Dust Dispersion Mechanisms and Rail-Mounted Local Purification in Drill-and-Blast Tunnel Construction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Model and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Background of Dust Generation and Transport

2.2. Numerical Model Development

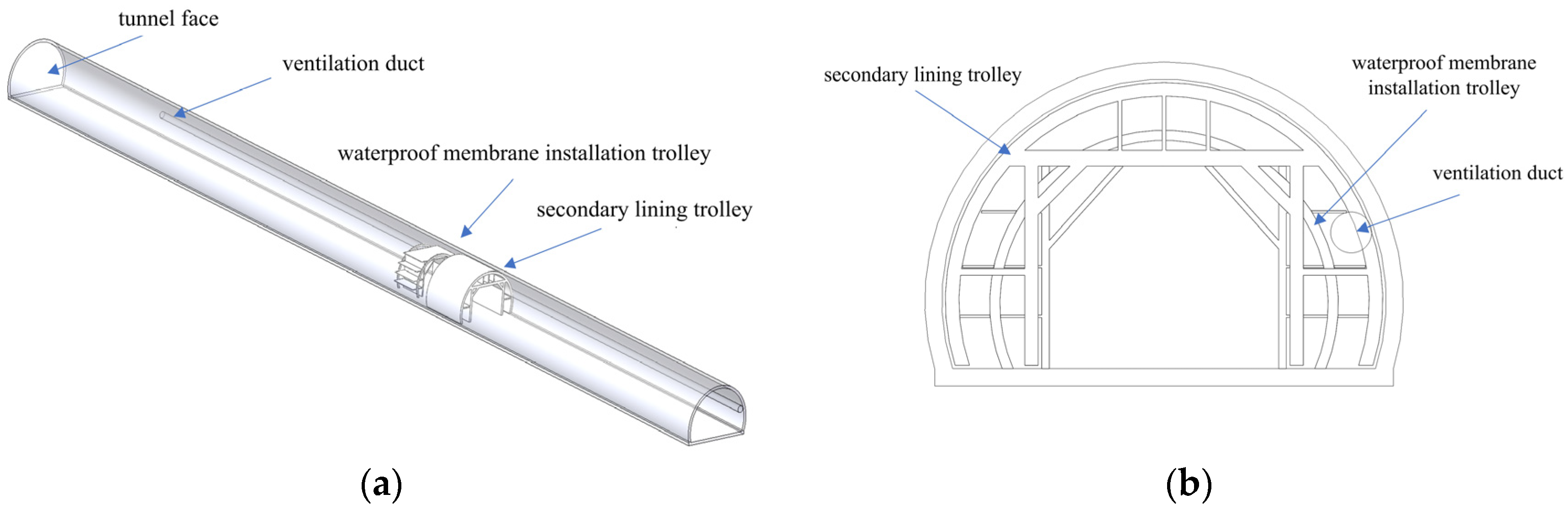

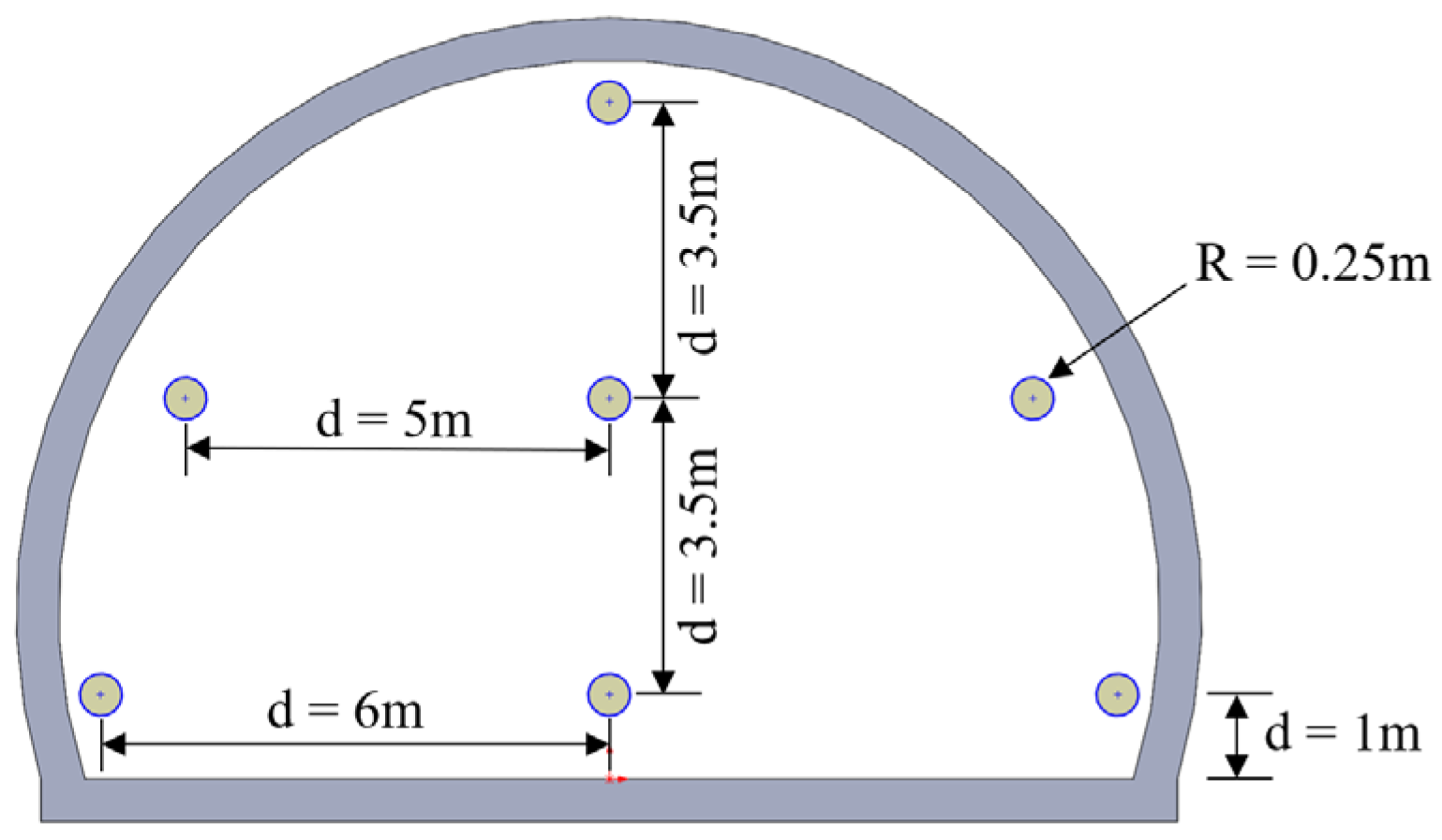

