Positive Psychology in Therapeutic Songwriting for People Living with Late-Life Depression—An Intervention Protocol

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

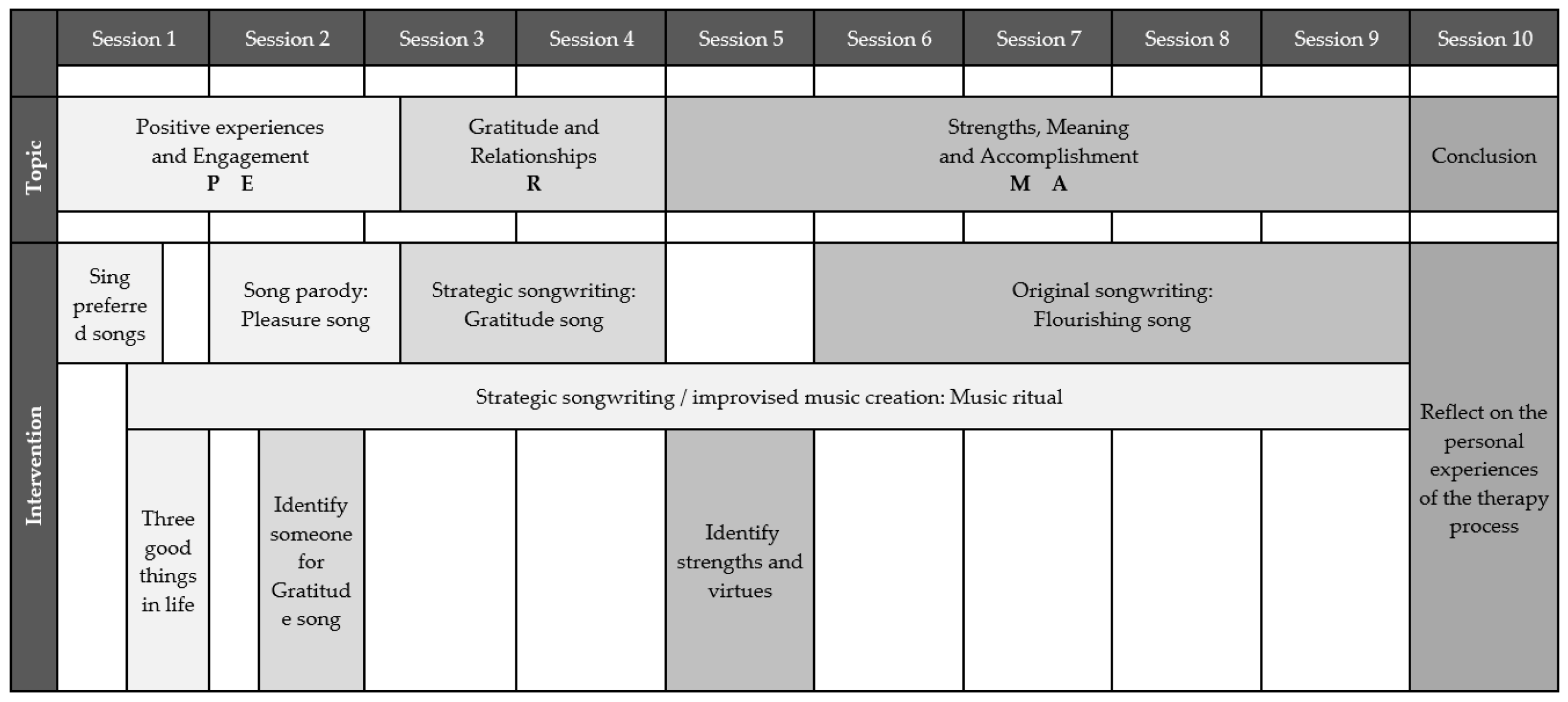

3.1. Overview

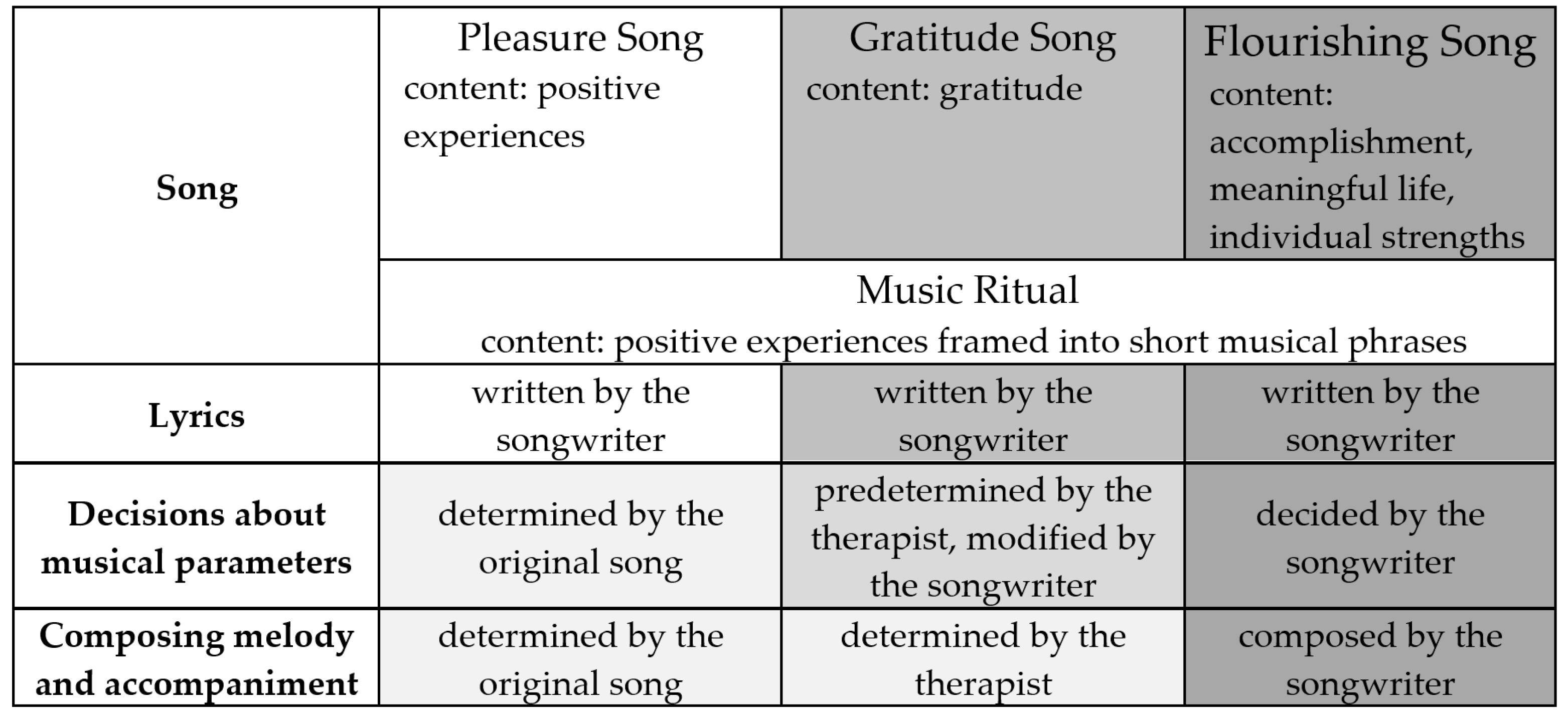

3.2. Part 1—Session 1–3 ‘Pleasure Song’

- Broaden perception (such as mental flexibility and creativity);

- Build resilience and social, intellectual, and emotional resources;

- Improve social engagement, relationships, interaction skills, and sense of belonging;

- Promote brain activation and autobiographic memories;

- Promote an awareness of self and one’s musical identity;

- Link music with positive emotions.

3.2.1. Music Ritual

3.2.2. ’Pleasure Song’

