Development of a Korean-Specific Safety Checklist for Fishing Vessel Based on European Standards and Human and System Analysis Methods (SRK/SLMV, CREAM, STPA)

Abstract

1. Introduction

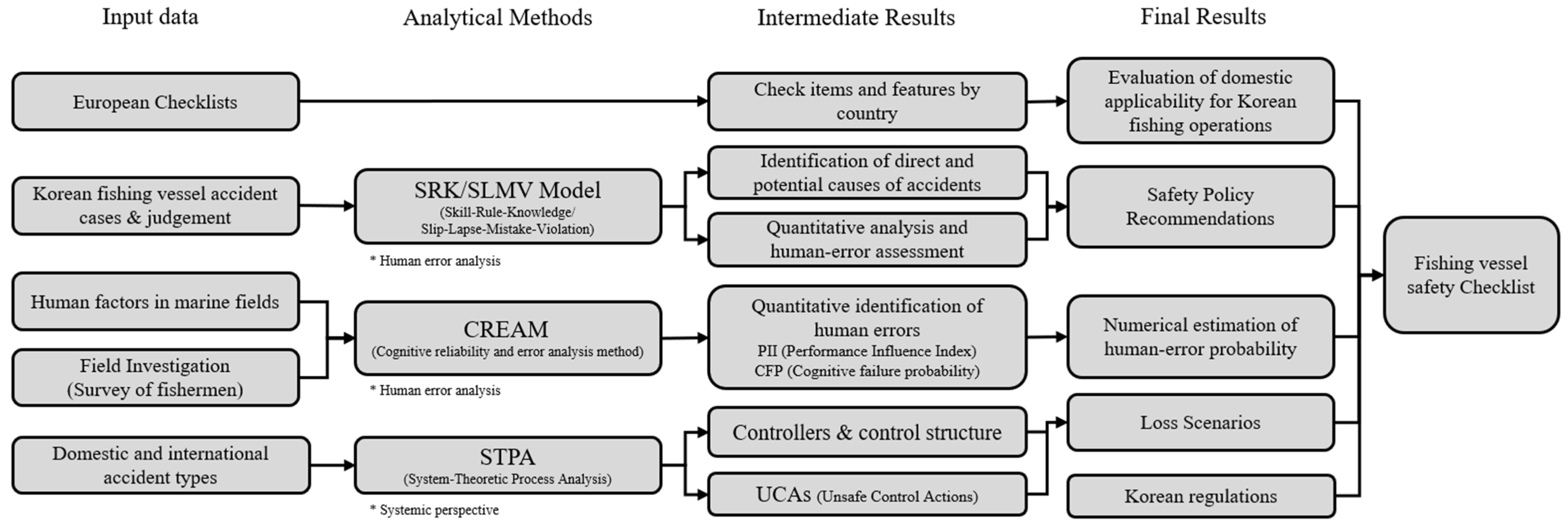

2. Methodology

3. Review and Characteristics

3.1. Review of European Checklists

3.1.1. Norway

3.1.2. Denmark

3.1.3. United Kingdom

3.1.4. Ireland

3.2. Korean Guidelines and Standards

3.3. SRK/SLMV Model

3.4. CREAM

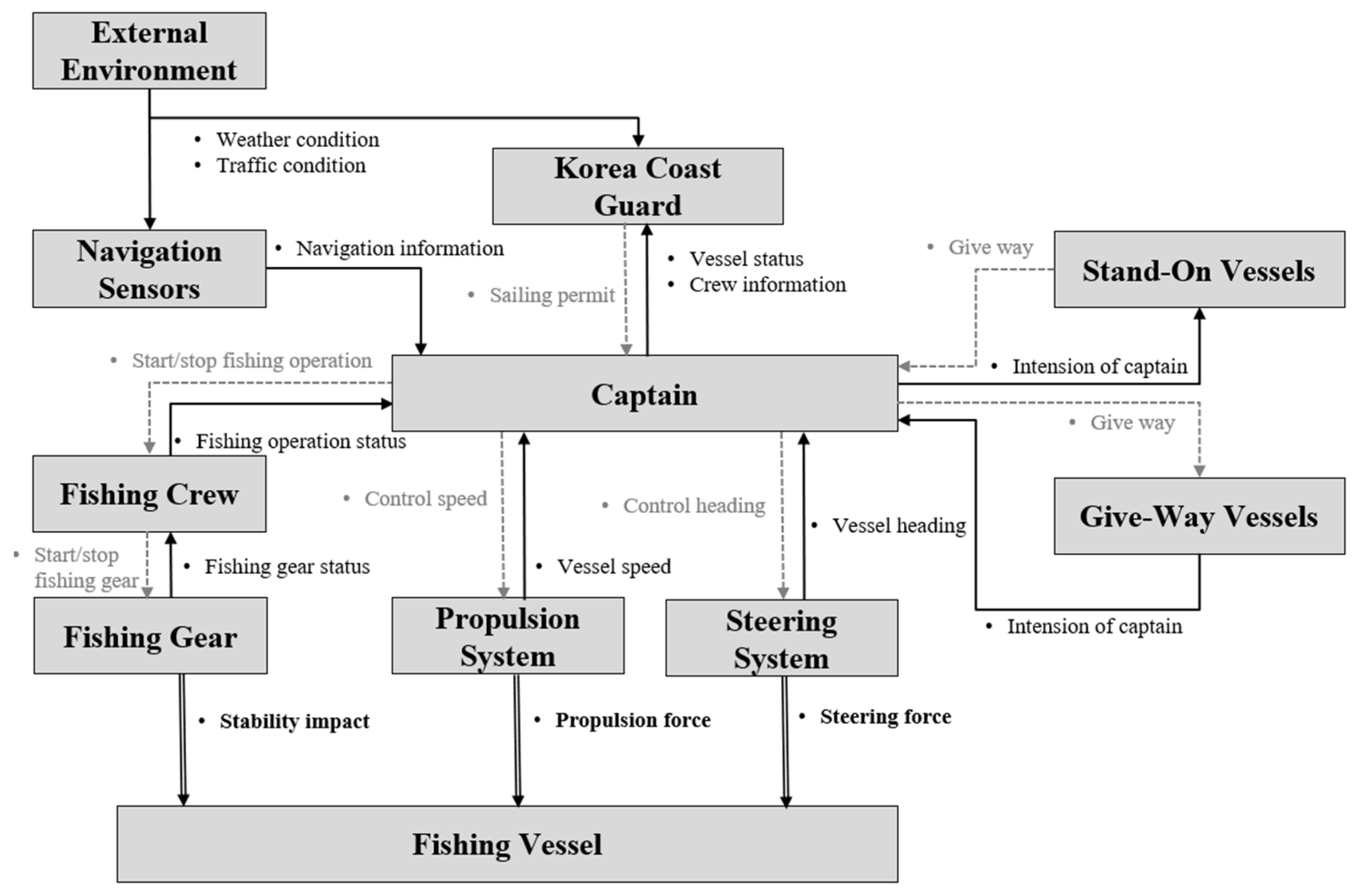

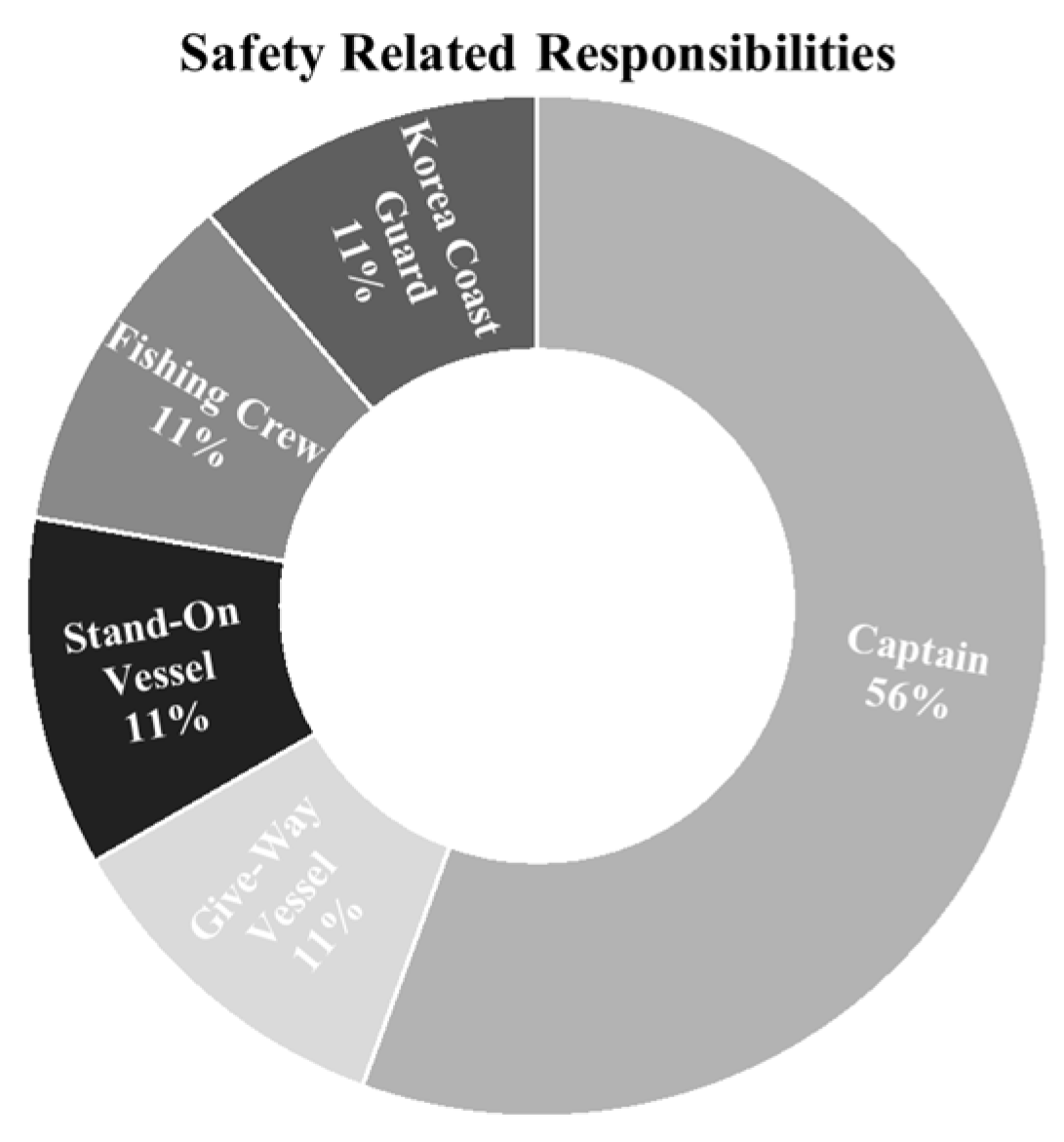

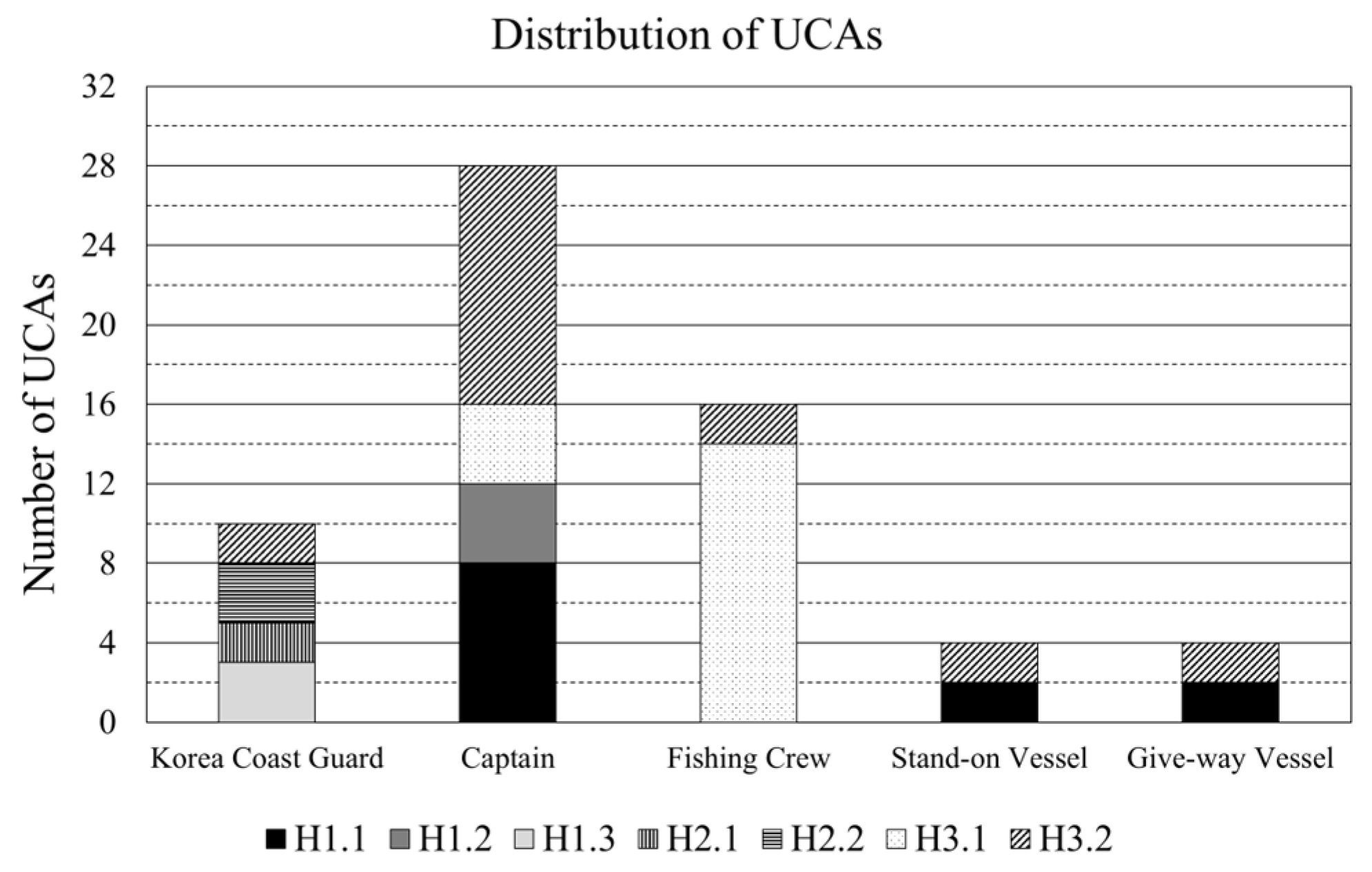

3.5. STPA

4. Development of the Safety Checklist

4.1. Safety Checklist Design

4.2. Reflected Components

4.2.1. European Checklists

4.2.2. Human and System Analysis Method

4.2.3. Domestic Regulations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Abbreviation | Full Term | Abbreviation | Full Term |

| AIS | Automatic Identification System | KOMSA | Korea Maritime Safety Authority |

| BN | Bayesian Network | LOLER | Lifting Operations and Lifting Equipment Regulations |

| CFP | Cognitive Failure Probability | LPG | Liquid Petroleum Gas |

| CPC | Common Performance Condition | MCA | Maritime and Coastguard Agency |

| CREAM | Cognitive Reliability and Error Analysis Method | MOB | Man Overboard |

| DMA | Danish Maritime Authority | MOF | Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries |

| EPIRB | Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon | NMA | Norwegian Maritime Authority |

| EU-OSHA | European Agency for Safety and Health at Work | NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization | PIF | Performance Influencing Factor |

| FISG | Fishing Industry Safety Group | PII | Performance Influence Index |

| FSA | Formal Safety Assessment | PPE | Personal Protective Equipment |

| FTA | Fault Tree Analysis | PUWER | Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations |

| GPS | Global Positioning System | RF | Random Forest |

| HSA | Health and Safety Authority (Ireland) | SLMV | Slip-Lapse-Mistake-Violation |

| ILO | International Labour Organization | SMS | Safety Management System |

| IMO | International Maritime Organization | SRK | Skill–Rule–Knowledge Model |

| IR | Individual Risk | STPA | System-Theoretic Process Analysis |

| ISM | International Safety Management | UCA | Unsafe Control Action |

| KIMST | Korea Institute of Marine Science & Technology Promotion | VHF | Very High Frequency Radio |

| KMST | Korea Maritime Safety Tribunal |

References

- Obeng, F.; Domeh, D.; Khan, F.; Bose, N.; Sanli, E. An Operational Risk Management Approach for Small Fishing Vessel. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 247, 110104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Du, W.; Feng, H.; Ye, Y.; Grifoll, M.; Liu, G.; Zheng, P. Identification of Risk Influential Factors for Fishing Vessel Accidents Using Claims Data from Fishery Mutual Insurance Association. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z. Research in Marine Accidents: A Bibliometric Analysis, Systematic Review and Future Directions. Ocean Eng. 2023, 284, 115048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caddy, J.F. A Checklist for Fisheries Resource Management Issues Seen from the Perspective of the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Piniella, F.; Fernández-Engo, M.A. Towards System for the Management of Safety on Board Artisanal Fishing Vessels: Proposal for Check-Lists and Their Application. Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, D.M.; Thunberg, E.M.; Felthoven, R.G. Guidance on Fishing Vessel Risk Assessments and Accounting for Safety at Sea in Fishery Management Design; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, K.; Kim, H.; Kwon, S. Analysis of Risk Assessment Methods in Norwegian Fishing Vessel Safety Legislation. J. Korean Soc. Fish. Technol. 2024, 60, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulzacchelli, M.T.; Bellantoni, J.M.; McCue-Weil, L.; Dzugan, J. Field Test of Two Mobile Apps for Commercial Fishing Safety: Feedback from Fishing Vessel Captains. Work 2023, 75, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EU-OSHA. European Guide for Risk Prevention in Small Fishing Vessels; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Bilbao, Spain, 2017; pp. 1–180. [Google Scholar]

