1. Introduction

The ongoing expansion of China’s infrastructure construction sector has resulted in a consistent and gradual increase in the demand for subgrade materials in the field of road engineering. However, the rapid depletion of natural aggregates, restrictive mining policies, and rising raw material prices have made the development of green and sustainable road base materials an urgent necessity [

1]. Concurrently, substantial quantities of industrial solid waste are annually produced by the steel, chemical, and power industries, encompassing steel slag, blast furnace slag, and flue-gas-desulfurization gypsum (FGDG). In the absence of appropriate utilisation, these materials not only occupy substantial land areas but also pose significant environmental risks, including heavy-metal migration and sulfate leaching [

2]. Preceding studies demonstrated that steel slag, blast furnace slag, and other solid waste materials have the capacity to manifest latent hydraulic or pozzolanic activity when exposed to alkaline conditions. This finding suggests that these materials could be utilised as a resource in the construction of road bases. Moreover, the utilisation of FGD gypsum, a significant by-product of coal-fired power plants, has been shown to mitigate the risks associated with stockpiling and to enhance hydration reactions with slag, thereby contributing to the formation of structural products such as C–S–H and AFt, which in turn improves the strength and durability of base materials [

3,

4,

5]. Consequently, the synergistic utilisation of multiple industrial solid wastes for the production of road base materials has emerged as a pivotal approach in achieving high-value solid-waste utilisation, pollution reduction, and low-carbon development in road engineering.

In the National Catalogue of Hazardous Wastes (2021), barium slag (BS) is categorised as a HW47 hazardous waste due to the presence of high concentrations of soluble Ba

2+, strong alkalinity, and corrosivity. The primary source of BS is the carbothermal reduction of barite (BaSO

4), a process that occurs during the manufacture of barium salts. The by-products frequently contain unreacted barite, BaS, BaO, and other components, with complex composition and high environmental risk. In conditions of rainfall or leaching, the stockpiling of BS has been demonstrated to result in the release of Ba

2+, thereby posing a considerable threat to the quality of groundwater [

6,

7,

8]. Conventional disposal methodologies—such as incineration, landfilling, or basic chemical stabilization—are characterised by elevated energy consumption, substantial financial expenditure, and the potential for secondary pollution hazards. Consequently, they are not conducive to large-scale or secure treatment [

9,

10].

Sulfate–barium precipitation technology has been demonstrated to be an effective approach for BS detoxification. Sulfate ions (SO

42−) have been observed to react rapidly with barium ions (Ba

2+) to form barium sulfate (BaSO

4), a mineral that exhibits extremely low solubility. This reaction has been shown to significantly reduce the mobility of barium, thereby ensuring long-term stability. Previous research has indicated that phosphogypsum, sodium sulfate, and industrial by-product FGD gypsum have the capacity to effectively mitigate Ba

2+ leaching [

11,

12]. In our previous research, FGD gypsum was utilised as a sulfate source to achieve efficient detoxification of BS, and an optimised BS/FGDG ratio successfully reduced Ba

2+ leaching below the regulatory limits for hazardous waste identification while producing harmless treated barium slag (HTBS) with measurable strength. Further microstructural analyses indicated that the synergistic formation of BaSO

4, C-S-H gels, and AFt contributed collectively to structural densification and strength gain [

9].

The concept of green construction materials has driven the research interest in multi-solid-waste co-activation. While the individual activation of steel slag or blast furnace slag has been widely studied [

13,

14], the interaction of these materials with barium slag remains complex. The existing literature suggests that barium slag can participate in activation processes, whereby residual CaO and surface-active species may enhance hydration [

15,

16,

17]. However, most extant research is chiefly concentrated on untreated BS or simple BS-stabilized soils [

18,

19], leaving the complex interactions in multi-solid-waste systems largely unexplored.

Crucially, a significant research gap remains: the combined hydration-microstructure evolution and Ba-immobilization mechanisms of harmlessly treated barium slag (HTBS) mixed with multiple industrial wastes have not been systematically elucidated. Specifically, the following research questions need to be addressed: (1) Can the residual sulfate in HTBS act as an activator for slag hydration? (2) How does the complex multi-solid-waste system achieve the “dual-locking” of heavy metals and strength development simultaneously?

To address these questions, this study proposes the following hypothesis: The sulfate-rich HTBS can serve not only as an aggregate but also as a partial sulfate activator. We hypothesize that under the alkaline environment provided by the SWB binder, the coupling of silicate–aluminate–sulfate reactions will promote the formation of a dense C–S–H/AFt network. This network is expected to physically encapsulate the chemically stable BaSO4 precipitates, thereby achieving superior mechanical strength and environmental safety compared to simple stabilization methods.

Consequently, this work aims to (1) systematically investigate the mechanical properties and environmental stability of the HTBS-SWB system; (2) elucidate the pore structure evolution and phase transformation using advanced microstructural analyses; and (3) verify the long-term “dual-immobilization” mechanism of Ba2+. This study provides essential technical guidance for the high-value utilization of hazardous barium slag in sustainable road engineering.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

