1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide [

1], generating an enormous socio-health burden through both direct healthcare costs and indirect losses related to disability, reduced functional capacity, and long-term dependency [

2]. In the European Union, CVD continues to account for the highest mortality figures, representing roughly one third of all deaths [

3]. The economic consequences are equally severe, with recent estimates indicating more than one million working years lost each year and total expenditures surpassing €280 billion annually when healthcare costs, productivity losses, and informal care are taken into account [

3]. Within this burden, ischemic heart disease and acute heart failure with systolic dysfunction remain the conditions with the greatest clinical and economic impact [

4].

Despite advancements in acute-phase diagnostic and therapeutic care over recent years [

5], preventive strategies remain insufficient to curb the incidence and recurrence of cardiovascular events. In this context, cardiac rehabilitation (CR) has emerged as a first-line secondary prevention intervention and an essential component of comprehensive patient education [

6]. CR programs are currently defined as multifactorial, multidisciplinary, and comprehensive therapeutic interventions aimed at improving quality of life, reducing complications, and decreasing mortality by optimizing cardiovascular prognosis [

6]. Extensive evidence supports the effectiveness of CR in reducing morbidity and mortality [

7]. Thus, in patients with ischemic heart disease, CR has been associated with a 26% reduction in all-cause mortality, a 26–34% reduction in cardiovascular mortality per year, an 18% reduction in readmissions, and a 33% improvement in return-to-work rates [

8]. Among patients with congestive heart failure, CR participation is linked to a 30% reduction in total readmissions and up to a 40% reduction in readmissions due to decompensated heart failure [

7], while in patients with valvular disease, mortality is reduced by 61% (relative) and 4.2% (absolute), with a 44% decrease in hospitalizations [

9].

Multiple endpoints have been used to quantify improvement after CR, including functional field tests such as the 6-minute walk test [

10] and patient-reported health-related quality-of-life questionnaires [

11]. However, most benefits of CR programs are ultimately mediated through improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) [

12]. In this regard, CRF is typically assessed via peak oxygen consumption (VO

2peak) obtained through cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET), which reflects the integrated capacity of the cardiovascular, respiratory and muscular systems to uptake, transport and utilize oxygen during maximal exertion [

13]. VO

2peak is widely regarded as the gold-standard biomarker of functional capacity, since it simultaneously encompasses pulmonary ventilation, cardiac output, oxygen delivery through vascular function, and mitochondrial oxidative efficiency at the skeletal muscle level [

14]. In practice, a 1-MET increase (3.5 mL/kg/min) following CR is associated with a 11–17% reduction in all-cause mortality and major cardiovascular events [

15]. As such, VO

2peak is considered the primary clinical endpoint and the reference metric for evaluating functional improvement in CR.

However, despite the strong evidence supporting CR efficacy, a well-documented and clinically relevant observation persists: the response to training is markedly heterogeneous across patients. While many individuals achieve clinically meaningful gains in VO

2peak, others show only marginal improvement or no improvement at all [

16]. This inter-individual variability has been partially attributed to baseline factors such as age [

17], lower initial functional capacity [

18], and the presence of comorbidities such as diabetes [

19]. However, current knowledge remains insufficient to explain why some patients benefit substantially whereas others do not. As a result, the ability to stratify patients according to their likelihood of improving VO

2peak at baseline remains a major unresolved challenge, and the development of tools for risk stratification and outcome anticipation could support more precise clinical decision-making and resource allocation within CR programs [

20].

Recent years have witnessed growing interest in the application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques within CR to support clinical decision-making and optimize program delivery. Previous Machine Learning (ML)-based studies in CR have mainly focused on predicting program adherence [

21], intention to participate [

22], return-to-work status [

23], or functional outcomes assessed through field tests such as the 6-minute walk distance [

24]. Although these approaches have demonstrated promising predictive performance, most models rely predominantly on demographic, clinical, or behavioral variables and are not specifically designed to predict individual physiological adaptation to exercise-based rehabilitation [

25]. In parallel, wearable sensors combined with ML algorithms are increasingly being explored in rehabilitation contexts to enable continuous monitoring of physiological, biomechanical, and activity-related parameters [

24]. Recent systematic reviews have highlighted the potential of wearable-based ML systems to support rehabilitation training through objective tracking, real-time feedback, and personalized adaptation of exercise programs [

26].

Nevertheless, objective changes in cardiorespiratory fitness assessed by CPET, particularly improvements in VO

2peak, remain largely unexplored as a primary prediction target, despite their well-established prognostic and clinical relevance [

25]. Addressing this gap represents a critical opportunity to enhance the translational value of AI in CR by enabling early identification of patients who are more or less likely to achieve meaningful improvements in aerobic capacity. Therefore, the aim of this study is to develop an AI-based system capable of stratifying patients according to their likelihood of achieving clinically meaningful improvement following CR, while simultaneously identifying the most relevant modifiable baseline variables associated with treatment success. In addition, we propose a simulation-based Clinical Decision Support System (CDSS) that enables clinicians to explore how manipulation of these modifiable parameters may influence rehabilitation outcomes.

3. Methods

3.1. Cardiac Rehabilitation Intervention Protocol

Enrolled patients participated in an eight-week, group-based outpatient CR program supervised by a physiotherapist. The intervention combined structured exercise training with patient education delivered by a multidisciplinary team. Participants attended one weekly 1-hour group education session focusing on lifestyle risk factor management, psychological health, and dietary counseling, led by healthcare professionals from different disciplines.

Participants completed three supervised exercise sessions per week, each lasting approximately 90 min. Sessions included a standardized warm-up followed by resistance training targeting major upper- and lower-limb and core muscle groups (2–3 sets of 10 repetitions at 30–40% of one-repetition maximum for upper limbs and 50–60% for lower limbs), and aerobic training performed on a cycle ergometer or treadmill.

During the first four weeks, aerobic exercise consisted of continuous training at the heart rate corresponding to the ventilatory thresholds, with progressive intensity increase. During the final four weeks, two weekly sessions incorporated interval training consisting of 1-minute bouts at 85% of VO2peak interspersed with 1-minute active recovery at 70% of VO2peak, for a total duration of 30–35 min, while the remaining session continued with continuous aerobic training.

