1. Introduction

The mining industry is undergoing a transformative shift towards intelligent and automated operations, driven by the need for improved efficiency, safety, and sustainability. Open-pit mining, while economically advantageous, is confronted with complex geological variability, dynamic operational conditions, and escalating data volumes that challenge traditional management methods. Conventional approaches to ore blending, equipment monitoring, and performance assessment often rely on manual intervention or static models, which are inadequate for real-time, data-driven decision-making under uncertainty.

In recent years, both information entropy theory and deep learning have shown promise in addressing mining-related challenges. Information entropy has been applied to quantify uncertainty in geological data, safety evaluation, and resource prediction. Meanwhile, deep learning techniques have been widely adopted for visual inspection, time-series forecasting, and operational optimization in mining contexts. However, existing studies have largely treated these two paradigms in isolation: robust optimization models often rely on stochastic or fuzzy methods without leveraging deep learning’s representational power, while deep learning applications seldom explicitly quantify operational uncertainty or system-level robustness using information-theoretic measures.

This gap is particularly evident in integrated mine control systems, where decisions must be both data-informed and robust to real-world variability. Prior intelligent mining platforms have incorporated Internet of Things (IoT), Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), and AI for monitoring and dispatch, yet few have systematically embedded entropy-based robustness directly into deep learning-based planning and detection pipelines. Consequently, a unified framework is needed that not only leverages deep learning for prediction and recognition but also employs information entropy to explicitly model and manage uncertainty, thereby closing the loop between data-driven insights and robust operational execution.

To address this gap, this paper proposes a novel entropy–deep learning fusion framework for open-pit mine control. The core contributions are threefold:

We develop three hybrid models—IE-LSTM, IE-CNN, and IE-DNN—that integrate information entropy with deep learning architectures to respectively address dynamic ore blending, robust visual detection, and objective equipment evaluation. These models introduce entropy as a measurable criterion for robustness, false-alarm filtering, and objective weighting.

We implement a full-scale intelligent control system based on these models and deploy it in a real-world iron-ore mining environment.

We provide extensive industrial validation results that demonstrate tangible improvements in operational accuracy, resource utilization, equipment effectiveness, and economic performance, quantitatively validating the framework’s practical impact.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews relevant literature on open-pit mine control, entropy theory, and existing hybrid approaches.

Section 3 details the methodology and model architectures.

Section 4 presents the experimental results and analysis.

Section 5 describes system implementation and industrial validation. Finally,

Section 6 concludes with findings, limitations, and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Open-Pit Mine Control Technologies

Early automation in mining focused on programmable logic controllers for equipment control, but these systems often operated in isolation, leading to information silos. The advent of wireless sensor networks and industrial Ethernet enabled integrated automation and the development of digital mine platforms. More recently, the IoT, UAVs, and Artificial Intelligence (AI) have further advanced the capabilities of mine monitoring and control.

For instance, Arman et al. [

1] applied SWOT analysis to intelligent fleet management systems, while Sushma et al. [

2] used convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to improve object detection in foggy conditions. Zhang et al. [

3] optimized truck dispatching using sensor data, and Zhang et al. [

4] developed time-series anomaly detection for slope monitoring. UAVs have been widely adopted for surveying, dust monitoring, and volume estimation [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

In terms of stochastic mine planning, Madziwa et al. [

11] used the parameter minimum cutting network flow algorithm to perform random optimization on the final pit and backtracking design, while incorporating the randomness of commodity prices into the planning using an autoregressive distributed lag simulation model. Andrade et al. [

12] extended the previous development of integrated mining design and underground mine scheduling optimization by combining extended random integer programming formulas with long-term storage decisions.

While these studies demonstrate progress in digitization and task-specific automation, they often address components of mine operations in isolation. A critical gap remains in the development of an integrated, computationally coherent framework that unifies planning, perception, and evaluation under a consistent uncertainty-aware paradigm—a gap this study aims to fill.

2.2. Entropy Theory and Information Entropy in Modeling

Information entropy, introduced by Shannon, measures the uncertainty or information content of a system. It has been extended into various domains, including approximate entropy for time-series analysis, cross-entropy as a loss function in machine learning, and utility entropy for value-weighted information measures. Rough entropy was proposed for incomplete information systems, while approximate entropy was applied to mechanical signal analysis.

In terms of entropy-based modeling, Ahamed et al. [

13] first introduced a probability density function based on fractional entropy for suspension distribution models. In addition, they proposed a suspension distribution cumulative distribution function based on Mittag-Leffler function to further promote and apply this research. Kong et al. [

14] proposed a measurement system modeling method based on information entropy.

This represents a significant opportunity, as entropy’s capacity to quantify uncertainty and distribution uniformity can directly inform adaptive, risk-aware operational models.

2.3. Advanced Deep Learning

In terms of advanced deep learning, Qi et al. [

15] analyzed commonly used advanced deep learning techniques and some emerging deep learning techniques in battery thermal management systems, providing new insights for the integration of current deep learning technologies in new energy electric vehicles. Gao et al. [

16] developed an apple defect detection and quality grading system based on deep learning, integrating various advanced image processing techniques and machine learning algorithms to improve the automation and accuracy of apple quality monitoring. Shen et al. [

17] discussed the challenges and future trends related to advanced deep learning, providing new insights into the development of advanced deep learning algorithms for food quality and authenticity. Dong et al. [

18] introduced the latest progress in photon modeling and design based on deep learning, focusing on the basic principles and specific applications of various algorithms, and discussed the emerging research opportunities and challenges in this field.

2.4. Applications of Information Entropy in Mining

Information entropy has been increasingly applied in mining for safety monitoring, resource prediction, and efficiency evaluation. Hu [

19] combined entropy with AHP for safety risk modeling. In resource management, Zhang [

20] used entropy for multi-scale remote sensing fusion. Li [

21] extended entropy to 3D model uncertainty analysis and Xu [

22] developed an entropy-based green mine evaluation model.

While these works validate entropy’s utility in static evaluation and uncertainty description, they do not integrate it with predictive or prescriptive models in a closed-loop control context. Consequently, entropy has seldom been used to actively guide real-time operational decisions, such as dynamic blending or anomaly validation, which is a key innovation of our framework.

2.5. Ore Blending and Truck Dispatching

Ore blending models have evolved from linear programming [

23,

24,

25,

26] and integer dynamic programming [

27,

28] to intelligent algorithms such as genetic algorithms, particle swarm optimization, and artificial bee colonies [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Jélvez et al. [

34] proposed aggregation–decomposition heuristics, and Gilani et al. [

35] used ant colony optimization under grade uncertainty. Karaboga [

36] introduced the ABC algorithm, which was later applied to price prediction and grade estimation [

37,

38].

Truck dispatching systems have also advanced, with Kou et al. [

39] expanding performance metrics and Ahumada et al. [

40,

41] proposing multi-agent distributed scheduling. Xia et al. [

42] introduced dynamic load adjustment, and Huo et al. [

43] applied reinforcement learning to optimize fleet dispatch. Yao et al. [

44] proposed an open-pit mine truck scheduling system based on dynamic ore blending decisions.

Although intelligent scheduling has been extensively studied, few systems integrate a real-time, entropy-quantified measure of blending plan robustness directly into dispatch logic. Our IE-LSTM model addresses this by fusing an entropy-based robustness metric with LSTM-driven forecasts, enabling dynamic plans that balance efficiency with operational robustness.

2.6. Detection and Evaluation Models

Computer vision and deep learning have been widely adopted for equipment health monitoring. Yang et al. [

45] and Li et al. [

46] used machine vision for detecting defects in tires and corn kernels. In mining, Yue [

47] and Tian [

48] developed shovel tooth monitoring systems using CNNs, while Wang et al. [

49] and Hoang et al. [

50] applied vision systems for conveyor safety and blast vibration prediction. Yao et al. [

51] proposed a detection method for loose material blockage in the crushing port based on the SSD algorithm.

