Surface-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotics in Wastewater: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

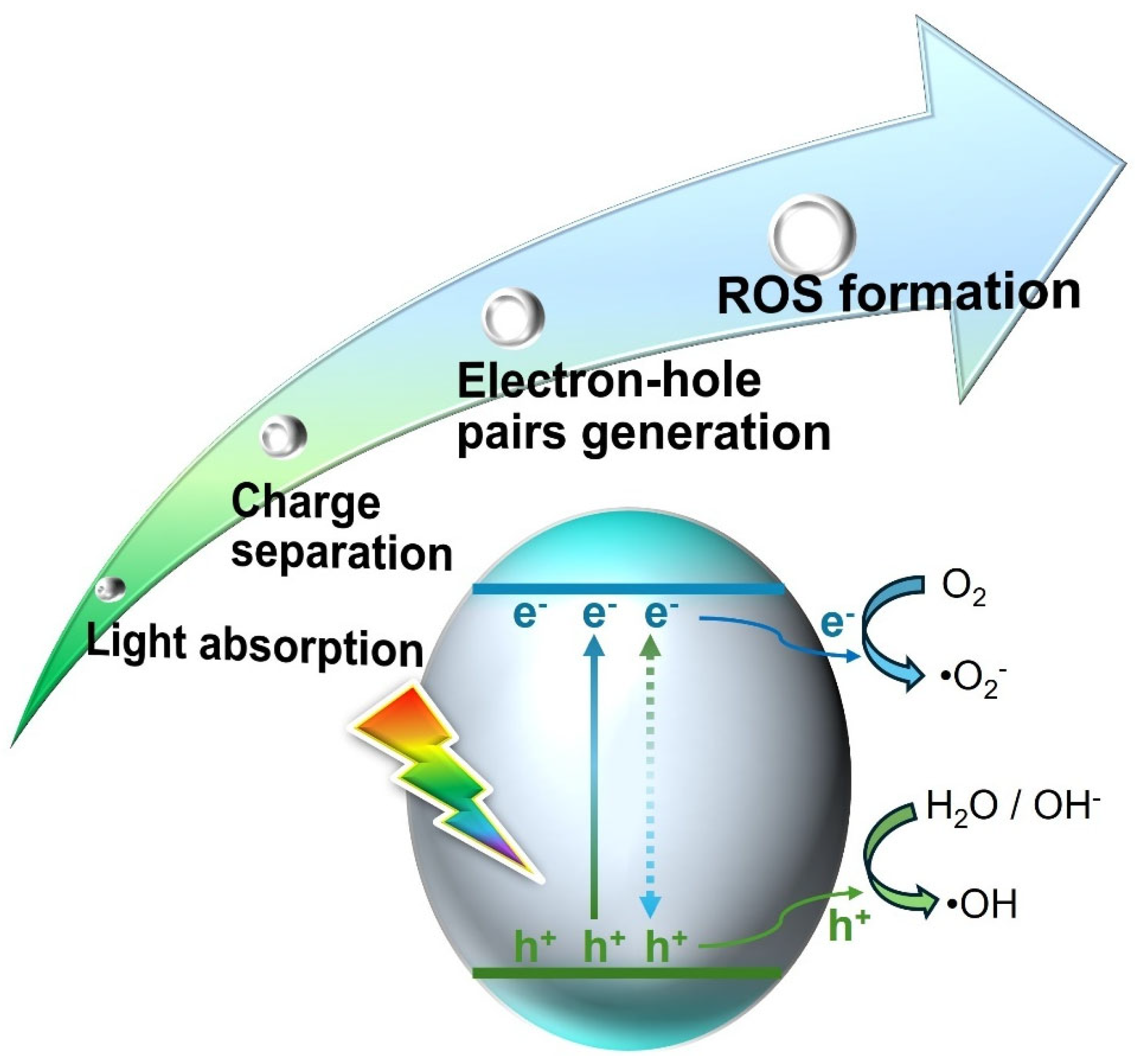

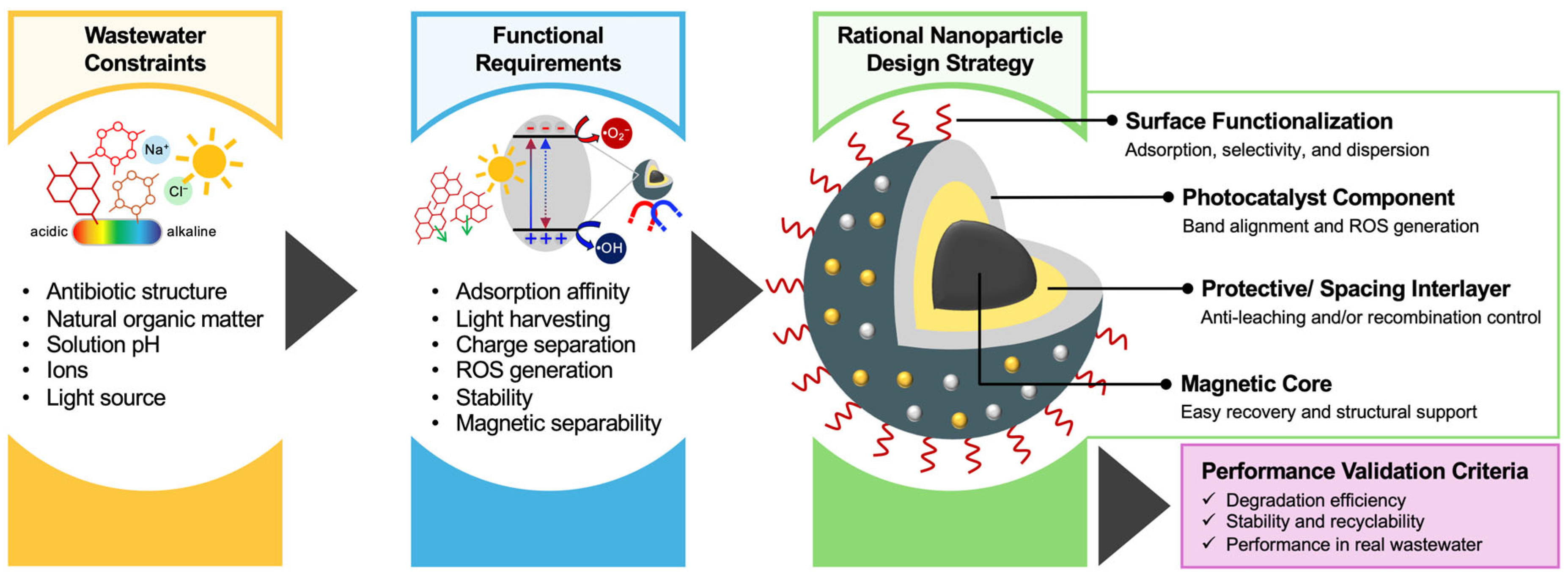

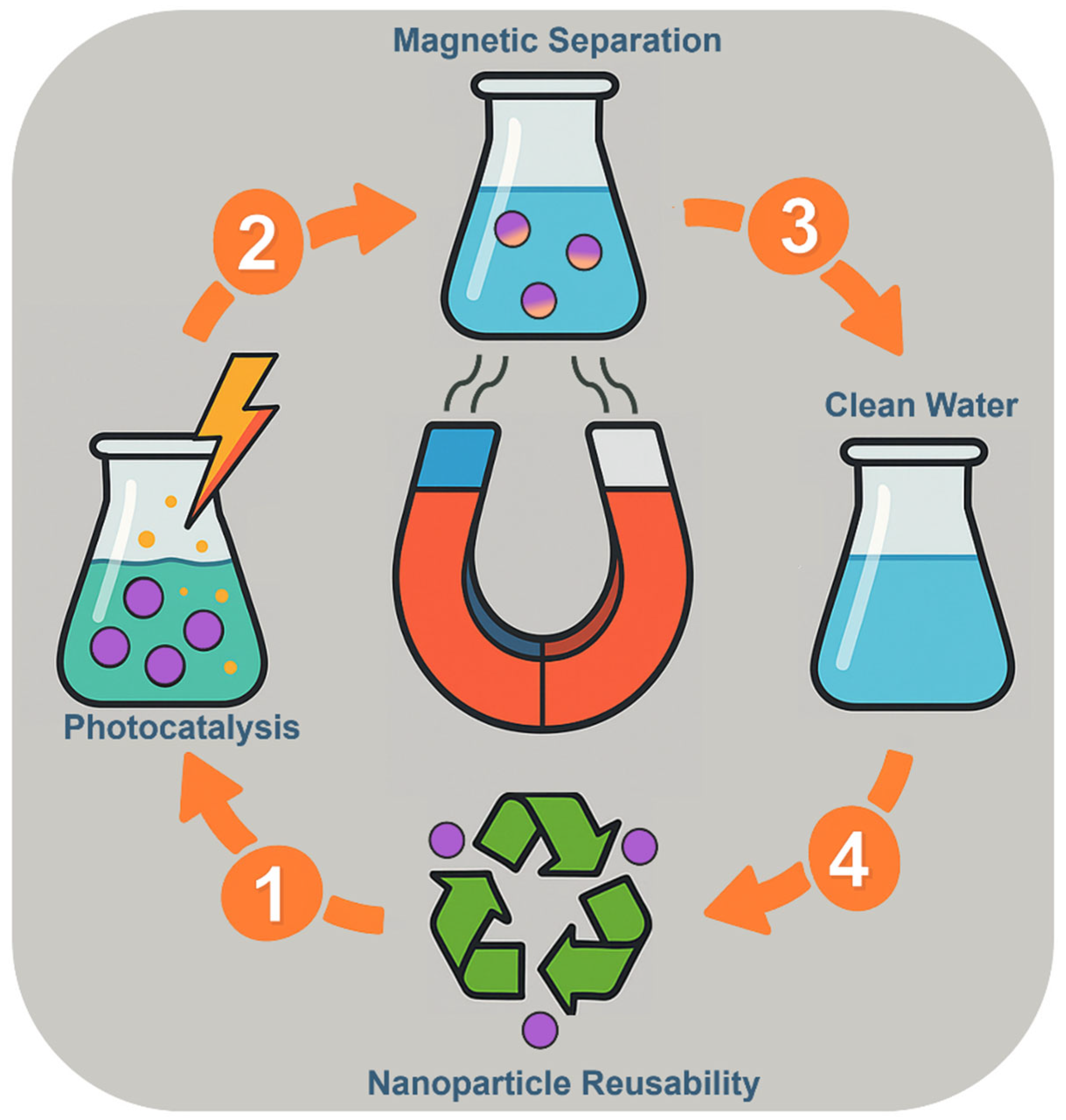

2. Magnetic Nanoparticle-Assisted Photocatalysis

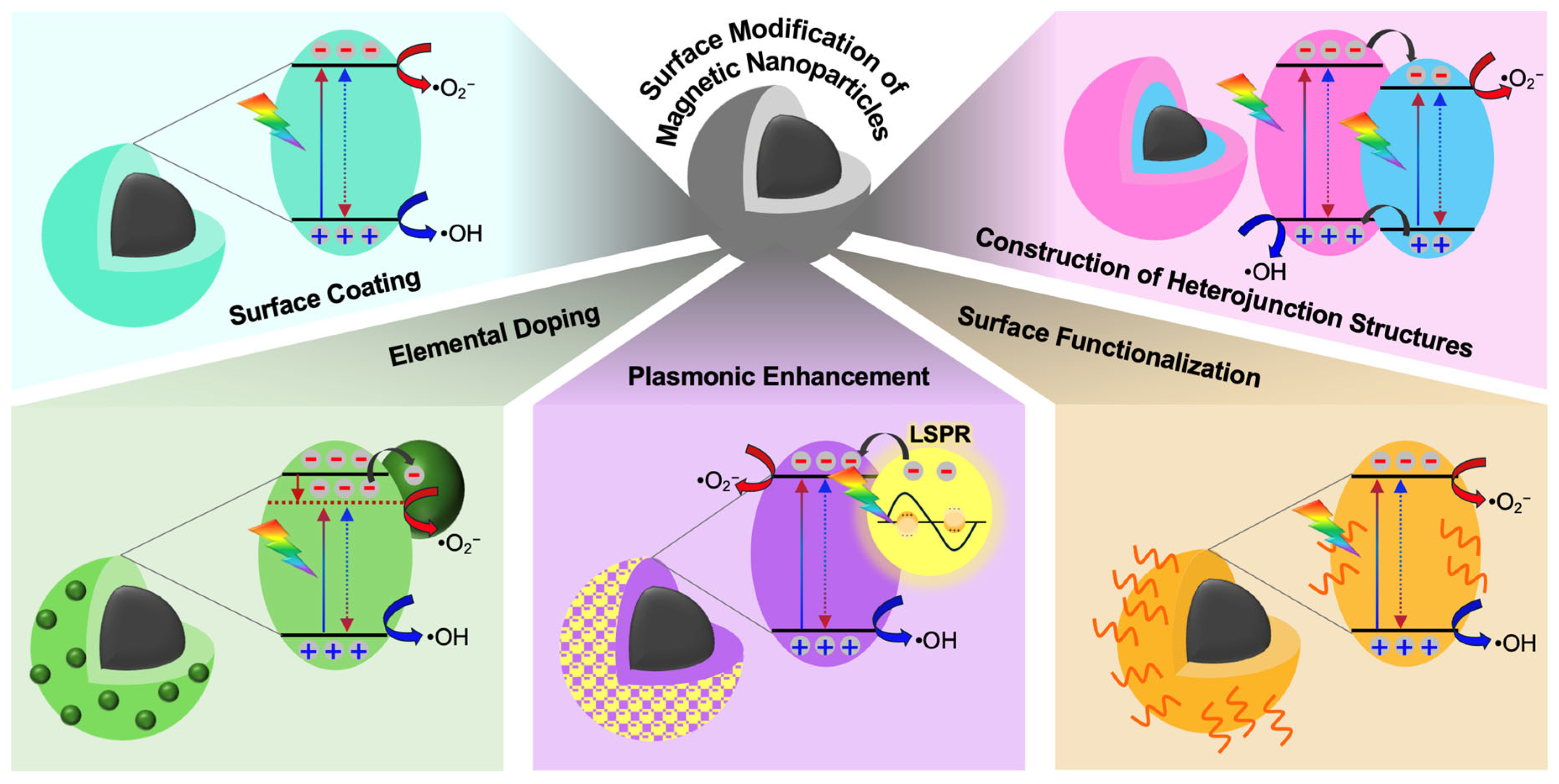

3. Surface-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles: A Potential Candidate for Photocatalysis

3.1. Surface Coating

3.2. Elemental Doping

3.3. Plasmonic Enhancement

3.4. Surface Functionalization

