Cybersecurity and Resilience of Smart Grids: A Review of Threat Landscape, Incidents, and Emerging Solutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

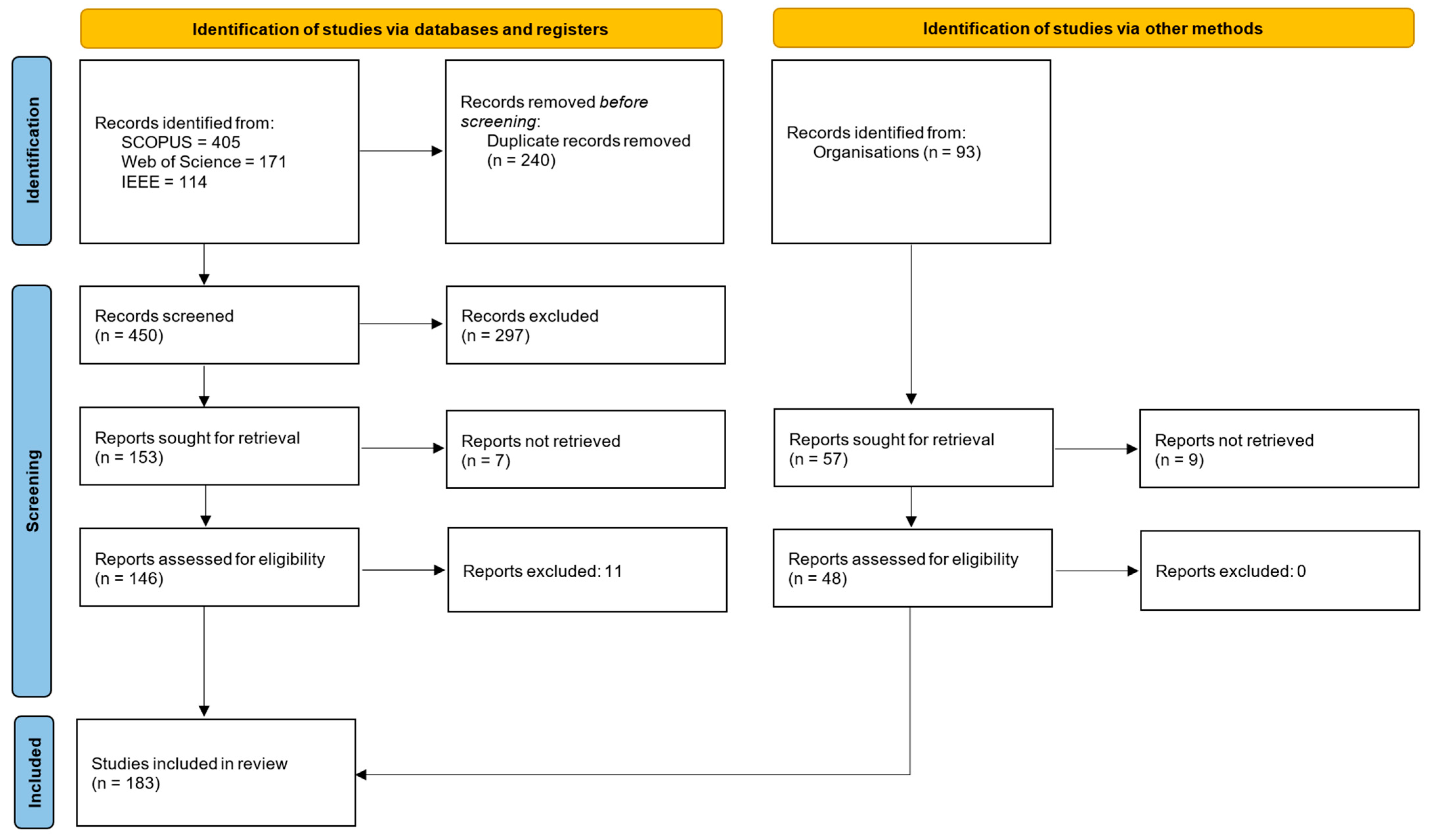

2. Methodology

- Identify and classify cybersecurity threats and attack vectors relevant to smart grids across architectural layers, components, and interfaces.

- Map documented cyber incidents affecting energy infrastructures to threat categories and impacted smart grid functions.

- Synthesise technical and organisational approaches proposed to improve prevention, detection, response, and recovery in smart grid environments.

- Identify research gaps and future directions for improving cybersecurity and resilience in smart grids.

- Based on these objectives, the review addresses the following questions:

- Which threat categories and attack vectors are reported in relation to smart grids and closely related electricity system infrastructures?

- Which architectural components and communication interfaces are most frequently targeted or exposed?

- Which real-world cyber incidents have affected energy infrastructures relevant to smart grids, and how do these incidents map to threat categories and impacted components?

- Which approaches are proposed in the literature to enhance cybersecurity and resilience, and where gaps remain?

