Simulation-Driven Build Strategies and Sustainability Analysis of CNC Machining and Laser Powder Bed Fusion for Aerospace Brackets

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Component and Material Description

- A conventionally manufactured bearing bracket using CNC machining from Al 7175-T7351, a high-strength aluminum alloy frequently used in the aerospace sector.

- A topology-optimized bearing bracket designed for LPBF using Scalmalloy® (APWORKS GmbH, Taufkirchen, Germany), a high-performance Al-Mg-Sc alloy developed for additive manufacturing.

2.2. Build Preparation and LPBF Strategies

- A single bracket was printed per build cycle;

- The orientation was optimized using Siemens NX (version 2412, Siemens Digital Industries Software, USA) to minimize unsupported overhangs and thermal gradients;

- Atlas3D (Atlas 3D, Inc., Plymouth, Indiana) thermal simulations validated the build orientation, ensuring acceptable distortion levels and no risk of recoater collisions;

- This strategy was designed to mimic common industrial practices in aerospace, where dimensional tolerances and certification requirements take precedence over throughput.

- Nesting of three brackets within the available build volume;

- Optimization of the layout in Siemens NX to ensure minimal inter-part thermal interference;

- Atlas3D simulations were again used to assess distortion risks and thermal behaviour under multi-part conditions;

- This setup reflects a production-oriented strategy where economies of scale are sought without compromising part integrity.

2.3. Sustainability Assesment

- Cradle-to-Gate: For CNC machining, this covered the casting and rolling of the Al 7175-T7351 billet, followed by the machining operations. For LPBF, this included ingot production, intermediate forming (e.g., rolling or wire drawing), and gas atomisation to produce the Scalmalloy® powder;

- Gate-to-Gate: For CNC, this encompassed machine operation (cutting, tool changes, idle phases), tooling usage, and chip handling. For LPBF, this included machine energy consumption during build and idle phases, shielding gas consumption, unpacking, sieving and reuse of unprocessed powder, as well as removal of support structures;

- Post-Processing: For both routes, relevant thermal and surface finishing operations were included. For CNC, this comprised deburring and surface finishing. For LPBF, post-processing included heat treatment, stress relief, and optional machining of critical interfaces;

- End-of-Life Recycling: For CNC, this reflected recovery of the aluminum chips that substitute primary aluminum production. For LPBF, this accounted for reuse of unprocessed powder as well as recycling of failed builds and supports.

2.4. Cost Analysis

- Material cost (CM) = material cost per kg × mass of the part;

- Data preparation cost (CDP) = data preparation time × engineer hourly rate;

- Machine setup cost (MSC) = time × (machine hourly rate + labour rate);

- Laser melting cost (LMC) (deposition cost (CD)) = deposition time × machine hourly rate;

- Recoating cost (CR) = recoating time × machine hourly rate;

- Cooldown cost (CC) = cooldown time × machine hourly rate;

- Unloading cost (CU) = unloading time × (machine hourly rate + labour rate);

- Separation and post-processing cost (CS) = separation time × (labour rate + system cost);

- Other process costs (CP) = total process time × energy cost per hour + consumables cost;

- Support removal (SR) = time × staff salary per hour.