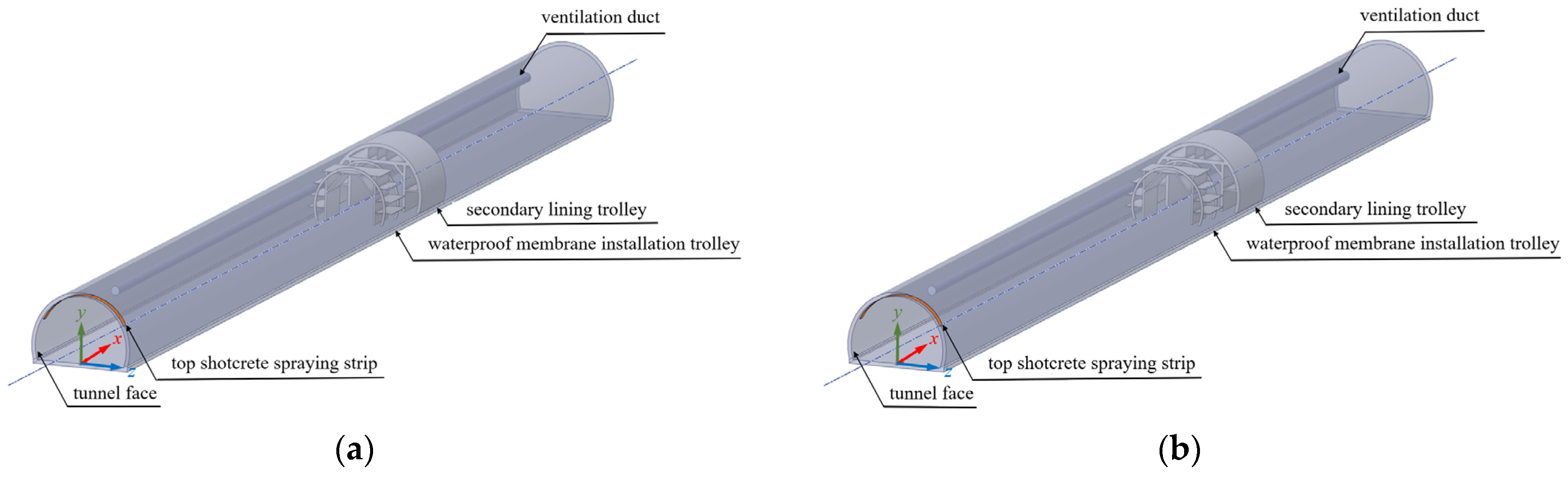

2.2.1. Geometric Model and Physical Assumptions

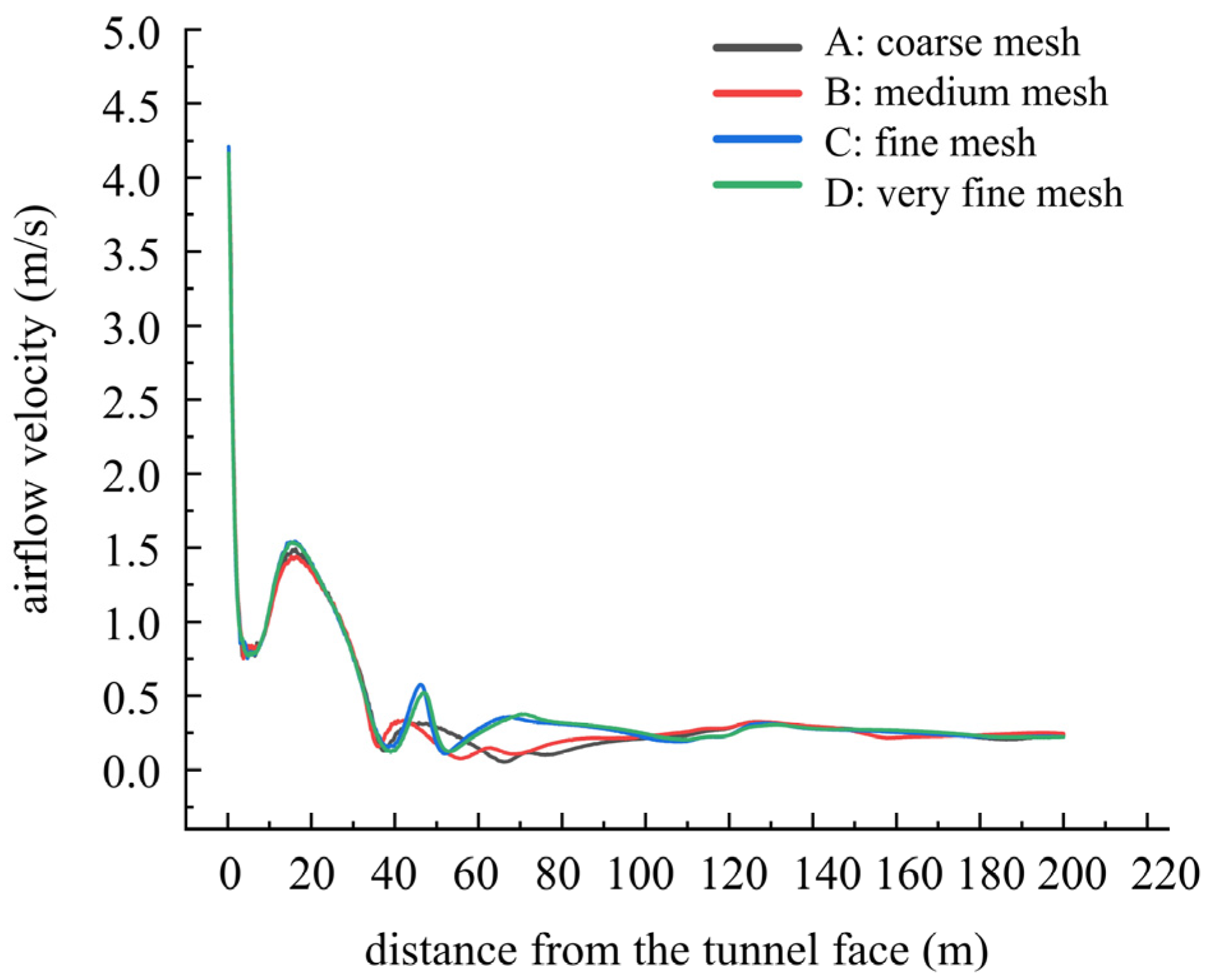

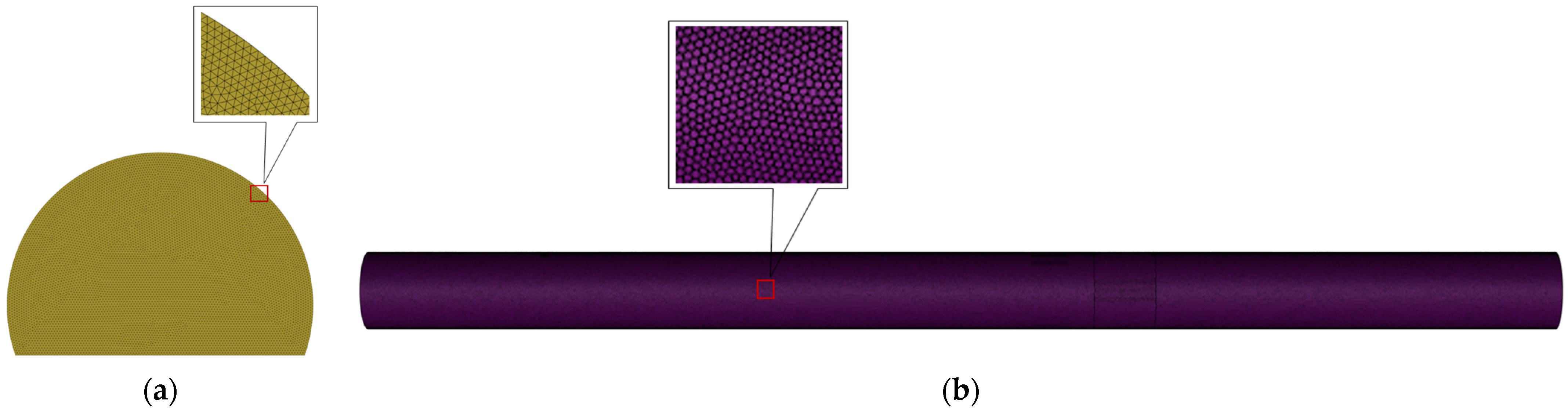

2.2.2. Mesh Generation and Independence Study

2.2.3. Benchmarking Strategy for Model Validation

2.3. Initial and Boundary Conditions

2.3.1. Initial Airflow and Source Terms

- (1)

- Drilling dust source

- (2)

- Blasting dust source

- (3)