Finally, each session concluded with a brief cool-down including stretching and relaxation exercises. Participants were additionally encouraged to perform at least 30 min of daily physical activity during their leisure time.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

Missing values accounted for 0.82% of all data points (57 out of 6832). Missingness was mainly concentrated in HbA1c (11 values), while all remaining variables presented very low and sporadic missing rates, with no systematic pattern across predictors. No variable was excluded due to missingness, and all missing values were imputed to preserve data integrity. Continuous features were imputed using the median of the corresponding variable, while categorical features were imputed using the statistical mode. All categorical predictors were encoded numerically prior to model training to ensure full compatibility with machine-learning algorithms. Feature scaling was applied selectively, using Z-score normalization only for models whose performance is affected by variable magnitude, while the remaining algorithms were trained using the original unscaled features. Importantly, all normalization and scaling procedures were embedded within the cross-validation workflow, such that scaling parameters were always estimated exclusively from the training folds and subsequently applied to the corresponding validation folds.

3.3. Machine Learning Models and Evaluation Strategy

All ML classifiers were trained using the full set of 56 baseline variables, with the primary objective of stratifying patients into responders and non-responders following CR intervention. A representative set of linear and non-linear classifiers was evaluated, including a Decision Tree (DT) and a Random Forest (RF) as tree-based models, and a Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machines with linear kernel (SVM–Linear), Support Vector Machines with radial basis function kernel (SVM-RBF), and a Polynomial Logistic Regression (PLR) of degree two. Tree-based models were trained on raw (unscaled) variables due to their robustness to monotonic transformations of input features. In contrast, LR, PLR and both SVM-based models were trained within a pipeline including Z-score normalization, in order to standardize the contribution of each feature and prevent dominance by variables with larger numerical ranges [

27].

Hyperparameters were fixed following a conservative configuration for each classifier in order to preserve model stability, reproducibility, and fair comparability across algorithms given the limited sample size. Specifically, the Random Forest was trained with 500 trees and class weighting; the SVM-RBF model used and ; the linear SVM used a linear kernel; logistic regression employed L1 regularization with the liblinear solver; the polynomial logistic model used degree two; and the Decision Tree used the Gini impurity criterion without depth restriction. This strategy was adopted to prioritize generalizability and to avoid additional degrees of freedom that could lead to unstable or overly optimistic results.

Furthermore, the robustness and generalizability of the models were verified using a stratified 10-fold cross-validation scheme. This methodology plays a crucial role in preventing overfitting and ensuring a more accurate estimation of performance [

28]. In this approach, the complete dataset was partitioned into ten equal-sized folds, ensuring a balanced representation of both outcome groups within each fold. During the validation process, ten iterations were performed such that, in each iteration, nine folds were used for training while the remaining fold served as the test set. This process was repeated until every fold had acted once as the test subset, ensuring that all subjects contributed to both training and evaluation. The results from the ten iterations were then aggregated to obtain the final performance metrics, reported as the mean classification Accuracy (Acc), Sensitivity (Se), Specificity (Sp) and F1-score (F1) across folds. Regarding classification, a fixed probability threshold of 0.5 (default decision rule of the classifiers) was applied consistently across all folds, without any data-driven optimization.

Finally, it is worth noting that all experiments were implemented in Python (version 3.12) using widely adopted machine-learning libraries, including pandas (v2.3.3), NumPy (v2.3.5), SHAP (v0.50.0), scikit-learn (v1.7.2), matplotlib (v3.10.7), and seaborn (v0.13.2).

3.4. Feature Importance and Dimensionality Reduction

Given the high dimensionality of the baseline feature space (56 variables), and the need to enhance both interpretability and clinical applicability, feature importance was evaluated using two complementary approaches. First, a Random Forest-based importance analysis was conducted, using the model’s capacity to capture non-linear interactions and rank variables according to the decrease in prediction performance when feature perturbation is introduced. This approach allows quantifying how strongly each variable contributed to the classification task, providing a global relevance profile without imposing linearity or monotonicity assumptions [

29]. Features with consistently low importance across iterations were considered weak contributors to discrimination between responders and non-responders.

To complement this analysis, Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) were employed to obtain a more interpretable and locally consistent measure of feature contribution. SHAP is a game-theoretic framework that decomposes model output into additive contributions of each feature, ensuring local accuracy and enabling both global and subject-level interpretability [

30]. Unlike traditional importance metrics, SHAP identifies which predictors are most influential, but also whether their effect increases or reduces the probability of response. This dual insight is clinically relevant, as it highlights modifiable physiological targets for intervention and exposes mechanistic patterns that may underlie heterogeneous patient outcomes [

30]. The final feature selection was defined as the intersection of the two importance rankings. Only variables consistently identified among the top predictors by both RF impurity-based importance and SHAP-based importance were retained for the reduced model.

Following these analyses, classification models were retrained with models described in

Section 3.3 using only the most relevant predictors identified through RF importance and SHAP contribution. This reduction strategy aimed to evaluate whether a more compact and clinically explainable feature subset could preserve (or minimally reduce) model performance when compared to full-variable classification. Moreover, the use of reduced models prioritizes transparency and clinical actionability, enabling rehabilitation specialists to concentrate on the baseline parameters with the greatest influence on response, while simultaneously reducing overfitting risk.

3.5. Web-Based Clinical Decision Support Prototype

To facilitate the translational use of the proposed ML framework in routine clinical practice, a web-based prototype of a CDSS was developed. The application was implemented using a Python Flask backend connected to a lightweight HTML and Bootstrap frontend, and integrates directly with the final classification model derived from the feature importance and dimensionality reduction analyses. The backend exposes a set of endpoints that load the trained classifier and the corresponding preprocessing objects (e.g., Z-score normalizer), ensuring that the data transformation applied in the web tool is identical to that used during model training and validation. Clinicians can input or update baseline values for the selected modifiable predictors through an interactive interface composed of numeric fields and slider controls. Upon submission, the Flask server normalizes the inputs, feeds them into the final model, and returns the corresponding binary classification (responder vs non-responder). This design enables real-time estimation of the likelihood of achieving a clinically meaningful improvement in VO2peak for any new patient matching the inclusion profile of the cohort.

Beyond providing a single prediction, the prototype was conceived as an exploratory simulation tool to enhance interpretability and support individualized decision-making. For each patient profile entered in the interface, SHAP explanations are computed to quantify the contribution of each baseline predictor to the predicted probability of response, thus generating a subject-specific explanation vector. These SHAP values are then used to display a graphical representation of the most influential variables, distinguishing those that increase the likelihood of improvement from those that act as limiting factors. Clinicians can iteratively modify selected inputs, resubmit the scenario, and immediately observe how the predicted probability of response and the associated SHAP profile change. In this way, the web-based CDSS functions as a “what-if” simulation environment, linking the underlying AI model to clinically interpretable, modifiable targets, and providing a practical framework to explore how baseline optimization of specific physiological domains could translate into higher chances of success in CR.

