Integrated Predictor Based on Decomposition Mechanism for PM2.5 Long-Term Prediction

Abstract

:Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

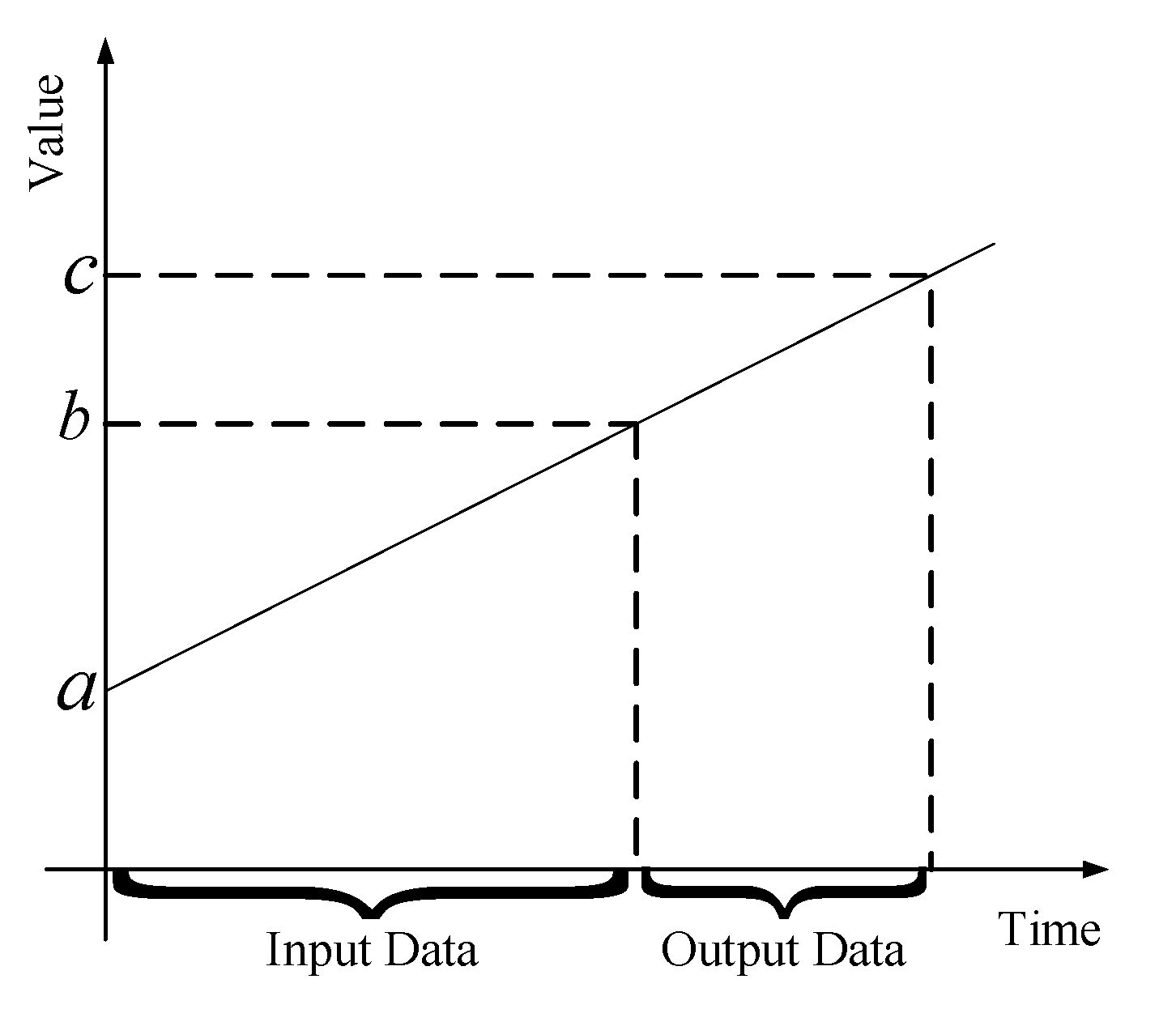

- Trend component: This refers to the main trend direction of PM2.5 time-series data. This part often includes the trend of linear growth and decline. The trend component in PM2.5 data reflects the pollution of weather over a long period of time. If there are negative effects such as industrial pollution and automobile exhaust, the trend component of PM2.5 will exhibit linear growth. Conversely, if the air quality improves, the trend component of PM2.5 data will slowly decrease.

