Abstract

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that affects a large number of young people in the world. The current treatments for children living with ADHD combine different approaches, such as pharmacological, behavioral, cognitive, and psychological treatment. However, the computer science research community has been working on developing non-pharmacological treatments based on novel technologies for dealing with ADHD. For instance, social robots are physically embodied agents with some autonomy and social interaction capabilities. Nowadays, these social robots are used in therapy sessions as a mediator between therapists and children living with ADHD. Another novel technology for dealing with ADHD is serious video games based on a brain–computer interface (BCI). These BCI video games can offer cognitive and neurofeedback training to children living with ADHD. This paper presents a systematic review of the current state of the art of these two technologies. As a result of this review, we identified the maturation level of systems based on these technologies and how they have been evaluated. Additionally, we have highlighted ethical and technological challenges that must be faced to improve these recently introduced technologies in healthcare.

1. Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a psychiatric neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by inappropriate levels of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity [1]. ADHD is the most common mental health diagnosis in children that affects the life of a large number of young people in the world [2]. There is evidence that some children living with ADHD commonly present other conditions in addition to the symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity, and lack of concentration, such as a poor tolerance of frustration, low self-esteem, and mood change [3]. Even worse, when this mental condition persists into adulthood, these people present higher college dropout rates, poor job performance, difficulty keeping a job, and higher-risk impulsive behaviors such as substance abuse, self-harm, and suicide attempts [4]. Nevertheless, timely treatment in childhood can improve mental health and lifestyle during adulthood [5]. On the other hand, there are studies that show that some adolescents live pretty well with ADHD. According to [6], a group of adolescents considered ADHD a personal characteristic that comprised part of their identity. Furthermore, some adolescents reported that ADHD gave them strengths (e.g., energetic, fun, creative, outgoing, talkative, and funny), and they were happy with these aspects of their personalities, despite them also posing difficulties for them.

Digital Technologies for Supporting Children Living with ADHD

In recent years, non-pharmacological treatments, such as behavioral interventions and cognitive training [7,8,9], have been an alternative to avoid using medications in people living with ADHD. Additionally, the computer science and mental health care research communities have been working together on developing novel technological systems for dealing with ADHD, such as BCI video games [10,11], virtual reality [12], augmented reality [13], artificial intelligence [14], robotics [15], and eye-tracking systems [16,17]. In recent years, there has been growing interest in how people living with ADHD can use social robots and BCI video games to support their health and well-being. These technologies have been considered to be implemented in therapy applications in order to make therapeutic work more attractive to children living with ADHD [18,19,20]. Therefore, robots and BCI video games are designed with playful aspects in order to strengthen the children’s intrinsic motivation and maximize the cognitive training’s positive effects through better -children’s involvement [18,20]. Regarding social robots, they have also been used as a support tool in the homework activities of children living with ADHD [21]. Thus, social robots aim to support therapists by automating the supervision, coaching, motivation, and companionship aspects of interactions with children living with ADHD.

In contrast, BCI video games are serious games characterized by implementing a brain–computer interface (BCI) to interact with the video game rather than a keyboard or joystick. BCI video games are also characterized by including the neurofeedback technique. Thus, BCI video games can help maintain the ADHD children’s motivation and attention to the task and guide them to achieve a specified goal (namely, specific changes in electrical activity in the brain) by maintaining a specific “mental state.” Studies have shown that children living with ADHD had improved behavioral and cognitive variables after frequency training (e.g., theta/beta) [10,22,23].

Studies reported in the literature discuss several recent large-scale projects (e.g., [22,24,25,26,27,28,29]). These projects have explored child–robot interaction and child–video game interaction to help children with developmental disorders such as ADHD. This study presents a systematic review from an interdisciplinary approach to the current state of these two technologies. The research questions used to guide this review were as follows:

- Q1: How have social robots and BCI video games been evaluated?

- Q2: Are there still open challenges in social robots and BCI video games to improve their impact and benefit on children living with ADHD?

These questions aim to provide a structured methodology for categorizing the current state of the art of these two technologies for dealing with ADHD. These questions also seek to clarify the current research limitations for future directions. The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 offers a detailed systematic review of the current state of the art regarding social robots for dealing with ADHD. Section 3 provides a systematic review of the current state of the art regarding BCI video games for dealing with ADHD. After that, Section 4 offers a discussion from an interdisciplinary approach of the results published in the literature to address the research questions. Section 5 describes the challenges with these two technologies that still need to be addressed to offer effective computational systems for dealing with ADHD. Finally, Section 6 provides some concluding remarks about the current state of systems based on social robots or BCI video games focused on supporting non-pharmacological treatments for children living with ADHD.

