Protective Effects of Thyme Leaf Extract Against Particulate Matter-Induced Pulmonary Injury in Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Husbandry

- Intact control: Distilled water (10 mL/kg, p.o.) + saline (0.1 mL/kg, intranasal)

- PM2.5 control: Distilled water (10 mL/kg, p.o.) + PM2.5 (1 mg/kg, intranasal)

- DEXA: DEXA 0.75 mg/kg (11.40 mg/kg as DEXA-water soluble, p.o.) + PM2.5 (1 mg/kg, intranasal)

- TV200: TV 200 mg/kg (p.o.) + PM2.5 (1 mg/kg, intranasal)

- TV100: TV 100 mg/kg (p.o.) + PM2.5 (1 mg/kg, intranasal)

- TV50: TV 50 mg/kg (p.o.) + PM2.5 (1 mg/kg, intranasal)

2.2. Induction of Pulmonary Injury by PM2.5

2.3. Preparations and Administration of Test Articles

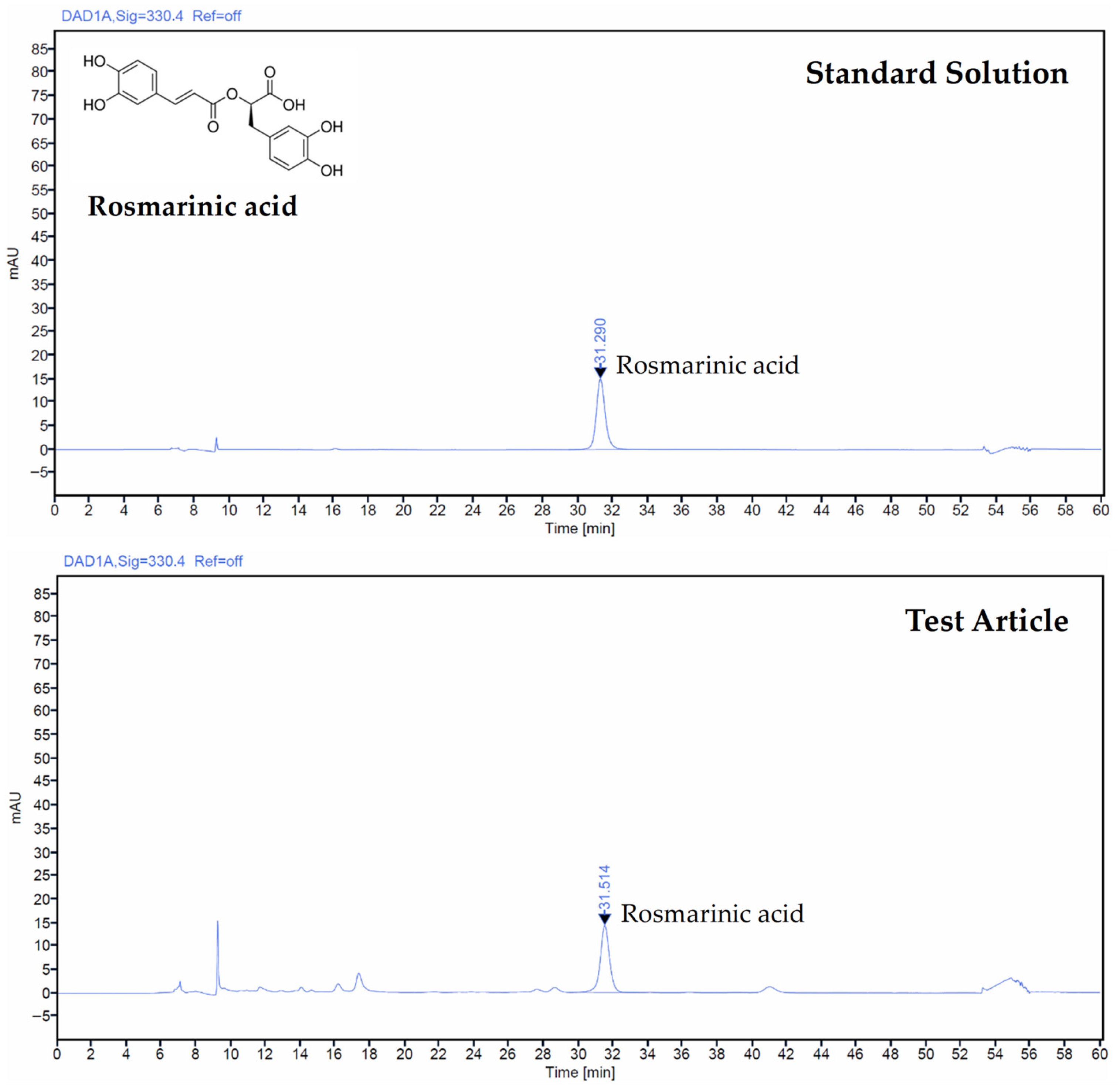

2.4. Determination of Test Article by HPLC

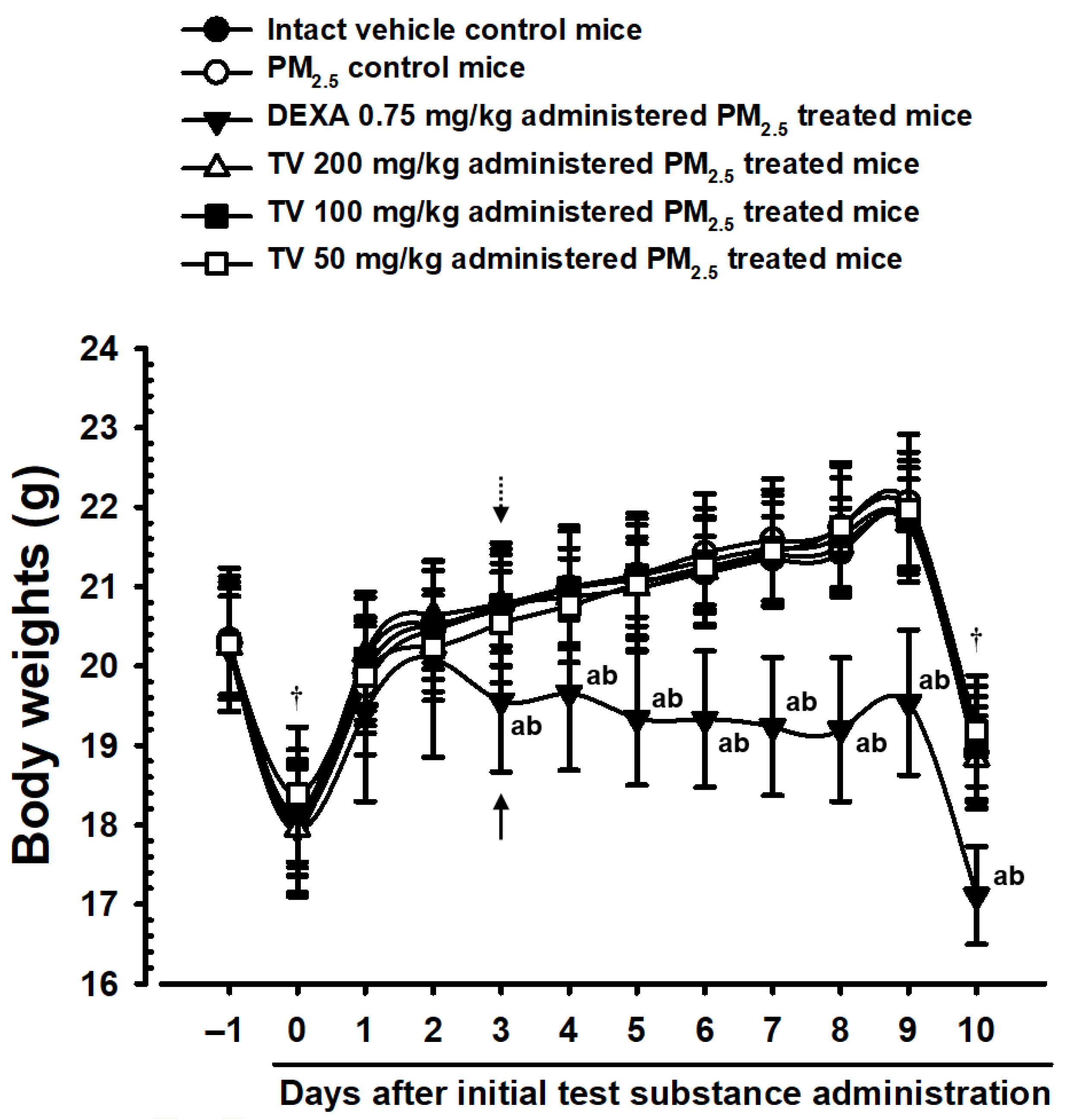

2.5. Changes in Body Weight

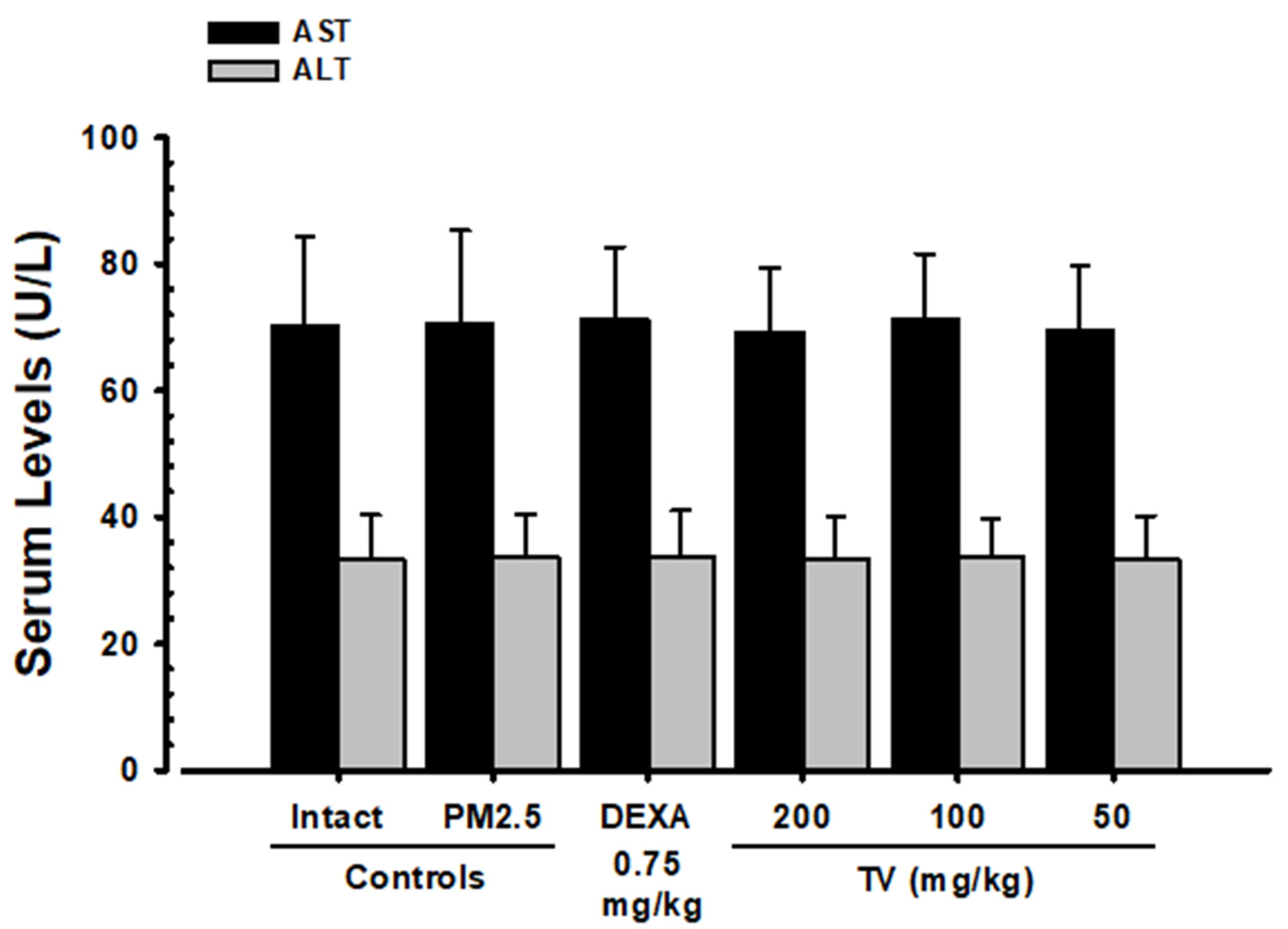

2.6. Serum AST and ALT Assessment

