1. Introduction

As urban space becomes increasingly limited, the vertical expansion of existing buildings has become more common. Consequently, changes in building height have become an important indicator of urban development and the utilization of space [

1]. As a fundamental morphological feature, building height is indicative of the interaction between human activity and the structure of urban space, and also plays a critical role in land monitoring and risk assessment. However, conventional methods for monitoring changes in building height frequently encounter issues such as high costs, limited coverage, and low efficiency, which hinders the effective supervision of large-scale and dynamic urban areas.

With advances in remote sensing technology, monitoring changes in building height has gradually shifted from conventional field measurements to multi-source remote sensing data, including point clouds [

2], stereo image pairs [

3], LiDAR [

4], and digital surface models (DSM) [

5]. Based on these data types, researchers have developed a range of monitoring approaches, may be broadly categorized into three distinct groupings. The first uses height differences between two time periods to extract areas of change, but this method is sensitive to threshold settings and struggles in complex environments [

6]. The second relies on geometric attributes for object classification and change comparison, yet faces challenges with segmentation accuracy and semantic clarity in heterogeneous urban settings [

7]. The third approach involves the integration of multi-source data into deep learning frameworks to facilitate end-to-end building change detection. While this method offers automation advantages, it relies heavily on large training datasets. It also has limited generalization ability and is prone to error accumulation during data fusion [

8]. Furthermore, the acquisition of remote sensing data is constrained by factors such as orbital cycles and weather conditions. This makes it difficult to obtain images at the optimal time and limits its use in large-scale, time-sensitive urban monitoring.

Street-view imagery has recently gained increasing attention as a novel data source characterized by ground-level perspectives and flexible acquisition. In comparison to remote sensing imagery, street view imagery enable the capture of more detailed facade information and a clearer representation of architectural details. They also have advantages such as lower costs and higher acquisition frequencies, making them a promising alternative for detecting building height changes [

9]. Some studies have attempted to estimate building heights using street-view images. However, most of these studies are limited to static extraction from single-date images. They have not fully utilized the temporal dimension of such data.

To address the limitations of existing methods in building change detection and height estimation, this study proposes an automated approach for monitoring building height changes using multi-temporal street view imagery. The method begins with building detection using YOLO-v5, followed by improved image alignment through a neighboring region resampling strategy and the SuperGlue model. Based on this alignment, the system integrates morphological features, color, and depth information to identify potential change areas, and applies a geometric model derived from panoramic imaging principles to accurately calculate changes in building height. This research enhances both the automation and accuracy of urban building change detection, offering a practical new path for dynamic urban monitoring and smart city management.

2. Related Work

2.1. Detection of Changes in Building Height Based on Remote Sensing Imagery

Building height change detection focuses on identifying structural modifications in the vertical direction, mainly involving additions or demolitions. Currently, remote sensing imagery remains the primary data source for such tasks, and commonly used methods can be broadly classified into three categories: post-classification detection, direct comparison, and joint detection approaches.

The post-classification detection method involves classifying remote sensing images first, and then identifying differences to determine changes. The accuracy of the method is contingent upon prior knowledge of land cover types. For instance, Abusaada et al. [

10] classified images based on height information and applied a road-overlap-based adaptive CI update strategy along with a dual-threshold system to distinguish building change states. Similarly, Cao et al. [

11] used multi-temporal airborne LiDAR point clouds, performing classification before applying a dual-threshold model to detect changes. Conversely, the direct comparison approach commences with the analysis of variations in multi-temporal data, subsequently identifying the areas of change and their classification. Wang et al. [

12] generated DSMs using stereo satellite images from two time points and extracted changes through difference analysis. However, this method is easily influenced by factors such as weather during data collection, which can cause inconsistent data quality across time. Fixed thresholds also limit adaptability in complex scenes, often leading to false detection [

13]. To overcome these issues, joint detection methods integrate difference analysis and change determination into a single process, often relying on machine learning or deep neural networks to improve detection accuracy and efficiency [

14]. Nevertheless, these methods depend heavily on large, high-quality training datasets and often lack stability when applied across different regions [

1].

Although the above methods have made some progress in identifying changes in building height, they still face problems such as difficulty in obtaining data, strong model dependence, and limited accuracy in interpreting changes. In comparison, street view imagery have advantages such as easy acquisition and clear expression of details, and are gradually becoming a new data source for monitoring changes in buildings.

2.2. Detection of Changes in Building Height Based on Street View Imagery

With the growing availability of street view data, its application in building change detection has started to gain attention. However, studies that directly focus on detecting changes in building height using street view imagery is still limited in number. The majority of current research is focused on two primary domains: scene change detection and building height estimation.

