Pneumatic Robot for Finger Rehabilitation After Stroke: A Pilot Validation on Short-Term Effectiveness Depending on FMA Score

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Environment

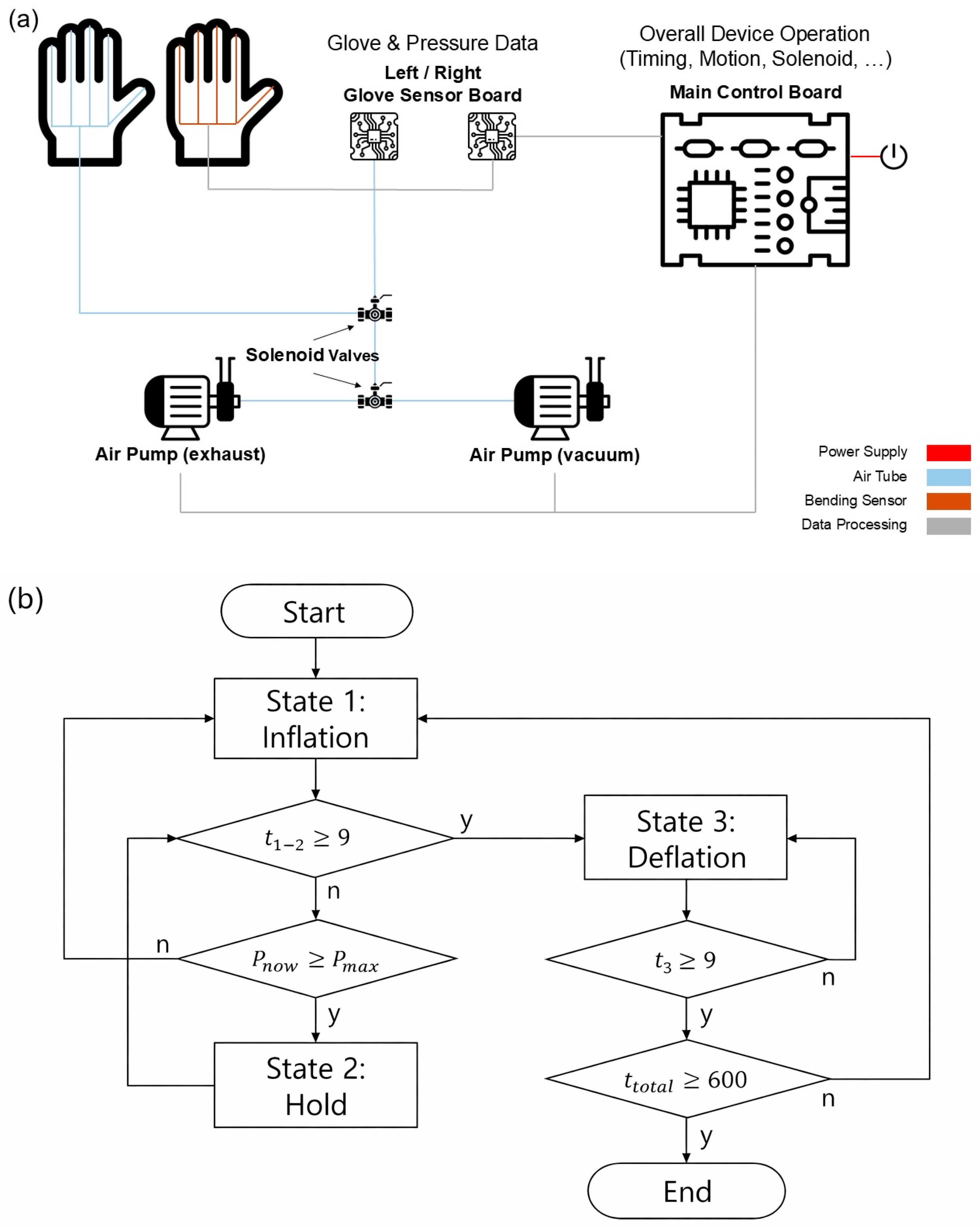

2.2. System Overview

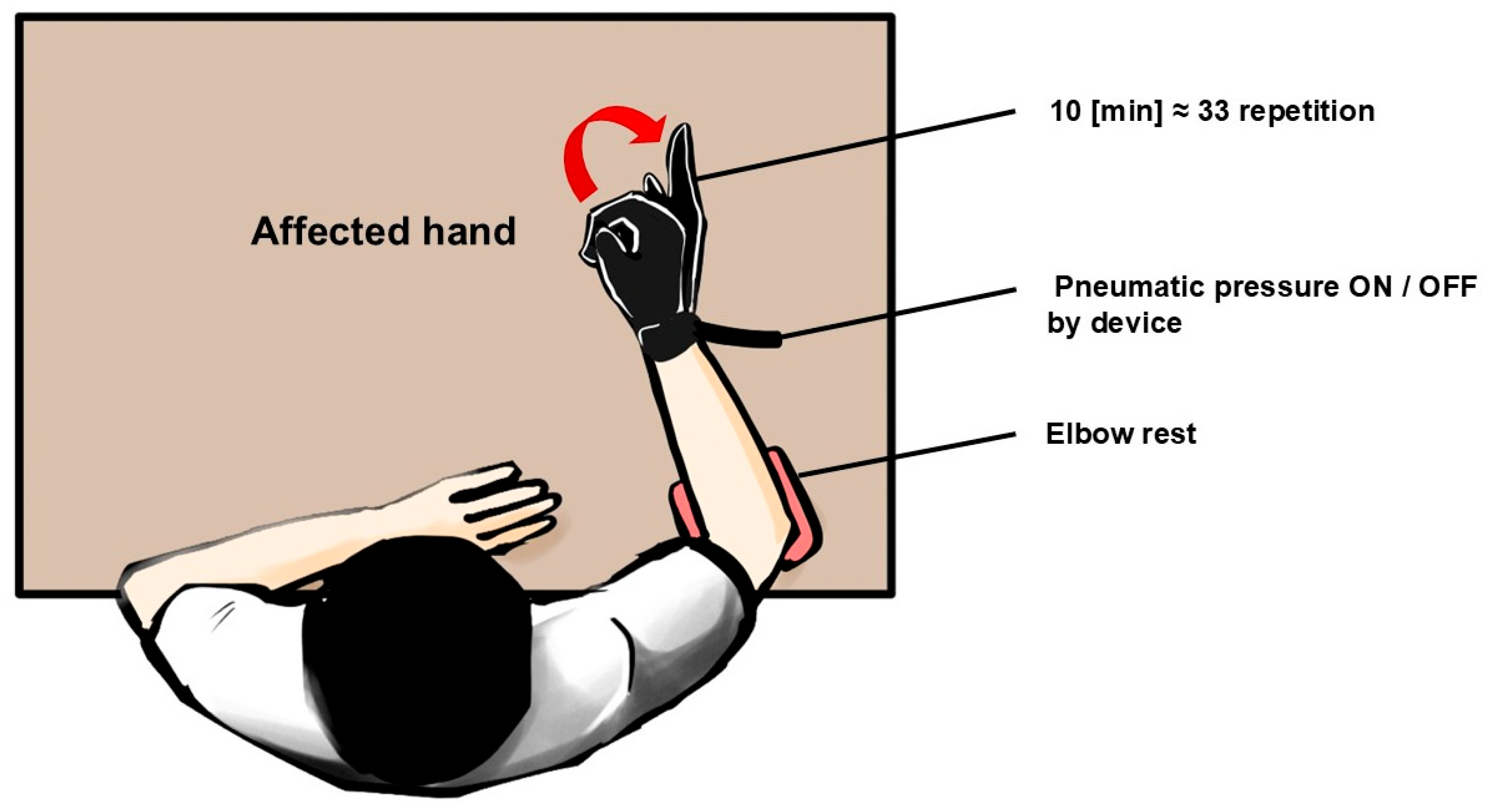

2.3. Experimental Protocol