3. Results

3.1. LPBF Build Preparation and Simulation

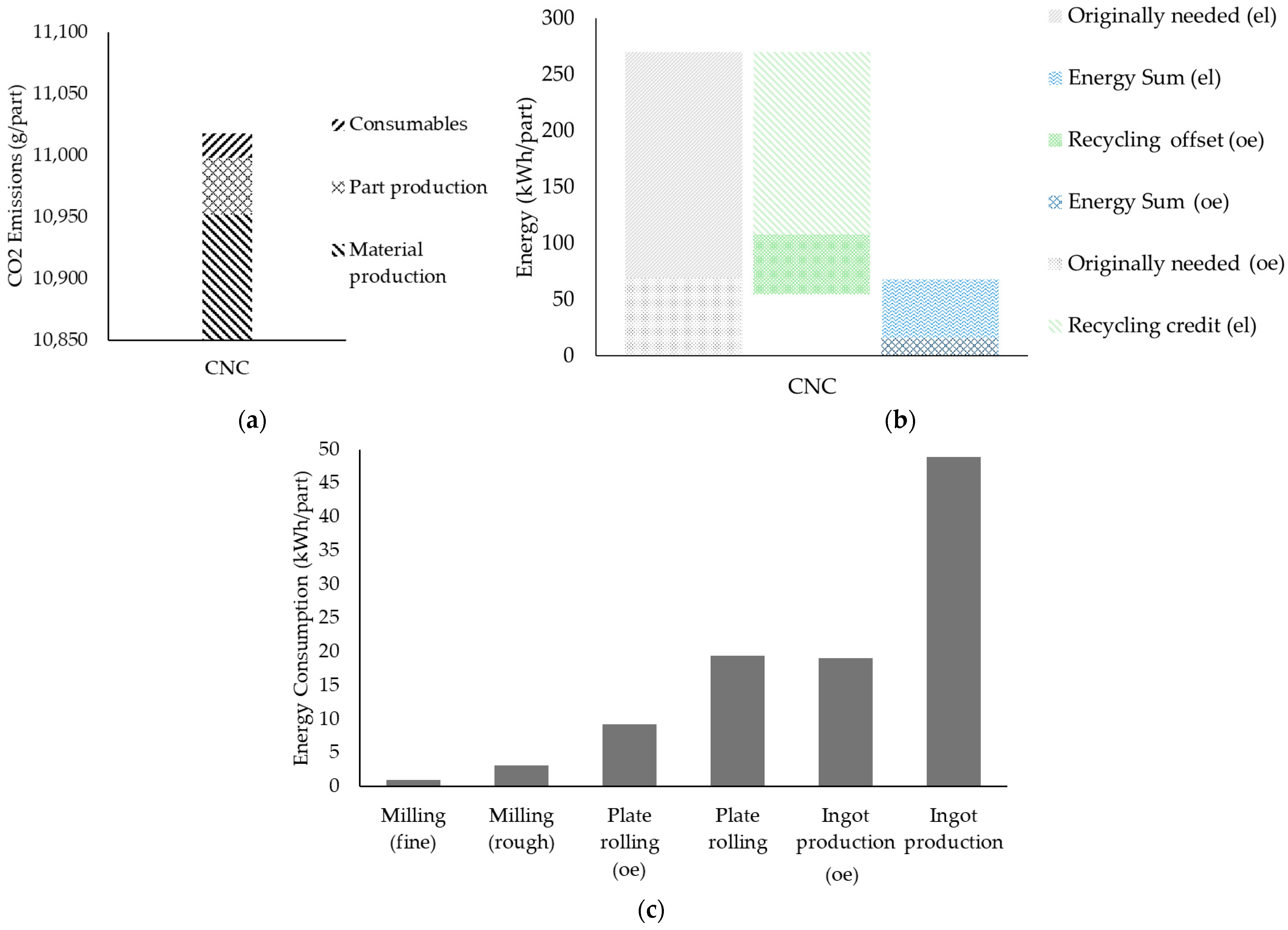

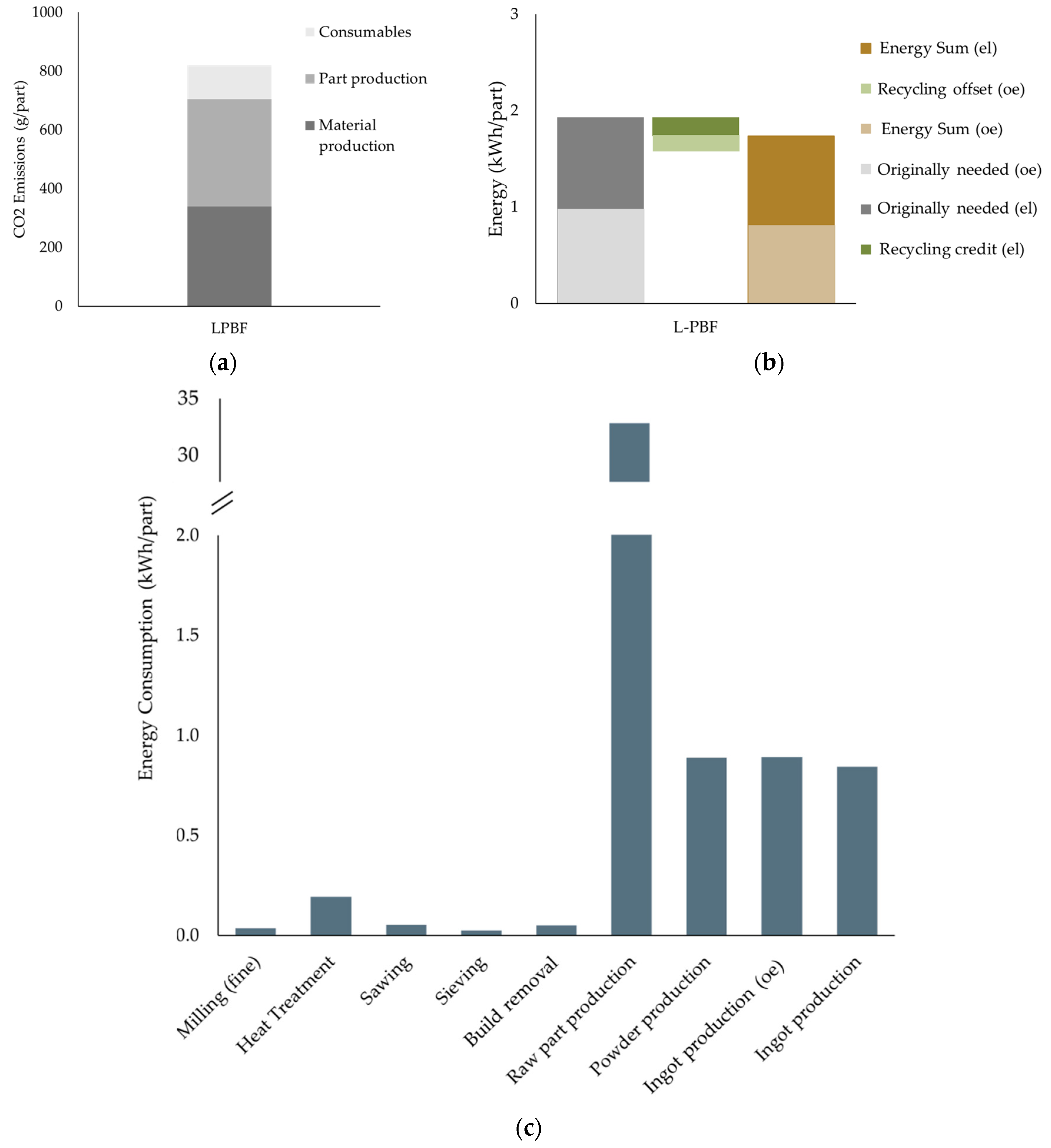

3.2. Sustainability Analysis

3.3. Cost Assesment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNC | Computer Numerical Control |

| LPBF | Laser Powder Bed Fusion |

| B2F/BTF | Buy-to-Fly Ratio |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| LCA | Lifecycle Assessment |