In terms of scene change detection, existing methods are generally divided into two categories: image registration-based and deep learning-based approaches. Image registration-based methods address parallax issues by aligning images and subsequently identifying changes through pixel differences or edge detection. These are appropriate for scenarios where registration accuracy is limited but real-time processing is required. For example, some studies use 3D reconstruction combined with deconvolutional networks to detect pixel-level changes [

15], while others use edge detection to identify change regions [

16]. Deep learning-based methods, on the other hand, use end-to-end networks to extract change regions and typically rely on relatively well-aligned image pairs for training. These include CNN models constrained by dense optical flow [

17], Siamese networks that incorporate semantic features [

18], and classification models that integrate multiple image features [

19]. However, challenges remain in applying street view imagery to change detection due to structural appearance shifts caused by lighting and viewpoint differences, as well as high false detection rates and low accuracy resulting from image noise.

For building height estimation, methods are generally divided into projection-based and deep learning-based approaches. Projection-based methods usually rely on recognizable structures in the image and known camera parameters. For instance, some studies estimate door heights using perspective geometry [

20], while others combine image outlines with camera models for height calculation [

21]. However, such methods often rely on known structural dimensions, thereby ignoring the mapping relationship between pixels and actual scale. To address this, Ge et al. [

22] improved the pinhole camera model by establishing a mapping between pixel height and real-world height, helping to reduce the influence of camera angles. Deep learning-based methods estimate height by extracting semantic features, vanishing points, and line segments from images and combining these with model outputs. For example, Xu et al. [

23] used Mask R-CNN to detect building boundaries and applied panoramic projection principles to estimate height. Zhao et al. [

24] proposed the RoofNet neural network to detect rooflines, then applied a sorting algorithm to select optimal lines for height calculation. While these approaches improve both automation and accuracy, they often suffer from high dependence on deep learning models, computational intensity, and limited scalability for large-scale height estimation. Furthermore, most existing studies focus on height estimation using single-time images, with limited exploration into detecting height changes over time using multi-temporal street view data.

2.3. Building Object Recognition and Feature Extraction Based on Street View Imagery

As a new type of data source, street view imagery offers not only open access and free availability but also rich visual representation of street structures and features [

25]. Because of these advantages, it shows strong potential for applications in urban infrastructure management, building identification, facade analysis, and urban disaster risk assessment.

Many studies have explored the use of street view imagery for building detection and spatial feature extraction. For example, Ogawa et al. [

26] improved building recognition accuracy by optimizing camera pose using street view imagery combined with map-based depth information. Roussel et al. [

27] integrated multi-temporal and multi-view street view imagery and applied a global optimization algorithm to correct spatial misalignments between the images and the actual building layouts. Their method achieved 88% recognition accuracy even in densely built and heavily occluded urban areas, outperforming both traditional geometric techniques and earlier deep learning models. In addition to overall building detection, some research has focused on extracting structural features. Related research proposes a deep model called FSA-UNet that integrates remote sensing and street view imagery. This model was used to generate a building vulnerability index, achieving a mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) of 82% in a case study of Hefei City [

28]. By combining multi-source imagery, attention mechanisms, and edge features, the model significantly improved the accuracy of spatial assessments. However, most current studies rely on qualitative indicators and lack the systematic integration of quantitative elements such as building height, window and door layout, terrain, and density, which limits the broader applicability and practical value of these models.

In summary, street view imagery not only supports the identification of urban spatial elements but also offer potential for capturing vertical structural details, making them a valuable data source and methodological foundation for tasks such as monitoring building height changes.

3. Materials and Methods

This study presents a comprehensive method for monitoring changes in building height using multi-temporal street view imagery, focusing on building identification, height change detection, and height estimation. The process starts with the collection of multi-temporal imagery based on GIS data and open-access street view platforms. The YOLO-v5 model is then used to detect buildings. And image alignment is refined by resampling neighboring regions and using the SuperGlue matching model. To identify areas of height variation, the approach integrates image morphology, color and depth information. Finally, the amount of height change is estimated using the principles of panoramic imaging. The workflow diagram is shown in

Figure 1.

3.1. Building Target Recognition

The YOLO series of algorithms represents a class of efficient one-stage object detection algorithmsy [

29], offering a satisfactory balance between speed and accuracy. In this study, the focus is on the extraction of bounding boxes surrounding buildings, high detection precision is not the top priority. Instead, model lightweight design and inference efficiency are of greater importance. The YOLO-v5 model offers a strong balance between detection performance and fast inference speed. Previous research has shown that the error rate in door frame recognition can be as low as 0.0469 [

20], which is sufficient to meet the accuracy requirements of this study.

