1. Introduction

In the past decade, the capture of surrounding environmental energy and its transformation into electrical power, known as energy harvesting, has become a vital approach for supporting and energizing microscale devices. These devices, often characterized by their small size and limited energy resources, include wireless sensors [

1,

2,

3], medical implants [

4,

5,

6], and various Internet of Things (IoT) devices [

7,

8]. To meet the growing demand for autonomous and self-sustaining microscale devices, a range of energy harvesting techniques have been developed, including piezoelectric [

9], photovoltaic [

10,

11], electromagnetic [

12], and thermoelectric [

13] methods, each designed to harness different forms of energy. Of these techniques, piezoelectric energy harvesting has attracted much attention because of the straightforward design and ease of manufacturing of this type of energy harvester. As the simplest form of piezoelectric energy harvesters, a cantilever-based energy harvester generally features a beam fixed at one end, with a piezoelectric material either layered on the upper surface of the cantilever or forming the entire structure of the device. When exposed to mechanical vibrations, the cantilever structure experiences bending deformation, which creates stress and strain within the piezoelectric material, resulting in electrical charge generation. Nevertheless, the performance of cantilever-based piezoelectric energy harvesters remains constrained by the inherent structural dimensions and physical characteristics of the materials employed.

In recent years, a wide range of strategies and methodologies to improve the power output efficiency of energy harvesting systems have been proposed. Researchers are actively exploring methods to increase piezoelectric device performance, with a focus on alternative designs to increase the energy capture efficiency. Upadrashta et al. [

14] conducted design optimization research on a nonlinear energy harvester that utilized a magnetic oscillator, highlighting the significant influence of the material strength on the overall design process. Their parametric study identified an optimal configuration, demonstrating that material constraints must be considered in effective energy transducer design. Moreover, Hashim et al. [

15] investigated shape optimization by examining a variety of cross-sectional geometries, including rectangular, triangular, circular, and trapezoidal shapes, to determine the most effective design for power generation. Their findings suggest that a trapezoidal cross-section offers the highest power output, underscoring the importance of geometry in energy harvester design. Sunithamani et al. [

16] discussed a microelectromechanical system (MEMS)-based energy harvester featuring an unconventional design incorporating a T-shaped cantilever with a triangular tip. Simulations performed using COMSOL 6.3 revealed that this configuration yielded a more favourable strain distribution and a higher voltage output than conventional triangular and rectangular geometries operating at the resonant frequency. Nevertheless, this study primarily emphasized the strain distribution and voltage output, overlooking the harvested power. Additionally, the specific step size used for the simulations was not disclosed, which affects the accuracy of the results.

Regarding the methods for optimizing the shape of cantilever, the topology optimization method proposed by Motlagh et al. [

17] focuses on enhancing the performance of piezoelectric materials by integrating finite element modelling with optimality criteria and advanced gradient-based optimization techniques to iteratively refine the material density distribution and polarization orientation. By employing these methods, the optimization variables are updated by the codes while ensuring numerical stability through normalized finite element equations, ultimately demonstrating efficacy in actuation and energy harvesting applications; however, final shapes are not easy to manufacture in practice. Diaconu et al. [

18] introduced an optimized design of a nonlinear piezoelectric energy harvester featuring a self-coupled two-degree-of-freedom structure and conducted a comparative analysis with a traditional nonlinear energy harvester that utilized mechanical stoppers. Through optimization, the novel harvester demonstrated a significant 3.54-fold increase in the maximum output power and an expanded operational bandwidth, showing the promise of the optimization approach for practical application in improving vibration energy harvesters.

Regarding the different cantilever designs examined in previous studies, a double-cantilever-beam (DCB) design was proposed and compared with the traditional design by Song et al. [

19]. Through the optimization of the geometrical dimensions on the basis of peak voltages and resonance frequency differences and assessment of the energy harvesting efficiency, a substantial performance increase over that of traditional single-cantilever-beam (SCB) harvesters under multifrequency excitation was achieved. Alternative structures, including hollow triangular beams with high aspect ratios, were evaluated alongside standard rectangular beams [

20]. Three types of piezoelectric cantilever beam (PCB) harvesters—rectangular, trapezoidal, and triangular—were examined in this study, focusing on their power generation under low-frequency vibrations common in transportation infrastructure. The findings revealed that triangular PCB harvesters yield higher voltage outputs. Additionally, hollow triangular piezoelectric cantilever beams (HTPCBs) display a broader resonant frequency range, with improved effectiveness in variable vibration environments. Energy harvesting from transportation infrastructure vibrations could be increased by deploying HTPCBs. C. V. Karadag et al. [

21] proposed a new width profile function featuring curved shapes to improve the strain uniformity and harvesting efficiency. Through the use of a finite element optimization scheme, this study revealed that, compared with traditional triangular and rectangular beams, curved beams exhibit significantly reduced axial strain variation, resulting in a 29% increase in the strain uniformity, thus linearly proportionally increasing energy generation, with a 5 g tip mass. Experimental results corroborated these findings, confirming the benefits of optimized width profiles in energy harvesters.

A nontraditional design approach was adopted by Izadgoshasb et al. [

22], aiming to improve the efficiency of multiresonant piezoelectric energy harvesters (MRPEHs) under low-frequency vibration conditions, including those produced by human movement. In this study, an optimized cantilever beam design featuring two triangular branches was employed, which was adapted to match the frequency range of the targeted vibrations. Finite-element analysis was utilized for a series of parametric studies, providing insights into how design variables affect the power output. Additionally, optimization techniques that involve reimagining the width or thickness of the cantilever were recently proposed to keep the design of the cantilever simple while increasing the power generation efficiency. Tecpoyotl-Torres et al. [

23] studied different, nonstandard width designs, in which a new beam form was presented on the basis of alternating segments of varying widths. These designs were assessed by computing and simulating the performance of one-quarter, half-, and full-energy transducers and comparing the results to those from identical scenarios with traditional uniform beams. In all situations, the smart proof mass displacement was significantly improved, particularly with the proposed symmetrically shaped beam.

Tapered beam designs are also common in cantilever optimization. Matova et al. [

24] and Cencic et al. [

25] discussed linearly tapered and reverse tapered cross-sections of a cantilever and reported that the power output was overestimated since the shunt damping effect was low. Other scientists investigated the effects of thickness parameters on the efficiency of harvesters. He et al. [

26] proposed topology optimization along the thickness direction to achieve a high energy conversion efficiency and a high open-circuit voltage. However, their study concentrated on the distribution of piezoelectric materials in a standard square-thickness cantilever without examining the structural thickness of the cantilever itself. While existing optimization techniques for piezoelectric harvesters focus primarily on improving cantilever shapes by optimizing width parameters, many of these approaches still face challenges such as spatial limitations, high costs, and complex designs, rendering them impractical for real-world applications.

In this paper, to improve the energy conversion efficiency of piezoelectric energy harvesters, an optimization design that specifically targets the thickness of piezoelectric energy harvester cantilevers is presented. The optimizable cantilever is not constrained by a fixed size, resulting in a thickness profile that is inherently manufacturable. This makes the method suitable for both macro-scale prototypes and MEMS-scale practical applications, although minimum feature size and thickness limits primarily depend on the selected material. Most of previously mentioned designs feature complicated active element shapes, whereas our proposed design prioritizes simplicity and effectiveness and results in significant increases in the maximum strain in the substructure element and a broader strain distribution across the cantilever, which in turn enhances the electricity generation efficiency. While width optimization tends to proportionally increase the strain, our approach of thickness optimization can increase the strain, significantly increasing the overall performance. By focusing on the optimization of the cantilever thickness instead of width and employing the gradient projection method to maximize the strain in the upper layer of the active element and achieve wider strain regions, we avoid unnecessary complexity in the design. This non-linear thickness optimization approach not only differentiates our method from traditional methods but also has the potential to improve the energy harvesting performance. Two cantilevers are optimized for the first and second eigenfrequencies by a state-space gradient projection method combined with design sensitivity analysis resulting in novel shapes that are both mathematically and experimentally validated compared to uniform rectangular profile beams with the same eigen frequencies.

3. Finite-Dimensional Optimal Design Method for a Vibration Energy Harvester Elastic Substrate at Its Eigenfrequencies

To improve the energy conversion efficiency of piezoelectric energy harvesters, a method for optimizing the design of the vibration energy harvester elastic substrate is formulated. An integral part of designing modern vibration energy harvesters is to determine their optimal design, which enables the creation of structures that meet the set requirements. In this study, to find the optimal design of vibration energy harvesters, methods based on nonlinear programming modified for mechanical vibration systems are used. To design the optimal shape of the elastic substrate element, a gradient projection method in state space is used. The elastic substrate element is modelled using the FEM. The problem of optimal design of a cantilever-type vibration energy harvester in its eigenmodes for given eigenfrequencies of transverse oscillations of the elastic substrate element is considered. An analysis of the optimal design method is carried out, recommendations for selecting the initial design variables are given, and their influence on the convergence and time of the solution are analysed.

To design systems in cantilever optimal design problems, quantities called design variables must be selected. The design variables are denoted by

or in vector form simply by

. For the cantilever-type vibration energy harvester, the role of the design variables is affected by the thickness of the beam elements. Constraints are imposed on the characteristics of the systems being designed, and limitations related to the operating mode are imposed on the system. Thus, the thickness of the cantilever elements is limited to upper and lower values on the basis of design considerations. The specified constraints and requirements generally determine the set from which design variables are selected. The set

from which design variables are selected is called the set of possible values of design variables. In addition, there is a second set of variables that describe the behaviour of the system since the designed system is subject to certain physical laws. This behaviour is described by a set of variables called state variables. The state variables are also an

n-vector

. The equations that determine the state of the structure depend on the design variables; thus, the two sets of variables are interconnected. The elastic substrate element of the cantilever-type vibration energy harvester is presented in

Figure 3.

