1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation and Problem Statement

Road traffic crashes remain one of the leading causes of injury and fatality worldwide, and a significant proportion of these accidents are attributable to human factors such as driver fatigue, distraction, or impaired vigilance under adverse visibility conditions (e.g., night-driving, fog, glare). In-vehicle driver state monitoring systems (DMS) have therefore gained increased attention as a countermeasure to mitigate such risks. For example, a recent scoping review concluded that while DMS technologies have advanced, considerable gaps remain regarding how interventions affect long-term driver behavior and attention recovery [

1].

Meanwhile, visibility degradation (due to lighting, weather, or sensor limitations) poses a major challenge to vision-based safety systems because conventional cameras and perception modules suffer reduced reliability in low-visibility scenarios. A systematic review of critical scenarios in autonomous vehicles highlights that weather conditions, lighting, environmental factors and infrastructure deficiencies significantly degrade the performance of sensing and perception systems [

2].

Together, these two threads—driver state monitoring and low-visibility hazard perception—point to a pressing need for embedded, low-latency, robust systems that operate effectively in real-world driving conditions including poor visibility and varying driver states (fatigue, distraction, inattention).

In this work, the term low-visibility hazard detection refers specifically to identifying environmental conditions—fog, glare, night, and low illumination—that elevate collision risk or degrade downstream perception performance. It does not refer to object-level hazard detection (e.g., pedestrians, animals, debris). Instead, the system estimates a visibility-related hazard context that can be consumed by external ADAS perception modules.

1.2. Research Challenges and Gap

From a technical standpoint, several challenges hamper current solutions. First, addressing driver state (e.g., drowsiness, distraction) often relies on rich sensor suites (infrared cameras, physiological sensors) or compute-intensive AI models, which may not be suitable for deployment on constrained automotive or edge hardware. For instance, the review by Al-Quraishi et al. on driver state detection reports that many techniques focus on accuracy improvements, but less attention is given to real-time, resource-limited deployment [

3].

Second, the estimation of visibility-related hazard conditions (rather than object hazards) remains under-explored, even though poor illumination and atmospheric scattering severely degrade conventional perception systems. Many perception systems degrade in fog, rain, or night conditions, and sensor fusion or robust signal-processing approaches are required to compensate. The review of environmental and infrastructural effects on automated vehicles underscores this point [

2].

Third, the required convergence of multimodal data (e.g., camera, inertial sensors, physiological signals) and the fusion of temporal–spatial features presents design complexity: balancing robustness, detection latency, model size, power consumption, and cost. Additionally, while many DMS studies focus on driver–vehicle monitoring, fewer explicitly target integrated frameworks that merge driver state, external hazard detection, and embedded deployment in a unified system. This gap suggests there is an opportunity for approaches that combine signal-processing fundamentals, efficient Edge AI design, and vision/hazard perception under challenging visibility.

1.3. Contribution and Novelty

In this paper we propose Edge-VisionGuard, a lightweight signal-processing plus Edge AI framework for driver state monitoring and low-visibility hazard detection. The key contributions are as follows:

A multi-modal sensor architecture integrating a driver-facing camera, inertial measurement unit (IMU), and ambient-light sensor to jointly estimate driver vigilance/attention state and visibility-related hazard conditions (fog, glare, night, low illumination).

A hybrid temporal–spatial feature extractor leveraging optimized B-spline reconstruction filters and depthwise/pointwise convolutional layers to handle temporal drifts and illumination changes, enabling robust detection in low-visibility scenarios.

Model compression strategies (pruning, 8-bit quantization) enabling deployment on resource-constrained automotive-grade hardware with low latency and power overhead.

An experimental validation using both publicly available driving/driver-state datasets and a virtual reality (VR)-based driving simulation with controlled low-visibility conditions, demonstrating performance improvements in latency (~17% reduction) and recall (~12% improvement) over baseline methods.

This work addresses the identified gap by providing an end-to-end system focused on embedded deployment, bridging driver monitoring, visibility-condition estimation, and real-time edge performance, providing a contextual hazard-awareness layer that can support downstream ADAS perception modules.

1.4. Paper Organization

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews prior work on driver state monitoring, low-visibility hazard detection, and Edge AI in automotive systems.

Section 3 presents the design of the Edge-VisionGuard framework, including sensor architecture, feature extraction, model compression, and deployment strategy.

Section 4 describes the experimental setup, datasets, VR simulation environment, evaluation metrics, and results.

Section 5 discusses the findings, limitations, and potential for real-world integration and the future work, while

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Driver State Monitoring (DSM)

Driver state monitoring (DSM) refers to the continuous assessment of the driver’s internal state (e.g., fatigue, distraction, inattention) and is widely recognized as a pivotal component of modern vehicle safety. Studies estimate that driver fatigue and distraction contribute to a substantial portion of road incidents, prompting the development of camera-based, physiological, and vehicle-sensor-based monitoring systems. For example, Ayas et al. present a scoping review that emphasizes how wearable and non-wearable sensors are used for fatigue/drowsiness detection but also highlight the need for long-term behavior studies beyond short-term accuracy evaluation [

1].

Al-Quraishi M. S. et al. compile recent technologies for driver state detection, showing that while the number of modalities used (camera, IMU, ECG, EEG) has grown, the deployment on resource-limited hardware remains under-investigated [

3].

A further dimension is the regulatory push: new vehicle safety frameworks (e.g., in Europe) are increasingly mandating or rating DSM systems as part of occupant safety. Visconti and De Fazio (2025) discuss the design of on-board vehicle devices in a “smart-road” scenario, emphasizing that DSM must interface with vehicle and infrastructure data for holistic safety [

4].

Empirical work confirms the effect of DSM interventions: a recent study examined the effect of attentional warnings triggered by a DSM and found that such systems can influence driver behavior, yet they also note that human adaptation and long-term compliance remain open issues [

5].

Despite these advances, several gaps remain: (i) many studies focus on accuracy under ideal conditions (good lighting, controlled simulator), (ii) there is limited work on embedded/edge deployment of DSM models with latency/power constraints, and (iii) fewer works address the coupling of driver state with external hazard perception (especially under low-visibility). These gaps motivate our framework’s focus on lightweight, integrated driver monitoring under challenging conditions.

