Fast Helmet Detection in Low-Resolution Surveillance via Super-Resolution and ROI-Guided Inference

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional and CNN-Based Object Detection

2.2. Image and Video Super-Resolution for Detection Enhancement

2.3. Helmet Detection in Complex and UAV-Based Scenarios

3. Method

3.1. Helmet Detection Framework

3.2. Direct Super-Resolution Preprocessing

3.3. ROI-Guided Super-Resolution and Detection

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Dataset and Experimental Setup

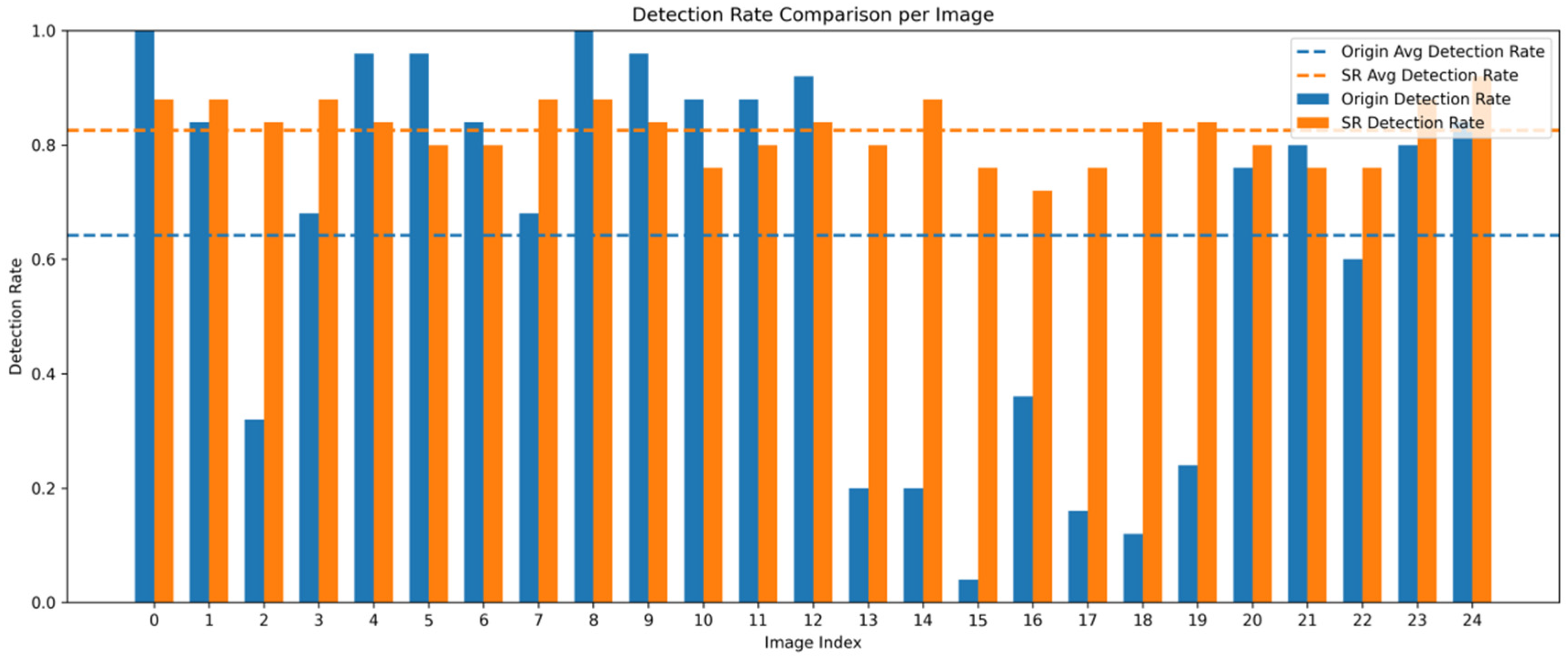

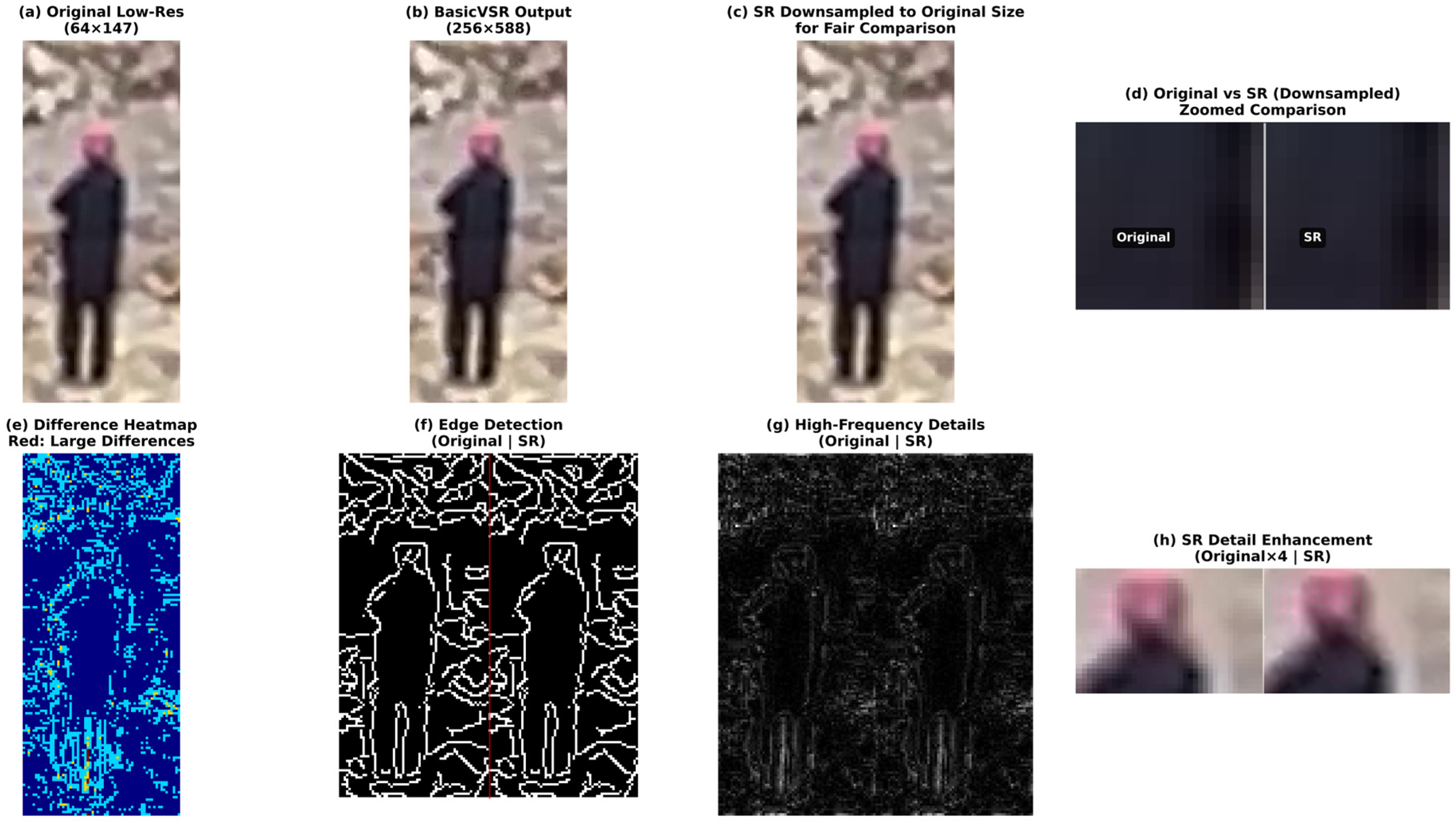

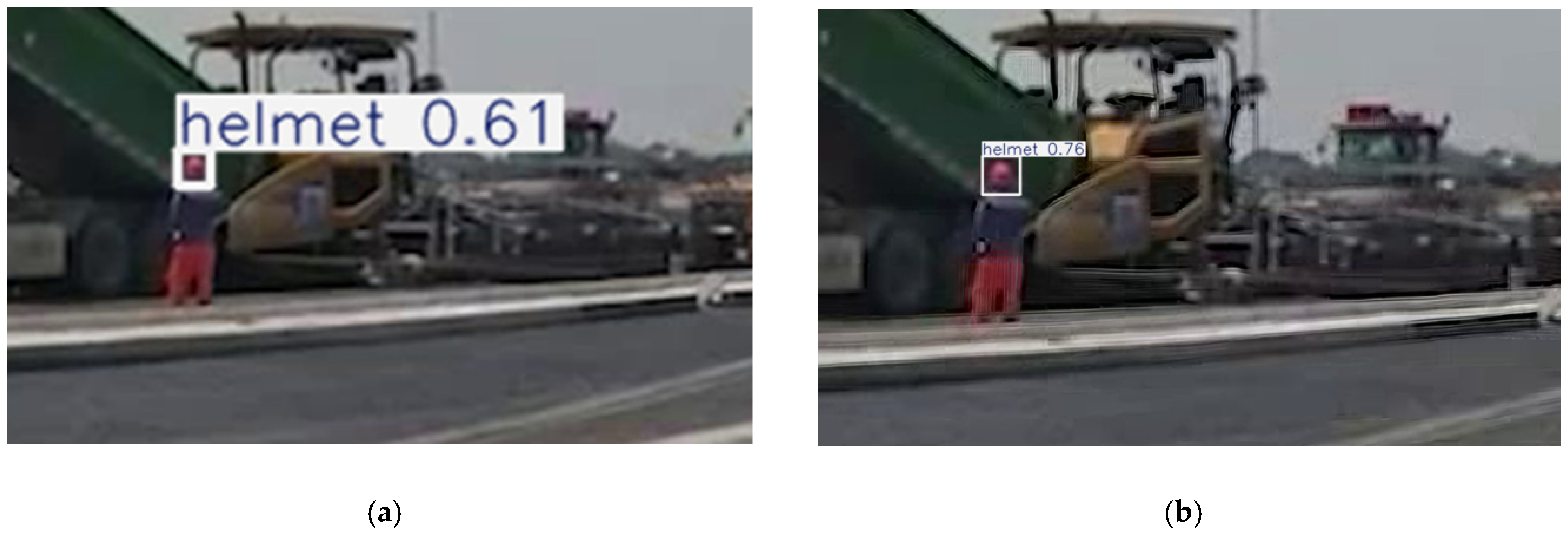

4.2. Performance of Super-Resolution

4.3. Impact of ROI-Strategy on Processing Time

4.4. End-to-End Latency and Real-Time Applicability Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| EH-DETR | Enhanced two-wheeler Helmet Detection TRansformer |

| HR | High-Resolution |

| LR | Low-Resolution |

| ROI | Region Of Interest |

| SR | Super-Resolution |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| VSR | Video Super-Resolution |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

References

- Dhillon, B.S. Mining equipment safety: A review, analysis methods and improvement strategies. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2009, 23, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Nehad, E.; Zhu, Z. Hardhat-wearing detection for enhancing on-site safety of construction workers. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2015, 141, 04015024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kang, D. Artificial intelligence and smart technologies in safety management: A comprehensive analysis across multiple industries. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Bai, T.; Gao, X. Monitoring and Identification of Road Construction Safety Factors via UAV. Sensors 2022, 22, 8797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, M. Operational Environment Impact on Sensor Capabilities in Special Purpose Unmanned Ground Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2024 21st International Conference on Mechatronics-Mechatronika (ME), Prague, Czech Republic, 10–13 December 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, A.; Wang, K.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y. Impact of Adverse Weather and Image Distortions on Vision-Based UAV Detection: A Performance Evaluation of Deep Learning Models. Drones 2024, 8, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, X.; Shen, H.; Hu, J.; Luo, L. Performance evaluation of low resolution visual tracking for unmanned aerial vehicles. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 33, 2229–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, J.; Lin, W.; Li, Z. Performance Evaluation of Visual Tracking Algorithms on Video Sequences With Quality Degradation. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 2430–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultralytics. YOLOv26: The Future of Real-Time State-of-the-Art Object Detection. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolo26/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Viola, P.; Jones, M. Rapid object detection using a boosted cascade of simple features. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Kauai, HI, USA, 8–14 December 2001; Volume 1, p. I. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, M.; Varshosaz, M.; Pirasteh, S.; Shamsipour, G. Optimizing Sector Ring Histogram of Oriented Gradients for human injured detection from drone images. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2021, 12, 581–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, T.; Pietikäinen, M.; Mäenpää, T. Multiresolution gray-scale and rotation invariant texture classification with local binary patterns. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 24, 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, G.; Wen, Z. Fast SVM classifier for large-scale classification problems. Inf. Sci. 2023, 642, 119136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstikhin, I.O.; Houlsby, N.; Kolesnikov, A.; Beyer, L.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Yung, J.; Steiner, A.; Keysers, D.; Uszkoreit, J.; et al. Mlp-mixer: An all-mlp architecture for vision. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 24261–24272. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1311.2524. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.02640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Loy, C.C.; He, K.; Tang, X. Learning a deep convolutional network for image super-resolution. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2014; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, K.M. Accurate image super-resolution using very deep convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1646–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Li, K.; Wang, L.; Zhong, B.; Fu, Y. Image super-resolution using very deep residual channel attention networks. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.C.K.; Zhou, S.; Xu, X.; Loy, C.C. BasicVSR++: Improving video super-resolution with enhanced propagation and alignment. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 5972–5981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doungmala, P.; Klubsuwan, K. Helmet wearing detection in Thailand using Haar like feature and circle hough transform on image processing. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (CIT), Nadi, Fiji, 8–10 December 2016; pp. 