3.1.1. Model Training

The training data was collected from Baidu Street View, using regions that do not overlap with the study area to improve the model’s generalization ability. The labeling process was done manually using the Labelme tool. During annotation, bounding boxes were drawn around individual buildings or continuous building groups, and only image information related to buildings was retained. The completeness of nearby objects was allowed to be ignored when necessary.

3.1.2. Target Detection Accuracy Evaluation

This study evaluates the performance of the YOLO-v5 model in detecting building targets using three metrics: Precision, Recall, and F1 Score. The higher the score, the better the model’s detection performance. These indicators are calculated based on true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN), with the specific formulas shown below:

3.2. Building Contour Change Detection

3.2.1. Image Registration

Due to variations in camera position and viewing angle across different time periods, as well as uneven distortion across panoramic images, this study adopted the SuperGlue model proposed by Sarlin et al. for image registration. The model incorporates self-attention and cross-attention mechanisms to learn the 3D geometric relationships between image pairs, making it effective for feature matching across varying perspectives.

Additionally, considering potential errors in the street view sampling locations, images captured at different times may have differences in viewpoints and visible coverage, which can affect registration accuracy. To address this issue, a circular search area is defined using the original sampling point as the center. The intersections between this area and nearby roads are used as candidate positions to re-capture images. The normalized cross-correlation (NCC) is then computed to measure similarity, and the image with the highest similarity to the original is selected as a replacement.

In this context, denotes the grayscale value of image at coordinates , while x and y represent the displacement coordinates as slides across image .

3.2.2. Detection Based on Morphological Changes

In order to enhance texture detail and visual clarity, Canny edge detection was applied to the registered images, and used an adaptive double-threshold strategy based on histogram analysis to better handle lighting variations. Morphological operations such as dilation, erosion, and hole filling were then used to strengthen edge continuity and improve contour completeness.

With enhanced edges, change regions are extracted through difference analysis between the two temporal images. To remove false changes caused by vegetation occlusion, a greenness index based on RGB reflectance is introduced. This helped filter out areas identified as “green changes”, resulting in a change map

, where

,

and

represent the blue, green, and red bands of the change region, respectively.

In addition, the Depth Anything model was employed for monocular depth estimation. By comparing the average depth of the left, right, and bottom neighborhoods of the change region, pseudo-change with depth differences below a defined threshold are filtered out. The use of minimum bounding rectangles and structural consistency criteria were used to improve identification accuracy, yielding the final change map,

.

In this context, denotes the minimum bounding rectangle of the contour, represents the movement distance, and is the predefined threshold.

3.2.3. Evaluation of Change Detection Accuracy

In this study, the dataset contains a significantly higher proportion of unchanged than changed samples. This distribution reflects the imbalance between positive and negative samples commonly found in change detection scenarios [

30]. For example, in popular change detection datasets, positive samples account for only about 4.65% in LEVIR-CD [

31] and even less, about 4.33%, in WHU-CD [

32], indicating that changed samples are a minority in these datasets. If standard deep learning evaluation metrics were applied directly, the large volume of unchanged samples would overshadow the model’s ability to detect real changes. To address this issue, the detection accuracy for both changed and unchanged classes was calculated separately, as follows:

In this context, denotes the number of correctly detected buildings in the corresponding class, and represents the total number of buildings in that class.

3.3. Calculation of Building Height Changes

To establish the mapping between image coordinates and spherical coordinates, this study is based on the following assumptions: (1) the panoramic image is captured in a planar space; (2) the pitch angle of the panoramic camera is zero and the camera is parallel to the ground; (3) buildings are perpendicular to the horizontal ground; (4) a cylindrical projection is used to project the

spherical image onto a cylindrical surface. Based on these assumptions, the center horizontal line of the image corresponds to the elevation line passing through the camera center. The camera center is regarded as the origin of the spherical coordinate system, and any point in the image can be located using its projection distance

D, azimuth angle

, and pitch angle

, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

In the image coordinate system, the top-left corner of the image is defined as the origin of a Cartesian coordinate system. According to the projection principle, the transformation from image coordinates

to spherical coordinates

is as follows:

To reduce the distortion caused by horizontal and vertical viewing angles during cylindrical projection, this study introduces a projection distortion compensation mechanism. The goal is to weaken the influence of projection distortion on measured lengths. In a cylindrical projection, distortion is smaller near the center of the image and becomes larger toward the edges. Therefore, based on the assigned angle of each pixel, we compute a vertical factor

and a horizontal factor

to correct the pitch and azimuth angles, thereby reducing vertical compression and horizontal stretching.