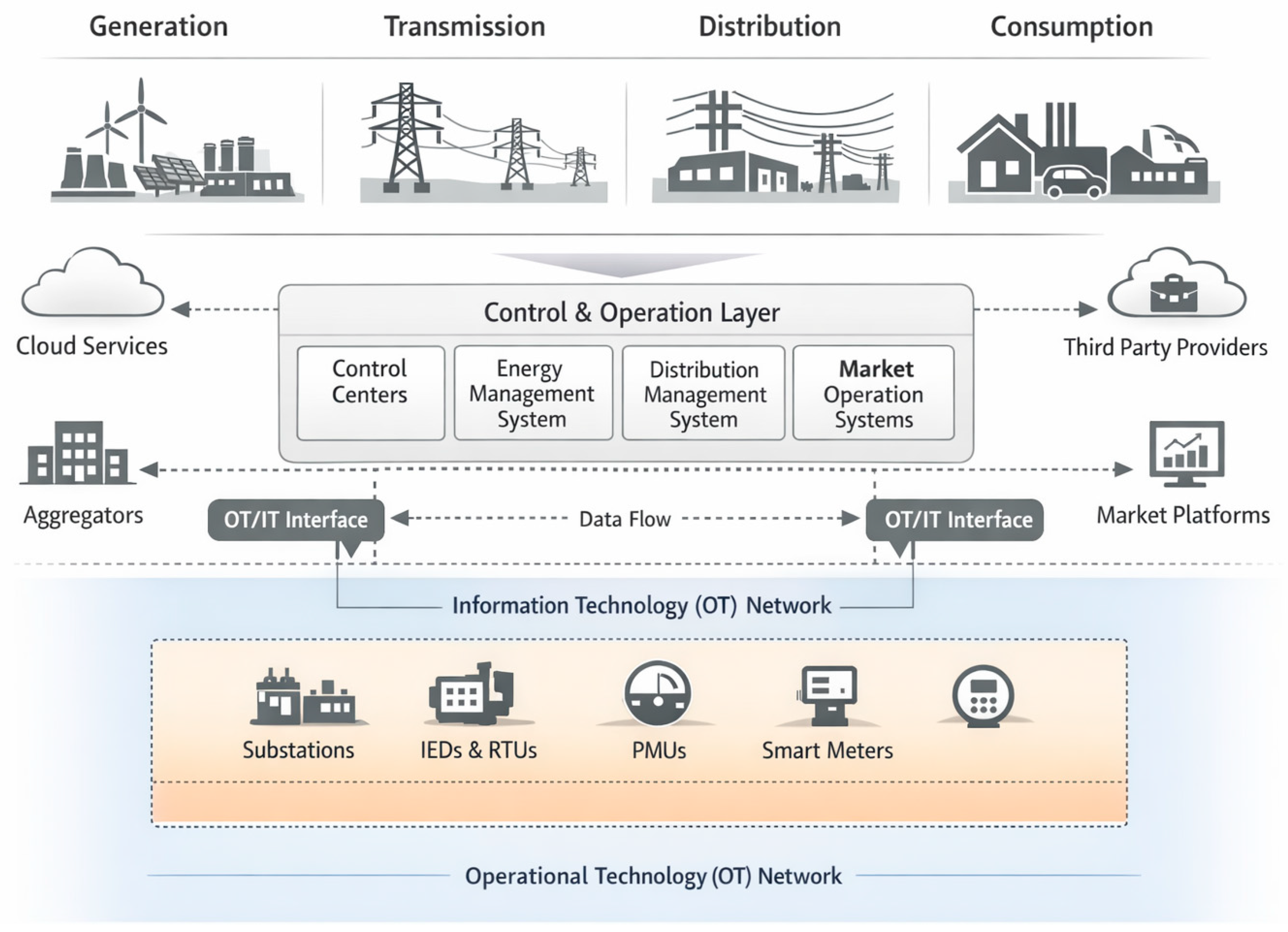

3. Smart Grid Architecture and Key Components

4. Security Challenges in Smart Grids

4.1. Attack Surface Expansion and System Interconnectivity

4.2. Information Technology Platforms, Cloud Dependence, and Data Handling

4.3. Legacy Control Systems, Protocols, and Operational Technology

4.4. Software Supply Chains and Update Mechanisms

4.5. Operational Constraints and Cyber–Physical Safety Implications

4.6. Cross-Infrastructure Coupling, Organisational, Human, and Regulatory Challenges

4.7. Mapping Security Challenges to Smart Grid Architecture and Interfaces

5. Major Cyberthreats and Cyberattack Vectors in Smart Grids

5.1. Malware, Ransomware, and Destructive Attacks

5.2. Network-, Protocol-, and Communication-Based Attacks

5.3. Software, Firmware, and Supply Chain Vulnerabilities

5.4. Human, Organisational, and Insider Related Threats

5.5. Systemic and Emerging Threat Trends

5.6. Mapping Cyber Threats to Smart Grid Layers and Impacts

6. Notable Cyberattack Incidents in Energy Infrastructure

6.1. Incident Selection and Evidence Sources

6.2. Major Documented Cyber Incidents in Power Systems

6.2.1. 1982—Siberian Gas Pipeline Explosion

6.2.2. 2003—Davis–Besse Nuclear Plant Incident

6.2.3. 2009—Night Dragon Energy Sector Espionage

6.2.4. 2010—Stuxnet Cyber-Physical Sabotage

6.2.5. 2011—Dragonfly Energetic Bear Campaigns

6.2.6. 2012—Shamoon Destructive Malware Attacks

6.2.7. 2015—Ukraine Power Grid Cyberattacks

6.2.8. 2016—Ukraine Industroyer Attack

6.2.9. 2017—Triton Trisis Safety System Compromise

6.2.10. 2019—EKANS OT-Aware Ransomware

6.2.11. 2021—Colonial Pipeline Ransomware Incident

6.2.12. 2022—Viasat Satellite Communications Disruption

6.2.13. 2022—Industroyer2 Attempted Grid Disruption

6.2.14. 2023—State Linked Prepositioning in Energy and Utility Networks (Volt Typhoon)

6.2.15. 2023—Ransomware Attack on Holding Slovenske Elektrarne

6.2.16. 2024—Continued Cyber Operations Targeting Ukrainian Energy Infrastructure

6.2.17. 2025—Iran Reports Repelling a Large-Scale Cyberattack Against National Infrastructure

6.3. Cross Incident Analysis of Attack Vectors and Impacts

6.4. Lessons Learned and Implications for Grid Resilience

7. Emerging Solutions and Future Directions for Grid Cybersecurity

7.1. AI-Driven Monitoring and Anomaly Detection

7.2. Zero-Trust Architectures and Identity-Centric Security

7.3. Blockchain and Distributed Trust Mechanisms

7.4. Advanced Cryptography and Post Quantum Security

7.5. Digital Twins for Cyber Physical Resilience and Recovery

7.6. Cyber Resilient Grid Design and Operational Preparedness

7.7. Policy, Standards, and Governance Considerations

7.8. Summary and Mapping to Historical Incidents

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AES | Advanced Encryption Standard |

| AMI | Advanced Metering Infrastructure |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| CIA | Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| DER | Distributed Energy Resource |

| DDoS | Distributed Denial of Service |

| DoS | Denial of Service |

| EMS | Energy Management System |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| FDIA | False Data Injection Attack |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| ICS | Industrial Control System |

| IEC | International Electrotechnical Commission |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IP | Internet Protocol |

| IT | Information Technology |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NERC | North American Electric Reliability Corporation |

| NIS | Network and Information Security |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| OT | Operational Technology |

| PLC | Programmable Logic Controller |

| PMU | Phasor Measurement Unit |

| RTU | Remote Terminal Unit |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| SQL | Structured Query Language |

