The Use of Tele-Music Interventions in Supportive Cancer Care: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

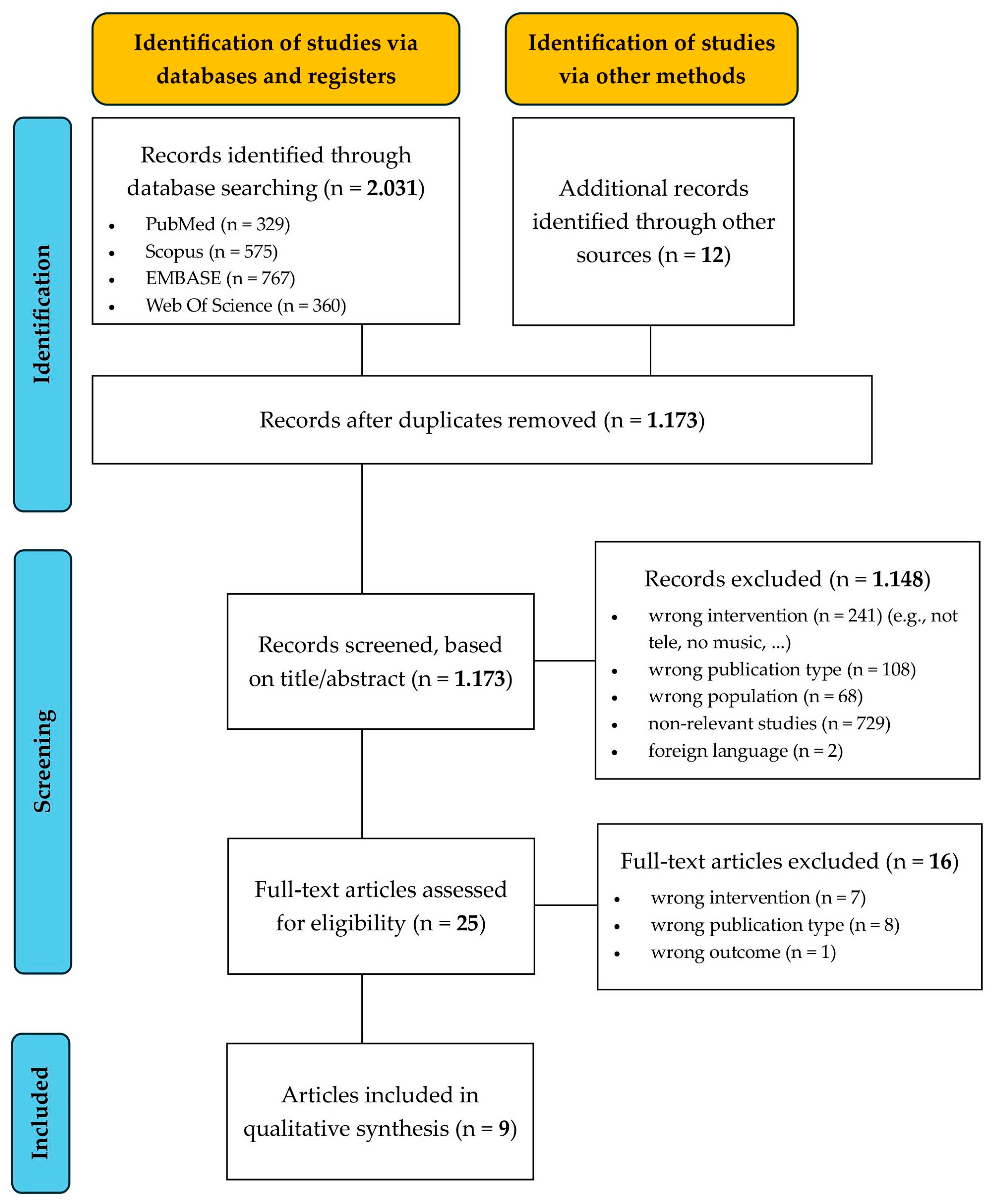

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. General Information

3.2. Delivery Format

3.3. Music Intervention Characteristics

3.4. Outcome Measures

3.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

| Study | Country + Year | Design | Subjects | Intervention + Delivery Format | Outcome Measures | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilgiç and Acaroğlu [46] | Turkey (2016) | Quasi-experimental study | Adult patients receiving chemotherapy (n = 70) | Music listening, during chemotherapy and the week after (at home) | Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS), General Comfort Questionnaire (GCQ), patient observation form | Significant between-group mean difference in chemotherapy symptoms (pain, exhaustion, nausea, anxiety, lethargy, lack of appetite, not feeling well). Significant improvements in total general comfort: physical, sociocultural, and psychospiritual comfort. |

| Fleszar-Pavlovic et al. [45] | USA (2025) | Qualitative study (focus groups, usability, and field testing) | Patients post allo-HSCT for myelodysplastic syndrome or leukemia (≥3 months in remission) (n = 11) | 8 modules eHealth-delivered mindfulness-based music therapy (eMBMT) intervention (8 modules) | (a) Interview questions regarding challenges, usefulness, and preferences. (b) Field testing using the think-aloud method (c) Usefulness, Satisfaction, and Ease of Use (USE) questionnaire | Positive evaluations for usefulness, ease of use, and satisfaction with the eMBMT platform 8. Identified areas for improvement (content representativeness, reduced text, enhanced guidance, diverse music options). |

| Folsom et al. [44] | USA (2021) | Case series | Cases on patients receiving care within an integrative oncology setting (n = 2) | Outpatient telehealth group music therapy, in- and outpatient individual telehealth music therapy (iPad and Zoom application) | Symptom burden (Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale), patient feedback interview (open-ended questions regarding patients’ experience) | Reduced anxiety, increased coping skills, enhanced social support, improved mood, and greater convenience |