2. Study 1: Social Robots for Dealing with ADHD

2.1. Search Strategy

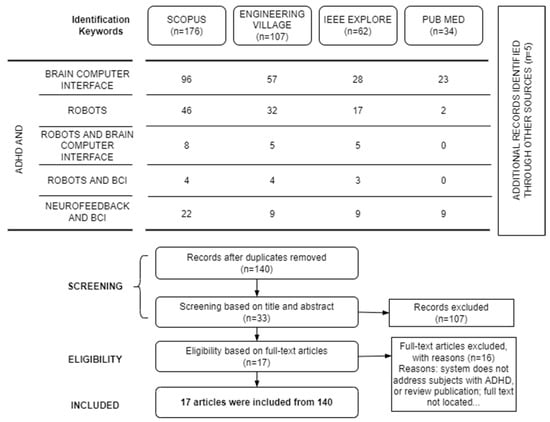

This study was conducted through a systematic literature review called the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [30]. Papers were sought from four major online databases: PubMed to provide a medical perspective, Engineering Village and IEEE Xplore to provide an engineering perspective, and Scopus to provide a cross-disciplinary perspective. The search was limited to papers published from January 2010 to 15 June 2022. Figure 1 shows the search strategy and keywords used to search for papers on PubMed, Engineering Village, IEEE Xplore, and Scopus.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of robots in ADHD care.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were considered: (1) papers that have been published in international journals or international congresses; (2) papers written in English; and (3) papers that described the conceptualization, development, testing, or evaluation of robots for use with people living with ADHD. Additionally, the following exclusion criteria were considered: (1) papers dealing exclusively with ADHD, (2) papers on robots for use with people without identified health conditions, and (3) review papers.

2.3. Screening

The screening process was divided into two phases (see Figure 1). The first phase involved removing duplicate records. After that, two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts to remove those papers that did not meet the eligibility criteria. In the second phase, the same two authors obtained and screened full texts for the remaining papers. Any differences were resolved through consulting with a third author.

2.4. Search Results

The initial search for social robots in ADHD care was conducted with different combinations of word keys (see Figure 1), producing 332 results. Once duplicates were removed, 140 publications remained. The screening of titles and abstracts resulted in a working pool of 33 publications. Full-text articles were thoroughly screened according to the eligibility criteria, resulting in 17 publications that were considered for studying and then describing the recent advances and challenges in systems based on social robots for dealing with ADHD. Of the 17 papers included, 52.94% (9/17) were papers published in a journal, and 47.06% (8/17) were papers published at an international conference.

Table 1 shows how each paper was sorted regarding the target population and proposed application type. Thus, 94.12% of the papers found in the literature focused on social robots for children living with ADHD, and just 5.88% focused on social robots for undergraduate students living with ADHD. According to the papers’ proposed aims and application types, we identified one paper that presents a methodology for designing robot-assisted therapy [24]. This methodology is characterized by proposing an iterative approach where patients, parents, and therapists take the role of stakeholders to ensure a customized implementation of the technology that meets patients’ specific needs. On the other hand, two of the reviewed papers propose a novel system for supporting the diagnosis of ADHD [25,31], whereas in [25], the aim was to investigate the clinical effectiveness of a new robot-assisted kinematic measure for ADHD. In [31], a robot-assisted test for measuring ADHD symptoms in children is presented. The rest of the reviewed papers propose a novel system supporting rehabilitation therapies for children living with ADHD. Also, we found that some systems have been designed for children living with ADHD who have an additional developmental disability, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [18,24,32,33], oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) [27], cerebral palsy (CP) [34], and learning disability [33]. Additionally, Table 1 shows the type of social robot implemented in each proposed system and the input signal or sensors used to assess the children’s behavior. Thus, eleven systems implemented humanoid robots like Nao [18,24,32,35], Silbot [25,31], Robotis Bioloid [36], Pepper [19], Sanbot Elf [37,38], and Ifbot [39], and just six systems implemented a social robot developed ad hoc [21,27,33,34,40,41]. Finally, we highlighted the type of environment used in each system. It could be virtual, real, or hybrid. This last type means that participants interact with a physical robot, but they also interact with software commonly hosted on a secondary device such as a desk computer, laptop, or tablet. Ten systems are based on a real environment, and seven are based on a hybrid one. None of the systems identified in the literature are based on a purely virtual environment.

Table 1.

The current state of social robots for dealing with ADHD.

Table 2 summarizes the results reported in the literature on developing social robots for dealing with ADHD. In total, 16 of 17 papers described in this review presented a study. According to the characteristics of each study, we classified them as feasibility, effectiveness, and usability studies. A total of 56% of studies reported in the literature were considered feasibility studies. These studies focused on testing the proposed system’s potential for helping children living with ADHD. In total, 25% of the studies were classified as usability studies. These studies focused on evaluating the satisfaction and acceptance level of the proposed system. Finally, just 19% of studies were classified as effectiveness studies. These studies investigated the clinical effectiveness of robot-assisted therapy on children living with ADHD. Additionally, we identified that the reported studies in the literature involved people with different characteristics. For instance, two studies involved just healthy children [35,41], one study involved undiagnosed children with potential symptoms of ADHD [21,25,31,36], six studies involved children living with ADHD and other developmental disorders [18,24,27,32,34,38], and three studies involved just children living with ADHD [19,37,40]. Table 2 shows the participants’ characteristics in each study case, such as the number of participants, age, gender, and health conditions.