- (2)

- Period component: This refers to the data fluctuation that occurs repeatedly over a period of time. We found that the PM2.5 data had obvious period characteristics in one day; that is, the value during the day is higher and is lower than at night.

- (3)

- Residual component: This refers to the remaining part of the original data minus the trend and period components, and usually consists of complex nonlinear element and noise.

2. Distributed Decomposition Model

2.1. Model Framework

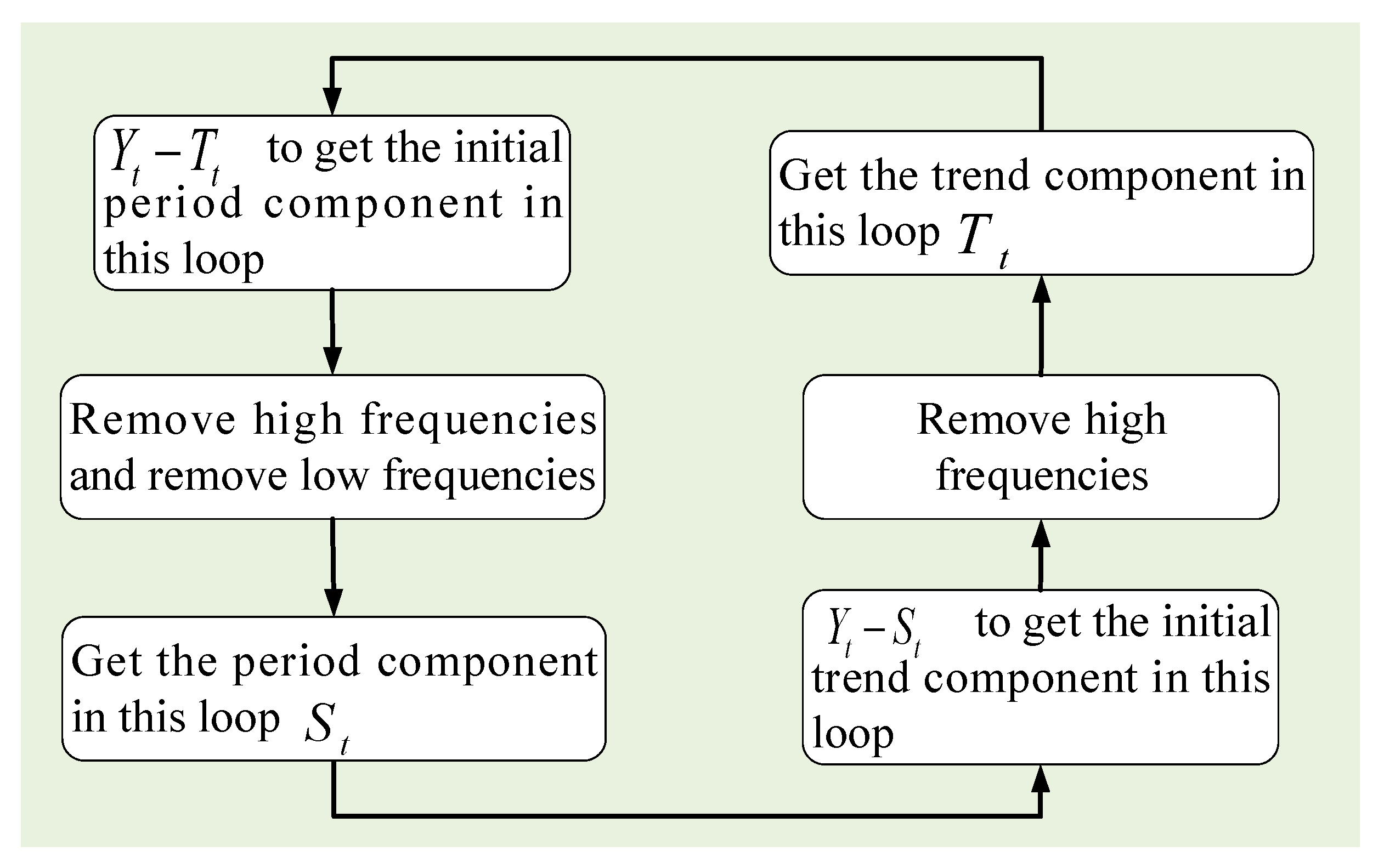

2.2. Decomposition

2.3. Autoregressive-Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) Model: Prediction Model for Trend Component

2.4. Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) Network: Deep Prediction Network for Periodic and Residual Components

- The update gate controls the degree to which the state information at a previous time is brought into the current state. The larger the value of the update gate, the more status information from a previous moment is brought in.

- The reset gate decides how much information is written to the current candidate activation in the previous state. The smaller the reset gate, the less information of the previous state is written.

