Neuroinflammation-Modulating Properties Combining Glutathione, N-Acetylcysteine, and Uridine Monophosphate in a Formulation Supplement: An In Vitro Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

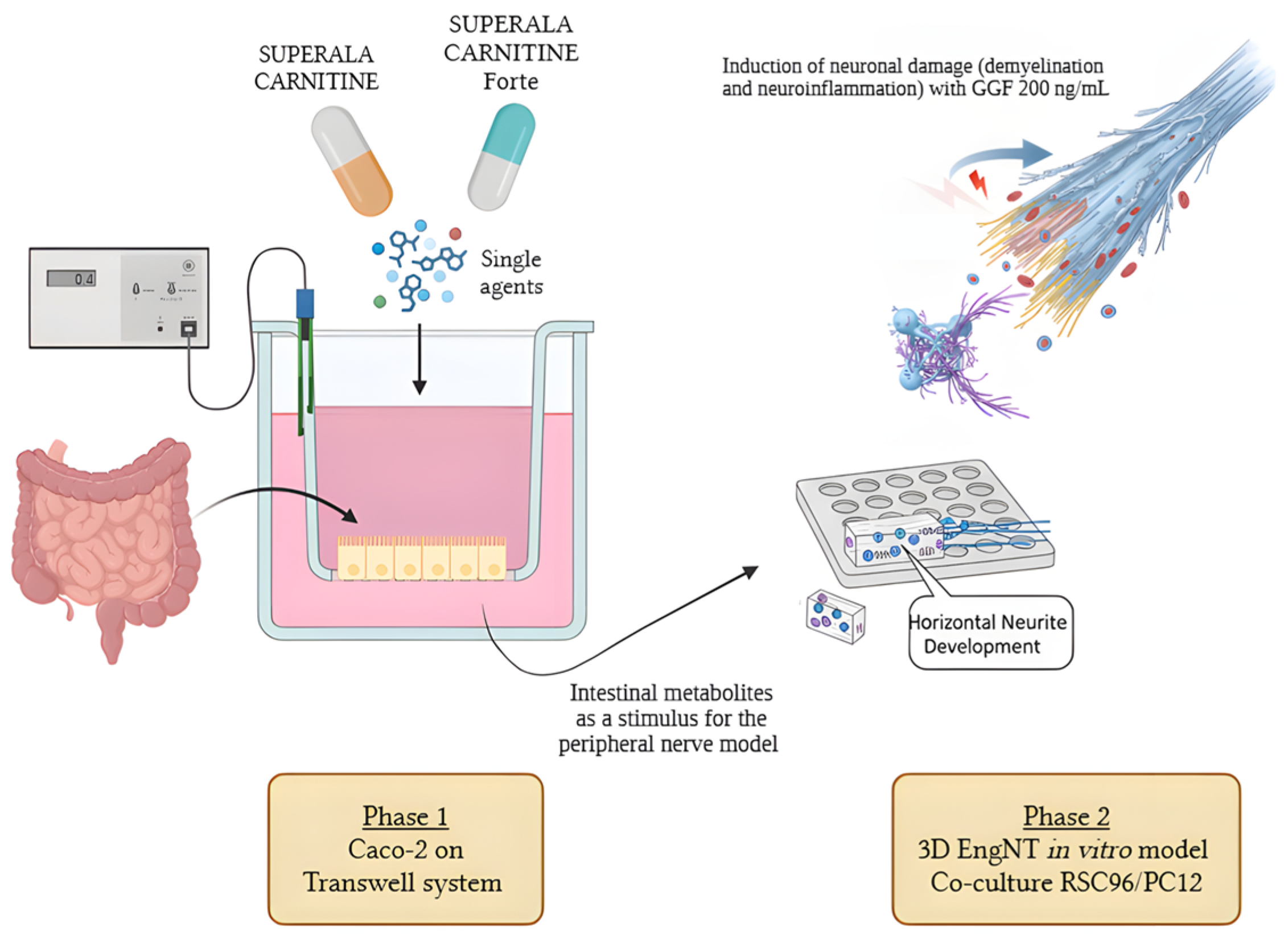

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Agents’ Preparation

2.2. Cell Cultures

2.3. Experimental Protocol

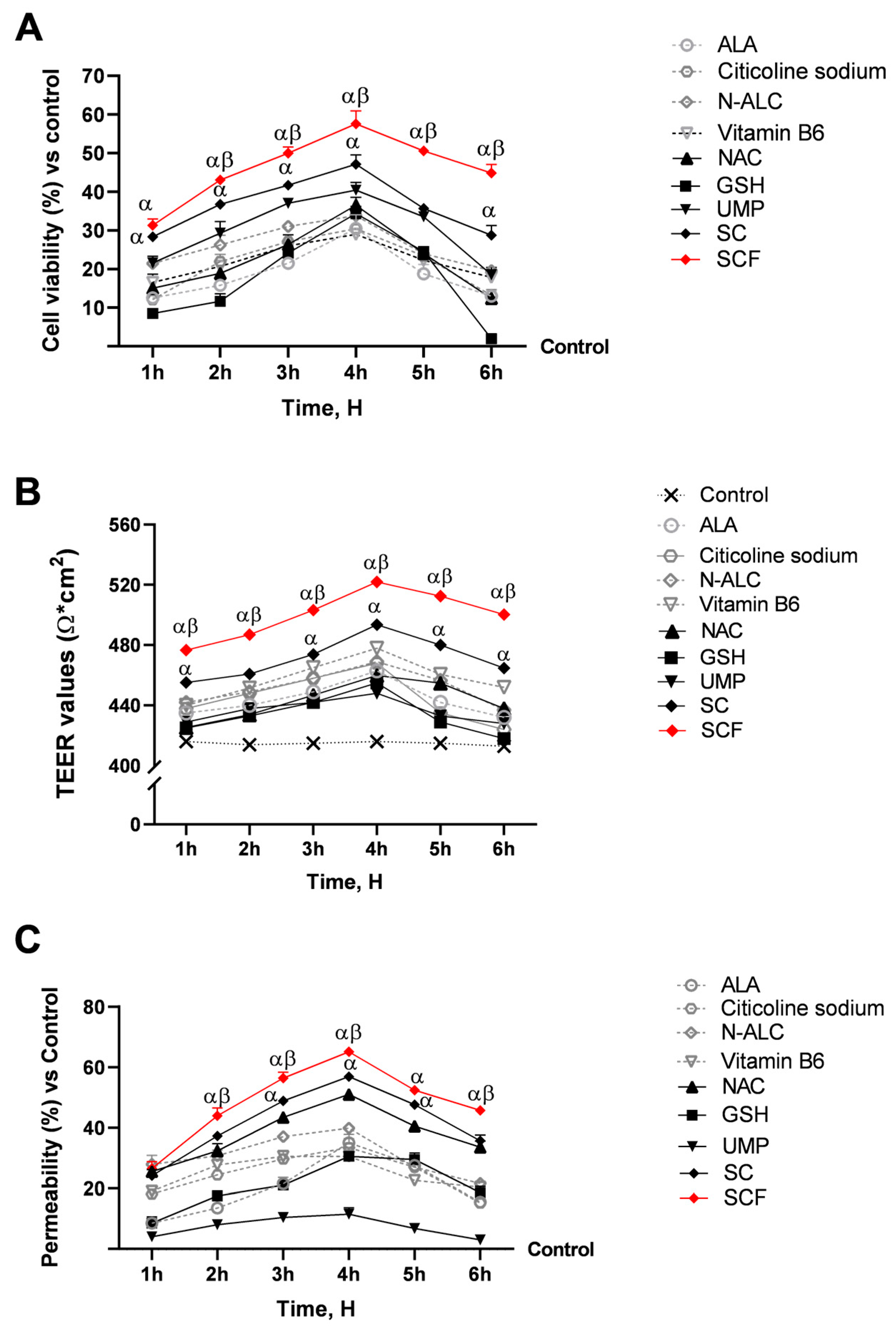

2.4. In Vitro Intestinal Barrier Model

- -

- Jmax: the maximum permeation rate;

- -

- [C]: the initial concentration of fluorescein;

- -

- Kt: the Michaelis–Menten constant.

2.5. Cell Viability (MTT Test)

2.6. 3D EngNT In Vitro Model

2.7. ROS Production

2.8. General Procedure for ELISA Assays

2.8.1. TNFα Production ELISA Kit

2.8.2. IL-2 Production ELISA Kit

2.8.3. GABA ELISA Assay

2.8.4. MPZ ELISA Assay

2.8.5. p75 Expression by NGFR ELISA Assay

2.8.6. ERβ ELISA Assay

2.8.7. Neuregulin 1 (NRG1) ELISA Assay

2.8.8. NaV 1.7 ELISA Assay

2.8.9. NaV 1.8 ELISA Assay

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Formulations’ and Their Individual Components’ Biological Effects at the Level of a 3D In Vitro Intestinal Barrier Model