Based on coordinate transformation, this study applies the principle of triangulation, using the sampled point in the panoramic image (i.e., the panoramic camera center) as the reference. The boundary of the building facade variation is treated as the target signal point. By utilizing the difference in pitch angles between the upper and lower edges of the building contour in the image, and incorporating line-of-sight geometry, the vertical height of the structure is estimated, thereby enabling the calculation of building height changes. Given the effective sampling interval is approximately 30 m, atmospheric refraction errors (<0.01 mm) are negligible.

Due to vertical compression inherent in cylindrical panoramic projection, a vertical correction factor

is introduced to compensate for this distortion. Accordingly, the building height change (Cheight) is defined as follows:

4. Results

4.1. Experimental Data

This study selected two areas as experimental sites: Baijiatang Community and the residential area to the left of the South Campus of Hunan University of Commerce (referred to as the “South Area”) in Changsha, Hunan Province. The Baijiatang Community has experienced a surge in building extensions due to nearby tech base developments and rapid population growth, making it a valuable source of data for analyzing building height changes. In contrast, although the “South Area” shows no signs of structural extensions, its proximity to both a university and commercial zones makes it a suitable site for testing the adaptability of panoramic image-based algorithms across diverse environments.

The main roads within both residential areas were extracted using OpenStreetMap (OSM) data. Missing building outlines and road segments were supplemented through manual digitization using ArcGIS software (version 10.6) and Baidu Maps, as shown in

Figure 3. And street view images were collected from the Baidu Time Machine. After filtering the images by quality and time intervals between image captures, a total of 308 images were selected for experimental analysis.

4.2. Experimental Environment

The experimental environment is a Windows 11 system with an AMD Ryzen 7 7735H processor featuring Radeon Graphics at 3.20 GHz, and 16 GB of RAM. The runtime environment uses Python version 3.8.

4.3. Experimental Results

4.3.1. Results of Building Target Recognition

The YOLO-v5 model can effectively detect both individual buildings and rows of connected buildings, and also shows good performance when targets are partially obscured by light vegetation (refer

Figure 4). The model performs stably in building detection tasks, correctly identifying 291 buildings, with 55 false positives and 101 missed detections. This results in a precision of 0.841, a recall of 0.742, and an F1 score of 0.788. Since this study focuses on detecting buildings rather than extracting precise building outlines, the results are sufficient for the research needs and have no direct impact on building height calculations.

4.3.2. Building Change Detection

Based on the object detection results, a total of 395 pairs of building images were extracted, including 47 pairs in the changed category and 348 pairs in the unchanged category. The proposed method accurately identified 40 pairs of changed images, achieving an accuracy of 85.11% for the changed category. Within the unchanged category, the model accurately identified 313 pairs, with an accuracy of 89.94%. This finding suggests that the model exhibits a high level of capability in distinguishing between categories.