Table 2.

Studies and results of using social robots for dealing with ADHD.

Moreover, we identified that the duration of these studies was very variable. For example, some studies were based on a few sessions (e.g., four sessions) and involved fewer than ten participants in the trials (e.g., [19,37]), whereas other studies were based on many sessions (e.g., multiple sessions during a month or more) with more than ten children (e.g., [25,27,31,32]). We observed that most of these studies were conducted in collaboration with experts in the healthcare area. The last column of Table 2 summarizes the results obtained in each study.

According to the results reported in the literature, we consider that systems based on social robots for dealing with ADHD are promising technology. However, the use of social robots for diagnosing or treating children living with ADHD is still in its first phases of development. Also, based on the number of participants involved and the duration of the trials reported in the literature, we have considered that the results reported in these studies can be regarded as preliminary results. Therefore, more trials with more significant populations are needed to validate such results.

3. Study 2: BCI Video Games for Dealing with ADHD

3.1. Search Strategy

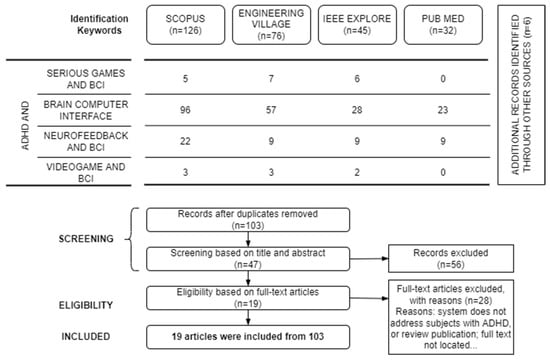

This second study used the same strategy implemented in the previous study of social robots. Therefore, papers were sought from four major online databases: PubMed to provide a medical perspective, Engineering Village and IEEE Xplore to provide an engineering perspective, and Scopus to provide a cross-disciplinary perspective. The search was limited to papers published from January 2010 to 15 June 2022. The keywords used for searching papers were “ADHD” AND “serious games” AND “BCI”, “ADHD” AND “brain-computer interface,” “ADHD” AND “neurofeedback” AND “BCI”, “ADHD” AND “videogame” AND “BCI”. These keywords were adapted according to the user interface offered by each online database. Figure 2 shows the search strategy used in this study.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of BCI video games in ADHD care.

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

Publications were included if they were published in international journals or international congresses, were written in English, and described BCI video games’ conceptualization, development, testing, or evaluation for people living with ADHD. On the other hand, publications on ADHD exclusively and BCI video games for use with people without identified health conditions, as well as review papers, were excluded.

3.3. Screening

The screening process was divided into two phases (see Figure 2). The first phase involved removing duplicate records. After that, two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts to remove those papers that did not meet the eligibility criteria. In the second phase, the same two authors obtained and screened full texts for the remaining papers. Finally, any discrepancy was resolved through consulting with a third author.

3.4. Search Results

After the screening and eligibility criteria were applied, 19 papers from the initial 103 candidates remained for review. The selected papers were utilized to investigate the features of systems based on BCI video games for dealing with ADHD. Afterward, the characteristics of each system, such as the advantages and disadvantages, experimental environment, and applications, were discussed. Figure 2 shows the flow diagram of PRISMA with the results obtained after applying the keywords in the queries.

Table 3 summarizes BCI video game projects reported in the literature. These research projects focus on the cognitive training of both healthy people and people living with ADHD. BCI video games commonly use the neurofeedback approach. Therefore, the primary input signal of BCI video games comes from the human brain’s bioelectrical activity. Thus, these systems seek to offer an alternative or complement to traditional pharmacological treatments. BCI video games aim to improve different cognitive capabilities, such as attention, concentration, spatial memory, short and long memory, and motor skills (e.g., [28,42,43,44]). These systems are commonly designed using a playful approach where the BCI video game offers challenges, missions, goals, and different complexity levels to catch the participants’ interest and attention.

Table 3.

The current state of BCI video games for dealing with ADHD.

A total of 14 of the 19 projects described in Table 3 were designed to support the children’s cognitive training, whereas the remaining projects included in Table 3 did not consider the participants’ age for their design. Additionally, we observed that BCI video games offer a wide variety of themes such as farms, racing, spaceships, forest, classroom, puzzle, mazes, and under the ocean. However, research questions may arise for future research, such as whether this kind of video game may generate a type of addiction and how skills obtained through playing these BCI video games can be applied in daily life.