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Wang, Z. RBFPDet: An anchor-free helmet wearing detection method. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 5013–5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yue, X.; Lu, M.; He, P. EH-DETR: Enhanced two-wheeler helmet detection transformer for small and complex scenes. J. Electron. Imaging 2025, 34, 013035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Seo, S. UAV low-altitude remote sensing inspection system using a small target detection network for helmet wear detection. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Choudhary, M.; Mishra, R.; Chaulya, S.K.; Prasad, G.M.; Mandal, S.K.; Banerjee, G. Artificial intelligent based smart system for safe mining during foggy weather. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2022, 34, e6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Fu, Q.; He, M.; Jiang, D.; Hao, Z. Detection algorithm of safety helmet wearing based on deep learning. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2021, 33, e6234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Hong, X.; Sheng, Y.; Sun, L. YOLO-Helmet: A novel algorithm for detecting dense small safety helmets in construction scenes. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 107170–107180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, S.; Qin, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, Q.; Tan, Q. Detection of helmet use among construction workers via helmet-head region matching and state tracking. Autom. Constr. 2025, 171, 105987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Ying, C.; Tian, Z.; Dong, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, X.; Jiang, Z. YOLOv8s-SNC: An improved safety-helmet-wearing detection algorithm based on YOLOv8. Buildings 2024, 14, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, P.; Wu, Q. Safety helmet detection based on improved YOLOv7-tiny with multiple feature enhancement. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2024, 21, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhang, T.; Yi, W. An improved YOLOv8 safety helmet wearing detection network. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Xie, Q. Safety Helmet-Wearing Detection System for Manufacturing Workshop Based on Improved YOLOv7. J. Sens. 2023, 2023, 7230463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhan, B.; Han, J.; Liu, Y. A super-resolution reconstruction driven helmet detection workflow. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultralytics. Optimizing Ultralytics YOLO Models with the TensorRT Integration. Ultralytics Blog. 2024. Available online: https://www.ultralytics.com/zh/blog/optimizing-ultralytics-yolo-models-with-the-tensorrt-integration (accessed on 8 January 2026).

| Detection Strategies | Average Confidence | Recall | F1 Score | Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8 | 0.210 | 0.066 | 0.124 | 1.0 |

| Proposed SR & YOLOv5 [33] | 0.493 | 0.629 | 0.773 | 1.0 |

| ROI Grid & YOLOv8 | 0.406 | 0.598 | 0.748 | 1.0 |

| ROI Grid & BasicVSR++ & YOLOv8 | 0.632 | 0.825 | 0.904 | 1.0 |

| SR Strategies | Image Size (pixels) | Total Time (s) | Average Time per Frame (s) | Frames per Seconds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-Frame SR | 3840 × 2160 | (GPU overflow) | - | - |

| Cropped SR | 462 × 260 | 49.86 | 1.994 | 0.502 |

| ROI-Guided SR | around 150 × 64 1 | 4.69 | 0.188 | 5.330 |

| Processing Strategy | Person Detection | ROI Cropping | Super-Resolution | Helmet Detection | Total Latency | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8 | - | - | - | 28.3 | 28.3 | 35.3 |

| Full-Frame SR & YOLOv8 | - | - | (GPU overflow) | - | - | - |

| Proposed SR & YOLOv5 [33] | - | - | 1286.3 | 38.9 | 1325.2 | 0.75 |

| ROI-Guided SR & YOLOv8 | 33.9 | 0.4 | 187.6 | 7.8 | 229.7 | 4.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

He, T.; Wang, Z.; Yang, L. Fast Helmet Detection in Low-Resolution Surveillance via Super-Resolution and ROI-Guided Inference. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 967. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020967

He T, Wang Z, Yang L. Fast Helmet Detection in Low-Resolution Surveillance via Super-Resolution and ROI-Guided Inference. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):967. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020967

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Taiming, Ziyue Wang, and Lu Yang. 2026. "Fast Helmet Detection in Low-Resolution Surveillance via Super-Resolution and ROI-Guided Inference" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 967. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020967

APA StyleHe, T., Wang, Z., & Yang, L. (2026). Fast Helmet Detection in Low-Resolution Surveillance via Super-Resolution and ROI-Guided Inference. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 967. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020967