Ultrasound Training in the Digital Age: Insights from a Multidimensional Needs Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Questionnaire Development

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

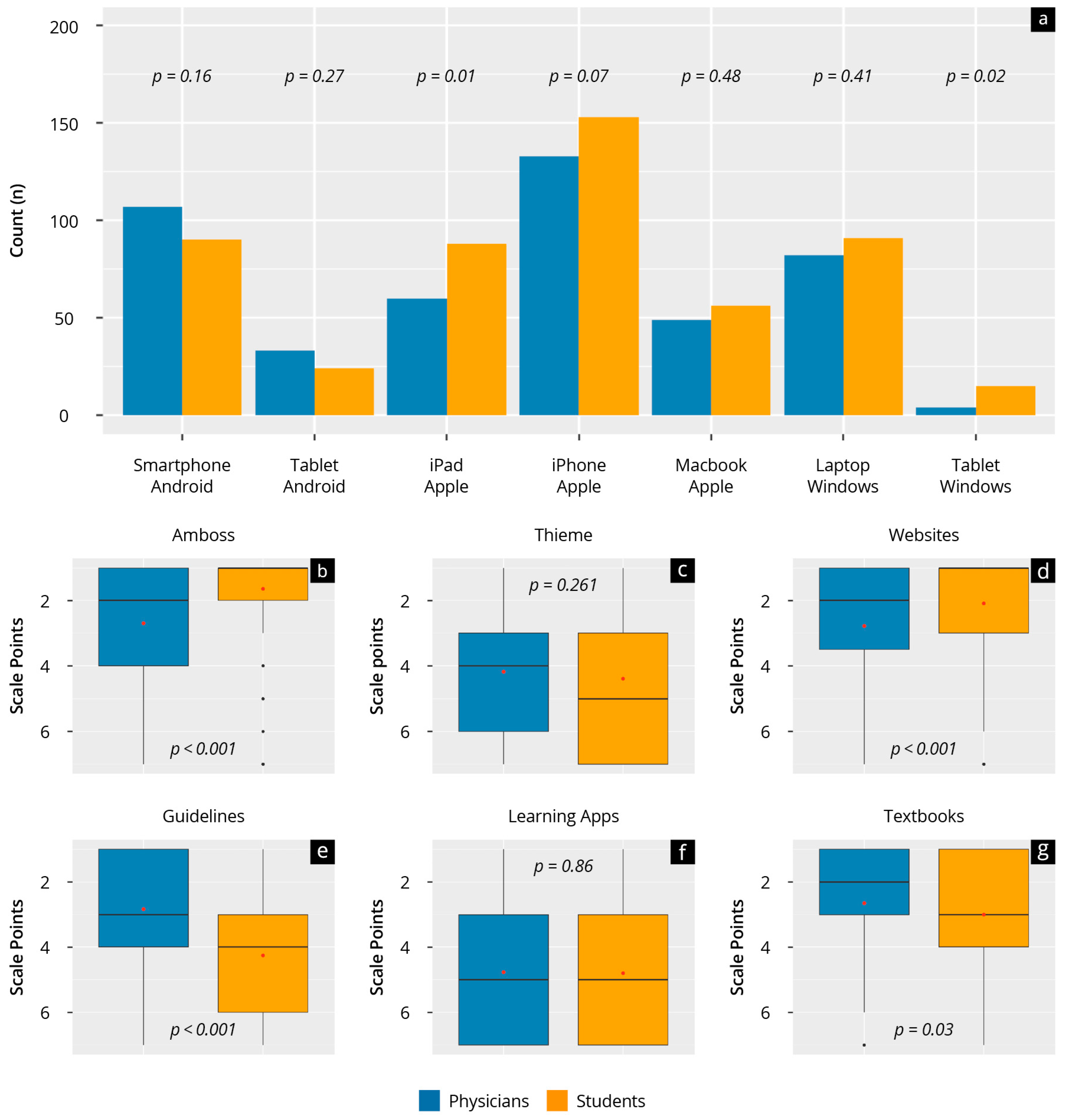

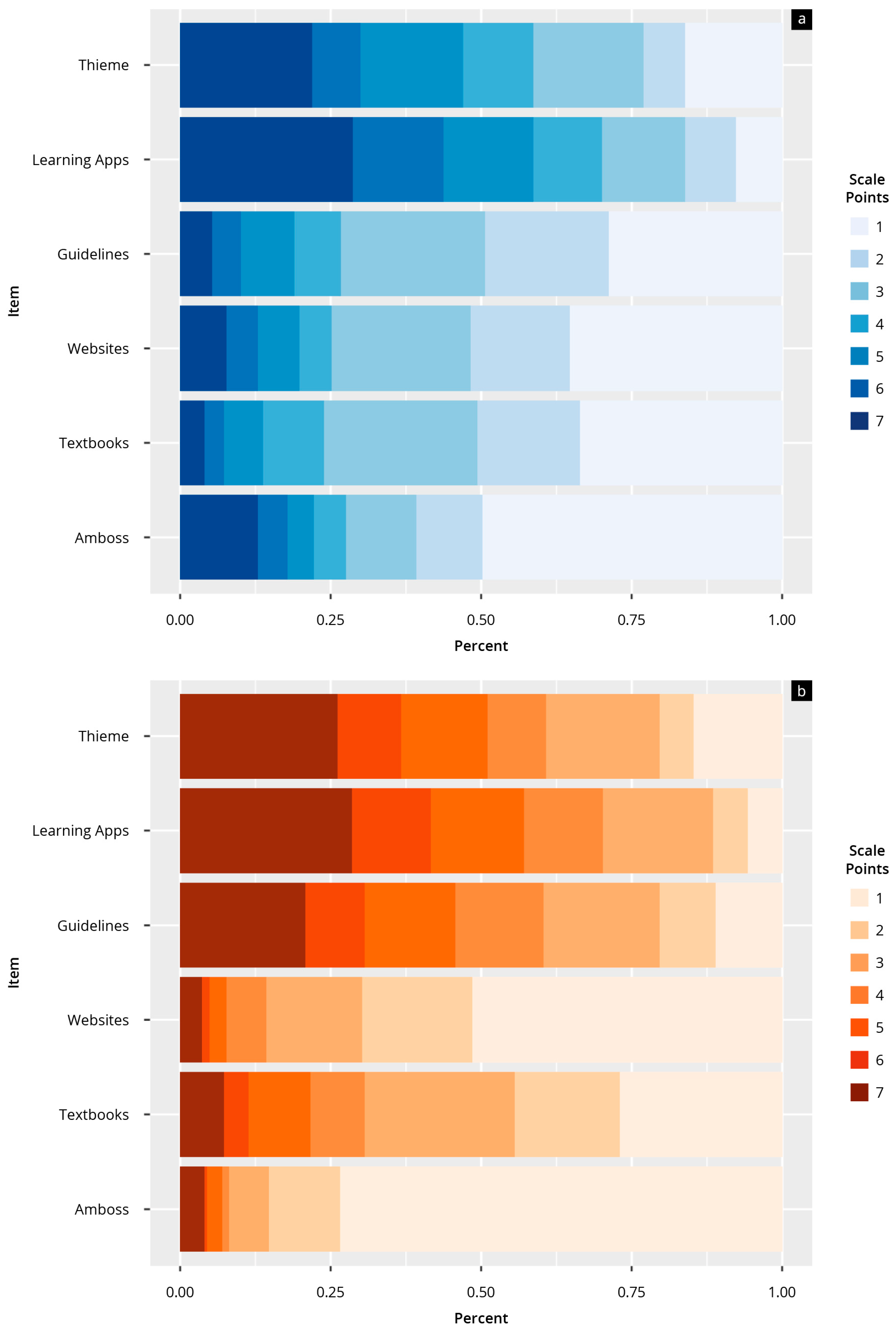

3.1. Structural Needs Analysis (Questionnaire 1)

3.1.1. Group Characterisation

3.1.2. Results of the Structural Needs Analysis

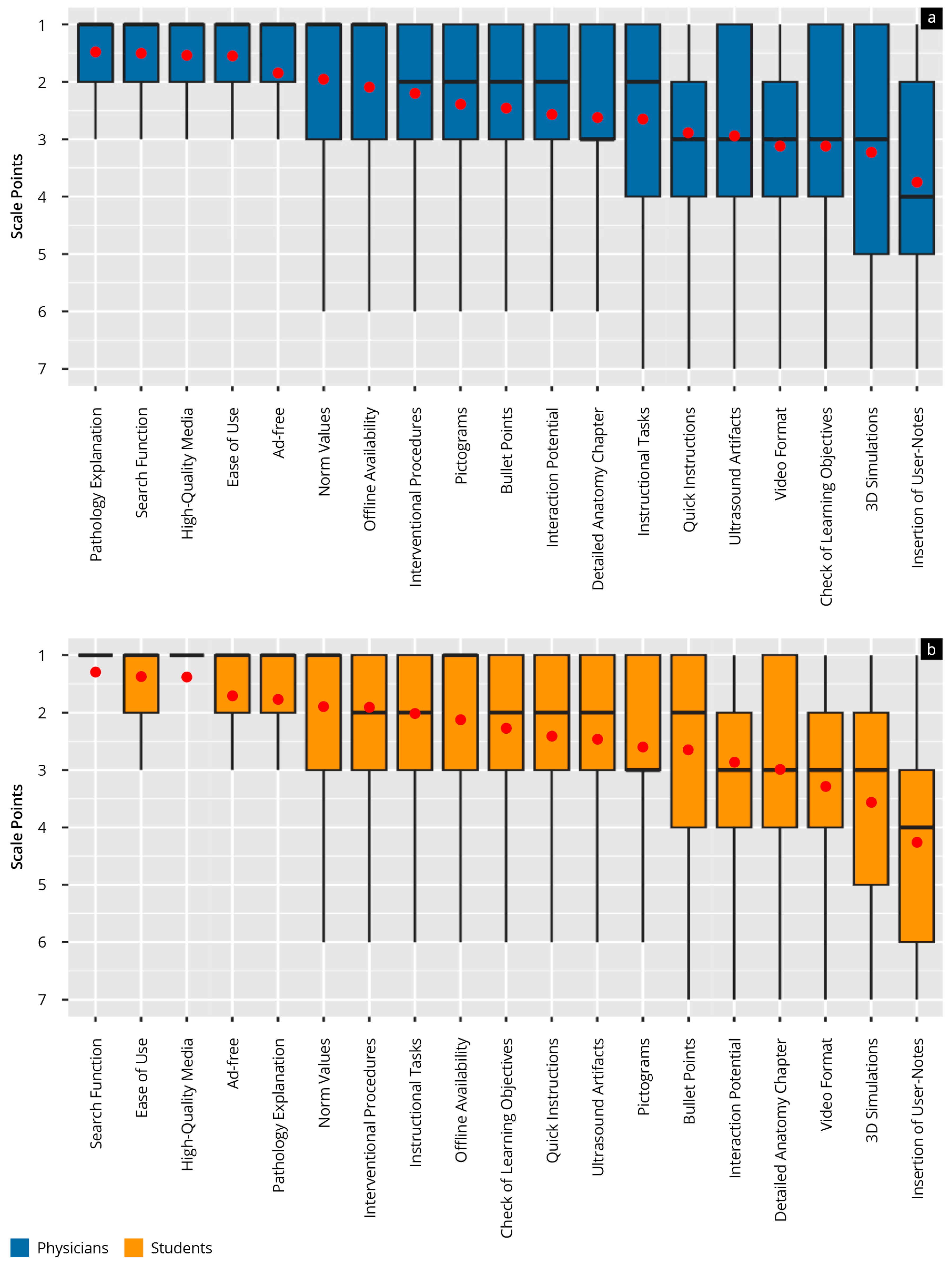

3.2. User-Centred Needs Analysis (Questionnaire 2)

3.2.1. Group Characterisation

3.2.2. Results of the User-Centred Needs Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Relevance and Key Findings

4.2. Digital Ultrasound Education: A Long-Term Demand

4.3. Offline Accessibility: A Critical Feature

4.4. Different Use of Learning Resources: Age and Experience Matter

4.5. Mobile Devices and Their Role in Learning

4.6. Minimal Differences in Needs Between Groups

4.7. Emerging Technologies and Future Perspectives

4.8. Sustainability and Resource Considerations

4.9. Strengths and Limitations

4.10. Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dietrich, C.F.; Bolondi, L.; Duck, F.; Evans, D.H.; Ewertsen, C.; Fraser, A.G.; Gilja, O.H.; Jenssen, C.; Merz, E.; Nolsoe, C.; et al. History of Ultrasound in Medicine from its birth to date (2022), on occasion of the 50 Years Anniversary of EFSUMB. A publication of the European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound In Medicine and Biology (EFSUMB), designed to record the historical development of medical ultrasound. Med. Ultrason. 2022, 24, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsburg, A.S.; Liddy, Z.; Khazaneh, P.T.; May, S.; Pervaiz, F. A survey of barriers and facilitators to ultrasound use in low- and middle-income countries. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Macho, J.; Aro, T.; Bruckner, I.; Cogliati, C.; Gilja, O.H.; Gurghean, A.; Karlafti, E.; Krsek, M.; Monhart, Z.; Müller-Marbach, A.; et al. Point-of-care ultrasound in internal medicine: A position paper by the ultrasound working group of the European federation of internal medicine. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 73, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, D.; Badea, R.; Poanta, L.; Dumitrascu, D.L.; Buzoianu, A.D.; Mircea, P.-A. The use of ultrasonography in learning clinical examination—A pilot study involving third year medical students. Med. Ultrason. 