Effect of Different Infill Types on the Cyclic Behavior of Steel Plate Shear Walls

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Finite Element Modeling

2.1. Mechanical Properties of Steel Materials

2.2. Modal Analysis and Initial Defect

2.3. Boundary Conditions and History Loading

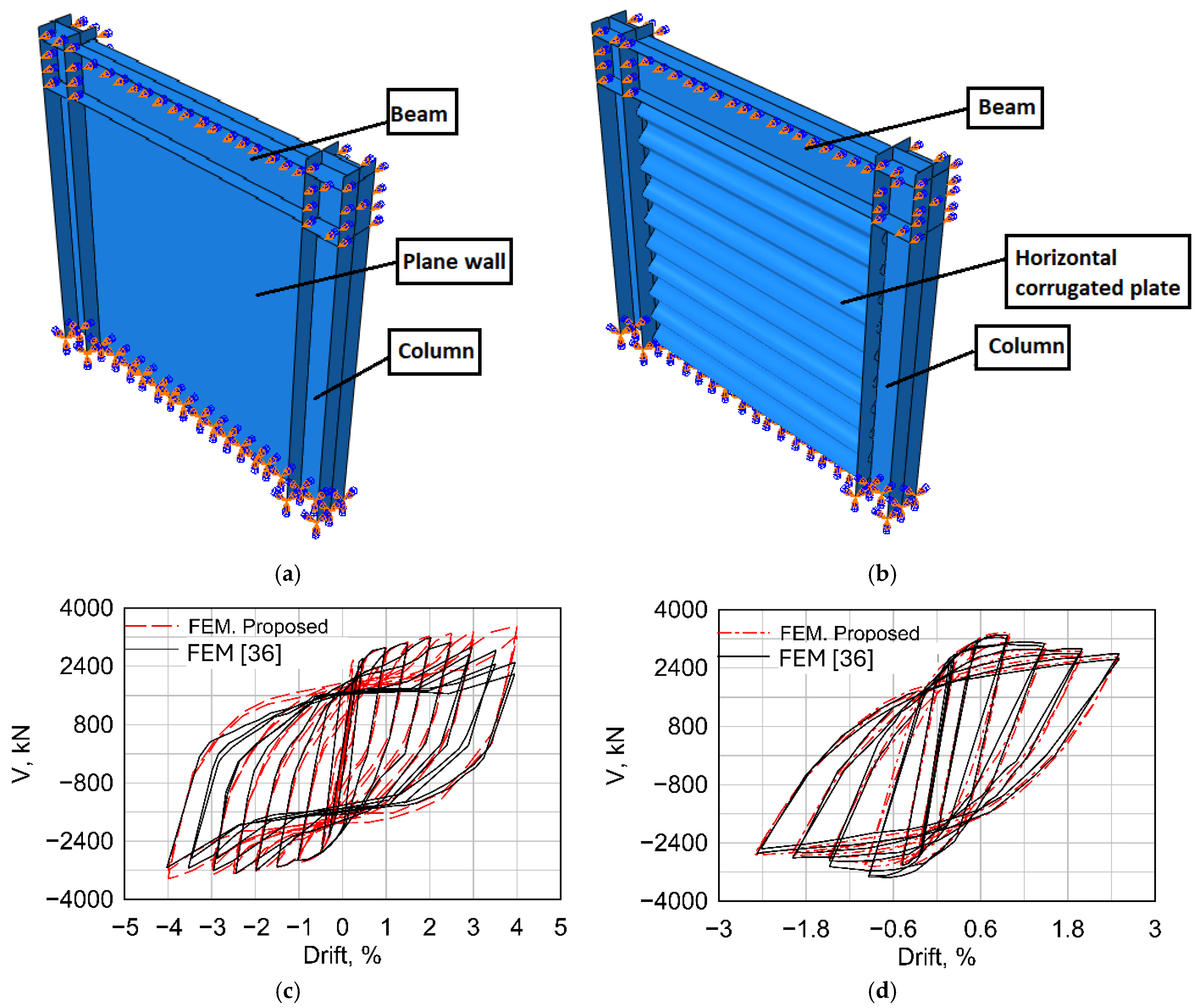

3. Model Validation

3.1. Experimental Validation

3.1.1. Load-Carrying Capacity

3.1.2. Failure Mode

3.2. Numerical Validation

4. Problem Description

- SPt5 and SPt6.75 represent strong-frame plane walls with plate thicknesses of 5 mm and 6.75 mm, respectively.

