1. Introduction

Clear aligner therapy (CAT) has gained widespread interest among patients, clinicians, and researchers due to its esthetic appeal, comfort, and evolving clinical applications [

1]. While the predictability of clear aligner treatment has been reported to be around 50%, a significant proportion of cases could still meet the high clinical standards required for American Board of Orthodontics (ABO) certification, with 74% of randomly selected cases from the same sample potentially achieving approval [

2].

A recent study by Upadhiyay and Arqub demonstrated that prioritizing tipping movements, minimizing the programmed displacement per aligner, and leveraging the shape-molding effect could enhance the overall efficiency of the system [

3]. Evidence suggests that, in cases of mild to moderate malocclusions, clear aligner therapy could achieve outcomes comparable to those of fixed appliances [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. While finite element method (FEM) studies are providing valuable insights into aligner deformation and biomechanics [

9,

10,

11,

12], high-quality clinical trials are still needed to validate these findings and assess their clinical relevance.

With clear aligner therapy emerging as a key component of modern orthodontic practice [

13,

14], its integration into postgraduate orthodontic curricula has become essential. Postgraduate education represents the primary prerequisite for clinical orthodontic training, and according to the World Federation of Orthodontists (WFO), an orthodontic residency program should include a minimum of 24 h of patient management, 6 h of didactic instruction, and 10 to 12 h of research per week [

15,

16].

A similar structure is emphasized in Europe, where the Network of Erasmus-Based European Orthodontic Postgraduate Programmes (NEBEOP) sets standards for postgraduate education [

17]. The curriculum requires 4800 training hours over three years, including supervised treatment of at least 50 cases, ensuring a balanced focus on theoretical knowledge, clinical expertise, and research [

17].

However, a recent survey revealed that 42% of orthodontists interviewed had not treated any clear aligner cases during their postgraduate training [

18], highlighting a potential gap in education regarding this increasingly relevant treatment modality.

Despite the growing number of publications from international institutions on aligner orthodontics [

1], the impact of operator experience on treatment outcomes remains unexplored. Assessing treatment effectiveness enables postgraduate students to evaluate their own cases and enhance their clinical proficiency [

19]. Maintaining high-quality training in postgraduate programs is essential to ensure that graduates can deliver optimal treatment. Evaluating the quality of aligner therapy not only provides insight into the skills acquired during residency but also into the consistency and safety of treatment planning within a standardized educational framework. Within this structure, residents develop their treatment plans independently, while an experienced orthodontist performs a standardized, non-intervention review before treatment initiation to ensure patient safety without influencing the biomechanical strategy.

Although numerous studies have focused on the predictability of tooth movement [

20,

21,

22], the role of operator experience remains particularly relevant, especially in light of marketing strategies encouraging general dentists to incorporate aligners into orthodontic treatment. Notably, rotational movements of rounded teeth and vertical movements of both anterior and posterior teeth pose significant challenges in aligner therapy [

23].

This retrospective observational study aimed to evaluate whether operator experience influences the predictability of orthodontic tooth movements and the overall treatment duration in clear aligner therapy, by comparing clinical outcomes between postgraduate orthodontic students and experienced orthodontists.

The null hypothesis (H0) stated that no significant differences would be observed in the predictability of orthodontic movements with clear aligner treatment concerning both the quality of clinical outcomes and treatment duration.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective observational study was conduct in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [

24] at the Dental School of the University of Turin, Italy, and in private orthodontic settings. Clinical records of patients treated with clear aligners were reviewed, with data collection covering treatments completed between March 2021 and December 2024.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) patients had to present a complete permanent dentition, with the possible exclusion of third molars; (b) treatment had to be a non-extraction clear aligner approach in both arches; (c) patients were required to complete the first set of aligners without requesting additional aligners; (d) a 1- to 2-week aligner change protocol had to be followed; (e) no combined treatment with fixed braces, intraoral distalizers, or other auxiliary appliances was permitted; and (f) only patients demonstrating good compliance were included.

Exclusion criteria included (a) the need for oral or maxillofacial surgery or restorative dental procedures during treatment, (b) failure to complete the first set of aligners, and (c) poor patient cooperation.

Patients were divided into two groups based on operator experience, defined by their level of clinical training and exposure to clear aligner therapy.

Group B (Beginners) included individuals treated by five postgraduate orthodontic students in their final year at the Orthodontic Graduate School of the University of Turin. These students had received 48 h of didactic instruction on clear aligner treatment as part of their curriculum and, in their second year, had started treating at least three patients, each with clear aligners under supervision. Additionally, they attended a master course in aligner orthodontics at their institution, which consisted of four one-week modules over the course of a year, featuring lectures by internationally recognized experts and chairside training under the guidance of an experienced supervisor.

Group E (Experts) consisted of patients treated by five experienced orthodontists, each with more than 10 years of clinical orthodontic experience. These practitioners had treated more than 500 clear-aligner cases in their private practices, demonstrating a high level of expertise in aligner-based orthodontic treatment.

In both groups, all clinicians followed the same standardized digital workflow and institutional treatment protocol. The unit of comparison was therefore the experience level, not the individual operator. Because clinicians within each group adhered to identical procedures, additional calibration between individual operators was not required.