When constructing an optimal projection from among possible projections, the projection that maximizes the value of the objective function for vector is selected since the objective function corresponds to the strain integral in the top layer of the cantilever.

To solve the optimization problem, the gradient projection method in nonlinear programming is used [

33]. This method uses information only about first derivatives or gradients when constructing successful improved corrections for solving multiobjective design problems. In gradient methods, the direction along which the objective function

most rapidly increases is first determined. This direction is specified by

and is subsequently projected into a hyperplane tangent on the boundary of the permissible region. A small variation along the resulting direction that increases

and does not lead to a strong violation of the constraints is applied. This procedure is repeated until

can no longer increase.

The finite-dimensional problem of the optimal design of the elastic substrate element can be formulated as follows:

Find

That maximize

subject to the state equation

and constraints

where

—stiffness matrix of the elastic substrate;

—inertia matrix of the elastic substrate;

—matrix of eigenvectors of a given vibration mode;

—diagonal matrix of corresponding eigenvalues.

Since (54) is homogeneous with respect to its eigenvector , it can be normalized by the condition .

The dependence on state variables is eliminated in the linearized problem, and this problem is subsequently solved for the direction of steepest ascent.

The optimal design is described by a vector

. To solve equation of state (54), the subspace iteration method [

34] is used.

The effect of a change in

of

is subsequently determined, with

By substituting the new design variable

, Equation (54) can be solved with respect to the new corresponding state variables

and

. On the basis of the implicit function theorem [

35], a small change in

by

clearly causes small changes

and

d in eigenvalue problem (54).

Sensitivity analysis is highly important. Accurate information about the sensitivity is provided by the variables of the conjugate equations. From the sensitivity analysis, the gradient values required for iterative projection optimization methods are obtained. Sensitivity analysis consists of constructing an approximation of the design problem. The approximated problem is obtained by linear approximation of nonlinear problems. The linear approximations of the changes in

and

due to small changes in variables are as follows:

where

before a function represents its total differential. By multiplying Equation (54) on the left by

, we obtain

. Approximating both sides to the first order in variables

, we obtain

where

. Since the matrices

and

are symmetric,

and

Therefore, Equation (59) can be written as

Considering that

,

Equation (62) determines the change in the eigenvalue

depending on the change in the projection

. By substituting this into (58),

can be expressed through

as

or

where

is calculated at point

according to

Column

of matrix

is as follows:

Column represents the sensitivity coefficients of the -th constraint with respect to the design variables and consists of the derivatives of this constraint. Element is the derivative of with respect to the -th design variable. Thus, if , an increase in will lead to an increase in ; if , an increase in will result in a decrease in .

The problem of optimal design of an elastic substrate element consists of determining the vector of design variables , maximizing objective function , and satisfying state Equation (54) and constraints in the form of inequality (55).

The role of the objective function Ψ0 (b), is to maximize total absolute normal strain in the top layer of the elastic substrate element, which is given as the sum of the normal strains of the finite elements. Inequality (55) represents constraints on the eigenfrequencies and the design variable—the thickness of the beam.

The objective function takes the following form:

where

Because the thickness of the elastic substrate is constrained by upper and lower limits, the upper and lower limits of the thickness for each finite element must also be constrained:

To avoid ill-conditioned matrices when performing calculations using the gradient projection method, the constraints must be normalized to their limit values. Therefore, each constraint should be represented in the form

for constraint (70) and

for constraint (71), with

.

To address resonance phenomena, the lowest eigenfrequencies of oscillations of the elastic substrate element must be limited. The eigenfrequencies are obtained by solving eigenvalue problem (50) via the subspace iteration method [

34]. The eigenfrequencies and eigenvectors used are obtained in the previous iteration of the optimization process. This enables a considerable reduction in the computation time for the eigenvalue problem. The upper and lower constraints on the eigenvalues of the elastic substrate element can be represented as

where

and

are vectors of the lower and upper boundaries of the eigenvalues of the elastic substrate element. Similarly to the constraints on the design variables, the constraints on the state variables and eigenvalues must be normalized. Thus, constraints (74) and (75) take the forms

where

.

During the design process, whether the constraints are active is checked at each iteration. If an active constraint is close to being violated, this issue must be addressed, and the response must be determined. For this purpose, Equations (71)–(74) are limited:

where

.

During the design process, a sensitivity analysis is performed at each iteration. Derivatives with respect to the design variables can be found using Equation (68). The derivatives with respect to the design variables for constraints (70) and (71) have simple forms:

Regarding the constraints on the eigenvalues,

and

for constraint (74), and

for constraint (75). Therefore, the vector

from (63) completely determines the derivative with respect to the design variables obtained using (68), i.e.,

The gradient vector of the objective function is determined by Equation (67), which in this case takes the form

Using the gradient matrix of active constraints (68) and the vector of the objective function gradient (67), we determine the Lagrange multipliers, the vectors of which are denoted

and

:

where

is a positive definite weight matrix and

is the response vector of the active and/or violated constraints.

Next, the vectors of variations in the design variables are projected:

where

The coefficient

used to express the step of the objective function can be easily determined:

where

is the required increase in the objective function in one iteration, with

where

is the coefficient of percentage increase in the objective function.

Next, the vector multiplier

is calculated:

If all the components of vector

corresponding to the active constraints are positive, then there is a solution that satisfies the Tucker criterion [

33]. In contrast, if a component of vector

is negative, then the objective function

has a value less than the maximum value, and a better result can be obtained by applying the appropriate constraints. After a solution satisfying the Tucker criterion is obtained, the number of constraints is decreased, so the corresponding columns must be removed from matrix

, and all calculations must be repeated for the remaining active constraints. This procedure is repeated until all the components of

become nonnegative. Then, the projection variation is determined by the equation

The new vector of design variables takes the form

If design satisfies all the constraints, then there is no variation that does not violate the constraints and reduce . Thus, is a relative maximum in the nonlinear programming problem. If and are sufficiently small, the solution to the problem has been obtained. A finite-dimensional optimal design method has thus been established.

The gradient projection method in state space is performed in MATLAB R2024b, and a class of problems related to optimization of the vibration energy harvester substructure element is solved. Usually, the optimal design is completed in a finite number of iterations. Correct selection, from an engineering point of view, of the design variables and constraints plays a major role in obtaining a successful solution. A selected initial design that is far from optimal increases the number of iterations in the optimization process and therefore the solution time. The opposite choice may not lead to the desired result.

4. Optimization Results

To improve the energy conversion efficiency of piezoelectric energy harvesters, the thickness of the elastic substrate element within a piezoelectric energy harvesting system was chosen such that the strain in the upper layer of the beam was as large as possible while satisfying the geometry and eigenfrequency constraints. The results of this design optimization process are outlined in this section. For the elastic substrate beam element optimal design, the following values were employed: L = 100 mm (active length, with 140 mm total length of the specimen) and width = 10 mm. Two types of design constraints were considered: the beam thickness was constrained to a minimum value of 0.8 mm, with frequency constraints of ω

1 = 21 Hz for the first eigenfrequency and ω

2 = 271 Hz for the second eigenfrequency. The beam eigenfrequencies must match the target natural frequencies to ensure that the optimization process reflects enhancements to the existing beam design, rather than creating an unrelated system. The FEM was used for numerical analysis, with a total of 20 beam-type finite elements used for optimal design. The Engineering Resin Tough 2000 (Formlabs Inc., Somerville, MA, USA) photopolymer was selected for the design due to its inherent homogeneity and uniform composition, ensuring a reliable basis for comparative analysis. The material properties are listed in

Table 1.

The optimization results of the uniform and optimized elastic substrate beam element designs were compared. The initial design has a uniform, 0.9 mm thick cantilever beam profile along its length.

Figure 4 presents the cantilever design optimized for the first eigenfrequency (ω

1). The optimized design significantly deviates from the uniform profile. The thickness varies from 1.25 mm to 2.14 mm.

The optimized cantilever design comprises two distinct functional segments. First, a linearly tapered beam extends from the clamped end at 0 L to 0.58 L along the elastic substrate length L. This segment uniformly narrows in thickness from 1.25 mm at the clamped end of the cantilever to 0.95 mm at the thinnest part, which is located at 0.58 L, and this profile contributes to a constant strain distribution throughout this segment of the beam. The second segment starts at 0.58 L, the thinnest part of the beam, then increases to the maximum thickness of 2.14 mm, and this thickness is constant to the free end of the cantilever beam at 1.0 L. This segment can function as an effective added mass, increasing the overall inertia of the system and potentially enhancing the energy harvesting efficiency at the first eigenfrequency. The most important feature of the optimal design is the nonlinear rise in the thickness in the second segment of the beam, which is crucial in improving the efficiency.

Figure 5 presents the cantilever design optimized for the second eigenfrequency ω

2. The initial design is a cantilever with a uniform thickness of 1.8 mm across all of its length. The optimized design exhibits a significantly nonuniform thickness distribution, with a minimum thickness of 1.45 mm and a maximum thickness of 2.33 mm.