- SHt5 and SVt5 represent strong-frame walls with horizontal and vertical sinusoidal corrugations, respectively.

- SPt5-HS represents the strong-frame stiffened wall with horizontal stiffeners.The models SPt6.75, SHt5, SVt5, and SPt5-HS were designed to possess the same weight per unit area, enabling a direct comparison of structural efficiency.

- WPt5 represents the weak-frame plane wall.

- WHt5 and WVt5 represent weak-frame walls with horizontal and vertical corrugations, respectively.

- WPt5-HS represents the weak-frame stiffened wall with horizontal stiffeners.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Effect of Panel Type and Direction of Corrugation

5.2. Effect of Boundary Frame Stiffness

5.3. Properties Degradation and Energy Dissipation Capacity

5.4. Comparison Between Systems Mechanisms

5.5. Comparison Between Systems Failure Modes

6. Conclusions

- Accurate finite element models were developed and validated against published experimental and numerical benchmarks, achieving a predictive error within 4%. The analysis revealed that a HCSPSW exhibits 15% and 11% higher stiffness at 0.5% drift in the push and pull directions, respectively, and dissipates 29% more energy than an unstiffened wall (USPSW). The HCSPSW also showed approximately 4.3% greater load capacity than a vertically corrugated wall (VCSPSW) in the pull direction, while the VCSPSW itself demonstrated 32% higher energy dissipation than the USPSW.

- At 0.5% drift, a stiffened wall (SSPSW) with U120 stiffeners showed 9.2% greater stiffness than a USPSW. The SSPSW achieved 23% and 24.5% higher lateral strength than the USPSW and 34.6% and 23.7% higher strength than the HCSPSW in the push and pull directions, respectively. Its energy dissipation exceeded that of the USPSW by about 50%. The USPSW was found to be more sensitive to reductions in boundary frame stiffness than CSPSWs, and the VCSPSW was less sensitive to weaker frames than the HCSPSW.

- For equivalent infill weight per unit area, the SSPSW configuration demonstrated superior overall seismic performance, with a load-carrying capacity approximately 14% and 24% higher than the USPSW and CSPSW, respectively. Therefore, the SSPSW system is recommended over USPSW and CSPSW systems to enhance the seismic resilience of buildings.

- For practical engineering application, a performance-based selection guideline is proposed: USPSWs may be suitable for low drift demands (up to 0.5%), CSPSWs for medium drifts (0.5–1%), and SSPSWs for high cyclic drift levels where maximum strength and energy dissipation are critical.

7. Limitations and Future Work

- The effects of loading rate, strain-rate sensitivity, and seismic spectral characteristics are not addressed herein. Future studies incorporating dynamic loading conditions, such as shake-table testing or nonlinear time-history analyses under recorded ground motions, are recommended to extend the applicability of the findings to realistic seismic responses.

- Future studies will consider more advanced constitutive models, such as combined isotropic–kinematic hardening formulations, to improve the accuracy of cyclic response simulation.

- A comprehensive parametric study considering different wavelengths and amplitudes of sinusoidal corrugation will be conducted. Since the performance of corrugated plates is highly sensitive to these geometric parameters.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Youssef, N.; Wilkerson, R.; Fischer, K.; Tunick, D. Seismic Performance of a 55-Storey Steel Plate Shear Wall. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2010, 19, 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, M.; Bagchi, A. Seismic Performance of a 20-Story Steel-Frame Building in Canada. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2010, 19, 901–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiei, S.; Hossain, K.M.A.; Lachemi, M.; Behdinan, K. Profiled Sandwich Composite Wall with High Performance Concrete Subjected to Monotonic Shear. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2015, 107, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSI/AISC 341-16; Seismic Provisions for Structural Steel Buildings. AISC: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016.