All patients presented with Class I or mild Class II malocclusion, with mild-to-moderate crowding or spacing in both arches and mild-to-no overbite correction needs. Chewies and intermaxillary elastics were not used during treatment. When prescribed, interproximal enamel reduction (IPR) was performed exclusively in the anterior region (canine to canine) and was limited to 0.3 mm per interproximal space.

Virtual treatment plans were developed using ClinCheck

® Pro 6.0 software (Align Technology Inc., San José, CA, USA). Before treatment planning, the virtual models were oriented according to the patient’s natural occlusal plane, using lateral and frontal radiographs together with facial photographs as reference [

25]. All treatments were carried out using the same aligner system and a uniform digital workflow. No changes in aligner material, manufacturing process, or software environment occurred during the data collection period, thereby ensuring full methodological consistency across all cases. Before treatment initiation, all virtual treatment plans underwent a blinded safety screening performed by an experienced orthodontist who was not involved in treatment execution. This review was strictly limited to identifying gross planning errors that could potentially compromise patient safety (e.g., biologically implausible movements, extreme staging, or software-related artifacts). No assessment of treatment quality or optimization was performed, and no feedback, recommendations, or corrective actions were provided. Importantly, even when suboptimal but biologically acceptable planning choices were identified, they were not modified. Biomechanics, staging, attachment design, and movement prescriptions remained entirely as planned by the treating clinician. This approach ensured patient safety while preserving the independence of treatment planning and allowing operator experience to be evaluated without expert interference.

Accordingly, all treatment plans in the Beginner group were prepared entirely and independently by the postgraduate residents, and the level of oversight remained identical for all cases in both groups. All outcome measurements were performed on anonymized STL models that did not contain any information identifying either the patient or the treating operator; therefore, the examiner was fully blinded during the measurement phase.

Patient compliance with aligner wear was assessed at each follow-up visit and further supported by a self-reported wear chart completed by patients. Compliance was categorized into three levels: compliant (reported wear of aligners as advised), partially compliant (instructions not followed precisely), and noncompliant (not wearing the aligners). Patients classified as noncompliant based on these criteria were excluded according to the study’s eligibility criteria.

The primary outcome of the study was the difference between the predicted and achieved tooth position, measured as lack of movement (LM) and expressed as a continuous variable in degrees or millimeters. Secondary outcomes included treatment duration and the predictability of specific orthodontic movements, such as rotation, angulation, and vertical displacement.

The primary exposure variable was operator experience, categorized as treatment performed by either postgraduate orthodontic students (Group B) or experienced orthodontists (Group E). Other covariates considered in the analysis included tooth type, movement type, and treatment difficulty score, which was used to ensure comparability between the two groups.

Based on a previous study [

26], thresholds of 0.5 mm for linear measurements and 2° for angular movements were predefined to distinguish clinically relevant from clinically irrelevant discrepancies. Statistically significant differences below these thresholds were therefore interpreted as having limited clinical impact.

Case complexity was quantified using a treatment-difficulty score derived from the key components of the

Index of Complexity, Outcome and Need (ICON) [

27]—including upper-arch crowding or spacing, crossbite presence, buccal-segment sagittal relationship, anterior vertical discrepancy, and esthetic component. These parameters were scored on a standardized internal scale (0–10), with higher values indicating greater biomechanical challenge.

This ICON-derived score was used solely to compare baseline case severity between groups.

To reduce potential bias, strict inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, and both groups were balanced for case complexity using the treatment difficulty score. All digital measurements were performed on anonymized STL models, with the examiner blinded to operator group, to limit measurement bias. Intra- and inter-examiner reliability were verified to ensure consistency of measurements. Potential confounding factors, such as tooth type and movement category, were addressed by stratifying the analyses accordingly. Due to the retrospective design, no randomization or multivariable adjustment was feasible, and these aspects were acknowledged among the study limitations.

Digital records were obtained from the clinicians’ Invisalign® platform, and digital models were exported from ClinCheck® software (Align Technology Inc., San José, CA, USA) as stereolithographic (STL) files, a standard format used for three-dimensional (3D) surface geometry representation. The final models from the initial virtual setup were labeled as “predicted models”, while the models generated at the beginning of the refinement phase or at the end of the treatment were labeled as “achieved models”, as they represented the actual post-treatment outcome.

All digital models were anonymized, and soft tissues were removed using Geomagic Control X 2024.2 (3D Systems, Rock Hill, SC, USA) to ensure that measurements were based exclusively on the dental surfaces. To facilitate comparative analysis, post-treatment models were segmented, allowing for individual tooth-level comparisons with their corresponding unsegmented virtual treatment plan models.

