1. Introduction

With the increasing exploration and development of conventional medium- to high-permeability reservoirs, unconventional tight reservoirs have become a strategic frontier for global oil and gas exploration [

1,

2,

3]. In China, significant breakthroughs have been achieved in the exploration of tight oil and gas resources in recent years. However, compared with the rapid progress in exploration practices, the corresponding fundamental theoretical research remains relatively underdeveloped. The international academic community has established a relatively systematic research framework for clastic tight reservoirs, primarily focusing on three key aspects: characterization of reservoir properties, mechanisms of reservoir densification, and genesis of high-quality reservoirs [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Clastic tight reservoirs are typically characterized by low compositional maturity, extremely small pore and throat radii, complex pore structures, low permeability, and intense yet heterogeneous diagenetic alterations [

8,

9,

10]. Their compaction and densification processes are strongly influenced by deep burial, complex diagenetic alterations, and multiphase tectonic activities [

7,

11,

12]. Notably, under the prevailing background of overall tightness, the development of relatively high-quality reservoirs often exhibits a “multi-factor synergistic control” pattern. Current studies indicate that the spatiotemporal coupling of favorable sedimentary facies belts [

13,

14], the presence of anomalous secondary dissolution zones [

15], overpressure conditions [

16], early hydrocarbon charging [

17], and clay mineral coatings [

18] are key factors in the formation of relatively high-permeability intervals.

However, two major research gaps hinder a predictive understanding of “sweet spot” formation. First, most studies focus on the static characterization of present-day reservoir properties, lacking dynamic analyses of property evolution and its coupling with hydrocarbon accumulation processes. Second, in closed diagenetic systems at medium to deep burial depths (depth > 2000 m), the role of dissolution in enhancing reservoir quality is limited [

19,

20], while original sedimentary facies, compaction, and cementation exert more dominant controls. Consequently, the controlling factors responsible for the development of relatively high-quality intervals within tight reservoirs remain a subject of considerable debate. This knowledge gap directly constrains the ability to predict the spatial distribution of high-quality reservoirs.

A series of recent exploration breakthroughs in the tight sandstone gas reservoirs of the Middle Jurassic Shaximiao Formation in the Sichuan Basin has provided an excellent geological case for investigating the aforementioned scientific questions [

21,

22]. This stratigraphic unit developed within a shallow-water delta–fluvial interactive depositional system, where laterally stacked and regionally extensive sandstone bodies laid the material foundation for large-scale tight gas accumulation [

23,

24]. Research has revealed that the reservoirs underwent multiphase diagenetic modifications during burial evolution and exhibit the following typical characteristics: (1) widespread zeolite cementation and chlorite coatings [

25]; (2) localized dissolution-induced secondary porosity [

26]; and (3) a “sweet spot” pattern of relatively high porosity and permeability reservoirs developed within an otherwise tight background. Consequently, the core scientific problems that need to be addressed are: (1) What is the precise timing relationship between reservoir densification and hydrocarbon charging? and (2) What is the genetic mechanism behind the formation of high-quality reservoirs? These issues remain major constraints on further efficient exploration.

To address these challenges, this study focuses on the following three aspects: (1) Characterization of the reservoir properties and diagenetic features of tight sandstones in the Shaximiao Formation in the central Sichuan Basin based on detailed petrographic analysis; (2) Reconstruction of porosity evolution and analysis of hydrocarbon charging history using fluid inclusion homogenization temperature data to elucidate the coupling relationship between reservoir densification and hydrocarbon emplacement; (3) A comprehensive analysis of the genesis of high-quality reservoirs from the integrated perspectives of sedimentation, diagenesis, and hydrocarbon migration and accumulation. The goal is to provide critical geological insights for the exploration and development of continental tight sandstone gas reservoirs in the Sichuan Basin, with broader implications for tight gas exploration in similar sedimentary basins worldwide.

2. Geological Setting

The Sichuan Basin is located in the northwestern margin of the Upper Yangtze Craton in western China (

Figure 1A). It is a large-scale superimposed basin developed upon a rigid granitic basement [

27,

28]. Since the Late Triassic, the basin has experienced a transition from a foreland basin to an intracratonic depression, driven by the superimposed, multi-phase and multi-directional tectonic stress fields associated with the Indosinian to Himalayan orogenic events. This transition led to the evolution of the Jurassic “Red Basin” stage [

28,

29,

30]. The closure of the Qinling Ocean during the Late Indosinian orogeny exerted far-field compressional stresses, causing episodic uplift of the Micang–Daba Mountain structural belt along the northeastern margin of the basin. This belt became the principal sediment source area for Jurassic deposition [

31,

32,

33]. Driven by both peripheral compressional forces and the continuous uplift of the Central Sichuan Paleo-uplift, a well-zoned structural framework developed across the basin (

Figure 1B). Based on differences in deformation intensity and structural style, the basin is subdivided into six major tectonic units: the Western Sichuan Depression, Northern Sichuan Fold-and-Thrust Belt, Central Sichuan Gentle Structural Belt, Southwestern Sichuan Low-Amplitude Fold Zone, Southern Sichuan Structural Belt, and Eastern Sichuan High-Amplitude Fold Belt [

34]. This study focuses on the north-central segment of the Central Sichuan Gentle Structural Belt (

Figure 1C), where the relatively stable tectonic setting was crucial for preserving primary porosity by mitigating intense structural compaction and fracture development, thereby creating a favorable background for reservoir quality.

The target interval of this study is the Middle Jurassic Shaximiao Formation. Stratigraphically, it is overlain by the red mudstone of the Suining Formation and underlain by deltaic sandstones of the Lianggaoshan Formation. A regionally continuous marker bed of conchostracan-bearing shale divides the Shaximiao Formation into two members: the Lower Member (J2S1) and the Upper Member (J2S2) [

35]. Within the Central Sichuan Gentle Structural Belt, the Shaximiao Formation is characterized by a typical suite of continental clastic rocks. The lithologic assemblage consists of interbedded purple-red mudstone, light gray fine sandstone, and grayish-green siltstone of varying thicknesses (

Figure 2). Sedimentological analysis indicates a fluvial to shallow-water deltaic transitional system, within which various subfacies such as distributary channels, subaqueous distributary channels, and mouth bars are well developed in the delta front setting (

Figure 1D) [

23]. These high-energy depositional microfacies are of particular importance, as they favored the deposition of medium- to coarse-grained sandstones with superior initial porosity and permeability, which laid the essential material foundation for the development of high-quality reservoirs. Subsequent diagenetic processes, therefore, acted upon this primary depositional heterogeneity. It is worth noting that dark mudstone is poorly developed in the Shaximiao Formation, and the organic matter abundance is significantly below the threshold for effective hydrocarbon source rocks. As a result, the formation itself lacks the capacity for substantial hydrocarbon generation [

36]. Consequently, the hydrocarbon charging of the Shaximiao Formation reservoirs must have been driven by long-distance lateral migration from underlying source rocks, a process intimately linked to the basin’s structural evolution, making the timing of this charging relative to in situ diagenetic densification a critical control on final reservoir quality.

3. Samples and Methods

This study is based on a comprehensive and spatially diverse dataset to ensure robust and representative characterization of the Shaximiao Formation reservoir. A total of 4828 porosity and permeability test datasets were collected from the Southwest Oil and Gas Field Branch of PetroChina. The dataset originates from 32 wells across the study area, covering a depth interval of 1650 to 2600 m.

A systematic petrographic analysis was performed on 207 blue-epoxy-impregnated thin sections to quantitatively characterize the mineral composition, diagenetic products, and pore systems of the Shaximiao Formation sandstones. Impregnation ensures that pore spaces are clearly distinguishable from solid mineral grains under plane-polarized light. The analyzed sandstone samples cover various depths and major depositional microfacies (e.g., distributary channels, mouth bars) within the reservoir interval of the study area, ensuring the representativeness of the dataset for the entire reservoir.

Quantification of thin-section components was achieved using standard point-counting techniques. This method was selected as it is an internationally established statistical approach, whose principle is that the area percentage of a component approximates its volume percentage. To ensure statistical robustness and representativeness, a total of 400 points were counted for each thin section. The spacing between grid points was set to exceed the average diameter of the dominant detrital grains to prevent bias from repeatedly counting the same grain.

Based on point counting results, the compactional porosity loss (COPL) and cementational porosity loss (CEPL) were quantitatively calculated following the methods proposed by Houseknecht [

38,

39]. The calculation formulas are as follows:

where

OP = original intergranular porosity (typically assumed);

IGV = intergranular volume as a percentage of OP, including intergranular porosity, matrix, and cement;

CEM = cement content as a percentage of the rock;

COPL = porosity loss due to compaction;

CEPL = porosity loss due to cementation.

To further quantify the effects of diagenetic processes such as compaction, cementation, and dissolution on the porosity of Shaximiao Formation sandstones, the apparent compactional reduction (ACOR), apparent cementation rate (ACER), and apparent dissolution rate (ADR) were calculated according to methods from [

40,

41], using the following equations:

Here, Porosity refers to the present-day rock porosity, which can be approximated by image-based porosity (e.g., 2D porosity from thin sections).

The ACER value reflects the overall proportion of cement to intergranular volume but does not differentiate between cement types. Since multiple types of cement (e.g., laumontite, calcite, and authigenic quartz) are common in Shaximiao Formation reservoirs, we further calculated the following indices to assess the impact of each cement type:

where

Laumontite CEM = volume percentage of laumontite cement;

Calcite CEM = volume percentage of calcite cement;

Quartz CEM = volume percentage of quartz cement.

Microscopic analysis of reservoir microstructures was conducted on 10 selected samples using a COXEM EM-30 field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) equipped with a backscattered electron (BSE) detection system. This high-resolution analysis was performed to clarify the diagenetic sequences and spatial relationships between minerals and pores, which are beyond the resolution limit of conventional optical microscopy.

Mineralogical composition was analyzed on 25 representative core samples using an X’Pert Pro MPD powder X-ray diffractometer. These samples were strategically selected from key wells and depth intervals to cover the full range of lithologies and depositional facies identified in the Shaximiao Formation reservoir, thereby minimizing sampling bias and ensuring the results are representative of the entire reservoir section. The analyses were performed with a Cu-Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5406 Å), over a scanning range of 5–70° 2θ, with a step size of 0.02° and a scan rate of 4°/min. Semi-quantitative mineral identification and phase analysis were performed using Jade software in conjunction with the ICDD PDF database to determine the relative abundances of major minerals. This XRD analysis was employed to provide bulk mineralogical data that complement and verify the point-counting results from thin sections, achieving a more comprehensive mineral inventory crucial for understanding diagenetic pathways and reservoir quality. For clay mineral analysis, oriented mounts were prepared using the ethylene glycol saturation method. The relative proportions of smectite, illite, kaolinite, and chlorite were determined based on the diagnostic shifts in basal (001) spacing after glycolation. The quantitative clay mineral types and abundances obtained are critical for discussing the controls of diagenetic clay evolution on reservoir porosity and permeability in the subsequent sections.

The genesis of diagenetic minerals was investigated using a Leica DM4P cathodoluminescence (CL) microscope system. This technique was specifically applied to key samples exhibiting significant carbonate or quartz cementation to distinguish between different mineral generations and infer their formative conditions. Experimental conditions were set at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV and a beam current of 250 μA. A CL-2 cold cathode electron gun was used to excite the samples and obtain characteristic luminescence signatures of minerals such as calcite.

Pore structure characteristics of various sandstone types using an AutoPore IV 9500 fully automated mercury intrusion porosimeter. Samples were machined into standard cylindrical plugs (25 mm diameter, 25 mm length), cleaned ultrasonically in a toluene–methanol mixture (40 kHz, 30 min), and dried in an oven at 105 °C until constant weight (mass variation < 0.1%/h). The intrusion test was conducted under a stepwise pressure increase, with a maximum pressure of 200 MPa. This analysis provides crucial quantitative data on pore-throat size distribution, porosity, and connectivity, which are directly used to interpret the permeability differences among the various sandstones.

4. Results

4.1. Petrography

The tight sandstone reservoirs of the Shaximiao Formation in the central Sichuan Basin are primarily composed of fine-grained sandstone, medium- to coarse-grained sandstone, and siltstone. The sedimentary structures and grain characteristics of these facies provide insights into their initial reservoir potential.

The medium- to coarse-grained sandstone facies are dominated by moderately sorted, subangular to subrounded sand-sized particles. These facies commonly exhibit massive bedding (

Figure 3A), planar lamination (

Figure 3B), and trough cross-bedding. Sand body thickness ranges from several tens of centimeters to several meters. These features are indicative of high-energy depositional environments conducive to developing well-interconnected primary porosity.

The fine-grained sandstone facies are also composed predominantly of medium sand-sized grains, but with moderate to poor sorting and subangular to subrounded textures. These sandstones frequently display wedge-shaped cross-bedding (

Figure 3C) and planar lamination (

Figure 3D), with sand body thickness similarly ranging from tens of centimeters to several meters.