Performance evaluation has traditionally relied on expert scoring or AHP, which are subjective and lack dynamic adaptation. The integration of entropy-weighted methods with DNNs offers a more objective and data-driven approach to equipment assessment, yet a systematic framework that combines deep feature learning with entropy-based objective weighting for operational equipment scoring—as proposed in our IE-DNN model—remains novel in mining applications.

2.7. Synthesis and Research Gap

The reviewed literature reveals three salient trends:

Increasing integration of AI and IoT in mining automation.

Growing use of entropy for assessment and uncertainty description.

Sustained advancement in optimization and vision-based monitoring.

However, a critical synthesis is missing. Previous studies have not systematically embedded information entropy into deep learning-based control loops. Such integration is needed to simultaneously address uncertainty quantification, robustness enhancement, and objective evaluation within a unified operational framework. Existing hybrid models typically combine AI with optimization heuristics or stochastic programming, but do not leverage entropy as a real-time, computable metric for decision robustness and false-alarm filtering. This study bridges that gap by introducing an entropy–deep learning fusion paradigm, where entropy actively informs and stabilizes learning-driven decisions across blending, detection, and evaluation tasks.

3. Methodology

The proposed framework is operationalized through a hierarchical system architecture and three core algorithmic innovations.

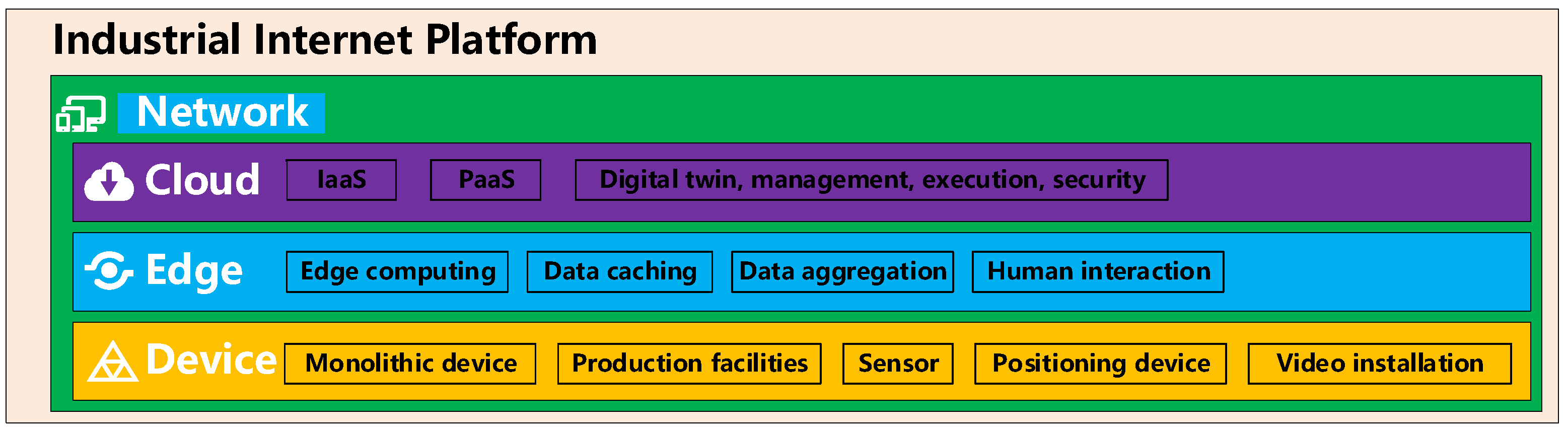

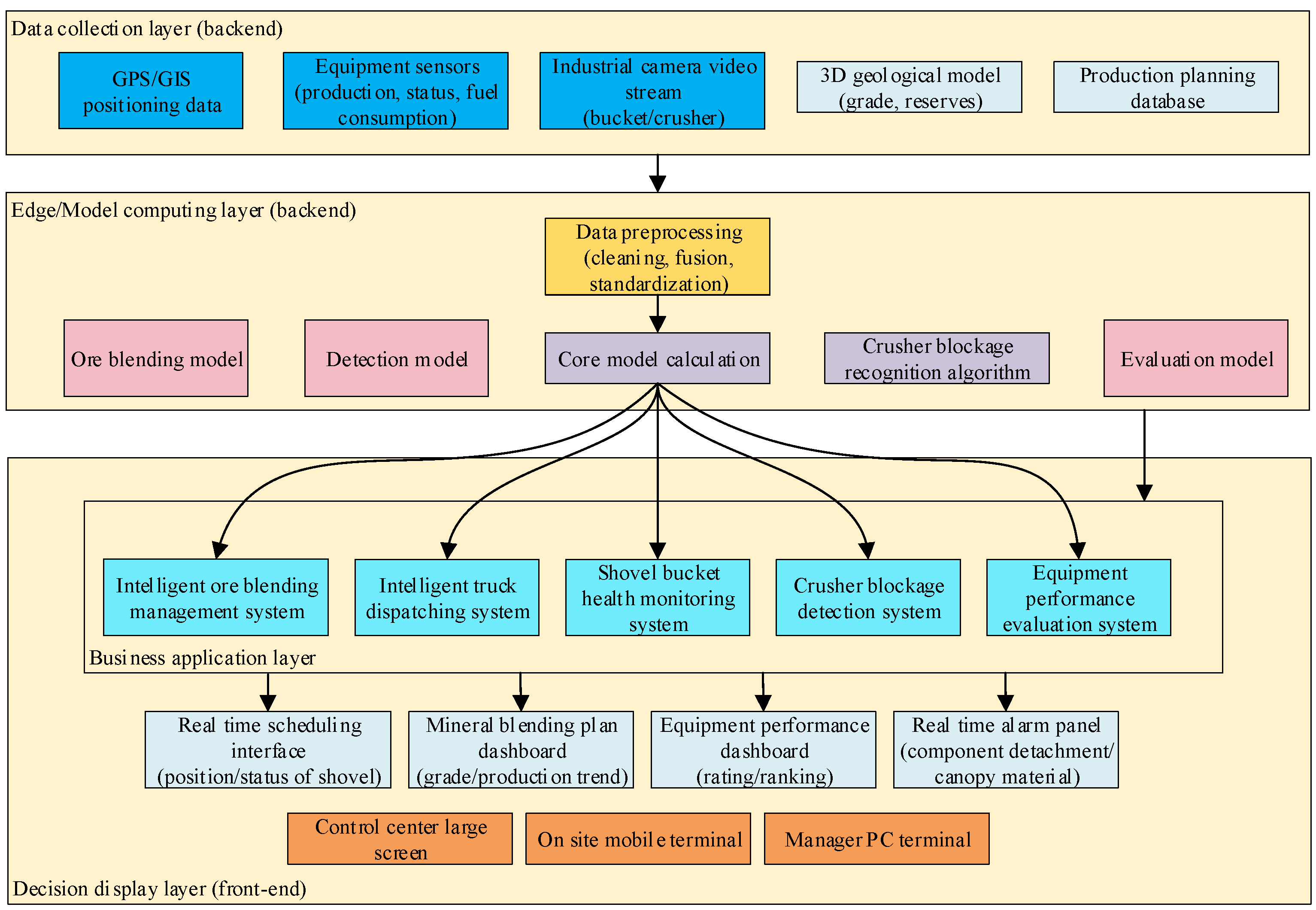

Figure 1 illustrates the overarching “Device-Edge-Cloud-Network” architecture of the Open-pit Mine Intelligent Comprehensive Control System (OMIMCS), which facilitates data flow and distributed computation.

Device layer: Includes physical assets (shovels, crushers) and data acquisition units (sensors, GPS, cameras).

Edge layer: Performs real-time preprocessing, lightweight computation, and data caching.

Cloud layer: Hosts the core intelligent models (IE-LSTM, IE-CNN, and IE-DNN) and platform services for optimization and management.

