Augmented and Mixed Reality Interventions in People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Objective

3. Methods

3.1. Design

3.2. Literature Search in Databases

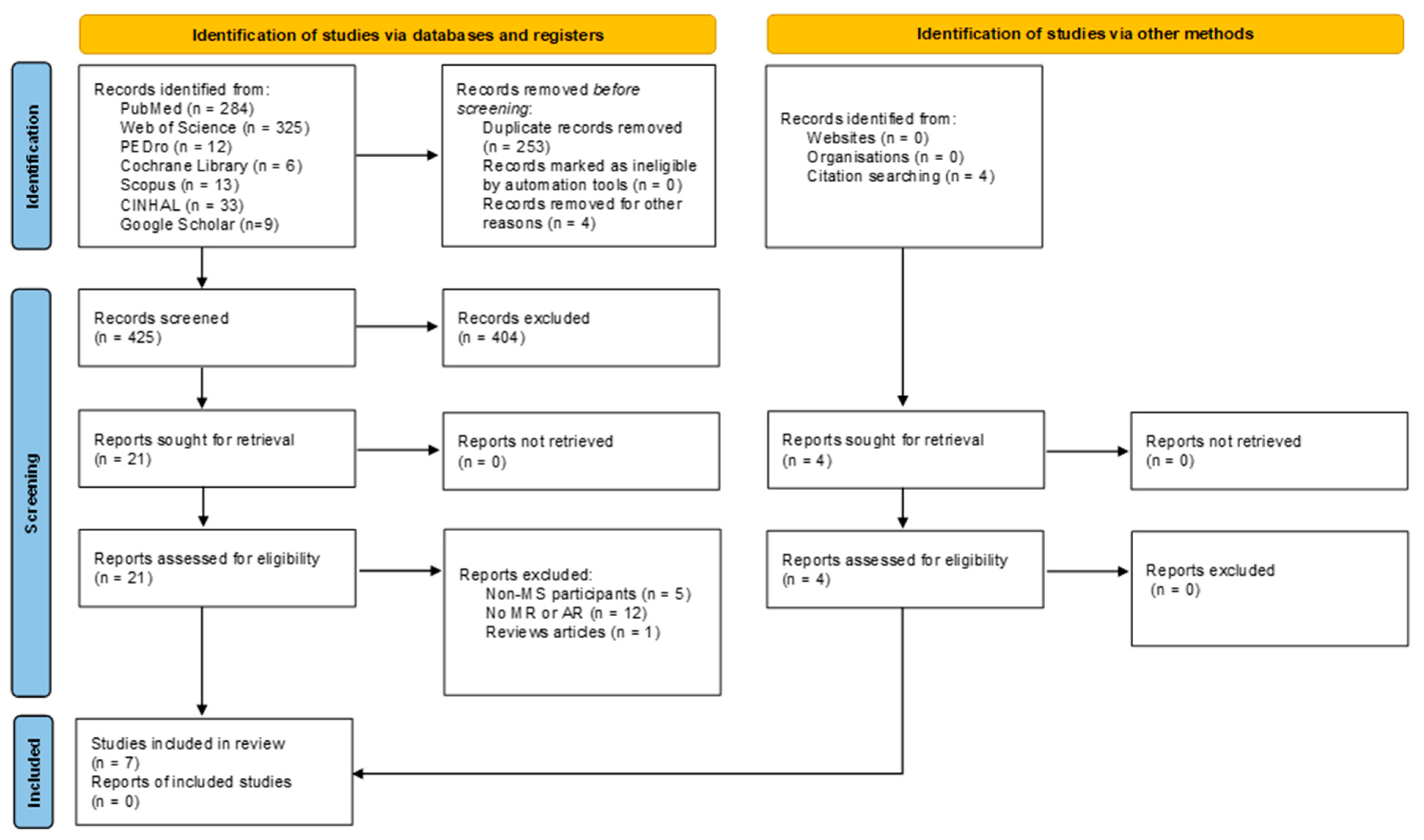

3.3. Study Selection

3.4. Data Collection

3.5. Methodological Quality of Selected Studies and Risk of Bias

- (a)

- Randomized controlled trials—RoB 2 [18]

- (b)

- Non-randomized intervention studies—ROBINS-I V2

- (c)

- Diagnostic accuracy studies—QUADAS-2

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Technologies Included and Intervention Characteristics