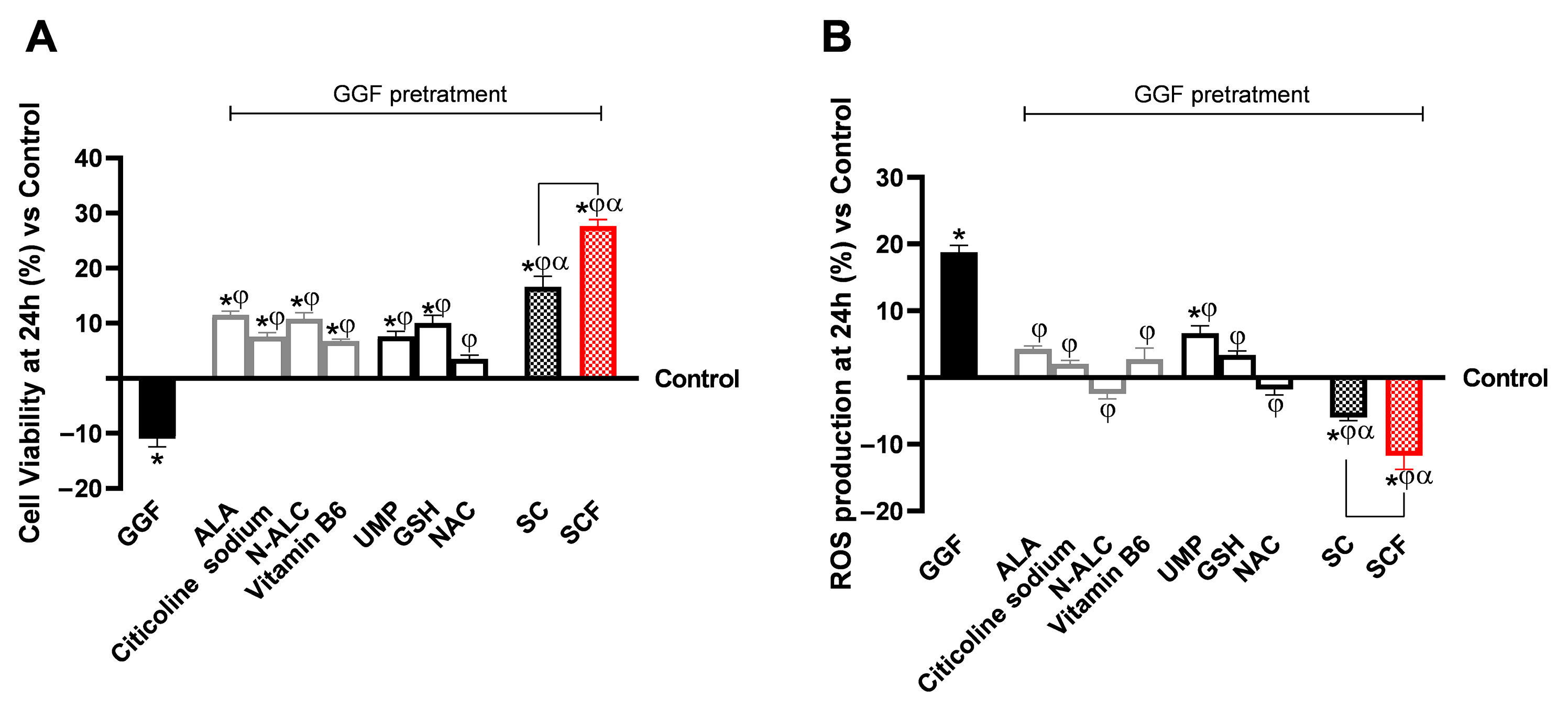

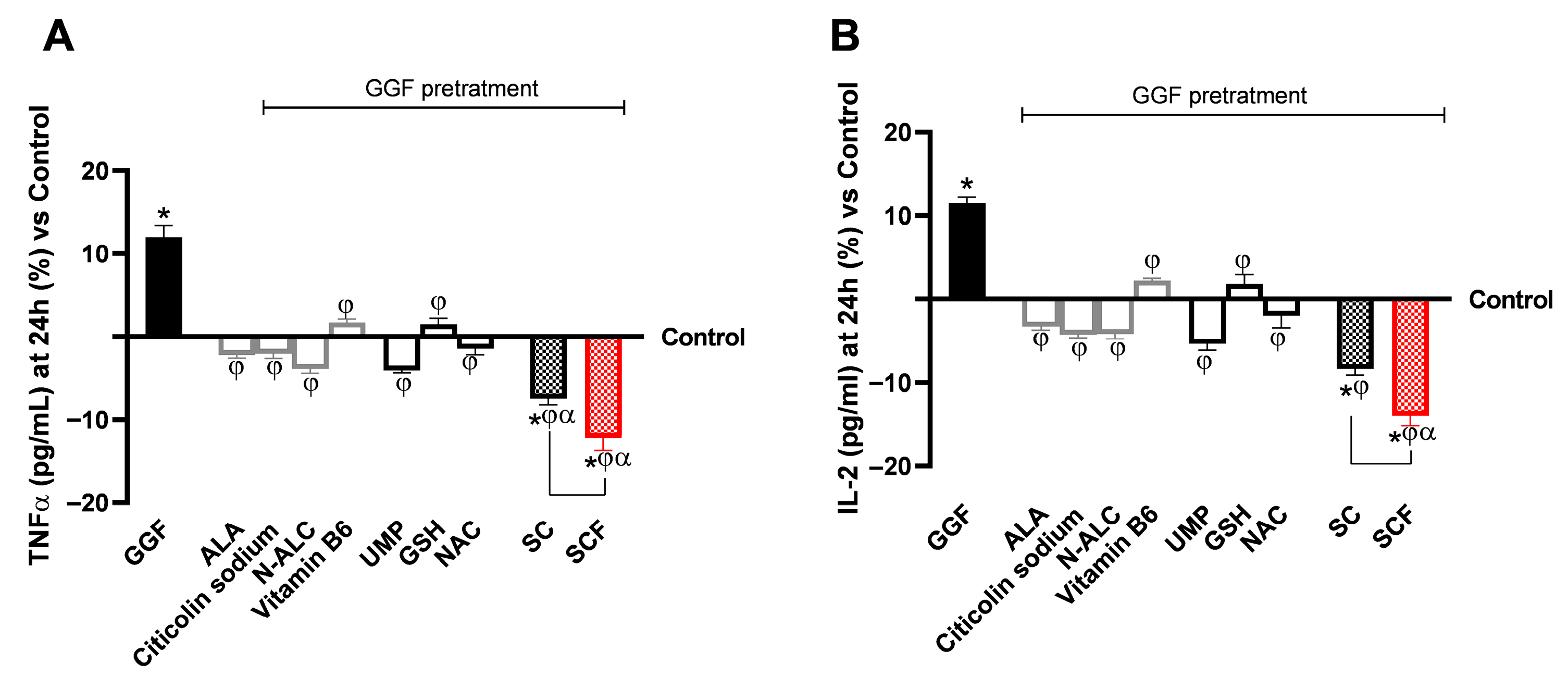

3.2. Analysis of the Biological Effects of Single Substances and Formulations at the Level of a 3D Model of the Peripheral Nerve

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Adv DMEM-F12 | Advanced Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium/Nutrient F-12 Ham’s |

| Adv RPMI | Advanced Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium |

| Adv DMEM | Advanced Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| ALA | Alpha-Lipoic Acid |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| CB2R | Cannabinoid Receptor 2 |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| DMEM-F12 | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium/Nutrient F-12 Ham’s |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| EngNT | Engineered Neural Tissue |

| ERβ | Estrogen Receptor β |

| FBS | Foetal Bovine Serum |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GABA | Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid |

| GGF | Glial Growth Factor |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| IASP | International Association for the Study of Pain |

| IKK | IKappa kinase |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| IL-2 | Interleukin 2 |

| MPZ | Myelin Protein Zero |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide |

| N-ALC | N-Acetyl L-Carnitine |

| NAC | N-Acetylcysteine |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NRG1 | Neuregulin 1 |

| OS | Oxidative Stress |

| PNS | Peripheral Nervous System |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SC | SUPERALA CARNITINE® |