3.5. Construction of Heterojunction Structures

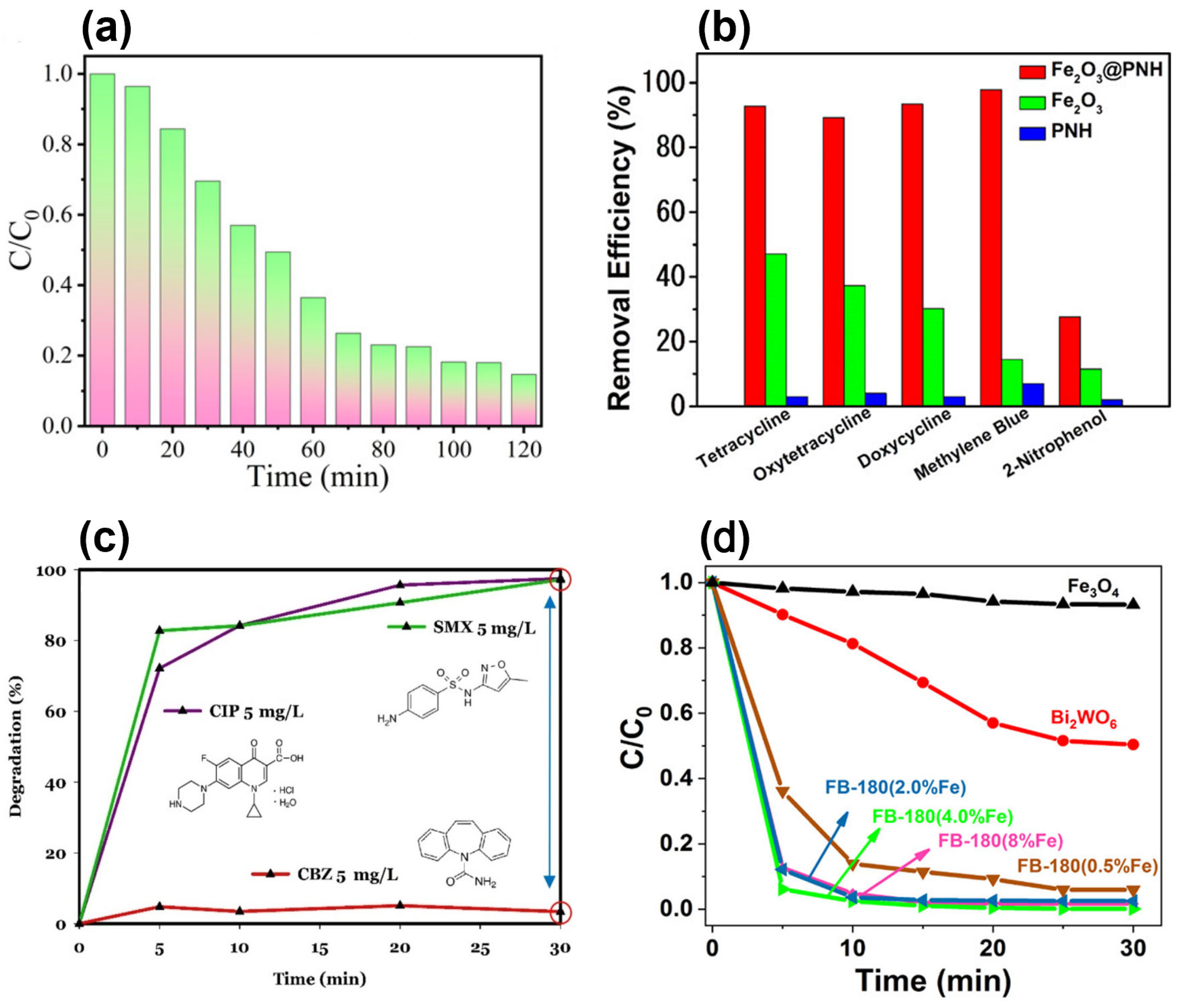

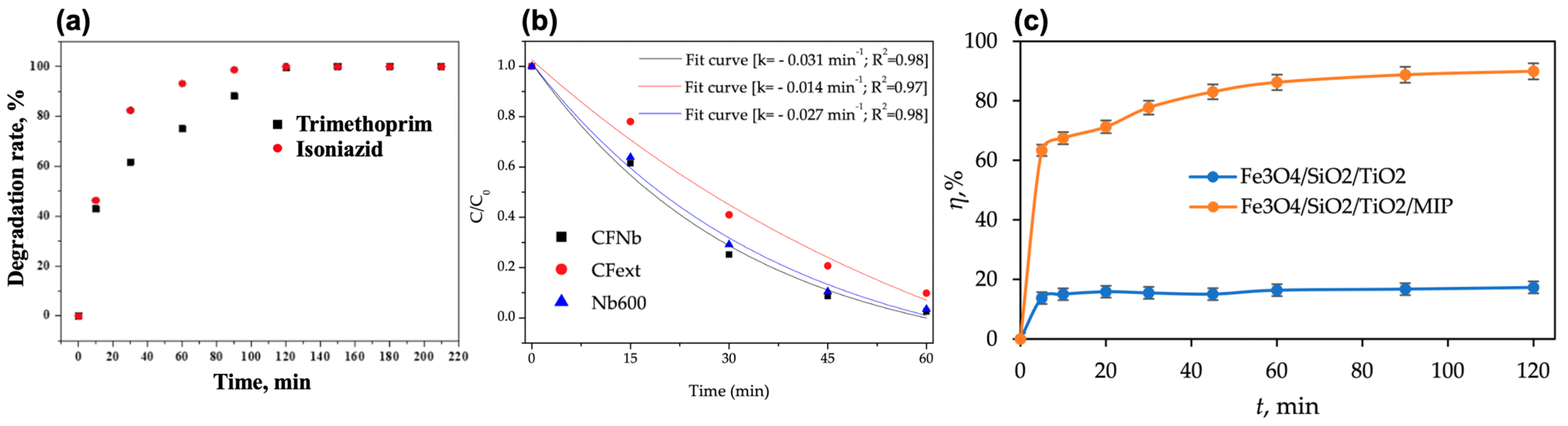

4. Applications of Surface-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles for Antibiotic Degradation

4.1. Most Common Antibiotics and Their Photodegradation by Magnetic Nanoparticle-Based Catalysts

| Antibiotic | Application | Antibiotic Amount | Magnetic Photocatalyst | Degradation Efficiency | Time (min) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetracycline (TC) | Broad-spectrum antibiotic for bacterial infections | 10 mg L−1 | MCP[Br] | 99% | 120 | [99] |