The optimized cantilever design can be divided into three functionally distinct segments for further analysis. The first segment, beginning at the clamped end of the cantilever, features a substantially increased thickness (compared with the uniform form for ω2) starting at 2.33 mm. This segment may experience minimal strain due to its proximity to the fixed end, acting more as a structural component ensuring the integrity of the design during operation. This segment extends from the clamped end to 0.54 L along the total length of the cantilever. The second segment quickly nonlinearly narrows from the thick first segment to the thinnest part of the beam, reaching 1.45 mm, and extends to 0.84 L of the total cantilever length. This segment has a relatively uniform thickness profile, and its linearly elastic behaviour contributes to a predictable and efficient strain distribution. The final segment, located from 0.84 L to the free end of the cantilever, features a nonlinear thickness profile. This segment quickly changes from the thinnest part of the cantilever to a thickness of 2.1 mm and functions as an effective added mass, increasing the overall inertia of the system and potentially enhancing the energy harvesting efficiency at the second eigenfrequency.

The strategic combination of these three segments—a thicker linear beam, a thinner linear second segment, and a thick end part, with nonlinear transitions between them—is essential for improving the performance of the optimized cantilever design. This three-sectional design effectively functions as two coupled cantilevers operating in a partially counterphase manner. Segmented piezoelectric elements are thus crucial to avoid cancellation effects and maximize energy harvesting. Segmentation appears at the strain node of the second eigenfrequency at 0.41 L.

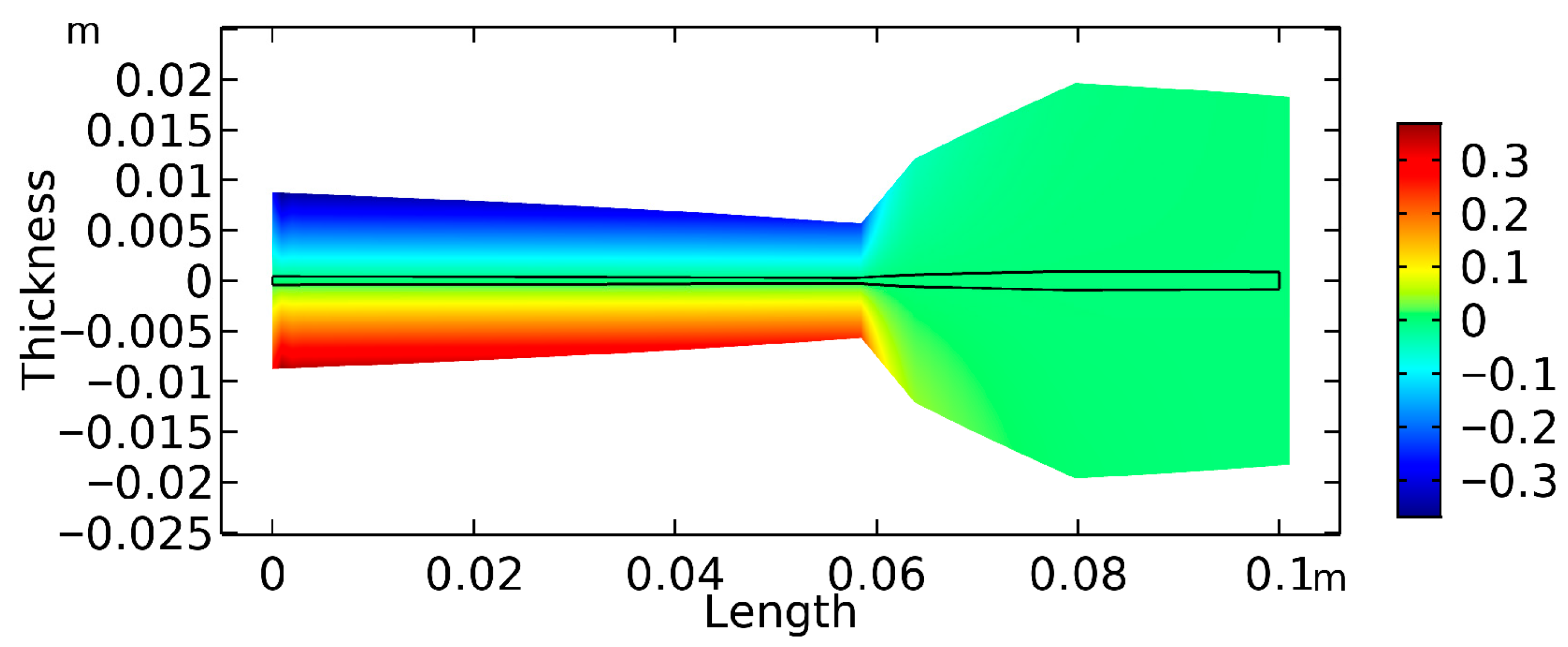

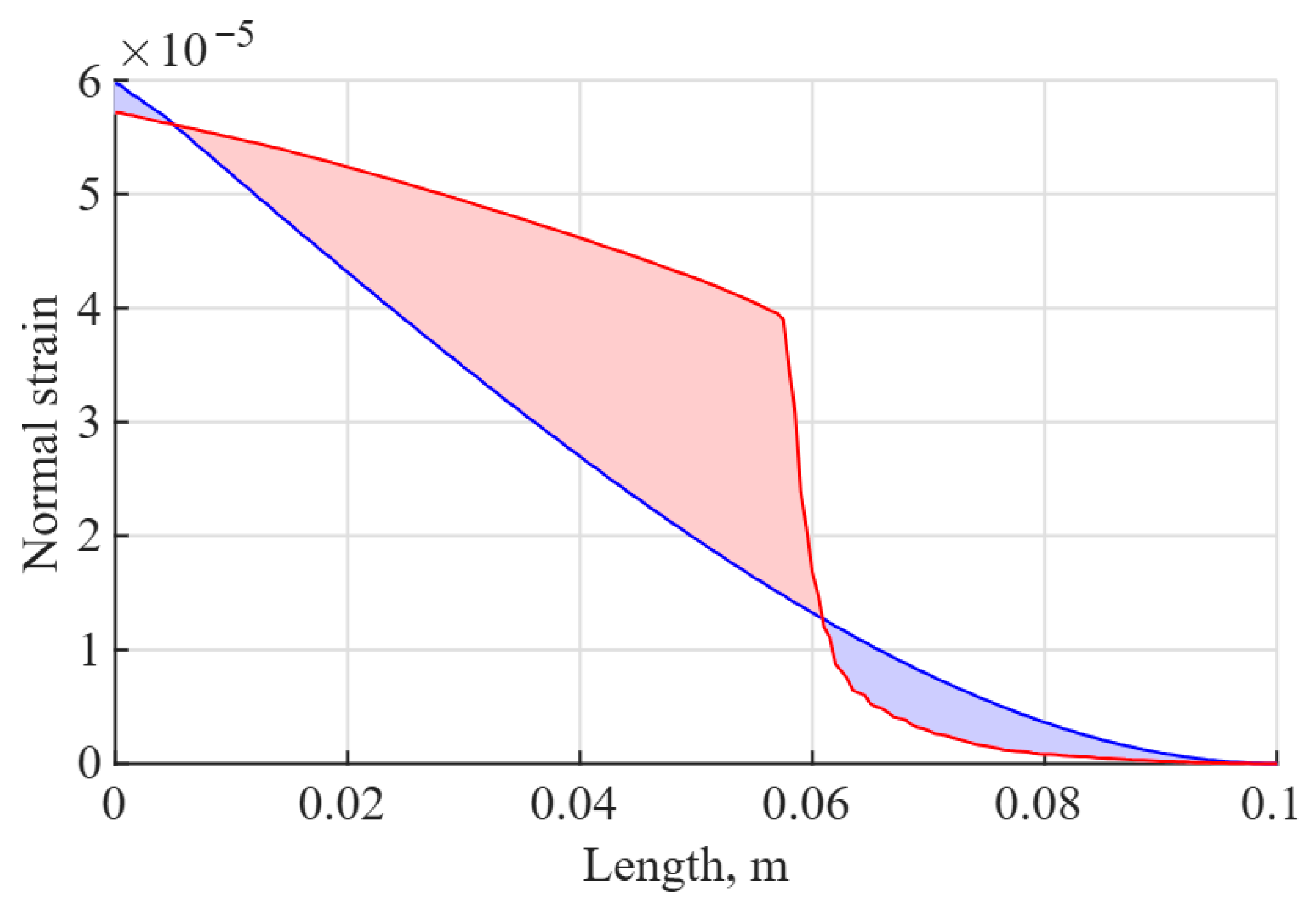

To determine how the optimization affects the energy conversion efficiency of the cantilever beam, the normal strain distribution field of the cantilever design optimized for the first eigenfrequency was calculated. The normal strain distribution of the cantilever design optimized for the first eigenfrequency is presented in

Figure 6. As previously mentioned, this cantilever has two main segments; the first one, from the clamped end, is a slightly tapered segment with a constant strain distributed along its entire length. The second segment acts as a nonlinearly distributed extra mass, further enhancing the overall energy conversion efficiency.

This segment is instrumental in maximizing the energy harvesting performance. While the bisegmental design, with a reduced length of the linearly elastic beam segment (0.58 L), might initially appear suboptimal, as it shortens the working length of the element where the energy generation may occur, the strategically designed nonlinear mass distribution in the terminal segment significantly enhances strain generation, resulting in improved energy harvesting performance.