2.7. Lung Weight Measurement

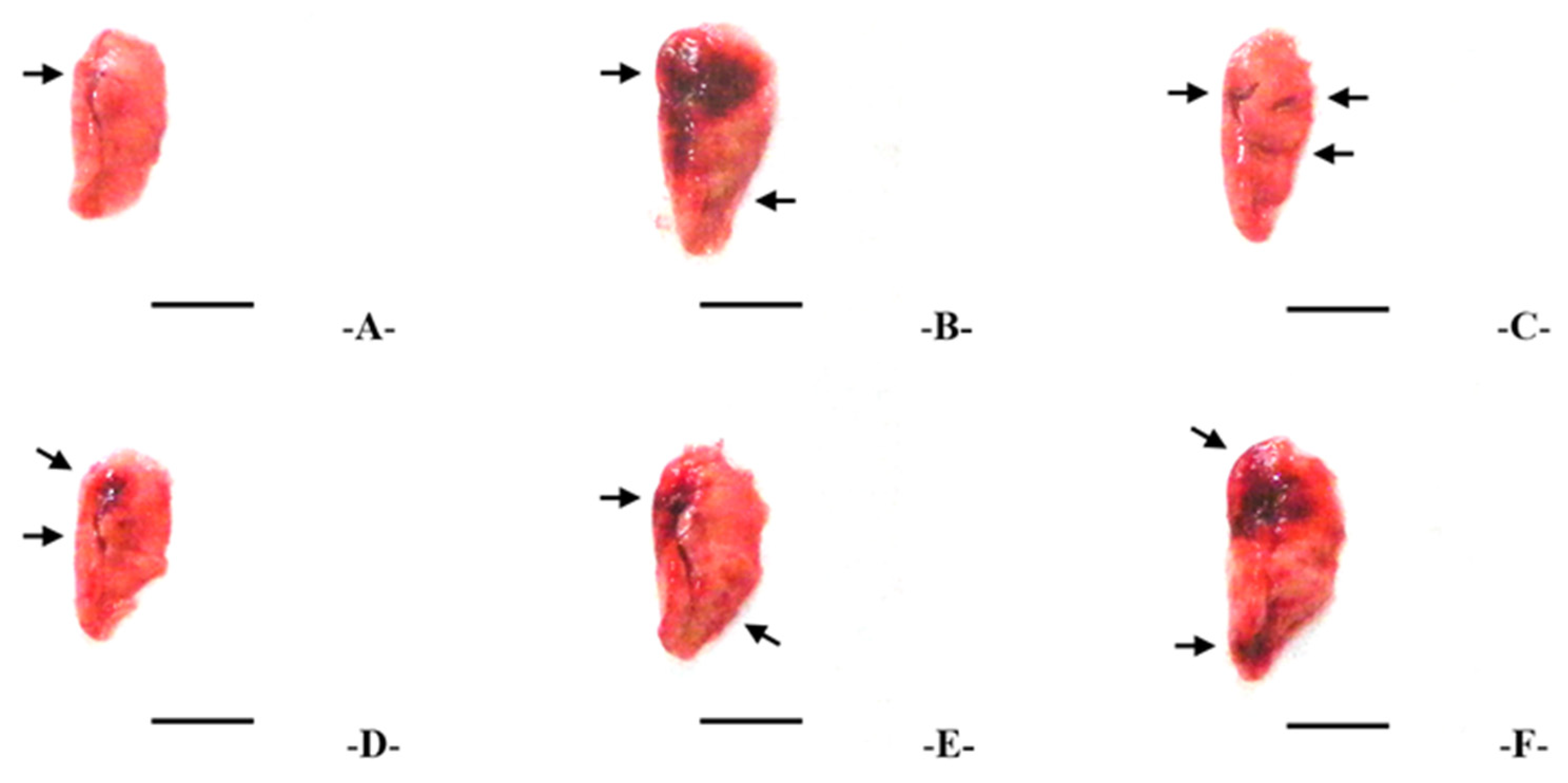

2.8. Lung Collection and Gross Examination

2.9. BALF Collection and Cytology

2.10. Lung Homogenate Preparation

2.11. Quantification of Cytokines, MMP, Substance P and ACh

2.12. Lipid Peroxidation Assay

2.13. ROS Measurement

2.14. Assessment of Antioxidant Enzymes

2.15. Real-Time RT-PCR

2.16. Histopathology

2.17. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Rosmarinic Acid Content in TV Extract

