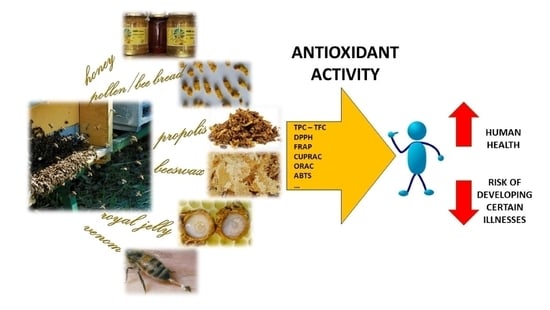

Antioxidant Activity in Bee Products: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Antioxidant Compounds in Bee Products

3. Determination of Antioxidant Compounds and Activity

4. Honey

5. Pollen and Bee Bread

6. Propolis

7. Beeswax

8. Royal Jelly

9. Bee Venom

10. In Vitro Determination of AOA

11. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crane, E. Bees and Beekeeping—Science, Practice and World Resources; Heinemann Newnes: Oxford, UK, 1990; p. 614. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov, S. Honey in medicine: A review. Bee Prod. Sci. 2017, 28. Available online: http://www.bee-hexagon.net/ (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Kocot, J.; Kiełczykowska, M.; Luchowska-Kocot, D.; Kurzepa, J.; Musik, I. Antioxidant potential of propolis, bee pollen, and royal jelly: Possible medical application. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2, 7074209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieliszek, M.; Piwowarek, K.; Kot, A.M.; Błażejak, S.; Chlebowska-Śmigiel, A.; Wolska, I. Pollen and bee bread as new health-oriented products: A review. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2018, 71, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badolato, M.; Carullo, G.; Cione, E.; Aiello, F.; Caroleo, M.C. From the hive: Honey, a novel weapon against cancer. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 142, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartkiene, E.; Lele, V.; Sakiene, V.; Zavistanaviciute, P.; Zokaityte, E.; Dauksiene, A.; Jagminas, P.; Klupsaite, D.; Bliznikas, S.; Ruzauskas, M. Variations of the antimicrobial, antioxidant, sensory attributes and biogenic amines content in Lithuania-derived bee products. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 118, 108793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viuda-Martos, M.; Ruiz-Navajas, Y.; Fernández-López, J.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.A. Functional properties of honey, propolis, and royal jelly. J. Food Sci. 2008, 73, R117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küçük, M.; Karaoğlu, S.; Ulusoy, E.; Baltacı, C.; Candan, F. Biological activities and chemical composition of three honeys of different types from Anatolia. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marco, G.; Gismondi, A.; Panzanella, L.; Canuti, L.; Impei, S.; Leonardi, D.; Canini, A. Botanical influence on phenolic profile and antioxidant level of Italian honeys. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 4042–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, H.E.; Xiaobo, Z.; Zhihua, L.; Jiyong, S.; Zhai, X.; Wang, S.; Mariod, A.A. Rapid prediction of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of Sudanese honey using Raman and Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2017, 226, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marco, G.; Manfredini, A.; Leonardi, D.; Canuti, L.; Impei, S.; Gismondi, A.; Canini, A. Geographical, botanical and chemical profile of monofloral Italian honeys as food quality guarantee and territory brand. Plant Biosyst. 2016, 151, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, S.; Beuxa, M.R.; Hoffmann Ribania, R.; Zambiazi, R.C. Stingless bee honey: Quality parameters, bioactive compounds, healthpromotion properties and modification detection strategies. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2018, 81, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, M.; Trusheva, B.; Bankova, V. Propolis of stingless bees: A phytochemist’s guide through the jungle of tropical biodiversity. Phytomed. 2019, 27, 153098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biluca, F.C.; de Gois, J.S.; Schulz, M.; Braghini, F.; Gonzaga, L.V.; Maltez, H.F.; Rodrigues, E.; Vitali, L.; Micke, G.A.; Borges, D.L.G.; et al. Phenolic compounds, antioxidant capacity and bioaccessibility of minerals of stingless bee honey (Meliponinae). J. Food Comp. Anal. 2017, 63, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temaru, E.; Shimura, S.; Amano, K.; Karasawa, T. Antibacterial activity of honey from stingless honeybees (Hymenoptera; Apidae; Meliponinae). Pol. J. Microbiol. 2007, 56, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beretta, G.; Orioli, M.; Maffei Facino, R. Antioxidant and radical scavenging activity of honey in endothelial cell cultures (EA.hy926). Planta Med. 2007, 73, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Liu, R.; Lu, Q.; Hao, P.; Xu, A.; Zhang, J.; Tan, J. Biochemical properties, antibacterial and cellular antioxidant activities of buckwheat honey in comparison to manuka honey. Food Chem. 2018, 252, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazirah, H.; Yasmin Anum, M.Y.; Norwahidah, A.K. Antioxidant properties of stingless bee honey and its effect on the viability of lymphoblastoid cell line. Med. Health 2019, 14, 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, T.; Zhuo, Q.; Zhang, S.Q. Evaluation of cellular antioxidant components of honeys using UPLC-MS/MS and HPLC-FLD based on the quantitative composition-activity relationship. Food Chem. 2019, 293, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampieri, F.; Quiles, J.L.; Orantes-Bermejo, F.J.; Gasparrini, M.; Forbes-Hernandez, T.Y.; Sánchez-González, C.; Llopis, J.; Rivas-García, L.; Afrin, S.; Varela-López, A.; et al. Are by-products from beeswax recycling process a new promising source of bioactive compounds with biomedical properties? Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 112, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz-Żukowska, R.; Naliwajko, S.K.; Bartosiuk, E.; Moskwa, J.; Isidorov, V.; Soroczyńska, J.; Borawska, M.H. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of beebread, and its influence on the glioblastoma cell line (U87MG). J. Apic. Sci. 2013, 57, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, Y.; Tsuruma, K.; Shimazawa, M.; Mishima, S.; Hara, H. Comparison of bee products based on assays of antioxidant capacities. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2009, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapetsas, A.; Voulgaridou, G.P.; Konialis, M.; Tsochantaridis, I.; Kynigopoulos, S.; Lambropoulou, M.; Stavropoulou, M.I.; Stathopoulou, K.; Aligiannis, N.; Bozidis, P.; et al. Propolis extracts inhibit UV-induced photodamage in human experimental in vitro skin models. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khacha-ananda, S.; Tragoolpua, K.; Chantawannakul, P.; Tragoolpua, Y. Antioxidant and anti-cancer cell proliferation activity of propolis extracts from two extraction methods. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 6991–6995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misir, S.; Aliyazicioglu, Y.; Demir, S.; Turan, I.; Yaman, S.O.; Deger, O. Antioxidant properties and protective effect of Turkish propolis on t-BHP-induced oxidative stress in foreskin fibroblast cells. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. 2018, 52, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.H.O.; Barreto, G.A.; Cerqueira, J.C.; Anjos, J.P.D.; Andrade, L.N.; Padilha, F.F.; Druzian, J.I.; Machado, B.A.S. Evaluation of the antioxidant profile and cytotoxic activity of red propolis extracts from different regions of northeastern Brazil obtained by conventional and ultrasound-assisted extraction. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzani, S.; Embaslat, W.; Imtara, H.; Kmail, A.; Kadan, S.; Zaid, H.; ElArabi, I.; Badiaa, L.; Saad, B. In vitro evaluation of the potential use of propolis as a multitarget therapeutic product: Physicochemical properties, chemical composition, and immunomodulatory, antibacterial, and anticancer properties. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 4836378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J.; Kim, B.Y.; Park, H.G.; Deng, Y.; Yoon, H.J.; Choi, Y.S.; Lee, K.S.; Jin, B.R. Major royal jelly protein 2 acts as an antimicrobial agent and antioxidant in royal jelly. J. Asia. Pac. Entomol. 2019, 22, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J.; Kim, B.Y.; Deng, Y.; Park, H.G.; Choi, Y.S.; Lee, K.S.; Jin, B.R. Antioxidant capacity of major royal jelly proteins of honeybee (Apis mellifera) royal jelly. J. Asia. Pac. Entomol. 2020, 23, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.Y.; Saravanakumar, K.; Wang, M.H. In vitro and in vivo antioxidant properties of water and methanol extracts of linden bee pollen. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 13, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živković, L.; Bajić, V.; Dekanski, D.; Čabarkapa-Pirković, A.; Giampieri, F.; Gasparrini, M.; Mazzoni, L.; Potparević, B.S. Manuka honey attenuates oxidative damage induced by H2O2 in human whole blood in vitro. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 119, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.F.; dos Santos, U.P.; Macorini, L.F.; de Melo, A.M.; Balestieri, J.B.; Paredes-Gamero, E.J.; Cardoso, C.A.; de Picoli Souza, K.; dos Santos, E.L. Antimicrobial, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of propolis from Melipona orbignyi (Hymenoptera, Apidae). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 65, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamfu, A.N.; Sawalda, M.; Fotsing, M.T.; Kouipou, R.M.T.; Talla, E.; Chi, G.F.; Epanda, J.J.E.; Mbafor, J.T.; Baig, T.A.; Jabeen, A.; et al. A new isoflavonol and other constituents from Cameroonian propolis and evaluation of their anti-inflammatory, antifungal and antioxidant potential. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 6, 1659–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, M.; Mrówczynska, L.; Waskiewicz, A.; Rogozinski, T.; Ratajczak, I. The role of seasonality on the chemical composition, antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity of Polish propolis in human erythrocytes. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2019, 29, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornara, L.; Biagi, M.; Xiao, J.; Burlando, B. Therapeutic properties of bioactive compounds from different honeybee products. Front. Pharmaco. 2017, 8, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Can, Z.; Yildiz, O.; Sahin, H.; Akyuz Turumtay, E.; Silici, S.; Kolayli, S. An investigation of Turkish honeys: Their physico-chemical properties, antioxidant capacities and phenolic profiles. Food Chem. 2015, 180, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, A.M.; Valverde, S.; Bernal, J.L.; Nozal, M.J.; Bernal, J. Extraction and determination of bioactive compounds from bee pollen. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 147, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, P.M.; Gauche, C.; Gonzaga, L.V.; Costa, A.C.; Fett, R. Honey: Chemical composition, stability and authenticity. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perna, A.; Simonetti, A.; Intaglietta, I.; Sofo, A.; Gambacorta, E. Metal content of southern Italy honey of different botanical origins and its correlation with polyphenol content and antioxidant activity. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 1909–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.Q.; Wang, K.; Marcucci, M.C.; Sawaya, A.C.H.F.; Hu, L.; Xue, X.F.; Wu, L.M.; Hu, F.L. Nutrient-rich bee pollen: A treasure trove of active natural metabolites. J. Func. Food 2018, 49, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, C.Y.; Chua, L.S.; Soontorngun, N.; Lee, C.T. Discovering potential bioactive compounds from Tualang honey. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2018, 52, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi Sadeer, N.; Montesano, D.; Albrizio, S.; Zengin, G.; Mahomoodally, M.F. The versatility of antioxidant assays in food science and safety-chemistry, applications, strengths, and limitations. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combarros-Fuertes, P.; Estevinho, L.M.; Dias, L.G.; Castro, J.M.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Tornadijo, M.E.; Fresno-Baro, J.M. Bioactive components and antioxidant and antibacterial activities of different varieties of honey: A screening prior to clinical application. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 688–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.C.; Yang, M.H.; Wen, H.M.; Chern, J.C. Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complementary colorimetric methods. J. Food Drug Anal. 2002, 10, 178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Arvouet-Grand, A.; Vennat, B.; Pourrat, A.; Legret, P. Standardisation d’un extrait de propolis et identification des principaux constituants [Standardization of propolis extract and identification of principal constituents]. J. Pharm. Belg. 1994, 49, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bankova, V.; Bertelli, D.; Borba, R.; Conti, B.J.; da Silva Cunha, I.B.; Danert, C.; Eberlin, M.N.; Falcão, S.I.; Isla, M.I.; Moreno, M.I.N.; et al. Standard methods for Apis mellifera propolis research. J. Apic. Res. 2019, 58, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dżugan, M.; Tomczyk, M.; Sowa, P.; Grabek-Lejko, D. Antioxidant activity as biomarker of honey variety. Molecules 2018, 23, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, M.; Fazlara, A.; Tulabifard, N. Effect of thermal treatment on physicochemical and antioxidant properties of honey. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mot, A.C.; Silaghi-Dumitrescu, R.; Sârbu, C. Rapid and effective evaluation of the antioxidant capacity of propolis extracts using DPPH bleaching kinetic profiles, FT-IR and UV–vis spectroscopic data. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2011, 24, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gülçin, I.; Bursal, E.; Sehitoğlu, M.H.; Bilsel, M.; Gören, A.C. Polyphenol contents and antioxidant activity of lyophilized aqueous extract of propolis from Erzurum, Turkey. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 2227–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apak, R.; Kubilay, G.; Mustafa, O.; Karademir, E. Novel total antioxidant capacity index for dietary polyphenols and vitamins C and E, using their cupric ion reducing capability in the presence of neocuproine: CUPRAC Method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7970–7981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouhoubi-Tafinine, Z.; Ouchemoukh, S.; Tamendjari, A. Antioxydant activity of some Algerian honey and propolis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 88, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyaizu, M. Studies on products of browning reactions: Antioxidant activities of products of browning reaction prepared from glucosamine. J. Nutrit. 1986, 44, 307–315. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, P.; Pineda, M.; Aguilar, M. Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of a phosphomolybdenum complex: Specific application to the determination of vitamin E. Anal. Biochem. 1999, 269, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, P.; Cheng, N.; Gao, H.; Wang, B.; Wei, Y.; Cao, W. Protective effects of buckwheat honey on DNA damage induced by hydroxyl radicals. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 2766–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinis, T.C.; Maderia, V.M.; Almeida, L.M. Action of phenolic derivatives (acetaminophen, salicylate, and 5-aminosalicylate) as inhibitors of membrane lipid peroxidation and as peroxyl radical scavengers. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994, 315, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, S.; Hornung, P.S.; Teixeira, G.L.; Malunga, L.N.; Apea-Bah, F.B.; Beux, M.R.; Beta, T.; Ribani, R.H. Bioactive compounds and biological properties of Brazilian stingless bee honey have a strong relationship with the pollen floral origin. Food Res. Int. 2019, 123, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, B.; Hampsch-Woodill, M.; Prior, R.L. Development and validation of an improved oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay using fluorescein as the fluorescent probe. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 4619–4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice- Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N.; Bristi, N.J.; Rafiquzzaman, M. Review on in vivo and in vitro methods evaluation of antioxidant activity. Saudi Pharm. J. 2013, 21, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robak, J.; Gryglewski, R.J. Flavonoids are scavengers of superoxide anions. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1988, 37, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunchandy, E.; Rao, M.N.A. Oxygen radical scavenging activity of curcumin. Int. J. Pharm. 1990, 58, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruch, R.J.; Cheng, S.J.; Klaunig, J.E. Prevention of cytotoxicity and inhibition of intercellular communication by antioxidant catechins isolated from Chinese green tea. Carcinogen 1989, 10, 1003–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gülçin, I. Antioxidants and antioxidant methods: An updated overview. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 651–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velioglu, Y.S.; Mazza, G.; Gao, L.; Oomah, B.D. Antioxidant activity and total phenolics in selected fruits, vegetables, and grain products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 4113–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, R.L.; Wu, X.L.; Schaich, K. Standardized methods for the determination of antioxidant capacity and phenolics in foods and dietary supplements. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 4290–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council Directive 2001/110/EC of 20 December 2001 Relating to Honey. OJ L 10, 12.1. 2002, pp. 47–52. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02001L0110–20140623&from=EN (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Crane, E. The World History of Beekeeping and Honey Hunting; Duckworth: London, UK, 1999; 682p. [Google Scholar]