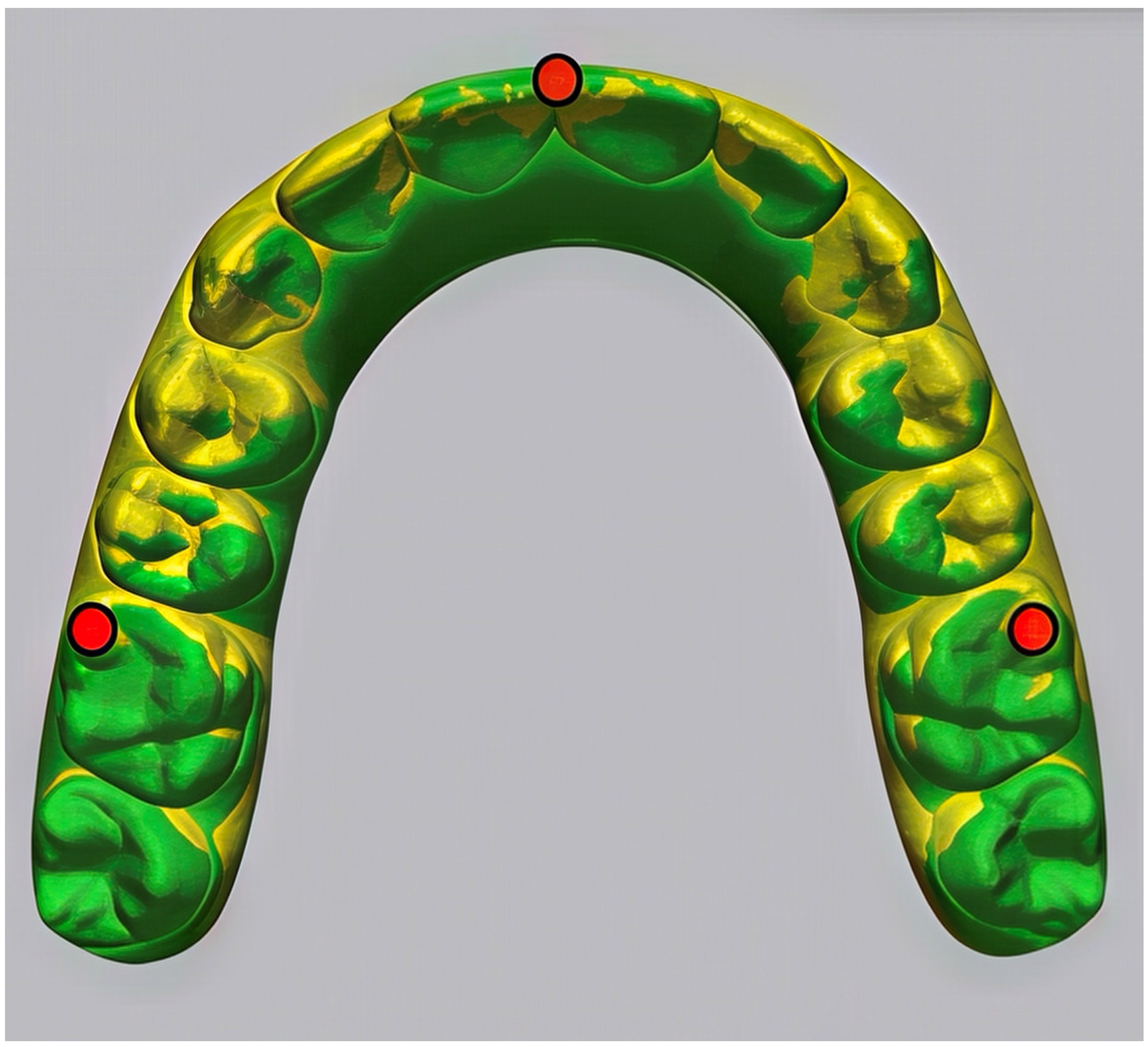

Superimposition techniques were applied to assess the discrepancies between the predicted and achieved tooth positions (

Figure 1).

Two methods were employed:

Landmark-based superimposition, using as anatomical references the mesiobuccal cusps of the first molars and the mesial-incisal edge of the right central incisor.

Surface-based superimposition (Best Fit Alignment), which aligned the models based on the overall morphology of the dental surfaces.