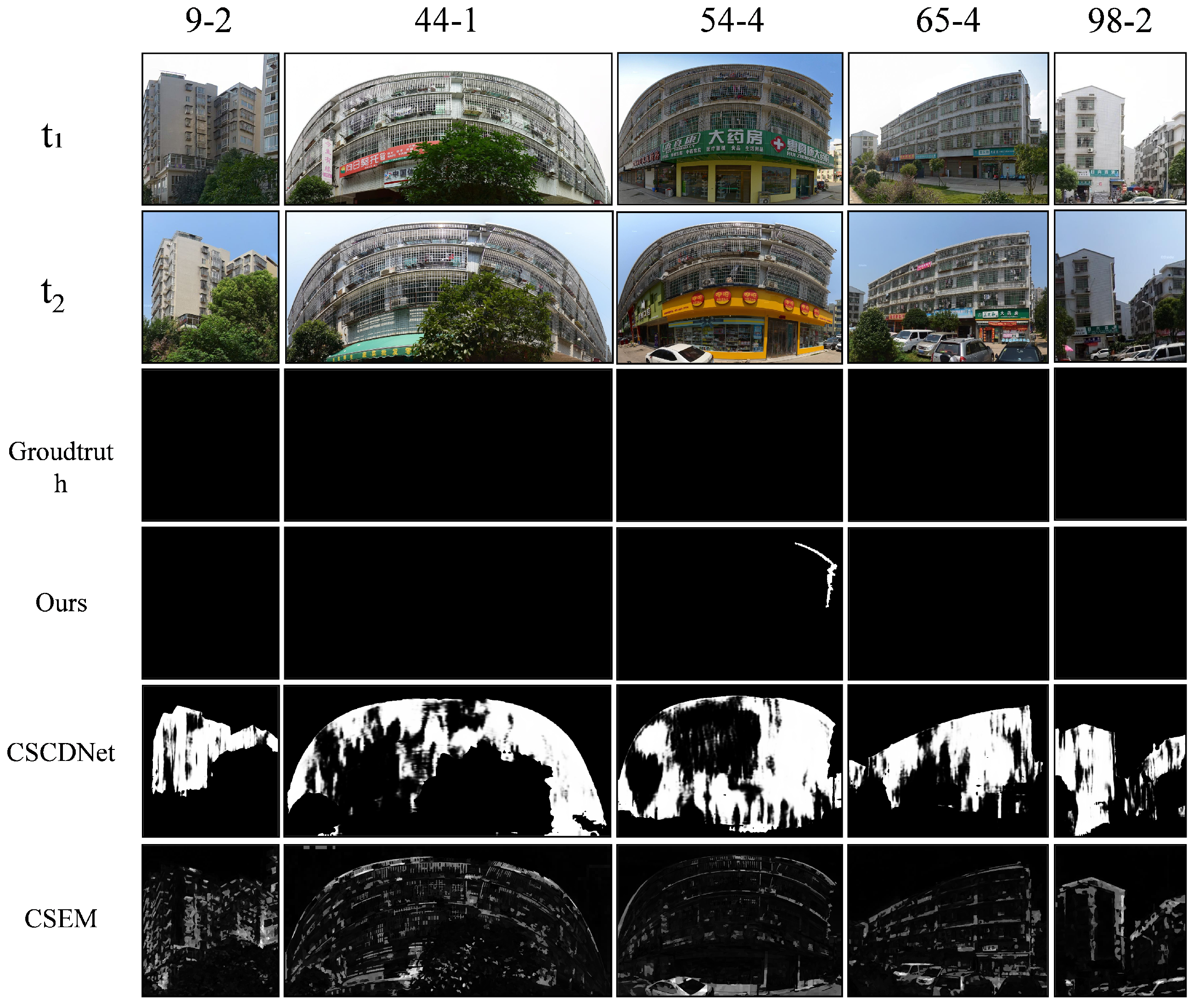

This method was compared with two other representative approaches. The CSCDNet algorithm [

33] is a paradigmatic deep learning method, while the SCEM algorithm [

34] adopts an unsupervised strategy based on structural consistency.

It is challenging to calculate the overall accuracy directly. This is because the CSCDNet and SCEM algorithms generate a substantial number of fragmented regions during the detection process. Therefore, this study assesses the alignment between the change areas detected by different methods and the actual change areas. The evaluation focuses on spatial position consistency, providing a comprehensive assessment of both accuracy and completeness.

As shown in

Table 1, the proposed method achieved an accuracy of 85.29%, a recall of 65.35%, and an F1 score of 69.56% on the change dataset, all significantly higher than those of the other two algorithms, which were each below 20%. This demonstrates that the proposed approach is more effective in identifying changes in building outlines. The comparison results are illustrated in

Figure 5.

For the unchanged image dataset, all three algorithms achieved an accuracy of 100%. However, the recall varied considerably, indicating that while each algorithm could identify unchanged areas, they were prone to missing detections by incorrectly classifying some unchanged areas as changed. Based on the overall F1 score, the proposed method outperformed the comparison algorithms in both accuracy and completeness, reaching 99.91%. The comparison results are shown in

Figure 6.

