Carvacrol-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles as a Multifunctional Nanotherapeutic Strategy Targeting Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Genotoxicity in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Molecular Docking

2.2. Preparation of Carvacrol (CRV)-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles (CRV-CHNPs)

- LE (%) = [CRV in nanoparticles / CRV added] × 100

- LC (%) = [CRV in nanoparticles / Nanoparticle weight] × 100

2.3. Animals, Diets, and Experimental Protocol

- Group I (Control): Received a standard laboratory rodent diet.

- Group III (CRV-CNPs): Received a standard diet and treated with carvacrol-loaded chitosan nanoparticles (100 mg/kg body weight) via oral gavage during the final six weeks.

- Group IV (HFD): Fed a high-fat diet (HFD) for 20 weeks according to the method described by Chang et al. [26].

- Group V (HFD + CRV): Fed an HFD for 20 weeks and co-administered carvacrol (100 mg/kg body weight) daily via oral gavage for the final six weeks.

- Group VI (HFD + CRV-CNPs): Fed an HFD for 20 weeks and co-administered CRV-loaded chitosan nanoparticles (100 mg/kg body weight) daily via oral gavage for the final six weeks.

2.4. Tissue Sample Collection and Homogenization

2.5. Body Weight and Liver Index

2.6. Serum Biochemistry and Liver Redox Assessment

2.7. Inflammatory Markers

2.8. RNA Isolation, cDNA Synthesis, and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

2.9. Histological Evaluation of Liver

2.10. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Docking Results

3.2. Characterization of Carvacrol-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles (CRV-CNPs)

3.3. Body Weight and Liver Index Results

3.4. Hepatic Function and Lipid Metabolism

3.5. Redox Status

3.6. Inflammation Response

3.7. Apoptosis-Related Genes

3.8. Hepatic DNA Damage Biomarkers

