Conscious and Non-Conscious Measures of Emotion: Do They Vary with Frequency of Pornography Use?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Ease of Access

1.2. Pornography Use and Its Behavioural Effects

1.3. Physiological Effects of Pornography

1.4. Self-Report

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Stimuli

2.4. Procedure

2.4.1. Lab Experiment

2.4.2. Experiment Task

2.5. Analysis

2.5.1. Questionnaire Analysis and Formation of Groups

2.5.2. Explicit Responses

2.5.3. Event-Related Potentials

2.5.4. Startle Reflex Modulation

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

3.2. Self-Reported Pornography Use and Self-Monitoring

3.3. Explicit Responses

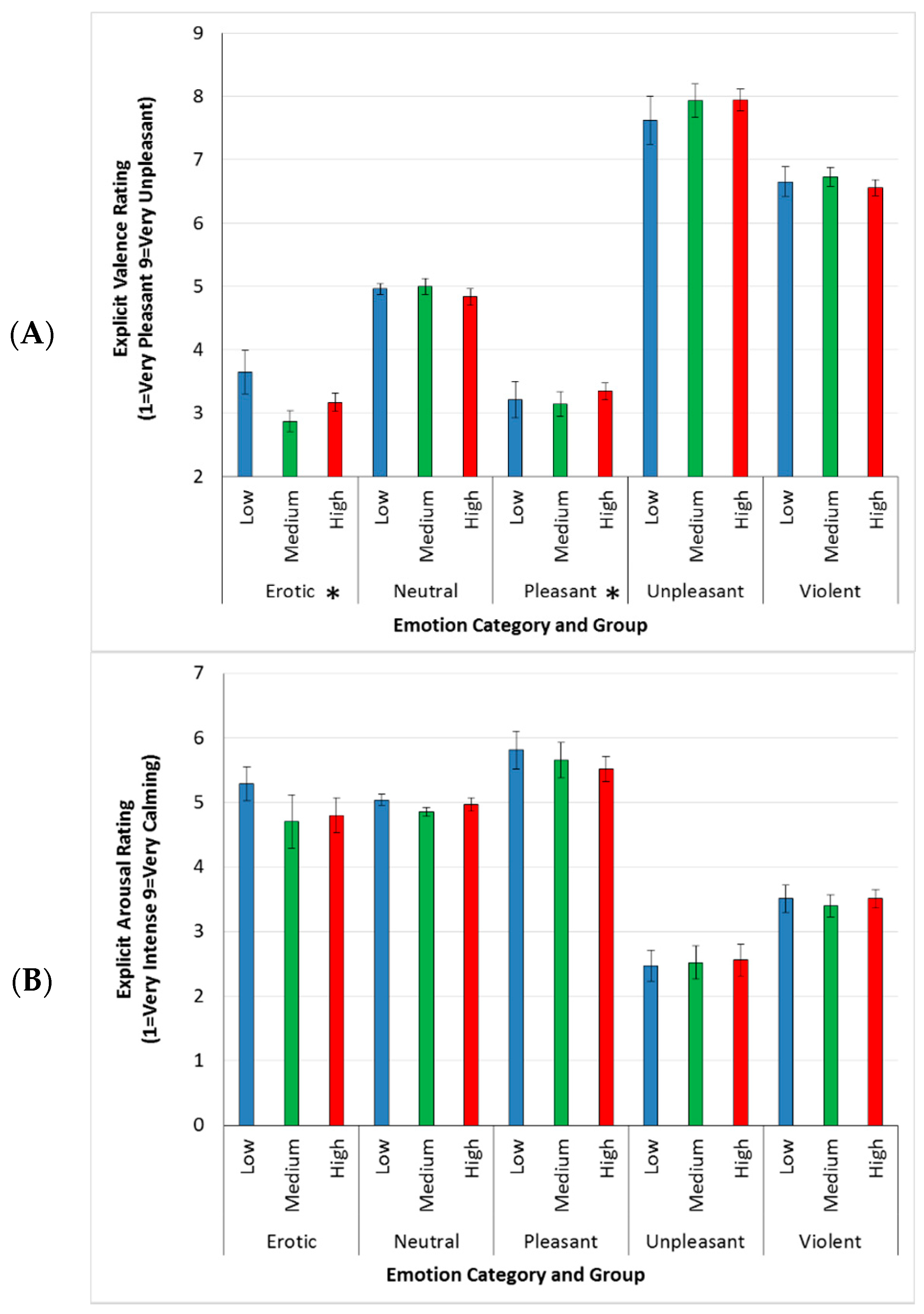

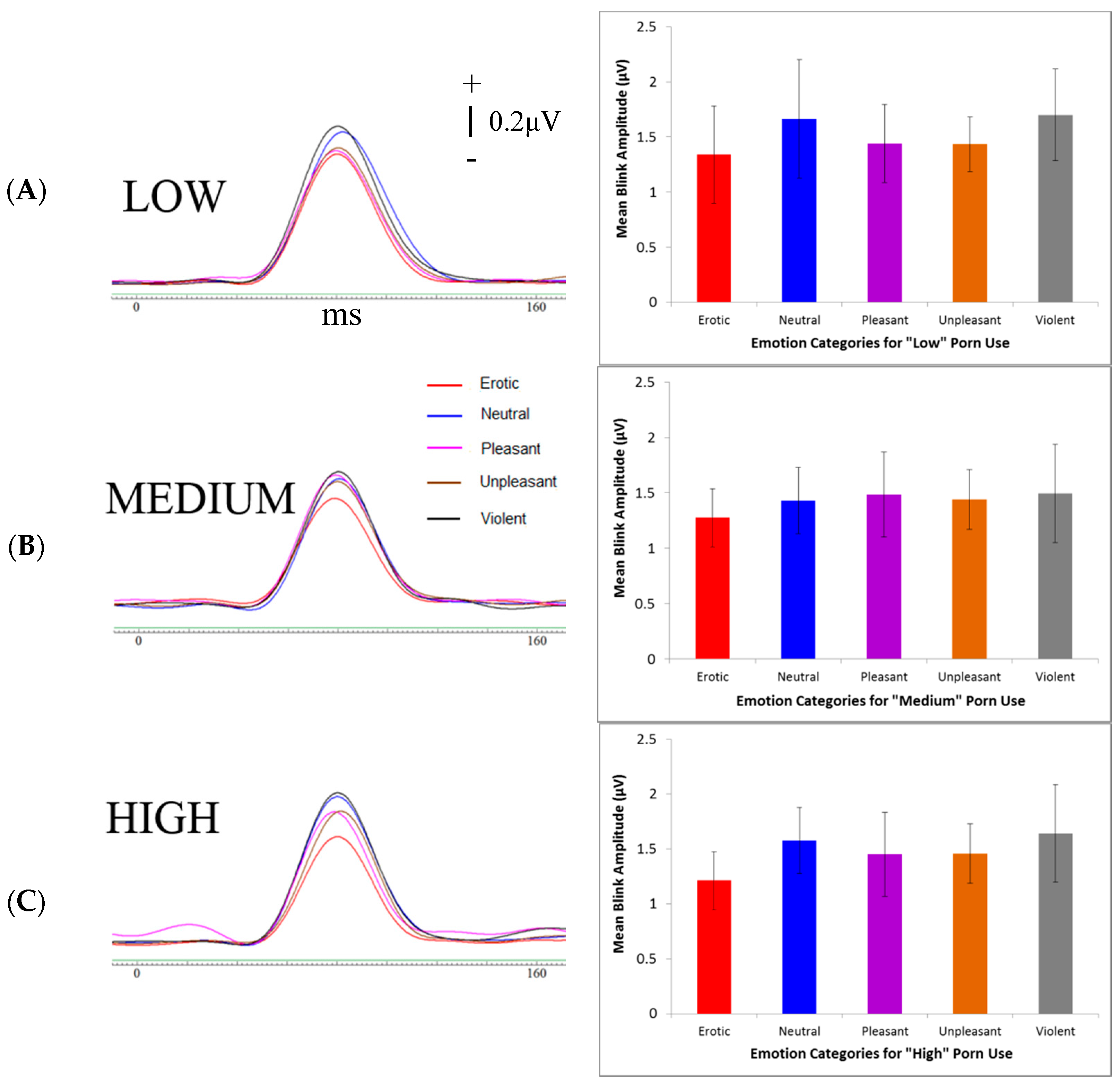

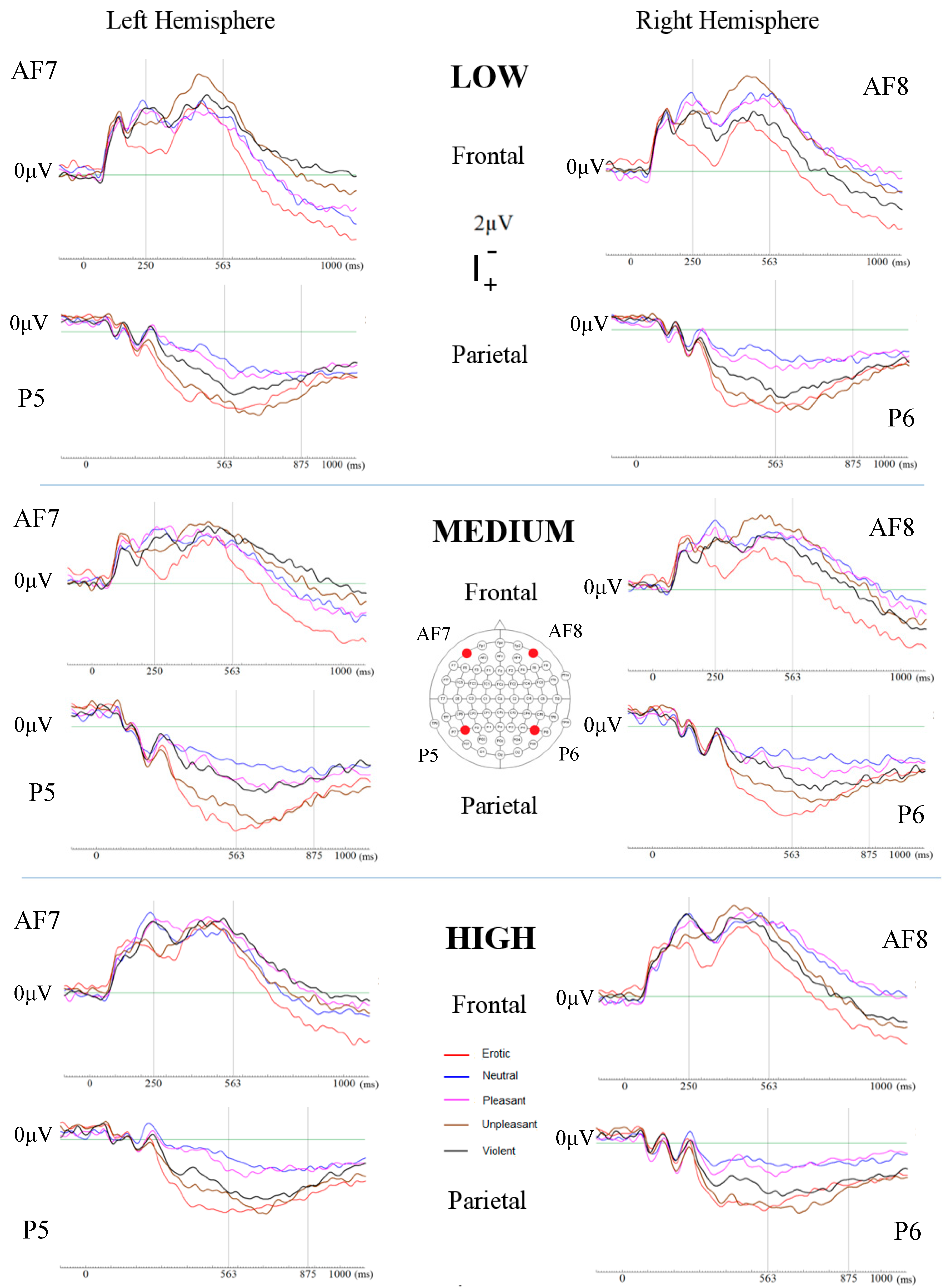

3.4. Physiological Measures

4. Discussion

4.1. Explicit Ratings

4.2. Event-Related Potentials (ERPs)

4.3. Startle Reflex Modulation (SRM)

4.4. Limitations

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harkness, E.L.; Mullan, B.; Blaszczynski, A. The Association Between Internet Pornography Consumption and Sexual Risk Behavior in Heterosexual Adult Australian Residents. In Proceedings of the Australiasian Society of Behavioural Helath