- Shotcreting dust source

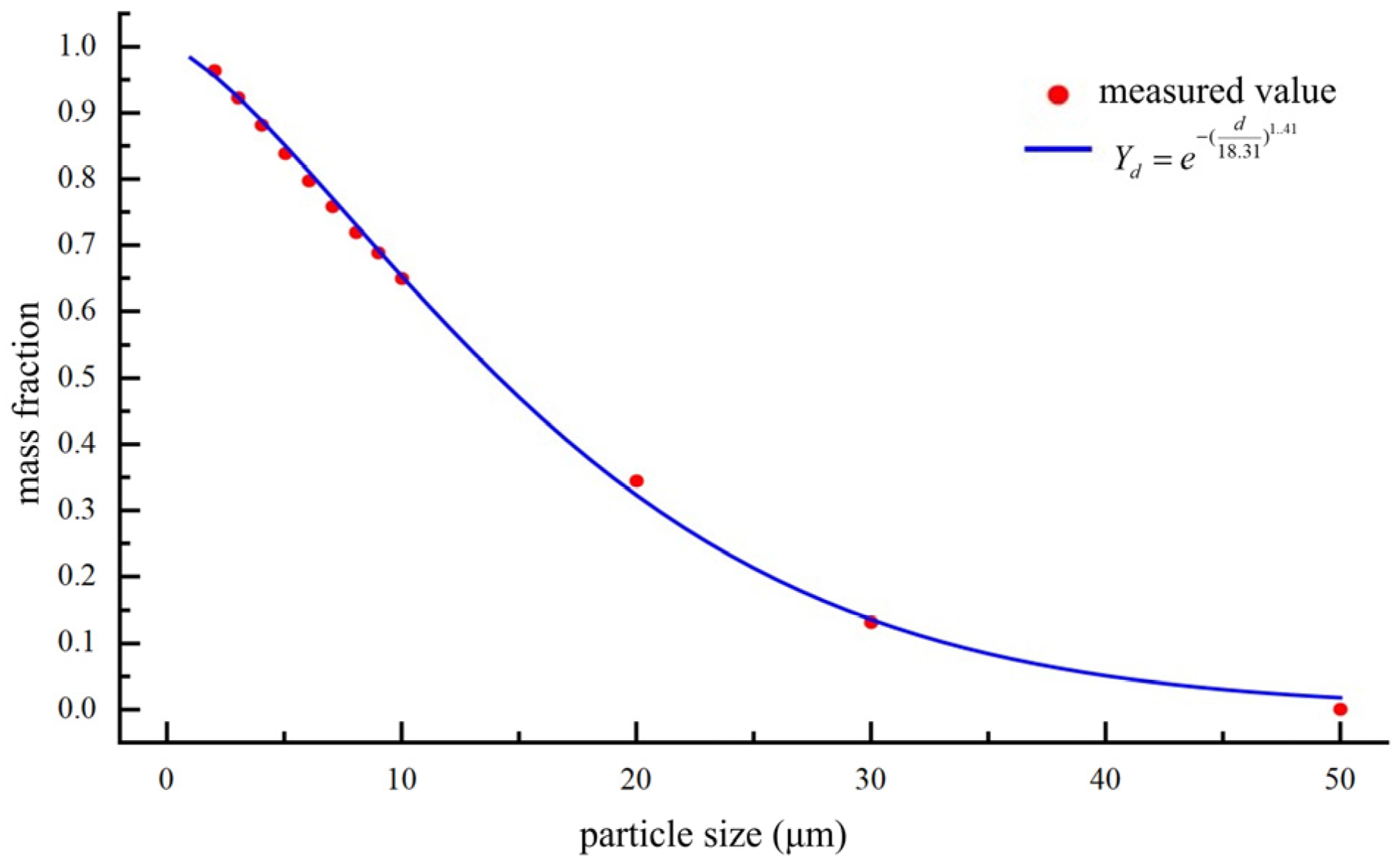

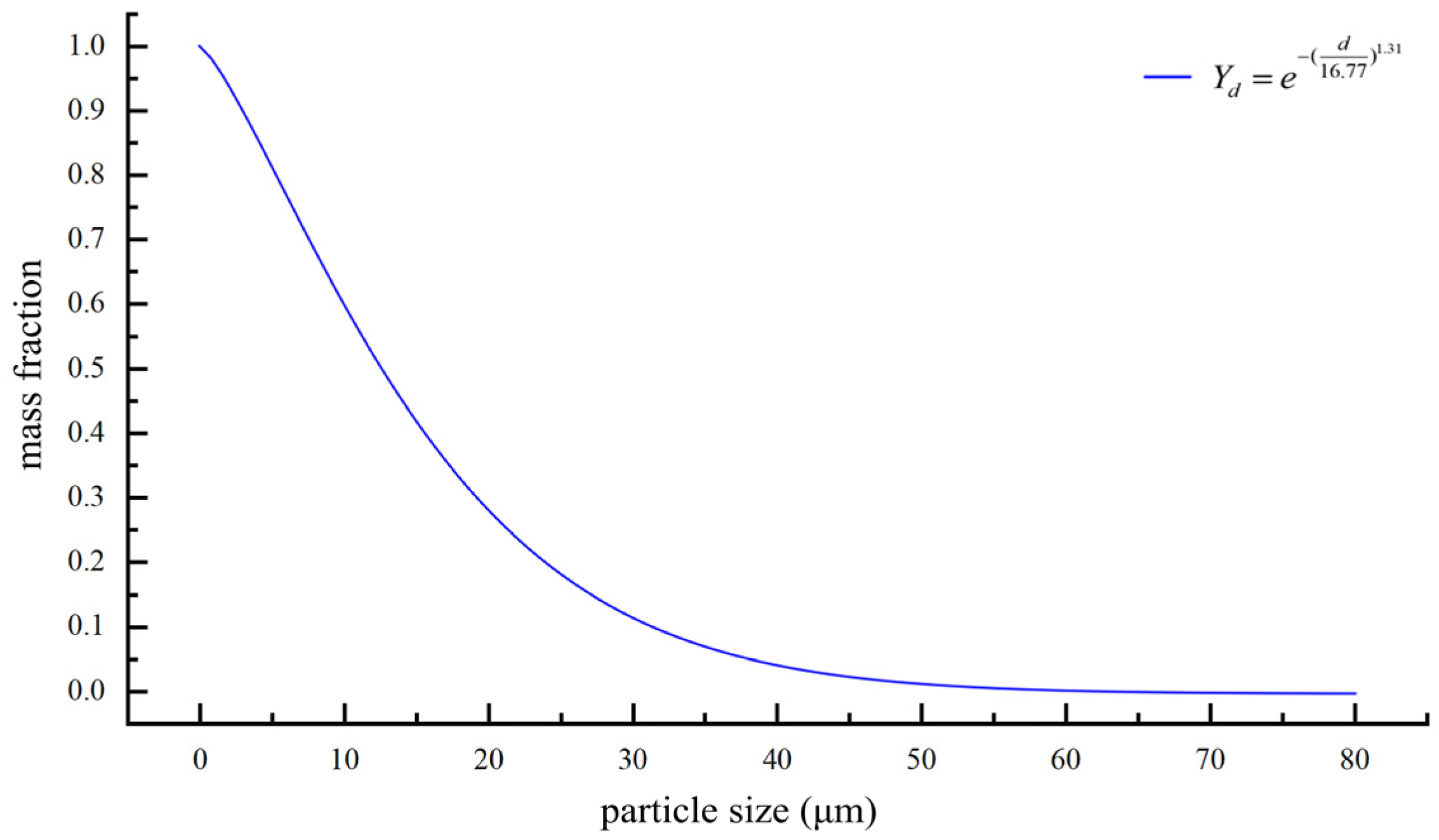

2.3.2. Particle-Size Distribution and Dust Source Parameters

2.3.3. Boundary Conditions

2.4. Solver Settings

2.5. Simulation Scenarios

- (1)

- Drilling scenario

- (2)

- Blasting scenario

- (3)