Network layer: Ensures reliable data transmission across all layers. The arrows indicate the primary direction of data flow (e.g., raw data uplink, control commands downlink).

As illustrated in

Figure 1, raw data from heterogeneous sources at the device layer are aggregated and preprocessed at the edge layer to meet latency requirements. Subsequently, feature-rich data is transmitted to the cloud layer, where the core IE-integrated models perform heavy-duty computations for planning, detection, and evaluation. The resulting decisions and insights are then visualized and dispatched back to the operational front-end via the network layer.

3.1. IE-LSTM Model for Dynamic and Robust Ore Blending

The ore blending problem involves determining the optimal allocation of ore from shovels to crushers over a planning period, typically a shift or a day. The objectives are to maximize total production, minimize transportation costs, and ensure that the blended ore at each crusher meets quality specifications (e.g., Fe grade, SiO2 content). The key challenge lies in making these decisions robust to uncertainties arising from geological variability, equipment status fluctuations, and production rate deviations.

3.1.1. Linear Programming (LP) for Static Optimization

The LP module provides the foundational optimization logic. Let be the decision variable representing the tonnage of ore sent from shovel to crusher . There are electric shovels, with respectively; and crushers, with respectively.

Minimize total transportation cost:

where

is the haulage distance.

- 2.

Constraints:

Quality constraints (e.g., for average grade

at crusher

)

This LP model, when solved, generates one or more statically optimal plans for a given set of input parameters.

3.1.2. LSTM Network for Temporal Dynamics Modeling

To model the temporal evolution of the system, a stacked Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network is employed, leveraging its ability to capture long-term dependencies in sequential data.

Input features: Historical data over a 24 h window, including shovel hourly production rates, real-time grade estimates from blast holes, equipment status codes, and operational delays.

Output: Forecasts of key parameters (e.g., shovel capacity, ore grade) for the next time step (t + 1).

Architecture: A two-layer stacked LSTM with 64 hidden units per layer, followed by a fully connected output layer. The dropout regularization (rate = 0.2) is applied between LSTM layers to prevent overfitting.

Training details: The model was trained on one year of hourly records from the mine’s manufacturing execution system and geological databases. Data were normalized using min–max scaling. Training was conducted over 100 epochs with a batch size of 32, using the Adam optimizer (initial learning rate 0.001) and early stopping based on validation loss (patience = 10 epochs). The loss function was Mean Squared Error (MSE).

The trained LSTM provides a dynamic blending suggestion that anticipates future states rather than relying solely on current conditions.

3.1.3. Information Entropy as a Robustness Metric and Fusion Strategy

The core innovation of the IE-LSTM model lies in integrating information entropy as a quantifiable measure of operational robustness. In the context of ore blending, a plan’s robustness refers to its ability to maintain performance under uncertainties such as shovel breakdowns or grade fluctuations.

- 1.

Theoretical rationale for entropy as robustness metric:

Information entropy, defined as

where

.

This entropy quantifies the “disorder” or dispersion in the material flow. A higher entropy value indicates a more distributed flow pattern (i.e., multiple shovels feeding multiple crushers), which reduces dependency on any single asset and thereby enhances system robustness to localized disruptions. Conversely, a low-entropy plan represents a concentrated, efficient, but potentially brittle flow. Therefore, entropy serves as a natural proxy for operational robustness in blending optimization.

- 2.

Multi-objective fusion rule:

The LP module may yield multiple feasible plans {

}. Simultaneously, the LSTM provides a dynamic forecast

. Instead of selecting a plan based solely on cost, we formulate a weighted-sum multi-objective decision rule:

where α and β are weighting coefficients that balance economic efficiency (α) and robustness (β). This approach corresponds to the common scalarization technique in multi-objective optimization, generating a Pareto-optimal solution that trades off between cost and entropy. The coefficients were calibrated via grid search on a month-long validation dataset, with final values set to α = 0.7 and β = 0.3, reflecting the mine’s operational preference for cost efficiency while retaining measurable robustness.

- 3.

Comparison with standard robust optimization:

Unlike stochastic or robust optimization methods that typically incorporate uncertainty through scenario-based or chance constraints, our entropy-based measure directly quantifies the structural dispersion of the plan. This offers a computationally efficient and interpretable metric for real-time robustness assessment, complementary to traditional uncertainty-aware optimization.

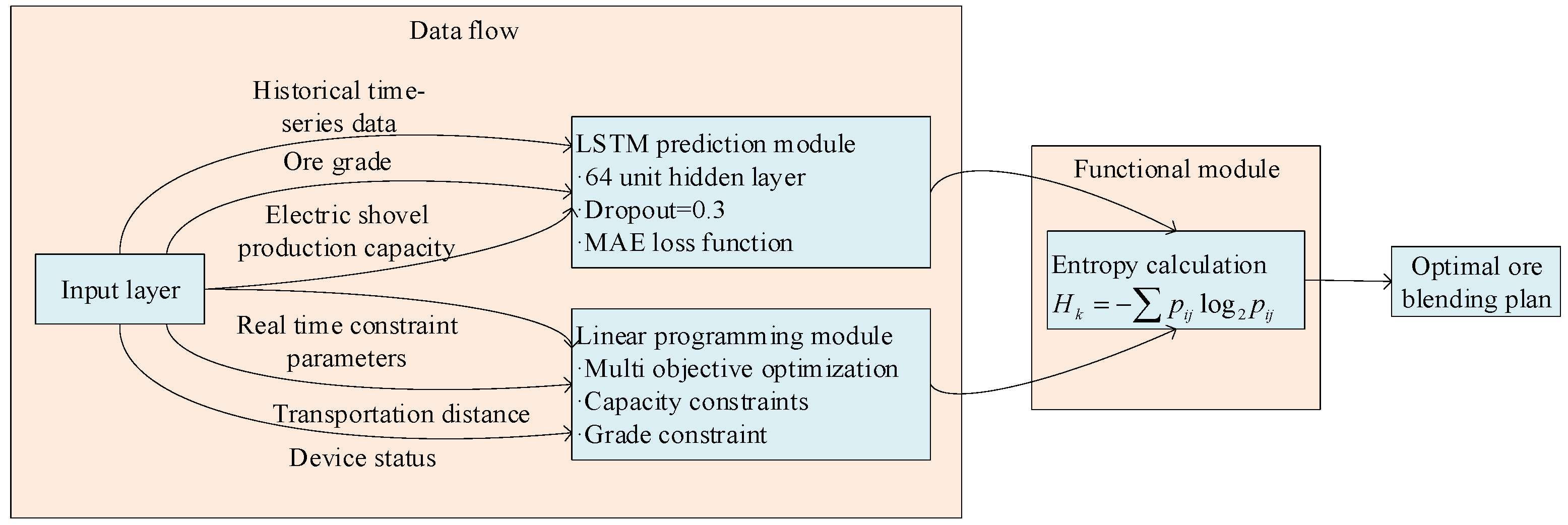

Figure 2 illustrates the overall workflow, integrating the static LP optimizer, the LSTM forecaster, and the entropy-based fusion module to produce a robust-optimal blending plan

.

The process integrates a static LP optimizer, an LSTM network for temporal forecasting, and an information entropy fusion module. Key steps include the following:

The LP module generates multiple feasible blending plans {} based on current constraints.

The LSTM network forecasts future operational parameters (e.g., shovel capacity, ore grade).

The entropy for each candidate plan is calculated using Equation (6).

The final robust-optimal plan is selected by minimizing the combined objective in Equation (7), which balances cost (α) and robustness (β).

3.2. IE-CNN Model for Robust Visual Detection in Harsh Environments

Detecting equipment anomalies visually in an open-pit mine is a classic small-object detection problem under extreme nuisance variability. The goal of the IE-CNN model is to achieve high precision without sacrificing recall.

