Probabilistic IM-Based Assessment of Critical Engineering Demand Parameters to Control the Seismic Structural Pounding Consequences in Multistory RC Buildings

Abstract

1. Introduction

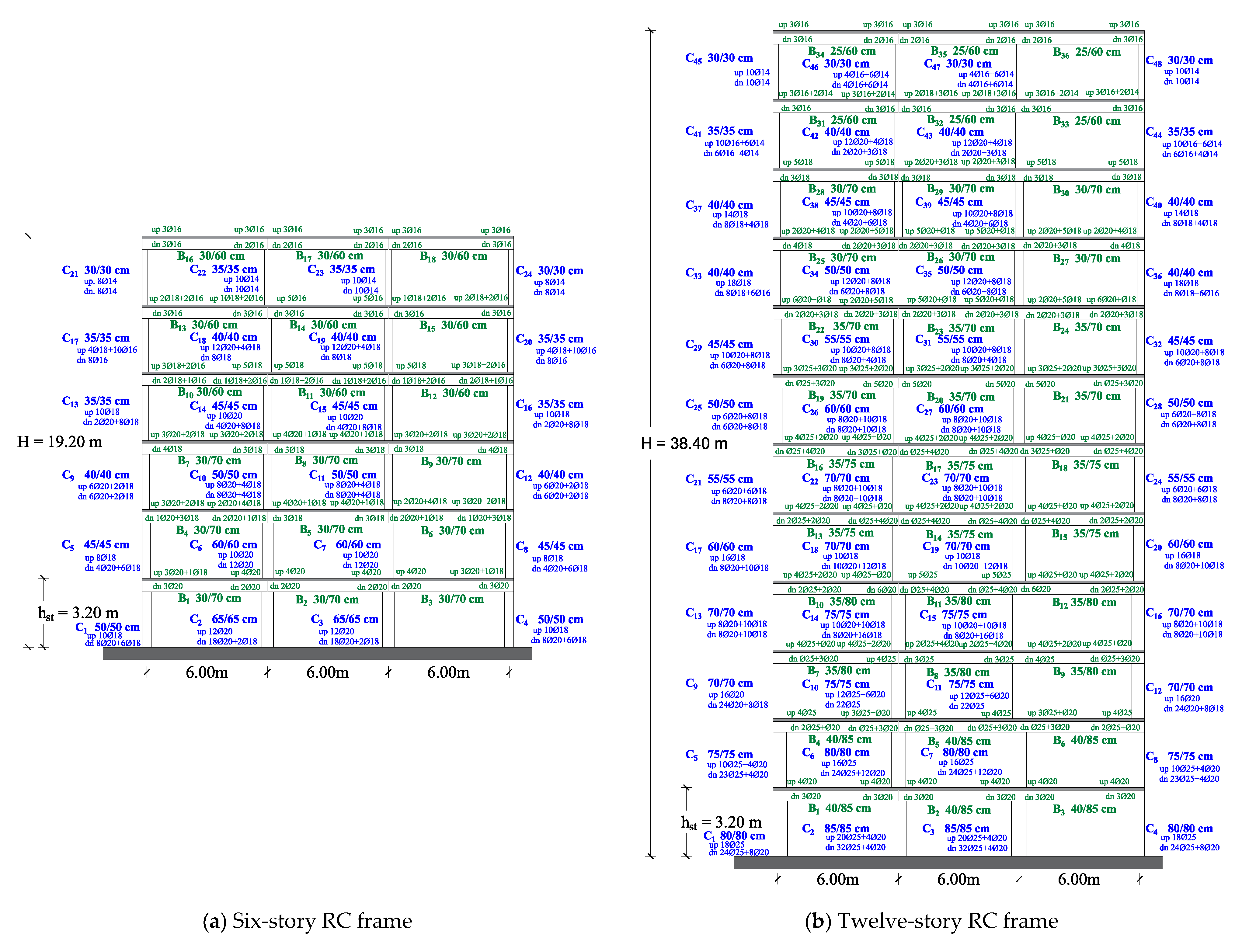

2. Design of Multistory RC Buildings

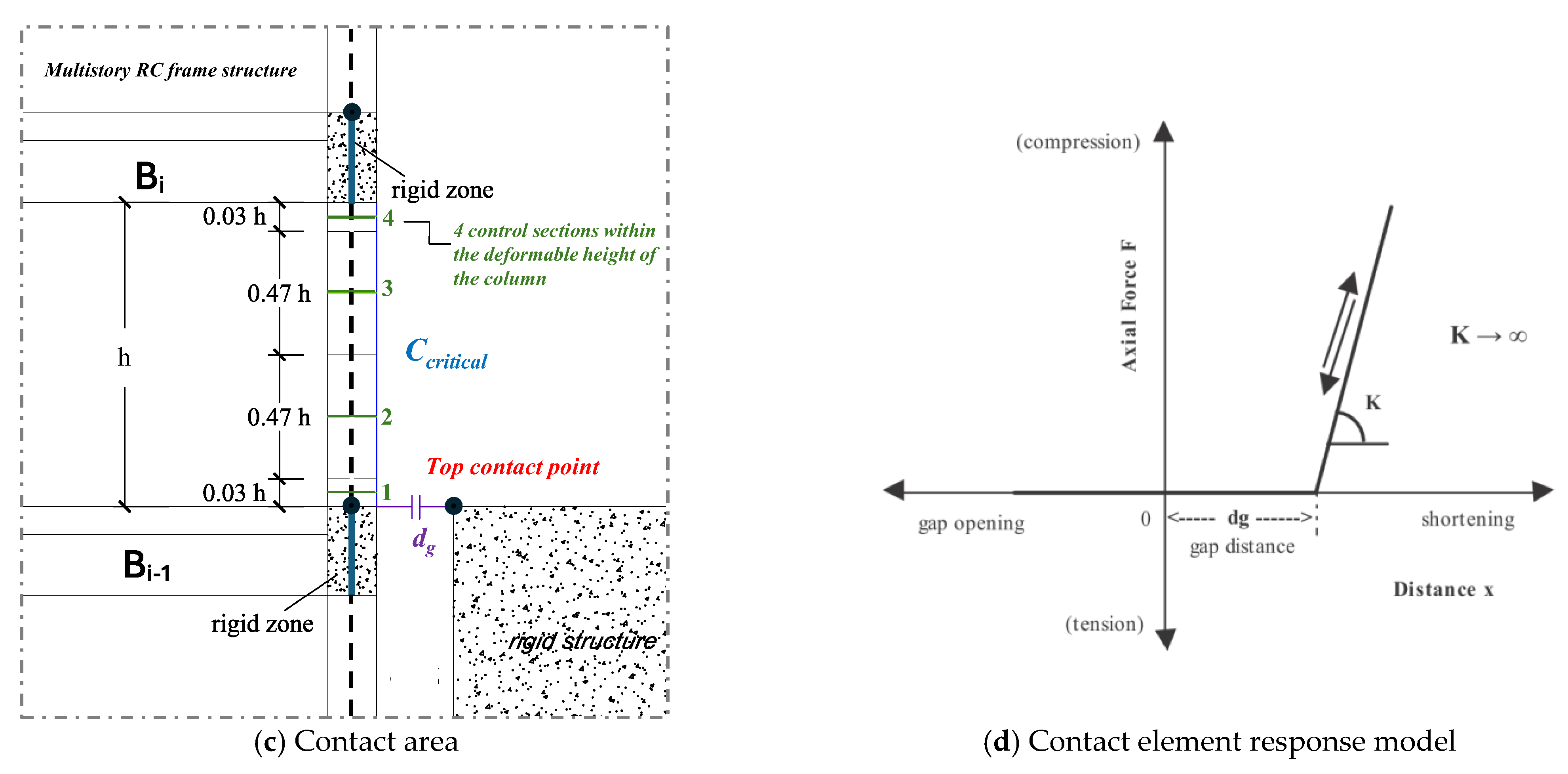

3. Structural Modelling Assumptions

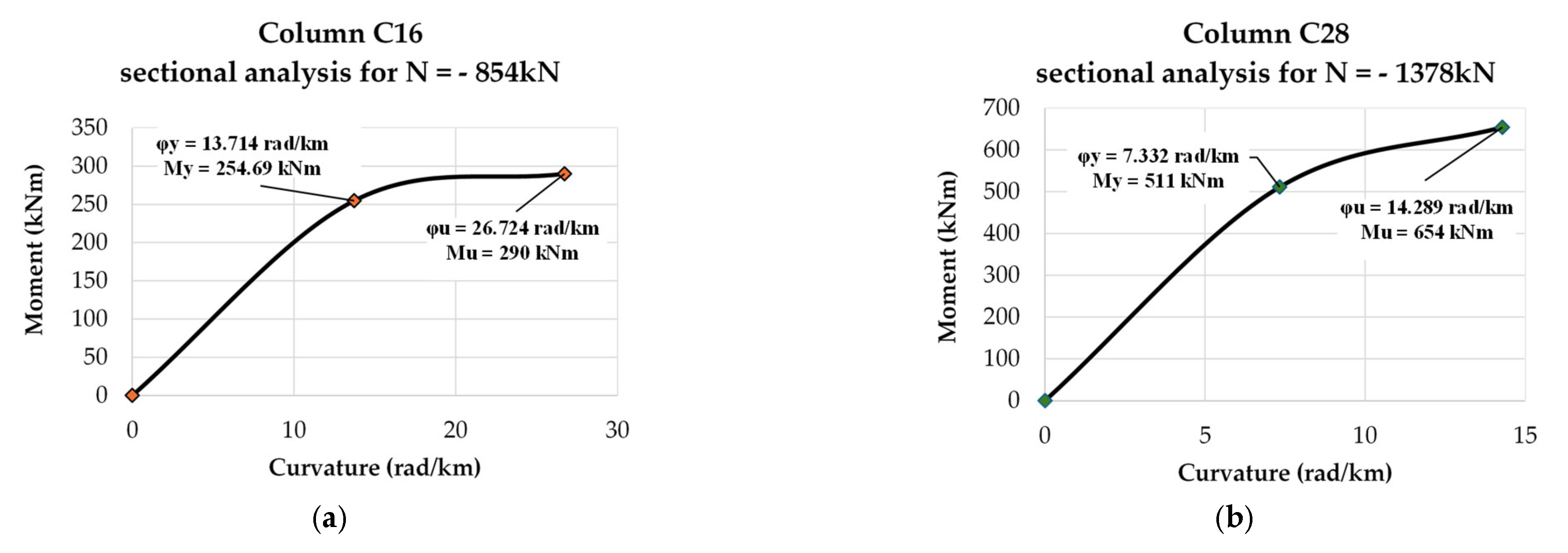

