5-HEPE Ameliorates Aging of Duck Ovarian Granulosa Cells by Targeting FOXM1 and Suppressing Oxidative Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Experiments and Sample Collection

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Determination of Oxidative Stress Indicators Content

2.4. Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining

2.5. Cell Viability Assay

2.6. mRNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.7. Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

2.8. RNA Sequencing

2.9. Targeted Lipidomics

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

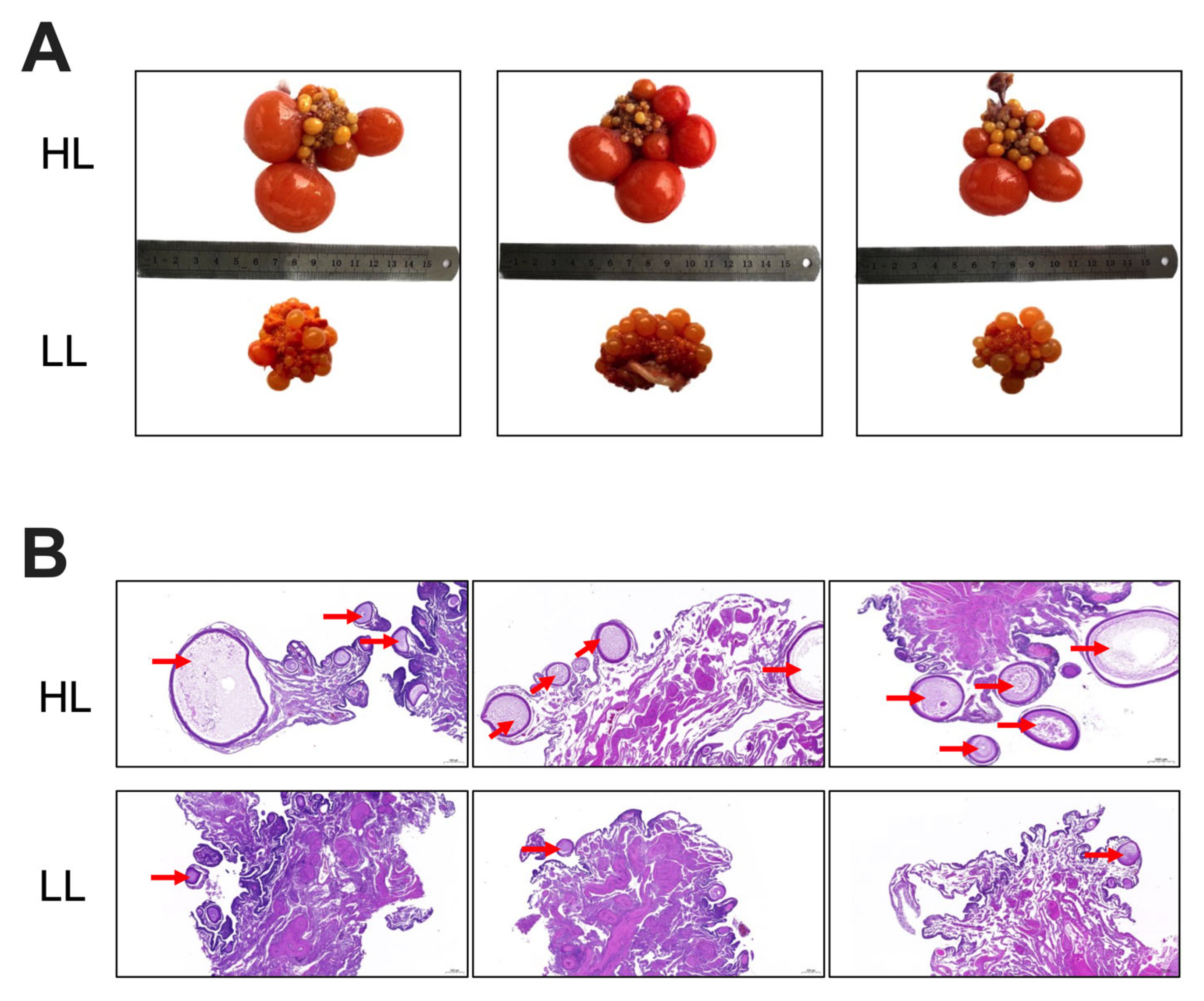

3.1. Ovarian Morphology of Laying Ducks with Different Egg Production Levels in the Late Laying Period

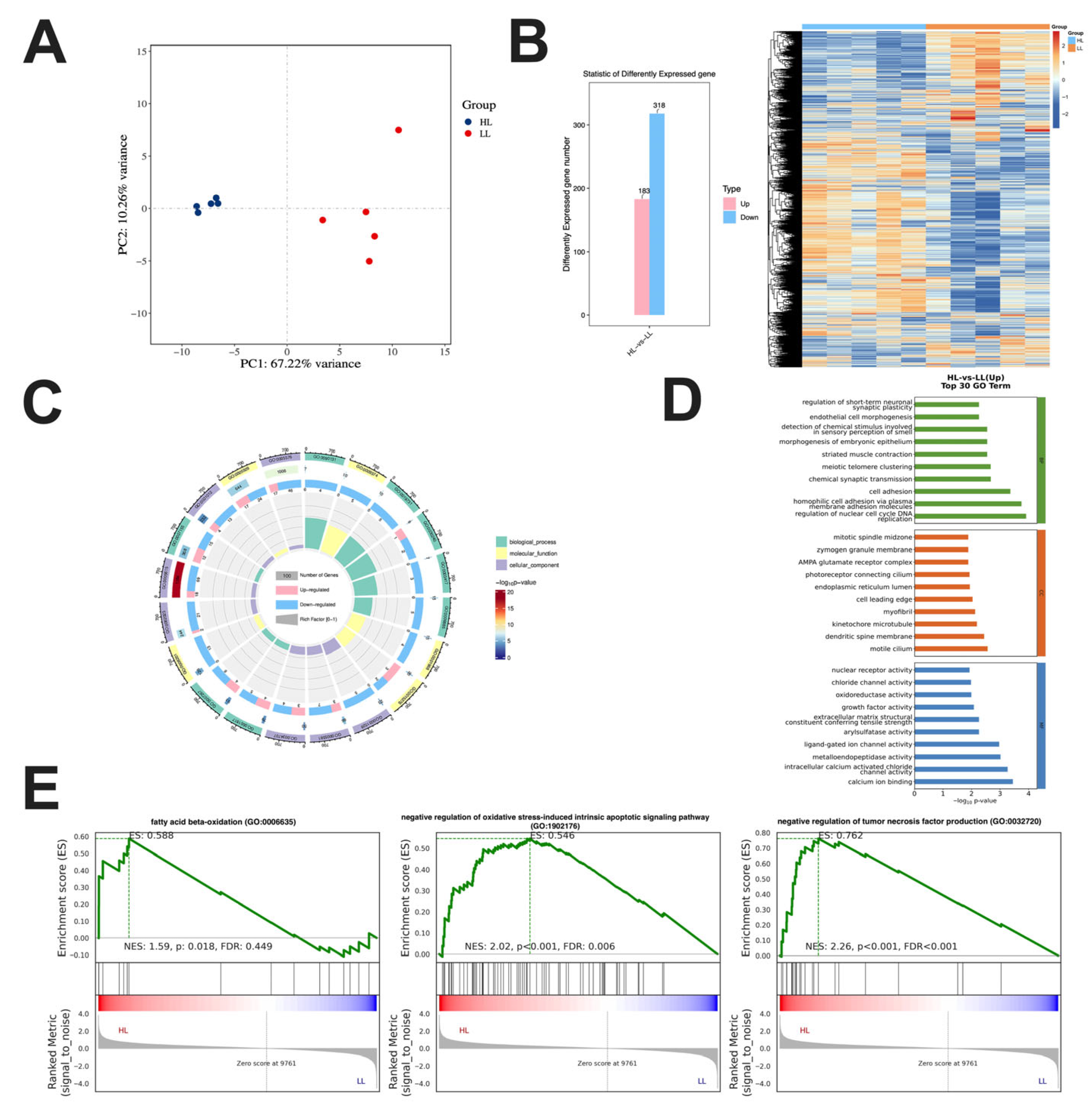

3.2. Transcriptome Analysis in the Ovary of Laying Ducks