4.3. Outcomes Measures

4.4. Main Findings

4.5. Assessment of Methodological Quality of the Studies and Risk of Bias

5. Discussion

5.1. Mixed Reality and Augmented Reality in Multiple Sclerosis

5.2. Methodological Quality

5.3. Augmented Reality in Other Neurological Diseases and Contexts

5.4. Mixed Reality in Other Neurological Diseases and Contexts

5.5. Clinical Implications

5.6. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cortes-Perez, I.; Osuna-Perez, M.C.; Montoro-Cardenas, D.; Lomas-Vega, R.; Obrero-Gaitan, E.; Nieto-Escamez, F.A. Virtual reality-based therapy improves balance and reduces fear of falling in patients with multiple sclerosis. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2023, 20, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satava, R.M. Emerging technologies for surgery in the 21st century. Arch. Surg. 1999, 134, 1197–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basalic, E.B.; Roman, N.; Tuchel, V.I.; Miclăuș, R.S. Virtual reality applications for balance rehabilitation and efficacy in addressing other symptoms in multiple sclerosis—A review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keersmaecker, E.; Guida, S.; Denissen, S.; Dewolf, L.; Nagels, G.; Jansen, B.; Beckwée, D.; Swinnen, E. Virtual reality for multiple sclerosis rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 1, CD013834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amini Gougeh, R.; Falk, T.H. Head-Mounted Display-Based Virtual Reality and Physiological Computing for Stroke Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. Front. Virtual Real. 2022, 3, 889271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Erena, P.; Fernandez-Guinea, S.; Kourtesis, P. Cognitive Assessment and Training in Extended Reality: Multimodal Systems, Clinical Utility, and Current Challenges. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta-Gómez, A.; Martín-Díaz, P.; Sánchez-Herrera Baeza, P.; Martínez-Medina, A.; Ortiz-Comino, C.; Cano-de-la-Cuerda, R. Nintendo switch Joy-Cons’ infrared motion camera sensor for training manual dexterity in people with multiple sclerosis: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta-Gomez, A.; Sanchez-Herrera-Baeza, P.; Ona-Simbana, E.D.; Martinez-Medina, A.; Ortiz-Comino, C.; Balaguer-Bernaldo-de-Quiros, C.; Jardón-Huete, A.; Cano-De-La-Cuerda, R. Effects of virtual reality associated with serious games for upper limb rehabilitation inpatients with multiple sclerosis: Randomized controlled trial. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2020, 17, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcos-Antón, S.; JardÓNHuete, A.; Oña, E.D.; Blázquez-Fernández, A.; Martínez-Rolando, L.; Cano de la Cuerda, R. sEMG-controlled forearm bracelet and serious game-based rehabilitation for training manual dexterity in people with multiple sclerosis: A randomised controlled trial. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2023, 20, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Verdu, M.; Ferreira-Sanchez, M.R.; Cano-de-la-Cuerda, R.; Jimenez-Antona, C. Efficacy of virtual reality on balance and gait in multiple sclerosis. Syst. Rev. Randomized Control. trials. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 68, 357–368. [Google Scholar]