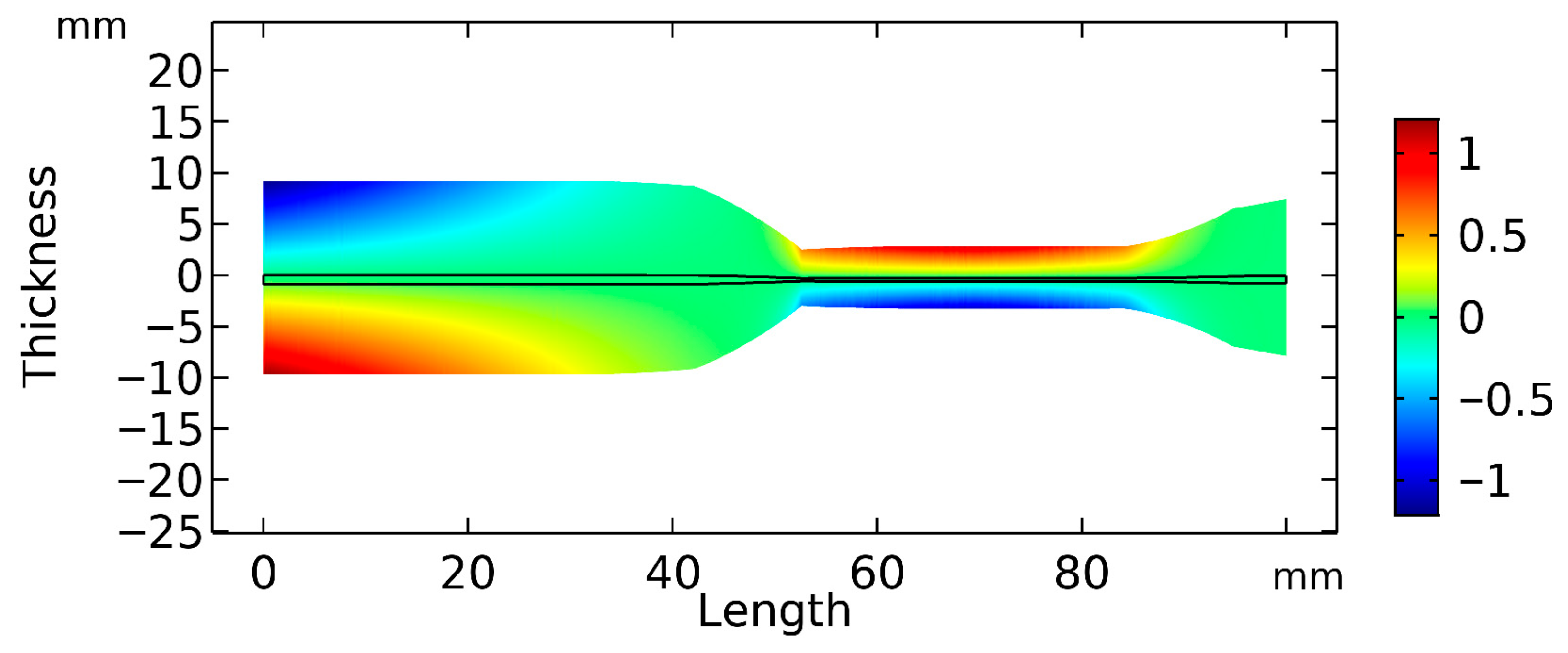

Figure 7 shows the normal strain distribution of the cantilever design optimized for the second eigenfrequency. The three distinct segments of the cantilever effectively function as two coupled cantilevers operating in a partially counterphase manner. The initial segment, near the clamped end, exhibits typical cantilever behaviour, with the maximum strain at the clamped end and the strain decreasing towards the transition to the second segment. The second segment, with its constant strain distribution, efficiently and uniformly generates the maximum strain throughout the whole region. The final segment, featuring minimal strain, functions primarily as an added mass.

The nonlinear transitions between these segments, along with the strategic segmentation of the piezoelectric elements, are critical to the performance of this design. The nonlinear, gradual changes in the thickness profile lead to a nonuniform mass distribution, which significantly broadens the operational bandwidth compared with a conventional cantilever. This coupled-cantilever behaviour, with its partially counterphase dynamic response, enhances the energy harvesting efficiency of this design.