Table 4 describes trials and the results of each study presented in Table 3. Also, the main characteristics of participants involved in trials, such as the number of participants, their age, gender, and health conditions, are included in Table 4. We identified that 53% of the works reported in the literature focused on studying the effectiveness of systems based on BCI video games, 32% focused on studying the feasibility of using these systems on children living with ADHD, 11% focused on researching whether changes occurred at an anatomical brain level in children living with ADHD after using a BCI video game, and only 5% focused on testing the usability of BCI video games on children living with ADHD.

Table 4.

Studies and results of using BCI video games for dealing with ADHD.

Three types of trials were identified in the effectiveness studies: (i) trials that just involved an experimental group formed by children living with ADHD [44,51], (ii) trials similar to the previous but with healthy people [43,55], and (iii) trials that involved children living with ADHD who were divided into experimental and control groups to compare the results obtained with both groups [10,22,23,28,49,50]. Additionally, we observed that 50% of these studies involved more than 50 children living with ADHD, whereas the rest involved between 20 and 26 children living with ADHD. Furthermore, we observed that most feasibility studies involved healthy participants instead of participants living with ADHD. This is because the systems proposed in these papers are still in the early stages of development.

4. Discussion

This systematic review of social robots and BCI video games was conducted from an interdisciplinary approach. Therefore, the results reported in this paper focused on highlighting relevant information in engineering and healthcare areas. For instance, Table 1 and Table 3 show useful information for the engineering area. This information is related to the type of application developed in each paper. We grouped applications into three groups. The first group includes applications for supporting rehabilitation therapies. Most applications identified in the literature belong to this group. A second group of applications focused on supporting ADHD diagnosis. An application in this group claims to have reached 97% confidence in identifying children living with ADHD [31]. The last group involves applications focused on supporting neuroscience research. Additionally, Table 1 and Table 3 present the aim of each paper, such as proposing a methodology for designing social robots or BCI video games, presenting the architectural design of these systems, and comparing their performance, among other objectives.

Concerning the robot-based applications, we identified that the most common robots used in these applications are humanoid robots such as Nao, Silbot, Robotis Bioloid, Pepper, Sanbot Elf, and Ifbot. We also highlighted input signals and environments used in such applications (real, virtual, and hybrid). For this last characteristic, we identified that the real environment has been used most in these applications. Regarding BCI-based video game applications, we identified that the environments more used (listed in order of preference) are 3D, 2D, virtual reality, and mixed reality environments.

Although most papers in the literature were published in engineering journals or proceedings, we could identify relevant information about these two technologies for the healthcare area. Table 2 and Table 4 describe the main characteristics of participants involved in trials, such as the number of participants, their gender, age, and health conditions. Additionally, these tables offer a brief description of the results reported in each study, including the acceptability level of technology. Also, we tried to identify whether these technologies can significantly reduce some symptoms associated with ADHD or improve any skill ability. We observed that systems based on social robots or BCI video games are designed mainly to reduce attention deficit and improve some skills, such as learning, writing, spatial memory, working memory, communication, and interaction.

This systematic review lets us answer our two research questions. Most systems reported in the literature are still in the developing and testing phases, and just two applications named Focus Pocus [10] and EndeavorRx [56] are commercialized and prescribed for treating children living with ADHD. In total, 88% of robot-based applications found in the literature have been tested involving people living with ADHD. Furthermore, some of these applications have involved people living with ADHD who have an additional developmental disability, such as ASD [18,24,32,33], ODD [27], CP [34], and learning disability [33]. These applications have been tested for different purposes, such as validating their functionality and exhibiting their potential benefits on people living with ADHD.

On the other hand, BCI video game systems have been evaluated in their functionality and usability by including healthy participants [29,45,47,48] and participants living with different levels of ADHD [54]. This kind of system has been compared against the most used neurofeedback system (cartoon-based). The results published in [28] suggest that BCI video games can be better than cartoon-based systems for maintaining people’s attention. These comparisons also include medicine-based treatments, where BCI video game systems showed similar results in the reduction in ADHD symptoms, especially in the inattentive symptoms [22,46,50]. Additionally, evaluations with healthy individuals revealed that the BCI video game systems could improve attention levels in healthy and ADHD individuals [43,54].

Finally, we identified a set of challenges that developers must face for developing flexible systems that can be reconfigured and customized according to the behavior and deficit of each individual. These challenges are described in detail in the following section.

5. Open Challenges

This section describes the challenges identified during the systematic literature review for developing computational systems based on social robots or BCI video games to treat ADHD. These challenges are related to the system’s target, the design of a general system for dealing with all types of ADHD, the problem of customizing training exercises, and some ethical issues, such as making sure not to compromise the children’s social–emotional development.

- Diagnosing ADHD. The symptoms presented by a child living with ADHD can differ from those of another child living with ADHD. This is because there are three different subtypes of ADHD [57]: predominantly inattentive type (ADHD-I), predominantly hyperactive/impulsive type (ADHD-HI), and combined type (ADHD-C). To complicate matters even more, there are people living with ADHD who have an additional neurodevelopmental disorder, such as ASD [24,28], ODD [27], and anxiety problems [27]. Therefore, developing a general system for diagnosing people with diverse forms of ADHD represents a hard challenge.