- Shotcreting scenario

3. Dust Dispersion Characteristics and Evolution

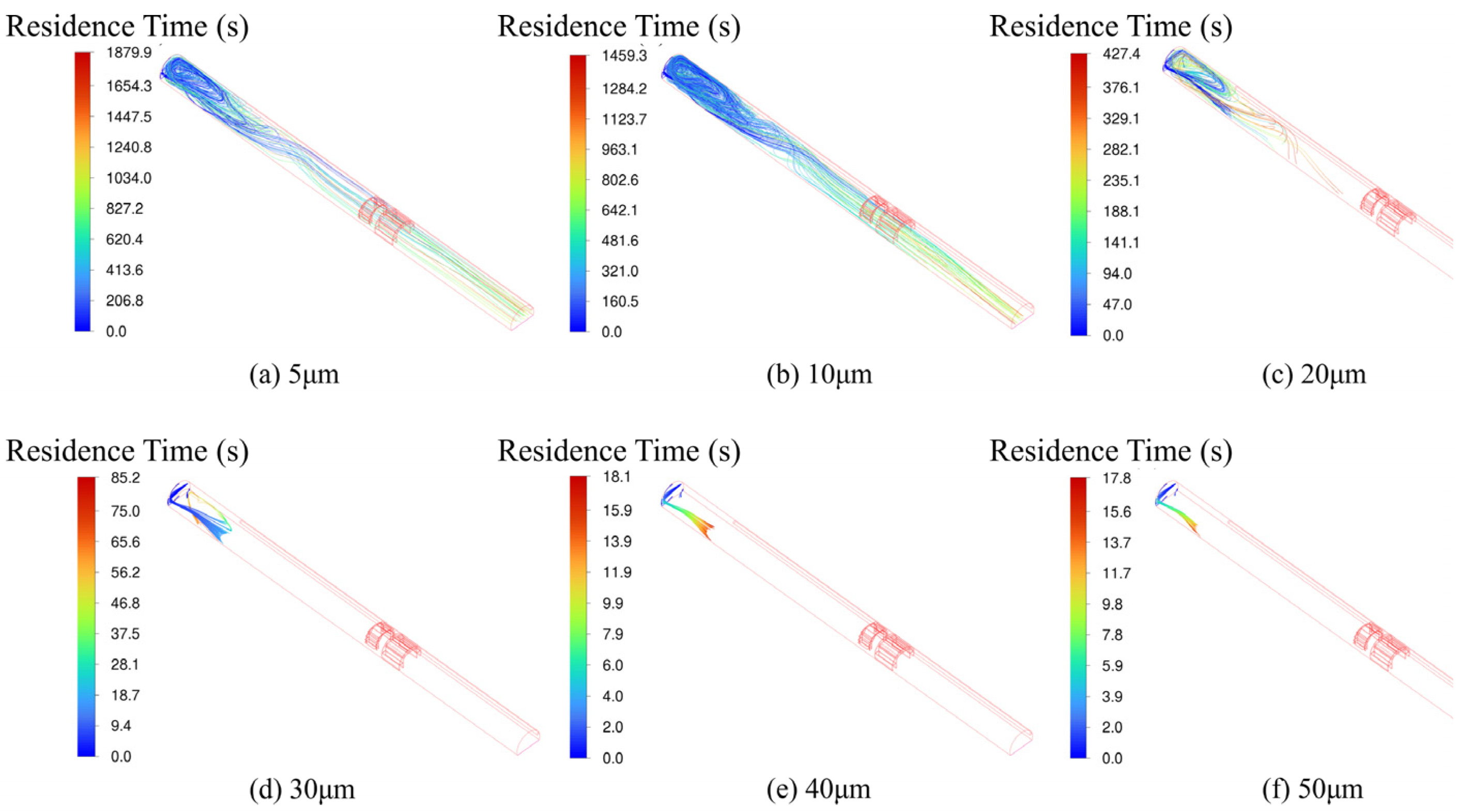

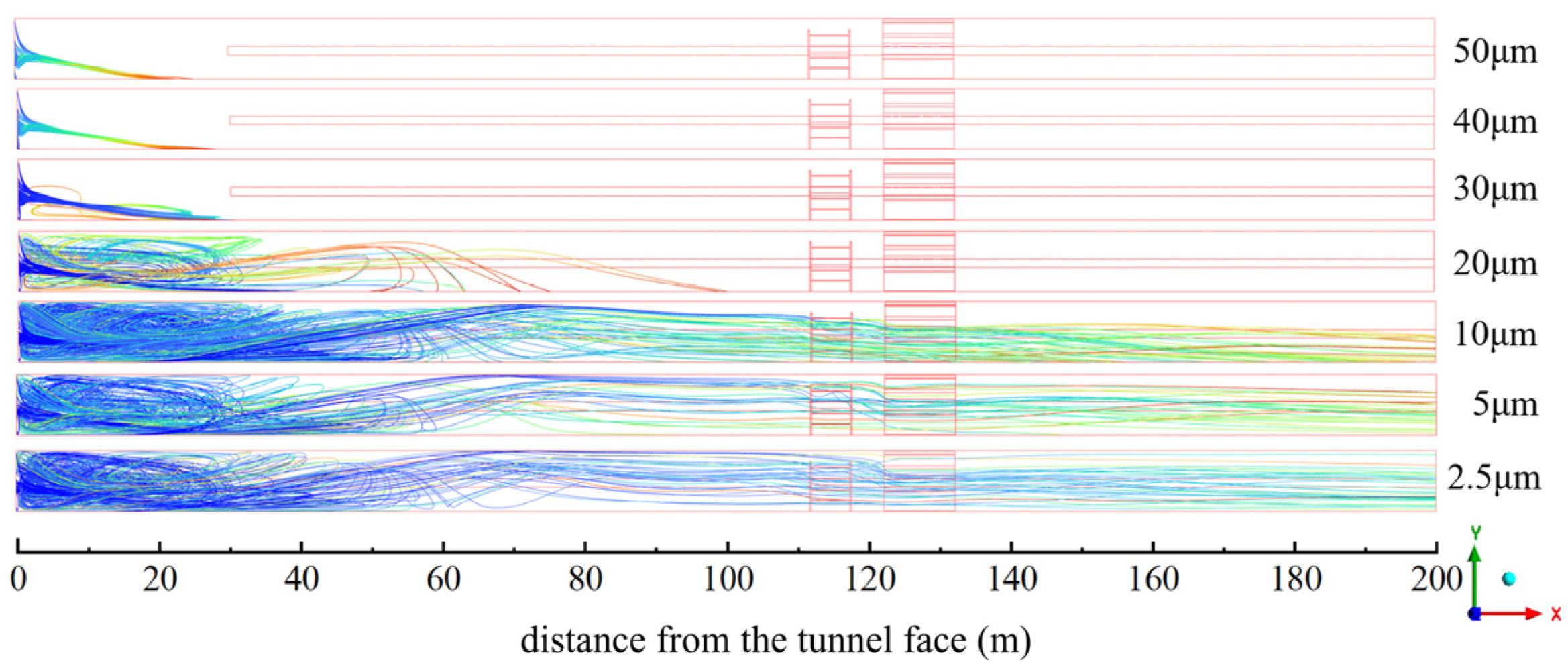