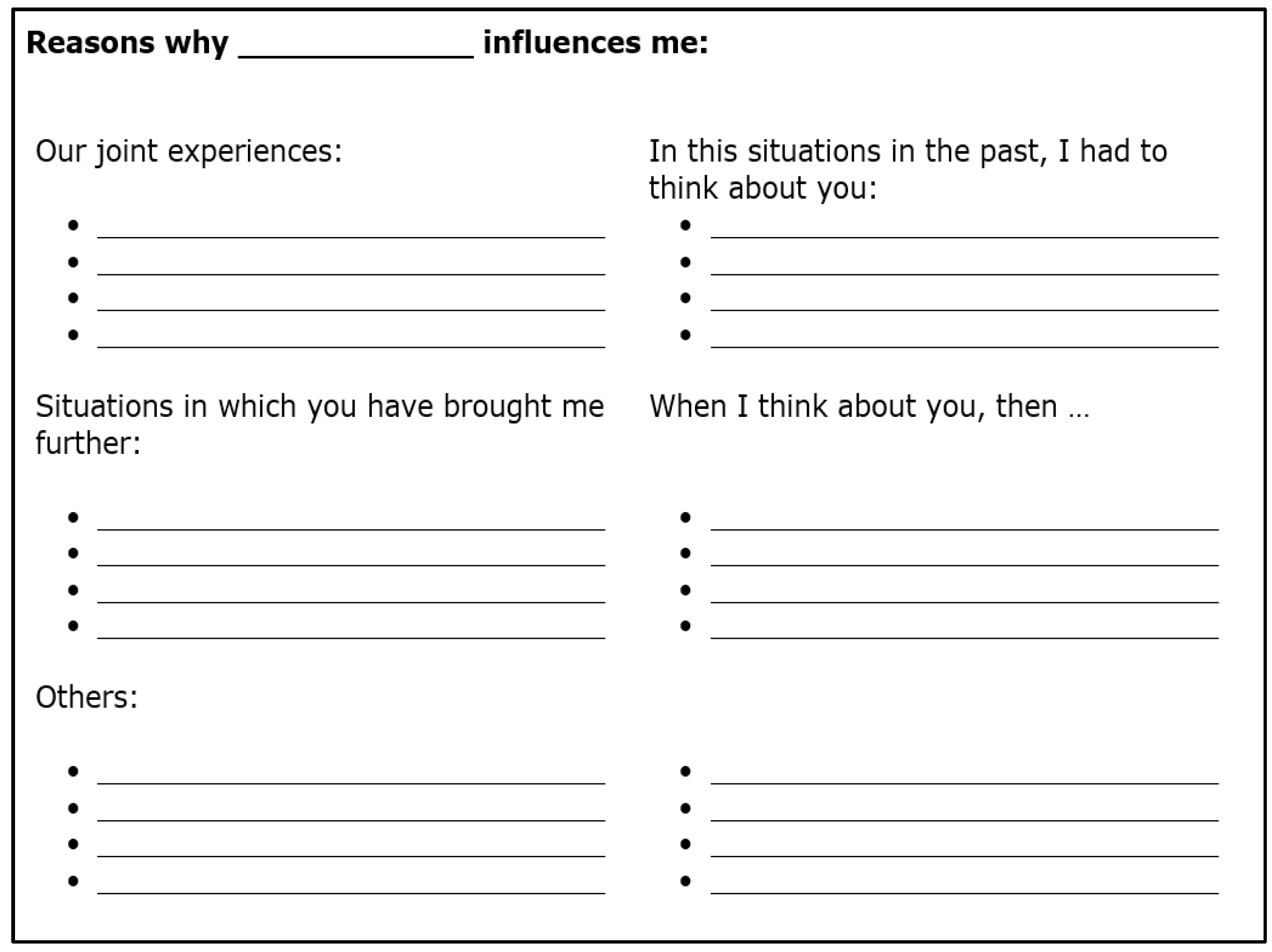

3.3. Part 2—Session 3–4 ‘Gratitude Song’

3.4. Part 3—Session 5–9 ‘Flourishing Song’

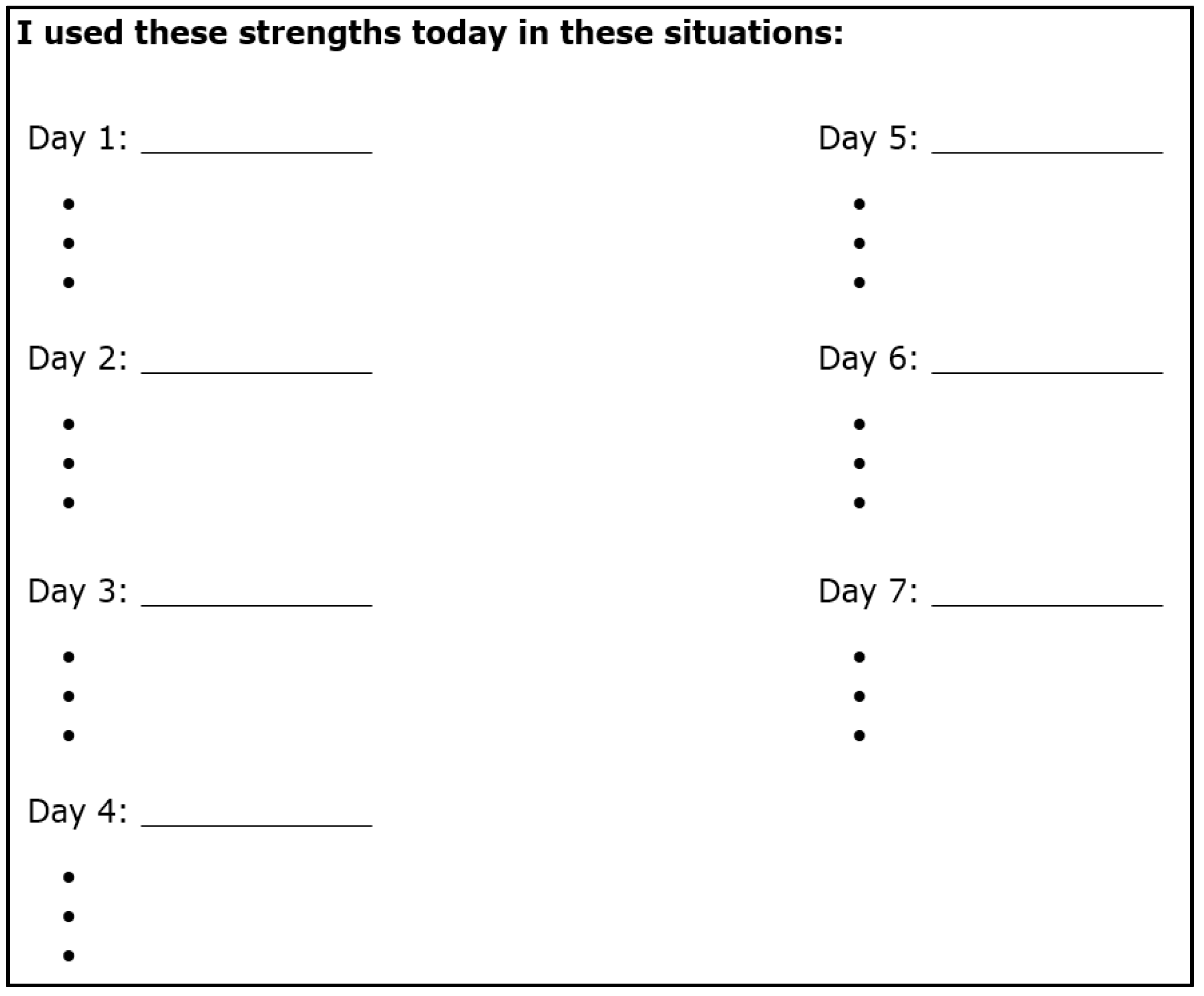

3.4.1. Identifying Strengths

3.4.2. ’Flourishing Song’

- Verse 1: what were the achievements in the songwriter’s past?

- Verse 2: what is meaningful for the songwriter in the past and present?

- Verse 3: what does the songwriter want to achieve in the future?

- Chorus (examples):

- ○

- Who is the songwriter and what are their signature strengths, traits, and attitudes?

- ○

- What does the songwriter want to leave to the persons around?

- ○

- What is a guiding slogan for the songwriter?

- ○

- What does the songwriter want to tell the people around them (e.g., memories or appeal)?