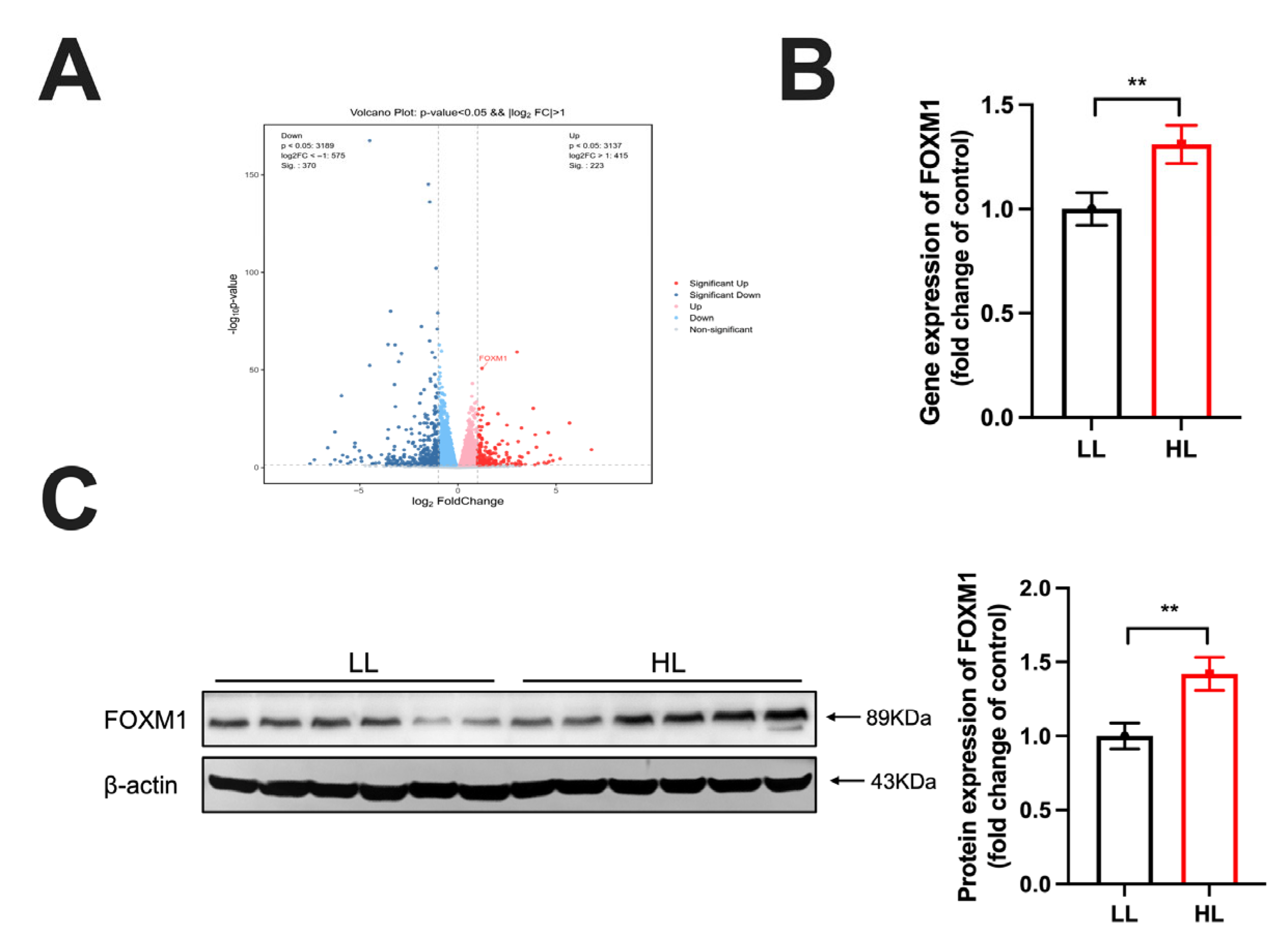

3.3. FOXM1 Was Upregulated in the Duck Ovary of the HL Group

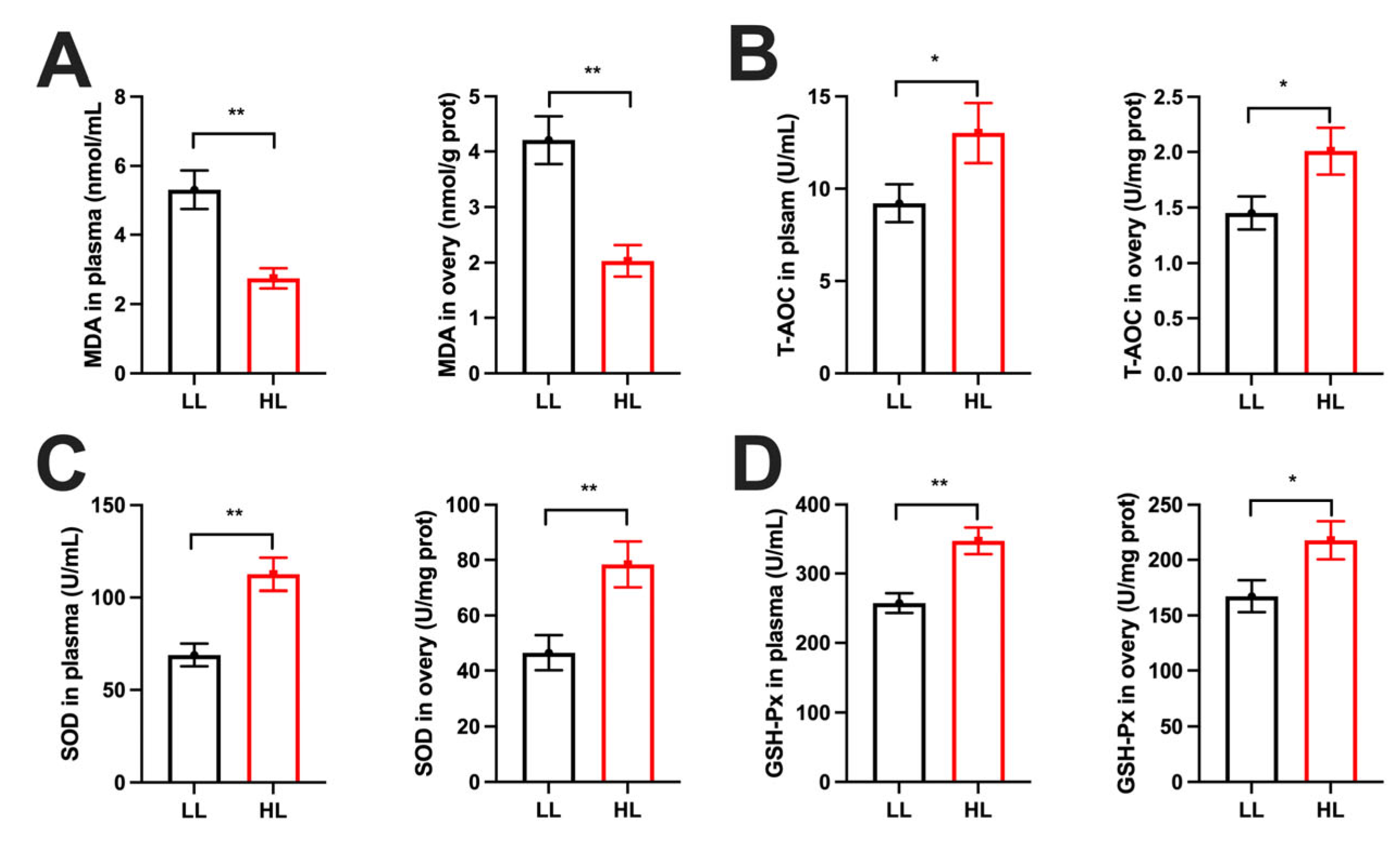

3.4. Differences in Oxidative Stress Between the HL and LL Group Ducks

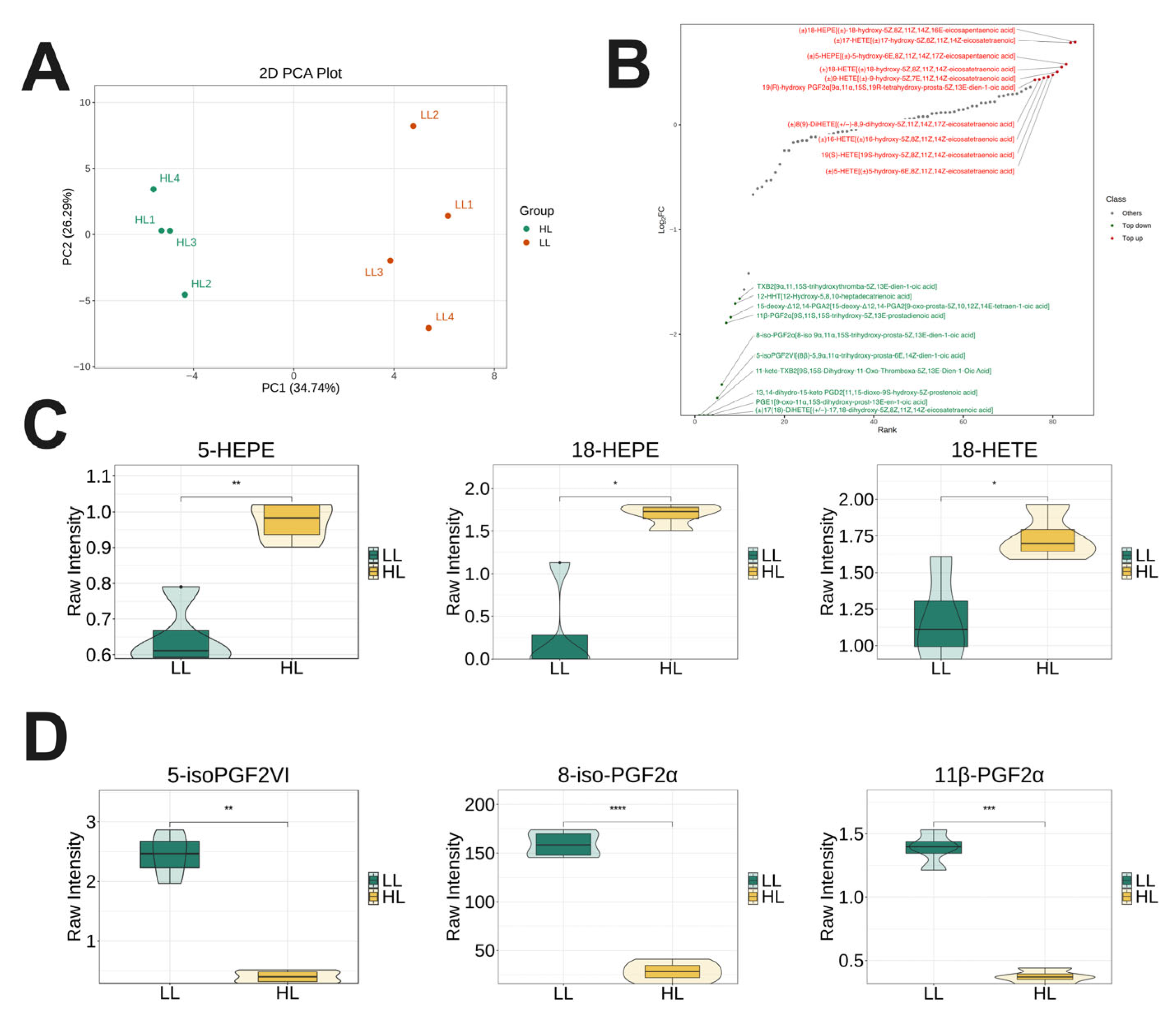