- Hollá, K.; Kuricová, A.; Kočkár, S.; Prievozník, P.; Dostál, F. Risk Assessment Industry Driven Approach in Occupational Health and Safety. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1381879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Koo, K.; Lim, H.; Kwon, S.; Lee, Y. Analysis of Fishing Vessel Accidents and Suggestions for Safety Policy in South Korea from 2018 to 2022. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Kim, H.; Koo, K.; Kwon, S. Human Reliability Analysis for Fishing Vessels in Korea Using Cognitive Reliability and Error Analysis Method (CREAM). Sustainability 2024, 16, 3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwegian Maritime Authority (NMA). KS-1150B Fartøysertifikat: Obligatorisk Kontrollskjema for Fiske- og Fangstfartøy; Norwegian Maritime Authority: Haugesund, Norway, 2016; Available online: https://www.sdir.no/siteassets/skjema/ks-1150b-feb25-fsf-fartssertifikat-for-fiske--og-fangstfartoy---obligatorisk.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Norwegian)

- Norwegian Maritime Authority (NMA). Sikkerhetsstyring på Mindre Fartøy; Norwegian Maritime Authority: Haugesund, Norway, 2017. Available online: https://www.sdir.no/contentassets/68b81e51e5864022b0fab7b88b39dc74/sikkerhetsstyring_pa_mindre_fartoy_2022.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Norwegian).

- Stormo, G. Sikkerhetsstyringssystem for Verneverdige Fartøy (<500 bt og <100 passasjerer): Mal Med Veiledning; Norsk Forening for Fartøyvern: Oslo, Norway, 2011. Available online: https://norsk-fartoyvern.no/wp-content/uploads/Mal-Sikkerhetsstyringssystem.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Norwegian).

- Danish Maritime Authority (DMA). Guidelines for Drawing up Safety Instructions; Danish Maritime Authority: Korsør, Denmark, 2020. Available online: https://www.dma.dk/Media/637725841125250325/Retningslinjer%20for%20udarbejdelse%20af%20sikkerhedsinstruks-uk.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Danish Maritime Authority (DMA). Safety Instructions for Voyages with Small Vessels; Danish Maritime Authority: Korsør, Denmark, 2012. Available online: https://www.dma.dk/Media/637725841464950940/Sikkerhedsinstruks-uk.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Danish Maritime Authority (DMA). Guidelines for Checklist for Fishing Vessels Below 15 Metres; Danish Maritime Authority: Korsør, Denmark, 2016. Available online: https://www.dma.dk/Media/637720465993597261/Guidelines%20for%20checklist%20for%20fishing%20vessels%20below%2015%20metres.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Danish Maritime Authority (DMA). Technical Regulation No. 8 of 15 July 2004 on the Conduction of Surveys and Internal Inspections; Danish Maritime Authority: Korsør, Denmark, 2004. Available online: https://www.dma.dk/Media/637720427964213895/Technical%20regulation%20on%20the%20conduction%20of%20surveys%20and%20internal%20inspections.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Fiskeriets Arbejdsmiljøråd (FA). Tjekliste før afgang fra havn [Checklist for Annual Self-Monitoring of Fishing Vessels Below 15 Metres]; Fiskeriets Arbejdsmiljøråd: Esbjerg, Denmark, 2015. Available online: https://f-a.dk/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Tjeklister.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Danish).

- Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA). MGN 636 (M): Merchant Shipping and Fishing Vessels (Health and Safety at Work) Regulations 1997; Maritime and Coastguard Agency: Southampton, UK, 2020. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5f05ac68d3bf7f2bf0f9b5b6/MGN_636_-_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA). Fishermen’s Safety Guide: A Guide to Safe Working Practices and Emergency Procedures for Fishermen, Amendment 1; Maritime and Coastguard Agency: Southampton, UK, 2020. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5eac030986650c435a68dd0b/Fishermans_safety_guide_2020_amendment_1.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA). The Code of Practice for the Safety of Fishing Vessels of Less than 15 Metres Length Overall (Draft Small Fishing Vessel Code); Maritime and Coastguard Agency: Southampton, UK, 2016. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a8156c440f0b62305b8e6a7/Draft_Small_Fishing_Vessel_Code.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA). Collection: Fishing Safety Guides and Publications; Maritime and Coastguard Agency: Southampton, UK, 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/fishing-safety-guides-and-publications (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Department of Enterprise; Trade and Employment (DETE). Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act 2005 (No. 10 of 2005); The Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2005. Available online: https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2005/act/10/enacted/en/pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Department of Transport (DT). Merchant Shipping (Safety of Fishing Vessels) (15–24 Metres) Regulations 2007 (S.I. No. 640 of 2007); The Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2007. Available online: https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2007/si/640/made/en/pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Health and Safety Authority (HSA). Fishing Vessel Safety Statement; Health and Safety Authority: Dublin, Ireland, 2014. Available online: https://www.hsa.ie/eng/publications_and_forms/publications/fishing/fishing_vessel_safety_statement.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF). Guidelines for Risk Assessment of Fishing Vessels; Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries: Sejong-si, Republic of Korea, 2024. Available online: https://www.mof.go.kr/doc/ko/selectDoc.do?docSeq=62945&menuSeq=885&bbsSeq=35 (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Korean).

- Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF). Standards for the Safety, Health, and Accident Prevention of Fishing Vessel Crews; Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries: Sejong-si, Republic of Korea, 2024. Available online: https://www.mof.go.kr/doc/ko/selectDoc.do?docSeq=62934&menuSeq=885&bbsSeq=35 (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Korean).

- Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF). Standard Manual for Occupational Safety and Health: Coastal Gillnet Fishery; Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries: Sejong-si, Republic of Korea, 2021. Available online: https://www.suhyup.co.kr/synap/skin/doc.html?fn=temp_1717569016865100&rs=/synap/result/bbs/311 (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Korean).

- Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF). Fisher’s Voluntary Safety Rules for Fishing Operations; Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries: Sejong-si, Republic of Korea, 2021. Available online: https://www.suhyup.co.kr/sites/suhyup/down/safetyEducation.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Korean).

- Rasmussen, J. Skills, Rules, and Knowledge; Signals, Signs, and Symbols, and Other Distinctions in Human Performance Models. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybern. 2012, SMC-13, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, J. Human Error; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; ISBN 0521314194. [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo, M.; Murino, T. The System Dynamics in the Human Reliability Analysis through Cognitive Reliability and Error Analysis Method: A Case Study of an LPG Company. Int. Rev. Civ. Eng. 2021, 12, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveson, N. Engineering a Safer World: Systems Thinking Applied to Safety; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; ISSN 0262533693. [Google Scholar]

- Leveson, N.; Thomas, J. STPA Handbook; Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT): Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.flighttestsafety.org/images/STPA_Handbook.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

| Sjekkliste Sikkerhets Familiarisering (Safety Familiarization Checklist) | ||

|---|---|---|

| M = Muntlig (Oral Instruction), P = Praktisk (Practical Exercise) | ||

| Norsk (Original) | English (Translation) | |

| Emne | Subject | |

| Hovedemner | Main Topics | |

| M/P | Gjennomgang av perm for sikker-hetsstyringssystem. | Review of the safety management system manual |

| M/P | Skipets brann og sikkerhetsplan. | Ship’s fire and safety plan |

| M/P | Alarmsignal og alarminstruks + oppgaver. | Alarm signals, alarm instructions, and assigned duties |

| M/P | Rederiets beredskapsplan. | Company’s emergency preparedness plan |

| Rednings og sikkerhetsutstyr, plassering og bruk | Rescue and safety equipment, location and use | |

| P | Intercomanlegg | Intercom system |

| P | Utganger/nødutganger | Exits/emergency exits |

| P | Redningsvester | Life jackets |

| P | Overlevingsdrakter for mannskap | Immersion suits for crew |

| P | Livbøyer, m/line, lys, røyk | Lifebuoys with lines, light, and smoke |

| P | Nød og evakueringsleider | Emergency and evacuation ladders |

| M/P | Nødbluss og fallskjermlys | Distress flares and parachute rockets |

| M/P | Nødpeilesender, fri-flyt og SART | Emergency beacons (EPIRB, free-float, and SART) |

| M/P | Førstehjelpskrin, båre | First-aid kit and stretcher |

| P | Redningsflåter, utsetting og utløsning | Liferafts, launching and release procedures |

| P | MOB-båt, utstyr og utsetting | Man-overboard (MOB) boat, equipment, and launching |

| P | Gjennomgått båtmanevør/redningsøvelse | Boat maneuver and rescue drill completed |

| Brannslukningsutstyr, plassering/bruk | Firefighting equipment, location/use | |

| P | Brannmeldere, varme og røykdetektorer | Fire alarms, heat, and smoke detectors |

| M/P | Brannalarmsentral | Fire alarm control panel |

| P | Brannslukningsapparater | Fire extinguishers |

| P | Brannposter m/slanger | Fire hydrants with hoses |

| P | Brannøkser | Fire axes |

| P | Røykdykkerutstyr | Smoke-diving (firefighting) equipment |

| P | Start av brannpumper | Starting the fire pump |

| P | Start av nødbrennumpumpe | Starting the emergency fire pump |

| P | Nødstopbrytere for vifter | Emergency stop switches for fans |

| P | Stenging av luftspjeld/ventilasjon | Closing air dampers/ventilation systems |

| P | Plassering og utløsning av Inergen/CO2 | Location and activation of Inergen/CO2 system |

| Nødprosedyrer/alarminstruks | Emergency procedures/alarm instructions | |

| M/P | Manuell nødstopp motorer | Manual emergencies stop for engines |

| P | Hurtiglukker for brennolje | Quick-closing valve for fuel oil |

| M/P | Lensearrangement og nødlensing | Bilge system and emergency bilge pumping |

| M/P | Nødstyring | Emergency steering |

| M/P | Brannslukking, prosedyrer | Firefighting procedures |

| M/P | Mann-over-bord prosedyre | Man-overboard procedure |

| M/P | Evakuering. Fordeling til flåter og entring av disse | Evacuation, allocation to life rafts and boarding procedures |

| M | Skipets oljevernberedskapsplan | Ship’s oil pollution emergency plan |

| Driftsrutiner | Operational routines | |

| M | Ordinære driftsrutiner | Ordinary operating routines |

| M/P | Gjennomgang av risikovurderinger og avviksmeldinger | Review of risk assessments and deviation reports |

| M | Rutiner ved liggetid i havn | Procedures during port stay |

| M | Om bord og ilandstigning | Embarkation and disembarkation routines |

| M/P | Vedlikeholdsrutiner | Maintenance routines |

| Tjekliste før Afgang fra Havn (Checklist Before Departure from Port) | |

|---|---|

| Danish (Original) | English (Translation) |

| Områder der bør Efterses | Areas to be Inspected |

| Redningsmidler | Life-Saving Appliances |

| Er redningsmidler på plads og i orden? | Are life-saving appliances in place and in good order? |

| Er foranstaltningerne ved overbordfald i orden? | Are the arrangements for man overboard situations in order? |