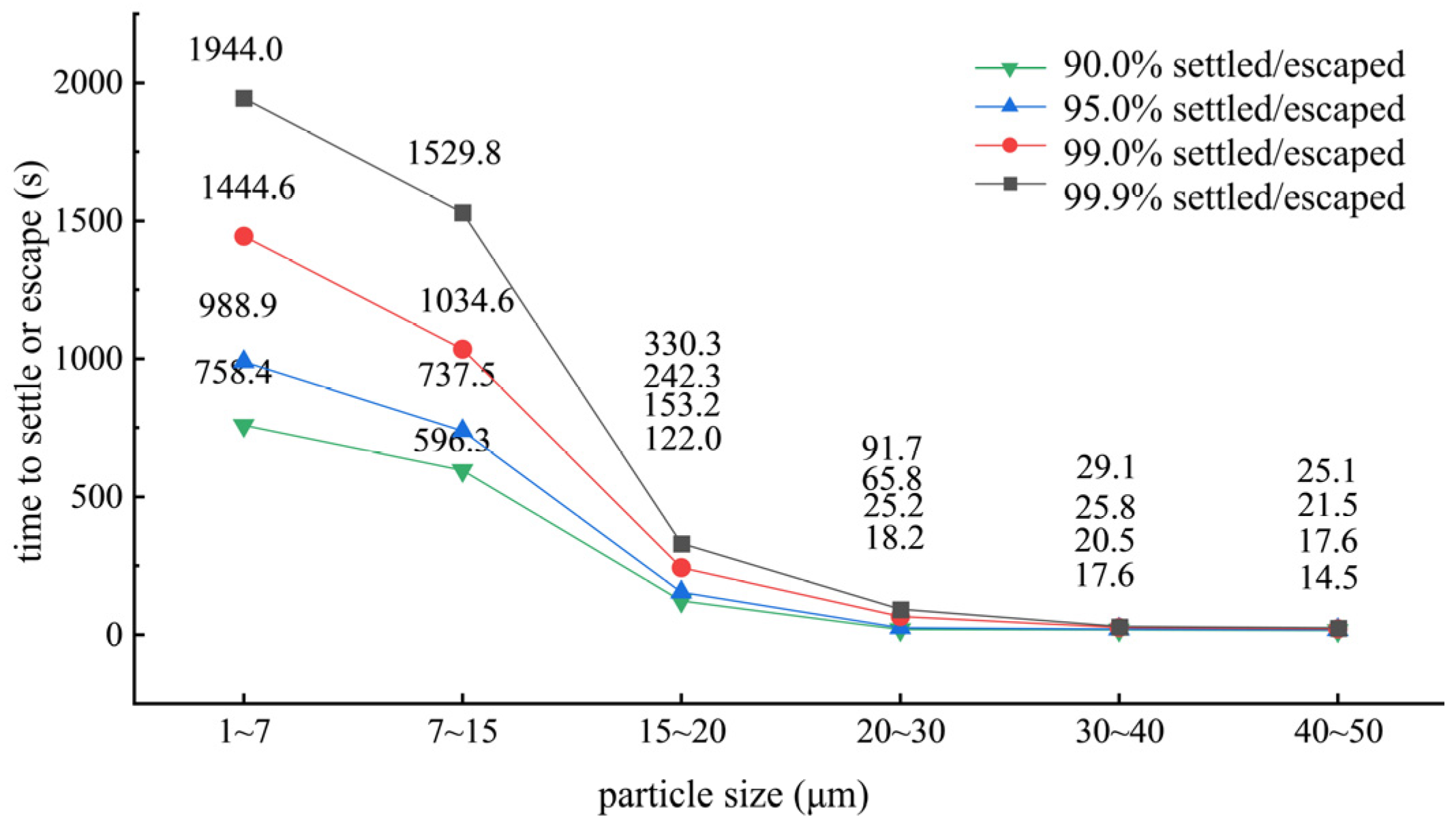

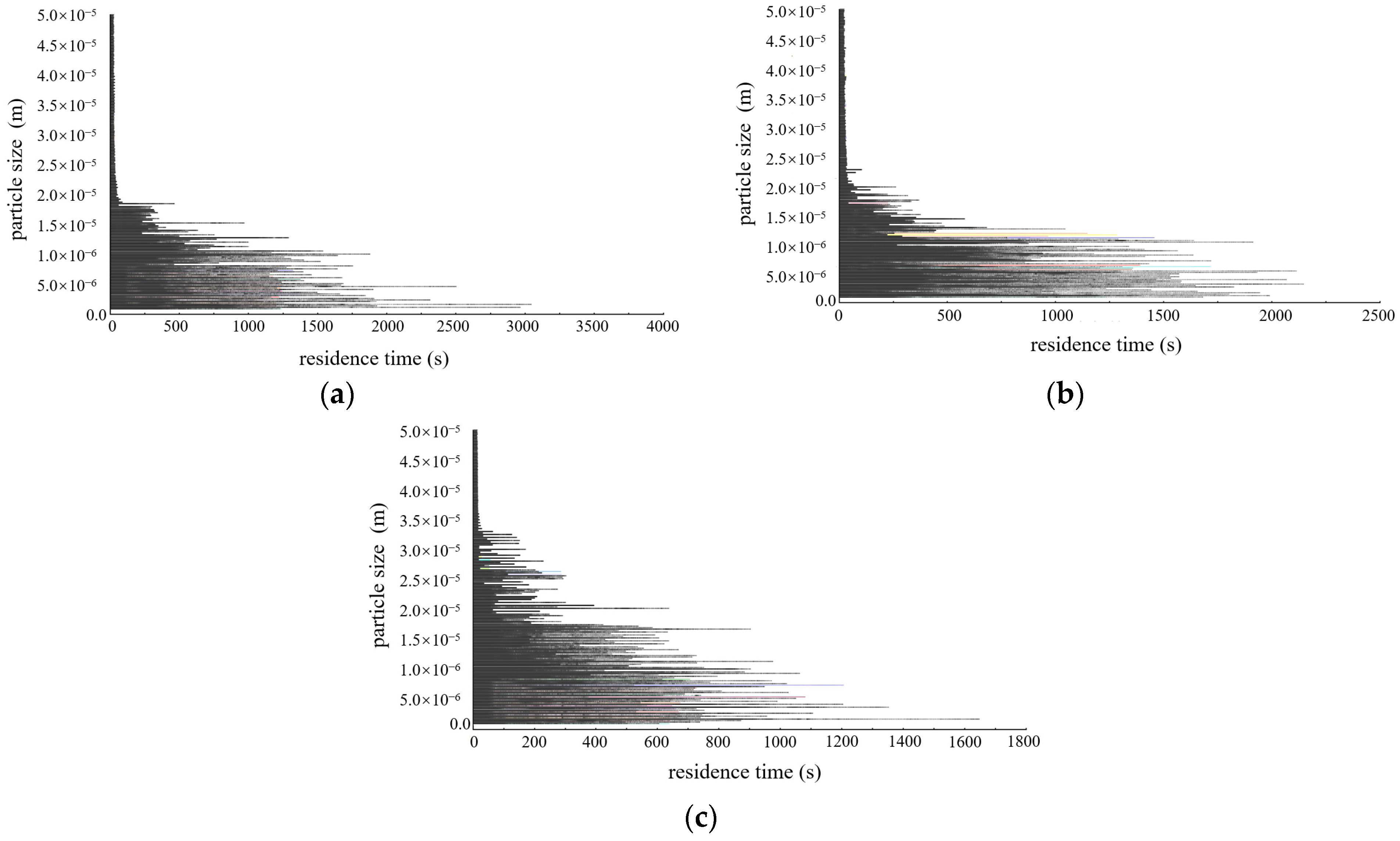

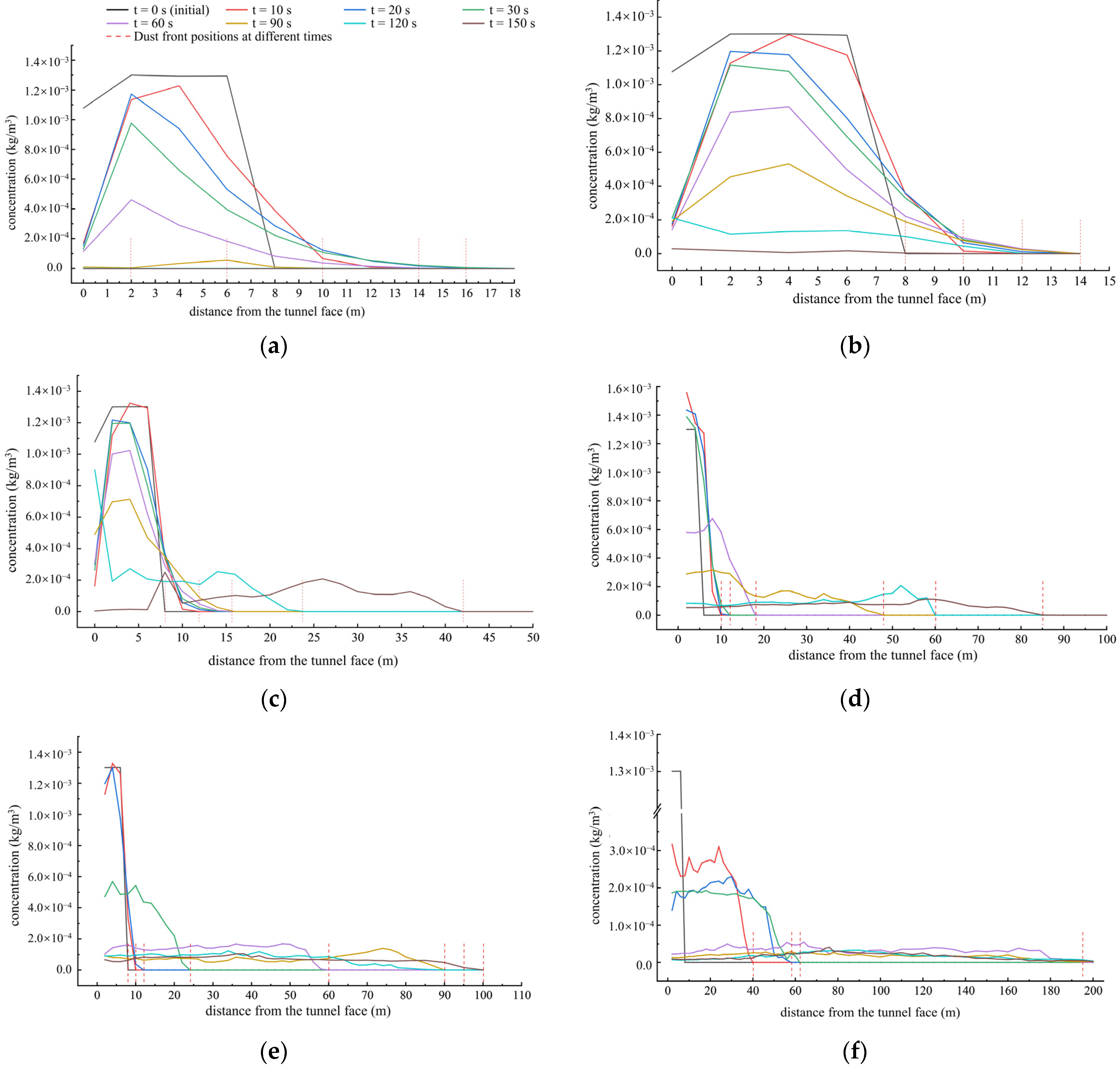