| 10 mg L−1 | TiO2/CoFe2O4 | 75.3% | 180 | [114] | ||

| 50 mg L−1 | BiOI–MEPCM | 85.3% | 120 | [115] | ||

| 60 mg L−1 | TFOC | 96% | 60 | [116] | ||

| 50 mg L−1 | M@B/B | 95% | 100 | [117] | ||

| 50 mg L−1 | Fe2O3@PNH | 90% | 120 | [100] | ||

| Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) | Antibacterial for UTIs and respiratory infections | 5 mg L−1 | ZnO/γ-Fe2O3/Bentonite | 97% | 30 | [120] |

| 100 μg L−1 | Fe3O4/ZnO | 100% | 240 | [21] | ||

| 150 μg L−1 | MCNT–TiO2 | 90% | 30 | [119] | ||

| Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | Fluoroquinolone for UTIs, gastrointestinal, and respiratory infections | 10 mg L−1 | Fe3O4/Bi2WO6 | 99.7% | 25 | [102] |

| 5 mg L−1 | ZnO/γ-Fe2O3/bentonite | 93% | 30 | [120] | ||

| 10 mg L−1 | γ-Fe2O3@ZnO | 92.5% | 60 | [104] | ||

| 10 mg L−1 | Fe3O4@MIL-100(Fe)@MIP | 95% | 1440 | [122] | ||

| 5 mg L−1 | Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 | 95% | 90 | [123] | ||

| Trimethoprim (TMP) | Co-administered with SMX for UTIs, bronchitis, and pneumonia | 200 mg L−1 | g-C3N4@TiO2@Fe3O4 | 100% | 120 | [125] |

| 5 mg L−1 | TiO2@Fe3O4@C-NFs | 100% | 150 | [126] | ||

| 100 mg L−1 | Fe3O4/ZnO | 36% | 240 | [21] | ||

| Acetaminophen (ACP)/Paracetamol (PA) | Analgesic and antipyretic for mild to moderate pain and fever | 10 ppm | ZnO/Fe3O4–GO/ZIF | 99.1% | 45 | [127] |

| 50 mg L−1 | TiO2/Fe2O3 | 100% | 90 | [128] | ||

| 25 mg L−1 | Fe3O4@SiO2/N-CXTi | 99.20% | 180 | [93] | ||

| 20 mg L−1 | CoFe2O4@Nb2O5 | 97.5% | 60 | [129] | ||

| Ibuprofen (IBP) | NSAID for pain, inflammation, fever, arthritis, and headaches | 10 mg L−1 | POM–γ-Fe2O3/SrCO3 | Not reported | 120 | [98] |

| 2 mg L−1 | N-TiO2@SiO2@Fe3O4 | 94% | 300 | [131] | ||

| 15mg L−1 | Fe3O4@SiO2@TiO2 | 60% | 90 | [123] | ||

| 2 mg L−1 | BiOBr/Fe3O4@SiO2 | 100% | 360 | [132] | ||

| Carbamazepine (CBZ) | Anticonvulsant for epilepsy, neuropathic pain, and bipolar disorder | 10 mg L−1 | MCNT–TiO2 | 60% | 120 | [119] |

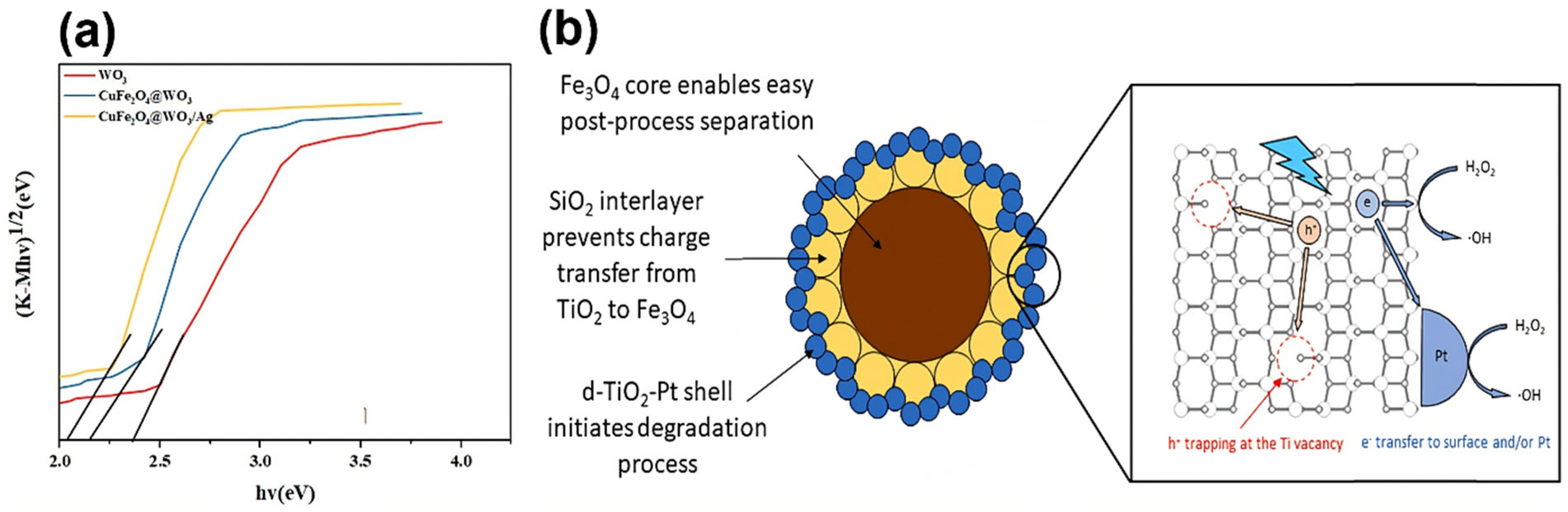

| 14 mg L−1 | Fe3O4@SiO2/d-TiO2/Pt | 96% | 120 | [96] | ||

| 10 mg L−1 | Ag/AgBr/ZnFe2O4 | 22.7% | 240 | [95] | ||

| Diclofenac (DCF) | NSAID for pain and inflammation, used for arthritis, migraines, and muscular pain | 10 mg L−1 | TiO2@ZnFe2O4/Pd | 84.8% | 120 | [92] |

| 10 mg L−1 | Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2/MIP | 80% | 120 | [88] | ||