- Waliño-Paniagua, C.; Gómez-Calero, C.; Jiménez-Trujillo, M.; Aguirre-Tejedor, L.; Bermejo-Franco, A.; Ortiz-Gutiérrez, R.M.; Cano-De-La-Cuerda, R. Effects of a Game-Based Virtual Reality Video Capture Training Program Plus Occupational Therapy on Manual Dexterity in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Healthc. Eng. 2019, 2019, 9780587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebenitsch, L.; Owen, C. Review on cybersickness in applications and visual displays. Virtual Real. 2016, 20, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.; Nesbitt, K.; Nalivaiko, E. A systematic review of cybersickness. In Proceedings of the 2014 Australasian Conference on Interactive Entertainment (IE2014), Newcastle, NSW, Australia, 2–3 December 2014; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2–3 December; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, G. Full-immersion virtual reality: Adverse effects related to static balance. Neurosci. Lett. 2020, 733, 134974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, S.H.; Black, N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1998, 52, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Levels of Evidence. 2009. Available online: http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-of-evidence/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Higgins, J.P.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Sterne, J.A. Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 205–228. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 6.3; Cochrane: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.G.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Bossuyt, P.M.M.; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baram, Y.; Miller, A. Virtual reality cues for improvement of gait in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2006, 66, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baram, Y.; Miller, A. Glide-symmetric locomotion reinforcement in patients with multiple sclerosis by visual feedback. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2010, 5, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, M.E.; Holtzer, R.; Izzetoglu, M.; Motl, R.W. The Use of Augmented Reality on a Self-Paced Treadmill to Quantify Attention and Footfall Placement Variability in Middle-Aged to Older-Aged Adults with Multiple Sclerosis. Sclerosis 2025, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruszyńska, M.; Milewska-Jędrzejczak, M.; Bednarski, I.; Szpakowski, P.; Głąbiński, A.; Tadeja, S.K. Towards effective telerehabilitation: Assessing effects of applying augmented reality in remote rehabilitation of patients suffering from multiple sclerosis. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. (TACCESS) 2022, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatino, E.; Moschetta, M.; Lucaroni, A.; Barresi, G.; Ferraresi, C.; Podda, J.; Grange, E.; Brichetto, G.; Bucchieri, A. A Pilot Study on Mixed-Reality Approaches for Detecting Upper-Limb Dysfunction in Multiple Sclerosis: Insights on Cerebellar Tremor. Virtual Worlds 2025, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, C.; Kern, F.; Gall, D.; Latoschik, M.E.; Pauli, P.; Käthner, I. Immersive virtual reality during gait rehabilitation increases walking speed and motivation: A usability evaluation with healthy participants and patients with multiple sclerosis and stroke. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2021, 18, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucchieri, A.; Lucaroni, A.; Moschetta, M.; Ricci, L.; Sabatino, E.; Grange, E.; Tacchino, A.; Podda, J.; De Momi, E.; Ferraresi, C.; et al. Exploring the Potential of Mixed Reality for Functional Assessment in Multiple Sclerosis. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Gaming, Entertainment, and Media Conference (GEM), Turin, Italy, 5–7 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. How to Use the ICF: A Practical Manual for Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Calafiore, D.; Invernizzi, M.; Ammendolia, A.; Marotta, N.; Fortunato, F.; Paolucci, T.; Ferraro, F.; Curci, C.; Cwirlej-Sozanska, A.; de Sire, A. Efficacy of virtual reality and exergaming in improving balance in patients with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 773459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.S.; Fagundes, C.V.; dos Santos Mendes, F.A.; Leal, J.C. Effectiveness of virtual reality rehabilitation in persons with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2021, 54, 103128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casuso-Holgado, M.J.; Martín-Valero, R.; Carazo, A.F.; Medrano-Sánchez, E.M.; Cortés-Vega, M.D.; Montero-Bancalero, F.J. Effectiveness of virtual reality training for balance and gait rehabilitation in people with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2018, 32, 1220–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alayidi, B.; Al-Yahya, E.; McNally, D.; Morgan, S.P. Exploring balance control mechanisms in people with multiple sclerosis in virtual reality environment: A systematic review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2025, 22, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghian, A.; Abo-Zahhad, M.; Sayed, M.S.; Abd El-Malek, A.H. Virtual and augmented reality in biomedical engineering. Biomed. Eng. Online 2023, 22, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khokale, R.; Mathew, G.S.; Ahmed, S.; Maheen, S.; Fawad, M.; Bandaru, P.; Zerin, A.; Nazir, Z.; Khawaja, I.; Sharif, I.; et al. Virtual and Augmented Reality in Post-stroke Rehabilitation: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e37559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Gao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liao, Z.; Song, C.; Mao, Y. Effects of gait adaptation training on augmented reality treadmill for patients with stroke in community ambulation. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2024, 36, mzae008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Liu, X.; Ning, L.; Ge, L. The Effects of Augmented Reality on Rehabilitation of Stroke Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2025, 34, 4578–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figeys, M.; Koubasi, F.; Hwang, D.; Hunder, A.; Miguel-Cruz, A.; Rios Rincon, A. Challenges and promises of mixed-reality interventions in acquired brain injury rehabilitation: A scoping review. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2023, 179, 105235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, M.; Lehrer, N.; Duff, M.; Venkataraman, V.; Turaga, P.; Ingalls, T.; Rymer, W.Z.; Wolf, S.L.; Rikakis, T. Interdisciplinary concepts for design and implementation of mixed reality interactive neurorehabilitation systems for stroke. Phys. Ther. 2015, 95, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomer, C.; Llorens, R.; Noe, E.; Alcaniz, M. Effect of a mixed reality-based intervention on arm, hand, and finger function on chronic stroke. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2016, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheermesser, M.; Baumgartner, D.; Nast, I.; Bansi, J.; Kool, J.; Bischof, P.; Bauer, C.M. Therapists and patients perceptions of a mixed reality system designed to improve trunk control and upper extremity function. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzo, M.; Pica, A.; Pascucci, S.; Serrao, M.; Marinozzi, F.; Bini, F. A Proof of Concept Combined Using Mixed Reality for Personalized Neurorehabilitation of Cerebellar Ataxic Patients. Sensors 2023, 23, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzo, M.; Marinozzi, F.; Finti, A.; Lattao, M.; Trabassi, D.; Castiglia, S.F.; Serrao, M.; Bini, F. Mixed Reality-Based Smart Occupational Therapy Personalized Protocol for Cerebellar Ataxic Patients. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammann-Reiffer, C.; Keller, U.; Klay, A.; Meier, L.; van Hedel, H.J.A. Do Youths with Neuromotor Disorder and Their Therapists Prefer a Mixed or Virtual Reality Head-Mounted Display? J. Rehabil. Med. Clin. Commun. 2021, 4, 1000072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Data Base | Search Fields | Search Strategy | Filters |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | MeSH terms + free-text keywords | multiple sclerosis (MeSH) AND rehabilitation (MeSH) AND mixed reality OR augmented reality | Clinical trial, controlled clinical trial, clinical study |