4. Fragility Curve Based on Linear or Bilinear PSDMs

5. Examined Parameters

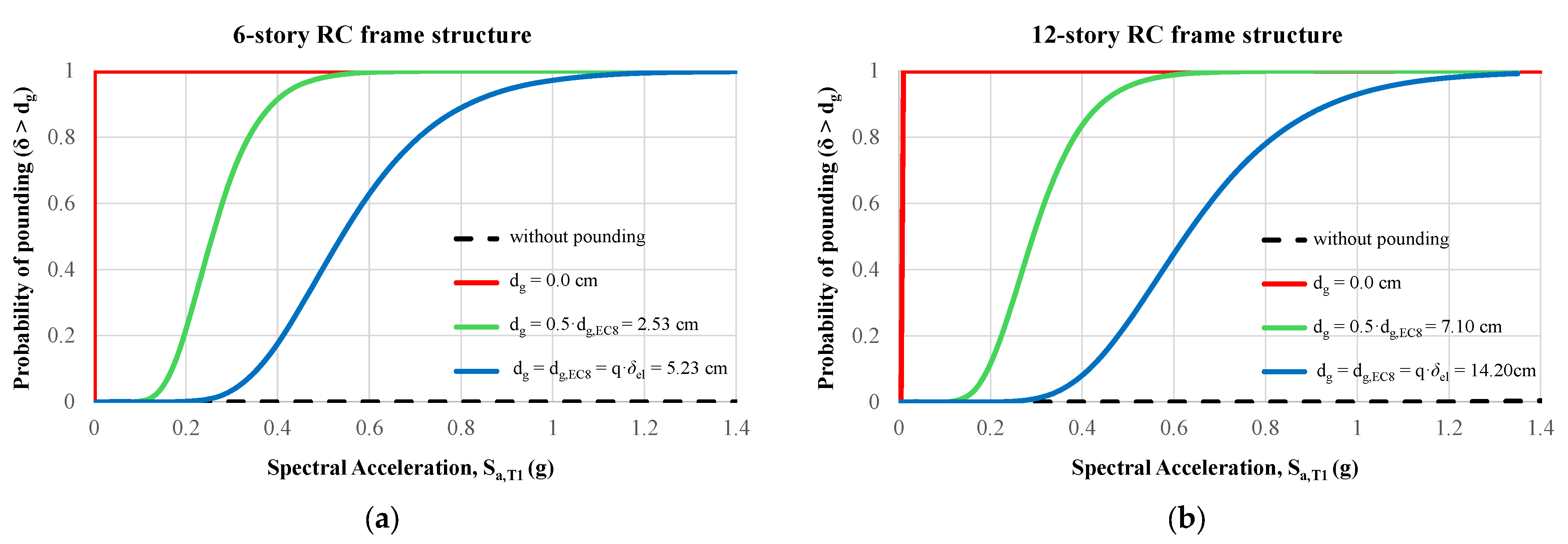

6. Results

7. Conclusions

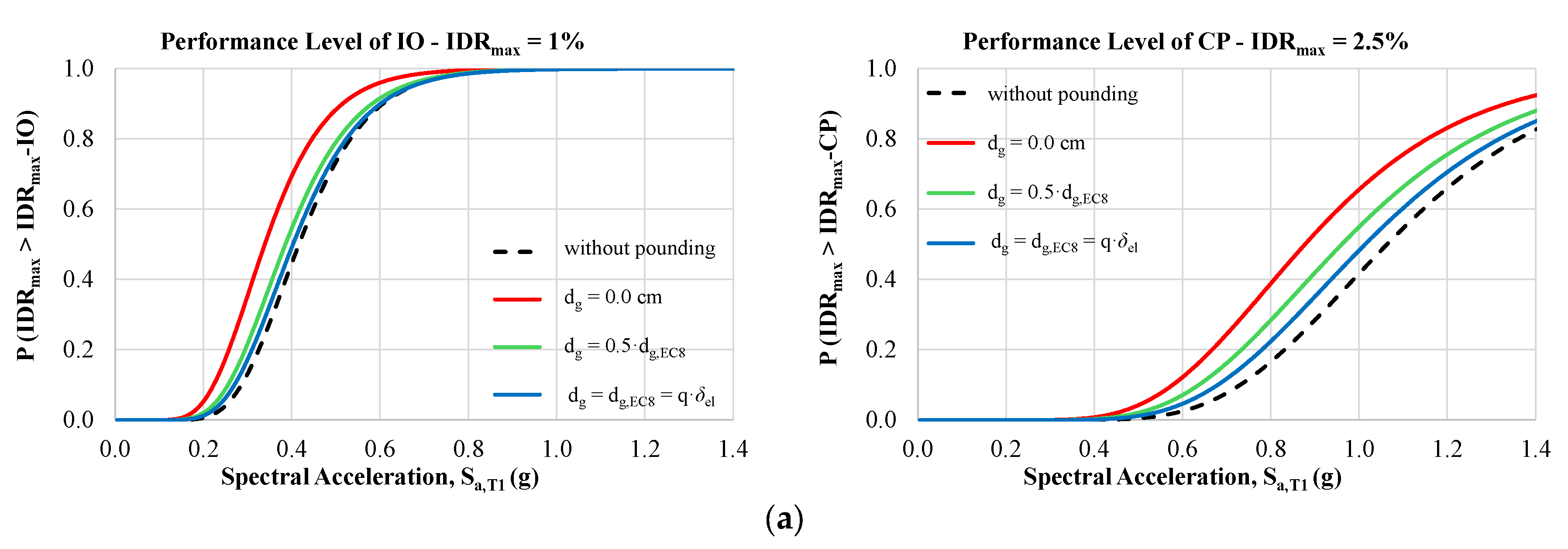

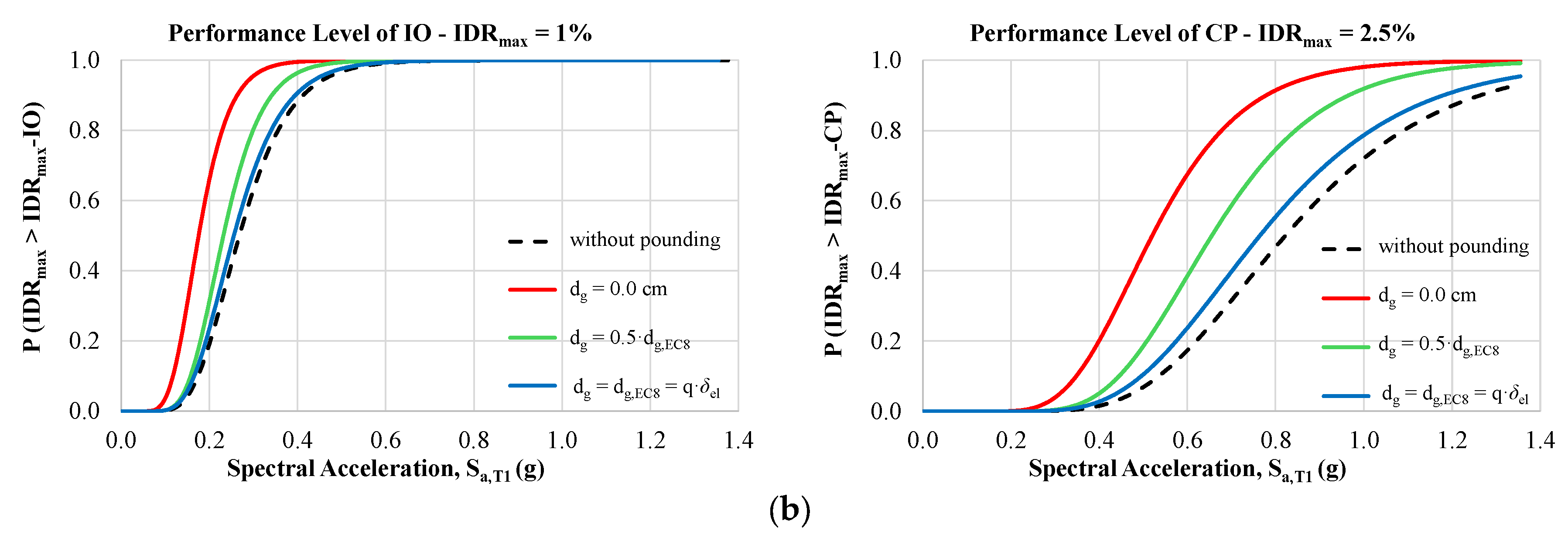

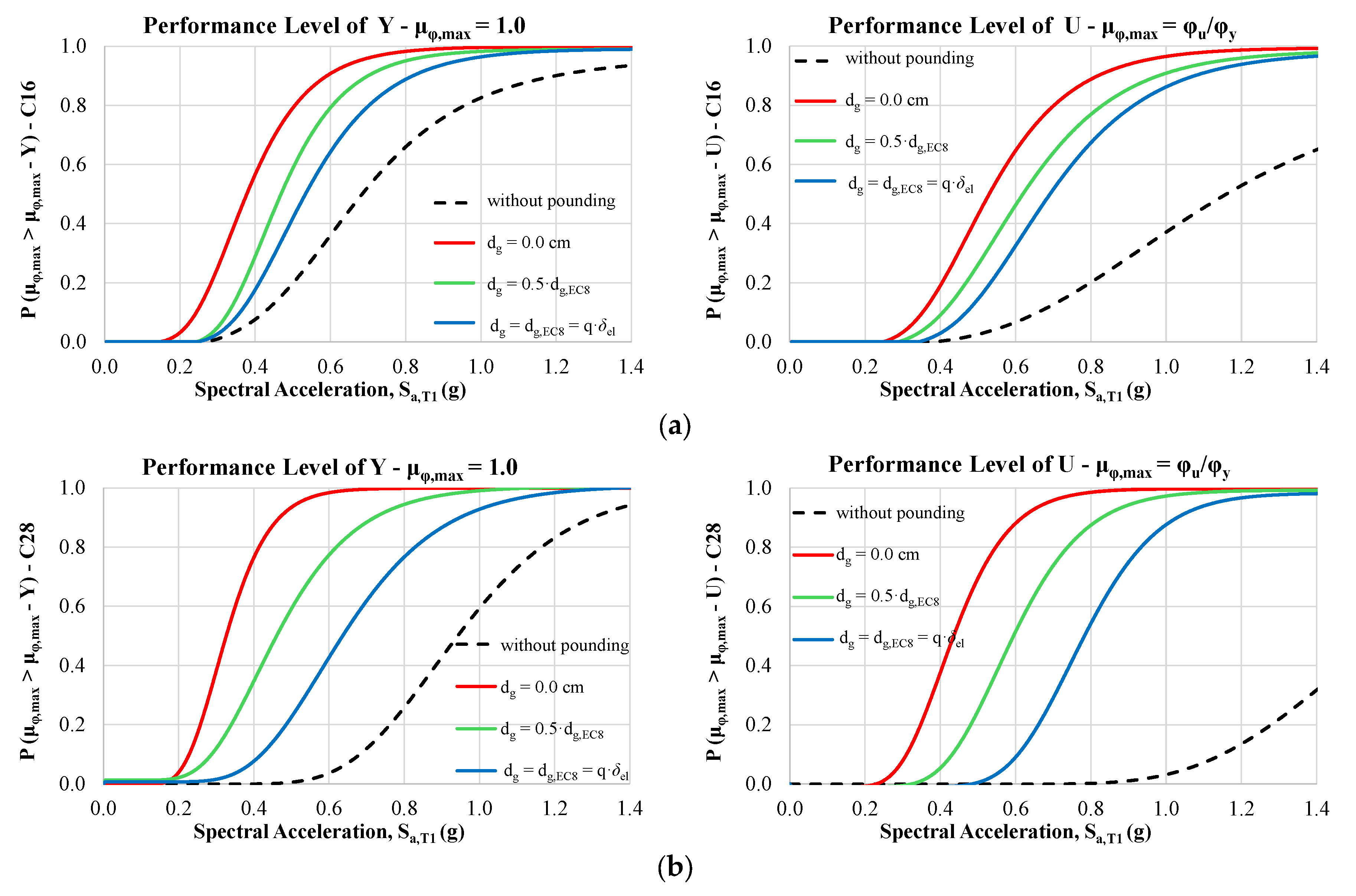

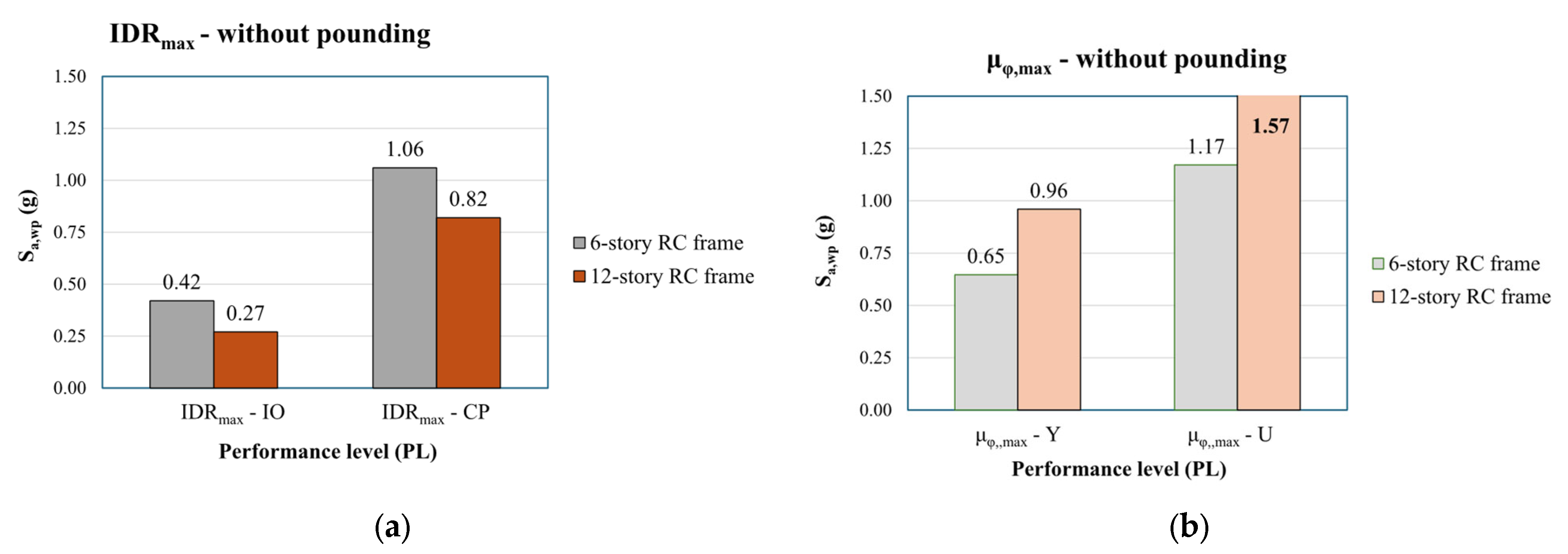

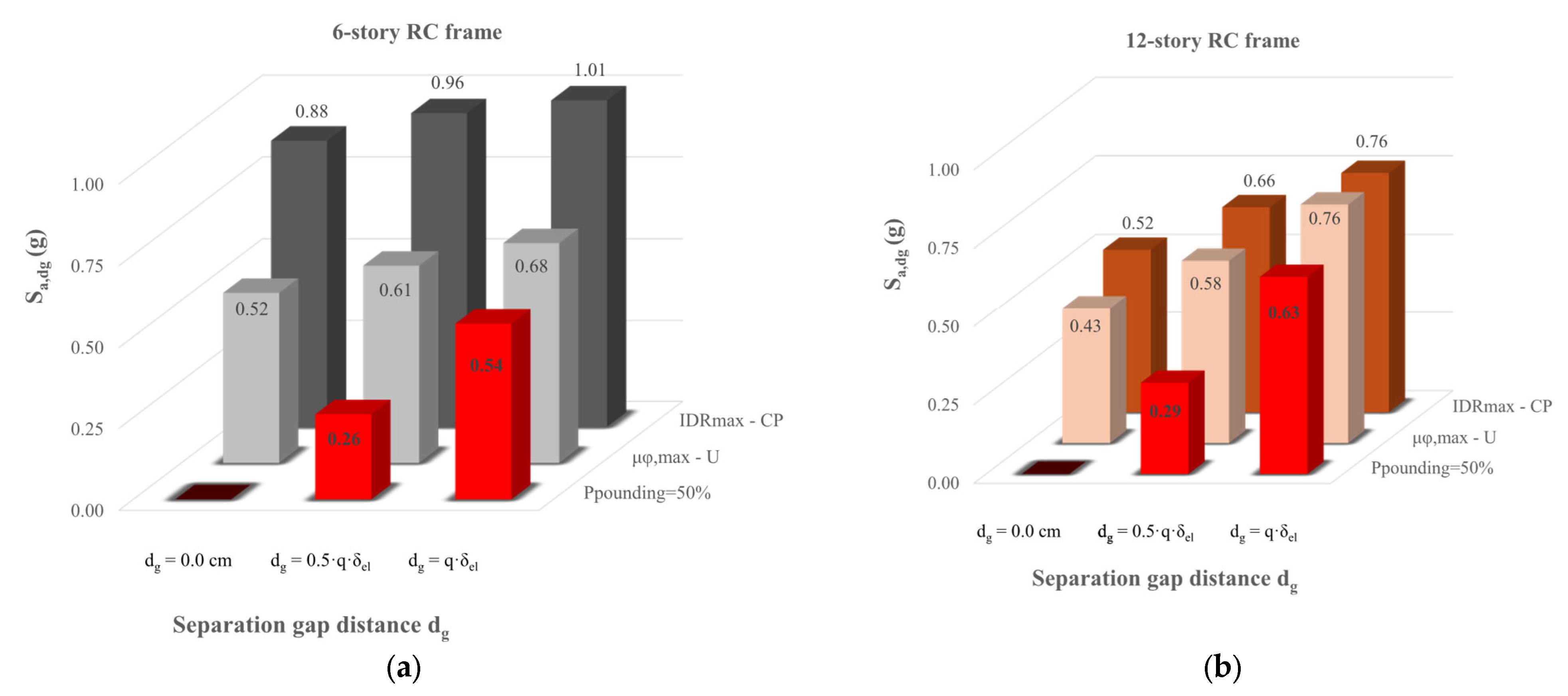

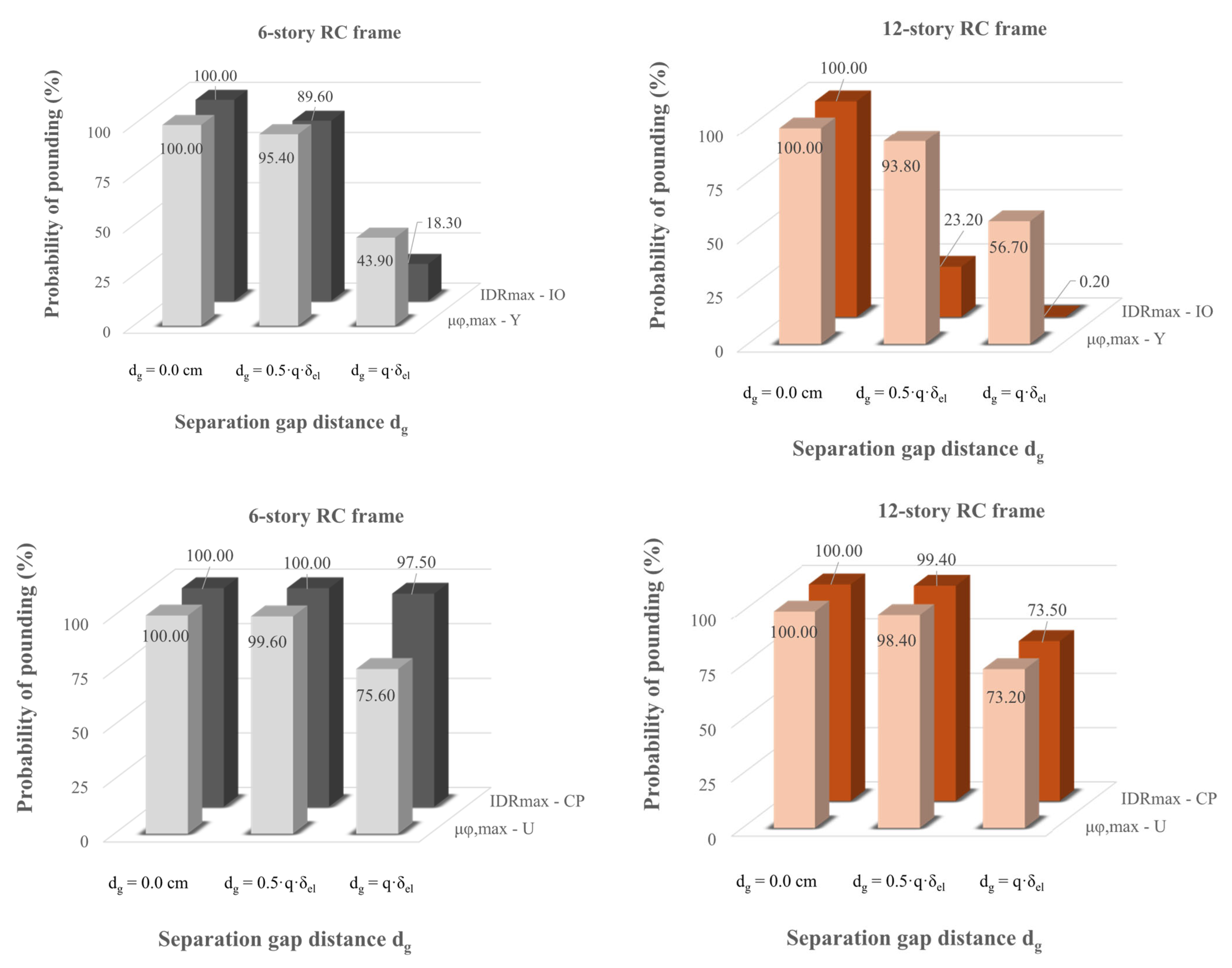