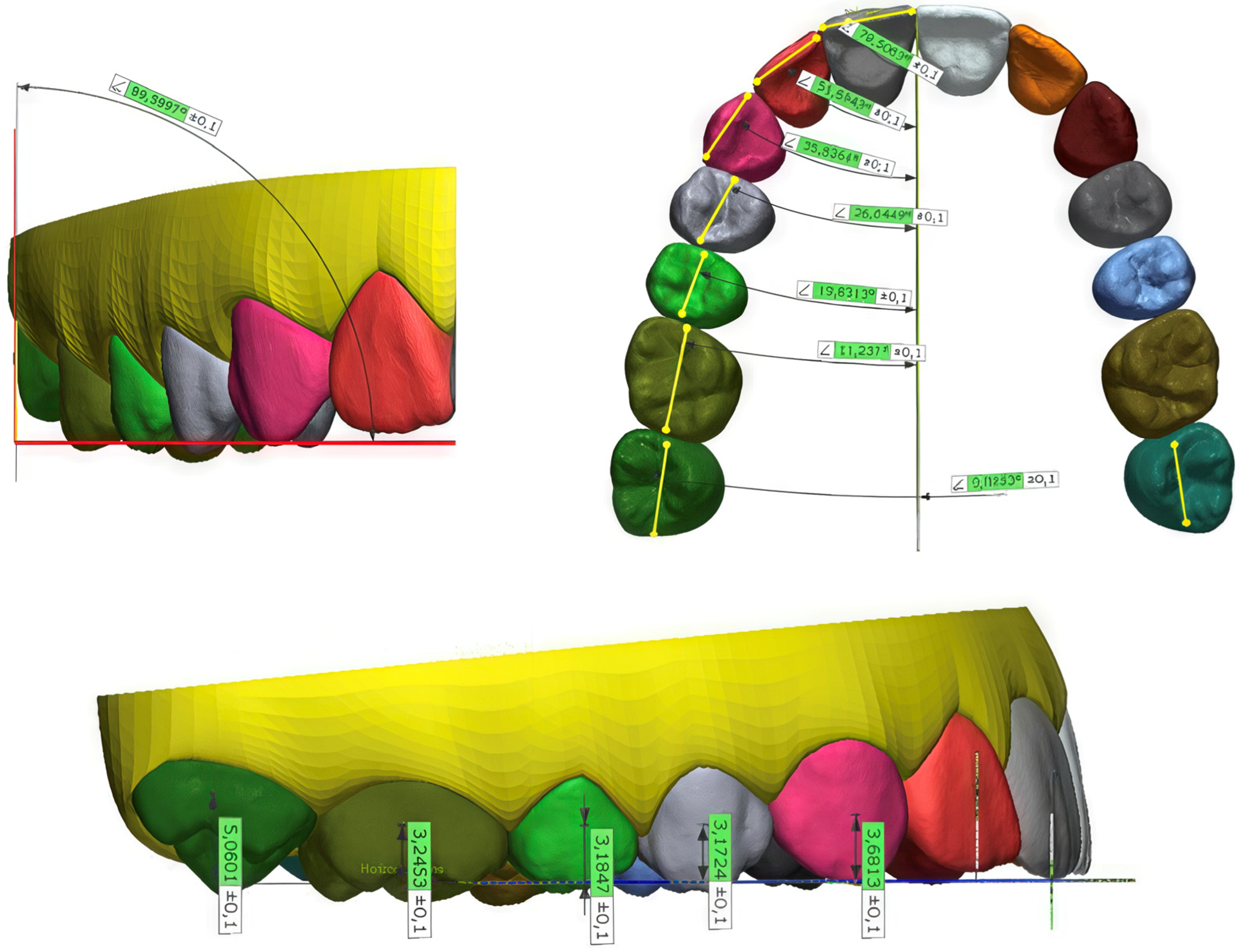

As described by Castroflorio et al. [

23], three reference planes (occlusal, coronal, and median) were defined on the virtual treatment plan model. Linear tooth movements—including mesiodistal, vertical, and buccolingual/palatal displacements—were calculated based on FA points. Angulation and inclination were determined using FACC (Facial Axis of the Clinical Crown) l andmarks, while rotation was quantified by the vector created between the distal and mesial reference points (

Figure 2).

Each post-treatment model was segmented, allowing individual teeth to be superimposed on their corresponding elements in the non-segmented virtual treatment plan using the Best Fit surface-based registration method. The final discrepancies between the achieved and predicted positions of each tooth were then computed.

All post-treatment measurements were performed by a single calibrated examiner on anonymized STL models. Before measurement, each file was re-coded with a random numeric identifier to ensure that the examiner was blinded to group allocation (Beginner vs. Expert) and patient identity.

To assess intra-examiner reliability, the same operator repeated twenty measurements per movement type (total = 240) after a three-week interval using the same workflow and software settings.

Inter-examiner reliability was evaluated on a random 15% subsample of cases by a second examiner following the same protocol. Both examiners were trained using a standardized calibration dataset to minimize systematic bias.

The following variables were considered: angulation (mesiodistal inclination), inclination (buccolingual/palatal inclination), rotation, mesiodistal movement (distance between the FA points and the coronal plane), vertical movement (distance between the FA points and the occlusal plane), and buccolingual/palatal movement (distance between the FA points and the midplane).

According to Grünheid et al. [

26], a marginal ridge discrepancy of 0.5 mm corresponds to a crown-tip deviation of 2° for an average-sized molar. Therefore, discrepancies ≥0.5 mm or more in mesiodistal, buccolingual/palatal, and occlusal-gingival directions, as well as angular discrepancies ≥2° or more in angulation, inclination, and rotation, were considered clinically relevant.

The analysis focused on movement categories recognized in the previous literature as difficult to achieve predictably with clear aligner systems, particularly rotational movements of rounded teeth and vertical control of anterior and posterior segments [

2,

3].

As this was a retrospective observational investigation including all eligible cases from the institutional and private-practice databases, an a priori sample size calculation was not applicable, in accordance with STROBE recommendations for retrospective cohort designs [

24]. Instead, a post hoc, precision-based assessment was performed to determine whether the final sample provided adequate statistical sensitivity.

Based on the observed standard deviations and effect sizes for the primary outcomes, the available cohort of 72 patients yielded >80% power to detect between-group differences at or above the established thresholds for clinical relevance—0.5 mm for linear discrepancies and 2° for angular discrepancies, as previously validated in clear-aligner predictability studies [

26]. Using α = 0.05, these metrics indicate that the sample size was sufficient for the comparisons conducted.

For statistical processing, the initial raw data for both the virtual position values and LM (lack of movement) difference values were aggregated into representative averages for different groups of teeth in each patient. The following tooth groups were analyzed: maxillary central incisors (U1), maxillary lateral incisors (U2), maxillary canines (U3), maxillary premolars (U4–5), maxillary first molars (U6), maxillary second molars (U7), mandibular incisors (L1–2), mandibular canines (L3), mandibular premolars (L4–5), mandibular first molars (L6), and mandibular second molars (L7). The expected orthodontic movements were categorized into six types, grouped as angular movements (tilt, angulation, and rotation) and linear movements (mesiodistal, vertical, and buccolingual/palatal). The primary exposure variable was operator experience, defined as treatment performed by either expert orthodontists (Group E) or postgraduate orthodontic students (Group B).