4. Results

4.1. Classification Performance Using Machine Learning Models

Table 1 presents the classification performance obtained when training the models using all 56 baseline predictors. Results were computed under a stratified 10-fold cross-validation scheme, reporting the mean and confidence intervals across folds. Among the evaluated classifiers, SVM-RBF achieved the highest performance (F1 = 0.907, Acc = 0.900, Se = 0.933, Sp = 0.869), followed closely by SVM–Linear, which also yielded strong discriminative capacity. PLR algorithm showed competitive behaviour (F1 = 0.892, Acc = 0.892), while LR attained moderate but stable values (F1 = 0.873, Acc = 0.876). Tree-based methods performed comparatively lower, with RF achieving acceptable results (F1 = 0.841, Acc = 0.860) and DT being the least accurate model (F1 = 0.791, Acc = 0.795). Overall, these results indicate that SVM-based methods are the most suitable approach for stratifying intervention success when the full high-dimensional feature set is considered.

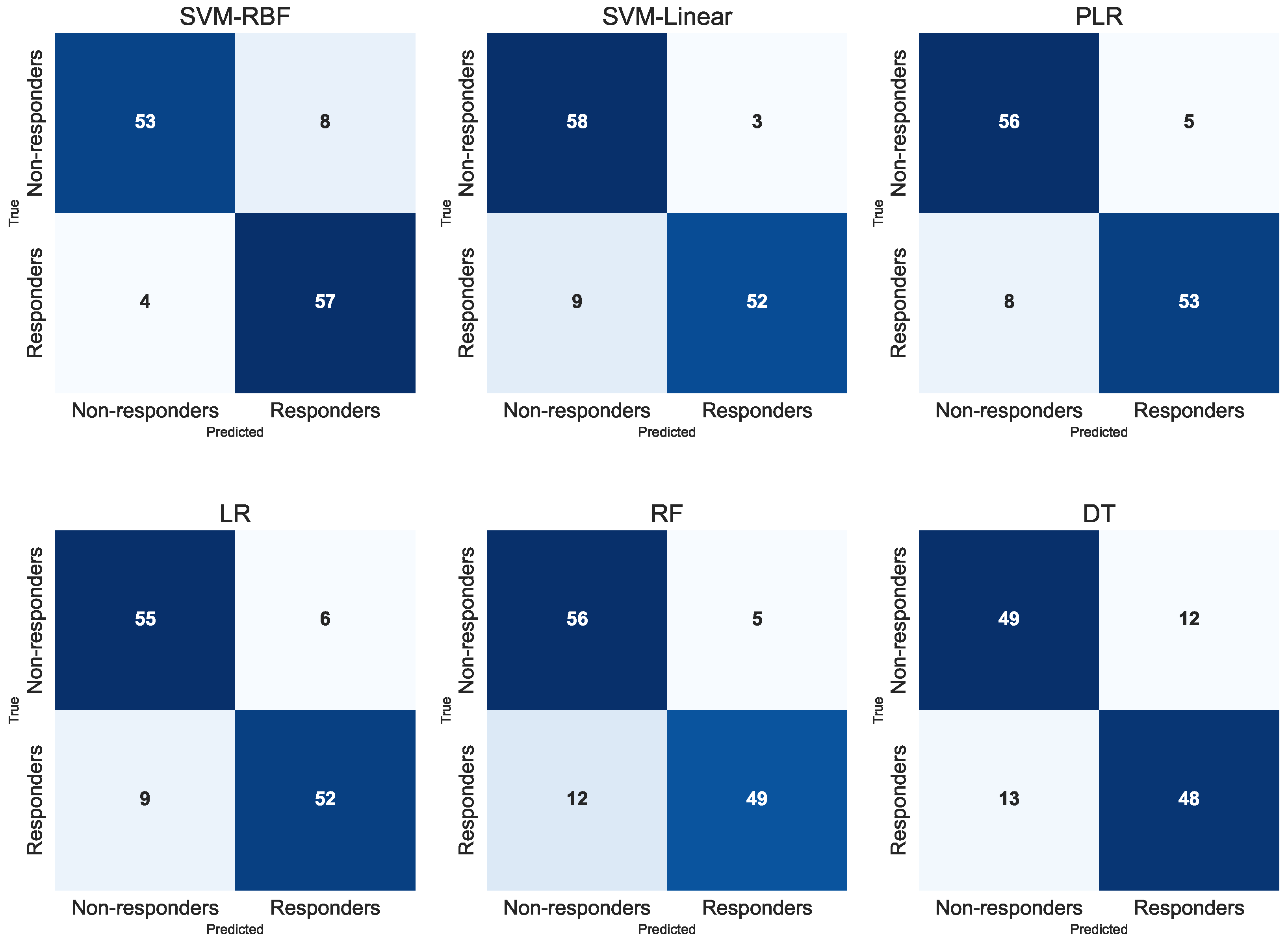

Figure 1 shows the aggregated confusion matrices for all classifiers, generated by pooling the test predictions from the ten folds. In all classifiers, the majority of predictions fall along the diagonal, indicating consistent discrimination between patients who improved and those who did not after CR. Tree-based models (DT and RF) exhibit a more balanced pattern of correct classifications, whereas SVM models demonstrate a higher concentration of true positive and true negative identifications. Logistic-based models also present strong separation between outcome groups, with only a small number of misclassifications in either class. Overall, the aggregated confusion matrices visually confirm the robustness of most models under repeated resampling, reinforcing the results previously obtained through cross-validation metrics.

4.2. Feature Importance and Model Complexity Reduction

Table 2 summarizes the feature-importance rankings obtained with RF and SHAP for the top 15 predictors. As can be observed, there is a high degree of agreement between both methods, as 13 out of the 15 variables appear in the top-15 list of RF and also in the top-15 list of SHAP (87% match rate), although the exact ordering of importance is not identical. The only predictors exclusively highlighted by SHAP are Type II Diabetes (DM2) and HDL Cholesterol (HDLc); while RF uniquely emphasizes peak VO

2 (VO2P) and muscular efficiency at peak exercise (EMus). This substantial overlap supports the robustness of the identified feature subset and suggests that a reduced set of ventilatory, functional and metabolic variables captures most of the discriminative information driving the classification models. To further assess the stability of this feature ranking, the algorithms were additionally evaluated within a stratified cross-validation framework. Feature importance was computed independently in each training fold and subsequently aggregated across folds. The resulting ranking remained highly stable and preserved the same physiological core of predictors, confirming that feature selection was not dependent on a particular data partition.