The siltstone facies consist mainly of poorly sorted and poorly rounded silt-sized grains, accompanied by a clay matrix and abundant mica. Wave-generated ripple lamination is the most characteristic sedimentary structure of this facies (

Figure 3E,F). The high matrix content and poor sorting inherent to this facies represent the least favorable starting condition for reservoir development.

The detrital components of the sandstones are primarily composed of quartz, feldspar, and rock fragments, with minor amounts of mica and other accessory grains. Quartz content ranges from 52% to 78%, with an average of 64.56%. Feldspar content varies from 4% to 20%, averaging 12.16%, including 1–14% potassium feldspar (average 4.00%) and 3–14% plagioclase (average 8.16%). Rock fragments constitute 13% to 36% of the framework grains, with an average of 23.27%. Among these, volcanic rock fragments range from 4% to 17% (average 11.66%), metamorphic rock fragments from 5% to 36% (average 8.18%), while sedimentary rock fragments are relatively rare, ranging from 2% to 8% (average 7.11%).

Accordingly, the average framework composition of sandstones in the study area is quartz (64.56%), feldspar (12.16%), and rock fragments (23.27%), classifying most samples as feldspathic litharenites (

Figure 4). The matrix is mainly composed of clay-grade material, generally low in content and unevenly distributed. It occurs mostly as intergranular fillings or grain coatings, with an average content of 2.88%. The sandstones are moderately to well sorted, with subangular to subrounded grain shapes, reflecting a moderate degree of textural maturity. The significant proportion of volcanic rock fragments and feldspar is a key control on subsequent diagenetic pathways, particularly dissolution.

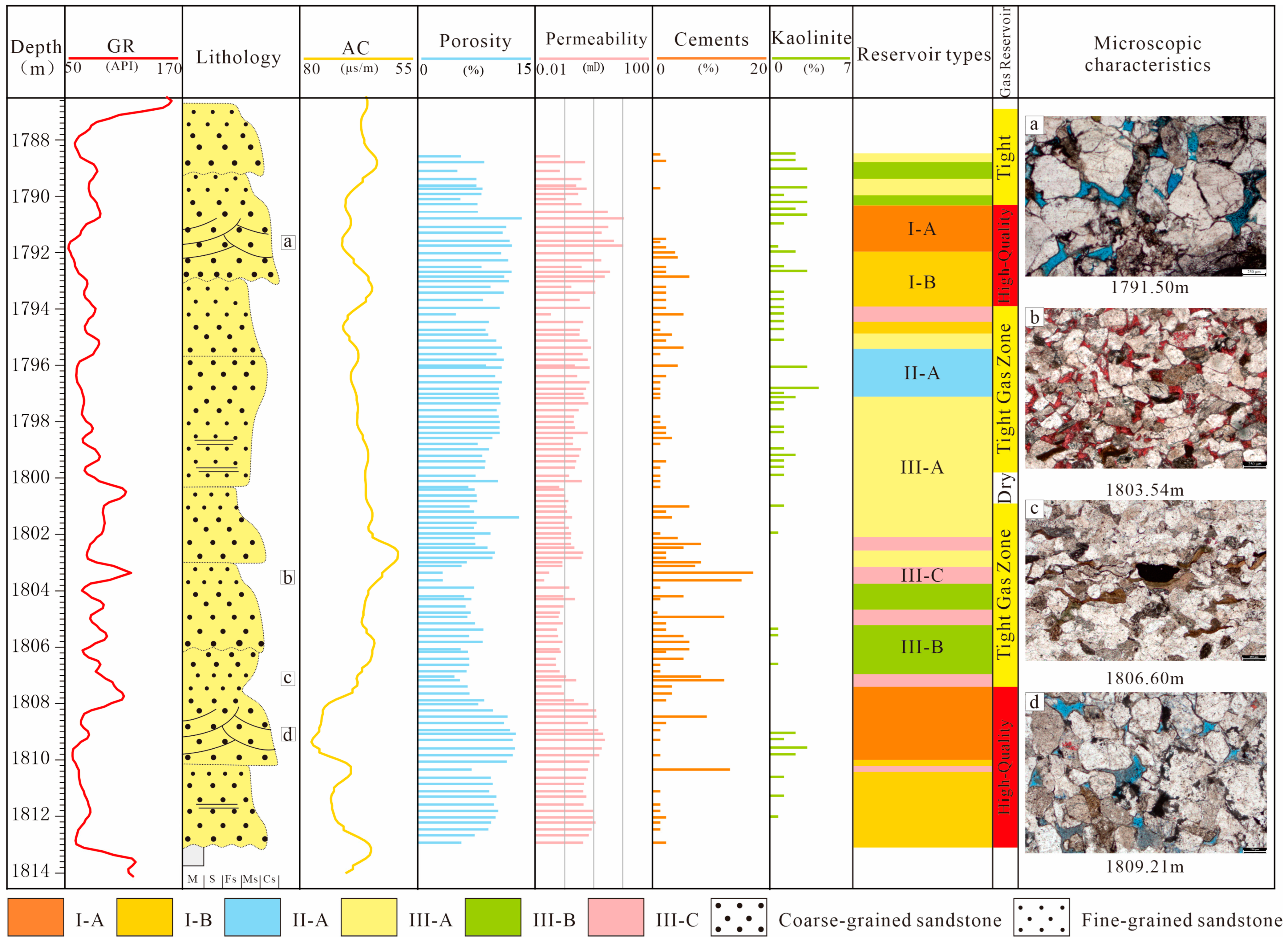

4.2. Porosity and Permeability

Statistics from core-based measurements of porosity and permeability indicate that the Shaximiao Formation reservoirs in the study area are characterized by low porosity and ultra-low permeability. The average porosity is 10.58% (n = 4828), and the average permeability is 2.54 mD (n = 4828), with both parameters displaying strong heterogeneity (

Figure 5). The porosity histogram shows a dominant peak between 5% and 20%, with low-porosity reservoirs (Φ < 15%) accounting for the vast majority (93.83%), and only 6.17% of samples exhibiting medium to high porosity (

Figure 5A). Permeability distribution shows a distinctly skewed pattern. Ultra-low-permeability reservoirs (K < 10 mD) and low-permeability reservoirs (10 ≤ K < 50 mD) make up 77.78% and 17.42% of the samples, respectively, while only 4.81% of the samples fall into the medium-permeability category (

Figure 5B).

Notably, there is a strong correlation between low porosity and ultra-low permeability, with such combinations constituting 75.62% of the total dataset. These composite reservoirs represent the dominant reservoir type in the study area (

Figure 5C).

4.3. Pore-Throat Structure

Based on porosity and permeability tests, high-pressure mercury intrusion (MIP), and petrographic thin section analysis, the pore structures of sandstones with different permeability levels were systematically compared. The results indicate that the combination of pore types and pore-throat structure parameters exerts significant control on reservoir permeability. The results reveal a clear evolutionary trend in pore-throat geometry with increasing permeability, which dictates reservoir deliverability.

For reservoirs with permeability < 0.1 mD, porosity is mainly in the range of 7–13% (

Figure 6A). The pore system consists of a composite network of micrometer-scale matrix pores, intercrystalline pores within clay minerals, and a small number of dissolution pores (

Figure 6B). The pore-throat radius exhibits a bimodal distribution, with a primary peak at 0.005–0.03 μm and a secondary peak at 0.05–0.5 μm. Pore throats in the range of 0.1–0.5 μm contribute more than 90% of the permeability. The maximum mercury saturation ranges from 53% to 66%, with an average of 60.13% (

Figure 6C). This pore system is characterized by fine throats and poor connectivity, severely restricting flow.

For reservoirs with permeability between 0.1 and 1 mD, porosity ranges from 7% to 15%, with an average of 10.99%. The dominant pore types include remnant intergranular pores and feldspar dissolution pores (

Figure 6D,E). The main pore-throat radius range is 0.1–1 μm, with pore throats of 0.5–1 μm contributing over 90% of the permeability. Maximum mercury saturation increases to 60–84%, with an average of 68.2% (

Figure 6F). The shift towards larger, more effective pore throats marks a significant improvement in flow capacity.

For reservoirs with permeability between 1 and 10 mD, porosity generally exceeds 10% (average 12.28%) (

Figure 6G), and primary intergranular pores are well developed (

Figure 6H). The pore-throat radius shows a normal distribution between 0.1 and 4 μm. Although throats > 1 μm account for only 42.75% of the pore volume, they contribute up to 96.66% of the total permeability (

Figure 6I).

For reservoirs with permeability > 10 mD, high porosity is evident, ranging from 13% to 20%, with 84.92% of samples showing porosity > 15% (

Figure 6J). The pore system is a combination of primary intergranular pores and dissolution pores related to volcanic rock fragments and feldspar (

Figure 6K). The effective connectivity between primary and secondary pores is likely the main reason for the relatively high permeability of this reservoir type. Pore throats predominantly range from 1 to 50 μm, with those between 6 and 25 μm contributing 96.3% of the permeability (

Figure 6L). This represents the optimal pore-throat configuration, where both abundant pores and highly connected, large throats coexist.

4.4. Diagenesis

4.4.1. Compaction

The present burial depth of the sandstone reservoirs in the study area generally does not exceed 3000 m [

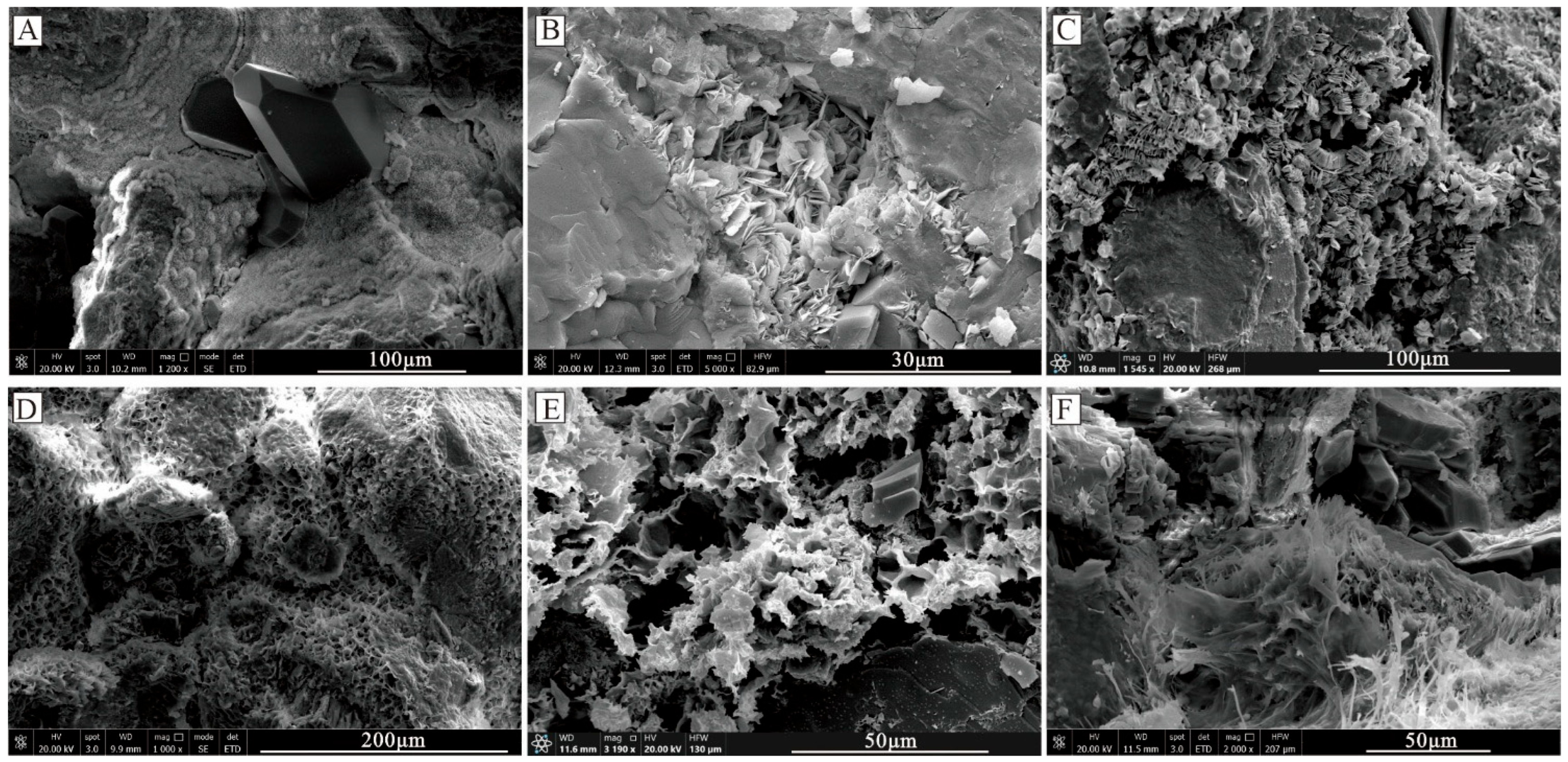

43], indicating that the reservoirs have primarily undergone moderate compaction. Petrographic observations show that rigid grains are predominantly in point and linear contact. In some areas, plastic deformation of volcanic and sedimentary rock fragments can be observed, locally forming pseudo-matrix due to compaction-induced squeezing (

Figure 7A). Despite the moderate burial, compaction is identified as the most significant process in reducing the initial pore volume.