- The first observations align with existing knowledge on the seismic performance of structures under pounding conditions using probabilistic procedures. Indeed, fragility curves due to structural pounding configurations are shifted to lower values of Sa,T1 compared to the corresponding fragilities without pounding (free vibration of the structure). Also, as expected, the impact of the pounding on the vulnerability of the structures is increased as the initial gap distance dg between the adjacent structures is decreased. Evaluating the seismic performance of RC frames at different capacity levels, it can be stated that as the performance level becomes more demanding, the fragility curves shift towards higher values of Sa,T1.

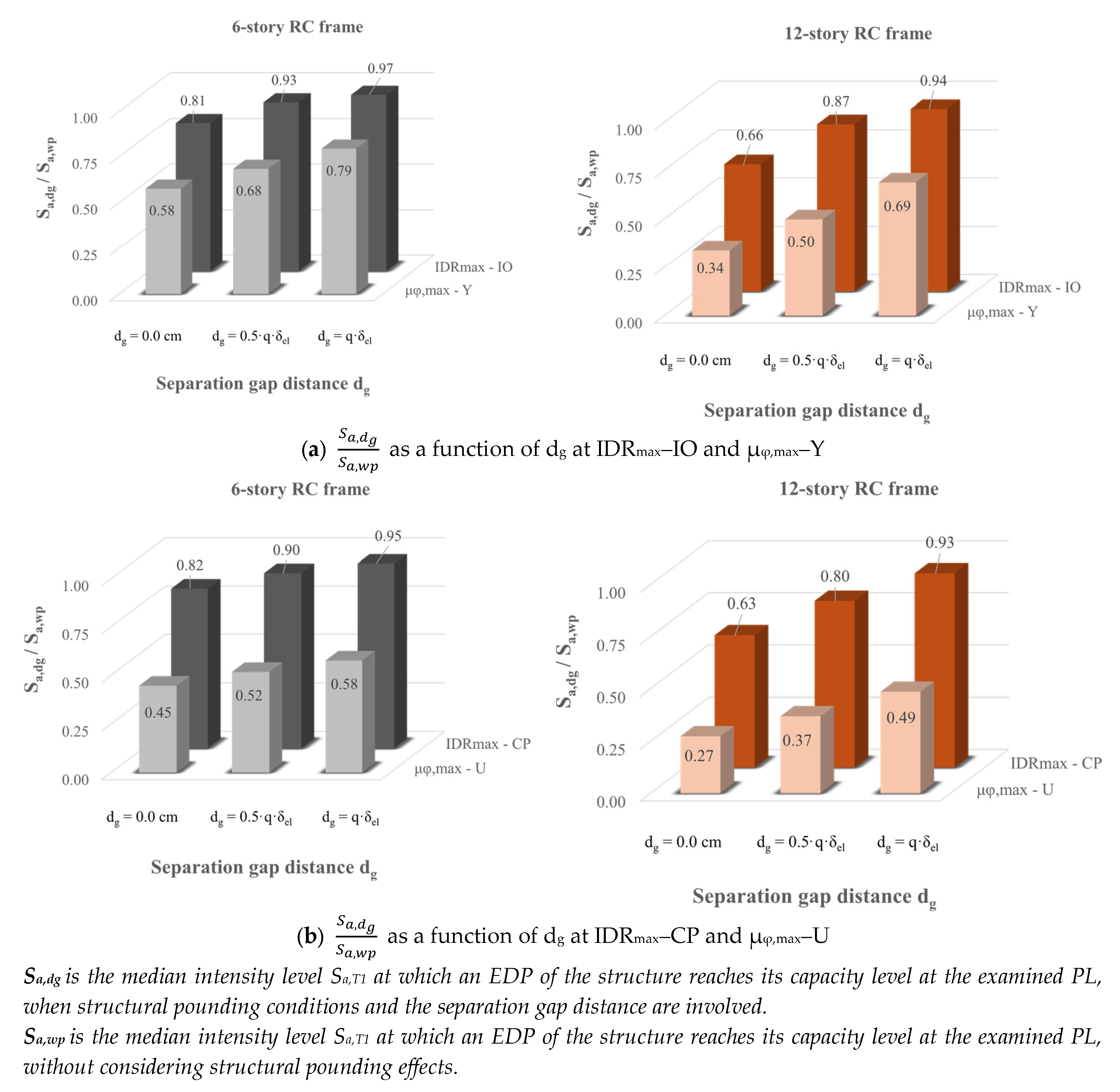

- Structural pounding significantly alters the seismic performance of structures compared to the case without pounding, making the ductility-based EDP, rather than the displacement-based EDP, the critical demand parameter for the evaluated RC frames.

- The use of the δmax (Ppounding) as a sole criterion to design and assess the structural pounding phenomenon yields conservative solutions.

- The structures reach their capacity level (examined PL) at an earthquake intensity level less than the expected one in the case of no pounding .

- An increase in stories from 6 to 12 decreases the ratio of . Therefore, the most critical pounding cases are posed on the twelve-story RC frames.

- The probability of pounding cannot be set to zero even when the gap distance provided by EC8 is applied.

