Sex-Specific Impact of Metabolic Syndrome on Brain Structures Vulnerable to Alzheimer’s Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Brazilian Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Measures

2.3. Definition of MetS

2.4. MRI Acquisition

2.5. Volumetric Analyses

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Volumetric Analysis of ROIs by Metabolic Syndrome Status and Age Subgroups

3.2. Participants Below the 50th Age Percentile (Q2)

3.3. Participants Above the 50th Age Percentile (Q2)

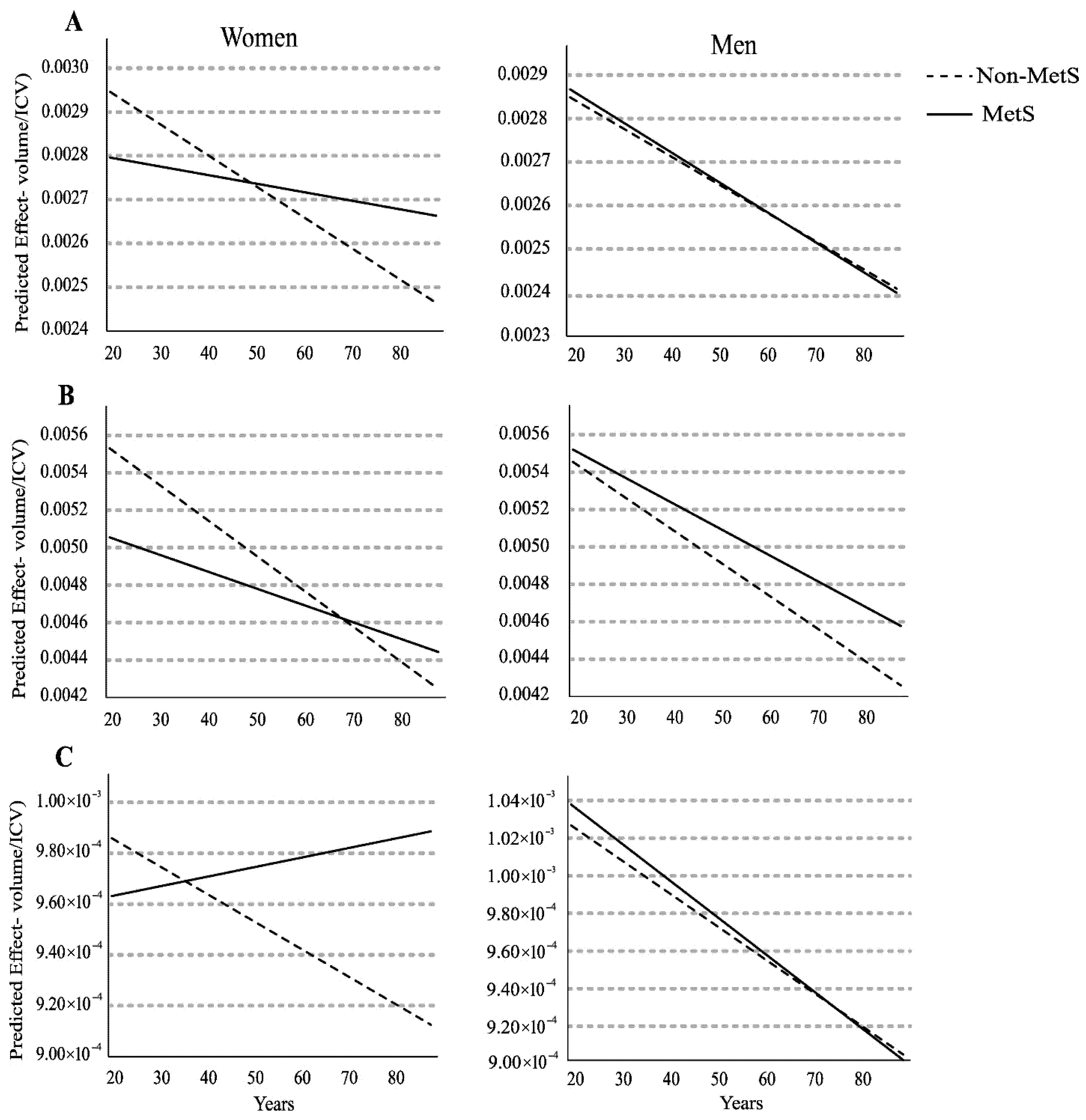

3.4. Quantile Regression (q = 0.5) of Relative ROI Volume and Age (Years)

3.5. Relative Left Hippocampus Volume

3.6. Relative Left Middle Temporal Gyrus Volume

3.7. Relative Right Amygdala Volume

3.8. Post Hoc Exploratory Analysis: Age Effects in Non-MetS Women in the Left Hippocampus and Middle Temporal Gyrus

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oliveira, L.V.A.; Dos Santos, B.N.S.; Machado, Í.E.; Malta, D.C.; Velasquez-Melendez, G.; Felisbino-Mendes, M.S. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and its components in the Brazilian adult population. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2020, 25, 4269–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Castañeda, H.; Pineda-García, G.; Serrano-Medina, A.; Martínez, A.L.; Bonilla, J.; Ochoa-Ruíz, E. Neuropsychology of metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogent Psychol. 2021, 8, 1913878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordestani-Moghadam, P.; Assari, S.; Nouriyengejeh, S.; Mohammadipour, F.; Pourabbasi, A. Cognitive impairments and associated structural brain changes in metabolic syndrome and implications of neurocognitive intervention. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2021, 29, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, J.A.; Bena, J.; Bekris, L.; Kodur, N.; Kasumov, T.; Leverenz, J.B.; Kashyap, S.R. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Metabolic syndrome biomarkers relate to rate of cognitive decline in MCI and dementia stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2023, 15, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Knopman, D.S.; Jagust, W.J.; Petersen, R.C.; Weiner, M.W.; Aisen, P.S.; Shaw, L.M.; Vemuri, P.; Wiste, H.J.; Weigand, S.D.; et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: An updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuff, N.; Zhu, X.P. Imaging of mild cognitive impairment and early dementia. Br. J. Radiol. 2007, 80, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell-McGinty, S.; Lopez, O.L.; Meltzer, C.C.; Scanlon, J.M.; Whyte, E.M.; DeKosky, S.T.; Becker, J.T. Differential cortical atrophy in subgroups of mild cognitive impairment. Arch. Neurol. 2005, 62, 1393–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, S.A.; DeKosky, S.T.; Scheff, S.W. Volumetrie atrophy of the amygdala in Alzheimer’s disease: Quantitative serial reconstruction. Neurology 1991, 41, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alex DLeow Yanovsky, I.; Parikshak, N.; Hua, X.; Lee, S.; Toga, A.W. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: A one-year follow up study using tensor-based morphometry correlating degenerative rates, biomarkers and cognition. Neuroimage 2009, 45, 645–655. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.L.; Van Hoesen, G.W.; Cassell, M.D.; Poremba, A. Parcellation of human temporal polar cortex: A combined analysis of multiple cytoarchitectonic, chemoarchitectonic, and pathological markers. J. Comp. Neurol. 