The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the LM variable, confirming that the data did not follow a normal distribution (p < 0.05). Therefore, comparisons between groups were conducted using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test. The level of statistical significance was set at α = 0.05. Data were analyzed using Stata software (version 17; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Because of the 1:1 parallel cohort design and the matching based on the treatment difficulty score, the two groups were reasonably comparable in baseline case complexity. No missing data occurred for the included variables, as all patient records were complete and met the eligibility criteria. Given the limited sample size, no multivariable adjustment was performed; however, analyses were stratified by tooth type and movement category to account for potential confounding. No formal sensitivity analyses were conducted because of the limited sample size; this limitation was acknowledged in the Discussion.

Given the exploratory nature of the study and the limited sample size, no formal adjustment for multiple comparisons was applied; p-values should therefore be interpreted descriptively and in conjunction with effect sizes and the predefined thresholds for clinical relevance (0.5 mm for linear movements and 2° for angular movements).

3. Results

The analyzed sample comprised 72 patients (22 men and 50 women; median age, 24.6 years; IQR = 5.9).

A total of 92 clinical records were initially screened from both the university and private-practice databases. Twenty patients were excluded because of incomplete digital records (n = 7), combined treatment with auxiliaries or fixed appliances (n = 5), or poor compliance (n = 8).

The final sample included 72 eligible patients, evenly distributed between the Beginners (Group B) and Experts (Group E) cohorts.

The ICON-derived difficulty score was comparable between groups (Group B: 6.1 ± 1.4; Group E: 6.0 ± 1.5; p = 0.78), confirming similar baseline case complexity. All included cases fell within the range corresponding to mild to moderate malocclusion, in line with the predefined inclusion criteria.

The total treatment duration was significantly longer in the beginner group (B), with a median increase of 4.1 months (95% CI [1.4, 6.8]; p = 0.0037 *) compared to the expert group (E). The median treatment duration was 23.4 months in Group B and 19.3 months in Group E.

The intra-examiner ICC was 0.99, indicating excellent repeatability, and the inter-examiner ICC ranged 0.93–0.97 across angular and linear measurements, confirming high reproducibility.

Significant differences emerged between the two groups in terms of prescribed movement and lack of correction (LM), particularly for specific tooth categories (

Table 1).

Although several between-group differences reached statistical significance, most discrepancies remained below the thresholds for clinical relevance (0.5 mm for linear movements and 2° for angular movements).

Regarding angulation, the prescribed movement was significantly higher among experts for maxillary canines (median = 3.2°; IQR = 2.9) compared to beginners (median = 1.83°; IQR = 1.95; p = 0.04), as well as for mandibular premolars, where experts prescribed a median of 4.8° (IQR = 3.08) while beginners prescribed 2.83° (IQR = 3.00; p = 0.02). However, after treatment, the amount of correction loss was comparable in both groups.

For mandibular molars, the prescribed movement was similar in both groups, but the lack of correction was significantly higher in the beginner group. The first mandibular molars had a median correction deficit of 2.24° (IQR = 2.12) in group B compared to 1.72° (IQR = 1.70) in group E (p = 0.04 *), while for the second mandibular molars, the correction loss reached 3.04° (IQR = 1.62) in group B versus 1.76° (IQR = 1.93) in group E (p = 0.01 *).

Regarding inclination, the maxillary premolars exhibited significantly less loss of correction in group B, where the median correction deficit was 2.41° (IQR = 2.82), compared to 4.73° (IQR = 3.21) in group E (p = 0.03 *), despite similar prescribed movement among all patients.