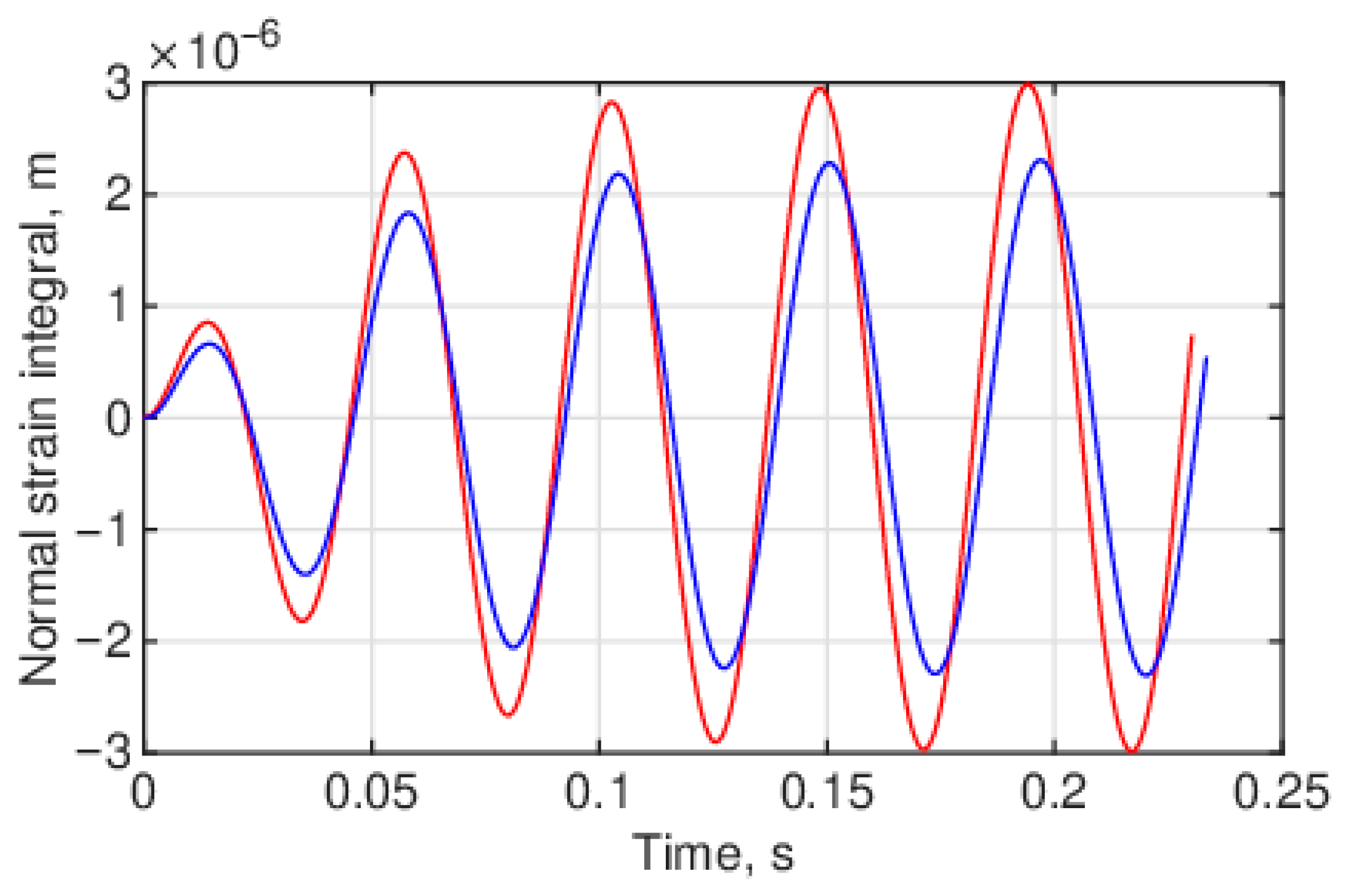

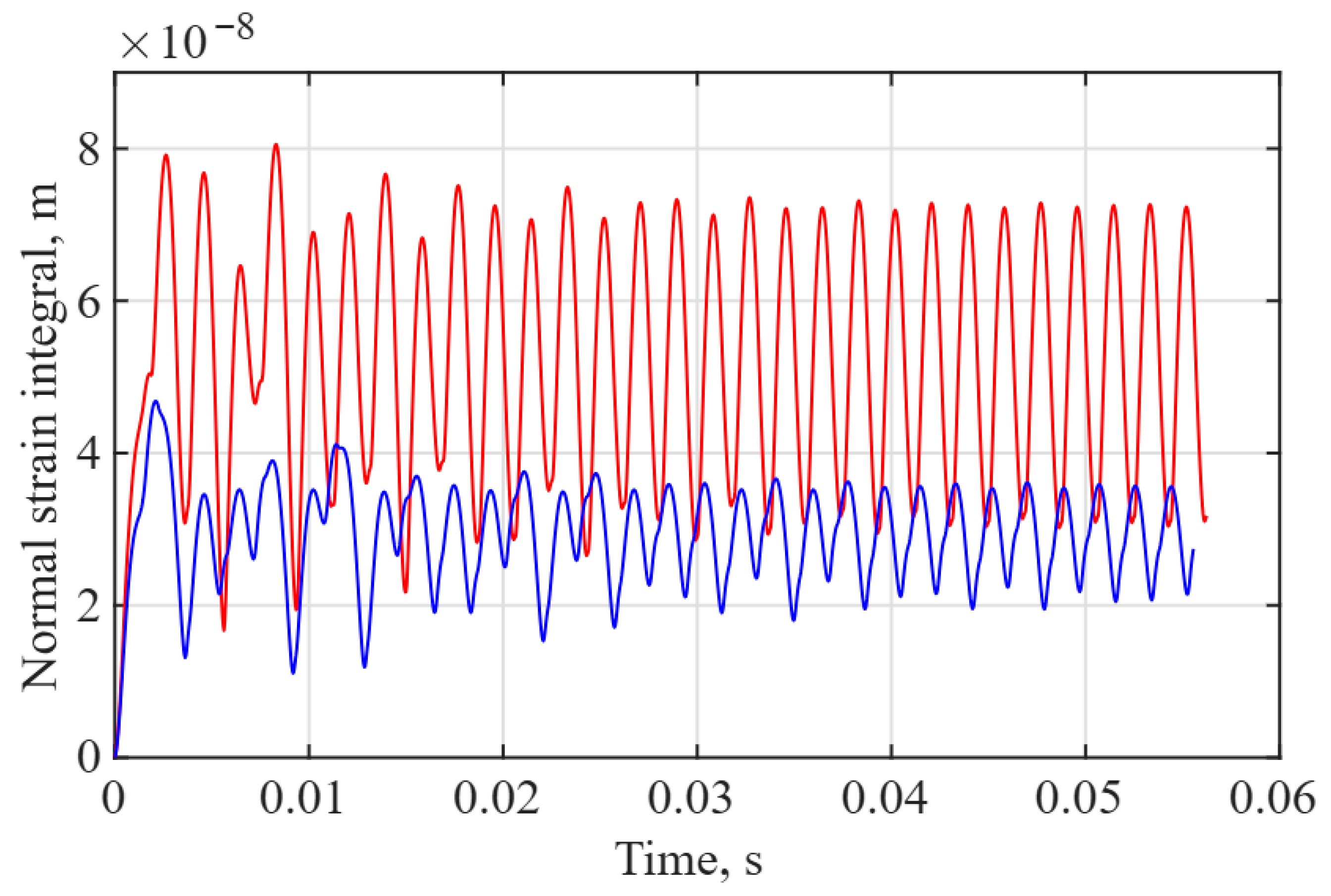

Transient analysis reveals significant enhancements in the strain generation for the optimized cantilever design compared with the uniform cross-section beam design. The integral of the normal strain in the upper layer of the uniform cantilever design and the design optimized for the first eigenfrequency is presented in

Figure 8. The normal strain is dimensionless, but after integration along the length, the results are obtained in metres. The figure shows the amount of strain generated by the elastic substrate during vibration at the first eigenfrequency.

The uniform cantilever exhibits a maximum strain integral of 2.2 × 10−6 m, whereas the optimized cantilever design yields a maximum strain integral of 3 × 10−6 m.

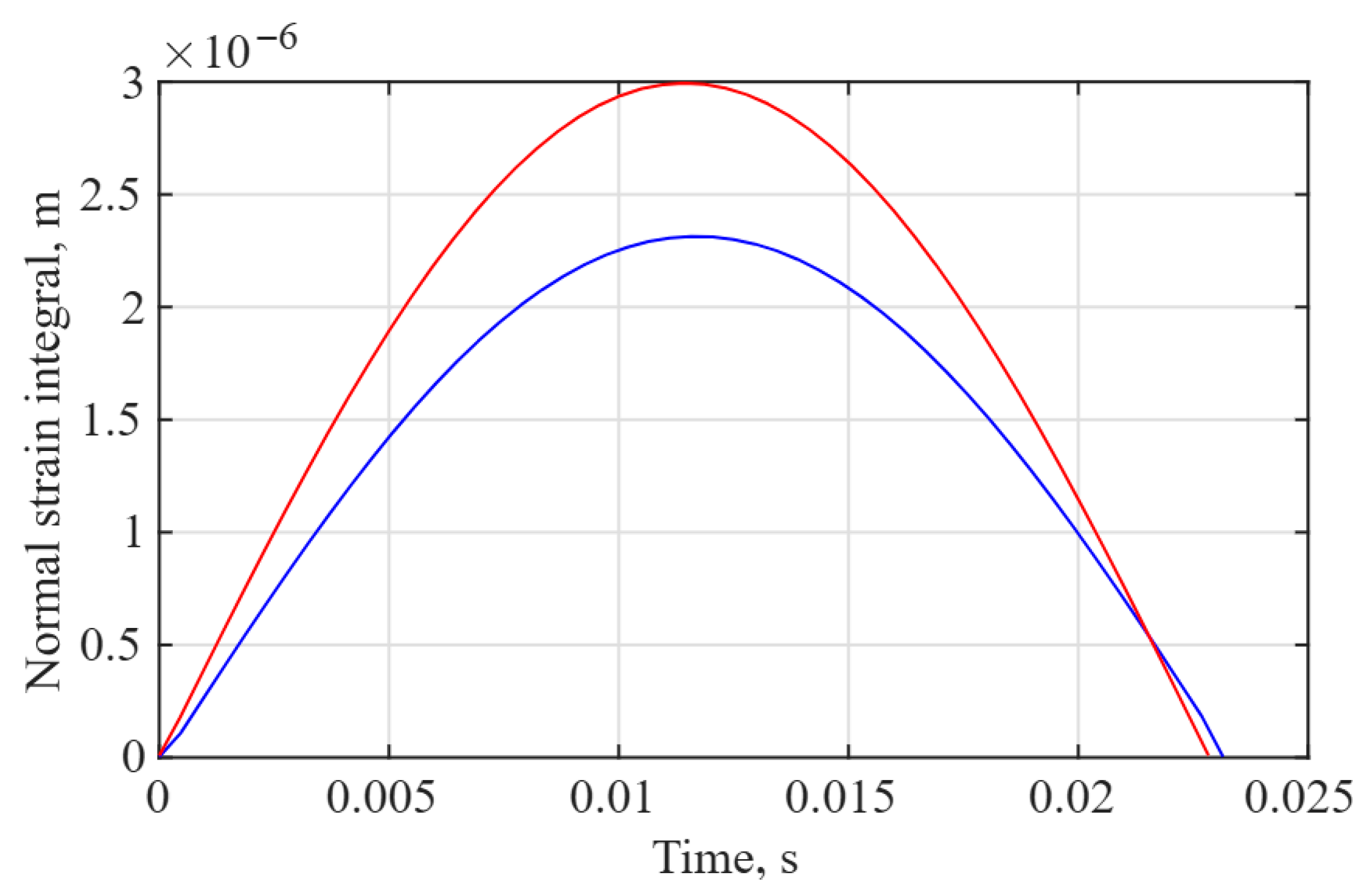

Given the periodic nature of the response in

Figure 8, analysis can be effectively conducted on a half-period of the vibration, as illustrated in

Figure 9.

The total strain generated at the first eigenfrequency during a half period of the vibration can be found by integrating the strain integral curve (

Figure 9) over time. The uniform cantilever generates a strain of 1.70 × 10

−8 ms throughout the half period. The optimized cantilever design generates a strain of 2.18 × 10

−8 ms. This result means that the efficiency of the optimized cantilever design in strain generation is 28.2% greater.

The curves in

Figure 10 correspond to the strain generated at the first eigenfrequency along the length of the cantilevers at time

t = 0.0114 s. The red-filled area shows that the optimized cantilever design generates larger strains within the interval of [0.05 L; 0.61 L]. In the uniform cantilever, some short regions of larger strains are generated within [0.0 L; 0.05 L] near the clamped end and [0.61 L; 1.0 L]. These areas are indicated by the blue colour. The optimized cantilever design produces a strain of 2.99 × 10

−6 m (area below the red line), whereas the uniform cantilever produces a strain of 2.31 × 10

−6 m (area below the blue line).

The same investigation was performed for the cantilever optimized for the second eigenfrequency. The integral value of the normal strain in the upper layer of the cantilever design optimized for the second eigenfrequency obtained from transient analysis is presented in

Figure 11. The blue line represents the uniform cantilever vibrations, and the red line represents the optimized cantilever design vibrations. In this analysis, the cantilevers were kinematically excited at the second eigenfrequency. The normal strain is dimensionless, but after the integration along the cantilever length, the results are obtained in metres. The graph shows the amount of strain generated in the elastic substrate during vibration at the second eigenfrequency. At the second eigenfrequency, a strain node—a point at which the strain mode changes sign—exists; therefore, the normal strain generated by vibrations is reflected in the modulus. The uniform cantilever has a maximum strain integral of 3.6 × 10

−8 m, whereas the optimized cantilever design yields a maximum strain integral of 7.4 × 10

−8 m.

Similarly to the dynamic analysis of the response in

Figure 8 over a single period of the vibrations, analysis of only one half-period of the vibrations, as illustrated in

Figure 12, is feasible.

The total strain generated during the half period of the vibration at the second eigenfrequency can be found by integrating the strain integral curve (

Figure 12) over time. The uniform cantilever generates a strain of 9.17 × 10

−11 ms throughout a half period. The optimized cantilever design generates a strain of 1.56 × 10

−10 ms, meaning that the efficiency of the optimized cantilever design in strain generation is 70.1% greater.