| TLS | Transport Layer Security |

| VPN | Virtual Private Network |

References

- Fang, X.; Misra, S.; Xue, G.; Yang, D. Smart Grid—The New and Improved Power Grid: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2012, 14, 944–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, T.; Ernst, R.; Klaer, B.; Hacker, I.; Henze, M. Cybersecurity in Power Grids: Challenges and Opportunities. Sensors 2021, 21, 6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Smart Grid Interoperability Panel–Smart Grid Cybersecurity Committee. Guidelines for Smart Grid Cybersecurity (NIST IR 7628 Rev. 1). Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/ir/7628/r1/final (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Sun, C.-C.; Hahn, A.; Liu, C.-C. Cyber security of a power grid: State-of-the-art. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 99, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. Russian Government Cyber Activity Targeting Energy and Other Critical Infrastructure Sectors (TA18-074A). Available online: https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/alerts/2018/03/15/russian-government-cyber-activity-targeting-energy-and-other-critical-infrastructure-sectors (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- European Union Agency for Cybersecurity. ENISA Threat Landscape 2025; ENISA Reports; ENISA: Athens, Greece, 2025; Available online: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/enisa-threat-landscape-2025 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Alomari, M.A.; Al-Andoli, M.N.; Ghaleb, M.; Thabit, R.; Alkawsi, G.; Alsayaydeh, J.A.J.; Gaid, A.S.A. Security of Smart Grid: Cybersecurity Issues, Potential Cyberattacks, Major Incidents, and Future Directions. Energies 2025, 18, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, A.R. Safeguarding the energy transition: A review of cybersecurity strategies for vulnerability management in smart grids. Energy Convers. Manag.-X 2026, 29, 101419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achaal, B.; Adda, M.; Berger, M.; Ibrahim, H.; Awde, A. Study of smart grid cyber-security, examining architectures, communication networks, cyber-attacks, countermeasure techniques, and challenges. Cybersecurity 2024, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulsen, K. Slammer Worm Crashed Ohio Nuke Plant Net. Available online: https://www.theregister.com/2003/08/20/slammer_worm_crashed_ohio_nuke/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- International Energy Agency. Enhancing Cyber Resilience in Electricity Systems; IEA: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2021/04/enhancing-cyber-resilience-in-electricity-systems_38dbad0f/e00ae407-en.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Langer, L.; Skopik, F.; Smith, P.; Kammerstetter, M. From old to new: Assessing cybersecurity risks for an evolving smart grid. Comput. Secur. 2016, 62, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, S.; Amissah, J.; Kinga, S.; Mugerwa, G.; Emmanuel, E.; Mansour, D.-E.A.; Bajaj, M.; Blazek, V.; Prokop, L. Securing modern power systems: Implementing comprehensive strategies to enhance resilience and reliability against cyber-attacks. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toftegaard, O.; Grotterud, G.; Hammerli, B. Operational Technology resilience in the 2023 draft delegated act on cybersecurity for the power sector-An EU policy process analysis. Comput. LAW Secur. Rev. 2024, 54, 106034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteli, M.; Mancarella, P.; Trakas, D.N.; Kyriakides, E.; Hatziargyriou, N.D. Metrics and Quantification of Operational and Infrastructure Resilience in Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 32, 4732–4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Chen, X.; Li, Q. Evolution of smart grid cybersecurity: Toward a systematic framework for collaborative and sustainable development. Util. Policy 2025, 97, 102081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopstein, A.; Nguyen, C.; O’Fallon, C.; Hastings, N.; Wollman, D.A. NIST Framework and Roadmap for Smart Grid Interoperability Standards, Release 4.0; National Institute of Standards Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2021. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.1108r4.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Kabalci, E.; Kabalci, Y. Introduction to Smart Grid Architecture. In Smart Grids and Their Communication Systems; Kabalci, E., Kabalci, Y., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 3–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajwal Gupta, C.R.; Ramesh, A.; Satvik, D.; Nagasundari, S.; Honnavalli, P.B. Simulation of SCADA System for Advanced Metering Infrastructure in Smart Grid. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Smart Electronics and Communication (ICOSEC), Trichy, India, 10–12 September 2020; pp. 1071–1077. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9215432 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Wali, A.; Alshehry, F. A Survey of Security Challenges in Cloud-Based SCADA Systems. Computers 2024, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed Mohassel, R.; Fung, A.; Mohammadi, F.; Raahemifar, K. A survey on Advanced Metering Infrastructure. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2014, 63, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siano, P. Demand response and smart grids—A survey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 30, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Lin, Y.; Bai, G.; Paverd, A.; Dong, J.S.; Martin, A. Smart Grid Metering Networks: A Survey on Security, Privacy and Open Research Issues. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2886–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, E.; Richardson, I.; Thomson, M. Smart meter data: Balancing consumer privacy concerns with legitimate applications. Energy Policy 2012, 41, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, T. Preserving Privacy: How Do You Protect Smart Meter Data? Available online: https://www.theredfoundation.org/post/preserving-privacy-how-do-you-protect-smart-meter-data (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Alanazi, F.; Kim, J.; Cotilla-Sanchez, E. Load Oscillating Attacks of Smart Grids: Vulnerability Analysis. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 36538–36549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokry, M.; Awad, A.I.; Abd-Ellah, M.K.; Khalaf, A.A.M. Systematic survey of advanced metering infrastructure security: Vulnerabilities, attacks, countermeasures, and future vision. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 136, 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Kaur, K.; Kaddoum, G.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C.; Guizani, M. Secure and Lightweight Authentication Scheme for Smart Metering Infrastructure in Smart Grid. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 3548–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Hong, Y. Security Challenges in Smart Grid Implementation. In Smart Grid Security; Springer: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, P.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Pan, L. Puppet attack: A denial of service attack in advanced metering infrastructure network. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2016, 59, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokar, P.; Arianpoo, N.; Leung, V.C.M. Spoofing detection in IEEE 802.15.4 networks based on received signal strength. Ad Hoc Netw. 2013, 11, 2648–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Yin, X.; Tan, Y.; Li, C.; Gao, Y.; Cao, Y.; Li, J. The contributions of cloud technologies to smart grid. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 59, 1326–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathor, S.K.; Saxena, D. Energy management system for smart grid: An overview and key issues. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 4067–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wu, J.; Zheng, X.; Li, J.; Yang, W.; Vasilakos, A.V. Cloud-Edge Orchestrated Power Dispatching for Smart Grid With Distributed Energy Resources. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2023, 11, 1194–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, A.F.; Mokhlis, H.; Mansor, N.N.; Jamian, J.J.; Wang, L.; Muhammad, M.A. Power Distribution System Outage Management Using Improved Resilience Metrics for Smart Grid Applications. Energies 2023, 16, 3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.M.; Maharjan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Eliassen, F.; Strunz, K. Optimal Energy Trading With Demand Responses in Cloud Computing Enabled Virtual Power Plant in Smart Grids. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2022, 10, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std 2030.5-2018; IEEE Standard for Smart Energy Profile Application Protocol; Revision of IEEE Std 2030.5-2013. IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–361. [CrossRef]

- SunSpec Alliance. SunSpec Modbus Information Models. Available online: https://sunspec.org/modbus/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Tsikteris, S.; Diamantopoulos Pantaleon, O.; Tsiropoulou, E.E. Cybersecurity Certification Requirements for Distributed Energy Resources: A Survey of SunSpec Alliance Standards. Energies 2024, 17, 5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ning, P.; Reiter, M.K. False data injection attacks against state estimation in electric power grids. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur. 2011, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Qian, Y.; Sharif, H.; Tipper, D. A Survey on Cyber Security for Smart Grid Communications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2012, 14, 998–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, T.; Bompard, E.F. Big data analytics in smart grids: A review. Energy Inform. 2018, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantoulakis, P.D.; Kapinas, V.M.; Karagiannidis, G.K. Big Data Analytics for Dynamic Energy Management in Smart Grids. Big Data Res. 2015, 2, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawoosa, A.I.; Prashar, D. A Review of Cyber Securities in Smart Grid Technology. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Computation, Automation and Knowledge Management (ICCAKM), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 21–19 January 2021; pp. 151–156. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9357698/ (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Yilmaz, S.; Dener, M. Security with Wireless Sensor Networks in Smart Grids: A Review. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diovu, R.C.; Agee, J.T. Smart grid advanced metering infrastructure: Overview of cloud-based cyber security solutions. Int. J. Commun. Antenna Propag. 2018, 8, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douae, T.; Hassan, B. Sensitive Infrastructure Control Systems Cyber-Security: Literature Review. In International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems for Sustainable Development. AI2SD 2022; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 712, pp. 310–319. [Google Scholar]