2009, 514, 595–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, O.; McLaren, D.G.; Tommet, D.; Mungas, D.; Jones, R.N. Coevolution of brain structures in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage 2013, 66, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017, 13, 325–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosconi, L.; Rahman, A.; Diaz, I.; Wu, X.; Scheyer, O.; Hristov, H.W.; Vallabhajosula, S.; Isaacson, R.S.; De Leon, M.J.; Brinton, R.D. Increased Alzheimer’s risk during the menopause transition: A 3-year longitudinal brain imaging study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Schelbaum, E.; Hoffman, K.; Diaz, I.; Hristov, H.; Andrews, R.; Jett, S.; Jackson, H.; Lee, A.; Sarva, H.; et al. Sex-driven modifiers of Alzheimer risk: A multimodality brain imaging study. Neurology 2020, 95, E166–E178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, M.M.; Aggarwal, N.T.; Vila-Castelar, C.; Agarwal, P.; Arenaza-Urquijo, E.M.; Brett, B.; Brugulat-Serrat, A.; DuBose, L.E.; Eikelboom, W.S.; Flatt, J.; et al. Consideration of sex and gender in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders from a global perspective. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 18, 2707–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, S. Women twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease as men—But scientists do not know why. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 704–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, C.M.; Pereira, A.C.; de Andrade, M.; Soler, J.M.; Krieger, J.E. Heritability of cardiovascular risk factors in a Brazilian population: Baependi Heart Study. BMC Med. Genet. 2008, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, K.J.; von Schantz, M.; Negrão, A.B.; Santos, H.C.; Horimoto, A.R.V.R.; Duarte, N.E.; Gonçalves, G.C.; Soler, J.M.P.; de Andrade, M.; Lorenzi-Filho, G.; et al. Cohort profile: The Baependi Heart Study—A family-based, highly admixed cohort study in a rural Brazilian town. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.; Leocadio-Miguel, M.; Taporoski, T.; Gomez, L.; Horimoto, A.; Alkan, E.; Beijamini, F.; Pedrazzoli, M.; Knutson, K.; Krieger, J.; et al. Evening preference correlates with regional brain volumes in the anterior occipital lobe. Chronobiol. Int. 2021, 38, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkan, E.; Taporoski, T.P.; Sterr, A.; von Schantz, M.; Vallada, H.; Krieger, J.E.; Pereira, A.C.; Alvim, R.; Horimoto, A.R.V.R.; Pompéia, S.; et al. Metabolic syndrome alters relationships between cardiometabolic variables, cognition and white matter hyperintensity load. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, K.G.; Eckel, R.H.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Cleeman, J.I.; Donato, K.A.; Fruchart, J.C.; James, W.P.T.; Loria, C.M.; Smith, S.C., Jr. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the international diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; National heart, lung, and blood institute; American heart association; World heart federation; International. Circulation 2009, 120, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destrieux, C.; Fischl, B.; Dale, A.; Halgren, E. Automatic parcellation of human cortical gyri and sulci using standard anatomical nomenclature. Neuroimage 2010, 53, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigamonti, A.E.; Cicolini, S.; Tamini, S.; Caroli, D.; Cella, S.G.; Sartorio, A. The Age-Dependent Increase of Metabolic Syndrome Requires More Extensive and Aggressive Non-Pharmacological and Pharmacological Interventions: A Cross-Sectional Study in an Italian Cohort of Obese Women. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 2021, 5576286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, C.-Y.; Piao, M.; Kim, M.; Im, Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Choi, J.; Cho, K.H. Biological age and lifestyle in the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome: The NHIS health screening data, 2014–2015. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, E.S.; Giles, W.H.; Mokdad, A.H. Increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults. JAMA-J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2002, 287, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.S.; Park, Y.M.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, Y.H.; Ko, S.H.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, S.R.; Kang, S.Y.; Lee, W.C.; et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of the metabolic syndrome in middle-aged Korean adults. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2005, 20, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pompei, L.M.; Bonassi-Machado, R.; Steiner, M.L.; Pompei, I.M.; de Melo, N.R.; Nappi, R.E.; Fernandes, C.E. Profile of Brazilian climacteric women: Results from the Brazilian Menopause Study. Climacteric 2022, 25, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettio, L.E.B.; Rajendran, L.; Gil-Mohapel, J. The effects of aging in the hippocampus and cognitive decline. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 79, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuff, N.; Amend, D.L.; Knowlton, R.; Norman, D.; Fein, G.; Weiner, M.W. Age-related metabolite changes and volume loss in the hippocampus by magnetic resonance spectroscopy and imaging. Neurobiol. Aging 1999, 20, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R.; Petersen, R.C.; Xu, Y.C.; Waring, S.C.; O’BRien, P.C.; Tangalos, E.G.; Smith, G.E.; Ivnik, R.J.; Kokmen, E. Medial temporal atrophy on MRI in normal aging and very mild Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1997, 49, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convit, A.; De Asis, J.; De Leon, M.J.; Tarshish, C.Y.; De Santi, S.; Rusinek, H. Atrophy of the medial occipitotemporal, inferior, and middle temporal gyri in non-demented elderly predict decline to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2000, 21, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruessner, J.C.; Collins, D.L.; Pruessner, M.; Evans, A.C. Age and gender predict volume decline in the anterior and posterior hippocampus in early adulthood. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, L.L.; Wilson, R.S.; Bienias, J.L.; Schneider, J.A.; Evans, D.A.; Bennett, D.A. Sex differences in the clinical manifestations of Alzheimer disease pathology. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, N.Z.; Yahaya, M.F.; Mohd Fahami, N.A.; Abdul Manan, H.; Singh, M.; Damanhuri, H.A. Brain volumetric changes in menopausal women and its association with cognitive function: A structured review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1158001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, M.; Abe, O.; Miyati, T.; Inano, S.; Hayashi, N.; Aoki, S.; Mori, H.; Kabasawa, H.; Ino, K.; Yano, K.; et al. 3 tesla MRI detects accelerated hippocampal volume reduction in postmenopausal women. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2011, 33, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosconi, L.; Berti, V.; Dyke, J.; Schelbaum, E.; Jett, S.; Loughlin, L.; Jang, G.; Rahman, A.; Hristov, H.; Pahlajani, S.; et al. Menopause impacts human brain structure, connectivity, energy metabolism, and amyloid-beta deposition. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanapat, P.; Hastings, N.B.; Gould, E. Ovarian steroids influence cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus of the adult female rat in a dose- and time-dependent manner. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005, 481, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zia, G.; Shahid, S.S.; Yang, H.C.; Gao, S.; Risacher, S.L.; Saykin, A.J.; Wu, Y.C. Longitudinal non-linear changes in the microstructure of the hippocampal subfields in older adults. Neurobiol. Aging 2025, 155, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenaza-Urquijo, E.M.; Boyle, R.; Casaletto, K.; Anstey, K.J.; Vila-Castelar, C.; Colverson, A.; Palpatzis, E.; Eissman, J.M.; Ng, T.K.S.; Raghavan, S.; et al. Sex and gender differences in cognitive resilience to aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 5695–5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, N.C.; Warrington, E.K.; Freeborough, P.A.; Hartikainen, P.; Kennedy, A.M.; Stevens, J.M.; Rossor, M.N. Presymptomatic hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease A longitudinal MRI study. Brain 1996, 119, 2001–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasuski, J.S.; Alexander, G.E.; Horwitz, B.; Daly, E.M.; Murphy, D.G.; Rapoport, S.I.; Schapiro, M.B. Volumes of medial temporal lobe structures in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment (and in healthy controls). Biol. Psychiatry 1998, 43, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.; Pascual-leone, A.; Hsu, Y.-H. Late-onset Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia in Type 2 Diabetes: 20-year Longitudinal matched cohort study. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, e090794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruthirakuhan, M.; Swardfager, W.; Xiong, L.; MacIntosh, B.J.; Rabin, J.S.; Lanctôt, K.L.; Ottoy, J.; Ramirez, J.; Keith, J.; Black, S.E. Investigating the impact of hypertension with and without diabetes on Alzheimer’s disease risk: A clinico-pathological study. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 2766–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opel, N.; Thalamuthu, A.; Milaneschi, Y.; Grotegerd, D.; Flint, C.; Leenings, R.; Goltermann, J.; Richter, M.; Hahn, T.; Woditsch, G.; et al. Brain structural abnormalities in obesity: Relation to age, genetic risk, and common psychiatric disorders: Evidence through univariate and multivariate mega-analysis including 6420 participants from the ENIGMA MDD working group. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 4839–4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Ge, T.T.; Yin, G.; Cui, R.; Zhao, G.; Yang, W. Stress-induced functional alterations in amygdala: Implications for neuropsychiatric diseases. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyken, P.; Lacoste, B. Impact of Metabolic Syndrome on Neuroinflammation and the Blood–Brain Barrier. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, I.A.; Jansen, P.R.; Lamb, H.J. Obesity, Brain Volume, and White Matter Microstructure at MRI: A Cross-sectional UK Biobank Study. Radiology 2019, 292, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-MetS (n = 115) | MetS (n = 82) | Non-MetS (n = 151) | MetS (n = 152) | |

| Age (yr.) | 47 (35–59) | 57 (47–66) # | 40 (32–51) | 57 (48–62) # |

| Education (yr.) | 8 (4–11) | 8 (4–11) | 11 (4–12) | 6 (4–11) # |

| SBP (mmHg) | 118 (113–127) | 130 (121–139) # | 109 (102–118) | 119 (110–133) *,# |

| DBP (mmHg) | 71 (64–76) | 76 (69–83) *,# | 67 (62–72) | 73 (65–80) *,# |

| Waist circ. (cm) | 88 (83–93) | 98 (93–106) *,# | 88 (80–95) | 94 (89–102) *,# |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 85 (79–91) | 90 (76–101) *,# | 83 (76–90 ) | 92 (83–101) *,# |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.2 (5.0–5.4) | 5.4 (5.2–5.8) *,# | 5.1 (4.8–5.4) | 5.5 (5.2–5.9) *,# |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 43 (36–50) | 38 (34–42) *,# | 54 (47–63) | 43 (38–48) *,# |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 117 (90–145) | 189 (139–251) *,# | 109 (81–135) | 169 (130–234) *,# |

| ICV (mm3) | 1,525,826 (1,455,052–1,650,918) | 1,535,378 (1,454,606–1,634,882) | 1,399,916 (1,315,294–1,491,247) | 1,390,358 (1,316,217–1,466,832) |

| Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-MetS (n = 63) | MetS (n = 27) | Non-MetS (n = 113) | MetS (n = 47) | ||

| Age (yr.) | 36 (29–42) | 38 (33–47) | 36 (30–43) | 41 (32–47) *** | |

| Education (yr.) | 11 (6–12) | 9.5 (7.0–11.0) | 11 (6–13) | 11 (7–13) | |

| ROI | |||||

| Hippocampus | 0.27 (0.26–0.30) | 0.27 (0.26–0.28) | 0.27 (0.27–0.30) | 0.27 (0.36–0.29) | |

| Entorhinal | 0.24 (0.20–0.27) | 0.24 (0.21–0.27) | 0.24 (0.22–0.26) | 0.24 (0.22–0.27) | |

| Right | Middle temporal gyrus | 0.56 (0.53–0.60) | 0.57 (0.51–0.60) | 0.58 (0.52–0.59) | 0.55 (0.50–0.59) |

| Precuneus | 0.35 (0.32–0.37) | 0.36 (0.34–0.38) | 0.34 (0.31–0.36) | 0.34 (0.32–0.36) | |

| Amygdala | 0.102 (0.092–0.108) | 0.100 (0.092–0.103) | 0.100 (0.086–0.100) | 0.100 (0.090–0.106) | |

| Hippocampus | 0.27 (0.25–0.28) | 0.27 (0.25–0.28) | 0.28 (0.27–0.30) | 0.27 (0.26–0.28) ** | |

| Entorhinal | 0.21 (0.19–0.24) | 0.22 (0.18–0.23) | 0.22 (0.19–0.25) | 0.22 (0.19–0.26) | |

| Left | Middle temporal gyrus | 0.52 (0.49–0.56) | 0.51 (0.48–0.57) | 0.51 (0.48–0.57) | 0.48 (0.43–0.53) * |

| Precuneus | 0.35 (0.31–0.38) | 0.36 (0.33–0.38 | 0.34 (0.31–0.38) | 0.34 (0.32–0.39) | |

| Amygdala | 0.094 (0.089–0.100) | 0.095 (0.088–0.100) | 0.091 (0.085–0.100) | 0.092 (0.087–0.101) | |

| Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-MetS (n = 52) | MetS (n = 55) | Non-MetS (n = 38) | MetS (n = 105) | ||