- Excluding structural pounding consequences from the probabilistic frameworks may lead to unsafe performance-based seismic assessment or design provisions regarding the seismic risk of colliding buildings.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karayannis, C.G.; Favvata, M.J. Earthquake-induced interaction between adjacent reinforced concrete structures with non-equal heights. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2005, 34, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, S.A.; Spiliopoulos, K.V. An investigation of earthquake induced pounding between adjacent buildings. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1992, 21, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, S.A. Pounding of buildings in series during earthquakes. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1988, 16, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadrakakis, M.; Mouzakis, H.; Plevris, N.; Bitzarakis, S.A. Lagrange multiplier solution method for pounding of buildings during earthquakes. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1991, 20, 981–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassiadou, C.J.; Penelis, G.G.; Kappos, A.J. Seismic response of adjacent buildings with similar or different dynamic characteristics. Earthq. Spectra 1994, 10, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, S.E.A.; Fooly, M.Y.M.; Abdel Shafy, A.G.A.; Taha, A.M.; Abbas, Y.A.; Abdel Latif, M.M.S. Numerical simulation of potential seismic pounding among adjacent buildings in series. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 17, 439–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, A.; Mahmoud, S. Damage assessment of adjacent buildings under earthquake loads. Eng. Struct. 2014, 61, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efraimiadou, S.; Hatzigeorgiou, G.D.; Beskos, D.E. Structural pounding between adjacent buildings subjected to strong ground motions: Part I: The effect of different structures arrangement. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2013, 42, 1509–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, R. Assessment of damage due to earthquake-induced pounding between the main building and the stairway tower. Key Eng. Mater. 2007, 347, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, R. Non-linear FEM analysis of pounding-involved response of buildings under non-uniform earthquake excitation. Eng. Struct. 2012, 37, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, G.L.; Dhakal, R.P.; Turner, F.M. Building pounding damage observed in the 2011 Christchurch earthquake. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2012, 41, 893–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, R. Pounding between inelastic three-storey buildings under seismic excitations. Key Eng. Mater. 2016, 665, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, S.E.A. Mitigation measures for earthquake induced pounding effects on seismic performance of adjacent buildings. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2014, 12, 1705–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, D.R.; Wijeyewickrema, A.C. Structural performance of a base-isolated reinforced concrete building subjected to seismic pounding. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2012, 41, 1709–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatiwada, S.; Larkin, T.; Chouw, N. Influence of mass and contact surface on pounding response of RC structures. Earthq. Struct. 2014, 7, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miari, M.; Jankowski, R. Analysis of floor-to-column pounding of buildings founded on different soil types. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 20, 7241–7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favvata, M.J.; Karayannis, C.G.; Liolios, A.A. Influence of exterior joint effect on the inter-story pounding interaction of structures. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2009, 33, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoukas, G.; Karayannis, C. Asymmetric seismic pounding between multistorey reinforced concrete structures in a city block. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 177, 108415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoukas, G.; Karayannis, C. Biaxial seismic interaction of corner reinforced concrete buildings. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 23, 4755–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, E. Seismic pounding of adjacent buildings considering torsional effects. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 22, 2139–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favvata, M.J. Minimum required separation gap for adjacent RC frames with potential inter-story seismic pounding. Eng. Struct. 2017, 152, 643–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M. Code-based new approaches for determining the minimum required separation gap. Structures 2022, 46, 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tena-Colunga, A.; Sánchez-Ballinas, D. Required building separations and observed seismic pounding on the soft soils of City. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 161, 107413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miari, M.; Choong, K.K.; Jankowski, R. Seismic pounding between adjacent buildings: Identification of parameters, soil interaction issues and mitigation measures. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 121, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Elshaer, A. Pounding of structures at proximity: A state-of-the-art review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 48, 103991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajfar, P. Analysis in seismic provisions for buildings: Past, present and future. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2018, 16, 2567–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubaldi, E.; Freddi, F.; Barbato, M. Probabilistic seismic demand model for pounding risk assessment. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2016, 45, 1743–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazri, M.; Miari, M.A.; Kassem, M.M.; Tan, C.G.; Farsangi, E.N. Probabilistic evaluation of structural pounding between adjacent buildings subjected to repeated seismic excitations. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2018, 44, 4931–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flenga, M.G.; Favvata, M.J. Fragility curves and probabilistic seismic demand models on the seismic assessment of RC frames subjected to structural pounding. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flenga, M.G.; Favvata, M.J. Probabilistic seismic assessment of the pounding risk based on the local demands of a multistory RC frame structure. Eng. Struct. 2021, 245, 112789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flenga, M.G.; Favvata, M.J. Investigating the efficiency and the sufficiency of IMs for the probabilistic seismic assessment of the pounding effect between adjacent RC structures. In Proceedings of the 9th ECCOMAS Thematic Conference on Computational Methods in Structural Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering (COMPDYN 2023), Athens, Greece, 12–14 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Flenga, M.G.; Favvata, M.J. The effect of magnitude Mw and distance Rrup on the fragility assessment of a multistory RC frame due to earthquake-induced structural pounding. Buildings 2023, 13, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.; Romão, X. Seismic fragility functions for non-seismically designed RC structures considering pounding effects. Buildings 2021, 11, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, F.; Miari, M.; Jankowski, R. Investigating the effects of structural pounding on the seismic performance of adjacent RC and steel MRFs. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 19, 317–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miari, M.; Jankowski, R. Incremental dynamic analysis and fragility assessment of buildings founded on different soil types experiencing structural pounding during earthquakes. Eng. Struct. 2022, 252, 113118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.; Rao, B.N. Seismic fragility of non-ductile RC frames for pounding risk assessment. Structures 2023, 56, 104865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantilas, K.; Naoum, M.; Kavvadias, I.; Karayannis, C.; Elenas, A. Structural pounding effect on the seismic performance of a multistorey reinforced concrete frame structure. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, F.; Asgarkhani, N.; Manguri, A.; Jankowski, R. Seismic probabilistic assessment of steel and reinforced concrete structures including earthquake-induced pounding. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2024, 24, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1992-1-1; Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures. Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2002.