and Medicine, Auckland, New Zealand, 12–14 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, W.A.; Barak, A. Internet pornography: A social psychological perspective on internet sexuality. J. Sex. Res. 2001, 38, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, S.; Gallinat, J. Brain structure and functional connectivity associated with pornography consumption: The brain on porn. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A. Sexuality and the Internet: Surfing into the new millennium. CyberPsychol. Behav. 1998, 1, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.C.; Carpenter, B.N.; Hook, J.N.; Garos, S.; Manning, J.C.; Gilliland, R.; Cooper, E.B.; McKittrick, H.; Davtian, M.; Fong, T. Report of findings in a DSM-5 field trial for hypersexual disorder. J. Sex. Med. 2012, 9, 2868–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, M.; Emmers, T.; Gebhardt, L.; Giery, M.A. Exposure to Pornography and Acceptance of Rape Myths. J. Commun. 1995, 45, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prause, N.; Steele, V.R.; Staley, C.; Sabatinelli, D. Late positive potential to explicit sexual images associated with the number of sexual intercourse partners. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosc. 2015, 10, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prause, N.; Steele, V.R.; Staley, C.; Sabatinelli, D.; Hajcak, G. Modulation of late positive potentials by sexual images in problem users and controls inconsistent with “porn addiction”. Biol. Psychol. 2015, 109, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, A.; Yang, M.; Ullrich, S.; Zhang, T.; Coid, J.; King, R.; Murphy, R. Men’s pornography consumption in the UK: Prevalence and associated problem behaviour. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2015, 16360. [Google Scholar]

- Buzzell, T.; Foss, D.; Middleton, Z. Explaining use of online pornography: A test of self-control theory and opportunities for deviance. J. Crim. Justice Pop. Cult. 2006, 13, 96–116. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, D.L., Jr.; Watts, C. Pornography addiction: A neuroscience perspective. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2011, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mancini, C.; Reckdenwald, A.; Beauregard, E. Pornographic exposure over the life course and the severity of sexual offenses: Imitation and cathartic effects. J. Crim. Justice 2012, 40, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, M.C. Psychophysiological assessment of paraphilic sexual interests In The Psychophysiology of Sex; Janssen, E., Ed.; University of Indiana Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2007; pp. 475–491. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, V.R.; Staley, C.; Fong, T.; Prause, N. Sexual desire, not hypersexuality, is related to neurophysiological responses elicited by sexual images. Socioaffect. Neurosci. Psychol. 2013, 3, 20770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, V.; Malamuth, N.M. Predicting sexual aggression: The role of pornography in the context of general and specific risk factors. Aggress. Behav. 2007, 33, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, P.J.; Tokunaga, R.S.; Kraus, A. A Meta-Analysis of Pornography Consumption and Actual Acts of Sexual Aggression in General Population Studies. J. Commun. 2015, 66, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolucci, E.O.; Genuis, M.; Violato, C. A meta-analysis of the published research on the effects of pornography. Med. Mind Adolesc. 1997, 72, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S.A. The role of pornography in sexual offenses: Information for law enforcement & forensic psychologists. Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Health Hum. Resil. 2015, 17, 239–242. [Google Scholar]