2012, 14, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahner, D.P.; Goldman, E.; Way, D.; Royall, N.A.; Liu, Y.T. The State of Ultrasound Education in U.S. Medical Schools: Results of a National Survey. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1681–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neubauer, R.; Bauer, C.J.; Dietrich, C.F.; Strizek, B.; Schäfer, V.S.; Recker, F. Evidence-based Ultrasound Education?—A Systematic Literature Review of Undergraduate Ultrasound Training Studies. Ultrasound Int. Open 2024, 10, a22750702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppmann, R.A.; Mladenovic, J.; Melniker, L.; Badea, R.; Blaivas, M.; Montorfano, M.; Abuhamad, A.; Noble, V.; Hussain, A.; Prosen, G.; et al. International consensus conference recommendations on ultrasound education for undergraduate medical students. Ultrasound J. 2022, 14, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantisani, V.; Dietrich, C.; Badea, R.; Dudea, S.; Prosch, H.; Cerezo, E.; Nuernberg, D.; Serra, A.; Sidhu, P.; Radzina, M.; et al. EFSUMB Statement on Medical Student Education in Ultrasound [long version]. Ultrasound Int. Open 2016, 2, E2–E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundiya, O.; Rahman, T.J.; Valnarov-Boulter, I.; Young, T.M. Looking Back on Digital Medical Education Over the Last 25 Years and Looking to the Future: Narrative Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e60312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, A.W.K.; Parvanov, E.D.; Hribersek, M.; Eibensteiner, F.; Klager, E.; Kletecka-Pulker, M.; Rössler, B.; Schebesta, K.; Willschke, H.; Atanasov, A.G.; et al. Digital Teaching in Medical Education: Scientific Literature Landscape Review. JMIR Med. Educ. 2022, 8, e32747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGee, R.G.; Wark, S.; Mwangi, F.; Drovandi, A.; Alele, F.; Malau-Aduli, B.S.; The, A.C. Digital learning of clinical skills and its impact on medical students’ academic performance: A systematic review. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, V.; Strobel, D.; Karlas, T. Digital Training Formats in Ultrasound Diagnostics for physicians: What options are available and how can they be successfully integrated into current DEGUM certified course concepts? Ultraschall Med. 2022, 43, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, J.M.; Recker, F.; Horn, L.; Kuenzel, J.; Dirks, K.; Ille, C.; Buggenhagen, H.; Börner, N.; Weimer, A.M.; Vieth, T.; et