- Mračević, S.Đ.; Krstić, M.; Lolić, A.; Ražić, S. Comparative study of the chemical composition and biological potential of honey from different regions of Serbia. Microchem. J. 2020, 152, 104420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Ramos, A.; Gonçalves, M.M.; Bernardo, M.; Mendes, B. Antioxidant activity, quality parameters and mineral content of Portuguese monofloral honeys. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2013, 30, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanzio, A.; Tesoriere, L.; Allegra, M.; Livrea, M.A. Monofloral honeys by Sicilian black honeybee (Apis mellifera ssp. sicula) have high reducing power and antioxidant capacity. Heliyon 2016, 2, e00193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauliuc, D.; Dranca, F.; Oroian, M. Antioxidant activity, total phenolic content, individual phenolics and physicochemical parameters suitability for Romanian honey authentication. Foods 2020, 9, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, P.V.; Krishnan, K.T.; Salleh, N.; Gan, S.H. Biological and therapeutic effects of honey produced by honey bees and stingless bees: A comparative review. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2016, 26, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halagarda, M.; Groth, S.; Popek, S.; Rohn, S.; Pedan, V. Antioxidant activity and phenolic profile of selected organic and conventional honeys from Poland. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Farsi, M.; Al-Amri, A.; Al-Hadhrami, A.; Al-Belushi, S. Color, flavonoids, phenolics and antioxidants of Omani honey. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alotibi, I.A.; Harakeh, S.M.; Al-Mamary, M.; Mariod, A.A.; Al-Jaouni, S.K.; Al-Masaud, S.; Alharbi, M.G.; Al-Hindi, R.R. Floral markers and biological activity of Saudi honey. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 1369–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Tulipani, S.; Díaz, D.; Estevez, Y.; Romandini, S.; Giampieri, F.; Damiani, E.; Astolfi, P.; Bompadre, S.; Battino, M. Antioxidant and antimicrobial capacity of several monofloral Cuban honeys and their correlation with color, polyphenol content and other chemical compounds. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 2490–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Giampieri, F.; Brenciani, A.; Mazzoni, L.; Gasparrini, M.; González-Paramás, A.M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Morroni, G.; Forbes-Hernández, T.Y.; Simoni, S.; et al. Apis mellifera vs melipona beecheii Cuban polifloral honeys: A comparison based on their physicochemical parameters, chemical composition and biological properties. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 87, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biluca, F.C.; da Silva, B.; Caon, T.; Mohr, E.T.B.; Vieira, G.N.; Gonzaga, L.V.; Vitali, L.; Micke, G.; Fett, R.; Dalmarco, E.M.; et al. Investigation of phenolic compounds, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities in stingless bee honey (Meliponinae). Food Res. Int. 2020, 129, 108756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biluca, F.C.; Braghini, F.; Gonzaga, L.V.; Costa, A.C.O.; Fett, R. Physicochemical profiles, minerals and bioactive compounds of stingless bee honey (Meliponinae). J. Food Comp. Anal. 2016, 50, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodó, A.; Radványi, L.; Kőszegi, T.; Csepregi, R.; Nagy, D.U.; Farkas, Á.; Kocsis, M. Melissopalynology, antioxidant activity and multielement analysis of two types of early spring honeys from Hungary. Food Bios. 2020, 35, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra Bonvehi, J.; Ventura Coll, F.; Orantes Bermejo, J.F. Characterization of avocado honey (Persea americana Mill.) produced in Southern Spain. Food Chem. 2019, 287, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, S.; Chen, S.; Song, Y. Antioxidative, antibrowning and antibacterial activities of sixteen floral honeys. Food Funct. 2011, 2, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, I.A.; da Silva, T.M.; Camara, C.A.; Queiroz, N.; Magnani, M.; de Novais, J.S.; Soledade, L.E.; Lima, E.O.; de Souza, A.L.; de Souza, A.G. Phenolic profile, antioxidant activity and palynological analysis of stingless bee honey from Amazonas, Northern Brazil. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 3552–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolanos de la Torre, A.A.; Henderson, T.; Nigam, P.S.; Owusu-Apenten, R.K. A universally calibrated microplate ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay for foods and applications to Manuka honey. Food Chem. 2015, 174, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.W.F.; Vasconcelos, M.R.; Melissa Oda-Souza, M.; de Oliveira, F.F.; Lòpez, A.M.Q. Honey and bee pollen produced by Meliponini (Apidae) in Alagoas, Brazil: Multivariate analysis of physicochemical and antioxidant profiles. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 38, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dżugan, M.; Grabek-Lejko, D.; Swacha, S.; Tomczyk, M.; Bednarska, S.; Kapusta, I. Physicochemical quality parameters, antibacterial properties and cellular antioxidant activity of Polish buckwheat honey. Food Biosci. 2020, 34, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Haskoury, R.; Kriaa, W.; Lyoussi, B.; Makni, M. Ceratonia siliqua honeys from Morocco: Physicochemical properties, mineral contents, and antioxidant activities. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018, 26, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escuredo, O.; Míguez, M.; Fernández-González, M.; Carmen Seijo, M. Nutritional value and antioxidant activity of honeys produced in a European Atlantic area. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantal Rodríguez Flores, M.; Escuredo, O.; Carmen Seijo, M. Assessment of physicochemical and antioxidant characteristics of Quercus pyrenaica honeydew honeys. Food Chem. 2015, 166, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjanović, S.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Novaković, M.M.; Pastor, F.T.; Pezo, L.; Battino, M.; Sužnjevic, D.Ž. Comparative analysis of antioxidant activity of honey of different floral sources using recently developed polarographic and various spectrophotometric assays. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2013, 30, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gül, A.; Pehlivan, T. Antioxidant activities of some monofloral honey types produced across Turkey. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 1056–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabagias, I.K.; Karabournioti, S.; Karabagias, V.K.; Badeka, A.V. Palynological, physico-chemical and bioactivity parameters determination, of a less common Greek honeydew honey: “dryomelo”. Food Cont. 2020, 109, 106940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kek, S.P.; Chin, N.L.; Yusofa, Y.A.; Tan, S.W.; Chua, L.S. Total phenolic contents and colour intensity of Malaysian honeys from the Apis spp. and Trigona spp. bees. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2014, 2, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, R.K.; Halim, A.S.; Syazana, M.S.; Sirajudeen, K.N. Tualang honey has higher phenolic content and greater radical scavenging activity compared with other honey sources. Nutr. Res. 2011, 31, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuś, P.M.; Congiu, F.; Teper, D.; Sroka, Z.; Jerković, I.; Tuberoso, C.I.G. Antioxidant activity, color characteristics, total phenol content and general HPLC fingerprints of six Polish unifloral honey types. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 55, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, J.; Orsák, M.; Hejtmánková, A.; Kovářova, E. Evaluation of antioxidant activity and total phenolics of selected Czech honeys. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 43, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianda, R.L.P.; D’Oliveira Sant’Ana, L.; EchevarriaI, A.; Castro, R.N. Antioxidant activity and phenolic composition of brazilian honeys and their extracts. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2012, 4, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.R.; Ye, Y.L.; Lin, T.Y.; Wang, Y.W.; Peng, C.C. Effect of floral sources on the antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory activities of honeys in Taiwan. Food Chem. 2013, 139, 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.M.; Schneider, K.R.; Cisneros, K.V.; Gu, L. Determination of antioxidant capacities, α-dicarbonyls, and phenolic phytochemicals in Florida varietal honeys using HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn. J Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 8623–8631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, K.S.; Gasparotto Sattler, J.A.; Lauer Macedo, L.F.; Serna González, C.V.; Pereira de Melo, I.L.; da Silva Araújo, E.; Granato, D.; Sattler, A.; Bicudo de Almeida-Muradian, L. Phenolic compounds, antioxidant capacity and physicochemical properties of Brazilian Apis mellifera honeys. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 91, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayik, G.A.; Nanda, V. A chemometric approach to evaluate the phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity and mineral content of different unifloral honey types from Kashmir, India. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 74, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayik, G.A.; Suhag, Y.; Majid, I.; Nanda, V. Discrimination of high altitude Indian honey by chemometric approach according to their antioxidant properties and macro minerals. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2018, 17, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, M.M.; Olmez, C. Some qualitative properties of different monofloral honeys. Food Chem. 2014, 163, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, B.A.; Mendoza, S.; Iturriga, M.H.; Castaño-Tostado, E. Quality parameters and antioxidant and antibacterial properties of some Mexican honeys. J Food Sci. 2012, 77, C121–C127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Flores, M.S.; Escuredo, O.; Míguez, M.; Seijo, M.C. Differentiation of oak honeydew and chestnut honeys from the same geographical origin using chemometric methods. Food Chem. 2019, 297, 124979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, S.; Minaei, S.; Moghaddam-Charkari, N.; Barzegar, M. Honey characterization using computer vision system and artificial neural networks. Food Chem. 2014, 159, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silici, S.; Sagdic, O.; Ekici, L. Total phenolic content, antiradical, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Rhododendron honeys. Food Chem. 2010, 121, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.M.S.; dos Santos, F.P.; Evangelista-Rodrigues, A.; da Silva, E.M.S.; da Silva, G.S.; de Novais, J.S.; dos Santos, F.A.R.; Camara, C.A. Phenolic compounds, melissopalynological, physicochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of jandaíra (Melipona subnitida) honey. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2013, 29, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.P.; Caldas, M.J.M.; Machado, C.S.; do Nascimento, A.S.; Lordêlo, M.S.; Bárbara, M.F.S.; Evangelista-Barreto, N.S.; Estevinho, L.M.; de Carvalho, C.A.L. Antioxidants activity and physicochemical properties of honey from social bees of the Brazilian semiarid region. J. Apic. Res. 2020, 1823671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.M.; de Souza, E.L.; Marques, G.; Meireles, B.; de Magalhães Cordeiro, Â.T.; Gullón, B.; Pintado, M.M.; Magnani, M. Polyphenolic profile and antioxidant and antibacterial activities of monofloral honeys produced by Meliponini in the Brazilian semiarid region. Food Res. Int. 2016, 84, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornuk, F.; Karaman, S.; Ozturk, I.; Toker, O.S.; Tastemur, B.; Sagdic, O.; Dogan, M.; Kayacier, A. Quality characterization of artisanal and retail Turkish blossom honeys: Determination of physicochemical, microbiological, bioactive properties and aroma profile. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 46, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasić, V.; Gašić, U.; Stanković, D.; Lušić, D.; Vukić-Lušić, D.; Milojković-Opsenica, D.; Tešić, Ž.; Trifković, J. Towards better quality criteria of European honeydew honey: Phenolic profile and antioxidant capacity. Food Chem. 2019, 274, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilczyńska, A. Effect of filtration on colour, antioxidant activity and total phenolics of honey. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 57, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoal, A.; Rodrigues, S.; Teixeira, A.; Feás, X.; Estevinho, L.M. Biological activities of commercial bee pollens: Antimicrobial, antimutagenic, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 63, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De-Melo, A.A.M.; Estevinho, M.L.M.F.; Gasparotto Sattler, J.A.; Souza, B.R.; da Silva Freitas, A.; Barth, O.M.; Almeida-Muradian, L.B. Effect of processing conditions on characteristics of dehydrated bee-pollen and correlation between quality parameters. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 65, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisow, B.; Denisow-Pietrzyk, M. Biological and therapeutic properties of bee pollen: A review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4303–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga, C.M.; Serrato, J.C.; Quicazan, M.C. Chemical, nutritional and bioactive characterization of Colombian bee-bread. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2015, 43, 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Estevinho, L.M.; Dias, T.; Anjos, O. Influence of the storage conditions (frozen vs. dried) in health-related lipid indexes and antioxidants of bee pollen. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol 2018, 1800393. [Google Scholar]