Based on the convergence aforementioned between the RF and SHAP rankings, a reduced space of characteristics was constructed using exclusively the predictors that appeared in the top-ranked list of both methods. This resulted in a compact set of 13 clinically meaningful baseline variables, which were: handgrip strength (HGr), heart rate at ventilatory threshold 1 (HR1), breathing reserve (BR), VE/VCO2 slope (VeVCO2), chronotropic index (IC), waist–hip ratio (WHR), respiratory exchange ratio at 2 min of recovery (RERA2), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), Myers functional exercise score (Myers), heart rate recovery index (IRFC), repetition maximum (RM), oxygen uptake efficiency slope (OUES), and VO2 at ventilatory threshold 1 (VO2T1). Interestingly, most of these predictors represent modifiable physiological targets, either through exercise training, intensity prescription, nutritional management or progression within the rehabilitation plan, which may support the translational relevance of using this reduced subset for clinical adjustment and individualized intervention simulation.

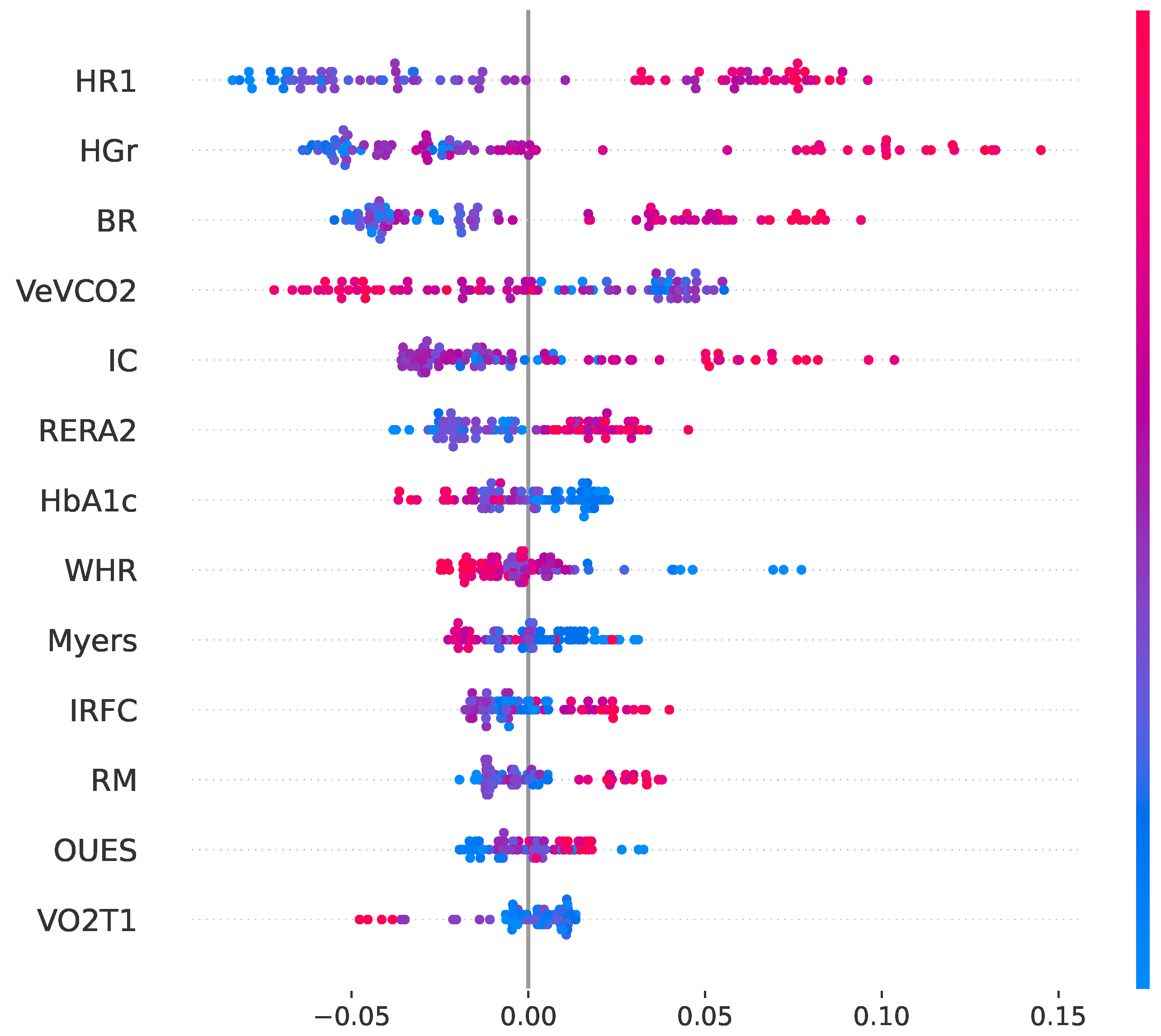

In addition to global importance ranking, a SHAP-based directionality analysis was performed to evaluate how each of the 13 predictors influences the probability of response. The SHAP summary plot (see

Figure 2) demonstrates a predominantly coherent and physiologically plausible pattern. Thus, higher values of HGr, HR1, BR, IC, RERA2, IRFC, RM, and OUES are associated with increased probability of response. In contrast, higher VeVCO2, HbA1c, and WHR are associated with reduced response likelihood. These directional effects are fully consistent with established clinical and physiological knowledge, supporting the interpretability and biological plausibility of the proposed model.

4.3. Classification Performance Using Reduced Feature Subset

After identifying the 13 most influential baseline predictors through convergent RF–SHAP ranking, all classification algorithms were retrained using only this reduced feature space.

Table 3 summarises the 10-fold cross-validated results, reported as averaged values across folds.

Compared with the full-feature configuration (56 variables), the reduced model preserved most of the predictive capability while achieving a substantial dimensionality reduction (–78% of total input space). The SVM-RBF classifier remained the highest performing method across metrics (F1 = 0.88; AUC = 0.96), followed closely by RF model (F1 = 0.85; AUC = 0.95). Although SVM-RBF achieved a more balanced sensitivity–specificity profile, both models maintained strong specificity and sufficiently high sensitivity to support consistent discrimination of responders and non-responders.

