several Lines of Antioxidant Defense against Oxidative Stress: Antioxidant Enzymes, Nanomaterials with Multiple Enzyme-Mimicking Activities, and Low-Molecular-Weight Antioxidants. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nani, A.; Murtaza, B.; Sayed Khan, A.; Khan, N.A.; Hichami, A. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Polyphenols Contained in Mediterranean Diet in Obesity: Molecular Mechanisms. Molecules 2021, 26, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, S.; Harnafi, M.; Touiss, I.; Bekkouch, O.; Milenkovic, D.; Amrani, S.; Harnafi, H. HPLC–DAD Profiling of a Phenolic Extract from Moroccan Sweet Basil and Its Application as Oxidative Stabilizer of Sunflower Oil. Chem. Pap. 2021, 75, 1907–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, T.; Aires, A.; Cosme, F.; Bacelar, E.; Morais, M.C.; Oliveira, I.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.; Anjos, R.; Vilela, A.; Gonçalves, B. Bioactive (Poly) Phenols, Volatile Compounds from Vegetables, Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Foods 2021, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, M.; Fuentes, E.; Ávila, F.; Alarcón, M.; Palomo, I. Roles of Phenolic Compounds in the Reduction of Risk Factors of Cardiovascular Diseases. Molecules 2019, 24, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardone, L.; Castronuovo, D.; Perniola, M.; Cicco, N.; Candido, V. Saffron (Crocus sativus L.), the King of Spices: An Overview. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 272, 109560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José Bagur, M.; Alonso Salinas, G.L.; Jiménez-Monreal, A.M.; Chaouqi, S.; Llorens, S.; Martínez-Tomé, M.; Alonso, G.L. Saffron: An Old Medicinal Plant and a Potential Novel Functional Food. Molecules 2017, 23, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.-C.; Nabil, W.N.N.; Xu, H.-X. The History of Saffron in China: From Its Origin to Applications. Chin. Med. Cult. 2021, 4, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.M.; Turhan, S. The Importance of Saffron Plant in Afghanistan’s Agriculture. J. Biol. Environ. Sci. 2017, 11, 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Leone, S.; Recinella, L.; Chiavaroli, A.; Orlando, G.; Ferrante, C.; Leporini, L.; Brunetti, L.; Menghini, L. Phytotherapic Use of the Crocus sativus L. (Saffron) and Its Potential Applications: A Brief Overview. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 2364–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi-Shahandashti, S.-S.; Mann, L.; El-Nagish, A.; Harpke, D.; Nemati, Z.; Usadel, B.; Heitkam, T. Ancient Artworks and Crocus Genetics Both Support Saffron’s Origin in Early Greece. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 834416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, S.A.; Ashraf, N. Apocarotenoids of Crocus sativus L.: From Biosynthesis to Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; ISBN 981-10-1899-5. [Google Scholar]

- Dhar, M.K.; Sharma, M.; Bhat, A.; Chrungoo, N.K.; Kaul, S. Functional Genomics of Apocarotenoids in Saffron: Insights from Chemistry, Molecular Biology and Therapeutic Applications. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2017, 16, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torricelli, R.; Javan, I.Y.; Albertini, E.; Venanzoni, R.; Hosseinzadeh, Y. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Italian, Iranian and Spanish Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) Accessions. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 1875–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Sosa, R.; Nevárez-Moorillón, G.V.; Ochoa-Velasco, C.E.; Navarro-Cruz, A.R.; Hernández-Carranza, P.; Cid-Pérez, T.S. Detection of Saffron’s Main Bioactive Compounds and Their Relationship with Commercial Quality. Foods 2022, 11, 3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lage, M.; Cantrell, C.L. Quantification of Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) Metabolites Crocins, Picrocrocin and Safranal for Quality Determination of the Spice Grown under Different Environmental Moroccan Conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2009, 121, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Diaz, J.; Sánchez, A.M.; Martinez-Tome, M.; Winterhalter, P.; Alonso, G.L. A Contribution to Nutritional Studies on Crocus sativus Flowers and Their Value as Food. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2013, 31, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzabri, I.; Addi, M.; Berrichi, A. Traditional and Modern Uses of Saffron (Crocus sativus). Cosmetics 2019, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizad, S.; Dizadji, A.; Habibi, M.K.; Winter, S.; Kalantari, S.; Movi, S.; Tendero, C.L.; Alonso, G.L.; Moratalla-Lopez, N. The Effects of Geographical Origin and Virus Infection on the Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) Quality. Food Chem. 2019, 295, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadavi, R.; Jafari, S.M.; Katouzian, I. Nanoliposomal Encapsulation of Saffron Bioactive Compounds; Characterization and Optimization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 4046–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenger, T. History of Saffron. Longhua Chin. Med. 2022, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.Z.; Bathaie, S.Z. Historical Uses of Saffron: Identifying Potential New Avenues for Modern Research. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2011, 1, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Asgari, M.; Yu, Q.; Abdi, M.; Du, G.-L.; Shen, Y.-H. Survey of the History and Applications of Saffron. Chin. Med. Cult. 2022, 5, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basker, D.; Negbi, M. Uses of Saffron. Econ. Bot 1983, 37, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, P. Secrets of Saffron: The Vagabond Life of the World’s Most Seductive Spice; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; ISBN 0-8070-5009-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dalby, A. Dangerous Tastes: The Story of Spices; Univ of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2000; ISBN 0-520-23674-2. [Google Scholar]