- Caccese, V.; Elgaaly, M.; Chen, R. Experimental Study of Thin Steel-Plate Shear Walls under Cyclic Load. J. Struct. Eng. 1993, 119, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.C.; Hao, J.P.; Liu, Y.H. Behavior of Stiffened and Unstiffened Steel Plate Shear Walls Considering Joint Properties. Thin-Walled Struct. 2015, 97, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yang, W.; Shi, Y.; Xu, J. Seismic Behaviors of Steel Plate Shear Wall Structures with Construction Details and Materials. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2015, 107, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Tan, P.; Lin, Y.; Mercan, O.; Zhou, F.; Li, Y. Theoretical and Experimental Investigations of Steel Plate Shear Walls with Diamond Openings. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 189, 110838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, S.; Yoo, M.; Lee, S. An Experimental Study on the Shear Hysteresis and Energy Dissipation of the Steel Frame with a Trapezoidal-Corrugated Steel Plate. Materials 2017, 10, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vian, D.; Bruneau, M.; Tsai, K.C.; Lin, Y.-C. Special Perforated Steel Plate Shear Walls with Reduced Beam Section Anchor Beams. I: Experimental Investigation. J. Struct. Eng. 2009, 135, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorburn, L.J.; Kulak, G.L.; Montgomery, C.J. Analysis of Steel Plate Shear Walls; Structural Engineering, Report No. 107; Department of Civil Engineering, University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Alavi, E.; Nateghi, F. Experimental Study on Diagonally Stiffened Steel Plate Shear Walls with Central Perforation. J. Constr. Steel Res 2013, 89, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, R.G.; Kulak, G.L.; Kennedy, D.J.L.; Elwi, A.E. Cyclic Test of Four-Story Steel Plate Shear Wall. J. Struct. Eng. 1998, 124, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Fan, J.; Liu, X.; Huang, Y. Comparative Study on Steel Plate Shear Walls Used in a High-Rise Building. J. Struct. Eng. 2013, 139, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitaka, T.; Matsui, C. Experimental Study on Steel Shear Wall with Slits. J. Struct. Eng. 2003, 129, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.J.; Jhang, C. Experimental Study of Low-Yield-Point Steel Plate Shear Wall under in-Plane Load. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2011, 67, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, H.; Li, Z.-M.; Li, Z.-J.; Chen, X.-F.; Ding, L. Cyclic Test of Diagonally Stiffened Steel Plate Shear Wall. Xi’an Jianzhu Keji Daxue Xuebao/J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. 2009, 41, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Alinia, M.M.; Dastfan, M. Cyclic Behaviour, Deformability and Rigidity of Stiffened Steel Shear Panels. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2007, 63, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.-R.; Park, H.-G. Steel Plate Shear Walls with Various Infill Plate Designs. J. Struct. Eng. 2009, 135, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shallan, O.; Maaly, H.; Elgiar, M.; Elsisi, A. Effect of Stiffener Characteristics on the Seismic Behavior and Fracture Tendency of Steel Shear Walls. Frat. Integrità Strutt. 2020, 14, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paslar, N.; Farzampour, A.; Hatami, F. Infill Plate Interconnection Effects on the Structural Behavior of Steel Plate Shear Walls. Thin-Walled Struct. 2020, 149, 106621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmohammadi, A.; Mirghaderi, R.; Hajsadeghi, M.; Khanmohammadi, M. Application of Corrugated Plates as the Web of Steel Coupling Beams. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2013, 85, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Berdichevsky, V.L.; Yu, W. An Equivalent Classical Plate Model of Corrugated Structures. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2014, 51, 2073–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Gil, H.; Youm, K.; Lee, H. Interactive Shear Buckling Behavior of Trapezoidally Corrugated Steel Webs. Eng. Struct. 