1. Introduction

Permanent Magnet Direct Current (PMDC) motors have been used recently in a wide range of applications due to their simplicity and reliability, among other good characteristics. When precise control of speed or torque is required, this type of motor is an excellent option. Its design, without external field windings, makes it easy to maintain and highly efficient. However, attaining an accurate tracking control for speed implicates significant challenges. Varying load conditions and external disturbances lead to nonlinear behavior and complicate the design of robust control systems [

1]. As a result, complicated control techniques are required to achieve good performance. Moreover, the controllers often rely on limited feedback, so the task of achieving precise speed regulation is even more complex [

2].

Recent literature has extensively explored PMDC motor speed control using both classical and advanced control strategies. Classical PID and PI controllers remain widely adopted due to their simplicity, low computational cost, and ease of real-time implementation. For instance, comparative studies in [

3,

4] demonstrate that PID and PI controllers can achieve satisfactory speed regulation under nominal conditions. However, these works also highlight that abrupt reference changes may lead to increased overshoot, higher control effort, and voltage or current peaks, particularly when converter dynamics are not explicitly considered.

To address the robustness limitations of classical controllers, sliding mode control (SMC) has been investigated as an alternative. Some research [

3,

5] shows that SMC can significantly improve robustness against parameter uncertainties and load disturbances in DC motor speed control. Nevertheless, these approaches commonly suffer from chattering phenomena and increased actuator stress, which may reduce hardware lifespan and complicate practical implementation.

Fuzzy logic control (FLC) has also been proposed to overcome modeling uncertainties and nonlinearities. Studies such as [

3,

4,

6] report improved transient behavior and reduced overshoot compared to conventional PID controllers. Despite these advantages, fuzzy-based controllers require expert knowledge for rule-based design and tuning, and their performance may vary across operating conditions, limiting their general applicability in low-cost or real-time systems.

More recent efforts have focused on hybrid and advanced control schemes, including optimized, fractional-order, or estimation-enhanced controllers. For example, [

7,

8] report improved tracking accuracy and disturbance rejection by combining PID structures with optimization algorithms or state-estimation techniques. While these approaches achieve superior performance in complex scenarios, they typically introduce higher computational burden and design complexity, which may hinder their deployment on embedded or real-time platforms.

A wide range of power control devices rely on DC links, which must adapt to varying conditions and provide different voltage levels as needed to meet the requirements of the connected loads. To address these challenges, specialized controllers have been developed based on the concept of current control mode, enabling precise regulation and efficient operation under dynamic load conditions. In ref. [

9], several techniques using artificial intelligence are employed to control the speed of a DC motor; however, details on the implementation of the DC power converter are not included. On the other hand, in [

10], the proposal lacks information about the required voltage source to achieve this behavior. Metaheuristic optimization algorithms for tuning the gains for the DC motor speed control system using PID and fractional order PID controllers were introduced in [

11,

12], respectively. The response significantly improved the time and frequency responses, but it does not include a converter to generate the DC signal required to achieve the indicated level of precision. A sensorless speed control technique for a DC motor, employing an extended Kalman filter in conjunction with a Mamdani fuzzy logic, is discussed in [

13]. The exhibited results are also excellent, due to its cost effectiveness and efficiency, but the applied control voltage is not obtained from a DC-to-DC converter. The authors of [

14] deal with the problem of controlling the speed of a DC motor using a state-feedback linearization technique combined with a nonlinear second-order sliding mode super-twisting algorithm and were able to track the velocity and reject external disturbances. However, step changes demand high currents and high control effort. A good topology for driving a DC motor using several DC sources connected in series is presented in [

15]. Here, the main purpose is to reduce current ripples from chopper circuits, but the absence of the filter components that inherently appear in DC converters causes the voltage to jump rapidly and to large values, which can provoke switch overheat and stress. A complete set of topologies for DC–DC converters is discussed in [

16]. Here, a definition of converter classes is introduced, which allows for classifying the converters according to behavior parameters.

Without considering the characteristics of the DC–DC converter, both classical and advanced controllers may require significant effort to accurately follow reference trajectories. A thorough analysis of the converter’s dynamic limits and operating speed can greatly assist in selecting the optimal converter–controller pair to achieve superior performance. This is one of the main advantages of this proposal.

In this work, Bézier curves are utilized to manage transitions between speed levels safely and efficiently. Because the physical implementation involves the motors’ inertial rotational speed, step changes are not achievable. Considering such discontinuities in the control stage would require significant effort, which could saturate the actuator. Therefore, Bézier curves are considered an excellent option for optimal control and can be used to demonstrate improved driver performance [

17]. Bézier curves are not only used for stress reduction but also play a key role in selecting the most suitable controller–converter combination used as an electric motor drive system (EMDS) for PMDC motor speed control. One of the key advantages of DC–DC converters is their relatively simple construction, which facilitates the tracking of speed trajectories. However, their behavior is typically associated with a specific operating point, and when operating conditions change, the system must be adapted, modified, or employ a highly demanding controller to handle variations.

The voltage-tracking capability of DC–DC converters operating as the EMDS is investigated using the duty cycle and DC gain as control variables. The selected converters represent three distinct voltage conversion characteristics: a negative-gain topology, a positive-gain topology, and a quadratic-gain topology. The output voltage is determined by the control signal provided by the Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID) controller, a simple and efficient control strategy, which is based on the speed-tracking error. With this methodology, it is possible to verify the stringent dependency between the controller and the converter topology. The main contribution of this work is the simulation and real-time implementation of a complete electric motor drive system for PMDC motor speed regulation. Bézier curve-based voltage trajectory planning effectively mitigates current and voltage peaks during speed tracking, while merit figures provide a quantitative basis for validating the effectiveness of the proposed methodology compared to conventional step transitions.

This paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 introduces the DC motor model and defines the problem.

Section 3 provides a comparison of DC-to-DC converters. The entire control scheme is evaluated through simulation, with the main results presented in

Section 4.

Section 5 presents a discussion highlighting the practical relevance of the proposed solution. The conclusions are discussed in

Section 6. Finally, the closed-loop system stability analysis and the analytical derivation of the Bézier coefficients are presented in Appendices

Appendix A and

Appendix B, respectively.

2. DC Motor Model and Problem Definition

2.1. Permanent Magnet DC Motor

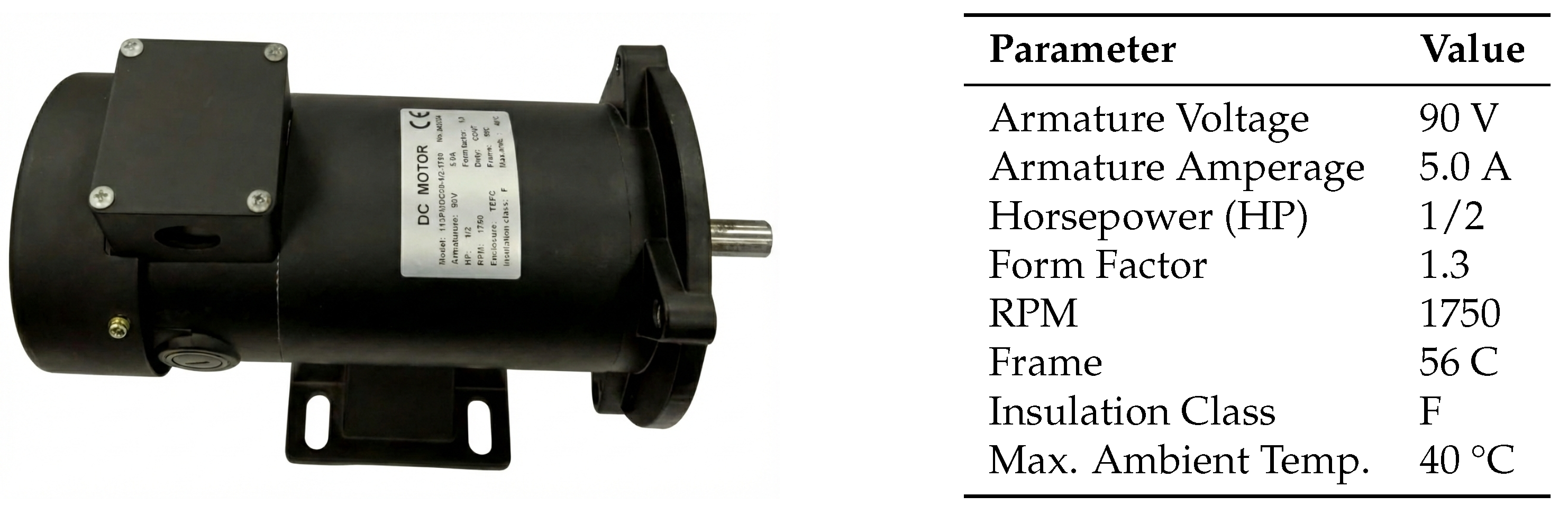

The PMDC motor used in this work is illustrated in

Figure 1. This is an armature-controlled motor rated for an input voltage of 90 V and a power of

HP. Additionally, it achieves a nominal speed of 1750 RPM.