- Skrodelis, H.; Kelle, R.; Romanovs, A. Cybersecurity in SCADA Systems with Advanced AI and ML Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 65th International Scientific Conference on Information Technology and Management Science of Riga Technical University (ITMS), Riga, Latvia, 3–4 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banad, Y.M.; Sharif, S.S.; Rezaei, Z. Artificial intelligence and machine learning for smart grids: From foundational paradigms to emerging technologies with digital twin and large language model-driven intelligence. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 28, 101329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noura, H.N.; Yaacoub, J.P.A.; Salman, O.; Chehab, A. Advanced Machine Learning in Smart Grids: An overview. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2025, 5, 95–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, B.N.; Gunasekaran, S.S.; Ma, Z.G. Impact of EU Laws on AI Adoption in Smart Grids: A Review of Regulatory Barriers, Technological Challenges, and Stakeholder Benefits. Energies 2025, 18, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, L.; Feng, H.; Wu, X.; Li, R. Survey of privacy-preserving data aggregation schemes in smart grid. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2025, 37, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std 1815-2012; IEEE Standard for Electric Power Systems Communications—Distributed Network Protocol (DNP3). IEEE Power Energy Society: New York, NY, USA, 2018. Available online: https://standards.ieee.org/ieee/1815/5414/ (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- IEC 60870-5-104:2006; Telecontrol Equipment and Systems—Part 5-104: Transmission Protocols—Network Access for IEC 60870-5-101 Using Standard Transport Profiles. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. Available online: https://webstore.iec.ch/publication/25035 (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Modbus Organization. Modbus Application Protocol Specification V1.1b3; Modbus Organization: Hopkinton, MA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20201209184336/http://www.modbus.org/docs/Modbus_Application_Protocol_V1_1b3.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Ayele, E.D.; Gonzalez, J.F.; Teeuw, W.B. Enhancing Cybersecurity in Distributed Microgrids: A Review of Communication Protocols and Standards. Sensors 2024, 24, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, A.A.; Alheeti, K.M.A. A Review Paper: Security for Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition SCADA Based on DNP3. In Proceedings of the 2023 16th International Conference on Developments in eSystems Engineering (DeSE), Istanbul, Turkiye, 18–20 December 2023; pp. 800–805. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/record/display.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85189358770&origin=inward (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Kuzlu, M.; Pipattanasompom, M.; Rahman, S. A comprehensive review of smart grid related standards and protocols. In Proceedings of the 2017 5th International Istanbul Smart Grid and Cities Congress and Fair (ICSG), Istanbul, Turkey, 19–21 April 2017; pp. 12–16. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7947600/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Ishfaq, H.; Kanwal, S.; Anwar, S.; Abdussalam, M.; Amin, W. Enhancing Smart Grid Security and Efficiency: AI, Energy Routing, and T&D Innovations (A Review). Energies 2025, 18, 4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambundo, J.M.; de Souza Martins Gomes, O.; de Souza, A.D.; Machado, R.C.S. Cybersecurity and Major Cyber Threats of Smart Meters: A Systematic Mapping Review. Energies 2025, 18, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, B.M.; Obelheiro, R.R. Software supply chain security: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2024, 46, 853–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohm, M.; Plate, H.; Sykosch, A.; Meier, M. Backstabber’s Knife Collection: A Review of Open Source Software Supply Chain Attacks; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Shruti; Rani, S.; Shabaz, M.; Dutta, A.K.; Ahmed, E.A. Enhancing privacy and security in IoT-based smart grid system using encryption-based fog computing. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 102, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2015 Ukraine Power Grid Hack. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2015_Ukraine_power_grid_hack (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Sridhar, S.; Hahn, A.; Govindarasu, M. Cyber-Physical System Security for the Electric Power Grid. Proc. IEEE 2012, 100, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triton (Malware). Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triton_(malware) (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Vidas, L.; Castro, R.; Pires, A. A Review of the Impact of Hydrogen Integration in Natural Gas Distribution Networks and Electric Smart Grids. Energies 2022, 15, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceseña, E.A.M.; Mancarella, P. Energy Systems Integration in Smart Districts: Robust Optimisation of Multi-Energy Flows in Integrated Electricity, Heat and Gas Networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Acharjee, P.; Bhattacharya, A. Charging Scheduling of Electric Vehicle Incorporating Grid-to-Vehicle and Vehicle-to-Grid Technology Considering in Smart Grid. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2021, 57, 1688–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Clausen, A.; Lin, Y.; Jørgensen, B.N. An overview of digitalization for the building-to-grid ecosystem. Energy Inform. 2021, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerman, J.; Berent, D.; Falter, Z.; Bhunia, S. A Review of Colonial Pipeline Ransomware Attack. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM 23rd International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Internet Computing Workshops (CCGridW), Bangalore, India, 1–4 May 2023; pp. 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ronanki, D.; Karneddi, H. Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure: Review, Cyber Security Considerations, Potential Impacts, Countermeasures, and Future Trends. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2024, 12, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, M.; Pappalardo, S.M.; Bozhilova, M.; Stoianov, N.; Dziech, A.; Stiller, B. Multi-sector Risk Management Framework for Analysis Cybersecurity Challenges and Opportunities. In Multimedia Communications, Services and Security; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, D.; Houmb, S.H.; Erdodi, L. Cyber-Attacks on Energy Infrastructure—A Literature Overview and Perspectives on the Current Situation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwim, E.N.; Mtsweni, J. Systematic Review of Factors that Influence the Cybersecurity Culture. In Human Aspects of Information Security and Assurance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, A.; Tompson, L. Towards a cybersecurity culture-behaviour framework: A rapid evidence review. Comput. Secur. 2025, 148, 104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z. Business ecosystem modeling- the hybrid of system modeling and ecological modeling: An application of the smart grid. Energy Inform. 2019, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.K.; Misra, M. Cyber security threats—Smart grid infrastructure. In Proceedings of the 2016 National Power Systems Conference (NPSC), Bhubaneswar, India, 19–21 December 2016; pp. 1–6. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7858950/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Hasan, M.K.; Habib, A.K.M.A.; Islam, S.; Safie, N.; Abdullah, S.N.H.S.; Pandey, B. DDoS: Distributed denial of service attack in communication standard vulnerabilities in smart grid applications and cyber security with recent developments. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 1318–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirayesh, H.; Zeng, H. Jamming Attacks and Anti-Jamming Strategies in Wireless Networks: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2022, 24, 767–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.N.; Baig, Z.; Zeadally, S. Physical Layer Security for the Smart Grid: Vulnerabilities, Threats, and Countermeasures. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 15, 6522–6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, H.; Zhang, Y.; Han, L.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J.; Ji, X.; Xu, W. Detecting Buffer-Overflow Vulnerabilities in Smart Grid Devices via Automatic Static Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 3rd Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC), Chengdu, China, 15–17 March 2019; pp. 813–817. [Google Scholar]