3.5. Targeted Lipidomics Analysis in Plasma of Laying Ducks

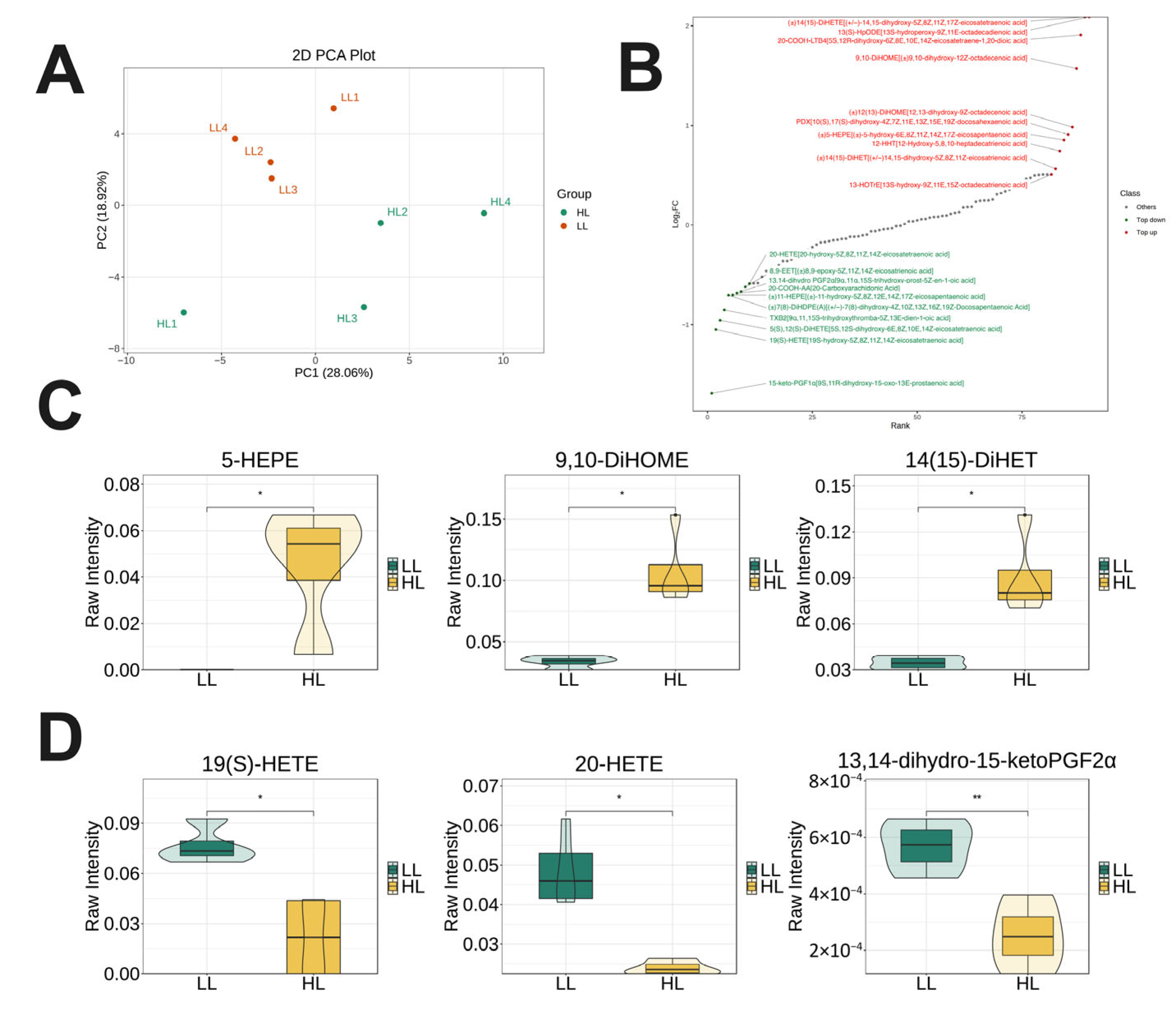

3.6. Targeted Lipidomics Analysis in the Ovary of Laying Ducks

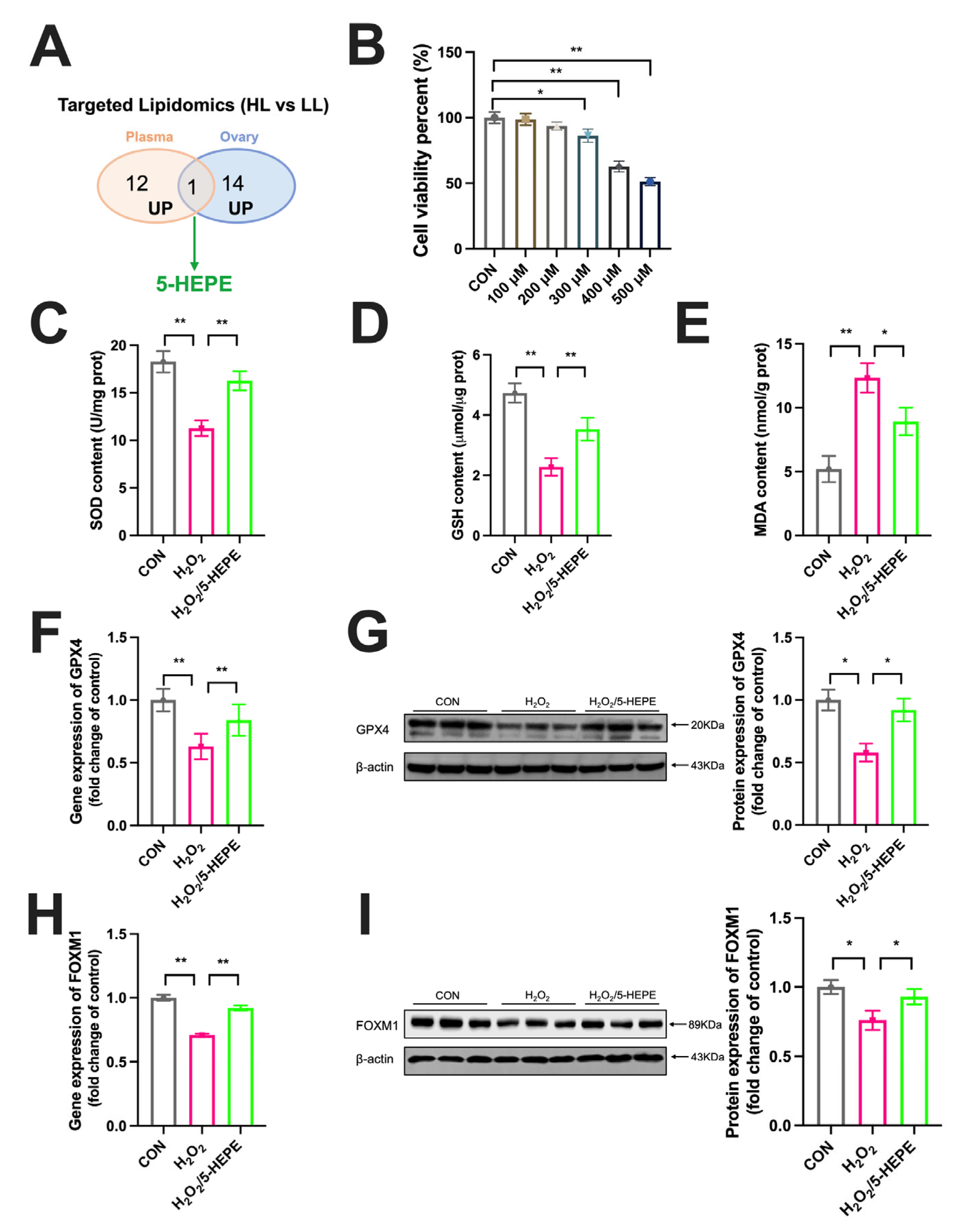

3.7. 5-HEPE Alleviated Oxidative Stress and Upregulated FOXM1 Expression in KGN Cells