4.4.2. Cementation

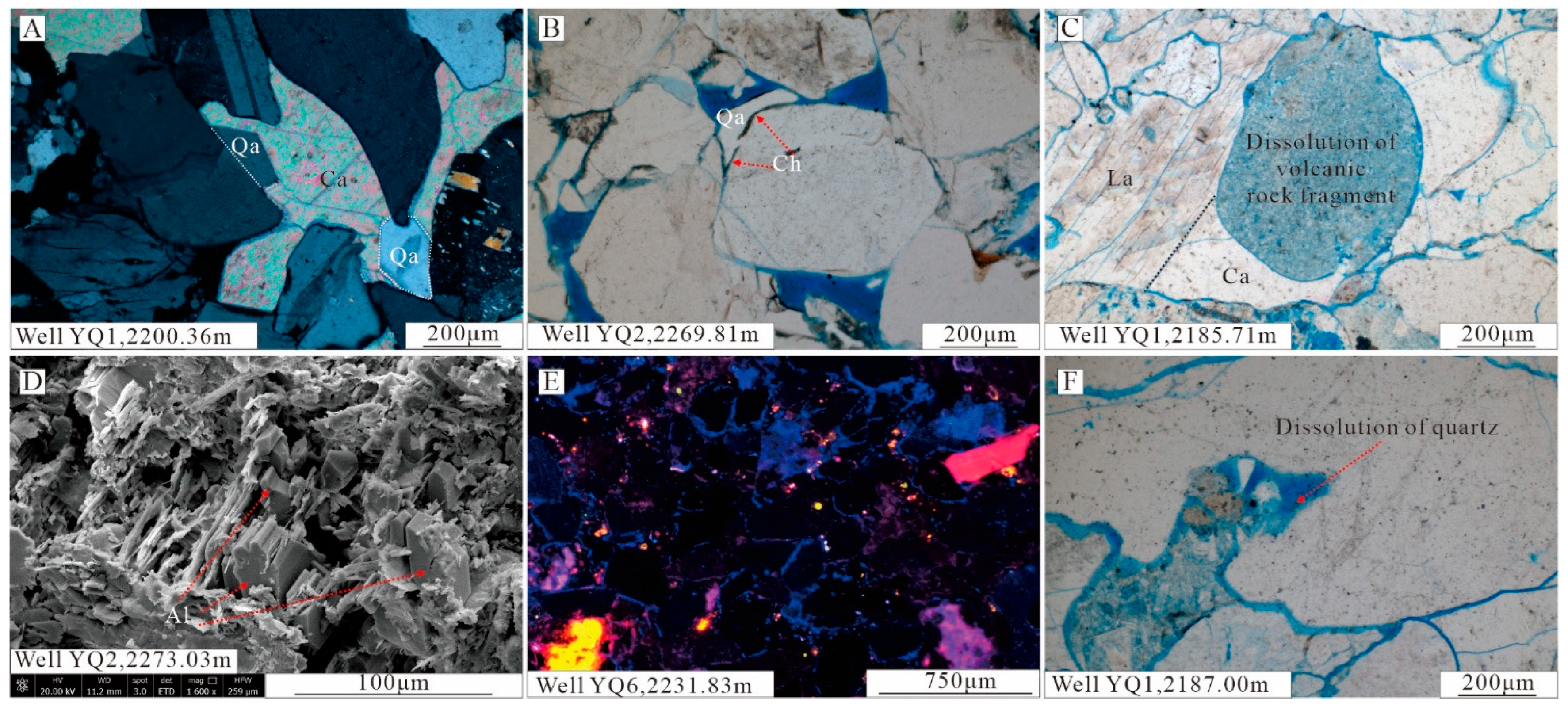

Calcite cement occurs primarily in two forms—basal cementation and pore-filling cementation—as observed in stained thin sections. Basal calcite cement typically formed prior to significant compaction, with detrital grains commonly showing a floating or point-contact texture (

Figure 7B). This type of cement shows distinct vertical zonation, being concentrated mainly at the tops, bases, and lateral margins of distributary channel sand bodies [

22]. In contrast, pore-filling calcite cement is more commonly developed in well-sorted, medium- to coarse-grained sandstones, and is characterized by orange-yellow luminescence under cathodoluminescence microscopy (

Figure 7C). This phase of cementation occurred during or after intense compaction, with most grains exhibiting linear contacts.

Quartz cement occurs in two primary forms: quartz overgrowths and authigenic quartz crystals that fill intergranular pores. Among these, the pore-filling authigenic quartz is the more significant.

Quartz overgrowths typically form around detrital quartz grains and consist of optically continuous quartz with the same crystallographic orientation as the host grain (

Figure 7D). Notably, these overgrowths are often discontinuous and represent only a minor portion of the total cement volume. Authigenic quartz commonly appears as highly euhedral microcrystals, occupying residual intergranular pores adjacent to detrital quartz (

Figure 7E) [

26]. The limited development of quartz overgrowths suggests inhibition, potentially by grain coatings.

Laumontite cementation exhibits multiple modes of occurrence, including basal, pore-filling, and grain-replacing types. Mineralogically, laumontite appears colorless and transparent under plane-polarized light, and exhibits first-order gray to white interference colors under cross-polarized light. However, its crystal morphology varies significantly among different occurrence types [

25,

44]. Some crystals show smooth faces and weak cleavage (

Figure 7E), while others develop two sets of nearly perpendicular cleavages (

Figure 7F). As a diagenetic mineral unique to the Shaximiao Formation in the Sichuan Basin, laumontite shows marked vertical differentiation, being enriched mainly in the lower member of the formation and rarely observed in the upper member [

25,

45].

4.4.3. Dissolution

Dissolution is widely developed in the clastic reservoirs of the study area, particularly affecting volcanic rock fragments and feldspar grains, ranging from partial to complete leaching. This pervasive process has led to the extensive development of secondary dissolution pores, which can be categorized into three main types:

(1) Dissolution pores in volcanic rock fragments: Volcanic rock fragments commonly show significant dissolution, and intense leaching can produce characteristic mold pore that replicate the shape of the original grains (

Figure 7G).

(2) Intragranular dissolution pores in feldspar: Feldspar grains exhibit irregular edge dissolution and residual structures, indicating that dissolution preferentially follows intragranular microfractures (

Figure 7H).

(3) Dissolution pores in laumontite cement: Laumontite is typically dissolved along its cleavage planes, forming a directionally aligned intergranular pore network (

Figure 7I). The development of these dissolution pores is a key differentiator between low-quality and high-quality reservoirs.

4.4.4. Altered Clay Minerals

XRD analysis of clay minerals indicates that the total clay mineral content in the study interval ranges from 3% to 12%, with an average of 7.72%. The dominant assemblage consists of chlorite (21–54%) and illite/smectite mixed layers (14–56%), accompanied by minor illite (9–17%) and kaolinite (7–24%). Notably, the clay mineral composition exhibits distinct vertical zonation, and its content variations show a strong correlation with reservoir physical properties (

Figure 8). Critically, the impact of clay minerals on reservoir quality is highly dependent on their morphology and location.

Authigenic chlorite occurs in two main morphological types [

46]: (1) Grain-coating type: Present as radial or rosette-shaped aggregates vertically attached to grain surfaces, forming a semi-continuous thin film (

Figure 9A). This type can inhibit quartz cementation, thereby helping to preserve porosity. (2) Pore-filling type: Composed of stacked flaky crystals filling residual primary pores and feldspar dissolution pores (

Figure 9B). Scanning electron microscope (SEM) observations reveal that kaolinite commonly occurs as booklet-shaped aggregates, enriched in intergranular pore spaces (

Figure 9C). Its formation is likely related to the acidic dissolution of aluminosilicate minerals [

47,

48]. Illite/smectite mixed-layer minerals typically display a honeycomb-like structure and can be further classified based on their occurrence: (1) Grain-coating type: Forms continuous film-like coatings on the surfaces of detrital grains (

Figure 9D). (2) Pore-filling type: Appears as curved, flaky aggregates filling intergranular pores (

Figure 9E). Both types develop nanoscale intercrystalline pore networks. Illite usually occurs as fibrous or filamentous crystals extending from grain edges into adjacent pore spaces (

Figure 9F), forming three-dimensional reticulate bridge structures. These fibrous and pore-filling habits, while creating micro-porosity, drastically reduce permeability by blocking pore throats.

4.5. Fluid Inclusions

Homogenization temperatures of fluid inclusions serve as key geochemical indicators for reconstructing hydrocarbon charging events and diagenetic temperatures of authigenic minerals [

49,

50]. In this study, two important datasets of fluid inclusions in reservoir sandstones from the central Sichuan Basin were compiled through literature review.

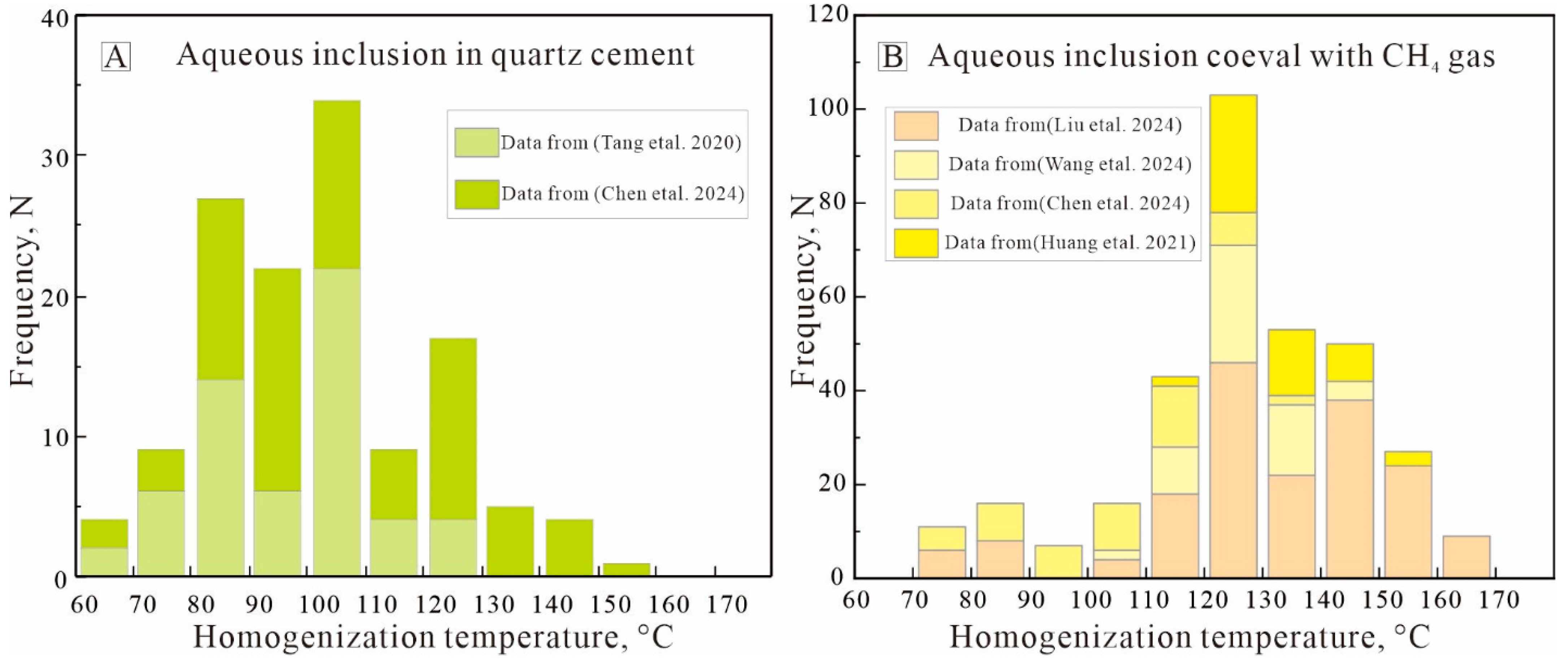

A total of 132 valid homogenization temperature data points were collected from aqueous inclusions hosted in quartz cement, and 335 data points from aqueous inclusions coeval with CH

4 gas hosted in quartz overgrowths and microfractures. The homogenization temperatures of aqueous inclusions show a bimodal distribution, with peaks at 80–110 °C (62.88%) and 110–140 °C (23.48%) (

Figure 10A). In contrast, methane-bearing brine inclusions exhibit a unimodal, near-normal distribution, with 74.33% of data concentrated in the 110–150 °C range (

Figure 10B). This distinct unimodal distribution of the methane-bearing inclusions provides a robust record of the primary hydrocarbon charging event, constraining it to the 110–150 °C temperature interval, which corresponds to the middle to late Cretaceous.