2008, 30, 1659–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Yi, J.W.; Choi, B.H.; Lee, H.E. Lateral-Torsional Buckling of I-Girder with Corrugated Webs under Uniform Bending. Thin-Walled Struct. 2009, 47, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.K.; Elsisi, A. Cyclic Performance of Corrugated Steel Plate Shear Walls with Openings. Master’s Thesis, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, Edwardsville, IL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Emami, F.; Mofid, M. On the Hysteretic Behavior of Trapezoidally Corrugated Steel Shear Walls. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2014, 23, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrebar, M.; Kabir, M.Z.; Zirakian, T.; Hajsadeghi, M.; Lim, J.B.P. Structural Performance Assessment of Trapezoidally-Corrugated and Centrally-Perforated Steel Plate Shear Walls. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2016, 122, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, C.; Jiang, Z.Q.; Pi, Y.L.; Guo, Y.L. Elastic Shear Buckling of Sinusoidally Corrugated Steel Plate Shear Wall. Eng. Struct. 2016, 121, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessler, A.; Spiridigliozzi, L. Resolving Membrane and Shear Locking Phenomena in Curved Shear-deformable Axisymmetric Shell Elements. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 1988, 26, 1071–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassault Systèmes ABAQUS 6.14 Analysis User’s Guide. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/517828704/Analysis-4 (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Shi, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y. Experimental and Constitutive Model Study of Structural Steel under Cyclic Loading. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2011, 67, 1185–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, H.; Ahmadi, J.; Kazemi, F. Enhancing Seismic Resilience in Steel Frames with Synchronized Double-Stage Yield Buckling-Restrained Braces. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 198, 109587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.G.; Zhu, L.; Tao, M.X.; Tang, L. Shear Strength of Trapezoidal Corrugated Steel Webs. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2013, 67, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-G.; Kwack, J.-H.; Jeon, S.-W.; Kim, W.-K.; Choi, I.-R. Framed Steel Plate Wall Behavior under Cyclic Lateral Loading. J. Struct. Eng. 2007, 133, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Sun, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Z. Cyclic Analyses of Corrugated Steel Plate Shear Walls. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2017, 26, e1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaboche, J.L. Time-Independent Constitutive Theories for Cyclic Plasticity. Int. J. Plast. 1986, 2, 149–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaboche, J.L. Constitutive Equations for Cyclic Plasticity and Cyclic Viscoplasticity. Int. J. Plast. 1989, 5, 247–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.W.; Kim, H.T.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, J.W. Determination of Combined Hardening Parameters to Simulate Deformation Behavior of C(T) Specimen under Cyclic Loading. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2018, 13, 1932–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sisi, A.A.; Elgiar, M.M.; Maaly, H.M.; Shallan, O.A.; Salim, H.A. Effect of Welding Separation Characteristics on the Cyclic Behavior of Steel Plate Shear Walls. Buildings 2022, 12, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabelli, R.; Bruneau, M. Steel Plate Shear Walls (Steel Design Guide 20); American Institute of Steel Construction, Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ANSI/AISC 341-10; Seismic Provisions for Structural Steel Buildings. American Institute of Steel Construction: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010.