3.2.1. Backbone CNN Architectures and Task-Specific Design

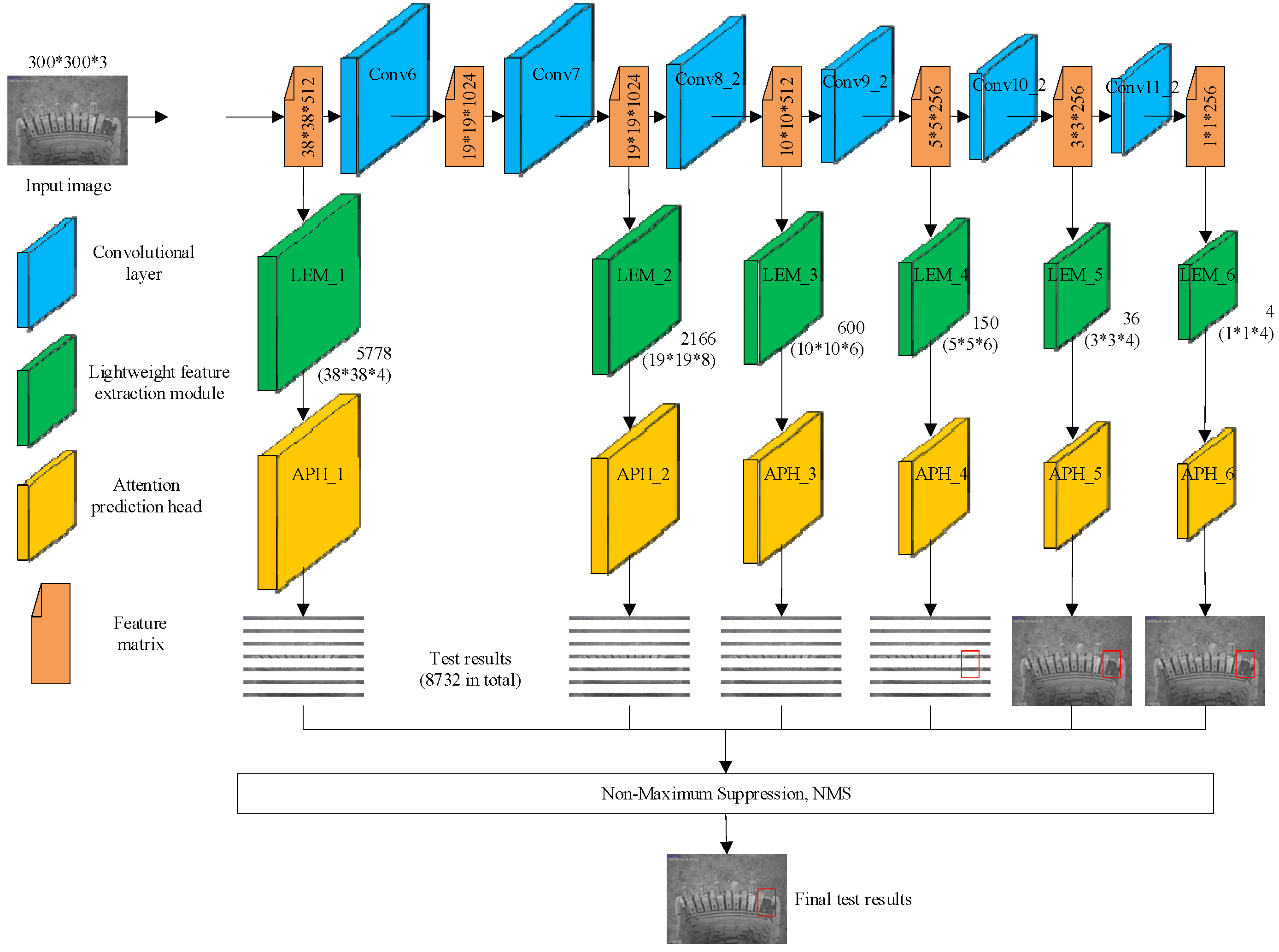

Detecting equipment anomalies in an open-pit mine is a challenging small-object detection problem characterized by extreme environmental variability. To address distinct operational requirements, two dedicated backbone architectures were implemented (see

Figure 3):

OPMD-Net for shovel health monitoring: For the critical task of detecting missing shovel teeth, A-frames, and sheaths—where accuracy is paramount—a custom network named OPMD-Net was developed. It uses a VGG-16 foundation for its strong generalization capability, enhanced with two novel modules.

Lightweight Extraction Module (LEM): This module employs a multi-branch structure with parallel and convolutions to efficiently extract multi-scale features, reducing the computational load for potential edge deployment.

Attention Prediction Head (APH): Incorporating a Normalized Attention Mechanism (NAM), the APH generates channel-wise and spatial attention maps. This forces the network to focus on informative features of small components, improving discrimination against cluttered backgrounds.

SSD with MobileNetV1 for crusher blockage detection: For the crusher station, where real-time processing on edge devices is crucial, the Single-Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD) framework with a MobileNetV1 backbone was adopted. MobileNetV1 uses depthwise separable convolutions, providing an optimal trade-off between detection speed and accuracy suitable for real-time video analytics.

This dual-backbone strategy ensures task-appropriate performance: OPMD-Net prioritizes high precision for detailed component inspection, while SSD MobileNetV1 satisfies the low-latency requirements for continuous crusher monitoring.

3.2.2. Information Entropy as a False Alarm Filter: Methodology and Calibration

Even with advanced backbones, false alarms (e.g., from shadows, reflections, or camera dirt) persist. A key observation is that such nuisances often appear in image regions with simple, uniform textures, whereas genuine anomalies (e.g., broken metal, ore blockages) exhibit complex, disordered textures.

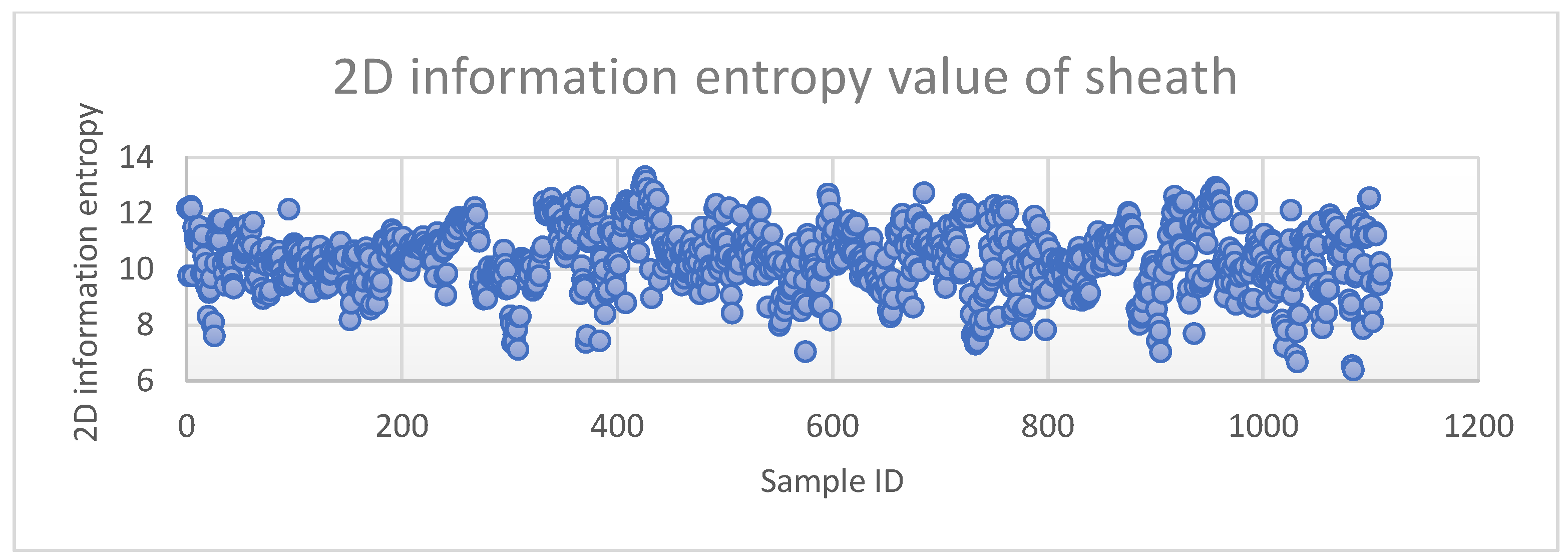

To leverage this observation, a post-processing filter based on the local two-dimensional information entropy of the detected region was implemented. The process is as follows:

Initial detection: The backbone CNN produces candidate detections with bounding boxes and confidence scores.