- EN 1998-1; Eurocode 8: Design of Structures for Earthquake Resistance. Part 1: General Rules, Seismic Actions and Rules for Buildings. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- Paulay, T.; Priestley, M.J.N. Seismic Design of Reinforced Concrete and Masonry Buildings; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, V.; Powell, G.H.; Gampbell, S. DRAIN-2DX Base Program Description and User’s Guide; UCB/SEMM Report No. 17/93; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.A.; Wu, Z.; Liu, S. Multivariate Probabilistic Seismic Demand Model for the Bridge Multidimensional Fragility Analysis. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 3443–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.A.; Wu, Z. Structural System Reliability Analysis Based on Improved Explicit Connectivity BNs. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 916–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.A.; Dai, Y.; Ma, Z.G.; Wang, J.F.; Lin, J.F.; Ni, Y.Q.; Ren, W.X.; Jiang, J.; Yang, X.; Yan, J.R. Towards high-precision data modeling of SHM measurements using an improved sparse Bayesian learning scheme with strong generalization ability. Struct. Health Monit. 2024, 23, 588–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applied Technology Council (ATC). Seismic Evaluation and Retrofit of Concrete Buildings; Report No. ATC-40; Applied Technology Council: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vamvatsikos, D.; Cornell, C.A. Incremental dynamic analysis. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2002, 31, 491–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PEER Ground Motion Database. Available online: http://peer.berkeley.edu/peer_ground_motion_database (accessed on 10 February 2017).

| Seismic Excitations | Duration (s) | Maximum Acceleration αmax (m/s 2) | Mw 3 | R | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component FN 1 | Component FP 2 | (km) | |||

| Italy Arienzo, 1980 (EQ283) | 24 | 0.268 | 0.405 | 6.9 | 52.9 |

| Italy Auletta, 1980 (EQ284) | 34 | 0.615 | 0.655 | 6.9 | 9.6 |

| Chi-Chi Taiwan-06, 1999 (EQ3479) | 42 | 0.073 | 0.070 | 6.3 | 83.4 |

| Denali-Alaska, 2002 (EQ2107) | 60 | 0.869 | 0.975 | 7.9 | 50.9 |

| Loma Prieta, 1989 (EQ804) | 25 | 1.090 | 0.509 | 6.9 | 63.1 |

| Chi-Chi Taiwan-04, 1999 (EQ2805) | 60 | 0.096 | 0.075 | 6.2 | 116.2 |

| San Fernando, 1971 (EQ59) | 14 | 0.153 | 0.181 | 6.6 | 89.7 |

| Pounding Case | RC Frame Structure | EDP = aΙΜb | βEDP|IM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| without pounding | 6-story | δmax = 0.096 Sa,T10.980 | 0.316 | |

| 12-story | δmax = 0.218 Sa,T10.913 | 0.291 | ||

| without pounding | 6-story | IDRmax = 2.354 Sa,T10.978 | 0.286 | |

| 12-story | IDRmax = 2.939 Sa,T10.819 | 0.275 | ||

| dg = 0.0 cm | 6-story | IDRmax = 2.835 Sa,T10.964 | 0.314 | |

| 12-story | IDRmax = 4.349 Sa,T10.845 | 0.266 | ||

| dg = 0.5·dg,EC8 | 6-story | IDRmax = 2.601 Sa,T11.005 | 0.322 | |

| 12-story | IDRmax = 3.633 Sa,T10.883 | 0.267 | ||

| dg = dg,EC8 | 6-story | IDRmax = 2.467 Sa,T10.994 | 0.310 | |

| 12-story | IDRmax = 3.133 Sa,T10.838 | 0.284 | ||

| without pounding | 6-story | μφ,max − C16 = 1.439 Sa,T10.836 | Sa,T1 ≤ 0.647 g | 0.222 |

| μφ,max − C16 = 1.632 Sa,T11.125 | Sa,T1 ≥ 0.647 g | 0.577 | ||

| 12-story | μφ,max − C28 = 1.050 Sa,T10.728 | Sa,T1 ≤ 0.960 g | 0.175 | |

| μφ,max − C28 = 1.075 Sa,T11.308 | Sa,T1 ≥ 0.960 g | 0.325 | ||

| dg = 0.0 cm | 6-story | μφ,max − C16 = 2.465 Sa,T10.914 | Sa,T1 ≤ 0.373 g | 0.289 |

| μφ,max − C16 = 7.000 Sa,T11.973 | Sa,T1 ≥ 0.373 g | 0.729 | ||

| 12-story | μφ,max − C28 = 2.430 Sa,T10.787 | Sa,T1 ≤ 0.325 g | 0.205 | |

| μφ,max − C28 = 13.929 Sa,T12.34 | Sa,T1 ≥ 0.325 g | 0.684 | ||

| dg = 0.5·dg,EC8 | 6-story | μφ,max − C16 = 2.173 Sa,T10.952 | Sa,T1 ≤ 0.443 g | 0.168 |

| μφ,max − C16 = 5.658 Sa,T12.128 | Sa,T1 ≥ 0.443 g | 0.866 | ||

| 12-story | μφ,max − C28 = 1.925 Sa,T10.882 | Sa,T1 ≤ 0.478 g | 0.387 | |

| μφ,max − C28 = 28.646 Sa,T13.355 | Sa,T1 ≥ 0.478 g | 1.004 | ||

| dg = dg,EC8 | 6-story | μφ,max − C16 = 1.831 Sa,T10.907 | Sa,T1 ≤ 0.514 g | 0.215 |

| μφ,max − C16 = 5.083 Sa,T12.441 | Sa,T1 ≥ 0.514 g | 0.970 | ||

| 12-story | μφ,max − C28 = 1.426 Sa,T10.809 | Sa,T1 ≤ 0.660 g | 0.290 | |

| μφ,max − C28 = 6.639 Sa,T14.513 | Sa,T1 ≥ 0.660 g | 1.206 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Favvata, M.J.; Tsiaga, E.G. Probabilistic IM-Based Assessment of Critical Engineering Demand Parameters to Control the Seismic Structural Pounding Consequences in Multistory RC Buildings. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031193

Favvata MJ, Tsiaga EG. Probabilistic IM-Based Assessment of Critical Engineering Demand Parameters to Control the Seismic Structural Pounding Consequences in Multistory RC Buildings. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031193

Chicago/Turabian StyleFavvata, Maria J., and Effrosyni G. Tsiaga. 2026. "Probabilistic IM-Based Assessment of Critical Engineering Demand Parameters to Control the Seismic Structural Pounding Consequences in Multistory RC Buildings" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031193

APA StyleFavvata, M. J., & Tsiaga, E. G. (2026). Probabilistic IM-Based Assessment of Critical Engineering Demand Parameters to Control the Seismic Structural Pounding Consequences in Multistory RC Buildings. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031193