- De-Melo, A.A.M.; Estevinho, L.M.; Moreira, M.M.; Delerue-Matos, C.; da Silva de Freitas, A.; Barth, O.M.; de Almeida-Muradian, L.B. A multivariate approach based on physicochemical parameters and biological potential for the botanical and geographical discrimination of Brazilian bee pollen. Food Biosci. 2018, 25, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakour, M.; Fernandes, A.; Barros, L.; Sokovic, M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Iyoussi, B. Bee bread as a functional product: Chemical composition and bioactive properties. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 109, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaškonienė, V.; Adaškevičiūtė, V.; Kaškonas, P.; Mickienė, R.; Maruška, A. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of natural and fermented bee pollen. Food Biosci. 2020, 34, 100532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, S. Pollen: Production, nutrition and health: A review. Bee Prod. Sci. 2017, 36. Available online: http://www.bee-hexagon.net/ (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Atsalakis, E.; Chinou, I.; Makropoulou, M.; Karabournioti, S.; Graikou, K. Evaluation of phenolic compounds in Cistus creticus bee pollen from Greece. Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Nat. Prod. Comm. 2017, 12, 1813–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Florio Almeida, J.; dos Reis, A.S.; Heldt, L.F.S.; Pereira, D.; Bianchin, M.; de Moura, C.; Plata-Oviedo, M.V.; Haminiuk, C.W.I.; Ribeiro, I.S.; da Luz, C.F.P.; et al. Lyophilized bee pollen extract: A natural antioxidant source to prevent lipid oxidation in refrigerated sausages. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 76, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadzilah, N.H.J.; Mohd, F.; Jajuli, R.; Omar, W.A.W. Total phenolic content, total flavonoid and antioxidant activity of ethanolic bee pollen extracts from three species of Malaysian stingless bee. J. Apic. Res. 2017, 56, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graikou, K.; Kapeta, S.; Aligiannis, N.; Sotiroudis, G.; Chondrogianni, N.; Gonos, E.; Chinou, I. Chemical analysis of Greek pollen—Antioxidant, antimicrobial and proteasome activation properties. Chem. Central J. 2011, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaycioglu, Z.; Kaygusuz, H.; Doker, S.; Kolayli, S.; Erim, F.B. Characterization of Turkish honeybee pollens by principal component analysis based on their individual organic acids, sugars, minerals, and antioxidant activities. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 84, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Yang, X.; Lu, Q.; Liu, R. Antioxidant and anti-tyrosinase activities of bee pollen and identification of active components. J. Apic. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, M.; Moreira, L.; Feás, X.; Estevinho, L.M. Honeybee-collected pollen from five Portuguese Natural Parks: Palynological origin, phenolic content, antioxidant properties and antimicrobial activity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulusoy, E.; Kolayli, S. Phenolic composition and antioxidant properties of Anzer bee pollen. J. Food Biochem. 2014, 38, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanišová, E.; Kačániová, M.; Frančáková, H.; Petrová, J.; Hutková, J.; Brovarskyi, V.; Velychko, S.; Adamchuk, L.; Schubertová, Z.; Musilová, J. Bee bread—Perspective source of bioactive compounds for future. Potravinarstvo Slovak J. Food Sci. 2015, 9, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węglińska, M.; Szostak, R.; Kita, A.; Nemś, A.; Mazurek, S. Determination of nutritional parameters of bee pollen by Raman and infrared spectroscopy. Talanta 2020, 212, 120790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borycka, K.; Grabek-Lejko, D.; Kasprzyk, I. Antioxidant and antibacterial properties of commercial bee pollen products. J. Apic. Res. 2015, 54, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Waili, N.; Al-Ghamdi, A.; Ansari, M.J.; Al-Attal, Y.; Salom, K. Synergistic effects of honey and propolis toward drug multi-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and Candida albicans isolates in single and polymicrobial cultures. Int. J. Med. Sci 2012, 9, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sforcin, J.M. Biological properties and therapeutic applications of propolis. Phytother. Res. 2016, 6, 894–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graikou, K.; Popova, M.; Gortzi, O.; Bankova, V.; Chinou, I. Characterization and biological evaluation of selected Mediterranean propolis samples. Is it a new type? LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 65, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, N.A.; Ja’afar, F.; Yasin, H.M.; Taha, H.; Petalcorin, M.I.R.; Mamit, M.H.; Kusrini, E.; Usman, A. Physicochemical analyses, antioxidant, antibacterial, and toxicity of propolis particles produced by stingless bee Heterotrigona itama found in Brunei Darussalam. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, M.L.F.; Ribeiro, P.R.; Franco, R.L.P.; Hilhorst, H.W.M.; de Castro, R.D.; Fernandez, L.G. Metabolite profiling, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Brazilian propolis: Use of correlation and multivariate analyses to identify potential bioactive compounds. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C.; Mura, F.; Valenzuela, G.; Figueroa, C.; Salinas, R.; Zuñiga, M.C.; Torres, J.L.; Fuguet, E.; Delporte, C. Identification of phenolic compounds by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS and antioxidant activity from Chilean propolis. Food Res. Int. 2014, 64, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalaro, R.I.; Cruz, R.G.D.; Dupont, S.; de Moura Bell, J.M.L.N.; Vieira, T.M.F.S. In vitro and in vivo antioxidant properties of bioactive compounds from green propolis obtained by ultrasound-assisted extraction. Food Chem. X 2019, 4, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calegari, M.A.; Ayres, B.B.; dos Santos Tonial, L.M.; de Alencar, S.M.; Oldoni, T.L.C. Fourier transform near infrared spectroscopy as a tool for predicting antioxidant activity of propolis. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2020, 32, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.C.F.D.; Salatino, A.; Motta, L.B.D.; Negri, G.; Salatino, M.L.F. Chemical characterization, antioxidant and anti-HIV activities of a Brazilian propolis from Ceará state. Braz. J. Pharmacogn. 2019, 29, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escriche, I.; Juan-Borrás, M. Standardizing the analysis of phenolic profile in propolis. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, B.L.; Gonzaga, L.V.; Vitali, L.; Micke, G.A.; Maltez, H.F.; Ressureição, C.; Costa, A.C.O.; Fett, R. Southern-Brazilian geopropolis: A potential source of polyphenolic compounds and assessment of mineral composition. Food Res. Int. 2019, 126, 108683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.S.; Cunha, A.; Cardoso, S.M.; Oliveira, R.; Almeida-Aguiar, C. Constancy of the bioactivities of propolis samples collected on the same apiary over four years. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskar, R.A.; Sk, I.; Roy, N.; Begum, N.A. Antioxidant activity of Indian propolis and its chemical constituents. Food Chem. 2010, 122, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, M.G.; Nunes, S.; Dandlen, S.A.; Cavaco, A.M.; Antunes, M.D. Phenols and antioxidant activity of hydro-alcoholic extracts of propolis from Algarve, South of Portugal. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 3418–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdal, T.; Ceylan, F.D.; Eroglu, N.; Kaplan, M.; Olgun, E.O.; Capanoglu, E. Investigation of antioxidant capacity, bioaccessibility and LC-MS/MS phenolic profile of Turkish propolis. Food Res. Int. 2019, 122, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potkonjak, N.I.; Veselinović, D.S.; Novaković, M.M.; Gorjanović, S.Ž.; Pezo, L.L.; Sužnjević, D.Ž. Antioxidant activity of propolis extracts from Serbia: A polarographic approach. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 3614–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristivojevic, P.; Dimkic, I.; Guzelmeric, E.; Trifkovic, J.; Knezevic, M.; Beric, T.; Yesilada, E.; Milojković-Opsenica, D.; Stankovic, S. Profiling of Turkish propolis subtypes: Comparative evaluation of their phytochemical compositions, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 95, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhana, N.; Lohidasan, S.; Mahadik, K.R. Marker-based standardization and investigation of nutraceutical potential of Indian propolis. J. Integr. Med. 2017, 15, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.C.; Rodrigues, S.; Feás, X.; Estevinho, L.M. Antimicrobial activity, phenolic profile and role in the inflammation of propolis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 1790–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, G.M.; Al Sammarrae, K.W.; Ad’hiah, A.H.; Zucchetti, M.; Frapolli, R.; Bello, E.; Erba, E.; D’Incalci, M.; Bagnati, R. Chemical characterization of Iraqi propolis samples and assessing their antioxidant potentials. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 2415–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusop, S.A.T.W.; Sukairi, A.H.; Sabri, W.M.A.W.; Asaruddin, M.R. Antioxidant, antimicrobial and cytotoxicity activities of propolis from Beladin, Sarawak stingless bees Trigona itama extract. Mater. Today Proceed. 2019, 19, 1752–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svečnjak, L.; Chesson, L.A.; Gallina, A.; Maia, M.; Martinello, M.; Mutinelli, F.; Muz, M.N.; Nunes, F.M.; Saucy, F.; Tipple, B.J.; et al. Standard methods for Apis mellifera beeswax research. J. Apic. Res. 2019, 58, 1–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münstedt, K.; Bogdanov, S. Bee products and their potential use in modern medicine. J. ApiProd. ApiMed. Sci. 2009, 1, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhu, M.; Wang, K.; Yang, E.; Su, J.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, N.; Xue, X.; Wu, L.; Cao, W. Identification and quantitation of bioactive components from honeycomb (Nidus Vespae). Food Chem. 2020, 314, 126052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampieri, F.; Gasparrini, M.; Forbes-Hernández, T.Y.; Manna, P.P.; Zhang, J.; Reboredo-Rodríguez, P.; Cianciosi, D.; Quiles, J.L.; Torres Fernández-Piñar, C.; Orantes-Bermejo, F.J.; et al. Beeswax by-products efficiently counteract the oxidative damage induced by an oxidant agent in human dermal fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavel, C.I.; Mărghitaş, L.A.; Dezmirean, D.S.; Tomoş, L.I.; Bonta, V.; Şapcaliu, A.; Buttstedt, A. Comparison between local and commercial royal jelly—Use of antioxidant activity and 10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid as quality parameter. J. Apic. Res. 2014, 53, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangieh, J.; Salma, Y.; Haddad, K.; Mattei, C.; Legros, C.; Fajloun, Z.; El Obeid, D. First characterization of the venom from Apis mellifera syriaca, a honeybee from the Middle East region. Toxins 2019, 11, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobral, F.; Sampaio, A.; Falcão, S.; Queiroz, M.J.; Calhelha, R.C.; Vilas-Boas, M.; Ferreira, I.C. Chemical characterization, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic properties of bee venom collected in Northeast Portugal. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 94, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somwongin, S.; Chantawannakul, P.; Chaiyana, W. Antioxidant activity and irritation property of venoms from Apis species. Toxicon 2018, 145, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Bíliková, K.; Casabianca, H.; Daniele, G.; Espindola, F.S.; Feng, M.; Guan, C.; Han, B.; Kraková, T.K.; Li, J.; et al. Standard methods for Apis mellifera royal jelly research. J. Apic. Res. 2019, 58, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, A.N.K.G.; Nair, A.J.; Sugunan, V.S. A review on royal jelly proteins and peptides. J. Func. Foods 2018, 44, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, M.; Al-Ghamdi, A. Bioactive compounds and health-promoting properties of royal jelly: A review. J. Func. Foods 2012, 4, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunugi, H.; Mohammed Ali, A. Royal jelly and its components promote healthy aging and longevity: From animal models to humans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, T.; Inoue, R. Preparation and functional properties of water extract and alkaline extract of royal jelly. Food Chem. 2004, 84, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.R.; Yang, Y.C.; Shi, L.S.; Peng, C.C. Antioxidant properties of royal jelly associated with larval age and time of harvest. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 11447–11452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sığ, A.K.; Öz-Sığ, Ö.; Güney, M. Royal jelly: A natural therapeutic? Ortadogu Tıp Derg 2019, 11, 333–341. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov, S. Bee venom: Composition, health, medicine: A Review. Bee Prod. Sci. 2017, 24. Available online: http://www.bee-hexagon.net/ (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- El-Seedi, H.R.; Khalifa, S.A.M.; El-Wahed, A.A.; Gao, R.; Guo, Z.; Tahir, H.E.; Zhao, C.; Du, M.; Farag, M.A.; Musharraf, S.G.; et al. Honeybee products: An updated review of neurological actions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 101, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, K.; Abushouk, A.I.; AbdelKarim, A.H.; Mohammed, M.; Negida, A.; Shalash, A.S. Bee venom for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease: How far is it possible? Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 91, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premratanachai, P.; Chanchao, C. Review of the anticancer activities of bee products. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2014, 4, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Ye, Y.; Wang, X.R.; Lin, L.T.; Xiao, L.Y.; Zhou, P.; Shi, G.X.; Liu, C.Z. Bee venom therapy: Potential mechanisms and therapeutic applications. Toxicon 2018, 148, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanafi, M.Y.; Zaher, E.L.M.; El-Adely, S.E.M.; Sakr, A.; Ghobashi, A.H.M.; Hemly, M.H.; Kazem, A.H.; Kamel, M.A. The therapeutic effects of bee venom on some metabolic and antioxidant parameters associated with HFD-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver in rats. Exp. Ther Med. 2018, 15, 5091–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, H.; Song, I.B.; Han, H.J.; Lee, N.Y.; Cha, J.Y.; Son, Y.K.; Kwon, J. Antioxidant activity of royal jelly hydrolysates obtained by enzymatic treatment. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2018, 38, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohdaly, A.A.A.; Mahmoud, A.A.; Roby, M.H.H.; Smetanska, I.; Ramadan, M.F. Phenolic extract from propolis and bee pollen: Composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities. J. Food Biochem. 2015, 39, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Assay | Reaction Mechanisms | Methods in Brief | Main Characteristics | Set up Method Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total phenolic (phenols and polyphenols) content (TPC) | Electron transfer | Reduction of a yellow molybdate-tungstate reagent (Folin-Ciocalteu reagent) induced by the phenols in the sample, under alkaline conditions, a blue-colored chromophore (abs. 700, 740, 750, 760 or 765 nm). | Simple, rapid, and reproducible method. Sensitive to nonphenolic electron donating antioxidants as reducing sugars, amino acids, ascorbic acid, Cu (I) [42,43]. | [44] |