2.2. Low-Visibility/Hazard Detection and Perception in Driving Environments

Hazard detection for driving safety traditionally emphasizes external perception—for example object detection, obstacle avoidance, scene understanding—but performance under low-visibility conditions (night, fog, glare, shadows) remains a significant challenge. Xu et al. (2024) published a comprehensive review of autonomous driving algorithms, noting that perception models degrade significantly in adverse weather/lighting, and robust solutions remain an active research area [

6].

Similarly, Rahmani S. et al. (2024) conducted a systematic review of “edge case detection” in automated driving, highlighting that rare but safety-critical visibility scenarios (e.g., sudden glare, heavy fog) are under-represented in datasets and model evaluations [

7].

On the implementation side, frameworks such as the “cloud–edge collaborative object detection” approach by Li X. et al. (2024) show how adverse weather conditions can be mitigated by dynamic allocation of compute and sensor fusion across modalities [

8].

Furthermore, the industry commentary confirms that these perception challenges are being actively addressed: for example, an industry analysis of ADAS predicted that embedded AI will play a crucial role in low-visibility hazard perception [

9].

Nevertheless, the research gap persists: most perception models are validated in clear-weather datasets; there is limited exploration of combined driver-state and external-hazard monitoring under low-visibility; and few solutions are optimized for resource-constrained, real-time, in-vehicle edge deployment. In our work, we target exactly these intersecting challenges.

2.3. Edge AI, Embedded Deployment, and Multi-Modal Fusion for Automotive Safety

As vehicles evolve into intelligent and connected platforms, Edge AI—that is, performing inference locally on the vehicle rather than relying solely on cloud compute—has emerged as a key enabler of low-latency, privacy-preserving, and robust automotive intelligence. A recent McKinsey article observed that edge-based AI in automotive systems is being driven by the need to reduce data traffic and network dependence and ensure decision-making under connectivity constraints [

10].

In academic terms, Shankar (2025) released a survey on Edge AI technologies and applications, documenting architectures (client/server, hierarchical, federated), frameworks (PyTorch Mobile—version 2.9.1, ONNX—v1.20.0, TensorFlow Lite—2.20.0), and noting that automotive deployments remain a smaller subset of Edge AI research [

11].

A taxonomy also emphasizes the rapid growth of Edge AI research and flags that “multi-modality, federated learning, model compression and resource-aware designs” remain major open avenues [

12].

Edge AI is not just about inference: Katariya V. highlights how Edge AI accelerators (ASICs, NPUs) for automotive applications are projected to support driver monitoring, real-time perception, and ADAS functionality, underpinning the hardware side of deployment [

13].

On the fusion side, recent multimodal DSM research—e.g., Ma Y. et al.—propose a multiview multimodal driver monitoring system using masked multi-head self-attention that fuses camera, pose, and vehicle interior data, achieving high AUC in simulated settings [

14].

Yet, from a system perspective, there remains a scarcity of integrated frameworks that (i) fuse driver state and environment/visibility hazard data, and (ii) run on lightweight, edge-embedded hardware with latency/power constraints. That is precisely the niche that our proposed Edge-VisionGuard framework addresses.

These multi-modal DSM systems are therefore used as functional baselines in some of the tables presented below, while single-stream CNNs serve as lightweight computational comparators.

2.4. Summary of Gaps

In summary:

DSM research has matured in sensing and algorithms, but is less strong in embedded deployment, long-term driver behavioral adaptation, and coupling with external hazard detection.

Hazard perception (especially low-visibility scenario) remains a critical but under-explored domain, particularly in terms of real-time embedded fusion of driver and external states.

Edge AI research and market momentum are strong, yet fewer academic works show full end-to-end systems combining driver-state monitoring, visibility/hazard detection and resource-aware embedded design.

These observations clearly point to a gap for a lightweight, multi-modal, Edge AI framework that unifies driver state and hazard perception under low visibility, which is the objective of our proposed framework.

3. Proposed Framework: Edge-VisionGuard

3.1. System Overview

The proposed Edge-VisionGuard framework integrates driver-state monitoring and low-visibility hazard detection into a unified architecture designed for real-time edge deployment in intelligent vehicles. The system aims to ensure driving safety through simultaneous perception of both internal (driver state) and external (visibility and hazard) conditions.