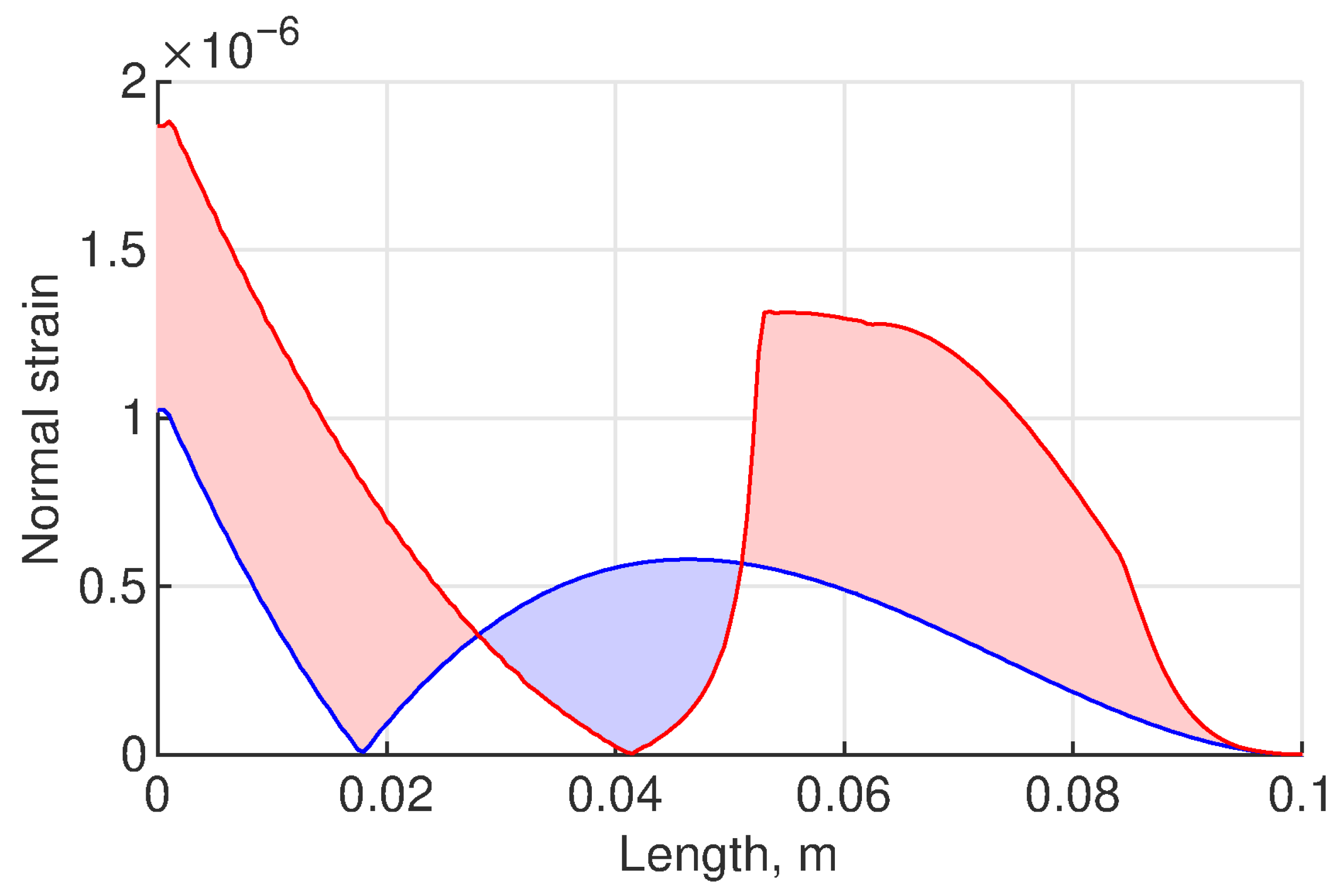

The curves in

Figure 13 correspond to the strain generated at the second eigenfrequency along the length of the cantilevers at time t = 0.94 × 10

−4 s. The red-filled areas show that the optimized cantilever design generates larger amounts of strain within the intervals of [0.0 L; 0.28 L] and [0.51 L; 1.0 L]. The uniform cantilever generates higher strains within the interval of [0.28 L; 0.51 L]. This area is filled with a blue colour. At the second eigenfrequency, there is a strain node—a point at which the strain mode transitions from positive to negative. Thus, the normal strain curves were calculated using the modulus.

Figure 13 clearly shows that the strain node of the uniform cantilever is at 0.18 L, whereas that of the optimized cantilever design is at 0.41 L. The strain node of the optimized cantilever design moves to the right by 0.2 L, which significantly affects the strain increase in the cantilever. The numerical values in the graph show that the left segment of the optimized cantilever (area below the red line up to 0.41 L) generates a strain of 3.2 × 10

−8 m, and the right segment (area below the red line from 0.41 L) generates a strain of 4.04 × 10

−8 m, whereas the left segment of the uniform cantilever (area under the blue line up to 0.28 L) generates a strain of only 8.74 × 10

−9 m, and the right segment (area below the blue line from 0.28 L) generates a strain of 2.7 × 10

−8 m.

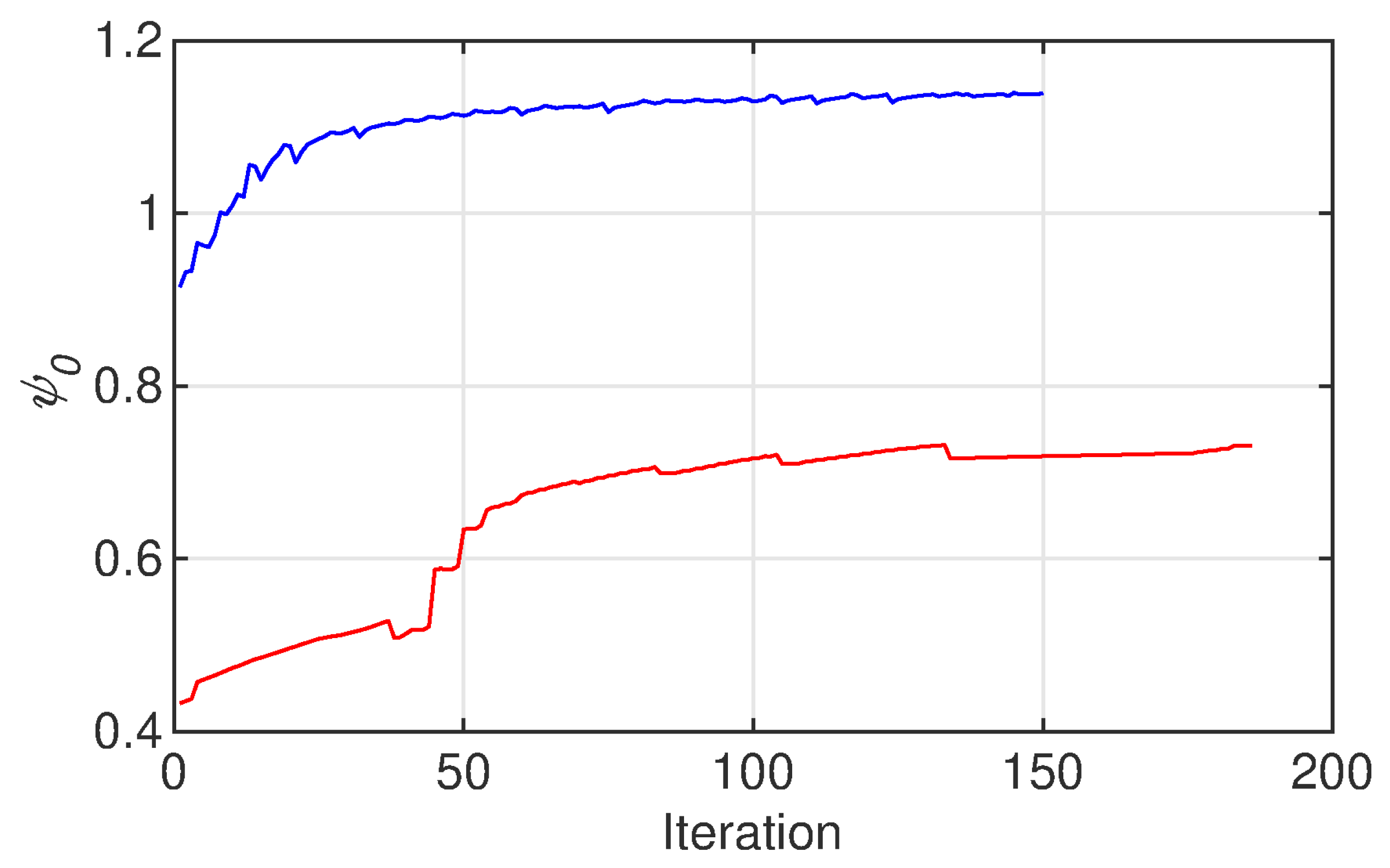

The convergence of the optimization process is important to ensure that accurate results are obtained within a reasonable computation time. The convergence of the optimization process is illustrated in

Figure 14. This figure displays the variation in the objective function with the iteration number during the optimization of the cantilever designs for both the first eigenfrequency (blue) and the second eigenfrequency (red).

For ω1, the process begins with a uniform cantilever strain of 0.92 mm, which then rapidly increases to 1.1 mm at 40 iterations, after which it continues in an approximately straight line until the optimization converges at 150 iterations. This result suggests quick convergence early in the process, with stability and minimal changes beyond 40 iterations. In contrast, for ω2, the process begins at a uniform cantilever strain of 0.44 mm, which gradually increases to 0.52 mm by 40 iterations. A more noticeable jump occurs at 60 iterations, with a strain of 0.68 mm, which eventually reaches 0.7 mm at 80 iterations. From there, the red curve remains approximately steady, continuing in a straight line until it converges at 180 iterations.