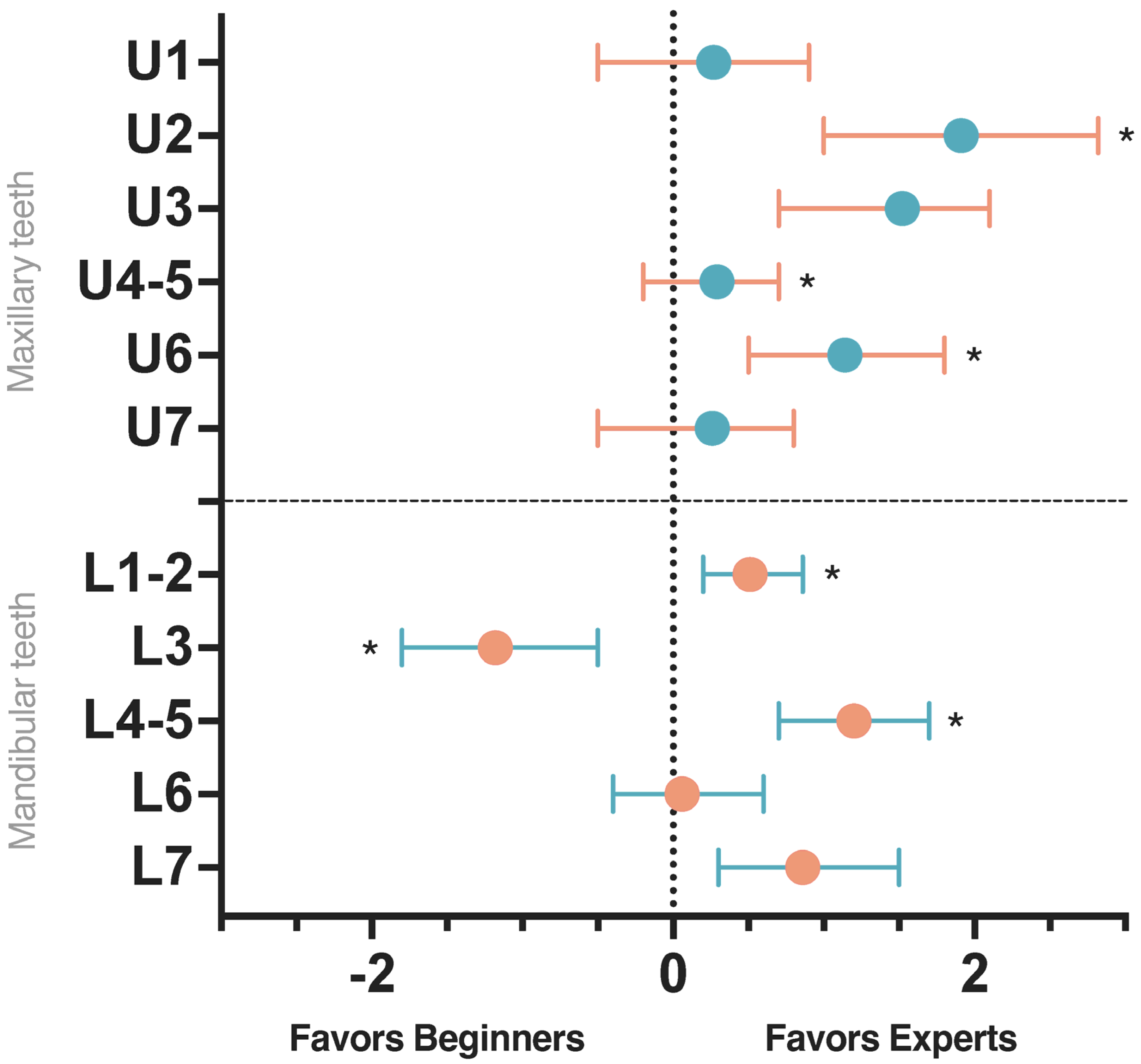

When analyzing rotations, significant differences were observed for maxillary first molars, mandibular incisors, canines, premolars, and second molars (

Figure 3). Experts demonstrated less lack of correction on maxillary first molars (median = 1.06°; IQR = 1.44) compared to beginners (median = 2.20°; IQR = 2.11; Δ = 1.14°; 95% CI [0.02, 2.26];

p = 0.045). Similarly, for mandibular premolars the median rotational discrepancy was 3.26° (IQR = 3.35) in group E versus 4.46° (IQR = 4.04) in group B (Δ = 1.20°; 95% CI [0.25, 2.15];

p = 0.046).

Additional differences were found for mandibular incisors (2.45° in B vs. 1.94° in E; Δ = 0.51°; 95% CI [0.22, 0.80]; p = 0.001) and mandibular canines (2.21° in B vs. 3.39° in E; Δ = −1.18°; 95% CI [−1.90, −0.46]; p = 0.03), indicating that experts achieved better rotational control in incisors, whereas beginners performed slightly better for canines.

A further difference was noted for upper lateral incisors, with experts achieving a lower median discrepancy (2.81° in E vs. 4.72° in B; Δ = 1.91°; 95% CI [0.70, 3.12]; p = 0.03), confirming superior rotational control. However, most of these between-group differences were below the predefined clinical-relevance threshold of 2°, indicating limited clinical impact.

For mesiodistal translation, a small but significant difference was found in the predicted movement of the maxillary second molar, where patients in group B had a median prescribed movement of 0.40 mm (IQR = 0.55), compared to 0.08 mm (IQR = 0.60) in group E (p = 0.04). However, the final correction loss was similar between groups.

Regarding vertical translation (

Table 2), significant differences were identified for maxillary central incisors, where the correction deficit was greater in group B (median = 0.42 mm; IQR = 0.36) than in group E (median = 0.22 mm; IQR = 0.23; Δ = 0.20 mm; 95% CI [0.05, 0.35];

p = 0.01). Conversely, for upper premolars, beginners exhibited a smaller vertical discrepancy (median = 0.28 mm; IQR = 0.21 vs. 0.41 mm; IQR = 0.25; Δ = −0.13 mm; 95% CI [−0.22, −0.04];

p = 0.01), suggesting a more conservative and effective staging strategy. These differences, although statistically significant, remained below the 0.5 mm threshold for clinical relevance.

For buccolingual translation, differences were observed in maxillary first and second molars, with higher missed-correction values in group B (median = 0.45 mm; IQR = 0.28 for first molars and 0.51 mm; IQR = 0.34 for second molars) compared to group E (0.25 mm; IQR = 0.24 and 0.32 mm; IQR = 0.34, respectively). However, these differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.07). Conversely, for mandibular incisors, the extent of prescribed movement was significantly greater in group E (median = 1.23 mm; IQR = 0.84) compared to group B (median = 0.65 mm; IQR = 1.13; p = 0.02), though the final correction loss was similar across all patients.