- Ustun, T.S.; Farooq, S.M.; Hussain, S.M.S. A Novel Approach for Mitigation of Replay and Masquerade Attacks in Smartgrids Using IEC 61850 Standard. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 156044–156053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseinović, A.; Mrdović, S.; Bicakci, K.; Uludag, S. A Survey of Denial-of-Service Attacks and Solutions in the Smart Grid. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 177447–177470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangaresi, V.O.; Alsamhi, S.H. Towards Secure Traffic Signaling in Smart Grids. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd Global Power, Energy and Communication Conference (GPECOM), Antalya, Turkey, 5–8 October 2021; pp. 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Inayat, U.; Zia, M.F.; Mahmood, S.; Berghout, T.; Benbouzid, M. Cybersecurity Enhancement of Smart Grid: Attacks, Methods, and Prospects. Electronics 2022, 11, 3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouslimani, M.; Tayeb, F.B.S.; Amirat, Y.; Benbouzid, M. Replay Attacks on Smart Grids: A Comprehensive Review on Countermeasures. In Proceedings of the IECON 2024—50th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Chicago, IL, USA, 3–6 November 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gunduz, M.Z.; Das, R. Analysis of cyber-attacks on smart grid applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Data Processing (IDAP), Malatya, Turkey, 28–30 September 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, B.; Sarker, A.; Abhi, S.H.; Das, S.K.; Ali, M.F.; Islam, M.M.; Islam, M.R.; Moyeen, S.I.; Rahman Badal, M.F.; Ahamed, M.H.; et al. Potential smart grid vulnerabilities to cyber attacks: Current threats and existing mitigation strategies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Wu, J.; Liang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, X. A Review of Power System False Data Attack Detection Technology Based on Big Data. Information 2024, 15, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olowu, T.O.; Dharmasena, S.; Hernandez, A.; Sarwat, A. Impact Analysis of Cyber Attacks on Smart Grid: A Review and Case Study. In New Research Directions in Solar Energy Technologies; Tyagi, H., Chakraborty, P.R., Powar, S., Agarwal, A.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musleh, A.S.; Chen, G.; Dong, Z.Y. A Survey on the Detection Algorithms for False Data Injection Attacks in Smart Grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 2218–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usama, M.; Aman, M.N. Command Injection Attacks in Smart Grids: A Survey. IEEE Open J. Ind. Appl. 2024, 5, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.; McCombie, S. Stuxnet: The emergence of a new cyber weapon and its implications. J. Polic. Intell. Count. Terror. 2012, 7, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vighneswari, B.D.; Kothai Andal, C. Smart Meter Security—Fraud Detection in Power Theft. In Cloud Computing in Smart Energy Meter Management; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gong, S.; Dimitrovski, A.D.; Li, H. Time Synchronization Attack in Smart Grid: Impact and Analysis. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2013, 4, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, J.; Harding, B.J.; Makela, J.J.; Domínguez-García, A.D. Spoofing GPS Receiver Clock Offset of Phasor Measurement Units. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 3253–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Lee, G. An Effective Wormhole Attack Defence Method for a Smart Meter Mesh Network in an Intelligent Power Grid. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2012, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Gebraeel, N.; Paynabar, K.; Meliopoulos, A.P.S. An Online Approach to Covert Attack Detection and Identification in Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 38, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.; Benedetti, G.; Hamer, S.; Paramitha, R.; Rahman, I.; Tamanna, M.; Tystahl, G.; Zahan, N.; Morrison, P.; Acar, Y.; et al. Research Directions in Software Supply Chain Security. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2025, 34, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lella, I.; Tsekmezoglou, E.; Theocharidou, M.; Magonara, E.; Malatras, A.; Svetozarov Naydenov, R.; Ciobanu, C.; Ardagna, C.; Corbiaux, S.; Van Impe, K.; et al. ENISA Threat Landscape 2023; ENISA Reports; ENISA: Athens, Greece, 2023; Available online: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/enisa-threat-landscape-2023 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- European Parliament; The Commission of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2022/2555 on Measures for a High Common Level of Cybersecurity Across the Union (NIS2 Directive). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2555/oj/eng (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Egozcue, E.; Herreras Rodríguez, D.; Alonso Ortiz, J.; Fidalgo Villar, V.; Tarrafeta, L. ENISA Smart Grid Security Recommendations; European Union Agency for Cybersecurity: Athens, Greece, 2020; Available online: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/ENISA-smart-grid-security-recommendations (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Alouffi, B.; Hasnain, M.; Alharbi, A.; Alosaimi, W.; Alyami, H.; Ayaz, M. A Systematic Literature Review on Cloud Computing Security: Threats and Mitigation Strategies. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 57792–57807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suetor, C.G.; Scrimieri, D.; Qureshi, A.; Awan, I.-U. An Overview of Distributed Firewalls and Controllers Intended for Mobile Cloud Computing. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takiddin, A.; Ismail, M.; Zafar, U.; Serpedin, E. Robust Electricity Theft Detection Against Data Poisoning Attacks in Smart Grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 2675–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardana, S.; Gupta, S.; Donode, A.; Prasad, A.; Karthik, G.M. Defending Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models: Detecting and Preventing Data Poisoning Attacks. In Proceedings of the 2024 Global Conference on Communications and Information Technologies (GCCIT), Bangalore, India, 25–26 October 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pappalardo, S.M.; Niemiec, M.; Bozhilova, M.; Stoianov, N.; Dziech, A.; Stiller, B. Multi-Sector Assessment Framework—A New Approach to Analyse Cybersecurity Challenges and Opportunities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Beyza, J.; Ruiz-Paredes, H.F.; Garcia-Paricio, E.; Yusta, J.M. Assessing the criticality of interdependent power and gas systems using complex networks and load flow techniques. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2020, 540, 123169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhusal, N.; Gautam, M.; Benidris, M. Cybersecurity of Electric Vehicle Smart Charging Management Systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 52nd North American Power Symposium (NAPS), Tempe, AZ, USA, 11–13 April 2021; pp. 1–6. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000684240200104 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Llaria, A.; Dos Santos, J.; Terrasson, G.; Boussaada, Z.; Merlo, C.; Curea, O. Intelligent Buildings in Smart Grids: A Survey on Security and Privacy Issues Related to Energy Management. Energies 2021, 14, 2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, M.A.; Ghafouri, M.; Atallah, R.; Debbabi, M.; Assi, C. Grid Chaos: An uncertainty-conscious robust dynamic EV load-altering attack strategy on power grid stability. Appl. Energy 2024, 363, 122972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Sun, Q.Z.; Qiao, Y. Defending against cyber-attacks in building HVAC systems through energy performance evaluation using a physics-informed dynamic Bayesian network (PIDBN). Energy 2025, 322, 135369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, S.; Pan, S.; Lakshminarayana, S.; Konstantinou, C. Survey of Load-Altering Attacks Against Power Grids: Attack Impact, Detection, and Mitigation. IEEE Open Access J. Power Energy 2025, 12, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presekal, A.; Rajkumar, V.S.; Ştefanov, A.; Pan, K.; Palensky, P. Cyberattacks on Power Systems. In Smart Cyber-Physical Power Systems; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 365–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algin, R.; Tan, H.O.; Akkaya, K. Mitigating Selective Jamming Attacks in Smart Meter Data Collection using Moving Target Defense. In Proceedings of the 13th ACM Symposium on QoS and Security for Wireless and Mobile Networks, Miami, FL, USA, 21–25 November USA; pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Maynard, P.; McLaughlin, K.; Haberler, B. Towards Understanding Man-In-The-Middle Attacks on IEC 60870-5-104 SCADA Networks. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on ICS & SCADA Cyber Security Research 2014, St Pölten, Austria, 11–12 September 2014; pp. 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouffer, K.; Pease, M.; Tang, C.; Zimmerman, T.; Pillitteri, V.; Lightman, S.; Hahn, A.; Saravia, S.; Sherule, A.; Thompson, M. NIST Special Publication 800-82 Revision 3: Guide to Operational Technology (OT) Security; National Institute of Standards Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2022. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-82r3.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Reed, T.C. At the Abyss: An Insider’s History of the Cold War; Presidio Press/Ballantine Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Markey, E.J. Markey Letter and NRC Response on the Slammer Worm Infection at Davis-Besse Nuclear Plant; U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Rockville, MD, USA, 2003. Available online: https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML0329/ML032970134.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Moore, D.; Paxson, V.; Savage, S.; Shannon, C.; Staniford, S.; Weaver, N. Inside the Slammer Worm. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2003, 1, 33–39. Available online: https://skerry-tech.com/papers/2003-slammer.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.; Rowe, D. A survey SCADA of and critical infrastructure incidents. In Proceedings of the 1st Annual conference on Research in information technology, Calgary, AB, Canada, 11–13 October 2012; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. NRC Information Notice 2003-17: Slammer Worm Penetration of Davis-Besse Nuclear Power Station Networks; U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Rockville, MD, USA, 2003. Available online: https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML0324/ML032410430.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Cybersecurity Infrastructure Security Agency. CISA Industrial Control Systems Advisory ICSA-11-041-01A: McAfee Night Dragon Report (Update A); Cybersecurity Infrastructure Security Agency: Arlington, VA, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/ics-advisories/icsa-11-041-01a (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Hemsley, K.E.; Fisher, R.E. History of Industrial Control System Cyber Incidents; Idaho National Laboratory (INL): Idaho Falls, ID, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1505628 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Stergiopoulos, G.; Gritzalis, D.A.; Limnaios, E. Cyber-Attacks on the Oil & Gas Sector: A Survey on Incident Assessment and Attack Patterns. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 128440–128475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langner, R. Stuxnet: Dissecting a Cyberwarfare Weapon. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2011, 9, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnouskos, S. Stuxnet Worm Impact on Industrial Cyber-Physical System Security. In Proceedings of the IECON 2011—37th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 7–10 November 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symantec. Dragonfly: Cyberespionage Attacks Against Energy Suppliers; Security Response: Tempe, AZ, USA, 2014; Available online: https://docs.broadcom.com/doc/dragonfly_threat_against_western_energy_suppliers (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Cybersecurity Infrastructure Security Agency. CISA Industrial Control Systems Alert ICSA-14-281-01: Ongoing Sophisticated Malware Campaign Compromising ICS; Cybersecurity Infrastructure Security Agency: Arlington, VA, USA, 2014. Available online: https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/ics-alerts/ics-alert-14-281-01 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Wangen, G. The Role of Malware in Reported Cyber Espionage: A Review of the Impact and Mechanism. Information 2015, 6, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council on Foreign Relations. Compromise of Saudi Aramco and RasGas. Available online: https://www.cfr.org/cyber-operations/2012/08/16/compromise-of-saudi-aramco-and-rasgas/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- PwC. Under the Lens: The Oil and Gas Sector. In PwC Cyber Threat Operations Report; PwC: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.pwc.de/de/energiewirtschaft/under-the-lens-oil-and-gas-sector.