3.2. Body Weight Changes

3.3. Gross Lung Inspections and Weights

3.4. BALF Cytology

3.5. Changes in AST and ALT Levels

3.6. Lung Cytokine Levels

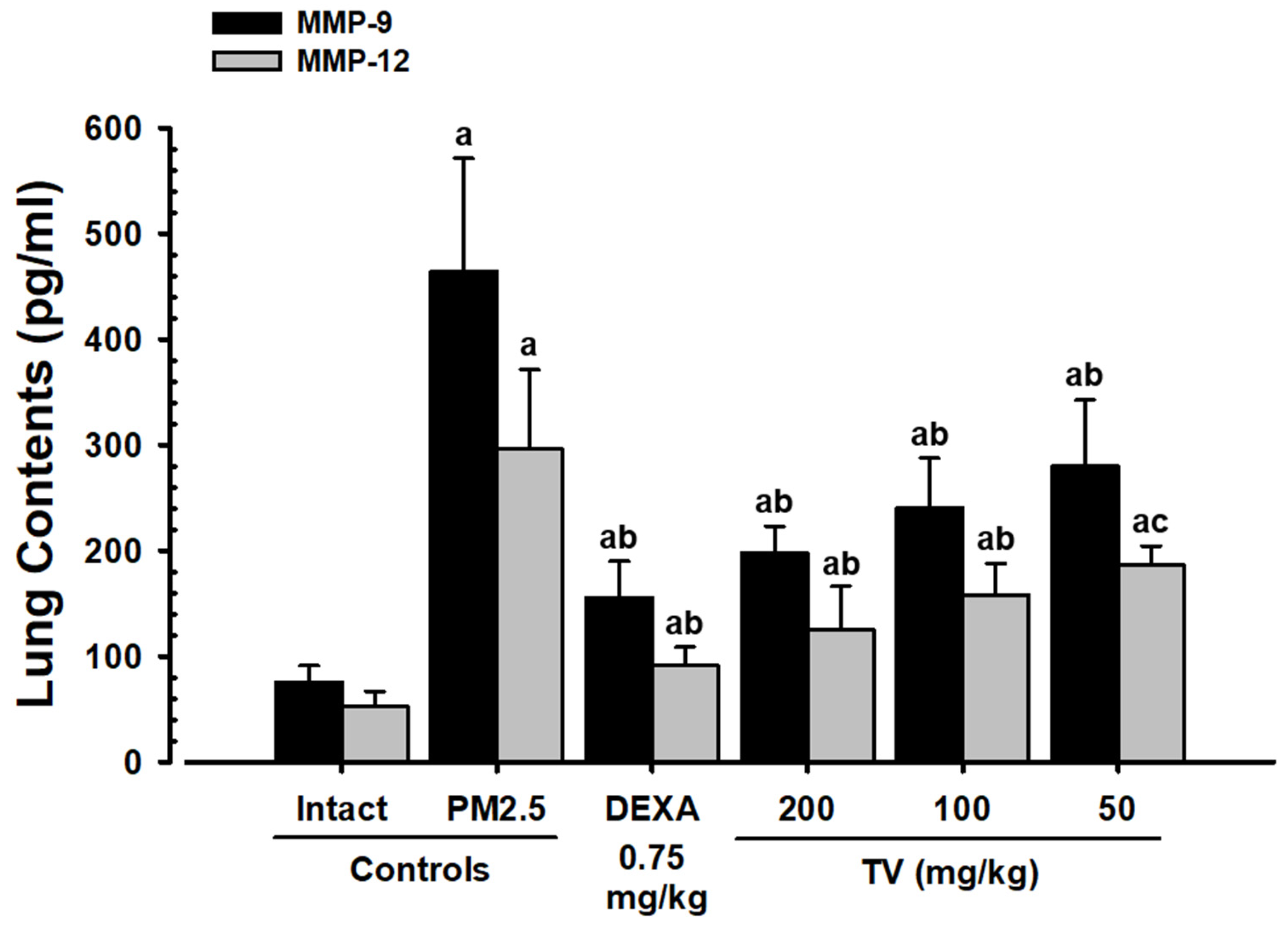

3.7. MMP-9 and MMP-12 Contents

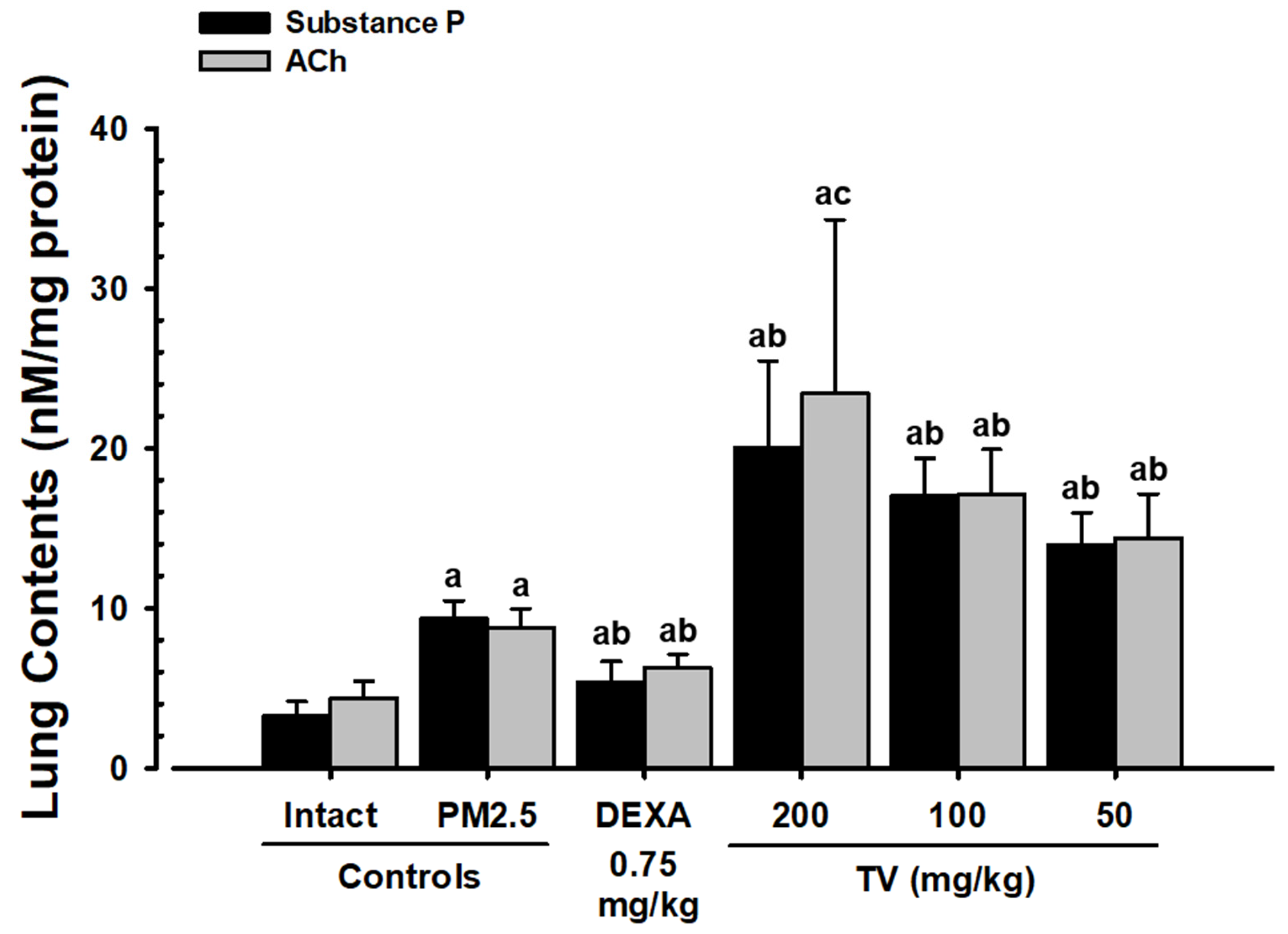

3.8. Lung Substance P and ACh Content

3.9. Lung Lipid Peroxidation and Antioxidant Defense

3.10. Mucus Production Genes

3.11. Oxidative Stress- and Inflammation-Related Genes

3.12. Apoptosis-Related Genes

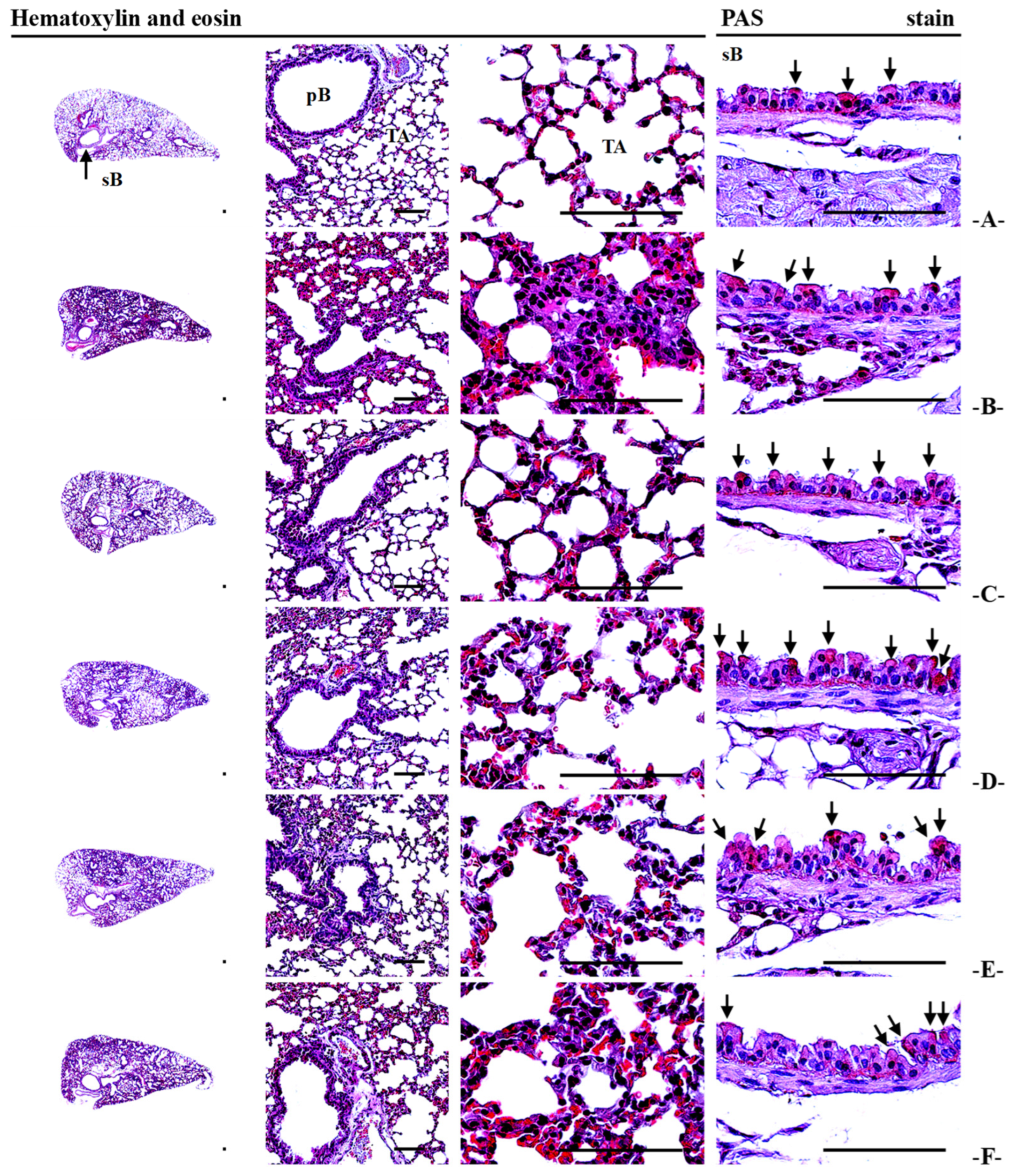

3.13. Lung Histopathology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACh | Acetylcholine |

| ALT | Alanine transaminase |

| ASA | Alveolar surface area |

| AST | Aspartate transaminase |

| BALF | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid |

| Bax | BCL2 associated x |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CXCL-1 | Chemokine (C-X-C Motif) Ligand 1 |

| CXCL-2 | Chemokine (C-X-C Motif) Ligand 2 |

| DCFDA | Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate |

| DEXA | Dexamethasone |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MMPs | Matrix metalloproteinases |

| MUC5AC | Mucin 5AC |

| MUC5B | Mucin 5B |

| NF-κB | Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| p38 MAPK | p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| PAS | Periodic acid-Schiff |

| PI3K/Akt | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Protein kinase B |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| TV | Thyme (Thyme vulgaris L.) leaf extract |

References

- Fernando, I.P.S.; Jayawardena, T.U.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, W.W.; Vaas, A.P.J.P.; De Silva, H.I.C.; Abayaweera, G.S.; Nanayakkara, C.M.; Abeytunga, D.T.U.; Lee, D.S.; et al. Beijing urban particulate matter-induced injury and inflammation in human lung epithelial cells and the protective effects of fucosterol from Sargassum binderi (Sonder ex J. Agardh). Environ. Res. 2019, 172, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Ku, S.K.; Kim, J.E.; Cho, S.H.; Song, G.Y.; Bae, J.S. Inhibitory effects of protopanaxatriol type ginsenoside fraction (Rgx365) on particulate matter-induced pulmonary injury. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 2019, 82, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Ku, S.K.; Kim, J.E.; Cho, S.H.; Song, G.Y.; Bae, J.S. Inhibitory effects of black ginseng on particulate matter-induced pulmonary injury. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2019, 47, 1237–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, G.; Guo, J.; Yuan, H.; Zhao, C. The compositions, sources, and size distribution of the dust storm from China in spring of 2000 and its impact on the global environment. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2001, 46, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Primbs, T.; Tao, S.; Simonich, S.L. Atmospheric particulate matter pollution during the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 5314–5320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.F.; He, L.Y.; Hu, M.; Zhang, Y.H. Annual variation of particulate organic compounds in PM2.5 in the urban atmosphere of Beijing. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 2449–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Zhang, B.; Bai, Y. A systematic analysis of PM2.5 in Beijing and its sources from 2000 to 2012. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 124, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Pereira, A.M.; Morais-Almeida, M. Asthma costs and social impact. Asthma Res. Pract. 2017, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Huang, L.; Gao, S.; Gao, S.; Wang, L. Measurements of PM10 and PM2.5 in urban area of Nanjing, China and the assessment of pulmonary deposition of particle mass. Chemosphere 2002, 48, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaumann, F.; Borm, P.J.; Herbrich, A.; Knoch, J.; Pitz, M.; Schins, R.P.; Luettig, B.; Hohlfeld, J.M.; Heinrich, J.; Krug, N. Metal-rich ambient particles (particulate matter 2.5) cause airway inflammation in healthy subjects. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 170, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, R.; Liu, H. The acute pulmonary toxicity in mice induced by Staphylococcus aureus, particulate matter, and their combination. Exp. Anim. 2019, 68, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, R.; De Berardis, B.; Paoletti, L.; Guastadisegni, C. Inflammatory mediators induced by coarse (PM2.5-10) and fine (PM2.5) urban air particles in RAW 264.7 cells. Toxicology 2003, 183, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubashynskaya, N.V.; Bokatyi, A.N.; Skorik, Y.A. Dexamethasone conjugates: Synthetic approaches and medical prospects. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, B.G.; Park, S.M.; Choi, Y.W.; Ku, S.K.; Cho, I.J.; Kim, Y.W.; Byun, S.H.; Park, C.A.; Park, S.J.; Na, M.; et al. Effects of Pelargonium sidoides and Coptis Rhizoma 2 : 1 mixed formula (PS + CR) on ovalbumin-induced asthma in mice. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2020, 2020, 9135637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, C.H.; Fan, Y.J.; Nguyen, T.V.; Song, C.H.; Chai, O.H. Mangiferin alleviates ovalbumin-induced allergic rhinitis via Nrf2/HO-1/NF-κB signaling pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Liu, H.; Fan, X.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, Y. Effect of San’ao decoction on aggravated asthma mice model induced by PM2.5 and TRPA1/TRPV1 expressions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 236, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.S.; Park, S.I.; Choi, S.H.; Song, C.H.; Park, S.J.; Shin, Y.K.; Han, C.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Ku, S.K. Single oral dose toxicity test of blue honeysuckle concentrate in mice. Toxicol. Res. 2015, 31, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devipriya, D.; Gowri, S.; Nideesh, T.R. Hepatoprotective effect of Pterocarpus marsupium against carbon tetrachloride induced damage in albino rats. Anc. Sci. Life. 2007, 27, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central]