| Web of Science | Topic | multiple sclerosis AND rehabilitation AND (mixed reality OR augmented reality) | Clinical trial |

| PEDRo | Free-text keywords | multiple sclerosis, rehabilitation, reality | No filters |

| Cochrane Library | MeSH terms + free-text keywords | multiple sclerosis AND rehabilitation AND (mixed reality OR augmented reality) | No filters |

| Scopus | Title, abstract and keywords | multiple sclerosis AND rehabilitation AND (mixed reality OR augmented reality) | No filters |

| CINHAL | Free-text keywords | multiple sclerosis AND (mixed reality OR augmented reality) | No filters |

| Google Scholar | Advanced search fields | With all of the words: multiple sclerosis; With the exact phrase: mixed reality, augmented reality; Where my words occur: anywhere in the article | No filters |

| Author/ Year/ Country | Participants (Sample Size/Age, Sex/Disease Duration/EDSS) | Technology Employed | Intervention or Protocol | Dose | Outcome Measures | Results | Downs & Black Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baram & Miller, 2006 [23]/Israel | n = 28 Group 1: n = 16 MS/40.3 (± 13.5)/56.2% women/8.6 (± 8.1) months/4.4 (± 1.3) Group 2: n = 12 healthy control/25.4 (±1.9)/50% women | A closed-loop head-mounted display (HMD) system projecting either a checkerboard floor or transverse lines onto a self-paced treadmill. | Each participant completed 4 walking stages of 10 m at a self-selected comfortable speed.

| 1 session |

| MS with low baseline speed (<0.7 m/s):

No meaningful improvement. | 10/27 |

| Baram & Miller, 2010 [24]/Israel | n = 21 Group 1: n = 10 MS/39 (±13)/70% women/8 (±5.8) months/3.8 (±1) Group 2: n = 11 MS/42.7 (±14)/64% women/8.6 (±8.8) months/4.9 (±1.2) | A closed-loop head-mounted display (HMD) system projecting either a checkerboard floor using a “glide-symmetric” “or transverse lines onto a self-paced treadmill |

| 1 session |

| Group 1:

| 15/27 |

| Bucchieri et al., 2024 [29]/Italy | n = 9 MS Age, sex, disease duration and EDSS: Not reported | Microsoft HoloLens 2 + Mixed Reality Toolkit (MRTK) + PTC Vuforia extension + two Mixed Reality exergames (ROCKapp for transversal pick-and-place; PICKapp for sagittal pick-and-place). |

| 1 session | System performance

| FPS: around 50 Hz in both applications; no significant difference between apps (p = 0.14) or across the five repetitions of each (p > 0.05). Missing hand-tracking samples: ROCKapp = 2.98%; PICKapp = 13.9%. Eye-tracking fully consistent (0% data loss). | 16/27 |

| Hernández et al., 2025 [25]/United States | n = 32 Group 1: n = 10 healthy young adults/21.9 (±3.4)/50% women Group 2: n = 12 healthy older adults/63.1(±4.4)/75% women Group 3: n = 10 MS/56.2 (±5.1)/80% women/disease duration not reported/range: 1–6; median = 3.75 | C-Mill self-paced instrumented treadmill (Motekforce Link)—AR targets and obstacles were presented on the treadmill belt surface. |

| 1 session |

|

| 18/27 |

| Pruszyńska et al., 2022 [26]/Poland | n = 30 Group 1: n = 15 relapsing-remitting MS/38.3 (±7.6)/73% women/9.9 (±5.4) years/EDDS not reported Group 2: n = 15 relapsing-remitting MS/41.4 (±4.6)/73% women/9.6 (±4.3) years/EDDS not reported | Neuroforma™ Augmented Reality system on computer with standard webcam, which overlays virtual objects and tracks hand movements for home-based upper-limb exercises. | Group 1 (AR intervention):