| Total flavonoids content (TFC) | Colored complex formation | Aluminum chloride forms acid stable yellow complexes with the C-4 keto groups and either the C-3 or the C-5 hydroxyl group of flavones and flavonols. In addition, it forms acid labile complexes with the orthodihydroxyl groups in some flavonoid rings (abs 420 or 510 nm). | Possible overestimation as some nonflavonoid compounds exhibit absorbance at the same wavelength. Specific only for flavones and flavonols [45]. | [46] |

| DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) free radical-scavenging assay | Electron transfer | The decolorization of DPPH occurs from purple to yellow when the unpaired electron of DPPH forms a pair with a hydrogen donated by a free radical scavenging antioxidant, thus converting DPPH into its reduced form (abs. 515 or 517 nm). | Easy, simple, rapid, reproducible, and reasonably costly method. Efficient for thermally unstable compounds and highly sensitive [42,47]. Unaffected by metal ion chelation and enzyme inhibition [48]; reflects only the activity of water-soluble antioxidants [49]. Sensitive to light, oxygen, and impurities. Rate-limited by a proton transfer step, affected by the solvent system and the ionization equilibrium of phenol and phenolate compounds in solution [50]. | [51] |

| Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay | Electron transfer | Reduction of a ferric 2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine complex (Fe3+-TPTZ) to its ferrous, violet-blue form (Fe2+-TPTZ) in the presence of antioxidants (abs. 593 or 700 nm). | Simple, reproducible, and sensitive. The high amount of reducing sugars in honey could contribute to higher reducing antioxidant power. Unable to detect slowly-reacting polyphenolic compounds and thiols [48]. | [52] |

| Cupric ion reducing antioxidant capacity (CUPRAC) Assay | Electron transfer | Bis(neocuproine)copper(II) chloride [Cu(II)-Nc], reacts with polyphenols where the reactive Ar-OH groups of polyphenols are oxidized to the corresponding quinones and Cu (II)-Nc is reduced to the highly colored Cu (I)-Nc (abs 450 nm). | Carried out at pH 7.0 and simultaneously measure hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants. Fast enough to oxidize glutathione and thiol-type antioxidants [53]. | [54] |

| Reducing power method (RP) | Electron transfer/ Hydrogen atom transfer reaction. | Substances, which have reduction potential, react with potassium ferricyanide (Fe3+) to form potassium ferrocyanide (Fe2+), which then reacts with ferric chloride to form ferric ferrous complex (abs. 700 nm). | Chelating effect of the ions Fe3+ of polyphenols related to the highly nucleophilic aromatic rings. The degree of hydroxylation and methylation of the phenolic compound and the presence of other non-phenolic compounds such as enzymes and non-enzyme materials possibly involved [55]. | [56] |

| Total antioxidant capacity (TAA)/ phosphomolybdenum method | Electron transfer | Based on the reduction of Mo(VI) to Mo(V) by the reducing compounds and the formation of a green phosphate/Mo(V) complex at acidic pH (abs. 695 nm). | Simple, sensitive, and cheap method to evaluate water-soluble and fat-soluble antioxidants. Bad correlation with bioactive compounds (phenolics, flavonoids) and weak correlation with free radical scavenging assays (DPPH). Non-specific, detecting also ascorbic acid, carotenoids, and α-tocopherol [42]. | [57] |

| Ferrous ion-chelating activity | Metal-chelating activity | Ferrozine can form a complex with a red color by forming chelates with Fe2+. This reaction is restricted in the presence of other chelating agents and results in a decrease of the red color of the ferrozine-Fe2+ complexes. EDTA or citric acid can be used as a positive control (abs. 562 nm). | Bivalent transition metal ions can lead to the formation of hydroxyl radicals and hydroperoxide decomposition reactions. Iron chelation can delay these processes [58]. Simple, reproducible, and cheap but non-specific reacting also with peptides and sulphates [42]. | [59] |

| Oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) method | Hydrogen atom transfer reaction | Measuring the decrease in fluorescence of a protein (fluorescein) that results from the loss of its conformation when it suffers oxidative damage caused by a source of peroxyl radicals (ROO•) generated by the thermolytic breakdown of 2,2′-azobis(amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH) (excit. 485 ± 20 nm emiss. 528 ± 20 nm). | Both hydrophilic and hydrophobic antioxidants detected by altering the radical source and solvent. Use reactants with a redox potential and mechanism of reaction similar to those of physiological oxidants at a physiological pH. The most biologically relevant assays [60]. | [61] |

| ABTS (2,2-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) radical cation decolorization assay/Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) method | Electron transfer | When an antioxidant is added to the ABTS•+ blue-green chromophore, it is reduced to ABTS and discolored (abs. 734 or 750 nm). | A “nonphysiological” radical source used over a wide pH range and in multiple media to determine both hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidant capacities [60]. | [62] |

| Superoxide radical (SOD) scavenging activity assay | Superoxide scavenging potential | Superoxide radicals are produced by NADH/PMS (phenazine methosulfate) systems via the oxidation of NADH, bringing about the reduction of nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) to purple formazan (abs. 560 nm). | Dangerous hydroxyl radicals and singlet oxygen are produced by superoxide anions, both contributing to oxidative stress [63]. They bear resemblance to biological systems in contrast to DPPH or ABTS, which are synthetic radicals. Non-specific and expensive [42]. | [64] |

| Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity assay | Hydroxyl radical scavenging potential | Based on the competitive ability of the sample with deoxyribose for hydroxyl radicals generated from Fe3+-EDTA-ascorbic acid and H2O2 reaction mixture, leading to a decreased yield of malondialdehyde-like products, which in turn reduce the formation of the TBA-chromophore (abs. 520 or 532 nm). | Hydroxyl radical, one of the potent reactive oxygen species, reacts with polyunsaturated fatty acid moieties of cell membrane phospholipids, damaging the cell [63]. | [65] |

| Hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity assay | Hydrogen peroxide scavenging potential | The absorbance of a solution of hydrogen peroxide in phosphate buffer (PBS) is acquired before and after the addition of the sample (abs. 230 nm). | Hydrogen peroxide may enter into the human body through inhalation and eye or skin contact. Rapidly decomposed into oxygen and water; may produce hydroxyl radicals that can cause DNA damage [63]. | [66] |

| β-Carotene-linoleic acid bleaching assay (BCB) | Hydrogen transfer reaction | Linoleic acid is oxidized by ROS produced by oxygenated water. The products will initiate the β-carotene oxidation, and, as the molecule loses its double bonds, the compound loses its characteristic orange color (abs. 434 nm). | Hydrogen transfer reactions are solvent and pH-independent and usually quite rapid (seconds to minutes). Reducing agents, including metals, complicate these assays leading to erroneously high reactivity [67]. | [68] |

| Sample Size | Botanical Origin | Bee Species 1 | Country | TPC 2 | TFC 3 | AOA 4 | Characterization | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 | 10 Sumer, 10 Sidr and 6 multiflora | A. mellifera | Oman | 842–2898 mg GAE/kg | 521–2890 mg CE/kg | 7.8–190.1 mg/mL EC50 DPPH | n.d. | [78] |

| 11 | 1 Talh, 1 Olive, 1 Sidr, 8 multiflora | n.s. | Saudi Arabia | 0.78–5.02 mg GAE/g | n.d. | 5.89–53.93% DPPH | GC-MS | [79] |

| 83 | 17 Linen vine, 16 Morning glory, 18 Christmas vine, 16 Black mangrove, 16 Singing bean | n.s. | Cuba | 213.9–595.8 mg GAE/kg | 10–25 mg CE/kg | 27.0–96.9 µmol TE/100g FRAP 103.5294.5 µmol TE/100g TEAC | n.d. | [80] |

| 16 | Multiflora, 8 from A. mellifera and 8 from M. beecheii | A. mellifera, M. beecheii | Cuba | 54.30 and 94.39 mg GAE/100g | 2.68 and 4.19 mg CE/100g | 159.70 and 175.82 µmol TE/100g FRAP 31.06 and 42.23 µmol TE/100g DPPH | HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS | [81] |

| 32 | Different monoflora and 2 honeydew | A. mellifera spp. sicula | Italy | 16.5–133.3 mg GAE/100g | 4.0–82.1 mg QE/100g | 17.8–165.7 mg AAE/100g FRAP 8.5–238.4 μmol TE/100g DPPH 19.2–270.3 4 μmol TE/100g ABTS | n.d. | [74] |

| 32 | Multiflora, 8 for each bee species | M. bicolor, M. quadrifasciata, M. marginata, S. bipuncata | Brazil | 220.4–708.1 mg GAE/kg | n.d. | 1.61–34.73 µmol TE/kg ABTS 9.71–39.10 µmol TE/kg DPPH 35.49–94.35 µmol TE/kg ORAC | HPLC–PDA | [60] |

| 14 | n.s. | n.s. | Lithuania | 168–278 mg GAE/100g | n.d. | 65–88% DPPH | n.d. | [6] |

| 8 | Multiflora from 6 different Meliponinae | Meliponinae, 6 spp. | Brazil | 10.4–57.4 mg GAE/100g | n.d. | 0.8–28.2 mg AAE/100g DPPH 67.5–734.5 µmol Fe2+/100g FRAP | LC-MS | [82] |

| 33 | Multiflora from 10 different Meliponinae | Meliponinae, 10 spp. | Brazil | 10.3–98.0 mg GAE/100g | n.d. | 1.41–18.5 mg AAE/100g DPPH 61.1–624 µmol Fe2+/100g FRAP | n.d. | [83] |

| 13 | Multiflora from 9 different Meliponinae | Meliponinae, 9 spp. | Brazil | n.d. | 199–667 μmol TE/100g ORAC | HPLC–ESI-MS/MS | [14] | |

| 14 | 8 Rape and 8 multiflora | n.s. | Hungary | 170–330 mg GAE/kg | n.d. | 63–110 μmol TE/100g TEAC 27–42 mg TE/mL EC50 DPPH 22–39 μmolTE/g ORAC | n.d. | [84] |

| 20 | Avocado | n.s. | Spain | 103.1–137.8 mg GAE/100g | n.d. | 2.4–2.8 μmol TE/g TEAC | n.d. | [85] |

