Effectiveness of Wearable Devices for Posture Correction: A Systematic Review of Evidence from Randomized and Quasi-Experimental Studies

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Intervention

2.1.3. Comparison

2.1.4. Outcomes

2.1.5. Types of Studies

2.2. Search Strategy

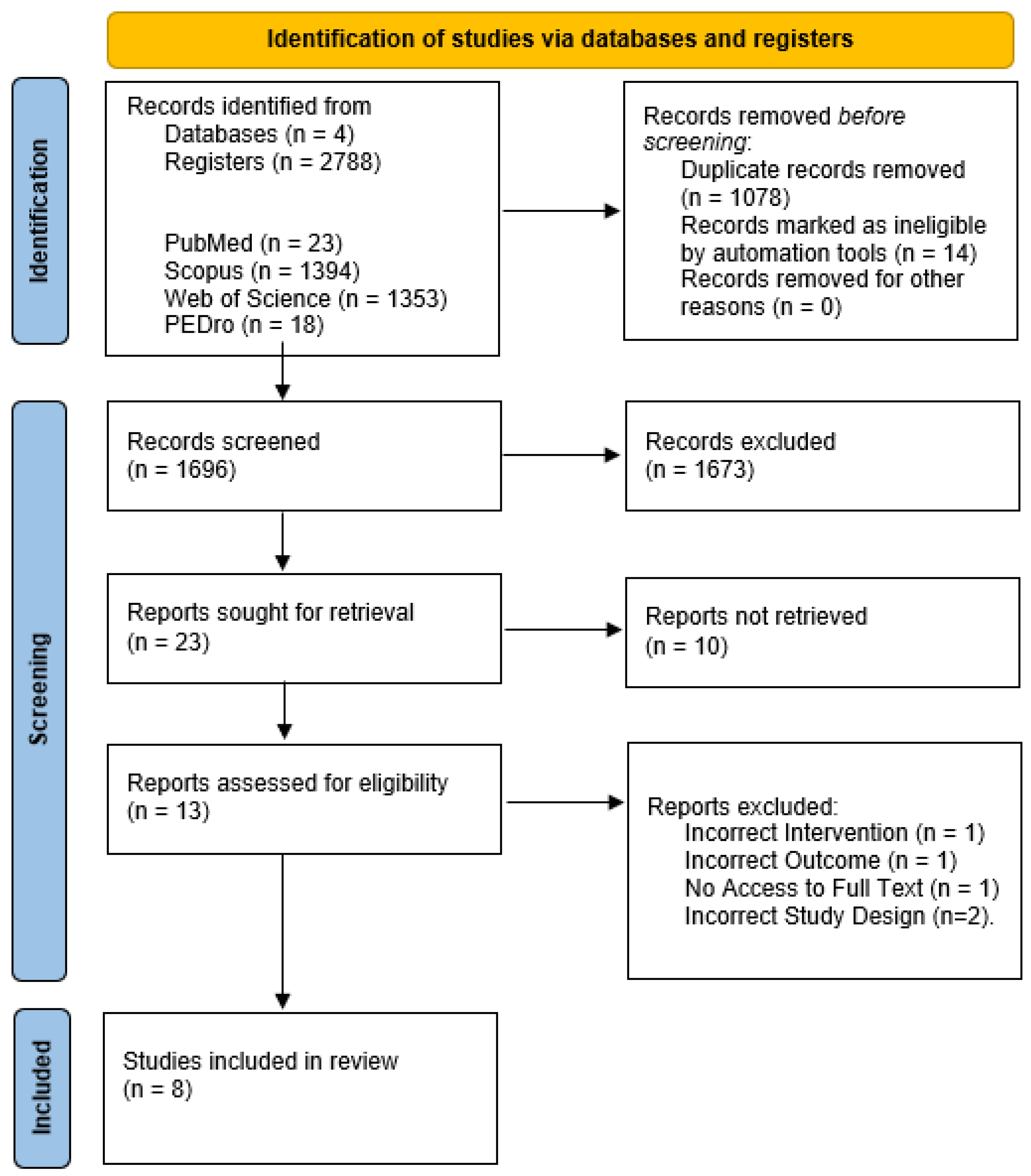

2.3. Study Identification and Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias and Methodological Quality

2.6. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Experimental Interventions