Figure 15 shows a graph representing the first eigenfrequencies generated during the optimization process. The variable values are bounded by the dashed red lines.

The objective for state variable ω1 in the cantilever optimization process is to maintain an eigenfrequency of 22 Hz, with the established limits set at 21 Hz and 23 Hz. While some portions of the graph remain within these designated boundaries, there are notable extremes, particularly beginning at approximately 100 iterations. Specifically, three instances are observed in which the eigenfrequency falls below 20 Hz, as are five instances in which it exceeds 24 Hz. Nevertheless, the final 10 iterations demonstrate a high degree of precision, yielding an eigenfrequency of 22.1 Hz at the maximum strain.

The results from optimization of the cantilever of piezoelectric energy harvesters demonstrate notable enhancements in performance. The optimized cantilever designs exhibit preserved eigenfrequencies, with a first eigenfrequency of 22.1 Hz compared with 21.7 Hz for the uniform beam and a second eigenfrequency of 271.4 Hz compared with 271.2 Hz. This minimal deviation in frequencies is crucial, as it confirms that the optimization enhances the original design rather than altering the fundamental characteristics of the beam. The optimized design shows a striking 28.2% increase in strain for the first bending eigenfrequency and a remarkable 70.1% increase for the second eigenfrequency, indicating superior energy harvesting capabilities.

5. Experimental Setup, Results and Discussion

To verify the simulation results, an experiment was conducted. This experiment involved the production of cantilever beam specimens designed in CAD (Autodesk Inventor 2024) on the basis of the FEM results. These models were meticulously crafted to reflect the optimal geometries determined through the cantilever design optimization, ensuring that the physical specimens were closely aligned with the theoretical predictions. Additionally, the experimental procedures for measuring the amplitudes of the specimens are reviewed in this section, highlighting the methodologies employed and the significance of the resulting data in validating the optimized cantilever designs.

The harvester elastic substrate specimens used in the experiment were fabricated using an industrial additive manufacturing machine Form 3 L (Formlabs, Somerville, MA, USA), which was used to precisely create both the uniform and optimized cantilever design models. The same as in the FEM, Engineering Resin Tough 2000, a photopolymer selected for its homogeneous structure and uniform composition (properties detailed in

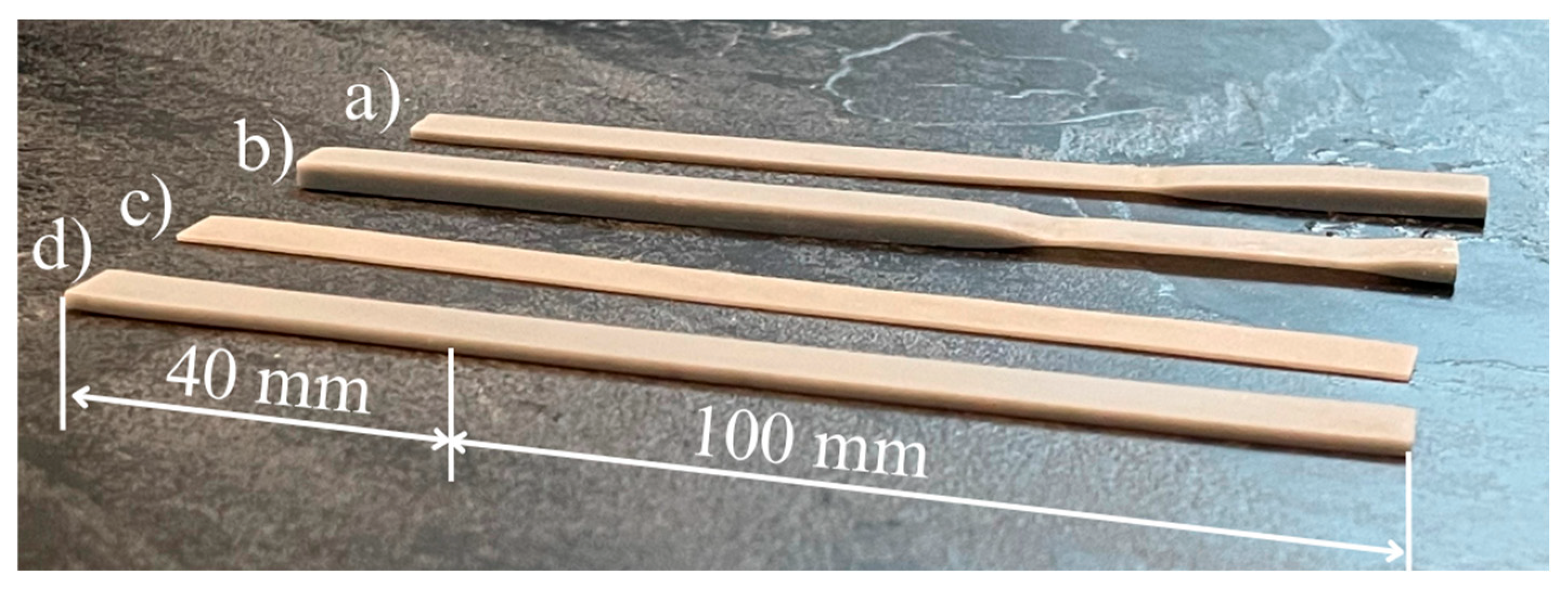

Table 1), was employed in the fabrication process. A single-sided PVDF DT1-028K/L piezoelectric film (PolyK Technologies, LLC, State College, PA, USA) was bonded to the upper surface of the cantilever using an adhesive layer. Thickness of the film is 28 μm. The PVDF layer was used consistently across all tested specimens to ensure comparability between uniform and optimized designs. For second-mode experiments, the PVDF layer was segmented at the experimentally identified strain node locations to prevent electrical charge cancellation. A total of four different cantilever specimens were produced, each with identical dimensions of 100 mm in active length and 10 mm in width but varying in thickness from 0.9 mm to 2.33 mm as extensively described in

Table 2.

Figure 16 shows these manufactured cantilevers.

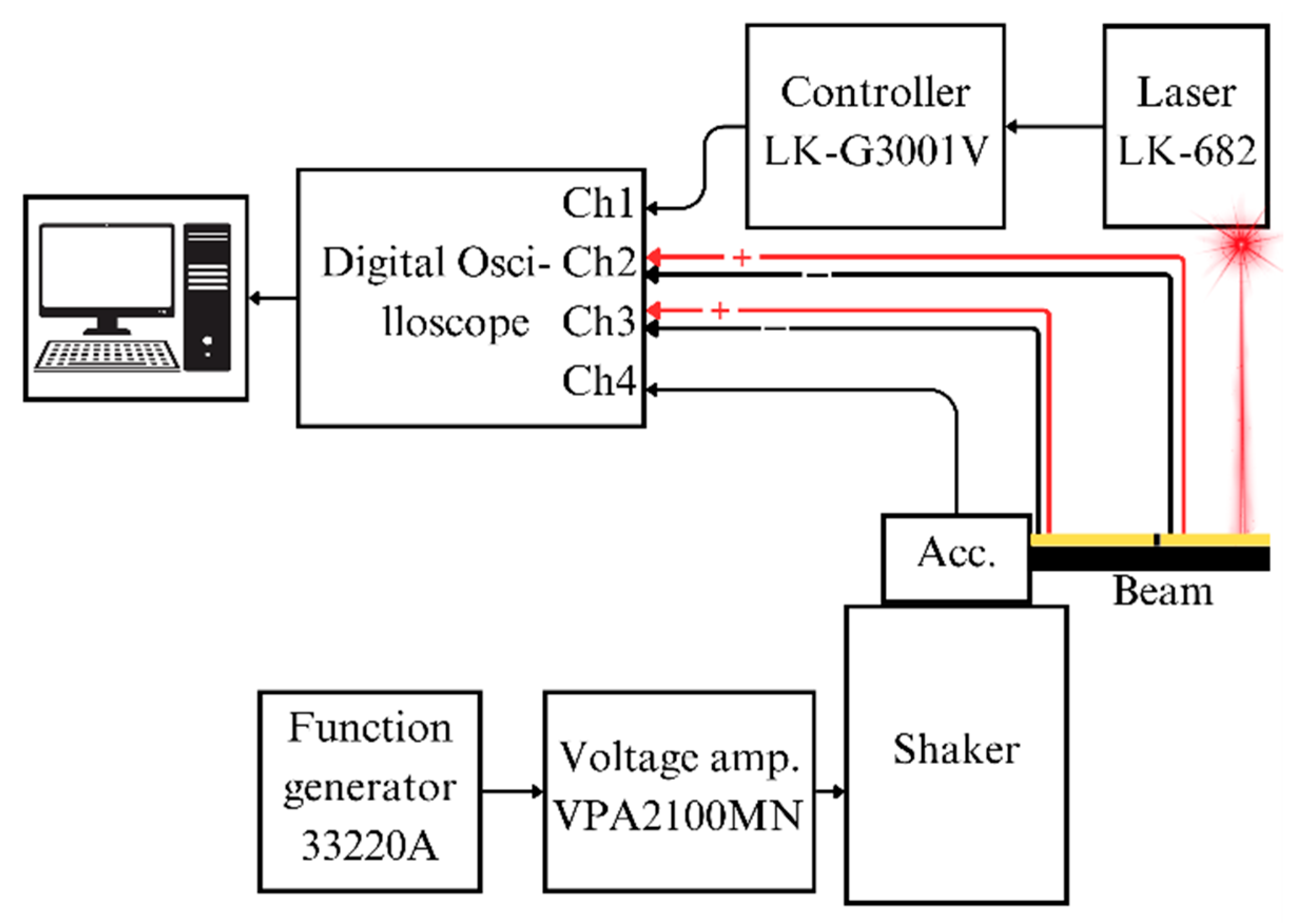

A single-axis KS-93 accelerometer (MMF, Radebeul, Germany), with a sensitivity of 5 mV/(m/s

2), was employed to monitor the excitation amplitudes. Data from the accelerometer, laser controller and piezoelectric sensors were recorded through a 4224 USB oscilloscope (Pico Technology Ltd., St Neots, Cambridgeshire, UK) and analysed on a PC via Picoscope 6.14 software. The sensors were connected to the oscilloscope as follows: channel 1—laser displacement sensor; channel 2—second piezoelectric sensor; channel 3—first piezoelectric sensor; and channel 4—accelerometer. This comprehensive setup enabled precise measurements of the displacement, open-circuit electrical potential and acceleration, facilitating an accurate comparison of the cantilever performance under excitation conditions. The principal experimental scheme is presented in

Figure 17, and a picture of the setup is given in

Figure 18.