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Whitehead, D.E.; Owens, K.; Gammel, D.; Smith, J. Ukraine cyber-induced power outage: Analysis and practical mitigation strategies. In Proceedings of the 2017 70th Annual Conference for Protective Relay Engineers (CPRE), College Station, TX, USA, 3–6 April 2017; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 62351-6:2020; Power Systems Management and Associated Information Exchange—Data and Communications Security—Part 6: Security for IEC 61850. IEC International Standards: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://webstore.iec.ch/en/publication/63742 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Lee, R.M.; Assante, M.J.; Conway, T. Analysis of the Cyber Attack on the Ukrainian Power Grid: Defense Use Case; E-ISAC: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/3891751/SANS-and-Electricity-Information-Sharing-and.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Mekdad, Y.; Bernieri, G.; Conti, M.; Fergougui, A.E. A threat model method for ICS malware: The TRISIS case. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM International Conference on Computing Frontiers, Virtual Event, 11–13 May 2021; pp. 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Singh, S.K.; Salim, M.M.; El Azzaoui, A.; Park, J.H. Ransomware-based Cyber Attacks: A Comprehensive Survey. J. Internet Technol. 2022, 23, 1557–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhole, M.; Sauter, T.; Kastner, W. Enhancing Industrial Cybersecurity: Insights from Analyzing Threat Groups and Strategies in Operational Technology Environments. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2025, 6, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. FBI Statement on Compromise of Colonial Pipeline Networks. Available online: https://www.fbi.gov/news/press-releases/fbi-statement-on-compromise-of-colonial-pipeline-networks (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Bing, C.; Kelly, S. Colonial Pipeline halts all pipeline operations after cybersecurity attack. Reuters, 8 May 2021. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/technology/colonial-pipeline-halts-all-pipeline-operations-after-cybersecurity-attack-2021-05-08/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- S&P Global. Energy Security Sentinel: Cyberattacks Surge in 2022 as Hackers Target Commodities. 2022. Available online: https://www.spglobal.com/energy/en/news-research/latest-news/electric-power/101022-energy-security-sentinel-cyberattacks-surge-in-2022-as-hackers-target-commodities (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Thompson, K. Energy Dilemmas in the 2023 Energy Trilemma. 2023. Available online: https://itegriti.com/2023/cybersecurity/energy-dilemmas-in-2023-energy-trilemma/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- European Union Agency for Cybersecurity. ENISA Threat Landscape 2022; ENISA: Athens, Greece, 2022; Available online: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/ENISA%20Threat%20Landscape%202022.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Eset Research. Industroyer2: Industroyer reloaded. We Live Security, 12 April 2022. Available online: https://www.welivesecurity.com/2022/04/12/industroyer2-industroyer-reloaded/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Cybersecurity Infrastructure Security Agency. Cybersecurity Advisory AA23-144A: [Title of CISA Advisory AA23-144A]; CISA: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa23-144a (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- HSE Public Relations and Marketing Communications. HSE Successfully Resolves Situation Related To Hacking of HSE Information System. Available online: https://www.hse.si/en/hse-successfully-resolves-situation-related-to-hacking-of-hse-information-system/ (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- European Union Agency for Cybersecurity. ENISA Threat Landscape 2024; ENISA: Athens, Greece, 2024; Available online: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/enisa-threat-landscape-2024 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Reuters. Iran repelled large cyber attack on Sunday. Reuters, 28 April 2025. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iran-repelled-large-cyber-attack-sunday-2025-04-28/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Rose, S.; Borchert, O.; Mitchell, S.; Connelly, S. NIST Special Publication 800-207: Zero Trust Architecture; National Institute of Standards Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/sp/800/207/final (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Demirci, S.; Sagiroglu, S. Software-Defined Networking for Improving Security in Smart Grid Systems. In Proceedings of the 2018 7th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA), Paris, France, 14–17 October 2018; pp. 1021–1026. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8567005/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Ugoaghalam, U.J.; Idika, C.N.; Enyejo, L.A. Zero Trust Architecture Leveraging AI-Driven Behavior Analytics for Industrial Control Systems in Energy Distribution Networks. Int. J. Sci. Res. Comput. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2023, 9, 685–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation. CIP-013-1 R1 & R2—Supply Chain Management NATF; North American Electric Reliability Corporation: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.nerc.com/globalassets/programs/compliance/compliance-guidance/implementation/cip-013-1-r1-r2--supply-chain-management-natf.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Souppaya, M.; Scarfone, K. NIST Special Publication 800-193: Platform-Platform Firmware Resiliency Guidelines; National Institute of Standards Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-193.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Revised Critical Infrastructure Protection Reliability Standards. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, 2016. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/07/29/2016-17842/revised-critical-infrastructure-protection-reliability-standards (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Mollah, M.B.; Zhao, J.; Niyato, D.; Lam, K.Y.; Zhang, X.; Ghias, A.M.Y.M.; Koh, L.H.; Yang, L. Blockchain for Future Smart Grid: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 18–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andoni, M.; Robu, V.; Flynn, D.; Abram, S.; Geach, D.; Jenkins, D.; McCallum, P.; Peacock, A. Blockchain technology in the energy sector: A systematic review of challenges and opportunities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 100, 143–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengelkamp, E.; Gärttner, J.; Rock, K.; Kessler, S.; Orsini, L.; Weinhardt, C. Designing microgrid energy markets: A case study: The Brooklyn Microgrid. Appl. Energy 2018, 210, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorri, A.; Kanhere, S.S.; Jurdak, R.; Gauravaram, P. Blockchain for IoT security and privacy: The case study of a smart home. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops (PerCom Workshops), Kona, HI, USA, 13–17 March 2017; pp. 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M.; Kim, H. Blockchain-based secure firmware management system in IoT environment. In Proceedings of the 2019 21st International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT), PyeongChang, Republic of Korea, 17–20 February 2019; pp. 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Arshad, M.J. A Comprehensive Review of Blockchain and Machine Learning Integration for Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading in Smart Grids. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 92756–92782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylrea, M.; Gourisetti, S.N.G. Blockchain for smart grid resilience: Exchanging distributed energy at speed, scale and security. In Proceedings of the 2017 Resilience Week (RWS), Wilmington, DE, USA, 18–22 September 2017; pp. 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tibrewal, I.; Srivastava, M.; Tyagi, A.K. Blockchain Technology for Securing Cyber-Infrastructure and Internet of Things Networks. In Intelligent Interactive Multimedia Systems for e-Healthcare Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2021; p. 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmada, J.; Rizwanb, M.; Alia, S.F.; Inayata, U.; Muqeet, H.A.; Imran, M.; Awotwe, T. Cybersecurity in smart microgrids using blockchain-federated learning and quantum-safe approaches: A comprehensive review. Appl. Energy 2025, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erba, A.; Müller, A.; Tippenhauer, N.O. Security Analysis of Vendor Implementations of the OPC UA Protocol for Industrial Control Systems. In Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on CPS & IoT Security and Privacy, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 7 November 2022; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, R.; Obermeier, S.; Schneider, J. A security evaluation of IEC 62351. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2017, 34, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Post-Quantum Cryptography FIPS Approved. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/news/2024/postquantum-cryptography-fips-approved (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/post-quantum-cryptography/post-quantum-cryptography-standardization (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Bera, B.; Sikdar, B. Securing Post-Quantum Communication for Smart Grid Applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Control, and Computing Technologies for Smart Grids (SmartGridComm), Oslo, Norway, 17–20 September 2024; pp. 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travagnin, M.; Lewis, A.M. Quantum Key Distribution In-field Implementations: Technology Assessment of QKD Deployments; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019; Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC118150/quantum_communication_state-of-the-art__review_4.0_final.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Thwe, M.M.; Ştefanov, A.; Rajkumar, V.S.; Palensky, P. Digital Twins for Power Systems: Review of Current Practices, Requirements, Enabling Technologies, Data Federation, and Challenges. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 105517–105540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, B.N.; Ma, Z.G. Digital Twin of the European Electricity Grid: A Review of Regulatory Barriers, Technological Challenges, and Economic Opportunities. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, N.K.; Venugopalan, S.; Wong, T.K.; Leu, N.J. An electric power digital twin for cyber security testing, research and education. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 101, 108061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppolino, L.; Nardone, R.; Petruolo, A.; Romano, L. Building Cyber-Resilient Smart Grids with Digital Twins and Data Spaces. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayghe, A. Digital Twin-Driven Intrusion Detection for Industrial SCADA: A Cyber-Physical Case Study. Sensors 2025, 25, 4963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, S.A.; Ghadim, A.D.; Balador, A.; Alimadadi, Z.; Papadimitratos, P. Digital Twin-based Intrusion Detection for Industrial Control Systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops and other Affiliated Events (PerCom Workshops), Pisa, Italy, 21–25 March 2022; pp. 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabot, F.; Ben Mariem, S.; Dekeyne, G.; Duchesne, L.; Bahmanyar, A.; Ernst, D.; Bretteville, O.; Vermeulen, T.; Herve, D.; Saludjian, L.; et al. Toward a Cyber-Physical Digital Twin for Operator Training: Real-Time Co-Simulation of the French Grid; Liege Universite Library: Liege, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmalak, M.; Gautam, M.; Thapa, J.; Hotchkiss, E.; Benidris, M. Defensive Islanding to Enhance the Resilience of Distribution Systems against Cyber-induced Failures. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Industry Applications Society Annual Meeting (IAS), Detroit, MI, USA, 9–14 October 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, A.A.; Amin, S.; Sinopoli, B.; Giani, A.; Perrig, A.; Sastry, S. Challenges for Securing Cyber Physical Systems. 2009. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Challenges-for-Securing-Cyber-Physical-Systems-C%C3%A1rdenas-Amin/d51497e5827cc00d9d00c26e27a769d42284cfba (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Souppaya, M.; Scarfone, K. NIST Special Publication 800-184: Guide for Cybersecurity Event Recovery; National Institute of Standards Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2016. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/sp/800/184/final (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation. CIP-002-5.1a: Cyber Security—BES Cyber System Categorization; NERC Reliability Standards; North American Electric Reliability Corporation: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.nerc.com/standards/reliability-standards/cip/cip-002-5.1a (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Electricity Power Supply Association. Bridging the Gap: How Better Gas-Electric Coordination Is Strengthening Grid Reliability. Available online: https://epsa.org/bridging-the-gap-how-better-gas-electric-coordination-is-strengthening-grid-reliability/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation. E-ISAC Electricity Information Sharing and Analysis Center. Available online: https://www.nerc.com/programs/e-isac (accessed on 12 December 2025).

