Designing a Waterless Toilet Prototype for Reusable Energy Using a User-Centered Approach and Interviews

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background: Water Scarcity

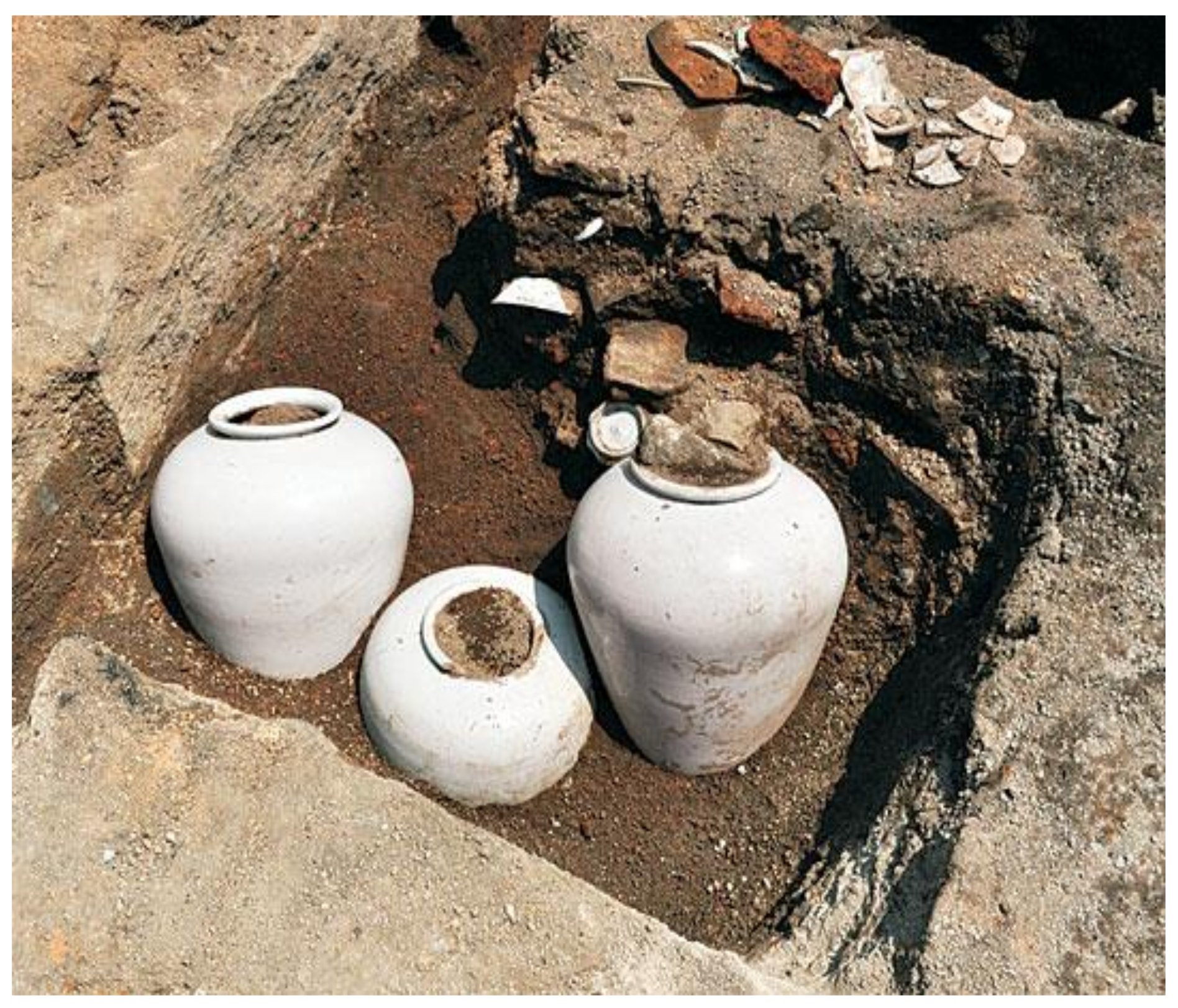

3. Waterless Toilet

4. User-Centered Research Approach

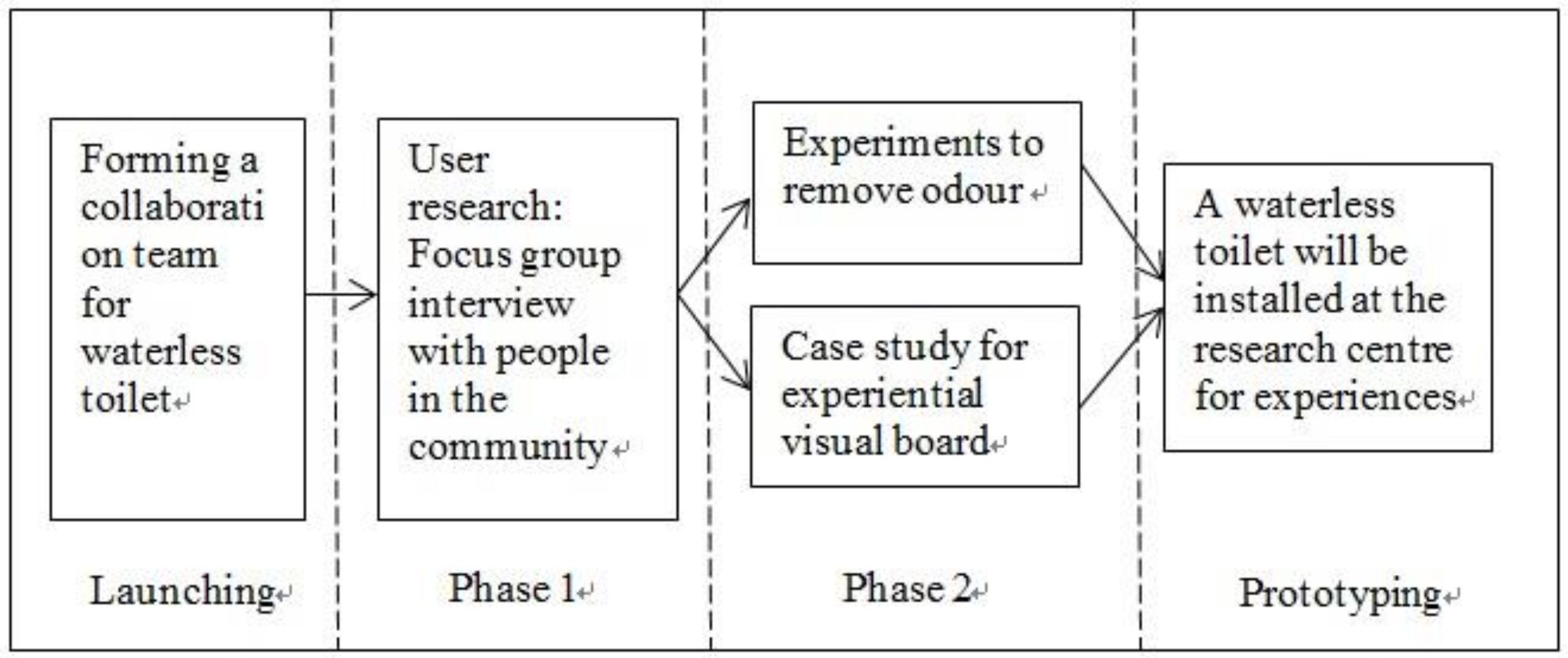

4.1. The FFE Process

4.1.1. Phase 1: Focus Group Interviews

Sampling Criteria

Process

Results

- (1)

- Disbelief about water scarcity: Everyone had heard that the Republic of Korea lacked water since they were children. However, most did not think that this was true, since the water quality in Korea is good and since they could access sufficient water to meet their needs anytime and anywhere. One individual thought that the push to save water (i.e., the many water-saving media campaigns) was propaganda. Only a few people had actually tried to save water through such methods as “using a cup to brush their teeth,” “filling a water basin to wash their faces,” or, in the case of one individual, “putting a plastic bottle in the toilet water tank to flush less water.”