2.4. Outcome Measures

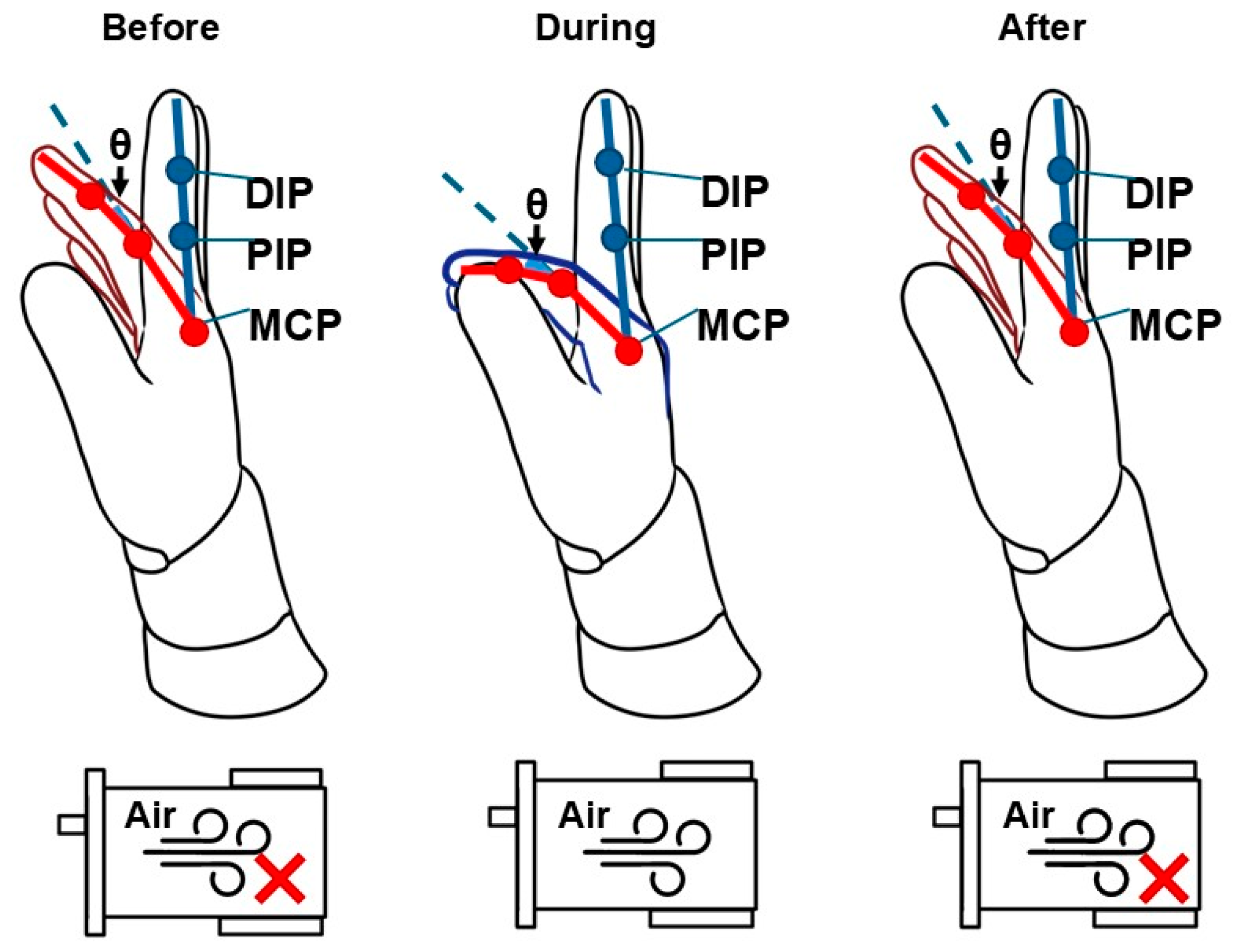

2.4.1. Range of Motion

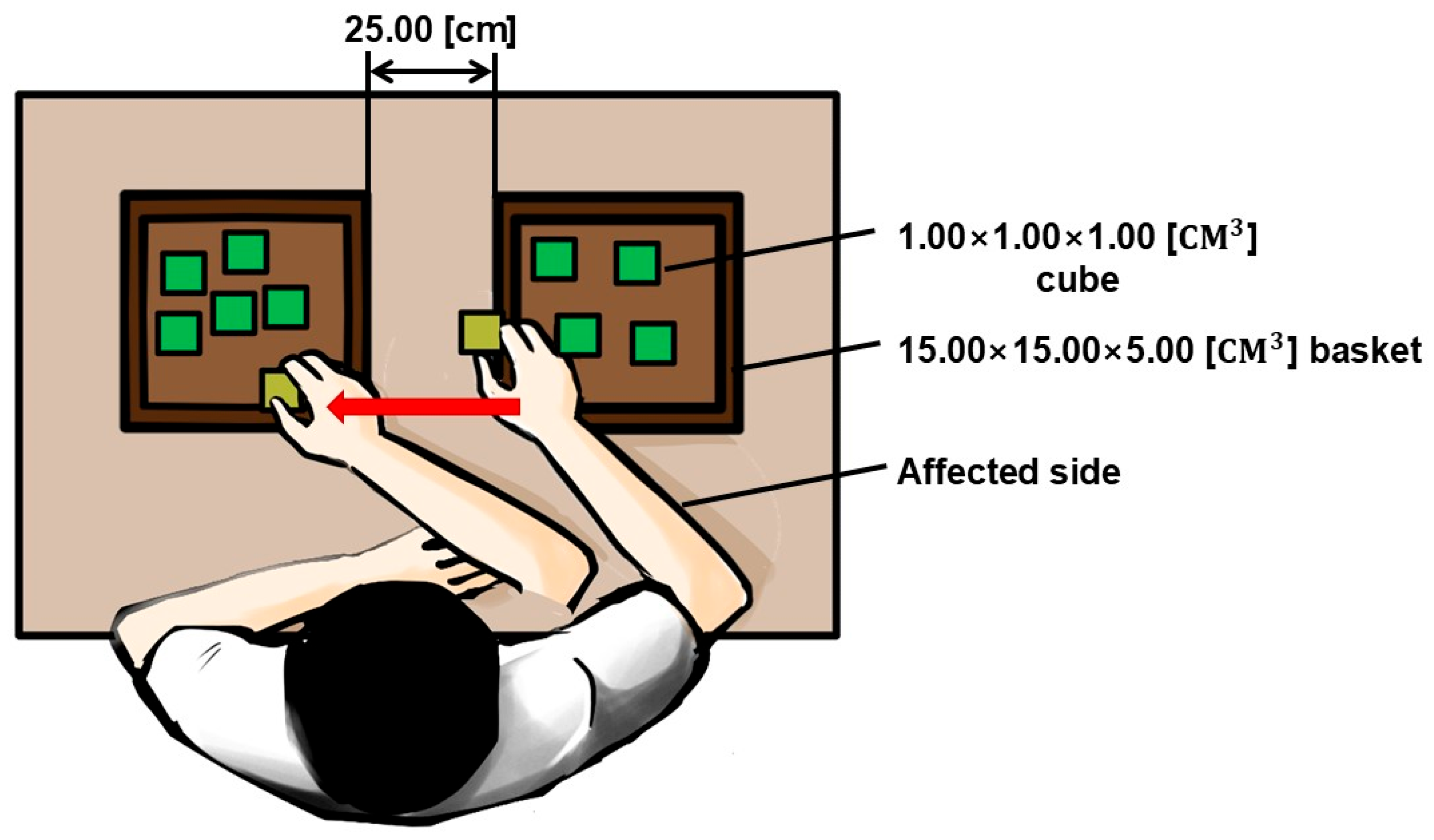

2.4.2. Functional Task