- El Midaoui, A.; Ghzaiel, I.; Vervandier-Fasseur, D.; Ksila, M.; Zarrouk, A.; Nury, T.; Khallouki, F.; El Hessni, A.; Ibrahimi, S.O.; Latruffe, N. Saffron (Crocus sativus L.): A Source of Nutrients for Health and for the Treatment of Neuropsychiatric and Age-Related Diseases. Nutrients 2022, 14, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravask. Saffron Crocus sativus Modern World Production. 2006. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Saffron_crocus_sativus_modern_world_production.png (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Bathaie, S.Z.; Farajzade, A.; Hoshyar, R. A Review of the Chemistry and Uses of Crocins and Crocetin, the Carotenoid Natural Dyes in Saffron, with Particular Emphasis on Applications as Colorants Including Their Use as Biological Stains. Biotech. Histochem. 2014, 89, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrone, G.; Urciuoli, S.; Di Lauro, M.; Cornali, K.; Montalto, G.; Masci, C.; Vanni, G.; Tesauro, M.; Vignolini, P.; Noce, A. Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) and Its by-Products: Healthy Effects in Internal Medicine. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M.; Sánchez, A.M.; Ferreres, F.; Zalacain, A.; Tomás-Barberán, F.; Alonso, G.L. Identification of the Flavonoid Fraction in Saffron Spice by LC/DAD/MS/MS: Comparative Study of Samples from Different Geographical Origins. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahi, T.; Assadpour, E.; Jafari, S.M. Main Chemical Compounds and Pharmacological Activities of Stigmas and Tepals of ‘Red Gold’; Saffron. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 58, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarghandian, S.; Azimi-Nezhad, M.; Samini, F. Ameliorative Effect of Saffron Aqueous Extract on Hyperglycemia, Hyperlipidemia, and Oxidative Stress on Diabetic Encephalopathy in Streptozotocin Induced Experimental Diabetes Mellitus. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 920857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou, E.; Kadoglou, N.P.; Kostomitsopoulos, N.; Valsami, G. Saffron: A Natural Product with Potential Pharmaceutical Applications. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 67, 1634–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrazem, O.; Rubio-Moraga, A.; Nebauer, S.G.; Molina, R.V.; Gomez-Gomez, L. Saffron: Its Phytochemistry, Developmental Processes, and Biotechnological Prospects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 8751–8764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarghandian, S.; Borji, A. Anticarcinogenic Effect of Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) and Its Ingredients. Pharmacogn. Res. 2014, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, L.; Carmona, M.; Zalacain, A.; Kanakis, C.D.; Anastasaki, E.; Tarantilis, P.A.; Polissiou, M.G.; Alonso, G.L. Changes in Saffron Volatile Profile According to Its Storage Time. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1329–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda-Bernad, D.; Valero-Cases, E.; Pastor, J.-J.; Frutos, M.J. Saffron Bioactives Crocin, Crocetin and Safranal: Effect on Oxidative Stress and Mechanisms of Action. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 3232–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkouch, O.; Bekkouch, A.; Elbouny, H.; Touiss, I.; Assri, S.E.; Choukri, M.; Bourhia, M.; Kim, K.; Kang, S.; Choi, M. Combinatorial Effects of Zingiber Officinale and Citrus Limon Juices: Hypolipidemic and Antioxidant Insights from in Vivo, in Vitro, and in Silico Investigations. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouahhoud, S.; Khoulati, A.; Kadda, S.; Bencheikh, N.; Mamri, S.; Ziani, A.; Baddaoui, S.; Eddabbeh, F.-E.; Lahmass, I.; Benabbes, R. Antioxidant Activity, Metal Chelating Ability and DNA Protective Effect of the Hydroethanolic Extracts of Crocus sativus Stigmas, Tepals and Leaves. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaha, H.; Chahine, N.; Sobolev, A.P.; Menghini, L.; Makhlouf, H. 1H-NMR Metabolic Profiling and Antioxidant Activity of Saffron (Crocus sativus) Cultivated in Lebanon. Molecules 2021, 26, 4906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglio, R.; Gentile, C.; Bonanno, A.; Vintaloro, L.; Perrone, A.; Mazza, F.; Barbaccia, P.; Settanni, L.; Di Grigoli, A. Effect of Saffron Addition on the Microbiological, Physicochemical, Antioxidant and Sensory Characteristics of Yoghurt. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2019, 72, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menghini, L.; Leporini, L.; Vecchiotti, G.; Locatelli, M.; Carradori, S.; Ferrante, C.; Zengin, G.; Recinella, L.; Chiavaroli, A.; Leone, S. Crocus sativus L. Stigmas and Byproducts: Qualitative Fingerprint, Antioxidant Potentials and Enzyme Inhibitory Activities. Food Res. Int. 2018, 109, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hariri, A.T.; Moallem, S.A.; Mahmoudi, M.; Memar, B.; Razavi, B.M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Effect of Crocus sativus L. Stigma (Saffron) against Subacute Effect of Diazinon: Histopathological, Hematological, Biochemical and Genotoxicity Evaluations in Rats. J. Pharmacopunct. 2018, 21, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Q.; Xiong, Z.; Yu, C.; Zhou, J.; Shen, Q.; Wang, L.; Xie, X.; Fu, Z. Antidepressant Activity of Crocin-I Is Associated with Amelioration of Neuroinflammation and Attenuates Oxidative Damage Induced by Corticosterone in Mice. Physiol. Behav. 2019, 212, 112699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudarzi, S.; Jafari, M.; Pirzad Jahromi, G.; Eshrati, R.; Asadollahi, M.; Nikdokht, P. Evaluation of Modulatory Effects of Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) Aqueous Extract on Oxidative Stress in Ischemic Stroke Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahvilian, N.; Masoodi, M.; Faghihi Kashani, A.; Vafa, M.; Aryaeian, N.; Heydarian, A.; Hosseini, A.; Moradi, N.; Farsi, F. Effects of Saffron Supplementation on Oxidative/Antioxidant Status and Severity of Disease in Ulcerative Colitis Patients: A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinali, M.; Zirak, M.R.; Rezaee, S.A.; Karimi, G.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Immunoregulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Crocus sativus (Saffron) and Its Main Active Constituents: A Review. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2019, 22, 334. [Google Scholar]

- Jeddi, F.; Zahertar, S.; Bordbar, A.; Salimnejad, R.; Ghobadi, H.; Aslani, M.R. Crocin from Saffron Ameliorates Allergic Airway Inflammation through NF-κB, IL-17, and Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling Pathways in Mice. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2024, 27, 1624. [Google Scholar]

- Samarghandian, S.; Azimi-Nezhad, M.; Farkhondeh, T. Immunomodulatory and Antioxidant Effects of Saffron Aqueous Extract (Crocus sativus L.) on Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes in Rats. Indian Heart J. 2017, 69, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosri, H.; Elkashef, W.F.; Said, E.; Gameil, N.M. Crocin Modulates IL-4/IL-13 Signaling and Ameliorates Experimentally Induced Allergic Airway Asthma in a Murine Model. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 50, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Song, R.; Cao, Y.; Yan, X.; Gao, H.; Lian, F. Crocin Mitigates Atherosclerotic Progression in LDLR Knockout Mice by Hepatic Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Reaction Reduction, and Intestinal Barrier Improvement and Gut Microbiota Modulation. J. Funct. Foods. 2022, 96, 105221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lei, H.; Cao, L.; Mi, Y.-N.; Li, S.; Cao, Y.-X. Crocin Alleviates Coronary Atherosclerosis via Inhibiting Lipid Synthesis and Inducing M2 Macrophage Polarization. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 55, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Li, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhao, J. Crocin Exerts Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Catabolic Effects on Rat Intervertebral Discs by Suppressing the Activation of JNK. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrastina, M.; Dráfi, F.; Pružinská, K.; Poništ, S.; Kamga, K.S.; Khademnematolahi, S.; Bilka, F.; Novák, P.; Pašková, Ľ.; Bauerová, K. Crocus sativus L. Extract (Saffron) Effectively Reduces Arthritic and Inflammatory Parameters in Monotherapy and in Combination with Methotrexate in Adjuvant Arthritis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslani, M.R.; Abdollahi, N.; Matin, S.; Zakeri, A.; Ghobadi, H. Effect of Crocin of Crocus sativus L. on Serum Inflammatory Markers (IL-6 and TNF-α) in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 130, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi-Zanjani, B.; Balali-Mood, M.; Mohammadi, E.; Badie-Bostan, H.; Memar, B.; Karimi, G. Safranal as a Safe Compound to Mice Immune System. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2015, 5, 441. [Google Scholar]

- Farahani, M.H.; Zandieh, M.A.; Torkan, S. The Effects of Crocin from Red Saffron Flower on the Innate and Humoral Immune Systems of Domestic Short Hair Cats: Crocin Supplementation and Immunity of Cats. Lett. Anim. Biol. 2025, 5, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, F.; Arab, F.L.; Rastin, M.; Tabasi, N.S.; Nikkhah, K.; Mahmoudi, M. Comparative Assessment of Immunomodulatory, Proliferative, and Antioxidant Activities of Crocin and Crocetin on Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 122, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolba, H.A.; Aldawek, A.M.; Eid, R.A.; Aladdin, S.; El-Shaer, N.H. Immune Response and Bacterial Resistance of Oreochromis Niloticus against Bacterial Fish Pathogen with Saffron Diet. Open Vet. J. 2024, 14, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanizadeh, S.; Alikiaii, B.; Rouhani, M.H.; Talebi, S.; Mokhtari, Z.; Sharma, M.; Bagherniya, M. The Effects of Saffron Supplementation on Inflammation and Hematological Parameters in Patients with Sepsis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutr. J. 2025, 24, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatziagapiou, K.; Nikola, O.; Marka, S.; Koniari, E.; Kakouri, E.; Zografaki, M.-E.; Mavrikou, S.S.; Kanakis, C.; Flemetakis, E.; Chrousos, G.P. An in Vitro Study of Saffron Carotenoids: The Effect of Crocin Extracts and Dimethylcrocetin on Cancer Cell Lines. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Gu, M.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Peng, J.; Zhang, Y. Anticancer Activity of Crocin against Cervical Carcinoma (HeLa Cells): Bioassessment and Toxicity Evaluation of Crocin in Male Albino Rats. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2018, 180, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, J.; Cui, H.; Liu, S. Anticancer Activity of Safranal against Colon Carcinoma Is Due to Induction of Apoptosis and G2/M Cell Cycle Arrest Mediated by Suppression of mTOR/PI3K/Akt Pathway. Off. J. Balk. Union Oncol. 2018, 23, 574–578. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, P.H.; Elshamy, I.S.; Azmaa, N.E.A. Anticancer Effect of Combined Cinnamon–Saffron versus Its Nanoparticles on Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cell Line. Tanta Dent. J. 2024, 21, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hire, R.R.; Srivastava, S.; Davis, M.B.; Kumar Konreddy, A.; Panda, D. Antiproliferative Activity of Crocin Involves Targeting of Microtubules in Breast Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakshi, H.A.; Hakkim, F.L.; Sam, S.; Al-Buloshi, M. Assessment of in Vitro Cytotoxicity of Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) on Cervical Cancer Cells (HEp-2) and Their in Vivo Pre-Clinical Toxicity in Normal Swiss Albino Mice. Int. J. Herb. Med. 2016, 4, 80–83. [Google Scholar]

- Khavari, A.; Bolhassani, A.; Alizadeh, F.; Bathaie, S.Z.; Balaram, P.; Agi, E.; Vahabpour, R. Chemo-Immunotherapy Using Saffron and Its Ingredients Followed by E7-NT (Gp96) DNA Vaccine Generates Different Anti-Tumor Effects against Tumors Expressing the E7 Protein of Human Papillomavirus. Arch. Virol. 2015, 160, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Gao, J.; Niu, J.; Huang, Y.-F.; Chen, M.; Wang, M.-Z.; Shang, Q.; Lu, W.-Q.; Peng, L.-H.; Jiang, Z.-H. Synthesis, Characterization and Inhibitory Effects of Crocetin Derivative Compounds in Cancer and Inflammation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 98, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vago, R.; Trevisani, F.; Vignolini, P.; Vita, C.; Fiorio, F.; Campo, M.; Ieri, F.; Di Marco, F.; Salonia, A.; Romani, A. Evaluation of Anti-Cancer Potential of Saffron Extracts against Kidney and Bladder Cancer Cells. Food Biosci. 2024, 57, 103501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Hearn, K.; Parry, C.; Rashid, M.; Brim, H.; Ashktorab, H.; Kwabi-Addo, B. Mechanism of Antitumor Effects of Saffron in Human Prostate Cancer Cells. Nutrients 2023, 16, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Li, S.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wu, T.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Fu, S.; Wang, Z. Saffron Improves the Efficacy of Immunotherapy for Colorectal Cancer through the IL-17 Signaling Pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 337, 118854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbaszadegan, S.; Hosseinzadeh, H.; Alavizadeh, S.H.; Moghri, M.; Abbasi, A.; Jaafari, M.R. Anti-Tumor Activity of Nanoliposomes Containing Crude Extract of Saffron in Mice Bearing C26 Colon Carcinoma. Nanomed. J. 2021, 8, 290–297. [Google Scholar]

- Gezici, S. Comparative Anticancer Activity Analysis of Saffron Extracts and a Principle Component, Crocetin for Prevention and Treatment of Human Malignancies. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 5435–5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashrafi, M.; Bathaie, S.Z.; Abroun, S.; Azizian, M. Effect of Crocin on Cell Cycle Regulators in N-Nitroso-N-Methylurea-Induced Breast Cancer in Rats. DNA Cell Biol. 2015, 34, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabini, R.; Ehtesham-Gharaee, M.; Dalirsani, Z.; Mosaffa, F.; Delavarian, Z.; Behravan, J. Evaluation of the Cytotoxic Activity of Crocin and Safranal, Constituents of Saffron, in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (KB Cell Line). Nutr. Cancer 2017, 69, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhlouf, H.; Diab-Assaf, M.; Alghabsha, M.; Tannoury, M.; Chahine, R.; Saab, A.M. In Vitro Antiproliferative Activity of Saffron Extracts against Human Acute Lymphoblastic T-Cell Human Leukemia. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. 