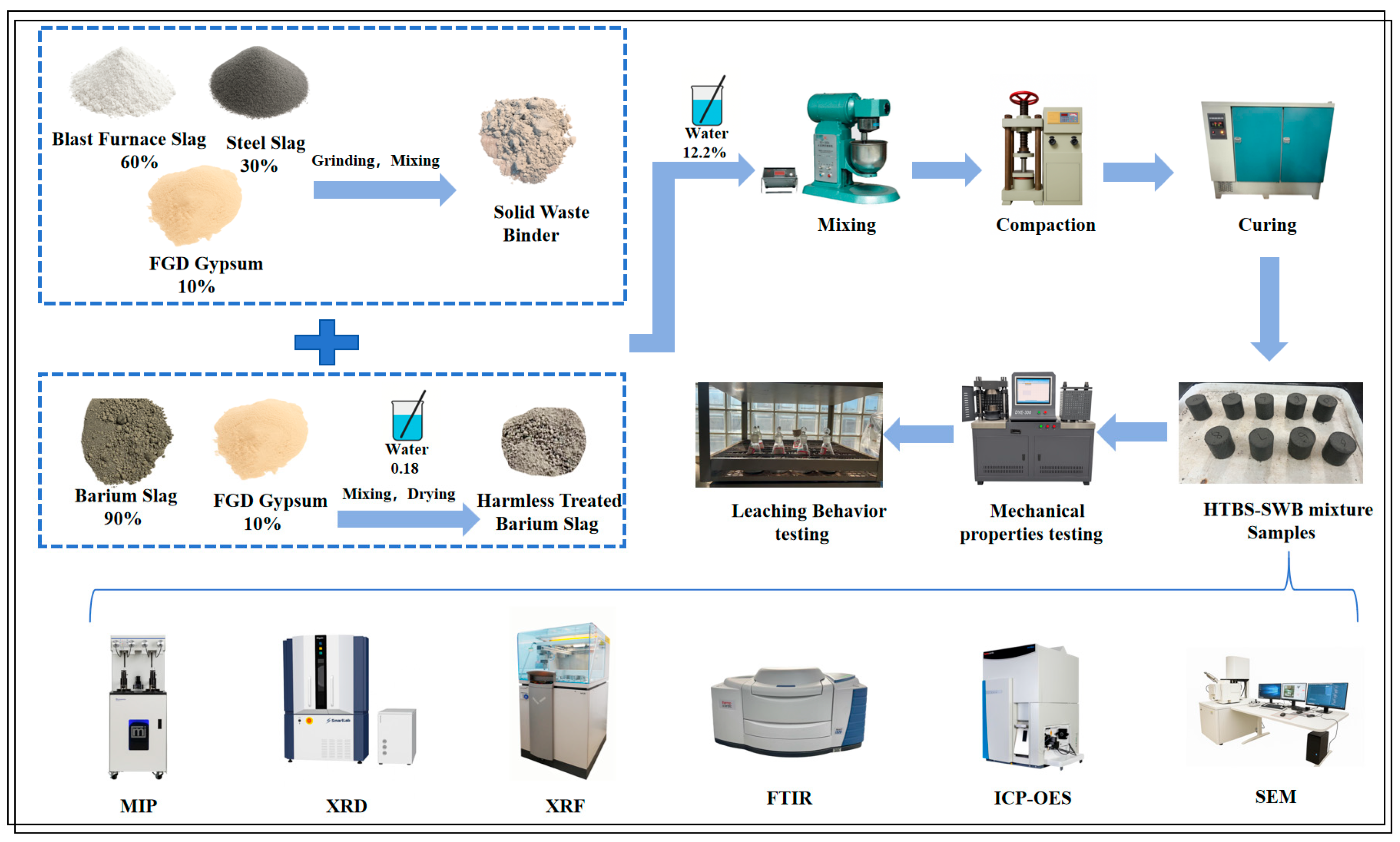

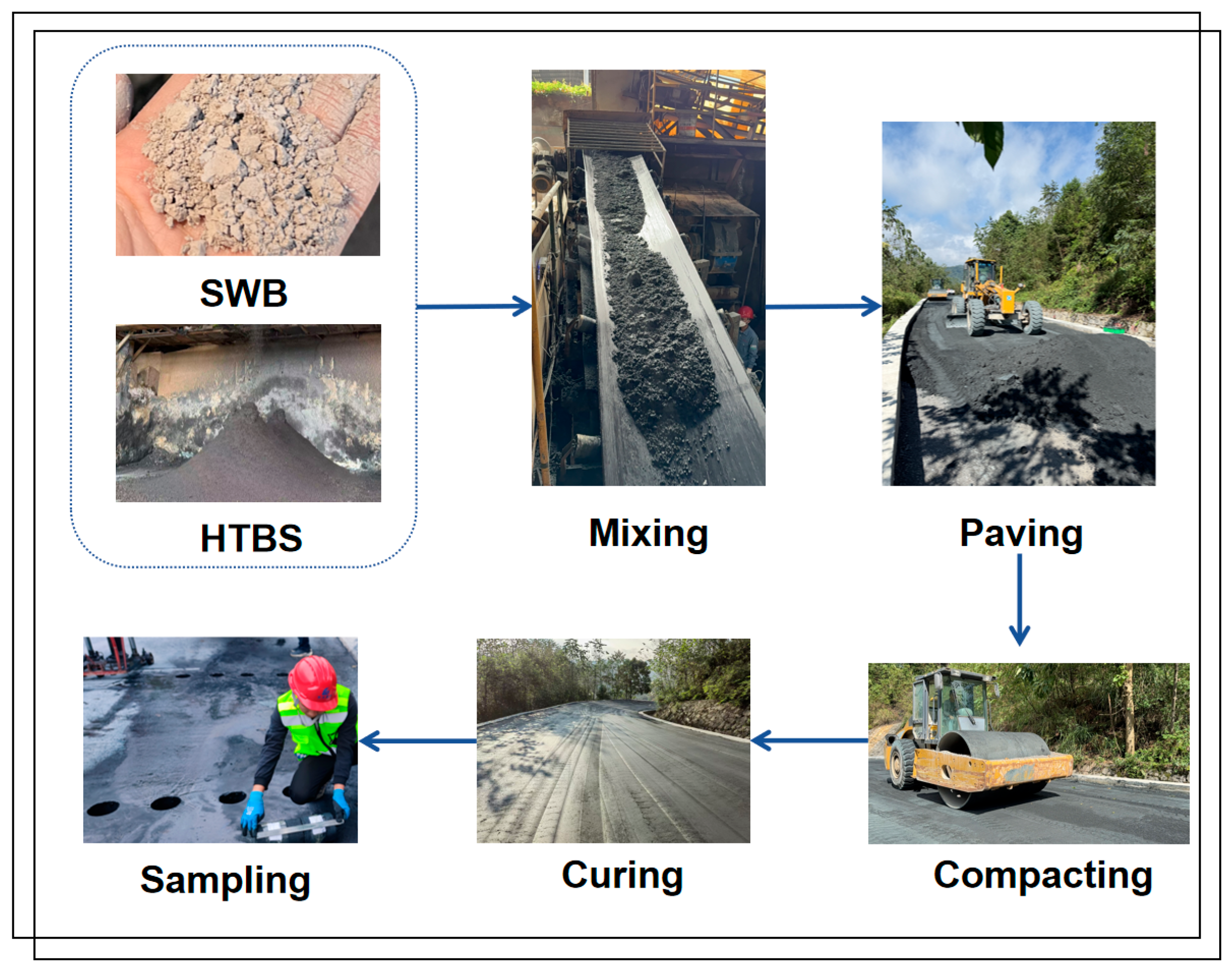

The raw materials employed in this study consist of harmless treated barium slag (HTBS) and a solid-waste-based binder (SWB),and the overall preparation flow chart is shown in

Figure 1. The harmless treated barium slag utilized in this study was prepared using a co-precipitation method with Flue Gas Desulfurization (FGD) gypsum, as detailed in our previous study [

9]. Specifically, the raw barium slag and FGD gypsum were first dried at 50 °C for 12 h to remove excess moisture. Subsequently, the materials were mixed at a mass ratio of 9:1 (Barium Slag:FGD Gypsum) with an appropriate amount of water to induce the chemical reaction. This process utilizes a synergistic precipitation mechanism where soluble Ba

2+ ions react with SO

42− provided by the gypsum to form stable, insoluble BaSO

4 minerals. This pre-treatment effectively reduces the leaching concentration of barium ions to below the hazardous waste limit, rendering the material safe for subsequent utilization. The mineralogical composition of HTBS is dominated by BaSO

4 and SiO

2, accompanied by minor BaCO

3 (see

Figure 2), indicating its stable structural characteristics. The mineralogical features of BaSO4 are consistent with the primary chemical components of the specimen, namely SiO

2, BaO, and SO

3 (see

Table 1).

The SWB is a non-clinker binder that is prepared by co-grinding steel slag, blast furnace slag, and flue-gas-desulfurization gypsum at a mass ratio of 6:3:1. The steel slag and blast furnace slag were mechanically ground to a specific surface area of 400 m

2/kg and 420 m

2/kg, respectively, to ensure sufficient hydration reactivity. The FGD gypsum was used as received with a fineness of 200 mesh. The mineral phases present in the sample are primarily reactive silicate phases, aluminate phases, and partially amorphous slag structures. Distinct diffraction peaks corresponding to C

2S and C

3S can be observed (see

Figure 2), thus demonstrating the capability to form hydration products such as C-S-H, AFt, and AFm under appropriate activation conditions. The principal chemical components of SWB are CaO, SiO

2, Al

2O

3 and Fe

2O

3. The elevated CaO content provides adequate Ca

2+ for hydration reactions, while the Si–Al components react with SO

42− to promote the formation of ettringite and other sulfate–aluminate phases, thereby enhancing the structural densification of the system.

In accordance with the stipulations outlined in JGJ 52-2006 [

20], the particle size distribution of untreated barium slag was subjected to rigorous testing through the utilisation of the standard sieve analysis method. The detailed gradation data are presented in

Table 2. It can be observed that the particle fraction between 600 μm and 4.75 mm accounts for 75.35% of the total mass, indicating that the material is primarily composed of medium-sized particles with a small portion of coarse particles around 4.75 mm. The presence of such a gradation structure confers two key benefits upon the material: firstly, it ensures an adequate specific surface area, and secondly, it provides a skeletal particle framework. The medium and fine particles provide sufficient interfacial contact area, while the coarse particles form an initial load-bearing skeleton within the mixture, which is favourable for promoting the coupled silicate–aluminate–sulfate reactions during hydration.

The environmental safety of the raw materials was evaluated in accordance with the Chinese standard HJ 557-2010 [

21] using the horizontal vibration method. The results of the heavy-metal leaching process are summarised in

Table 3. The leaching concentration of Ba

2+ in HTBS is 424.3 μg/L, which is far below the limit specified in the Class III groundwater standard [

22]. For SWB, elements such as Pb and Zn were not detected or exhibited extremely low concentrations, indicating that both raw materials possess satisfactory environmental safety and are suitable for application in the full–solid-waste road base material system.

2.2. Methods

The experimental programme involved systematic material characterisation, mechanical performance evaluation, and microstructural analysis of the HTBS–SWB solid-waste-based base materials. Firstly, the preparation procedures and mechanical behaviour of the mixtures were determined in accordance with the Test Specifications for Highway Engineering of Inorganic Binder Stabilized Materials (JTG 3441-2024) [

23] and the Test Methods of Soils for Highway Engineering (JTG 3430-2020) [

24]. Prior to testing, HTBS and SWB were dry-mixed at the designed mass ratios, and the required water amount—corresponding to the optimum moisture content obtained from compaction tests—was added. The mixture was then subjected to homogenisation using a forced-type mixer operating at a rotation speed of 48 rpm. The mixing duration was strictly controlled at 180 s to ensure uniform dispersion of the binder and moisture. After mixing, the material was placed in sealed plastic bags and left to rest for a period of 30 min to prevent moisture loss. This was followed by the preparation of the specimens and subsequent analyses.

A compaction test was conducted on the HTBS material, utilising varying moisture contents in accordance with the prescribed procedures outlined in the JTG 3441-2024 standard [

23]. For each moisture condition, the dry density corresponding to the applied compaction energy was measured, and the moisture–dry density curve was obtained to determine the optimum moisture content and maximum dry density. Specifically, HTBS was dried in an oven at 105 ± 5 °C for 24 h, cooled to room temperature, and mixed with the required amount of water using a spray bottle. Subsequent to the homogenisation process, the HTBS was meticulously arranged into a compaction mould in five layers, and the specimens were compacted using a hydraulic universal testing machine via static compaction. The mixture was loaded into the steel mould in five layers to ensure density uniformity. Each layer was pressed at a loading rate of 1 mm/min until the target density (corresponding to a 98% degree of compaction) was achieved, and the pressure was held for 2 min to minimize rebound effects. The compacted sample was then extruded through a sample extractor, weighed, and its moisture content was recorded.