- Customizing cognitive training exercises. Customizing cognitive training exercises according to the characteristics of each person is another hard challenge for engineers and researchers involved in designing general systems based on robots and BCI video games for dealing with ADHD [18,24,32]. This is due to different factors, such as the subtype of ADHD [57], the level of ADHD (from moderate to severe) [58], the preferences of each person [18,32], and poor adaptation to the users’ level of expertise with the technology leading to frustration [59], among other characteristics associated with the neurodevelopment of children living with ADHD, which should be considered in order to offer people a great experience.

- Capturing and maintaining attention. Engineers and researchers agree that one complex challenge when designing a cognitive training system is creating one capable of capturing and maintaining children’s attention in each cognitive training session [55,57]. The findings published in the literature suggest that children’s enjoyment and engagement decline across cognitive training sessions because exercises offered by those systems become routine and repetitive after several sessions [10].

- Long-term or longitudinal studies. Most systems reported in the literature indicate that they can be useful tools for diagnosing or treating ADHD, according to their objective (e.g., [18,23,25,27,51]). However, most systems have been tested with small groups of children (fewer than 20 participants). These studies are also characterized by considering few cognitive training or therapeutic sessions. Testing these systems on children living with ADHD is not a trivial problem. The first difficulty is related to recruiting children living with ADHD, and the second is associated with parents’ and children’s interest and perseverance in attending all sessions. According to Baxter et al. [60], only 5 out of 96 empirical studies in the human–robot interaction field consisted of more than a single session between 2013 and 2015. Therefore, long-term or longitudinal studies must be conducted to document changes over time, which can provide more reliable and accurate information about the efficacy of these systems focused on dealing with ADHD.

- Certification. The little evidence reported in the literature suggests that systems based on social robots or BCI video games with neurofeedback have great potential to improve the attention of children living with ADHD (e.g., [10,18,22,25,45]). Nowadays, few systems have been approved to be prescribed for treating children living with ADHD (e.g., [10,56]). Therefore, obtaining approval from a certification entity represents a challenge because all these systems are relatively new and most are currently in the design and prototyping phases.

- Avoiding physical harm. Some characteristics of robots can represent limitations and challenges for designing a safe human–robot interaction. Therefore, researchers and engineers should carefully choose the type of robot to use in a cognitive training system and define how these robots can interact with people involved in a cognitive training session to avoid potential physical harm. A good example of this issue can be observed in the system proposed by Cervantes et al. [20], called CogniDron-EEG. This system includes a drone. Therefore, using a drone implies avoiding physical interaction such as touching it. Even more, flying a drone at a reachable distance and in a small room can represent a potential issue of human–robot interaction if safety control mechanisms are not implemented appropriately.

- Making sure not to compromise social–emotional development. Few researchers are worried about how social robots can compromise children’s social–emotional development [61]. Children living with ADHD or other mental disorders can be more sensitive than regular children to socially affective bonding with a robot. According to Sandygulova et al. [24], there is a potential risk that individuals might develop strong emotional bonds with the robot, the severing of which at the end of therapy can have negative effects on individuals, such as a recoil in therapeutic benefits that the person might have achieved. However, there are few studies related to this ethical issue because, given the current state of this technology, it seems to be more urgent to address other ethical issues and challenges, such as privacy, safety, and the efficacy of these systems in dealing with ADHD.