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

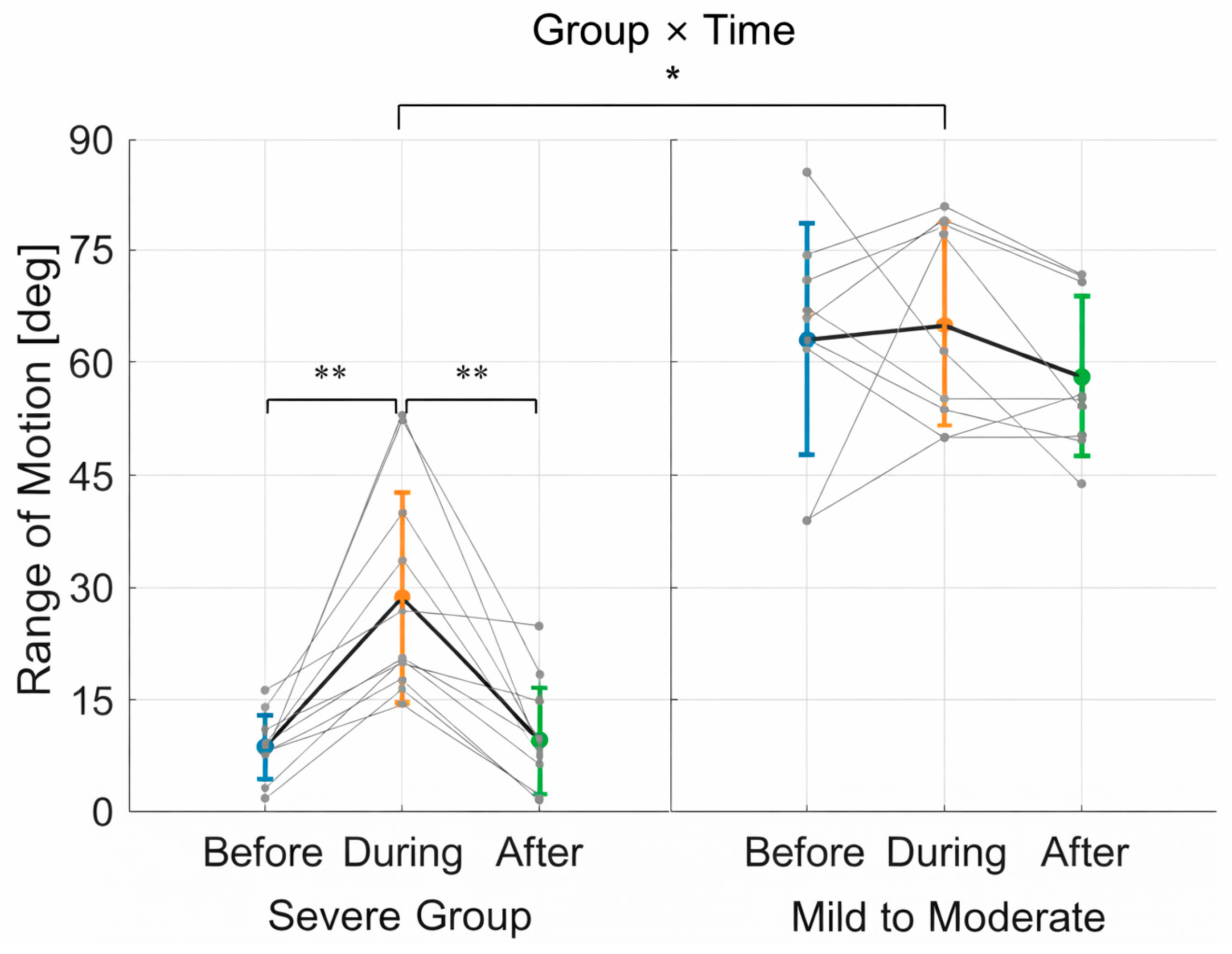

3.1. Range of Motion (ROM)

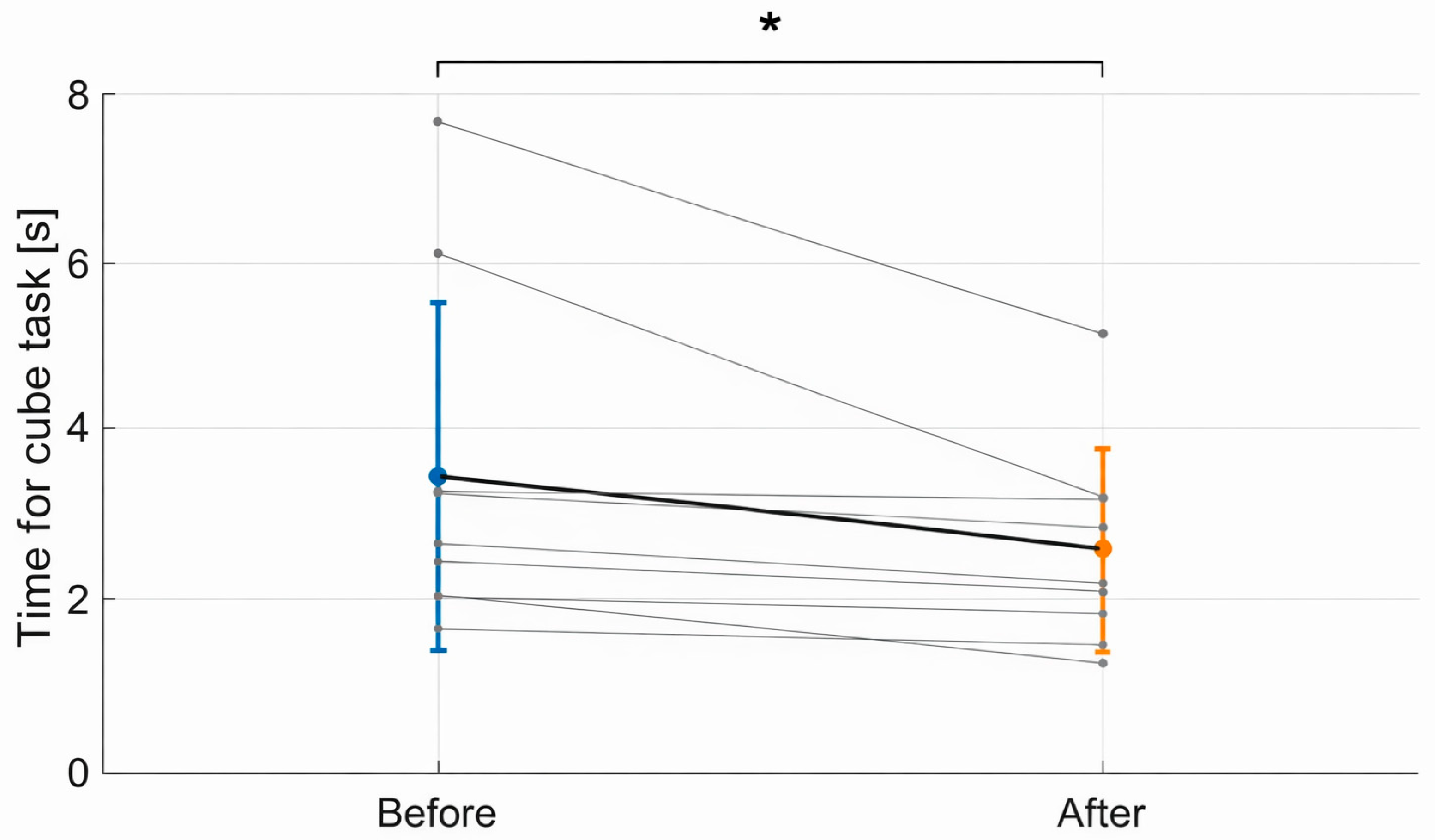

3.2. Functional Task Performance

3.3. Summary of Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ROM | Range of Motion |

| FMA | Fugl-Meyer Assessment |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| sEMG | Surface Electromyography |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance SD |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