4.3.3. Results of Building Height Changes

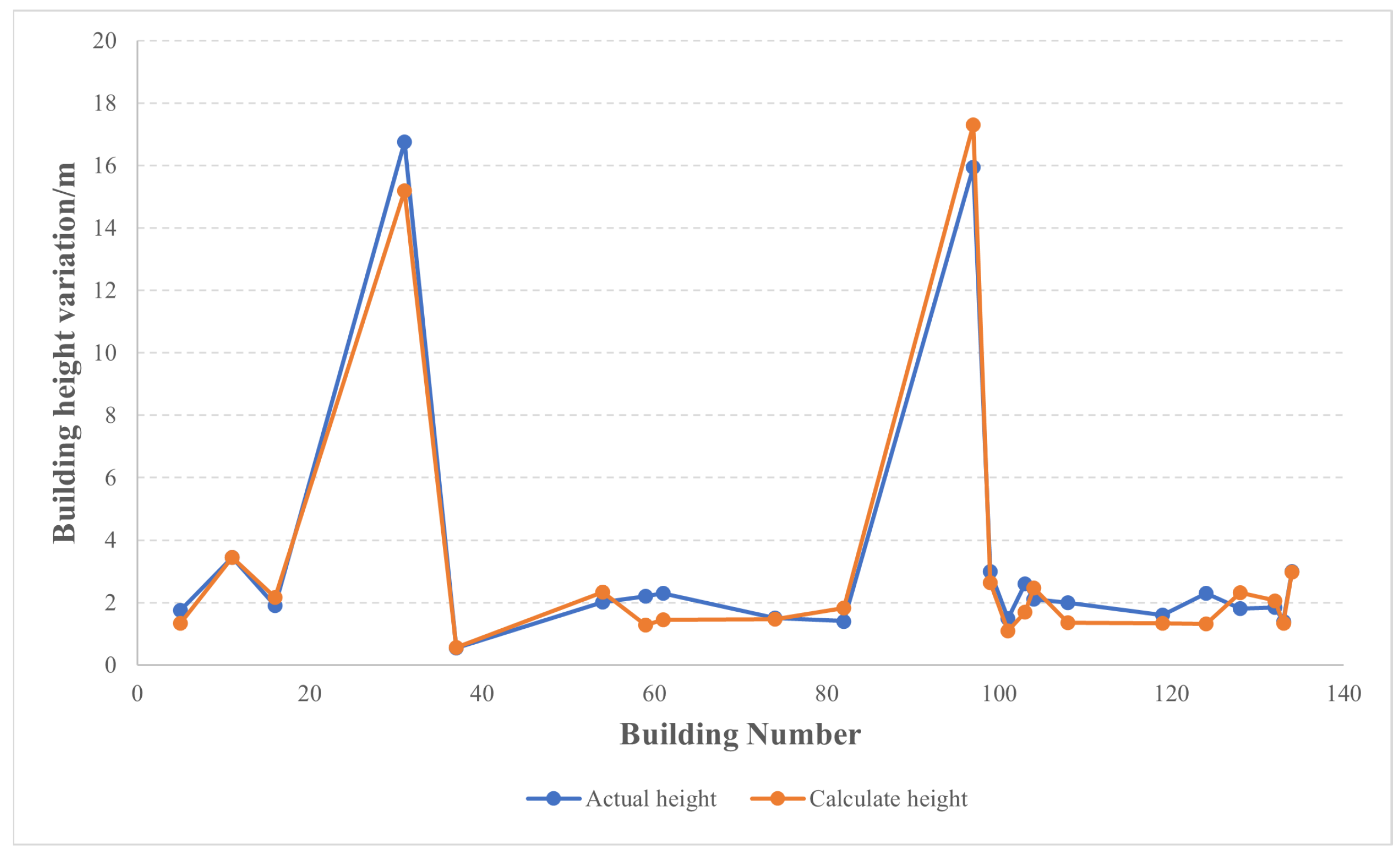

To verify the accuracy of the HCAOT algorithm in calculating changes in building height, its estimated results were compared with field measurements. As shown in

Table 2, most height changes ranged from 0.5 m to 3.5 m, while two buildings, numbered 31 and 97, showed changes exceeding 10 m. Field verification confirmed that both were newly constructed buildings. For these new buildings, their outlines were manually traced using Baidu Maps to improve the accuracy of subsequent height estimations. Overall, although the HCAOT algorithm slightly underestimated the measured values, it effectively captured the general trend of building height changes (refer

Figure 7).

In addition, the HCAOT algorithm was compared with the methods proposed by Choi et al. [

35] and Xu et al. [

23], using RMSE and NRMSE to evaluate accuracy (

Table 3). The results show that HCAOT achieved an RMSE of 0.65 m and an NRMSE of 0.04, indicating overall higher accuracy compared with the other methods.

To further assess the efficiency of the automated process, 100 repeated experiments were conducted on the building change dataset. The total time from image acquisition to height calculation was recorded and compared with manual operation (

Table 4). The findings show that automated processing takes an average of only 18 s per building, with image acquisition accounting for about 16 s. Once the images are ready, identification and height estimation require only around 2 s. Compared with manual measurements, the efficiency is significantly improved.

4.3.4. Ablation Experiment

- (1)

Ablation experiment of neighboring region resampling strategy

To verify the effectiveness of the neighboring region resampling strategy, an ablation study was conducted, with the results shown in

Table 5. Here, TCounts refers to the number of correctly detected buildings in a given category, while Counts represents the total number of buildings in that category. The comparison shows that the proposed strategy improves the detection rate for changed buildings by 8.12% and for unchanged buildings by 8.98%.

- (2)

”Pseudo-change” removal algorithm ablation experiment

Due to partial vegetation occlusion and variations in building distance, unchanged areas are often misclassified as changed regions, which reduces the correct detection rate for unchanged image pairs. To address this, the experiment was performed specifically on the unchanged image set, with results also shown in

Table 6. The proposed method increased the correct detection rate for the unchanged image set from 88.47% to 91.23%, effectively reducing the impact of false changes on detection results.