3.5. Conclusion Session

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

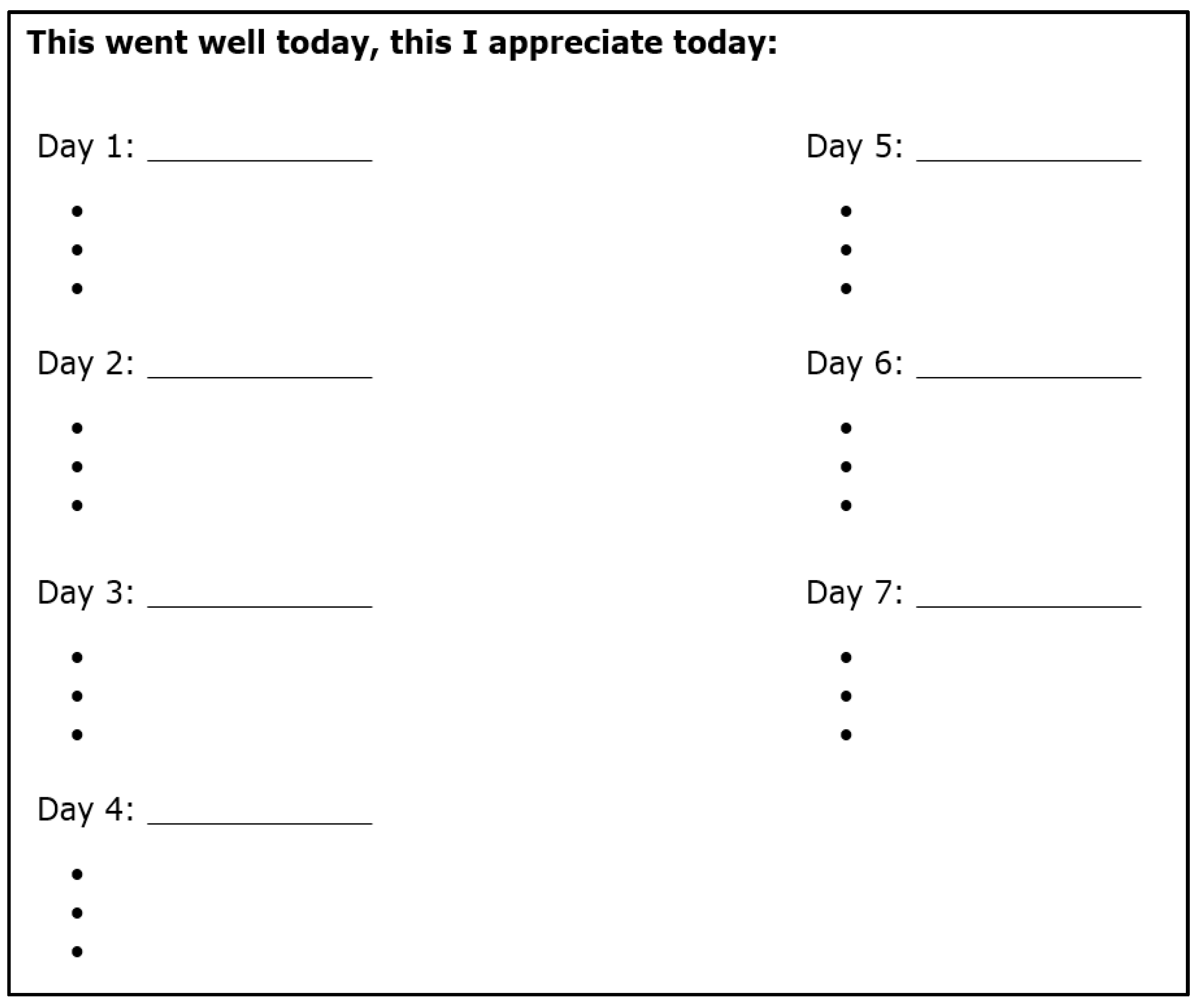

Appendix A

References

- Lavretsky, H. Intervention Research in Late-Life Depression: Challenges and Opportunities. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 24, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- McCall, W.V.; Kintziger, K.W. Late life depression: A global problem with few resources. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 36, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive Psychology: An Introduction; APA Americam Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ascenso, S.; Perkins, R.; Williamon, A. Resounding Meaning: A PERMA Wellbeing Profile of Classical Musicians. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma-Brymer, V.; Brymer, E. Flourishing and Eudaimonic Well-Being. In Good Health and Well-Being; Filho, W.L., Wall, T., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P.G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A New Understanding of Happiness, Well-Being—And How to Achieve Them; Nicholas Brealey Publishing: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bolier, L.; Haverman, M.; Westerhof, G.J.; Riper, H.; Smit, F.; Bohlmeijer, E. Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R.A.; McCullough, M.E. Counting Blessings Versus Burdens: An Experimental Investigation of Gratitude and Subjective Well-Being in Daily Life. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, J.F.; Schutte, N.S.; Byrne, B. The effect of positive writing on emotional intelligence and life satisfaction. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62, 1291–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieswijk, N.; Steverink, N.; Buunk, B.P.; Slaets, J.P. The effectiveness of a bibliotherapy in increasing the self-management ability of slightly to moderately frail older people. Patient Educ. Couns. 2006, 61, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremers, I.P.; Steverink, N.; Albersnagel, F.A.; Slaets, J.P.J. Improved self-management ability and well-being in older women after a short group intervention. Aging Ment. Health 2006, 10, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ho, H.C.Y.; Yeung, D.Y.; Kwok, S.Y.C.L. Development and evaluation of the positive psychology intervention for older adults. J. Posit. Psychol. 2014, 9, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proyer, R.T.; Gander, F.; Wellenzohn, S.; Ruch, W. Positive psychology interventions in people aged 50–79 years: Long-term effects of placebo-controlled online interventions on well-being and depression. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez, E.; Ortega, A.R.; Chamorro, A.; Colmenero, J.M. A Program of Positive Intervention in the Elderly: Memories, Gratitude and Forgiveness; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 463–470. [Google Scholar]