| Knoerl et al. [41] * | USA (2022) | Single-arm pre/post-test intervention study | Adolescents and young adults receiving chemotherapy (n = 37) | Up to four individual mindfulness-based music therapy sessions (in-person or via Zoom) over twelve weeks | Anxiety (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Anxiety 4a), stress (Perceived Stress Scale), acceptability (Acceptability E-Scale) | Significant improvements in perceived stress, non-significant changes in anxiety. Highly rated satisfaction and acceptability |

| Knoerl et al. [43] * | USA (2023) | Secondary analysis of a single-arm pre-/post-test intervention study | Adolescents and young adults receiving chemotherapy (n = 31) | Up to four individual mindfulness-based music therapy sessions (in-person or via Zoom) over twelve weeks | Perceived Stress Scale, Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory Short Form, Patient-Reporting Outcome Measurement Information System | Potential influencing factors associated with anxiety improvement: higher baseline physical functioning, anxiety, fatigue, sleep disturbance, female sex, or virtual intervention delivery |

| Liou et al. [40] | USA (2025) | RCT (reported in a meeting abstract) | Cancer survivors (n = 300) | 7-weekly telehealth-based music therapy (MT) vs. cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) via Zoom | Primary: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) Secondary: depression, fatigue, insomnia, pain, cognitive function, quality of life | MT was non-inferior to CBT for short- and long-term anxiety reduction. Both treatments produced clinically meaningful, durable anxiety reduction. |

| Phillips et al. [42] * | USA (2023) | Qualitative study | Young adults (20–39 years old) receiving chemotherapy (n = 16) | Up to four individual mindfulness-based music therapy sessions (in-person or via Zoom) over twelve weeks | Semi-structured interviews on (1) reasons for participating, (2) prior music/mindfulness experience, (3) usual coping strategies, (4) experiences with participation, (5) use of strategies after study completion, (6) suggestions for improving the intervention | (1) Privacy issues attending virtual sessions, (2) sense of relaxation, (3) sense of connection to the music (in-person) and connection to mindfulness (virtual), (4) synergistic feeling practicing music and mindfulness together (virtual), (5) in-person delivery preferred to virtual delivery |