References

- Feigin, V.L.; Norrving, B.; Mensah, G.A. Global Burden of Stroke. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.E.; Bland, M.D.; Bailey, R.R.; Schaefer, S.Y.; Birkenmeier, R.L. Assessment of upper extremity impairment, function, and activity after stroke: Foundations for the clinical decision making process. J. Hand Ther. 2013, 26, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwakkel, G.; van Peppen, R.; Wagenaar, R.C.; Wood Dauphinee, S.; Richards, C.; Ashburn, A.; Miller, K.; Lincoln, N.; Partridge, C.; Wellwood, I.; et al. Effects of augmented exercise therapy time after stroke: A meta-analysis. Stroke 2004, 35, 2529–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohse, K.R.; Lang, C.E.; Boyd, L.A. Is more better? Using metadata to explore dose-response relationships in stroke rehabilitation. Stroke 2014, 45, 2053–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winstein, C.J.; Stein, J.; Arena, R.; Bates, B.; Cherney, L.R.; Cramer, S.C.; Deruyter, F.; Eng, J.J.; Fisher, B.; Harvey, R.L.; et al. Guidelines for Adult Stroke Rehabilitation and Recovery: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2016, 47, e98–e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejasz, P.; Eschweiler, J.; Gerlach-Hahn, K.; Jansen-Troy, A.; Leonhardt, S. A survey on robotic devices for upper limb rehabilitation. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2014, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrholz, J.; Pohl, M.; Platz, T.; Kugler, J.; Elsner, B. Electromechanical and robot-assisted arm training for improving activities of daily living, arm function, and arm muscle strength after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 9, CD006876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, P.; Morone, G.; Rossetti, G.; Masiero, S. Robotic technologies and rehabilitation: New tools for stroke patients’ recovery. Biomed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 152578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selomah, M.S.; Nasir, N.M.; Jalani, J.; Rahman, H.A.; Huq, S. The Role of Bio-Inspired Soft Robotic Gloves in Stroke Rehabilitation: A Comprehensive Analytical Review. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 64, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiska, V.; Mitsopoulos, K.; Mantiou, V.; Petronikolou, V.; Antoniou, P.; Tagaras, K.; Kasimis, K.; Nizamis, K.; Tsipouras, M.G.; Astaras, A.; et al. Integration and Validation of Soft Wearable Robotic Gloves for Sensorimotor Rehabilitation of Human Hand Function. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polygerinos, P.; Wang, Z.; Galloway, K.C.; Wood, R.J.; Walsh, C.J. Soft robotic glove for combined assistance and at-home rehabilitation. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2015, 73, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, H.K.; Lim, J.H.; Nasrallah, F.; Goh, J.C.H.; Yeow, C.H. A soft exoskeleton for hand assistive and rehabilitation application using pneumatic actuators with variable stiffness. In 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 4967–4972. [Google Scholar]

- Rus, D.; Tolley, M.T. Design, fabrication and control of soft robots. Nature 2015, 521, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianchetti, M.; Laschi, C.; Menciassi, A.; Dario, P. Biomedical applications of soft robotics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.Y.; Patterson, R.M. Soft robotic devices for hand rehabilitation and assistance: A narrative review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2018, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heung, H.L.; Tong, R.K.Y.; Lau, A.T.S.; Li, Z. Robotic Glove with Soft-Elastic Composite Actuators for Assistive and Rehabilitation Applications. Soft Robot. 2019, 6, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In, H.; Kang, B.B.; Sin, M.; Cho, K.J. Exo-Glove: A Wearable Robot for the Hand with a Soft Tendon Routing System. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2011, 18, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radder, B.; Prange-Lassen, G.; Kottink, A.; Holmberg, J.; Sivan, M.; Nardeo, O.; Kenney, L.; Rietman, J. Feasibility of a wearable soft-robotic glove to support impaired hand function in stroke patients. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2019, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.B.; Choi, H.; Lee, K.H.; Rogers-Craig, S.; Cho, K.J. Exo-Glove Poly: A Polymer-Based Soft Wearable Robot for the Hand with a Tendon-Driven Actuation System. Soft Robot. 2016, 3, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, L.; Meyer, J.T.; Galloway, K.C.; Peisner, J.D.; Granberry, R.; Wagner, D.A.; Engelhardt, S.; Paganoni, S.; Walsh, C.J. Assisting hand function after spinal cord injury with a soft robotic glove. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2018, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, H.C.; Stubblefield, K.; Kline, T.; Luo, X.; Kenyon, R.V.; Kamper, D.G. Hand rehabilitation following stroke: A pilot study of assisted finger extension training in a virtual environment. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2007, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerez, L.; Chen, J.; Liarokapis, M. On the development of adaptive, tendon-driven, soft robotic grippers for investigating grasp capabilities. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 6015–6022. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamaddan, S.; Komeda, T. Wire-driven mechanism for finger rehabilitation device. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2010, 7, 347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Thibaut, A.; Chatelle, C.; Ziegler, E.; Bruno, M.A.; Schnakers, C.; Laureys, S. Spasticity after stroke: Physiology, assessment and treatment. Brain Inj. 2013, 27, 1093–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherson, J.G.; Laney, J.P. Evidence for a ceiling effect in the responsiveness of the Action Research Arm Test. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2016, 30, 603–604. [Google Scholar]