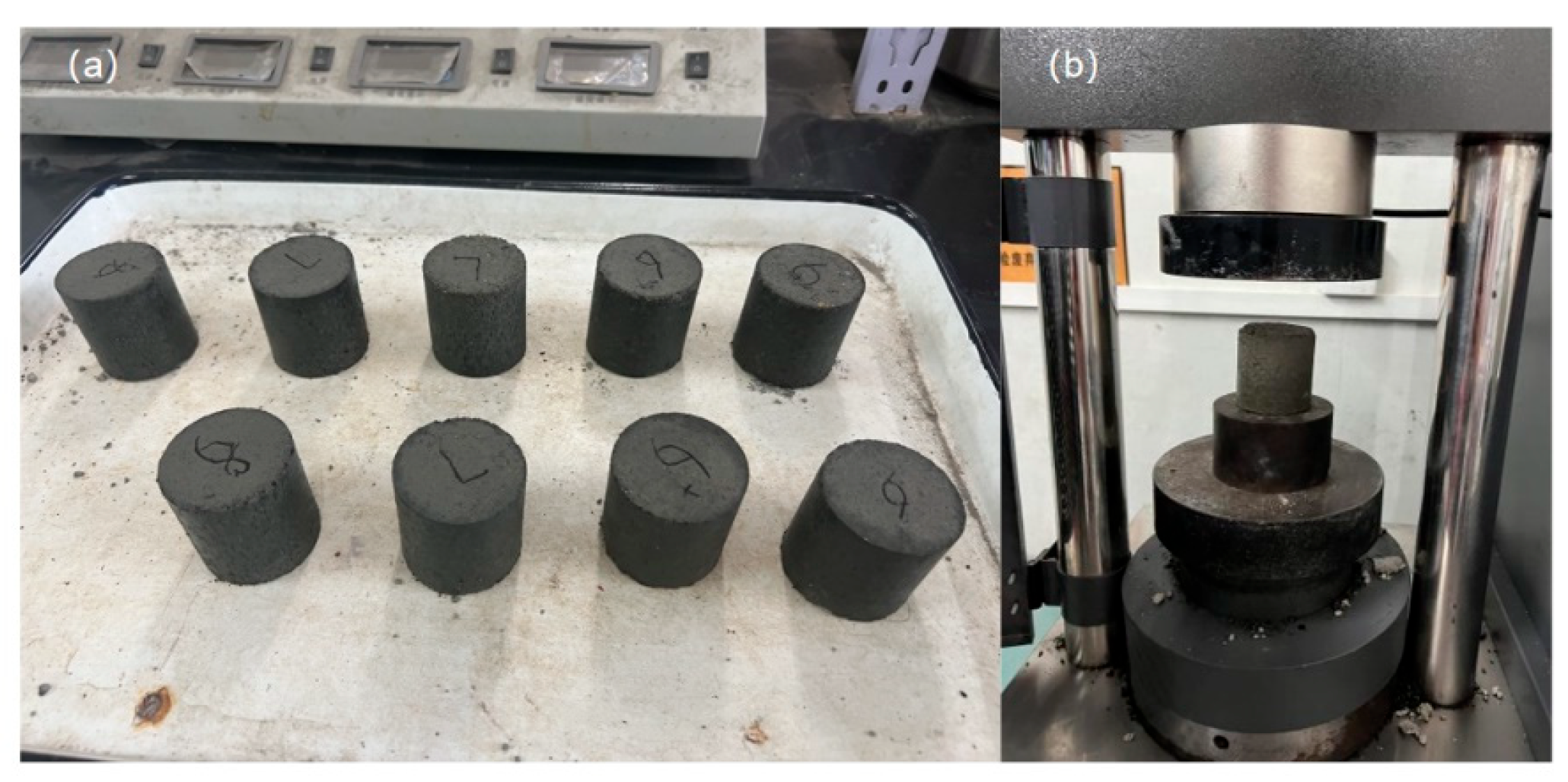

The unconfined compressive strength (UCS) tests were conducted in accordance with the specifications outlined in JTG 3441-2024. A universal testing machine was utilised in the compaction of the HTBS–SWB mixture within cylindrical moulds. To ensure the homogeneity of the mixtures, the raw materials were first dry-mixed for 2 min and then wet-mixed for another 2 min using a laboratory double-shaft mixer. Subsequent to the compaction process, the specimens were demoulded, weighed, and immediately wrapped in plastic film to prevent moisture evaporation. They were then subjected to a curing process in a standard curing chamber, maintained at a temperature of 20 ± 2 °C, with a relative humidity level greater than 95%. On the day prior to the commencement of testing, specimens were immersed in a 20 °C water bath for a duration of 24 h, subsequently surface-dried, and then loaded to failure using a compression testing machine. The stress–strain response was meticulously recorded during this process. For each mix proportion and curing age, six parallel specimens were prepared and tested to ensure statistical reliability. The average value was recorded as the representative strength, and the standard deviation was calculated to assess experimental variability.

The chemical compositions of the materials were analysed using a Rigaku ZSX Primus III + X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) The samples were then dried, ground to 200 mesh, and prepared by pressing or fusion according to the requirements of the instruments. The major chemical components and their relative contents were recorded. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted using a Rigaku SmartLab SE diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), scanning from 5° to 90°. This analysis was employed to compare hydration products formed in mixtures with different compositions at various curing ages.

Prior to microstructural analysis, the hydration reaction of the crushed samples was terminated by immersing them in absolute ethanol for 24 h. Subsequently, the samples were vacuum-dried at 60 °C to a constant weight. For FTIR analysis, the dried powder was mixed with KBr (mass ratio 1:100) and pressed into pellets. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was performed using a Thermo Fisher Nicolet iS20 instrument. (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) The spectral resolution was set to 4 cm−1, with 32 scans collected over 400–4000 cm−1. Changes in the Si–O, Al–O, and SO42− absorption bands were utilised to interpret the functional group structures. For SEM observation, the dried fragments were mounted on aluminum stubs and sputter-coated with a gold layer of approximately 10 nm thickness under vacuum conditions to improve conductivity. The microstructural morphology was then examined using a ZEISS GeminiSEM 300 scanning electron microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany) operating at 3 kV.

The pore structure characteristics were measured using a Micromeritics AutoPore V 9620 mercury intrusion porosimeter (MIP). The dried samples were then placed within the instrument chamber and subjected to stepwise pressure increments from low to high pressure. Mercury intrusion volumes were recorded to calculate total porosity, pore volume, and pore size distribution, enabling characterization of the HTBS–SWB pore structure.

The evaluation of heavy-metal leaching behaviour was conducted in accordance with the provisions stipulated in HJ 557-2010. Samples with a diameter of less than 9.5 mm were amalgamated with a leaching solution at a volumetric ratio of 10:1 and then subjected to vibration for a period of 8 h. Following this, the samples were filtered, and the concentrations of barium (Ba) and other elements present in the filtrate were determined using an Agilent 5110 Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). All leaching tests were conducted in triplicate, and the mean values were reported to ensure data accuracy. These concentrations were then compared with the relevant regulatory limits.

3. Results

3.1. Compaction Characteristics and Unconfined Compressive Strength

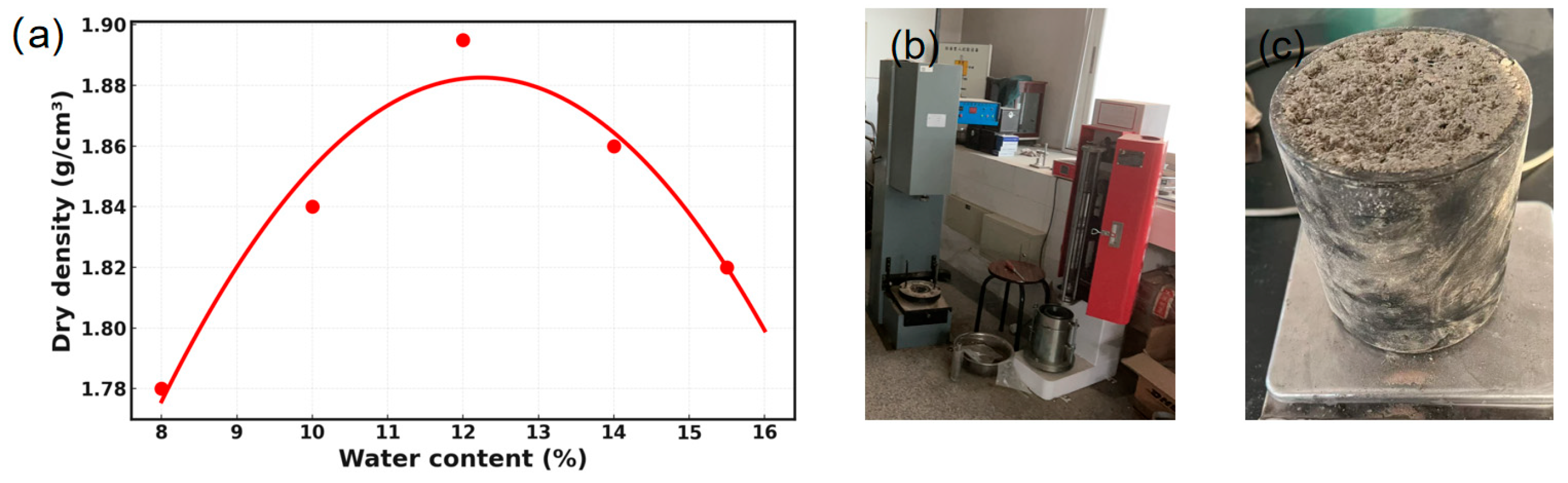

The moisture content–dry density curve was plotted with dry density on the vertical axis and moisture content on the horizontal axis. A quadratic polynomial was fitted to the experimental data points, and the peak of the fitted curve was taken as the optimum moisture content (OMC) and the corresponding maximum dry density. As demonstrated in

Figure 3a,

where the red dots represent the experimental dry density corresponding to the moisture content, the innocuous treated barium slag displays an OMC of 12.2% and a maximum dry density of 1.89 g/cm

3.

In cement-stabilized base materials, variations in the binder content typically alter the particle characteristics and water absorption behaviour of the mixture. This, in turn, may shift the optimum moisture content (OMC). In order to eliminate the interference caused by changes in compaction conditions and to ensure that the mechanical performance and microstructural evolution more clearly reflect the influence of binder dosage as a single variable, the present study adopts the OMC of HTBS—12.2%—as the molding moisture content for all mixtures. The specimens are then compressed to the maximum dry density.

The unconfined compressive strength (UCS) tests were performed on cylindrical specimens with dimensions of 50 mm × 50 mm(see

Figure 4). This specific geometry was selected in strict accordance with the Chinese Industrial Standard Test Methods of Materials Stabilized with Inorganic Binders for Highway Engineering (JTG 3441-2024) for fine-grained stabilized materials, ensuring the results are comparable to engineering practice standards. The mixture design proportions are presented in

Table 4.