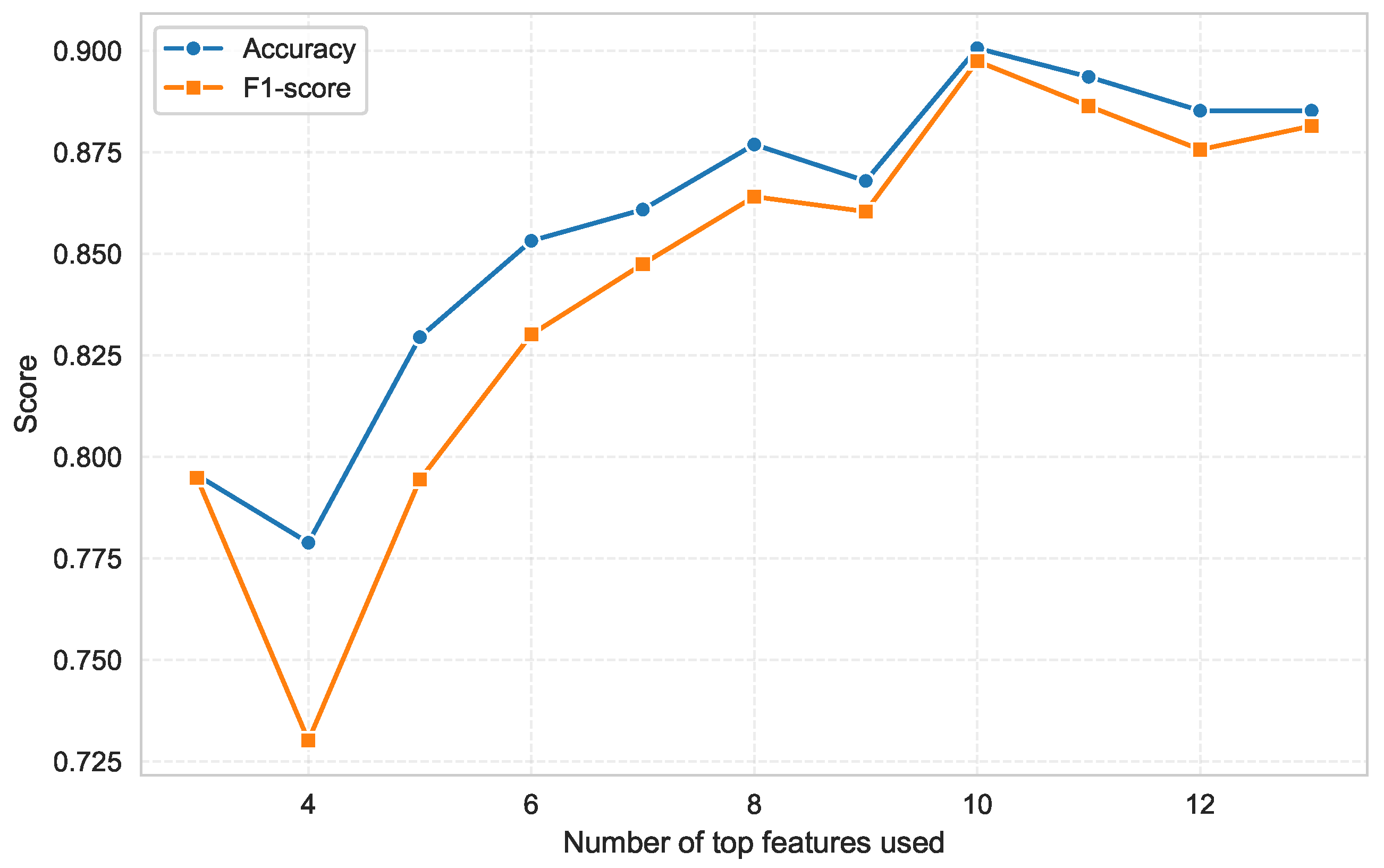

The fact that performance degradation relative to the full feature set was small (<4–5% across metrics) demonstrates that most discriminative information is contained within a compact subset of baseline physiological variables. This interpretation is further supported by the feature sweep illustrated in

Figure 3, where model performance was evaluated using progressively reduced subsets of the top-ranked predictors. This analysis provides an explicit quantitative assessment of how predictive performance evolves as a function of the number of retained features.

Although the RF–SHAP consensus set comprised 13 predictors, this subset was used as an intermediate candidate pool for further optimization rather than as the final model specification. Thus, while classification accuracy and F1-score dropped substantially when only 3–5 features were retained, a sharp performance gain was observed from 6 upward, reaching a clear maximum at 10 variables. Beyond this point, no further improvement was observed, confirming that the optimal trade-off between model complexity and performance is achieved with a limited number of predictors. Notably, using 11–13 predictors did not improve performance and even produced a slight decline, indicating that additional features introduce redundancy rather than additional discriminative value.