5. Discussion

5.1. Diagenetic Events

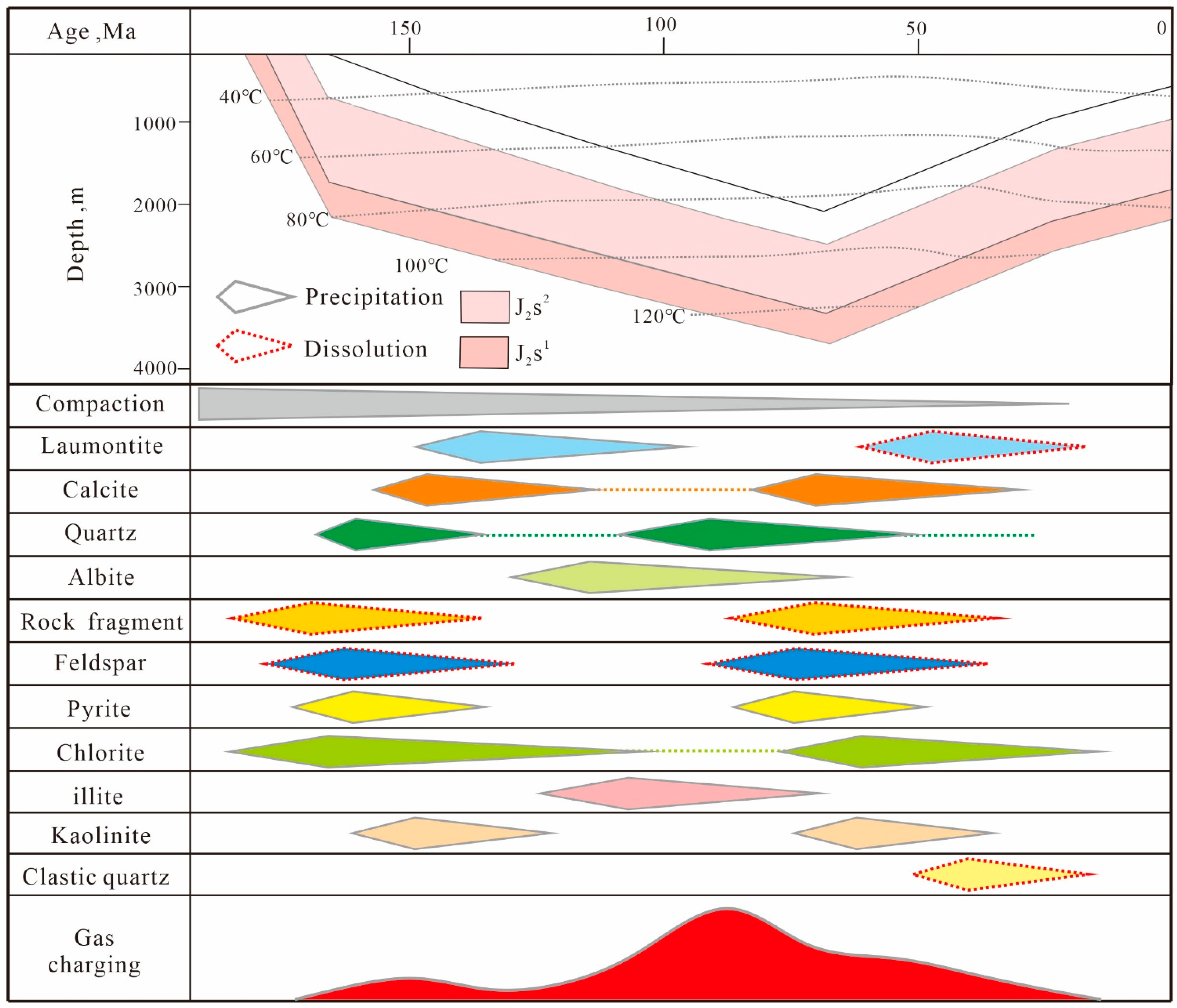

5.1.1. Early Diagenetic Stage

Early diagenesis typically occurs under shallow burial conditions, at temperatures below 70 °C and depths shallower than 2000 m [

52,

53]. The early diagenetic sequence in the Shaximiao Formation sandstones is characterized by the following features: (1) mechanical compaction; (2) formation of chlorite grain coatings; (3) hydrolysis of volcanic rock fragments; (4) precipitation of authigenic quartz microcrystals; and (5) early cementation by laumontite and calcite.

Although feldspar dissolution pores are not prominently observed in intervals dominated by basal laumontite and calcite cement, the presence of dissolution relics in volcanic rock fragments and feldspar grains (

Figure 7B) suggests that these dissolution events preceded laumontite–calcite cementation, likely driven by meteoric water leaching during early diagenesis. This dissolution was commonly accompanied by the precipitation of authigenic silica, forming a typical association of siliceous cementation and dissolution features (

Figure 11A,B).

Petrographic evidence indicates a transition in grain contact styles from point to linear contact, along with deformation features in plastic rock fragments (

Figure 7B), collectively pointing to significant mechanical compaction. Notably, syntaxial calcite crystals developed within uncompacted primary pores (

Figure 7B) suggest that early carbonate cementation occurred under weak compaction conditions. This early calcite cementation, while locally occluding porosity, likely imparted a degree of rigidity to the sand framework, thereby mitigating subsequent compactional porosity loss. Although no prominent feldspar dissolution pores are observed in zones dominated by basal laumontite and calcite cementation, the presence of dissolution relics in volcanic rock fragments and feldspar grains (

Figure 7B) implies that these dissolution events preceded the laumontite–calcite cementation stage. This dissolution was likely driven by meteoric water leaching during early diagenesis [

26], and was commonly accompanied by the precipitation of authigenic quartz microcrystals (

Figure 11A,B).

Cast thin section and SEM observations further demonstrate that grain-coating chlorite was one of the earliest clay minerals to form under weak compaction conditions during the early diagenetic stage [

46,

54]. Its formation predates that of authigenic quartz microcrystals (

Figure 11C). The early formation of chlorite coatings is critical, as it presets the reservoir for subsequent diagenetic pathways with profound implications for porosity preservation, a point we elaborate on in

Section 5.2.3. Additionally, basal pyrite cementation has been locally observed in the study area [

55], indicating minor early sulfate reduction processes.

5.1.2. Mesogenetic Stage

Mesogenetic diagenesis occurs under deeper burial conditions, typically at depths > 2000 m and temperatures > 70 °C [

52,

56]. The mesogenetic sequence in the Shaximiao Formation includes the following key processes: (1) continued mechanical compaction; (2) transformation of smectite to illite; (3) late-stage dissolution of volcanic rock fragments and feldspar; (4) development of quartz overgrowths; (5) albitization; (6) late-stage calcite cementation; (7) pore-filling precipitation of chlorite and kaolinite; (8) dissolution of quartz grains.

The illitization of smectite represents the core clay mineral transformation during this stage. With increasing burial depth and temperatures reaching 70–100 °C, smectite undergoes interlayer dehydration and releases Fe

2+, Mg

2+, and Ca

2+ ions. Through a transition from random to ordered illite/smectite (I/S) mixed layers, it ultimately transforms into illite, typically accompanied by silica precipitation in the form of quartz cement [

57,

58]. This coupled process of clay transformation and silica cementation is a well-established mechanism for porosity reduction in deeply buried sandstones. This transformation is coupled with hydrocarbon charging. The influx of organic acids renders the reservoir fluids acidic, promoting selective dissolution of volcanic rock fragments, feldspar, and early-stage laumontite (

Figure 11D,E). The resulting dissolution products facilitate the precipitation of kaolinite, albite, and quartz overgrowths [

48,

59]. However, the presence of chlorite grain coatings can inhibit quartz overgrowth development, resulting in significant spatial heterogeneity in the degree of silica cementation [

54]. This observed heterogeneity underscores the long-term impact of early diagenetic chlorite on mesogenetic processes, effectively preserving porosity in coated regions while allowing cementation to proceed in uncoated areas. It should also be noted that the relative timing between laumontite and feldspar dissolution remains uncertain, and they may have occurred in close succession or partially overlapped.

As the acidic fluids were gradually neutralized and consumed, the system evolved toward a more alkaline environment, triggering two characteristic phases of cementation: (1) late-stage calcite precipitation within residual intergranular and dissolution pores; (2) recrystallization of chlorite, often expressed as rosette-shaped structures along grain-coating surfaces. Under extremely alkaline conditions, embayed dissolution textures developed along detrital quartz grain edges [

60,

61], leading to the formation of secondary dissolution pores (

Figure 11F). The occurrence of quartz dissolution, while less common than feldspar dissolution, signifies a shift to high-pH conditions and represents a final, locally significant phase of porosity generation.

In summary, the diagenetic evolution of the Shaximiao Formation reservoirs in the study area can be outlined as follows: mechanical compaction → early grain-coating chlorite → hydrolysis of volcanic rock fragments → precipitation of authigenic quartz microcrystals → early laumontite/early calcite cementation → formation of I/S mixed layers → early laumontite and feldspar dissolution → precipitation of kaolinite/quartz overgrowths/albite → crystallization of illite and recrystallized chlorite → late-stage calcite cementation → dissolution of detrital quartz grains (

Figure 12).

5.2. Impact of Diagenesis on Reservoir Quality

5.2.1. Compaction

Although the present burial depth of the Jurassic Shaximiao Formation reservoirs in the Sichuan Basin is approximately 2000 m, basin tectonic evolution analysis indicates that the historical maximum burial depth exceeded 3500 m [

43]. This significant difference between present and maximum burial depths implies that the reservoir sandstones have undergone intense mechanical compaction. Compaction led to plastic deformation of ductile grains, grain rearrangement, and fracturing of rigid grains during burial, all contributing to the progressive reduction in primary porosity [

20,

62].

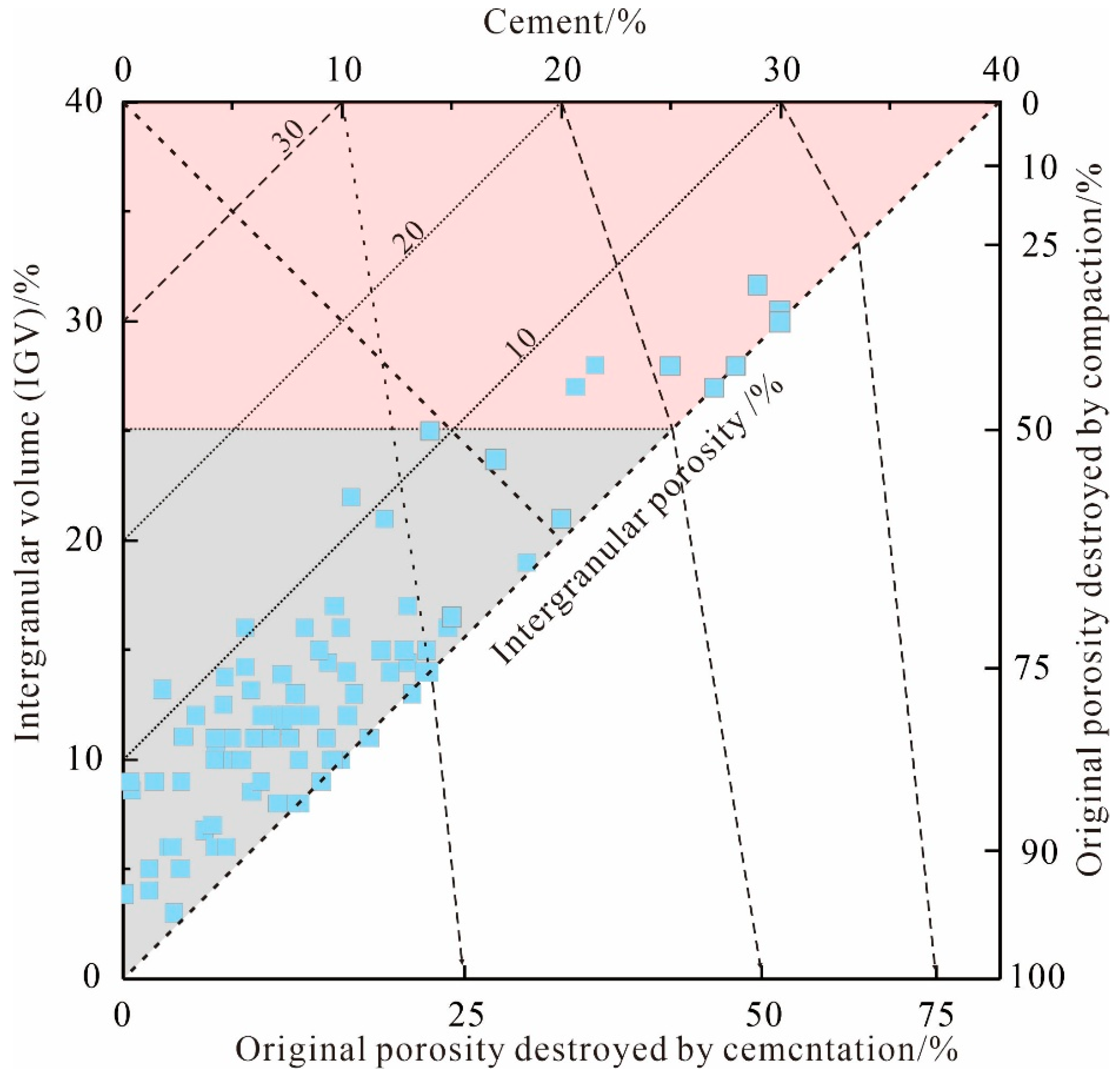

The dominant role of compaction is quantitatively unequivocal. Quantitative analysis of diagenetic parameters for the Shaximiao sandstones reveals that the cross-plot of intergranular volume (IGV) versus cement content shows that most samples fall within the compaction-dominated zone (