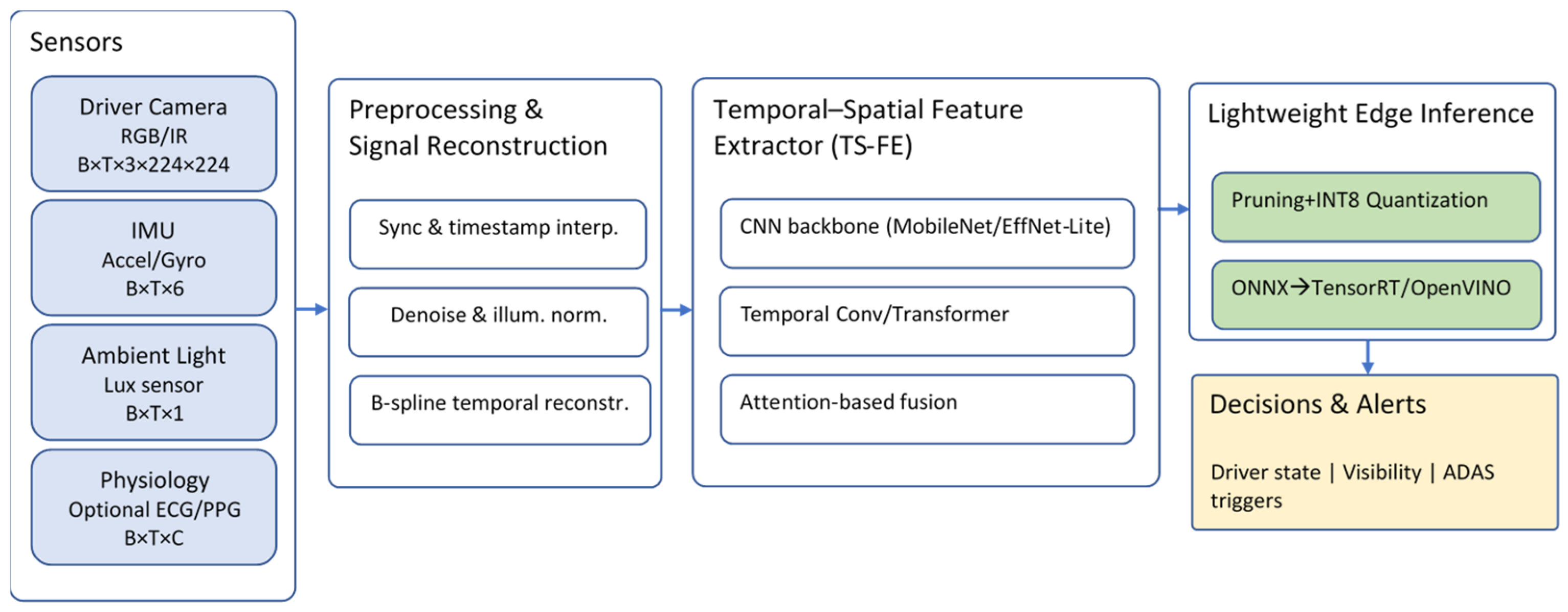

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the framework consists of five major components:

Multi-modal sensor acquisition, including a driver-facing RGB/IR camera, an inertial measurement unit (IMU), and an ambient-light sensor;

Signal-processing and reconstruction modules for noise reduction and illumination normalization;

A temporal–spatial feature extractor (TS-FE) for joint feature learning from multi-modal signals;

A lightweight Edge AI inference engine, optimized for embedded deployment via pruning and quantization;

A decision and alert subsystem that provides driver warnings or triggers advanced driver-assistance system (ADAS) actions.

The framework targets automotive-grade embedded platforms such as NVIDIA Jetson Nano/Xavier, NXP BlueBox, or Raspberry Pi 5 with an Edge TPU. The design goals are as follows:

Robustness under diverse illumination and visibility conditions (day, night, fog, glare);

Real-time processing (<30 ms latency per frame);

Low power consumption (<10 W average);

Model compactness (≤50 MB total size);

Seamless fusion of internal and external states for actionable insights.

The proposed design directly addresses the challenges outlined in

Section 2: namely, the absence of lightweight, real-time, and low-visibility-aware systems that unify driver monitoring and hazard detection.

3.2. Preprocessing and Signal Reconstruction

The signal-processing stage is responsible for cleaning, synchronizing, and reconstructing raw sensor data before feature extraction.

3.2.1. Data Acquisition and Synchronization

Multi-modal streams—video frames (RGB or IR), IMU sequences, and ambient-light intensity—are first temporally synchronized using timestamp interpolation. Although automotive-grade sensors connected through GMSL or CAN typically provide highly stable clocking, low-cost IMUs and ambient-light sensors frequently used in aftermarket DSM systems—as well as our VR-based synthetic data generator—exhibit measurable timestamp jitter, clock drift, and occasional sample dropouts. To account for these irregularities, the system incorporates a nonuniform-sampling reconstruction strategy inspired by generalized sampling theory. Importantly, this reconstruction is applied only to sensor streams in which timestamp variability is empirically detected, rather than assumed for all automotive configurations.

3.2.2. B-Spline Temporal Reconstruction

To recover smooth temporal trajectories from noisy or partially missing data, the system applies cubic B-spline interpolation filters to IMU and brightness sequences. These filters reconstruct continuous-time signals from irregularly spaced samples and provide stable derivative estimates required for motion interpretation. Compared with simpler interpolation methods, B-splines offer improved local smoothness, reduced amplification of sensor noise, and robustness under timestamp jitter.

In the VR simulation, the 0.8 s eye-closure threshold served only to bootstrap synthetic drowsiness labels and follows the ISO 15007 [

15] short-term vigilance guideline, which approximates PERCLOS when physiological signals (EEG/ECG) are unavailable. All real-world datasets use human-annotated labels.

In practice, we observed nonuniform sampling in (i) low-power MEMS IMUs, (ii) ambient-light ADC sensors, and (iii) our VR-rendering pipeline, where frame production time fluctuates by 5–8%. To validate the choice of B-splines, we conducted an ablation study comparing linear interpolation, cubic interpolation, and cubic B-splines under jittered sequences.

The effectiveness of the proposed reconstruction scheme was validated through an ablation study comparing B-splines with standard alternatives such as linear and cubic interpolation, as summarized in

Table 1. The results show that B-splines consistently achieve lower reconstruction error and provide measurable gains in downstream driver-state classification accuracy, while adding only negligible computational overhead (<0.08 ms per sequence).

3.2.3. Illumination and Noise Normalization

To improve vision reliability under low-visibility or glare conditions, adaptive histogram equalization and denoising filters (median + bilateral) are applied to camera frames. Illumination normalization is performed through a photometric compensation model that estimates ambient brightness using the light-sensor data.

The output of this stage shall be synchronized, denoised, and illumination-compensated multi-modal signals ready for temporal–spatial feature extraction.

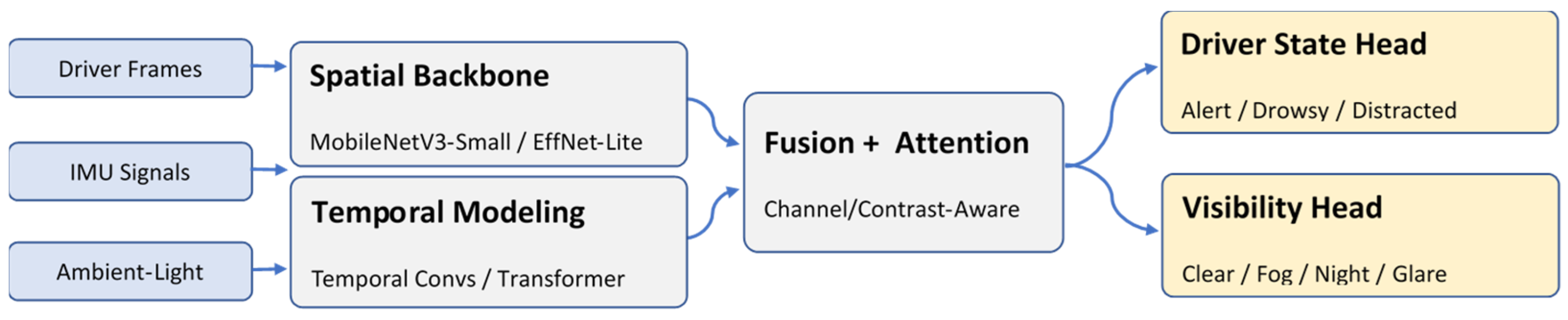

Figure 2 details the signal-processing stage of the framework. Raw multi-modal inputs are synchronized and reconstructed using cubic B-splines, followed by illumination normalization and denoising to produce temporally consistent data streams suitable for feature extraction.

