The Principle of Least Privilege in Microservices: A Systematic Mapping Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

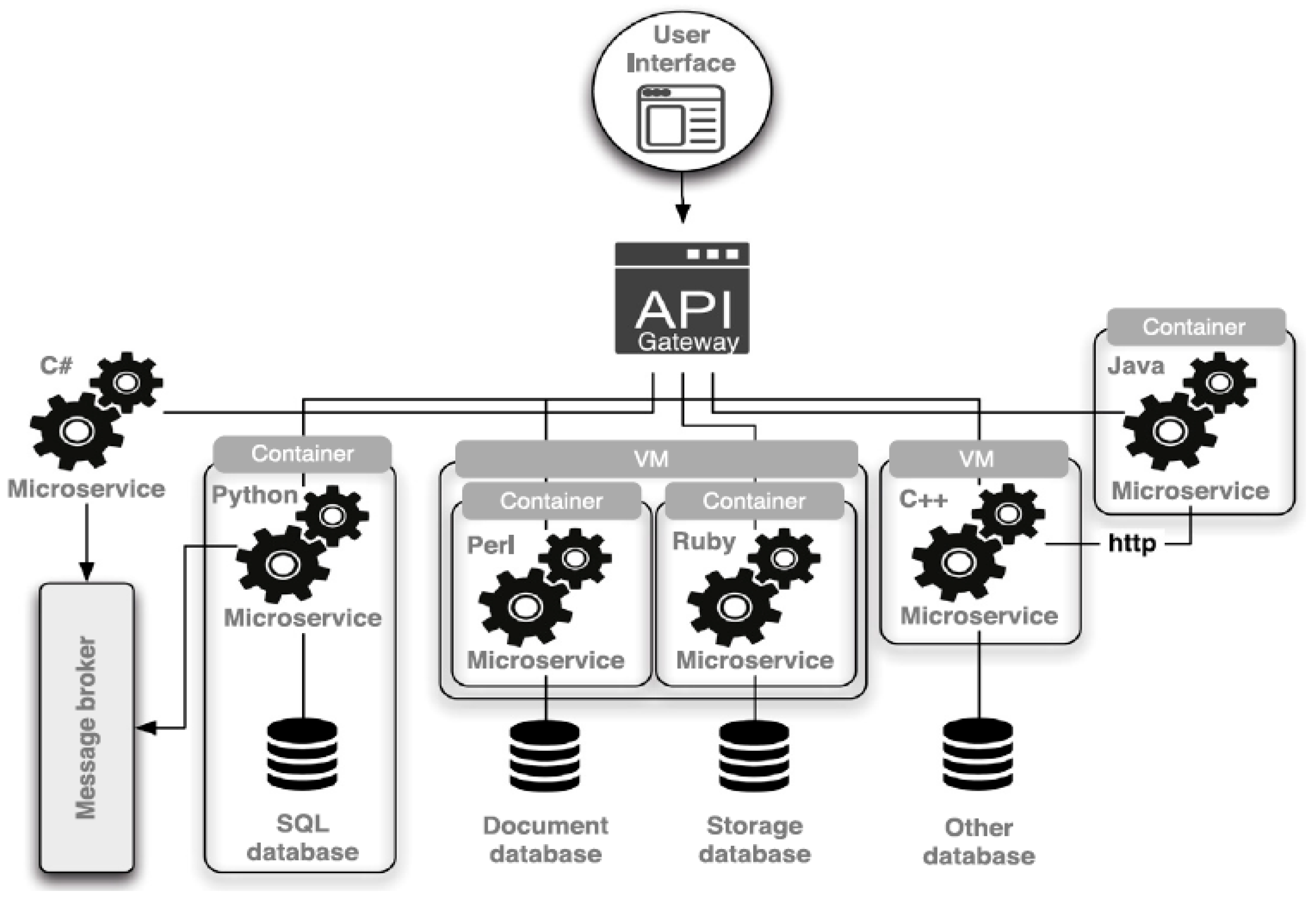

- Distributed nature and dynamic environments: Services are frequently created, scaled, or removed; they communicate across network boundaries; identity and access control policies must adapt dynamically.

- Complexity of policy enforcement: Traditional access control models (e.g., mandatory access control, MAC) may not fully capture contextual or fine-grained requirements in microservices, such as attribute-based or capability-based permissions. Additionally, decentralization increases the complexity of enforcement, in which different microservices are owned by different teams, written in different languages, and deployed on different platforms.

- Awareness and best practices gap: Many practitioners lack sufficient awareness of microservice-specific security challenges.

- Performs this systematic mapping study according to the PoLP in microservices and MSA.

- Determines the most common publication venues in this field.

- Identifies the technical and organizational challenges that arise when enforcing PoLP in microservices.