ROI extraction: For each candidate above a confidence threshold (e.g., 0.5), the corresponding Region of Interest (ROI) is extracted.

Two-dimensional entropy calculation: The texture complexity within the ROI is quantified using two-dimensional information entropy, calculated from the gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM). For an 8-bit grayscale ROI, the entropy

is computed as

where

is the probability of co-occurrence of the pixel intensity pair

for a given spatial offset (

). The ROI is used as the calculation window without resizing.

Threshold derivation and filtering: Class-specific entropy thresholds

are derived statistically from the training set. For each annotated positive sample, its

is computed. The threshold range is then defined as the 5th to 95th percentiles of this entropy distribution (see

Figure 4 for the “sheath” class). Candidate detections with

outside this empirically validated range are filtered out as probable false alarms.

This entropy-based filter acts as a computationally cheap, content-aware gate. It validates the CNN’s proposals by ensuring the textual complexity of the detected region is consistent with that of genuine anomalies, thereby significantly reducing false positives with a minimal, controlled impact on recall.

3.3. IE-DNN Model for Objective Equipment Performance Evaluation

This model aims to replace subjective, one-dimensional equipment evaluations with a comprehensive, data-driven, and objective scoring system.

3.3.1. Data Acquisition and Pre-Processing

Multi-source operational data for key equipment is collected on a monthly basis:

Trucks: dispatch count, total tonnage hauled, and total haulage distance.

Shovels: digging cycle count and total tonnage loaded.

Drills: number of holes drilled, total drilling time, and total meterage drilled.

Data is cleaned to remove outliers and missing values, and all indicators are normalized to a scale to be dimensionless.

3.3.2. DNN for Feature Representation Learning

A Deep Neural Network (DNN), specifically a deep autoencoder, is employed to learn a compact and representative feature set from the raw, potentially redundant, and non-linear operational indicators.

Autoencoder architecture: The model consists of a symmetric encoder–decoder structure.

Encoder: compresses the input data through three fully connected layers with dimensions [input size] → 32 → 16 → 8 neurons, using ReLU activation functions.

Bottleneck: The central layer (8 neurons) holds the compressed feature representation.

Decoder: Mirrors the encoder structure (8 → 16 → 32 → [input size]) to reconstruct the original input.

Training configuration: The network was trained in an unsupervised manner to minimize the reconstruction error, measured by the MSE loss function. Training used the Adam optimizer (learning rate = 0.001) over 150 epochs with a batch size of 16. A validation set (20% of the data) was used to implement early stopping (patience = 15 epochs) to prevent overfitting.

Feature extraction: Once trained, the decoder is discarded. The encoder is used to transform the original normalized data matrix X into a refined, lower-dimensional feature matrix . This process denoises the data and captures essential, non-linear characteristics of equipment performance.

3.3.3. Entropy Weighting Method for Objective Weighting: A Stepwise Illustration

The entropy weighting method determines indicator weights based on the amount of information each indicator provides. The underlying principle is that an indicator with a large variation in its values across different evaluation objects provides more information for discrimination and should be assigned a higher weight.

For a feature matrix with objects and indicators, the steps are as follows:

Calculate the proportion:

where

is the normalized value of indicator

for object

.

Calculate the entropy of indicator

The term ensures .

Calculate the divergence:

The larger , the more important the indicator .

Determine the objective weight:

These weights are entirely data-driven, and are free from human bias.

3.3.4. Comprehensive Score Calculation

The final performance score

for equipment

is computed as the weighted sum of its original normalized indicator values:

The scores are then linearly scaled to a range for easier interpretation. This score provides a holistic, fair, and transparent basis for comparing equipment and identifying underperformers.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

A comprehensive and statistically rigorous evaluation of the three proposed models is presented below. The experimental framework was designed to ensure reproducibility, robustness of conclusions, and practical relevance. Key aspects of this framework include the following:

Statistical validation: Performance differences between models were assessed for statistical significance. Paired t-tests (α = 0.05) were used for parametric metrics (e.g., cost, accuracy), while Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were applied to non-parametric data (e.g., rankings). Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals are reported for major performance indicators.

Model training and diagnostics: All deep learning components were trained using a dedicated validation set (15% of data) for hyperparameter tuning and early stopping (patience = 10 epochs). Training and validation loss curves were monitored to confirm convergence and absence of overfitting.

Computational efficiency: Model efficiency was evaluated using average inference latency (seconds) and, for vision models, computational complexity in Giga FLOPs (GFLOPs).

Dataset and preprocessing: Each model was evaluated on distinct, real-world datasets from the Qidashan Iron Mine. Detailed descriptions of sampling, class distributions, and augmentation strategies are provided in respective subsections.

Metric definitions: All reported metrics are explicitly defined using standard formulations to ensure clarity and comparability.

4.1. Performance of the IE-LSTM Ore Blending Model

4.1.1. IE-LSTM Model Experimental Setup

The IE-LSTM model was evaluated on a dataset from the Qidashan Iron Mine spanning Q2 2024, involving 7 electric shovels and 2 primary crushers. The dataset comprised daily records (sampled at shift-end) of shovel production, ore grades (Fe, SiO2), and Haul Distances. Data was normalized and split into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets. The proposed IE-LSTM was compared against four baselines: a traditional LP model, a standalone LSTM forecaster, a CNN-LSTM hybrid, and a Transformer-based sequence model.

4.1.2. Results and Discussion

Table 1 summarizes the test set performance over 30 independent runs. Paired

t-tests confirmed that IE-LSTM’s improvements over the second-best model for each metric were statistically significant (

p < 0.01).

Blending accuracy: Defined as , where is crusher count and is the average grade at crusher .

Grade fluctuation: A robustness metric calculated as the mean absolute percentage deviation of crusher feed grades from the planned values after simulating a major shovel failure.

Inference latency: Average wall-clock time for plan generation on a test server (Intel Xeon Gold 6226R, 128GB RAM).

The proposed IE-LSTM achieved the best performance, including the highest blending accuracy (93.6%) and lowest cost. Its lowest system entropy (H(Y) = 3.05) indicates an inherent selection of robust, low-dispersion flow plans. The sub-2 min latency is practical for operational planning. Training curves confirmed stable convergence without overfitting.

4.2. Performance of the IE-CNN Visual Detection Model

4.2.1. IE-CNN Model Experimental Setup

Two dedicated datasets were constructed:

Shovel component dataset: This dataset contained 9010 images from four electric shovels, annotated with four classes: bucket, sheath_detached, A_frame_missing, tooth_missing. The dataset exhibited class imbalance (e.g., “tooth_missing” was the minority class). Augmentation strategies included rotation (±15°), random brightness/contrast adjustment (±20%), and synthetic fog simulation to improve robustness.

Crusher blockage dataset: This dataset was composed of 5300 images from a primary crusher station, annotated with a single blockage class.

Models were compared on the shovel component task. The proposed IE-CNN (using the OPMD-Net backbone with entropy filtering) was evaluated against a Pure CNN (VGG-16) baseline, CNN + CBAM, CNN + Cutout, and CNN + Focal Loss. Computational cost was measured in GFLOPs and frames per second (FPS) on an NVIDIA Tesla V100.