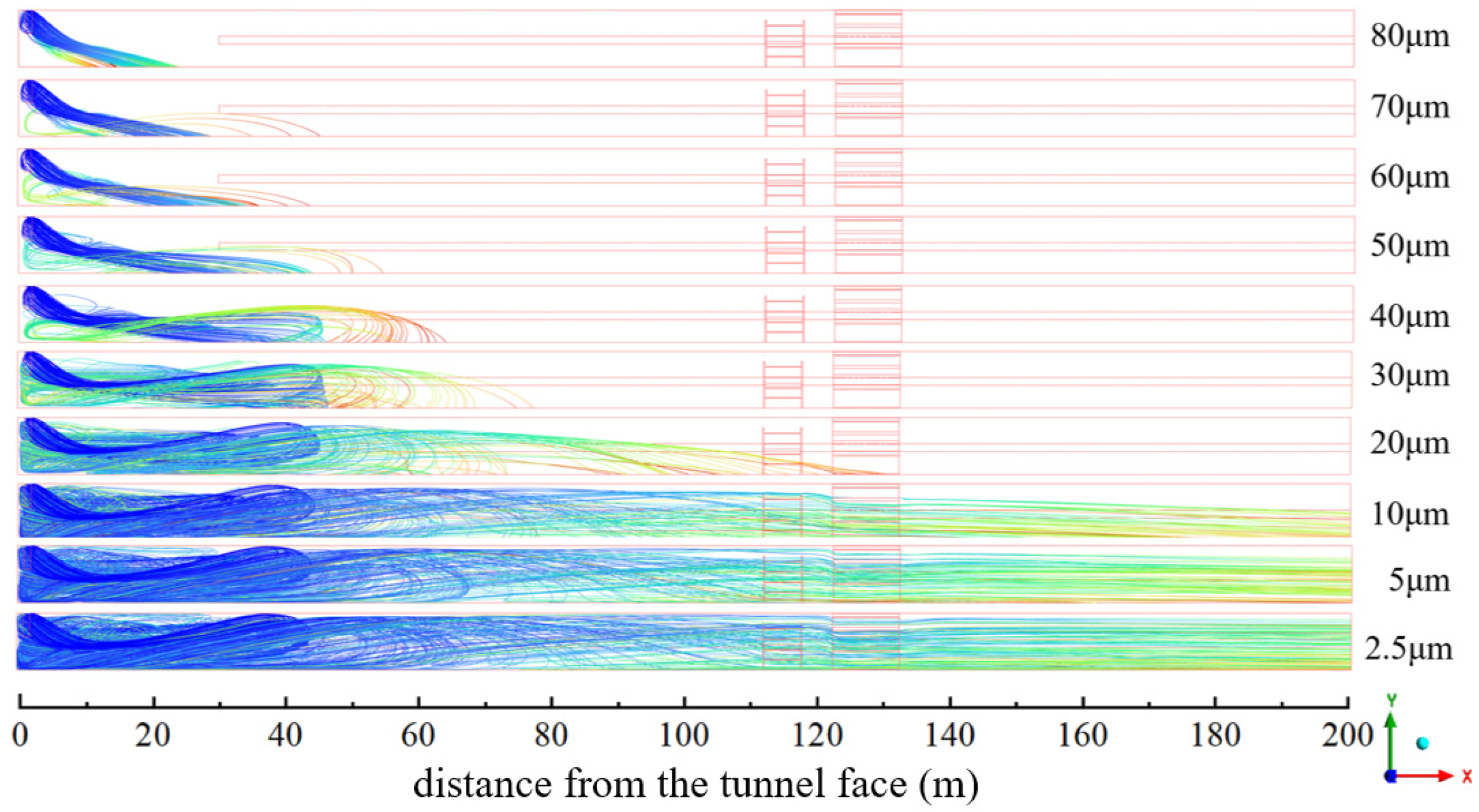

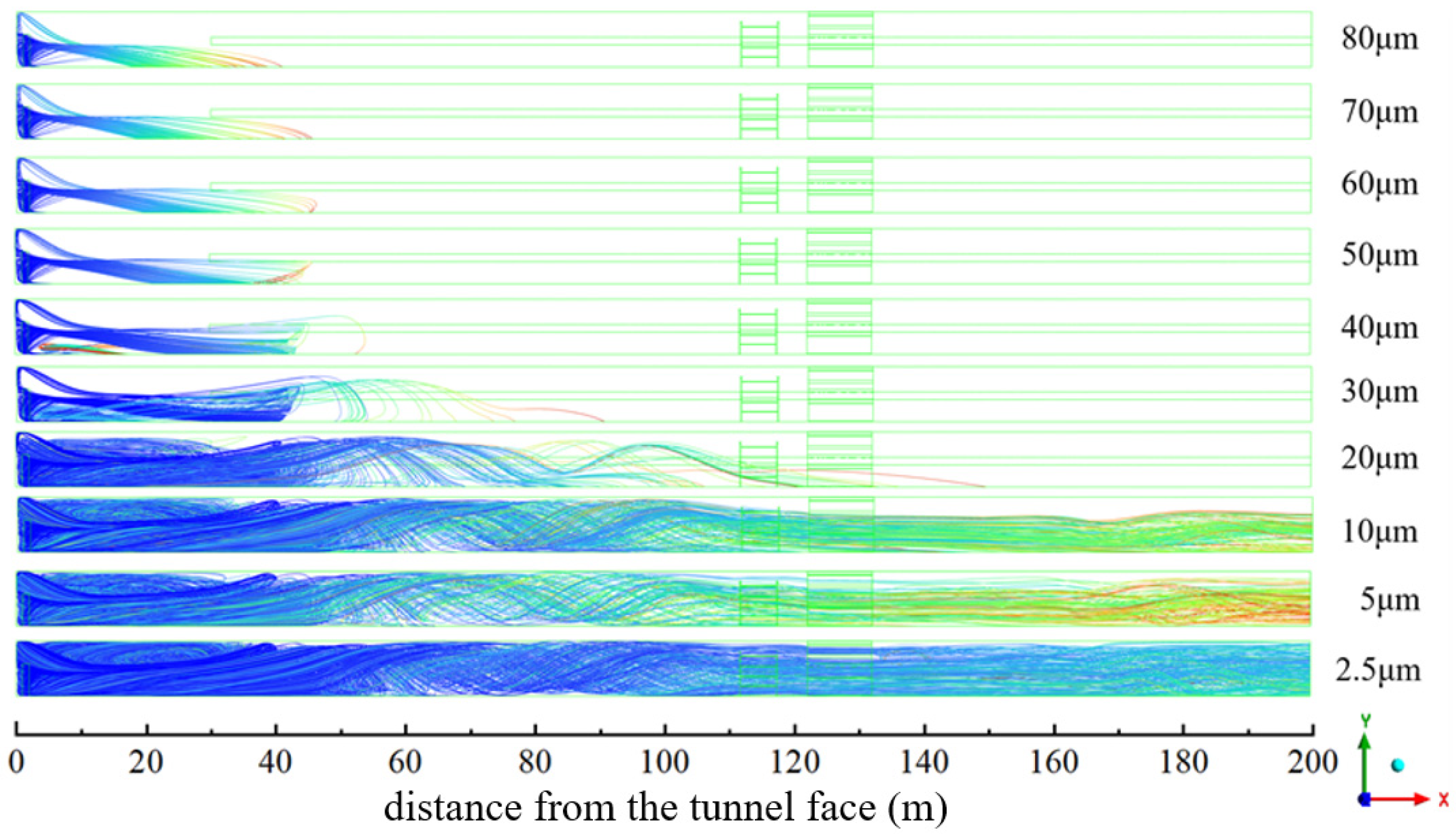

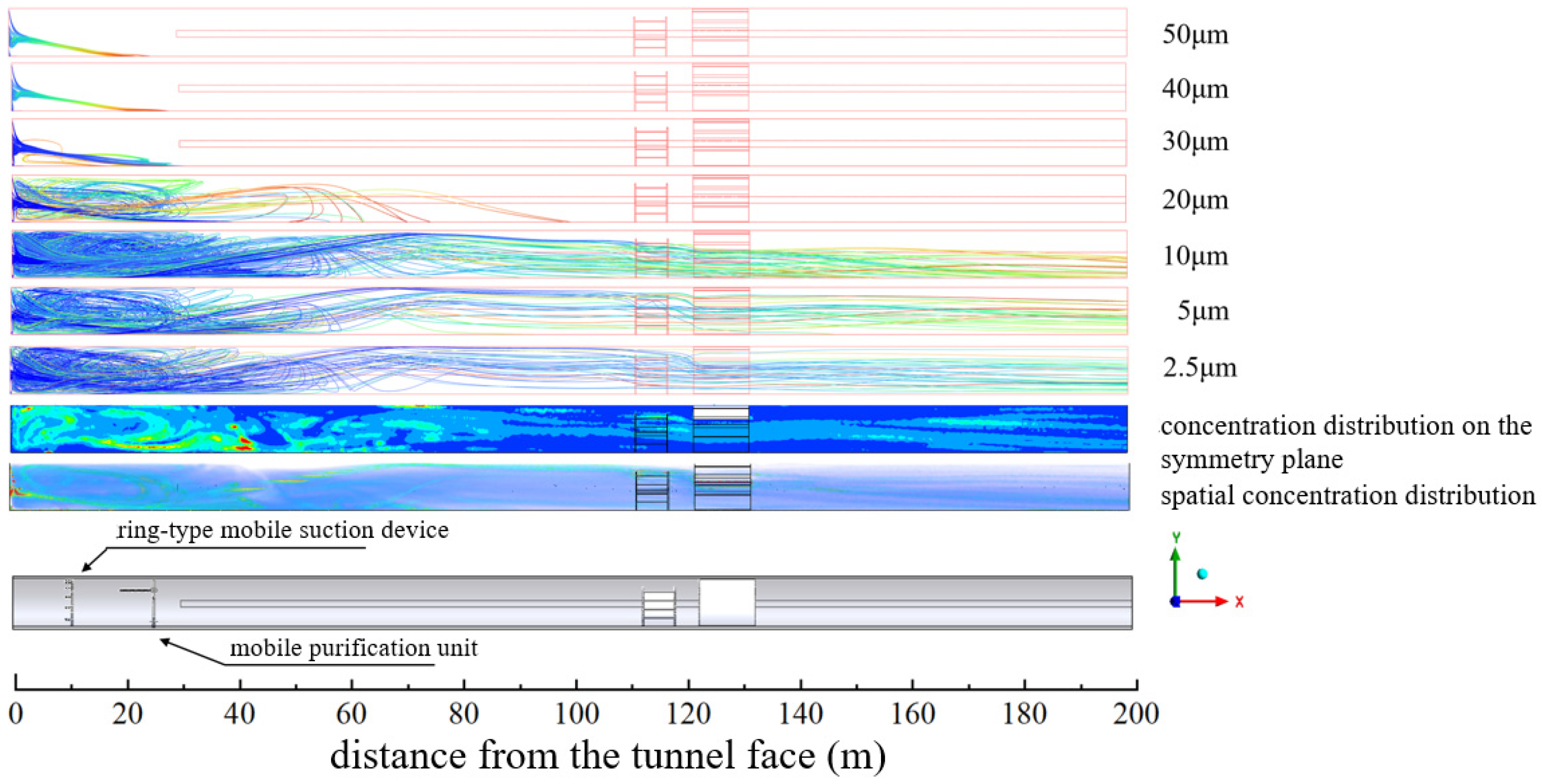

