Identifying Biodiversity-Based Indicators for Regulating Ecosystem Services in Constructed Wetlands

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

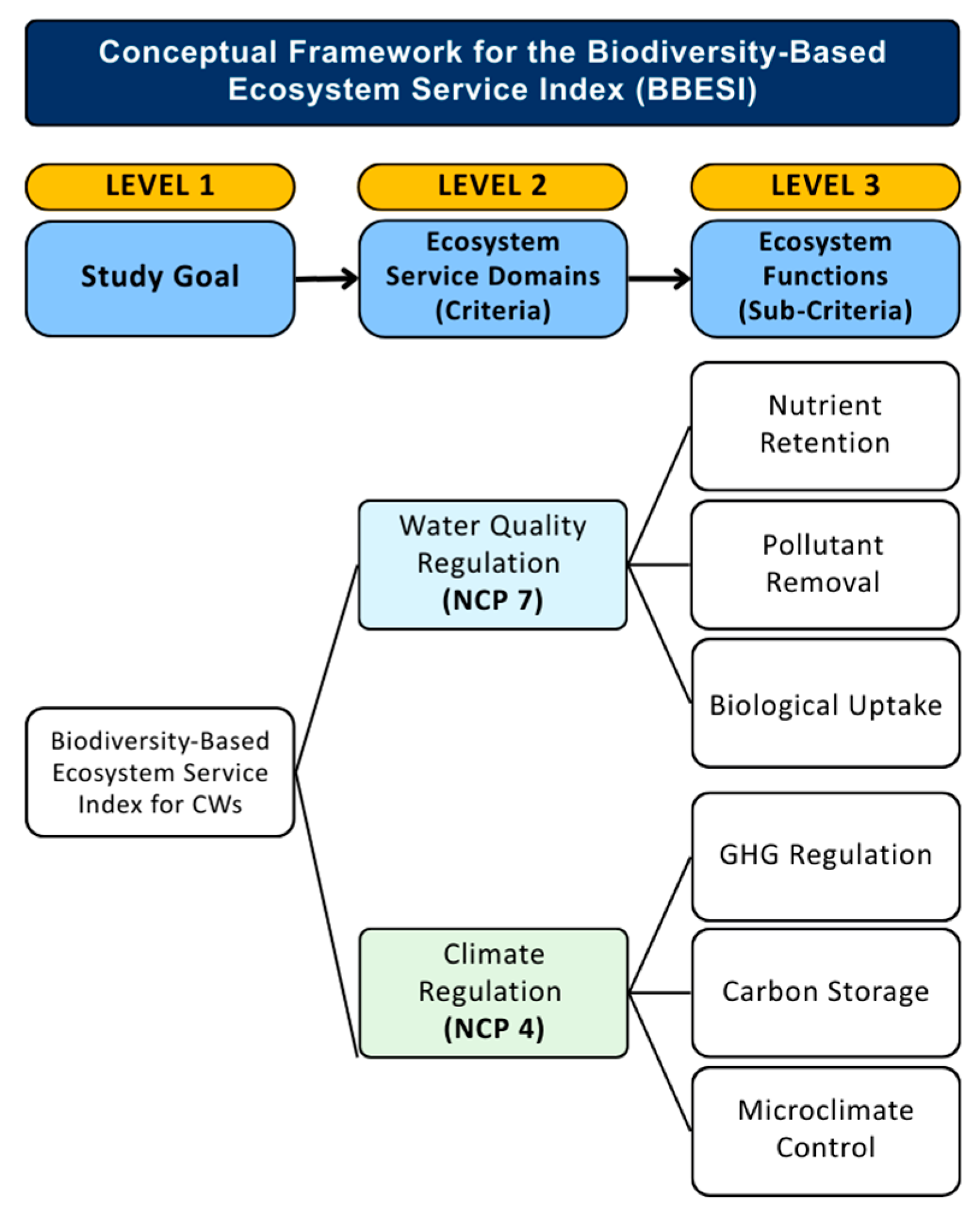

2.1. Conceptual Framework and Hierarchical Structure

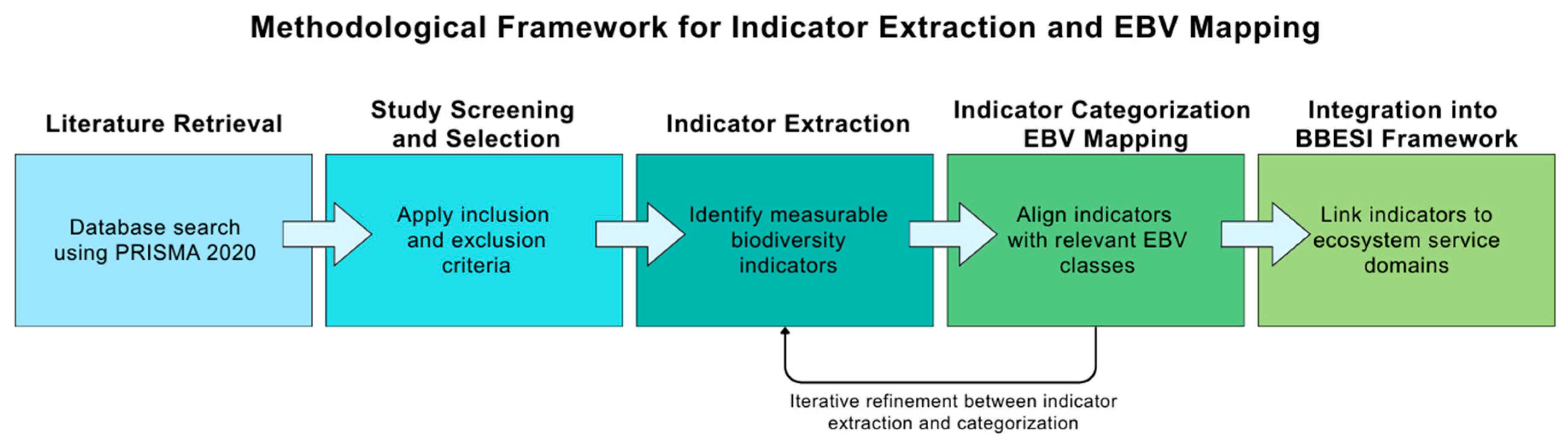

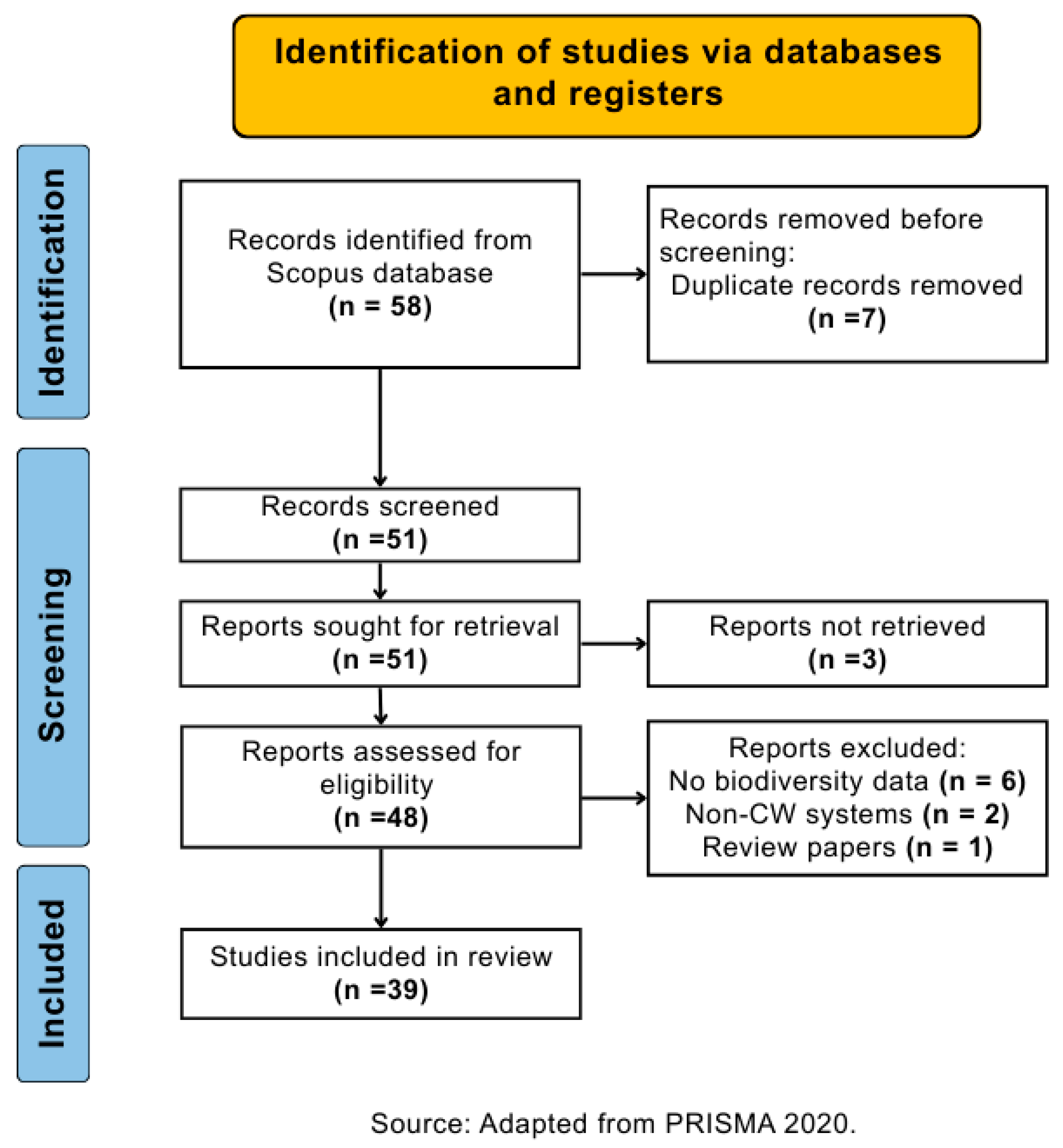

2.2. Systematic Review Methodology

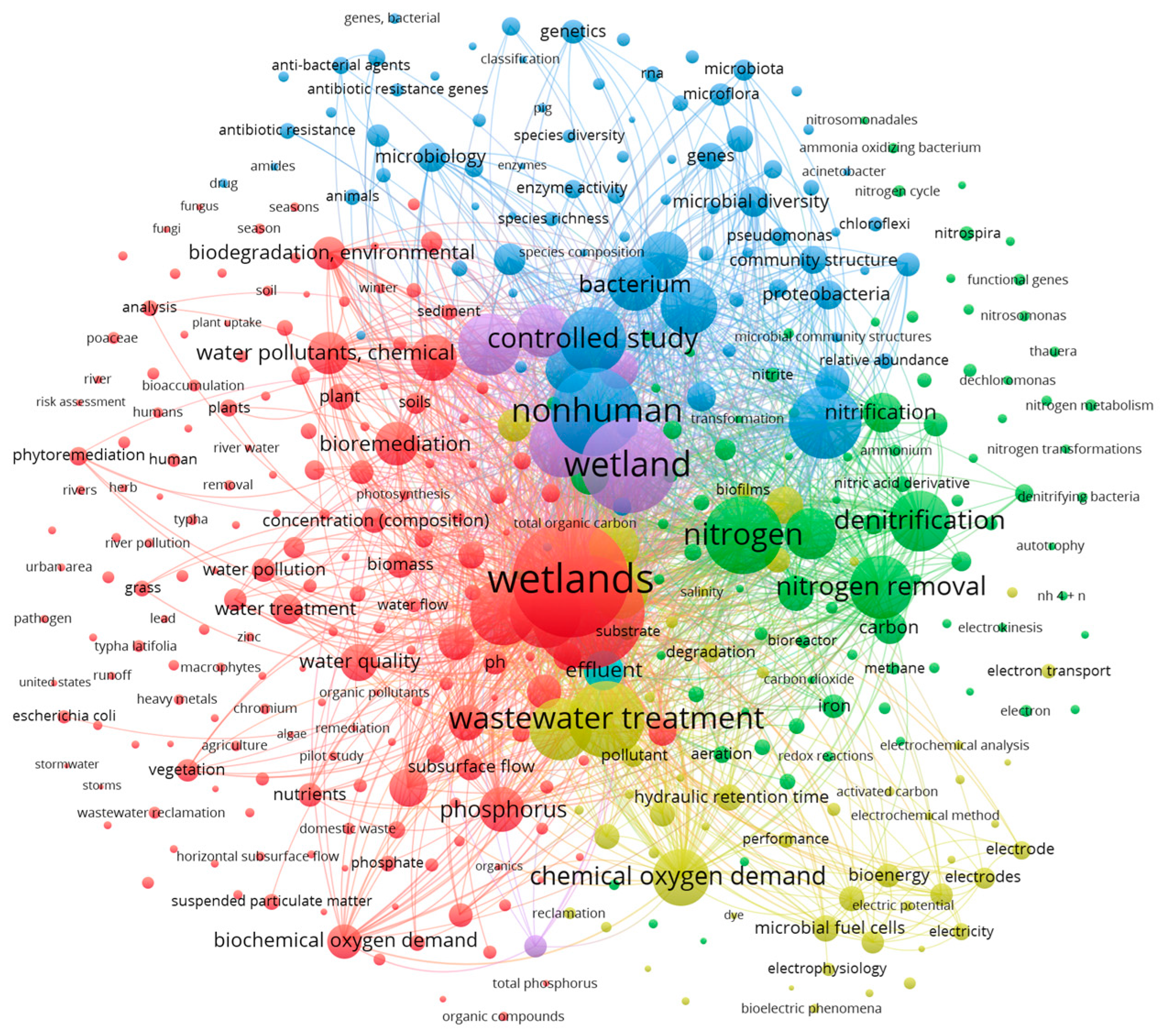

2.2.1. Development of Service-Specific Search Queries

2.2.2. Inclusion Criteria and Study Selection Process

2.2.3. Indicator Categorization and EBV Mapping

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biodiversity Indicators for Water Quality Regulation

3.1.1. Pollutant Removal

3.1.2. Nutrient Retention

3.1.3. Biological Uptake

3.2. Biodiversity Indicators for Climate Regulation

3.2.1. Carbon Storage

3.2.2. Greenhouse Gas Regulation

3.2.3. Microclimate Control

3.3. EBV-Based Synthesis of Biodiversity Indicators

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHP | Analytical hierarchy process |

| BBESI | Biodiversity-based Ecosystem Service Index |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| CWs | Constructed Wetlands |

| EBVs | Essential Biodiversity Variables |

| IPBES | Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services |

| MEA | Millenium Ecosystem Assessment |

| NbS | Nature-based Solutions |

| NCP | Nature’s Contributions to People |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| TN | Total nitrogen |

| TP | Total phosphorus |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

References

- Mancuso, G.; Bencresciuto, G.F.; Lavrnić, S.; Toscano, A. Diffuse water pollution from agriculture: A review of nature-based solutions for nitrogen removal and recovery. Water 2021, 13, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkard-Tapp, H.; Banks-Leite, C.; Cavan, E.L. Nature-based Solutions to tackle climate change and restore biodiversity. J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 58, 2344–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viti, M.; Löwe, R.; Sørup, H.J.D.; Rasmussen, M.; Arnbjerg-Nielsen, K.; McKnight, U.S. Knowledge gaps and future research needs for assessing the non-market benefits of Nature-Based Solutions and Nature-Based Solution-like strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 841, 156636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spieles, D.J. Wetland Construction, Restoration, and Integration: A Comparative Review. Land 2022, 11, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afiqah Rosli, F.; Ern Lee, K.; Ta Goh, C.; Mokhtar, M.; Talib Latif, M.; Lai Goh, T.; Simon, N. The Use of Constructed Wetlands in Sequestrating Carbon: An Overview. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2017, 16, 813–819. Available online: www.neptjournal.com (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Gorgoglione, A.; Torretta, V. Sustainable management and successful application of constructed wetlands: A critical review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vymazal, J. Constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment: Five decades of experience. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, B.K.; Balasubramanian, R. Constructed Wetlands for Reclamation and Reuse of Wastewater and Urban Stormwater: A Review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 836289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegleb, G.; Dahms, H.-U.; Byeon, W.I.; Choi, G. To What Extent Can Constructed Wetlands Enhance Biodiversity? Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2017, 8, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitau, P.; Ndiritu, G.; Gichuki, N. Ecological, recreational and educational potential of a small artificial wetland in an urban environment. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 2019, 44, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liquete, C.; Udias, A.; Conte, G.; Grizzetti, B.; Masi, F. Integrated valuation of a nature-based solution for water pollution control. Highlighting hidden benefits. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 22, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waly, M.M.; Mickovski, S.B.; Thomson, C.; Amadi, K. Impact of Implementing Constructed Wetlands on Supporting the Sustainable Development Goals. Land 2022, 11, 1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, A.M.N.; Alfarra, A.; Sorlini, S. Constructed Wetlands as a Solution for Sustainable Sanitation: A Comprehensive Review on Integrating Climate Change Resilience and Circular Economy. Water 2022, 14, 3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanakis, A.I. The Role of Constructed Wetlands as Green Infrastructure for Sustainable Urban Water Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorslund, J.; Jarsjo, J.; Jaramillo, F.; Jawitz, J.W.; Manzoni, S.; Basu, N.B.; Chalov, S.R.; Cohen, M.J.; Creed, I.F.; Goldenberg, R.; et al. Wetlands as large-scale nature-based solutions: Status and challenges for research, engineering and management. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 108, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, S.J.; Harrison, I.; Thieme, M.L.; Landsman, S.J.; Birnie-Gauvin, K.; Raghavan, R.; Creed, I.F.; Pritchard, G.; Ricciardi, A.; Hanna, D.E.L. Is it a new day for freshwater biodiversity? Reflections on outcomes of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. PLoS Sustain. Transform. 2023, 2, e0000065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Bina, O. The IPBES Conceptual Framework: Enhancing the Space for Plurality of Knowledge Systems and Paradigms. In Non-Human Nature in World Politics; Spinger: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borie, M.; Hulme, M. Framing global biodiversity: IPBES between mother earth and ecosystem services. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 54, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Pascual, U.; Stenseke, M.; Martín-López, B.; Watson, R.T.; Molnár, Z.; Hill, R.; Chan, K.M.A.; Baste, I.A.; Brauman, K.A.; et al. Assessing nature’s contributions to people. Science 2018, 359, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.S.S.; Kašanin-Grubin, M.; Solomun, M.K.; Sushkova, S.; Minkina, T.; Zhao, W.; Kalantari, Z. Wetlands as nature-based solutions for water management in different environments. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2023, 33, 100476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.M.; Settele, J.; Brondízio, E.; Ngo, H.; Guèze, M.; Agard, J.; Arneth, A.; Balvanera, P.; Brauman, K.; Butchart, S.; et al. The Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Summary for Policy Makers; Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Ed.; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019; Available online: www.ipbes.net (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Uy, M.J.; Robles, M.E.; Oh, Y.; Haque, M.T.; Mueca, C.C.; Kim, L.H. Biodiversity Monitoring in Constructed Wetlands: A Systematic Review of Assessment Methods and Ecosystem Functions. Diversity 2025, 17, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlone, M.; McNutt, K.; Richardson, S.; Bellingham, P.; Wright, E. Biodiversity monitoring, ecological integrity, and the design of the New Zealand Biodiversity Assessment Framework. N. Z. J. Ecol. 2020, 44, 3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.M.; Ferrier, S.; Walters, M.; Geller, G.N.; Jongman, R.H.G.; Scholes, R.J.; Bruford, M.W.; Brummitt, N.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Cardoso, A.C.; et al. Essential biodiversity variables. Science 2013, 339, 277–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeller, D.S.; Mihoub, J.-B.; Bowser, A.; Arvanitidis, C.; Costello, M.J.; Fernandez, M.; Geller, G.N.; Hobern, D.; Kissling, W.D.; Regan, E.; et al. An operational definition of essential biodiversity variables. Biodivers. Conserv. 2017, 26, 2967–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Cui, Y.; Dong, B.; Luo, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhao, S.; Wu, H. Test study of the optimal design for hydraulic performance and treatment performance of free water surface flow constructed wetland. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 238, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, D.P.L.; Vanrolleghem, P.A.; De Pauw, N. Constructed wetlands in Flanders: A performance analysis. Ecol. Eng. 2004, 23, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.E.; Bin Halmi, M.I.E.; Bin Abd Samad, M.Y.; Uddin, M.K.; Mahmud, K.; Abd Shukor, M.Y.; Sheikh Abdullah, S.R.; Shamsuzzaman, S.M. Design, operation and optimization of constructed wetland for removal of pollutant. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadlec, R.H.; Wallace, S. Treatment Wetlands; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, T.; Giannuzzi, C.; Beccarisi, L.; Aretano, R.; De Marco, A.; Pasimeni, M.R.; Zurlini, G.; Petrosillo, I. A constructed treatment wetland as an opportunity to enhance biodiversity and ecosystem services. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 82, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayusi, F.; Chavula, P.; Juma, L. Role of Redox Reactions and AI-Driven Approaches in Enhancing Nutrient Availability for Plants. LatIA 2023, 1, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, M.; Pelissari, C.; Roccaro, P.; Sezerino, P.H.; García, J.; Vagliasindi, F.G.A.; Ávila, C. Removal of organic carbon, nitrogen, emerging contaminants and fluorescing organic matter in different constructed wetland configurations. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 332, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.R.; DeLaune, R.D.; Inglett, P.W. Biogeochemistry of Wetlands; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, T.H.; Heard, M.S.; Isaac, N.J.B.; Roy, D.B.; Procter, D.; Eigenbrod, F.; Freckleton, R.; Hector, A.; Orme, C.D.L.; Petchey, O.L.; et al. Biodiversity and Resilience of Ecosystem Functions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaka, A.; Labib, A. Review of the main developments in the analytic hierarchy process. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 14336–14345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Demissew, S.; Carabias, J.; Joly, C.; Lonsdale, M.; Ash, N.; Larigauderie, A.; Adhikari, J.R.; Arico, S.; Báldi, A.; et al. The IPBES Conceptual Framework—Connecting nature and people. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M. Chapter Six—Multi-criteria analysis. Adv. Transp. Policy Plan. 2020, 6, 165–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moomaw, W.R.; Chmura, G.L.; Davies, G.T.; Finlayson, C.M.; Middleton, B.A.; Natali, S.M.; Perry, J.E.; Roulet, N.; Sutton-Grier, A.E. Wetlands In a Changing Climate: Science, Policy and Management. Wetlands 2018, 38, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissling, W.D.; Ahumada, J.A.; Bowser, A.; Fernandez, M.; Fernández, N.; García, E.A.; Guralnick, R.P.; Isaac, N.J.B.; Kelling, S.; Los, W.; et al. Building essential biodiversity variables (EBVs) of species distribution and abundance at a global scale. Biol. Rev. 2018, 93, 600–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, A.; Zhang, Y.; Gajaraj, S.; Brown, P.B.; Hu, Z. Toward the development of microbial indicators for wetland assessment. Water Res. 2013, 47, 1711–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heink, U.; Kowarik, I. What are indicators? On the definition of indicators in ecology and environmental planning. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Li, P.; Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, K.; Du, C.; Chen, H. A review on the removal of heavy metals and metalloids by constructed wetlands: Bibliometric, removal pathways, and key factors. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vymazal, J. Horizontal sub-surface flow and hybrid constructed wetlands systems for wastewater treatment. Ecol. Eng. 2005, 25, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natuhara, Y. Ecosystem services by paddy fields as substitutes of natural wetlands in Japan. Ecol. Eng. 2013, 56, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeller, D.S.; Weatherdon, L.V.; Loyau, A.; Bondeau, A.; Brotons, L.; Brummitt, N.; Geijzendorffer, I.R.; Haase, P.; Kuemmerlen, M.; Martin, C.S.; et al. A suite of essential biodiversity variables for detecting critical biodiversity change. Biol. Rev. 2018, 93, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geijzendorffer, I.R.; Regan, E.C.; Pereira, H.M.; Brotons, L.; Brummitt, N.; Gavish, Y.; Haase, P.; Martin, C.S.; Mihoub, J.B.; Secades, C.; et al. Bridging the gap between biodiversity data and policy reporting needs: An Essential Biodiversity Variables perspective. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 1341–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proença, V.; Martin, L.J.; Pereira, H.M.; Fernandez, M.; McRae, L.; Belnap, J.; Böhm, M.; Brummitt, N.; García-Moreno, J.; Gregory, R.D.; et al. Global biodiversity monitoring: From data sources to Essential Biodiversity Variables. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 213, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, P.; Pei, H.; Hu, W.; Shao, Y.; Li, Z. How to increase microbial degradation in constructed wetlands: Influencing factors and improvement measures. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 157, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Li, Q.; Luo, Z.; Wu, C.; Sun, B.; Zhao, D.; Chi, S.; Cui, Z.; Xu, A.; Song, Z. Microbial community structure in a constructed wetland based on a recirculating aquaculture system: Exploring spatio-temporal variations and assembly mechanisms. Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 197, 106413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Long, Y.; Yu, G.; Wang, G.; Zhou, Z.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, K.; Wang, S. A Review on Microorganisms in Constructed Wetlands for Typical Pollutant Removal: Species, Function, and Diversity. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 845725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, A.; Chauhan, M.; Kumar Sharma, P.; Kumari, M.; Mitra, D.; Joshi, S. Microbiological dimensions and functions in constructed wetlands: A review. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2024, 7, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seth, N.; Vats, S.; Lakhanpaul, S.; Arafat, Y.; Mazumdar-Leighton, S.; Bansal, M.; Babu, C.R. Microbial community diversity of an integrated constructed wetland used for treatment of sewage. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1355718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowrotek, M.; Ziembińska-Buczyńska, A.; Miksch, K. Qualitative variability in microbial community of constructed wetlands used for purifying wastewater contaminated with pharmaceutical substances. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2015, 62, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Peng, Y. CW-MFC for efficient degradation of ofloxacin-containing wastewater and dynamic analysis of microbial communities. IScience 2025, 28, 112516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xue, M.; Wang, Z.; Xia, W.; Zhang, C. Integrated Constructed Wetland–Microbial Fuel Cell Systems Using Activated Carbon: Structure-Activity Relationship of Activated Carbon, Removal Performance of Organics and Nitrogen. Water 2024, 16, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Pang, S.; Wang, P.; Wang, C.; Guo, C.; Addo, F.G.; Li, Y. Responses of bacterial community structure and denitrifying bacteria in biofilm to submerged macrophytes and nitrate. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.G.; Wimpee, C.F.; McGuire, S.A.; Ehlinger, T.J. Responses of Bacterial Taxonomical Diversity Indicators to Pollutant Loadings in Experimental Wetland Microcosms. Water 2022, 14, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Liu, F.; Fu, Z.; Qiao, H.; Wang, J. Enhancing total nitrogen removal in constructed wetlands: A Comparative study of iron ore and biochar amendments. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 367, 121873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Xiao, X.; Xue, J. Purification effect and microorganisms diversity in an Acorus calamus constructed wetland on petroleum-containing wastewater. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2020, 32, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, R.; Sawada, K.; Soda, S. Greywater treatment using lab-scale systems combining trickling filters and constructed wetlands with recycled foam glass and water spinach. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 27, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pang, Q.; Peng, F.; Zhang, A.; Zhou, Y.; Lian, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, F.; Zhu, Y.; Ding, C.; et al. Response Characteristics of Nitrifying Bacteria and Archaea Community Involved in Nitrogen Removal and Bioelectricity Generation in Integrated Tidal Flow Constructed Wetland-Microbial Fuel Cell. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.R.; Shin, J.; Guevarra, R.B.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.W.; Seol, K.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.B.; Isaacson, R.E. Deciphering diversity indices for a better understanding of microbial communities. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 27, 2089–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A.E. Measuring biological diversity. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R1174–R1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budka, A.; Łacka, A.; Szoszkiewicz, K. Estimation of river ecosystem biodiversity based on the Chao estimator. Biodivers. Conserv. 2018, 27, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Xu, D.; Liu, B.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, Z. Structural and metabolic responses of microbial community to sewage-borne chlorpyrifos in constructed wetlands. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 44, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LRobles, M.E.; DGReyes, N.J.; Choi, H.S.; Jeon, M.S.; Kim, L.H. Carbon Storage and Sequestration in Constructed Wetlands: A Systematic Review. J. Wetl. Res. 2023, 25, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.; Jones, S. Assessing organic matter and organic carbon contents in soils of created mitigation Wetlands in Virginia. Environ. Eng. Res. 2013, 18, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, M.; Huang, P.; Hipesy, M.; Dai, L.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Z. The below-ground biomass contributes more to wetland soil carbon pools than the above-ground biomass—A survey based on global wetlands. J. Plant Ecol. 2024, 17, rtae017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerburg, B.G.; Vereijken, P.H.; de Visser, W.; Verhagen, J.; Korevaar, H.; Querner, E.P.; de Blaeij, A.T.; van der Werf, A. Surface water sanitation and biomass production in a large constructed wetland in the Netherlands. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 18, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Chang, J.; Fan, X.; Du, Y.; Chang, S.X.; Zhang, C.; Ge, Y. Plant species diversity impacts nitrogen removal and nitrous oxide emissions as much as carbon addition in constructed wetland microcosms. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 93, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Li, K.; Fang, J.; Quan, Q.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J. The Invasion of Alternanthera philoxeroides Increased Soil Organic Carbon in a River and a Constructed Wetland With Different Mechanisms. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 574528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge-Salazar, M.J.; Tovar, C.; Cuadros-Adriazola, J.; Baiker, J.R.; Montesinos-Tubée, D.B.; Bonnesoeur, V.; Antiporta, J.; Román-Dañobeytia, F.; Fuentealba, B.; Ochoa-Tocachi, B.F.; et al. Ecohydrology and ecosystem services of a natural and an artificial bofedal wetland in the central Andes. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhaj Baddar, Z.; Xu, X. Evaluation of changes in the microbial community structure in the sediments of a constructed wetland over the years. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhaj Baddar, Z.; Bier, R.; Spencer, B.; Xu, X. Microbial Community Changes across Time and Space in a Constructed Wetland. ACS Environ. Au 2024, 4, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberholzer, M.M.; Oberholster, P.J.; Ndlela, L.L.; Botha, A.M.; Truter, J.C. Assessing Alternative Supporting Organic Materials for the Enhancement of Water Reuse in Subsurface Constructed Wetlands Receiving Acid Mine Drainage. Recycling 2022, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakin, I.; Marcello, L.; Morrissey, B.; Gaffney, P.P.J.; Taggart, M.A. Long-term monitoring of constructed wetlands in distilleries in Scotland—Evaluating treatment performance and seasonal microbial dynamics. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 375, 124279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Sha, W.L.; Yu, G.H.; Zhang, N.X.; Shu, F.Y.; Gong, Z.J.; Kong, Y. Differences in Denitrifying Community Structure of the Nitrous Oxide Reductase (Nosz I) Type Gene in a Multi-Stage Surface Constructed Wetland. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2022, 20, 1551–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Yao, M.; Li, L.; Qin, Y. Assessment of Carbon Reduction Benefits of A/O-Gradient Constructed Wetland Renovation for Rural Wastewater Treatment in the Southeast Coastal Areas of China Based on Life Cycle Assessment: The Example of Xiamen Sanxiushan Village. Sustainability 2023, 15, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Shen, L.; Tao, J.; Xiao, D.; Shi, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, M.; Han, W. Effects of plant species diversity and density of Acorus calamus and Reineckea carnea on nitrogen removal and plant growth in constructed wetlands during the cold season. Environ. Eng. Res. 2024, 29, 220297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton-Grier, A.E.; Megonigal, J.P. Plant species traits regulate methane production in freshwater wetland soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiau, Y.J.; Chen, Y.A.; You, C.R.; Lai, Y.C.; Lee, M. Compositions of sequestrated soil carbon in constructed wetlands of Taiwan. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overbeek, C.C.; Harpenslager, S.F.; van Zuidam, J.P.; van Loon, E.E.; Lamers, L.P.M.; Soons, M.B.; Admiraal, W.; Verhoeven, J.T.A.; Smolders, A.J.P.; Roelofs, J.G.M.; et al. Drivers of Vegetation Development, Biomass Production and the Initiation of Peat Formation in a Newly Constructed Wetland. Ecosystems 2020, 23, 1019–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philben, M.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Z.; Taş, N.; Wullschleger, S.D.; Graham, D.E.; Gu, B. Anaerobic respiration pathways and response to increased substrate availability of Arctic wetland soils. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2020, 22, 2070–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Lang, Y.; Ding, H.; Han, X.; Wang, T.; Liu, Z.; La, W.; Liu, C.-Q. Sulfate availability affect sulfate reduction pathways and methane consumption in freshwater wetland sediments. Appl. Geochem. 2024, 176, 106215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, L.P.; Heinemeyer, A.; Inseson, P. Effects of three years of soil warming and shading on the rate of soil respiration: Substrate availability and not thermal acclimation mediates observed response. Glob. Change Biol. 2007, 13, 1761–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelvin, J.; Acreman, M.C.; Harding, R.J.; Hess, T.M. Micro-climate influence on reference evapotranspiration estimates in wetlands. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2017, 62, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Arx, G.; Graf Pannatier, E.; Thimonier, A.; Rebetez, M. Microclimate in forests with varying leaf area index and soil moisture: Potential implications for seedling establishment in a changing climate. J. Ecol. 2013, 101, 1201–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Chen, B.; Sun, W.; Feng, T.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Fu, B. Estimation of Coastal Wetland Vegetation Aboveground Biomass by Integrating UAV and Satellite Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maselli, F.; Chiesi, M.; Angeli, L.; Fibbi, L.; Rapi, B.; Romani, M.; Sabatini, F.; Battista, P. An improved NDVI-based method to predict actual evapotranspiration of irrigated grasses and crops. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 233, 106077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vihervaara, P.; Auvinen, A.P.; Mononen, L.; Törmä, M.; Ahlroth, P.; Anttila, S.; Böttcher, K.; Forsius, M.; Heino, J.; Heliölä, J.; et al. How Essential Biodiversity Variables and remote sensing can help national biodiversity monitoring. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2017, 10, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, M.; van Duren, I.; Skidmore, A.K.; Saintilan, N. Harmonizing Forest Conservation Policies with Essential Biodiversity Variables Incorporating Remote Sensing and Environmental DNA Technologies. Forests 2022, 13, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Végh, L.; Noda, H.; Böttcher, K.; Vihervaara, P.; Kass, J.; Hama, I.; Saito, Y. National-Scale Terrestrial Biodiversity and Ecosystem Monitoring with Essential Biodiversity Variables in Japan and Finland. Ecol. Res. 2025, 40, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moersberger, H.; Martin, J.G.C.; Junker, J.; Georgieva, I.; Bauer, S.; Beja, P.; Breeze, T.; Brotons, L.; Bruelheide, H.; Fernández, N.; et al. Europa Biodiversity Observation Network: User and Policy Needs Assessment. ARPHA Prepr. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NCP (Ecosystem Service) | Search Query (Scopus Advanced Search Format) | Results (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Water Quality Regulation | Constructed wetland terms (constructed wetland *, treatment wetland *, engineered wetland *, HSSF, VSSF, FWS). | 31 |

| Biodiversity metrics (biodiverse *, species richness, Shannon, Simpson, community composition, microbial diversity); | ||

| Water quality indicators (TN, TP, NH4, NO3, COD, BOD, TSS, turbidity, removal efficiency, micropollutants, HRT, MFC | ||

| Climate Regulation | Constructed wetland terms (constructed wetland *, treatment wetland *, engineered wetland *, HSSF, VSSF, FWS). | 27 |

| Biodiversity metrics (biodiverse *, species richness, diversity index, Shannon, Simpson, community composition, microbial diversity); | ||

| Climate regulation indicators (carbon sequestration, carbon storage, SOC, biomass, greenhouse gases, carbon flux, methane, CO2, N2O, respiration, evapotranspiration). |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Studies conducted in constructed, engineered, managed, or treatment wetlands designed for water quality improvement or ecosystem enhancement. | Studies lacking biodiversity data or focusing exclusively on physicochemical parameters without biological assessment. |

| Empirical studies reporting microbial, plant, or faunal biodiversity indicators within CWs. | Research focusing on unmanaged natural wetlands, ponds, rice fields, or unrelated aquatic systems not functioning as treatment or restoration wetlands. |

| Studies demonstrating an explicit linkage between biodiversity and ecosystem functions, such as nutrient removal, carbon storage, or greenhouse gas regulation. | Non–peer-reviewed, methodologically incomplete, or review articles without original empirical data. |

| Ecosystem Function | Biodiversity Indicator | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Pollutant Removal | Microbial Alpha Diversity (Shannon Index) | [54] |

| Taxonomic Composition (Phylum Level) | [55] | |

| Functional Microbial Abundance (Pollutant-Degrading Taxa) | [56,57] | |

| Nutrient Retention | Microbial Alpha Diversity (Shannon Index) | [58] |

| Taxonomic Composition (Nutrient-Cycling Genera) | [57,59] | |

| Functional Gene Diversity (Nutrient Cycling) | [59,60] | |

| Biological Uptake | Microbial Diversity in Vegetated Sediments | [61] |

| Relative Abundance of Rhizosphere-Enriched Genera | [62] | |

| Plant–Microbe Functional Complementarity | [58] | |

| Root-Zone Oxygenation Indicator Taxa | [63] |

| Ecosystem Function | Biodiversity Indicator | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Storage | Plant Biomass and Allocation | [71,72,73] |

| Dominant High-Biomass or Peat-Forming Species | [74] | |

| Root-Zone Microbial Activity (Carbon Stabilization) | [75] | |

| Greenhouse Gas Regulation | Microbial Community Complexity (Community Structure) | [76] |

| Redox-Regulating Microbial Guilds | [76,77,78] | |

| Functional Gene Diversity (Carbon and GHG Cycling) | [79] | |

| Microclimate Control | Canopy Structure | [74,80] |

| Plant Functional Diversity | [72] | |

| Seasonal Biomass (Productivity) | [71,81] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Uy, M.J.; Robles, M.E.; Oh, Y.; Kim, L.-H. Identifying Biodiversity-Based Indicators for Regulating Ecosystem Services in Constructed Wetlands. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010007

Uy MJ, Robles ME, Oh Y, Kim L-H. Identifying Biodiversity-Based Indicators for Regulating Ecosystem Services in Constructed Wetlands. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleUy, Marvin John, Miguel Enrico Robles, Yugyeong Oh, and Lee-Hyung Kim. 2026. "Identifying Biodiversity-Based Indicators for Regulating Ecosystem Services in Constructed Wetlands" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010007

APA StyleUy, M. J., Robles, M. E., Oh, Y., & Kim, L.-H. (2026). Identifying Biodiversity-Based Indicators for Regulating Ecosystem Services in Constructed Wetlands. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010007