| Age (yr.) | 61 (55–68) | 62 (56–69) | 58 (55–65) | 60 (56–65) | |

| Education (yr.) | 4 (4–10) | 8 (4–11) # | 5 (4–11) | 4 (4–8) | |

| ROI | |||||

| Hippocampus | 0.26 (0.24–0.28) | 0.27 (0.24–0.28) | 0.27 (0.25–0.29) | 0.28 (0.26–0.29) | |

| Entorhinal | 0.25 (0.23–0.28) | 0.24 (0.21–0.27) | 0.25 (0.22–0.26) | 0.24 (0.22–0.28) | |

| Right | Middle temporal gyrus | 0.52 (0.48–0.56) | 0.53 (0.49–0.55) | 0.53 (0.47–0.56) | 0.52 (0.48–0.56) |

| Precuneus | 0.33 (0.31–0.35) | 0.35 (0.30–0.37) | 0.33 (0.29–0.36) | 0.35 (0.32–0.37) | |

| Amygdala | 0.095 (0.086–0.106) | 0.095 (0.087–0.105) | 0.090 (0.083–0.101) | 0.098 (0.089–0.105) * | |

| Hippocampus | 0.26 (0.24–0.28) | 0.26 (0.23–0.28) | 0.26 (0.25–0.29) | 0.27 (0.25–0.29) | |

| Entorhinal | 0.22 (0.19–0.25) | 0.22 (0.18–0.25) | 0.22 (0.20–0.24) | 0.22 (0.20–0.25) | |

| Left | Middle temporal gyrus | 0.47 (0.42–0.52) | 0.49 (0.46–0.53) | 0.47 (0.44–0.52) | 0.47 (0.43–0.52) |

| Precuneus | 0.32 (0.29–0.35) | 0.33 (0.30–0.37) | 0.33 (0.30–0.36) | 0.34 (0.30–0.37) | |

| Amygdala | 0.090 (0.082–0.098) | 0.089 (0.084–0.099) | 0.092 (0.084–0.099) | 0.092 (0.084–0.098) | |

| Dependent Variable (ROI/ICV) | Subgroup (Age) | Coefficient (βMetS) | Standard Error | p-Value | Interpreted Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left Hippocampus | Younger Women (≤Q2) | 0.0001 | 4.41 × 10−5 | 0.02 | Non-MetS > MetS (Reduced Volume in MetS) |

| Left Middle Temporal Gyrus | Younger Women (≤Q2) | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.05 | Non-MetS > MetS (Reduced Volume in MetS, Trend) |

| Right Amygdala | Older Women (>Q2) | −9.41 × 10−5 | 2.78 × 10−5 | <0.001 | MetS > Non-MetS (Increased Volume in MetS) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hohl, R.; de Morais, F.G.F.; Taporoski, T.P.; Negrão, A.B.; Evans, S.L.; de Oliveira, C.M.; Pereira, A.d.C.; Alvim, R.d.O. Sex-Specific Impact of Metabolic Syndrome on Brain Structures Vulnerable to Alzheimer’s Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Brazilian Cohort. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1341. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121341

Hohl R, de Morais FGF, Taporoski TP, Negrão AB, Evans SL, de Oliveira CM, Pereira AdC, Alvim RdO. Sex-Specific Impact of Metabolic Syndrome on Brain Structures Vulnerable to Alzheimer’s Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Brazilian Cohort. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1341. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121341

Chicago/Turabian StyleHohl, Rodrigo, Fernanda Gabriele Fernandes de Morais, Tâmara Pessanha Taporoski, André Brooking Negrão, Simon L. Evans, Camila Maciel de Oliveira, Alexandre da Costa Pereira, and Rafael de Oliveira Alvim. 2025. "Sex-Specific Impact of Metabolic Syndrome on Brain Structures Vulnerable to Alzheimer’s Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Brazilian Cohort" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1341. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121341

APA StyleHohl, R., de Morais, F. G. F., Taporoski, T. P., Negrão, A. B., Evans, S. L., de Oliveira, C. M., Pereira, A. d. C., & Alvim, R. d. O. (2025). Sex-Specific Impact of Metabolic Syndrome on Brain Structures Vulnerable to Alzheimer’s Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Brazilian Cohort. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1341. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121341