| Rabinowitch et al. [39] | Israel (2023) | RCT | Patients with current cancer diagnoses, either under or in between treatments (n = 30) | Online group music listening intervention (Balance-Space) vs. online group meditation intervention | Primary: NCCN Distress Thermometer; State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S); Visual Analog Scale (VAS for pain) Qualitative analysis of post-session open discussions | Significant reduction in perceived pain levels following the music intervention. No significant differences in distress or anxiety levels |

| Yildirim et al. [38] | Turkey (2024) | RCT | Patients with current cancer diagnoses, all receiving treatment at the University Hospital in Istanbul (n = 120) | 10-day online mindfulness-based stress reduction program combined with music therapy. Control group received standard care | Primary: State Trait Anxiety Inventory-State (STAI-S); Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWBS); Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | Significant reduction in stress and depression, and higher psychological well-being in the intervention group |

| Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) 2 | Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies—Interventions (ROBINS-I) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias due to randomization | Deviations from intended intervention | Missing outcome data | Outcome measurement | Selection of reported results | Overall | Classification of interventions | Deviations from intended intervention | Missing outcome data | Outcome measurement | Selection of reported results | Confounding | Selection of participants for the study | Overall | ||||||||

| Yildirim et al. (2024) [38] |  |  |  |  |  |  | Bilgiç and Acaroğlu (2017) [46] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | ||||||

| Rabinowitch et al. (2023) [39] |  |  |  |  |  |  | Knoerl et al. (2022) [41] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | ||||||

| Liou et al. (2025) [40] |  |  |  |  |  |  | Knoerl et al. (2023) [43] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | ||||||

| JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Series | JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Clear criteria for inclusion | Condition measurement | Valid identification methods | Consecutive inclusion | Complete inclusion | Reporting of demographics | Reporting of clinical information | Reporting of outcome results | Reporting of the presenting site demographic info | Appropriate statistical analysis | Philosophy ≅ methodology | Methodology ≅ research questions | Methodology ≅ data collection | Methodology ≅ data representation and analysis | Methodology ≅ interpretation | Researched is culturally/theoretically situated | Addressing the influence of the researcher | Representation of participants | Ethical approval | Relationship of conclusion to analysis | ||

| Folsom et al. (2021) [44] | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Phillips et al. (2023) [42] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Fleszar-Pavlovic et al. (2025) [45] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||||||

: Low risk;

: Low risk;  : Moderate risk;

: Moderate risk;  : High risk;

: High risk;  : Unclear; NA: Not applicable.

: Unclear; NA: Not applicable.4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.1.1. Methods and Components of Tele-Music Interventions