4.2.2. Results on Shovel Health Monitoring

Table 2 presents results on the shovel component test set. The statistical superiority of IE-CNN in precision and FPR was confirmed via McNemar’s test (

p < 0.05) and Wilcoxon signed-rank test (

p < 0.01), respectively.

The IE-CNN model achieved a precision of 95.5% and an FPR of 4.8%, corresponding to a 73.7% reduction in false alarms compared to the baseline, with only a minimal and controlled reduction in recall. Its computational cost (15.7 GFLOPs) is comparable to the baseline, demonstrating the efficiency of the entropy filter.

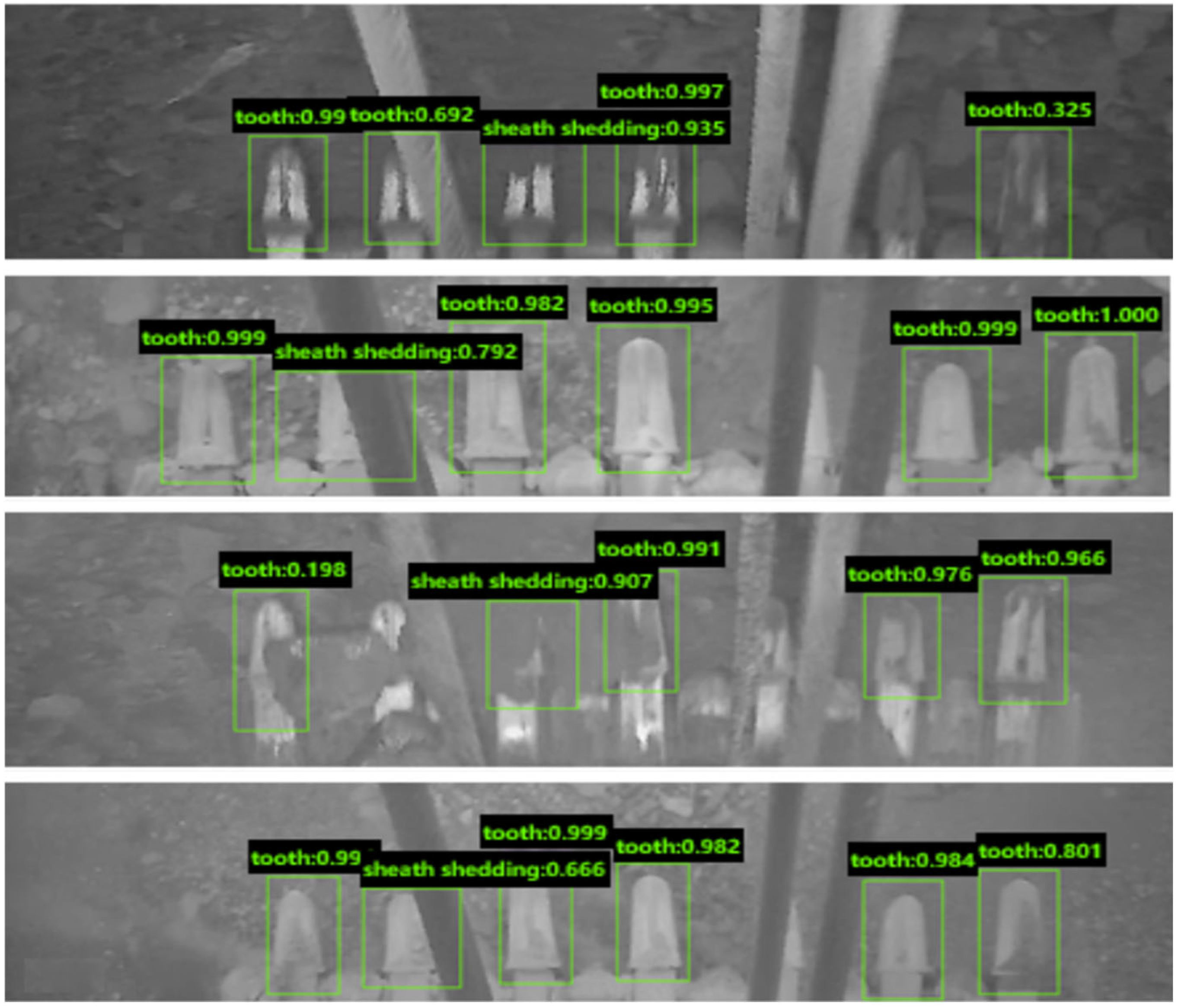

Figure 5 shows several examples of successful detections of different component shedding with high confidence.

Figure 6, in contrast, shows examples of low-entropy false alarms (shadows, reflections) that were correctly filtered out by our model, which the baseline CNN would have raised.

Note: The field images presented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, especially those in low-light or night-time conditions, were captured under actual production settings with limited illumination and environmental challenges. Their lower resolution and clarity reflect real-world operating conditions in open-pit mines, and were intentionally included to validate the robustness and practical applicability of the proposed IE-CNN model in harsh visual environments.

4.2.3. Results on Crusher Blockage Detection

For the crusher blockage task, the IE-CNN (using SSD MobileNetV1) achieved a mean average precision (mAP) of 0.92 and an average recall (AR) of 0.91, outperforming a Faster R-CNN benchmark. In a one-month field trial, the system triggered 96 valid alarms for major blockages with zero missed detections and only 5 false alarms.

4.3. Performance of the IE-DNN Evaluation Model

4.3.1. IE-DNN Model Experimental Setup

The IE-DNN model was designed to provide a monthly, objective performance assessment for key mining equipment. Multi-source operational data for a fleet of 32 trucks, 7 shovels, and 5 drills were collected throughout 2024. Data included metrics such as dispatch count, tonnage hauled, digging cycles, and drilling meterage. Data preprocessing involved the removal of outliers (identified via interquartile range) and imputation of missing values using linear interpolation for time-series consistency. All indicators were min–max normalized to a [0, 1] scale.

The proposed IE-DNN framework (combining autoencoder feature learning and entropy weighting) was compared against two conventional evaluation benchmarks:

Evaluation focused on the ranking consistency of equipment, computational cost, and the objectivity of the weighting process.

4.3.2. System-Level Evaluation Results

The model was deployed to generate monthly comprehensive performance scores for the entire OMIMCS throughout 2024, incorporating 12 key performance indicators (KPIs) across efficiency, cost, and stability dimensions. The entropy weighting method automatically assigned the highest weights to Unit Transport Cost (0.18), Truck Utilization (0.15), and Blending Scheme Entropy H(X) (0.12), aligning with operational priorities. The monthly scores, shown in

Table 3, successfully diagnosed performance dips, such as a low score in May, which correlated with a peak in equipment failure rates and system entropy.

The monthly comprehensive performance score (

) for the OMIMCS is calculated using the IE-DNN evaluation framework outlined in

Section 3.3. Specifically, multiple monthly KPIs are first normalized to a [0, 1] range. Their objective weights

are then determined via the entropy weighting method (Equations (9)–(12)). The final score is the weighted sum of these normalized KPI values (Equation (13)), linearly scaled to a 0–100 scale for intuitive interpretation, where 100 represents optimal performance.

The average inference time for generating the monthly system score was 0.8 s (Intel Xeon Gold 6226R), and the trained autoencoder contained approximately 50k parameters.

4.3.3. Equipment-Level Evaluation: Truck Fleet Case Study

To ensure reproducibility, we provide a step-by-step illustration using the truck fleet data from August 2024.

Step 1: DNN-based feature extraction.

A deep autoencoder is applied to the raw data (

Table 4) to obtain the refined feature matrix

(

Table 5).

Step 2: Normalization.

The features are normalized using min–max scaling to obtain

(

Table 6) using Equation (9).

Step 3: Entropy and weight calculation.

Applying Equations (10)–(12) to the normalized feature matrix yields the entropy

and objective weights

for each indicator, as shown in

Table 7.

Step 4: Comprehensive scoring.