| 62 | 11 monoflora, 2 honeydew and 7 multiflora | n.s. | Turkey | 16.02–120.04 mg GAE/100g | 0.65–8.10 mg QE/100g | 0.64–4.30 μmol Fe2+/g FRAP 12.56–152.40 mg TE/mL EC50 DPPH | HPLC-UV | [36] |

| 16 | 16 monoflora | n.s. | China | 60.5–100.8 mg GAE/100g | 0.6–2.3 mg RE/100g | 56.0–101.2 mg TE/100g DPPH 10.1–14.5 mg TE/100g ABTS 7.0–14.9 mg TE/100g FRAP | n.d. | [86] |

| 15 | 8 monoflora, 7 multiflora | n.s. | Spain | 23.1–158 mg GAE/100g | 1.65–5.93 mg CE/100g | 5.46–202 mg/mL EC50 DPPH 26.3–215 mg/mL EC50 RP −1.34–92.9 % BCB | HPLC-UV | [43] |

| 7 | Multiflora | M.(Michmelia) seminigra merrilae | Brazil | 17.0–66.0 mg GAE/g | n.d. | 210–337 mg TE/mL EC50 ABTS | HPLC-DAD | [87] |

| 4 | Manuka | n.s. | New Zealand | 372–576 mg GAE/kg | n.d. | 545–756 μmol Fe2+/100g FRAP | n.d. | [88] |

| 460 | Monoflora | n.s. | Italy | 107.2–564.2 mg GAE/kg | 33.1–213 mg QE/kg | 3.4–161.3 mg/mL EC50 DPPH 24.4–72.8 μM AAE/g FRAP | LC-MS | [9] |

| 31 | Multiflora | Meliponinae, 7 spp. | Brazil | 32–136 mg GAE/g | 8–55 mg QE/g | DPPH, BCB, FRAP (graphicated) | n.d. | [89] |

| 20 | Buckwheat | n.s. | Poland | 181–355 mg GAE/100g | 8.0–30.4 mg QE/100g | 51–95.2% DPPH 195–680 μmol TE/100g FRAP | UPLC-PDA-MS/MS | [90] |

| 90 | 44 monoflora, 29 honeydew and 17 multiflora | n.s. | Poland | 254.5–1353.7 mg GAE/kg | n.d. | 21.81–82.41% DPPH 656.73–3635.49 µmol TE/kg FRAP | n.d. | [48] |

| 8 | Carob | n.s. | Morocco | 75.5–245.2 mg GAE/100g | 2.26–4.79 mg QE/100g | 35.03–60.94 mg AAE/g TAA 12.54–23.52 mg/mL EC50 DPPH 1.9–4.4 mg AAE/mL EC50 FRAP | n.d. | [91] |

| 187 | 34 chestnut, 17 eucalyptus, 31 blackberry, 10 heather, 13 honeydew and 82 multiflora | n.s. | Spain | 78.4–181 mg GAE/100g | 4.3–9.6 mg QE/100g | 9.5–17.8 mg AAE/mL EC50 DPPH | n.d. | [92] |

| 32 | Honeydew | n.s. | Spain | 79.5–187 mg GAE/100g | 6.6–13.1 mg QE/100g | 52.9–95.6% DDPH | n.d. | [93] |

| 7 | Forest, pine, urtica, meadow, linden, 2 acacia | n.s. | Serbia, Germany, Greece | 94.0–620.7 µg GAE/ml | n.d. | 0.2–4.98 µmol TE/g FRAP 5.9–12.9 µmol TE/g ORAC 1.0–5.82 µmol TE/g ABTS 0–1.21 µmol TE/g EC50 DPPH | n.d. | [94] |

| 23 | Monoflora | n.s. | Turkey | 45.4–470.7 mg GAE/100g | n.d. | 12.01–65.52 mg/mL EC50 DPPH 0.0022–0.0091 mg TE/100g FRAP 32.09–94.87% BCB. | n.d. | [95] |

| 22 | 20 monoflora, 2 honeydew | n.s. | Poland | 3.43–22.33 mg GAE/100g | n.d. | 41.42–83.16 mg GAE/100g ABTS | HPLC-DAD | [77] |

| 40 | Honeydew “dryomelo” | A. mellifera | Greece | 1221–1495 mg GAE/kg | n.d. | 56.8–72.4% DPPH | n.d. | [96] |

| 11 | 2 tualang, 2 gelam, 2 pineapple, 2 borneo (Apis spp.) and 3 kelulut (Trigona spp.) | Apis spp. and Trigona spp. | Malaysia | 590.5 and 784.3 mg GAE/kg | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | [97] |

| 4 | Tualang, gelam, indian forest, pineapple | n.s. | Malaysia | 27.75–83.96 mg GAE/100g | 24.74–50.45 mg QE/100g | 16.12–53.06 mg AAE/g TAA 5.80–10.86 mg/mL EC50 DPPH 47.92–121.89 μmol Fe2+/100g FRAP | n.d. | [98] |

| 28 | 4 black locust, 5 buckwheat, 4 lime, 2 goldenrod, 3 heather, 10 rapeseed | n.s. | Poland | 121.6–1173.8 mg GAE/kg | n.d. | 0.6–6.7 FRAP mmol Fe2+/kg 0.2–1.4 mmol TE/kg DPPH | HPLC-DAD | [99] |

| 40 | Multiflora, lime, rape, raspberry, mixture, honeydew | n.s. | Czech | 82.5–242.5 mg GAE/kg | n.d. | 141.52–407.08 mg AAE/kg DPPH 489.44–982.93 mg AAE/kg ABTS 295.35–776.05 mg AAE/kg FRAP | n.d. | [100] |

| 9 | 5 orange and 4 multifloral | n.s. | Brazil | 40.36 and 58.05 mg GAE/100g | 0.17 and 1.53 mg QE/100g | 38.54 and 16.62-mg/mL EC50 DPPH | HPLC-DAD | [101] |

| 6 | B. pilosa, D. longan, L. chinensis, C. maxima, A. formosana, and 1 multiflora | n.s. | China | 0.31–0.82 mg GAE/g | 29.7–124 mg QE | 15.2–84.9% DPPH | n.d. | [102] |

| 20 | Monoflora, multiflora and Manuka | n.s. | Florida, New Zealand | 286–1080 µg GAE/g | n.d. | 0.28–2.1 µmol TE/g DPPH 1.48–18.2 µmol TE/g ORAC | HPLC-UV | [103] |

| 4 | n.s. | n.s. | Algeria | 15.84–61.63 mg GAE/100g | 2.07–10.15 mg CE/100g | RP (graphicated) | n.d. | [55] |

| 20 | 4 multiflora, 4 linden, 4 rapeseed, 2 sunflower, 1 phacelia, 3 acacia and 2 honeydew | n.s. | Serbia | n.d. | n.d. | 22.96–79.45% DPPH | n.d. | [72] |

| 49 | 28 eucalyptus, 6 Japanese grape, 5 mastic, 3 quitoco, 1 wildflower, 6 multiflora | A. mellifera | Brazil | 26.0–100.0 mg GAE/100g | 0.65–8.10 mg QE/100g | 1.28–18.48 µmol TE/g ORAC 25.45–294.26 mg/mL EC50 DPPH 0.22–2.11 µmol TE/g FRAP | HPLC-UV | [104] |

| 37 | 11 apple, 8 cherry, 8 saffron and 10 wild bush | n.s. | India | 37–117 mg GAE/100g | 8–17 mg QE/100g | 55–84% DPPH 19–51 mg AAE/100g DPPH | HPLC-DAD | [105] |

| 24 | 7 acacia, 8 pine, 9 multiflora | n.s. | India | 22.68–59.84 mg GAE/100g | 6.10–8.12 mg QE/100g | 52.27–55.37% DPPH 14.13–23.74 mg AAE/100g DPPH | n.d. | [106] |

| 16 | Monoflora | n.s. | Turkey | 170.06–885.43 mg GAE/100g | n.d. | 0.27–2.56 mg/mL EC50 DPPH 0.51–0.62 mmol TE/g | n.d. | [107] |

| 45 | 4 thyme, 10 rape, 10 mint, 6 raspberry, 9 sunflower, 6 multiflora | n.s. | Romania | 18.91–23.71 mg GAE/100g | 17.45–33.58 mg QE/100g | 55.49–79.05% DPPH | HPLC-DAD | [75] |

| 78 | 16 chestnut, 14 eucalyptus, 12 citrus, 18 sulla and 18 multiflora | n.s. | Italy | 10.82–14.67 mg GAE/100g | 5.09–14.05 mg QE/100g | 58.40–60.42% ABTS 152.65–881.34 µM Fe2 FRAP 54.29–78.73% DPPH | n.d. | [39] |

| 14 | Monoflora and 5 multiflora | n.s. | Mexico | 283.9–1142.9 mg GAE/kg | n.d. | 910.2–2927.4 µmol TE/kg ABTS 81.9–255 µmol TE/kg DPPH 749.4–3097.1 µmol Fe2+/kg FRAP | n.d. | [108] |

| 91 | 53 chestnut and 38 honeydew | n.s. | Spain | 125 and 128 mg GAE/100g | 8.4and 9.4 mg QE/100g | 58.4–68.4% DPPH | n.d. | [109] |

| 129 | Loco, opoponax-tree, alfalfa, barberry, thyme, argentine thistle and dill | n.s. | Iran | 33.34–259.52 mg GAE/kg | n.d. | 204.14–1383.18 μmol Fe2+/100g FRAP | n.d. | [110] |

| 39 | Acacia, jujube, vitex, linden, fennel, buckwheat, Manuka | n.s. | China (mainly) | 9.15–294 mg GAE/100g | 6.85–64.8 mg QE/100g | n.d. | UPLC-MS/MS | [19] |

| 50 | Rhododendron | n.s. | Turkey | 20.29–109.19 mg GAE/100g | n.d. | 21.9–58.21 mg AAE/g TAA 36.1–90.73% DPPH | n.d. | [111] |

| 9 | Mimosoideae | M. subnitida | Brazil | 1.2–1.3 mg GAE/g | n.d. | 10.6–12.9 mg/mL EC50 DPPH 6.1–9.7 mg/mL EC50 ABTS 51.5–74.6% BCB | HPLC-DAD | [112] |

| 11 | 7 from A. mellifera and 4 from M. q. anthidioides | A. mellifera and M. q. anthidioides | Brazil | 47.67–341.51 mg GAE/kg | 8.88- 216.29 mg QE/kg | 86.76–180.28 μmol TE/L DPPH 98.43–365.35 μmol Fe2+/L FRAP 1.91–19.71 μmol EBHA/L BCB | n.d. | [113] |