- Describes the collection of security mechanisms and controls required for PoLP implementation.

- Discusses gaps that remain in research and practice.

2. Background

3. Research Approach

3.1. Research Question Formulation

- RQ1: What are the most prominent publication venues for research in PoLP in MSA?

- RQ2: What are the primary technical challenges in implementing the PoLP in MSA?

- RQ3: What mechanisms, tools, frameworks, or best practices have been proposed or adopted to enforce PoLP in microservices?

- RQ4: What organizational or operational challenges (e.g., human-centered factors) affect the adoption of PoLP in microservices?

- RQ5: What are the identified research gaps and future directions for enforcing PoLP in microservices?

3.2. Search Strategy

- (“least privilege” OR “principle of least privilege”)

- AND

- (“microservices” OR “microservice architecture” OR “MSA”)

- AND

- (“access control” OR “authorization” OR “identity management” OR “RBAC” OR “ABAC” OR “privilege management” OR “service-to-service security” OR “zero trust”)

3.3. Source Selection

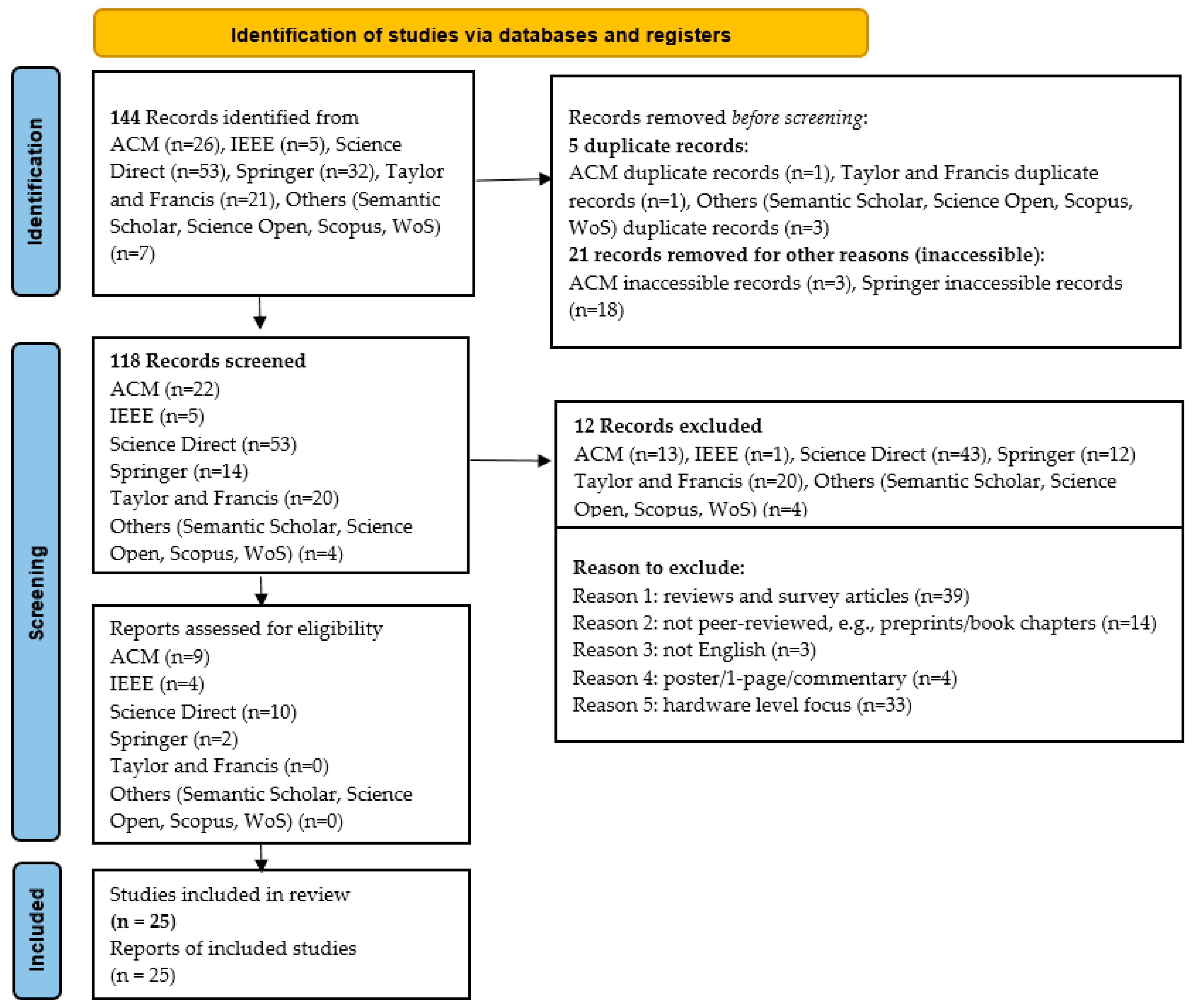

3.4. Study Selection

- Be written in English.