2016, 15, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mir, M.A.; Ganai, S.A.; Mansoor, S.; Jan, S.; Mani, P.; Masoodi, K.Z.; Amin, H.; Rehman, M.U.; Ahmad, P. Isolation, Purification and Characterization of Naturally Derived Crocetin Beta-d-Glucosyl Ester from Crocus sativus L. against Breast Cancer and Its Binding Chemistry with ER-Alpha/HDAC2. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 975–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Farrukh, A.; Murali, C.; Soleimani, A.; Praz, F.; Graziani, G.; Brim, H.; Ashktorab, H. Saffron and Its Major Ingredients’ Effect on Colon Cancer Cells with Mismatch Repair Deficiency and Microsatellite Instability. Molecules 2021, 26, 3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, F.; Ramezani, M.; Amel Farzad, S.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Hashemi, M. Comparison Study of the Effect of Alkyl-Modified and Unmodified PAMAM and PPI Dendrimers on Solubility and Antitumor Activity of Crocetin. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2017, 45, 1356–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafezi Ghahestani, Z.; Alebooye Langroodi, F.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Ramezani, M.; Hashemi, M. Evaluation of Anti-Cancer Activity of PLGA Nanoparticles Containing Crocetin. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2017, 45, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Hu, J.; Weng, J.; Liu, S.; Yin, L.; Long, L.; Tong, Y.; Tang, K.; Bai, S. Fabrication of Bimetallic Ag@ ZnO Nanocomposite and Its Anti-Cancer Activity on Cervical Cancer via Impeding PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2024, 84, 127437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahaiee, S.; Hashemi, M.; Shojaosadati, S.A.; Moini, S.; Razavi, S.H. Nanoparticles Based on Crocin Loaded Chitosan-Alginate Biopolymers: Antioxidant Activities, Bioavailability and Anticancer Properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 99, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamadian, M.; Mostafaei, A.; Rahimi-Danesh, M.; Zargar, M.; Erfani, H.; Sirouskabiri, S.; Vaseghi, S. Crocin Facilitates the Effect of Fear Extinction on Freezing Behavior and BDNF Level in a Rat Model of Fear-Conditioning. Learn. Motiv. 2025, 89, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, H.; Mohamadian, M.; Azizi, P.; Ghasemi, P.; Karimi, M.; Layegh, T.; Rahmatkhah-Yazdi, M.; Vaseghi, S. Crocin Has a Greater Therapeutic Role in the Restoration of Behavioral Impairments Caused by Maternal Social Isolation in Adolescent than in Adult Offspring Probably through GSK-3beta Downregulation. Learn. Motiv. 2024, 88, 102060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.; Shaheen, M.; Borjac, J. Crocin Suppresses Inflammation-Induced Apoptosis in rmTBI Mouse Model via Modulation of Nrf2 Transcriptional Activity. PharmaNutrition 2022, 21, 100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaszade-Cheragheali, A.; Beheshti, F.; Kakhki, S.; Khatibi, S.R.; Dehnokhalaji, F.; Akbari, E.; Fathi, H.; Farimani, S.S. Crocin, the Main Active Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) Constituent, as a Potential Candidate to Prevent Anxiety and Depressive-like Behaviors Induced by Unpredictable Chronic Mild Stress. Neurosci. Lett. 2022, 791, 136912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamegart, L.; Abbaoui, A.; Makbal, R.; Zroudi, M.; Bouizgarne, B.; Bouyatas, M.M.; Gamrani, H. Crocus sativus Restores Dopaminergic and Noradrenergic Damages Induced by Lead in Meriones Shawi: A Possible Link with Parkinson’s Disease. Acta Histochem. 2019, 121, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.V.; Yenisetti, S.C.; Rajini, P.S. Evidence of Neuroprotective Effects of Saffron and Crocin in a Drosophila Model of Parkinsonism. Neurotoxicology 2016, 52, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, R.M.; Abdel-Latif, G.A.; Abbas, S.S.; Hekmat, M.; Schaalan, M.F. Neuroprotective Effect of Crocin against Rotenone-Induced Parkinson’s Disease in Rats: Interplay between PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway and Enhanced Expression of miRNA-7 and miRNA-221. Neuropharmacology 2020, 164, 107900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, R.F.; El Awdan, S.A.; Hegazy, R.R.; Mansour, D.F.; Ogaly, H.; Abdelbaset, M. Neuroprotective Effect of Crocus sativus against Cerebral Ischemia in Rats. Metab. Brain Dis. 2020, 35, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forouzanfar, F.; Sadeghnia, H.R.; Hosseinzadeh, H.; Khorrami, M.B.; Shaterzadeh, H. P18: Neuroprotective Effect of Safranal, an Active Ingredient of Crocus sativus, in a Rat Model of Transient Cerebral Ischemia. Neurosci. J. Shefaye Khatam 2018, 6, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Ma, J.; Fan, L.; Zou, Y.; Dang, X.; Wang, K.; Song, J. Neuroprotective Effects of Safranal in a Rat Model of Traumatic Injury to the Spinal Cord by Anti-Apoptotic, Anti-Inflammatory and Edema-Attenuating. Tissue Cell 2015, 47, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadi, F.; Jamshidi, A.H.; Khodagholi, F.; Yans, A.; Azimi, L.; Faizi, M.; Vali, L.; Abdollahi, M.; Ghahremani, M.H.; Sharifzadeh, M. Reversal Effects of Crocin on Amyloid β-Induced Memory Deficit: Modification of Autophagy or Apoptosis Markers. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2015, 139, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozorgi, H.; Ghahremanfard, F.; Motaghi, E.; Zamaemifard, M.; Zamani, M.; Izadi, A. Effectiveness of Crocin of Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) against Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 281, 114511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzabadi, L.R.; Fazljou, S.M.B.; Araj-Khodaei, M.; Sadigh-Eteghad, S.; Naseri, A.; Talebi, M. Saffron Reduces Some Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Markers in Donepezil-Treated Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease Patients: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Control Trial. J. Herb. Med. 2022, 34, 100574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, S.M.; Assarzadegan, F.; Habibi, S.A.H.; Mahboubi, A.; Esmaily, H. The Effect of Crocin on Movement Disorders and Oxidative DNA Damage in Parkinson’s Disease: Insights from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Park. Relat. Disord. 2024, 126, 107051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Li, T.; Ji, K.; Zhou, X.; Yao, W.; Zhou, L.; Huang, P.; Zhong, K. Safranal Alleviates Pentetrazole-Induced Epileptic Seizures in Mice by Inhibiting the NF-κB Signaling Pathway and Mitochondrial-Dependent Apoptosis through GSK-3β Inactivation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 333, 118408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, G. Crocin Protects PC12 Cells against MPP+-Induced Injury through Inhibition of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and ER Stress. Neurochem. Int. 2015, 89, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Albarral, J.A.; Ramírez, A.I.; de Hoz, R.; López-Villarín, N.; Salobrar-García, E.; López-Cuenca, I.; Licastro, E.; Inarejos-García, A.M.; Almodóvar, P.; Pinazo-Durán, M.D. Neuroprotective and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of a Hydrophilic Saffron Extract in a Model of Glaucoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, L.; Rao, W.; Su, N.; Hui, H.; Wang, L.; Peng, C.; Tu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Fei, Z. Neuroprotective Effects of Crocin against Traumatic Brain Injury in Mice: Involvement of Notch Signaling Pathway. Neurosci. Lett. 2015, 591, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, C.; Gholami, M.; Kakebaraei, S. Protective Effect of Crocin-Loaded Nanoparticles in Rats Following Epileptic Seizures: Biochemical, Behavioral and Histopathological Outcomes. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, B.; Bathaie, S.Z.; Fadai, F.; Ashtari, Z.; Farhang, S.; Hashempour, S.; Shahhamzei, N.; Heidarzadeh, H. Safety Evaluation of Saffron Stigma (Crocus sativus L.) Aqueous Extract and Crocin in Patients with Schizophrenia. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2015, 5, 413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patel, K.S.; Dharamsi, A.; Priya, M.; Jain, S.; Mandal, V.; Girme, A.; Modi, S.J.; Hingorani, L. Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) Extract Attenuates Chronic Scopolamine-Induced Cognitive Impairment, Amyloid Beta, and Neurofibrillary Tangles Accumulation in Rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 326, 117898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, E.; Suzuki, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Sudo, K.; Kawasaki, H.; Ishida, N. Saffron Ameliorated Motor Symptoms, Short Life Span and Retinal Degeneration in Parkinson’s Disease Fly Models. Gene 2021, 799, 145811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, M.; Shaheen, M.; Tabbara, A.; Borjac, J. Saffron Extract and Crocin Exert Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidative Effects in a Repetitive Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Mouse Model. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaoul, V.; Awad, M.; Harb, F.; Najjar, F.; Hamade, A.; Nabout, R.; Soueid, J. Saffron Extract Attenuates Anxiogenic Effect and Improves Cognitive Behavior in an Adult Zebrafish Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jaberi, F.M.; Alhawarri, M.B.; Dewa, A.; Zainal, Z.; Zakaria, F. Anti-Obesity, Phytochemical Profiling and Acute Toxicity Study of Ethanolic Extract of Saffron (Crocus sativus L.). Pharmacol. Res.-Mod. Chin. Med. 2024, 11, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashmoul, M.; Azlan, A.; Mohtarrudin, N.; Yusof, B.N.M.; Khaza’ai, H. Saffron Extract and Crocin Reduced Biomarkers Associated with Obesity in Rats Fed a High-Fat Diet. Malays. J. Nutr. 2017, 23, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Zhang, M.; Sun, L.; Wang, T.; Zhu, Z.; Shu, R.; Wu, F.; Li, Z. Crocin-I Protects against High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity via Modulation of Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Inflammation in Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 894089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, R.; Aryaeian, N.; Hajiluian, G.; Soleimani, M.; Barati, M. The Effect of the Saffron Intervention on NAFLD Status and Related Gene Expression in a Rat Model. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2023, 37, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohaqiq, Z.; Moossavi, M.; Hemmati, M.; Kazemi, T.; Mehrpour, O. Antioxidant Properties of Saffron Stigma and Petals: A Potential Therapeutic Approach for Insulin Resistance through an Insulin-Sensitizing Adipocytokine in High-Calorie Diet Rats. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 11, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gul, T.; Balkhi, H.M.; Haq, E. Inhibition of Adipocyte Differentiation by Crocin in in Vitro Model of Obesity. Saudi J. Life Sci. 2017, 2, 306–311. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, F.; Emami, S.A.; Javadi, B.; Salmasi, Z.; Tayarani-Najjaran, M.; Tayarani-Najaran, Z. Inhibitory Effect of Saffron, Crocin, Crocetin, and Safranal against Adipocyte Differentiation in Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 294, 115340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, M.; Luo, L.; Fang, K. Crocin Inhibits Obesity via AMPK-Dependent Inhibition of Adipocyte Differentiation and Promotion of Lipolysis. Biosci. Trends 2018, 12, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedimanesh, N.; Bathaie, S.Z.; Abedimanesh, S.; Motlagh, B.; Separham, A.; Ostadrahimi, A. Saffron and Crocin Improved Appetite, Dietary Intakes and Body Composition in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Res. 2017, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, F.N.; Abu Bakar Sajak, A.; Abas, F.; Mat Daud, Z.A.; Azlan, A. Effect of Saffron Extract and Crocin in Serum Metabolites of Induced Obesity Rats. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1247946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Gu, M. Crocin Improves Insulin Sensitivity and Ameliorates Adiposity by Regulating AMPK-CDK5-PPARγ Signaling. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 9136282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshyar, R.; Hosseinian, M.; Rajabian Naghandar, M.; Hemmati, M.; Zarban, A.; Amini, Z.; Valavi, M.; Zare Beyki, M.; Mehrpour, O. Anti-Dyslipidemic Properties of Saffron: Reduction in the Associated Risks of Atherosclerosis and Insulin Resistance. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2016, 18, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, A.; Tajik, A.; Seiiedi, S.S.; Khadem, R.; Tootooni, H.; Taherynejad, M.; Sabet Eqlidi, N.; Alavi dana, S.M.M.; Deravi, N. A Review of the Anti-Diabetic Potential of Saffron. Nutr. Metab. Insights 2022, 15, 11786388221095223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouahhoud, S.; Lahmass, I.; Bouhrim, M.; Khoulati, A.; Sabouni, A.; Benabbes, R.; Asehraou, A.; Choukri, M.; Bnouham, M.; Saalaoui, E. Antidiabetic Effect of Hydroethanolic Extract of Crocus sativus Stigmas, Tepals and Leaves in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2019, 23, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Asdaq, S.M.B.; Mannasaheb, B.A.; Orfali, R.; Shaikh, I.A.; Alshehri, A.; Alghamdi, A.; Alrashdi, M.M.; Almadani, M.E.; Abdalla, F.M.A. Antidiabetic and Antioxidant Potential of Crocin in High-Fat Diet plus Streptozotocin-Induced Type-2 Diabetic Rats. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2024, 38, 03946320231220178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahmass, I.; Sabouni, A.; Elyoubi, M.; Benabbes, R.; Mokhtari, S.; Saalaoui, E. Anti-Diabetic Effect of Aqueous Extract Crocus sativus L. in Tartrazine Induced Diabetic Male Rats. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2017, 21, 312–321. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, L.-L.; Lu, H.-Q.; Li, W.-N.; Huang, H.-P.; Zhou, H.-Y.; Leng, E.; Zhang, Y. Protective Effects of Quercetin and Crocin in the Kidneys and Liver of Obese Sprague-Dawley Rats with Type 2 Diabetes: Effects of Quercetin and Crocin on T2DM Rats. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2021, 40, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drioiche, A.; Ailli, A.; Handaq, N.; Remok, F.; Elouardi, M.; Elouadni, H.; Al Kamaly, O.; Saleh, A.; Bouhrim, M.; Elazzouzi, H. Identification of Compounds of Crocus sativus by GC-MS and HPLC/UV-ESI-MS and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Anticoagulant, and Antidiabetic Properties. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ahn, D.; Nam, G.; Kwon, J.; Song, S.; Kang, M.J.; Ahn, H.; Chung, S.J. Identification of Crocetin as a Dual Agonist of GPR40 and GPR120 Responsible for the Antidiabetic Effect of Saffron. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Liu, D.; Deng, Z.; Hu, W.; Li, Z.; Li, Y. The Hypoglycemic and Renal Protection Properties of Crocin via Oxidative Stress-Regulated NF-κB Signaling in Db/Db Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoulaki, P.; Kotzakioulafi, E.; Nakas, A.; Kontoninas, Z.; Karlafti, E.; Evripidou, P.; Kantartzis, K.; Savopoulos, C.; Chourdakis, M.; Didangelos, T. Effect of Crocus sativus Extract Supplementation in the Metabolic Control of People with Diabetes Mellitus Type 1: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milajerdi, A.; Jazayeri, S.; Hashemzadeh, N.; Shirzadi, E.; Derakhshan, Z.; Djazayeri, A.; Akhondzadeh, S. The Effect of Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) Hydroalcoholic Extract on Metabolic Control in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Triple-Blinded Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2018, 23, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Kakouri, E.; Agalou, A.; Kanakis, C.; Beis, D.; Tarantilis, P.A. Crocins from Crocus sativus L. in the Management of Hyperglycemia. in Vivo Evidence from Zebrafish. Molecules 2020, 25, 5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaazaa, L.; Naceiri Mrabti, H.; Ed-Dra, A.; Bendahbia, K.; Hami, H.; Soulaymani, A.; Ibriz, M. Determination of Mineral Composition and Phenolic Content and Investigation of Antioxidant, Antidiabetic, and Antibacterial Activities of Crocus sativus L. Aqueous Stigmas Extracts. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 2021, 7533938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazman, Ö.; Aksoy, L.; Büyükben, A. Effects of Crocin on Experimental Obesity and Type-2 Diabetes. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 46, 1593–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raafat, K.; Aboul-Ela, M.; El-Lakany, A. Phytochemical and Anti-Neuropathic Investigations of Crocus sativus via Alleviating Inflammation, Oxidative Stress and Pancreatic Beta-Cells Regeneration. Chin. Herb. Med. 2020, 12, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Nan, C.; Wang, H.; Su, Q.; Xue, W.; Chen, Y.; Shan, X.; Duan, J.; Chen, G.; Tao, W. Crocetin Ester Improves Myocardial Ischemia via Rho/ROCK/NF-κB Pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 38, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Arora, S.; Sharma, A.; Joshi, S.; Ray, R.; Bhatia, J.; Kumari, S.; Arya, D. Preventive Effect of Crocin of Crocus sativus on Hemodynamic, Biochemical, Histopathological and Ultrastuctural Alterations in Isoproterenol-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Rats. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Han, X.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Z.; Sun, S.; Chu, X.; Cheng, J.; Guan, S. Crocin Attenuates Isoprenaline-Induced Myocardial Fibrosis by Targeting TLR4/NF-κB Signaling: Connecting Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2020, 393, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.; Zhao, J.; Kang, Y.; Liu, L.; He, W.; Xie, Y.; Wang, R.; Shan, L.; Li, X.; Ma, K. Effect and Mechanism of Safranal on ISO-Induced Myocardial Injury Based on Network Pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 305, 116103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahim, V.B.; Khammar, M.T.; Rakhshandeh, H.; Samzadeh-Kermani, A.; Hosseini, A.; Askari, V.R. Crocin Protects Cardiomyocytes against LPS-Induced Inflammation. Pharmacol. Rep. 2019, 71, 1228–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zheng, B.; Che, K.; Han, X.; Li, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Shi, J.; Sun, S. Protective Effects of Safranal on Hypoxia/Reoxygenation-induced Injury in H9c2 Cardiac Myoblasts via the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β Signaling Pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahine, N.; Nader, M.; Duca, L.; Martiny, L.; Chahine, R. Saffron Extracts Alleviate Cardiomyocytes Injury Induced by Doxorubicin and Ischemia-Reperfusion in Vitro. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 39, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedimanesh, S.; Bathaie, S.Z.; Ostadrahimi, A.; Jafarabadi, M.A.; Sadeghi, M.T. The Effect of Crocetin Supplementation on Markers of Atherogenic Risk in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: A Pilot, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 7461–7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsherbiny, N.M.; Salama, M.F.; Said, E.; El-Sherbiny, M.; Al-Gayyar, M.M. Crocin Protects against Doxorubicin-Induced Myocardial Toxicity in Rats through down-Regulation of Inflammatory and Apoptic Pathways. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2016, 247, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmaraii, N.; Babaei, H.; Nayebi, A.M.; Assadnassab, G.; Helan, J.A.; Azarmi, Y. Crocin Treatment Prevents Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Rats. Life Sci. 2016, 157, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Li, J.; Shi, J.; Chu, L.; Han, X.; Chu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J. Crocin Ameliorates Arsenic Trioxide-induced Cardiotoxicity via Keap1-Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway: Reducing Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 131, 110713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radmanesh, E.; Dianat, M.; Badavi, M.; Goudarzi, G.; Mard, S.A.; Radan, M. Protective Effect of Crocin on Hemodynamic Parameters, Electrocardiogram Parameters, and Oxidative Stress in Isolated Hearts of Rats Exposed to PM10. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2022, 25, 460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Naddafi, M.; Eghbal, M.A.; Ghazi-Khansari, M.; Sattari, M.R.; Azarmi, Y. Study of the Cardioprotective Effects of Crocin on Human Cardiac Myocyte Cells and Reduction of Oxidative Stress Produced by Aluminum Phosphide Poisoning. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021, 73, 1539–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razavi, B.; Hosseinzadeh, H.; Imenshahidi, M.; Malekian, M.; Ramezani, M.; Abnous, K. Evaluation of Protein Ubiquitylation in Heart Tissue of Rats Exposed to Diazinon (an Organophosphate Insecticide) and Crocin (an Active Saffron Ingredient): Role of HIF-1α. Drug Res. 2015, 65, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Afzal, O.; Altamimi, A.S.; Nasar Mir Najib Ullah, S.; Shilbayeh, S.A.R.