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| DfAM | Design for Additive Manufacturing |

| A320 | Airbus A320 Aircraft |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| CM | Material Cost |

| CT | Tooling Cost |

| Cmach | Machining Cost |

| CL | Labour Cost |

| CLt | Total Labour Cost |

| COHt | Total Overhead Cost |

| ECt | Electricity Cost Total |

| CDP | Data Preparation Cost |

| MSC | Machine Setup Cost |

| CBS | Build Setup Cost |

| CD | Deposition |

| LMC | Laser Melting Cost |

| CR | Recoating Cost |

| CC | Cooldown Cost |

| CU | Unloading Cost |

| CS | Separation And Post-Processing Cost |

| CP | Other Process Costs |

| SR | Support Removal |

| STL/.stl | Stereolithography File Format |

| CLI/.cli | Common Layer Interface File Format |

| PEF | Primary Energy Factor |

| el | Electricity (Final Energy) |

| oe | Primary Energy Equivalent |

| Aj | Activity Data |

| EFj | Emission Factor |

| Rp0.2 | Yield Strength at 0.2% Offset |

| UTS | Ultimate Tensile Strength |

| TO | Topology Optimization |

| PBF-LB | Powder Bed Fusion—Laser Beam |

References

- Ferreira, B.T.; de Campos, A.A.; Casati, R.; Gonçalves, A.; Leite, M.; Ribeiro, I. Technological capabilities and sustainability aspects of metal additive manufacturing. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 9, 1737–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisario, A.; Kazarian, M.; Martina, F.; Mehrpouya, M. Metal additive manufacturing in the commercial aviation industry: A review. J. Manuf. Syst. 2019, 53, 124–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecheter, A.; Tarlochan, F.; Kucukvar, M. A Review of Conventional versus Additive Manufacturing for Metals: Life-Cycle Environmental and Economic Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargioti, N.; Karavias, L.; Gargalis, L.; Karatza, A.; Koumoulos, E.P.; Karaxi, E.K. Physicochemical and Toxicological Properties of Particles Emitted from Scalmalloy During the LPBF Process. Toxics 2025, 13, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spierings, A.B.; Dawson, K.; Voegtlin, M.; Palm, F.; Uggowitzer, P.J. Microstructure and mechanical properties of as-processed scandium-modified aluminium using selective laser melting. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 65, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathish, K.; Kumar, S.S.; Magal, R.T.; Selvaraj, V.; Narasimharaj, V.; Karthikeyan, R.; Sabarinathan, G.; Tiwari, M.; Kassa, A.E. A Comparative Study on Subtractive Manufacturing and Additive Manufacturing. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 6892641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, L.S.R.; Srikanth, P.J. Evaluation of environmental impact of additive and subtractive manufacturing processes for sustainable manufacturing. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 3054–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusateri, V.; Hauschild, M.Z.; Kara, S.; Goulas, C.; Olsen, S.I. Quantitative sustainability assessment of metal additive manufacturing: A systematic review. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 49, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, W.S.; Wanderley, R.F.F.; Gioia, M.M.; Gouvea, F.C.; Gonçalves, F.M. Additive or subtractive manufacturing: Analysis and comparison of automotive spare-parts. J. Remanuf. 2022, 12, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.K.; Taminger, K.M.B. A decision-support model for selecting additive manufacturing versus subtractive manufacturing based on energy consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 1316–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faludi, J.; Baumers, M.; Maskery, I.; Hague, R. Environmental Impacts of Selective Laser Melting: Do Printer, Powder, Or Power Dominate? J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, S144–S156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gao, M.; Li, L.; Ma, Z.; Liu, C. Emergy-based environmental impact evaluation and modeling of selective laser melting. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 115, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, R.; Bashiri, B.; Lopes, S.I.; Hussain, A.; Maurya, H.S.; Vilu, R. Sustainable Additive Manufacturing: An Overview on Life Cycle Impacts and Cost Efficiency of Laser Powder Bed Fusion. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenti, P.; Puccio, D.; Semeraro, Q.; Colosimo, B.M. A techno-economic approach for decision-making in metal additive manufacturing: Metal extrusion versus single and multiple laser powder bed fusion. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 9, 185–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J. Comparative Life Cycle Inventory of CNC Machining and Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. Master’s Thesis, Aalto University, Otaniemi, Espoo, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sargioti, N.; Koumoulos, E.P.; Karaxi, E.K. Integrating Orientation Optimization and Thermal Distortion Prediction in LPBF: A Validated Framework for Sustainable Additive Manufacturing. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puukko, P.; Hepo-oja, L.; Vatanen, S.; Kaipainen, J.; Mäkinen, M.L.; Lindqvist, M. Case study of the environmental impacts and benefits of a PBF-LB additively manufactured optimized filtrate nozzle. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pusateri, V.; Olsen, S.I.; Kara, S.; Hauschild, M.Z. Life Cycle Assessment of metal additive manufacturing: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the Sustainability in Energy and Buildings: Research Advances; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 8, pp. 1–9. Available online: http://nimbusvault.net/publications/koala/SEBRA/606.html (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Diniz, S.B.; Paula, A.D.S.; Brandão, L.P. Temperature and annealing time influences on cross-rolled 7475-T7351 aluminum alloy. Rev. Mater. 2022, 27, e20220167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; p. 20.