- Be peer-reviewed papers.

- Address the Principle of Least Privilege (PoLP) in microservices as the core topic.

- Offer a proposal (such as a framework, technique, method, control, or tool) for implementing PoLP within Microservice Architectures (MSAs).

- Present a qualitative or quantitative evaluation of PoLP implementation with microservices or MSAs.

- We excluded duplicate and inaccessible studies.

- We excluded studies not focused on PoLP in the context of microservices, as this is our primary area of focus.

- We excluded non-peer-reviewed content (e.g., from preprint repositories).

- We excluded theses (MS/PhD), posters, technical reports, tutorials, editorials, and commentary articles.

- We excluded papers presenting reviews or surveys.

- We excluded papers addressing PoLP implementation in distributed platforms and technologies such as clouds without explicit reference to microservices.

- We excluded papers describing general aspects of Microservice Architectures without significant emphasis on the PoLP issue.

3.5. Quality Assessment

3.6. Information Extraction

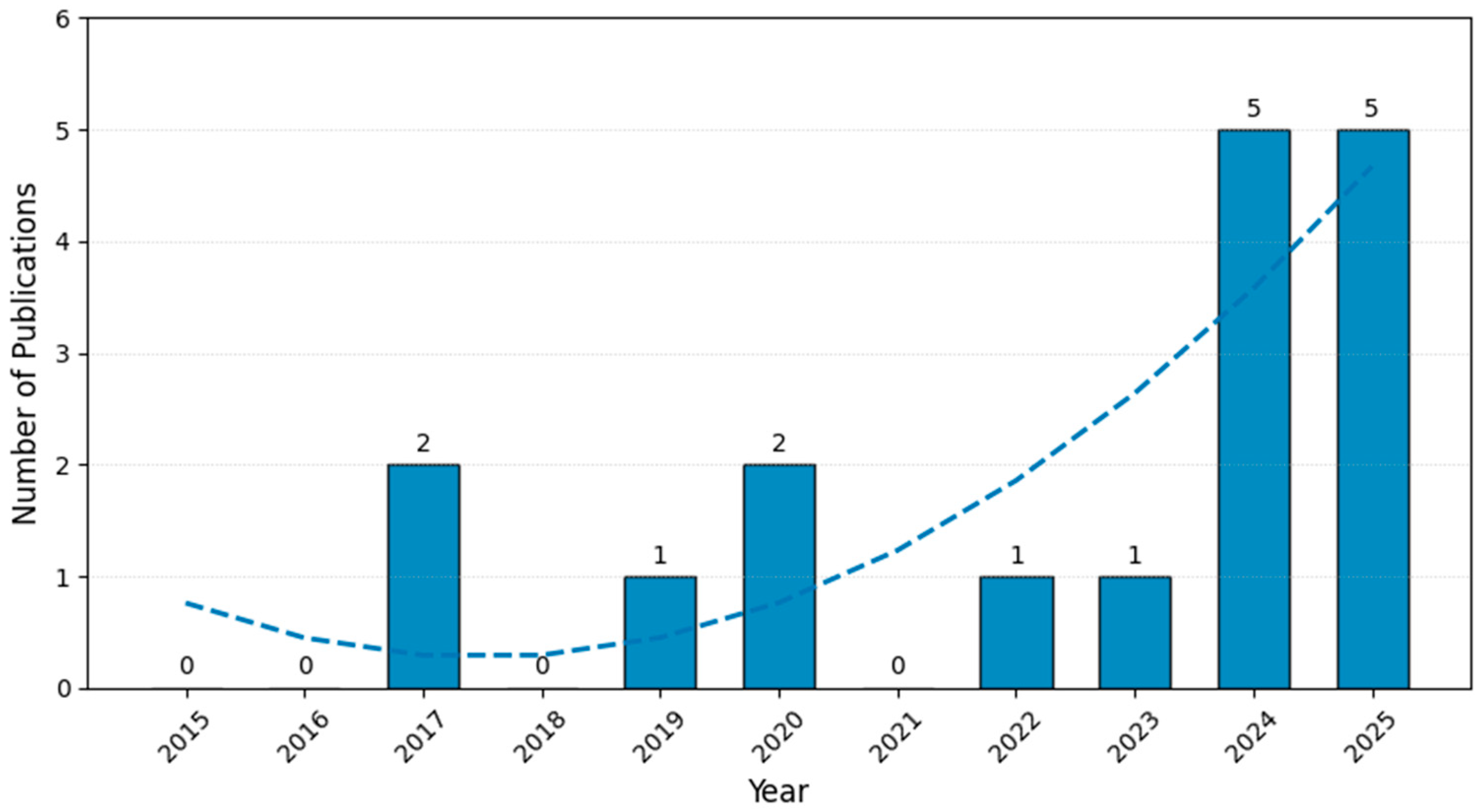

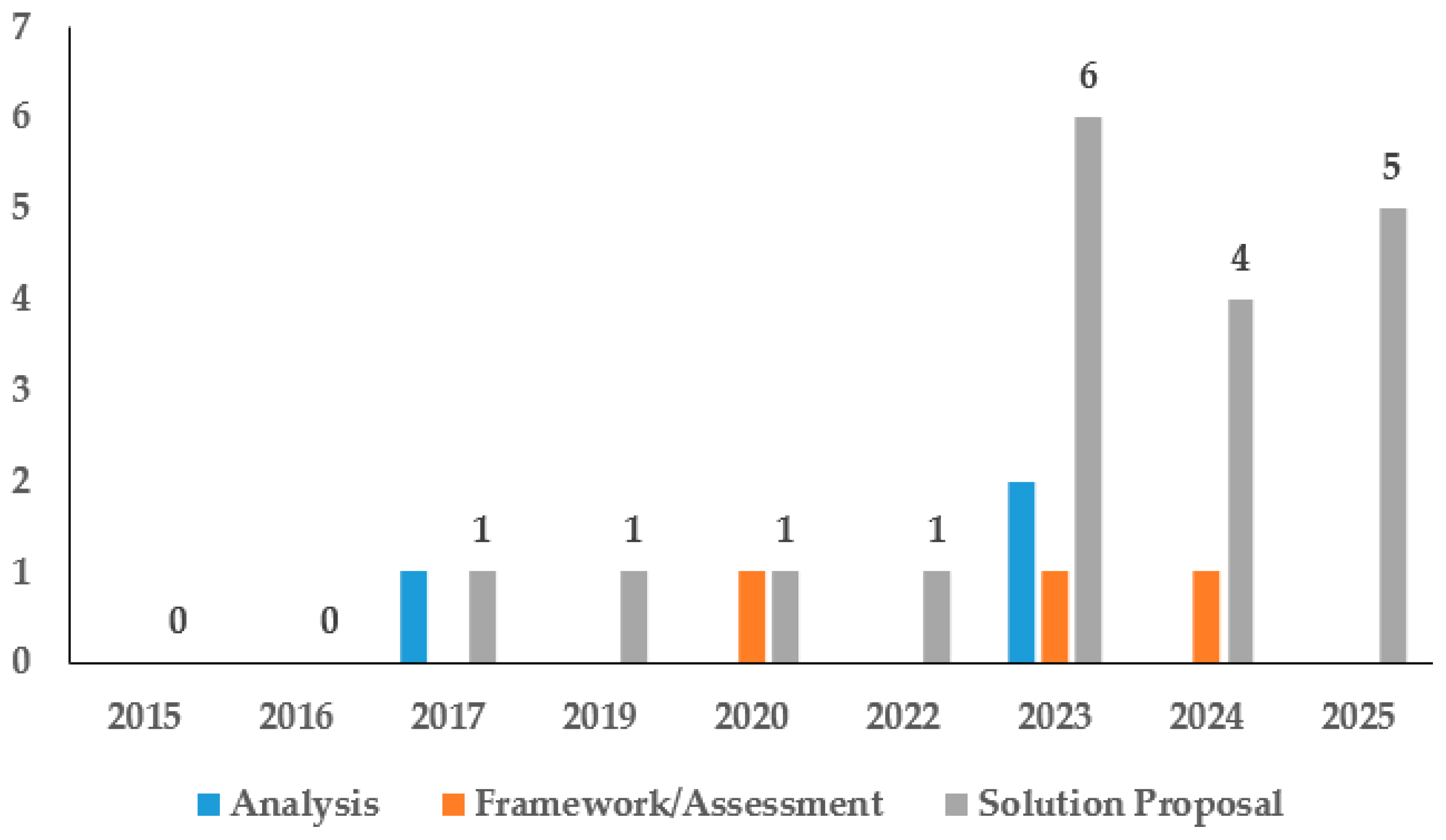

4. Results of the Mapping

4.1. Overview of Selected Studies

4.2. Analysis of Publication Venues and Source Types (RQ1)

4.3. Analysis Based on Technical Challenges (RQ2)

4.3.1. Performance Overhead (Five Papers)

4.3.2. Fragile/Insufficient Container Isolation

4.3.3. Authentication and Authorization Gaps

4.4. Mechanisms, Tools, Frameworks, and Best Practices to Implement PoLP in MSA (RQ3)

- Policy and access control: Techniques focusing on who (identity) and what (action) is permitted.

- Code and configuration hardening: This group focuses on proactive analysis and reduction of the service’s attack surface and reducing its inherent privilege requirements before deployment.