| Security Challenge | Architectural Component or Layer (Section 3) | Key Interfaces or Dependencies | Security Exposure Created |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extensive attack surface and interconnectivity | AMI, field devices, communication networks | Wireless mesh, IP networks, gateways | Multiple entry points and lateral movement |

| Legacy devices and protocols | SCADA, RTUs, protection relays | Legacy protocols, embedded firmware | Lack of authentication and encryption |

| Real-time operational constraints | Control centres, protection systems | Time-critical control loops | Limited applicability of conventional security controls |

| Cyber-physical safety dependence | SCADA, protection and safety systems | Control-command interfaces | Direct physical impact from cyber manipulation |

| Human and insider factors | Control centres, engineering workstations | Credential-based access | Privileged misuse and social engineering |

| Privacy and data sensitivity | AMI, data management systems | Meter-to-backend data flows | Exposure of personal and operational data |

| Cloud and platform dependence | Cloud-hosted EMS, DER platforms | APIs, identity federation | Loss of control through third-party compromise |

| Software supply chain reliance | Field devices, vendor tools | Firmware updates, configuration software | Trusted update abuse |

| AI-driven and algorithmic control | Analytics platforms, EMS | Data pipelines, model inputs | Manipulation of automated decisions |

| Sector coupling | DERs, EV charging, building systems | Cross-domain data exchange | Indirect attack propagation |

| Regulatory and governance constraints | Market systems, data platforms | Compliance and reporting interfaces | Reduced monitoring and delayed response |

| Security Challenge (Section 4) | Underlying Vulnerability or Constraint | Representative Cyberthreats and Attack Vectors | Primary Security Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extensive attack surface and interconnectivity | Large number of heterogeneous and networked devices | Network intrusion, spoofing, denial-of-service, lateral movement | Availability, integrity |