4. Discussion

The integration of 3D technology has significantly enhanced orthodontic treatment planning. However, predicting tooth movement through algorithm-based simulations does not guarantee its clinical reproducibility. Several movement types continue to show limited predictability. Among the key factors influencing these discrepancies are tooth morphology, direction of movement, and the design and positioning of attachments, all of which play a crucial role in determining the predictability of tooth displacement [

23,

28,

29,

30].

The present findings show that operator experience influences the predictability of specific tooth movements and the efficiency of clear aligner therapy, although the magnitude of most discrepancies remained below the predefined thresholds for clinical relevance (0.5 mm and 2°). Expert clinicians achieved statistically superior performance in several movement categories and shorter treatment durations; however, these differences were generally small in magnitude and often clinically negligible, reinforcing that operator experience affects movement expression primarily within a limited clinical range.

Taken together, these results indicate that operator experience has a measurable effect on the precision of movement expression, but its impact on the final clinical outcome is limited. Based on these findings, the null hypothesis is rejected.

Although several between-group comparisons reached statistical significance, the magnitude of most discrepancies remained below established thresholds for clinical relevance (0.5 mm for linear movements and 2° for angular movements). For example, the vertical discrepancy of the maxillary central incisors was significantly greater in the beginner group compared to experts (Δ = 0.20 mm; p = 0.01), yet this difference was well below the 0.5 mm threshold considered clinically meaningful. Similarly, the rotational discrepancy of mandibular incisors differed significantly between groups (Δ = 0.51°; p = 0.001), but the absolute magnitude of this difference did not exceed the 2° clinical relevance threshold. These findings indicate that statistical significance does not necessarily translate into clinically perceptible differences, underscoring the importance of interpreting digital discrepancies in light of predefined clinical thresholds rather than p-values alone.

Although experienced clinicians demonstrated greater predictability in controlling specific movements, this does not imply that their results were optimal. Similarly to the beginner group, the most pronounced lack of correction was observed in rotational movements, particularly in mandibular incisors, consistent with the well-documented biomechanical challenges associated with narrow-rooted teeth.

Interestingly, for mandibular canines, the beginners showed significantly lower rotational discrepancies, suggesting more effective expression of planned movement (p = 0.03). Regarding premolars, LM for upper premolars was significantly lower in the expert group (p = 0.04), indicating better rotational control compared to beginners.

The correction of incisor rotation is a key objective in resolving mandibular crowding. While clear aligners have demonstrated high predictability [

31], our findings confirm that clinician experience in chairside case management and accuracy in interproximal reduction (IPR) remain critical factors.

The rotation of rounded teeth, such as premolars and canines, remains particularly challenging [

2,

32], especially when rotations exceed 15° [

30,

33]. Despite the introduction of optimized attachments, certain designs appear less effective in clinical practice [

23]. Vertical rectangular attachments, due to their larger flat surface, have shown better performance than optimized designs, although they are also associated with greater side effects [

30]. In this context, our findings further support the need for conservative activation (<1° per aligner) and careful selection of attachment design to improve rotational predictability.

Beyond attachment shape and size, aligner deformation plays a crucial role in rotational control. To improve predictability, it seems advisable to reduce activation to <1° per aligner, use vertical rectangular attachments on the target tooth and adjacent teeth to enhance anchorage, and better manage aligner deformation, as suggested by Cortona et al. [

34]. Additionally, considering the findings of Ferlias et al. [

35], which highlighted the side effects of vertical attachments in rotational movements, careful monitoring of patients receiving this type of attachment is recommended.

Experts also showed significantly better performance in controlling the rotation of upper lateral incisors (p = 0.03), a movement often underreported but biomechanically challenging due to root morphology and limited attachment surface.

An observation of interest in our study concerned the predictability of inclination and vertical movements of upper premolars. Beginners achieved significantly better control of both inclination and vertical movements of upper premolars, likely reflecting a more conservative and staged approach to movement planning. These findings suggest that conservative staging may occasionally compensate for limited experience, particularly for vertical and inclination movements in premolars.

A previous study from our group, which analyzed the predictability of orthodontic movement with aligners [

23], identified premolars and molars as the most difficult teeth to control in vertical displacement. Premolar extrusion is often poorly expressed, primarily due to the occlusal coverage of aligners, which prevents passive settling into occlusion, unlike what occurs with fixed appliances. Goh et al. reported an average accuracy of 24–43% for lower premolar extrusion in deep bite cases [

35]. Based on these findings, it appears that the introduction of G5 optimized attachments has not significantly improved the clinical predictability of premolar extrusion [

35]. Consequently, previous studies have suggested overcorrection as a compensatory approach [

36,

37]. Conversely, premolar intrusion has received limited attention in the literature. Some studies have described posterior tooth intrusion, but primarily as an incidental effect of occlusal coverage or as a secondary consequence of craniofacial divergence, rather than as a planned movement [

38,

39]. Our results extend these observations by showing that operator experience produces only small improvements in the vertical control of these difficult movements, with most differences remaining below clinically relevant thresholds.