- Hald, G.M.; Malamuth, N.M.; Yuen, C. Pornography and attitudes supporting violence against women: Revisiting the relationship in nonexperimental studies. Aggress. Behav. 2010, 36, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, C.J.; Hartley, R.D. The pleasure is momentary…the expense damnable? The influence of pornography on rape and sexual assault. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2009, 14, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, D.M.; Stewart-Richardson, D.N. Psychological, relational, and sexual correlates of pornography use on young adult heterosexual men in romantic relationships. J. Men's Stud. 2014, 22, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, S.R. Frequency of Pornography Use Is Indirectly Associated with Lower Relationship Confidence through Depression Symptoms and Physical Assault among Chinese Young Adults. Master’s Thesis, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.Y.; Wilson, G.; Berger, J.; Christman, M.; Reina, B.; Bishop, F.; Klam, W.P.; Doan, A.P. Is Internet Pornography Causing Sexual Dysfunctions? A Review with Clinical Reports. Behav. Sci. 2016, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavratzakis, A.; Herbert, C.; Walla, P. Emotional facial expressions evoke faster orienting responses, but weaker emotional responses at neural and behavioral levels compared to scenes: A simultaneous EEG and facial EMG study. Neuroimage 2016, 124, 931–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linden, D.E. The P300: Where in the brain is it produced and what does it tell us? Neuroscientist 2005, 11, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voon, V.; Mole, T.B.; Banca, P.; Porter, L.; Morris, L.; Mitchell, S.; Lapa, T.R.; Karr, J.; Harrison, N.A.; Potenza, M.N.; et al. Neural correlates of sexual cue reactivity in individuals with and without compulsive sexual behaviours. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minnix, J.A.; Versace, F.; Robinson, J.D.; Lam, C.Y.; Engelmann, J.M.; Cui, Y.; Borwn, V.L.; Cinciripini, P.M. The late positive potential (LPP) in response to varying types of emotional and cigarette stimuli in smokers: A content comparison. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2013, 89, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavratzakis, A.; Molloy, E.; Walla, P. Modulation of the startle reflex during brief and sustained exposure to emotional pictures. Psychology 2013, 4, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.J.; Bradley, M.M.; Cuthbert, B.N. Emotion, attention, and the startle reflex. Psychol. Rev. 1990, 97, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, C.J.; Bradley, M.M.; Lang, P.J. Emotion in the criminal psychopath: Startle reflex modulation. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1993, 102, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, G.S.; Walla, P.; Arthur-Kelly, M. Towards improved ways of knowing children with profound multiple disabilities: Introducing startle reflex modulation. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2013, 16, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrlichman, H.; Brown Kuhl, S.; Zhu, J.; Wrrenburg, S. Startle reflex modulation by pleasant and unpleasant odors in a between-subjects design. Psychophysiology 1997, 34, 726–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, M.E.; Hazlett, E.A.; Filion, D.L.; Nuechterlein, K.H.; Schell, A.M. Attention and schizophrenia: Impaired modulation of the startle reflex. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1993, 102, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahl, A.; Greiner, U.; Walla, P. Bottle shape elicits gender-specific emotion: A startle reflex modulation study. Psychology 2012, 7, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiser, M.; Walla, P. Objective measures of emotion during virtual walks through urban neighbour-hoods. Appl. Sci. 2011, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walla, P.; Rosser, L.; Scharfenberger, J.; Duregger, C.; Bosshard, S. Emotion ownership: Different effects on explicit ratings and implicit responses. Psychology 2013, 4, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, M.; Walla, P. Measuring Affective Information Processing in Information Systems and Consumer Research—Introducing Startle Reflex Modulation. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Information Systems, Orlando, FL, USA, 16–19 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Walla, P.; Koller, M.; Meier, J. Consumer neuroscience to inform consumers—Physiological methods to identify attitude formation related to over-consumption and environmental damage. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walla, P.; Koller, M. Emotion is not what you think it is: Startle Reflex Modulation (SRM) as a measure of affective processing in Neurols. In Lecture Notes in Information Systems and Organization: Information Systems and Neuroscience; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 10, pp. 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Koller, M.; Walla, P. Towards alternative ways to measure attitudes related to consumption: Introducing startle reflex modulation. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2015, 13, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukounas, E.; Over, R. Changes in the magnitude of the eyeblink startle response during habituation of sexual arousal. Behav. Res. Ther. 2000, 38, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, D.M.; Frijda, N.H. Modulation of the acoustic startle response by film-induced fear and sexual arousal. Psychophysiology 1994, 31, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Padial, E.; Vila, J. Fearful and Sexual Pictures Not Consciously Seen Modulate the Startle Reflex in Human Beings. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 61, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunaharan, S.; Walla, P. Clinical Neuroscience—Towards a Better Understanding of Non-Conscious versus Conscious Processes Involved in Impulsive Aggressive Behaviours and Pornography Viewership. Psychology 2014, 5, 1963–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederman, M.W.; Whitley, B.E., Jr. Handbook for Conducting Research on Human Sexuality; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, R.J. Seven sins in the study of emotion: Correctives from affective neuroscience. Brain Cogn. 2003, 52, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukounas, E.; McCabe, M.P. Sexual and Emotional Variables Influencing Sexual Response to Erotica: A Psychophysiological Investigation. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2001, 30, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walla, P.; Brenner, G.; Koller, M. Objective measures of emotion related to brand attitude: A new way to quantify emotion-related aspects relevant to marketing. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walla, P. Non-Conscious Brain Processes Revealed by Magnetoencephalography (MEG). In Magnetoencephalography; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Winkielman, P.; Berridge, K.C. Unconscious Emotion. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 13, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamietto, M.; de Gelder, B. Neural bases of the non-conscious perception of emotional signals. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LimeSurvey: An Open Source Survey Tool/LimeSurvey Project Hamburg, Gemrnay. 2012. Available online: http://www.limesurvey.org (accessed on 1–30 June 2015).