| SCF | SUPERALA CARNITINE® Forte |

| TEER | Trans-Epithelial Electrical Resistance |

| TJ | Tight Junction |

| TNFα | Tumour Necrosis Factor α |

| UMP | Uridine monophosphate |

References

- Jensen, T.S.; Baron, R.; Haanpää, M.; Kalso, E.; Loeser, J.D.; Rice, A.S.C.; Treede, R.-D. A New Definition of Neuropathic Pain. Pain 2011, 152, 2204–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, J.; Finnerup, N.B.; Attal, N.; Aziz, Q.; Baron, R.; Bennett, M.I.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Cruccu, G.; Davis, K.D.; et al. The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for ICD-11: Chronic Neuropathic Pain. Pain 2019, 160, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulsebosch, C.E.; Hains, B.C.; Crown, E.D.; Carlton, S.M. Mechanisms of Chronic Central Neuropathic Pain after Spinal Cord Injury. Brain Res. Rev. 2009, 60, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernazza, S.; Tirendi, S.; Bassi, A.M.; Traverso, C.E.; Saccà, S.C. Neuroinflammation in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angst, M.S.; Clark, J.D.; Carvalho, B.; Tingle, M.; Schmelz, M.; Yeomans, D.C. Cytokine Profile in Human Skin in Response to Experimental Inflammation, Noxious Stimulation, and Administration of a COX-Inhibitor: A Microdialysis Study. Pain 2008, 139, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chizh, B.A.; Greenspan, J.D.; Casey, K.L.; Nemenov, M.I.; Treede, R.-D. Identifying Biological Markers of Activity in Human Nociceptive Pathways to Facilitate Analgesic Drug Development. Pain 2008, 140, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, A.; Jamroz-Wiśniewska, A.; Haratym, N.; Rejdak, K. Neuropathic Pain and Chronic Pain as an Underestimated Interdisciplinary Problem. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2022, 35, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Hoogen, N.J.; Harding, E.K.; Davidson, C.E.D.; Trang, T. Cannabinoids in Chronic Pain: Therapeutic Potential Through Microglia Modulation. Front. Neural Circuits 2022, 15, 816747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Albrecht, M.A.; Wurtman, R.J. Dietary supplementation with uridine-5′-monophosphate (UMP), a membrane phosphatide precursor, increases acetylcholine level and release in striatum of aged rat. Brain Res. 2007, 1133, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendaszewska-Darmach, E.; Węgłowska, E.; Walczak-Drzewiecka, A.; Karaś, K. Nucleoside 5′-O-monophosphorothioates as modulators of the P2Y14 receptor and mast cell degranulation. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 69358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, E.C.; Luiz, A.P.; Wood, J.N. Nav1.7 and Other Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels as Drug Targets for Pain Relief. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2016, 20, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnerup, N.B.; Kuner, R.; Jensen, T.S. Neuropathic Pain: From Mechanisms to Treatment. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 259–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Egidio, F.; Lombardozzi, G.; Kacem Ben Haj M’Barek, H.E.; Mastroiacovo, G.; Alfonsetti, M.; Cimini, A. The Influence of Dietary Supplementations on Neuropathic Pain. Life 2022, 12, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, G.F.; Rocha, L.W.; Quintão, N.L.M. Nutraceuticals, Dietary Supplements, and Functional Foods as Alternatives for the Relief of Neuropathic Pain. In Bioactive Nutraceuticals and Dietary Supplements in Neurological and Brain Disease; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Giorgi, V.; Di Lascio, S.; Fornasari, D. Acetyl-L-Carnitine in Chronic Pain: A Narrative Review. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 173, 105874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hota, K.B.; Hota, S.K.; Chaurasia, O.P.; Singh, S.B. Acetyl-L-carnitine-mediated Neuroprotection during Hypoxia Is Attributed to ERK1/2-Nrf2-regulated Mitochondrial Biosynthesis. Hippocampus 2012, 22, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.-J.; Lin, J.-S.; Lin, Y.-C.; Lin, P.-T. Effects of L-Carnitine Supplementation on Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Enzymes Activities in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofrj, M.; Ciccocioppo, F.; Varanese, S.; di Muzio, A.; Calvani, M.; Chiechio, S.; Osio, M.; Thomas, A. Acetyl-L-carnitine: From a biological curiosity to a drug for the peripheral nervous system and beyond. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2013, 13, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, I.; Endres, J.R. Citicoline: A Novel Therapeutic Agent with Neuroprotective, Neuromodulatory, and Neuroregenerative Properties. Nat. Med. J. 2010, 2, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalu, S.; Saber, S.; Ramadan, A.; Elmorsy, E.A.; Hamad, R.S.; Abdel-Reheim, M.A.; Youssef, M.E. Unveiling Citicoline’s Mechanisms and Clinical Relevance in the Treatment of Neuroinflammatory Disorders. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e70030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, M.D.M.; Lauria, P.S.S.; de Lima, A.A.; Opretzka, L.C.F.; Marcelino, H.R.; Villarreal, C.F. Alpha-Lipoic Acid as an Antioxidant Strategy for Managing Neuropathic Pain. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibullo, D.; Li Volti, G.; Giallongo, C.; Grasso, S.; Tomassoni, D.; Anfuso, C.D.; Lupo, G.; Amenta, F.; Avola, R.; Bramanti, V. Biochemical and Clinical Relevance of Alpha Lipoic Acid: Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity, Molecular Pathways and Therapeutic Potential. Inflamm. Res. 2017, 66, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Berkay Yılmaz, Y.; Antika, G.; Boyunegmez Tumer, T.; Fawzi Mahomoodally, M.; Lobine, D.; Akram, M.; Riaz, M.; Capanoglu, E.; Sharopov, F.; et al. Insights on the Use of α-Lipoic Acid for Therapeutic Purposes. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Singh, T.G.; Dahiya, R.S.