- (2)

- Motivation for saving water: Most participants said that they had not attempted to try to save water because they did not believe that the Republic of Korea was truly suffering from water scarcity. The participants had no direct experiences of water scarcity, and most mentioned that, since their water bills were not expensive, they were not aware of how much water they used each day. They were from a demographic that was less likely to experience shortage or poor quality of water. As possible motivators to save water, the participants recommended water usage indicators or visual indicators of water consumption. They also suggested that more media exposure would be helpful in raising awareness of water scarcity. Lastly, they commented that financial losses would motivate them to save water. Some participants wanted tax deductions for saving water.

- (3)

- Experience requirement for the waterless toilet: This theme emerged from the two questions about the participants’ perceptions about a waterless toilet and their dream toilets. None of the participants had previously thought about their dream toilet. However, they said that they wanted a new toilet based on their public and private toilet experiences: visual cleanness, sanitariness (including automatic cleaning around the inside of the bowl), automatic flushing after usage, no bad odor, soundproofing within a public toilet, and a comfortably warm seat cover. Since the participants had not previously considered the water scarcity problem, they explained ways in which they would improve the current style of toilet. They also said that they would try a waterless toilet if they came across it in a public restroom. Most asked for simple visual guidance on how to use a waterless toilet, which is designed to suck up feces like a “vacuum cleaner” and send it directly to the energy production system. It requires about half liters of water, which is significantly less than what a regular toilet consumes.

4.1.2. Phase 2: Case Studies for Service Design Guideline

Criteria

- (1)

- Redesigning an apartment energy bill (http://www.slideshare.net/sdnight/ss-30524771). This case concerned one of the first service designs for a utility service in Korea. It was conducted on an apartment town comprising 600 apartments in Bangbae Dong, Seoul, and its results were highly effective, reducing the total energy bills by 10%. Many redesigning projects graphically change a certain part of an energy bill; however, in this case, the designers and design researchers reduced the energy bill based on in-depth interviews with the community. This case study prompted other apartment towns to accept similar guidelines.

- (2)

- National Health Insurance Service (http://www.slideshare.net/usableweb/ss-16567992?related=1). This case involved redesigning a health check-up chart for the National Health Insurance Service at Ilsan, Myungji Hospital. The chart had been criticized for being difficult to read by people who were not medical doctors from specific areas. In other words, doctors in one medical center often struggled to understand examinations conducted in other medical centers. The redesigned check-up chart received a 95% satisfaction rating.

- (3)

- Changwon National Industrial complex. As foreign labor for industrial complexes has increased, many industrial safety accidents have occurred. To reduce safety accidents, which can also waste energy resources (e.g., in cases of hydrofluoric acid leaks), a user-centered approach was employed. The service design involved changing signage and installing pictograms for international laborers. This case was published online (http://economy.hankooki.com/lpage/industry/201504/e20150406173204120170.htm).

Process

Case Study Results

- (1)

- Easy readability. Most people were interested in their health conditions or how much they were charged on their utility bill. However, previous bills had been designed with small font sizes and logos or advertisements. Based on user interviews, both bills were redesigned to use larger fonts and exclude or deemphasize less important information.

- (2)

- Vivid color for nudging. Both the apartment bill case and the industrial complex case used a vivid red color for warnings. If an individual used more energy than that used by the average household nationwide, he or she received a red-colored bill that was visible to every neighbor. If an individual used less energy than the national average, he or she received a green-colored bill. Average utility usage generated a yellow-colored bill. Being able to compare their consumption with that of their neighbors motivated many users to reduce their consumption. Similarly, in the case of the national industrial complex, toxic pipelines were colored red to alert international laborers who did not know Koreans to be cautious. This step reduced workplace accidents. In short, using a vivid color and improving readability increased competitiveness among residents and safety among laborers.