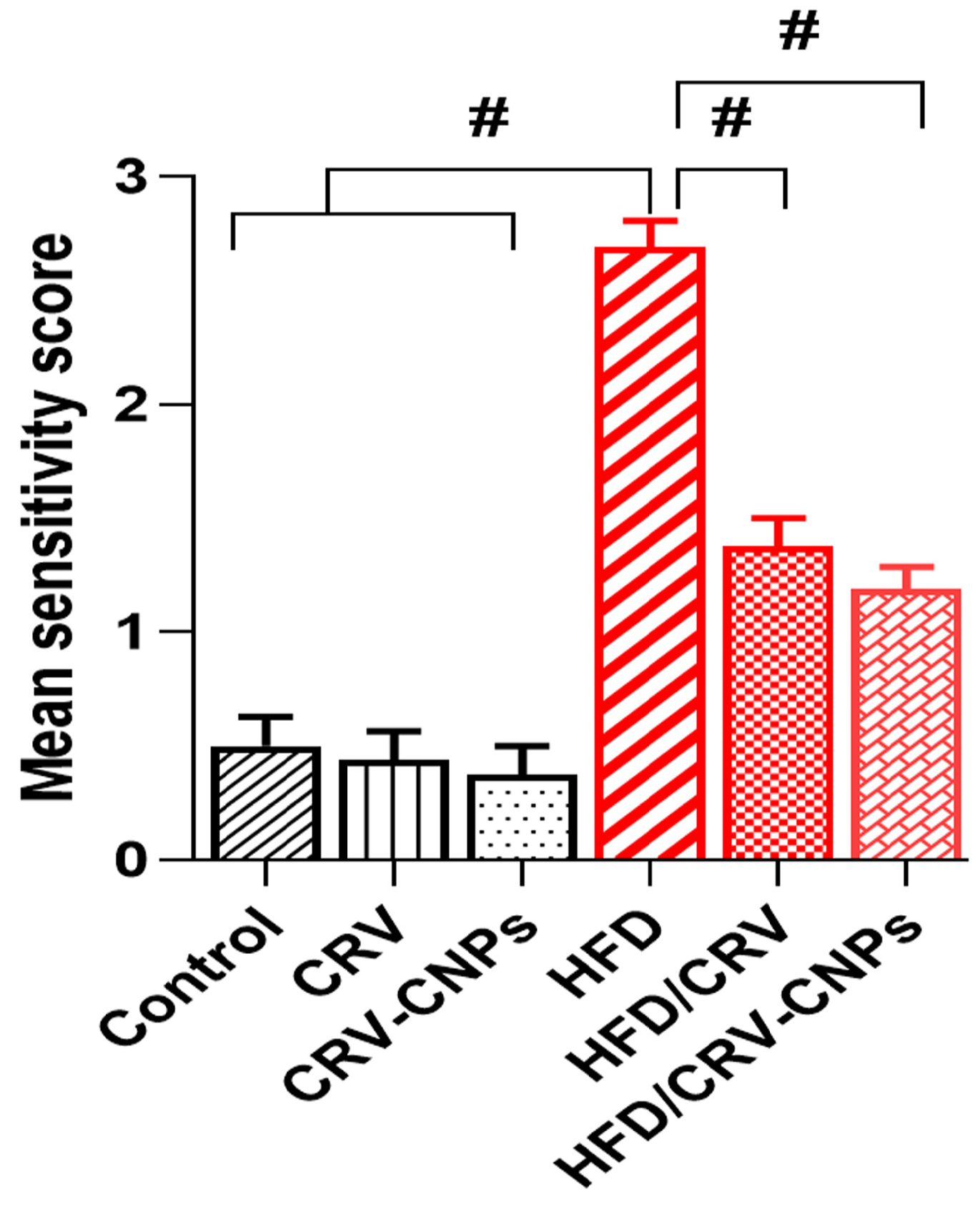

3.9. Histopathological Examination

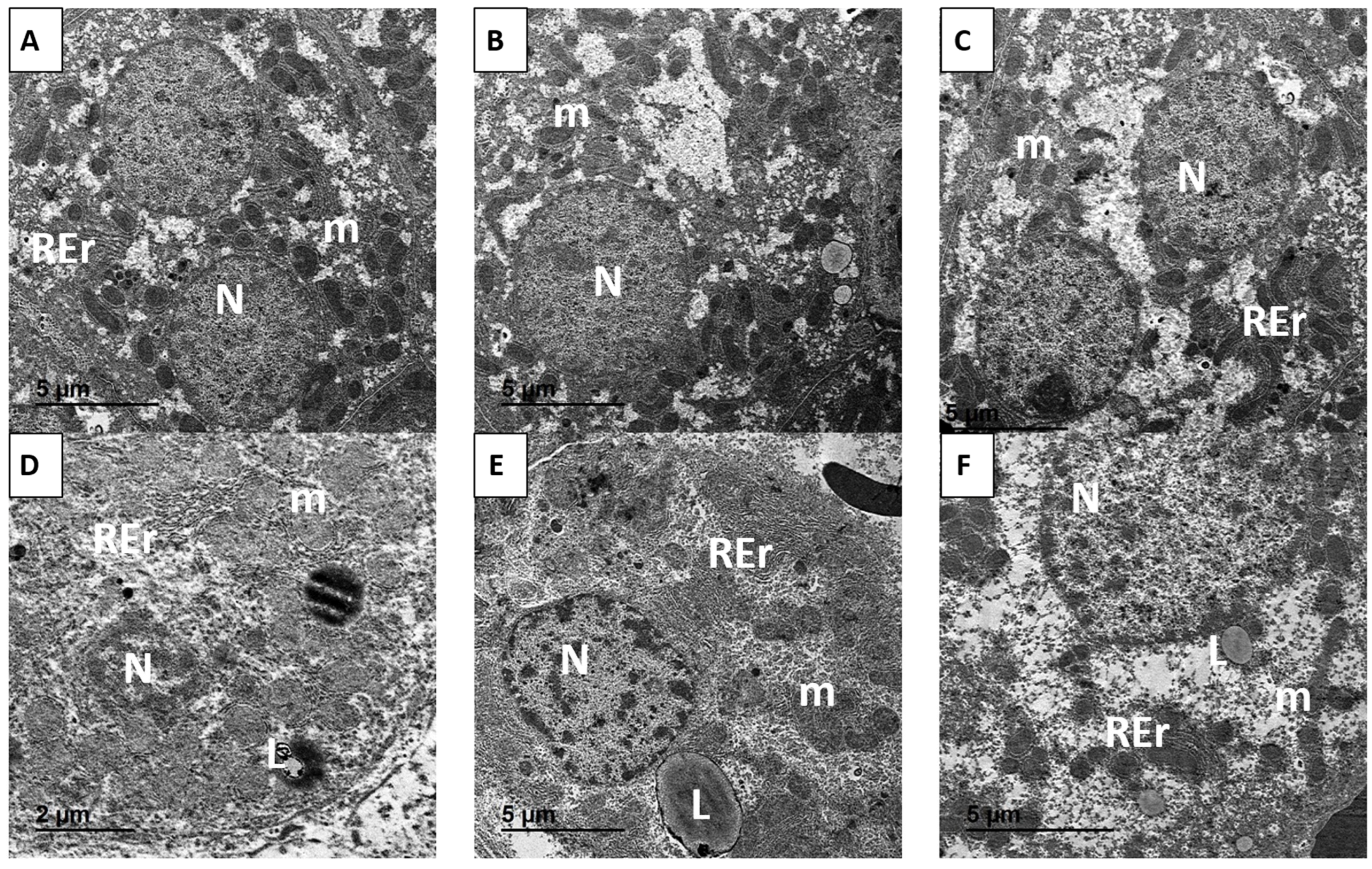

3.10. Ultrastructural Examination

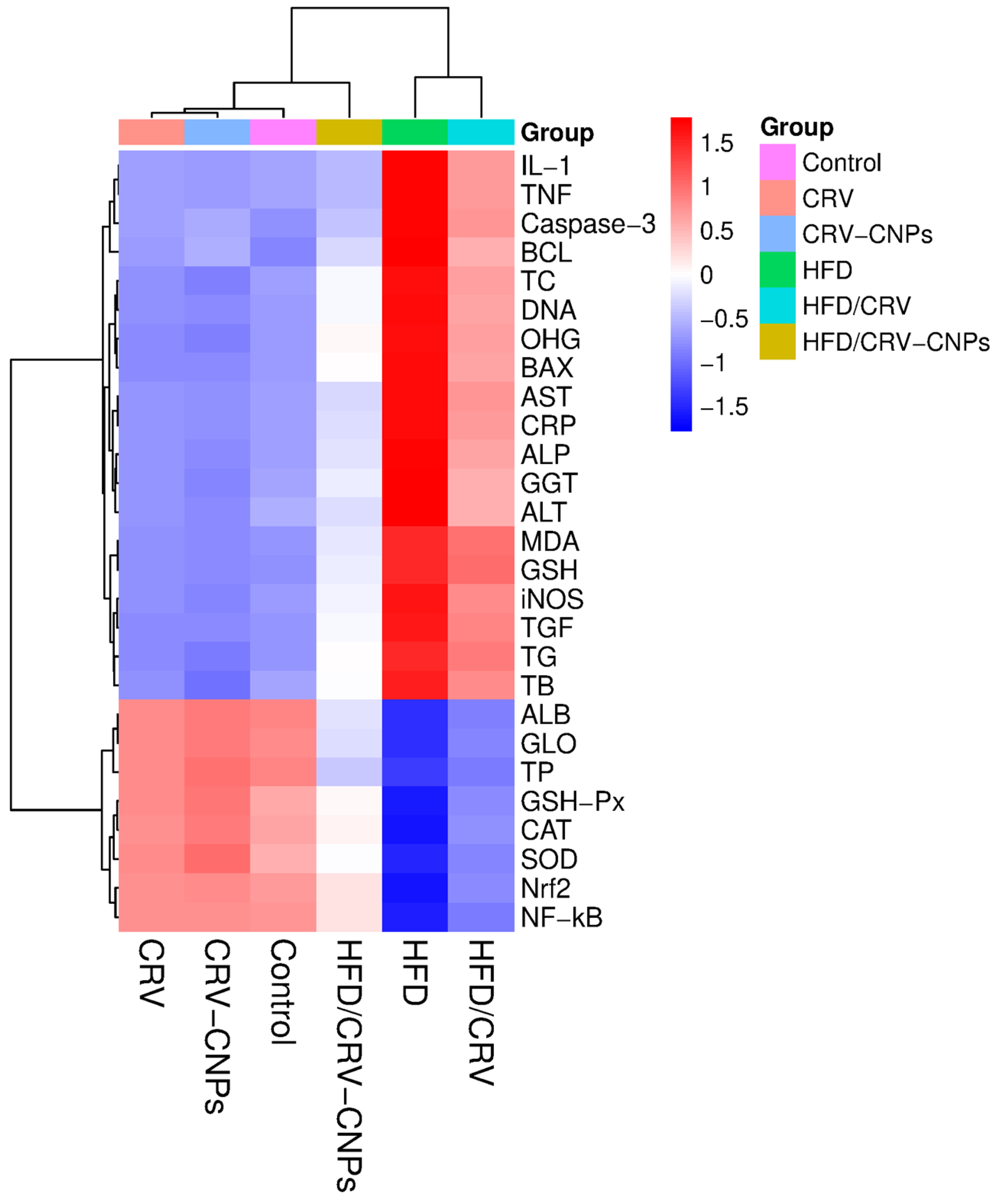

3.11. Multivariable Analysis

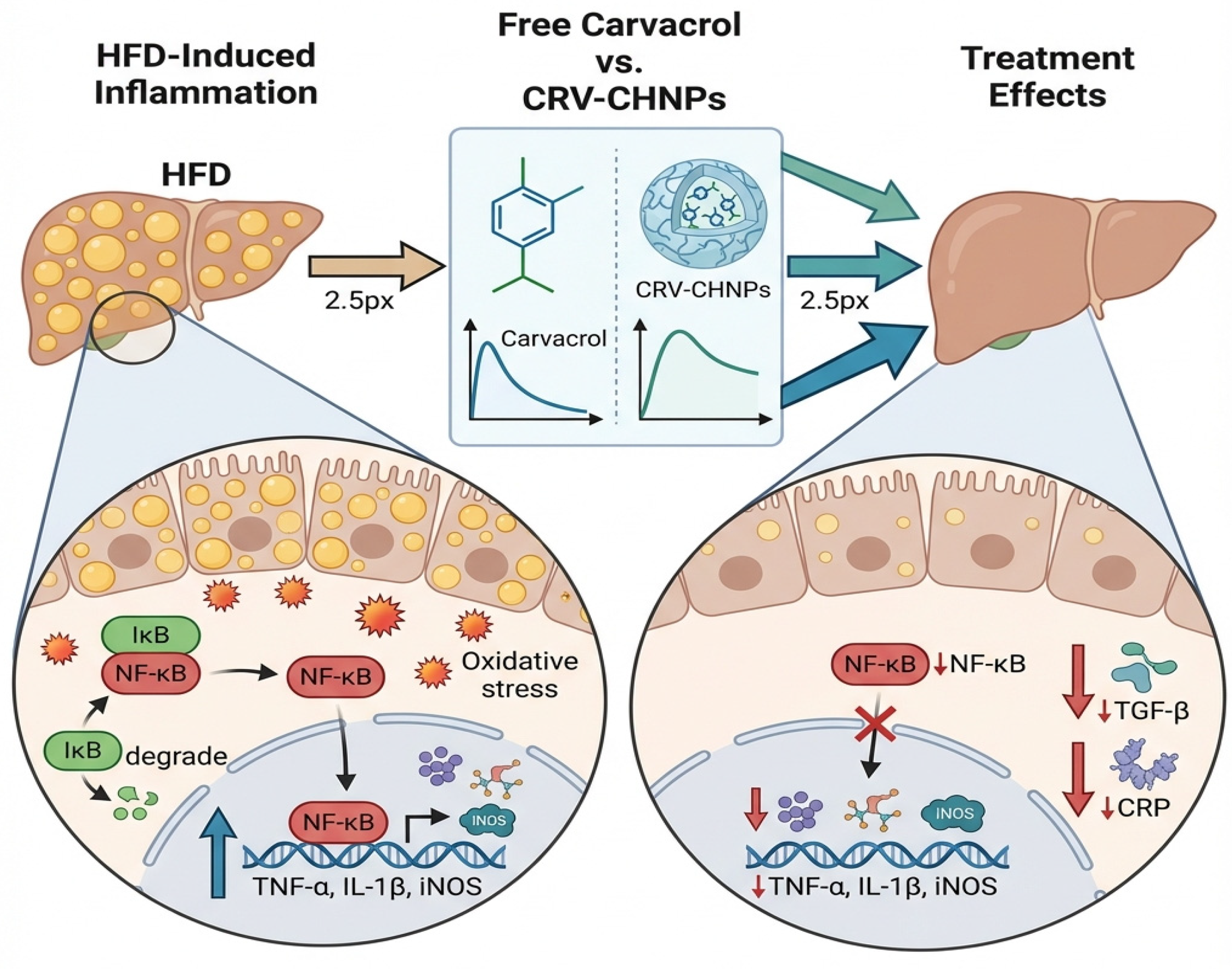

4. Discussion

4.1. Integration and Critical Comparison to Previous Work

4.2. Lipid Metabolism and Antioxidant Restoration

4.3. Inflammation and Apoptosis

4.4. Histopathological and Ultrastructural Preservation

4.5. Multivariate Comparisons

4.6. Innovative Mechanistic Insight

4.7. Study Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AASLD | American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases |

| ALB | Albumin |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| Bax | Bcl-2-associated X protein |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| CAT | Catalase |

| Caspase-3 | Cysteine–aspartic acid protease-3 |

| CH | Chitosan |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CRV | Carvacrol |

| CRV-CNPs | Carvacrol-loaded chitosan nanoparticles |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| GMP | Good Manufacturing Practice |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| GSH-Px | Glutathione peroxidase |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| HSCs | Hepatic stellate cells |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| LD | Lipid droplets |

| LC | Loading content |

| LE | Loading efficiency |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| NAFLD | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NASH | Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| PDI | Polydispersity index |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| SRplot | Science and Research Plotting Tool |

| TB | Total bilirubin |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-beta |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