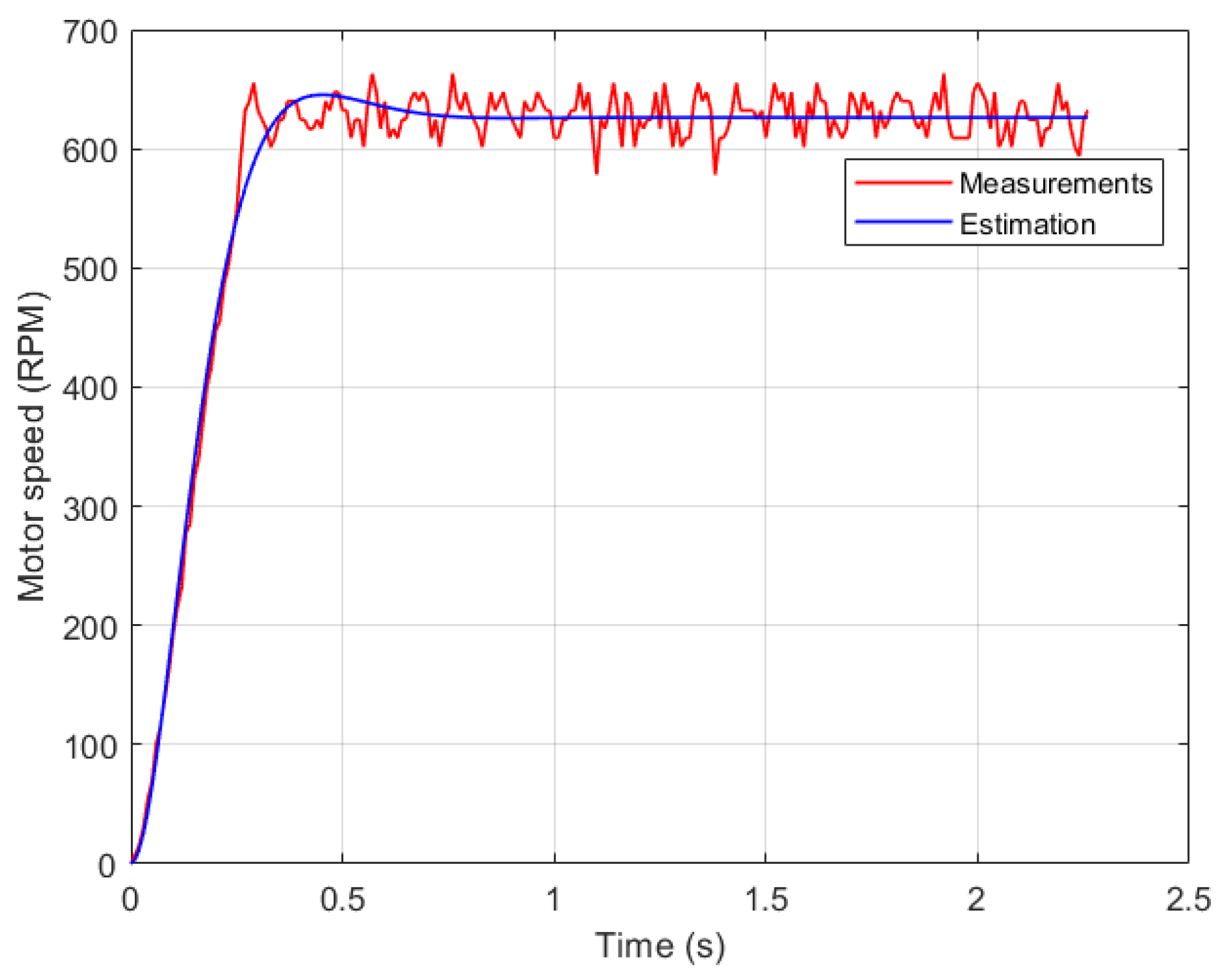

The mathematical model of the motor was obtained through an empirical system identification procedure, in which the relationship between the applied armature voltage and the resulting angular velocity was experimentally characterized. A step input of

was supplied as the excitation signal

, and the corresponding rotational speed was captured using an incremental encoder under no-load conditions. Following the methodology reported in [

18,

19,

20], the collected input–output data were processed using the System Identification Toolbox, a registered trademark of The MathWorks, Inc.

® Natick, MA, USA, to estimate a parametric model that best fits the motor dynamics. As a result, the following second-order transfer function was obtained:

which offers an accurate and compact representation of the motor behavior. The identified model (

1) achieves a Best Fit of

, as depicted in

Figure 2.

2.2. Reference Speed Trajectory Generation Using Bézier Curves

To ensure that speed tracking is not subject to abrupt changes that could induce excessive current spikes, a smooth reference trajectory signal is required. Smooth transitions are achieved using Bézier curves, which provide more convenient, continuous transitions [

21,

22].

The Bézier curve employed in this work to generate smooth transition segments in the reference speed profile is formulated through the following high-order polynomial representation [

23]:

where the normalized variable

maps the transition interval

onto the canonical Bézier parameter domain

. In this study,

and

denote the onset and completion of the reference speed transition, respectively.

Bézier curves are widely used in trajectory-generation problems because they provide smooth and continuously differentiable profiles through the adjustment of a finite set of coefficients or control parameters [

23,

24]. In the polynomial formulation adopted here (

2), the coefficients

play the role of shaping parameters that determine the curvature, slope, and smoothness of the resulting reference speed transition. Their values directly influence the steepness of the rise, the flatness around intermediate regions, and the slope at the beginning and end of the transition.

To ensure a physically meaningful and well-behaved reference speed profile, the coefficients were tuned to satisfy boundary conditions typically desired in practical implementations, such as zero initial and final slope, continuous curvature, and the avoidance of abrupt changes that could deteriorate closed-loop performance. These coefficients

can be obtained either manually or through numerical optimization algorithms (see

Appendix B) to ensure the required smoothness condition in the transitions is met. The resulting polynomial, therefore, provides a Bézier-based reference that is both smooth and dynamically compatible with the controlled system. In this work, the selected coefficients that shape the Bézier-based transition profile are

,

,

,

,

, and

. These values satisfy the desired smoothness and boundary conditions, producing a well-behaved reference speed transition compatible with the dynamics of the controlled PMDC.

The reference speed trajectory is defined using three target steady-state speeds, denoted as RPM, RPM, and RPM. These values represent the desired operating points the motor must reach during the execution of the trajectory.

The transitions between these speeds occur over six prescribed time instants: , , , , , and . Each interval defines a smooth transition phase between consecutive steady-state values.

To shape these transitions, the Bézier curves

(

2) used in this work for the

j-th transition (

) follows the polynomial form [

17,

21]:

where the normalized variable

ensures that each Bézier segment evolves smoothly from 0 to 1 within its respective transition interval.

Using these Bézier curves (

4), the complete reference speed trajectory is expressed as:

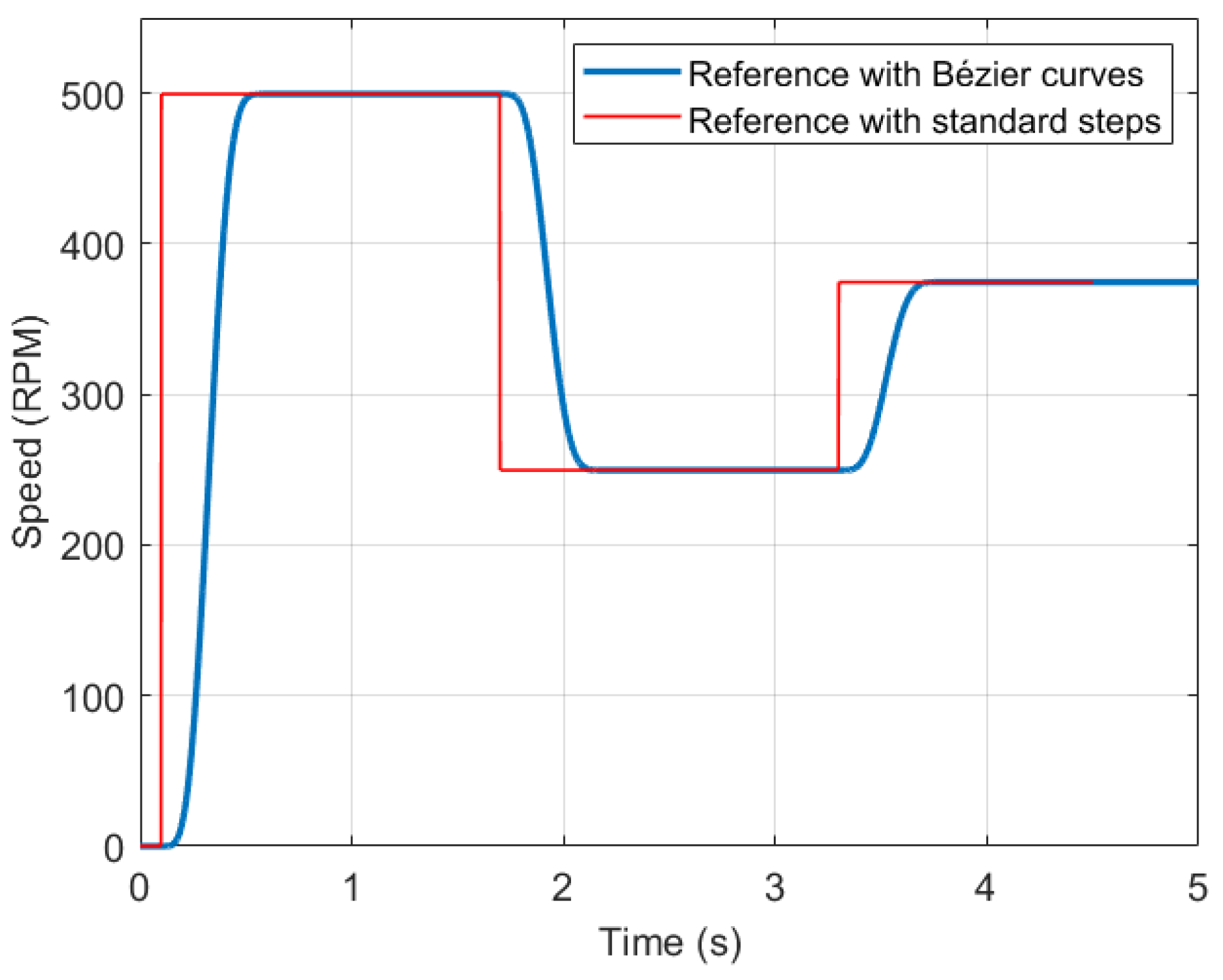

Using the previously defined Bézier curve, the resulting reference speed trajectory consists of three smooth operational segments connecting the desired steady-state speeds. As shown in

Figure 3, where both the Bézier-based reference signal and the standard step reference (presented only to illustrate the severity of abrupt transitions) are displayed, the Bézier formulation ensures continuously differentiable transitions that will significantly reduce the required control effort

during speed changes of

(

5). As a result, the motor requires a lower input voltage during each transition, effectively reducing the presence of voltage and current peaks. Therefore, the main goal of the control system is to accurately reproduce this smooth trajectory, ensuring that the actual motor speed converges precisely to the previously desired profile.