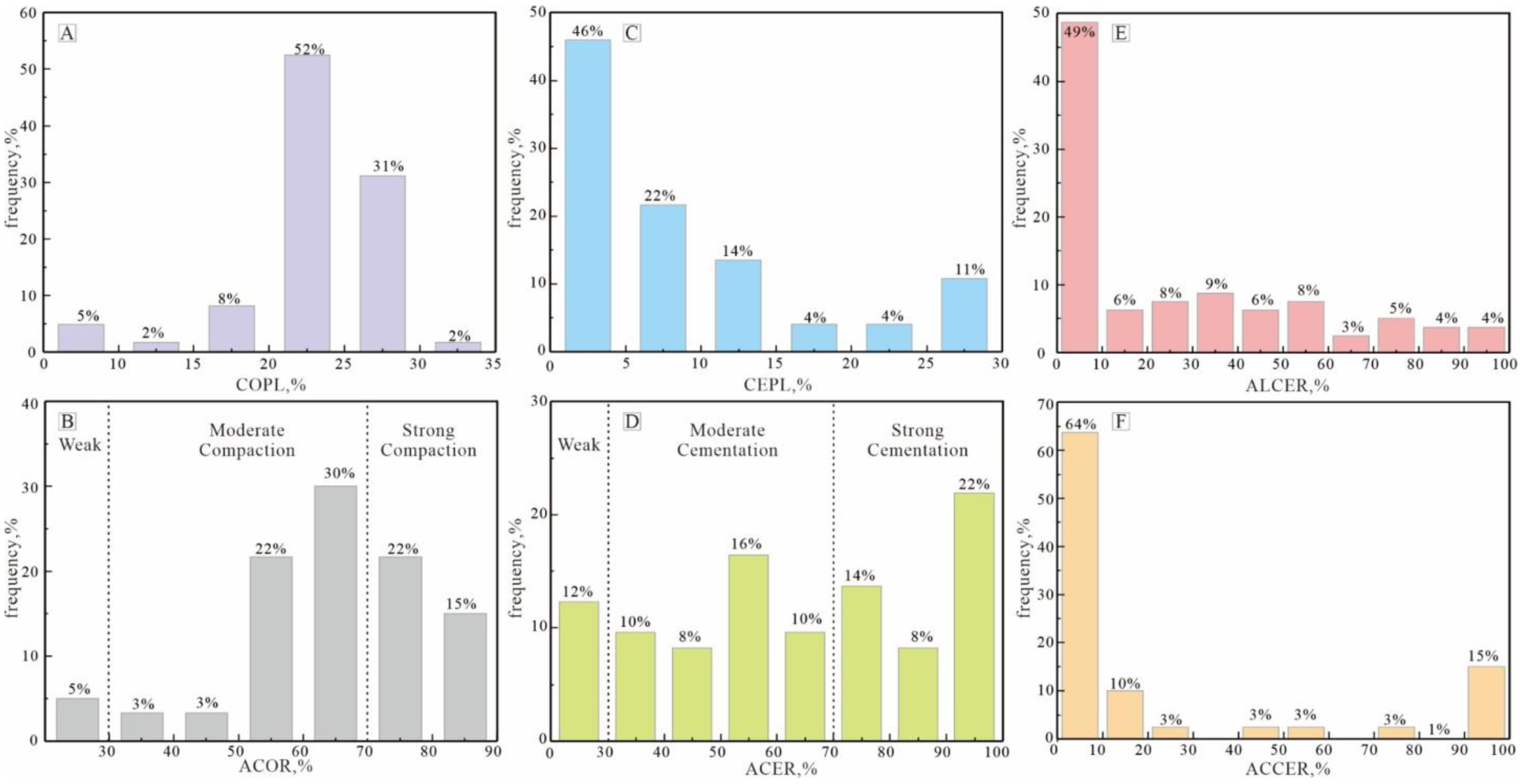

Figure 13), indicating that mechanical compaction is the primary control on porosity reduction in the study area. Statistical data show that 83% of the samples exhibit a compactional porosity loss (COPL) ranging between 20% and 30% of the original (

Figure 14A), while the apparent compaction rate (ACOR) predominantly falls within the 50–90% range (

Figure 14B). Notably, cast thin section observations frequently show plastic rock fragments squeezed into the rigid grain framework (

Figure 6B), providing direct petrographic evidence of intense compaction.

Quantitative calculations indicate that compaction has resulted in an average porosity loss of 22.91 percentage points, further confirming that mechanical compaction is the dominant factor controlling reservoir tightness in this area.

5.2.2. Cementation

Cementation is one of the most critical diagenetic mechanisms controlling porosity evolution in clastic reservoirs. In the Shaximiao Formation, the cementation-induced porosity loss (CEPL) ranges from 0% to 30%. Statistical analysis shows that approximately 80% of the samples have CEPL values below 15%, and nearly 90% fall below 20% (

Figure 14C). The apparent cementation ratio (ACER) exhibits a wide distribution, ranging from 0% to 100%, with most samples falling within the moderate (30–70%) to strong cementation (>70%) zones (

Figure 14D), indicating that cementation of moderate to high intensity is widely developed in the study area.

The contributions of different cement types to porosity loss vary significantly: (1) The apparent laumontite cementation ratio (ALCER) averages 25.40%, with 77.5% of samples showing values below 50% (

Figure 14E). (2) The apparent calcite cementation ratio (ACCER) averages 24.06%, with about 77% of samples below 30%, although 15.0% of samples display exceptionally high values (>90%) (

Figure 14F). (3) The apparent quartz cementation ratio (AQCER) is relatively minor, with an average of only 5.10% and a maximum value of 63.04%.

Comprehensive calculations indicate that cementation leads to an average porosity loss of approximately 7.0 percentage points, which is significantly lower than that caused by compaction. Among all cement types, laumontite and calcite are the primary contributors to porosity reduction and are considered the key porosity-destroying agents in the study area.

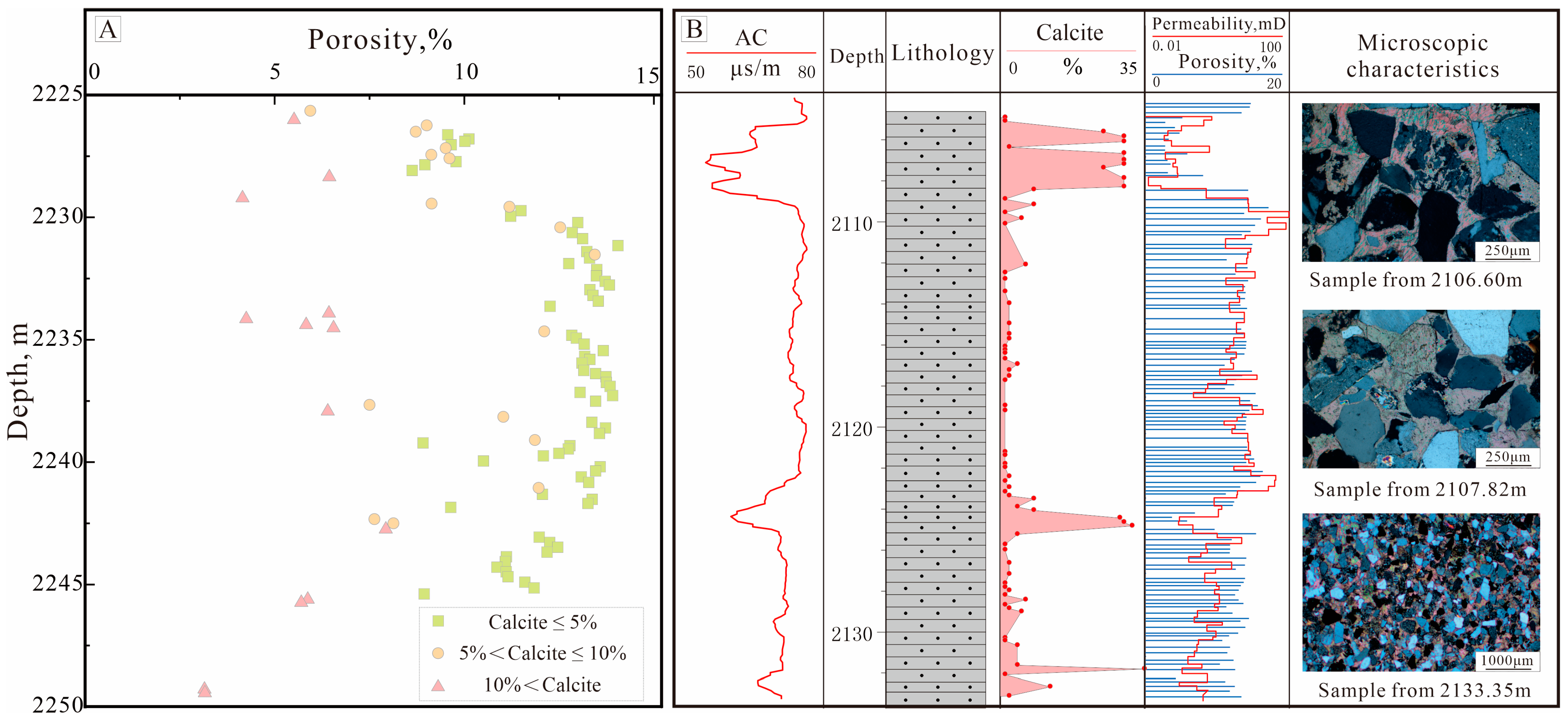

It is noteworthy that calcite cementation exhibits pronounced spatial heterogeneity. In intervals where calcite is well developed, it commonly occurs as syntaxial pore-filling cement, drastically reducing reservoir quality. Petrographic observations and petrophysical data indicate that sandstone intervals with abundant calcite cement display a “double-low” pattern—characterized by both low porosity and low permeability. When calcite content exceeds 10%, its influence on reservoir properties becomes significant, with porosity reduced by 40–60% of the original compared to adjacent weakly cemented intervals (

Figure 15A). This selective cementation not only reduces effective storage space but also disrupts reservoir connectivity by forming dense, impermeable barriers within otherwise permeable layers (

Figure 15B) [

63].

5.2.3. Clay Minerals

Authigenic clay minerals—including chlorite, kaolinite, illite, and illite/smectite (I/S) mixed layers—are widely developed in the clastic reservoirs of the study area, and their occurrence modes exert a significant influence on reservoir quality [

10,

64]. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis shows that fibrous illite and honeycomb-textured I/S mixed layers are commonly observed within primary intergranular pores (

Figure 9E,F). These clay minerals tend to partition pore space and increase flow resistance, thereby degrading overall reservoir quality. In contrast, kaolinite is present in relatively minor quantities in the study area and exerts a limited impact on reservoir performance. Although intercrystalline microporosity within clay mineral aggregates is widely developed, the associated pore throats are extremely small and poorly connected, making it difficult to establish an effective seepage network. As a result, these minerals often block pore throats, leading to a significant reduction in permeability [

65].

Among various clay minerals, chlorite exhibits contrasting effects on reservoir quality due to its unique occurrence modes [

54,

66]. Pore-filling chlorite is considered a destructive diagenetic product, as it clogs pore throats and reduces porosity [

67]. In contrast, sandstone samples containing grain-coating chlorite in the study area exhibit an average porosity of 12%, significantly higher than that of quartz-cemented sandstones (7–9%), and are dominated by primary intergranular pores. The presence of chlorite coatings promotes the preservation of primary pores and the development of secondary dissolution pores, making it a beneficial diagenetic feature [

26].