- Nie, J.; Qin, K.; Cai, C.S. Seismic Behavior of Connections Composed of CFSSTCs and Steel-Concrete Composite Beams-Experimental Study. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2008, 64, 1178–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value, N/mm2 | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q∞ | 21 | b | 1.2 |

| C1 | 7993 | γ1 | 175 |

| C2 | 6773 | γ2 | 116 |

| C3 | 2854 | γ3 | 34 |

| C4 | 1450 | γ4 | 29 |

| Group # | Notation | Wall Type | Thickness (mm) | Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S * | SPt6.75 | Plane | 6.75 | Infill type |

| SPt5 | Plane | 5 | ||

| SHt5 | H-Corrugated | |||

| SVt5 | V-Corrugated | |||

| SPt5-HS | Plane | |||

| W ** | WHt5 | H-Corrugated | Boundary Stiffness | |

| WVt5 | V-Corrugated | |||

| WPt5 | Plane | |||

| WPt5-HS | Plane |

| Model | Direction | K1 (kN/mm) | K2 (kN/mm) | Δy (mm) | Vy (kN) | Δm (mm) | Vm (kN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPt5 | push − | 300.8 | 152.13 | 16.3 | 2479.5 | 130 | 3267.17 |

| pull + | 299.9 | 158.1 | 16.3 | 2855.2 | 130 | 3203.4 | |

| SPt6.75 | push − | 369.7 | 186.88 | 16.3 | 2433 | 130 | 3511.95 |

| pull + | 369.25 | 196.16 | 16.3 | 3521.3 | 130 | 3507.93 | |

| SHt5 | push − | 275.49 | 174.4 | 16.3 | 2823.95 | 32.5 | 2984.27 |

| pull + | 275.492 | 175.57 | 16.3 | 2823 | 32.5 | 3225.2 | |

| SVt5 | push − | 271.83 | 175.85 | 8.1 | 2208.7 | 32.5 | 3042.45 |

| pull + | 271.93 | 173.8 | 16.3 | 2812.1 | 32.5 | 3093.0 | |

| SPt5-HS | push − | 303.17 | 166.18 | 8.1 | 2472.1 | 130 | 4016.8 |

| pull + | 302 | 162.6 | 8.1 | 2463.2 | 130 | 3989.5 |

| Model | Direction | Ki (kN/mm) | K2 (kN/mm) | Δy (mm) | Vy (kN) | Δm (mm) | Vm (kN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPt5 | push − | 300.8 | 152.1 | 16.3 | 2479.5 | 130 | 3267.1 |

| pull + | 299.9 | 158.08 | 16.3 | 2855.2 | 130 | 3203.3 | |

| WPt5 | push − | 287.05 | 127.5 | 8.1 | 2326.8 | 130 | 2673.05 |

| pull + | 286.30 | 126.3 | 8.1 | 2332.2 | 130 | 2686.04 | |

| SHt5 | push − | 275.49 | 174.4 | 16.3 | 2823.95 | 32.5 | 2984.27 |

| pull + | 275.49 | 175.57 | 16.3 | 2823 | 32.5 | 3225.2 | |

| WHt5 | push − | 258.34 | 161.697 | 8.1 | 2099 | 16.25 | 2627.59 |

| pull + | 258.36 | 163 | 16.3 | 2626.4 | 32.5 | 2788.6 | |

| SVt5 | push − | 271.83 | 175.85 | 8.1 | 2208.7 | 32.5 | 3042.45 |

| pull + | 271.93 | 173.8 | 16.3 | 2812.1 | 32.5 | 3093.04 | |

| WVt5 | push − | 256.09 | 163.8 | 16.3 | 2648.8 | 32.5 | 2697.0 |

| pull + | 256.19 | 162.5 | 16.3 | 2625.6 | 32.5 | 2735.0 | |

| SPt5-HS | push − | 303.1 | 166.18 | 8.1 | 2472.1 | 130 | 4016.79 |

| pull + | 302 | 162.6 | 8.1 | 2463.2 | 130 | 3989.5 | |

| WPt5-HS | push − | 289.29 | 152.7 | 16.3 | 2480 | 130 | 3383.4 |

| pull + | 288.2 | 157.0 | 16.3 | 2701 | 130 | 3429.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Elgiar, M.M.; Elsisi, A.A.; Maaly, H.M.; Shallan, O. Effect of Different Infill Types on the Cyclic Behavior of Steel Plate Shear Walls. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020759

Elgiar MM, Elsisi AA, Maaly HM, Shallan O. Effect of Different Infill Types on the Cyclic Behavior of Steel Plate Shear Walls. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):759. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020759

Chicago/Turabian StyleElgiar, Mohammed M., Alaa A. Elsisi, Hassan M. Maaly, and Osman Shallan. 2026. "Effect of Different Infill Types on the Cyclic Behavior of Steel Plate Shear Walls" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020759

APA StyleElgiar, M. M., Elsisi, A. A., Maaly, H. M., & Shallan, O. (2026). Effect of Different Infill Types on the Cyclic Behavior of Steel Plate Shear Walls. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020759