2.3. PID Controller

The Proportional–Integral–Derivative controller has been extensively used in the industry [

25] due to its efficiency, simplicity, and ease of implementation. In this study, the control algorithm is implemented to track the reference speed trajectory generated by the Bézier curves

determined in Equation (

5) and shown in

Figure 3. The Boost error, defined as

, is used by the controller to calculate the corrective action

(armature voltage), expressed as (

6):

where the controller constants

,

, and

stand for the proportional, integral, and derivative gains, respectively.

In this work, for simplicity and efficiency, the PID Tuner of MATLAB/Simulink R2025a was deployed, based on the transfer function (

1), to obtain the corresponding gains of Equation (

6). The resulting values are

,

, and

.

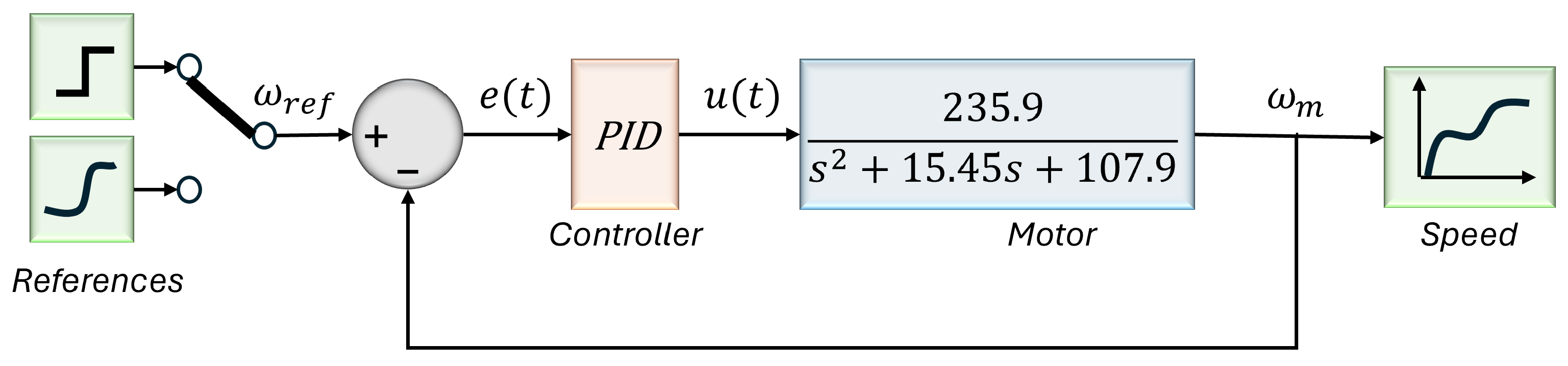

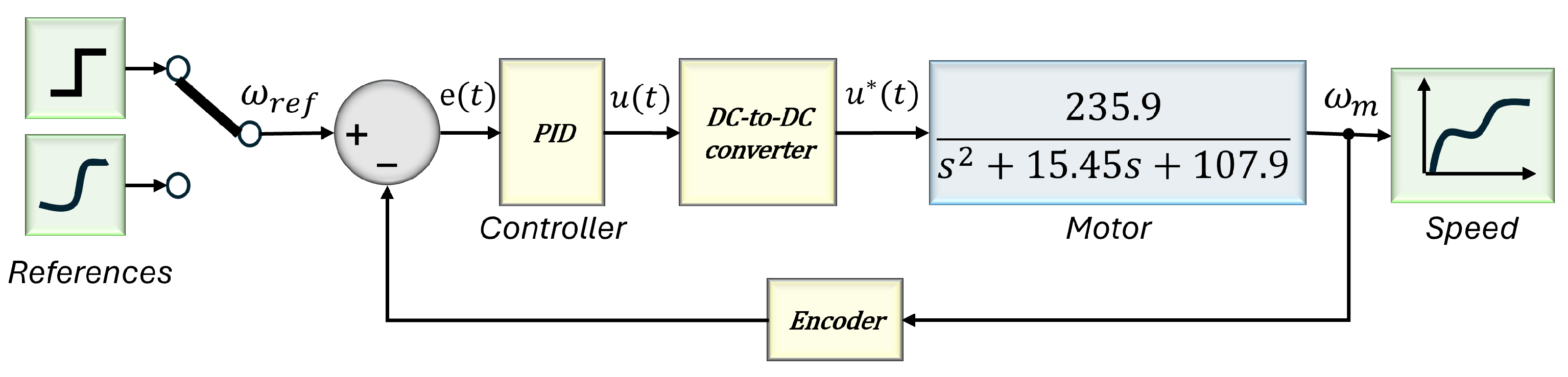

To evaluate the performance of the controller for speed tracking under smooth (Bézier curves) or stepped speed references, the closed-loop system was simulated, as shown in

Figure 4. It is worth mentioning that the DC-to-DC converter stage is not included initially. Therefore, only a baseline is established for the motor speed and control signal (armature voltage). The complete stability analysis of the closed-loop system shown in

Figure 4 is presented in

Appendix A.

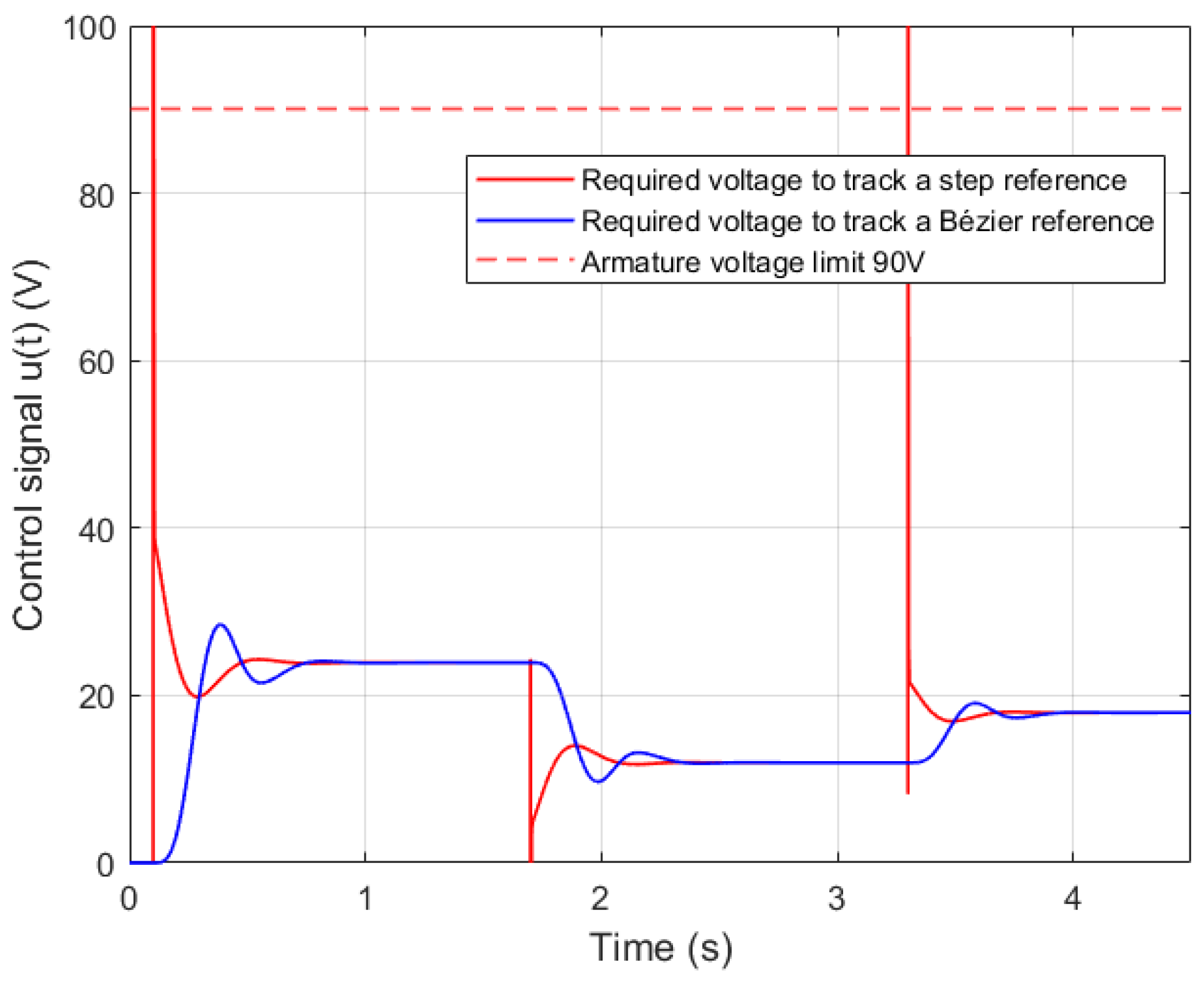

Figure 5 shows large voltage peaks (solid red line) during speed transitions, which are undesired in practical applications. Conversely, if smooth transitions are applied (

5), large voltage peaks disappear, resulting in reasonable voltage levels (solid blue line). Furthermore, in both scenarios, the control signals show the capability to reach constant voltages under steady-state conditions.