The pore-preserving mechanism of chlorite coatings involves several aspects: (1) enhancing the rock’s resistance to mechanical compaction [

68]; (2) inhibiting the formation of quartz overgrowths [

18,

54]; (3) facilitating the migration of acidic pore fluids [

69]. In particular, this study highlights that chlorite coatings play a critical role in preserving primary porosity by inhibiting quartz overgrowth. When continuous chlorite rims are developed around detrital grains, they suppress quartz crystallization at grain contacts through combined steric hindrance and chemical inhibition mechanisms [

26]. Microscopic analysis shows that authigenic quartz crystals are selectively precipitated only in discontinuous or locally ruptured chlorite coatings (

Figure 11B). This selective inhibition allows a large proportion of primary intergranular pores to be effectively preserved. This result confirms its applicability in the context of the Shaximiao Formation, where chlorite coating is a key differentiator between conventional and tight reservoir intervals.

The pore-preserving effect of chlorite grain coatings through the inhibition of quartz cementation is a globally recognized mechanism [

54,

69]. Our findings from the Shaximiao Formation provide a robust confirmation of this model in a terrestrial sedimentary context. The effectiveness of chlorite coatings in the Shaximiao Formation appears comparable to that reported in high-quality marine sandstone reservoirs, such as the Lower Cretaceous Greensand in the North Sea [

70], underscoring the universal value of this diagenetic feature for porosity prediction across different depositional environments.

5.2.4. Dissolution

The dissolution of minerals within sandstones, which generates secondary porosity, is generally considered a constructive diagenetic process that can enhance reservoir quality [

47,

71,

72]. Our results demonstrate that dissolution represents the most significant mechanism for porosity enhancement in the study area. Thin-section observations and quantitative analyses reveal four main types of dissolution features in the studied interval: (1) Selective dissolution of feldspar grains; (2) Matrix dissolution of volcanic rock fragments; (3) Partial dissolution of laumontite cement; and (4) Dissolution of quartz overgrowths. The resulting pore types include intragranular dissolution pores within detrital grains, moldic pores, intergranular dissolution pores in laumontite, and intergranular dissolution voids associated with quartz. The secondary porosity of the reservoir sandstones ranges from 2% to 8%, with an average value of 5.51%. This indicates that the strata have undergone moderate to intense dissolution, which has effectively contributed to porosity preservation and may delay the progression of reservoir densification. Notably, the dissolution of laumontite cement is a particularly effective process, as it can re-open interconnected pore networks that were previously occluded.

5.3. Coupling Between Reservoir Densification and Hydrocarbon Charging

5.3.1. Hydrocarbon Accumulation Timing

The accumulation history of hydrocarbons in the Shaximiao Formation was reconstructed based on the homogenization temperatures of methane-bearing fluid inclusions. A total of 335 valid measurements from methane-rich brine inclusions indicate a unimodal normal distribution, with 74.33% of the data falling within the 110–150 °C range (

Figure 10B). This thermal signature reveals that the Shaximiao Formation in the central Sichuan Basin experienced a single-stage hydrocarbon charge event. The timing of this accumulation corresponds to the middle to late Cretaceous, approximately 88–68 million years ago, coinciding with the period of maximum burial depth (

Figure 12) [

31].

5.3.2. Reservoir Densification and Hydrocarbon Charging

Based on a comprehensive analysis of reservoir properties, diagenetic assemblages, and their relationship with hydrocarbon migration, the Shaximiao Formation sandstones can be classified into three reservoir types: Type I, Type II, and Type III (

Table 1). The evolution of porosity for each type has been reconstructed to evaluate the coupling between reservoir compaction and hydrocarbon charge.

Type I reservoirs represent a “hydrocarbon charging before densification” model, with lithologies dominated by fine- to medium-grained sandstones. Based on diagenetic evolution, Type I reservoirs can be further subdivided into I-A and I-B subtypes: (1) Type I-A reservoirs underwent moderate compaction and weak cementation. The dominant diagenetic product is chlorite rims around detrital grains. Porosity reconstruction indicates that porosity during hydrocarbon charging exceeded 10%, and a significant portion of primary intergranular porosity is still preserved today (

Figure 16A). (2) Type I-B reservoirs experienced moderate to strong compaction. Although early laumontite cementation and chlorite rim development caused some intergranular porosity loss, porosity remained around 10% during hydrocarbon emplacement. Subsequent dissolution significantly enhanced porosity to the current level of 10–13% (

Figure 16B).

Type II reservoirs exhibit a “simultaneous charging and densification” evolution. Present porosity ranges from 9% to 11%. These reservoirs had already experienced moderate to strong compaction and cementation prior to hydrocarbon emplacement. Notably, organic acid fluids associated with hydrocarbon influx caused extensive dissolution of feldspar and laumontite. However, this pore-enhancing effect was offset by intensive diagenetic transformation of aluminosilicate minerals, including the precipitation of authigenic albite and microcrystalline quartz, ultimately leading to tight reservoir conditions during the charging stage (

Figure 16C).

Type III reservoirs follow a “densification before charging” model and can be further divided into three subtypes based on their dominant tightness-controlling factors: (1) Type III-A reservoirs are primarily controlled by early laumontite cementation. Although they experienced moderate to strong late-stage dissolution, the original tight nature of the reservoir was not fundamentally altered (

Figure 16D). (2) Type III-B reservoirs are characterized by strong mechanical compaction, where plastic lithic fragments were deformed and compacted into the framework, severely reducing primary porosity. This was compounded by moderate cementation from calcite and authigenic quartz, resulting in early-stage densification (

Figure 16E). (3) Type III-C reservoirs exhibit extensive early interlocking calcite cementation, which completely occluded the reservoir space and prevented effective hydrocarbon storage (

Figure 16F).

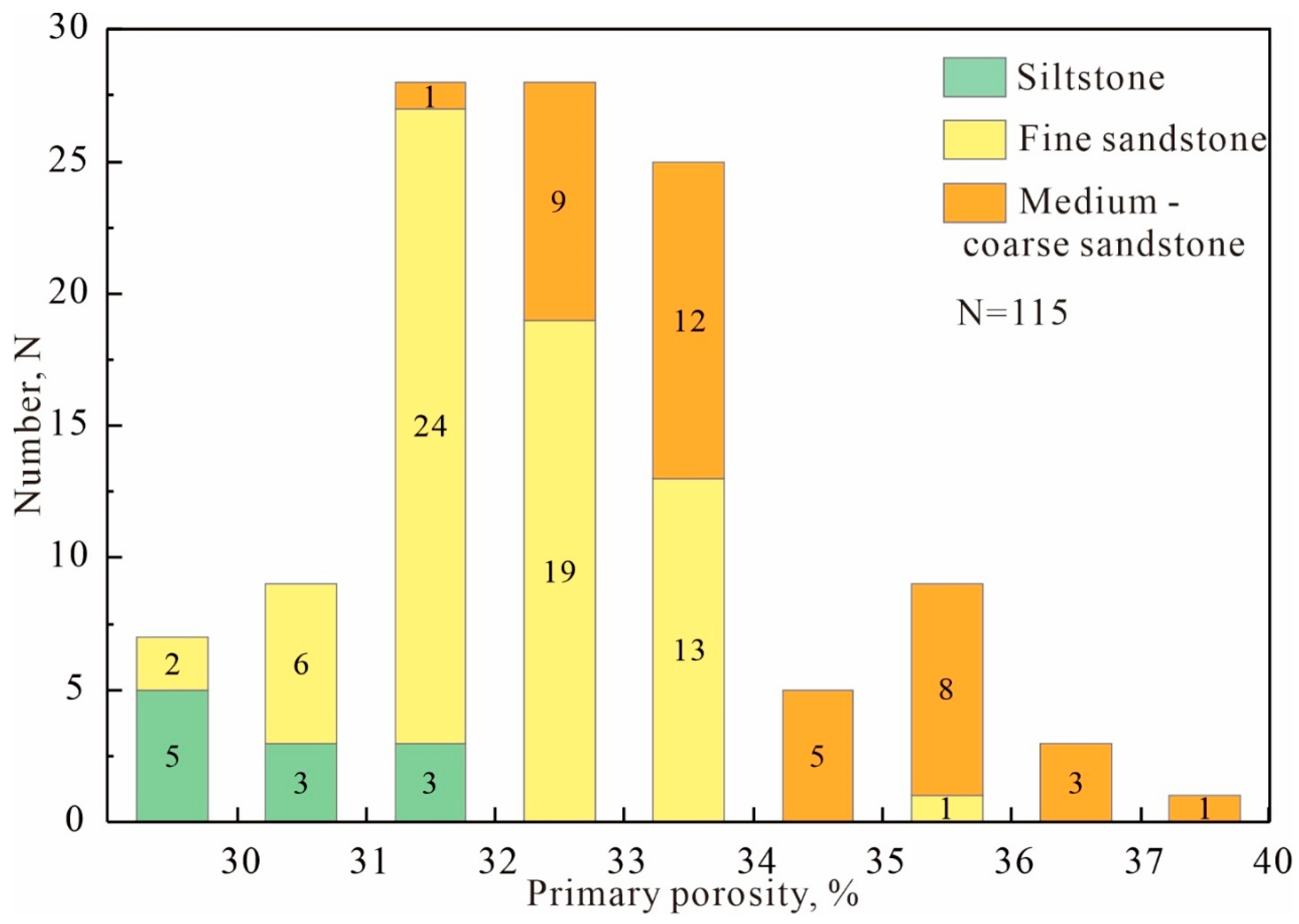

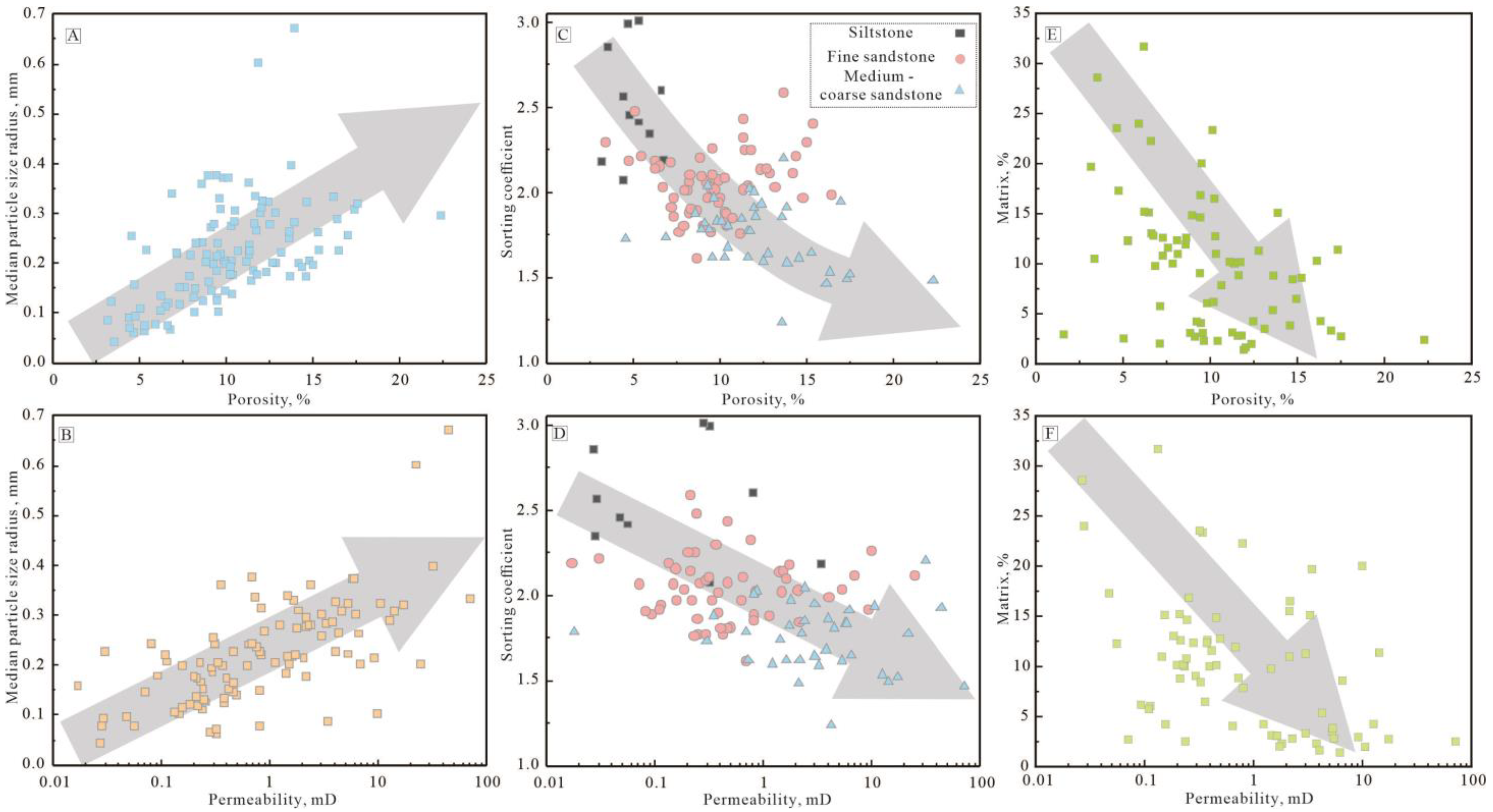

5.4. Influence of Sedimentary Characteristics on Reservoir Quality

Comparative analysis of lithologies shows that the average sorting coefficients of siltstone, fine sandstone, and medium–coarse sandstone are 2.72, 2.06, and 1.76, respectively, with corresponding average primary porosities of 30.13%, 32.11%, and 34.09%. This dataset reveals a co-evolutionary trend in which increasing grain size corresponds with better sorting and higher primary porosity (

Figure 17). Owing to their coarser grain size, better sorting, and higher initial porosity, medium–coarse sandstones constitute the most favorable reservoir lithofacies.