| 24 | Ziziphus joazeiro, Mimosa quadrivalvis L., Mimosa arenosa, Croton heliotropiifolius | M. subnitida and M. scutellaris | Brazil | 31.5–126.6 mg GAE/100g | 1.9–4.2 mg QE/100g | 11.2–46.9% DPPH 23.2–46.9 μmol TE/100g ABTS 8.9–54.3 μmol TE/100g ORAC | HPLC-DAD | [114] |

| 20 | n.s. | n.s. | Turkey | 35.3–1961.5 mg GAE/100g | 5.38–26.75 mg QE/100g | 54.11–68.94% DPPH 58.93–110.54 mg AAE/g TAA | n.d. | [115] |

| 64 | Honeydew | n.s. | Croatia | 0.57–1.6 mg GAE/g | n.d. | 12.2–48.89% DPPH | UHPLC-LTQ OrbiTrap MS and HPLC-DAD-MS/MS | [116] |

| 82 | Monoflora and multiflora | n.s. | Poland | 40.5–177 mg GAE/100g | n.d. | 47.2–83.4% DPPH 0.64–1.46 μmol TE/kg DPPH 6–79% ABTS | n.d. | [117] |

| Sample Size | Botanical Origin 1 | Sample Type | Country | TPC 2 | TFC 3 | AOA 4 | Extraction | Characterization | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Cistus creticus L. (rock rose) | Pollen | Greece | 15.2–60.2 mg GAE/g | 6.0–57.6 mg QE/g | 0.7–233.3% 200 µg/ml EC50 DPPH18.4–77.9% 100 µg/ml EC50 ABTS | Cyclohexane, dichloromethane, butanol and water | n.d. | [127] |

| 1 | n.s. (hives of A. mellifera L. bees) | Pollen | Brazil | 19.69 mg GAE/g | 6.81 mg QE/g | 0.94 mg/ml DPPH 120.1 µmol TE/g ABTS 60.64 mmol Fe2+/g FRAP 91.93% BCB | Ethanol | LC-DAD | [128] |

| 56 | n.s. (hives of A. mellifera L. bees), palynological evaluation performed | Pollen | Brazil | 6.5–29.2 mg GAE/g | 0.3–17.5 mg QE/g | 9.4–155 µmol TE/g DPPH 133–563 µmol TE/g ORAC | Ethanol | HPLC-PDA | [123] |

| 25 | n.s. (hives of Meliponini, 7 spp.) | Pollen | Brazil | 6.9–21 mg GAE/g | 0.3–17 mg QE/g | DPPH, BCB and FRAP (graphicated) | Ethanol | n.d. | [89] |

| 3 | n.s. (hives of T. apicalis, T. itama and T. thoracica) | Pollen | Malaysia | 33.46–135.93 mg GAE/g | 15.28–31.80 mg QE/g | 0.86–3.24 EC50 mg/ml DPPH | Ethanol | n.d. | [129] |

| 1 | n.s., palynological evaluation performed | Pollen | Greece | 10.49 mg PAE/g | n.d. | 181.4 µg/ml EC50 DPPH | methanol | GC-MS | [130] |

| 10 | Heterofloral | Pollen | Turkey | 509–1746 mg GAE/100g | n.d. | 12.3–33.84% DPPH | Water | n.d. | [131] |

| 4 | Camellia, rape, rose and lotus | Pollen | China | 6.82–62.35 mg GAE/g | n.d. | DPPH, RP and ABTS (graphicated) | Petroleum ether, ethyl acetate, n-butanol and water | HPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS/MS | [132] |

| 5 | Heterofloral, palynological evaluation performed | Pollen | Portugal | 10.5–16.8 mg GAE/g | n.d. | 2.16–5.87 mg/ml EC50 DPPH 3.11–6.52 mg/ml BCB | Methanol | n.d. | [133] |

| 8 | Heterofloral | Pollen | Portugal-Spain | 5.57–15 mg GAE /g | n.d. | 119–276.8 µM TE/g ABTS | Methanol | n.d. | [118] |

| 13 | n.s. | Pollen | Turkey | 44.07–124.1 mg GAE/g | n.d. | 11.77–105.06 µmol TE/g EC50 FRAP 0.65–8.2 mg/ml EC50 DPPH 33.1–86.8 µmol TE/g CUPRAC | Methanol | HPLC-UV | [134] |

| 40 | Heterofloral | Pollen | Poland | 5.57–15.0 mg GAE/g | n.d. | 119–276.8 µM TE/g ABTS | Methanol-water (70%, v/v) | Raman and FTIR | [135] |

| 4 | n.s. | Bee bread | Lithuania | 306–394 mg GAE/100g | n.d. | 85–93% DPPH | Ethanol | HPLC-UV | [6] |

| 1 | n.s. | Bee bread | Morocco | n.d. | n.d. | 143 mg AAE/g TAA 0.19 mg/ml EC50 RP 0.5 mg/ml EC50 ABTS 0.98 mg/ml EC50 DPPH | Methanol-water (80:20 v/v) | LC-DAD–ESI/MS | [124] |

| 5 | n.s. | Bee bread | Ukraine | 12.36–25.44 mg GAE/g | 13.56–18.24 µg QE/g | DPPH and TAA (graphicated) | Ethanol | n.d. | [136] |

| 3 | n.s. | Bee bread | Poland | 32.78–37.15 mg GAE/g | n.d. | 0.56–1.1 mmol/L ABTS (Randox test) | Ethanol | GC-MS | [21] |

| 15 | n.s. (hives of A. mellifera L. bees) | Bee bread | Colombia | 2.5–13.7 mg GAE/g | 1.9–4.5 mg QE/g | 35.0–70.1 mmol TE/g FRAP 46.1–76.3 µmol TE/g ABTS | Ethanol | n.d. | [121] |

| Sample Size | Botanical Origin/Bee Species 1 | Propolis Type | Country | TPC 2 | TFC 3 | AOA 4 | Extraction | Characterization | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H. itama | n.s. | Brunei | n.d. | n.d. | 12.75–317.65 mg AAE/g DPPH | Ethanol-water mixtures with different volume fractions (from 0.0 to 1.0) of ethanol (96%). | n.d. | [140] |

| 4 | n.s. | n.s. | Lithuania | 211–298 mg GAE/100g | n.d. | 32–80% DPPH | Ethanol | HPLC-UV | [6] |

| 2 | n.s. | green and brown | Brazil | 31.88–204.30 mg GAE/g | n.d. | 21.50–78.77 µg/mL EC50 DPPH | Ethanol- hexane-dichloromethane | GC-MS | [141] |

| 1 | M. orbignyi | n.s. | Brazil | 211 mg GAE/100g | 23 mg QE/100g | 40 µg/mL EC50 DPPH | Ethanol (80%) | n.d. | [32] |

| 6 | A. mellifera | n.s. | Chile | 1.3–1.6 µM CAE/mg | n.d. | 0–7.3 µM CAE/mg ORAC-PGR 8.9–33.1 µM CAE/mg ORAC-FL 1.8–3.2 µM CAE/mg FRAP | Ethanol (90%) “wax free” | HPLC-UV-ESI-MS/MS | [142] |

| 1 | n.s. | green | Brazil | 57.9–1614.8 mg GAE/g | n.d. | 21.3–13244.5 µmolTE/g ORAC 408.6–13412.1 µmol TE/g ABTS | Best using 99% ethanol solution, 1:35 propolis:solvent ratio (w/v), over 20 min | n.d. | [143] |

| 33 | n.s. | n.s. | Brazil | n.d. | n.d. | 61.9–1770 µmol Fe2+/g FRAP | Ethanol (80%) | FTNIR | [144] |

| 1 | n.s. | n.s. | Brazil | n.d. | n.d. | 14.95–112.12 mg QE/g DPPH 0–36.28 mg QE/g β-carot | Hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate and methanol | GC–EI-MS HPLC–DAD–ESI-MS/MS and NMR | [145] |

| 6 | A. mellifera | n.s. | 3 Romania, 2 Spain, 1 Honduras | 97–442 mg GAE/g | n.d. | n.d. | Ethanol (70%) | HPLC-UV | [146] |

| 10 | M. mondury, M. quadrifasciata, M. scutellaris, M. seminigra, T. angustula | n.s. | Brazil | 32.15–2968.54 mg GAE/100g | n.d. | 176.07–5847.61 mg AAE/g o 258.24–8582.47 mg TE/100g DPPH both | Ethanol and methanol | n.d. | [147] |

| 4 | n.s. | n.s. | Portugal | n.d. | n.d. | 14.41–25.24 ug/mL EC50 DPPH 161.73–251.83 ug/mL EC50 SOD 118.87–158.14 ug/mL EC50 Fe2+chel | Ethanol | UPLC-DAD-ESI/MS | [148] |

| 1 | n.s. | n.s. | India | 269.1 and 159.1 mg GAE/g | 25.50 and 57.25 mg QE/g | 0.05 and 0.07 mg/mL EC50 DPPH | Ethanol (70%) and water | n.d. | [149] |

| n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | Portugal | 5.28–6.27 mg Pinocembrin/mL | 1.27–1.30 mg QE/mL | 0.019–0.020 mg/mL EC50 ABTS 0.027–0.031 mg/mL EC50 DPPH 0.034–0.034 mg/mL EC50 SOD 39.5–49.9% Fe2+chel | Methanol, ethanol (70%) and water | n.d. | [150] |

| 3 | n.s. | n.s. | Algeria | 15.84–61.63 mg GAE/100g | 124.76–4946.53 mg CE/100 | n.d. | Water, 50% ethanol, 85% ethanol, and 50%methanol | n.d. | [55] |

| 11 | n.s. | n.s. | Turkey | 2748–19970 mg GAE/100g | 3073–29175.0 mg QE/100g | 1370.6–6332.9 mg TE/100g DPPH 2461.6–8580.3 mg TE/100g CUPRAC | Ethanol (70%) | LC-MS/MS | [151] |

| 5 | n.s. | n.s. | Serbia | 1.45–5.31 g GAE/100mL | n.d. | 0.093–0.346% EC50 DPPH | Ethanol | n.d. | [152] |

| 48 | n.s. | Poplar “orange”, “blue” and “third type” | Turkey | 486.9 mg GAE/g orange 310.6 mg GAE/g blue 115.7 mg GAE/g third | 265.7 mg QE/g orange 185.5 mg QE/g blue 109.53 mg QE/g third | 65.64 %DPPH orange 42.22 %DPPH blue 26.49 %DPPH third | Ethanol (80%) | UHPLC–LTQ/orbitrap/MS/MS | [153] |

| 1 | n.s. | n.s. | India | 5.15–20.99 mg GAE/g | 8.39–14.26 mg QE/g | n.d. | Ethanol | HPTLC | [154] |

| 9 | A. mellifera, palynological identification | n.s. | Portugal | 18.52–277.17 mg GAE/mL | 6.34–142.32 mg CE/mL | n.d. | Water, methanol:water (80%) and ethanol:water (80%) | UV-VIS | [155] |

| 5 | n.s. | n.s. | Iraq | 700–9333 µg CAE/mL | n.d. | 40.0–83.3% DPPH | Methanol | HPLC–ESI/MS | [156] |

| 1 | T. itama | n.s. | Malaysia | n.d. | n.d. | 90.7–99.34 % DPPH | Subsequent extractions: hexane, ethyl acetate and methanol | UV-VIS | [157] |

| Sample Size | Botanical Origin/Bee Species 1 | Sample Type | Country | TPC 2 | TFC 3 | AOA 4 | Extraction | Characterization | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beeswax | |||||||||

| 1 | A. mellifera | Hydro-ethanolic extracts of honeycomb | China | 1.62 mg GAE/g | 1.62 mg/g (equivalent n.s.) | 5.91 mg/ml EC50 DPPH 1.33 mg TE/g FRAP 0.38 mg Na2EDTA/g Fe2+chel. | Ethanol 75% | GC–MS | [161] |

| 10 | A. mellifera | Waste sediment separated from wax (5 MUD1 and 5 MUD2) | n.s. | 1435.66 and 432.66 mg GAE/100g | 295.84 and 142.17 mg CE/100g | 1.60 and 0.23 mM TE TEAC 1.93–0.59 mM TE FRAP | Sediment with inorganic and organic waste was separated from wax honeycombs during recycling process following a heating process by steam (MUD1); the remaining wax was passed to a continuous decanter, where a fine sediment was generated (MUD2). | UPLC-DAD/ESI-MS | [20,162] |

| Royal jelly | |||||||||

| 1 | A. mellifera | Recombinant MRJPs 1–7 | South Korea | n.d. | n.d. | DPPH (about 30–80%-graphicated) | n.s. | n.d. | [29] |

| 28 | A. mellifera | 19 local and 9 commercial RJ | Romania | 23.49 and 23.25 mg GAE/g | n.d. | 37.23 and 35.94% DPPH 2.20 and 1.83 mM Fe2+/g FRAP | Water 10% (w/v) | n.d. | [163] |

| Venom | |||||||||

| 1 | A. mellifera syriaca | Venom | Lebanon | n.d. | n.d. | 50–86.6% DPPH (from 2.5 to 500 µg/mL) | Lyophilized crude venom dissolved in 1 mL water (5 mg/mL) | LC-ESI-MS | [164] |

| 5 | A. mellifera iberiensis | Venom | Portugal | n.d. | n.d. | 346–512 µg/mL EC50 DPPH 238–326 µg/mL EC50 RP 435–826 µg/mL EC50 BCB | Water (mg/mL) | LC/DAD/ESI-MS | [165] |

| 4 | A. mellifera, A. cerana, A. florea, A. dorsata | Venom | Thailand | n.d. | n.d. | DPPH, FRAP and ABTS (graphicated) | Various concentrations in PBS | HPLC-UV | [166] |

| Bee Product | Bees Species 1 | Cell culture/Substrate | Antioxidant Activity | Measurement | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Honey | |||||

| Monofloral honeys (Italy) | A. mellifera | Bovine brain microsomes | Peroxyl-radical scavenging capacity | Time-course of TBA-RS formation during microsomal oxidation | [74] |

| Commercial multifloral honey (Italy) | A. mellifera | Human endothelial cell line (EA.hy926) | Cell membrane oxidation, intracellular oxidative damage, cell viability using MTT [3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl) -2,5-diphenyl -2H- tetrazolium bromide] assay and GSH analysis | Cytoprotective activity by fluorimetric determination, cell viability (the absorbance is proportional to the number of living cells) and microscopic evaluation | [16] |

| Buckwheat and Manuka honeys | n.s. | HepG2 cell lines, Cell Bank of Institute of the Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China | Cellular antioxidant activity (CAA) and cytotoxicity assay | Peroxyl radical-induced oxidation of DCFH to DCF by fluorimetric determination and inhibition of oxidation by honey extracts (microscopic evaluation) | [17] |

| Malaysian kelulut honey | Trigona spp. | Lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL), AGRE, Los Angeles, CA, USA | Ferric-reducing antioxidant potential assay, total phenolic, and flavonoid content by UV spectrophotometry. Cell viability using MTS assay | Cell viability (%) reading the absorbance at 490 nm and positively affected by antioxidant properties | [18] |

| Monofloral honeys (China) | A. dorsata | HepG2 cell lines, Stem Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences | Cellular antioxidant activity (CAA) assay | Effective reduction of intracellular oxidative state reacting with peroxyl radicals or ROS/RNS. Fluorimetric determination | [19] |

| Beeswax | |||||

| Beeswax recycling by-product (MUD1) | A. mellifera | HepG2 cells, Biological Research Laboratory of Sevilla University, Spain | ROS concentration using CellROX® Orange Reagent applied according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were analyzed with the Tali® Image-Based cytometer | Intracellular ROS: percentage of cells with increased ROS levels related to the control | [20] |

| Two beeswax recycling by-products (MUD1 and MUD2) | A. mellifera | Adult skin HDF, GIBCO® Invitrogen cell, Waltham, MA, USA | ROS concentration using CellROX® Orange Reagent applied according to manufacturer’s instructions | Intracellular ROS: percentage of cells with increased ROS levels related to the control | [161] |

| Pollen | |||||

| Bee pollen (China) | n.s. | Blood from male Kunming mice | Superoxide dismutase (SOD) assay, lipid peroxidation index assay and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) assay | Spectrophotometric measurement of SOD content (U/mL), MDA content (nmol/mL) and inhibition rate (%) | [30] |

| Bee pollen from Jara pringosa (Sistus ladanifer) and Jara blanca (Cistus albidus) (Spain) | A. mellifera | Retinal ganglion cells (RGC-5, a rat ganglion cell-line transformed using E1A virus) | Antioxidant-capacity assay-measured the radicals induced in RGC-5 by the application of ROS (H2O2, O2•−, and HO) | Intracellular ROS: time-kinetic and concentration-response data for bee pollen towards production of various ROS in term of fluorescence intensity | [22] |

| Commercial pollens of different floral sources and geographical origins | n.s. | Livers obtained from pigs and homogenized | Inhibition of lipid peroxidation using thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) | Spectrophotometric determination of inhibition ratio (%) and EC50 calculated (0.35–3.70 TBARS mg/mg extract) | [118] |

| Bee bread | |||||

| Beebread (Poland) | n.s. | Human glioblastoma cell line U87MG (HTB-14), ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA | Cytotoxicity evaluated by MTT assay. Total antioxidative ability related to phenolic and non-phenolic compounds after 24 h | Viability of U87MG (% of the control) after incubation with beebread, measuring the absorbance at 570 nm | [21] |

| Propolis | |||||

| Propolis | n.s. | Human erythrocytes from peripheral blood | Estimation of the inhibitory efficiency of propolis extracts on H2O2-induced lipid peroxidation using thiobarbituric acid (TBA) assay and protective effect of propolis extracts on H2O2-induced oxidative hemolysis | Measured the absorbance of the supernatant at 532 nm and calculated the hemolysis percentage | [47] |

| Propolis (Brazil) | M. orbignyi | Human erythrocytes from peripheral blood | Oxidative hemolysis inhibition assay, inhibitory efficiency against lipid peroxidation, cytotoxic activity and cell death profile (analysis performed using propidum iodide and annexin V-FITC dual staining) | Hemolysis (%), MDA (nmol/mL) and cell viability (%), respectively, spectrophotometrically determined and flow cytometric evaluation of death profile | [32] |

| Propolis (Portugal) | n.s. | Eukaryote unicellular model organism S. cerevisiae and human reconstituted skin tissue model (EpiDermTM EPI-200) | Evaluation of propolis protective effects against H2O2-induced oxidative stress and its influence on ROS intracellular levels in S. cerevisiae cells. UVB-induced overexpression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), quantitative real-time PCR and immunohistochemistry (IHC) in skin tissue model | Viability and intracellular oxidation of S. cerevisiae cells analyzed for fluorescence by flow cytometry. Evaluation of the UVB-induced photoaging by immunohistochemistry and quantification of mRNA levels of MMPs | [142] |

| Propolis (Greece) | n.s. | Human immortalized keratinocyte (HaCaT) cell line, ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA | Determination of antioxidant capacity in cell lysates and assessment of protein oxidation by measuring the protein carbonyl colorimetric assay | DNA damage (AU) using fluorescence microscope, total antioxidant content and protein carbonyl content, spectrophotometrically determined | [23] |

| Propolis (Thailand) | n.s. | A549 human lung epithelial cells and HeLa cervical cancer cells | Determination of antioxidant activity by DPPH method and cytotoxicity by MTT assay | Extraction-method dependent antioxidant and flavonoid compounds. Cell shrinkage and floating in medium. Percentage of viability compared to the cell control | [24] |

| Propolis (Turkey) | n.s. | Human foreskin fibroblast cells (CRL-2522), ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA | Spectrofluorometric analysis of intracellular oxidative stress with CM-H2DCFDA | ROS levels measured by spectrofluorometric method | [25] |

| Brazilian green propolis from Baccharis dracunculifolia (Minas Gerais State, Brazil) | A. mellifera | Retinal ganglion cells (RGC-5, a rat ganglion cell-line transformed using E1A virus) | Antioxidant-capacity assay measured the radicals induced in RGC-5 by the application of ROS (H2O2, O2·-, and HO) | Intracellular ROS: time-kinetic and concentration-response data for propolis towards production of various ROS in terms of fluorescence intensity | [22] |

| Red propolis (Brazil) | n.s. | Human tumor cell lines HL-60 (leukemia), PC3 (prostate carcinoma), SNB19 (glioblastoma), and HCT-116 (colon carcinoma), National Cancer Institute, USA | High in vitro antioxidant activity related to total phenolic and flavonoid compound content. MTT assay to determine the cytotoxic (antitumor) potential of the extracts | Growth inhibition of tumor cell lines (%), using spectrophotometer | [26] |