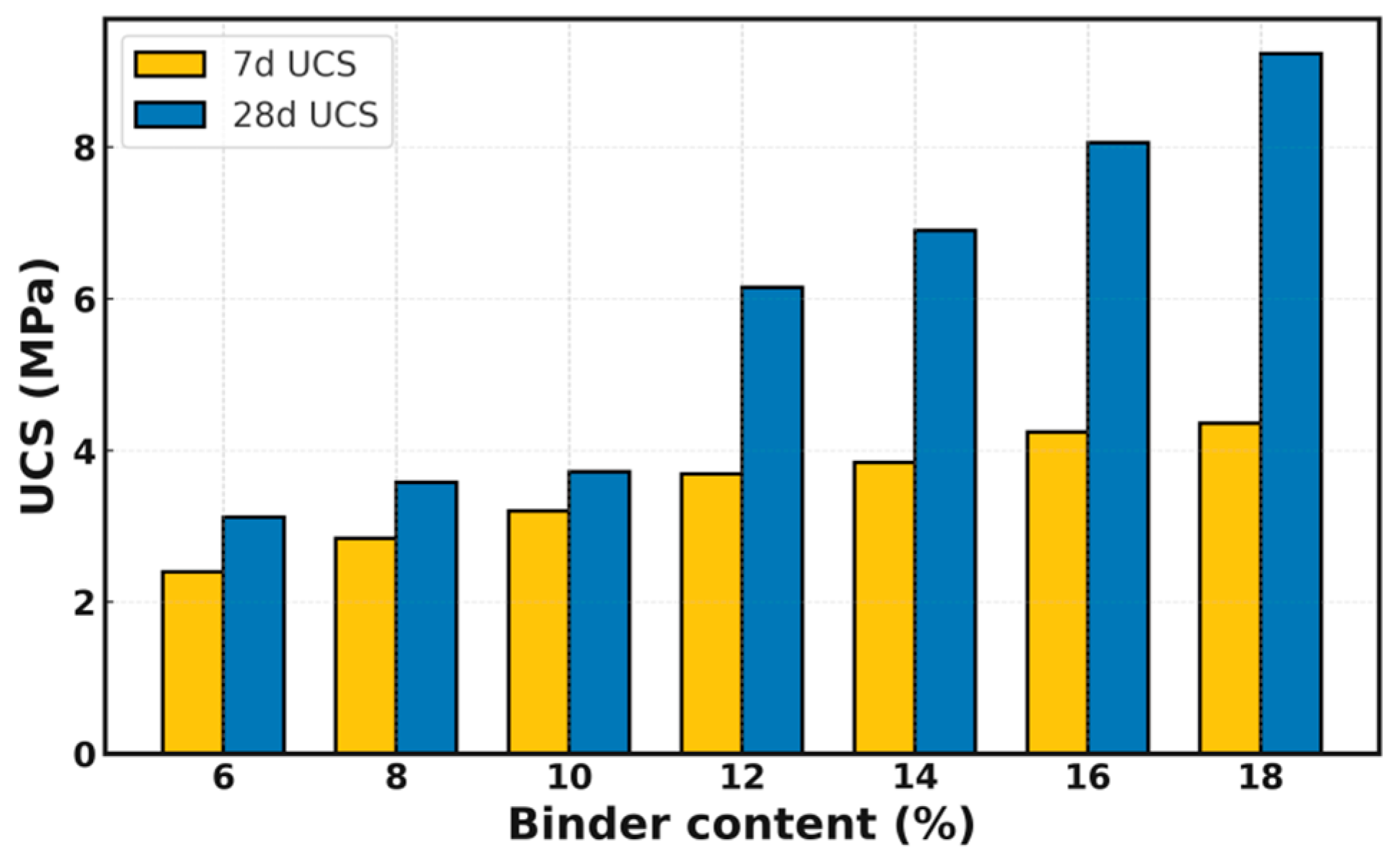

As demonstrated in

Figure 5, the 7-day and 28-day UCS results of the HTBS mixtures are presented. The findings suggest that the UCS increases in a consistent manner with the incorporation level of the solid waste binder, thereby demonstrating the system’s robust cementation potential and its capacity for sustained strength development.

An examination of the 7-day strength results reveals that when the binder content is set at 10%, the UCS attains 3.20 MPa. This outcome fulfils the stipulated 7-day strength requirement for base courses of expressways and Class-I highways, as outlined in the Test Specifications for Inorganic Binder Stabilized Materials in Highway Engineering (JTG 3441-2024). As the binder content continues to increase, a pronounced rise in the 28-day strength is observed. When the SWB content reaches 16%, the 28-day UCS increases to 8.06 MPa, reflecting the densification effect associated with the sufficient formation of hydration products at later ages. The 28-day strength of the samples was found to be approximately 1.5–2.2 times that of the 7-day value, thus demonstrating the typical mechanical behaviour of solid-waste-based cementitious systems. This behaviour is characterised by modest early-age growth followed by accelerated strength development. Furthermore, the mechanical performance of the optimized mixture (4.24 MPa at 7 days) compares favorably with international specifications. It meets the strength requirements for hydraulically bound mixtures defined in the European Standard EN 14227-1 [

25] (e.g., Class C3/4) and satisfies the typical strength criteria for cement-treated base materials recommended by AASHTO. Compared to conventional cement-stabilized macadam (CSM), which typically relies on energy-intensive cement clinker (dosage 4–6%) to achieve strength, the proposed HTBS–SWB system achieves comparable mechanical performance (meeting the 3–5 MPa standard for heavy-duty roads) using entirely industrial solid wastes. Unlike traditional materials, this system eliminates the dependency on cement clinker, offering a distinct advantage in terms of carbon emission reduction and cost-efficiency while maintaining the engineering reliability required for high-grade highway base layers.

These results confirm that the HTBS–SWB system maintains reliable compaction performance and exhibits substantial strength-development potential under a unified OMC condition, providing a solid basis for subsequent microstructural characterisation and engineering applicability assessments.