4.1.2. Psychosocial Outcomes of Music Interventions

4.1.3. Acceptability and Feasibility

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. PubMed Syntax

References

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheet Cancer. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Tack, L.; Schofield, P.; Boterberg, T.; Chandler, R.; Parris, C.N.; Debruyne, P.R. Psychosocial Care after Cancer Diagnosis: Recent Advances and Challenges. Cancers 2022, 14, 5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontaine, C.; Libert, I.; Echterbille, M.-A.; Bonhomme, V.; Botterman, J.; Bourgonjon, B.; Brouillard, V.; Courtin, Y.; Buck, J.D.; Debruyne, P.R.; et al. Evaluating pain management practices for cancer patients among health professionals in cancer and supportive/palliative care units: A Belgian survey. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, L.; Lefebvre, T.; Tack, L.; Eygen, K.V.; Cool, L.; Schofield, P.A.; Boterberg, T.; Rijdt, T.D.; Verhaeghe, A.; Verhelle, K.; et al. Pain Medication Adherence in Patients with Cancer: A Pragmatic Review. Pain Med. 2022, 23, 782–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tack, L.; Maenhoudt, A.-S.; Ketelaars, L.; Zutter, J.D.; Pinson, S.; Keunebrock, L.; Haaker, L.; Deckmyn, K.; Gheysen, M.; Kenis, C.; et al. Diagnostic Performance of Screening Tools for Depressive Symptoms in Vulnerable Older Patients with Cancer Undergoing Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA): Results from the SCREEN Pilot Study. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 1805–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tack, L.; Mertens, L.; Vandeweyer, M.; Florin, F.; Pauwels, E.; Baert, T.; Boterberg, T.; Fontaine, C.; Geldhof, K.; Lamot, C.; et al. Targeting Fear of Cancer Recurrence with Internet-Based Emotional Freedom Techniques (iEFT) and Mindfulness Meditation Intervention (iMMI) (BGOG-gyn1b/REMOTE). Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lycke, M.; Lefebvre, T.; Pottel, L.; Pottel, H.; Ketelaars, L.; Stellamans, K.; Van Eygen, K.; Vergauwe, P.; Werbrouck, P.; Cool, L.; et al. Subjective, but not objective, cognitive complaints impact long-term quality of life in cancer patients. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2019, 37, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lycke, M.; Lefebvre, T.; Pottel, L.; Pottel, H.; Ketelaars, L.; Stellamans, K.; Eygen, K.V.; Vergauwe, P.; Werbrouck, P.; Goethals, L.; et al. The distress thermometer predicts subjective, but not objective, cognitive complaints six months after treatment initiation in cancer patients. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2017, 35, 741–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tack, L.; Lefebvre, T.; Lycke, M.; Langenaeken, C.; Fontaine, C.; Borms, M.; Hanssens, M.; Knops, C.; Meryck, K.; Boterberg, T.; et al. A randomised wait-list controlled trial to evaluate Emotional Freedom Techniques for self-reported cancer-related cognitive impairment in cancer survivors (EMOTICON). eClinicalMedicine 2021, 39, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paley, C.A.; Boland, J.W.; Santarelli, M.; Murtagh, F.E.M.; Ziegler, L.; Chapman, E.J. Non-pharmacological interventions to manage psychological distress in patients living with cancer: A systematic review. BMC Palliat. Care 2023, 22, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadet, T.; Davis, C.; Elks, J.; Wilson, P. A Holistic Model of Care to Support Those Living with and beyond Cancer. Healthcare 2016, 4, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, M.; Moschopoulou, E.; Herrington, E.; Deane, J.; Roylance, R.; Jones, L.; Bourke, L.; Morgan, A.; Chalder, T.; Thaha, M.A.; et al. Review of systematic reviews of non-pharmacological interventions to improve quality of life in cancer survivors. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevino, K.M.; Raghunathan, N.; Latte-Naor, S.; Polubriaginof, F.C.G.; Jensen, C.; Atkinson, T.M.; Emard, N.; Seluzicki, C.M.; Ostroff, J.S.; Mao, J.J. Rapid deployment of virtual mind-body interventions during the COVID-19 outbreak: Feasibility, acceptability, and implications for future care. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 29, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tack, L.; Lefebvre, T.; Blieck, V.; Cool, L.; Pottel, H.; Van Eygen, K.; Derijcke, S.; Vergauwe, P.; Schofield, P.; Chandler, R.; et al. Acupuncture as a Complementary Therapy for Cancer Care: Acceptability and Preferences of Patients and Informal Caregivers. J. Acupunct. Meridian Stud. 2021, 14, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabbe, M.; Vrancken, D.; Van Stappen, V.; Declerck, I. S06-2: Moving Cancer Care: The importance of exercise during and after a cancer treatment. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34, ckae114.223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradt, J.; Dileo, C.; Myers-Coffman, K.; Biondo, J. Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, CD006911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramaglia, C.; Gambaro, E.; Vecchi, C.; Licandro, D.; Raina, G.; Pisani, C.; Burgio, V.; Farruggio, S.; Rolla, R.; Deantonio, L.; et al. Outcomes of music therapy interventions in cancer patients-A review of the literature. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2019, 138, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xing, X.; Shi, X.; Yan, P.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, K. The effectiveness of music therapy for patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 1111–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Distress Management (Version 2.2024). 2024. Available online: https://apos-society.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/distress-2024.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Bradt, J.; Potvin, N.; Kesslick, A.; Shim, M.; Radl, D.; Schriver, E.; Gracely, E.J.; Komarnicky-Kocher, L.T. The impact of music therapy versus music medicine on psychological outcomes and pain in cancer patients: A mixed methods study. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, C.; Erkkilä, J.; Bonde, L.O.; Trondalen, G.; Maratos, A.; Crawford, M.J. Music therapy or music medicine? Psychother. Psychosom. 2011, 80, 304–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raglio, A.; Oasi, O. Music and health: What interventions for what results? Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Music and Health: What You Need to Know. 2022. Available online: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/music-and-health-what-you-need-to-know (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Bonny, H.L. Sound as Symbol: Guided Imagery and Music in Clinical Practice. Music Ther. Perspect. 1989, 6, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus MC. Muziek als Medicijn. Publicaties Onderzoek. Available online: https://erasmusmcfoundation.nl/muziekalsmedicijn/publicaties/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Yang, H.-F.; Chang, W.-W.; Chou, Y.-H.; Huang, J.-Y.; Liao, Y.-S.; Liao, T.-E.; Tseng, H.-C.; Chang, S.-T.; Chen, H.L.; Ke, Y.-F.; et al. Impact of background music listening on anxiety in cancer patients undergoing initial radiation therapy: A randomized clinical trial. Radiat. Oncol. 2024, 19, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anawade, P.A.; Sharma, D.; Gahane, S. A Comprehensive Review on Exploring the Impact of Telemedicine on Healthcare Accessibility. Cureus 2024, 16, e55996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, G.W.; Braga, S.; Bystricky, B.; Qvortrup, C.; Criscitiello, C.; Esin, E.; Sonke, G.S.; Martínez, G.A.; Frenel, J.-S.; Karamouzis, M.; et al. Global cancer control: Responding to the growing burden, rising costs and inequalities in access. ESMO Open 2018, 3, e000285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Lopez, G.; Powers-James, C.; Fellman, B.M.; Chunduru, A.; Li, Y.; Bruera, E.; Cohen, L. Integrative Oncology Consultations Delivered via Telehealth in 2020 and In-Person in 2019: Paradigm Shift During the COVID-19 World Pandemic. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 1534735421999101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, D.; Yaguda, S.; Quick, D.; Greiner, R.; Hariharan, S.; Bailey-Dorton, C. Rapid Practice Change During COVID-19 Leads to Enduring Innovations and Expansion of Integrative Oncology Services. Oncol. Issues 2021, 36, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.M.; Sanders, S.; Carter, M.; Honeyman, D.; Cleo, G.; Auld, Y.; Booth, D.; Condron, P.; Dalais, C.; Bateup, S.; et al. Improving the translation of search strategies using the Polyglot Search Translator: A randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2020, 108, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, 4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, 4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Barker, T.H.; Moola, S.; Tufanaru, C.; Stern, C.; McArthur, A.; Stephenson, M.; Aromataris, E. Methodological quality of case series studies: An introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2127–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, D.; Çiriş Yildiz, C.; Ozdemir, F.A.; Harman Özdoğan, M.; Can, G. Effects of a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program on Stress, Depression, and Psychological Well-being in Patients With Cancer: A Single-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer Nurs. 2024, 47, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitch, T.C.; Dassa, A.; Sadot, A.S.; Trincher, A. Outcomes and experiences of an online Balance-Space music therapy intervention for cancer patients: A mixed methods study. Arts Psychother. 