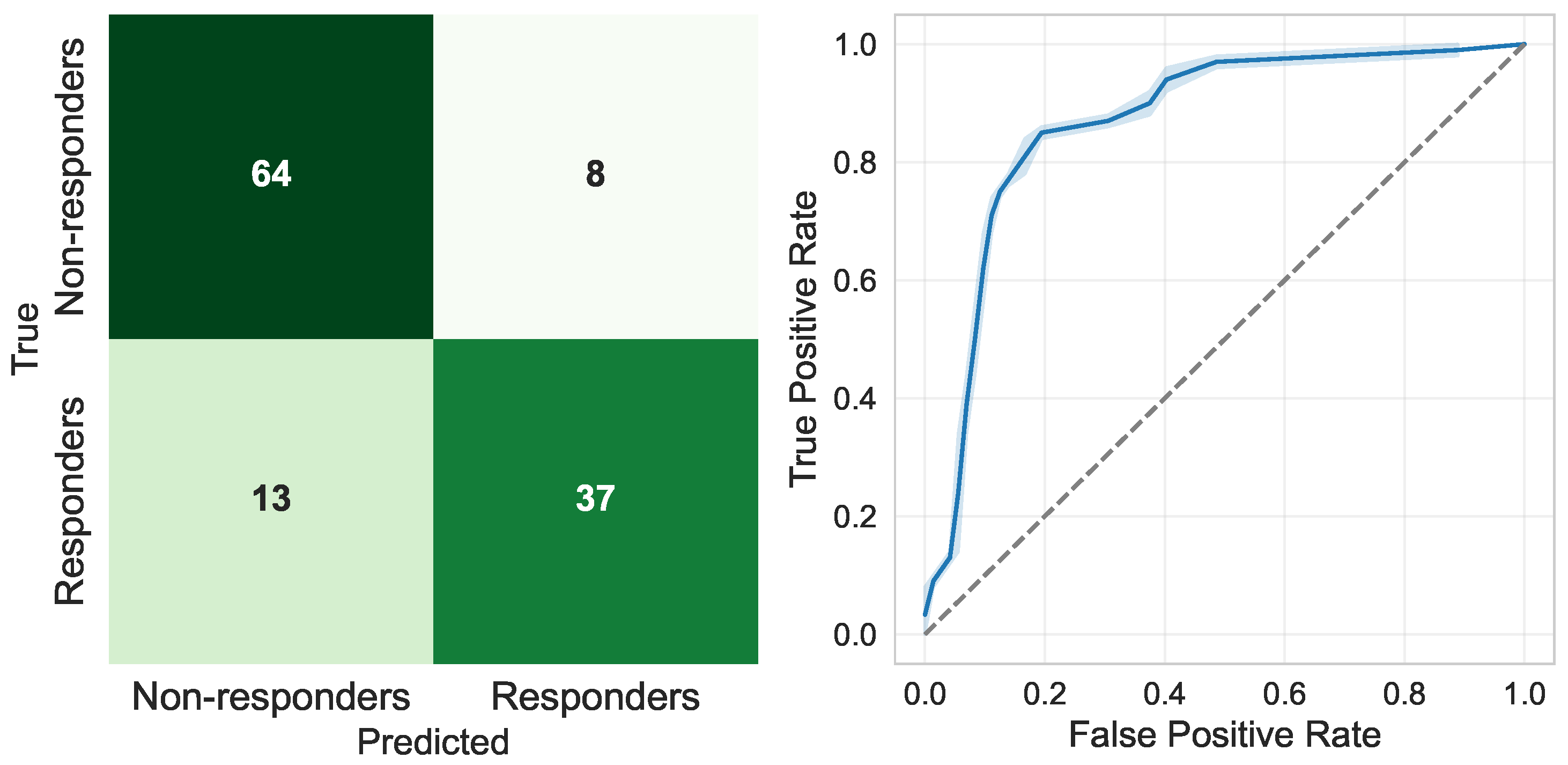

Finally,

Figure 4 illustrates the performance of the final selected model, an SVM-RBF classifier trained exclusively using the top 10 baseline predictors. The aggregated confusion matrix obtained through 10-fold cross-validation (left panel) shows a sensitivity of 0.885 and a specificity of 0.918. This indicates balanced diagnostic behaviour in detecting both responders and non-responders. Moreover, the corresponding ROC curve (right panel) reveals consistently high discrimination, with an area under the curve (AUC) close to 0.96, confirming the strong predictive capacity of this reduced model configuration while maintaining high interpretability and clinical readability.

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis Using a Stricter Responder Definition

To further assess the robustness of the proposed framework, an additional sensitivity analysis was performed using a stricter responder threshold (), following the same methodological pipeline described in the previous sections. Under this definition, the cohort comprised 50 responders and 72 non-responders. The complete analytical workflow, including feature-importance analysis, model training, and performance evaluation, was then applied to this alternative outcome definition.

As shown in

Table 4, eight of the thirteen most influential predictors remained unchanged when applying the stricter responder definition, confirming the stability of the core physiological structure of the model. These common variables mainly reflect ventilatory efficiency, autonomic regulation, muscular strength, and anthropometric profile. In contrast, the variables that lost relevance under the stricter threshold were primarily general metabolic and functional markers, whereas the newly emerging predictors were mainly related to objective respiratory function, oxygenation, and lipid profile. This physiologically coherent shift suggests that while general functional and metabolic status is sufficient to explain minimal improvements, more pronounced functional gains require greater baseline ventilatory reserve and metabolic efficiency.

Using these 13 most relevant predictors, classification performance remained high across all evaluated models. Among them, SVM-RBF again achieved the best overall results, with an accuracy of 0.80, an F1-score of 0.75, and an AUC of 0.88. Although these values are slightly lower than those obtained with the model showed in

Section 4.3, they remain fully comparable and clinically meaningful. In fact, the moderate reduction in performance may reflects the increased clinical difficulty of the prediction task under the stricter outcome definition, rather than a loss of model stability. Importantly, the relative ranking of classifiers was preserved, confirming SVM-RBF as the most suitable model for this framework.

Finally, using SVM-RBF as the best-performing classifier, a performance analysis was conducted as a function of the number of selected predictors. Interestingly, under the stricter responder definition, the optimal performance was achieved using only the top five predictors. This represents a substantial reduction compared with the original analysis, in which ten predictors were required to reach optimal performance. Using this compact five-feature model and a 10-fold cross-validation scheme, the classifier achieved an accuracy of 82.6%, a sensitivity of 74%, a specificity of 89%, an F1-score of 0.76, and an AUC of approximately 0.89 (see

Figure 5). These results demonstrate that a small and physiologically stable subset of predictors is sufficient to achieve high and balanced discrimination performance.