- Snyder, M. Self-monitoring of expressive behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1974, 30, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, E.L.; Mullan, B.; Blaszczynski, A. Association between pornography use and sexual risk behaviors in adult consumers: A systematic review. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, P.J.; Bradley, M.M.; Cuthbert, B.N. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Affective Ratings of Pictures and Instruction Manual; Technical Report A-8; University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dongen, N.N.N.; Van Strien, J.W.; Dijkstra, K. Implicit emotion regulation in the context of viewing artworks: ERP evidence in response to pleasant and unpleasant pictures. Brain Cogn. 2016, 107, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konorski, J. Integrative Activity of the Brain: An Interdisciplinary Approach; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, C.; Hodgins, D.C. Examining correlates of problematic internet pornography use among university students. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuthbert, B.N.; Schupp, H.T.; Bradley, M.M.; Birbaumer, N.; Lang, P.J. Brain potentials in affective picture processing: Covariation with autonomic arousal and affective report. Biol. Psychol. 2000, 52, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon-Jones, E.; Gable, P.A.; Peterson, C.K. The role of asymmetric frontal cortical activity in emotion-related phenomena: A review and update. Biol. Psychol. 2010, 84, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofman, D. The frontal laterality of emotion: A historical overview. Neth. J. Psychol. 2008, 64, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajcak, G.; MacNamara, A.; Olvet, D.M. Event-related potentials, emotion, and emotion regulation: An integrative review. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2010, 35, 129–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarlo, M.; Übel, S.; Leutgeb, V.; Schienle, A. Cognitive reappraisal fails when attempting to reduce the appetitive value of food: An ERP study. Biol. Psychol. 2013, 94, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hald, G.M. Gender differences in pornography consumption among young heterosexual Danish adults. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2006, 35, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalichman, S.C.; Rompa, D. Sexual Sensation Seeking and Sexual Compulsivity Scales: Validity, and Predicting HIV Risk Behavior. J. Pers. Assess. 1995, 65, 586–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, S.; Rosenberg, H. The Pornography Craving Questionnaire: Psychometric Properties. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2014, 43, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hald, G.M.; Malamuth, N.M. Self-perceived effects of pornography consumption. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2008, 37, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kor, A.; Zilcha-Mano, S.; Fogel, Y.A.; Mikulincer, M.; Reid, R.C.; Potenza, M.N. Psychometric development of the Problematic Pornography Use scale. Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugg, M.D.; Mark, R.E.; Walla, P.; Schloerscheidt, A.M.; Birch, C.S.; Allan, K. Dissociation of the neural correlates of implicit and explicit memory. Nature 1998, 392, 595–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 1 | 1.9 |