2023, 82, 101998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liou, K.T.; Bradt, J.; Baser, R.E.; Panageas, K.; Li, Q.S.; Lopez, A.M.; Currier, M.B.; McConnell, K.; Mao, J.J. Music therapy versus cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in cancer survivors: A telehealth-based randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 12003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoerl, R.; Mazzola, E.; Woods, H.; Buchbinder, E.; Frazier, L.; LaCasce, A.; Li, B.T.; Luskin, M.R.; Phillips, C.S.; Thornton, K.; et al. Exploring the Feasibility of a Mindfulness-Music Therapy Intervention to Improve Anxiety and Stress in Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2022, 63, e357–e363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C.S.; Bockhoff, J.; Berry, D.L.; Buchbinder, E.; Frazier, A.L.; LaCasce, A.; Ligibel, J.; Luskin, M.R.; Woods, H.; Knoerl, R. Exploring Young Adults’ Perspectives of Participation in a Mindfulness-Based Music Therapy Intervention Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2023, 12, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoerl, R.; Mazzola, E.; Woods, H.; Buchbinder, E.; Frazier, L.; LaCasce, A.; Luskin, M.R.; Phillips, C.S.; Thornton, K.; Berry, D.L.; et al. Exploring Influencing Factors of Anxiety Improvement Following Mindfulness-Based Music Therapy in Young Adults with Cancer. J. Music Ther. 2023, 60, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folsom, S.; Christie, A.J.; Cohen, L.; Lopez, G. Implementing Telehealth Music Therapy Services in an Integrative Oncology Setting: A Case Series. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 15347354211053647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleszar-Pavlovic, S.E.; Noriega Esquives, B.; Lovan, P.; Brito, A.E.; Sia, A.M.; Kauffman, M.A.; Lopes, M.; Moreno, P.I.; Koru-Sengul, T.; Gong, R.; et al. Development of an eHealth Mindfulness-Based Music Therapy Intervention for Adults Undergoing Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Qualitative Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2025, 9, e65188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgiç, Ş.; Acaroğlu, R. Effects of Listening to Music on the Comfort of Chemotherapy Patients. West J. Nurs. Res. 2017, 39, 745–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleszar-Pavlovic, S.E.; Esquives, B.N.; Brito, A.E.; Sia, A.M.; Kauffman, M.A.; Lopes, M.; Moreno, P.I.; Koru-Sengul, T.; Gong, R.; Wang, T.; et al. eHealth Mindfulness-based Music Therapy for Patients Undergoing Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2024, 142, 107577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liou, K.; McConnell, K.; Currier, M.; Baser, R.; MacLeod, J.; Walker, D.; Casaw, C.; Wong, G.; Piulson, L.; Popkin, K.; et al. Telehealth-Based Music Therapy Versus Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety in Cancer Survivors: Rationale and Protocol for a Comparative Effectiveness Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2023, 12, e46281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.; Snaith, R. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.D. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruera, E.; Kuehn, N.; Miller, M.J.; Selmser, P.; Macmillan, K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): A simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J. Palliat. Care 1991, 7, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ader, D.N. Developing the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Med. Care 2007, 45, S1–S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolcaba, K.Y. Holistic comfort: Operationalizing the construct as a nurse-sensitive outcome. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1992, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, A. Measuring Usability with the USE Questionnaire. Usability Interface 2001, 8, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tariman, J.D.; Berry, D.L.; Halpenny, B.; Wolpin, S.; Schepp, K. Validation and testing of the Acceptability E-scale for web-based patient-reported outcomes in cancer care. Appl. Nurs Res. 2011, 24, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, F.W.K.; Heath, A.S.; Moore, T.F.; Kim, S.; Heath, E.I. Using Music as a Tool for Distress Reduction During Cancer Chemotherapy Treatment. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2023, 19, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köhler, F.; Martin, Z.S.; Hertrampf, R.S.; Gäbel, C.; Kessler, J.; Ditzen, B.; Warth, M. Music Therapy in the Psychosocial Treatment of Adult Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 651, Erratum in Front Psychol. 2020, 11, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, G.J.; Silverman, M.J. Immediate effects of single-session music therapy on affective state in patients on a post-surgical oncology unit: A randomized effectiveness study. Arts Psychother. 