References

- Han, S.K.; Baik, S.K.; Kim, M.Y. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Definition and subtypes. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29, S5–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Chang, Y.; Cho, Y.K.; Ahn, J.; Shin, H.; Ryu, S. Metabolically healthy versus unhealthy obesity and risk of fibrosis progression in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 2019, 39, 1884–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bence, K.K.; Birnbaum, M.J. Metabolic drivers of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Mol. Metab. 2021, 50, 101143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierantonelli, I.; Svegliati-Baroni, G. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Basic Pathogenetic Mechanisms in the Progression From NAFLD to NASH. Transplantation 2019, 103, e1–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvoza, N.; Giraudi, P.J.; Tiribelli, C.; Rosso, N. Natural Compounds for Counteracting Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD): Advantages and Limitations of the Suggested Candidates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallsworth, K.; McPherson, S.; Anstee, Q.M.; Flynn, D.; Haigh, L.; Avery, L. Digital Intervention With Lifestyle Coach Support to Target Dietary and Physical Activity Behaviors of Adults With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Systematic Development Process of VITALISE Using Intervention Mapping. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e20491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nendouvhada, L.P.; Sibuyi, N.R.S.; Fadaka, A.O.; Meyer, S.; Madiehe, A.M.; Meyer, M.; Gabuza, K.B. Phytonanotherapy for the Treatment of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.W.; Singal, A.K. Emerging medical therapies for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and for alcoholic hepatitis. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wal, P.; Yadav, S.; Jha, S.K.; Singh, A.; Bhargavi, B.; Shivaram, R.; Imran, M.; Aziz, N. Role of natural compounds in non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases (NAFLD): A mechanistic approach. Egypt. Liver J. 2025, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghzadeh, S.; Hejazian, S.H.; Jamhiri, M.; Hafizibarjin, Z.; Sadeghzadeh, S.; Safari, F. The effect of carvacrol on transcription levels of Bcl-2 family proteins in hypertrophied heart of rats. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 22, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni, R.; Karimi, J.; Tavilani, H.; Khodadadi, I.; Hashemnia, M. Carvacrol Downregulates Lysyl Oxidase Expression and Ameliorates Oxidative Stress in the Liver of Rats with Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Liver Fibrosis. Indian. J. Clin. Biochem. 2020, 35, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khazdair, M.R.; Moshtagh, M.; Anaeigoudari, A.; Jafari, S.; Kazemi, T. Protective effects of carvacrol on lipid profiles, oxidative stress, hypertension, and cardiac dysfunction–A comprehensive review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 3137–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mączka, W.; Twardawska, M.; Grabarczyk, M.; Wińska, K. Carvacrol-A Natural Phenolic Compound with Antimicrobial Properties. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.; Choi, Y.; Park, S.; Park, T. Carvacrol prevents diet-induced obesity by modulating gene expressions involved in adipogenesis and inflammation in mice fed with high-fat diet. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, A.; Stringaro, A.; Colone, M.; Muntiu, A.; Angiolella, L. Antifungal Carvacrol Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles. Antibiotics 2021, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llana-Ruiz-Cabello, M.; Gutiérrez-Praena, D.; Pichardo, S.; Moreno, F.J.; Bermúdez, J.M.; Aucejo, S.; Cameán, A.M. Cytotoxicity and morphological effects induced by carvacrol and thymol on the human cell line Caco-2. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 64, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauriello, E.; Ferrari, G.; Donsì, F. Effect of formulation on properties, stability, carvacrol release and antimicrobial activity of carvacrol emulsions. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 197, 111424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, A.; Pahal, S.; Mudakavi, R.J.; Raichur, A.M.; Varma, M.M.; Sen, P. Impact of Bioinspired Nanotopography on the Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Efficacy of Chitosan. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 1340–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, U.; Chauhan, S.; Nagaich, U.; Jain, N. Current Advances in Chitosan Nanoparticles Based Drug Delivery and Targeting. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 9, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.; Vale, N.; Costa, F.M.T.A.; Martins, M.C.L.; Gomes, P. Tethering antimicrobial peptides onto chitosan: Optimization of azide-alkyne “click” reaction conditions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 165, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layek, B.; Lipp, L.; Singh, J. Cell Penetrating Peptide Conjugated Chitosan for Enhanced Delivery of Nucleic Acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 28912–28930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewii, U.E.; Attama, A.A.; Olorunsola, E.O.; Onugwu, A.L.; Nwakpa, F.U.; Anyiam, C.; Chijioke, C.; Ogbulie, T. Nanoparticles for drug delivery: Insight into in vitro and in vivo drug release from nanomedicines. Nano TransMed 2025, 4, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, A.; Mohammad Pour Kargar, H.; Beheshti, F.; Anaeigoudari, A.; Vaezi, G.; Hosseini, M. The effects of carvacrol on oxidative stress, inflammation, and liver function indicators in a systemic inflammation model induced by lipopolysaccharide in rats. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2023, 93, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, A.M.; El-Orabi, N.F.; Mahran, Y.F.; Badr, A.M.; Bayoumy, N.M.; Hagar, H.; Elmongy, E.I.; Atawia, R.T. In vivo and In silico evidence of the protective properties of carvacrol against experimentally-induced gastric ulcer: Implication of antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiapoptotic mechanisms. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2023, 382, 110649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Arab, Z.; Beheshti, F.; Anaeigoudari, A.; Shakeri, F.; Rajabian, A. Zataria multiflora and its constituent, carvacrol, counteract sepsis-induced aortic and cardiac toxicity in rat: Involvement of nitric oxide and oxidative stress. Anim. Models Exp. Med. 2023, 6, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-J.; Lin, J.