3.2. XRD

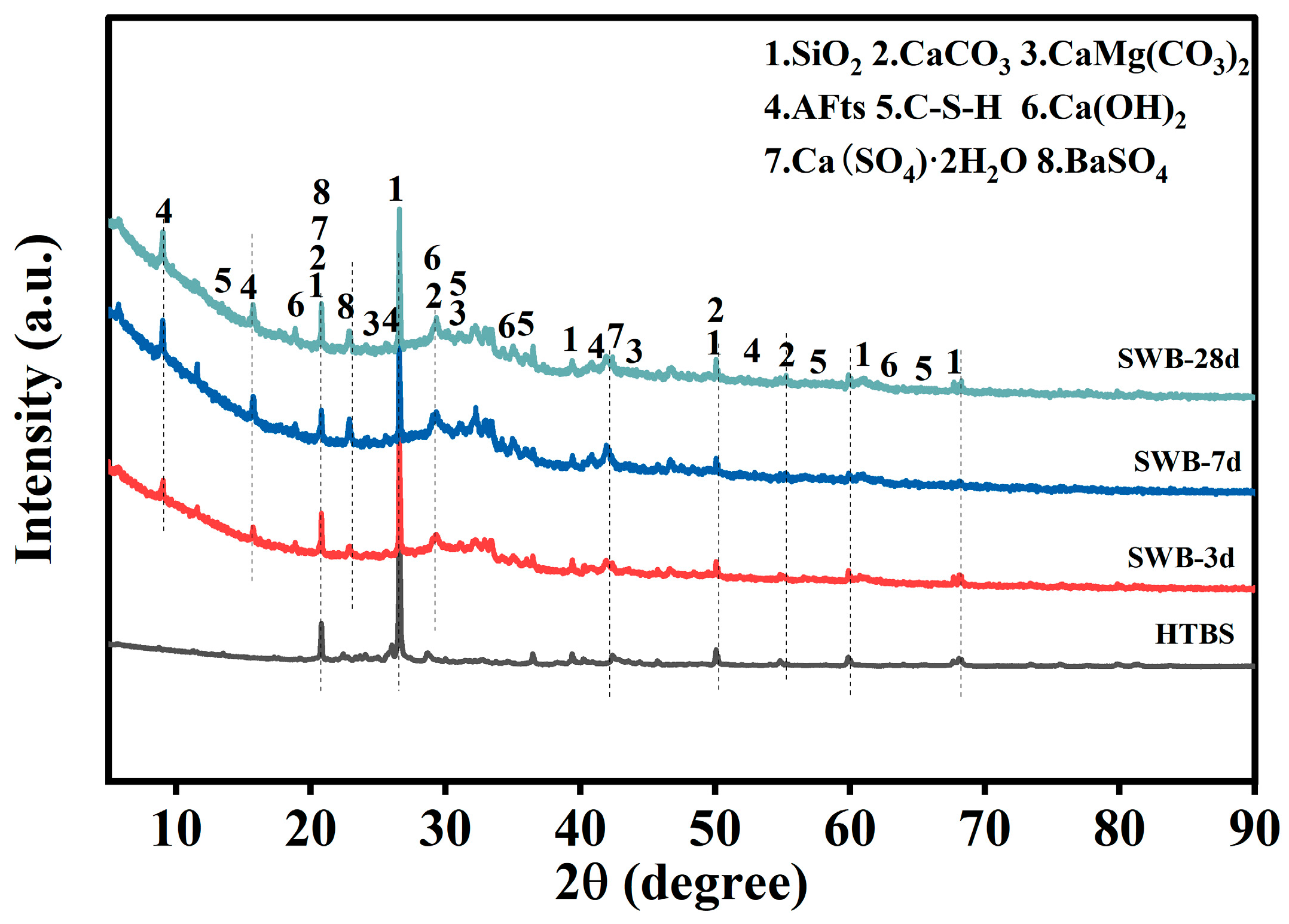

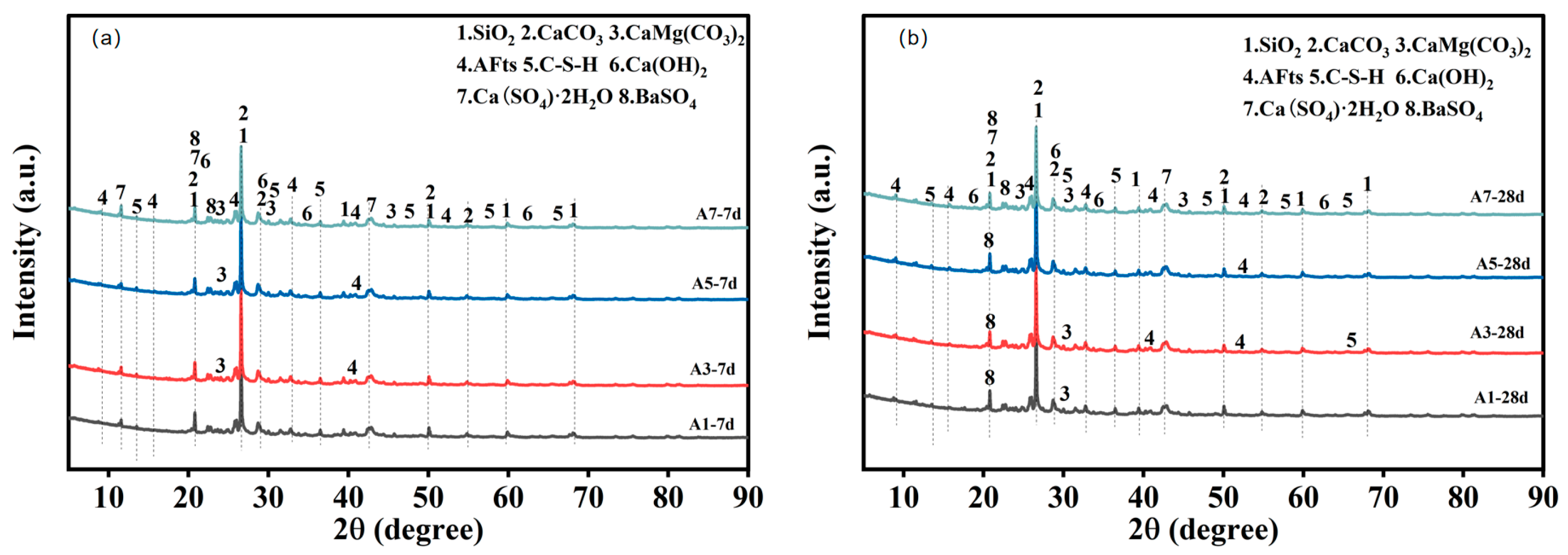

As illustrated in

Figure 6a,b, the 7-day and 28-day XRD patterns of the HTBS–SWB system are presented, under varying mix proportions (A1, A3, A5, A7). Distinct diffraction peaks of quartz (SiO

2) and barite (BaSO

4) are observed in all samples, with stable peak positions and sharp peak shapes. This indicates that these phases remain structurally inert throughout hydration and primarily function as skeletal or filling components. Furthermore, the analysis of all samples revealed the presence of a broad diffuse hump in the range of 20–35° (2θ), which is indicative of the amorphous signature of C–S–H gel. This finding suggests that silicate hydration occurs at early ages and results in the formation of amorphous gel products.

The presence of characteristic peaks of AFt (ettringite) in the low-angle region (approximately 2θ = 9° and 15°) is indicative of the existence of sulfate–aluminate reaction pathways within the system. Following a week-long period of observation, it was found that the content of hydration products varied among different mixtures. A7 exhibits stronger AFt peaks and a more pronounced C–S–H amorphous hump, suggesting that higher binder content supplies sufficient Ca2+, Al3+ and SO42−, thereby promoting more complete early-age hydration. In contrast, A1, A3 and A5 show more prominent quartz and BaSO4 peaks, reflecting a lower proportion of reactive phases and thus a relatively limited formation of early-age C–S–H and ettringite.

With the curing age extended to 28 days, the C–S–H amorphous hump becomes considerably more intense across all mixtures, indicating that silicate hydration continues during the later stage and contributes to gel accumulation and matrix densification. AFt remains identifiable, albeit with differing peak intensities across diverse mixtures. The A3-28d specimen displays more distinct AFt peaks and a more pronounced C–S–H hump. This finding suggests that a moderate binder dosage contributes to maintaining a balanced silicate–sulfate reaction, thereby facilitating sustained hydration activity at both early and late ages. In contrast, the overall peak intensity of A7-28d decreases, which can be attributed to the gradual depletion of reactive ions, the development of passivation layers on particle surfaces, or diffusion limitations, causing hydration kinetics to shift from rapid early reactions to slower later-stage progression. The XRD results reveal that the HTBS–SWB system exhibits a typical hydration evolution characterised by concurrent multiphase reactions at early ages and C–S–H–dominated development at later ages. The inert crystalline phases (SiO2, BaSO4) remain stable, while the peak evolution of AFt and C-S-H reflects the differences in hydration degree under varying curing ages and mix proportions.

3.3. FT-IR

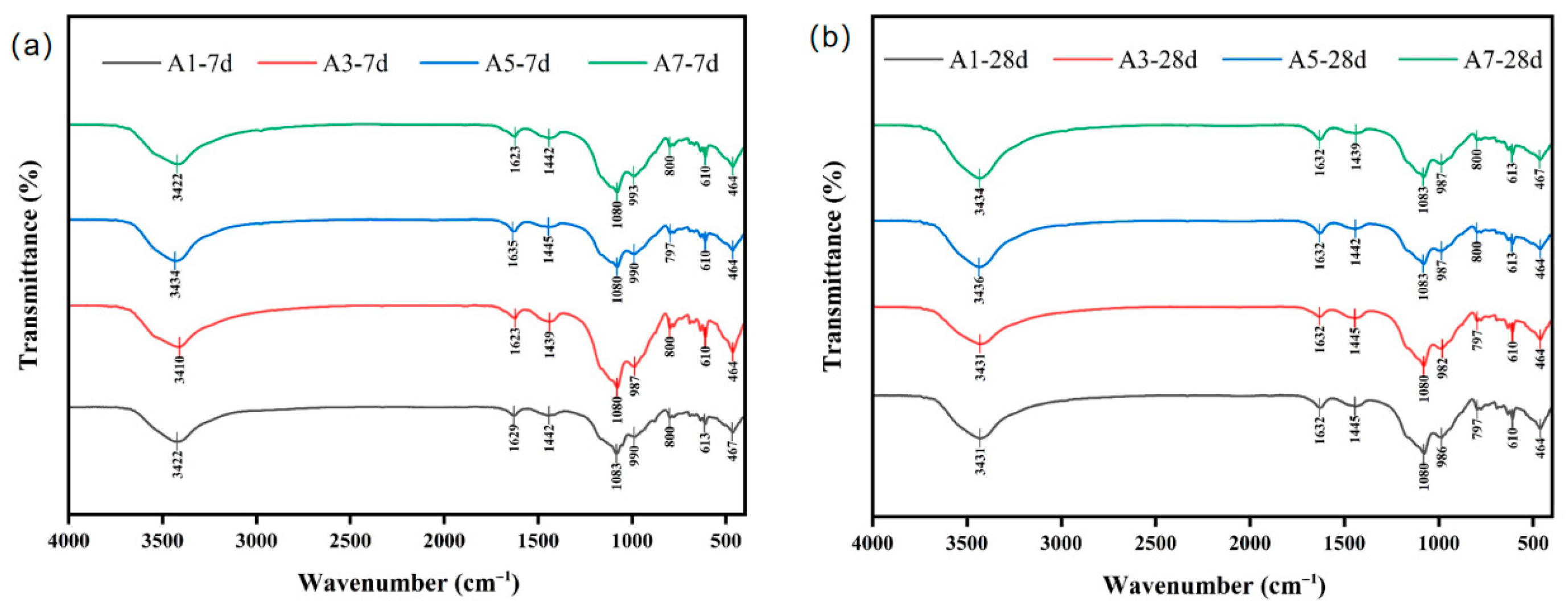

Figure 7a,b present the Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra of the samples at 7 and 28 days, respectively, thus illustrating the structural characteristics of hydration products in the SWB incorporated with HTBS at different mixing ratios and curing ages. As demonstrated in

Figure 1, the samples under scrutiny all exhibit a broad O–H stretching vibration band at 3422–3430 cm

−1. This vibration is primarily attributed to bound water and crystallization water in ettringite, Friedel’s salt, C–S–H gel, and portlandite [

26]. The absorption behaviour is consistent with the typical structural water bands observed in C–S–H systems and aluminate hydration products [

27]. At seven days, sample A1 demonstrates the weakest peak intensity, whereas at 28 days, A7 displays a significant enhancement, indicating that higher binder content and longer curing promote increased formation and crystallinity of hydroxyl-bearing hydration products.

A band located at 1629–1632 cm

−1 corresponds to the H–O–H bending vibration of molecular water [

28], while the weak absorption at 1442–1445 cm

−1 is attributed to the asymmetric stretching vibration of CO

32−, which is associated with slight carbonation of hydration products. These bands are consistent with structural water and carbonate vibrations commonly observed in silicate- and aluminate-based materials [

27].

The most characteristic band of silicate structures is the strong absorption peak near 1080 cm

−1, which corresponds to the asymmetric stretching vibration of Si–O–Si in C–S–H gels. This peak is indicative of the polymerisation degree of C–S–H and the development of the silicate network [

29]. At the seven-day stage, sample A3 displays the highest peak intensity, followed by A7, while A1 and A5 exhibit weaker signals. This trend indicates that moderate SWB content favours silicate polymerisation. By 28 days, the peak intensities of A1 and A3 increase substantially, whereas A7 shows limited enhancement and A5 remains nearly unchanged, suggesting greater age-sensitivity in low-binder systems and early saturation of hydration in high-binder mixtures. When combined with XRD observations, it is evident that sample A3 demonstrates superior C–S–H content and structural development.

The absorption band centred at 986–990 cm

−1 is primarily consistent with the stretching vibration of SO

42− within calcium sulfate or barium sulfate [

30], while the peak centred at 610 cm

−1 corresponds to the bending vibration of SO

42− [

31]. The presence of these species at both curing ages indicates the high stability of sulfate species in the system. The peak at 797–800 cm

−1 is attributed to the symmetric stretching vibration of Si–O–Si. As previously demonstrated, sample A3 exhibits the highest intensity within these regions, thus indicating that moderate binder content leads to more complete development of the silicate network.