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. α-Lipoic Acid, an Organosulfur Biomolecule a Novel Therapeutic Agent for Neurodegenerative Disorders: An Mechanistic Perspective. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 1853–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffa, S.; Improta, I.; Rocchetti, S.; Mezza, T.; Giaccari, A. Potential Cause-Effect Relationship between Insulin Autoimmune Syndrome and Alpha Lipoic Acid: Two Case Reports. Nutrition 2019, 57, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappellani, D.; Sardella, C.; Campopiano, M.C.; Falorni, A.; Marchetti, P.; Macchia, E. Spontaneously Remitting Insulin Autoimmune Syndrome in a Patient Taking Alpha-Lipoic Acid. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. Case Rep. 2018, 2018, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, M.; Ippoliti, I.; Poluzzi, E.; Antonazzo, I.C.; Moro, P.A.; Moretti, U.; Menniti-Ippolito, F.; Mazzanti, G.; De Ponti, F.; Raschi, E. Assessment of adverse reactions to α-lipoic acid containing dietary supplements through spontaneous reporting systems. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubaker, S.A.; Alonazy, A.M.; Abdulrahman, A. Effect of Alpha-Lipoic Acid in the Treatment of Diabetic Neuropathy: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e25750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, R.Y.; Huang, I.C.; Chen, C.; Sung, J.Y. Effects of Oral Alpha-Lipoic Acid Treatment on Diabetic Polyneuropathy: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Su, Y.; Yi, D.; Wu, C.; Fang, W.; Wang, C. Analysis of the clinical characteristics of insulin autoimmune syndrome induced by alpha-lipoic acid. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2021, 46, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, N.; Miyamura, N.; Nishida, K.; Motoshima, H.; Taketa, K.; Araki, E. Possible relevance of alpha lipoic acid contained in a health supplement in a case of insulin autoimmune syndrome. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2007, 75, 366–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryeal Hahm, J.; Kim, B.-J.; Kim, K.-W. Clinical Experience with Thioctacid (Thioctic Acid) in the Treatment of Distal Symmetric Polyneuropathy in Korean Diabetic Patients. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2004, 18, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, T.; Bai, J.; Liu, W.; Hu, Y. THERAPY OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of α-Lipoic Acid in the Treatment of Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2012, 167, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulè, S.; Ferrari, S.; Rosso, G.; Brovero, A.; Botta, M.; Congiusta, A.; Galla, R.; Molinari, C.; Uberti, F. The Combined Antioxidant Effects of N-Acetylcysteine, Vitamin D3, and Glutathione from the Intestinal–Neuronal In Vitro Model. Foods 2024, 13, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenório, M.C.d.S.; Graciliano, N.G.; Moura, F.A.; de Oliveira, A.C.M.; Goulart, M.O.F. N-Acetylcysteine (NAC): Impacts on Human Health. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulè, S.; Ferrari, S.; Galla, R.; Uberti, F. Neuroprotective Pathway Modulation by a Novel Coriandrum sativum, N-Acetylcysteine and Glutathione-Based Formulation: Insights from In Vitro 3D Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andó, R.; Méhész, B.; Gyires, K.; Illes, P.; Sperlágh, B. A Comparative Analysis of the Activity of Ligands Acting at P2X and P2Y Receptor Subtypes in Models of Neuropathic, Acute and Inflammatory Pain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 159, 1106–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrão, L.; Nunes, P. Uridine Monophosphate, Folic Acid and Vitamin B12 in Patients with Symptomatic Peripheral Entrapment Neuropathies. Pain Manag. 2016, 6, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, A.; Krämer, J.; Carvalho, C.d.S.; Lehr, C.-M. In Vitro–In Vivo Correlation: Shades on Some Non-Conventional Dosage Forms. Dissolut. Technol. 2015, 22, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrijevic, D.; Fabian, E.; Nicol, B.; Funk-Weyer, D.; Landsiedel, R. Toward Realistic Dosimetry In Vitro: Determining Effective Concentrations of Test Substances in Cell Culture and Their Prediction by an In Silico Mass Balance Model. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 1962–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Xia, C.; Huang, Q. Using in vitro and in vivo models to evaluate the oral bioavailability of nutraceuticals. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanazzi, G.; Einheber, S.; Westreich, R.; Hannocks, M.J.; Bedell-Hogan, D.; Marchionni, M.A.; Salzer, J.L. Glial growth factor/neuregulin inhibits Schwann cell myelination and induces demyelination. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 152, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uberti, F.; Morsanuto, V.; Ruga, S.; Galla, R.; Farghali, M.; Notte, F.; Bozzo, C.; Magnani, C.; Nardone, A.; Molinari, C. Study of Magnesium Formulations on Intestinal Cells to Influence Myometrium Cell Relaxation. Nutrients 2020, 12, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galla, R.; Grisenti, P.; Farghali, M.; Saccuman, L.; Ferraboschi, P.; Uberti, F. Ovotransferrin Supplementation Improves the Iron Absorption: An In Vitro Gastro-Intestinal Model. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skolnik, S.; Lin, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.-H.; He, T.; Zhang, B. Towards Prediction of In Vivo Intestinal Absorption Using a 96-Well Caco-2 Assay. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 99, 3246–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, M.L.D.; Laranjeira, S.; Evans, R.E.; Shipley, R.J.; Healy, J.; Phillips, J.B. Developing an In Vitro Model to Screen Drugs for Nerve Regeneration. Anat. Rec. 2018, 301, 1628–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, P.; Lim, W.K. Optimisation of a PC12 Cell-Based in Vitro Stroke Model for Screening Neuroprotective Agents. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiani, A.; Brand-Yavin, A.; Yavin, E.; Lazarovici, P. Neuroprotective Effects of Bioactive Compounds and MAPK Pathway Modulation in “Ischemia”—Stressed PC12 Pheochromocytoma Cells. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fda.Gov. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/117974/download (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Ema.Eu. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ich-m9-biopharmaceutics-classification-system-based-biowaivers scientific-guideline (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Ruga, S.; Galla, R.; Ferrari, S.; Invernizzi, M.; Uberti, F. Novel Approach to the Treatment of Neuropathic Pain Using a Combination with Palmitoylethanolamide and Equisetum arvense L. in an In Vitro Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, S.; Alvarez, S.; Majumder, K. Transport of Dietary Anti-Inflammatory Peptide, γ-Glutamyl Valine (γ-EV), across the Intestinal Caco-2 Monolayer. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubatsch, I.; Ragnarsson, E.G.E.; Artursson, P. Determination of Drug Permeability and Prediction of Drug Absorption in Caco-2 Monolayers. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 2111–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galla, R.; Ruga, S.; Aprile, S.; Ferrari, S.; Brovero, A.; Grosa, G.; Molinari, C.; Uberti, F. New Hyaluronic Acid from Plant Origin to Improve Joint Protection—An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinari, C.; Morsanuto, V.; Ruga, S.; Notte, F.; Farghali, M.; Galla, R.; Uberti, F. The Role of BDNF on Aging-Modulation Markers. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuh, C.M.A.P.; Day, A.G.E.; Redl, H.; Phillips, J. An Optimized Collagen-Fibrin Blend Engineered Neural Tissue Promotes Peripheral Nerve Repair. Tissue Eng. Part A 2018, 24, 1332–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muangsanit, P.; Day, A.; Dimiou, S.; Ataç, A.F.; Kayal, C.; Park, H.; Nazhat, S.N.; Phillips, J.B. Rapidly Formed Stable and Aligned Dense Collagen Gels Seeded with Schwann Cells Support Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. J. Neural Eng. 2020, 17, 046036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, C.; Ruga, S.; Farghali, M.; Galla, R.; Bassiouny, A.; Uberti, F. Preventing C2c12 Muscular Cells Damage Combining Magnesium and Potassium with Vitamin D3 and Curcumin. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2021, 11, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Luan, J.; Jiang, R.P.; Liu, J.; Ma, Y. Myrcene Exerts Anti-Asthmatic Activity in Neonatal Rats via Modulating the Matrix Remodeling. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2020, 34, 2058738420954948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Suhaibani, A.; Ben Bacha, A.; Alonazi, M.; Bhat, R.S.; El-Ansary, A. Testing the Combined Effects of Probiotics and Prebiotics against Neurotoxic Effects of Propionic Acid Orally Administered to Rat Pups. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 4440–4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzemieniec, J.; Litwa, E.; Wnuk, A.; Lason, W.; Gołas, A.; Krzeptowski, W.; Kajta, M. Neuroprotective Action of Raloxifene against Hypoxia-Induced Damage in Mouse Hippocampal Cells Depends on ERα but Not ERβ or GPR30 Signalling. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 146, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulè, S.; Rosso, G.; Botta, M.; Brovero, A.; Ferrari, S.; Galla, R.; Molinari, C.; Uberti, F. Design of Mixed Medicinal Plants, Rich in Polyphenols, Vitamins B, and Palmitoylethanolamide-Based Supplement to Help Reduce Nerve Pain: A Preclinical Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; Mulè, S.; Galla, R.; Brovero, A.; Genovese, G.; Molinari, C.; Uberti, F. Effects of Nutraceutical Compositions Containing Rhizoma Gastrodiae or Lipoic Acid in an In Vitro Induced Neuropathic Pain Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Estacion, M.; Huang, J.; Vasylyev, D.; Zhao, P.; Dib-Hajj, S.D.; Waxman, S.G. Human Na v 1.8: Enhanced Persistent and Ramp Currents Contribute to Distinct Firing Properties of Human DRG Neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2015, 113, 3172–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalli, E.; Mammana, S.; Nicoletti, F.; Bramanti, P.; Mazzon, E. The Neuropathic Pain: An Overview of the Current Treatment and Future Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2019, 33, 2058738419838383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasri, H.; Baradaran, A.; Shirzad, H.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M. New Concepts in Nutraceuticals as Alternative for Pharmaceuticals. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 5, 1487–1499. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Majumdar, S.; Mitra, A.K. Chemical Modification and Formulation Approaches to Elevated Drug Transport across Cell Membranes. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2006, 3, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macedo, L.D.O.; Masiero, J.F.; Bou-Chacra, N.A. Drug Nanocrystals in Oral Absorption: Factors That Influence Pharmacokinetics. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, D.; Lennernäs, H. Intestinal Permeability and Drug Absorption: Predictive Experimental, Computational and In Vivo Approaches. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, D.; Hamilton, G.A.; Ingber, D.E. From 3D Cell Culture to Organs-on-Chips. Trends Cell Biol. 2011, 21, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Brown, P.C.; Chow, E.C.Y.; Ewart, L.; Ferguson, S.S.; Fitzpatrick, S.; Freedman, B.S.; Guo, G.L.; Hedrich, W.; Heyward, S.; et al. 3D Cell Culture Models: Drug Pharmacokinetics, Safety Assessment, and Regulatory Consideration. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 1659–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Ling, J.; Lin, H.; Chen, J. Use of Caco-2 Cell Monolayers to Study Drug Absorption and Metabolism. In Optimization in Drug Discovery; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, B.; Kolli, A.R.; Esch, M.B.; Abaci, H.E.; Shuler, M.L.; Hickman, J.J. TEER Measurement Techniques for In Vitro Barrier Model Systems. SLAS Technol. 2015, 20, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Gardana, C.; Scialpi, A.; Giorgini, G.; Simonetti, P.; Del Bo, C. An in vitro approach to study the absorption of a new oral formulation of berberine. PharmaNutrition 2021, 18, 100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Albuquerque, N.C.P.; Tadini, M.C.; Aguillera Forte, A.L.S.; Ballestero, G.; Teixeira, T.V.; Marquele de Oliveira, F.; Kerros, S. Citrus, Milk Thistle, and propolis extracts improved the intestinal permeability of curcuminoids from turmeric extract—An in silico and in vitro permeability caco-2 cells approach. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 3, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, S.K.; Alam, K.; Kumari, M.; Malootty, R.; Nath, S.; Ravichandiran, V.; Roy, S.; Kaity, S. A 3D in-vitro biomimicking Caco-2 intestinal permeability model-based assessment of physically modified telmisartan towards an alkalizer-free formulation development. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2024, 203, 114480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Song, J.; Shi, X.; Miao, S.; Li, Y.; Wen, A. Absorption and metabolism characteristics of rutin in Caco-2 cells. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 382350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brufani, M.; Figliola, R. (R)-α-lipoic acid oral liquid formulation: Pharmacokinetic parameters and therapeutic efficacy. Acta Biomed. 2014, 85, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ezeriņa, D.; Takano, Y.; Hanaoka, K.; Urano, Y.; Dick, T.P. N-Acetyl Cysteine Functions as a Fast-Acting Antioxidant by Triggering Intracellular H2S and Sulfane Sulfur Production. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018, 25, 447–459.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, T.; Mizugaki, A.; Inoue, Y.; Kato, H.; Murakami, H. Cystine reduces tight junction permeability and intestinal inflammation induced by oxidative stress in Caco-2 cells. Amino Acids 2021, 53, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldini, G.; Altomare, A.; Baron, G.; Vistoli, G.; Carini, M.; Borsani, L.; Sergio, F. N-Acetylcysteine as an Antioxidant and Disulphide-Breaking Agent: The Reasons Why. Free Radic. Res. 2018, 52, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzano, M.C.; DiGuilio, K.; Mercado, J.; Teter, M.; To, J.; Ferraro, B.; Mixson, B.; Manley, I.; Baker, V.; Moore, B.A.; et al. Remodeling of Tight Junctions and Enhancement of Barrier Integrity of the CACO-2 Intestinal Epithelial Cell Layer by Micronutrients. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimlin, L.; Kassis, J.; Virador, V. 3D in Vitro Tissue Models and Their Potential for Drug Screening. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2013, 8, 1455–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, M.; Golding, J.P.; Loughlin, A.J.; Kingham, P.J.; Phillips, J.B. Engineered Neural Tissue with Aligned, Differentiated Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Promotes Peripheral Nerve Regeneration across a Critical Sized Defect in Rat Sciatic Nerve. Biomaterials 2015, 37, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dill, J.; Patel, A.R.; Yang, X.-L.; Bachoo, R.; Powell, C.M.; Li, S. A Molecular Mechanism for Ibuprofen-Mediated RhoA Inhibition in Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galla, R.; Mulè, S.; Ferrari, S.; Grigolon, C.; Molinari, C.; Uberti, F. Palmitoylethanolamide as a Supplement: The Importance of Dose-Dependent Effects for Improving Nervous Tissue Health in an In Vitro Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galla, R.; Ferrari, S.; Mulè, S.; Nebuloni, M.; Calvi, M.; Botta, M.; Uberti, F. Enhancing Nutraceutical Efficacy: The Role of M.A.T.R.I.S. Technology in Modulating Intestinal Release of Lipoic Acid and L-Carnitine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricker, F.R.; Lago, N.; Balarajah, S.; Tsantoulas, C.; Tanna, S.; Zhu, N.; Fageiry, S.K.; Jenkins, M.; Garratt, A.N.; Birchmeier, C.; et al. Axonally Derived Neuregulin-1 Is Required for Remyelination and Regeneration after Nerve Injury in Adulthood. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 3225–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocera, G.; Jacob, C. Mechanisms of Schwann Cell Plasticity Involved in Peripheral Nerve Repair after Injury. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 3977–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kim, A.; Young, A.; Nguyen, D.; Monroe, C.L.; Ding, T.; Gray, D.; Venketaraman, V. The Mechanism and Inflammatory Markers Involved in the Potential Use of N-Acetylcysteine in Chronic Pain Management. Life 2024, 14, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Zhao, Z.Q.; Liu, X.Y. Expression of IL-2 receptor in dorsal root ganglion neurons and peripheral antinociception. Neuroreport 2000, 11, 1433–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Hua, M.; Duan, Y.; Gao, Y.; Shao, X.; Wang, H.; Cheng, C. TNF-α expression in Schwann cells is induced by LPS and NF-κB-dependent pathways. Neurochem. Res. 2012, 37, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.H.; Shurin, G.V.; Khosravi, H.; Kazi, R.; Kruglov, O.; Shurin, M.R.; Bunimovich, Y.L. Immunomodulation by Schwann cells in disease. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2020, 69, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, J.E.; Eskew, O.; Wong, T.; Tchivileva, I.E.; Oladosu, F.A.; O’Buckley, S.C.; Nackley, A.G. Nuclear Factor-Kappa B Regulates Pain and COMT Expression in a Rodent Model of Inflammation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 50, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santus, P.; Signorello, J.C.; Danzo, F.; Lazzaroni, G.; Saad, M.; Radovanovic, D. Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidant Properties of N-Acetylcysteine: A Fresh Perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pajonk, F.; Riess, K.; Sommer, A.; McBride, W.H. N-acetyl-l-cysteine inhibits 26s proteasome function: Implications for effects on NF-κB activation. Free Radic. Bio. Med. 2002, 32, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashtahosseini, Z.; Eslami, M.; Paraandavaji, E.; Haraj, A.; Dowlat, B.F.; Hosseinzadeh, E.; Oksenych, V.; Naderian, R. Cytokine Signaling in Diabetic Neuropathy: A Key Player in Peripheral Nerve Damage. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stefano, G.; Di Lionardo, A.; Galosi, E.; Truini, A.; Cruccu, G. Acetyl-L-carnitine in painful peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review. J. Pain Res. 2019, 2019, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, X.; Xie, X.; Wei, X.; Yu, C.; Cheung, C.W.; Tian, G. N-Acetylcysteine Attenuates Hyperalgesia in Rats with Diabetic Neuropathic Pain: Role of Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Mediators and CXCR4. J. Diabetes Res. 2021, 2021, 8862910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savion, N.; Izigov, N.; Morein, M.; Pri-Chen, S.; Kotev-Emeth, S. S-Allylmercapto-N-acetylcysteine (ASSNAC) protects cultured nerve cells from oxidative stress and attenuates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Neurosci. Lett. 2014, 583, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiechio, S.; Copani, A.; Gereau IV, R.W.; Nicoletti, F. Acetyl-L-carnitine in neuropathic pain: Experimental data. CNS Drugs 2007, 21, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karalija, A.; Novikova, L.N.; Kingham, P.J.; Wiberg, M.; Novikov, L.N. Neuroprotective effects of N-acetyl-cysteine and acetyl-L-carnitine after spinal cord injury in adult rats. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, K.; Kwyer, T.A.; Sataloff, R.T. Implications of Nutraceutical Modulation of Glutathione with Cystine and Cysteine in General Health and Otology. In Occupational Hearing Loss, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pashkova, N.; Peterson, T.A.; Ptak, C.P.; Winistorfer, S.C.; Guerrero-Given, D.; Kamasawa, N.; Ahern, C.A.; Shy, M.E.; Piper, R.C. Disrupting the Transmembrane Domain Interface between PMP22 and MPZ Causes Peripheral Neuropathy. iScience 2024, 27, 110989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.M.; Small, K.M.; Nag, S.; Mokha, S.S. Activation of Membrane Estrogen Receptors Attenuates NOP-Mediated Tactile Antihypersensitivity in a Rodent Model of Neuropathic Pain. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambarotta, G.; Fregnan, F.; Gnavi, S.; Perroteau, I. Neuregulin 1 Role in Schwann Cell Regulation and Potential Applications to Promote Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2013, 108, 223–256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. The Role of the Neuregulin 1-ErbB4 Signaling Pathway in Neurological Disorders. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2024, 75, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasylyev, D.V.; Zhao, P.; Schulman, B.R.; Waxman, S.G. Interplay of Nav1. 8 and Nav1. 7 channels drives neuronal hyperexcitability in neuropathic pain. J. Gen. Physiol. 2024, 156, e202413596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Bonalume, V.; Gao, Q.; Chen, J.T.; Rohr, K.; Hu, J.; Carr, R. Pre-Synaptic GABAA in NaV1.8+ Primary Afferents Is Required for the Development of Punctate but Not Dynamic Mechanical Allodynia following CFA Inflammation. Cells 2022, 11, 2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnaghi, V.; Ballabio, M.; Consoli, A.; Lambert, J.J.; Roglio, I.; Melcangi, R.C. GABA receptor-mediated effects in the peripheral nervous system: A cross-interaction with neuroactive steroids. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2006, 28, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnaghi, V.; Parducz, A.; Frasca, A.; Ballabio, M.; Procacci, P.; Racagni, G.; Bonanno, G.; Fumagalli, F. GABA synthesis in Schwann cells is induced by the neuroactive steroid allopregnanolone. J. Neurochem. 2010, 112, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, N.; Sajedi, F.; Mohammadi, Y.; Mirjalili, M.; Mehrpooya, M. Ameliorative effects of N-acetylcysteine as adjunct therapy on symptoms of painful diabetic neuropathy. J. Pain Res. 2019, 12, 3147–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamdi, A.A.; Mackie, S.; Trueman, R.P.; Rayner, M.L. Pharmacologically targeting Schwann cells to improve regeneration following nerve damage. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1603752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Nakagawa, T.; Minami, M.; Satoh, M. Analgesic Effects of Intrathecal Administration of P2Y Nucleotide Receptor Agonists UTP and UDP in Normal and Neuropathic Pain Model Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 303, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazıroğlu, M.; Ciğ, B.; Ozgül, C. Neuroprotection induced by N-acetylcysteine against cytosolic glutathione depletion-induced Ca2+ influx in dorsal root ganglion neurons of mice: Role of TRPV1 channels. Neuroscience 2013, 242, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, A.; Kolberg, C.; Moraes, M.S.; Riffel, A.P.; Finamor, I.A.; Belló-Klein, A.; Pavanato, M.A.; Partata, W.A. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on the spinal-cord glutathione system and nitric-oxide metabolites in rats with neuropathic pain. Neurosci. Lett. 2014, 569, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SUPERALA CARNITINE® (SC) | SUPERALA CARNITINE® Forte (SCF) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Dosage | In Vitro | Sample | Dosage | In Vitro |