Using Equation (13), the weighted sum score

is computed for each truck based on the original normalized data and the weights above. The scores are then scaled to [0, 100] to obtain the final ranking (

Table 8).

The resulting ranking, partially shown in

Table 8, provided clear, data-driven insights (only listing the top five and bottom five trucks). The top performer, Truck R10, achieved its rank by having the highest tonnage and the shortest average haul distance, making it the most cost-effective unit.

This example demonstrates how the entropy weighting method dynamically assigns higher weights to indicators with greater variability (e.g., Haul Distance), thereby ensuring that the evaluation reflects the actual discriminative power of each metric.

5. System Implementation and Industrial Validation

The theoretical models were engineered into a fully functional software system, the Open-pit Mine Intelligent Comprehensive Control System (OMIMCS), and deployed at the Qidashan Iron Mine of Ansteel Group.

Figure 7 illustrates the system’s data flow and model-driven architecture.

5.1. System Integration and Subsystems

The OMIMCS comprises several interconnected subsystems:

Intelligent ore blending management system: This system hosts the IE-LSTM model. It allows planners to configure parameters, run the optimization engine, and visualize the resulting blending plan and key performance indicators like predicted grade trends.

Intelligent truck dispatching system: This system executes the optimal blending plan in real time. It dynamically assigns trucks to shovels and crushers, tracking the actual vs. planned blend and making adjustments for unforeseen delays or failures.

Shovel bucket health monitoring system and crusher blockage detection system: These systems run the IE-CNN models for real-time video analytics, providing real-time video analytics and triggering immediate alarms in the control room upon detecting an anomaly.

Equipment performance evaluation system: This system uses the IE-DNN model to generate monthly equipment scorecards and dashboards, providing management with an objective basis for decisions.

5.2. KPIs and Economic Impact

The deployment of OMIMCS led to a step-change in the operational performance at Qidashan Mine. A comparison of system performance in 2024 with the 2022 baseline (pre-deployment) reveals significant improvements:

The resource utilization rate increased to 98.64%, minimizing resource waste.

The overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) showed a marked improvement across the fleet, ranging from 4.07% to 22.70%, indicating more productive and reliable operations.

Economic benefit: The cumulative direct economic benefits over a two-year period (2023–2024) were calculated to be RMB 43.3 million. These savings originated from multiple factors: reduced transportation costs, increased production throughput, decreased downtime due to proactive maintenance, and improved stability in product quality.

This industrial-scale validation confirms that the entropy–deep learning fusion framework is not only academically sound but also delivers substantial tangible value in a real-world production environment.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

A comprehensive and validated framework for intelligent open-pit mine management based on the fusion of information entropy and deep learning has been presented. The core models—IE-LSTM, IE-CNN, and IE-DNN—address the fundamental challenges of uncertainty, robustness, and objectivity that have limited the effectiveness of traditional and pure data-driven approaches.

The IE-LSTM model introduces a paradigm for decision-making that values robustness alongside economic efficiency. The IE-CNN model demonstrates a simple yet powerful mechanism for leveraging image content complexity to drastically reduce false alarms. The IE-DNN model establishes a fully objective and data-grounded methodology for performance evaluation.

The successful implementation of these models within the integrated OMIMCS platform at the Qidashan Iron Mine, and the subsequent demonstration of significant improvements in key performance indicators and economic returns, provides compelling evidence of the framework’s practical utility and transformative potential.

6.1. Limitations

While the proposed framework has shown strong performance in the context of Qidashan Iron Mine, several limitations should be acknowledged to guide future applications and research. First, the models were developed and validated primarily for an iron ore mining environment. This environment has specific geological and operational characteristics. Their generalizability to other mine types (e.g., coal, copper, or phosphate) or significantly different ore compositions remains to be tested, as variations in material properties, blending constraints, and detection targets may require architectural or parametric adjustments. Second, the performance of the deep learning components is dependent on the quantity and quality of labeled data, which may be scarce in newly operational or digitally immature mining sites. Finally, the current system assumes relatively stable connectivity and computational resources at the edge and cloud layers; performance in remote or infrastructure-limited settings may require further optimization for offline or low-bandwidth operation.

6.2. Future Work

Future research directions include the following:

Advanced uncertainty modeling: integrating Bayesian deep learning techniques could provide probabilistic forecasts and uncertainty intervals, offering a richer understanding of prediction confidence for decision-makers.

Reinforcement learning for adaptive control: replacing heuristic scheduling rules with Deep RL agents could enable the system to learn optimal dispatching and control policies directly from interaction with the environment, leading to even greater adaptability.

Cross-modal and federated learning: Incorporating data from other modalities could create a more holistic health-monitoring system. Federated learning could enable collaborative model training across multiple mines without sharing sensitive data, improving generalizability.

Sustainability integration: expanding the evaluation models to formally incorporate energy consumption, carbon emissions, and water usage metrics would align the system with the growing emphasis on sustainable and green mining practices.

In conclusion, the “entropy–deep learning fusion” framework represents a significant step forward in the journey towards fully intelligent mining operations. By enabling systems that are not only smart but also wise to the uncertainties they face, this work lays a foundation for a new generation of cognitive industrial management tools.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y. and J.Q.; software, J.Y.; validation, J.Q. and X.L.; formal analysis, A.S. and J.Q.; investigation, J.Q.; resources, X.L.; data curation, X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.Q.; visualization, X.L.; supervision, A.S. and X.L.; project administration, X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| IE-LSTM | Information Entropy–Long Short-Term Memory. |

| IE-CNN | Information Entropy–Convolutional Neural Network. |

| IE-DNN | Information Entropy–Deep Neural Network. |

| IoT | Internet of Things. |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence. |

| OMIMCS | Open-Pit Mine Intelligent Comprehensive Control System. |

| LP | Linear Programming. |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error. |

| OPMD-Net | Open-Pit Mine Detection Network. |

| LEM | Lightweight Extraction Module. |

| APH | Attention Prediction Head. |

| NAM | Normalized Attention Mechanism. |

| ROI | Region of Interest. |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator. |

| FPR | False-Positive Rate. |

References

- Arman, H.; Moradi, A.A. Intelligent Fleet Management Systems in Surface Mining: Status, Threats, and Opportunities. Min. Metall. Explor. 2023, 40, 2087–2106. [Google Scholar]