- Figueira, L.W.; de Oliveira, J.R.; Camargo, S.E.A.; de Oliveira, L.D. Curcuma longa L. (turmeric), Rosmarinus officinalis L. (rosemary), and Thymus vulgaris L. (thyme) extracts aid murine macrophages (RAW 264.7) to fight Streptococcus mutans during in vitro infection. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 2269–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Qudah, J.M. Contents of chlorophyll and carotenoid pigments in common thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.). World Appl. Sci. J. 2014, 29, 1277–1281. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, J.R.; de Jesus, D.; Figueira, L.W.; de Oliveira, F.E.; Soares, C.P.; Camargo, S.E.; Jorge, A.O.; de Oliveira, L.D. Biological activities of Rosmarinus officinalis L. (rosemary) extract as analyzed in microorganisms and cells. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 242, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, J.R.; de Jesus Viegas, D.; Martins, A.P.R.; Carvalho, C.A.T.; Soares, C.P.; Camargo, S.E.A.; Jorge, A.O.C.; de Oliveira, L.D. Thymus vulgaris L. extract has antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects in the absence of cytotoxicity and genotoxicity. Arch. Oral Biol. 2017, 82, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Newary, S.A.; Shaffie, N.M.; Omer, E.A. The protection of Thymus vulgaris leaves alcoholic extract against hepatotoxicity of alcohol in rats. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2017, 10, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagoor Meeran, M.F.; Javed, H.; Al Taee, H.; Azimullah, S.; Ojha, S.K. Pharmacological properties and molecular mechanisms of thymol: Prospects for its therapeutic potential and pharmaceutical development. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waheed, M.; Hussain, M.B.; Saeed, F.; Afzaal, M.; Ahmed, A.; Irfan, R.; Akram, N.; Ahmed, F.; Hailu, G.G. Phytochemical profiling and therapeutic potential of thyme (Thymus spp.): A medicinal herb. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 9893–9912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharangi, A.B.; Guha, S. Wonders of leafy spices: Medicinal properties ensuring human health. Sci. Int. 2013, 1, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dauqan, E.M.; Abdullah, A. Medicinal and functional values of thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) herb. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2017, 5, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, S.K.; Kim, J.W.; Cho, H.R.; Kim, K.Y.; Min, Y.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Park, J.H.; Seo, B.I.; Roh, S.S. Effect of β-glucan originated from Aureobasidium pullulans on asthma induced by ovalbumin in mouse. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2012, 35, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavutcu, M.; Canbolat, O.; Oztürk, S.; Olcay, E.; Ulutepe, S.; Ekinci, C.; Gökhun, I.H.; Durak, I. Reduced enzymatic antioxidant defense mechanism in kidney tissues from gentamicin-treated guinea pigs: Effects of vitamins E and C. Nephron 1996, 72, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamall, I.S.; Smith, J.C. Effects of cadmium on glutathione peroxidase, superoxidase dismutase and lipid peroxidation in the rat heart: A possible mechanism of cadmium cardiotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1985, 80, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosenbrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Xu, Q.; Jing, Y.; Agani, F.; Qian, X.; Carpenter, R.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.R.; Peiper, S.S.; Lu, Z.; et al. Reactive oxygen species regulate ERBB2 and ERBB3 expression via miR-199a/125b and DNA methylation. EMBO Rep. 2012, 13, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedlak, J.; Lindsay, R.H. Estimation of total, protein-bound, and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman’s reagent. Anal. Biochem. 1968, 25, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebi, H. Catalase. In Methods in Enzymatic Analysis; Bergmeyer, H.U., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Larry, W.O.; Ying, L. A simple method for clinical assay of superoxide dismutase. Clin. Chem. 1988, 34, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Rui, W.; Zhang, F.; Ding, W. PM2.5 induces Nrf2-mediated defense mechanisms against oxidative stress by activating PIK3/AKT signaling pathway in human lung alveolar epithelial A549 cells. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2013, 29, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ge, G.; Ba, Y.; Guo, Q.; Gao, T.; Chi, X.; et al. Involvement of EGF receptor signaling and NLRP12 inflammasome in fine particulate matter-induced lung inflammation in mice. Environ. Toxicol. 2017, 32, 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, R.R.; Elmahdy, M.K.; Suddek, G.M. Flavocoxid attenuates airway inflammation in ovalbumin-induced mouse asthma model. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 292, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.; Snider, T.A. Guidelines for collection and processing of lungs from aged mice for histological studies. Pathobiol. Aging Age-Related Dis. 2017, 7, 1313676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, D.K. What is the proper way to apply the multiple comparison test? Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2018, 71, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauder, D.C.; DeMars, C.E. An updated recommendation for multiple comparisons. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 2, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kok, T.M.; Engels, L.G.; Moonen, E.J.; Kleinjans, J.C. Inflammatory bowel disease stimulates formation of carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds. Gut 2005, 54, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.A., 3rd; Dockery, D.W. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: Lines that connect. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2006, 56, 709–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Xue, Y. Hydroxyl radical generation and oxidative stress in Carassius auratus liver, exposed to pyrene. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2008, 71, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Deng, F.; Hao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zheng, C.; Lv, H.; Lu, X.; Wei, H.; Huang, J.; Qin, Y.; et al. Fine particulate matter, temperature, and lung function in healthy adults: Findings from the HVNR study. Chemosphere 2014, 108, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, F.J.; Fussell, J.C. Size, source and chemical composition as determinants of toxicity attributable to ambient particulate matter. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 60, 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Fang, D.; Chen, B. Human health impact and economic effect for PM2.5 exposure in typical cities. Appl. Energy 2019, 249, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S.; Pope, C.A., 3rd; Brook, J.R.; Bhatnagar, A.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Holguin, F.; Hong, Y.; Luepker, R.V.; Mittleman, M.A.; et al. American heart association council on epidemiology and prevention, council on the kidney in cardiovascular disease, and council on nutrition, physical activity and metabolism. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010, 121, 2331–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Chang, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, W. Air pollution and lung cancer incidence in China: Who are faced with a greater effect? Environ. Int. 2019, 132, 105077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.J.; Senior, R.M. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 in lung remodeling. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2003, 28, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, P.J. Immunology of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, K.; Tran, L.; Jimenez, L.A.; Duffin, R.; Newby, D.E.; Mills, N.; MacNee, W.; Stone, V. Combustion-derived nanoparticles: A review of their toxicology following inhalation exposure. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2005, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, R.S.; Bevan, G.H.; Palanivel, R.; Das, L.; Rajagopalan, S. Oxidative stress pathways of air pollution mediated toxicity: Recent insights. Redox. Biol. 2020, 34, 101545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, A.; Santa-Helena, E.; De Falco, A.; de Paula, R.J.; Gioda, A.; Gioda, C.R. Toxicological effects of fine particulate matter (PM2.5): Health risks and associated systemic injuries-systematic review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A.; Pérez, M.; Romanelli, G.; Blustein, G. Thymol bioactivity: A review focusing on practical applications. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 9243–9269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, A.R.S.; Serrano, C.; Almeida, C.; Soares, A.; Rolim Lopes, V.; Sanches-Silva, A. Beyond thymol and carvacrol: Characterizing the phenolic profiles and antioxidant capacity of Portuguese oregano and thyme for food applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrou, S.; Bellou, M.G.; Papanikolaou, A.; Nakou, K.; Kontogianni, V.G.; Chatzikonstantinou, A.V.; Stamatis, H. Evaluation of antioxidant, antibacterial and enzyme-inhibitory properties of dittany and thyme extracts and their application in hydrogel preparation. BioChem 2024, 4, 166–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nekeety, A.A.; Mohamed, S.R.; Hathout, A.S.; Hassan, N.S.; Aly, S.E.; Abdel-Wahhab, M.A. Antioxidant properties of Thymus vulgaris oil against aflatoxin-induce oxidative stress in male rats. Toxicon 2011, 57, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocaña, A.; Reglero, G. Effects of thyme extract oils (from Thymus vulgaris, Thymus zygis, and Thymus hyemalis) on cytokine production and gene expression of oxLDL-stimulated THP-1-macrophages. J. Obes. 2012, 2012, 104706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kensara, O.A.; El-Sawy, N.A.; El-Shemi, A.G.; Header, E.A. Thymus vulgaris supplementation attenuates blood pressure and aorta damage in hypertensive rats. J. Med. Plants Res. 2013, 7, 669–676. [Google Scholar]