4.2. Influence of User Research on the Waterless Toilet Design

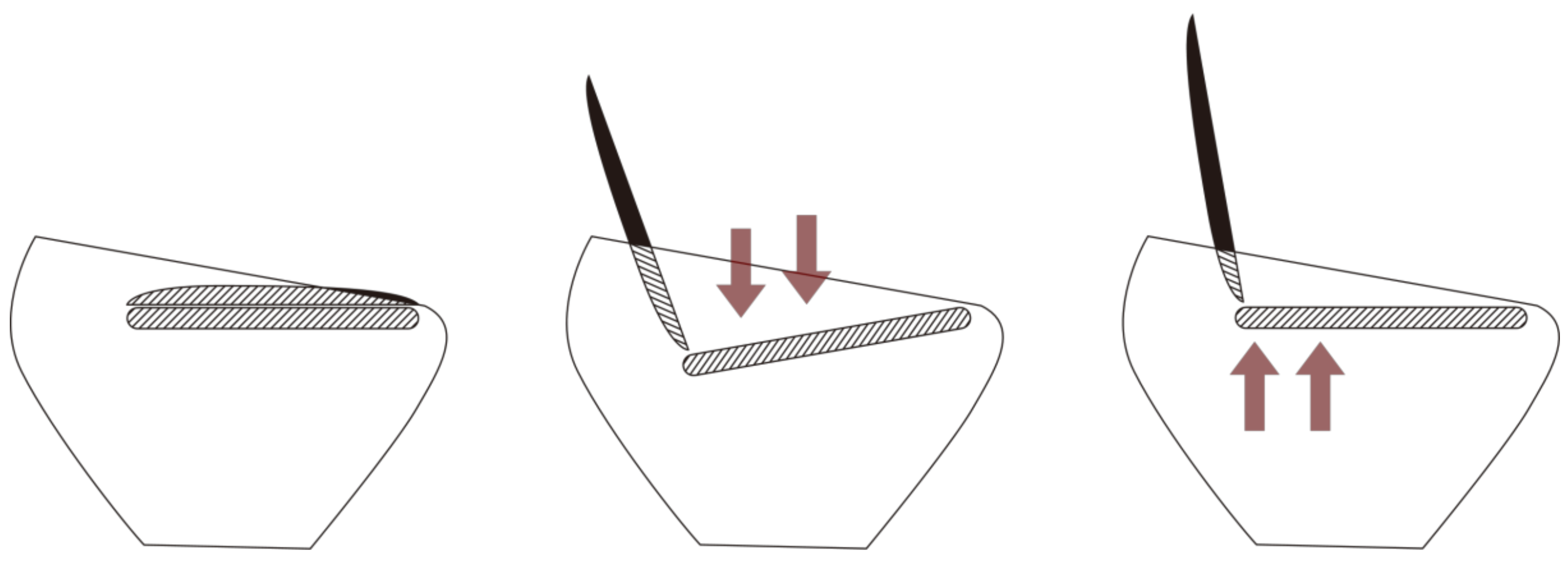

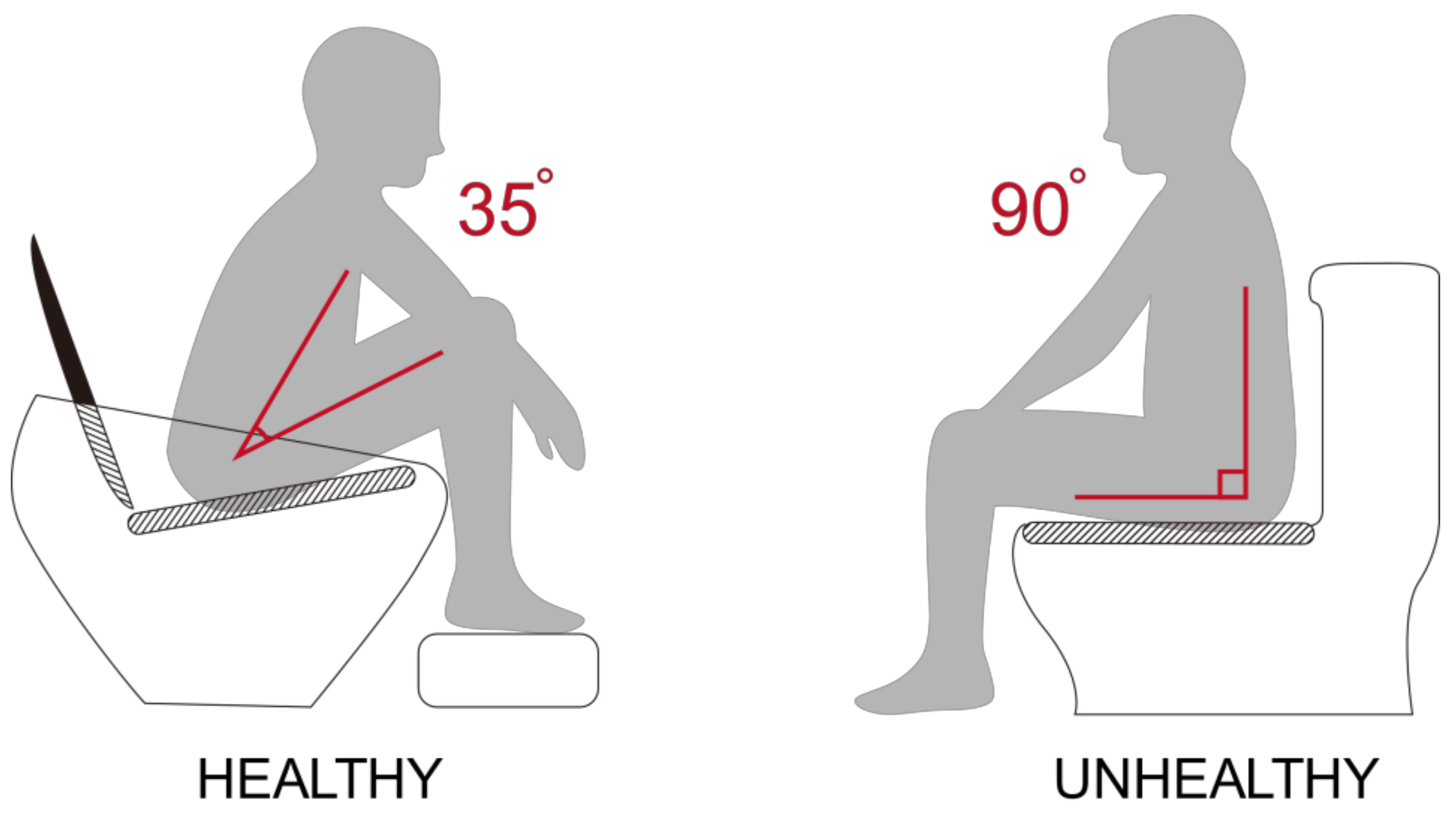

5. Prototyping: Waterless Toilet Design

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gorb, P.; Dumas, A. Silent design. Des. Stud. 1987, 8, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudelson, J. Dry Run: Preventing the Next Urban Water Crisis; New Society Publisher: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP (The United Nations Environment Programme as part of its Green Economy Initiative). Overview of The Republic of Korea’s National Strategy for Green Growwth; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.C. Eutrophication Status and countermeasures of the river. Water J. 2009. Available online: http://www.waterjournal.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=8585 (accessed on 4 November 2015).

- Water, K. Saving Water. Available online: http://www.kwater.or.kr/info/sub01/watersavePage.do?s_mid=93 (accessed on 30 October 2015).