| Never Married | 39 | 75 |

| De Facto/Living with a partner | 12 | 23.1 |

| Widowed | 0 | 0 |

| Divorced/Separated | 0 | 0 |

| Highest Level of Completed Education | ||

| Primary School | 0 | 0 |

| Secondary School completed | 22 | 42.3 |

| Secondary School not completed | 0 | 0 |

| Trade Qualification | 1 | 1.9 |

| University or other Tertiary Study | 29 | 55.8 |

| Other | 0 | 0 |

| Work | ||

| Full time | 0 | 0 |

| Part time | 7 | 13.5 |

| Unemployed | 0 | 0 |

| Working in the home/home duties | 0 | 0 |

| Retired | 0 | 0 |

| Student | 45 | 86.5 |

| Other | ||

| Country of Birth | ||

| Australia | 47 | 90.4 |

| Other | 5 | 9.6 |

| Ethnicity * | ||

| African | 1 | 1.9 |

| Asian | 2 | 3.8 |

| Caucasian | 47 | 90.4 |

| Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 1 | 1.9 |

| Variable | Low Porn Use (N = 18) | Medium Porn Use (N = 14) | High Porn Use (N = 20) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age | 20.8 | 3 | 20.7 | 2.2 | 22 | 3.5 |

| Hours of Porn Viewed per Year | 6.5 | 2.9 | 31 | 7.7 | 110.4 | 62.8 |

| Snyder Total Score | 10.2 | 3.1 | 9.9 | 4.1 | 12 | 3.3 |

| Electrode Sites | Emotion Category | Time (ms) | F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF7/AF8 | Unpleasant vs. Violent | 250 | 3.236 | 0.048 |

| 484 | 5.682 | 0.006 | ||

| 563 | 3.454 | 0.04 | ||

| P5/P6 | Unpleasant vs. Violent | 563 | 3.454 | 0.04 |

| 719 | 3.938 | 0.026 | ||

| 797 | 3.472 | 0.039 | ||

| 875 | 4.258 | 0.02 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kunaharan, S.; Halpin, S.; Sitharthan, T.; Bosshard, S.; Walla, P. Conscious and Non-Conscious Measures of Emotion: Do They Vary with Frequency of Pornography Use? Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/app7050493

Kunaharan S, Halpin S, Sitharthan T, Bosshard S, Walla P. Conscious and Non-Conscious Measures of Emotion: Do They Vary with Frequency of Pornography Use? Applied Sciences. 2017; 7(5):493. https://doi.org/10.3390/app7050493

Chicago/Turabian StyleKunaharan, Sajeev, Sean Halpin, Thiagarajan Sitharthan, Shannon Bosshard, and Peter Walla. 2017. "Conscious and Non-Conscious Measures of Emotion: Do They Vary with Frequency of Pornography Use?" Applied Sciences 7, no. 5: 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/app7050493

APA StyleKunaharan, S., Halpin, S., Sitharthan, T., Bosshard, S., & Walla, P. (2017). Conscious and Non-Conscious Measures of Emotion: Do They Vary with Frequency of Pornography Use? Applied Sciences, 7(5), 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/app7050493