3.1. Dust Dispersion During the Drilling Process

3.1.1. Spatial Distribution

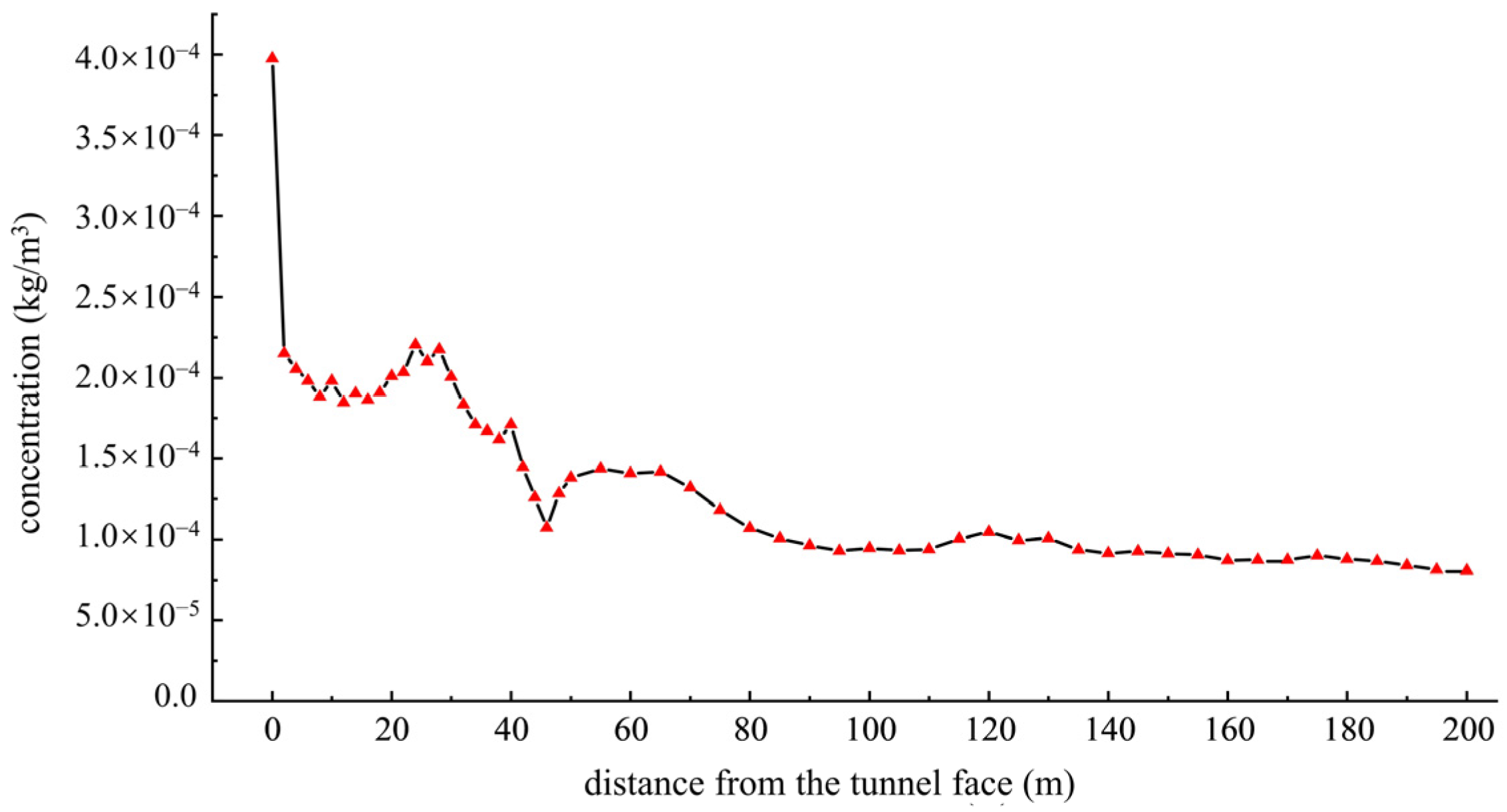