| 5 × 105 M | Fe3O4@SiO2-RB | 100% | 180 | [135] | ||

| 10 mg L−1 | Fe3O4/Bi2S3/BiOBr | 93.80% | 40 | [134] |

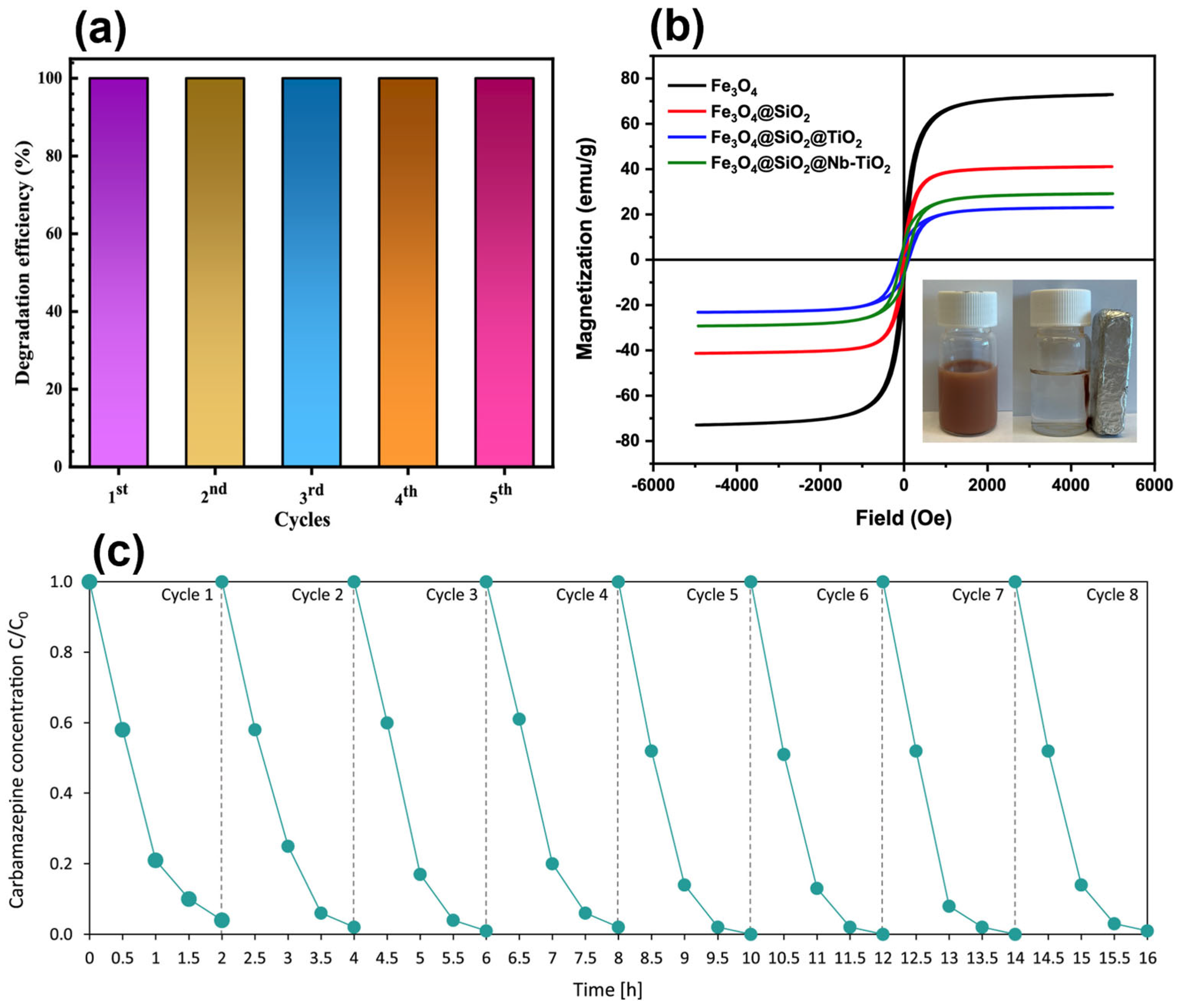

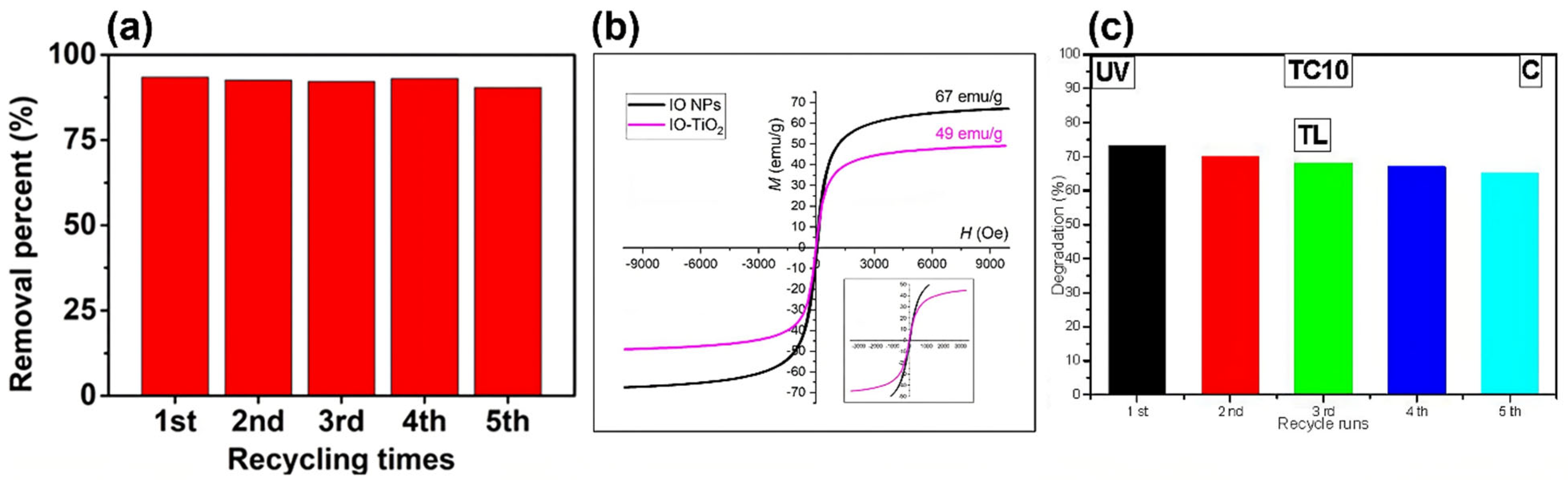

4.2. Recovery, Reusability, and Long-Term Performance of Magnetic Nanoparticles

| MNP Core | Photocatalyst | Contaminant | Time (min) | Removal Efficiency (%) | Reusability Cycles | MS (emu g−1) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4 | BiOBr/Fe3O4@SiO2 | IBP | 60 | 80–60 | 5 | ∼40 | [132] |

| Fe3O4/AC–CTAB–BiOCl | OFL | 60 | 100 | 5 | 2.2 | [101] | |

| TiO2/SiO2/Fe3O4 | ACP | 300 | - | 4 | 38.9 | [144] | |

| Fe3O4@SiO2@Nb-TiO2 | CIP | 94–77 | 5 | 22 | [90] | ||

| Fe3O4@SiO2@TiO2/rGO | MNZ | 60 | 94–63 | 4 | 14.8 | [136] | |

| Fe3O4@SiO2/d-TiO2/Pt | CBZ | 120 | 96 | 8 | - | [96] | |

| Fe3O4/ZnO | SMX ROX ERY TMP | 240 | 100 | 8 | 4.3 | [21] | |

| 94 | |||||||

| 66 | |||||||

| 36 | |||||||

| Fe2O3 | POM–γ-Fe2O3/SrCO3 | IBP | 120 | - | 4 | 11 | [98] |

| Fe2O3@PNH | TC | 60 | 90 | 5 | - | [100] | |

| γ-Fe2O3@ZnO | CIP | 60 | 92.5 | 6 | 5.2 | [104] | |

| ZnO/Fe2O3–GO/ZIF | SMZ | 60 | 97.7 | 10 | 21.2 | [127] | |

| TiO2/Fe2O3 | PA | 180 | 98–57.5 | 5 | 20.8 | [128] | |

| γ-Fe2O3–TiO2 | CIP | 150 | 70 | 4 | 49 | [146] | |

| XFe2O4 | MnFe2O4@Bi24O31Br10/BiO7I | LVX | 100 | 93.2–70.2 | 5 | 32.40 | [117] |

| TC | 95–71.7 | ||||||

| TCS | 87.8–68.1 | ||||||

| CuFe2O4@WO3/Ag | TAM GEM | 150 | 83.15–72.64 81.47–68.25 | 5 | 29.49 | [94] | |