In consideration of the aforementioned results, it can be concluded that although the hydration products formed in the different mix proportions share similar mineralogical types, clear variations exist in their development degree, silicate polymerization level, and the amount of hydroxyl-bearing hydration products. The low and medium-binder-content mixtures demonstrate heightened sensitivity to curing age, exhibiting uninterrupted enhancement in hydration and structural evolution. Conversely, the high-binder-content system exhibits a rapid reaction at the early age but demonstrates limited enhancement at later stages. Concurrently, sulfate-containing crystalline phases exhibit remarkable stability throughout the hydration process, thereby providing both skeletal support and cooperative effects during the initial formation of the hardened structure.

3.4. SEM and EDS

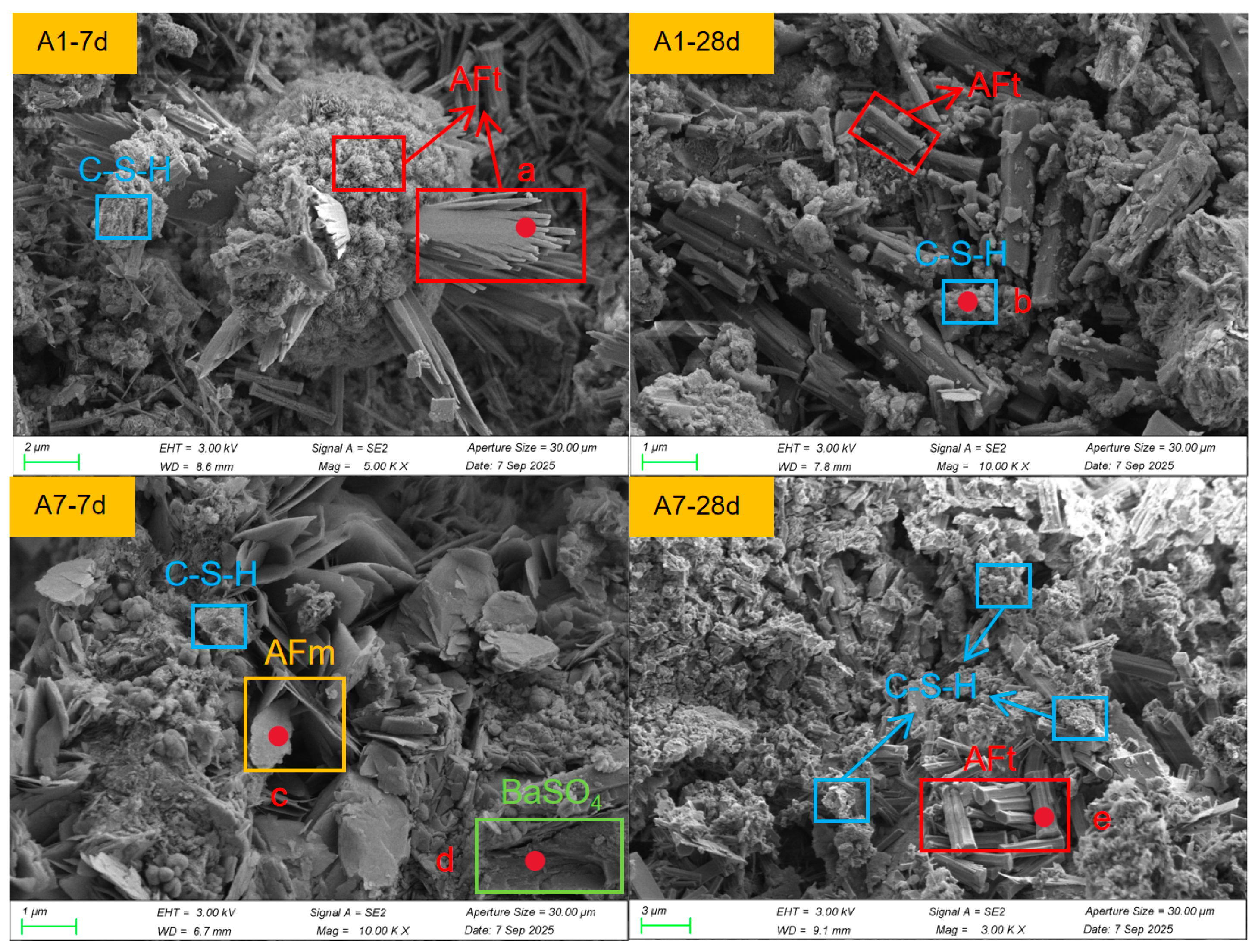

In

Figure 8, the SEM microstructures of mixtures A1 and A7 are presented at curing ages of 7 d and 28 d, respectively. The specific locations selected for Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) analysis are marked as a–e in the figure, and their corresponding elemental compositions are listed in

Table 5.The HTBS–SWB system demonstrates a characteristic hydration-product evolution process, characterised by the formation of needle-like ettringite (AFt), plate-like AFm, flocculent C–S–H gel, and unreacted BaSO

4 particles. As the curing age increases, the system undergoes a gradual transformation from an initial crystalline skeleton to a dense crystal–gel composite structure. This transition is in accordance with the hydration pathways that have been elucidated through XRD and FTIR analyses [

29].

At 7 d, sample A1 is characterised by the predominance of AFt formation. The SEM images display abundant radiating and cluster-like long needle-shaped AFt crystals, which are typical morphologies associated with rapid early-age sulfate–aluminate hydration [

32]. Only a limited amount of flocculent C–S–H is observed between the AFt bundles, indicating that silicate hydration has initiated but remains at an early stage, resulting in a relatively loose microstructure. EDS at the AFt region (Spot a) shows signals of Ca, Si, Al, and S—typical of AFt/C–S–H coexisting zones—and a small amount of Ba, suggesting that localized Ba deposition or adsorption has already occurred during early hydration.

The A7–7 d specimen exhibits a more complex multiphase assemblage. In addition to needle-like AFt, clearly defined plate-like AFm is present, suggesting that the higher binder content alters the aluminate hydration pathway, leading to partial formation of AFm rather than complete conversion to AFt. The amount of C–S–H in A7–7 d is notably higher than that in A1, forming extensive flocculent gel clusters, reflecting a more active silicate reaction. EDS results (Spot c) show enrichment in Al, Si, and Ca together with detectable Ba, consistent with regions where AFm and C–S–H coexist. Dense BaSO4 particles (Spot d) exhibit clear boundaries and Ba–S–O elemental signatures, confirming that Ba is present mainly as a stable sulfate precipitate, in agreement with the BaSO4 phase detected by XRD.

At 28 days, A7 develops a highly compact microstructure. AFt forms an intertwined three-dimensional network, while C–S–H extensively occupies the intercrystal spaces and coats particle surfaces, resulting in a markedly dense matrix. AFm becomes less prevalent compared with 7 d, indicating that the aluminate hydration pathway progressively favors the formation of the thermodynamically stable AFt phase under sulfate-rich conditions [

33]. The EDS results for C–S–H (Spot e) are dominated by Ca–Si–O, without detectable Ba, suggesting that late-stage gel in the high-binder mixture arises mainly from silicate hydration, while Ba remains primarily associated with early-stage gels or independent BaSO

4 particles.

Overall, the combined SEM and EDS observations reveal a characteristic structural evolution within the HTBS–SWB system as a function of curing age and binder content. The system initially develops an AFt-dominated skeletal framework, followed by progressive C–S–H accumulation and pore filling, eventually forming a dense matrix composed of intergrown AFt and gel phases. In mixtures with higher SWB content, the coexistence of multiple hydration products is more prominent, and BaSO4 particles appear more distinct, whereas low-binder mixtures exhibit a clearer transition from AFt-dominated early structures to C–S–H–driven densification at later ages.