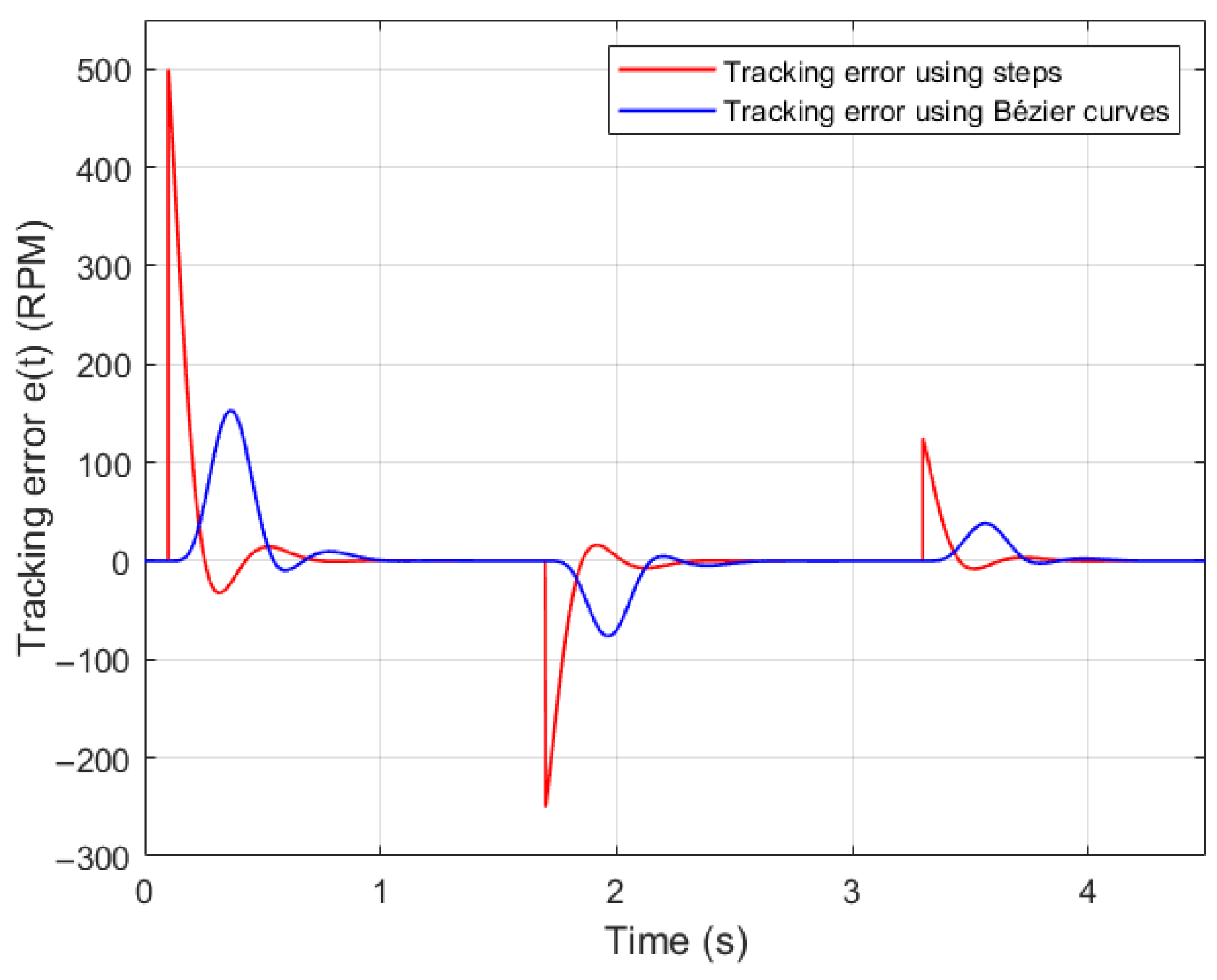

Figure 6 illustrates the speed-tracking error performance. Although the overall response is satisfactory, noticeable short-duration error peaks appear at specific instances in the red plot, whereas these errors are significantly reduced in the blue plot. This confirms that Bézier curves do not result in a loss of tracking performance; rather, they improve the transient response.

By smoothing the speed transitions, a significant reduction in the large voltage peaks is achieved. To supply the required motor voltage within reasonable limits, a DC–DC converter must now be incorporated into the system. Since the converters operate at a sufficiently high switching frequency, a time-scale separation between the fast electrical dynamics of the converters and the slower mechanical response of the DC motor is established. Consequently, the converter is modeled as a quasi-static gain. To ensure speed tracking, the duty cycle is adjusted according to the control signal, guaranteeing that the armature voltage follows ; in this way, the converter behaves as a unit gain block. The following section presents several power converter topologies suitable for this purpose.

3. DC–DC Power Converter Comparison

Although motor speed control is one of the most extensively studied topics in the literature, few studies focus on evaluating the driver’s capability to track the voltage variations required to achieve the desired performance. In this section, three DC–DC converters are analyzed and compared to illustrate their operation. These converters were selected for their ease of implementation and to represent distinct voltage conversion characteristics, including negative gain, positive gain, and quadratic gain behaviors. To ensure a fair and consistent comparison, all converters were implemented using the same inductance and capacitance values, thereby establishing a common electrical baseline. This approach allows differences in voltage and current responses to be attributed directly to the converter topology and voltage conversion mechanism, rather than to component value tuning. While identical component values may lead to different current ripple characteristics due to the inherent energy transfer processes of each topology, this effect is intrinsic to the comparison and forms part of the evaluation. Structural complexity and relative cost are therefore reflected by the number of passive and active components, as summarized in

Table 1. In addition, the selected converters highlight the contrast between well-established solutions and a higher-gain modern alternative when used in PMDC motor speed control applications. A detailed ripple optimization or market-based cost analysis is beyond the scope of this work and will be considered in future studies.

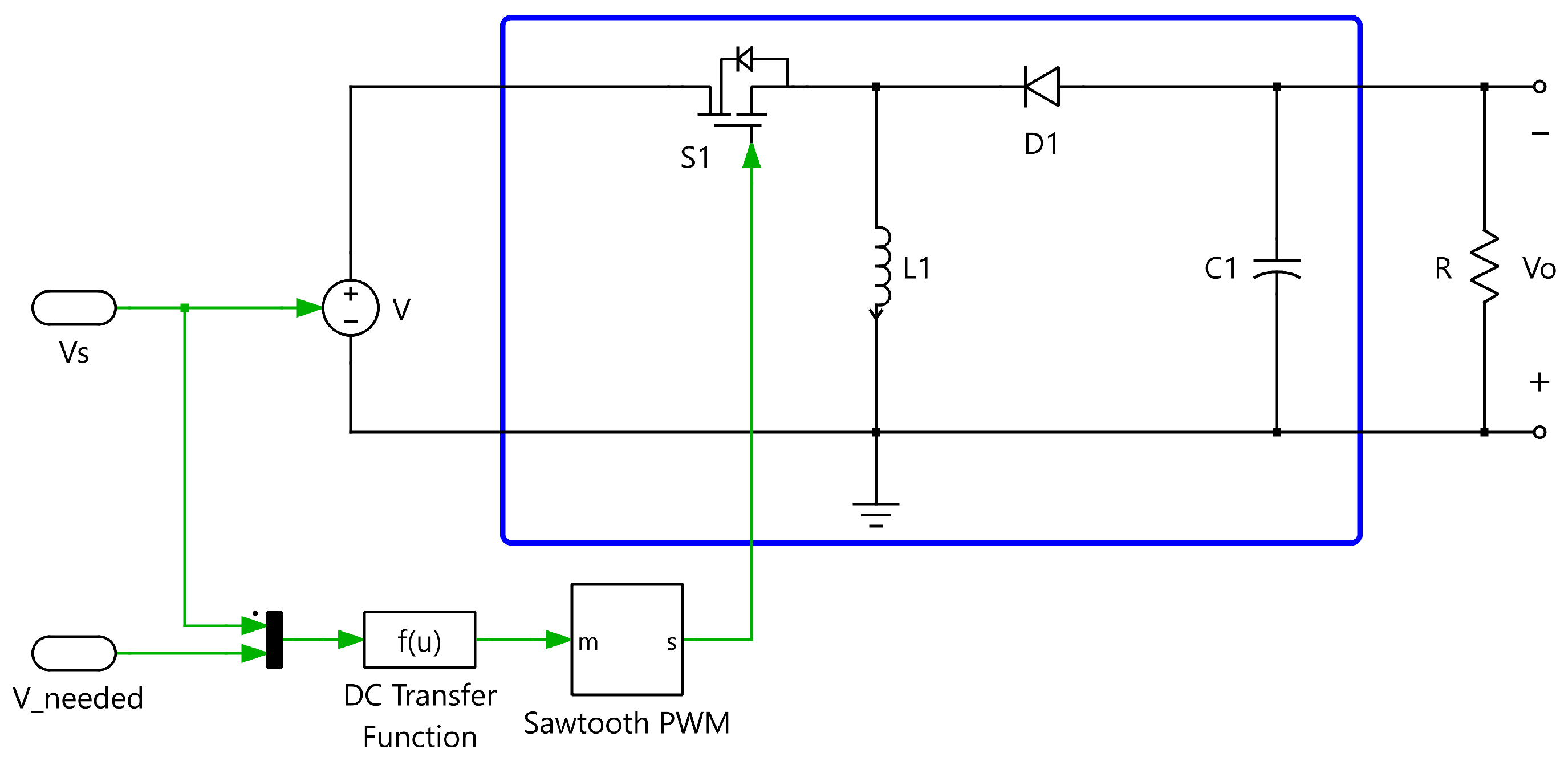

3.1. Inverting Buck–Boost Converter

The first converter analyzed is the traditional inverting Buck–Boost converter, shown enclosed in blue in

Figure 7. This topology has been widely used in various applications, including modern electronic equipment [

26,

27], due to its ability to provide an output voltage that can be either higher or lower in magnitude than the input, with an inverted polarity. Its straightforward configuration and control simplicity make it an excellent reference for evaluating the behavior of more complex converter topologies under similar operating conditions.

The design of this converter, considering the continuous conduction mode (CCM), i.e., current with the inductor current not reaching zero for a long period of time, has been included in several previous texts, like [

28]. Here, the equation that dominates the ratio output/input is

with

indicating the converter output voltage,

indicating the source voltage, and

D indicating the duty cycle, defined as the time the switch is closed in relation to the following switching period:

The controlling variable for the converter is the duty cycle

D, so it is convenient to represent it as the following voltage transfer function:

The size of the reactive components is determined for the continuous conduction mode, considering the output current to be the nominal current of the motor to define the load resistor as follows (

10):

The list of component values for this and the other converters included in this proposal is summarized in

Table 1.