Given the challenges associated with vertical movements of posterior teeth, it is important to note that when root tip or rotations exceed 5°, the ClinCheck

® software (Align Technology, San José, CA, USA) automatically assigns smaller, optimized attachments to address these issues. However, these optimized attachments appear to be less effective for vertical movements of premolars [

36]. In the university setting, beginners were particularly attentive to this aspect and planned a more gradual staging of premolar movements, which aligns with our results. Specifically, they prioritized tipping movements rather than attempting to control multiple movement types simultaneously within a single aligner sequence.

Discrepancies between planned and achieved tooth movements may contribute to prolonged treatment duration in clear aligner therapy. A notable example is the control of vertical movements in upper incisors. While Yan et al. demonstrated that clear aligner therapy can achieve partial incisor proclination (69.8%) and intrusion (53.3%) [

40], a recent systematic review suggests that poor vertical control reported in some clinical studies may be attributed to the bite-block effect [

41].

This effect may help explain the longer treatment duration observed in the beginner group. While limited clinical experience in managing treatment contingencies may have contributed to this prolonged duration, the literature suggests that longer treatment times in orthodontic students are also influenced by the academic training environment, where case progression is subject to supervision and structured learning processes [

41].

Experienced orthodontists, with years of clinical practice using clear aligner treatments, are more aware of the limitations of the technique and apply strategic sequencing and staging in their treatment planning, leading to greater predictability and reduced treatment duration compared to beginners.

While this finding may appear self-evident, it underscores a critical educational gap. A short certification course is insufficient to equip clinicians with the comprehensive knowledge and skills required to effectively manage clear aligner treatments. This is particularly relevant for orthodontic residents, who need a structured educational framework that includes specific training on clear aligner therapy, supervised by experienced orthodontists [

18].

Within the limits of this retrospective study, the findings suggest that operator experience has a measurable yet clinically modest impact on the predictability of difficult tooth movements with clear aligners. These findings align with previous investigations reporting that treatment outcomes depend more on case selection, staging strategy, and patient compliance than on operator seniority alone.

Because all participants were treated within a single digital workflow and under standardized supervision, the results can be reasonably generalized to similar clinical settings where aligner therapy follows comparable protocols. However, caution should be exercised when extrapolating these findings to different systems, software platforms, or patient populations. Within these constraints, the present findings help clarify the relative contribution of operator experience to movement predictability and may guide clinicians toward more conservative and biomechanically sound planning strategies.

Moreover, the aggressive marketing strategies encouraging general dentists to offer clear aligner treatments may lead to longer treatment durations, an increased number of aligners required, and suboptimal esthetic and functional outcomes. This raises concerns regarding the definition of orthodontic treatment quality and highlights the need for rigorous training before practitioners incorporate clear aligner treatments into their clinical practice.

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings of this study. First, the analysis was conducted on STL dental models, which do not contain stable skeletal reference structures such as cranial bases. Although cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) could enhance superimposition accuracy, its routine application in this context would lead to unwarranted radiation exposure, making it an impractical solution given current technological and ethical considerations [

42]. Consequently, the superimposition procedure relied on validated dental-based protocols combining landmark registration and surface best-fit alignment. While appropriate for intraoral scans, this approach may limit absolute three-dimensional accuracy.

Second, the retrospective design may have introduced residual selection or confounding bias despite matching for treatment difficulty. The ICON-derived difficulty score ensured comparable baseline complexity, yet it may not fully capture subtle morphological or biomechanical characteristics—such as arch form, crown shape, or anchorage demands—that could influence movement predictability and could not be quantified retrospectively.

Third, multiple comparisons across tooth types and movement categories were performed without formal adjustment for multiplicity, increasing the potential risk of Type I error. Moreover, because several teeth from each patient were analyzed, intra-subject correlations could not be fully addressed with the non-parametric tests employed. Future studies with larger samples should apply mixed-effects models to account for operator- and patient-level clustering.

Fourth, inter-operator variability within each experience group was not statistically adjusted. The study compared experience levels rather than individual clinicians, and the limited number of operators did not allow modeling operator-specific random effects.

Fifth, although all outcome measurements were obtained using standardized digital procedures on anonymized STL models, thereby minimizing subjective bias, the assessor was not blinded during the virtual setup review, which may represent another minor source of bias.

Finally, only the first treatment phase was evaluated, and long-term stability or relapse data were not available. Therefore, the results reflect the accuracy of movement expression during active treatment only. Prospective longitudinal studies are needed to assess post-treatment stability and its potential relationship with operator experience.

5. Conclusions

This study provides insight into how operator experience influences the predictability and efficiency of clear aligner therapy. Although several differences between beginners and experienced orthodontists reached statistical significance, most remained below predefined thresholds for clinical relevance (0.5 mm and 2°).

These findings underscore the importance of precise digital measurements for evaluating the expression of planned movements, particularly rotations and vertical displacements, which confirmed to be the least predictable categories regardless of operator experience.

Notably, the teeth exhibiting the lowest predictability in this cohort were those required to perform complex rotational or vertical movements. From a clinical perspective, the concomitant planning of multiple demanding movements on these teeth may further compromise predictability—an interpretation consistent with our current biomechanical understanding, although not directly tested in the present study.

Future studies should investigate optimized staging strategies and refine digital planning protocols to improve the expression of challenging movements and reduce operator-dependent variability.