3.2.1. Types of Wearable Devices and Feedback Provided

3.2.2. Characteristics of Interventions

3.2.3. Outcome Measures

3.2.4. Effectiveness of Wearable Device Use

On the Cervical Spine

On the Thoracic Spine

On the Lumbar Spine

On Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis (AIS) and Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI)

3.3. Overall Synthesis of Results

3.4. Risk of Bias Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Subgroup: Cervical Spine Intervention

4.2. Subgroup: Thoracic Spine Intervention

4.3. Subgroup: Lumbar Spine Intervention

4.4. Subgroup: Intervention in Individuals with Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis (AIS) and Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI)

4.5. Limitations

4.6. Clinical Implications and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Database | Search Date | Search Strategy | Filters (Study Type, Year of Publication, Language) | Results |

| PubMed | 25 September 2025 | P AND I: ((wearable*[Title/Abstract]) OR (“smart vest”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“smart garment”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“smart clothing”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“inertial sensors”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“body worn devices”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“wearable systems”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“smart sensor*”[Title/Abstract]) OR (imus[Title/Abstract]) OR (“inertial measurement units”[Title/Abstract])) AND ((posture[Title/Abstract]) OR (“postural assessment”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“body posture”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“posture monitoring”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“postural correction”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“postural alignment”[Title/Abstract]) OR (kyphosis[Title/Abstract]) OR (lordosis[Title/Abstract]) OR (hyperkyphosis[Title/Abstract]) OR (hyperlordosis[Title/Abstract]) OR (scoliosis[Title/Abstract])) | 2012–2025 RCT; CT; | 23 |

| Scopus | 26 September 2025 | P AND I: TITLE-ABS-KEY ((wearable*) OR (“smart vest”) OR (“smart garment”) OR (“smart clothing”) OR (“inertial sensors”) OR (“body worn devices”) OR (“wearable systems”) OR (“smart sensor*”) OR (imus) OR (“inertial measurement units”)) AND ((posture) OR (“postural assessment”) OR (“body posture”) OR (“posture monitoring”) OR (“postural correction”) OR (“postural alignment”) OR (kyphosis) OR (lordosis) OR (hyperkyphosis) OR (hyperlordosis) OR (scoliosis)) | 2012–2026; Article; English; (Subject Area); | 1394 |

| Web of Science | 26 September 2025 | P AND I: I: (Topic) (wearable* OR “smart vest” OR “smart garment” OR “inertial measurement units” OR “smart clothing” OR “inertial sensors” OR “body worn devices” OR “wearable systems” OR “pressure sensor” OR “smart sensor” OR IMUs) P: (Topic) (posture OR “postural assessment” OR “body posture” OR “posture monitoring” OR “postural correction” OR “postural alignment” OR kyphosis OR lordosis OR hyperkyphosis OR hyperlordosis OR scoliosis) | 1 January 2012–26 September 2025 Article; English; (WoS Categories); | 1353 |

| PEDro | 26 September 2025 | Wearable AND Posture | Clinical Trial | 2 |

| PEDro | 26 September 2025 | Inertial Sensors | Clinical Trial | 8 |

| PEDro | 26 September 2025 | IMUs | Clinical Trial | 1 |

| PEDro | 26 September 2025 | Inertial Measurement Units | Clinical Trial | 6 |

| PEDro | 26 September 2025 | Smart Sensors | Clinical Trial | 1 |

References

- Maekawa, M. Effects of Postural Interventions on Physical and Psychological Aspects of Children in Terms of Secondary Sexual Characteristics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susilowati, I.H.; Kurniawidjaja, L.M.; Nugraha, S.; Nasri, S.M.; Pujiriani, I.; Hasiholan, B.P. The prevalence of bad posture and musculoskeletal symptoms originating from the use of gadgets as an impact of the work from home program of the university community. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, A.; Frome, D.K.; Gibly, R.F.; Larson, J.E.; Patel, N.M.; Sarwark, J.F. IS (Idiopathic Scoliosis) etiology: Multifactorial genetic research continues. A systematic review 1950 to 2017. J. Orthop. 2020, 21, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Ho, R.L.M.; Coombes, S.A. The effect of chronic low back pain on postural control during quiet standing: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsali, M.; Sheikhhoseini, R.; Sayyadi, P.; Hides, J.A.; Dadfar, M.; Piri, H. Association between physical activity and body posture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.; Sagar, M.; Sollers, J.; Consedine, N.; Broadbent, E. Do slumped and upright postures affect stress responses? A randomized trial. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkes, C.; Kydd, R.; Sagar, M.; Broadbent, E. Upright posture improves affect and fatigue in people with depressive symptoms. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2017, 54, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, S.H.; Zhang, Y.H.; Yang, Q.H.; Wang, Y.C.; Fang, Y.; Wang, X.Q. Spinal posture assessment and low back pain. EFORT Open Rev. 2023, 8, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceballos-Laita, L.; Carrasco-Uribarren, A.; Cabanillas-Barea, S.; Pérez-Guillén, S.; Pardospardos-Aguilella, P.; Del Barrio, S.J. The effectiveness of Schroth method in Cobb angle, quality of life and trunk rotation angle in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ed. Minerva Med. 2023, 59, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Lu, X.; Yan, B.; Huang, Y. Prevalence of Incorrect Posture among Children and Adolescents: Finding from a Large Population-Based Study in China. iScience 2020, 23, 101043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratěnová, J.; ŽEjglicová, K.; Malý, M.; Filipová, V. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Poor Posture in School Children in the Czech Republic. J. Sch. Health 2007, 77, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokrywka, J.; Fugiel, J.; Posłuszny, P. Czȩstość wad postawy ciała u dzieci z Zagłȩbia Miedziowego. Fizjoterapia 2011, 19, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhang, J.; Xie, Y.; Gao, F.; Xu, S.; Wu, X.; Ye, Z. Wearable health devices in health care: Narrative systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e18907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, R.; May, A.M.; van Overmeeren, E.J.; Simons, M.; Monninkhof, E.M. The Effect of Physical Activity Interventions Comprising Wearables and Smartphone Applications on Physical Activity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2018, 4, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Master, H.; Bley, J.A.; Coronado, R.A.; Robinette, P.E.; White, D.K.; Pennings, J.S.; Archer, K.R. Effects of physical activity interventions using wearables to improve objectively-measured and patient-reported outcomes in adults following orthopaedic surgical procedures: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhini, J.; Marzaro, C.; Bargeri, S.; Palese, A.; Dell’Isola, A.; Turolla, A.; Rossettini, G. Wearable Devices to Improve Physical Activity and Reduce Sedentary Behaviour: An Umbrella Review. Sports Med.-Open 2024, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueira, V.; Silva, S.; Costa, I.; Campos, B.; Salgado, J.; Pinho, L.; Pinho, F. Wearables for Monitoring and Postural Feedback in the Work Context: A Scoping Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, L.; Maharaj, M.M.; Mobbs, R.J. The role of wearables in spinal posture analysis: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.; James, C.; Edwards, S.; Skinner, G.; Young, J.L.; Snodgrass, S.J. Evidence for the effectiveness of feedback from wearable inertial sensors during work-related activities: A scoping review. Sensors 2021, 21, 6377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra-López, M.E. M the Standard Posture Is a Myth: A Scoping Review. J. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 56, jrm41899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 373, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, S.M.N.; Gopalai, A. Intelligent vibrotactile biofeedback system for real-time postural correction on perturbed surfaces. In Proceedings of the 2012 12th International Conference on Intelligent Systems Design and Applications (ISDA), Kochi, India, 27–29 November 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; McKenzie, J.E.; Sowden, A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Brennan, S.E.; Ellis, S.; Thomson, H. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. BMJ 2020, 368, 16890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.; Rabunal, J.R.; Pazos, A.; Sotillo, A.R.; Ezquerra, N. Wearable Postural Control System for Low Back Pain Therapy. IEEE Trans Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 4003510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiwara, Y.; Yabe, Y.; Yamada, H.; Watanabe, T.; Kanazawa, K.; Koide, M.; Itoi, E. Effects of a wearable type lumbosacral support for low back pain among hospital workers: A randomized controlled trial. J. Occup. Health 2017, 59, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storm, F.A.; Redaelli, D.F.; Biffi, E.; Reni, G.; Fraschini, P. Additive Manufacturing of Spinal Braces: Evaluation of Production Process and Postural Stability in Patients with Scoliosis. Materials 2022, 15, 6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.L.; Wang, P.S.; Ko, P.Y.; Huang, K.Y.; Tsai, Y.J. Immediate effects of real-time postural biofeedback on spinal posture, muscle activity, and perceived pain severity in adults with neck pain. Gait Posture 2019, 67, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, E.; Lam, G.C.; Hill, D.L.; Wong, M.S. Development of a smart garment to reduce kyphosis during daily living. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2012, 50, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, G.; Jung, I.Y. Real-Time Forward Head Posture Detection and Correction System Utilizing an Inertial Measurement Unit Sensor. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanathornwong, B.; Jalayondeja, W. Vibrotactile -Feedback Device for Postural Balance among Malocclusion Patients. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2020, 8, 2100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Kim, S.; Park, H.J.; Kim, S.; Shin, D. A Spine Assistive Robot with a Routed Twisted String Actuator and a Flat-Back Alleviation Mechanism for Lumbar-Degenerative Flat Back. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 27, 5185–5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Cui, Z.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Wang, Z. Global research on wearable technology applications in healthcare: A data-driven bibliometric analysis. Digit Health 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Study Design | Sample/Groups Characteristics | Experimental Intervention(s) | Control Intervention(s) | Outcome Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kuo et al. (2019) [27] Taiwan | Quasi-experimental study | - Region: Cervical Spine - n = 21 (F: n = 13; M: n = 18) - Age (yrs): 23.8 ± 3.5 | - Wearable: Inertial sensor with vibratory feedback - Duration: 1 h | Within-subject design (without wearable) | - Cervical, neck, and thoracic flexion angles - Electromyographic (EMG) activity of cervical erector spinae (ES) muscles - Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) | - Reduction in all flexion angles. - Reduction in muscle activity. - Increase in pain. |

| Thanathornwong & Jalayondeja (2020) [30] South Korea | Quasi-experimental study | - Region: Cervical Spine - n = 24 (F: n = 20; M: n = 4) - Age (yrs): 23.4 ± 2.9 - 3 groups (n = 8/8/8) Class I malocclusion Class II malocclusion Class III malocclusion | - Wearable: Triaxial accelerometer with vibratory feedback - Duration: 4 weeks, 6 h per day | Not applicable | - Cervical flexion angle - Center of pressure | - Reduction in the cervical flexion angle in Class II malocclusion. - Reduction in the center of pressure in Class II malocclusion. |

| Park & Jung (2024) [29] South Korea | Quasi-experimental study | - Region: Cervical Spine - n = 10 (M: n = 10) - Age (yrs): 23.8 ± 0.9 | - Wearable: Inertial sensor with visual and auditory feedback - Duration: 15 min | Within-subject design (without wearable) | - Craniovertebral angle (CVA) - Time spent in forward head posture (FHP) | - Increase in CVA. - Reduction in time spent in FHP. |

| Lou et al. (2012) [28] Canada | Quasi-experimental study (pre-post) | - Region: Thoracic Spine - n = 4 (M: n = 4) - Age (yrs): 28 ± 5 | - Wearable: Adjustable vest with two inertial sensors and vibratory feedback - Duration: 4 days, ~3 h per day | Within-subject design (without feedback) | - Thoracic kyphosis angle - Number of feedback signals - Device comfort | - Reduction in thoracic kyphosis angles. - Consistent number of feedback activations. - Ease of use and comfort during device wearing. |

| Hagiwara et al. (2017) [25] Japan | Randomized controlled trial (single-blinded) | - Region: Lumbar Spine - n = 107 Experimental Group: - n = 54 (F: n = 52; M: n = 2) - Age (yrs): 44.7 ± 10 Control Group: - n = 53 (F: n = 52; M: n = 1) - Age (yrs): 44.7 ± 9.7 | - Wearable: Lumbosacral support with tactile stimulation - Duration: 3 months (except during bathing and sleep) | Waitlist group (no wearable) | - Subjective musculoskeletal symptoms - Low back pain (VAS) - Somatosensory Amplification Scale (SSAS) - Lumbar range of motion (ROM) | - Subjective musculoskeletal symptoms: - Reduction in low back pain; - Reduction neck pain. - Reduction in SSAS. - Reduction in lumbar ROM. |

| Rodriguez et al. (2021) [24] Spain | Pilot Quasi-experimental study | - Region: Lumbar Spine - n = 5 - Age Range (yrs): 18 to 65 | - Wearable: Inertial sensors with vibratory feedback - Duration: 10–35 sessions over a 4-month period | Within-subject design (without feedback) | - Feedback activation rate - Low back pain - Quality of life/functionality | - Reduction in device activation rate over time. - Reduction in low back pain. - Increased in postural awareness and ease of self-correction. |

| Lee et al. (2022) [31] South Korea | Pilot Quasi-experimental study (Evaluation during activities) | - Region: Lumbar Spine - n = 5 (M: n = 5) - Age (yrs): 25.2 ± 2.6 | - Wearable: Hybrid lumbar exoskeleton (active + passive components) - Duration: Performance of three low-effort tasks: trunk flexion, deadlift, and walking | Within-subject design (without wearable) | - Erector spinae muscle activation - Lumbo-pelvic ratio | - Reduction in muscle activation. - Lumbo-pelvic ratio: - Increase in the active component; - Reduction in the full device. |

| Storm et al. (2022) [26] Italy | Pilot experimental study | - Condition: Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis or Osteogenesis Imperfecta - n = 10 (F: n = 8; M: n = 2) Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Group - n = 8 (F: n = 8) - Age (yrs): 12.8–17.3 Osteogenesis Imperfecta Group - n = 2 (M: n = 2) - Age (yrs): 6.9–8.5 | - Wearable: 3D-printed vest - Duration: 2 weeks, median 10 h per day | Within-subject design (no vest and conventional vest) | - Range medio-lateral (ML) and antero-posterior (AP) sway amplitude - RMS (ML and AP): root mean square displacement of the center of pressure - Sway path length: total path length of postural movement - Frequency dispersion (ML and AP): variability of sway frequency in both plane | - Reduction in range (ML and AP) - Reduction in RMS (ML and AP). - Reduction in sway path length. - Reduction in frequency dispersion (AP and ML). |

| Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Rodriguez et al., 2021 [24] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Thanathornwong & Jalayondeja, 2020 [30] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lee et al., 2022 [31] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Park & Jung, 2024 [29] | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Lou et al., 2012 [28] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Storm et al., 2022 [26] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kuo et al., 2019 [27] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| Hagiwara et al., 2017 [25] | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Caixeiro, D.; Cordeiro, T.; Constantino, L.; Carreira, J.; Mendes, R.; Silva, C.G.; Castro, M.A. Effectiveness of Wearable Devices for Posture Correction: A Systematic Review of Evidence from Randomized and Quasi-Experimental Studies. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010081

Caixeiro D, Cordeiro T, Constantino L, Carreira J, Mendes R, Silva CG, Castro MA. Effectiveness of Wearable Devices for Posture Correction: A Systematic Review of Evidence from Randomized and Quasi-Experimental Studies. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010081

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaixeiro, Diogo, Tomás Cordeiro, Leandro Constantino, João Carreira, Rui Mendes, Cândida G. Silva, and Maria António Castro. 2026. "Effectiveness of Wearable Devices for Posture Correction: A Systematic Review of Evidence from Randomized and Quasi-Experimental Studies" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010081

APA StyleCaixeiro, D., Cordeiro, T., Constantino, L., Carreira, J., Mendes, R., Silva, C. G., & Castro, M. A. (2026). Effectiveness of Wearable Devices for Posture Correction: A Systematic Review of Evidence from Randomized and Quasi-Experimental Studies. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010081