- ISO_14044-2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; pp. 1–55.

- ISO 14067:2018; Greenhouse Gases—Carbon Footprint of Products—Requirements and Guidelines for Quantification. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; p. 46.

- ISO 14064-1:2018; Greenhouse Gases—Part 1: Specification with Guidance at the Organization Level for Quantification and Reporting of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Report, O. Estimates of Electricity Requirements for the Recovery of Mineral Commodities, with Examples Applied to Sub-Saharan Africa; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2011.

- Ashby, M.F. Materials and the Environment: Eco-Informed Material Choice; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaras, C.A.; Dascalaki, E.G.; Psarra, I.; Cholewa, T. Primary Energy Factors for Electricity Production in Europe. Energies 2023, 16, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). National Emissions Reported to the UNFCCC and to the EU Greenhouse Gas Monitoring Mechanism; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024; Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/external/national-emissions-reported-to-the-6 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- European Environment Agency. (27 June 2025; Modified 6 November 2025). Greenhouse Gas Emission Intensity of Electricity Generation, Country Level. EEA. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/greenhouse-gas-emission-intensity-of-1-1762418255/greenhouse-gas-emission-intensity-of (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Ehmsen, S.; Conrads, J.; Klar, M.; Aurich, J.C. Environmental impact of powder production for additive manufacturing: Carbon footprint and cumulative energy demand of gas atomization. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 82, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atia, M.; Khalil, J.; Mokhtar, M. A Cost Estimation Model for Machining Operations; an Ann Parametric Approach. J. Al-Azhar Univ. Eng. Sect. 2017, 12, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser Aluminum. Contained Metal Value by Alloy. Available online: https://www.kaiseraluminum.com/contupload/uploads/Kaiser_Contained_Metal_Value_By_Alloy.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Nicolaou, P.; Thurston, D.L.; Carnahan, J.V. Machining quality and cost: Estimation and tradeoffs. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2002, 124, 840–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Automated Cost Estimation for 3-Axis CNC Milling and Stereolithography Rapid Prototyping. Master’s Thesis, The University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2005. Available online: https://mspace.lib.umanitoba.ca/items/95f33eda-f12a-4f92-9d39-d9fcf2baa4f9 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- ISO/ASTM 52911-3-2023; Additive Manufacturing—Design Part 3: PBF-EB of Metallic Materials. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Gruber, S.; Grunert, C.; Riede, M.; López, E.; Marquardt, A.; Brueckner, F.; Leyens, C. Comparison of dimensional accuracy and tolerances of powder bed based and nozzle based additive manufacturing processes. J. Laser Appl. 2020, 32, 032016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikinmaa, L. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Conventional and Additive Manufacturing: Case Paper Machine Part Module. Master’s Thesis, LUT University, Lappeenranta, Finland, 2024; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, H.; Mokhtarian, H.; Coatanéa, E.; Museau, M.; Ituarte, I.F. Comparative environmental impacts of additive and subtractive manufacturing technologies. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 65, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, R. Aircraft Structural Brackets Using Additive Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the Thermoplastic Composites Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 22–24 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R.; Riddle, M.; Graziano, D.; Warren, J.; Das, S.; Nimbalkar, S.; Cresko, J.; Masanet, E. Energy and emissions saving potential of additive manufacturing: The case of lightweight aircraft components. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiris, K. Auto—Aero: Technology Transfer Assessment for Light Weighting; ThermoPlastic Composites Application Center: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, A.; Ferreira, B.; Leite, M.; Ribeiro, I. Environmental and Economic Sustainability Impacts of Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Study in the Industrial Machinery and Aeronautical Sectors. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 42, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alloy Series | Heat Treatment | Rp0.2 (Mpa) | UTS (Mpa) | Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al7175 | T7351 * [19] | 435 | 505 | 13 |