| TiO2@ZnFe2O4/Pd | DCF | 120 | 86.1–71.4 | 5 | 27.28 | [92] | |

| ZnFe2O4@TiO2/Cu | NPX | 120 | 80.7–72.3 | 8 | 26.45 | [137] | |

| TiO2/CoFe2O4 | TC | 180 | 75–65 | 5 | 8.4 | [114] | |

| CoFe2O4@CuS | PCN | 120 | 70.7–58.6 | 5 | 7.76 | [140] |

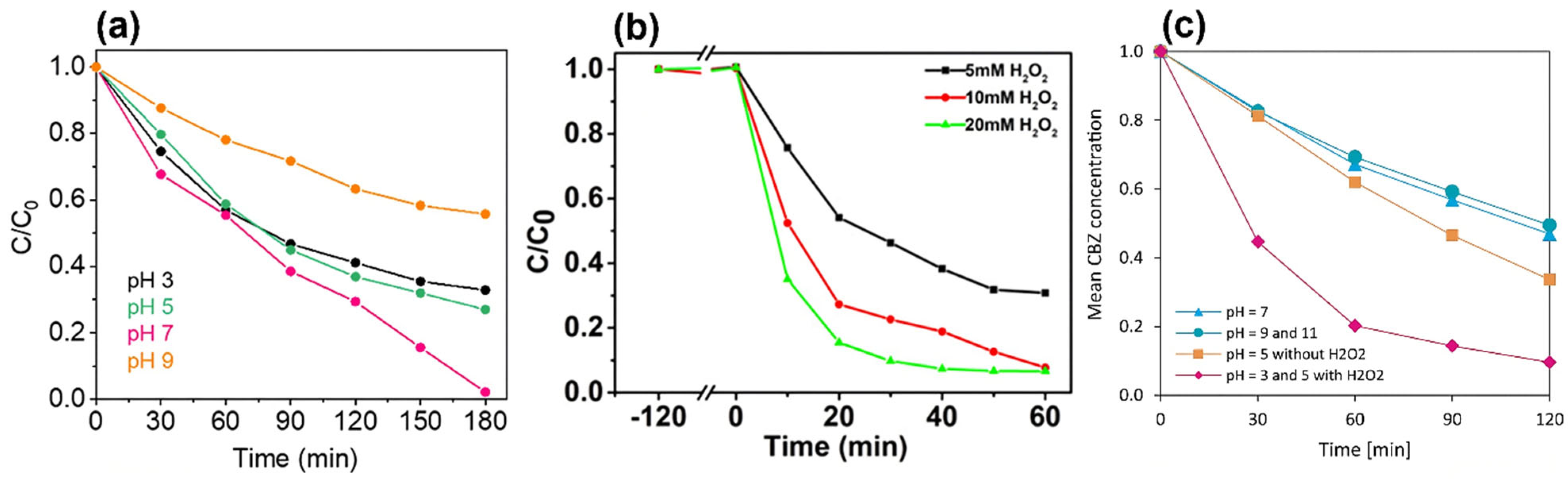

4.3. Influencing Factors in Photocatalytic Reactions

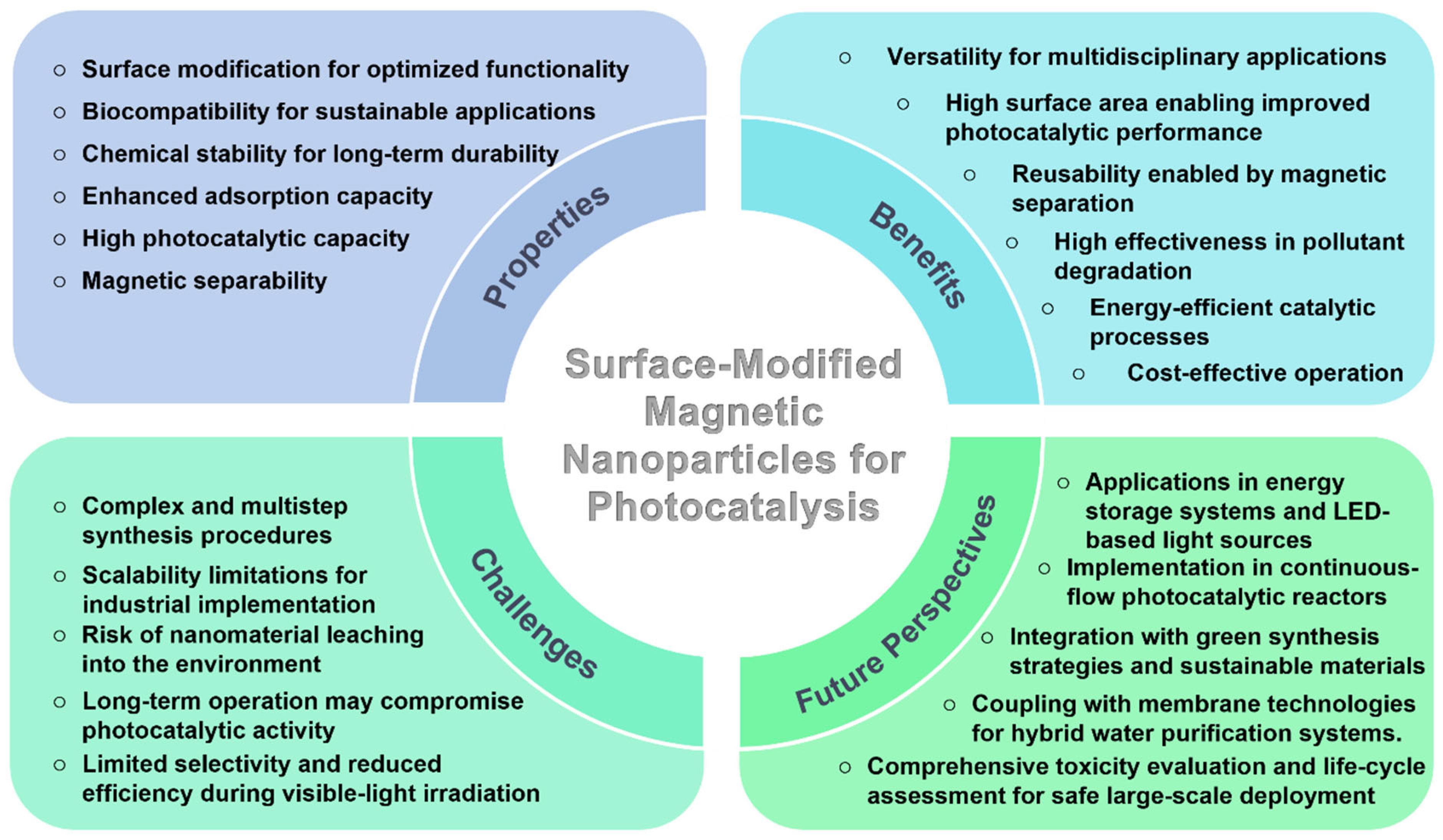

5. Challenges and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cosgrove, W.J.; Loucks, D.P. Water Management: Current and Future Challenges and Research Directions. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 4823–4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strokal, M.; Bai, Z.; Franssen, W.; Hofstra, N.; Koelmans, A.A.; Ludwig, F.; Ma, L.; van Puijenbroek, P.; Spanier, J.E.; Vermeulen, L.C.; et al. Urbanization: An Increasing Source of Multiple Pollutants to Rivers in the 21st Century. npj Urban Sustain. 2021, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN World Water Development Report 2024. UN-Water. Available online: https://www.unwater.org/publications/un-world-water-development-report-2024 (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Water and Climate Change. UN-Water. Available online: https://www.unwater.org/water-facts/water-and-climate-change (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- United Nations Environment Programme. Food Security and Water Quality. Available online: https://www.unep.org/interactives/wwqa/technical-highlights/food-security-and-water-quality (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Khalid, S.; Shahid, M.; Natasha; Bibi, I.; Sarwar, T.; Shah, A.H.; Niazi, N.K. A Review of Environmental Contamination and Health Risk Assessment of Wastewater Use for Crop Irrigation with a Focus on Low and High-Income Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Contaminants of Emerging Concern including Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/wqc/contaminants-emerging-concern-including-pharmaceuticals-and-personal-care-products (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Okoye, C.O.; Nyaruaba, R.; Ita, R.E.; Okon, S.U.; Addey, C.I.; Ebido, C.C.; Opabunmi, A.O.; Okeke, E.S.; Chukwudozie, K.I. Antibiotic Resistance in the Aquatic Environment: Analytical Techniques and Interactive Impact of Emerging Contaminants. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 96, 103995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.P.; Almeida, C.M.R.; Salgado, M.A.; Carvalho, M.F.; Mucha, A.P. Pharmaceutical Compounds in Aquatic Environments—Occurrence, Fate and Bioremediation Prospective. Toxics 2021, 9, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.C. Occurrence, Sources, and Fate of Pharmaceuticals in Aquatic Environment and Soil. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 187, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, A.J.; Chipeta, M.G.; Haines-Woodhouse, G.; Kumaran, E.P.A.; Hamadani, B.H.K.; Zaraa, S.; Henry, N.J.; Deshpande, A.; Reiner, R.C.; Day, N.P.J.; et al. Global Antibiotic Consumption and Usage in Humans, 2000–18: A Spatial Modelling Study. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e893–e904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Pharmaceuticals Industry Analysis and Trends 2023. NAVADHI Market Research. Available online: https://www.navadhi.com/publications/global-pharmaceuticals-industry-analysis-and-trends-2023 (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Wang, H.; Wang, N.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Q.; Fang, H.; Fu, C.; Tang, C.; Jiang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Antibiotics in Drinking Water in Shanghai and Their Contribution to Antibiotic Exposure of School Children. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 2692–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansson, E.; Fick, J.; Janzon, A.; Grabic, R.; Rutgersson, C.; Weijdegard, B.; Soderstrom, H.; Larsson, D.G.J. Pyrosequencing of Antibiotic-Contaminated River Sediments Reveals High Levels of Resistance and Gene Transfer Elements. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radjenović, J.; Petrović, M.; Barceló, D. Fate and Distribution of Pharmaceuticals in Wastewater and Sewage Sludge of the Conventional Activated Sludge (CAS) and Advanced Membrane Bioreactor (MBR) Treatment. Water Res. 2009, 43, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Ram, B.; Honda, R.; Poopipattana, C.; Canh, V.D.; Chaminda, T.; Furumai, H. Concurrence of Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria (ARB), Viruses, Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) in Ambient Waters of Guwahati, India: Urban Vulnerability and Resilience Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 693, 133640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, J.L.; Boxall, A.B.A.; Kolpin, D.W.; Leung, K.M.Y.; Lai, R.W.S.; Galbán-Malagón, C.; Adell, A.D.; Mondon, J.; Metian, M.; Marchant, R.A.; et al. Pharmaceutical Pollution of the World’s Rivers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2113947119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhagat, C.; Kumar, M.; Tyagi, V.K.; Mohapatra, P.K. Proclivities for Prevalence and Treatment of Antibiotics in the Ambient Water: A Review. npj Clean. Water 2020, 3, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Münzel, T.; Hahad, O.; Daiber, A.; Landrigan, P.J. Soil and Water Pollution and Human Health: What Should Cardiologists Worry About? Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 119, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, I.; Lone, F.A.; Bhat, R.A.; Mir, S.A.; Dar, Z.A.; Dar, S.A. Concerns and Threats of Contamination on Aquatic Ecosystems. Bioremediat. Biotechnol. 2020, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, L.; Gamallo, M.; González-Gómez, M.A.; Vázquez-Vázquez, C.; Rivas, J.; Pintado, M.; Moreira, M.T. Insight into Antibiotics Removal: Exploring the Photocatalytic Performance of a Fe3O4/ZnO Nanocomposite in a Novel Magnetic Sequential Batch Reactor. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 237, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Environmental Protection Agency. The Impact of Pharmaceuticals Released to the Environment. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/household-medication-disposal/impact-pharmaceuticals-released-environment (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Center for Disease Control. Antimicrobial Resistance in the Environment and the Food Supply: Causes and How It Spreads. Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/causes/environmental-food.html (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Kraemer, S.A.; Ramachandran, A.; Perron, G.G. Antibiotic Pollution in the Environment: From Microbial Ecology to Public Policy. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ten Health Issues WHO Will Tackle this Year 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- World Health Organization. 10 Global Health Issues to Track in 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/10-global-health-issues-to-track-in-2021 (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Shad, M.F.; Juby, G.J.G.; Delagah, S.; Sharbatmaleki, M. Evaluating Occurrence of Contaminants of Emerging Concerns in MF/RO Treatment of Primary Effluent for Water Reuse—Pilot Study. J. Water Reuse Desalination 2019, 9, 350–371. [Google Scholar]

- Alazaiza, M.Y.D.; Albahnasawi, A.; Ali, G.A.M.; Bashir, M.J.K.; Nassani, D.E.; Al Maskari, T.; Amr, S.S.A.; Abujazar, M.S.S. Application of Natural Coagulants for Pharmaceutical Removal from Water and Wastewater: A Review. Water 2022, 14, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayagam, V.; Murugan, S.; Kumaresan, R.; Narayanan, M.; Sillanpää, M.; Viet N Vo, D.; Kushwaha, O.S.; Jenis, P.; Potdar, P.; Gadiya, S. Sustainable Adsorbents for the Removal of Pharmaceuticals from Wastewater: A Review. Chemosphere 2022, 300, 134597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.J.; Chakraborty, A.; Sehgal, R. A Systematic Review of Industrial Wastewater Management: Evaluating Challenges and Enablers. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 348, 119230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crini, G.; Lichtfouse, E. Advantages and Disadvantages of Techniques Used for Wastewater Treatment. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Álvarez, D.T.; Brown, J.; Elgohary, E.A.; Mohamed, Y.M.A.; Nazer, H.A.E.; Davies, P.; Stafford, J. Challenges Surrounding Nanosheets and Their Application to Solar-Driven Photocatalytic Water Treatment. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 4103–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belete, B.; Desye, B.; Ambelu, A.; Yenew, C. Micropollutant Removal Efficiency of Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plants: A Systematic Review. Environ. Health Insights 2023, 17, 11786302231195158. [Google Scholar]