It is very important to remember that the output has a negative sign.

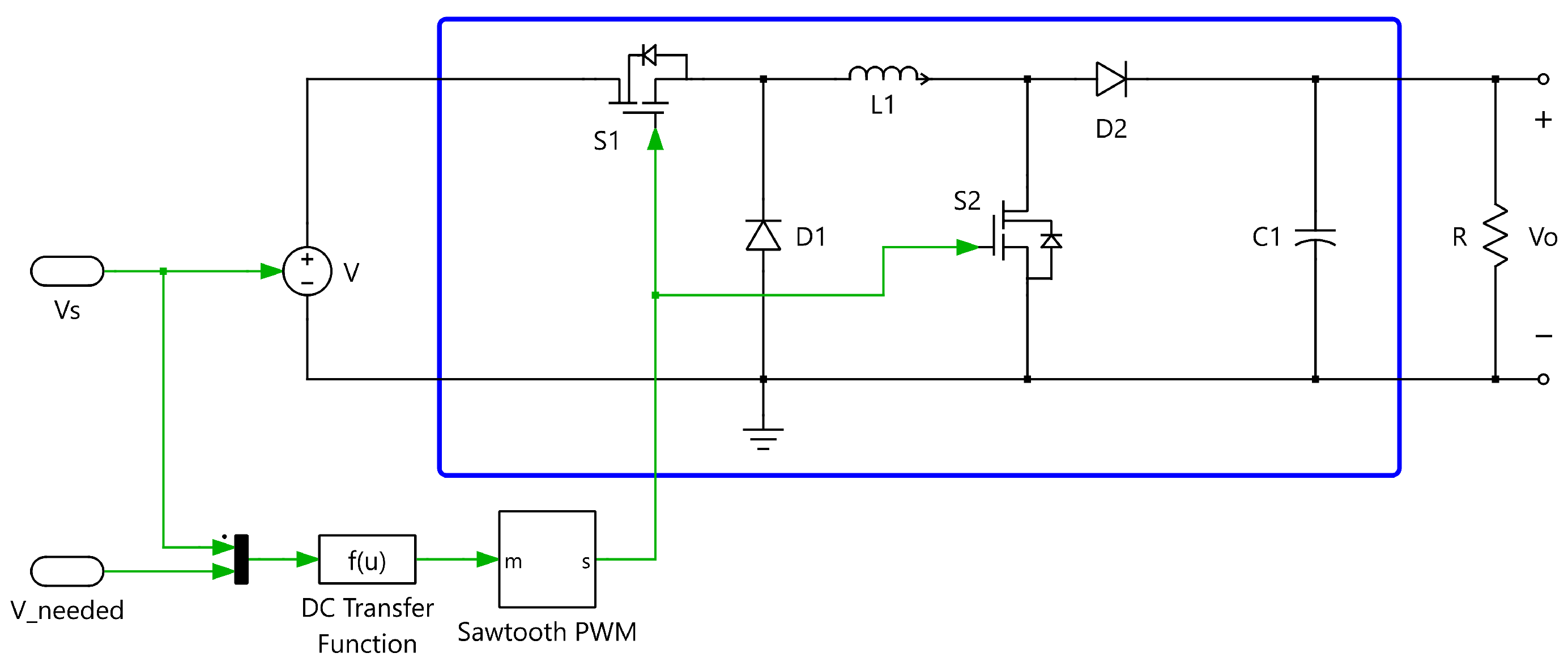

3.2. Positive Buck–Boost Converter

If the negative output voltage represents a limitation for certain connection requirements, a simple solution is to connect two converters in a cascaded (pipeline) configuration. The concept of this approach is discussed in [

29], where a Buck and a Boost stage are combined to produce a positive-output Buck–Boost converter, as illustrated in the blue block of

Figure 8. This configuration retains the versatility of the traditional Buck–Boost while eliminating the polarity inversion issue, making it suitable for a broader range of applications.

The voltage gain of this circuit is equivalent to that of the previous configuration, but with a positive output. Therefore, Equations (

7)–(

10) remain valid for this design. However, the number of components increases, particularly in switches and diodes, as summarized in

Table 1.

3.3. Quadratic Gain Converter

Quadratic converters are often selected when a high voltage gain is required to supply or manage specific loads. This behavior has been reported in several studies, including the configuration presented in [

30] and illustrated in

Figure 9. The voltage gain of this converter is derived from the relationship given in (

11).

Again, the controlling variable is the duty cycle

D, so the relationship (

11) becomes the following:

The set of components used for this topology is included in

Table 1.

4. Simulation and Experimental Results

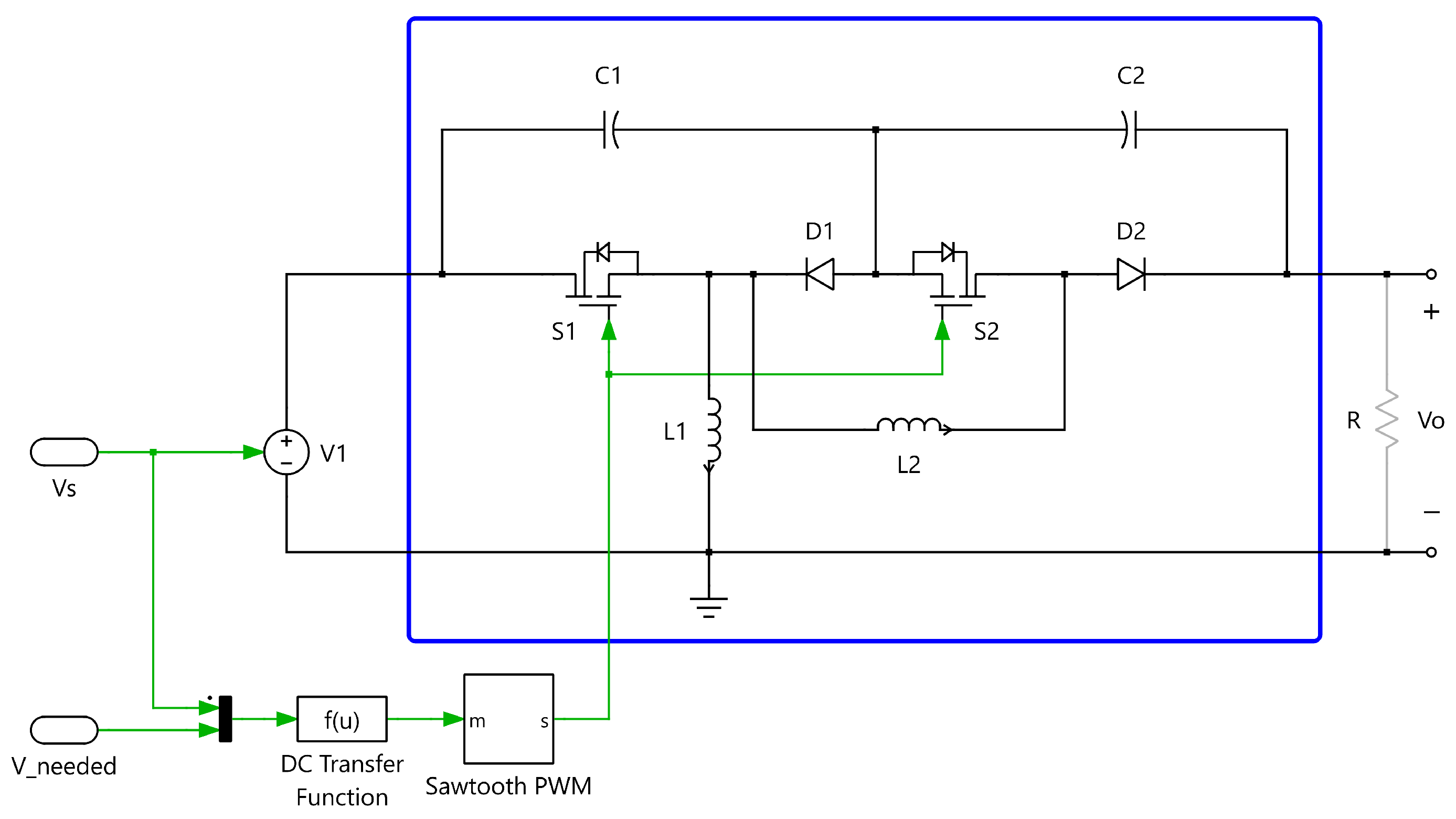

To validate the performance of the DC-to-DC converters and the implementation of the Bézier curves, a simulation is conducted using the closed-loop system configuration shown in

Figure 10, which includes the DC–DC converter. The simulation was developed using PLECS Standalone 4.9.8 and RT Box 1 to develop hardware in the loop option. In this setup, control law (

6) receives the tracking error as input and generates an output signal that modulates the duty cycle of the DC-to-DC converter to achieve the desired armature voltage for the DC motor.