6. Conclusions

The systematic review conducted in this paper allows us to know the current state of systems based on social robots and BCI video games for dealing with ADHD. We found 36 systems; 17 are based on social robots, 18 are based on BCI video games, and 1 is based on serious video games without including a BCI. According to the functionality of these systems, we have classified them into three types: systems for diagnosis, systems for cognitive training, and systems for studying the human brain. Of all the systems identified in the literature, we observed that 2 systems focused on supporting the diagnosis of ADHD in people, 32 systems focused on supporting cognitive or behavioral rehabilitation therapies, and 2 systems focused on supporting the study of brain areas of people living with ADHD. The results reported in the literature have shown the potential of these systems for supporting non-pharmacological treatments of people living with ADHD or detecting ADHD in people. However, the research community focused on these technologies agrees that more studies must be conducted in order to identify both the advantages and disadvantages of using these systems in real clinical environments. For instance, some studies have reported positive effects on children living with ADHD when they interact with these technologies. Some of these positive effects are a quick acceptance of technology, better engagement during therapy sessions, positive experiences using these novel technological systems, and relevant improvement in the cognitive functions of people who have been trained through these systems. Nevertheless, researchers have also found that a small group of children has had bad experiences or a kind of frustration when using these new technologies. These negative findings may indicate that not all people living with ADHD can be candidates for using these technologies. As a result of this review, we identified a set of critical challenges that developers must face when developing flexible systems that can be reconfigured and customized according to the characteristics of each individual, in order to offer the best experience to the patient. Finally, most systems reported in the literature are still developing and testing processes. We hope this study can help guide the development of future systems based on social robots or BCI video games for children living with ADHD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-A.C., S.L. and S.C.; methodology, J.-A.C., A.H. and H.D.; formal analysis, J.-A.C., S.L. and S.C.; investigation, J.-A.C., A.H. and H.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-A.C., A.H. and H.D.; writing—review and editing, J.-A.C., S.L. and S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from 36 papers published on PubMed, Engineering Village, IEEE Xplore, and Scopus, respectively.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for carefully reading our manuscript and for their insightful comments and suggestions. Also, Aribei Hernández and Heiler Duarte thank the Mexican National Council on Humanities Science and Technology (CONAHCyT) for supporting their graduate studies with scholarships 1143535 and 1111448, respectively.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hoogman, M.; Stolte, M.; Baas, M.; Kroesbergen, E. Creativity and ADHD: A review of behavioral studies, the effect of psy-chostimulants and neural underpinnings. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 119, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Weibman, D.; Halperin, J.M.; Li, X. A Review of Heterogeneity in Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabele, M.; Schröer, S.; Hußlein, S.; Hansen, C. An AR Sandbox as a Collaborative Multiplayer Rehabilitation Tool for Children with ADHD. In Proceedings of the Mensch und Computer 2019-Workshopband, Hamburg, Germany, 8–11 September 2019; pp. 600–605. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine, T.P.; Ben-David, I.; Bos, M. TDAH, financial distress, and suicide in adulthood: A population study. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, L.G. Diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in children vs. adults: What nurses should know. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 32, 890–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccleston, L.; Williams, J.; Knowles, S.; Soulsby, L. Adolescent experiences of living with a diagnosis of ADHD: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 2019, 24, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.R.; Katz, B.; Buschkuehl, M.; Jaeggi, S.M.; Shah, P. Exploring N-Back Cognitive Training for Children With ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2020, 24, 704–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knouse, L.E.; Fleming, A.P. Applying Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for ADHD to Emerging Adults. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2016, 23, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolraich, M.L.; Chan, E.; Froehlich, T.; Lynch, R.L.; Bax, A.; Redwine, S.T.; Hagan, J.F. ADHD Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines: A Historical Perspective. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20191682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, S.J.; Roodenrys, S.J.; Johnson, K.; Bonfield, R.; Bennett, S.J. Game-based combined cognitive and neurofeedback training using Focus Pocus reduces symptom severity in children with diagnosed AD/HD and subclinical AD/HD. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2017, 116, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravou, V.; Drigas, A. BCI-based games and ADHD. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e52410413942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmelkamp, P.M.; Meyerbröker, K. Virtual reality therapy in mental health. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 17, 495–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosto, C.; Hasegawa, T.; Mangina, E.; Chifari, A.; Treacy, R.; Merlo, G.; Chiazzese, G. Exploring the effect of an augmented reality literacy programme for reading and spelling difficulties for children diagnosed with ADHD. Virtual Real. 2021, 25, 879–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolón-Poza, M.; Berrezueta-Guzman, J.; Martín-Ruiz, M.L. Creation of an intelligent system to support the therapy process in children with ADHD. In Proceedings of the Conference on Information and Communication Technologies of Ecuador, Guayaquil, Ecuador, 25–27 November 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Berrezueta-Guzman, J.; Robles-Bykbaev, V.; Pau, I.; Pesantez-Aviles, F.; Martin-Ruiz, M.-L. Robotic Technologies in ADHD Care: Literature Review. IEEE Access 2021, 10, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levantini, V.; Muratori, P.; Inguaggiato, E.; Masi, G.; Milone, A.; Valente, E.; Billeci, L. EYES Are The Window to the Mind: Eye-Tracking Technology as a Novel Approach to Study Clinical Characteristics of ADHD. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, A.; Braw, Y.; Elbaum, T.; Wagner, M.; Rassovsky, Y. Eye tracking during a continuous performance test: Utility for as-sessing ADHD patients. J. Atten. Disord. 2022, 26, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhymbayeva, N.; Amirova, A.; Sandygulova, A. A Long-Term Engagement with a Social Robot for Autism Therapy. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, F.; Di Gregorio, M.; Monaco, C.; Sebillo, M.; Tortora, G.; Vitiello, G. Socially assistive robotics combined with artificial intelligence for ADHD. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 18th Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 9–12 January 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes, J.A.; López, S.; Molina, J.; López, F.; Perales-Tejeda, M.; Carmona-Frausto, J. CogniDron-EEG: A system based on a brain–computer interface and a drone for cognitive training. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2023, 78, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrezueta-Guzman, J.; Pau, I.; Martin-Ruiz, M.-L.; Máximo-Bocanegra, N. Assessment of a Robotic Assistant for Supporting Homework Activities of Children With ADHD. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 93450–93465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.G.; Poh, X.W.W.; Fung, S.S.D.; Guan, C.; Bautista, D.; Cheung, Y.B.; Zhang, H.; Yeo, S.N.; Krishnan, R.; Lee, T.S. A randomized controlled trial of a brain-computer interface based attention training program for ADHD. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, E.; Thanos, G.K.; Kanellos, T.; Doulgerakis, A.; Thomopoulos, S.C. Evaluating the relation between the EEG brain-waves and attention measures, and the children’s performance in REEFOCUS game designed for ADHD symptoms im-provement. In Proceedings of the Smart Biomedical and Physiological Sensor Technology XVI, SPIE, Baltimore, MD, USA, 14–18 April 2019; Volume 11020, pp. 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Sandygulova, A.; Zhexenova, Z.; Tleubayev, B.; Nurakhmetova, A.; Zhumabekova, D.; Assylgali, I.; Rzagaliyev, Y.; Zhakenova, A. Interaction design and methodology of robot-assisted therapy for children with severe ASD and ADHD. Paladyn J. Behav. Robot. 2019, 10, 330–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, A.; Kim, J.I.; Noh, H.J.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, H.-S.; Choi, M.-T.; Lee, K.; Seo, J.-H.; Lee, G.H.; Kang, S.-K. A Novel Robot-Assisted Kinematic Measure for Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Preliminary Study. Psychiatry Investig. 2021, 18, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tleubayev, B.; Zhexenova, Z.; Zhakenova, A.; Sandygulova, A. Robot-assisted therapy for children with ADHD and ASD: A pilot study. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Conference on Service Robotics Technologies, Beijing, China, 22–24 March 2019; pp. 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Krichmar, J.L.; Chou, T.-S. A Tactile Robot for Developmental Disorder Therapy. In Proceedings of the Technology, Mind, and Society, Association for Computing Machinery. Washington, DC, USA, 5–7 April 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, J.; Escobedo, L.; Tentori, M. A BCI video game using neurofeedback improves the attention of children with autism. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2021, 15, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alchalabi, A.E.; Shirmohammadi, S.; Eddin, A.N.; Elsharnouby, M. FOCUS: Detecting ADHD Patients by an EEG-Based Serious Game. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2018, 67, 1512–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis-Onofre, R.; Catalá-López, F.; Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C. How to properly use the PRISMA Statement. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.-T.; Yeom, J.; Shin, Y.; Park, I. Robot-Assisted ADHD Screening in Diagnostic Process. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2019, 95, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhymbayeva, N.; Seitkazina, N.; Turabayev, D.; Pak, A.; Sandygulova, A. A long-term study of robot-assisted therapy for children with severe autism and ADHD. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 2020 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Cambridge, UK, 23–26 March 2020; pp. 401–402. [Google Scholar]

- Mizumura, Y.; Ishibashi, K.; Yamada, S.; Takanishi, A.; Ishii, H. Mechanical design of a jumping and rolling spherical robot for children with developmental disorders. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Macau, China, 5–8 December 2017; pp. 1062–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Palsbo, S.E.; Hood-Szivek, P. Effect of Robotic-Assisted Three-Dimensional Repetitive Motion to Improve Hand Motor Function and Control in Children With Handwriting Deficits: A Nonrandomized Phase 2 Device Trial. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2012, 66, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridin, M.; Yaakobi, Y. Educational robot for children with ADHD/ADD. Archit. Des. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dağlarlı, E.; Dağlarlı, S.F.; Günel, G.Ö.; Köse, H. Improving human-robot interaction based on joint attention. Appl. Intell. 2017, 47, 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpaia, P.; Duraccio, L.; Moccaldi, N.; Rossi, S. Wearable brain–computer interface instrumentation for robot-based rehabili-tation by augmented reality. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 6362–6371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpaia, P.; Criscuolo, S.; De Benedetto, E.; Donato, N.; Duraccio, L. A Wearable AR-based BCI for Robot Control in ADHD Treatment: Preliminary Evaluation of Adherence to Therapy. In Proceedings of the 2021 15th International Conference on Advanced Technologies, Systems and Services in Telecommunications (TELSIKS), Nis, Serbia, 20–22 October 2021; pp. 321–324. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, F.; Yoshikawa, T.; Furuhashi, T.; Kanoh, M.; Nakamura, T. Effects of collaborative learning between education-al-support robots and children who potential symptoms of a development disability. In Proceedings of the 2016 Joint 8th International Conference on Soft Computing and Intelligent Systems (SCIS) and 17th International Symposium on Advanced Intelligent Systems (ISIS), Sapporo, Japan, 25–28 August 2016; pp. 266–270. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, O.; Hoffman, G.; Kopelman-Rubin, D.; Klomek, A.B.; Shitrit, N.; Amsalem, Y.; Shlomi, Y. KIP3: Robotic companion as an external cue to students with ADHD. In Proceedings of the TEI’16: Tenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 14–17 February 2016; pp. 621–626. [Google Scholar]