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Khan, S. Analysis of Anti-Arrhythmic Impacts of Crocin through Estimation of Expression of Cx43 in Myocardial Infarction Using a Rat Animal Model. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 37164–37169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, E.; Kadoglou, N.; Stasinopoulou, M.; Konstandi, O.; Kenoutis, C.; Kakazanis, Z.; Rizakou, A.; Kostomitsopoulos, N.; Valsami, G. Crocus sativus L. Aqueous Extract Reduces Atherogenesis, Increases Atherosclerotic Plaque Stability and Improves Glucose Control in Diabetic Atherosclerotic Animals. Atherosclerosis 2018, 268, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efentakis, P.; Rizakou, A.; Christodoulou, E.; Chatzianastasiou, A.; López, M.; León, R.; Balafas, E.; Kadoglou, N.; Tseti, I.; Skaltsa, H. Saffron (Crocus sativus) Intake Provides Nutritional Preconditioning against Myocardial Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury in Wild Type and ApoE (−/−) Mice: Involvement of Nrf2 Activation. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Chen, M.; Ren, X.-C.; Zhou, X.-B.; Shang, Q.; Lu, W.-Q.; Luo, P.; Jiang, Z.-H. Synthesis and Cardiomyocyte Protection Activity of Crocetin Diamide Derivatives. Fitoterapia 2017, 121, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Jin, W.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, S.; Chu, X.; Zhang, J. Safranal, an Active Constituent of Saffron, Ameliorates Myocardial Ischemia via Reduction of Oxidative Stress and Regulation of Ca2+ Homeostasis. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 143, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshibani, F.A.; Alamami, A.D.; Mohammed, H.A.; Rasheed, R.A.; El Sabban, R.M.; Yehia, M.A.; Abdel Mageed, S.S.; Majrashi, T.A.; Elkaeed, E.B.; El Hassab, M.A. A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Activities of Arbutus Pavarii Pampan Fruit; in Vitro and in Vivo Biological Evaluations, and in Silico Investigations. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2024, 39, 2293639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantar, M.; Kalantari, H.; Goudarzi, M.; Khorsandi, L.; Bakhit, S.; Kalantar, H. Crocin Ameliorates Methotrexate-Induced Liver Injury via Inhibition of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Rats. Pharmacol. Rep. 2019, 71, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhimwal, J.; Sharma, S.; Kulurkar, P.; Patial, V. Crocin Attenuates CCl4-Induced Liver Fibrosis via PPAR-γ Mediated Modulation of Inflammation and Fibrogenesis in Rats. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2020, 39, 1639–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaee-Khorasany, A.; Razavi, B.M.; Taghiabadi, E.; Yazdi, A.T.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Effect of Crocin, an Active Saffron Constituent, on Ethanol Toxicity in the Rat: Histopathological and Biochemical Studies. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2020, 23, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Sokar, S.S.; Alkabbani, M.A.; Akool, E.-S.; Abu-Risha, S.E.-S. Hepatoprotective Effects of Carvedilol and Crocin against Leflunomide-Induced Liver Injury. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 113, 109297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowsarkhizi, A.S.; Abedi, S.; Karimi, E.; Ghorani, B.; Oskoueian, E. Nanofiber-Based Delivery of Crocus sativus Phenolic Compounds to Ameliorate the Cisplatin-Induced Hepatotoxicity in Mice. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 120, 106334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayunt, N.Ö.; Parlak, A.E.; Türkoğlu, S.; Taş, F. Hepatoprotective Effects of Safranal on Acetaminophen-Induced Hepatotoxicity in Rats. Open Chem. 2024, 22, 20240029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdu, S.; Juaid, N.; Amin, A.; Moulay, M.; Miled, N. Therapeutic Effects of Crocin Alone or in Combination with Sorafenib against Hepatocellular Carcinoma: In Vivo & in Vitro Insights. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Lin, S.; Gong, J.; Feng, P.; Cao, Y.; Li, Q.; Jiang, Y.; You, Y.; Tong, Y.; Wang, P. Exploring the Protective Effects and Mechanism of Crocetin from Saffron against NAFLD by Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 681391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheirandish, R.; Saberi, M.; Azizi, S.; Khakdan, R.; Kordzadeh Kermani, Z. The Effect of Saffron (Crocus sativus) on Oxymetholone-Induced Hepatic and Renal Injury in Rats. Iran. J. Toxicol. 2021, 15, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, D.M.; Hassan, H.A.; Nafea, O.E.; El Fattah, E.R.A. Crocin Averts Functional and Structural Rat Hepatic Disturbances Induced by Copper Oxide Nanoparticles. Toxicol. Res. 2022, 11, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, A.A.; Ramdan, H.S.; Al-Eisa, R.A.; Adle Fadle, B.O.; El-Shenawy, N.S. Effect of Saffron Extract on the Hepatotoxicity Induced by Copper Nanoparticles in Male Mice. Molecules 2021, 26, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taher, G.N. Effectiveness of Saffron against Hepatotoxicity Caused by Silver Nanoparticles in Vivo. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 16, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, I.; Bayram, I.; Oto, G.; Erten, R.; Almali, A.; Ilik, Z. Saffron and Saffron Ingredients like Safranal and Crocin’s Cytoprotective Effects on Carbon Tetrachloride Induced Liver Damage. East. J. Med. 2022, 27, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, V.; Hashemi, S.A.; Khalili, A.; Fallah, P.; Ahmadian-Attari, M.M.; Beikzadeh, L.; Mazloom, R.; Najafizadeh, P.; Bayat, G. Saffron Offers Hepatoprotection via Up-Regulation of Hepatic Farnesoid-X-Activated Receptors in a Rat Model of Acetaminophen-Induced Hepatotoxicity. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2021, 11, 622. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshyar, R.; Sebzari, A.; Balforoush, M.; Valavi, M.; Hosseini, M. The Impact of Crocus sativus Stigma against Methotrexate-Induced Liver Toxicity in Rats. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2020, 17, 20190201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouahhoud, S.; Touiss, I.; Khoulati, A.; Lahmass, I.; Mamri, S.; Meziane, M.; Elassri, S.; Bencheikh, N.; Benabbas, R.; Asehraou, A. Hepatoprotective Effects of Hydroethanolic Extracts of Crocus sativus Tepals, Stigmas and Leaves on Carbon Tetrachloride Induced Acute Liver Injury in Rats. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 25, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.; Prabhavalkar, K. Anti-Asthmatic Effects of Saffron Extract and Salbutamol in an Ovalbumin-Induced Airway Model of Allergic Asthma. Sinusitis 2021, 5, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, W.A.; Sakr, S.; Domouky, A.M. Comparative Study of Oral versus Parenteral Crocin in Mitigating Acrolein-Induced Lung Injury in Albino Rats. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianat, M.; Radan, M.; Mard, S.A.; Sohrabi, F.; Saryazdi, S.S.N. Contribution of Reactive Oxygen Species via the OXR1 Signaling Pathway in the Pathogenesis of Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: The Protective Role of Crocin. Life Sci. 2020, 256, 117848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabani, M.; Goudarzi, M.; Mehrzadi, S.; Siahpoosh, A.; Mohammadi, M.; Khalili, H.; Malayeri, A. Crocin: A Protective Natural Antioxidant against Pulmonary Fibrosis Induced by Bleomycin. Pharmacol. Rep. 2020, 72, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceylan, T.; Akın, A.; Kaymak, E.; Varinli, Ş.; Toluk, A. Crocin Suppresses Inflammatory Response in LPS-Induced Acute Lung Injury (ALI) Via Regulation of HMGB1/TLR4 Inflammation Pathway. J. Basic Clin. Health Sci. 2024, 8, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, V.; Nobakht, B.F.; Bagheri, H.; Saeedi, P.; Ghanei, M.; Halabian, R. Metabolomics to Investigate the Effect of Preconditioned Mesenchymal Stem Cells with Crocin on Pulmonary Epithelial Cells Exposed to 2-Chloroethyl Ethyl Sulfide. J. Proteom. 2024, 308, 105280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukhari, S.I.; Pattnaik, B.; Rayees, S.; Kaul, S.; Dhar, M.K. Safranal of Crocus sativus L. Inhibits Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase and Attenuates Asthma in a Mouse Model of Asthma. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarzia, A.; Ghasemi, S.Z.; Behrouz, S.; Boskabady, M.H. The Effects of Crocus sativus Extract on Inhaled Paraquat-Induced Lung Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Pathological Changes and Tracheal Responsiveness in Rats. Toxicon 2023, 235, 107316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghobadi, H.; Abdollahi, N.; Madani, H.; Aslani, M.R. Effect of Crocin from Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) Supplementation on Oxidant/Antioxidant Markers, Exercise Capacity, and Pulmonary Function Tests in COPD Patients: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 884710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarzia, A.; Beigoli, S.; Ghalibaf, M.H.E.; Ghasemi, S.Z.; Abbasian, A.; Mahzoon, E.; Toosi, A.N.; Roshan, N.M.; Boskabady, M.H. The Preventive Effectiveness of Crocus sativus Extract in Treating Lung Injuries Caused by Inhaled Paraquat in Rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 337, 118767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soozangar, N.; Amani, M.; Jeddi, F.; Salimnejad, R.; Aslani, M.R. The Suppressive Effects of Crocin from Saffron on Allergic Airway Inflammation through Drp1/Nfr1/Mfn2/Pgc1-Alpha Signaling Pathway in Mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 337, 118862. [Google Scholar]

- Ouahhoud, S.; Marghich, M.; Makrane, H.; Karim, A.; Khoulati, A.; Mamri, S.; Addi, M.; Hano, C.; Benabbes, R.; Aziz, M. In Vitro Assessment of Myorelaxant and Antispasmodic Effects of Stigmas, Tepals, and Leaves Hydroethanolic Extracts of Crocus sativus. J. Food Biochem. 2023, 2023, 4165305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Bai, W.; Chen, Q.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Wen, A.; Yang, X. Protective Effect of Crocetin against Burn-Induced Intestinal Injury. J. Surg. Res. 2015, 198, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafarzadeh, S.; Hobbenaghi, R.; Tamaddonfard, E.; Farshid, A.A.; Imani, M. Crocin Exerts Improving Effects on Indomethacin-Induced Small Intestinal Ulcer by Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Apoptotic Mechanisms. Vet. Res. Forum 2019, 10, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tamaddonfard, E.; Erfanparast, A.; Farshid, A.A.; Imani, M.; Mirzakhani, N.; Salighedar, R.; Tamaddonfard, S. Safranal, a Constituent of Saffron, Exerts Gastro-Protective Effects against Indomethacin-Induced Gastric Ulcer. Life Sci. 2019, 224, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mard, S.A.; Pipelzadeh, M.H.; Teimoori, A.; Neisi, N.; Mojahedin, S.; Khani, M.Z.S.; Ahmadi, I. Protective Activity of Crocin against Indomethacin-Induced Gastric Lesions in Rats. J. Nat. Med. 2016, 70, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadifard, M.; Javdani, H.; Khalili-Tanha, G.; Farahi, A.; Foadoddini, M.; Hosseini, M. Evaluation of Therapeutic Efficacy of Stigma and Petal Extracts of Crocus sativus L. on Acetic Acid-Induced Gastric Ulcer in Rats. Tradit. Integr. Med. 2021, 6, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Maraghy, S.A.; Rizk, S.M.; Shahin, N.N. Gastroprotective Effect of Crocin in Ethanol-Induced Gastric Injury in Rats. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2015, 229, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Haileselassie, Y.; Ji, A.R.; Maecker, H.T.; Sinha, S.R.; Brim, H.; Habtezion, A.; Ashktorab, H. Protective Effect of Saffron in Mouse Colitis Models through Immune Modulation. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2022, 67, 2922–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedik, S.; Erdemli, M.; Gul, M.; Yigitcan, B.; Gozukara Bag, H.; Aksungur, Z.; Altinoz, E. Investigation of the Protective Effects of Crocin on Acrylamide Induced Small and Large Intestine Damage in Rats. Biotech. Histochem. 2018, 93, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mard, S.A.; Nikraftar, Z.; Farbood, Y.; Mansouri, E. A Preliminary Study of the Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Apoptotic Effects of Crocin against Gastric Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rats. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 51, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodir, A.E.; Said, E.; Atif, H.; ElKashef, H.A.; Salem, H.A. Targeting Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling by Crocin: Role in Attenuation of AA-Induced Ulcerative Colitis in Rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 110, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgun, B.E.; Erdeml, M.E.; Gul, M.; Gul, S.; Bag, H.G.; Aksungur, Z.; Altinoz, E. Crocin Protects Intestine Tissue against Carbon Tetrachloride-Mediated Oxidative Stress in Rats. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2018, 37, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banskota, S.; Brim, H.; Kwon, Y.H.; Singh, G.; Sinha, S.R.; Wang, H.; Khan, W.I.; Ashktorab, H. Saffron Pre-Treatment Promotes Reduction in Tissue Inflammatory Profiles and Alters Microbiome Composition in Experimental Colitis Mice. Molecules 2021, 26, 3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, P.; Li, Q.; Liu, L.; Wang, S.; Wu, Z.; Tao, Y.; Huang, P.; Wang, P. Crocetin Prolongs Recovery Period of DSS-Induced Colitis via Altering Intestinal Microbiome and Increasing Intestinal Permeability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, S.; Jin, L.H. The Protective Effect of Safranal against Intestinal Tissue Damage in Drosophila. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2022, 439, 115939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]