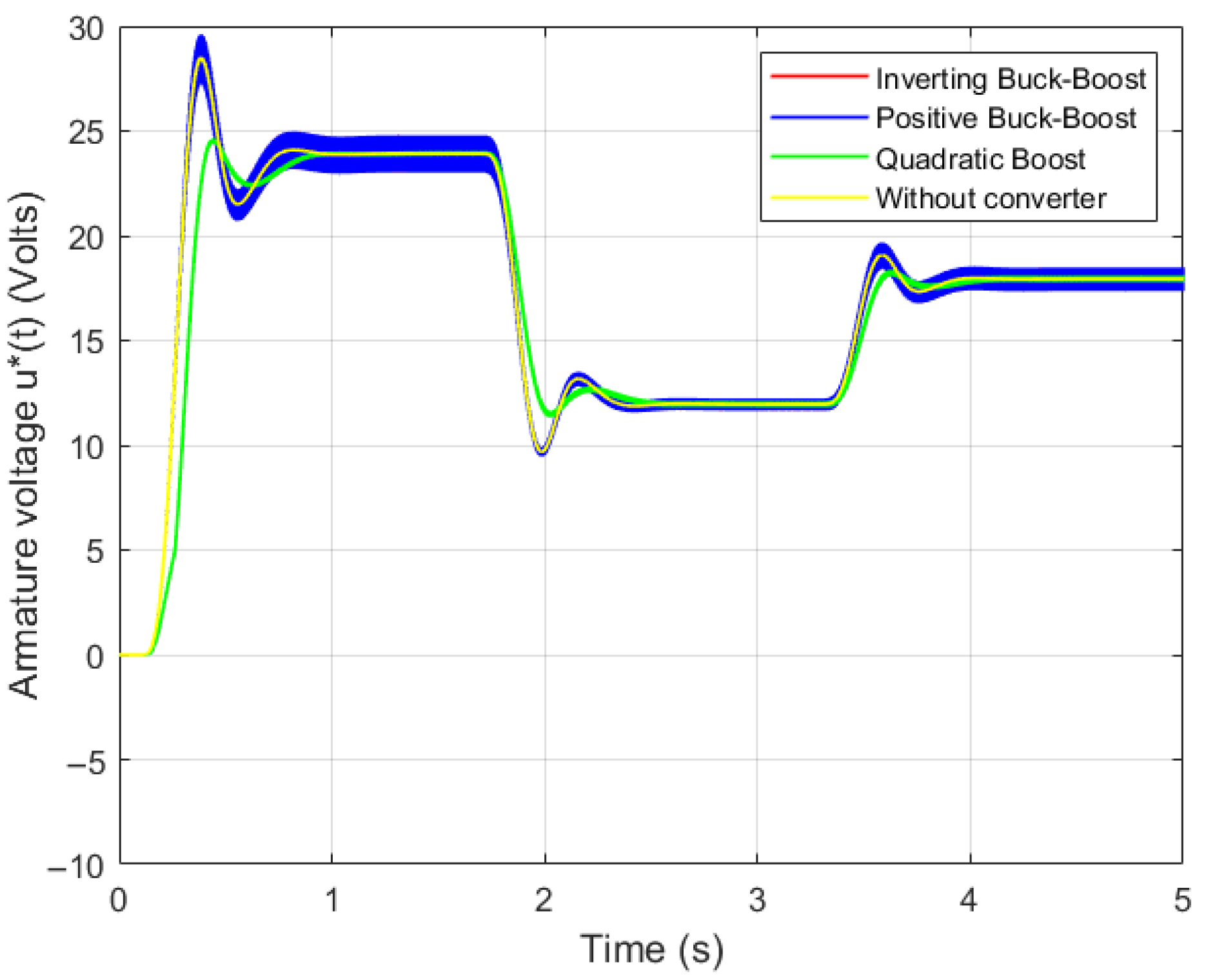

The performance of the three converters, along with the reference case without a converter, in achieving the required voltage for motor driving is illustrated in

Figure 11. In this plot, the positive Buck–Boost converter response overlaps with that of the inverting Buck–Boost converter response plotted with reversed polarity. This is true since both are controlled by the same control variable. It is noticeable that a good following of the shape is required for ideal conditions without a driver. On the other hand, the quadratic converter presents a different pattern, but the steady-state condition is also obtained. Oscillations are observed in all three converters, with the smallest ripple occurring in the quadratic converter, which can be operated to increase the output voltage and even reduce it at the expense of a slower dynamic response. As shown in

Figure 11, the output voltages

remain within reasonable limits regardless of the converter topology employed.