- Eggen, R.I.L.; Hollender, J.; Joss, A.; Schärer, M.; Stamm, C. Reducing the Discharge of Micropollutants in the Aquatic Environment: The Benefits of Upgrading Wastewater Treatment Plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 7683–7689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janani, R.; Gurunathan, B.; K, S.; Varjani, S.; Ngo, H.H.; Gnansounou, E. Advancements in Heavy Metals Removal from Effluents Employing Nano-Adsorbents: Way towards Cleaner Production. Environ. Res. 2022, 203, 111815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, K.; Patel, A.S.; Pardhi, V.P.; Flora, S.J.S. Nanotechnology in Wastewater Management: A New Paradigm Towards Wastewater Treatment. Molecules 2021, 26, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Chakraborty, J.; Chatterjee, S.; Kumar, H. Prospects of Biosynthesized Nanomaterials for the Remediation of Organic and Inorganic Environmental Contaminants. Environ. Sci. Nano 2018, 5, 2784–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Brame, J.; Li, Q.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Nanotechnology for a Safe and Sustainable Water Supply: Enabling Integrated Water Treatment and Reuse. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 834–843. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, G.; Han, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, J.; Meng, X.; Li, Z. Recent Advances of Photocatalytic Application in Water Treatment: A Review. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nuaim, M.A.; Alwasiti, A.A.; Shnain, Z.Y. The Photocatalytic Process in the Treatment of Polluted Water. Chem. Pap. 2023, 77, 677–701. [Google Scholar]

- Djurišić, A.B.; He, Y.; Ng, A.M.C. Visible-Light Photocatalysts: Prospects and Challenges. APL Mater. 2020, 8, 030903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Ji, H.; Yu, P.; Niu, J.; Farooq, M.U.; Akram, M.W.; Udego, I.O.; Li, H.; Niu, X. Surface Modification of Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, B.; Obaidat, I.M.; Albiss, B.A.; Haik, Y. Magnetic Nanoparticles: Surface Effects and Properties Related to Biomedicine Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 21266–21305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Yeap, S.P.; Che, H.X.; Low, S.C. Characterization of Magnetic Nanoparticle by Dynamic Light Scattering. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, K.E.; Dionysiou, D.D. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water Treatment. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 2112–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muruganandham, M.; Suri, R.P.S.; Jafari, S.; Sillanpää, M.; Lee, G.-J.; Wu, J.J.; Swaminathan, M. Recent Developments in Homogeneous Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water and Wastewater Treatment. Int. J. Photoenergy 2014, 2014, 821674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Wan, Y.; Long, Y.; Cai, Z. Recent Advances and Applications of Semiconductor Photocatalytic Technology. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, J.O.; Ajiboye, T.; Onwudiwe, D.C. Mineralization of Antibiotics in Wastewater Via Photocatalysis. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, A.; Mert, B.K.; Özengin, N.; Sivrioğlu, Ö.; Yonar, T. Treatment of Antibiotics in Wastewater Using Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs). In Physico-Chemical Wastewater Treatment and Resource Recovery; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Makuła, P.; Pacia, M.; Macyk, W. How To Correctly Determine the Band Gap Energy of Modified Semiconductor Photocatalysts Based on UV–Vis Spectra. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 6814–6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Hua, X.; Guo, Z.; Dong, D. Efficient Generation of Singlet Oxygen for Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotics: Synergistic Effects of Fe Spin State Reduction and Energy Transfer. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2024, 358, 124406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Liu, Q.; Yang, P.; Jiang, G.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y. Singlet-Oxygen-Driven CeO2 Quantum Dots/Hollow Spherical g-C3N4 S-Scheme Heterojunction Photocatalyst for the Degradation of Tetracycline. Langmuir 2025, 41, 28592–28605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, Y.; He, S.; Wu, S.; Yang, C. Singlet Oxygen: Properties, Generation, Detection, and Environmental Applications. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461, 132538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Niu, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Sun, T.; Shi, D.; Zhao, B.; Yan, G.; Huo, M.; et al. Efficient Singlet Oxygen Nanogenerator with Low-Spin Iron for Selective Contaminant Decontamination. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 476, 146683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, A.M.; Dziubla, T.D.; Hilt, J.Z. Recent Advances on Iron Oxide Magnetic Nanoparticles as Sorbents of Organic Pollutants in Water and Wastewater Treatment. Rev. Environ. Health 2017, 32, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbarzadeh, A.; Samiei, M.; Davaran, S. Magnetic Nanoparticles: Preparation, Physical Properties, and Applications in Biomedicine. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Zafar, H.; Zia, M.; ul Haq, I.; Phull, A.R.; Ali, J.S.; Hussain, A. Synthesis, Characterization, Applications, and Challenges of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanotechnol. Sci. Appl. 2016, 9, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Sharma, K.; Hasija, V.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, S.; Raizada, P.; Singh, M.; Saini, A.K.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A.; Thakur, V.K. Systematic Review on Applicability of Magnetic Iron Oxides–Integrated Photocatalysts for Degradation of Organic Pollutants in Water. Mater. Today Chem. 2019, 14, 100186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.D.; Tran, H.-V.; Xu, S.; Lee, T.R. Fe3O4 Nanoparticles: Structures, Synthesis, Magnetic Properties, Surface Functionalization, and Emerging Applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modabberasl, A.; Pirhoushyaran, T.; Esmaeili-Faraj, S.H. Synthesis of CoFe2O4 Magnetic Nanoparticles for Application in Photocatalytic Removal of Azithromycin from Wastewater. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusegun, S.J.; Larrea, G.; Osial, M.; Jackowska, K.; Krysinski, P. Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotics by Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Tetracycline Case. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.D.; Hoijang, S.; Yarinia, R.; Ariza Gonzalez, M.; Mandal, S.; Tran, Q.M.; Chinwangso, P.; Lee, T.R. Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Advances in Synthesis, Mechanistic Understanding, and Magnetic Property Optimization for Improved Biomedical Performance. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolhatkar, A.G.; Jamison, A.C.; Litvinov, D.; Willson, R.C.; Lee, T.R. Tuning the Magnetic Properties of Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 15977–16009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, N.; Lee, J.-S.; Liman, R.A.D.; Ruallo, J.M.S.; Villaflores, O.B.; Ger, T.-R.; Hsiao, C.-D. Potential Toxicity of Iron Oxide Magnetic Nanoparticles: A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Park, Y.; Kim, W.; Choi, W. Surface Modification of TiO2 Photocatalyst for Environmental Applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, J.; Lu, C.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Varma, R.S. Selectivity Enhancement in Heterogeneous Photocatalytic Transformations. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 1445–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Li, X.; Liu, W.; Fang, Y.; Xie, J.; Xu, Y. Photocatalysis Fundamentals and Surface Modification of TiO2 Nanomaterials. Chin. J. Catal. 2015, 36, 2049–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etacheri, V.; Di Valentin, C.; Schneider, J.; Bahnemann, D.; Pillai, S.C. Visible-Light Activation of TiO2 Photocatalysts: Advances in Theory and Experiments. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2015, 25, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, K.; Yu, J. Chapter 8—Modification of ZnO-Based Photocatalysts for Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. In Interface Science and Technology; Yu, J., Jaroniec, M., Jiang, C., Eds.; Surface Science of Photocatalysis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 31, pp. 265–284. [Google Scholar]