- Runtime and kernel level: Methods concentrating on how services are isolated and restricted at the OS or container runtime level, using low-level technologies to strictly enforce resource limits and prevent unauthorized actions.

- General frameworks and practices: This category contains broader security methodologies, operational tools, and adjacent technologies that support a strong PoLP posture through development lifecycle, monitoring, or specialized applications.

4.5. Analysis Based on Organizational Challenges (RQ4)

- People and culture: This is the most common group, encompassing human factors, mindset, and inter-team dynamics. It highlights that the most persistent challenges are often non-technical and rooted in human behavior and organizational structure.

- Tooling and architecture gaps (ad hoc/legacy): This group focuses on shortcomings in existing technical mechanisms and the lack of mature, standardized, and automated solutions required for the microservices paradigm.

- Process and governance (compliance): This group centers on the formal requirements, mandates, and structural procedures necessary for policy definition, enforcement, and auditing, which are often complicated by the distributed nature of microservices.

- Resource and expertise: This group addresses the tangible limitations in staff, budget, and time, particularly the ongoing effort required to manage security in a microservices environment.

4.5.1. People and Culture

4.5.2. Tooling and Architecture Gaps (Ad Hoc/Legacy)

4.5.3. Process and Governance (Compliance)

4.5.4. Resource and Expertise

4.6. Analysis of Current Gaps and Future Directions (RQ5)

4.6.1. Automation and AI

4.6.2. DevOps/DevSecOps

4.6.3. Education and Training

4.6.4. Dynamic Analysis

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ebad, S.A. Exploring how to apply secure software design principles. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 128983–128993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, H.; Beyer, B.; Blankinship, P.; Lewandowski, P.; Oprea, A.; Stubblefield, A. Building Secure and Reliable Systems: Best Practices for Designing, Implementing, and Maintaining Systems; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.; Fowler, M. Microservices: A Definition of This New Architectural Term. Martin Fowler 2014. Available online: https://martinfowler.com/articles/microservices.html (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- Dragoni, N.; Giallorenzo, S.; Lluch Lafuente, A.; Mazzara, M.; Montesi, F.; Mustafin, R.; Safina, L. Microservices: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. In Present and Ulterior Software Engineering; Mazzara, M., Meyer, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannousse, A.; Yahiouche, S. Securing microservices and microservice architectures: A systematic mapping study. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2021, 41, 100415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Liang, P.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, A.A.; Shahin, M.; Abrahamsson, P.; Nasab, A.R.; Mikkonen, T. Understanding the issues, their causes and solutions in microservices systems: An empirical study. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.01894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venčkauskas, A.; Kukta, D.; Grigaliūnas, Š.; Brūzgienė, R. Enhancing microservices security with token-based access control method. Sensors 2023, 23, 3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, S. Building Microservices: Designing Fine-Grained Systems, 2nd ed.; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Saltzer, J.H. Protection and the control of information sharing in Multics. Commun. ACM 1974, 17, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST SP 800-162; Guide to Attribute Based Access Control (ABAC) Definition and Considerations. National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2014. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/sp/800/162/upd2/final (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- NIST SP 800-207; Zero Trust Architecture. National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, S.; Cao, L.; Zhang, H.; Jia, Z.; Zhong, C.; Shan, Z.; Babar, M.A. Revisiting the practices and pains of microservice architecture in reality: An industrial inquiry. J. Syst. Softw. 2023, 195, 111521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.A.; Budgen, D.; Brereton, P. Evidence-Based Software Engineering and Systematic Reviews; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, K.; Vakkalanka, S.; Kuzniarz, L. Guidelines for conducting systematic mapping studies in software engineering: An update. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2015, 64, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ebad, S.A.; Darem, A.A.; Abawajy, J.H. Measuring software obfuscation quality—A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 99024–99038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebad, S.A.; Alhashmi, A.; Amara, M.; Miled, A.B.; Saqib, M. Artificial intelligence-based software as a medical device (AI-SaMD): A systematic review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, S.; English, K.V.; Butler, K.R.B.; Enck, W. 5GAC-Analyzer: Identifying over-privilege between 5G core network functions. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks (WiSec ’24); ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bufalino, J.; Di Francesco, M.; Aura, T. Analyzing microservice connectivity with Kubesonde. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering (ESEC/FSE 2023); ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 2038–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suneja, S.; Kanso, A.; Isci, C. Can container fusion be securely achieved? In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM Workshop on Container Security (ContainerSec ’20); ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, V.; Davidson, D.; De Carli, L.; Jha, S.; McDaniel, P. CIMPLIFIER: Automatically debloating containers. In Proceedings of the 11th Joint Meeting on Foundations of Software Engineering (ESEC/FSE ’17); ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbadini, M.; Facchinetti, D.; Rossi, M.; Oldani, G.; Paraboschi, S. NatiSand: Native code sandboxing for JavaScript runtimes. In Proceedings of the 38th ACM/SIGAPP Symposium on Applied Computing (SAC ’23); ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, V.; Niddodi, C.; Mohan, S.; Jha, S. New directions for container debloating. In Proceedings of the 2017 Workshop on Forming an Ecosystem Around Software Transformation (FEAST ’17); ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermabon-Bobinnec, H.; Gholipourchoubeh, M.; Bagheri, S.; Majumdar, S.; Jarraya, Y.; Pourzandi, M.; Wang, L. ProSPEC: Proactive security policy enforcement for containers. In Proceedings of the Twelfth ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy (CODASPY ‘22), Baltimore, MD, USA, 24–27 April 2022; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.; Lee, S.; Porras, P.; Yegneswaran, V.; Shin, S. Secure inter-container communications using XDP/eBPF. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2023, 31, 934–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, A.; Datta, P.; Bates, A. Workflow integration alleviates identity and access management in serverless computing. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference (ACSAC 2020); ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Udayakumar, S.K.; Laudya, R.; Pandey, P.; Sheth, A. Dynamic secret injection for microservices in the cloud. In Proceedings of the 2025 8th International Conference on Information and Computer Technologies (ICICT 2025); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budigiri, G.; Baumann, C.; Truyen, E.; Joosen, W. Elastic cross-layer orchestration of network policies in the Kubernetes stack. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2025, 22, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samonte, M.J.C.; Aparize, J.E.R.; Geronimo, J.M.; Oriño, C.C. Implementing zero trust security in microservice architecture of electronic health record. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Computer Systems (ICCS); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunathilake, K.; Ekanayake, I. K8s Pro Sentinel: Extend secret security in Kubernetes cluster. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Information Technology Research (ICITR), Colombo, Sri Lanka, 5–6 December 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei Nasab, A.; Shahin, M.; Raviz, S.A.H.; Liang, P.; Mashmool, A.; Lenarduzzi, V. An empirical study of security practices for microservices systems. J. Syst. Softw. 2023, 198, 111563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamipoor, M.; Ghavamnia, S.; Polychronakis, M. Confine: Fine-grained system call filtering for container attack surface reduction. Comput. Secur. 2023, 132, 103325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y. Cordon: Enhancing security through kernel-level control in containerized computing environments. Comput. Secur. 2025, 158, 104644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shimol, L.; Lavi, D.; Klevansky, E.; Brodt, O.; Mimran, D.; Elovici, Y.; Shabtai, A. Detection of compromised functions in a serverless cloud environment. Comput. Secur. 2025, 150, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Kim, J.; Pawana, I.W.A.J.; You, I. Enhancing cloud-native DevSecOps: A zero trust approach for the financial sector. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2025, 93, 103975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.Y.; Chekole, E.G.; Ochoa, M.; Zhou, J. On the security of containers: Threat modeling, attack analysis, and mitigation strategies. Comput. Secur. 2023, 128, 103140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Gupta, R.; Jadav, D.; Tanwar, S.; Kumar, N.; Shabaz, M. Proxy smart contracts for zero trust architecture implementation in decentralised oracle networks based applications. Comput. Commun. 2023, 206, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casola, V.; De Benedictis, A.; Mazzocca, C.; Orbinato, V. Secure software development and testing: A model-based methodology. Comput. Secur. 2024, 137, 103639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Dhanaraj, R.K.; Ali, M.A.; Balaji, P.; Alharbi, M. Transfer fuzzy learning enabled Streebog cryptographic substitution permutation based zero trust security in IIoT. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 81, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, W.; Liu, M.; Shore, M.; Jiang, F. Zero trust cybersecurity: Critical success factors and a maturity assessment framework. Comput. Secur. 2023, 133, 103412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, D.A.; Davidson, D.; Bardas, A.G. MisMesh: Security issues and challenges in service meshes. In SecureComm 2020; Park, N., Sun, K., Foresti, S., Butler, K., Saxena, N., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Kim, B.; Nam, J. Optimus: Association-based dynamic system call filtering for container environments. J. Cloud Comput. 2024, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Kubernetes Authors. Kubernetes Documentation. 2025. Available online: https://kubernetes.io/docs/home/ (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- Pressman, R.S.; Maxim, B.R. Software Engineering: A Practitioner’s Approach, 9th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, R.; Ai, B.; Lian, Z.; Zeng, L.; Niyato, D.; Peng, Y. Deep reinforcement learning for energy efficiency maximization in RSMA-IRS-assisted ISAC system. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 18273–18278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| Is the study’s purpose clearly established in the introduction? | Yes/No |