- Cho, S.H.; Kang, H.J.; Park, H.C.; Rhee, E.K. A Study on the Methodology of Water Saving in Multi-Family Residential Building. J. Korean Soc. Living Environ. Syst. 2012, 19, 525–535. [Google Scholar]

- Dragert, J. Fighting the urine blindness to provide more sanitation options. Water SA-Pretoria 1998, 24, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.G.; Reinertsen, D.G. Developing Products in Half the Time; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, T.; Littman, J. The Ten Faces of Innovation; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Von Stamm, B. Managing Design, Innovation and Creativity; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Keikonen, T.K.; Jääskö, V.; Mattelmäki, T.M. Three-in-one user study for focused collaboration. Int. J. Des. 2008, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dosi, G. Technological paradigms and technological trajectories: A suggested interpretation of the determinants and directions of technical change. Res. Policy 1987, 11, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.R.; Winter, S.G. In search of a useful theory of innovation. Res. Policy 1997, 6, 36–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verganti, R. Radical design and technology epiphanies: A new focus for research on design management. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2011, 28, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P. Design Council (2008) Introduction to Emerging Technology; 2008. Available online: http://www.designcouncil.org.uk/AutoPdfs/Emerging_technology.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2015).

- Moenaert, R.; De Meyer, A.; Souder, W.E.; Deschoolmeester, D. R&D/Marketing Communication During the Fuzzy Front-End. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 1995, 42, 243–259. [Google Scholar]

- Khurana, A.; Rosenthal, S.R. Integrating the fuzzy front end of new product development. Sloan Management Review. 15 January 1997.

- Krishnan, V.; Ulrich, K.T. Product development decisions: A review of the literature. Manag. Sci. 2001, 47, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, K.; Eppinger, S. Product and Design Development, 5th ed.; McGrawHill: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Von Hippel, E. Democratizing Innovation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gulliksen, J.; Goransson, B.; Boivie, I.; Blomkvist, S.; Persson, J.; Cajander, A. Key principles for user-centered systems design. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2003, 22, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruitt, J.; Adlin, T. The Persona Lifecycle: Keeping People in Mind Throughout Product Design; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer, E. Institutionalization of Usability; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik, D.; Becker, R. Need finding: The why and how of uncovering people’s needs. Des. Manag. J. 1999, 10, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Laurel, B. Design Research: Methods and Perspectives; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mojota, B. Design Management: Using Design to Build Brand Value and Corporate Innovation; Allworth Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. On the essential contexts of artifacts or on the proposition that design is making sense (of things). Des. Issues 1989, 5, 9–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossberg, L. A marketing approach to the tourist experience. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2007, 7, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J., II; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, C.; Zomerdijk, L. Innovation in Experiential Services—An Empirical View; Innovation in Services; DTI: London, UK, 2007; pp. 97–134. [Google Scholar]

- Press, M.; Cooper, R. Design Experience; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Farnham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D. The Reflective Practitioner; Basic Books: NewYork, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, B. How Designers Think, 4th ed.; Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Loch, C.; DeMeyer, A.; Pich, M.T. Managing the Unknown: A New Approach to Managing High Uncertainty and Risk in Projects; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew, D.J.; Bias, R.G. Cost-Justifying Usability; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, D.; Harris, M. The Challenge of Co-Production: HOW equal Partnership between Professionals and Piblic are Crucial to Improving Public Service; NESTA: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ramswamy, V.; Gouillart, F. Building the Co-creating Enterprise. Harvard Business Review 15 October 2010. 100–109.

- Buchenau, M.; Suri, J.F. Experience prototyping. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques, Brooklyn, NY, USA, 17–19 August 2000; pp. 424–433. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzblatt, K.; Wendell, J.B.; Wood, S. Rapid Contextual Design; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Burr, J.; Larsen, H. The Quality of Conventions in Participatory Innovation. Codesign 2010, 6, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, H.-K. Designing a Waterless Toilet Prototype for Reusable Energy Using a User-Centered Approach and Interviews. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 919. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9050919

Lee H-K. Designing a Waterless Toilet Prototype for Reusable Energy Using a User-Centered Approach and Interviews. Applied Sciences. 2019; 9(5):919. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9050919

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Hyun-Kyung. 2019. "Designing a Waterless Toilet Prototype for Reusable Energy Using a User-Centered Approach and Interviews" Applied Sciences 9, no. 5: 919. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9050919

APA StyleLee, H.-K. (2019). Designing a Waterless Toilet Prototype for Reusable Energy Using a User-Centered Approach and Interviews. Applied Sciences, 9(5), 919. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9050919