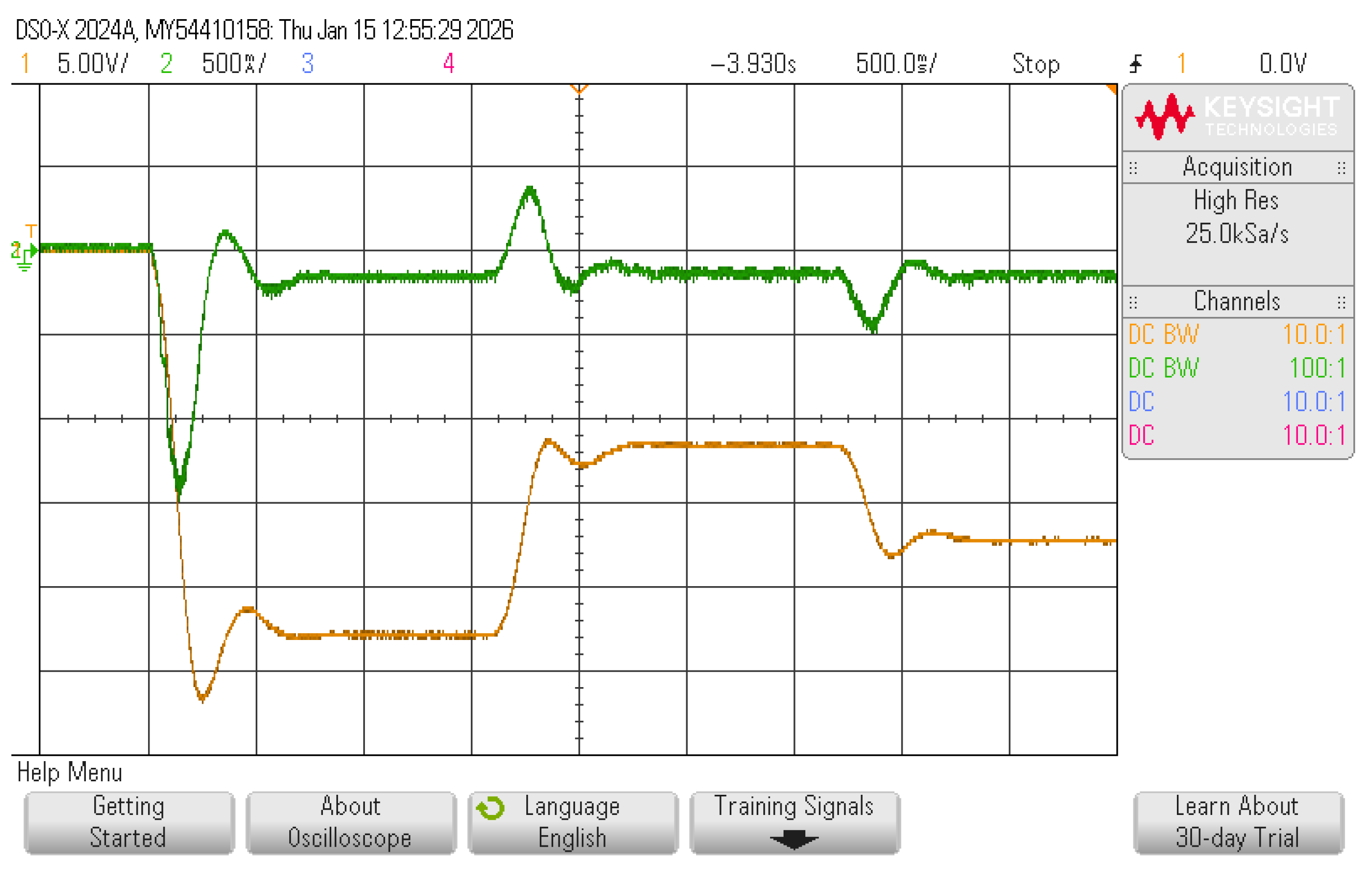

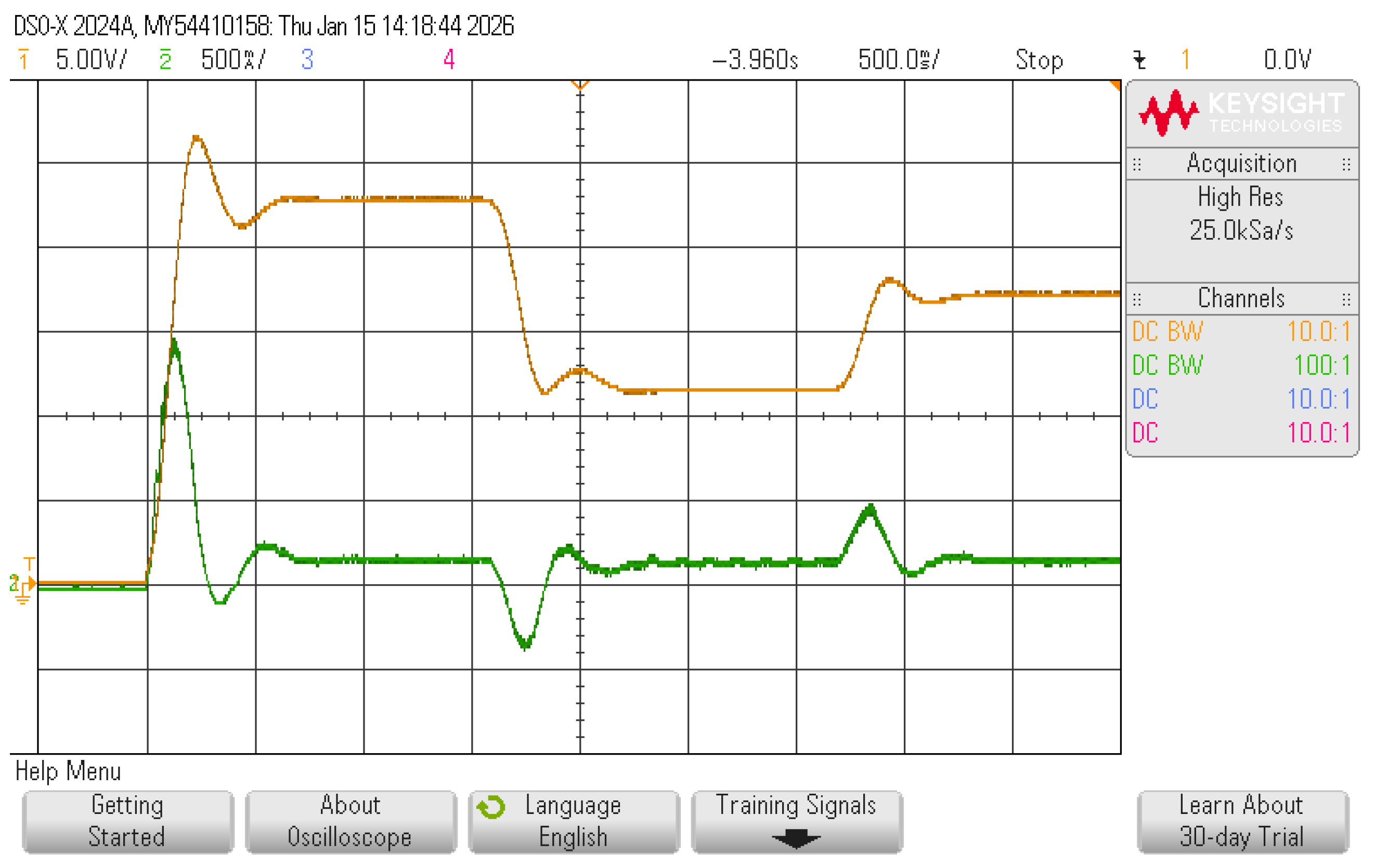

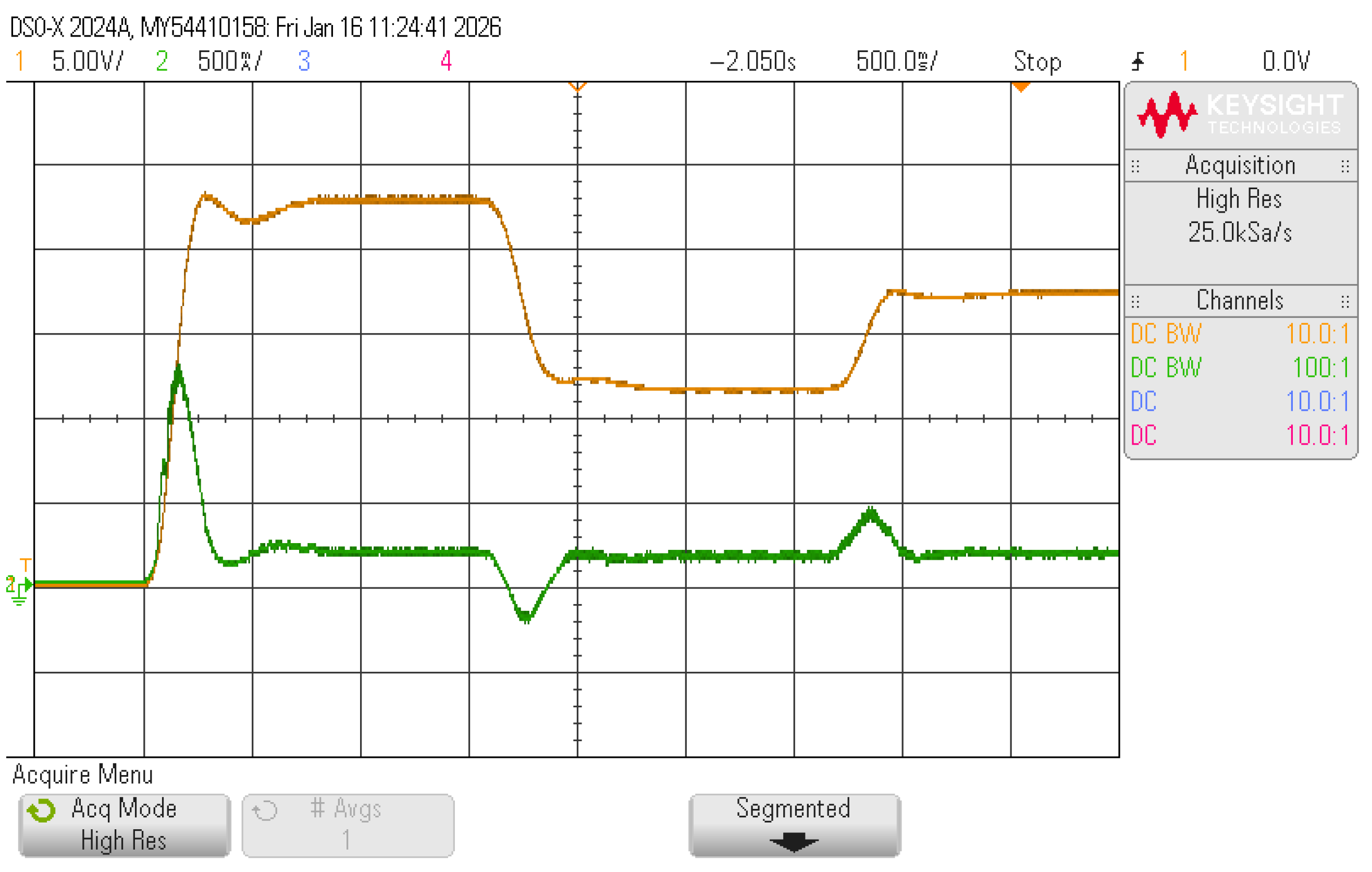

Experimental validation of the three converter topologies was conducted using a lab prototype and a DSO-X2024A oscilloscope (Keysight Technologies, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) to capture output voltage images. The PMDC motor was operated without a mechanical load, and only changes in speed references were considered. Consequently, the current demands are mainly associated with transient speed changes rather than load torque variations. The corresponding waveforms are presented in

Figure 12 for the inverting Buck–Boost converter. Here, the negative output polarity is clearly observed. The positive Buck–Boost converter exhibits the waveform shown in

Figure 13, which appears as a mirror image of the previous case. The response of the quadratic converter is also depicted in

Figure 14, where the main differences among the topologies are evident in the output voltage ripple and the time required to reach a steady state.

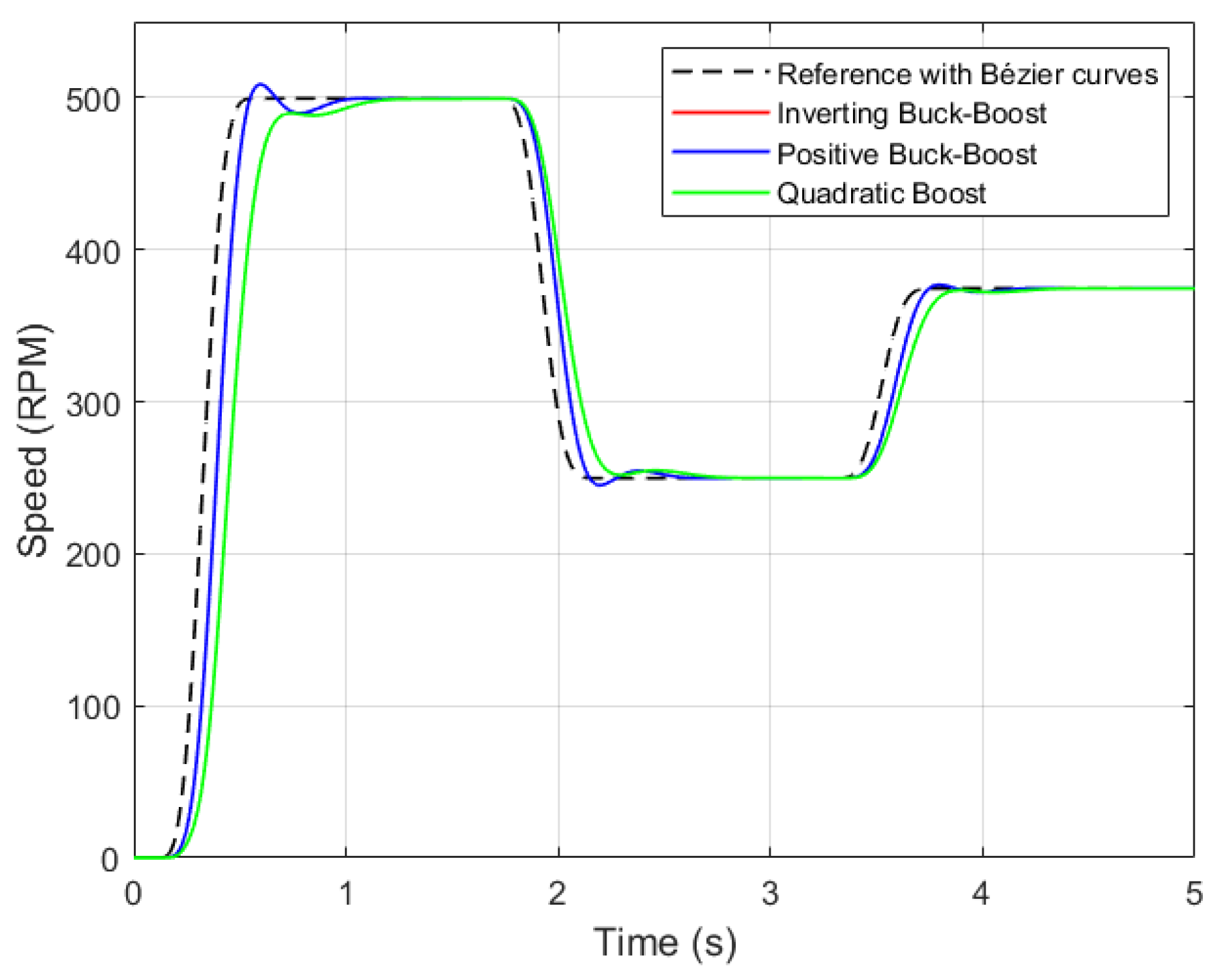

By comparing the Boost performance of the three converters in

Figure 15, it is evident that all configurations exhibit satisfactory behavior, regardless of whether the motor speed increases or decreases.