| Group 1:

|

|

| 18/27 |

| Sabatino et al., 2025 [27]/Italy | n = 21 Group 1: n = 9 MS/43.2 ± (13.7)/56% women/disease duration not reported/3.9 (±4) Group 2: n = 12 healthy control/42.1 (± 8.1)/67% women | Microsoft HoloLens 2 + ROCKapp Mixed Reality application for hand-tracking and eye-tracking during a pick-and-place task in MS patients. | Participants seated: pick-and-place 30 movements, 5 trials × 6 directions. With their hand resting on the table, they grasped a bottle at one of the holographic positions (North, South, East, or West), moved it in a straight line to another position, released it (triggering a virtual rocket), and then returned their hand to the table. The order of S, E and W moves is randomized; N always serves as the “home” position you return to for SN, EN and WN trials. | 1 session | Spatial Arc Length (SPARC). Number of Velocity Peaks (NVP). Movement Time (MT) Symmetry. Kurtosis. Number of Zero Crossing Points (N0C). NASA-TLX Questionnaire | The subgroup of MS participants without cerebellar symptoms showed worse values in SPARC, NVP, MT, kurtosis, N0C, and symmetry (p < 0.05). Each non-tremor MS patient (S1, S4, S6, S7) was compared directly against the healthy control group: S1: NVP, MT, symmetry, N0C; S4: MT, kurtosis; S6: SPARC; S7: NVP, MT, N0C (p > 0.05). Only the temporal demand subscale of the NASA-TLX differed significantly between groups (p ≈ 0.012) | 18/27 |

| Winter et al., 2021 [28]/Germany | n = 50 Group 1: n = 14 (MS 10; stroke 4)/MS 52.9 ± (7.6); stroke 52.9 (±8.2)/MS 70% women; stroke 75% women/EM 18.8 (± 10.1) months; stroke 7.5 (±5.3) months/3.9 (±4)/<6 Group 2: n = 36 healthy control/22 ± (3.7)/72% women | Immersive Virtual Reality (HTC Vive Head-Mounted Display (HMD) + foot trackers); semi-immersive VR (55″ monitor); conventional treadmill Augmented reality treadmill:

| Within-subject design: three treadmill conditions (no VR/monitor VR/immersive VR), each ~7.5 min; speed self-adjusted | Three 7.5 min runs; healthy in one day; patients over two days |

Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) NASA-TLX (Raw Task Load Index) Mood (0–10) Motivation (0–10) Sense of time (0–10) VR-Specific Questions (0–10) Presence (IPQ) Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ) Equipment & Display Questionnaire (EDQ) System Usability Scale (SUS) User Preference | For both groups, the walking speed in the HMD condition was higher than in treadmill training without VR and in the monitor condition. Healthy participants reported a higher motivation after the HMD condition as compared with the other conditions. Importantly, no side effects in the sense of simulator sickness occurred and usability ratings were high. No increases in heart rate were observed following the VR conditions. Presence ratings were higher for the HMD condition compared with the monitor condition for both user groups. Most of the healthy study participants (89%) and patients (71%) preferred the HMD-based training among the three conditions and most patients could imagine using it more frequently. | 19/27 |

| Study | Level of Evidence | Grade of Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Baram & Miller 2006 [23] | 2b | B |

| Baram & Miller 2010 [24] | 1b | A |

| Hernández et al., 2025 [25] | 3b | C |

| Bucchieri et al., 2024 [29] | 4 | C |

| Pruszyńska et al., 2022 [26] | 1b | A |

| Sabatino et al., 2025 [27] | 3b | C |

| Winter et al., 2021 [28] | 1b | A |

Strengths

| Weaknesses

|

Opportunities

| Threats

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández-Cañas, M.; Cano-de-la-Cuerda, R.; Marcos-Antón, S.; Onate-Figuérez, A. Augmented and Mixed Reality Interventions in People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121292

Fernández-Cañas M, Cano-de-la-Cuerda R, Marcos-Antón S, Onate-Figuérez A. Augmented and Mixed Reality Interventions in People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121292

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-Cañas, María, Roberto Cano-de-la-Cuerda, Selena Marcos-Antón, and Ana Onate-Figuérez. 2025. "Augmented and Mixed Reality Interventions in People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121292

APA StyleFernández-Cañas, M., Cano-de-la-Cuerda, R., Marcos-Antón, S., & Onate-Figuérez, A. (2025). Augmented and Mixed Reality Interventions in People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121292