- Berrezueta-Guzman, J.; Pau, I.; Martin-Ruiz, M.-L.; Maximo-Bocanegra, N. Smart-Home Environment to Support Homework Activities for Children. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 160251–160267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagiadinou, M.; Plerou, A. Brain-Computer Interface Design and Neurofeedback Training in the Case of ADHD Rehabilitation. In GeNeDis 2018; Springer: Cham, Swziterland, 2020; pp. 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.U.G. Cognitive Skill Enhancement System Using Neuro-Feedback for ADHD Patients. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2021, 68, 2363–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, J.E.; Lopez, D.S.; Lopez, J.F.; Lopez, A. Design and creation of a BCI videogame to train sustained attention in children with ADHD. In Proceedings of the 2015 10th Computing Colombian Conference (10CCC), Bogota, Colombia, 21–25 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Puthusserypady, S. A 3D learning playground for potential attention training in ADHD: A brain computer interface approach. In Proceedings of the 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Milan, Italy, 25–29 August 2015; pp. 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, X.; Loo, B.R.Y.; Castellanos, F.X.; Liu, S.; Koh, H.L.; Poh, X.W.W.; Krishnan, R.; Fung, D.; Chee, M.W.; Guan, C. Brain-computer-interface-based intervention renormalizes brain functional network topology in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Guan, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Jiang, B. Brain computer interface based 3D game for attention training and reha-bilitation. In Proceedings of the 2011 6th IEEE Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications, Beijing, China, 21–23 June 2011; pp. 124–127. [Google Scholar]

- Rohani, D.A.; Sorensen, H.B.; Puthusserypady, S. Brain-computer interface using P300 and virtual reality: A gaming approach for treating ADHD. In Proceedings of the 2014 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Chicago, IL, USA, 26–30 August 2014; pp. 3606–3609. [Google Scholar]

- Nazari, M.A.; Berquin, P. Effect of electrical activity feedback on cognition. In Proceedings of the 2010 17th Iranian Conference of Biomedical Engineering (ICBME), Isfahan, Iran, 3–4 November 2010; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C.G.; Lee, T.-S.; Guan, C.; Fung, D.S.; Cheung, Y.B.; Teng, S.; Zhang, H.; Krishnan, K.R. Effectiveness of a brain-computer interface based programme for the treatment of ADHD: A pilot study. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2010, 43, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.; Kihl, T.; Park, S.; Kim, M.-J.; Chang, J. Fairy tale directed game-based training system for children with ADHD using BCI and motion sensing technologies. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2019, 38, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandon, D.Z.; Munoz, J.E.; Lopez, D.S.; Gallo, O.H. Influence of a BCI neurofeedback videogame in children with ADHD. Quantifying the brain activity through an EEG signal processing dedicated toolbox. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 11th Colombian Computing Conference (CCC), Popayan, Colombia, 27–30 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Umemoto, A.; Lukie, C.N.; Kerns, K.A.; Müller, U.; Holroyd, C.B. Impaired reward processing by anterior cingulate cortex in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 14, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bul, K.C.; Franken, I.H.; Van der Oord, S.; Kato, P.M.; Danckaerts, M.; Vreeke, L.J.; Willems, A.; Van Oers, H.J.; Van den Heuvel, R.; Van Slagmaat, R. Development and user satisfaction of “Plan-It Commander,” a serious game for children with ADHD. Games Health J. 2015, 4, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.P.; Vinod, A.; Guan, C. Enhancement of attention and cognitive skills using EEG based neurofeedback game. In Proceedings of the 2013 6th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering (NER), San Diego, CA, USA, 6–8 November 2013; pp. 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Canady, V.A. FDA approves first video game Rx treatment for children with ADHD. Ment. Health Wkly. 2020, 30, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, J.F.; Griffiths, K.R.; Korgaonkar, M.S. A Systematic Review of Imaging Studies in the Combined and Inattentive Subtypes of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, N.M.; Brown, S.N.; Briggs, R.D.; Germán, M.; Belamarich, P.F.; Oyeku, S.O. Associations Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and ADHD Diagnosis and Severity. Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 17, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, P.; Navas-Medrano, S.; Soler-Dominguez, J.L. Extended reality for mental health: Current trends and future challenges. Front. Comput. Sci. 2022, 4, 1034307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, P.; Kennedy, J.; Senft, E.; Lemaignan, S.; Belpaeme, T. From characterising three years of HRI to methodology and reporting recommendations. In Proceedings of the 2016 11th acm/ieee International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (hri), Christchurch, New Zealand, 7–10 March 2016; pp. 391–398. [Google Scholar]

- Smakman, M.H.; Konijn, E.A.; Vogt, P.A. Do Robotic Tutors Compromise the Social-Emotional Development of Children? Front. Robot. AI 2022, 9, 734955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).