3. Experiments

3.1. Dataset and Experimental Setup

3.2. Evaluation of Prediction Results

3.3. Case 1

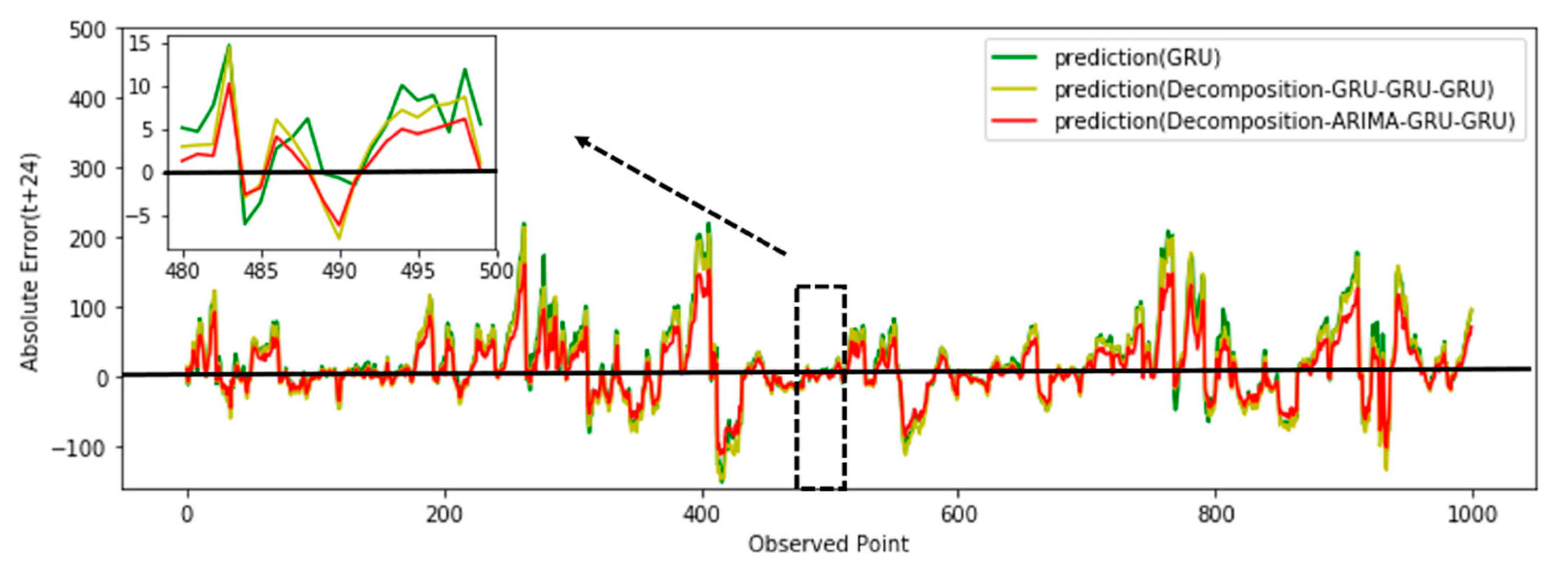

- The GRU method [37]: The original time-series data are not decomposed, and the GRU is directly trained to establish a prediction model.

- Decomposition with the GRU-GRU-GRU method: The original time-series data are first decomposed according the method mentioned in Section 2.2, then the three components are trained to establish three sub-prediction GRU models. We can observe that this method is different from the model proposed here because it modeled the trend component by GRU, while in the proposed model, named in Figure 5 as decomposition, it was with ARIMA-GRU-GRU, which modeled the trend component by ARIMA.

3.4. Case 2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rybarczyk, Y.; Zalakeviciute, R. Machine learning approaches for outdoor air quality modelling: A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ding, W. Prediction of air pollutants concentration based on an extreme learning machine: The case of Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Ren, W. Prediction of Air Pollution Concentration Based on mRMR and Echo State Network. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F. Two-stage least squares based iterative estimation algorithm for CARARMA system modeling. Appl. Math. Model. 2013, 37, 4798–4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F. Decomposition based fast least squares algorithm for output error systems. Signal Process. 2013, 93, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Jiang, X.; Wan, X.K.; Ding, W. A filtering based multi-innovation extended stochastic gradient algorithm for multivariable control systems. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2017, 15, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Liu, X.P.; Liu, G. Gradient based and least-squares based iterative identification methods for OE and OEMA systems. Digit. Signal Process. 2010, 20, 664–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Ding, F.; Wu, M.H. Recursive parameter estimation algorithm for multivariate output-error systems. J. Frankl. Inst. 2018, 355, 5163–5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Y.; Ding, F.; Xu, L.; Yang, E.F. Partially coupled gradient estimation algorithm for multivariable equation-error autoregressive moving average systems using the data filtering technique. IET Control Theory Appl. 2019, 13, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Liu, X.G.; Chu, J. Gradient-based and least-squares-based iterative algorithms for Hammerstein systems using the hierarchical identification principle. IET Control Theory Appl. 2013, 7, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.J.; Ding, F. Decomposition- and gradient-based iterative identification algorithms for multivariable systems using the multi-innovation theory. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 38, 2971–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, F.; Xu, L.; Yang, E.F. State filtering-based least squares parameter estimation for bilinear systems using the hierarchical identification principle. IET Control Theory Appl. 2018, 12, 1704–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, F.; Xu, L.; Yang, E.F. Highly computationally efficient state filter based on the delta operator. Int. J. Adapt. Control Signal Process. 2019, 33, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.Y.; Huang, H.; Du, W.P. Relevance analysis and short-term prediction of PM2.5 concentrations in Beijing based on multi-source data. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 150, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Niu, Z. VAR Model of PM2.5, Weather and Traffic in Los Angeles-Long Beach Area. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Environmental Science and Information Application Technology, Wuhan, China, 4–5 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Zhao, Z.; Nguyen, D.D.; Wei, G.W. Feature functional theory–binding predictor (FFT–BP) for the blind prediction of binding free energies. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2017, 136, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Lu, X. The prediction of PM2.5 value based on ARMA and improved BP neural network model. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Intelligent Networking and Collaborative Systems, Ostrawva, Czech Republic, 7–9 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Prediction algorithm of PM2.5 mass concentration based on adaptive BP neural network. Computing 2018, 100, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Shu, T.; Chen, S.; Wang, S.; Lai, K.K.; Lu, G. An improved grey neural network model for predicting transportation disruptions. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 45, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiming, Z.; Xiaoxiao, S. Study on prediction of atmospheric PM2.5 based on RBF neural network. In Proceedings of the 2013 Fourth International Conference on Digital Manufacturing & Automation, Qingdao, China, 29–30 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- García-Mozo, H.; Oteros, J.A.; Galán, C. Impact of land cover changes and climate on the main airborne pollen types in Southern Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 548, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesús, R.; Rivero, R.; Jorge, R.-M.; Federico, F.-G.; Rosa, P.-B. Modeling pollen time series using seasonal-trend decomposition procedure based on LOESS smoothing. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2017, 61, 335–348. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, F.; Yang, Y.X.; Zeng, A.M.; Jing, Y.F. Analysis of seasonal signals and long-term trends in the height time series of IGS sites in China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2016, 59, 1283–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 1986, 23, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.; Van Merrienboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, R.; Wu, J.L.; Chang, P.C. A deep recurrent neural network for air quality classification. J. Inf. Hiding Multimed. Signal Process 2018, 9, 346–354. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.J.; Kuo, P.H. A deep cnn-lstm model for particulate matter (PM2.5) forecasting in smart cities. Sensors 2018, 18, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, U.; Ma, J.; Ryu, U.; Ryom, K.; Juhyok, U.; Pak, K.; Pak, C. Deep learning-based PM2.5 prediction considering the spatiotemporal correlations: A case study of Beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagum, E.B.; Luati, A. Global and local statistical properties of fixed-length nonparametric smoothers. Stat. Methods Appl. 2002, 11, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, R.B.; Cleveland, W.S.; McRae, J.E.; Terpenning, I. STL: A seasonal-trend decomposition procedure based on loess. J. Off. Stat. 1990, 6, 3–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Liang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Guo, H.; He, D.; Zhao, L. Six-decade temporal change and seasonal decomposition of climate variables in Lake Dianchi watershed (China): Stable trend or abrupt shift. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2015, 119, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G.; Gwilym, M.; Gregory, C.; Greta, M. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 93–123. [Google Scholar]