5. Discussion

In multi-temporal street-view image change detection, sampling errors and differences in imaging devices can lead to registration deviations between images, increasing the difficulty of detection. The proposed method focuses on changes in building outlines, effectively avoiding interference from factors such as lighting, color, and other ground objects. Even under imperfect registration conditions, it maintains high detection accuracy and stability. CSCDNet is more sensitive to brightness variations, often misclassifying unchanged regions as changes, which limits its generalization ability. Although SCEM can filter out interference from the sky and vegetation, it struggles with building details or brightness changes. As a result, it is prone to false detections and fragmented detection outputs.

For unchanged image pairs, the proposed method demonstrates stronger robustness against disturbances such as scale, color, and rotation, achieving higher accuracy than the two methods. In contrast, CSCDNet is more affected by external condition fluctuations, while SCEM shows instability in areas with image distortion or complex structures.

In building height change estimation, the proposed method produces results that closely match the measured values. This makes it suitable for targets with different levels of height change. Compared with existing approaches, the method by Choi, et al. is based on a pixel-level assumption that the base of a building is at the same height as the camera. It does not take into account changes in the distance between the camera and the target or the effect of occlusion, which leads to larger errors. The method by Xu, et al. uses angle-based modeling, but its linear mapping cannot handle projection distortion. In contrast, the HCAOT builds a nonlinear relationship between image height and pitch angle using cylindrical projection. It then combines this with viewing geometry to accurately estimate outline height changes, improving adaptability and accuracy for changes of different scales. Our method mainly focuses on estimating local changes. Its NRMSE is slightly higher than that of Xu et al., but it performs better in RMSE, modeling soundness, and stability. Overall, angle-based modeling is clearly more effective than pixel-based methods, and cylindrical projection better fits the imaging characteristics of panoramic images, enabling more accurate change detection and height estimation.

6. Conclusions

This study presents a method for detecting changes in building outlines and estimating height variations based on street view images. The approach aims to address the high costs, registration challenges, and limited accuracy commonly encountered when using remote sensing images for building change monitoring. The main conclusions are as follows:

- 1.

A building outline change detection method that integrates deep learning with image structural features is proposed. The method combines the SuperGlue model with a neighboring region resampling strategy to achieve initial registration. After registration, it incorporates image enhancement, edge extraction, and pseudo-change removal mechanisms. Experiments show that the method achieves identification accuracy of 85.11% for changed images and 91.23% for unchanged images, with overall performance exceeding that of the SCEM and CSCDNet methods.

- 2.

A building height estimation model is developed based on cylindrical projection and triangulation. The model integrates boundary searching, projection distortion compensation, and building spacing measurement strategies. It effectively captures the nonlinear relationship between image pixels and spatial angles. As a result, it enables high-accuracy estimation of local building height changes.

- 3.

Compared with traditional manual measurement, the proposed method processes each building in about 18 s on average, greatly reducing the operational cycle. This efficiency meets the requirements for rapid change detection and height estimation in large-scale scenarios.

Despite the achievements of this study, there is still room for improvement in image registration and contour extraction. Future work will further explore the integration of texture and structural features, which can be combined with semantic segmentation and image matching techniques to improve robustness under varying viewpoints and illumination conditions. In addition, the proposed method will be validated over larger spatial extents and under more complex baseline conditions as more data become available. With the continuous growth of street view imagery and multi-source spatial data, the proposed approach shows strong potential for applications in urban dynamic monitoring, building change analysis, and spatial modeling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.C.; methodology, X.C.; software, X.C.; validation, X.C. and Q.G.; investigation, X.C. and Q.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.G.; writing—review and editing, J.D.; visualization, Q.G.; supervision, J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42172330.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers for their helpful and constructive reviews of the manuscript. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42172330). During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT-5 to improve the language. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xiaoyan Chen was employed by the company United Imaging NMRSpec Scientific Instrument (Wuhan) Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HCAOT | a triangulation-based method for height estimation |

| DSM | Digital surface models |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| GIS | Geographic information system |