| N-Acetyl L-Carnitine (N-ALC) of which: | 1204 mg | 602 µg/mL | N-Acetyl L-Carnitine (N-ALC) of which: | 1204 mg | 602 µg/mL |

| L-Acetyl-Carnitine | 1000 mg | 500 µg/mL | L-Acetyl-Carnitine | 1000 mg | 500 µg/mL |

| Citicoline sodium (oral grade; granular) of which: | 284 mg | 142 µg/mL | Citicoline sodium (oral grade; granular) of which: | 284 mg | 142 µg/mL |

| Citicoline | 250 mg | 125 µg/mL | Citicoline | 250 mg | 125 µg/mL |

| Vitamin B6 HCL of which: | 3.44 mg | 1.72 µg/mL | 5′-UMP disodium SALT-Freeman of which: | 77 mg | 38.50 µg/mL |

| Vitamin B6 | 2.80 mg | 1.40 µg/mL | UMP | 50 mg | 25 µg/mL |

| ALA 30-60 Mesh | 800 mg | 400 µg/mL | NAC USP | 600 mg | 300 µg/mL |

| GSH | 200 mg | 100 µg/mL | |||

| Total (Bioactive ingredients) | 2052.80 mg | Total (Bioactive ingredients) | 2100 mg | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mulè, S.; Parini, F.; Galla, R.; Uberti, F. Neuroinflammation-Modulating Properties Combining Glutathione, N-Acetylcysteine, and Uridine Monophosphate in a Formulation Supplement: An In Vitro Study. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121340

Mulè S, Parini F, Galla R, Uberti F. Neuroinflammation-Modulating Properties Combining Glutathione, N-Acetylcysteine, and Uridine Monophosphate in a Formulation Supplement: An In Vitro Study. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121340

Chicago/Turabian StyleMulè, Simone, Francesca Parini, Rebecca Galla, and Francesca Uberti. 2025. "Neuroinflammation-Modulating Properties Combining Glutathione, N-Acetylcysteine, and Uridine Monophosphate in a Formulation Supplement: An In Vitro Study" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121340

APA StyleMulè, S., Parini, F., Galla, R., & Uberti, F. (2025). Neuroinflammation-Modulating Properties Combining Glutathione, N-Acetylcysteine, and Uridine Monophosphate in a Formulation Supplement: An In Vitro Study. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121340