al. Insights Into Modern Undergraduate Ultrasound Education: Prospective Comparison of Digital and Analog Teaching Resources in a Flipped Classroom Concept—The DIvAN Study. Ultrasound Int. Open 2024, 10, a23899410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lien, W.C.; Lin, P.; Chang, C.H.; Wu, M.C.; Wu, C.Y. The effect of e-learning on point-of-care ultrasound education in novices. Med. Educ. Online 2023, 28, 2152522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandran, V.P.; Balakrishnan, A.; Rashid, M.; Pai Kulyadi, G.; Khan, S.; Devi, E.S.; Nair, S.; Thunga, G. Mobile applications in medical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höhne, E.; Recker, F.; Schmok, E.; Brossart, P.; Raupach, T.; Schäfer, V.S. Conception and Feasibility of a Digital Tele-Guided Abdomen, Thorax, and Thyroid Gland Ultrasound Course for Medical Students (TELUS study). Ultraschall Med. 2021, 44, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, J.M.; Sprengart, F.M.; Vieth, T.; Göbel, S.; Dionysopoulou, A.; Krüger, R.; Beer, J.; Weimer, A.M.; Buggenhagen, H.; Kloeckner, R.; et al. Simulator training in focus assessed transthoracic echocardiography (FATE) for undergraduate medical students: Results from the FateSim randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppert, J.; Krüger, R.; Göbel, S.; Wolfhard, S.; Lorenz, L.-A.; Weimer, A.M.; Kloeckner, R.; Waezsada, E.; Buggenhagen, H.; Weinmann-Menke, J.; et al. The effectiveness of e-learning in focused cardiac ultrasound training: A prospective controlled study. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altersberger, M.; Pavelka, P.; Sachs, A.; Weber, M.; Wagner-Menghin, M.; Prosch, H. Student Perceptions of Instructional Ultrasound Videos as Preparation for a Practical Assessment. Ultrasound Int. Open 2019, 5, E81–E88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J. FIELD: A program for simulating ultrasound systems. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 1996, 34, 351–352. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, D. Make the most of MUST, an open-source Matlab UltraSound Toolbox. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Xi’an, China, 11–16 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, J.G.; Mintzer, M.J.; Leipzig, R.M. The impact of E-learning in medical education. Acad. Med. 2006, 81, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, J.; Recker, F.; Krüger, R.; Müller, L.; Buggenhagen, H.; Kurz, S.; Weimer, A.; Lorenz, L.-A.; Kloeckner, R.; Ruppert, J.; et al. The Effectiveness of Digital vs. Analogue Teaching Resources in a Flipped Classroom for Undergraduate Focus Cardiac Ultrasound Training: A Prospective, Randomised, Controlled Single-Centre Study. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautz, S.C.; Hoffmann, M.; Exadaktylos, A.K.; Hautz, W.E.; Sauter, T.C. Digital competencies in medical education in Switzerland: An overview of the current situation. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2020, 37, Doc62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, A.; Russell, F.M.; Zahn, G.; Zakeri, B.; Motzkus, C.; Wallach, P.M.; Ferre, R.M. Point-of-Care Ultrasound Education During a Pandemic: From Webinar to Progressive Dinner-Style Bedside Learning. Cureus 2022, 14, e25141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, L.; Rashid, A.M.; Ouyang, S. The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) in Higher Education: A Systematic Review. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241229570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niegemann, H.M.; Niegemann, L. IzELA: Ein Instructional Design basiertes Evaluationstool für Lern-Apps. In Digitalisierung und Bildung; Ladel, S., Knopf, J., Weinberger, A., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; pp. 159–175. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, E.C.N.; Dine, C.J.; Kogan, J.R. Preclerkship Medical Students’ Use of Third-Party Learning Resources. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2345971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Doherty, D.; Dromey, M.; Lougheed, J.; Hannigan, A.; Last, J.; McGrath, D. Barriers and solutions to online learning in medical education—An integrative review. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, K.; Jones, L. A systematic review of the factors—Enablers and barriers—Affecting e-learning in health sciences education. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, E.; Goebel, S.; Couné, B. Bedarfsanalyse—Palliative Care Basics; Universität Freiburg, Wissenschaftliche Weiterbildung: Freiburg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, M.C.; Bevan, N. User Requirements Analysis A Review of Supporting Methods. In IFIP—The International Federation for Information Processing; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lemke, C.; Kirchner, K.; Brenner, B. Es ist Vorlesung und Keiner Geht Hin: Nutzerzentrierte Bedürfnisanalyse für Eine Digitale Lehr-und Lernplattform; Gesellschaft für Informatik: Hamburg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Likert, R.A. A technique for developing suppression tests. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1952, 12, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Garrido, N.; Ramos-Sosa, M.P.; Accerenzi, M.; Brañas-Garza, P. Continuous and binary sets of responses differ in the field. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, A.M.; Berthold, R.; Schamberger, C.; Vieth, T.; Balser, G.; Berthold, S.; Stein, S.; Müller, L.; Merkel, D.; Recker, F.; et al. Digital Transformation in Musculoskeletal Ultrasound: Acceptability of Blended Learning. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourkami-Tutdibi, N.; Hofer, M.; Zemlin, M.; Abdul-Khaliq, H.; Tutdibi, E. TEACHING MUST GO ON: Flexibility and advantages of peer assisted learning during the COVID-19 pandemic for undergraduate medical ultrasound education—Perspective from the “sonoBYstudents” ultrasound group. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2021, 38, Doc5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daum, N.; Blaivas, M.; Goudie, A.; Hoffmann, B.; Jenssen, C.; Neubauer, R.; Recker, F.; Moga, T.V.; Zervides, C.; Dietrich, C.F. Student ultrasound education, current view and controversies. Role of Artificial Intelligence, Virtual Reality and telemedicine. Ultrasound J. 2024, 16, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.A.; Artino, A.R., Jr. Motivation to learn: An overview of contemporary theories. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahnken, A.H.; Baumann, M.; Meister, M.; Schmitt, V.; Fischer, M.R. Blended learning in radiology: Is self-determined learning really more effective? Eur. J. Radiol. 2011, 78, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyaw, B.M.; Posadzki, P.; Dunleavy, G.; Semwal, M.; Divakar, U.; Hervatis, V.; Tudor Car, L. Offline Digital Education for Medical Students: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by the Digital Health Education Collaboration. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakre, C.A.; Pencille, L.J.; Sorensen, K.J.; Shellum, J.L.; Del Fiol, G.; Maggio, L.A.; Prokop, L.J.; Cook, D.A. Electronic Knowledge Resources and Point-of-Care Learning: A Scoping Review. Acad. Med. 2018, 93, S60–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.; Salter, A.; Bennett, L.; Seilhamer, R.; Chen, B. Changing Mobile Learning Practices: A Multiyear Study 2012–2016. Educ. Rev. 2018. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2018/4/changing-mobile-learning-practices-a-multiyear-study-2012-2016 (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Robert, J. EDUCAUSE QuickPoll Results: Flexibility and Equity for Student Success. Educ. Rev. 2021. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/766f329b2c76b4be35493cb091292c4c/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=7213897# (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D. The use of mobile learning in higher education: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2018, 123, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Designentscheidungen: Das DO-ID-Modell. In Kompendium multimediales Lernen; Niegemann, H.M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, I.; Bhattacharya, A.; Wong, S.H.; Singh, H.R.; Agarwal, A. Role of Three-Dimensional Visualization Modalities in Medical Education. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 760363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, R. Multimedia Learning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, W.C. Overview and Evolution of the ADDIE Training System. Adv. Dev. Human Resour. 2006, 8, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, P.M.; Todsen, T.; Subhi, Y.; Graumann, O.; Nolsøe, C.P.; Tolsgaard, M.G. Cost-Effectiveness of Mobile App-Guided Training in Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (eFAST): A Randomized Trial. Ultraschall Med. 2017, 38, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Huang, Q.; Huang, X.; Wang, H.; Li, M.; Lin, K.-J.; Chang, Y. XKT: Toward Explainable Knowledge Tracing Model With Cognitive Learning Theories for Questions of Multiple Knowledge Concepts. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 36, 7308–7325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, D.; Niu, B.; Yang, H.; Huang, Q.; Jiang, L.; Liu, H. Smooth Path Planning and Dynamic Contact Force Regulation for Robotic Ultrasound Scanning. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 10570–10577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Item | Subitem | Scale Levels |