| NCC | Normalized cross-correlation |

| Cheight | Building height change |

| OSM | OpenStreetMap |

References

- Ren, C.; Cai, M.; Li, X.; Shi, Y.; See, L. Developing a rapid method for 3-dimensional urban morphology extraction using open-source data. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 53, 101962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Miao, P.; Wang, Y. Application of 3D laser point cloud data in urban building height monitoring. Geomat. Spat. Inf. Technol. 2023, 46, 212–213. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, H.; Samadzadegan, F. An object based framework for building change analysis using 2D and 3D information of high resolution satellite images. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 66, 1386–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, P.; Guo, J.; Li, R.; Xiao, Z.; Fu, H.; Guo, T.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Song, X. Automated building height estimation using Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellite 2 light detection and ranging data and building footprints. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Wang, J.; Zhan, W.; Shi, P.; Gambles, A. An elevation difference model for building height extraction from stereo-image-derived DSMs. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2014, 35, 7614–7630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.; Hu, X.; Wang, Z.; Lu, Y. Object-based analysis of airborne LiDAR data for building change detection. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 10733–10749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Hao, M.; Shi, W. Building change detection using a shape context similarity model for lidar data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Huang, H.; Zhao, Y. Utilizing building offset and shadow to retrieve urban building heights with ICESat-2 photons. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhong, T.; Yeh, A.G.O.; Zhong, X.; Chen, M.; Lü, G. Mapping seasonal changes of street greenery using multi-temporal street-view images. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 92, 104498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Effect of people on placemaking and affective atmospheres in city streets. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 3389–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Du, M.; Zhao, W.; Hu, Y.; Mo, Y.; Chen, S.; Cai, Y.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, C. Multi-level monitoring of three-dimensional building changes for megacities: Trajectory, morphology, and landscape. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 167, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lv, X.; Zhang, K.; Guo, B. Building change detection based on 3D co-segmentation using satellite stereo imagery. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhou, X.G.; Hou, D.Y. A method for determining height difference threshold in 3D building change detection based on normal distribution. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 2021, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentz, E.A.; York, A.M.; Alberti, M.; Conrow, L.; Fischer, H.; Inostroza, L.; Jantz, C.; Pickett, S.T.A.; Seto, K.C.; Taubenböck, H. Six fundamental aspects for conceptualizing multidimensional urban form: A spatial mapping perspective. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 179, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcantarilla, P.F.; Stent, S.; Ros, G.; Arroyo, R.; Gherardi, R. Street-view change detection with deconvolutional networks. Auton. Robot. 2018, 42, 1301–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.Z.; Chen, H.H. A method for street view change detection based on crowdsensing. Appl. Res. Comput. 2022, 39, 3186–3190. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurada, K.; Wang, W.; Kawaguchi, N.; Nakamura, R. Dense optical flow based change detection network robust to difference of camera viewpoints. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.02941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, R.; Lei, Y.J.; Chen, X.M.; Ye, S.H. Street view change detection based on multiple differential feature network. Comput. Sci. 2021, 48, 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, S.; Zhang, X.R.; Wang, B.; Li, J.; Cao, W.W.; Qiao, G.Z. A method for street view image change detection integrating multi-feature information. Comput. Technol. Dev. 2023, 33, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, H.; Li, Z.; Ye, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Huang, X. Exploring the vertical dimension of street view image based on deep learning: A case study on lowest floor elevation estimation. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2022, 36, 1317–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Habashna, A.; Murdoch, R. Building height estimation from street-view imagery using deep learning, image processing and automated geospatial analysis. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 53065–53093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Che, X. A method for estimating building height from street view images. Remote Sens. Inf. 2024, 39, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y. Building height calculation for an urban area based on street view images and deep learning. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2023, 38, 892–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.X.; Qi, J.Z.; Korn, F.; Wang, X.Y. Scalable building height estimation from street scene images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.W.; Chen, C.X.; Liu, X.Y.; Wu, Y.T.; Chen, S.L. Research on the spatial effect of urban street aging-friendly level combining street view images and machine learning. J. -Geo-Inf. Sci. 2024, 26, 1469–1485. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, M.; Aizawa, K. Identification of buildings in street images using map information. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Taipei, Taiwan, 22–25 September 2019; pp. 984–988. [Google Scholar]

- Roussel, R.; Jacoby, S.; Asadipour, A. Robust building identification from street views using deep convolutional neural networks. Buildings 2024, 14, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Yang, S.; Zan, X.; Dong, X.; Yao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X. Flood vulnerability assessment of urban buildings based on integrating high-resolution remote sensing and street view images. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 92, 104467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the CVPR, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Xiang, J.; Jiang, J.; Yan, E.; Wei, W.; Mo, D. A Cross-Domain Change Detection Network Based on Instance Normalization. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shi, Z. A Spatial-Temporal Attention-Based Method and a New Dataset for Remote Sensing Image Change Detection. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Wei, S.; Lu, M. Fully Convolutional Networks for Multisource Building Extraction From an Open Aerial and Satellite Imagery Data Set. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurada, K.; Shibuya, M.; Wang, W. Weakly supervised silhouette-based semantic scene change detection. In Proceedings of the ICRA, Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 6861–6867. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Lei, L.; Kuang, G. Change detection of heterogeneous optical and SAR images based on structural consistency energy model. Sci. Sin. Inf. 2023, 53, 2016–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Lim, W.; Chang, B.; Jeong, J.; Kim, I.; Park, C.-R.; Ko, D.W. An automatic approach for tree species detection and profile estimation of urban street trees using deep learning and Google street view images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 190, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |