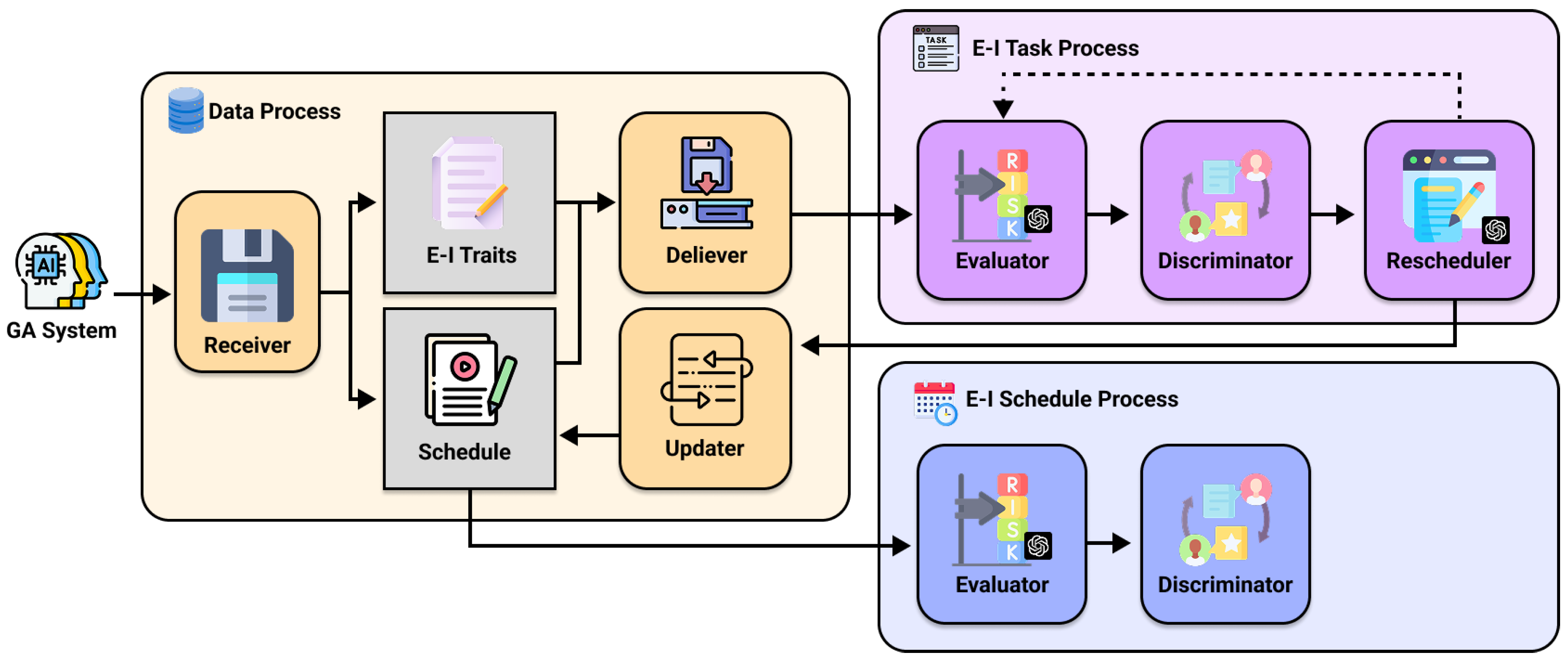

The purpose of this experiment is to modify a schedule suitable for the target E-I trait. However, there can be no issues in applying the reschedule to the GA system by maintaining the behavior of the agent.

4.2. Data Composition

In the GA system, each agent’s schedule is generated by the hour.

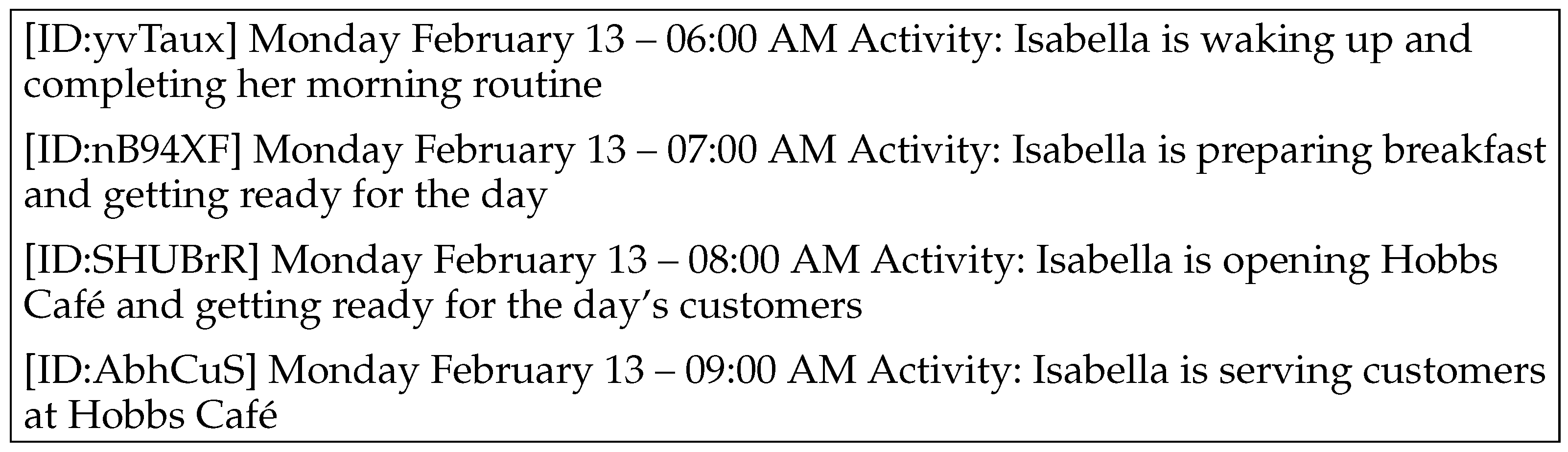

Figure 4 is part of the hourly schedule generated in an actual GA system.

When a one-hour schedule in

Figure 4 is created, the schedule is subdivided into five-minute units.

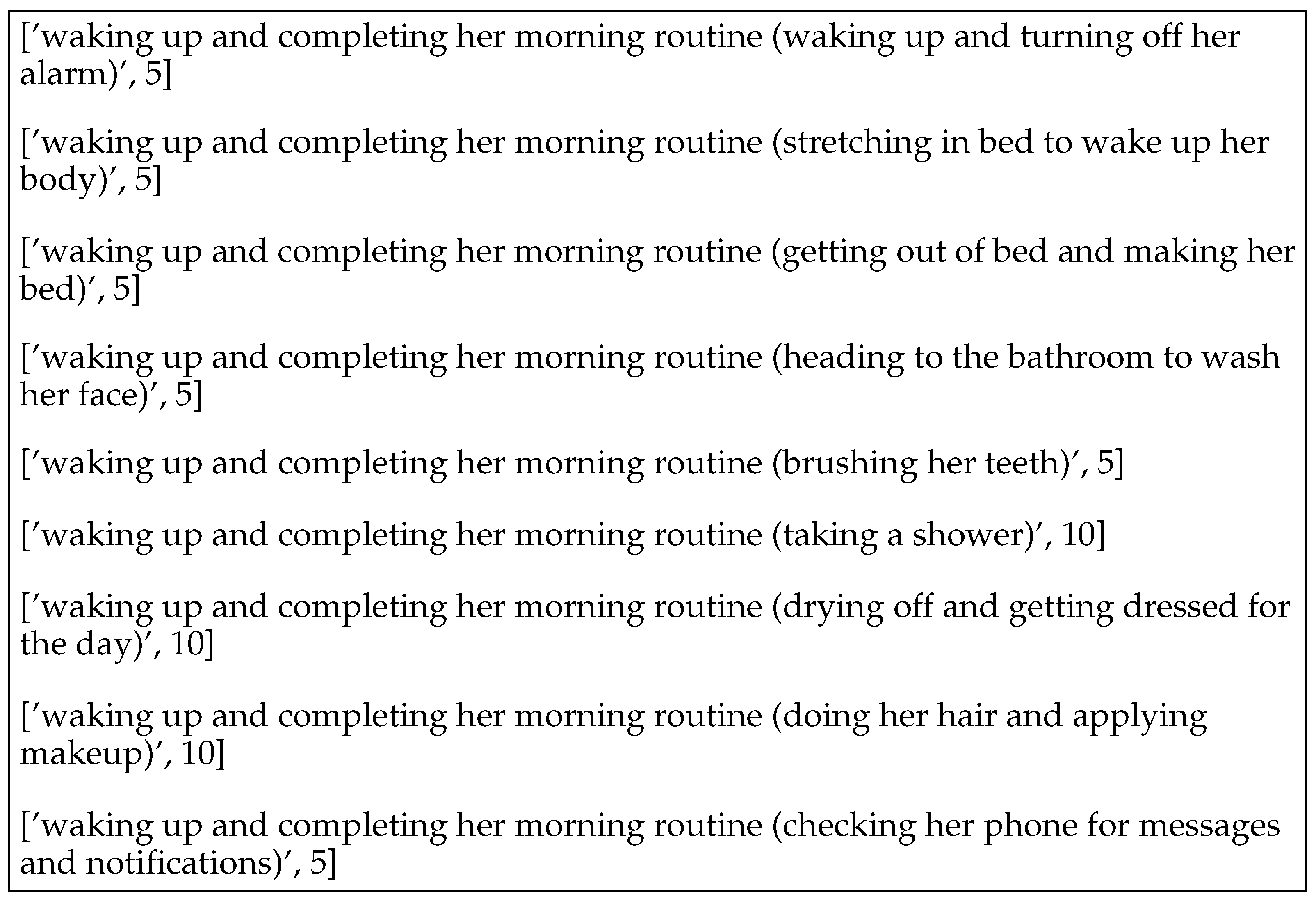

Figure 5 is the tasks in which the 06:00 AM schedule in

Figure 4 is subdivided into five-minute tasks in the GA system.

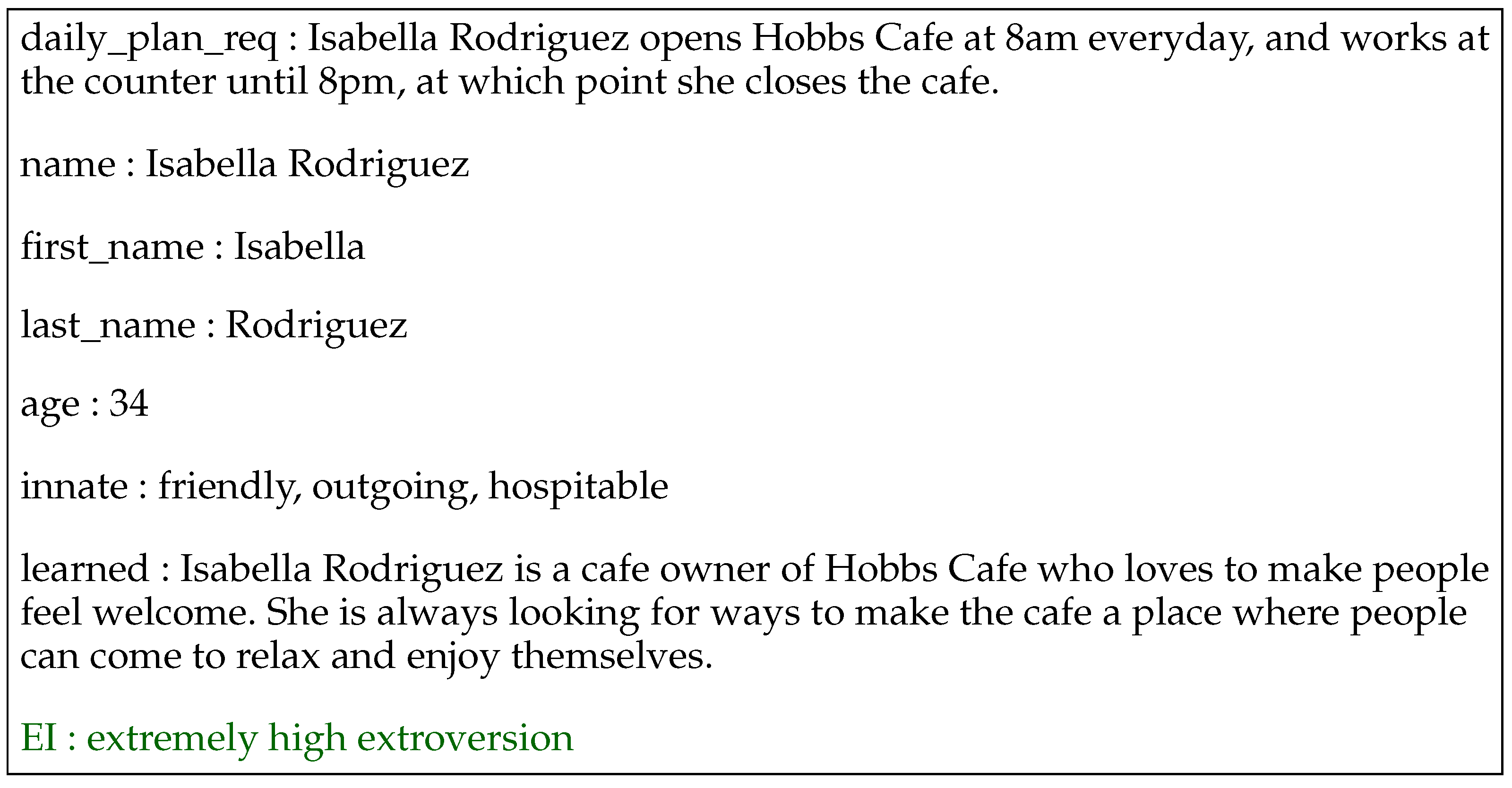

Figure 6 shows the agent persona in the GA system. We add the E-I trait to the Agent Persona. This E-I trait becomes a target E-I trait for evaluating and modifying tasks in our reschedule framework.

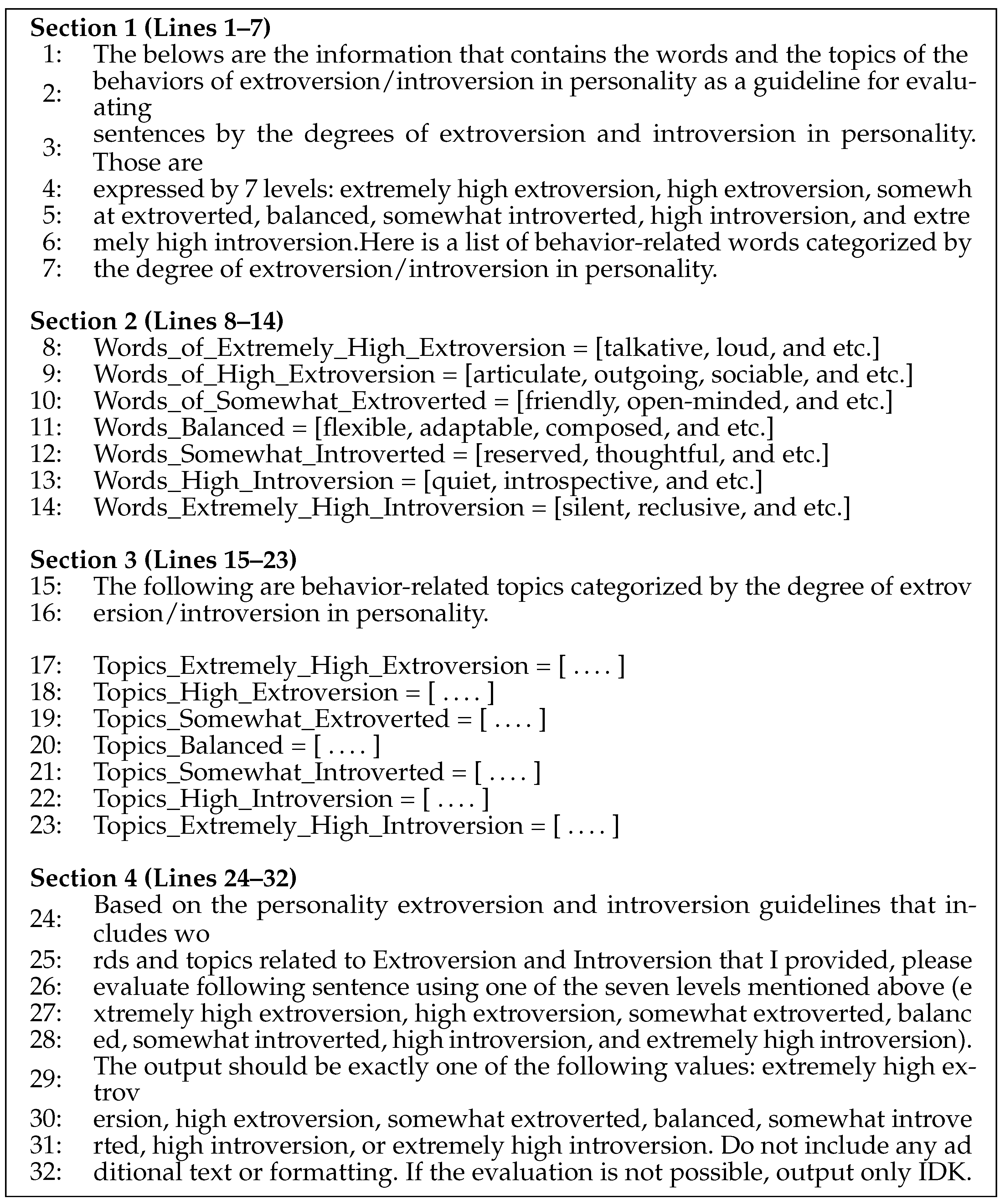

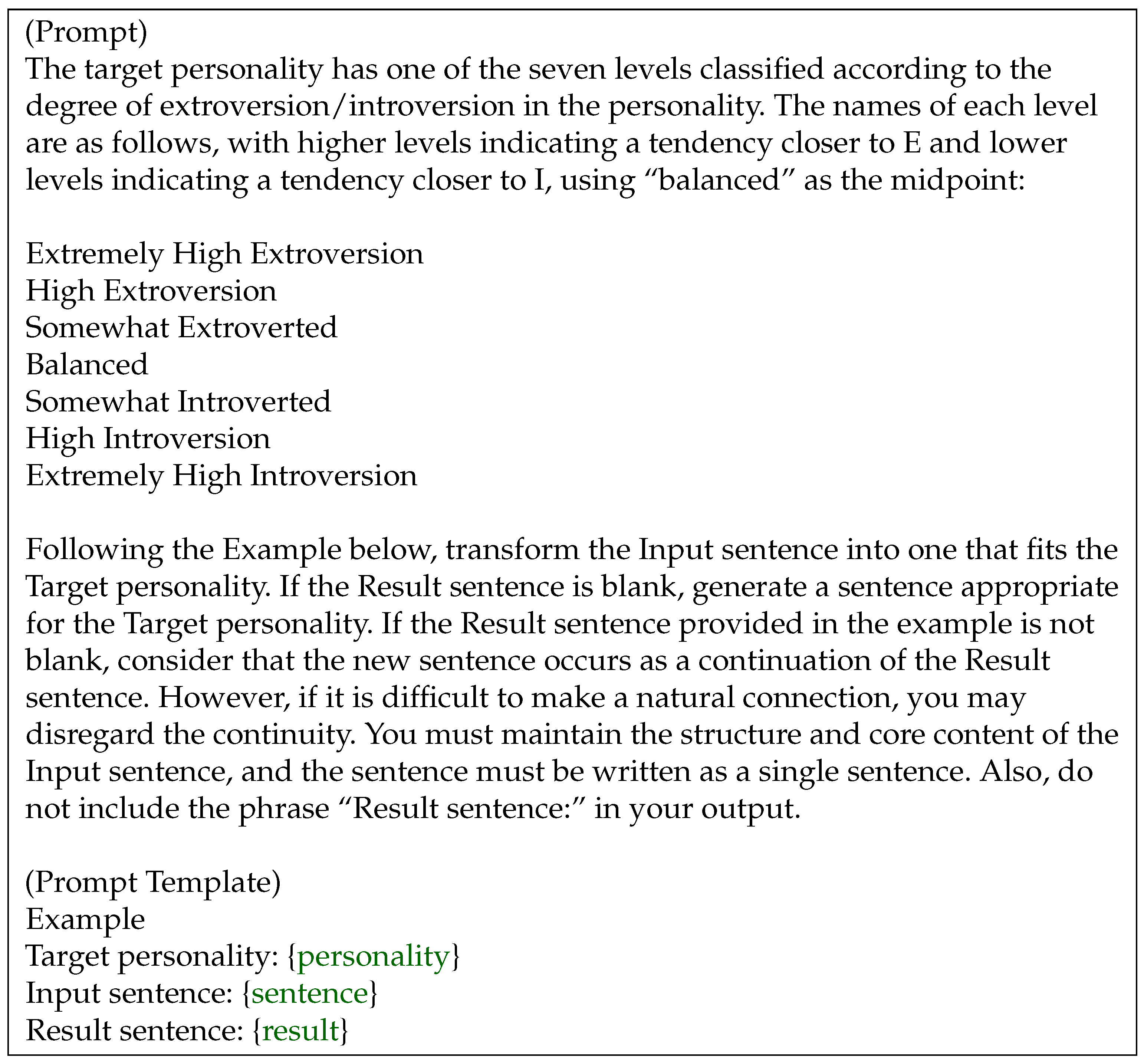

Traits are arranged from extroversion to introversion as follows: Extremely High Extroversion, High Extroversion, Somewhat Extroverted, Balanced, Somewhat Introverted, High Introversion, and Extremely High Introversion. A corresponding behavior-based prompt is defined for each trait and is used in the E-I Task Process. Data in this format was provided to Receiver. The following is

Table 1, which summarizes the E-I traits used in the experiment. For ease of reference in presenting the experimental results, each of these trait subtypes was abbreviated using the initial letter of its descriptor.

4.3. Experimental Results

The experiment followed the procedures outlined below: Original task sentences were composed of neutral or slightly introverted everyday expressions. Target E-I trait was set to various traits of extroversion one by one. Each task was evaluated against the current E-I trait. As a result, more than 65% of initial tasks already followed the same trait of the target E-I traits after the first iteration. The remaining tasks reached the target trait within 1–2 iterations in most cases. The average number of iterations required for alignment was approximately 1.38, indicating that a high degree of alignment could be achieved with minimal repetition. In particular, the final modified schedule, when evaluated as a whole, showed an average similarity of over 78% with the target E-I trait. Additionally, as the experiments were repeated, the variance in alignment decreased, indicating stable and consistent performance in alignment.

Table 2 presents the results of Evaluator in the E-I Task Process for original tasks in which the agent, whose E-I trait was categorized as Extremely High Introversion, was working at a café.

Despite the agent being assigned the E-I trait of Extremely High Introversion, it can be observed that the original tasks contain less activities that align with this trait. After undergoing the E-I Task Process, the resulting modified tasks and the inferred E-I traits determined by Evaluator in the E-I Schedule Process are shown in

Table 3.

The modified tasks in

Table 3 were updated with more specific descriptions in order to preserve the behaviors of the original tasks. Evaluator also confirmed that it aligns with the agent’s assigned E-I traits by Extremely High Introversion.

Table 4 presents the evaluation results for both the original and modified tasks during the E-I Schedule Process.

Equations (1) and (2) were used to numerically confirm the experimental results. Equation (

1) quantifies the difference between the evaluation result for the original schedule and the evaluation result for the target E-I trait. Equation (

2) quantifies the difference between the evaluation result for the modified schedule and the evaluation result for the target E-I trait.

The following two equations quantify how well the task has been rescheduled. Equation (

1) uses the E-I trait of the original task and the original E-I traits to compute the score, where

refers to the E-I traits derived from the original task, and

refers to the original E-I traits. The part labeled Map denotes the numerical representation of each E-I trait. In this mapping, Extremely High Introversion (EHI) is assigned the value 1, and Extremely High Extroversion (EHE) is assigned the value 7. The E-I traits between these two extremes are assigned values from 2 to 6 in sequential order. MaxDiff refers to the maximum possible difference in Map values; in this study, it is set to 6 since the E-I trait is divided into 7 traits. However, this value can be adjusted if the E-I trait is further subdivided. Finally, the entire expression is multiplied by 100 to convert the result into a percentage. Based on the experimental results from

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4, if Map(

) is 4, Map(

) is 1, and MaxDiff is 6, the resulting Similarity Score is 50.0. Equation (

2) is similar to Equation (

1), except that

is replaced with

, which uses the E-I trait derived from the modified task instead of the original one. All other values remain the same, and in this case, Map(

) is 1, resulting in a Similarity Score of 100.0.

presents the Similarity Scores of the original and modified tasks for each E-I trait. The overall experimental results are summarized in

Table 5.

The results indicate that the original tasks tend to be classified primarily as Balanced, with a general bias toward introversion rather than extroversion. Using the proposed framework, it was confirmed that E-I traits can be reflected in tasks with a minimum accuracy of 70%.

Several key insights were drawn from the experimental results:

When the initial schedule is composed of overly neutral expressions or vocabulary, GPT-based evaluations tended to converge to labels such as Balanced or Somewhat Introverted. This is attributed to the nature of Schedule, which primarily consisted of quiet routines (e.g., making the bed, washing up), offering limited Extroverted behavioral indicators. Nevertheless, GPT was able to consistently modify each task into one of the seven traits based on predefined evaluation criteria.

During the E-I Task Process using few-shot prompts and example templates, the behavior of the original task was preserved, while its contextual or expressive style was altered. This resulted in an E-I Task Process that was more likely to receive labels such as High Extroversion or Extremely High Extroversion from GPT, thereby validating the effectiveness of the prompt design.

To mitigate the non-deterministic nature of GPT responses, the parameter was set relatively low. Each task was evaluated three times, and the final classification was determined based on majority voting or the median score. This strategy helped reduce erratic predictions and contributed to maintaining the system’s overall performance above average.

4.4. Comparison Experiment

The proposed framework shows the similar performance in other models. Llama3.1-405B instruction was used, and Qwen2-72B Base was used. The experimental method was performed by changing the model used to Llama3.1-405B and Qwen2-72B, although the method of the proposed framework is the same. The following table was the comparative experimental result.

Table 6 summarizes the results of applying the Score equation using the proposed framework, Llama3.1-405B, and Qwen2-72B, respectively. In the proposed framework, Llama3.1-405B showed similar results overall, and was more accurate than the framework proposed by the BA trait. In contrast, Qwen2-72B had lower inference performance than the proposed framework, showing an overall weaker appearance in E-I trait inference.

This confirms that our proposed framework was dependent on the generative and inference performance of the model and achieves similar results on models with similar performance to the proposed framework.