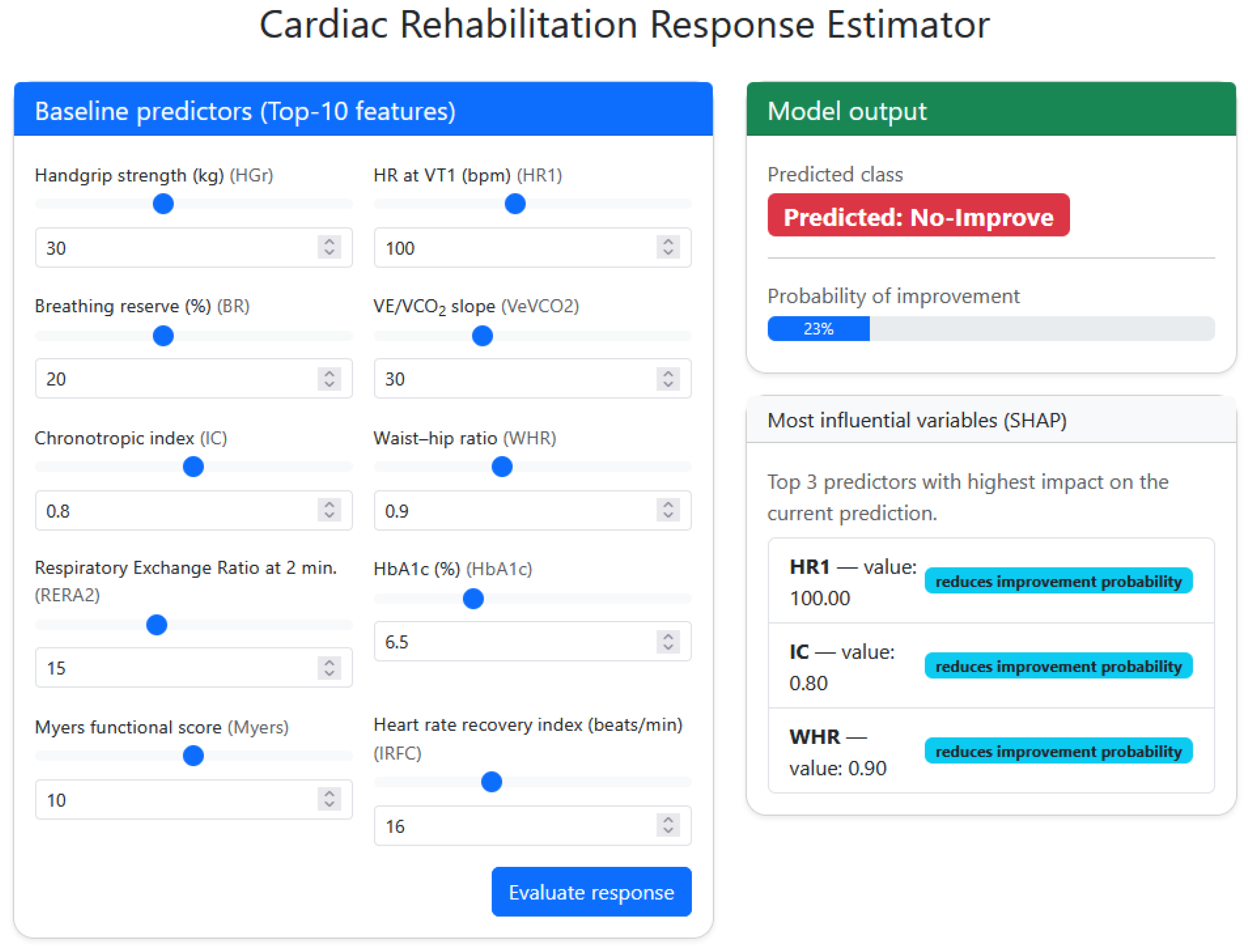

4.5. Clinical Decision-Support Interface for Personalized Prediction

To translate the developed model into a clinically usable format, a web-based decision-support interface capable of estimating CR response from baseline variables was implemented. It should be noted that the presented CDSS corresponds to an in-house research prototype intended to demonstrate methodological feasibility and translational potential, rather than a publicly deployed or clinically certified software platform. The system operates using the final SVM-RBF classifier trained with the top ten predictors identified in the feature-importance analysis (HGr, HR1, BR, VeVCO2, IC, WHR, RERA2, HbA1c, Myers, IRFC). The clinician inputs or adjusts these parameters, via numeric boxes or slider-style controls, and the platform generates an automated classification output indicating whether the patient is likely to improve after CR (Responder) or not (Non-responder).

In addition to the binary output, the tool provides an estimated probability of functional improvement derived from the calibrated SVM decision function . This enables categorical classification, and also continuous risk interpretation, supporting decisions in borderline or uncertain cases.

The interface also integrates SHAP-based explainability to enhance transparency in clinical reasoning. For each patient evaluated, the system computes local SHAP values and displays the three variables with strongest influence on the decision. These features are visually coded as either increasing or reducing improvement probability, indicating which baseline parameters are driving the predicted outcome. Importantly, this design allows clinicians to understand why a given patient is classified as a likely responder or non-responder, and which modifiable factors may be prioritized to favor a better rehabilitation trajectory.

Finally,

Figure 6 shows an example interface output, where entered baseline values lead to a predicted non-responder classification with an estimated 23% improvement likelihood. The SHAP panel highlights HR1, IC and WHR as the dominant negative drivers of the response, suggesting that modulation of these variables may be key targets for intervention.

5. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents one of the first attempts to develop an explainable ML framework for VO

2peak response stratification in CR based exclusively on baseline variables, and to translate this approach into a simulation-based CDSS for individualized rehabilitation planning. Recent reviews of ML applications in CR have highlighted a scarcity of prognostic tools targeting functional response and an almost complete lack of explainable, deployable systems integrated within clinical workflows [

25]. In this context, the proposed framework directly addresses the core clinical question of who will benefit from CR and who will not, enabling early stratification, prioritization of resources, and optimization of rehabilitation planning. Moreover, the integration of SHAP-based interpretability further strengthens the contribution of this work, as it allows transparent identification of the physiological mechanisms most strongly associated with treatment success and reveals modifiable predictors that can be targeted before rehabilitation begins. In this sense, the present framework aligns with the paradigm of precision and personalized medicine, shifting rehabilitation from a uniform protocol toward data-driven, outcome-oriented decision support in which interventions are adapted to the individual profile of each patient rather than the average clinical response [

31].

A clinically relevant observation is that the SVM–RBF classifier preserved almost the same performance after dimensionality reduction from 56 to 10 variables, whereas linear models and tree-based methods experienced a more pronounced decline. This pattern is consistent with the nature of the decision boundary underlying patient response, where the relationship between baseline physiology and rehabilitation outcome is likely non-linear, and there are interaction effects that cannot be captured through additive linear terms. Thus, the RBF kernel is particularly suited to this scenario because it constructs flexible, high-dimensional decision surfaces where complex patterns can be separated even when they are not linearly distinguishable in the input space [

32]. In contrast, decision trees, although non-linear, learn piecewise axis-aligned splits that fragment the feature space and depend strongly on the presence of many parallel predictors. When the dimensionality is reduced, the granularity of these splits decreases, leading to lower stability and degradation of decision boundaries [

33]. However, the SVM–RBF retains a smooth multidimensional margin that generalizes well even after variable reduction, suggesting that the CR response phenotype emerges from non-linear interactions concentrated in a small number of key physiological domains rather than broad distributed information across the full feature set.