To systematically elucidate the controls of sedimentary processes on reservoir properties, a statistical model was constructed to quantify the relationships between median grain radius, sorting coefficient, and both porosity and permeability (

Figure 18). The results indicate a strong positive correlation between both porosity and permeability and the median grain size (

Figure 18A,B). As the sorting coefficient decreases from 3.0 to 1.5, porosity drops by approximately 10% (

Figure 18C), while permeability increases by nearly two orders of magnitude (

Figure 18D), indicating that permeability is more sensitive to sorting quality.

Matrix content has a marked negative impact on reservoir quality. In the central Sichuan Basin, the matrix content of Shaximiao Formation sandstones typically ranges from 0 to 15%. Both porosity and permeability exhibit a significant declining trend with increasing matrix content (

Figure 18E,F). Matrix material deposited during sedimentation fills intergranular pores and enhances compaction, thereby significantly degrading reservoir quality.

5.5. Genesis of High-Quality Reservoirs

Integrated core and logging data indicate that the reservoir exhibits significant vertical heterogeneity, with its physical property evolution controlled by the coupled effects of sedimentation and diagenesis (

Figure 19).

Firstly, sedimentation determines the sand-to-mud ratio and the distribution of original porosity. Thick sandstone intervals generally possess a higher initial porosity foundation. The Shaximiao Formation in the Sichuan Basin represents a typical shallow-water delta to fluvial depositional system. Sand bodies associated with distributary channels and subaqueous distributary channels were deposited under high-energy hydrodynamic conditions. These environments favored the formation of sandstones characterized by relatively coarser grain sizes, better sorting, lower contents of plastic fragments and matrix, and higher compositional maturity. Such “coarse-grained lithofacies” developed in high-energy channels typically exhibit higher original porosity (

Figure 17). Moreover, during the burial diagenetic stage, these facies experienced relatively limited porosity loss due to compaction alone, which contributed to better preservation of primary pores and the development of more secondary pores. These factors collectively provided the foundational conditions necessary for the formation of present-day high-quality reservoirs.

Secondly, diagenetic compaction and cementation are the dominant factors leading to reservoir densification. Microscopic observations reveal abundant carbonate and quartz cements filling intergranular pores, accompanied by the oriented distribution of clay minerals, resulting in generally low permeability (mostly below 1 mD). The Shaximiao Formation hosts typical pore-type reservoirs, dominated by residual primary intergranular pores with secondary dissolution pores playing a subordinate role. The preservation of primary pores and the development of secondary pores are critical to the formation of high-quality reservoirs. Diagenetic processes closely related to these features include the development of chlorite rims, the precipitation and subsequent dissolution of laumontite, and the selective dissolution of feldspars and volcanic rock fragments.

Chlorite rims, as a prominent early diagenetic product, contribute significantly to the preservation of primary intergranular pores through a dual mechanism involving both physical pore shielding and chemical isolation. Moderately developed chlorite rims are a defining feature of Type I-A “hydrocarbon charging before densification” high-quality reservoirs (

Figure 16A). The key mechanisms include: (1) Physical shielding: The rim occupies the surface of detrital grains, effectively preventing the nucleation and growth of quartz overgrowths on grain contacts [

73,

74]; (2) Chemical isolation: The rim acts as a barrier to silica-rich diagenetic fluids, thereby restricting quartz precipitation to locally ruptured zones of the rim and allowing a portion of the primary porosity to be retained [

18].

Laumontite commonly occurs as dispersed cement, partially occupying intergranular space and exhibiting a dual-stage diagenetic behavior: (1) In the early cementation stage, laumontite contributes to the formation of a rigid framework, which significantly mitigates porosity loss due to mechanical compaction. (2) In the dissolution stage, organic acids percolating along cleavage planes lead to the formation of connected secondary pores. When weak laumontite cementation coexists with chlorite rims, the combined effect is favorable for the formation of Type I-B high-quality reservoirs. However, under conditions of intense laumontite cementation, even substantial later-stage dissolution is insufficient to reverse early reservoir densification (

Figure 16D). This underscores the critical influence of initial cementation intensity on the ultimate reservoir quality and hydrocarbon charge potential. The dual role of laumontite—both preserver and destroyer of porosity—adds a layer of complexity to the diagenetic model and is a distinctive feature of this reservoir system.

Overall, the evolution of the Shaximiao Formation reservoir clearly demonstrates the decisive role of the sedimentary background in defining the foundational properties of the reservoir, the dominant control of diagenesis on pore evolution, and the critical contribution of fluid modification in locally forming high-quality reservoirs. This multi-factor coupled evolutionary mechanism not only reveals the intrinsic causes of reservoir heterogeneity but also provides a reliable geological basis for predicting the spatial distribution of high-quality gas accumulations in the study area.

6. Conclusions

(1) The tight sandstone reservoirs of the Shaximiao Formation developed within a shallow-water deltaic system, predominantly comprising siltstone, fine-grained sandstone, and medium- to coarse-grained sandstone. The dominant lithology is feldspathic lithic sandstone, with an average framework composition of quartz (64.56%), feldspar (12.16%), and rock fragments (23.27%). Measured petrophysical data indicate an average porosity of 10.58% and an average permeability of 2.54 mD, with strong heterogeneity across the reservoir.

(2) The complexity of reservoir quality results from the superposition of multiple diagenetic processes. The reservoirs underwent intense mechanical compaction, hydrolysis of volcanic rock fragments, cementation by authigenic quartz, laumontite, calcite, and chlorite, and later-stage dissolution. Among these, mechanical compaction was the dominant porosity-reducing process, accounting for an average porosity loss of 22.91%. Cementation contributed an additional ~7.0% porosity reduction, mainly due to laumontite and calcite. In contrast, dissolution created an average of 5.51% secondary porosity, which partially counteracted reservoir densification.

(3) Homogenization temperature data from methane-bearing aqueous inclusions show a unimodal normal distribution, with the main peak between 110 and 150 °C. This indicates that hydrocarbon charging mainly occurred during the middle to late Cretaceous (88–68 Ma), corresponding to the maximum burial depth and a period of tectonic stability. Based on the coupling relationship between reservoir densification and hydrocarbon charging, the reservoirs are classified into three types: Type I (hydrocarbon charging before densification), Type II (simultaneous charging and densification), and Type III (densification before charging).

(4) The formation of high-quality tight sandstone reservoirs (Type I) is jointly controlled by depositional and diagenetic factors. Medium- to coarse-grained sandstones deposited under high-energy conditions exhibit better sorting, lower matrix content, and higher original porosity, providing a favorable foundation for reservoir development. During burial diagenesis, moderately developed chlorite rims effectively inhibited quartz cementation, while weak, dispersed laumontite cement enhanced the rock’s resistance to compaction. These processes jointly preserved a significant proportion of primary intergranular porosity, ultimately contributing to the formation of high-quality reservoirs.

(5) This study establishes a ‘deposition-diagenesis-hydrocarbon charging’ genetic model that directly addresses the initial research objective of unraveling the genesis of high-quality reservoirs. The three-type classification scheme provides a practical predictive framework for identifying “sweet spots” in the Sichuan Basin, with significant implications for reducing exploration risk in similar tight gas plays worldwide. However, the application of this model may be limited by the spatial distribution of data points, and the precise quantification of dissolution fluxes warrants further investigation. Future work should focus on integrating seismic attributes with the diagenetic model to predict favorable zones laterally and on comparative studies with other basins to test and refine the proposed classification system.