| Scalmalloy | 325 °C for 4 h | 480–500 | 510–530 | 13–16 |

| Variable | Conventional Manufacturing (CNC) | Metal Additive Manufacturing (LPBF) | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

|  | ||

| Dimensions (l, w, h) | 210, 60, 65 | 150, 60, 65 | mm |

| Volume (final part) | ~155 | ~55 | cm3 |

| Mass (final part) | ~430 | ~140 | g |

| Volume (billet) | 1114.5 | - | cm3 |

| Mass (billet) | 3120.6 | - | g |

| Supports mass (1st strategy) | - | 3.18 | g |

| Supports mass (2nd strategy) | - | 9.57 | g |

| Material | Al 7175 | Scalmalloy | - |

| Density | 2.8 | 2.67 | g/cm3 |

| Material cost | 3 | 250 | €/kg |

| Buy-to-fly ratio | 1:7.33 | 1:1.2 | - |

| Parameter | 1st Strategy: Minimal Thermal Distortions—1 Part per Build | 2nd Strategy: Maximize Build Volume Efficiency—3 Parts per Build |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Consumption per Part | 40 kWh | 37 kWh |

| CO2 Emissions per Part | 1122 g CO2 | 820 g CO2 |

| Material Efficiency (Buy-to-Fly Ratio) | 1:1.2 | 1:1.2 |

| Build Time | 15 h | 42 h |

| Dimensional Accuracy and Distortion Risk | Minimized (validated with simulations) | Acceptable (validated with simulations) |

| Metric | CNC Machining | LPBF—Strategy 1 (1 Part/Build) | LPBF—Strategy 2 (3 Parts/Build) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 Emissions per Part | ~11,000 g | 1122 g (90% reduction) | 820 g (92.5% reduction) |

| Energy Consumption per Part | >100 kWh | 40 kWh (60% reduction) | 37 kWh (63% reduction) |

| Material Efficiency (Buy-To-Fly) | 1:7 | 1:1.2 (65% improvement) | 1:1.2 (65% improvement) |

| Metric | Approximate Value |

|---|---|

| Weight Reduction | 136.25 kg |

| Fuel Savings/Year | 25,888 L |

| CO2 Savings/Year | 77.6 tons |

| Lifetime Fuel Savings | 776,640 L |

| Lifetime CO2 Savings | 2328 tons |

| Total Cost Savings | EUR 559,181 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sargioti, N.; Karaxi, E.K.; Azar, A.S.; Koumoulos, E.P. Simulation-Driven Build Strategies and Sustainability Analysis of CNC Machining and Laser Powder Bed Fusion for Aerospace Brackets. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031360

Sargioti N, Karaxi EK, Azar AS, Koumoulos EP. Simulation-Driven Build Strategies and Sustainability Analysis of CNC Machining and Laser Powder Bed Fusion for Aerospace Brackets. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031360

Chicago/Turabian StyleSargioti, Nikoletta, Evangelia K. Karaxi, Amin S. Azar, and Elias P. Koumoulos. 2026. "Simulation-Driven Build Strategies and Sustainability Analysis of CNC Machining and Laser Powder Bed Fusion for Aerospace Brackets" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031360

APA StyleSargioti, N., Karaxi, E. K., Azar, A. S., & Koumoulos, E. P. (2026). Simulation-Driven Build Strategies and Sustainability Analysis of CNC Machining and Laser Powder Bed Fusion for Aerospace Brackets. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031360