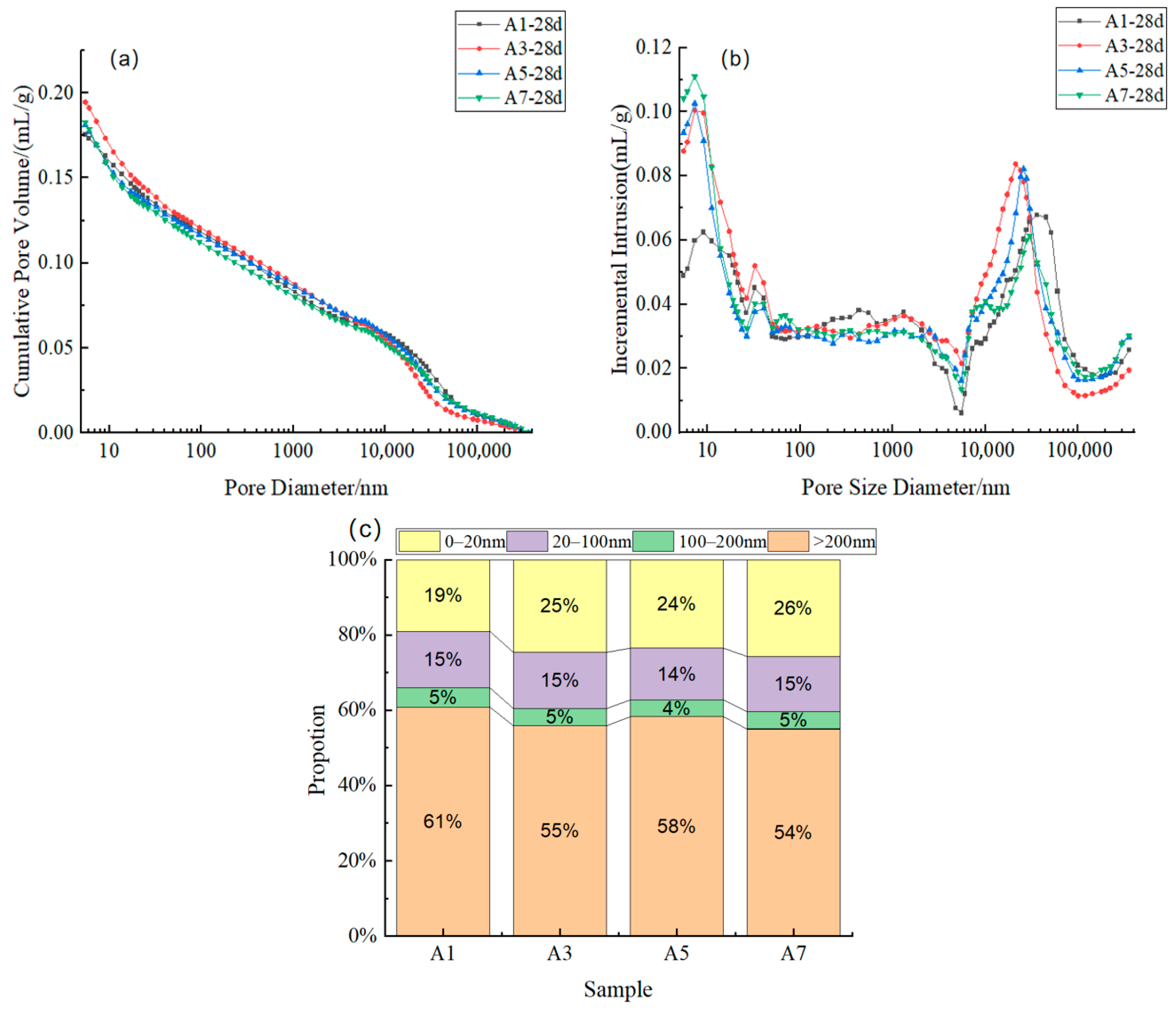

3.5. Pore Structure

Figure 9 presents the mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) results of mixtures A1, A3, A5, and A7 at 28 days, including cumulative mercury intrusion volume, differential pore-size distribution, and pore-size fraction. The threshold pore diameter and the most probable pore size are pivotal indicators employed to characterise the pore-network connectivity and dominant pore-size features of cementitious materials [

34]. The threshold pore diameter is the critical point at which significant changes in connectivity occur within the pore network. In contrast, the most probable pore size is indicative of the dominant peak of the pore structure.

It is evident from the differential pore-size distribution that two characteristic peaks can be discerned in all mixtures. The peak at 10–30 nm is indicative of C–S–H gel pores and fine capillary pores, while the peak at 2 × 10

4–8 × 10

4 nm corresponds to larger capillary pores. As the binder content increases from A1 to A7, both peaks shift towards smaller pore sizes, indicating that the pore-size distribution progressively concentrates within a finer pore range. In silicate–sulfate–aluminate solid-waste binder systems, the shrinkage of pore size towards smaller scales is generally driven by continuous silicate hydration and structural filling processes [

35].

The cumulative mercury intrusion volume further reflects the differences in pore structure. A1 exhibits a higher total pore volume, while A3, A5, and A7 show progressively reduced values. This finding indicates that, in systems with higher contents of reactive substances, large pores are gradually filled by hydration products. The results of the pore-size fraction analysis demonstrate that pores measuring over 200 nm account for 61% in A1, but decrease to approximately 54% in A7. Concurrently, the proportion of 0–20 nm gel pores increases to approximately 25–26% in A3 and A7. In silicate systems, the continuous growth of sheet-like C–S–H gels and the skeletal accumulation of AFt crystals can occupy capillary-pore spaces and form a more uniform and compact pore network [

36], thereby shifting the pore-size distribution towards gel pores at higher binder dosages.

From a microstructural perspective, numerous open capillary pores can still be observed in the SEM images of A1 at 7 days, whereas in A7 at 28 days, the sheet-like C–S–H network and interwoven AFt needle bundles nearly envelop the matrix, forming a continuous and dense structure. A reduction in porosity has been shown to enhance the compressive strength of hardened materials [

37]. This relationship is explicitly quantified in the present study: as the binder content increased from 6% (A1) to 18% (A7), the volume fraction of gel pores (<20 nm)—representing the accumulation of hydration products—rose from 19% to 26% (

Figure 9c). This microstructural densification directly corresponds to the substantial increase in 28-day UCS from approximately 3.12 MPa to over 9.23 MPa. This positive correlation confirms that pore-structure refinement, characterized by a shift in dominant pore size towards smaller ranges and an increased fraction of gel pores, serves as the fundamental microstructural basis for strength development in the HTBS–SWB system.

3.6. Environmental Safety and Leaching Characteristics

In order to evaluate the environmental safety of the HTBS–SWB all-solid-waste base material, Ba

2+ leaching tests were conducted on 28-day specimens with varying mixing ratios, in accordance with the Chinese standard HJ 557-2010. The Ba

2+ leaching concentrations of mixtures A1, A3, A5, and A7 ranged from 0.172 to 0.240 mg/L, which is significantly lower than the Ba limit of 0.7 mg/L specified in the Standards for Drinking Water Quality (GB 5749-2022) [

38] and far below the threshold value of 100 mg/L defined in the Identification Standards for Hazardous Waste—Identification for Leaching Toxicity (GB 5085.3-2007) [

39]. The detailed results are presented in

Table 6. The findings suggest that the leachable Ba

2+ present in HTBS becomes further immobilised following hydration and solidification. The limited variation in leaching concentrations observed across different mixing ratios indicates that the immobilization performance of HTBS within the binder system is stable.

Given the complex mineralogical composition of the raw barium slag (which typically contains unreacted barite, BaS, and BaO) and the potential impurities in industrial solid wastes, the consistently low leaching levels attributed to a dual-immobilization mechanism are significant. Firstly, from a chemical perspective, the FGD gypsum provides a sufficient and continuous supply of sulfate ions (SO42−). Due to the extremely low solubility product constant of barium sulfate (Ksp ≈ 1.08 × 10−10), the soluble Ba2+ ions react rapidly to form thermodynamically stable BaSO4 precipitates, which are highly resistant to dissolution even in complex ionic environments. Secondly, from a physical perspective, the hydration of the SWB component (steel slag and blast furnace slag) generates a dense cementitious matrix composed of C–S–H and C–A–S–H gels. As evidenced by the MIP and SEM results, this dense microstructure physically encapsulates the micro-sized BaSO4 precipitates and toxic trace elements, significantly extending the diffusion pathways and hindering the migration of pollutants to the external environment.

In order to further assess the long-term release behaviour of Ba in the HTBS–SWB base material, semi-dynamic leaching tests were conducted on 7-day specimens using Method 1315 of the Leaching Environmental Assessment Framework (LEAF) [

40], which was developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The method of evaluation employed in this study involves the assessment of Ba migration, with the hypothesis being that it is diffusion-controlled. This is achieved by monitoring the solute release at varying immersion times and calculating the apparent diffusion coefficient (Do) and the leaching index (LI).

As demonstrated in

Table 7, the Ba

2+ concentration demonstrates a tendency to initially increase and subsequently decrease with extended immersion duration (0.08–28 days). A transitional peak emerges at approximately seven days (0.69 mg/L for A1 and 0.63 mg/L for A4), followed by a decline to 0.137 mg/L and 0.159 mg/L at 28 days, respectively. This behaviour suggests that, in the early stages, the hydration structure has not yet fully developed and the pore network remains relatively open. As the curing process advances, the growth of C–S–H gels and interlaced AFt needle bundles progressively fills the pore space, thereby extending the diffusion pathways and reducing the leaching amount over time.

In

Table 8, the Leaching Index (LI) values for both A1 and A4 specimens are greater than 10, based on the cumulative release–time relationship obtained from LEAF Method 1315. In accordance with the evaluation criteria outlined in Method 1315, an LI value exceeding 9 signifies that the material demonstrates effective immobilisation and stabilisation capabilities in the presence of heavy metals [

40]. Consequently, the diffusion of Ba in the HTBS-SWB system is significantly retarded. It is anticipated that the HTBS–SWB base material will exhibit high environmental stability under prolonged service conditions, characterised by a minimal risk of diffusion-controlled leaching.

It is evident that, when taking into consideration the leachate concentrations, their stage-wise evolution, and the diffusion parameters, the HTBS–SWB system achieves stable immobilisation of Ba through the combined effects of hydration reactions and pore-structure refinement. This provides a robust environmental foundation for its engineering application in road base materials.