- Fugl-Meyer, A.R.; Jääskö, L.; Leyman, I.; Olsson, S.; Steglind, S. The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. A method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 1975, 7, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathiowetz, V.; Volland, G.; Kashman, N.; Weber, K. Adult norms for the Box and Block Test of manual dexterity. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1985, 39, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinear, C.M.; Byblow, W.D. Rhythmic Neuromodulation Improves Motor Processing following Stroke. Trans. Stroke Res. 2020, 11, 600–601. [Google Scholar]

- Gassert, R.; Dietz, V. Rehabilitation robots for the treatment of sensorimotor deficits: A neurophysiological perspective. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2018, 15, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rierola-Fochs, A.; Valls-Solé, J. Sensory inputs and motor preparation. Neurosci. Lett. 2020, 716, 134683. [Google Scholar]

- Cirstea, M.C.; Levin, M.F. Compensatory strategies for reaching in stroke. Brain 2000, 123, 940–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, L.M.; Stein, J. The use of robots in stroke rehabilitation: A narrative review. NeuroRehabilitation 2018, 43, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogk, J.P.; Keir, P.J. Crosstalk in surface electromyography of the forearm finger extensors. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2003, 13, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.K.; Lowe, B.D.; Lee, S.J.; Krieg, E.F. Evaluation of handle design characteristics in a ham-boning knife using EMG evaluation of the forearm flexors and extensors. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2010, 40, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dewald, J.P.A.; Pope, P.S.; Given, J.D.; Buchanan, T.S.; Rymer, W.Z. Abnormal muscle coactivation patterns during isometric torque generation at the elbow and shoulder in hemiparetic subjects. Brain 1995, 118, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Sex | FMA-UE | FMA-Hand | Affected Side |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 6 | 0 | R |

| 2 | M | 12 | 0 | R |

| 3 | M | 12 | 2 | R |

| 4 | M | 12 | 0 | R |

| 5 | F | 16 | 4 | R |

| 6 | M | 12 | 0 | R |

| 7 | M | 20 | 2 | R |

| 8 | M | 7 | 0 | R |

| 9 | M | 53 | 5 | R |

| 10 | F | 36 | 0 | L |

| 11 | F | 9 | 0 | L |

| 12 | F | 57 | 13 | R |

| 13 | M | 62 | 14 | R |

| 14 | M | 53 | 10 | R |

| 15 | F | 66 | 14 | R |

| 16 | M | 66 | 14 | R |

| 17 | M | 66 | 14 | L |

| 18 | F | 53 | 10 | L |

| 19 | M | 57 | 14 | L |

| 20 | F | 53 | 12 | L |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kang, J.; Seo, S.; Jang, H.; Kim, J. Pneumatic Robot for Finger Rehabilitation After Stroke: A Pilot Validation on Short-Term Effectiveness Depending on FMA Score. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 993. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020993

Kang J, Seo S, Jang H, Kim J. Pneumatic Robot for Finger Rehabilitation After Stroke: A Pilot Validation on Short-Term Effectiveness Depending on FMA Score. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):993. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020993

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Jewheon, Sion Seo, Hojin Jang, and Jaehyo Kim. 2026. "Pneumatic Robot for Finger Rehabilitation After Stroke: A Pilot Validation on Short-Term Effectiveness Depending on FMA Score" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 993. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020993

APA StyleKang, J., Seo, S., Jang, H., & Kim, J. (2026). Pneumatic Robot for Finger Rehabilitation After Stroke: A Pilot Validation on Short-Term Effectiveness Depending on FMA Score. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 993. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020993