- Sushma, K.; Monika, C.; Khushboo, K.; Virendra, K.; Abhishek, C.; Kumar, C.S.; Mohan, P.G.; Kumar, M.S. Intelligent driving system at opencast mines during foggy weather. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2022, 36, 196–217. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Lu, C.W.; Jiang, S.; Lu, S.; Xiong, N.N. An Unmanned Intelligent Transportation Scheduling System for Open-pit Mine Vehicles Based on 5G and Big Data. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 135524–135539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Lian, M.J.; Lu, C.W.; Gu, Q.H.; Ruan, S.L.; Xie, X.C. Ensemble Prediction Algorithm of Anomaly Monitoring Based on Big Data Analysis Platform of Open-Pit Mine Slope. Complexity 2018, 2018, 1048756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padró, J.-C.; Carabassa, V.; Balagué, J.; Brotons, L.; Alcañiz, J.M.; Pons, X. Monitoring opencast mine restorations using Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) imagery. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 657, 1602–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.C.; Wang, H.; Cao, W.; Fu, Y.W.; Fu, Y.H.; He, L.M.; Bao, N.S. Extraction of Step-Feature Lines in Open-Pit Mines Based on UAV Point-Cloud Data. Sensors 2022, 22, 5706–5726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.X.; Liu, J.W.; Ming, J.; Sang, X.J. Geological hazard interpretation and hazard evaluation of open pit mines based on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle images. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2006, 012072–012081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, R.X.; Li, Q.S.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Z.G.; Ren, Z.C. Multidimensional spatial monitoring of open pit mine dust dispersion by unmanned aerial vehicle. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6815–6828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joan-Cristian, P.; Johnsson, C.; Pau, M.; Roger, R.; Maria, A.J.; Dèlia, S.; Vicenç, C. Drone-Based Identification of Erosive Processes in Open-Pit Mining Restored Areas. Land 2022, 11, 212–224. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, D.G.; Zhang, B.L.; Zhang, X.B.; Yin, L.; Man, X.C. Optimization methods on dynamic monitoring of mineral reserves for open pit mine based on UAV oblique photogrammetry. Measurement 2023, 207, 112364–112374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madziwa, L.; Pillalamarry, M.; Chatterjee, S. Integrating stochastic mine planning model with ARDL commodity price forecasting. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 104014–104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, L.C.; Dimitrakopoulos, R. Integrated Stochastic Underground Mine Planning with Long-Term Stockpiling: Method and Impacts of Using High-Order Sequential Simulations. Minerals 2024, 14, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, N.; Kundu, S. Fractional entropy-based modeling of suspended concentration distribution of type I and type II and sediment discharge in pipe and open-channel turbulent flows. Z. Fur Angew. Math. Und Phys. 2023, 74, 030001–030047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Pan, H.; Li, X.W.; Ma, S.B.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, K.B. An Information Entropy-Based Modeling Method for the Measurement System. Entropy 2019, 21, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, S.T.; Cheng, Y.B.; Li, Z.Y.; Wang, J.X.; Li, H.Y.; Zhang, C.W. Advanced Deep Learning Techniques for Battery Thermal Management in New Energy Vehicles. Energies 2024, 17, 4132–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.T.; Li, S.W.; Su, X.T.; Li, Y.; Huang, L.Y.; Tang, W.D.; Zhang, Y.C.; Dong, M. Application of Advanced Deep Learning Models for Efficient Apple Defect Detection and Quality Grading in Agricultural Production. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1098–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Jin, Q.; Zhou, G.H.; Wang, R.; Wang, Z.W.; Liu, D.; Cai, K.Z.; Xu, B.C. Advanced deep learning algorithms in food quality and authenticity. Trac-Trends Anal. Chem. 2025, 191, 118374–118392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.X.; An, S.S.; Jiang, H.Y.; Zheng, B.W.; Tang, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, H.L. Advanced deep learning approaches in metasurface modeling and design: A review. Prog. Quantum Electron. 2025, 99, 100554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.T. Study on Non-Coal Underground Mine Safety Monitoring Early-Warning & Decision Platform Based on IoT. Ph.D. Thesis, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.Z. Study on Interpretation of Complex Geological Body Based on Synergy of Multi-Sources Satellite Remote Sensing Data. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Research Approach for Multiple Sequence of Three-Dimensional Models of Mine Based on Semantic Scale and Uncertain Analysis on Geology Modeling. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.Q. An Entropy Based Comprehensive Evaluation on Green Coal Mine. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Geosciences Beijing, Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ramazan, S.; Dimitrakopoulos, R. Production scheduling with uncertain supply: A new solution to the open pit mining problem. Optim. Eng. 2013, 14, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamghari, A.; Dimitrakopoulos, R. A diversified Tabu search approach for the open-pit mine production scheduling problem with metal uncertainty. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 222, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, R.C.; Dimitrakopoulos, R. Global optimization of open pit mining complexes with uncertainty. Appl. Soft Comput. 2016, 40, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benndorf, J.; Dimitrakopoulos, R. Stochastic long-term production scheduling of iron ore deposits: Integrating joint multi-element geological uncertainty. J. Min. Sci. 2013, 49, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, W.B.; Newman, A.M. Tailored Lagrangian Relaxation for the open pit block sequencing problem. Ann. Oper. Res. 2014, 222, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, N.; Dumitrescu, I.; Froyland, G.; Gleixner, A.M. LP-based disaggregation approaches to solving the open pit mining production scheduling problem with block processing selectivity. Comput. Oper. Res. 2009, 36, 1064–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishvan, M.S.; Sattarvand, J. Long term production planning of open pit mines by ant colony optimization. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 240, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, L.; Dimitrakopoulos, R. Stochastic mine production scheduling with multiple processes: Application at Escondida Norte, Chile. J. Min. Sci. 2013, 49, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumral, M. Optimizing ore–waste discrimination and block sequencing through simulated annealing. Appl. Soft Comput. 2013, 13, 3737–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Niemann-Delius, C. Production Scheduling of Open Pit Mines Using Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm. Adv. Oper. Res. 2014, 2014, 208502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, R.; Dimitrakopoulos, R. Algorithmic integration of geological uncertainty in pushback designs for complex multiprocess open pit mines. Min. Technol. 2013, 122, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jélvez, E.; Morales, N.; Nancel-Penard, P.; Peypouquet, J.; Reyes, P. Aggregation heuristic for the open-pit block scheduling problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 249, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, S.-O.; Sattarvand, J. Integrating geological uncertainty in long-term open pit mine production planning by ant colony optimization. Comput. Geosci. 2016, 87, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaboga, D.; Basturk, B. A powerful and efficient algorithm for numerical function optimization: Artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm. J. Glob. Optim. 2007, 39, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B. Research on WNN modeling for gold price forecasting based on improved artificial bee colony algorithm. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2014, 2014, 270658–270667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafrasteh, B.; Fathianpour, N. A hybrid simultaneous perturbation artificial bee colony and back-propagation algorithm for training a local linear radial basis neural network on ore grade estimation. Neurocomputing 2017, 235, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Xie, X.; Zou, Y.; Kang, Q.; Liu, Q. Research on Comprehensive Evaluation Model of a Truck Dispatching System in Open-Pit Mine. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9062–9077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahumada, G.I.; Riveros, E.; Herzog, O. An Agent-based System for Truck Dispatching in Open-pit Mines. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART), Valletta, Malta, 22–24 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ahumada, G.I.; Diaz Pinto, J.; Herzog, O. A Dynamic Scheduling Multiagent System for Truck Dispatching in Open-Pit Mines; Springer International Publishing Press: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, B.; Tian, T.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Peng, Y. A Dynamic Dispatching Method for Large-Scale Interbay Material Handling Systems of Semiconductor FAB. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13882–13901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, D.; Sari, Y.A.; Kealey, R.; Zhang, Q. Reinforcement Learning-Based Fleet Dispatching for Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction in Open-Pit Mining Operations. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 188, 106664–106678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; Hou, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Yuan, W. Open-Pit Mine Truck Dispatching System Based on Dynamic Ore Blending Decisions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3399–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.L.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Deng, F.; Mu, Y.S.; Zhong, Y.; Jiao, D.M. Detection of Bubble Defects on Tire Surface Based on Line Laser and Machine Vision. Processes 2022, 10, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, B.; Wu, J.C.; Zhang, S.Y.; Lv, C.X.; Li, L. Stress-Crack detection in maize kernels based on machine vision. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 194, 106795–106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.F. Application of Bucket Tooth Monitoring System Based on Image Recognition in Excavator. Mech. Manag. Dev. 2018, 33, 73–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, K. Research on Monitoring Technology of Tooth Detection Based on Deep Learning. Ph.D. Thesis, Liaoning Technical University, Fuxin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.H.; Dong, Z.; Liu, J.Q. Research of Mine Conveyor Belt Deviation Detection System Based on Machine Vision. J. Min. Sci. 2021, 57, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N.; Xuan-Nam, B.; Quang-Hieu, T.; Dinh-An, N.; Le-Thi-Thu, H.; Qui-Thao, L.; Le-Thi-Huong, G. Predicting Blast-Induced Ground Vibration in Open-Pit Mines Using Different Nature-Inspired Optimization Algorithms and Deep Neural Network. Nat. Resour. Res. 2021, 30, 4695–4717. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, C.; Huang, G.; Yuan, Q.; Xu, K.; Zhang, W. Detection Method of Crushing Mouth Loose Material Blockage Based on SSD Algorithm. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14386–14401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |