Abstract

Uveal melanoma represents the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults; it may arise in any part of the uveal tract, with choroid and ciliary bodies being the most frequent sites of disease. In the present paper we studied ABCB5 expression levels in patients affected by uveal melanoma, both with and without metastasis, in order to evaluate if ABCB5 is associated with a higher risk of metastatic disease and can be used as a poor prognostic factor in uveal melanoma. The target population consisted of 23 patients affected by uveal melanoma with metastasis and 32 without metastatic disease. A high expression of ABCB5 was seen in patients with metastasis (14/23, 60.9%), compared to that observed in patients without metastasis (13/32, 40.6%). In conclusion, we found that ABCB5 expression levels were correlated with faster metastatic progression and poorer prognosis, indicating their role as a prognostic factor in uveal melanoma.

1. Introduction

Uveal melanoma (UM) is a rare neoplasm which, despite its rarity, represents the most common primary ocular malignancy in adults; it develops more frequently from melanocytes of the choroid but can also arise in other sites, such as ciliary bodies and iris [1]. UM has rarely been reported in pediatric ages, especially in advanced stages, with extraocular extension [2,3].

Several risk factors have been proposed in the pathogenesis of UM, including the presence of choroidal nevus, exposure to ultraviolet radiation, clear phototypes, ocular melanocytosis and extraocular conditions such as cutaneous dysplastic nevus syndrome, nevus of Ota and type 1 neurofibromatosis [4].

Clinically, although UM may remain silent and be accidentally detected by routine ophthalmic screening, a retinal detachment, causing visual disturbances like photopsia, is the most common presenting symptom of the disease; intraocular infections, vitreous bleeding and secondary glaucoma are frequent complications characterizing the natural history of the neoplasm [5].

Histologically, three distinct histotypes of UM have been identified: epithelioid cells, spindle cells and mixed cell type; a greater proportion of epithelioid cells has traditionally been associated with poorer prognosis [6].

It has been demonstrated on the basis of cytogenetic studies that monosomy 3 is the most common chromosomal aberration in UMs and correlates with lower survival rates; other cytogenetic alterations including loss of 1p, 6q and gain of 6p and 8q have been also associated with UM [7].

The biological history of the neoplasm has been characterized in almost 50% of cases by hematogenous dissemination, with the onset of secondary disease localizations, especially at the liver. Despite the improvements in therapeutic strategies, no significant increase in survival has been obtained and liver metastases are expected within 10–15 years after the diagnosis in about half of patients [8].

ATP-binding cassette sub-family B member 5 (ABCB5) is a human transmembrane P-glycoprotein that plays an active role in transmembrane transport of several substances including chemotherapeutic drugs; therefore, it is physiologically involved in the development of chemoresistance of cancer cells [9,10,11]. An overexpression of ABCB5 has been found in tumor stem cells, of which it is therefore a full-fledged marker of several malignancies such as hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, cutaneous melanoma and Merkel cell carcinoma [12,13,14]. Furthermore, ABCB5 has been shown to be correlated with tumor growth and invasion [15,16].

Regarding cutaneous melanoma, ABCB5-positive malignant melanoma-initiating cells (MMICs) are believed to be involved both in the onset and in the progression of disease and ABCB5 has also been found to play a crucial role in promoting distant metastasis through the activation of the NF-kB signaling pathway [17].

In the present study, we retrospectively investigated ABCB5 expression in primary uveal melanoma in patients both with non-metastatic and metastatic disease and we evaluated its potential role as a prognostic marker and predictive factor of metastatic potential of the neoplastic cells.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis of clinical data and histologic specimens of all cases of uveal melanoma treated by enucleation at the Eye Clinic of the University of Catania, during the eight years until to October 2017, was performed. Tumors not suitable for radiotherapy, such as plaque brachytherapy or proton beam radiotherapy were subjected to enucleation. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue specimens were obtained from the surgical pathology archive at the Section of Anatomic Pathology, Department G.F. Ingrassia, University of Catania. Cases in which paraffin blocks containing the tumor could not be used to obtain additional slides for immunohistochemical evaluation, representative tumor tissue was not present, the tumor was totally necrotic or had been treated previously, were excluded from the study. At least five sections were obtained from paraffin-embedded tissue specimens. Because of the retrospective nature of the study, no written informed consent from patients was obtained. The research protocols were approved by the Local Medical Ethics Committee (University of Catania) and conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. 23 UMs with metastasis and 32 UMs without metastasis were part of the study. The following clinical data were collected: tumor size and location, evaluated through ophthalmoscopy and A and B scan ultrasonography, and presence of metastasis, investigated with standard methods such as physical examination, liver ultrasound and total body computed tomography. The A-scan ultrasound refers to a mono-dimensional amplitude modulation scan, mainly used in common sight disorders because it provides important data on the axial length of the eye; the other major use of the A-scan is to determine the size and ultrasound characteristics of intraocular masses. B-scan ultrasound is a two-dimensional, cross-section brightness scan, that, when used in conjunction with A-scan imaging, allows direct visualization of the lesion, including anatomic location, shape, borders, and size, thereby ensuring a more detailed preoperative diagnosis. All histological sections were evaluated by two pathologists (GB and RC) in order to get the most objective assessment possible.

2.1. Immunohistochemistry

Sections were processed as previously described [18,19]. Briefly, the slides were dewaxed in xylene, hydrated using graded ethanols and incubated for 30 min in 0.3% H2O2/methanol to quench endogenous peroxidase activity, then rinsed for 20 min with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Bio-Optica, Milan, Italy). The sections were heated (5 min × 3) in capped polypropylene slide-holders with citrate buffer (10 mM citric acid, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6.0; Bio-Optica, Milan, Italy), using a microwave oven (750 W) to unmask antigenic sites. To reduce the commonly seen non-specific immunoreactivity due to endogenous biotin, sections were pretreated with 10 mg/mL of ovalbumin in PBS followed by 0.2% biotin in PBS, each for 15 min at room temperature. Then, the sections were incubated for 18 h at 4 °C with mouse monoclonal anti-ABCB5 antibody (ab140667; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), diluted 1:100 in PBS (Sigma, Milan, Italy). The secondary biotinylated anti-mouse antibody was applied for 30 min at room temperature, followed by the avidin–biotin–peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for a further 30 min at room temperature. The immunoreaction was visualized by incubating the sections for 4 min in a 0.1% 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and 0.02% hydrogen peroxide solution (DAB substrate kit, Vector Laboratories, CA, USA). The sections were lightly counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Histolab Products AB, Göteborg, Sweden) mounted in GVA mountant (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA, USA) and observed with a Zeiss Axioplan light microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

2.2. Evaluation of Immunohistochemistry

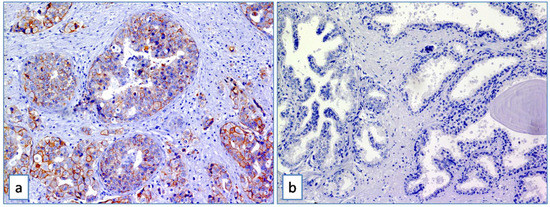

Immunostained histologic sections were separately evaluated by two pathologists (GB and RC), with no information on clinical data. Immunohistochemical positive ABCB5 staining was defined as the presence of brown chromogen detection in the cell membrane. Liver cancer and breast cancer tissues (Figure 1a) were used as positive controls to test the validity of the antibody reaction. Negative controls, involving benign prostatic tissue, were included (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) ABCB5 staining on breast cancer tissue used as positive control (Immunoperoxidase stain; original magnification 150×); (b) absence of expression of ABCB5 in benign prostatic tissue used as negative control (Immunoperoxidase stain; original magnification 150×).

Stain intensity and proportion of immunopositive cells were assessed by light microscopy, as previously described [18]. Intensity of staining (IS) was graded on a scale of 0–3, according to the following assessment: no detectable staining = 0, weak staining = 1, moderate staining = 2, strong staining = 3. The percentage of ABCB5 immunopositive cells (Extent Score, ES) was scored in five categories: <5% (0); 5–30% (+); 31–50% (++); 51–75% (+++), and >75% (++++). Counting was performed at 200× magnification. Staining intensity was multiplied by the percentage of positive cells to obtain the intensity reactivity score (IRS); IRS < 6 was considered as low expression (L-IRS), IRS > 6 was considered as high expression (H-IRS).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Non parametric comparison of the rate of high and low levels of ABC5 expression in melanoma of patients with and without metastasis was performed by chi-square test. Agreement among observers was tested by Cohen K.

Univariate and multivariate analysis were based on a Cox proportional hazards regression model (time free from metastasis as outcome); this model included gender, age, melanoma location (choroid or ciliary body), temporal or nasal location, cells type (epithelioid, spindle cells or mixed), echographic parameters (height, greatest diameter), ABCB5 expression (low and high). All predictors that had a p-value < 0.15 (cut off) in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. Survival analysis according to ABC5 expression levels (high and low) was performed by Kaplan-Meyer test; survival rates were compared by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. p-values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Clinico-Pathological Characteristic of Uveal Melanomas

The study was conducted on of 55 patients, 28 of whom were males and 27 women; median age was 67 years (range 29–85). 40 melanomas were localized only in the choroid, while 15 affected both choroid and ciliary body; extrascleral involvement was present and histologically confirmed in only one case. Regarding the histotypes, 15 cases were classified as epithelioid cells, 12 as spindle cells, while 28 cases were diagnosed as mixed type UM with both epithelioid and spindle cells. Considering the “TNM classification of malignant tumours”, pathological T stage was: pT1a in 7 patients, pT1b in 1 patient, pT2a in 21 patients, pT2b in 8 patients, pT2d in 1 patient, pT3a in 8 patients, pT3b in 5 patients, pT4a in 1 patient and pT4b in 3 patients. Liver metastasis were present in 23 patients. Median follow-up period was 60 months (range 12–138 months).

Out of 32 patients without metastatic disease, 17 were males and 15 females; the median age was 64 years (range 29–84). Considering 23 patients with metastatic localization of primary UM, 11 were males and 12 females; median age was 72 (range 50–85). 13 of 23 patients died during the follow-up period for disease progression (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographics, tumor parameters, disease free time, follow-up and ABCB5 expression in primary uveal melanoma without metastasis (n = 32).

Table 2.

Demographics, tumor parameters, disease free time, follow-up and ABCB5 expression in primary uveal melanoma with metastasis (n = 23).

Comparing patients without metastasis and those with metastasis, no significant difference was seen in median age, location of the melanoma (choroid or choroid/ciliary body), tumor thickness, cell type, extrascleral extension, pathological pT stage; patients who developed metastasis had melanoma with greater median largest diameter (15.6 mm vs 11.9 mm, p = 0.007), and higher median ABCB5 expression (9 vs 3, p = 0.030); they had lower median disease free survival (25 months vs 81 months, p < 0.001). (Table 3)

Table 3.

Median (range) of demographics, tumour parameters, disease free time, follow-up, ABCB5 expression in primary uveal melanoma without and with systemic metastasis.

3.2. Correlations between ABCB5 Expression and Clinico-Pathological Factors in Uveal Melanomas

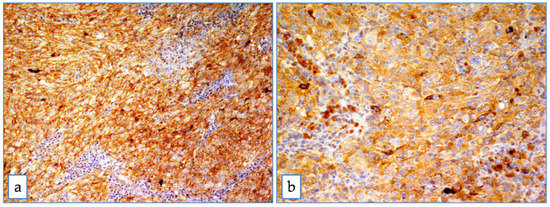

In the whole group (n = 55) the median ABCB5 value was 4. ABCB5 expression was high in 27 (49.1%) melanomas (Figure 2), and low in 28 (50.9%) melanomas (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

ABCB5 in uveal melanoma. Strong and diffuse cytoplasmic positivity in mixed cell type uveal melanoma at medium (a) and high magnification (b) (Immunoperoxidase stain; original magnification 100× (a) and 200× (b)).

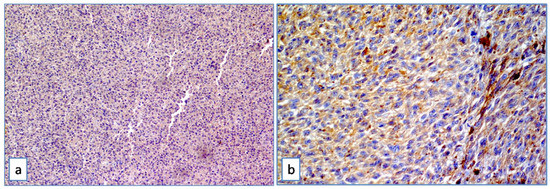

Figure 3.

ABCB5 in uveal melanoma. Mild and heterogeneous cytoplasmic positivity in mixed cell type uveal melanoma at medium (a) and high magnification (b) (Immunoperoxidase stain; original magnification 100× (a) and 200× (b)).

In 32 primary uveal melanomas without metastasis, ABCB5 IS was strong/moderate in 14 cases (43.7%) and weak in 10 cases (31.3%). 8 cases (25%) were totally negative; ES was >50% in 14 cases (43.7%), variable between 5–30% in 10 cases (31.3%). Only 13/32 cases (40.6%) showed H-IRS, while the remaining 19 cases showed L-IRS (59.4%) (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.026, Table 4). In 23 primary uveal melanomas with metastasis, ABCB5 IS was strong/moderate in 15 cases (65.2%) and weak in 7 cases (30.5%). Only 1 case (4.3%) was completely negative. ES was >75% in 3 cases (13.1%), >50% in 11 cases (47.8%), 30–50% in 7 cases (30.5%), <30% in 1 case (4.3%); lack of expression of ABCB5 was observed in only 1 case (4.3%). 14/23 cases (60.9%) showed H-IRS, while only 9 cases (39.1%) had L-IRS (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.026, Table 4).

Table 4.

Number of uveal melanoma (with and without metastasis) with low and high ABCB5.

Factors related to the presence of metastasis at univariate analysis on a Cox proportional hazards regression model were: age (p = 0.053), tumor greater diameter (p = 0.009), pT stage (p = 0.016), epithelioid cell type (p = 0.011) and ABCB5 expression (p = 0.047); at multivariate analysis tumor greater diameter (p = 0.010), ABCB5 expression (p = 0.003) and epithelioid cell type (p = 0.026) were significant.

No correlation was found between the histological type and ABCB5 expression (Spearman’s rho p = 0.334).

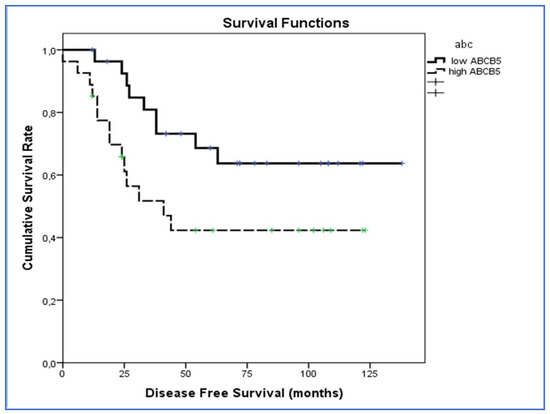

Figure 4 shows the results of Kaplan-Meier survival analyses in patients with uveal melanomas with low and high ABCB5 expression. The estimated survival times free from metastasis (SE, with 95% CI) were respectively: 101.1 (10.0) (CI: 81.6 to 120.7) and 64.4(10.5) (CI: 43.9 to 85.0).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival analyses in patients with uveal melanomas with low and high ABCB5 expression. The log-rank test showed a significant difference (p = 0.039) between the two groups in ABCB5 expression.

The log-rank test showed a significant difference (p = 0.039) between the two groups in ABCB5 expression.

4. Discussion

UM is a rare neoplasm with an “indolent” but slowly progressive biological behavior, characterized by the onset of liver metastasis within 10–15 years after diagnosis in about 50% of patients and a high rate of mortality [8]. Although in the last years several improvements have been recorded in the conservative management of UM with the aim of preserving the visual function [20], recurrence of disease and metastasis are still frequent events in the natural history of this neoplasm. Therefore, the study of molecular alterations in UM is currently of great scientific interest aiming at identifying possible biological factors capable of predicting a more aggressive biological behavior of the disease.

Histopathological factor of poor prognosis such as epithelioid cell type, tumor size, mitotic index, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), extrascleral invasion, vascular pattern and necrosis, and clinical risk factor (male sex and older age of the patient) are not very accurate in identifying a high-risk prognostic category of patients.

Cytogenetic studies demonstrated that patients with disomy 3 have a lower risk of developing metastasis; instead, the loss of heterozygosis of chromosome 3 was associated with a high rate of metastatic disease and poorer prognosis in UM: in particular, Prescher et al. [21] evaluated 30 patients with UM in association with monosomy 3 and 24 patients with disomy 3, and reported that 50% of patients with monosomy 3 showed metastasis within 3 years, whereas no metastatic disease was noted in those with disomy 3. In recent years, inactivating mutations of BRCA1 associated protein-1 (BAP-1), confirmed by lower nuclear immunohistochemical expression, have been found and reported in literature as poor prognostic factors [22,23]; moreover, high levels of expression of nestin, a member of the intermediate filament protein family, seem to correlate with metastatic progression and reduced survival rate in UM [24]. We previously evaluated the expression of ADAM10, RKIP and pRKIP [19,25], demonstrating their role as negative prognostic markers: in particular, regarding ADAM10 expression, high levels were found in 11/13 patients with metastatic UM and in only 15/39 patients without metastasis, and the difference was statistically significative [19].

As previously said, ABCB5 is a marker of cancer stem cells and is implicated in the tumorigenesis and tumor growth of several neoplasms, such as cutaneous melanoma, breast cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Particularly, Wang et al. [17] found that in vitro ABCB5-negative melanoma cell sub-population displayed a reduction in cell migration and invasion compared to the ABCB5-positive one; this finding was also confirmed at the transwell assays: lentivirus-mediated knockdown of ABCB5 in two different melanoma cell cultures induced a decline of cell migration and invasion. NF-kB signaling pathway has been discovered to be involved in this process: ABCB5 activates the NF-kB pathway by inhibiting p65 ubiquitination to enhance p65 protein stability, resulting in an accumulation of p65 in ABCB5-positive MMICs [17]. Among the traditional NF-kB targeting genes, MMP9 is involved in tumor cells invasion and metastasis [26]: an overexpression of MMP9, induced by ABCB5, seems to be one of the most important steps in the stimulation of metastatic potential of cutaneous melanoma [17]. In this paper, we first tested ABCB5 as prognostic factor in UM and observed that higher immunohistochemical levels of ABCB5 correlated to higher risk of metastasis. In our study, the median value of ABCB5 was 4 (moderate staining in more than 75% of neoplastic cells, or severe staining in more than 50% of neoplastic cells). Higher risk of metastasis was observed in UMs with higher expression of ABCB5 and lower metastatic risk in UMs with lower expression of the antibody. According to Kaplan-Meier survival analyses, lower survival times free from metastasis were seen in patients with UM and high expression of ABCB5.

In conclusion, we suggest using ABCB5 as an easily detectable prognostic marker in primary UMs and advocate its use as a predictor of the risk of liver metastasis and as guide for monitoring and treatment. In fact, ABCB5 levels expressed in UM biopsies could be a useful guide towards better treatment between enucleation and more conservative method.

The weakness of the present study was to evaluate only the morphological evidence based on immunohistochemistry, to investigate the expression of ABCB5 as a potential prognostic factor in uveal melanoma. Further studies are needed to confirm our morphological data with other relevant and sensitive techniques, such as quantitative RT-PCR, ELISA (or similar), and/or western blot.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.B. and R.C.; Data curation, A.R., M.R. and A.L.; Investigation, M.R.; Methodology, G.M., L.P. and R.C.; Software, G.M.; Writing—original draft, G.B.; Writing—review& editing, G.B. and R.C.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mahendraraj, K.; Lau, C.S.; Lee, I.; Chamberlain, R.S. Trends in incidence, survival, and management of uveal melanoma: A population-based study of 7516 patients from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database (1973–2012). Clin. Ophthalmol. 2016, 10, 2113–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pukrushpan, P.; Tulvatana, W.; Pittayapongpat, R. Congenital uveal malignant melanoma. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2014, 18, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, M.E.; Shaikh, A.H.; Corrêa, Z.M.; Augsburger, J.J. Primary uveal melanoma in a 4-year-old black child. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2013, 17, 551–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krantz, B.A.; Dave, N.; Komatsubara, K.M.; Marr, B.P.; Carvajal, R.D. Uveal melanoma: Epidemiology, etiology, and treatment of primary disease. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 11, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskelin, S.; Kivelä, T. Mode of presentation and time to treatment of uveal melanoma in Finland. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 86, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griewank, K.G.; van de Nes, J.; Schilling, B.; Moll, I.; Sucker, A.; Kakavand, H.; Haydu, L.E.; Asher, M.; Zimmer, L.; Hillen, U.; et al. Genetic and clinico-pathologic analysis of metastatic uveal melanoma. Mod. Pathol. 2014, 27, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, P.; Mihajlovic, M.; Djordjevic-Jocic, J.; Vlajkovic, S.; Cekic, S.; Stefanovic, V. Ocular melanoma: An overview of the current status. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2013, 6, 1230–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay, C.; Kim, D.W.; Gombos, D.S.; Oba, J.; Qin, Y.; Williams, M.D.; Esmaeli, B.; Grimm, E.A.; Wargo, J.A.; Woodman, S.E.; et al. Uveal melanoma: From diagnosis to treatment and the science in between. Cancer 2016, 122, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, N.Y.; Margaryan, A.; Huang, Y.; Schatton, T.; Waaga-Gasser, A.M.; Gasser, M.; Sayegh, M.H.; Sadee, W.; Frank, M.H. ABCB5-mediated doxorubicin transport chemoresistance in human malignant melanoma. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 4320–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.T.; Cheung, P.F.; Cheng, C.K.; Wong, N.C.; Fan, S.T. Granulin-epithelin precursor and ATP-dependent binding cassette (ABC)B5 regulate liver cancer cell chemoresistance. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.J.; Schatton, T.; Zhan, Q.; Gasser, M.; Ma, J.; Saab, K.R.; Schanche, R.; Waaga-Gasser, A.M.; Gold, J.S.; Huang, Q.; et al. ABCB5 identifies a therapy-refractory tumor cell population in colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 5307–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleffel, S.; Lee, N.; Lezcano, C.; Wilson, B.J.; Sobolewski, K.; Saab, K.R.; Mueller, H.; Zhan, Q.; Posch, C.; Elco, C.P.; et al. ABCB5-targeted chemoresistance reversal inhibits merkel cell carcinoma growth. J. Invest Dermatol. 2016, 136, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.J.; Saab, K.R.; Ma, J.; Schatton, T.; Pütz, P.; Zhan, Q.; Murphy, G.F.; Gasser, M.; Waaga-Gasser, A.M.; Frank, N.Y.; et al. ABCB5 maintains melanoma-initiating cells through a proinflammatory cytokine signaling circuit. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 4196–4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, P.F.; Cheung, T.T.; Yip, C.W.; Ng, L.W.; Fung, S.W.; Lo, C.M.; Fan, S.T.; Cheung, S.T. Hepatic cancer stem cell marker granulin-epithelin precursor and β-catenin expression associate with recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 21644–21657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Yao, X.; Tian, T.; Fu, X.; Wang, W.; Li, S.; Shi, T.; Suo, A.; Ruan, Z.; Guo, H.; et al. ABCB5-ZEB1 axis promotes invasion and metastasis in breast cancer cells. Oncol. Res. 2017, 25, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Grimmig, T.; Gonzalez, G.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Berg, G.; Carr, N.; Wilson, B.J.; Banerjee, P.; Ma, J.; Gold, J.S.; et al. ATP-binding cassette member B5 (ABCB5) promotes tumor cell invasiveness in human colorectal cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 11166–11178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tang, L.; Lin, J.; Shen, Z.; Yao, Y.; Wang, W.; Tao, S.; Gu, C.; Ma, J.; Xie, Y.; et al. ABCB5 promotes melanoma metastasis through enhancing NF-κB p65 protein stability. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 492, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardi, R.; Loreto, C.; Talic, N.; Caltabiano, R.; Musumeci, G. Immunolocalization of lubricin in the rat periodontal ligament during experimental tooth movement. Acta Histochem. 2012, 114, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caltabiano, R.; Puzzo, L.; Barresi, V.; Ieni, A.; Loreto, C.; Musumeci, G.; Castrogiovanni, P.; Ragusa, M.; Foti, P.; Russo, A.; et al. ADAM 10 expression in primaryuveal melanoma asprognostic factor for risk of metastasis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2016, 212, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.R.; Odashiro, A.N.; Lim, L.A.; Miyamoto, C.; Blanco, P.L.; Odashiro, M.; Maloney, S.; de Souza, D.F.; Burnier, M.N., Jr. Current and emerging treatment options for uveal melanoma. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2013, 7, 1669–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescher, G.; Bornfeld, N.; Hirche, H.; Horsthemke, B.; Jöckel, K.H.; Becher, R. Prognostic implications of monosomy 3 in uveal melanoma. Lancet 1996, 347, 1222–1225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harbour, J.W.; Onken, M.D.; Roberson, E.D.; Duan, S.; Cao, L.; Worley, L.A.; Council, M.L.; Matatall, K.A.; Helms, C.; Bowcock, A.M. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science 2010, 330, 1410–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szalai, E.; Wells, J.R.; Ward, L.; Grossniklaus, H.E. Uveal melanoma nuclear BRCA1-associated protein-1 immunoreactivity is an indicator of metastasis. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djirackor, L.; Shakir, D.; Kalirai, H.; Petrovski, G.; Coupland, S.E. Nestin expression in primary and metastatic uveal melanoma—Possible biomarker for high risk uveal melanoma. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018, 96, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caltabiano, R.; Puzzo, L.; Barresi, V.; Cardile, V.; Loreto, C.; Ragusa, M.; Russo, A.; Reibaldi, M.; Longo, A. Expression of raf kinase inhibitor protein (RKIP) is a predictor of uveal melanoma metastasis. Histol. Histopathol. 2014, 29, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kessenbrock, K.; Plaks, V.; Werb, Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: Regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell 2010, 141, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).