- Fahy, J.V.; Dickey, B.F. Airway mucus function and dysfunction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2233–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Groups | Total Cells | Total Leukocytes | Differential Counts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphocytes | Neutrophils | Eosinophils | Monocytes | |||

| Controls | ||||||

| Intact vehicle | 9.60 ± 2.95 | 6.10 ± 1.73 | 3.40 ± 1.17 | 1.15 ± 0.34 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 1.30 ± 0.87 |

| PM2.5 | 78.30 ± 12.36 c | 53.50 ± 13.18 c | 34.30 ± 10.08 c | 9.78 ± 2.82 c | 1.48 ± 0.23 c | 6.56 ± 1.43 a |

| Reference | ||||||

| DEXA | 18.60 ± 3.72 cd | 11.60 ± 2.41 cd | 7.30 ± 2.50 cd | 2.13 ± 0.40 cd | 0.04 ± 0.03 d | 1.95 ± 0.68 b |

| Test article–TV | ||||||

| 200 mg/kg | 33.80 ± 10.49 cd | 19.50 ± 4.86 cd | 12.70 ± 3.20 cd | 3.79 ± 1.11 cd | 0.17 ± 0.08 cd | 2.65 ± 0.76 b |

| 100 mg/kg | 44.30 ± 6.70 cd | 24.40 ± 3.84 cd | 15.20 ± 2.94 cd | 4.44 ± 0.80 cd | 0.67 ± 0.27 cd | 3.54 ± 1.09 ab |

| 50 mg/kg | 54.10 ± 7.55 cd | 29.50 ± 6.45 cd | 18.80 ± 4.98 ce | 5.38 ± 1.33 cd | 0.85 ± 0.22 cd | 4.33 ± 1.19 ab |

| Groups | Lung Contents (pg/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | IL-6 | CXCL1 | CXCL2 | |

| Controls | ||||

| Intact vehicle | 29.21 ± 8.72 | 27.88 ± 11.74 | 30.37 ± 10.35 | 16.88 ± 4.30 |

| PM2.5 | 228.82 ± 51.32 a | 427.08 ± 54.81 a | 340.54 ± 85.86 a | 195.53 ± 26.07 a |

| Reference | ||||

| DEXA | 65.37 ± 16.34 ab | 75.42 ± 13.54 ab | 113.70 ± 29.25 ab | 61.49 ± 20.30 ab |

| Test article—TV | ||||

| 200 mg/kg | 86.22 ± 17.23 ab | 130.08 ± 45.34 ab | 156.66 ± 28.26 ab | 89.69 ± 14.28 ab |

| 100 mg/kg | 106.55 ± 19.58 ab | 197.58 ± 57.64 ab | 187.38 ± 29.10 ab | 109.88 ± 18.15 ab |

| 50 mg/kg | 135.41 ± 18.90 ab | 262.57 ± 52.84 ab | 210.09 ± 35.64 ac | 124.70 ± 23.26 ab |

| Groups | Lung Contents (nM/mg Protein) | Lung Enzyme Activity (U/mg Protein) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA | ROS | GSH | SOD | CAT | |