-A.; Chen, S.-Y.; Weng, M.-H.; Yen, G.-C. Silymarin protects against high fat diet-evoked metabolic injury by induction of glucagon-like peptide 1 and sirtuin 1. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 56, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.S.; Li, H.Z.; Li, L.; Xie, C.Z.; Gao, J.M.; Chen, Y.Y.; Zhang, H.Y.; Hao, W.; Fu, J.H.; Guo, H. Rodent model of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: A systematic review. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 40, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Hartmann, P. How to calculate sample size in animal and human studies. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1215927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Festing, M.F.W.; Altman, D.G. Guidelines for the Design and Statistical Analysis of Experiments Using Laboratory Animals. ILAR J. 2002, 43, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.J.; Fan, J.G.; Ding, X.D.; Qiao, L.; Wang, G.L. Characterization of high-fat, diet-induced, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis with fibrosis in rats. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010, 55, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krohn, R.I. The colorimetric detection and quantitation of total protein. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodla, L.; Manubolu, M.; Pathakoti, K.; Jayakumar, T.; Sheu, J.-R.; Fraker, M.; Tchounwou, P.B.; Poondamalli, P.R. Protective Effects of Ammannia baccifera Against CCl4-Induced Oxidative Stress in Rats. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, P.; Blanckaert, N.; Kabra, P.M.; Thaler, M.M. Liquid-chromatographic determination of bilirubin and its conjugates in rat serum and human amniotic fluid. Clin. Chem. 1981, 27, 1704–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, W.H.; Khudair, T.T.; Al-Fartosi, K.G. Level of lipid profile and liver enzyme of diabetic male rats induced by streptozotocin treated with forxiga. 3c Empresa Investig. Y Pensam. Crítico 2023, 12, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, L.; Orenstein, J.M. Processing tissue and cells for transmission electron microscopy in diagnostic pathology and research. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 2439–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisse, E.; Braet, F.; Duimel, H.; Vreuls, C.; Koek, G.; Olde Damink, S.W.; van den Broek, M.A.; De Geest, B.; Dejong, C.H.; Tateno, C.; et al. Fixation methods for electron microscopy of human and other liver. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 2851–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinde, P.; Agraval, H.; Srivastav, A.K.; Yadav, U.C.S.; Kumar, U. Physico-chemical characterization of carvacrol loaded zein nanoparticles for enhanced anticancer activity and investigation of molecular interactions between them by molecular docking. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 588, 119795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaokun, O. Computational identification of polyphenols from medicinal plant extracts with biological activity against oxidative stress-related diseases: An in silico anti-inflammatory study. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 183, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghtadaie, A.; Mahboobi, H.; Fatemizadeh, S.; Kamal, M.A. Emerging role of nanotechnology in treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). EXCLI J. 2023, 22, 946–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, C.-Y.; Zhai, Z.-Z.; Li, Z.-F.; Wang, L. High fat diet-triggered non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A review of proposed mechanisms. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 330, 109199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez-Vázquez, O.; Benedé-Ubieto, R.; Guo, F.; Gómez-Santos, B.; Aspichueta, P.; Reissing, J.; Bruns, T.; Sanz-García, C.; Sydor, S.; Bechmann, L.P.; et al. Fat: Quality, or Quantity? What Matters Most for the Progression of Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD). Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakır, M.; Geyikoglu, F.; Colak, S.; Turkez, H.; Bakır, T.O.; Hosseinigouzdagani, M. The carvacrol ameliorates acute pancreatitis-induced liver injury via antioxidant response. Cytotechnology 2016, 68, 1131–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohebbati, R.; Paseban, M.; Soukhtanloo, M.; Jalili-Nik, M.; Shafei, M.N.; Yazdi, A.J.; Rad, A.K. Effects of standardized Zataria multiflora extract and its major ingredient, Carvacrol, on Adriamycin-induced hepatotoxicity in rat. Biomed. J. 2018, 41, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Assi, R.; Abdulbaqi, I.M.; Siok Yee, C. The Evaluation of Drug Delivery Nanocarrier Development and Pharmacological Briefing for Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD): An Update. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavian, S.A.; Sathyapalan, T.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. The Emerging Role of Nanomedicine in the Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A State-of-the-Art Review. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2021, 2021, 4041415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Duan, F.; Li, S.; Lu, B. Administration of silymarin in NAFLD/NASH: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Hepatol. 2024, 29, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyave-Ospina, J.C.; Wu, Z.; Geng, Y.; Moshage, H. Role of Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Implications for Prevention and Therapy. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tan, H.-Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Z.-J.; Lao, L.; Wong, C.-W.; Feng, Y. The role of oxidative stress and antioxidants in liver diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 26087–26124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Hao, L.; Li, S.; Deng, J.; Yu, F.; Zhang, J.; Nie, A.; Hu, X. The NRF-2/HO-1 Signaling Pathway: A Promising Therapeutic Target for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 8061–8083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriel, P.; Ramos-Tovar, E.; Montes-Páez, G.; Buendía-Montaño, L.D. Experimental Models of Liver Damage Mediated by Oxidative Stress; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 529–546. [Google Scholar]