Author Contributions

X.W.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft, and Project Administration. She led the design and organization of the study, integrated geological datasets, and prepared the manuscript draft. Y.Y.: Supervision, Funding Acquisition, and Writing—Review and Editing. He is the corresponding author and principal investigator who provided academic supervision, secured funding, and finalized the manuscript. S.C.: Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, and Data Curation. He performed data validation, geochemical modeling, and dataset management. L.Q.: Investigation, Resources, Visualization, and Writing—Review and Editing. He conducted sedimentological investigations, provided key field data, and contributed to figure preparation and manuscript refinement. X.G.: Methodology, Supervision, Writing—Review and Editing. He provided methodological oversight, technical supervision, and contributed to the interpretation and revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Oil & Gas Major Project, grant number 2025ZD1400400.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express sincere appreciation to the Exploration and Development Research Institute of PetroChina Southwest Oil & Gas field Company for providing critical geological samples essential to this study. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful critiques and constructive suggestions, which significantly strengthened the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xiaojuan Wang was employed by the company PetroChina Southwest Oil & Gas Field Company. Author Xu Guan was employed by the company PetroChina Southwest Oil & Gas Field Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zou, C.; Zhu, R.; Liu, K.; Su, L.; Bai, B.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, X.; Wang, J. Tight gas sandstone reservoirs in China: Characteristics and recognition criteria. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2012, 88–89, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.N.; Yang, Z.; Tao, S.Z.; Yuan, X.; Zhu, R.K.; Hou, L.H.; Wu, S.T.; Sun, L.; Zhang, G.S.; Bai, B.; et al. Continuous hydrocarbon accumulation over a large area as a distinguishing characteristic of unconventional petroleum: The Ordos Basin, North-Central China. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2013, 126, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassi, A.; de Franco, R.; Trippetta, F. High-resolution synthetic seismic modelling: Elucidating facies heterogeneity in carbonate ramp systems. Pet. Geosci. 2025, 31, petgeo2024-047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Cao, Y.; Qiu, L.; Chen, Z. Genetic mechanism of high-quality reservoirs in Permian tight fan delta conglomerates at the northwestern margin of the Junggar Basin, northwestern China. AAPG Bull. 2017, 101, 1995–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Wang, G.; Chai, Y.; Xin, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y. Deep burial diagenesis and reservoir quality evolution of high-temperature, high-pressure sandstones: Examples from Lower Cretaceous Bashijiqike Formation in Keshen area, Kuqa depression, Tarim basin of China. AAPG Bull. 2017, 101, 829–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, K.; Cao, Y.; Liu, K.; Wu, S.; Yuan, G.; Zhu, R.; Zhao, Y.; Hellevang, H. Geochemical constraints on the origins of calcite cements and their impacts on reservoir heterogeneities: A case study on tight oil sandstones of the Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation, southwestern Ordos Basin, China. AAPG Bull. 2019, 103, 2447–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yuan, G.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, K.; Zan, N.; Xi, K.; Wang, J. Current situation of oil and gas exploration and research progress of the origin of high-quality reservoirs in deep-ultra-deep clastic reservoirs of petroliferous basins. Acta Pet. Sin. 2022, 43, 112–140. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Pang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Z.; He, Z.; Qin, Z.; Fan, X. A review on pore structure characterization in tight sandstones. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 177, 436–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.H. Pore-throat sizes in sandstones, tight sandstones, and shales. AAPG Bull. 2009, 93, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Wang, G.; Ran, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Cui, Y. Impact of diagenesis on the reservoir quality of tight oil sandstones: The case of Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation Chang 7 oil layers in Ordos Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2016, 145, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Gong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, S.; Lyu, W. A review of the genesis, evolution, and prediction of natural fractures in deep tight sandstones of China. AAPG Bull. 2023, 107, 1687–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Li, H.; Jiang, L.; Hu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. Diagenesis and reservoir quality in tight gas bearing sandstones of a tidally influenced fan delta deposit: The Oligocene Zhuhai Formation, western Pearl River Mouth Basin, South China Sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 107, 278–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Tian, Y.; Liu, B.; Fan, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y. Formation conditions and controlling factors of high-quality reservoirs in the Middle Jurassic Shaximiao Formation of the southwestern Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. 2022, 42, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Saiag, J.; Brigaud, B.; Portier, E.; Desaubliaux, G.; Bucherie, A.; Miska, S.; Pagel, M. Sedimentological control on the diagenesis and reservoir quality of tidal sandstones of the Upper Cape Hay Formation (Permian, Bonaparte Basin, Australia). Mar. Pet. Geol. 2016, 77, 597–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Cao, Y.; Sun, P.; Zhou, L.; Li, W.; Fu, L.; Li, H.; Lou, D.; Zhang, F. Genetic mechanisms of Permian Upper Shihezi sandstone reservoirs with multi-stage subsidence and uplift in the Huanghua Depression, Bohai Bay Basin, East China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 124, 104784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.T.T.; Jones, S.J.; Goulty, N.R.; Middleton, A.J.; Grant, N.; Ferguson, A.; Bowen, L. The role of fluid pressure and diagenetic cements for porosity preservation in Triassic fluvial reservoirs of the Central Graben, North Sea. AAPG Bull. 2013, 97, 1273–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, S.; Lander, R.H.; Bonnell, L. Anomalously high porosity and permeability in deeply buried sandstone reservoirs: Origin and predictability. AAPG Bull. 2002, 86, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajdukiewicz, J.M.; Larese, R.E. How clay grain coats inhibit quartz cement and preserve porosity in deeply buried sandstones: Observations and experiments. AAPG Bull. 2012, 96, 2091–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, K.E.; Zwingmann, H.; Reyes, A.G.; Funnell, R.H. Diagenesis, porosity evolution, and petroleum emplacement in tight gas reservoirs, Taranaki Basin, New Zealand. J. Sediment. Res. 2007, 77, 1003–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kra, K.L.; Qiu, L.; Yang, Y.; Yang, B.; Ahmed, K.S.; Camara, M.; Khan, D.; Wang, Y.; Kouame, M.E. Sedimentological and diagenetic impacts on sublacustrine fan sandy conglomerates reservoir quality: An example of the Paleogene Shahejie Formation (Es4s Member) in the Dongying Depression, Bohai Bay Basin (East China). Sediment. Geol. 2022, 427, 106047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Deng, H.; Li, T.; Xu, Z.; Fu, M.; Ling, C.; Duan, B.; Chen, Q.; Chen, G. The conditions and modelling of hydrocarbon accumulation in tight sandstone reservoirs: A case study from the Jurassic Shaximiao formation of western Sichuan Basin, China. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 225, 211702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Luo, L.; Song, L.; Liu, F.; Wang, J.; Gluyas, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Zhu, C.; Mo, S.; et al. Differential precipitation mechanism of cement and its impact on reservoir quality in tight sandstone: A case study from the Jurassic Shaximiao formation in the central Sichuan Basin, SW China. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 221, 111263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Wen, L.; Cao, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Liang, Q. Evolution from shallow-water deltas to fluvial fans in lacustrine basins: A case study from the Middle Jurassic Shaximiao Formation in the central Sichuan Basin, China. Sedimentology 2024, 71, 1023–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Wen, L.; Wu, C.; Guan, X.; Wei, T.; Yang, X. Sedimentary system evolution and sandbody development characteristics of Jurassic Shaximiao Formation in the central Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. 2022, 42, 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q.; Yang, T.; Cai, L.; Ren, Q.; Dai, J. Porosity and permeability correction of laumontite-rich reservoirs in the first member of the Shaximiao Formation in the Central Sichuan Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 150, 106115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, Y.; Qiu, L.; Wang, X.; Habilaxim, E. Source of quartz cement and its impact on reservoir quality in Jurassic Shaximiao Formation in central Sichuan Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 159, 106543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qiu, N.; Xie, Z.; Yao, Q.; Zhu, C. Overpressure compartments in the central paleo-uplift, Sichuan Basin, southwest China. AAPG Bull. 2016, 100, 867–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Deng, B.; Zhong, Y.; Wen, L.; Sun, W.; Li, Z.; Jansa, L.; Li, J.; Song, J.; et al. Tectonic evolution of the Sichuan Basin, Southwest China. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2021, 213, 103470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Deng, B.; Li, Z.; Sun, W. The texture of sedimentary basin-orogenic belt system and its influence on oil/gas distribution: A case study from Sichuan basin. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2011, 27, 621–635. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Han, B. Superposed evolution of Sichuan Basin and its petroleum accumulation. Earth Sci. Front. 2015, 22, 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Pang, X.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Ge, X.; Cai, L.; Yang, T. Coupling relationship between tight sand reservoir formation mechanism and hydrocarbon charge in Shaximiao Formation of Tianfu gas field in the Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. 2024, 44, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Liu, M.; Xiao, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Song, L.; Cao, J.; Wang, J.; Li, T.; Liang, C. Differential accumulation characteristics and main controlling factors of the Jurassic Shaximiao Formation tight sandstone gas in the central Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2024, 35, 1014–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, L.; Qi, J.-F.; Zhang, M.-Z.; Wang, K.; Han, Y.-Z. Detrital zircon U-Pb ages of Late Triassic-Late Jurassic deposits in the western and northern Sichuan Basin margin: Constraints on the foreland basin provenance and tectonic implications. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2014, 103, 1553–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Bai, X.; Meng, Q.a.; Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y. Accumulation geological characteristics and major discoveries of lacustrine shale oil in Sichuan Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2022, 43, 885–898. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, W. Tectonic movements of the Yanshan-Himalayan period in the northern Longmenshan and their impact on tight gas accumulation of the Shaximiao formation in the Qiulin structure, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1296459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Zhang, S.; Hong, H.; Qin, C.; Li, Y.; Cai, C.; Kong, X.; Li, N.; Lei, D.; Lei, X.; et al. Source-reservoir rock assemblages and hydrocarbon accumulation models in the Middle-Lower Jurassic of eastern Sichuan Basin, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1207994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Tan, X.; Tu, L.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Liu, W. Control factors and pore evolution of tight sandstone reservoir of the Second Member of Shaximiao Formation in the transition zone between central and western Sichuan Basin, China. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. Sci. Technol. Ed. 2020, 47, 460–471. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg, S.N. Assessing the relative importance of compaction processes and cementation to reduction of porosity in sandstones-discussion-compaction and porosity evolution of pliocene sandstones, Ventura-basin, California-discussion. AAPG Bull. 1989, 73, 1274–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Houseknecht, D.W. Assessing the relative importance of compaction processes and cementation to reduction of porosity in sandstones. AAPG Bull. 1987, 71, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, W.; Wu, P.; Meng, S. Dissolution versus cementation and its role in determining tight sandstone quality: A case study from the Upper Paleozoic in northeastern Ordos Basin, China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 78, 103324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, S.n.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Y. Research Status and Advances in the Diagenetic Facies of Clastic Reservoirs. Adv. Earth Sci. 2013, 28, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Folk, R.L.; Andrews, P.B.; Lewis, D.W. Detrital sedimentary rock classification and nomenclature for use in New Zealand. N. Z. J. Geol. Geophys. 1970, 13, 937–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-H.; Tang, Y.-J.; Li, M.-J.; Hong, H.-T.; Wu, C.-J.; Zhang, J.-Z.; Lu, X.-L.; Yang, X.-Y. Quantitative evaluation of geological fluid evolution and accumulated mechanism: In case of tight sandstone gas field in central Sichuan Basin. Pet. Sci. 2021, 18, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Qiu, L.; Hu, Y.; Wu, C.; Chen, S. Genesis mechanism of laumontite cement and its impact on the reservoir of siliciclastic rock: A case study of Jurassic Shaximiao Formation in central Sichuan Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 165, 106873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Jiang, W.; Luo, L.; Gluyas, J.; Song, L.; Liu, J.; Qu, X.; Wang, J.; Gao, X.; Zhang, W.; et al. Variations of sedimentary environment under cyclical aridification and impacts on eodiagenesis of tight sandstones from the late Middle Jurassic Shaximiao Formation in Central Sichuan Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 161, 106699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Qiu, L.; Wang, X. Insights into the formation and growth of authigenic chlorite in sandstone: Analysis of mineralogical and geochemical characteristics from Shaximiao Formation, Sichuan Basin, SW China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 170, 107112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Cao, Y.; Jia, Y. Feldspar dissolution with implications for reservoir quality in tight gas sandstones: Evidence from the Eocene Es4 interval, Dongying Depression, Bohai Bay Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 150, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Cao, Y.; Schulz, H.-M.; Hao, F.; Gluyas, J.; Liu, K.; Yang, T.; Wang, Y.; Xi, K.; Li, F. A review of feldspar alteration and its geological significance in sedimentary basins: From shallow aquifers to deep hydrocarbon reservoirs. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 191, 114–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, M.; Parnell, J.; Mark, D.; Carr, A.; Przyjalgowski, M.; Feely, M. Evolution of hydrocarbon migration style in a fractured reservoir deduced from fluid inclusion data, Clair Field, west of Shetland, UK. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2008, 25, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, R.H. Fluid inclusions in sedimentary and diagenetic systems. Lithos 2001, 55, 159–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. A Study on the Mechanism of Natural GasAccumulation in the Shaximiao Formation of the Jurassicin the Central Sichuan Basin. Master’s Thesis, Yangtze University, Wuhan, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Morad, S.; Ketzer, J.M.; De Ros, L.F. Spatial and temporal distribution of diagenetic alterations in siliciclastic rocks: Implications for mass transfer in sedimentary basins. Sedimentology 2000, 47, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Kra, K.L.; Qiu, L.; Yang, B.; Dong, D.; Wang, Y.; Khan, D. Impact of sedimentation and diagenesis on deeply buried sandy conglomerate reservoirs quality in nearshore sublacustrine fan: A case study of lower Member of the Eocene Shahejie Formation in Dongying Sag, Bohai Bay Basin (East China). Sediment. Geol. 2023, 444, 106317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, R.H.; Griffiths, J.; Wooldridge, L.J.; Utley, J.E.P.; Lawan, A.Y.; Muhammed, D.D.; Simon, N.; Armitage, P.J. Chlorite in sandstones. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 204, 103105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, Y.; Qiu, L.; Wang, X.; Guan, X.; Liang, W.; Liu, J. Reservoir characteristics and controlling factors of Jurassic Shaximiao Formation in central Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2022, 33, 1597–1610. [Google Scholar]

- Worden, R.H.; Armitage, P.J.; Butcher, A.R.; Churchill, J.M.; Csoma, A.E.; Hollis, C.; Lander, R.H.; Omma, J.E. Petroleum reservoir quality prediction: Overview and contrasting approaches from sandstone and carbonate communities. In Proceedings of the Conference on Reservoir Quality of Clastic and Carbonate Rocks-Analysis, Modelling and Prediction, London, UK, 28–30 May 2014; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Peltonen, C.; Marcussen, O.; Bjorlykke, K.; Jahren, J. Clay mineral diagenesis and quartz cementation in mudstones: The effects of smectite to illite reaction on rock properties. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2009, 26, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, F.L.; Mack, L.E.; Land, L.S. Burial diagenesis of illite/smectite in shales and the origins of authigenic quartz and secondary porosity in sandstones. Geochim. Et Cosmochim. Acta 1997, 61, 1995–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.A.; Bandyopadhyay, D.N. Feldspar alteration and diagenetic characteristics of the Parsora sandstones, Son Basin, India. Gondwana Res. 2005, 8, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Qiu, L.; Chen, G. Alkaline diagenesis and its genetic mechanism in the Triassic coal measure strata in the Western Sichuan Foreland Basin, China. Pet. Sci. 2009, 6, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.W.; Jiang, Z.X.; Cao, Y.C.; Qiu, R.H.; Chen, W.X.; Tu, Y.F. Alkaline diagenesis and its influence on a reservoir in the Biyang depression. Sci. China Ser. D-Earth Sci. 2002, 45, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajdukiewicz, J.M.; Nicholson, P.H.; Esch, W.L. Prediction of deep reservoir quality using early diagenetic process models in the Jurassic Norphlet Formation, Gulf of Mexico. AAPG Bull. 2010, 94, 1189–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Luo, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Shi, H. Calcite-cemented concretions in non-marine sandstones: An integrated study of outcrop sedimentology, petrography and clumped isotopes. Sedimentology 2023, 70, 1039–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Shi, W.; Xie, X.; Zhang, W.; Qin, S.; Liu, K.; Busbey, A.B. Clay mineral content, type, and their effects on pore throat structure and reservoir properties: Insight from the Permian tight sandstones in the Hangjinqi area, north Ordos Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 115, 104281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, S.P.; Loucks, R.G. Diagenetic controls on evolution of porosity and permeability in lower Tertiary Wilcox sandstones from shallow to ultradeep (200–6700 m) burial, Gulf of Mexico Basin, USA. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2010, 27, 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, J.; Worden, R.H.; Utley, J.E.P.; Brostr, C.; Martinius, A.W.; Lawan, A.Y.; Al-Hajri, A.I. Origin and distribution of grain-coating and pore-filling chlorite in deltaic sandstones for reservoir quality assessment. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 134, 105326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Xi, K.; Cao, Y.; Niu, X.; Wu, S.; Feng, S.; You, Y. Chlorite authigenesis and its impact on reservoir quality in tight sandstone reservoirs of the Triassic Yanchang formation, southwestern Ordos basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 205, 108843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]