| Controls | |||||

| Intact vehicle | 3.56 ± 1.34 | 23.31 ± 10.58 | 41.96 ± 12.99 | 322.80 ± 47.80 | 70.10 ± 13.24 |

| PM2.5 | 19.31 ± 2.80 a | 90.43 ± 10.05 a | 6.29 ± 1.93 d | 65.30 ± 19.27 d | 10.30 ± 2.11 d |

| Reference | |||||

| DEXA | 6.75 ± 1.70 bc | 41.35 ± 10.05 ac | 19.17 ± 3.97 de | 188.60 ± 41.95 de | 38.20 ± 12.77 de |

| Test article—TV | |||||

| 200 mg/kg | 8.92 ± 2.44 ac | 48.72 ± 11.29 ac | 15.95 ± 2.47 de | 166.10 ± 27.13 de | 30.80 ± 10.78 de |

| 100 mg/kg | 10.70 ± 2.18 ac | 59.25 ± 10.12 ac | 13.95 ± 2.21 de | 145.70 ± 29.81 de | 23.20 ± 7.71 de |

| 50 mg/kg | 12.36 ± 1.72 ac | 64.21 ± 12.31 ac | 12.47 ± 2.87 de | 120.00 ± 14.91 de | 18.90 ± 5.26 de |

| Groups | Controls | Reference | Test Article—TV | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact Vehicle | PM2.5 | DEXA | 200 mg/kg | 100 mg/kg | 50 mg/kg | |

| MUC5AC | 1.00 ± 0.05 | 4.96 ± 0.75 a | 2.19 ± 0.35 ab | 2.46 ± 0.42 ab | 2.87 ± 0.27 ab | 3.35 ± 0.63 ab |

| MUC5 B | 1.00 ± 0.07 | 2.85 ± 0.23 a | 1.76 ± 0.33 ab | 1.85 ± 0.25 ab | 2.01 ± 0.22 ab | 2.16 ± 0.24 ab |

| NF-κB | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 8.63 ± 0.89 a | 2.09 ± 0.41 ab | 3.93 ± 1.10 ab | 4.82 ± 1.08 ab | 5.87 ± 1.21 ab |

| p38 MAPK | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 7.27 ± 1.02 a | 2.72 ± 0.79 ab | 3.79 ± 0.87 ab | 4.33 ± 0.80 ab | 5.06 ± 0.90 ab |

| PTEN | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 0.27 ± 0.10 a | 0.70 ± 0.10 ab | 0.66 ± 0.12 ab | 0.60 ± 0.09 ab | 0.51 ± 0.05 ab |

| PI3 K | 1.00 ± 0.05 | 6.34 ± 1.06 a | 2.26 ± 0.74 ab | 2.69 ± 0.40 ab | 3.25 ± 0.75 ab | 4.07 ± 0.72 ab |

| Akt | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 5.09 ± 1.31 a | 1.74 ± 0.38 ab | 2.06 ± 0.47 ab | 2.36 ± 0.45 ab | 3.05 ± 0.42 ab |

| Bcl-2 | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 0.38 ± 0.07 a | 0.69 ± 0.14 ab | 0.60 ± 0.08 ab | 0.55 ± 0.08 ab | 0.50 ± 0.04 ab |

| Bax | 1.00 ± 0.05 | 6.93 ± 1.28 a | 2.67 ± 0.71 ab | 3.56 ± 0.75 ab | 3.72 ± 0.83 ab | 4.64 ± 0.70 ab |

| Groups | Mean ASA (%/mm2) | Mean Alveolar Septal Thickness (μm) | Mean Thickness of SB (μm) | Mean IF Cell Numbers Infiltrated in AR (×10 Cells/mm2) | PAS-Positive Cells on the SB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers (Cells/mm2) | Percentages (%/Epithelium) | |||||

| Controls | ||||||

| Intact vehicle | 82.66 ± 8.04 | 4.09 ± 1.46 | 13.71 ± 1.20 | 56.80 ± 12.19 | 24.00 ± 2.98 | 1.23 ± 0.44 |

| PM2.5 | 38.53 ± 6.10 a | 38.32 ± 3.41 d | 19.63 ± 1.46 d | 883.90 ± 168.40 d | 39.60 ± 3.75 d | 4.87 ± 0.68 d |

| Reference | ||||||

| DEXA | 72.16 ± 8.12 bc | 12.44 ± 4.89 de | 18.95 ± 2.77 d | 128.40 ± 31.00 de | 38.80 ± 7.44 d | 4.65 ± 0.99 d |

| Test article—TV | ||||||

| 200 mg/kg | 67.79 ± 8.16 ac | 15.97 ± 2.54 de | 28.08 ± 1.83 de | 193.60 ± 47.41 de | 84.60 ± 10.46 de | 20.00 ± 4.00 de |

| 100 mg/kg | 60.39 ± 7.96 ac | 19.14 ± 3.27 de | 25.88 ± 1.45 de | 331.00 ± 83.95 de | 63.80 ± 10.04 de | 12.84 ± 3.25 de |

| 50 mg/kg | 54.81 ± 5.57 ac | 27.78 ± 4.94 de | 23.81 ± 0.77 de | 583.00 ± 98.91 de | 53.00 ± 6.75 de | 7.56 ± 0.90 de |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.-K.; Bashir, K.M.I.; Park, H.-R.; Kwon, J.-G.; Choi, B.-R.; Choi, J.-S.; Ku, S.-K. Protective Effects of Thyme Leaf Extract Against Particulate Matter-Induced Pulmonary Injury in Mice. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1343. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14111343

Lee J-K, Bashir KMI, Park H-R, Kwon J-G, Choi B-R, Choi J-S, Ku S-K. Protective Effects of Thyme Leaf Extract Against Particulate Matter-Induced Pulmonary Injury in Mice. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(11):1343. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14111343

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jae-Kyoung, Khawaja Muhammad Imran Bashir, Hye-Rim Park, Jin-Gwan Kwon, Beom-Rak Choi, Jae-Suk Choi, and Sae-Kwang Ku. 2025. "Protective Effects of Thyme Leaf Extract Against Particulate Matter-Induced Pulmonary Injury in Mice" Antioxidants 14, no. 11: 1343. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14111343

APA StyleLee, J.-K., Bashir, K. M. I., Park, H.-R., Kwon, J.-G., Choi, B.-R., Choi, J.-S., & Ku, S.-K. (2025). Protective Effects of Thyme Leaf Extract Against Particulate Matter-Induced Pulmonary Injury in Mice. Antioxidants, 14(11), 1343. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14111343