The settling time is shorter for both the inverting and positive Buck–Boost converters, with a small ripple resembling that of a lightly under-damped second-order system with minimal overshoot. In contrast, the quadratic converter shows a slower response when the input voltage exceeds the motor’s required voltage (buck operation), exhibiting the characteristics of an over-damped second-order system with no overshoot. However, when the input voltage is lower than the motor’s required voltage (boost operation), its response resembles that of the other two converters but with reduced ripple amplitude.

Table 2 summarizes the findings of this strategy:

Regarding the transient response characteristics,

Table 2 reports the rise time and stabilization (settling) time associated with the three speed transitions of the Bézier-based reference profile. The inverting and positive Buck–Boost converters exhibit consistently shorter rise times, indicating a faster dynamic response to changes in the reference speed. Their settling times remain comparable across all transitions, reflecting a lightly under-damped behavior with limited oscillations.

In contrast, the quadratic converter presents longer rise times, particularly during voltage buck operation, which is characteristic of an over-damped response. Although this behavior reduces overshoot and ripple, it leads to slower stabilization compared to the other topologies. These results highlight the trade-off between transient speed and smoothness when selecting the converter topology.

Table 3 summarizes the speed-tracking performance using both absolute and normalized indices. The root mean square error (RMSE), expressed in revolutions per minute (RPM), quantifies the average deviation between the motor speed and the reference signal. The normalized root mean square error (NRMSE), the normalized integral of squared error (NISE), and the normalized integral of time-weighted absolute error (NITAE) are dimensionless indices that enable an objective comparison among converter topologies, independently of the speed magnitude.

Using the results reported in

Table 3, it can be observed that the Inverting Buck–Boost and Positive Buck–Boost converters exhibit very similar tracking performance under identical control and reference conditions. Both topologies achieve a lower RMSE of approximately 30 RPM and a normalized tracking error (NRMSE) close to 6%, indicating accurate speed regulation throughout the entire operating interval. In contrast, the quadratic gain converter presents a noticeably larger RMSE (52.87 RPM) and higher normalized error indices (NRMSE, NISE, and NITAE), revealing slower transient responses and a larger accumulation of tracking error during speed transitions. These results are consistent with the transient behaviors observed in the speed response plots and confirm that, for the considered operating conditions, the Inverting and Positive Buck–Boost converters provide superior speed-tracking performance compared to the quadratic gain topology.

It is worth noting that the reported error-based indices are computed over the entire reference profile, which includes multiple speed transitions. This choice reflects the global tracking performance of the drive under non-stationary operating conditions and enables a fair comparison among the converter topologies under identical reference trajectories.

Since the absolute value of the error-based indices depends on the speed magnitude, normalized indices are also reported to facilitate an objective comparison among the converter topologies.

In addition to the dynamic and tracking performance indices, the maximum absolute voltage values were extracted from the experimental data to quantify the electrical stress imposed on the drive for each converter topology.

The required overvoltage for each converter topology is explicitly quantified through the maximum absolute voltage values reported in

Table 4. These values represent the peak voltage stress imposed on the power stage during the tracking of the prescribed speed profile. The quadratic converter exhibits the lowest maximum voltage level, indicating reduced electrical stress, while both Buck–Boost configurations require higher peak voltages to achieve faster dynamic responses.

This comparison establishes a clear design criterion in terms of overvoltage requirements and complements the transient performance analysis, enabling a balanced assessment of dynamic response and electrical stress.

5. Discussion

Although Class C and Class E DC–DC converters are widely recognized for their high efficiency in resonant and high-frequency applications [

28,

31,

32], their operation is typically restricted to narrow operating conditions and fixed load profiles. These topologies require precise resonant tuning and exhibit strongly nonlinear dynamics that depend on load and switching conditions, which complicates their integration with classical control strategies for continuous voltage regulation. In contrast, this proposal discusses converters that can be used to increase or decrease voltage levels in a smooth way, which makes them part of Class A converters [

16]. Moreover, the fed voltage to the load makes them still considered Class C converters.

A PID controller was selected instead of a PI controller because the overall drive dynamics considered in this work are adequately represented by a second-order model, and the speed-regulation task is performed under varying operating conditions. Although Bézier-based reference trajectories are employed to smooth command transitions and mitigate abrupt changes in the reference signal, such reference shaping does not modify the intrinsic closed-loop dynamics nor provide additional damping or phase lead. The derivative action of the PID controller contributes effective damping and phase lead, which improves transient behavior by reducing overshoot and settling time and enhances robustness against load disturbances and modeling uncertainties. While a PI controller is often sufficient to ensure zero steady-state error, it may lead to a more oscillatory transient response for the considered dynamics, even when smooth reference profiles are used. In practice, the derivative term is implemented using standard filtering techniques to mitigate noise amplification.

As summarized in

Table 5, a comparative analysis is conducted between the proposed solution and different control algorithms reported in recent literature, including classical PID/PI, sliding mode control, fuzzy logic control, and hybrid or advanced schemes. The proposed PID-based approach, combined with Bézier reference shaping, provides a favorable trade-off between control performance, implementation simplicity, and real-time applicability, effectively reducing voltage peaks during speed transitions while avoiding the computational and design complexity associated with more advanced nonlinear or hybrid control strategies. In contrast, the proposed approach provides a favorable trade-off between control performance, implementation simplicity, and hardware safety, making it well-suited for real-time applications and experimental platforms.

Although DC motor speed control with feedback loops is a well-established topic in the literature, the contribution of this work does not rely on proposing a new control algorithm. Instead, it focuses on addressing a set of practical implementation challenges that frequently arise in experimental setups and are often overlooked in simulation-oriented studies. The proposed approach emphasizes a hardware-aware design philosophy that prioritizes reliability, safety, and real-time applicability.

A first relevant aspect concerns the modeling of the DC motor. Unlike many studies that assume access to manufacturer-provided parameters, the motor used in this work lacked a datasheet, preventing direct knowledge of electrical and mechanical constants. Consequently, an experimental identification procedure based on measured voltage and speed data was carried out, allowing the derivation of a suitable dynamic model using MATLAB R2025a system identification tools. This approach reflects a common real-world scenario involving commercial or legacy motors for which detailed documentation is unavailable.

Experimental observations further revealed that the motor speed transient under constant voltage excitation occurs within approximately 0.3 s. To capture sufficient information during this fast transit, the sampling period for the speed measurement was reduced to 10 ms. This decision enabled reliable model identification and controller tuning, highlighting the importance of adapting data acquisition strategies to the actual system dynamics rather than relying on default sampling configurations.

From the power electronics perspective, additional constraints had to be considered during the implementation of the DC–DC converter stage. In particular, explicit limits were imposed on the duty cycle to prevent operation at or near 100%, which may lead to hardware failure. Moreover, the switching frequency was selected according to converter module specifications, as deviations from recommended values can negatively affect performance or compromise system safety. These considerations underline the relevance of incorporating hardware limitations directly into the control design process.

Another important aspect is related to measurement quality. The presence of voltage ripple at the converter output, combined with encoder measurement noise, introduced fluctuations in the measured speed signal. To mitigate these effects, the derivative term of the PID controller was implemented using a filtering strategy, which helped attenuate noise while preserving adequate transient performance. In addition, a custom mechanical structure was designed and fabricated using 3D printing to rigidly couple the motor shaft and the encoder, significantly improving measurement reliability compared to a simple shaft coupler.

Regarding reference generation, Bézier-based trajectories were employed as a command-shaping mechanism to smooth speed transitions and reduce abrupt voltage variations. This strategy effectively lowers voltage peaks and control effort without altering the intrinsic closed-loop stability properties of the system. It is important to note that Bézier shaping complements, rather than replaces, the role of the PID controller by acting exclusively on the reference signal.

6. Conclusions

This paper has demonstrated that controlling the speed of a PMDC motor through the regulation of the armature voltage profile can yield excellent results using traditional controllers such as PID. Smoothing speed transitions using Bézier curves effectively reduces high peak demands in voltage and current, helping to prevent the activation of protection limits in practical applications. By limiting abrupt electrical transients, this approach reduces excessive stress on power electronic devices, mitigates thermal loss increases, and minimizes mechanical torque shocks, thereby improving overall system reliability and lifespan. The combination of standard controllers with Bézier-based trajectory shaping enables the effective use of different power converter topologies to achieve the desired dynamic behavior. In this proposal, Bézier curves were intentionally selected with moderate transition speeds to facilitate clear observation and validation of the resulting voltage and current waveforms. However, the flexibility of Bézier curve parameterization allows the trajectories to be accelerated as required by the application, while still avoiding the sharp voltage and current peaks typically associated with abrupt reference changes. This characteristic makes the proposed approach adaptable to a wide range of dynamic requirements without compromising electrical or mechanical stress limits and eliminates the need for an inner current loop, providing an advantage in simplicity compared to conventional double-loop control designs. Three EMDS converters were used to drive the motor, all constructed with identical component values. This design choice establishes a common electrical baseline, ensuring that the observed differences in dynamic performance, ripple behavior, and implementation cost are primarily attributable to the converter topology rather than component value optimization. Among the proposed topologies, the positive Buck–Boost converter proved to be the most suitable for dynamic operation, as it ensures a positive output polarity while accommodating input voltages that may be both lower or higher than the steady-state level required for the motor’s operating point. However, if reversing the motor connections is acceptable, the inverting Buck–Boost converter becomes the most cost-effective option due to its minimal component count. For applications requiring a high ratio, the quadratic converter provides the desired voltage with very low ripple, although it requires twice as many reactive components and exhibits a slower response when the input voltage exceeds the motor’s nominal requirement. Overall, this work can serve as a practical reference for power electronics engineers and researchers entering the field of motor drive design, as it presents a complete methodology from modeling and control to real-time implementation and comparative evaluation of converter topologies. In addition to motor drive applications, the proposed strategy could be extended to other scenarios requiring smooth speed regulation, such as cruise control systems in electric or hybrid vehicles. However, such applications are beyond the scope of the present study and are mentioned only to highlight the broader applicability of the proposed approach. The investigation and evaluation of alternative trajectory generation or reference-shaping methods constitute an interesting and valuable extension of this work and will be considered as part of future research directions.