2015, 44, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daykin, N.; McClean, S.; Bunt, L. Creativity, identity and healing: Participants’ accounts of music therapy in cancer care. Health 2007, 11, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingle, G.A.; Sharman, L.S.; Bauer, Z.; Beckman, E.; Broughton, M.; Bunzli, E.; Davidson, R.; Draper, G.; Fairley, S.; Farrell, C.; et al. How Do Music Activities Affect Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review of Studies Examining Psychosocial Mechanisms. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 713818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoerl, R.; Phillips, C.S.; Berfield, J.; Woods, H.; Acosta, M.; Tanasijevic, A.; Ligibel, J. Lessons learned from the delivery of virtual integrative oncology interventions in clinical practice and research during the COVID-19 pandemic. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 4191–4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, S.L.; Springs, S.; Edwards, E.; Golden, T.L.; Johnson, J.K.; Burns, D.S.; Belgrave, M.; Bradt, J.; Gold, C.; Habibi, A.; et al. Frontiers|Reporting Guidelines for Music-based Interventions: An update and validation study. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1551920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, L.-T.; Xu, N.; Ke, F.; Lan, L.; Li, L.; Liu, W.; Chen, X. Effects of smartphone-based music intervention on improving emotional and psychosomatic symptoms of patients with hematological malignancy: A study protocol for a non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241286941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullapally, S.K.; Panda, P.K.; Kalaivani, C.; Gokulakrishnan, T.; Ramana, P.D.M.V.; Dasapathi, V.S.K.K.; Pallia, S. Artificial intelligence based music therapy intervention in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy in oncology day care (MUSICC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Campli San Vito, P.; Yang, X.; Brewster, S.; Street, A.; Fachner, J.; Fernie, P.; Muller-Rodriguez, L.; Hung Hsu, M.; Odell-Miller, H.; Shaji, H.; et al. RadioMe: Adaptive Radio to Support People with Mild Dementia in Their Own Home. Front. Artif. Intell. Appl. 2023, 368, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brungardt, A.; Wibben, A.; Tompkins, A.F.; Shanbhag, P.; Coats, H.; LaGasse, A.B.; Boeldt, D.; Youngwerth, J.; Kutner, J.S.; Lum, H.D. Virtual Reality-Based Music Therapy in Palliative Care: A Pilot Implementation Trial. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, A.; Castellanos, C.; Pasquier, P. Digital music interventions for stress with bio-sensing: A survey. Front. Comp. Sci. 2023, 5, 1165355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaatar, M.T.; Alhakim, K.; Enayeh, M.; Tamer, R. The transformative power of music: Insights into neuroplasticity, health, and disease. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2023, 35, 100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Tataru, C.P.; Florian, I.A.; Covache-Busuioc, R.A.; Bratu, B.G.; Glavan, L.A.; Bordeianu, A.; Dumitrascu, D.I.; Ciurea, A.V. Cognitive Crescendo: How Music Shapes the Brain’s Structure and Function. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Sánchez, N.; Pastor, R.; Eerola, T.; Escrig, M.A.; Pastor, M.C. Musical preference but not familiarity influences subjective ratings and psychophysiological correlates of music-induced emotions. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2022, 198, 111828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachner, J.C.; Maidhof, C.; Grocke, D.; Pedersen, I.N.; Trondalen, G.; Tucek, G.; Bonde, L.O. “Telling me not to worry …” Hyperscanning and Neural Dynamics of Emotion Processing During Guided Imagery and Music. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mertens, L.; Tack, L.; Boterberg, T.; Fachner, J.; Muller-Rodriguez, L.; Vandeweyer, M.; Demasure, S.; Hanssens, M.; Loyson, T.; Goethals, L.; et al. The Use of Tele-Music Interventions in Supportive Cancer Care: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121266

Mertens L, Tack L, Boterberg T, Fachner J, Muller-Rodriguez L, Vandeweyer M, Demasure S, Hanssens M, Loyson T, Goethals L, et al. The Use of Tele-Music Interventions in Supportive Cancer Care: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121266

Chicago/Turabian StyleMertens, Lore, Laura Tack, Tom Boterberg, Jörg Fachner, Leonardo Muller-Rodriguez, Marte Vandeweyer, Sofie Demasure, Marianne Hanssens, Tine Loyson, Laurence Goethals, and et al. 2025. "The Use of Tele-Music Interventions in Supportive Cancer Care: A Systematic Review" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121266

APA StyleMertens, L., Tack, L., Boterberg, T., Fachner, J., Muller-Rodriguez, L., Vandeweyer, M., Demasure, S., Hanssens, M., Loyson, T., Goethals, L., Kindts, I., Denys, H., Schofield, P., Najlah, M., & Debruyne, P. R. (2025). The Use of Tele-Music Interventions in Supportive Cancer Care: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121266