|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire 1 | ||

| Attitude | Ultrasound in Medical Studies | Likert format 1–7 |

| Ultrasound in Compulsory Teaching | ||

| Digitalisation | Integration of Digital Learning Media in Ultrasound Teaching | |

| Development of Digital Learning Media | ||

| Current Use of Digital Learning Media in Clinical Practice | ||

| Case Studies/ Case-Based Learning | Integration of Case Studies in Ultrasound Teaching | Likert format 1–7 |

| Pure Case-Based Learning | ||

| Questionnaire 2 | ||

| Format und Features | Search Function | Likert format 1–7 |

| Insertion of User Notes | ||

| Norm Values | ||

| Multimedia Design | High-Quality Media | Likert format 1–7 |

| Bullet Points | ||

| Video Format | ||

| 3D Simulations | ||

| Pictograms | ||

| Content Structuring | Detailed Anatomy Chapter | Likert format 1–7 |

| Interventional Procedures | ||

| Ultrasound Artefacts chapter | ||

| Pathology Explanation | ||

| Learning Objective Checks | ||

| Instructional Tasks | ||

| Interactivity | Interaction Potential | Likert format 1–7 |

| Usability | Ease of Use | Likert format 1–7 |

| Quick Instructions | ||

| Context of Use | Offline Availability | |

| Financing | Ad-Free | |

| Use of Digital Devices | Android Smartphone | Dichotomous (“Yes”; “No”) |

| Apple iPhone | ||

| Android Tablet | ||

| Windows Tablet | ||

| Apple iPad | ||

| Windows Laptop | ||

| Apple MacBook | ||

| Use of Educational Media | AMBOSS | Dichotomous (“Yes”; “No”) |

| Thieme | ||

| Websites | ||

| Guidelines | ||

| Learning Apps | ||

| Textbooks | ||

| Baseline Characteristics | Student or Physician | |

| Item | Whole Group | Students | Physicians | p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean ± SD | Median | n | Mean ± SD | Median | N | Mean ± SD | Median | ||

| Ultrasound in Medical Studies | 2987 | 1.28 (0.76) | 1 | 2576 | 1.18 (0.58) | 1 | 411 | 1.89 (1.31) | 1 | <0.001 |

| Ultrasound in Compulsory Teaching | 2820 | 1.37 (0.85) | 1 | 2574 | 1.31 (0.76) | 1 | 246 | 1.93 (1.36) | 1 | <0.001 |

| Current Use of Digital Learning Media in Clinical Practice | 2538 | 2.07 (1.30) | 2 | 2140 | 1.99 (1.21) | 2 | 398 | 2.50 (1.60) | 2 | <0.001 |

| Integration of Digital Learning Media in Ultrasound Teaching | 2564 | 1.65 (1.00) | 1 | 2153 | 1.65 (1.02) | 1 | 411 | 1.66 (0.91) | 1 | 0.152 |

| Development of Digital Learning Media | 2505 | 1.70 (1.07) | 1 | 2155 | 1.72 (1.09) | 1 | 350 | 1.59 (0.95) | 1 | 0.120 |

| Integration of Case Studies in Ultrasound Teaching | 954 | 1.43 (0.83) | 1 | 574 | 1.45 (0.84) | 1 | 380 | 1.41 (0.82) | 1 | 0.514 |

| Pure Case-Based Learning | 568 | 3.43 (1.90) | 3 | 354 | 3.66 (1.98) | 4 | 214 | 3.05 (1.71) | 3 | <0.001 |

| Whole Group | Physicians | Students | p-Value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | Median | |||

| Format and Features | Search Function | 1.40 | 0.82 | 1 | 1.50 | 0.93 | 1 | 1.29 | 0.69 | 1 | 0.005 |

| Insertion of User-Notes | 3.65 | 1.89 | 4 | 3.75 | 1.88 | 4 | 3.55 | 1.89 | 3 | 0.236 | |

| Norm Values | 1.92 | 1.20 | 1 | 1.95 | 1.22 | 1 | 1.89 | 1.18 | 1 | 0.594 | |

| Multimedia Design | High-Quality Media | 1.47 | 0.87 | 1 | 1.54 | 0.92 | 1 | 1.39 | 0.82 | 1 | 0.062 |

| Bullet Points | 2.55 | 1.64 | 2 | 2.46 | 1.54 | 2 | 2.64 | 1.74 | 2 | 0.237 | |

| Video Format | 3.19 | 1.81 | 3 | 3.15 | 1.78 | 3 | 3.22 | 1.84 | 3 | 0.684 | |

| 3D Simulations | 3.25 | 1.73 | 3 | 3.21 | 1.82 | 3 | 3.30 | 1.64 | 3 | 0.576 | |

| Pictograms | 2.49 | 1.39 | 2 | 2.39 | 1.42 | 2 | 2.59 | 1.34 | 3 | 0.111 | |

| Content Structuring | Detailed Anatomy Chapter | 2.75 | 1.42 | 3 | 2.62 | 1.35 | 3 | 2.87 | 1.47 | 3 | 0.054 |

| Interventional Procedures | 2.06 | 1.32 | 2 | 2.20 | 1.50 | 2 | 1.92 | 1.10 | 2 | 0.021 | |

| Ultrasound Artefacts | 2.68 | 1.50 | 3 | 2.89 | 1.51 | 3 | 2.48 | 1.47 | 2 | 0.002 | |

| Pathology Explanation | 1.63 | 1.05 | 1 | 1.48 | 0.90 | 1 | 1.78 | 1.17 | 1 | 0.001 | |

| Check of Learning Objectives | 2.71 | 1.63 | 3 | 3.12 | 1.74 | 3 | 2.29 | 1.40 | 2 | <0.001 | |

| Instructional Tasks | 2.35 | 1.41 | 2 | 2.66 | 1.51 | 2 | 2.04 | 1.22 | 2 | <0.001 | |

| Interactivity | Interaction Potential | 2.62 | 1.50 | 3 | 2.57 | 1.48 | 2 | 2.67 | 1.53 | 3 | 0.467 |

| Usability | Ease of Use | 1.46 | 0.85 | 1 | 1.55 | 0.99 | 1 | 1.37 | 0.69 | 1 | 0.017 |

| Quick Instructions | 2.68 | 1.53 | 3 | 2.94 | 1.59 | 3 | 2.41 | 1.43 | 2 | <0.001 | |

| Context of Use | Offline Availability | 2.11 | 1.53 | 1 | 2.09 | 1.50 | 1 | 2.12 | 1.55 | 1 | 0.809 |

| Financing | Ad-free | 1.78 | 1.37 | 1 | 1.85 | 1.45 | 1 | 1.71 | 1.29 | 1 | 0.259 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Weimer, J.M.; Recker, F.; Vieth, T.; Kuon, S.; Weimer, A.M.; Menke, J.W.; Buggenhagen, H.; Künzel, J.; Rink, M.; Merkel, D.; et al. Ultrasound Training in the Digital Age: Insights from a Multidimensional Needs Assessment. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010071

Weimer JM, Recker F, Vieth T, Kuon S, Weimer AM, Menke JW, Buggenhagen H, Künzel J, Rink M, Merkel D, et al. Ultrasound Training in the Digital Age: Insights from a Multidimensional Needs Assessment. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010071

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeimer, Johannes Matthias, Florian Recker, Thomas Vieth, Samuel Kuon, Andreas Michael Weimer, Julia Weinmann Menke, Holger Buggenhagen, Julian Künzel, Maximilian Rink, Daniel Merkel, and et al. 2026. "Ultrasound Training in the Digital Age: Insights from a Multidimensional Needs Assessment" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010071

APA StyleWeimer, J. M., Recker, F., Vieth, T., Kuon, S., Weimer, A. M., Menke, J. W., Buggenhagen, H., Künzel, J., Rink, M., Merkel, D., Müller, L., Pillong, L., & Weimer, L. (2026). Ultrasound Training in the Digital Age: Insights from a Multidimensional Needs Assessment. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010071