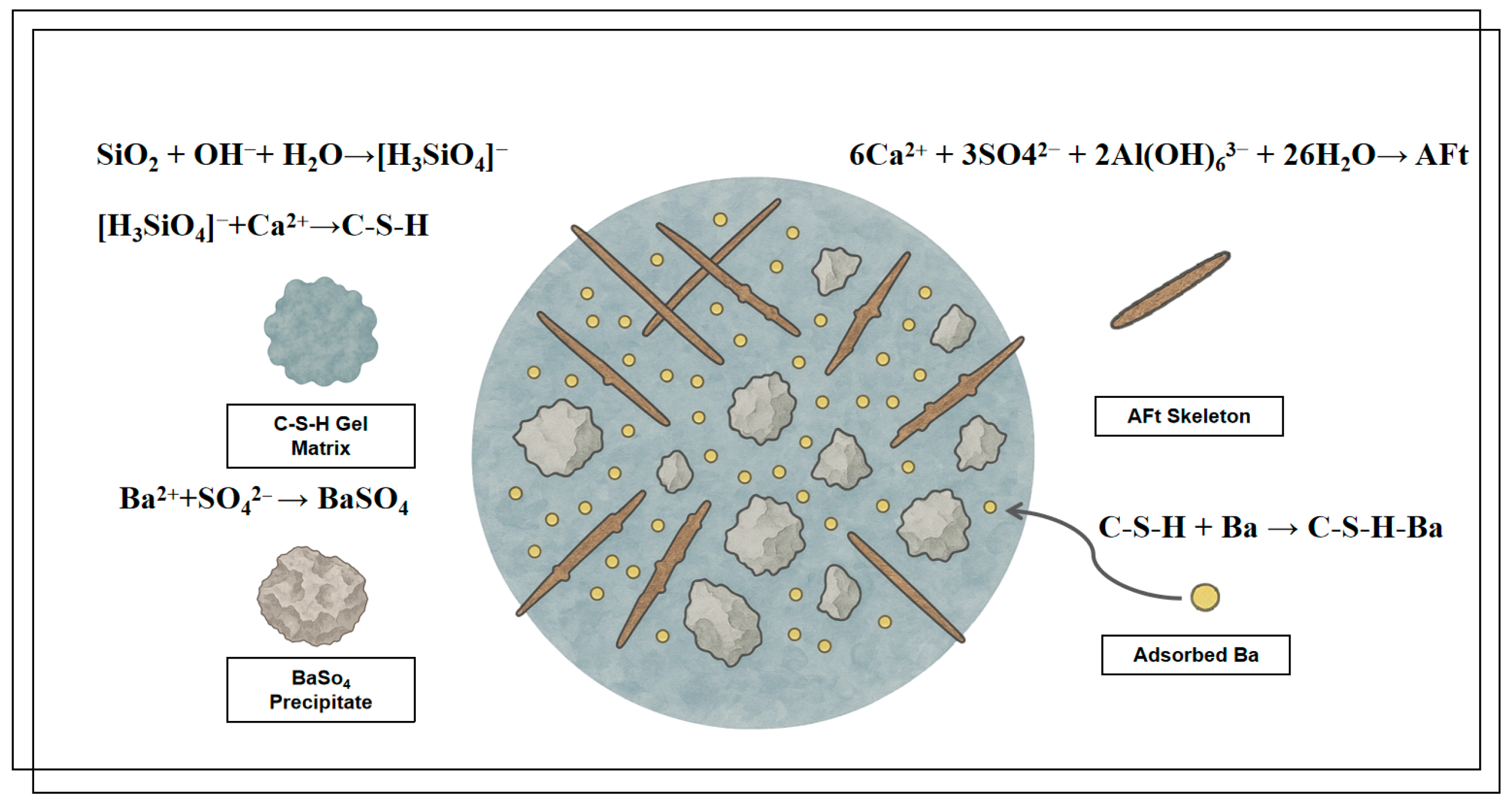

3.7. Reaction Pathways and Mechanisms of Ba Stabilization in the HTBS–SWB System

Based on the multi-scale characterization results, a cohesive hydration mechanism model for the HTBS–SWB system can be established

(see Figure 10) by unifying the mineralogical (XRD), chemical (FTIR), and morphological (SEM) evidence. The hydration process evolves in two coupled stages: (1) Skeletal Formation: In the early stage, the rapid reaction between aluminates and sulfates leads to the crystallization of ettringite (AFt). This is evidenced by the distinct low-angle diffraction peaks in XRD, the vibration bands of Al–O and SO

42− in FTIR, and the formation of characteristic needle-like crystal clusters observed in SEM. These crystals form the initial load-bearing skeleton. (2) Matrix Densification: As hydration progresses, the depolymerization of vitreous slag promotes the extensive formation of C–S–H gels. This is corroborated by the increasing intensity of the amorphous hump in XRD, the polymerization of Si–O–Si networks in FTIR, and the filling of flocculent gels into the AFt framework shown in SEM.

In the presence of alkaline conditions, the amorphous glass phase within the slag component of SWB becomes activated, resulting in depolymerisation and the subsequent release of soluble silicate and aluminate species. Subsequent to this, the species react with Ca

2+ to form C–S–H and C–A–S–H gels (Equations (1)–(4)). At the microscale, these gels progressively evolve into a continuous gel network that fills the pore spaces and coats unreacted particles. This process substantially extends the diffusion pathways of dissolved ions. Silicate-based gels have been demonstrated to exert a substantial inhibitory effect on the migration of divalent cations. This characteristic has been empirically substantiated in structural studies of alkali-activated binder systems [

41].

The SO

42− supplied by flue-gas-desulfurization gypsum reacts with aluminate species to form AFt (Equation (5)). SEM observations reveal that the AFt crystals manifest a distinctive needle-bundle morphology and are embedded within the surrounding gel network. The formation of AFt has been demonstrated to enhance the structural stability of the matrix, whilst also providing potential lattice incorporation sites for Ba

2+.

The immobilisation of soluble Ba

2+ in HTBS is primarily achieved through two pathways: (1) precipitation with SO

42− to form BaSO

4, a phase with extremely low solubility (Equation (6)); (2) surface adsorption on negatively charged functional groups of C-S-H, resulting in localised binding complexes (Equation (7)).

As the hydration reaction progresses, there is an accumulation of gel phases in conjunction with AFt crystals, which continuously fill the internal voids. This results in a gradual contraction and refinement of the pore structure. MIP results reveal that with increasing binder content, there is a shift in the pore-size distribution towards smaller pores, accompanied by a significant decrease in the proportion of large capillary pores. This structural evolution effectively reduces the overall diffusion coefficient of the system. In the semi-dynamic leaching test, both A1 and A4 exhibit leaching indices (LI) greater than 10, indicating that the combined effects of hydration products and pore-structure refinement impose strong diffusion constraints on Ba.

In summary, the progressive accumulation of C–S–H/C–A–S–H gels, the lattice accommodation capability of AFt, the stable precipitation of BaSO4, and the densification of pore structure collectively constitute the synergistic immobilisation mechanism of Ba within the HTBS-SWB system, thereby ensuring favourable long-term environmental stability under service conditions.

4. Engineering Application of HTBS–SWB Solid-Waste-Based Road Base Materials

4.1. Construction Technology

To verify the engineering applicability of the HTBS–SWB solid-waste-based binder in road-base construction, a field pilot project was carried out along a highway construction section in Guizhou Province. The trial section was 1.155 km in length, with an average embankment width of approximately 7.5 m, and the pavement type was a soil–rubble composite base.

A mixture containing 16% SWB and 84% HTBS was selected for base construction. This proportion was determined from prior laboratory investigations, which demonstrated favourable strength development, pore-structure densification, and stable Ba immobilisation. Both 7-day and 28-day strength values met the mechanical requirements for road-base materials while maintaining high environmental safety. The production and construction process of the HTBS–SWB solid-waste-based road base material is illustrated in

Figure 11.

Before construction, the HTBS raw material was dried to reduce its moisture content close to the OMC, ensuring adequate workability of the mixture. The SWB and HTBS were then blended using a forced-action mixer for 90 s, enabling uniform distribution of the binder on particle surfaces. The loose paving coefficient was controlled within the range of 1.53–1.58, with a paving thickness not exceeding 300 mm. Side forms were installed to ensure that the edge geometry and base width met design specifications.

Compaction was performed primarily using a static rolling method, progressing from the edges toward the centre. Initial compaction was conducted using a 12 t or 18 t double steel-wheel roller with two passes, followed by multiple passes of a 26 t steel-wheel roller. The roller speed during the first pass was strictly controlled to prevent the formation of surface waves or bulging. Adjacent rolling lanes overlapped by 1/3 to 1/2 of the roller width to ensure uniform compaction. If the measured compaction degree did not meet the required value, additional rolling passes were applied to further enhance density.

After construction, the base was cured naturally for no fewer than 7 days. A waterproof geotextile or plastic membrane was used to cover the base surface, and proper drainage was maintained to prevent water infiltration and associated structural damage. Traffic was prohibited on the base during curing to ensure long-term stability and continued strength development.

Upon completion of the construction and curing, a comprehensive quality inspection was conducted on the field pilot section. The degree of compaction was measured using the sand replacement method, yielding an average value of 97.5%, which meets the requirements for highway base layers. Furthermore, core samples were drilled from the base layer to evaluate the in-situ mechanical performance. The UCS of the 7-day core samples reached 7.2 MPa. This high strength indicates that the material is suitable for scenarios with stringent load-bearing requirements, such as base layers for expressways or heavy-load traffic roads. These results demonstrate that the optimised mixture facilitates the construction of high-performance barium-slag-based road structures, thereby broadening the application scope and enhancing the technical advancement and engineering adaptability of the demonstration project.

4.2. Environmental Impact Evaluation

To evaluate the ecological safety of the HTBS–SWB solid-waste-based base material under actual road service conditions, leaching tests were conducted on field-drilled core samples at ages of 3 d and 7 d following the Horizontal Oscillation Leaching Method for Hazardous Waste (HJ 557-2010). The target analytes included Zn, As, Ba, Hg, and Pb, and their concentrations in the leachates are summarised in

Table 9.

Overall, the measured concentrations of Zn, As, Hg, and Pb in all samples and at all ages were below the detection limits of the analytical method, indicating that these heavy metals were effectively immobilised within the solidified matrix and that their migration risk is negligible. This behaviour is closely related to the encapsulation, adsorption, and binding effects provided by the abundant C–S–H gels and AFt needle-like structures formed within the HTBS–SWB system. Ba, the primary element of environmental concern in the HTBS raw material, exhibited leaching concentrations of 0.184 mg/L at 3 d and 0.159 mg/L at 7 d—both far below the Class III groundwater limit for Ba in China (0.7 mg/L). This confirms that the material does not pose a substantive threat to the soil–groundwater environment under road base service conditions. Based on the hydration mechanism, the low Ba concentrations can be attributed to the combined effects of BaSO4 precipitation and the adsorption–encapsulation provided by C–S–H gels, both of which substantially reduce the proportion of leachable Ba species.

The HTBS–SWB road base material exhibits complete immobilisation of Zn, As, Hg, and Pb, and demonstrates excellent stability with respect to Ba. These results indicate that the material fully meets the environmental protection requirements for road base applications and can be safely employed in road construction.