| Styrehus | Wheelhouse/Bridge |

| Er lydsignal-apparatet i orden? | Is the sound signalling device in working order? |

| Virker alle lanterner? | Are all navigation lights functioning properly? |

| Dæk | Deck |

| Er lænseportene frie? | Are the freeing ports clear? |

| Er styrestangsarrangementet i orden? | Is the steering-rod arrangement in order? |

| Er der tilstrækkeligt med brændstof om bord? | Is there sufficient fuel on board? |

| Er vejrmeldingen for påtænkt fiskeri kontrolleret? | Has the weather forecast for the intended fishing operation been checked? |

| Vil fartøjet under hele den påtænkte rejse have tilstrækkelig stabilitet og fribord? | Will the vessel have sufficient stability and freeboard for the entire intended voyage? |

| Er luger og dæksler lukkede og skalkede? | Are hatches and covers closed and properly secured? |

| Kan luger og døre sikres i åben tilstand? | Can hatches and doors be secured in the open position? |

| Er sikkerhedsanordninger på takkelblokke og bomme i orden? | Are safety devices on tackle blocks and booms in order? |

| Går betjeningshåndtag på spil/nettromler automatisk i neutralstilling? | Do the operating handles on winches or net drums automatically return to the neutral position? |

| Maskinrum/fremdrivningsanlæg | Engine room/Propulsion system |

| Er pumper og andre lænsemidler i orden? | Are the pumps and other bilge systems in working order? |

| Er vandstandsalarmerne i orden? | Are the water-level alarms functioning properly? |

| Er slange- og søforbindelser uden lækage? | Are the hose and sea connections free from leaks? |

| Er brandvisnings- og brandslukningsanlægget i orden? | Are fire detection and fire-extinguishing systems in working order? |

| Item | Remarks/Compliance | Expiry/Service Date |

|---|---|---|

| Lifejackets—1 per person + 2 spare | ||

| Liferaft(s)—sufficient capacity for all persons on board | ||

| 2 Lifebuoys (with 18 m buoyant line attached) or 1 Lifebuoy (with 18 m buoyant line) + 1 Buoyant Rescue Quoit | ||

| 3 Parachute Flares | ||

| 2 Hand-held Flares | ||

| 1 Smoke Signal (buoyant or handheld) | ||

| Gas Detector | ||

| 1 Fire Blanket (light duty) in galley or cooking area (if applicable) | ||

| Fire Detectors | ||

| 1 Fire Pump + Hose, 2 Multi-purpose Fire Extinguishers (ratings 5A/34B and 13A/113B), 1 Fire Bucket + Lanyard, 1 Fixed Fire Extinguishing System) | ||

| 1 Multi-purpose Fire Extinguisher for oil fires (rating 13A/113B) | ||

| Satellite EPIRB (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon) | ||

| VHF Radio—DSC fixed and hand-held | ||

| Bilge Pump | ||

| Bilge Level Alarm | ||

| Approved Navigation Lights & Sound Signals | ||

| Anchor and Cable/Warp | ||

| Compass | ||

| Waterproof Torch | ||

| Medical Kit | ||

| Radar Reflector | ||

| CO Alarm for every enclosed space with a fired cooking or heating appliance |

| Category | Checklist Items |

|---|---|

| First Aid | - Trained first aiders and a first aid kit as approved must be carried on board the vessel. - The Trained First Aider is: ________ |

| Communications | - The communications equipment on board consists of the following: ________- When not in use it will be left on this emergency channel: ________ |

| Lighting | - Are all working areas above, on and below deck properly lit? - Are emergency lighting facilities available?—Are enough spare bulbs on board? - Is the boarding area properly lit? - Are reflective bands worn on deck? - Is the searchlight working? |

| Fatigue | - Prolonged periods without sleep impair judgement, concentration and the ability to communicate. - If you find it difficult to remain alert on watch, notify the skipper immediately. - Minimum rest periods should be discussed and agreed before going to sea. |

| Pre-Steaming Check List | - Are adequate supplies (for example diesel, food, water, lube oil etc.) on board for expected trip duration? - Does someone ashore know who is on board and your expected return date and time? - Are adequate spare parts (for example hydraulic, electrical, mechanical etc.) on board for the trip? - Have emergency muster procedures been practiced?—Are all relevant marine notices and charts on board? - Is all ancillary equipment (e.g., generators and auxiliaries etc.) in good order? - Do you understand all emergency signals on board and know how to respond to them? |

| Anchoring | - Do you know the anchoring arrangements on board? - Do you know the procedure for laying it up? - How quickly can the anchor be shot in an emergency? - Remember to stand clear of the anchor when it is being deployed or retrieved. |

| Drink and Drugs | - What arrangements have been made for boarding?—Is the man on watch fit? - Is anyone on board taking non-prescribed drugs while at sea? - Is anyone on board prescribed medication? - If the answer to any of these questions is yes, has the skipper been advised? |

| Ventilation | - Carbon dioxide asphyxiation can result from inadequate ventilation of galleys and cabins. - Carbon monoxide poisoning can result from incomplete combustion of gas/paraffin/diesel heaters. - Engine exhaust fumes are extremely toxic. - Liquid Petroleum Gas (LPG) leaks can kill. The gas is heavier than air and sinks to cabin floor/bilge levels and can explode or ignite. - Methane and other gases produced by rotting fish can kill. - If you feel dizzy or awake with headaches, check heaters, cookers and ventilation fans and ducts, report symptoms to the skipper. If necessary, evacuate cabins etc. |

| Emergency Stops | - Does everyone on deck know the emergency stop signals? - Who controls machinery emergency stops, such as winches, haulers etc.? - Are emergency reverse signals and procedures clearly understood? |

| Berthing | - Are all signaling procedures clearly understood? - Remember to stand clear of ropes under strain. - Avoid riding turns on drum ends.—Beware of ropes chafing at the pier edge. - Make sure that deck hose is not underwater when the pump is shutdown. - Take care not to get crushed between the side of the boat—watch fingers, hands etc. - Are rope/wire splices/bridles sound and are all ropes/wires/bridles in good condition? |

| Painting and Dry Docking | - Take great care when using ladders to climb masts or onto boats. - Ensure that electrical wires from ashore are rigged. |

| Accident Type | Category | SRK Model | Ratio (%) | SLMV Model | Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collision | Give-way vessel | Skill-based | 68 | Slip | 2 |

| Rule-based | 18 | Lapse | 63 | ||

| Knowledge-based | 13 | Mistake | 17 | ||

| Others/Not human error | 1 | Violation | 17 | ||

| Others/Not human error | 1 | ||||

| Stand-on vessel | Skill-based | 47 | Slip | 0 | |

| Rule-based | 37 | Lapse | 48 | ||

| Knowledge-based | 6 | Mistake | 37 | ||

| Others/Not human error | 10 | Violation | 5 | ||

| Others/Not human error | 10 | ||||

| Occupational Accident | Skill-based | 40 | Slip | 33 | |

| Rule-based | 18 | Lapse | 15 | ||

| Knowledge-based | 21 | Mistake | 28 | ||

| Others/Not human error | 21 | Violation | 3 | ||

| Others/Not human error | 21 | ||||

| Risk Rank | Accident Type | Generic Failure Type | CFP (Worst) | CFP (Neutral) | CFP (Best) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Falling inside the boat | Action of the wrong type | 1.5927 | 0.2832 | 0.0949 |

| 2 | Slipping on the deck | Wrong identification | 0.4170 | 0.0741 | 0.0248 |

| 3 | Getting caught in equipment | Action at the wrong time | 0.1787 | 0.0318 | 0.0106 |

| 4 | Collision while sailing | Observation not made | 0.1397 | 0.0248 | 0.0083 |

| 5 | Getting caught in fishing nets | Action on the wrong object | 0.0298 | 0.0053 | 0.0018 |

| No | Loss |

|---|---|

| L1 | Loss of human life/injury |

| L2 | Asset damage (ship, fishing gear, etc.) |

| L3 | Loss of missions (fishing) |

| No | Hazard |

| H1 | Navigation-related hazards |

| H1.1 | Collision/contact [L1, L2, L3] |

| H1.2 | Grounding [L1, L2, L3] |

| H1.3 | Capsizing [L1, L2, L3] |

| H2 | Technical system-related hazards |

| H2.1 | Fire/explosion [L1, L2, L3] |

| H2.2 | Mechanical system failure/damage [L2, L3] |

| H3 | Fishing operation-related hazards |

| H3.1 | Fishing operation is not started/stopped when necessary [L1, L3] |

| H3.2 | Not able to operate fishing on time [L3] |

| Korea Coast Guard | ||

|---|---|---|

| Responsibility | Process Model | Feedback |

| Provide sailing permits to captain | Vessel is ready to sail Weather condition is good enough for sailing | Vessel status Crew information |

| Captain | ||

| Responsibility | Process Model | Feedback |

| Control speed of vessel via propulsion system | Need to control speed to prevent collision | Speed of vessel Location of other vessel |

| Control heading of vessel via steering system | Need to control heading to prevent collision | Heading of vessel Location of other vessel |

| Order start/stop fishing operation to fishing crew | Fishing operation is ready Need to stop fishing operation for safety | Fishing operation status Navigation status |

| Give way for stand-on vessel | Vessel is heading to stand-on vessel | Speed of vessel Heading of vessel Location of other vessel |

| Ask give way to give-way vessel | Other vessel is heading to fishing vessel | Speed of other vessel Heading of other vessel Location of other vessel |

| Fishing Crew | ||

| Responsibility | Process Model | Feedback |

| Start/stop fishing operation | Fishing operation is ready Need to stop fishing operation for safety Start/stop order from captain | Fishing gear status |

| Stand-On Vessel | ||

| Responsibility | Process Model | Feedback |

| Ask give way to fishing vessel | Fishing vessel is approaching to other vessel | Speed of vessel Heading of vessel Location of other vessel |

| Give-Way Vessel | ||

| Responsibility | Process Model | Feedback |

| Give way for fishing vessel | Other vessel is approaching to fishing vessel | Speed of other vessel Heading of other vessel Location of other vessel |

| No. | Controller | UCA (Summary) | Representative Loss Scenario (Root-Cause Type) | Linked Hazard | Potential Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Korea Coast Guard | Does not issue sailing permit although vessel is ready and weather is safe | Real-time readiness/weather feedback is missing, so the permit is delayed, and the fishing window is lost (Inadequate Feedback/Communication Issues) | H3.2 | L3 |

| 2 | Captain | Delays speed command required for collision avoidance | Collision risk rises due to delayed hazard perception or sensor lag, leading to late deceleration (Delayed Feedback/Human Error) | H1.1, H1.2 | L1, L2, L3 |

| 3 | Captain | Starts fishing operation too early | System mislabels readiness and activates gear before safety is secured (Faulty System Trigger/Incorrect Process Model) | H3.1 | L1, L3 |

| 4 | Fishing Crew | Fails to relay/execute emergency stop when unsafe | Communication failure delays stopping of gear in a hazardous condition (Miscommunication/System Failure) | H3.1 | L1, L3 |

| 5 | Give-Way Vessel | Fails to give way to the fishing vessel | Misjudged target motion or sensor fault delays the give-way action, increasing collision risk (Incorrect Process Model/Sensor Failure) | H1.1 | L1, L2 |

| Pre-Operation Checklist | Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Checklist Item | O/X | |

| Work-related | Have you checked weather and navigational information before departure? | Korean regulation; EU checklist; STPA | |

| Have you confirmed that the vessel is not overloaded or carrying excess crew? | EU checklist | ||

| Have you checked crew fatigue, alcohol use, and overall health condition? | EU checklist; CREAM | ||

| Have you reviewed and shared the operational plan with all crew members? | EU checklist; CREAM | ||

| Are all crew members wearing required protective equipment (life jackets, boots, gloves, etc.)? | Korean regulation; EU checklist | ||

| Are night or early-morning lighting systems sufficient and operating properly? | Korean regulation | ||

| Equipment-related | Are the engine, propulsion, and fuel-supply systems operating normally (no leaks, overheating, or malfunctions)? | Korean regulation; EU checklist; SRK/SLMV | |

| Are navigation instruments functioning properly? | EU checklist; SRK/SLMV; STPA | ||

| Are fire extinguishers, lifebuoys, and lifejackets in normal condition? | EU checklist; STPA | ||

| Are fishing gears properly arranged and safely secured (nets, winches, ropes, etc.)? | EU checklist; SRK/SLMV | ||

| Post-Operation Checklist | Source | ||

| Category | Checklist Item | O/X | |

| Work-related | Have you reported the end of operation and return to port? | Korean regulation; SRK/SLMV | |

| Have you checked the crew’s health condition after operation? | EU checklist; SRK/SLMV; CREAM | ||

| Have you completed the logbook and accident report? | Korean regulation; SRK/SLMV; STPA | ||

| Equipment-related | Are catches properly arranged and stowed? | Korean regulation; EU checklist; SRK/SLMV | |

| Have you checked whether used equipment or fishing gears are free from damage? | Korean regulation; EU checklist; STPA | ||

| After hauling, are nets and ropes safely organized and stored? | Korean regulation; EU checklist | ||

| Have you removed water and oil residues and cleaned the deck? | EU checklist; CREAM | ||

| Periodic Inspection Checklist | Source | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inspection Item | Recommended Frequency | Validity/Record | Confirmation Date | Risk Level | |

| Work-Related | |||||

| Crew emergency training (firefighting, rescue, flooding control, etc.) | At least once a year | Keep records for 5 years | Inspector’s name | H, L, M | Korean regulation; CREAM |

| Accident-case sharing and safety-training records | At least once a year | Keep records for 5 years | Inspector’s name | Enter below ↓ | Korean regulation; EU checklist; STPA |

| New-crew safety orientation | Upon new embarkation | Mandatory before boarding | Inspector’s name | EU checklist; CREAM | |

| Fish-hold and catch-storage condition (hygiene, drainage, cooling) | - | Every 6 months recommended | 0000-00-00 | EU checklist | |

| Winch/hauler emergency stop | - | - | 0000-00-00 | Korean regulation; EU checklist; | |

| Risk assessment | At least once a year | Keep records for 3 years | 0000-00-00 | Korean regulation; EU checklist; | |

| Equipment-related | Source | ||||

| Deck condition (deck, structures, fishing gear, ropes, etc.) | At least once a month | - | 0000-00-00 | Korean regulation; EU checklist; | |

| Anti-slip condition/guardrail damage | At least once a month | - | 0000-00-00 | EU checklist; SRK/SLMV; CREAM | |

| Safe access route secured | At least once a month | - | 0000-00-00 | EU checklist | |

| Engine-room condition (engine, lubrication, fuel, electrical systems) | At least once a month | Include in periodic inspection | 0000-00-00 | Korean regulation; SRK/SLMV | |

| Engine-room ventilation/exhaust safety | At least every 6 months | - | 0000-00-00 | EU checklist | |

| Hatch and watertight door condition | Quarterly recommended | - | 0000-00-00 | EU checklist | |

| Propulsion system (propeller, shaft, steering gear) inspection | Every 4 years recommended | Include in periodic inspection | 0000-00-00 | Korean regulation; EU checklist; CREAM | |

| Navigation & communication equipment (GPS, radar, AIS, VHF, etc.) | Quarterly recommended | Include in periodic inspection | 0000-00-00 | Korean regulation; EU checklist | |

| Navigation lights and signal devices | Quarterly recommended | - | 0000-00-00 | EU checklist; STPA | |

| Electrical equipment (charging, wiring, circuit breakers) | Quarterly recommended | Include in periodic inspection | 0000-00-00 | EU checklist; SRK/SLMV | |

| Emergency power and battery condition | Quarterly recommended | - | 0000-00-00 | Korean regulation; EU checklist | |

| Safety & supplies | Source | ||||

| Fire extinguisher (two portable units < 5 t/10-year replacement) | Monthly (visual) | Mandatory monthly check | 0000-00-00 | Korean regulation; EU checklist | |

| Lifebuoys (for vessels < 20 mL OA, two units) | Monthly (visual) | Mandatory monthly check | 0000-00-00 | Korean regulation; EU checklist | |

| Lifejackets | Monthly (visual) | Mandatory monthly check | 0000-00-00 | Korean regulation; EU checklist | |

| First-aid kit | Quarterly | Replace expired items | 0000-00-00 | EU checklist; SRK/SLMV | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, S.; Kim, H.; Kwon, S. Development of a Korean-Specific Safety Checklist for Fishing Vessel Based on European Standards and Human and System Analysis Methods (SRK/SLMV, CREAM, STPA). Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010086

Lee S, Kim H, Kwon S. Development of a Korean-Specific Safety Checklist for Fishing Vessel Based on European Standards and Human and System Analysis Methods (SRK/SLMV, CREAM, STPA). Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010086

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Soonhyun, Hyungju Kim, and Sooyeon Kwon. 2026. "Development of a Korean-Specific Safety Checklist for Fishing Vessel Based on European Standards and Human and System Analysis Methods (SRK/SLMV, CREAM, STPA)" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010086

APA StyleLee, S., Kim, H., & Kwon, S. (2026). Development of a Korean-Specific Safety Checklist for Fishing Vessel Based on European Standards and Human and System Analysis Methods (SRK/SLMV, CREAM, STPA). Applied Sciences, 16(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010086