- Libert, G. A New Look at the Statistical Model Identification. Automat. Control IEEE Trans. 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhou, K.; You, S.; Neumann, U. Scene labeling using gated recurrent units with explicit long range conditioning. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.07485. [Google Scholar]

- Mission China. Available online: http://www.stateair.net/web/historical/1/1.html (accessed on 20 July 2017).

- Xie, R.; Ding, Y.; Hao, K.; Lei, C.; Tong, W. Using gated recurrence units neural network for prediction of melt spinning properties. In Proceedings of the 2017 11th Asian Control Conference (ASCC), Gold Coast, Australia, 17–20 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, F.; Yang, E.F. State estimation for bilinear systems through minimizing the covariance matrix of the state estimation errors. Int. J. Adapt. Control Signal Process. 2019, 33, 1157–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Pan, J.; Ding, F.; Xu, L.; Ding, W. Partially-coupled least squares based iterative parameter estimation for multi-variable output-error-like autoregressive moving average systems. IET Control Theory Appl. 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.H.; Liu, X.M.; Ding, F. The filtering-based maximum likelihood iterative estimation algorithms for a special class of nonlinear systems with autoregressive moving average noise using the hierarchical identification principle. Int. J. Adapt. Control Signal Process. 2019, 33, 1189–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Ding, F.; Xu, L.; Hayat, T. Hierarchical principle-based iterative parameter estimation algorithm for dual-frequency signals. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 38, 3251–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.J.; Ding, F.; Xu, L.; Pan, J.; Alsaedi, A.; Hayat, T. Maximum likelihood recursive identification for the multivariate equation-error autoregressive moving average systems using the data filtering. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 41154–41163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.X.; Xiong, W.L.; Chen, J.; Ding, F. Hierarchical identification for multivariate Hammerstein systems by using the modified Kalman filter. IET Control Theory Appl. 2017, 11, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.X.; Ding, F. Filtering-based multistage recursive identification algorithm for an input nonlinear output-error autoregressive system by using the key term separation technique. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2017, 36, 577–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Ding, F. New gradient based identification methods for multivariate pseudo-linear systems using the multi-innovation and the data filtering. J. Frankl. Inst. 2017, 354, 1568–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Wang, F.F.; Xu, L.; Wu, M.H. Decomposition based least squares iterative identification algorithm for multivariate pseudo-linear ARMA systems using the data filtering. J. Frankl. Inst. 2017, 354, 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Ding, F.; Li, J.H. States based iterative parameter estimation for a state space model with multi-state delays using decomposition. Signal Process. 2015, 106, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Ding, F.; Li, J.H. State filtering and parameter estimation for linear systems with d-step state-delay. IET Signal Process. 