- Raizada, P.; Soni, V.; Kumar, A.; Singh, P.; Parwaz Khan, A.A.; Asiri, A.M.; Thakur, V.K.; Nguyen, V.-H. Surface Defect Engineering of Metal Oxides Photocatalyst for Energy Application and Water Treatment. J. Mater. 2021, 7, 388–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Sierra, J.C.; Hernández-Ramírez, A.; Hinojosa-Reyes, L.; Guzmán-Mar, J.L. A Review on the Development of Visible Light-Responsive WO3-Based Photocatalysts for Environmental Applications. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2021, 5, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandilya, P.; Sambyal, S.; Sharma, R.; Mandyal, P.; Fang, B. Properties, Optimized Morphologies, and Advanced Strategies for Photocatalytic Applications of WO3 Based Photocatalysts. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 428, 128218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehtisham Khan, M. State-of-the-Art Developments in Carbon-Based Metal Nanocomposites as a Catalyst: Photocatalysis. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 1887–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Svoboda, L.; Němečková, Z.; Sgarzi, M.; Henych, J.; Licciardello, N.; Cuniberti, G. Enhanced Visible-Light Photodegradation of Fluoroquinolone-Based Antibiotics and E. Coli Growth Inhibition Using Ag–TiO2 Nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 13980–13991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Niu, J.; Zhao, J.; Wei, Y.; Yao, B. Photocatalytic Degradation of Ciprofloxacin Using Zn-Doped Cu2O Particles: Analysis of Degradation Pathways and Intermediates. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 374, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Hu, H.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.H. Visible Light Photocatalytic Degradation of Tetracycline over TiO2. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 382, 122842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibhadon, A.O.; Fitzpatrick, P. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis: Recent Advances and Applications. Catalysts 2013, 3, 189–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.; Yu, J.; Jaroniec, M.; Wageh, S.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A. Heterojunction Photocatalysts. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1601694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, C.; Tang, X.; Wang, H.; Su, Q.; Zuo, C.; Tang, X.; Wang, H.; Su, Q. A Review of the Effect of Defect Modulation on the Photocatalytic Reduction Performance of Carbon Dioxide. Molecules 2024, 29, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, A.; Rabiee, N.; Ahmadi, S.; Baneshi, M.; Khatami, M.; Iravani, S.; Varma, R.S. Core–Shell Nanophotocatalysts: Review of Materials and Applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Matsuoka, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Zhang, J.; Horiuchi, Y.; Anpo, M.; Bahnemann, D.W. Understanding TiO2 Photocatalysis: Mechanisms and Materials. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9919–9986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, L.; Yang, H.G.; Cheng, H.-M.; Lu, G.Q. Titania-Based Photocatalysts—Crystal Growth, Doping and Heterostructuring. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Miao, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, B.; Du, Y.; Han, X.; Sun, J.; Xu, P. Recent Advances in Plasmonic Nanostructures for Enhanced Photocatalysis and Electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2000086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Wang, H.-J.; Lin, J.-S.; Yang, J.-L.; Zhang, F.-L.; Lin, X.-M.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Jin, S.; Li, J.-F. Plasmonic Photocatalysis: Mechanism, Applications and Perspectives. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 2023, 42, 100066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Yu, S.; Meng, B.; Wang, X.; Yang, C.; Shi, C.; Ding, J.; Liang, X.; Yu, S.; Meng, B.; et al. Advanced TiO2-Based Photoelectrocatalysis: Material Modifications, Charge Dynamics, and Environmental–Energy Applications. Catalysts 2025, 15, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabelica, I.; Ćurković, L.; Mandić, V.; Panžić, I.; Ljubas, D.; Zadro, K. Rapid Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Core-2-Layer-Shell Nanocomposite for Photocatalytic Degradation of Ciprofloxacin. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabelica, I.; Radovanović-Perić, F.; Matijašić, G.; Tolić Čop, K.; Ćurković, L.; Mutavdžić Pavlović, D. Synergistic Removal of Diclofenac via Adsorption and Photocatalysis Using a Molecularly Imprinted Core–Shell Photocatalyst. Materials 2025, 18, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrotek, E.; Dudziak, S.; Malinowska, I.; Pelczarski, D.; Ryżyńska, Z.; Zielińska-Jurek, A. Improved Degradation of Etodolac in the Presence of Core-Shell ZnFe2O3/SiO2/TiO2 Magnetic Photocatalyst. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 724, 138167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza Gonzalez, M.; Nguyen, M.D.; Tran, Q.M.; Hoijang, S.; Chinwangso, P.; Robles Hernandez, F.C.; Rodrigues, D.F.; Lee, T.R. Magnetic Fe3O4 Nanocubes Coated with Silica and Nb-Doped TiO2 for Recyclable Photocatalytic Degradation of Ciprofloxacin. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 22540–22552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlyustova, A.; Sirotkin, N.; Kusova, T.; Kraev, A.; Titov, V.; Agafonov, A. Doped TiO2: The Effect of Doping Elements on Photocatalytic Activity. Mater. Adv. 2020, 1, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpour, N.; Sayadi, M.H.; Sobhani, S.; Hajiani, M. Photocatalytic Degradation of Model Pharmaceutical Pollutant by Novel Magnetic TiO2@ZnFe2O4/Pd Nanocomposite with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity and Stability under Solar Light Irradiation. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 110964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Carmo Batista, W.V.F.; da Cunha, R.; dos Santos, A.C.; dos Reis, P.M.; Furtado, C.A.; Silva, M.C.; de Fátima Gorgulho, H. Synthesis of a Reusable Magnetic Photocatalyst Based on Carbon Xerogel/TiO2 Composites and Its Application on Acetaminophen Degradation. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 34395–34404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayadi, M.H.; Ahmadpour, N.; Homaeigohar, S. Photocatalytic and Antibacterial Properties of Ag-CuFe2O4@WO3 Magnetic Nanocomposite. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yentür, G.; Dükkancı, M. Fabrication of Magnetically Separable Plasmonic Composite Photocatalyst of Ag/AgBr/ZnFe2O4 for Visible Light Photocatalytic Oxidation of Carbamazepine. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 510, 145374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudziak, S.; Bielan, Z.; Kubica, P.; Zielińska-Jurek, A. Optimization of Carbamazepine Photodegradation on Defective TiO2-Based Magnetic Photocatalyst. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Shah, T.; Ullah, R.; Zhou, P.; Guo, M.; Ovais, M.; Tan, Z.; Rui, Y. Review on Recent Progress in Magnetic Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Diverse Applications. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 629054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastami, T.R.; Ahmadpour, A. Preparation of Magnetic Photocatalyst Nanohybrid Decorated by Polyoxometalate for the Degradation of a Pharmaceutical Pollutant under Solar Light. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 8849–8860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayarkhuu, B.; Yang, C.; Wang, W.; Zhang, K.A.I.; Byun, J. Magnetic Conjugated Polymer Nanoparticles with Tunable Wettability for Versatile Photocatalysis under Visible Light. ACS Mater. Lett. 2020, 2, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, J.; Zhou, F.; Zhou, S.; Wu, J.; Chen, D.; Xu, Q.; Lu, J. Polymer-Coated Fe2O3 Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Materials and Antibiotics in Water. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 9200–9208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piankaew, V.; Deemak, S.; Nonthing, S.; Panchakeaw, A.; Wannakan, K.; Nanan, S. Complete Detoxification of the Ofloxacin Antibiotic by Magnetically Separable Fe3O4/AC/BiOCl Photocatalysts. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 48858–48874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Song, D.; Jia, T.; Sun, W.; Wang, D.; Wang, L.; Guo, J.; Jin, L.; Zhang, L.; Tao, H. Effective Visible Light-Driven Photocatalytic Degradation of Ciprofloxacin over Flower-like Fe3O4/Bi2WO6 Composites. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 1647–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Zhou, W.; Sun, B.; Li, H.; Qiao, P.; Xu, Y.; Wu, J.; Lin, K.; Fu, H. Defects-Engineering of Magnetic γ-Fe2O3 Ultrathin Nanosheets/Mesoporous Black TiO2 Hollow Sphere Heterojunctions for Efficient Charge Separation and the Solar-Driven Photocatalytic Mechanism of Tetracycline Degradation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 240, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, J.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, W. Precisely Controlled Fabrication of Magnetic 3D γ-Fe2O3@ZnO Core-Shell Photocatalyst with Enhanced Activity: Ciprofloxacin Degradation and Mechanism Insight. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 308, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Kadokami, K.; Wang, S.; Duong, H.T.; Chau, H.T.C. Monitoring of 1300 Organic Micro-Pollutants in Surface Waters from Tianjin, North China. Chemosphere 2015, 122, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Model List of Essential Medicines—23rd List. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2023.02 (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Carballa, M.; Omil, F.; Lema, J.M.; Llompart, M.; García-Jares, C.; Rodríguez, I.; Gómez, M.; Ternes, T. Behavior of Pharmaceuticals, Cosmetics and Hormones in a Sewage Treatment Plant. Water Res. 2004, 38, 2918–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.L.; Aparicio, I.; Alonso, E. Occurrence and Risk Assessment of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds in Wastewater Treatment Plants. A Case Study: Seville City (Spain). Environ. Int. 2007, 33, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, V.L.; Perino, C.; D’Aco, V.J.; Hartmann, A.; Bechter, R. Human Health Risk Assessment of Carbamazepine in Surface Waters of North America and Europe. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 56, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allafchian, A.; Hosseini, S.S. Antibacterial Magnetic Nanoparticles for Therapeutics: A Review. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 13, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, I.; Roberts, M. Tetracycline Antibiotics: Mode of Action, Applications, Molecular Biology, and Epidemiology of Bacterial Resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2001, 65, 232–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghrir, R.; Drogui, P. Tetracycline Antibiotics in the Environment: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2013, 11, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Guo, J.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, J. Occurrence and Distribution of Tetracycline Antibiotics and Resistance Genes in Longshore Sediments of the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.; Belessiotis, G.V.; Elseman, A.M.; Mohamed, M.M.; Ren, Y.; Salama, T.M.; Mohamed, M.B.I. Magnetic TiO2/CoFe2O4 Photocatalysts for Degradation of Organic Dyes and Pharmaceuticals without Oxidants. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Multifunctional BiOI/SiO2/Fe3O4@n-Docosane Phase-Change Microcapsules for Waste Heat Recovery and Wastewater Treatment. Materials 2023, 16, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.S.; Kakavandi, B.; Noorisepehr, M.; Isari, A.A.; Zabih, S.; Bashardoust, P. Photocatalytic Oxidation of Tetracycline by Magnetic Carbon-Supported TiO2 Nanoparticles Catalyzed Peroxydisulfate: Performance, Synergy and Reaction Mechanism Studies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 258, 117936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhao, M.; Tan, C.; Ni, Y.; Fu, Q.; Li, H.; Li, C.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Z. Effect of Structural Optimization of Magnetic MnFe2O4@Bi24O31Br10/Bi5O7I with Core-Shell Structure on Its Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity to Remove Pharmaceuticals. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 681, 132763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musial, J.; Mlynarczyk, D.T.; Stanisz, B.J. Photocatalytic Degradation of Sulfamethoxazole Using TiO2-Based Materials—Perspectives for the Development of a Sustainable Water Treatment Technology. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awfa, D.; Ateia, M.; Fujii, M.; Yoshimura, C. Novel Magnetic Carbon Nanotube-TiO2 Composites for Solar Light Photocatalytic Degradation of Pharmaceuticals in the Presence of Natural Organic Matter. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 31, 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M.; Xue, Y.; Khalaj, M.; Laats, B.; Teunckens, R.; Verbist, M.; Costa, M.E.V.; Capela, I.; Appels, L.; Dewil, R. ZnO/γ-Fe2O3/Bentonite: An Efficient Solar-Light Active Magnetic Photocatalyst for the Degradation of Pharmaceutical Active Compounds. Molecules 2022, 27, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, T.; Salisbury, B.H.; Zito, P.M. Ciprofloxacin. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Chen, X.; Lv, Z.; Wang, B. Ultrahigh Ciprofloxacin Accumulation and Visible-Light Photocatalytic Degradation: Contribution of Metal Organic Frameworks Carrier in Magnetic Surface Molecularly Imprinted Polymers. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2022, 616, 872–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.; Mora, H.; Blasse, L.-M.; Martins, P.M.; Carabineiro, S.A.C.; Lanceros-Méndez, S.; Kühn, K.; Cuniberti, G. Photocatalytic Degradation of Recalcitrant Micropollutants by Reusable Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Particles. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2017, 345, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleckman, R.; Blagg, N.; Joubert, D.W. Trimethoprim: Mechanisms of Action, Antimicrobial Activity, Bacterial Resistance, Pharmacokinetics, Adverse Reactions, and Therapeutic Indications. Pharmacotherapy 1981, 1, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarp, G.; Yilmaz, E. g-C3N4@TiO2@Fe3O4 Multifunctional Nanomaterial for Magnetic Solid-Phase Extraction and Photocatalytic Degradation-Based Removal of Trimethoprim and Isoniazid. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 23223–23233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, E.; Salem, S.; Sarp, G.; Aydin, S.; Sahin, K.; Korkmaz, I.; Yuvali, D. TiO2 Nanoparticles and C-Nanofibers Modified Magnetic Fe3O4 Nanospheres (TiO2@Fe3O4@C–NF): A Multifunctional Hybrid Material for Magnetic Solid-Phase Extraction of Ibuprofen and Photocatalytic Degradation of Drug Molecules and Azo Dye. Talanta 2020, 213, 120813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Peng, J.; Fangqi, W.; Donghao, L.; Wenrong, M.; Jinmeng, Z.; Hu, W.; Li, N.; Pierre, D.; He, H. ZnO Nanorods/Fe3O4-Graphene Oxide/Metal-Organic Framework Nanocomposite: Recyclable and Robust Photocatalyst for Degradation of Pharmaceutical Pollutants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 21799–21811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Wahab, A.-M.; Al-Shirbini, A.-S.; Mohamed, O.; Nasr, O. Photocatalytic Degradation of Paracetamol over Magnetic Flower-like TiO2/Fe2O3 Core-Shell Nanostructures. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2017, 347, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.R.P.; Ribas, L.S.; Napoli, J.S.; Abreu, E.; Diaz de Tuesta, J.L.; Gomes, H.T.; Tusset, A.M.; Lenzi, G.G. Green Magnetic Nanoparticles CoFe2O4@Nb5O2 Applied in Paracetamol Removal. Magnetochemistry 2023, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buser, H.-R.; Poiger, T.; Müller, M.D. Occurrence and Environmental Behavior of the Chiral Pharmaceutical Drug Ibuprofen in Surface Waters and in Wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1999, 33, 2529–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Khan, M.; Fang, L.; Lo, I.M.C. Visible-Light-Driven N-TiO2@SiO2@Fe3O4 Magnetic Nanophotocatalysts: Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Degradation of PPCPs. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 370, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Fung, C.S.L.; Kumar, A.; Lo, I.M.C. Magnetically Separable BiOBr/Fe3O4@SiO2 for Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Degradation of Ibuprofen: Mechanistic Investigation and Prototype Development. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 365, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathishkumar, P.; Meena, R.A.A.; Palanisami, T.; Ashokkumar, V.; Palvannan, T.; Gu, F.L. Occurrence, Interactive Effects and Ecological Risk of Diclofenac in Environmental Compartments and Biota—A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 698, 134057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xie, X. Preparation of Magnetic Nanosphere/Nanorod/Nanosheet-like Fe3O4/Bi2S3/BiOBr with Enhanced (001) and (110) Facets to Photodegrade Diclofenac and Ibuprofen under Visible LED Light Irradiation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 378, 122169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.; Moya, P.; Bosca, F.; Marin, M.L. Photoreactivity of New Rose Bengal-SiO2 Heterogeneous Photocatalysts with and without a Magnetite Core for Drug Degradation and Disinfection. Catal. Today 2023, 413–415, 113994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakavandi, B.; Dehghanifard, E.; Gholami, P.; Noorisepehr, M.; MirzaHedayat, B. Photocatalytic Activation of Peroxydisulfate by Magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2@TiO2/rGO Core–Shell towards Degradation and Mineralization of Metronidazole. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 570, 151145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpour, N.; Sayadi, M.H.; Sobhani, S.; Hajiani, M. A Potential Natural Solar Light Active Photocatalyst Using Magnetic ZnFe2O4@TiO2/Cu Nanocomposite as a High Performance and Recyclable Platform for Degradation of Naproxen from Aqueous Solution. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Rana, A.; Sharma, G.; Naushad, M.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Guo, C.; Iglesias-Juez, A.; Stadler, F.J. High-Performance Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production and Degradation of Levofloxacin by Wide Spectrum-Responsive Ag/Fe3O4 Bridged SrTiO3/g-C3N4 Plasmonic Nanojunctions: Joint Effect of Ag and Fe3O4. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 40474–40490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-Y.; Lai, W.W.-P.; Lin, H.H.-H.; Tan, J.X.; Wu, K.C.-W.; Lin, A.Y.-C. Photocatalytic Degradation of Ketamine Using a Reusable TiO2/SiO2@Fe3O4 Magnetic Photocatalyst under Simulated Solar Light. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamranifar, M.; Allahresani, A.; Naghizadeh, A. Synthesis and Characterizations of a Novel CoFe2O4@CuS Magnetic Nanocomposite and Investigation of Its Efficiency for Photocatalytic Degradation of Penicillin G Antibiotic in Simulated Wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 366, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarasinghe, L.V.; Muthukumaran, S.; Baskaran, K. Recent Advances in Visible Light-Activated Photocatalysts for Degradation of Dyes: A Comprehensive Review. Chemosphere 2024, 349, 140818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamba, G.; Mishra, A. Advances in Magnetically Separable Photocatalysts: Smart, Recyclable Materials for Water Pollution Mitigation. Catalysts 2016, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Ye, Y.; Ye, J.; Gao, T.; Wang, D.; Chen, G.; Song, Z. Recent Advances of Magnetite (Fe3O4)-Based Magnetic Materials in Catalytic Applications. Magnetochemistry 2023, 9, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, P.M.; Jaramillo, J.; López-Piñero, F.; Plucinski, P.K. Preparation and Characterization of Magnetic TiO2 Nanoparticles and Their Utilization for the Degradation of Emerging Pollutants in Water. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 100, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivula, K.; Le Formal, F.; Grätzel, M. Solar Water Splitting: Progress Using Hematite (α-Fe2O3) Photoelectrodes. ChemSusChem 2011, 4, 432–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radić, J.; Žerjav, G.; Jurko, L.; Bošković, P.; Fras Zemljič, L.; Vesel, A.; Mavrič, A.; Gudelj, M.; Plohl, O. First Utilization of Magnetically-Assisted Photocatalytic Iron Oxide-TiO2 Nanocomposites for the Degradation of the Problematic Antibiotic Ciprofloxacin in an Aqueous Environment. Magnetochemistry 2024, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadpour, F.; Mohammad Amani, A. Photocatalytic Systems: Reactions, Mechanism, and Applications. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 20609–20645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.G.; Kang, J.M.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, K.H.; Cho, M.; Lee, S.G. Effects of Calcination Temperature on the Phase Composition, Photocatalytic Degradation, and Virucidal Activities of TiO2 Nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 10668–10678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.V.; Truong, T.K.; Hai, L.V.; La, H.P.P.; Nguyen, H.T.; Lam, V.Q.; Tong, H.D.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Sabbah, A.; Chen, K.-H.; et al. S-Scheme α-Fe2O3/g-C3N4 Nanocomposites as Heterojunction Photocatalysts for Antibiotic Degradation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 4506–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, R.; Nayebi, B.; Ayati, B. Investigating the Effect of Hydrogen Peroxide as an Electron Acceptor in Increasing the Capability of Slurry Photocatalytic Process in Dye Removal. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 83, 2414–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragaw, T.A.; Bogale, F.M.; Aragaw, B.A. Iron-Based Nanoparticles in Wastewater Treatment: A Review on Synthesis Methods, Applications, and Removal Mechanisms. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2021, 25, 101280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruziwa, D.T.; Oluwalana, A.E.; Mupa, M.; Meili, L.; Selvasembian, R.; Nindi, M.M.; Sillanpaa, M.; Gwenzi, W.; Chaukura, N. Pharmaceuticals in Wastewater and Their Photocatalytic Degradation Using Nano-Enabled Photocatalysts. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 54, 103880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Tang, Y.; Ma, C.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J. Deactivation and Regeneration of Photocatalysts: A Review. Desalination Water Treat. 2018, 124, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Dong, W.; Huang, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhou, J.L.; Li, W. Photocatalysis for Sustainable Energy and Environmental Protection in Construction: A Review on Surface Engineering and Emerging Synthesis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelaez, M.; Nolan, N.T.; Pillai, S.C.; Seery, M.K.; Falaras, P.; Kontos, A.G.; Dunlop, P.S.M.; Hamilton, J.W.J.; Byrne, J.A.; O’Shea, K.; et al. A Review on the Visible Light Active Titanium Dioxide Photocatalysts for Environmental Applications. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 125, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, M.; Kosma, C.; Albanis, T.; Konstantinou, I. An Overview of Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Photocatalysis Applications for the Removal of Pharmaceutical Compounds from Real or Synthetic Hospital Wastewaters under Lab or Pilot Scale. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 765, 144163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Zhang, Y.; Farghali, M.; Rashwan, A.K.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Abd El-Monaem, E.M.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; Badr, M.M.; Ihara, I.; Rooney, D.W.; et al. Synthesis of Green Nanoparticles for Energy, Biomedical, Environmental, Agricultural, and Food Applications: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 841–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malato, S.; Fernández-Ibáñez, P.; Maldonado, M.I.; Blanco, J.; Gernjak, W. Decontamination and Disinfection of Water by Solar Photocatalysis: Recent Overview and Trends. Catal. Today 2009, 147, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, K.S.; Tayade, R.J.; Shah, K.J.; Joshi, P.A.; Shukla, A.D.; Gandhi, V.G. Photocatalytic Degradation of Pharmaceutical and Pesticide Compounds (PPCs) Using Doped TiO2 Nanomaterials: A Review. Water-Energy Nexus 2020, 3, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velempini, T.; Prabakaran, E.; Pillay, K. Recent Developments in the Use of Metal Oxides for Photocatalytic Degradation of Pharmaceutical Pollutants in Water—A Review. Mater. Today Chem. 2021, 19, 100380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ariza Gonzalez, M.; Hoijang, S.; Tran, D.B.; Tran, Q.M.; Atik, R.; Islam, R.; Maparathne, S.; Wongthep, S.; Yarinia, R.; Amarasekara, R.; et al. Surface-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotics in Wastewater: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 844. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020844

Ariza Gonzalez M, Hoijang S, Tran DB, Tran QM, Atik R, Islam R, Maparathne S, Wongthep S, Yarinia R, Amarasekara R, et al. Surface-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotics in Wastewater: A Review. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):844. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020844

Chicago/Turabian StyleAriza Gonzalez, Melissa, Supawitch Hoijang, Dang B. Tran, Quoc Minh Tran, Refia Atik, Rafiqul Islam, Sugandika Maparathne, Sujitra Wongthep, Ramtin Yarinia, Ruwanthi Amarasekara, and et al. 2026. "Surface-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotics in Wastewater: A Review" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 844. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020844

APA StyleAriza Gonzalez, M., Hoijang, S., Tran, D. B., Tran, Q. M., Atik, R., Islam, R., Maparathne, S., Wongthep, S., Yarinia, R., Amarasekara, R., Chinwangso, P., & Lee, T. R. (2026). Surface-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotics in Wastewater: A Review. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 844. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020844