| Legacy devices and insecure protocols | Lack of encryption, authentication, and patchability | Command injection, replay attacks, protocol abuse | Integrity, availability |

| Real-time operational constraints | Limited tolerance for latency and system shutdown | Stealthy manipulation, persistence-focused intrusions | Integrity |

| Cyber-physical safety dependence | Direct coupling between cyber control and physical processes | Malicious control actions, safety system compromise | Integrity, availability |

| Human factors and insider access | Privileged access and susceptibility to social engineering | Credential theft, insider misuse, phishing-enabled intrusions | Confidentiality, integrity |

| Privacy and data protection requirements | High-resolution consumption and operational data | Data exfiltration, traffic analysis, inference attacks | Confidentiality |

| Cloud and third-party platform dependence | Externalised infrastructure and shared services | Platform compromise, API abuse, service outage | Availability, confidentiality |

| Software supply chain reliance | Trusted updates and vendor software dependencies | Trojanised firmware, malicious updates, backdoored tools | Integrity, availability |

| AI-driven and algorithmic control | Dependence on data quality and opaque decision logic | Data poisoning, adversarial inputs, model manipulation | Integrity |

| Sector coupling and cross-infrastructure integration | Interdependencies with non-electrical systems | Indirect load manipulation, cross-domain propagation | Availability, integrity |

| Regulatory and governance constraints | Limited monitoring and delayed response | Attack amplification through compliance gaps | Availability, integrity |

| Cyber Incident (Year) | Targeted System or Asset | Primary Cyberthreats and Attack Vectors (Section 5) | Security Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Siberian gas pipeline (1982) | Industrial control software | Software supply chain compromise, malicious logic insertion | Physical damage to pipeline infrastructure following abnormal operation |

| Davis–Besse nuclear plant (2003) | Safety monitoring systems | Network worm propagation, denial-of-service | Loss of safety monitoring for several hours |

| Night Dragon campaign (2009) | Energy sector enterprise networks | Credential theft, long-term espionage | Theft of sensitive information and increased exposure of energy sector organisations without confirmed immediate operational disruption |

| Stuxnet (2010) | Industrial PLCs | Malware-driven control logic manipulation | Physical damage to nuclear enrichment equipment |

| Dragonfly campaigns (2011–2014) | Energy utilities and vendors | Supply chain compromise, credential harvesting | Compromise of energy sector networks enabling intelligence collection and potential access to operational environments; no publicly confirmed power outage |

| Shamoon (2012) | Energy enterprise IT systems | Destructive malware | Destruction of data and prolonged business disruption |

| Ukraine power grid (2015) | Distribution SCADA systems | Credential abuse, remote command execution | Coordinated power outages affecting hundreds of thousands |

| Ukraine Industroyer (2016) | Transmission substation automation | Protocol-aware malware | Temporary loss of electricity supply |

| Triton (2017) | Safety instrumented systems | Safety controller manipulation | Potential safety hazard and forced plant shutdown |

| EKANS ransomware (2019) | Industrial control-supporting systems | OT-aware ransomware | Disruption of industrial operations and increased risk to availability in operational technology environments |

| Colonial Pipeline (2021) | Enterprise IT systems | Ransomware, IT–OT dependency exploitation | Temporary shutdown of fuel distribution |

| Viasat satellite disruption (2022) | Satellite communication links | Platform and service compromise | Loss of communications affecting grid operations |

| Industroyer2 (2022) | Substation automation | Protocol-aware malware | Attempted power outages mitigated by defensive actions |

| Volt Typhoon campaign (2023) | Energy and utility enterprise environments | Credential abuse, living off the land techniques, access persistence | No confirmed disruption of energy supply and increased risk of latent compromise |

| Holding Slovenske Elektrarne ransomware (2023) | Energy enterprise IT systems | Ransomware | Disruption of corporate operations without impact on electricity generation |

| Continued cyber operations against Ukrainian energy infrastructure (2024) | Energy sector operational coordination and supporting control environments | Sustained intrusion activity targeting operational coordination and restoration processes | Ongoing operational stress and increased recovery complexity |

| Reported cyberattack against Iranian national infrastructure (2025) | National critical infrastructure with energy systems implied | Undisclosed attack techniques reported by national authorities | No confirmed service disruption and the attack reportedly detected and repelled |

| Cyber Incident (Year) | Primary Vulnerability Exposed | Relevant Emerging Solution Classes | Resilience Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Siberian gas pipeline (1982) | Trusted software without verification | Secure firmware signing, supply chain governance | Integrity assurance |

| Davis–Besse nuclear plant (2003) | Insufficient segmentation and patching | Network segmentation, zero-trust architectures | Availability preservation |

| Night Dragon campaign (2009) | Undetected long-term intrusion | Continuous monitoring, AI-based anomaly detection | Early detection |

| Stuxnet (2010) | Manipulation of control logic | Digital twins, integrity verification, secure PLC updates | Safe operation |

| Dragonfly campaigns (2011–2014) | Vendor trust exploitation | Supply chain controls, identity-based access | Access containment |

| Shamoon (2012) | Enterprise IT fragility | Cyber-resilient design, backup and recovery planning | Operational continuity |

| Ukraine power grid (2015) | Credential abuse and OT exposure | Multi-factor authentication, segmentation, manual fallback | Controlled recovery |

| Ukraine Industroyer (2016) | Protocol-aware malware | Protocol validation, digital twins, intrusion detection | Impact limitation |

| Triton (2017) | Safety system compromise | Independent safety system hardening, anomaly detection | Safety assurance |

| EKANS ransomware (2019) | OT-aware extortion | Zero trust, resilient architecture | Damage containment |

| Colonial Pipeline (2021) | IT–OT dependency | Segmentation, governance coordination | Operational continuity |

| Viasat satellite disruption (2022) | Platform dependency | Redundant communications, resilience engineering | Service continuity |

| Industroyer2 (2022) | Advanced OT malware | Improved monitoring, coordinated response | Attack prevention |

| Volt Typhoon campaign (2023) | Undetected long-term access and credential abuse | Zero trust architectures, continuous monitoring, identity-centric security | Early detection |

| Holding Slovenske Elektrarne ransomware (2023) | Enterprise IT–OT dependency and business process fragility | Network segmentation, cyber-resilient design, backup and recovery planning | Operational continuity |

| Continued cyber operations against Ukrainian energy sector (2024) | Sustained cyber pressure during conflict conditions | Digital twins, situational awareness, resilient operational procedures | Sustained operation |

| Reported repelled cyberattack against Iranian infrastructure (2025) | Strategic targeting with limited public visibility | Advanced monitoring, coordinated response, resilience-oriented defence | Impact limitation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jørgensen, B.N.; Ma, Z.G. Cybersecurity and Resilience of Smart Grids: A Review of Threat Landscape, Incidents, and Emerging Solutions. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020981

Jørgensen BN, Ma ZG. Cybersecurity and Resilience of Smart Grids: A Review of Threat Landscape, Incidents, and Emerging Solutions. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):981. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020981

Chicago/Turabian StyleJørgensen, Bo Nørregaard, and Zheng Grace Ma. 2026. "Cybersecurity and Resilience of Smart Grids: A Review of Threat Landscape, Incidents, and Emerging Solutions" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020981

APA StyleJørgensen, B. N., & Ma, Z. G. (2026). Cybersecurity and Resilience of Smart Grids: A Review of Threat Landscape, Incidents, and Emerging Solutions. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020981