2014, 8, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F. Combined state and least squares parameter estimation algorithms for dynamic systems. Appl. Math. Model. 2014, 38, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F. Coupled-least-squares identification for multivariable systems. IET Control Theory Appl. 2013, 7, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F. Hierarchical multi-innovation stochastic gradient algorithm for Hammerstein nonlinear system modeling. Appl. Math. Model. 2013, 37, 1694–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Ding, F.; Shi, Y. An efficient hierarchical identification method for general dual-rate sampled-data systems. Automatica 2014, 50, 962–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Liu, G.; Liu, X.P. Partially coupled stochastic gradient identification methods for non-uniformly sampled systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2010, 55, 1976–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Ding, F.; Liu, X.P.; Liu, G. Hierarchical least squares identification for linear SISO systems with dual-rate sampled-data. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2011, 56, 2677–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Ding, F. Novel data filtering based parameter identification for multiple-input multiple-output systems using the auxiliary model. Automatica 2016, 71, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Liu, Y.J.; Bao, B. Gradient based and least squares based iterative estimation algorithms for multi-input multi-output systems. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part I J. Syst. Control Eng. 2012, 226, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | RMSE | NRMSE | MAE | SMAPE | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRU [37] | 83.0925 | 0.1848 | 56.3784 | 0.7133 | 0.6389 |

| Decomposition-GRU-GRU-GRU model | 81.2412 | 0.1625 | 56.1870 | 0.7398 | 0.6471 |

| The proposed Decomposition-ARIMA -GRU-GRU model | 80.1620 | 0.1612 | 55.1060 | 0.6682 | 0.6508 |

| Model | RMSE | NRMSE | MAE | SMAPE | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLI-ESN [3] | 65.7108 | 0.1966 | 46.0633 | 0.5443 | 0.7314 |

| The proposed Decomposition-GRU-GRU-GRU model | 59.4658 | 0.1237 | 37.5384 | 0.4520 | 0.8136 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, X.; Yang, N.; Wang, X.; Bai, Y.; Su, T.; Kong, J. Integrated Predictor Based on Decomposition Mechanism for PM2.5 Long-Term Prediction. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4533. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214533

Jin X, Yang N, Wang X, Bai Y, Su T, Kong J. Integrated Predictor Based on Decomposition Mechanism for PM2.5 Long-Term Prediction. Applied Sciences. 2019; 9(21):4533. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214533

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Xuebo, Nianxiang Yang, Xiaoyi Wang, Yuting Bai, Tingli Su, and Jianlei Kong. 2019. "Integrated Predictor Based on Decomposition Mechanism for PM2.5 Long-Term Prediction" Applied Sciences 9, no. 21: 4533. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214533

APA StyleJin, X., Yang, N., Wang, X., Bai, Y., Su, T., & Kong, J. (2019). Integrated Predictor Based on Decomposition Mechanism for PM2.5 Long-Term Prediction. Applied Sciences, 9(21), 4533. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214533