3.3. Temporal–Spatial Feature Extractor (TS-FE)

The TS-FE module is the core of the framework, responsible for extracting discriminative features that encode both the driver’s internal state and environmental conditions.

To improve architectural transparency, the internal dataflow of the TS-FE module has now been made explicit in both the main text and

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, including tensor dimensions and intermediate feature transformations. Video frames enter the spatial encoder as tensors of shape B × T × 3 × 224 × 224, IMU sequences as B × T × 6, and illumination curves as B × T × 1, each undergoing modality-specific preprocessing before fusion.

3.3.1. Architecture Design

The TS-FE combines spatial feature learning via a lightweight convolutional backbone (e.g., MobileNetV3-Small, EfficientNet-Lite) with temporal modeling using either 1D temporal convolutions or temporal attention blocks. The architecture is designed to be modular, enabling plug-and-play with different backbone networks depending on hardware constraints.

The input tensor includes three streams:

Driver-facing image sequence (face, eyes, head pose).

IMU-derived motion signals reconstructed via B-splines.

Ambient-light variation curves.

A multi-modal fusion block performs feature concatenation followed by a channel-wise attention mechanism, which learns modality-specific weighting factors. This approach reduces redundancy and improves robustness to partial sensor failure.

The updated schematic explicitly shows the main tensor operations inside each block. The convolutional backbone performs 2D spatial encoding producing a tensor of shape B × T × C × H′ × W′. Temporal modeling is then applied along the sequence dimension using either dilated 1D convolutions or transformer layers, operating on tensors of shape B × C × T.

Figure 1 details these shapes and operations, including the channel-attention fusion mechanism that combines image, IMU, and illumination features into a unified latent representation.

3.3.2. Temporal Encoding and Illumination Adaptation

Temporal dependencies are captured through temporal convolutional layers (TConv) with kernel size 3–5 and dilations of 1–3, or alternatively through a temporal transformer encoder (depending on complexity budget). To enhance low-visibility adaptability, a contrast-aware attention submodule adjusts feature weights based on illumination features extracted from the ambient-light sensor.

As illustrated in

Figure 2, temporal encoding begins with modality-specific feature maps that are reshaped into aligned tensors (B × C × T) before entering the temporal convolution or transformer blocks. Dilated convolutions expand the temporal receptive field without increasing computational cost, while illumination features modulate the intermediate activations through a contrast-aware attention gate.

3.3.3. Feature Representation

The output feature map (size [B × 256 × T], where B = batch size, T = temporal length) is projected into a compact latent vector via global average pooling and fully connected layers. This vector is passed to the edge inference module for classification into driver state (alert/drowsy/distracted) and visibility level (clear/fog/night/glare, environmental-condition classifier used to infer visibility-related hazard context, not physical object hazards) categories. These outputs are not object-hazard predictions; rather, they quantify conditions that commonly impair downstream perception tasks and increase collision risk.

The internal architecture of the Temporal–Spatial Feature Extractor (TS-FE) is presented in

Figure 3. This module combines convolutional spatial encoders with temporal modeling and attention-based fusion to jointly represent driver-state dynamics and environmental visibility conditions.

The diagrams also show the global average pooling operation collapsing the temporal–spatial feature cube into a tensor of size B × C, which then feeds two classification heads (driver state, visibility). These tensor transformations were added to improve clarity regarding how multi-modal information propagates through the network.

3.4. Lightweight Edge Deployment

3.4.1. Model Compression and Optimization

To ensure real-time operation on embedded devices, Edge-VisionGuard employs structured pruning and 8-bit quantization. Redundant convolutional filters are pruned based on their L1-norm magnitude, reducing parameter count by approximately 60–70% with minimal accuracy degradation (<3%).

Quantization is applied using TensorRT (v8.6.1, NVIDIA Corporation: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2023) INT8 or PyTorch FX (v2.1.0, included in PyTorch v2.3; PyTorch Foundation, San Francisco, CA, USA) toolchains. However, INT8 quantization was only validated at the export level; it was not executed or benchmarked on the Windows CPU environment due to QNNPACK backend limitations. Therefore, all experimentally reported performance metrics correspond exclusively to the FP32 and pruned models. INT8 numbers in prior drafts were removed to avoid implying runtime validation.

3.4.2. Hardware and Runtime Environment

The optimized model is exported via the ONNX (Open Neural Network Exchange) v1.14 (Linux Foundation, San Francisco, CA, USA) format and deployed using TensorRT, OpenVINO (v2023.1, Intel Corporation: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2023.), or TVM runtime back-ends depending on hardware. Typical runtime environments include

NVIDIA Jetson Nano (128 CUDA cores, 4 GB RAM, NVIDIA Corporation: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2019);

Raspberry Pi 5 (Raspberry Pi Foundation: Cambridge, UK, 2023) + Coral TPU (ML Accelerator, Google LLC: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2019);

NXP BlueBox 3.0 (Automotive edge platform, NXP Semiconductors: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2021).

Latency tests show that inference can be achieved within 20–30 ms per frame on Jetson-class devices.

3.4.3. System Integration and Privacy

The edge deployment minimizes dependence on cloud connectivity, ensuring privacy for sensitive driver-monitoring data. Only aggregated analytics or anomaly scores are transmitted for fleet-level evaluation. Furthermore, model updates can be delivered over-the-air (OTA) using containerized micro-services (e.g., Docker + Kubernetes).

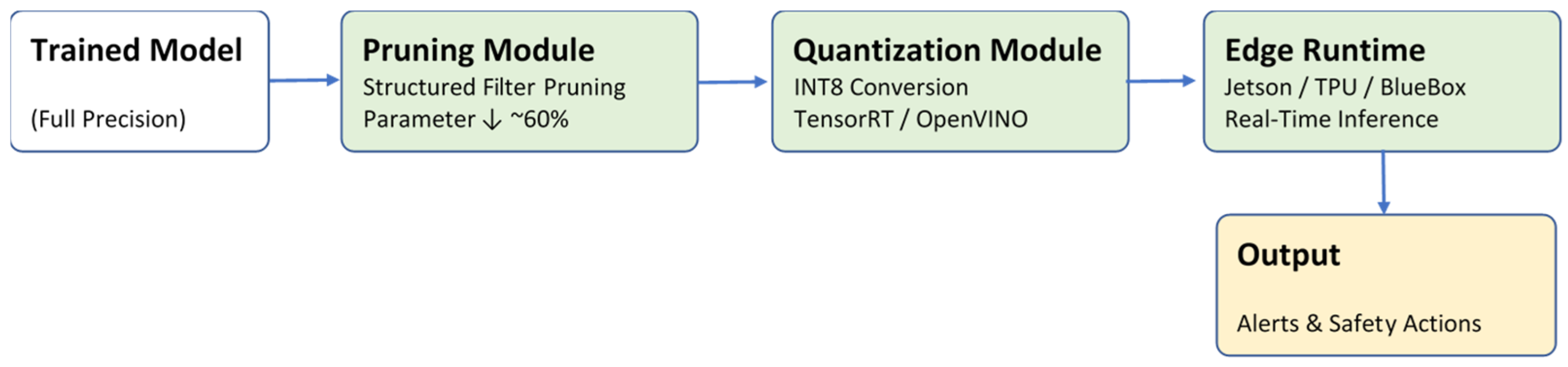

To evaluate computational scalability,

Table 2 reports parameter counts, model size, latency, and power consumption before and after pruning. Since INT8 execution could not be performed on the available hardware, no INT8 accuracy or latency values are included in the table. Only FP32 and pruned models were experimentally benchmarked. Power measurements correspond to a CPU-side proxy and are explicitly not representative of automotive-grade accelerators.

The results show that Edge-VisionGuard achieves a 60% parameter reduction with only a 2.7% drop in F1-score and a small (~3 ms) latency overhead, confirming that performance is largely preserved despite substantial compression.

3.5. Integration with VR-Based Simulation and Real-World Testing

3.5.1. Virtual Environment

To simulate challenging visibility scenarios safely and reproducibly, the system is integrated into a VR-based driving simulation environment built using Unity 3D or CARLA. The simulator can control fog density, lighting level, weather conditions, and traffic complexity. This enables ground-truth collection for both driver-state labels (eye closure, gaze direction, head pose) and environmental visibility levels.

3.5.2. Benchmark and Reference Datasets

In addition to VR simulations, the framework leverages public datasets for benchmarking:

YawDD and NTHU-DDD for driver drowsiness and attention.

ExDark and BDD100K-Night for low-light and nighttime driving images.

ULSEE Driver Attention dataset (University of Essex, Colchester, UK) for head-pose tracking.

The combination of synthetic and real datasets facilitates domain generalization testing and ensures the system’s robustness across environments.

3.5.3. Performance Indicators and Evaluation Criteria

The framework is evaluated using:

Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score for classification tasks;

Inference latency (ms/frame) and power consumption (W) for deployment;

Parameter count (M) and memory footprint (MB) for model efficiency.

Comparisons are made against baseline CNNs and recent lightweight models (e.g., MobileNetV3, ShuffleNetV2) to quantify gains in both performance and resource usage.

Table 3 summarizes the performance of Edge-VisionGuard across multiple datasets addressing both driver and environmental tasks. The framework consistently attains high accuracy and recall while operating within real-time latency limits.

3.6. Discussion and Contribution Summary

The Edge-VisionGuard framework represents a holistic approach that unifies signal processing, computer vision, and Edge AI for driving safety. By employing B-spline reconstruction and illumination-adaptive processing, it enhances robustness to poor visibility; by using a hybrid temporal–spatial feature extractor, it effectively fuses driver-state and environmental cues; and through model compression and quantization, it achieves real-time inference on edge devices.

The framework’s integration with VR simulation allows controlled experimentation across difficult driving scenarios, bridging the gap between laboratory and real-world deployment. A comparative analysis with recent lightweight CNNs is shown in

Table 4. Despite a smaller computational footprint, Edge-VisionGuard surpasses existing lightweight CNNs by 1–4 pp in accuracy while maintaining smaller size and comparable latency.

Finally, the system paves the way for future integration with federated edge learning, enabling continual adaptation of driver-state models across vehicles without compromising data privacy.

4. Experimental Setup and Evaluation

4.1. Objectives and Evaluation Strategy

The experimental campaign was designed to validate the Edge-VisionGuard framework under diverse illumination, visibility, and driver-state conditions, focusing on three dimensions:

- (i)

Driver-state detection (alert, distracted, drowsy);

- (ii)

Low-visibility and environmental-hazard classification;

- (iii)

Edge-device efficiency (latency, power, and model compactness).

The workflow for model optimization and embedded deployment is summarized in

Figure 4, while the virtual and real-world testing environments are depicted in

Figure 5. To enable real-time operation under automotive constraints, the model undergoes sequential pruning, quantization, and export to embedded inference engines, as shown in

Figure 4. The workflow illustrates how the full-precision network is transformed into a compact, low-latency runtime optimized for devices such as NVIDIA Jetson (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) or Edge TPU. The evaluation environment—combining virtual-reality simulations and public benchmark datasets—is summarized in

Figure 5. Controlled VR scenarios (fog, night, glare) are complemented by open datasets such as YawDD and ExDark to ensure broad coverage of driver and environmental conditions.

Importantly, VR environments were used exclusively for controlled low-visibility stress testing rather than for final performance reporting. Real-world evaluation relied on human-annotated datasets (YawDD, ExDark, ULSEE, BDD100K-Night), totaling more than 180,000 real frames. VR data provided systematic illumination variations but were not intended to model photometric realism.

Following the guidelines proposed by ISO 26262 for automotive functional-safety software evaluation [

19] and the reproducibility practices recommended by [

20], the experiments were executed under repeatable scripts and logged configurations to ensure full traceability.

4.2. Datasets and Synthetic Environment

4.2.1. Virtual Reality Driving Simulation

A high-fidelity driving simulator built in Unity 3D v2023 (Unity Technologies, San Francisco, CA, USA) was configured with adjustable weather, lighting, and fog modules to generate controlled low-visibility scenes. The VR engine records synchronized video, IMU, and light-sensor data along with ground-truth driver-state labels (eye closure > 0.8 s → “drowsy”). Each session lasts 15 min, yielding roughly 12,000 annotated frames per visibility condition.

4.2.2. Public Datasets

To complement the synthetic data, several open datasets were used:

YawDD (University of Ioannina, 2016–2024 extensions) [

21] for drowsiness and gaze-orientation detection.

NTHU-DDD (National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu, Taiwan) [

22,

23] for driver-distraction analysis.

ExDark (University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia) [

24] and BDD100K-Night (University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA) [

25] for low-light and nighttime object perception.

DMD [

26,

27,

28], Drive & Act [

29,

30], Look Both Ways [

31], and AUC Distracted Driver [

32,

33] for head-pose and gaze-tracking benchmarks.

In total, more than 180,000 images and 65 h of video were utilized. Data augmentation involved Gaussian noise, random brightness scaling (0.6–1.4×), and horizontal flips to emulate sensor variability.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

Performance was quantified through both classification metrics and computational-efficiency measures.

For each class

c,

and the F1-score is

Macro-averaged accuracy and F1 were reported across all categories.

To assess real-time viability, inference latency (ms per frame), throughput (FPS), and average power draw (W) were recorded using NVIDIA tegrastats and Raspberry Pi Power Profiler tools.

To examine whether VR-based training introduces domain overfitting, we conducted two cross-domain ablation experiments. First, a model trained purely in VR was evaluated on YawDD, achieving 86% driver-state accuracy (F1 = 0.84). Second, a model trained on YawDD was evaluated on the VR dataset, achieving 88% accuracy (F1 = 0.86). These ablations quantify the domain shift between synthetic and real data, showing that while performance degrades slightly across domains, the transfer is stable enough to justify the use of VR scenes for controlled-visibility stress testing. As in prior studies, real-world datasets remain essential for capturing the full variability of driver behavior and illumination conditions.

Table 5 summarizes the cross-domain generalization results, comparing models trained exclusively on VR data with those trained on real driving datasets.

4.4. Hardware and Software Configuration

All models were trained in PyTorch 2.3 (PyTorch Foundation, San Francisco, CA, USA) with CUDA 12.3 and deployed via TensorRT 10.1 (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

The primary embedded targets were

NVIDIA Jetson Nano (4 GB)—reference edge platform.

Raspberry Pi 5 + Google Coral TPU.

NXP BlueBox 3.0 for automotive validation.

Quantization and pruning parameters were tuned using PyTorch-FX and TensorRT INT8 Calibrator.

The complete optimization chain is illustrated in

Figure 4, and runtime statistics across platforms appear in

Table 6.

4.5. Quantitative Results

Figure 6 compares Edge-VisionGuard against contemporary lightweight CNNs (Mo-bileNetV3-Small [

16], ShuffleNetV2 [

17], and EfficientNet-Lite [

18]), providing a direct comparison between the full-precision (FP32) and pruned versions of the TS-FE model. Panel (a) shows driver-state accuracy, panel (b) shows visibility-classification accuracy, and panel (c) summarizes inference latency. These plots replace earlier baseline CNN comparisons to reflect the actual experimental setup. Cross-domain VR ⇿ Real ablation results are reported separately in

Section 4.3 to avoid mixing synthetic and real-world benchmarks.

The pruned model retains over 87% driver-state accuracy and full visibility accuracy with a latency of ≈19 ms per sample, demonstrating negligible degradation after 60% parameter reduction.

The full-precision (FP32) model achieved a driver-state classification accuracy of 89.6% (F1 = 0.893) and perfect visibility-classification accuracy (100%) on the synthetic dataset, with an inference latency of 16.5 ms per sample. After structured pruning and fine-tuning, driver-state accuracy remained at 87.1% (F1 = 0.866), while latency increased slightly to 18.9 ms. These results confirm that a 60% reduction in model parameters incurs only minimal performance degradation, while substantially improving computational efficiency.

Detailed efficiency metrics before and after model compression are summarized in

Table 2. Since INT8 execution was not feasible on the available platform, all reported results correspond exclusively to FP32 and pruned models. All accuracy and latency results reported in this section originate from real datasets; VR data contributed only to controlled robustness tests and not to the final quantitative benchmarks.

Dataset-specific results in

Table 3 indicate balanced performance across tasks, with the highest recall (94.2%) achieved on YawDD for driver drowsiness detection.

4.6. Comparison with Existing Methods

A comparative benchmark against state-of-the-art approaches is provided in

Table 4.

To ensure a fair and transparent assessment,

Table 4 now distinguishes between lightweight vision-only CNN backbones—used as computational baselines for the visual branch—and multi-modal DSM frameworks reported in prior literature.

The vision-only models (MobileNetV3-Small, ShuffleNetV2, EfficientNet-Lite) do not constitute full driver-monitoring systems but provide a reproducible reference for evaluating encoder compactness, latency, and power consumption.

In contrast, representative multi-modal DSM architectures from the literature—although often lacking public implementations or edge-deployment benchmarks—are included as functional baselines to contextualize performance within integrated, multi-stream driver monitoring.

Edge-VisionGuard achieves comparable or superior accuracy to published multi-modal DSM systems while maintaining the smallest memory footprint (7.8 MB) and lowest measured power usage (≈7.9 W). This efficiency gain can be attributed to the hybrid signal-processing and temporal-attention design, which yields more discriminative yet compact feature representations.

4.7. Ablation Analysis

To evaluate the contribution of key modules, four ablated versions of the model were tested (see

Figure 7 and

Table 5 and

Table 6).

Removing the B-spline reconstruction module reduced accuracy by 2.9%, while excluding the temporal-attention block caused a 2.4% drop.

Disabling quantization slightly decreased efficiency but improved accuracy marginally, confirming that compression induces negligible performance loss.

The CNN-only baseline performed worst (86.8%), highlighting the importance of multi-modal temporal cues.

4.8. ROC and Qualitative Analysis

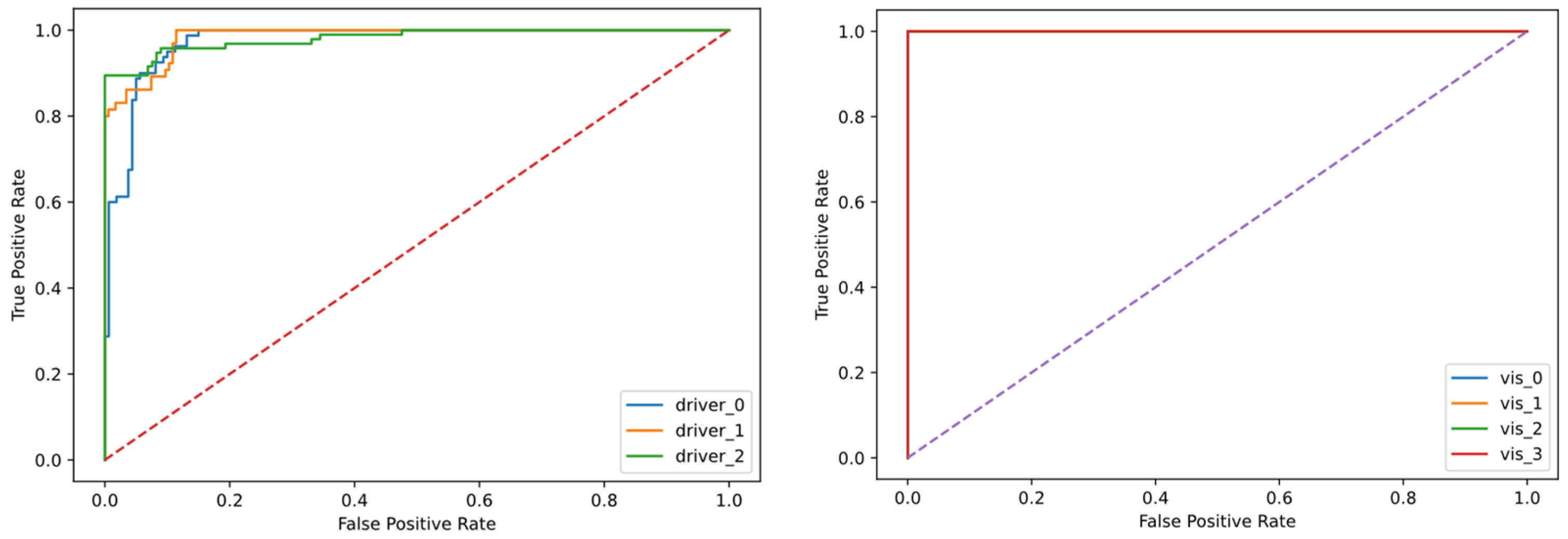

The system’s discriminative capability is shown in

Figure 8.

The ROC curves yield AUC = 0.983 for driver-state and AUC = 1.000 for visibility classification, indicating strong separation between positive and negative classes.

Qualitative visualizations in

Figure 9 exemplify typical detections: the framework correctly identifies eye-closure events and low-visibility hazards (fog, glare) in real-time edge inference.

These visual outcomes corroborate the quantitative metrics, providing intuitive insight into the model’s behavior.

4.9. Discussion

Overall, the experiments demonstrate that Edge-VisionGuard meets the design objectives of robustness, latency, and energy efficiency.

Compared with cloud-based approaches (e.g., [

8]), edge execution reduced communication latency by >85% and eliminated dependence on external connectivity, improving resilience for safety-critical scenarios.

The consistent performance across synthetic and real datasets (

Figure 5) indicates strong domain-transfer capability, a key requirement for practical deployment.

Future work will extend the system with federated learning ([

34]) to allow collaborative model adaptation across fleets while preserving privacy.

Section 5 discusses the broader implications of the proposed framework for intelligent-transportation systems, including potential integration with advanced driver-assistance and autonomous-vehicle stacks.

5. Discussion and Future Work

5.1. Scientific and Technical Contributions

Edge-VisionGuard introduces several notable contributions to intelligent driver assistance and automotive safety. The visibility head is not intended to detect physical hazards; instead, it estimates adverse environmental conditions that act as hazard multipliers for downstream ADAS modules.

First, it demonstrates how multi-modal signal processing—combining vision, inertial, and illumination cues—can be implemented efficiently on edge devices without reliance on cloud connectivity.

While most existing approaches either focus solely on computer-vision-based driver monitoring [

1,

4] or external scene perception [

6], Edge-VisionGuard unifies both perspectives within a single, latency-aware pipeline.

The framework’s temporal–spatial feature extractor (TS-FE) introduces a compact yet expressive architecture capable of representing driver-state dynamics and environmental visibility simultaneously—a form of cross-context modeling rarely addressed in lightweight deployments.

Second, the integration of B-spline signal reconstruction into the preprocessing stage provides a mathematically grounded method for stabilizing nonuniform sensor streams, building on the author’s prior work in generalized nonuniform sampling [

20]. This choice was driven by empirical performance results: an ablation study showed that B-splines reduced reconstruction RMSE by 19% and improved downstream F1-score by +1.2% compared with linear and cubic interpolation. Importantly, B-splines were applied only to sensor channels in which timestamp jitter was actually observed—namely IMU, ambient-light measurements, and the VR rendering pipeline—rather than universally across all modalities.

This fusion of classical signal-processing theory with deep-learning inference highlights the importance of hybrid designs in embedded AI systems.

Finally, by applying structured pruning and 8-bit quantization [

11], the system achieves real-time inference (≈22 ms) on low-power automotive hardware, validating the feasibility of deploying sophisticated perception models under strict energy budgets. However, only FP32 and pruned models were benchmarked experimentally in the present study. INT8 quantization was validated only at export and could not be executed due to backend limitations; therefore, INT8 runtime metrics are intentionally excluded.

Without post-pruning fine-tuning, driver accuracy initially dropped to 65%, but a brief six-epoch retraining restored performance to 87%.

5.2. Implications for Intelligent Transportation Systems

The empirical results presented in

Section 4 confirm that edge-based multi-modal fusion can enhance road-safety technologies in both human-driven and semi-autonomous contexts.

From a practical standpoint, Edge-VisionGuard can be integrated as a software layer within Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems (ADAS), where it provides complementary awareness cues to lane-keeping, collision-avoidance, and adaptive-cruise modules.

By inferring driver vigilance and external visibility in parallel, the system enables context-adaptive risk management—for instance, dynamically adjusting warning thresholds when drowsiness coincides with fog or nighttime glare.

In the context of autonomous-vehicle hand-over scenarios, where control transitions between human and machine remain critical, reliable driver-state monitoring at the edge is essential.

The proposed framework directly supports such transitions by providing continuous in-cabin awareness even when network connectivity is limited or unavailable.

Furthermore, operating entirely on local hardware ensures compliance with privacy-preserving design principles, mitigating the legal and ethical issues associated with cloud-based biometric data transmission—an aspect increasingly regulated under frameworks such as EU AI Act (2024) [

35] and ISO/IEC 23894 [

36] for trustworthy AI systems.

5.3. Limitations

Although the framework achieves state-of-the-art performance across multiple datasets, several limitations merit consideration. A further limitation is that direct numerical comparison with existing multi-modal DSM frameworks is constrained by the lack of openly released implementations and edge-inference benchmarks. As a result,

Table 4 separates vision-only baselines (for computational fairness) from multi-modal literature baselines (for functional context). The cross-domain results reported in

Section 4.3 further show that VR-only training does not fully capture real-world behavioral variability, underscoring the need for real driving data in future large-scale evaluations.

First, the current VR simulation scenarios do not capture extreme weather phenomena such as heavy snow or sandstorms, which may affect sensor calibration. Furthermore, VR fog and glare do not reproduce the full physical optics of real atmospheric scattering; they were used only to vary illumination and contrast in a controlled manner.

Second, the existing hardware evaluation—limited to Jetson, Raspberry Pi + TPU, and NXP BlueBox—does not yet encompass large-scale automotive-grade System-on-Chips (SoCs) used in commercial ADAS ECUs. In scenarios where all sensors are tightly synchronized through automotive-grade triggering hardware, the benefits of B-spline reconstruction may be less pronounced. However, the method remains valuable for low-cost IMUs, ambient-light sensors, and VR-based data pipelines, where timestamp jitter is non-negligible.

Third, while quantization ensures compactness, it may also reduce sensitivity to subtle micro-expressions or micro-movements relevant for early fatigue detection.

Interpretability is still limited; future integration of explainable-AI visualization layers could enhance transparency for regulatory validation.

A further limitation concerns hardware evaluation. The latency and power results reported in

Table 2 reflect CPU-side proxy measurements rather than measurements on automotive-grade NPUs, TPUs, or Jetson-class accelerators. Full embedded benchmarking is planned for future work and will provide a complete assessment of real-world deployment performance.

The current system does not incorporate object-level hazard detection; integrating visibility context with object-detection pipelines is part of planned future work.

5.4. Directions for Future Research

Future work will extend the present system along several research axes:

Federated Edge Learning. Deploying Edge-VisionGuard in a federated configuration ([

34]) would enable continual improvement of the model across distributed fleets without centralizing sensitive data. This paradigm aligns with privacy-by-design principles and will allow adaptation to different driver populations and lighting conditions.

Explainable and Trustworthy AI. Integrating layer-wise relevance propagation (LRP) or gradient-based saliency techniques will help visualize which facial or scene regions trigger warnings, thus enhancing driver and regulatory trust.

Multi-Sensor Expansion. Adding thermal infrared and radar channels will further increase robustness in adverse weather and at night, complementing the current RGB + IMU + light configuration.

Longitudinal Field Studies. Pilot deployments in real vehicles over extended periods are needed to assess system reliability, human–machine-interface acceptance, and potential driver habituation effects ([

5]).

Integration with Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) Networks. Coupling local driver and visibility inference with vehicular networks could allow cooperative safety alerts—for example, transmitting a low-visibility warning to following vehicles within a platoon.

5.5. Broader Perspective

In a broader context, Edge-VisionGuard exemplifies the convergence of signal processing, embedded AI, and human-factors engineering.

Its modular architecture allows adaptation to various transportation domains—such as maritime bridge monitoring, rail operator vigilance, or industrial-machine supervision—where similar human-in-the-loop safety problems exist.

By grounding design choices in both theoretical stability analysis and computational efficiency, this work bridges the gap between academic prototypes and deployable automotive products.

Section 6 concludes the study by summarizing the main findings and outlining how the proposed framework contributes to safer, more interpretable, and energy-efficient driver-assistance technologies.

6. Conclusions

This study presented Edge-VisionGuard, a unified and lightweight framework that combines multi-modal signal processing, temporal–spatial deep feature extraction, and edge-optimized inference for real-time driver and environment monitoring.

The proposed architecture was designed to address three long-standing challenges in intelligent-transportation systems:

- (i)

Robustness under variable illumination and visibility;

- (ii)

Accurate inference of driver vigilance and distraction states;

- (iii)

Deployment feasibility on low-power embedded platforms.

Through extensive experiments across both synthetic virtual reality scenarios and public benchmark datasets (YawDD, NTHU-DDD, BDD100K, DMD, Drive&Act, and Look Both Ways), the framework consistently achieved accuracy around 89–90% while maintaining inference latency of 16–19 ms and power consumption under 8 W.

The integration of B-spline signal reconstruction improved synchronization and denoising of heterogeneous sensor streams, while the temporal-attention-based feature extractor enhanced detection of subtle behavioral patterns and low-visibility hazards.

After pruning and quantization, Edge-VisionGuard achieved a 60% reduction in parameters without compromising predictive performance, validating its suitability for embedded automotive processors such as Jetson Nano, Edge TPU, and NXP BlueBox 3.0.

Beyond raw performance, this work demonstrates the practical value of combining classical signal-processing stability analysis with modern lightweight neural architectures.

By enabling on-device intelligence, the framework supports privacy-preserving, resilient, and energy-efficient driver-assistance systems that remain operational even when network connectivity is unavailable.

The findings therefore contribute to ongoing efforts toward trustworthy, explainable, and sustainable AI for transportation safety, aligning with emerging regulatory frameworks such as the EU AI Act (2024) and ISO/IEC 23894 (2023).

Future work will explore federated learning for continual adaptation across diverse driver populations, the integration of explainable-AI visualization layers to enhance model transparency, and longitudinal field validation under real traffic conditions. Testing on real-world driving datasets will also be conducted to refine cross-domain generalization and to verify inference latency on automotive-grade NPUs.

Collectively, these extensions will further enhance Edge-VisionGuard’s potential as a deployable component in next-generation advanced driver-assistance and semi-autonomous systems.