| Is the chosen research method/design suitable for the study’s aims? | Yes/No |

| Are the results and findings presented unambiguously? | Yes/No |

| Are the study’s findings interpreted and discussed appropriately? | Yes/No |

| Section 1: Paper Information | |

|---|---|

| Title | Title of the study |

| Author | Author name(s) |

| Type | Journal, Conference, Workshop, or Symposium |

| Year | The year of the study |

| Section 3: Data Extraction | |

| Data Extraction Item | Considered RQ |

| Category (analysis, proposal, review, case study, etc.) | RQ2 |

| Objective (objectives/aims of the study) | RQ2, RQ5 |

| PoLP mechanisms (security mechanisms, tools, frameworks, or best practices proposed or used) | RQ3 |

| Validation (verification and validation techniques used) | RQ2 |

| Technical challenges (list the technical difficulties in PoLP implementation) | RQ1 |

| Organizational/operational challenges (non-technical factors discussed (e.g., security culture and human-centered factors) | RQ4 |

| Identified gaps/future directions (explicitly stated research gaps or limitations) | RQ5 |

| Data analysis (whether quantitative, qualitative, mixed, or not applicable) | RQ2 |

| Domain/platform (domains or platforms applicable for the proposed solution) | (Contextual) |

| Library | Discovered Studies | Inaccessible Studies | Repeated Studies | Exclusive Studies | Primary Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACM | 26 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 9 [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] |

| IEEE | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 [28,29,30,31] |

| Science Direct | 53 | 0 | 0 | 43 | 10 [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] |

| Springer | 32 | 18 | 0 | 12 | 2 [42,43] |

| Taylor and Francis | 21 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 |

| Others (Science Open, Scopus, Semantic Scholar, and Web of Science) | 7 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Total | 144 | 21 | 5 | 93 | 25 |

| ID | Cite | Year | Type | Publisher | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS (1) | [19] | 2024 | C | ACM | 4 |

| PS (2) | [20] | 2023 | C | ACM | 4 |

| PS (3) | [21] | 2019 | W | ACM | 4 |

| PS (4) | [22] | 2017 | C | ACM | 4 |

| PS (5) | [23] | 2023 | S | ACM | 4 |

| PS (6) | [24] | 2017 | W | ACM | 3 |

| PS (7) | [25] | 2022 | C | ACM | 4 |

| PS (8) | [26] | 2023 | J | ACM | 4 |

| PS (9) | [27] | 2020 | C | ACM | 4 |

| PS (10) | [28] | 2025 | C | IEEE | 4 |

| PS (11) | [29] | 2025 | J | IEEE | 2 |

| PS (12) | [30] | 2024 | C | IEEE | 2 |

| PS (13) | [31] | 2024 | C | IEEE | 4 |

| PS (14) | [32] | 2023 | J | Science Direct | 4 |

| PS (15) | [33] | 2023 | J | Science Direct | 2 |

| PS (16) | [34] | 2025 | J | Science Direct | 4 |

| PS (17) | [35] | 2025 | J | Science Direct | 4 |

| PS (18) | [36] | 2025 | J | Science Direct | 4 |

| PS (19) | [37] | 2023 | J | Science Direct | 3 |

| PS (20) | [38] | 2023 | J | Science Direct | 4 |

| PS (21) | [39] | 2024 | J | Science Direct | 4 |

| PS (22) | [40] | 2023 | J | Science Direct | 4 |

| PS (23) | [41] | 2023 | J | Science Direct | 4 |

| PS (24) | [42] | 2020 | C | Springer | 4 |

| Venue | URL | Freq. |

|---|---|---|

| Computers &Security | https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/computers-and-security (accessed on 25 January 2026). | 6 |

| European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering (ESEC/FSE) | https://www.esec-fse.org/index (accessed on 25 January 2026). | 2 |

| # | Technical Challenge | Studies | Freq. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Performance Overhead | [23,34,37,42,43] | 5 | 20% |

| 2 | Fragile/Insufficient Container Isolation | [21,23,33,34] | 4 | 16% |

| 3 | Authentication and Authorization Gaps | [19,30,32,40] | 4 | 16% |

| 4 | Service-to-Service Communication | [19,32,37] | 3 | 12% |

| 5 | Integration with Legacy/Monolithic Systems | [29,36,41] | 3 | 12% |

| 6 | Verification Limitations | [24,33,43] | 3 | 12% |

| 7 | Configuration and Secrets Management | [19,31,32] | 3 | 12% |

| 8 | Traditional/Perimeter-Based Security Insufficiency | [26,30,41] | 3 | 12% |

| 9 | General Overhead and Integration Complexity | [20,22,41] | 3 | 12% |

| 10 | Poor Visibility/Logging and Monitoring | [20,25,32] | 3 | 12% |

| Mechanism Category | Sub-Category | Freq. | % | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy and Access Control | Zero Trust | 11 | 44% | [20,26,27,28,29,30,31,36,40,41,42] |