- Lebda, M.A.; Sadek, K.M.; Abouzed, T.K.; Tohamy, H.G.; El-Sayed, Y.S. Melatonin mitigates thioacetamide-induced hepatic fibrosis via antioxidant activity and modulation of proinflammatory cytokines and fibrogenic genes. Life Sci. 2018, 192, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, V.; Duennwald, M.L. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanaban, S.; Pully, D.; Samrot, A.V.; Gosu, V.; Sadasivam, N.; Park, I.K.; Radhakrishnan, K.; Kim, D.K. Rising Influence of Nanotechnology in Addressing Oxidative Stress-Related Liver Disorders. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Dwivedi, D.K.; Lahkar, M.; Jangra, A. Hepatoprotective potential of 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone against alcohol and high-fat diet induced liver toxicity via attenuation of oxido-nitrosative stress and NF-κB activation. Pharmacol. Rep. 2019, 71, 1235–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatayli, E.; Sadiq, S.C.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Grabbe, S.; Biersack, B.; Kaps, L. Curcumin and Its Derivatives in Hepatology: Therapeutic Potential and Advances in Nanoparticle Formulations. Cancers 2025, 17, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casals, G.; Perramón, M.; Casals, E.; Portolés, I.; Fernández-Varo, G.; Morales-Ruiz, M.; Puntes, V.; Jiménez, W. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles: A New Therapeutic Tool in Liver Diseases. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sharma, N.; Shukla, S.; Behl, T.; Gupta, S.; Anwer, M.K.; Vargas-De-La-Cruz, C.; Bungau, S.G.; Brisc, C. Understanding the Potential Role of Nanotechnology in Liver Fibrosis: A Paradigm in Therapeutics. Molecules 2023, 28, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.N.; Li, M.Q.; Zhang, H.J.; Xu, N.N.; Xu, Y.Q.; Liu, W.X.; Chen, T.T.; Li, N.; Wu, G.Y.; Zhao, J.M.; et al. Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems: A promising approach for the treatment of liver fibrosis. Int. J. Pharm X 2025, 10, 100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Niu, R.; Liu, X.; Wu, F.; Yang, X.; Ma, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, H.; Shao, L.; Wang, S. Nanomedicines in the Treatment of Liver Fibrosis: A Review. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 9641–9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafa, S.; Shetab Boushehri, M.A.; Ezzat, A.A.; Weiskirchen, R.; Lamprecht, A.; Mansour, S.; Tammam, S.N. Targeted Delivery of Anti-TGF-β1-siRNA Using PDGFR-β Peptide-Modified Chitosan Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Liver Fibrosis. Mol. Pharm. 2025, 22, 6741–6758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dariushnejad, H.; Roshanravan, N.; Wasman, H.M.; Cheraghi, M.; Pirzeh, L.; Ghorbanzadeh, V. Silibinin, Synergistically Enhances Vinblastine-Mediated Apoptosis in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cell Line: Involvement of Bcl2/Bax Caspase-3 Pathway. Int. J. Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell Res. 2024, 18, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, D.K.; Jena, G.B. NLRP3 inhibitor glibenclamide attenuates high-fat diet and streptozotocin-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in rat: Studies on oxidative stress, inflammation, DNA damage and insulin signalling pathway. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2020, 393, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omari Shekaftik, S.; Nasirzadeh, N. 8-Hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) as a biomarker of oxidative DNA damage induced by occupational exposure to nanomaterials: A systematic review. Nanotoxicology 2021, 15, 850–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma-On, C.; Sanpavat, A.; Whongsiri, P.; Suwannasin, S.; Hirankarn, N.; Tangkijvanich, P.; Boonla, C. Oxidative stress indicated by elevated expression of Nrf2 and 8-OHdG promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Med. Oncol. 2017, 34, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subudhi, P.D.; Bihari, C.; Sarin, S.K.; Baweja, S. Emerging role of edible exosomes-like nanoparticles (ELNs) as hepatoprotective agents. Nanotheranostics 2022, 6, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Ma, W.; Gu, Y.; Wu, H.; Bian, Z.; Liu, N.; Yang, D.; Chen, X. High-fat diet causes mitochondrial damage and downregulation of mitofusin-2 and optic atrophy-1 in multiple organs. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2023, 73, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, R.; Wu, Q.; Guo, L.; Ye, D.; Cao, Q.; Zhang, M.; Xian, Y.; Chen, M.; Yan, K.; Zheng, J. Pyridostigmine attenuated high-fat-diet induced liver injury by the reduction of mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress via α7nAChR and M3AChR. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2024, 38, e23671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ægidius, H.M.; Veidal, S.S.; Feigh, M.; Hallenborg, P.; Puglia, M.; Pers, T.H.; Vrang, N.; Jelsing, J.; Kornum, B.R.; Blagoev, B.; et al. Multi-omics characterization of a diet-induced obese model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Lopez, O. Multi-Omics Nutritional Approaches Targeting Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Genes 2022, 13, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabourian, P.; Yazdani, G.; Ashraf, S.S.; Frounchi, M.; Mashayekhan, S.; Kiani, S.; Kakkar, A. Effect of Physico-Chemical Properties of Nanoparticles on Their Intracellular Uptake. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Luo, S.; Xu, M.; He, Q.; Xie, J.; Wu, J.; Huang, Y. Transepithelial transport of nanoparticles in oral drug delivery: From the perspective of surface and holistic property modulation. Acta Pharm. Sinica B 2024, 14, 3876–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazi, O.E.; Alalalmeh, S.O.; Alnuaimi, G.R.H.; Shahwan, M.; Jairoun, A.A.; Alorfi, N.M.; Majrashi, S.A.; Alkhanani, M.F.; Alkhattabi, A.; Alourfi, M.M.; et al. NAFLD and nutraceuticals: A review of completed phase III and IV clinical trials. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1227046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Dai, Z.; Guo, J. Therapeutic Nanomaterials in NAFLD: Current Advances and Potential Applications in Patients with Concurrent HBV Infection. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 3803–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmanaban, S.; Baek, J.-W.; Chamarthy, S.S.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Samrot, A.V.; Gosu, V.; Park, I.-K.; Radhakrishnan, K.; Kim, D.-K. Nanoparticle-based therapeutic strategies for chronic liver diseases: Advances and insights. Liver Res. 2025, 9, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | * NCBI Gene ID_Rattus Norvegicus | Forward (5′→3′) | Reverse (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bax | 24887 | CGGCGAATTGGAGATGAACTGG | CTAGCAAAGTAGAAGAGGGCAACC |

| Bcl-2 | 24224 | TGTGGATGACTGACTACCTGAACC | CAGCCAGGAGAAATCAAACAGAGG |

| Caspase-3 | 25402 | GTGGAACTGACGATGATATGGC | CGCAAAGTGACTGGATGAACC |

| β-Actin | 81822 | AAGATCCTGACCGAGCGTGG | CAGCACTGTGTTGGCATAGAGG |

| Score | Composite Multi-Criteria Liver Assessment Score |

|---|---|

| 0 (none) | No pathological changes |

| 1 (mild) | The liver demonstrated sporadic to mild hepatocellular degeneration and necrosis, accompanied by little to no inflammatory cell infiltration and occasional vascular congestion. |

| 2 (moderate) | The liver showed marked inflammatory cell infiltration, moderate vacuolar hepatocyte degeneration, mild vascular congestion, and multifocal necrotic lesions. |

| 3 (severe) | The liver demonstrated extensive inflammatory infiltration and necrosis, along with severe degeneration of hepatocytes and moderate to severe vascular congestion. |

| Target | Affinity (kcal/mol) | Hydrogen Bonds | Hydrophobic Contacts | Active Residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nrf2 | −5.7 | 4 | 2 | Val606(2), Gly367(2), Ala366, Val418 |

| CAT | −5 | 1 | 3 | Arg363, His364(2), Pro368 |

| SOD | −5.4 | 2 | 4 | Val7(2), Cys6, Asn53(2), Val148 |

| GSH-Px | −6 | 0 | 6 | Glu88(2), Phe103(2), Arg106(2) |

| NF-қB | −6.3 | 0 | 8 | Trp464(3), Arg432(2), Lys430(2), Glu413 |

| TNF-α | −5.6 | 0 | 7 | Tyr119, Tyr59(3), Leu57(3) |

| Il-1β | −4.6 | 0 | 7 | Phe150(2), Met148, Leu110(2), Lys103, Thr147 |

| Caspase-3 | −4.1 | 0 | 5 | Lys137, Tyr195, Tyr197, Val266(2) |

| iNOS | −4.8 | 0 | 4 | Tyr270, Ile291, Pro273, Tyr299 |

| TGF-β | −4.1 | 1 | 5 | Asn103, Ala41, Ile22, Leu28, Trp30(2) |

| Items | Control | CRV | CRV-CNPs | HFD | HFD/CRV | HFD/CRV-CNPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP (g/dL) | 5.98 ± 0.38 # | 6.01 ± 0.42 # | 6.13 ± 0.41 # | 3.22 ± 0.33 | 3.95 ± 0.29 | 4.72 ± 0.49 #,¥ |

| Alb (g/dL) | 3.17 ± 0.15 # | 3.12 ± 0.11 # | 3.19 ± 0.28 # | 1.72 ± 0.09 | 2.01 ± 0.14 | 2.53 ± 0.13 *,#,¥ |

| Glo (g/dL) | 2.81 ± 0.16 # | 2.89 ± 0.18 # | 2.94 ± 0.20 # | 1.53 ± 0.12 | 1.94 ± 0.09 | 2.19 ± 0.07 #,¥ |

| ALT (U/L) | 34.21 ± 3.55 # | 31.20 ± 2.31 # | 30.03 ± 3.59 # | 88.21 ± 5.77 | 65.59 ± 4.16 # | 41.07 ± 3.38 *# |

| AST (U/L) | 71.13 ± 4.47 # | 70.13 ± 5.18 # | 68.52 ± 3.62 # | 141.91 ± 8.11 | 112.70 ± 7.16 # | 84.54 ± 4.25 *# |

| ALP (U/L) | 153.21 ± 6.93 # | 149.84 ± 5.08 # | 147.61 ± 6.17 # | 220.36 ± 10.37 | 184.16 ± 7.45 # | 166.27 ± 5.20 # |

| GGT (U/L) | 11.21 ± 1.12 # | 10.41 ± 2.14 # | 9.27 ± 1.40 # | 22.17 ± 3.02 | 18.41 ± 1.76 # | 14.33 ± 2.43 # |

| TB (g/dL) | 0.41 ± 0.06 # | 0.39 ± 0.08 # | 0.38 ± 0.04 # | 1.32 ± 0.12 | 0.87 ± 0.10 # | 0.62 ± 0.09 # |

| TG (mg/dL) | 57.12 ± 4.11 # | 55.39 ± 3.23 # | 52.28 ± 5.12 # | 123.31 ± 6.18 | 105.58 ± 4.57 # | 79.77 ± 3.62 *,#,¥ |

| TC (mg/dL) | 78.26 ± 5.42 # | 74.12 ± 6.18 # | 72.58 ± 4.77 # | 131.22 ± 8.26 | 98.16 ± 4.11 # | 86.27 ± 4.09 # |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alfawaz, M.; Elmorsy, E.M.; Alshammari, A.N.; Hakim, N.A.; Jawad, N.M.M.; Hassan, S.A.; Fawzy, M.S.; Esmaeel, S.E. Carvacrol-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles as a Multifunctional Nanotherapeutic Strategy Targeting Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Genotoxicity in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121432

Alfawaz M, Elmorsy EM, Alshammari AN, Hakim NA, Jawad NMM, Hassan SA, Fawzy MS, Esmaeel SE. Carvacrol-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles as a Multifunctional Nanotherapeutic Strategy Targeting Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Genotoxicity in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121432

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlfawaz, M., Ekramy M. Elmorsy, Ahmad Najem Alshammari, Noor A. Hakim, Najlaa M. M. Jawad, Soha A. Hassan, Manal S. Fawzy, and Safya E. Esmaeel. 2025. "Carvacrol-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles as a Multifunctional Nanotherapeutic Strategy Targeting Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Genotoxicity in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121432

APA StyleAlfawaz, M., Elmorsy, E. M., Alshammari, A. N., Hakim, N. A., Jawad, N. M. M., Hassan, S. A., Fawzy, M. S., & Esmaeel, S. E. (2025). Carvacrol-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles as a Multifunctional Nanotherapeutic Strategy Targeting Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Genotoxicity in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121432