The eigenfrequencies obtained through finite element analysis (FEA) and experiments (

Table 2) provide crucial data for validating the FEA model and form a foundation for further analysis of the characteristics of the optimized cantilever designs. The first eigenfrequencies of the uniform cantilever obtained from the simulation and experiment are 21.7 Hz and 21.3 Hz, respectively, representing a difference of 1.88%. Those of the optimized cantilever are 21.2 Hz (simulation) and 20.6 Hz (experiment), reflecting a difference of 2.91%. The simulations and experiments for the uniform cantilever yield second eigenfrequencies of 271.2 Hz (simulation) and 265.5 Hz (experiment), reflecting a difference of 2.64%. For the optimized cantilever, the frequencies are 271.4 Hz (simulation) and 278.3 Hz (experiment), indicating a difference of approximately 2.48%. These results demonstrate that the manufacturing of the specimens and the additional PVDF film have an insignificant effect on the dynamic response.

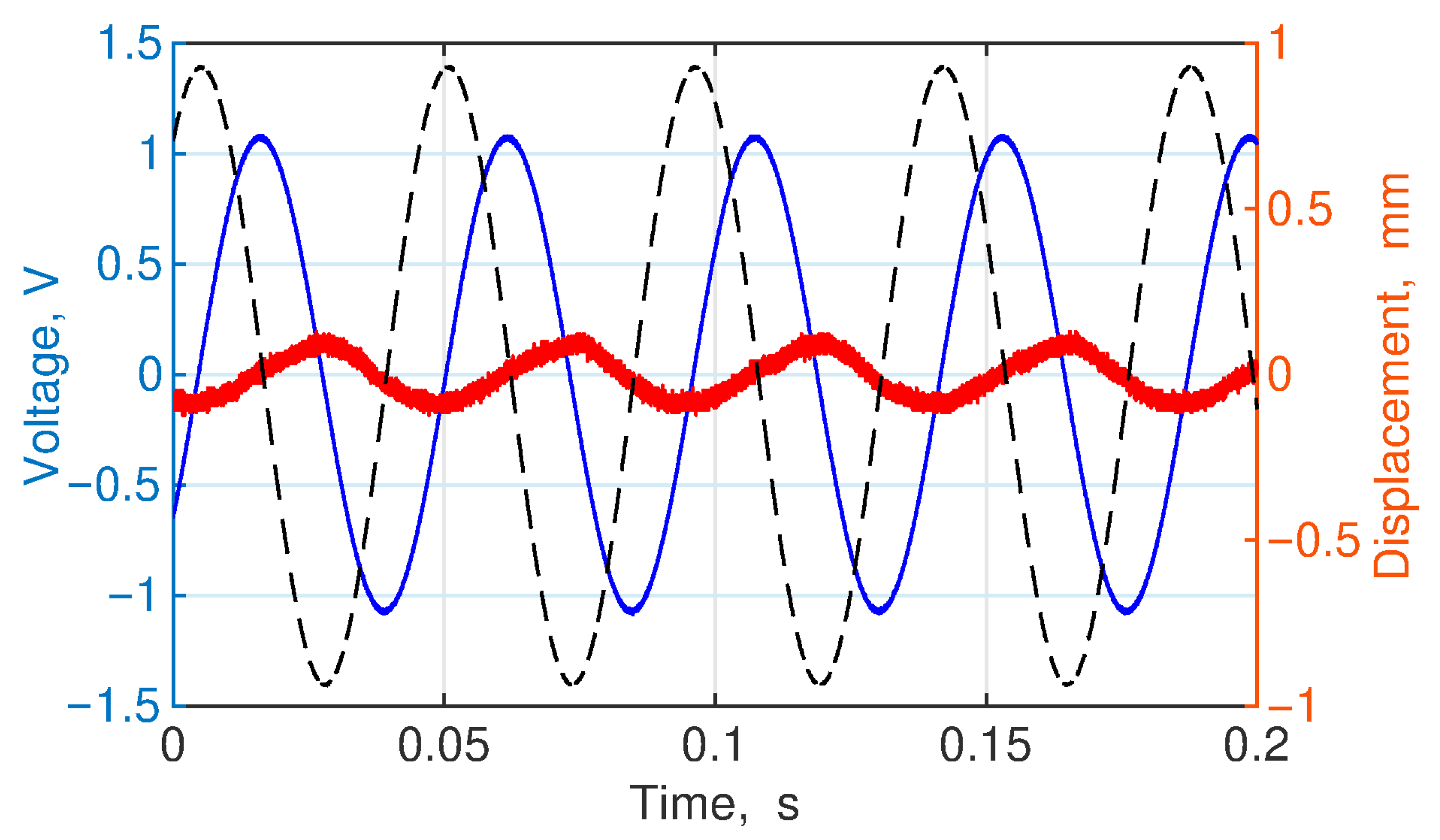

To verify the FEA model, the voltage and displacement of the uniform and optimized cantilevers at the first eigenfrequency were experimentally measured.

Figure 19 and

Figure 20 show the results of the experimental investigation of the uniform and optimized cantilevers at the first eigenfrequency, respectively. Both cantilevers were excited at their eigenfrequency with an acceleration of 14 m/s

2. The optimized cantilever achieved a maximum tip displacement of 1.05 mm, whereas the uniform cantilever reached a displacement of 0.9 mm. The piezo sensor readings indicated an electrical potential of 1.4 V for the optimized cantilever, compared to a value of 1.07 V for the uniform cantilever. Based on linear piezoelectricity theory, mechanical strain in a piezoelectric material generates an electric polarization proportional to the applied strain, meaning that the electrical potential experimentally generated could be compared with the strain obtained from simulations of the same cantilever models depicted in

Figure 10. The simulation of the optimized cantilever resulted in a strain of 2.99 × 10

−6 m, whereas the uniform cantilever generated a strain of 2.31 × 10

−6 m. A comparison of the experimental voltages of the optimal and uniform cantilevers with the corresponding simulated strains revealed a correlation with a 2% deviation. Thus, the simulation results are deemed valid.

A similar experimental verification was conducted with the second eigenfrequency cantilevers.

Figure 21 and

Figure 22 present the results for the uniform and optimized cantilevers, respectively. The PVDF sensors on each cantilever were segmented at the nodes to ensure that the electrical potentials did not cancel each other out. The blue line in the graph represents the output signal from the first clamped-side PVDF sensor, the red line represents the output signal from the sensor closer to the tip of the cantilever, the black line represents the cantilever tip displacement, and the green line represents the excitation acceleration signal.

Both cantilevers were subjected to excitation at their eigenfrequency, with an oscillation acceleration of 14 m/s

2. The cantilever tip displacements were 0.05 mm and 0.1 mm for the uniform and optimized cantilevers, respectively. The first sensor for the uniform cantilever measured an electrical potential of 0.1 V, whereas the second sensor measured a value of 0.31 V. In contrast, the optimized cantilever yielded an electrical potential of 0.62 V from the first sensor and 0.80 V from the second sensor. Since the generated electrical signal is directly proportional to the strain in the upper layer of the cantilever, the experimentally measured electrical potentials of the cantilever from each sensor can be compared with the strains in

Figure 13 of the corresponding cantilever models. The first part of the uniform cantilever resulted in a strain of 8.74 × 10

−9 m, and the second part resulted in a strain of 2.7 × 10

−8 m. A comparison of the ratio of the electrical potentials in the first and second parts to the ratio of the strains in the same parts resulted in a difference of 1%. The same comparison was performed for the optimized cantilever, in which the simulation resulted in a strain of 3.2 × 10

−8 m in the first part and of 4.04 × 10

−8 m in the second part. The ratios align, with a discrepancy of less than 3%, indicating that the FEM results are valid.

A review of the experimental results confirmed the numerical simulation results. The strain generation was verified by the correlation with a 2% margin for the first eigenfrequency and a 3% difference for the second eigenfrequency, confirming the FEM results of approximately 28.8% and 70.1% increases in the strain generation in the upper layer of the cantilever for the first and second eigenfrequency cantilevers, respectively. These findings demonstrate that the proposed simple, yet effective design significantly enhances strain generation and energy harvesting potential, validating the efficiency of the optimization approach described earlier.