The SHAP analysis enabled transparent identification of the physiological domains most strongly associated with rehabilitation response, allowing a clinically interpretable mapping of the model predictors to specific functional mechanisms. To this respect, the fact that only ten variables retained most of the discriminative power suggests that the response to CR is mostly driven by a core cluster of functional mechanisms. Thus, HGr strength and the Myers score reflect overall muscle function and exercise tolerance, both of which are key determinants of the capacity to progressively increase training workload [

34,

35]. Furthermore, ventilatory efficiency markers such as the VeVCO2 slope, BR and IRFC capture the ability to handle metabolic acidosis and ventilatory stress such that patients with efficient gas-exchange kinetics adapt more favorably to aerobic retraining [

36,

37]. Similarly, chronotropic competence (HR1 and IC) and RERA2 reflect autonomic balance and vagal reactivation, both of which condition cardiovascular output during sustained exercise [

38]. Finally, anthropometric and metabolic markers such as WHR and HbA1c represent the substrate of cardiometabolic burden, where patients with central adiposity or impaired glucose control often exhibit delayed aerobic adaptation and blunted VO

2 kinetics [

39]. Taken together, these features delineate a biologically coherent profile in which responders display preserved muscular capacity, ventilatory efficiency, autonomic flexibility, and low metabolic stress, while non-responders tend to accumulate inefficiencies across these systems, ultimately limiting their training adaptation.

At the same time, it is important to consider the clinical context in which these predictors are obtained. The present framework relies on several CPET-derived predictors, which is a natural and physiologically coherent consequence of using VO2peak change as the reference outcome. Since VO2peak obtained from CPET represents the clinical gold standard for the assessment of cardiorespiratory fitness, it is expected that variables derived from the same physiological evaluation provide the most informative and interpretable predictive signal. Accordingly, the proposed model is conceived as a clinical decision-support tool for structured CR programs in which CPET assessment constitutes part of routine clinical practice. In this context, the inclusion of CPET-based variables should be interpreted as a reflection of the intended clinical setting and the objective of maximizing predictive accuracy and physiological interpretability. Nevertheless, broader clinical deployment would benefit from alternative CPET-free prediction strategies. Future research should therefore explore simplified models based on surrogate functional endpoints, such as the 6-minute walk test, submaximal exercise indices, wearable-derived physiological variability, and routinely available clinical parameters. Such approaches would be particularly valuable in low-resource, rural, or underserved settings where access to CPET and structured rehabilitation programs is limited, potentially enabling wider implementation of personalized risk stratification and individualized intervention planning.

Furthermore, these findings support the shift from population-based rehabilitation protocols toward precision-oriented strategies that acknowledge the marked heterogeneity in CR response. By enabling individualized classification of responders and non-responders from baseline data, and by identifying the physiological levers most responsible for treatment success or failure, our framework operationalizes the principles of personalized medicine in a clinically interpretable way. Indeed, rather than assuming a uniform benefit, the model highlights modifiable barriers such as ventilatory inefficiency, autonomic rigidity or metabolic dysregulation, thereby opening the door to guide and tailor intervention planning in line with current guidance on individualized, CPET-anchored exercise prescription [

40,

41]. This is consistent with evidence showing that personalization enhances training efficacy and outperform standardized exercise dosing [

42,

43]. Importantly, explainable ML offers a viable pathway for translating this concept into practice: SHAP-derived attributions provide patient-specific justification for each classification and indicate which variables should be prioritized to improve prognosis [

44]. Aware of this translational need, we additionally developed a functional web-based decision-support prototype, demonstrating how such individualized insights could be deployed in real-time clinical workflows to optimize rehabilitation planning at the patient level.

From an implementation perspective, the proposed CDSS is conceived as a decision-support and simulation framework rather than as an automated decision-making system. The predicted probability of response should be interpreted as a confidence-oriented indicator that complements the binary classification, facilitating individualized reasoning in borderline or uncertain cases. By combining probabilistic output with SHAP-based explanations, clinicians can explore personalized “if–then” scenarios and evaluate how modifying specific baseline parameters may influence the predicted likelihood of improvement. In this way, the tool supports personalized rehabilitation planning, prioritization of modifiable targets, and risk-oriented monitoring strategies, while final clinical responsibility and decision-making always remain with the healthcare professional.

It is worth noting that the present cohort exhibited a pronounced predominance of male participants, a pattern that is commonly reported in cardiac rehabilitation programs [

45,

46]. This sex imbalance represents an important limitation regarding the generalizability of the findings to female populations. To explore the potential influence of sex on the predictors used by the model, an exploratory visual inspection of the selected variables stratified by sex was performed. No evident sex-specific clustering or systematic separation patterns were observed across the analyzed predictors. Although this suggests that the proposed model is not trivially driven by sex-related differences, these observations must be interpreted with caution due to the limited number of female participants. In addition, the cohort only included patients who successfully completed the full 8-week cardiac rehabilitation program. Patients who discontinue rehabilitation or never enroll may differ systematically in clinical severity, psychosocial profile, motivation, or comorbidity burden. Therefore, the present predictive framework primarily reflects the population of CR completers and may not fully generalize to non-adherent or non-participating patients. Taken together, these factors highlight a representativeness limitation of the current cohort. Future studies should prioritize broader and more inclusive recruitment strategies, ensuring adequate female participation and inclusion of partial completers or early dropouts, in order to improve the external validity and clinical applicability of predictive models in CR.

Beyond these representativeness constraints, several additional methodological and translational limitations should be considered when interpreting this work. First, the cohort size was moderate (n = 122) and derived from a single, standardized CR program, which may restrict statistical power for subgroup-level inference and limit generalizability to other clinical settings, patient profiles or program intensities. Even under standardized rehabilitation protocols, multicenter studies naturally introduce variability in patient profiles and implementation contexts, which is essential to evaluate model generalizability. Therefore, future multicenter investigations conducted under harmonized intervention protocols would allow assessment of model robustness across diverse referral patterns, healthcare environments, and real-world clinical conditions, reducing center-specific bias and strengthening the translational reliability of predictive frameworks in CR.

Second, although we implemented a cross-validation scheme, the absence of an external validation cohort prevents confirming model transportability, a key requirement for robust AI deployment in healthcare [

47]. This issue reflects a broader structural limitation in this field, because harmonized, high-resolution CR datasets including CPET-derived variables remain scarce, restricting both large-scale model training and multi-site benchmarking [

25]. Third, while the web-based decision-support tool illustrates the translational potential of the proposed framework, its integration into routine care still requires technical validation, usability assessment, and implementation across diverse rehabilitation environments. Future work should therefore focus on prospective multicenter validation, interoperability with existing hospital information systems, and evaluation of clinical impact when used to guide personalized rehabilitation planning.