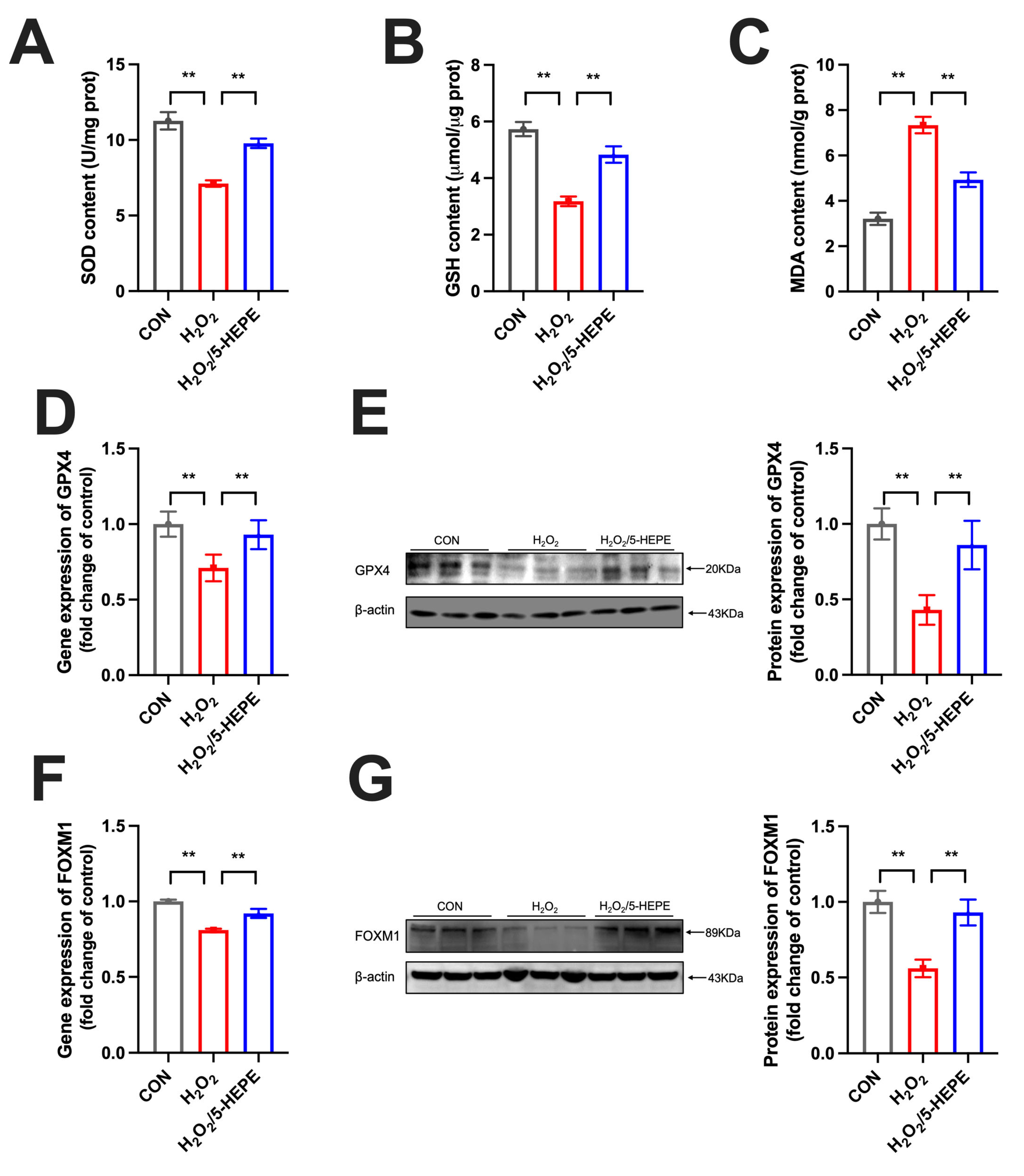

3.8. 5-HEPE Alleviated Oxidative Stress and Upregulated FOXM1 Expression in Ovarian GCs of Laying Ducks

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnson, P.A.; Stephens, C.S.; Giles, J.R. The domestic chicken: Causes and consequences of an egg a day. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 816–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.L. Ovarian follicle selection and granulosa cell differentiation. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoop, D.; Cobo, A.; Silber, S. Fertility preservation for age-related fertility decline. Lancet 2014, 384, 1311–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Geng, X.; Zheng, W.; Tang, J.; Xu, B.; Shi, Q. Current understanding of ovarian aging. Sci. China Life Sci. 2012, 55, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Liu, J.; Luo, A.; Wang, S. The stromal microenvironment and ovarian aging: Mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. J. Ovarian Res. 2023, 16, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, J.C.; Banito, A.; Wuestefeld, T.; Georgilis, A.; Janich, P.; Morton, J.P.; Athineos, D.; Kang, T.W.; Lasitschka, F.; Andrulis, M.; et al. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabbs, M.; Leng, S.; Devassy, J.G.; Monirujjaman, M.; Aukema, H.M. Advances in Our Understanding of Oxylipins Derived from Dietary PUFAs. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 513–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, B.M.; McNell, E.E.; Edin, M.L.; Ferguson, K.K. Inflammation and oxidative stress as mediators of the impacts of environmental exposures on human pregnancy: Evidence from oxylipins. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 239, 108181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilroy, D.W.; Edin, M.L.; De Maeyer, R.P.; Bystrom, J.; Newson, J.; Lih, F.B.; Stables, M.; Zeldin, D.C.; Bishop-Bailey, D. CYP450-derived oxylipins mediate inflammatory resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E3240–E3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Liu, D.; Wang, L. Role of oxylipins in ovarian function and disease: A comprehensive review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 178, 117242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalaifah, H.S.; Ibrahim, D.; Kamel, A.E.; Al-Nasser, A.; Abdelwarith, A.A.; Roushdy, E.M.; Sheraiba, N.I.; Shafik, B.M.; El-Badry, S.M.; Younis, E.M.; et al. Enhancing impact of dietary nano formulated quercetin on laying performance: Egg quality, oxidative stability of stored eggs, intestinal immune and antioxidants related genes expression. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Lin, J.; Mao, J.; Pan, T.; Wang, J.; Xu, H.; et al. ALOX5 contributes to glioma progression by promoting 5-HETE-mediated immunosuppressive M2 polarization and PD-L1 expression of glioma-associated microglia/macrophages. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e009492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Suo, X.; Fan, G.; Yang, X. 5-HEPE reduces obesity and insulin resistance by promoting adipose tissue browning through GPR119/AMPK/PGC1alpha activation. Life Sci. 2023, 323, 121703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Otin, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, J.C.; Vaz, S.; Logarinho, E. Mitotic Dysfunction Associated with Aging Hallmarks. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 1002, 153–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macedo, J.C.; Vaz, S.; Bakker, B.; Ribeiro, R.; Bakker, P.L.; Escandell, J.M.; Ferreira, M.G.; Medema, R.; Foijer, F.; Logarinho, E. FoxM1 repression during human aging leads to mitotic decline and aneuploidy-driven full senescence. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, J.M. The bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay for protein quantitation. Methods Mol. Biol. 1994, 32, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.; Macedo, J.C.; Costa, M.; Ustiyan, V.; Shindyapina, A.V.; Tyshkovskiy, A.; Gomes, R.N.; Castro, J.P.; Kalin, T.V.; Vasques-Novoa, F.; et al. In vivo cyclic induction of the FOXM1 transcription factor delays natural and progeroid aging phenotypes and extends healthspan. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calcinotto, A.; Kohli, J.; Zagato, E.; Pellegrini, L.; Demaria, M.; Alimonti, A. Cellular Senescence: Aging, Cancer, and Injury. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1047–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Otin, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Pan, H.; Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Shi, H.; Ge, C. Interacting Networks of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian Axis Regulate Layer Hens Performance. Genes 2023, 14, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, E.Y.; Wang, D.H.; Chen, Y.F.; Zhou, R.Y.; Chen, H.; Huang, R.L. The relationship between the mTOR signaling pathway and ovarian aging in peak-phase and late-phase laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.W.; Stok, J.E.; Vidal, J.D.; Corbin, C.J.; Huang, Q.; Hammock, B.D.; Conley, A.J. Cytochrome p450-dependent lipid metabolism in preovulatory follicles. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 5097–5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, M.E.; Arias-Torres, A.J.; Zelarayan, L.I. Role of arachidonic acid cascade in Rhinella arenarum oocyte maturation. Zygote 2015, 23, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, F.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Kong, X.; Shu, C.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Y. The role of oxidative stress in ovarian aging: A review. J. Ovarian Res. 2022, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orisaka, M.; Mizutani, T.; Miyazaki, Y.; Shirafuji, A.; Tamamura, C.; Fujita, M.; Tsuyoshi, H.; Yoshida, Y. Chronic low-grade inflammation and ovarian dysfunction in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome, endometriosis, and aging. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1324429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.L.; Kong, L.; Zhao, A.H.; Ge, W.; Yan, Z.H.; Li, L.; De Felici, M.; Shen, W. Inflammatory cytokines as key players of apoptosis induced by environmental estrogens in the ovary. Environ. Res. 2021, 198, 111225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, T.; Liu, J.; Zeng, T.; Chen, L.; Tian, Y.; Xu, W.; Lu, L. New insights into ovarian regression-related mitochondrial dysfunction in the late-laying period. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 104938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Qi, J.; Tao, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Huang, R.; Liao, Y.; Yue, J.; Liu, W.; Zhao, H.; Yin, H.; et al. Elevated levels of arachidonic acid metabolites in follicular fluid of PCOS patients. Reproduction 2020, 159, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yan, G.; Lei, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Gong, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, H.; Chen, H.; Zhou, Y.; et al. The SP1-12LOX axis promotes chemoresistance and metastasis of ovarian cancer. Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Ju, X.; Tan, Y. Treatment of Circadian Disorder with Premature Ovarian Insufficiency With the Nourishing Yin and Tonifying Yang Sequential Method with Femoston. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2022, 28, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hagihara, M.; Yamashita, M.; Ariyoshi, T.; Eguchi, S.; Minemura, A.; Miura, D.; Higashi, S.; Oka, K.; Nonogaki, T.; Mori, T.; et al. Clostridium butyricum-induced omega-3 fatty acid 18-HEPE elicits anti-influenza virus pneumonia effects through interferon-lambda upregulation. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, M. Icosapent ethyl in cardiovascular prevention: Resolution of inflammation through the eicosapentaenoic acid-resolvin E1-ChemR23 axis. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 247, 108439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onodera, T.; Fukuhara, A.; Shin, J.; Hayakawa, T.; Otsuki, M.; Shimomura, I. Eicosapentaenoic acid and 5-HEPE enhance macrophage-mediated Treg induction in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montuschi, P.; Curro, D.; Ragazzoni, E.; Preziosi, P.; Ciabattoni, G. Anaphylaxis increases 8-iso-prostaglandin F2alpha release from guinea-pig lung in vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 365, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoda, T.; Kikuchi, K.; Miki, Y.; Onodera, Y.; Hata, S.; Takagi, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Hirakawa, H.; Ishida, T.; Suzuki, T.; et al. 11beta-Prostaglandin F2alpha, a bioactive metabolite catalyzed by AKR1C3, stimulates prostaglandin F receptor and induces slug expression in breast cancer. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2015, 413, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, H.; Hu, J.; Meng, J.; Lv, H.; Yang, F.; Wang, M.; Liu, R.; Wu, W.; Hou, D.; et al. Plasma oxidative lipidomics reveals signatures for sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 551, 117616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Wang, J.; Feng, J. Aspirin resistance mediated by oxidative stress-induced 8-Isoprostaglandin F2. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2019, 44, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagahora, N.; Yamada, H.; Kikuchi, S.; Hakozaki, M.; Yano, A. Nrf2 Activation by 5-lipoxygenase Metabolites in Human Umbilical Vascular Endothelial Cells. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephensen, C.B.; Armstrong, P.; Newman, J.W.; Pedersen, T.L.; Legault, J.; Schuster, G.U.; Kelley, D.; Vikman, S.; Hartiala, J.; Nassir, R.; et al. ALOX5 gene variants affect eicosanoid production and response to fish oil supplementation. J. Lipid Res. 2011, 52, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.M.; Sha, M.; Lu, Z.; Wong, G.G. Molecular analysis of a novel winged helix protein, WIN. Expression pattern, DNA binding property, and alternative splicing within the DNA binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 19827–19836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Kelly, T.F.; Samadani, U.; Lim, L.; Rubio, S.; Overdier, D.G.; Roebuck, K.A.; Costa, R.H. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 3/fork head homolog 11 is expressed in proliferating epithelial and mesenchymal cells of embryonic and adult tissues. Mol. Cell Biol. 1997, 17, 1626–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korver, W.; Roose, J.; Clevers, H. The winged-helix transcription factor Trident is expressed in cycling cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 1715–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Raychaudhuri, P.; Costa, R.H. Chk2 mediates stabilization of the FoxM1 transcription factor to stimulate expression of DNA repair genes. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.K.; Smith, D.K.; Leung, W.Y.; Cheung, A.M.; Lam, E.W.; Dimri, G.P.; Yao, K.M. FoxM1c counteracts oxidative stress-induced senescence and stimulates Bmi-1 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 16545–16553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xuan, Y.; Shen, M.; Hu, X.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Tan, F. Thiostrepton induces oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and ferroptosis in HaCaT cells. Cell Signal 2024, 121, 111285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, N.; Otsu, M.; Mizutani, Y.; Ishitsuka, A.; Mizukami, Y.; Inoue, S. The glycoprotein GPNMB protects against oxidative stress through enhanced PI3K/AKT signaling in epidermal keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target Genes | Accession Number | Primer Sequences (5′–3′) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | |||

| FOXM1 | NM_001243088 | F: GCAGCAGAAACGACCGAATC | R: GGTCTTGGGGTGGGAGATTG |

| GPX4 | NM_001039847 | F: GAAGATCCAACCCAAGGGCA | R: GACGGTGTCCAAACTTGGTG |

| β-actin | NM_001101 | F: AGACCTGTACGCCAACACAG | R: CCTCGGCCACATTGTGAACT |

| Duck | |||

| FOXM1 | XM_072043035 | F: TGTTTAAGCAGCAAAAGCGACA | R: GGGGACAACCAGTCATCCAG |

| GPX4 | XM_038169022 | F: GTAGACCTGCTCATCTCGCC | R: GGCTTGAAGACAGACCGTCA |

| β-actin | NM_001310421 | F: CGGACTGTTACCAACACCCA | R: GCCTTCACAGAGGCGAGTAA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zong, Y.; Liu, J.; Xu, W.; Gu, T.; Tian, Y.; Chen, L.; Zeng, T.; Lu, L. 5-HEPE Ameliorates Aging of Duck Ovarian Granulosa Cells by Targeting FOXM1 and Suppressing Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121425

Zong Y, Liu J, Xu W, Gu T, Tian Y, Chen L, Zeng T, Lu L. 5-HEPE Ameliorates Aging of Duck Ovarian Granulosa Cells by Targeting FOXM1 and Suppressing Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121425

Chicago/Turabian StyleZong, Yibo, Jinyu Liu, Wenwu Xu, Tiantian Gu, Yong Tian, Li Chen, Tao Zeng, and Lizhi Lu. 2025. "5-HEPE Ameliorates Aging of Duck Ovarian Granulosa Cells by Targeting FOXM1 and Suppressing Oxidative Stress" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121425

APA StyleZong, Y., Liu, J., Xu, W., Gu, T., Tian, Y., Chen, L., Zeng, T., & Lu, L. (2025). 5-HEPE Ameliorates Aging of Duck Ovarian Granulosa Cells by Targeting FOXM1 and Suppressing Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121425