| RBAC | ||||

| Dynamic Standards International (DSI) | ||||

| Service Mesh | ||||

| Kubesonde | ||||

| General Security Frameworks and Practices | K8s Operators | 10 | 40% | [21,25,31,32,36,37,38,39,40,43] |

| DevSecOps/SecDevOps | ||||

| Secure Software Development | ||||

| Distributed Ledger | ||||

| Blockchain | ||||

| Smart Contracts | ||||

| Code and Configuration Hardening | Debloating | 5 | 20% | [19,22,24,33,37] |

| Threat Modeling | ||||

| Static/Program Analysis | ||||

| Runtime and Kernel Level | Extended Berkeley Packet Filter (eBPF) | 3 | 12% | [23,34,43] |

| Seccomp | ||||

| Sandboxing |

| Organizational Challenge | Sub-Category | Studies | Freq. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| People and culture [19,21,22,23,26,28,30,32,38,40,41,42,43] (56%, n = 14) | Security Awareness and Training | [19,21,22,30,32,38,42,43] | 8 | 32% |

| Cultural and Organizational Barriers | [19,28,32,41] | 4 | 16% | |

| Speed vs. Security Conflict | [23,26,40] | 3 | 12% | |

| Cross-Team Coordination/Collaboration Gaps | [19,20,40] | 3 | 12% | |

| Tooling and architecture gaps (ad hoc/legacy) [20,21,22,24,25,27,28,29,30,31,33,34,39] (52%, n = 13) | Manual Configuration Burden/Errors | [25,31] | 2 | 8% |

| Inadequate/Legacy Policy Mechanisms | [27,29] | 2 | 8% | |

| Ad Hoc/Non-Standardized Solutions | [24,25,33,34,39] | 5 | 20% | |

| Insecure Defaults/Packaging | [20,22] | 2 | 8% | |

| Third-Party Trust Issues | [21] | 1 | 4% | |

| Need for Dynamic Control Management | [34] | 1 | 4% | |

| Industry-Specific Security Needs (EHR) | [30] | 1 | 4% | |

| Process and governance (compliance) [19,20,26,29,30,32,36,43] (32%, n = 8) | Governance and Regulatory Compliance | [19,29,30,32,36,43] | 6 | 24% |

| Policy Enforcement Complexity/Visibility | [20,26,32] | 3 | 12% | |

| Resource and expertise [19,28,32,35,37,42,43] (28%, n = 7) | Operational Overhead and Expertise | [28,35,37,42] | 4 | 16% |

| Resource Constraints/Cost | [19,32,43] | 3 | 12% |

| Research Gap/Research Direction | Sub-Category | Studies | Freq. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automation and AI [19,21,26,28,29,31,38,39] (32%, n = 8) | Overcome manual review difficulty | [19,21,31,39] | 4 | 16% |

| Less attention paid to auto-discover dependencies and detect policy misconfigurations | [26] | 1 | 4% | |

| AI-assisted secret management | [28] | 1 | 4% | |

| Integration into DevOps/DevSecOps [22,28,30,34,35,39] (24%, n = 6) | Integrating security models and tools like Cordon into existing DevOps workflows | [22,34,35,39] | 4 | 16% |

| Adopting DevSecOps Practices | [28,30] | 2 | 8% | |

| Education and Training [32,38,39,40,41,43] (24%, n = 6) | Knowledge/Expertise Gaps | [32,41] | 2 | 8% |

| Training developers in policy design, risk-based security thinking, and generally encourage collaboration and education | [40,43] | 2 | 8% | |

| Limited Security Awareness | [39] | 1 | 4% | |

| Dynamic Analysis [22,24,25,28,33] (20%, n = 5) | Overcoming limitations of dynamic analysis, including those used in debloating methods | [24,33] | 2 | 8% |

| Tackles the Key Challenge of Runtime Enforcement in Large-Scale | [25] | 1 | 4% | |

| Combining Static and Dynamic Analysis | [22] | 1 | 4% | |

| Dynamic analysis to reduce exposure risk | [28] | 1 | 4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ebad, S.A.; Amara, M. The Principle of Least Privilege in Microservices: A Systematic Mapping Study. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031495

Ebad SA, Amara M. The Principle of Least Privilege in Microservices: A Systematic Mapping Study. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031495

Chicago/Turabian StyleEbad, Shouki A., and Marwa Amara. 2026. "The Principle of Least Privilege in Microservices: A Systematic Mapping Study" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031495

APA StyleEbad, S. A., & Amara, M. (2026). The Principle of Least Privilege in Microservices: A Systematic Mapping Study. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031495