- Moral, J.C.M.; Terrero, F.B.F.; Galán, A.S.; Rodríguez, T.M. Effect of integrative reminiscence therapy on depression, well-being, integrity, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in older adults. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghvaienia, A.; Alamdari, N. Effect of Positive Psychotherapy on Psychological Well-Being, Happiness, Life Expectancy and Depression Among Retired Teachers with Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salces-Cubero, I.M.; Ramirez-Fernandez, E.; Ortega-Martinez, A.R. Strengths in older adults: Differential effect of savoring, gratitude and optimism on well-being. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.L.; Hanni, A.A. Effects of a Savoring Intervention on Resilience and Well-Being of Older Adults. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2019, 38, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, F.A. Therapeutic Songwriting: Developments in Theory, Methods, and Practice; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Eickholt, J. Musiktherapeutisches Songwriting. Musikther. Umsch. Forsch. Prax. Musikther. 2017, 38, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, F.A.; Rickard, N.; Tamplin, J.; Roddy, C. Flow and meaningfulness as mechanisms of change in self-concept and well-being following a songwriting intervention for people in the early phase of neurorehabilitation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, F.A.; Stretton-Smith, P.; Clark, I.N.; Tamplin, J.; Lee, Y.-E.C. A Group Therapeutic Songwriting Intervention for Family Caregivers of People Living with Dementia: A Feasibility Study with Thematic Analysis. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, I.N.; Stretton-Smith, P.A.; Baker, F.A.; Lee, Y.-E.C.; Tamplin, J. “It’s Feasible to Write a Song”: A Feasibility Study Examining Group Therapeutic Songwriting for People Living with Dementia and Their Family Caregivers. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettenberger, M.; Ardila, Y.M.B. Music therapy song writing with mothers of preterm babies in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)—A mixed-methods pilot study. Arts Psychother. 2018, 58, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Valverde, E.; Badia, M.; Orgaz, M.B.; Gónzalez-Ingelmo, E. The influence of songwriting on quality of life of family caregivers of people with dementia: An exploratory study. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2020, 29, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddy, C.; Rickard, N.; Tamplin, J.; Baker, F.A. Personal identity narratives of therapeutic songwriting participants following Spinal Cord Injury: A case series analysis. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2018, 41, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, M.J. Effects of Music Therapy on Change and Depression on Clients in Detoxification. J. Addict. Nurs. 2011, 22, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M.J. Effects of group songwriting on depression and quality of life in acute psychiatric inpatients: A randomized three group effectiveness study. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2013, 22, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M.J. Effects of educational music therapy on illness management knowledge and mood state in acute psychiatric inpatients: A randomized three group effectiveness study. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2016, 25, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: The New Medical Research Council Guidance; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 587–592. [Google Scholar]

- Schulkind, M.D.; Hennis, L.K.; Rubin, D.C. Music, emotion, and autobiographical memory: They’re playing your song. Mem. Cogn. 1999, 27, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, F.A.; Ballantyne, J. “You’ve got to accentuate the positive”: Group songwriting to promote a life of enjoyment, engagement and meaning in aging Australians. Nord. J. Music. Ther. 2013, 22, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Charpentier, A. Flow: Das Geheimnis des Glücks; Klett-Cotta: Stuttgart, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Steen, T.A.; Park, N.; Peterson, C. Positive Psychology Progress: Empirical Validation of Interventions. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruscia, K.E.; McShane, F.; Burnett, J. Defining Music Therapy; Barcelona Publishers: University Park, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, C.V.; Tomal, D.R.; Rajan, R.S. Songwriting: Strategies for Musical Self-Expression and Creativity; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tamplin, J.; Baker, F.A.; Macdonald, R.A.; Roddy, C.; Rickard, N.S. A theoretical framework and therapeutic songwriting protocol to promote integration of self-concept in people with acquired neurological injuries. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2016, 25, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruch, W.; Proyer, R.T.; Harzer, C.; Park, N.; Peterson, C.; Seligman, M.E. Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS): Adaptation and Validation of the German Version and the Development of a Peer-Rating Form; Hogrefe & Huber Publishers: Berne, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Roy, S. Critique of positive psychology and positive interventions. In The Routledge International Handbook of Critical Positive Psychology; Brown, N.J.L., Eiroa-Orosa, F.J., Lomas, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 142–160. [Google Scholar]

- Eickholt, J.; Geretsegger, M.; Gold, C. Perspectives on research and clinical practice in music therapy for older people with depression. In Arts Therapies in the Treatment of Depression; Zubala, A.K.V., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 227–240. [Google Scholar]

- Tantam, D. Is Positive Psychology Compatible with Freedom? In The Routledge International Handbook of Critical Positive Psychology; Brown, N.J.L., Eiroa-Orosa, F.J., Lomas, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P. Toward a Dual-Systems Model of What Makes Life Worth Living. In The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications; Wong, P.T.P., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Marecek, J.; Christopher, J.C. Is positive psychology an indigenous psychology? In The Routledge International Handbook of Critical Positive Psychology; Brown, N.J.L., Eiroa-Orosa, F.J., Lomas, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chakhssi, F.; Kraiss, J.T.; Sommers-Spijkerman, M.; Bohlmeijer, E.T. The effect of positive psychology interventions on well-being and distress in clinical samples with psychiatric or somatic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rubia Ortí, J.E.; García-Pardo, M.P.; Iranzo, C.C.; Madrigal, J.J.C.; Castillo, S.S.; Rochina, M.J.; Gascó, V.J. Does Music Therapy Improve Anxiety and Depression in Alzheimer’s Patients? J. Altern. Complementary Med. 2018, 24, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasemi, M.; Aazami, S.; Zabihi, R.E. The Effects of Music Therapy on Anxiety and Depression of Cancer Patients. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2016, 22, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Umbrello, M.; Sorrenti, T.; Mistraletti, G.; Formenti, P.; Chiumello, D.; Terzoni, S. Music therapy reduces stress and anxiety in critically ill patients: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Minerva Anestesiol. 2019, 85, 886–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Wisdom and Knowledge | Courage | Humanity |

| Creativity Curiosity Judgement/Critical thinking Love of learning Perspective | Bravery Perseverance Honesty Zest | Love Kindness Social Intelligence |

| Justice | Temperance | Transcendence |

| Teamwork Fairness Leadership | Forgiveness Humility Prudence Self-regulation | Appreciation of Beauty and Excellence Gratitude Hope Humor Spirituality |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eickholt, J.; Baker, F.A.; Clark, I.N. Positive Psychology in Therapeutic Songwriting for People Living with Late-Life Depression—An Intervention Protocol. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12050626

Eickholt J, Baker FA, Clark IN. Positive Psychology in Therapeutic Songwriting for People Living with Late-Life Depression—An Intervention Protocol. Brain Sciences. 2022; 12(5):626. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12050626

Chicago/Turabian StyleEickholt, Jasmin, Felicity A. Baker, and Imogen N. Clark. 2022. "Positive Psychology in Therapeutic Songwriting for People Living with Late-Life Depression—An Intervention Protocol" Brain Sciences 12, no. 5: 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12050626

APA StyleEickholt, J., Baker, F. A., & Clark, I. N. (2022). Positive Psychology in Therapeutic Songwriting for People Living with Late-Life Depression—An Intervention Protocol. Brain Sciences, 12(5), 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12050626