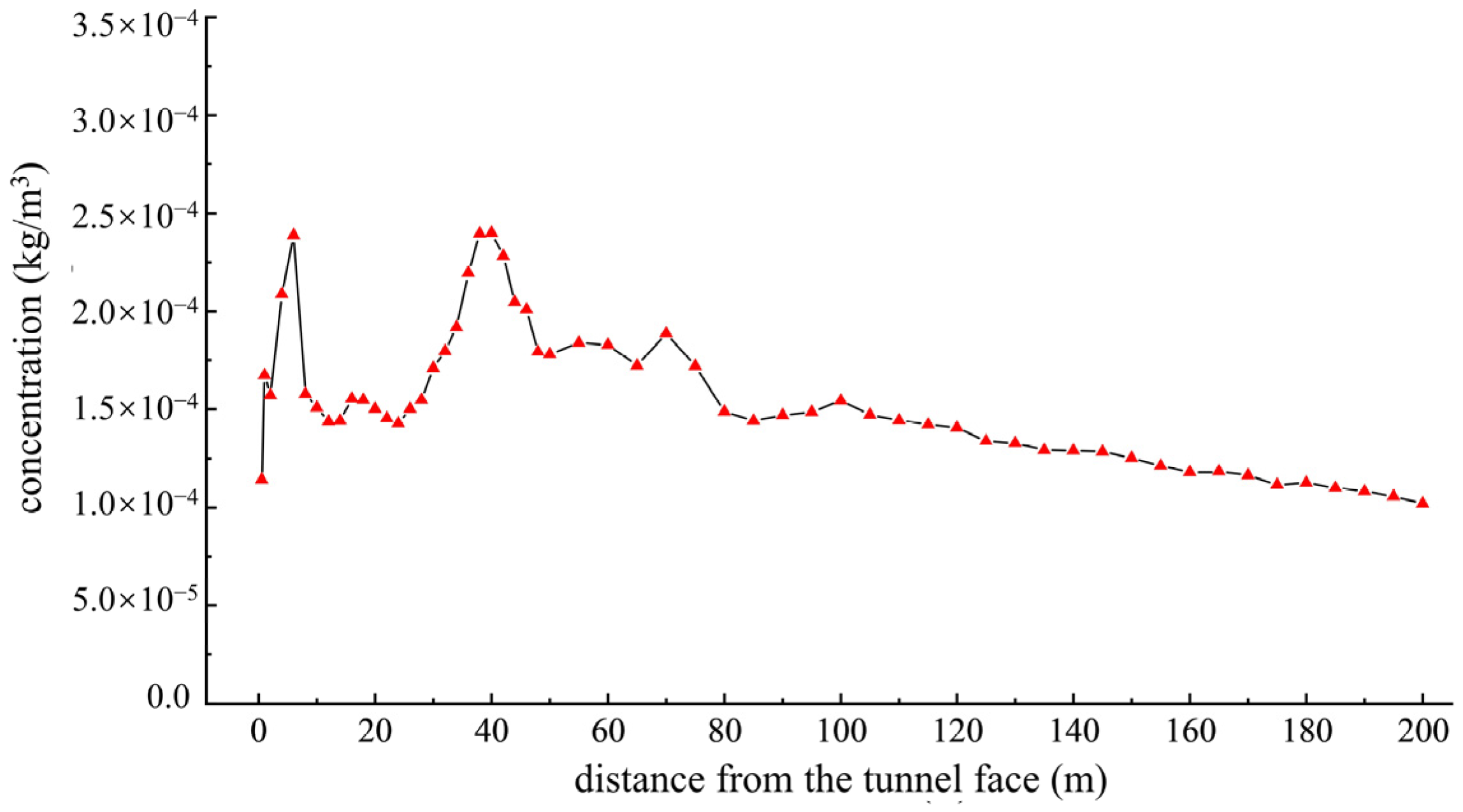

3.1.2. Longitudinal Variation

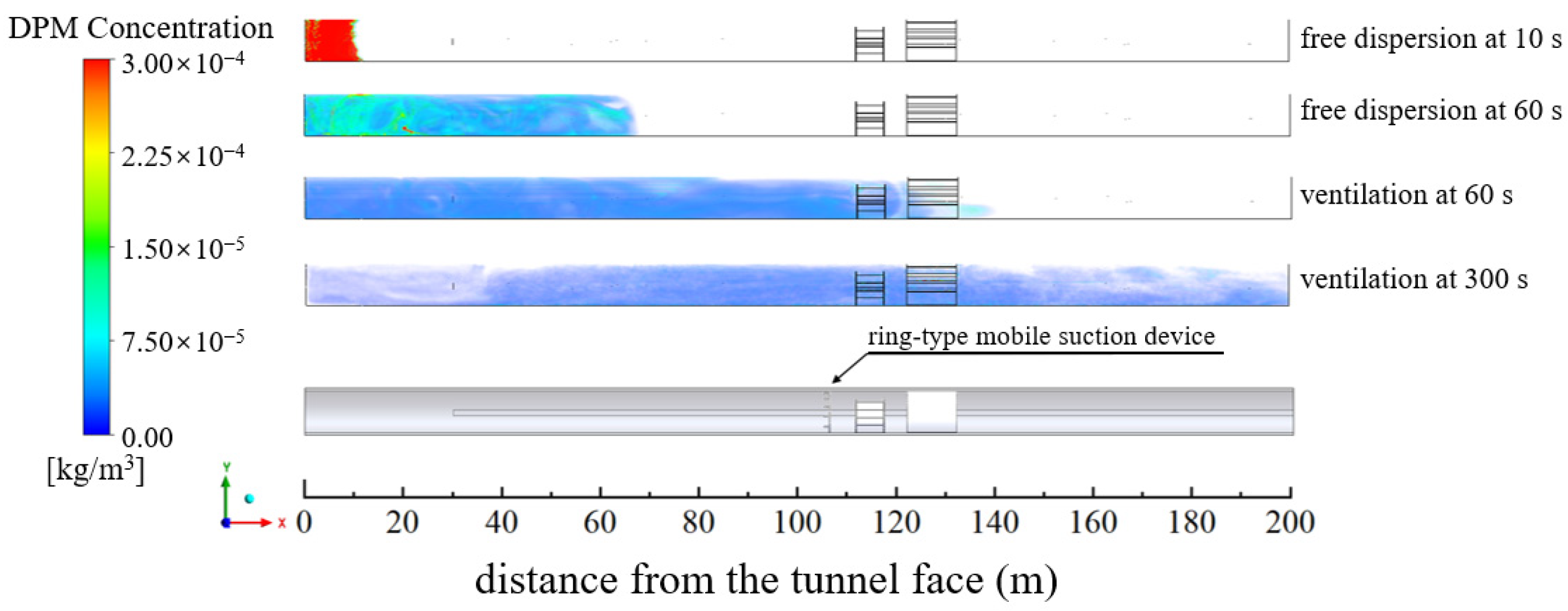

3.2. Dust Dispersion During the Blasting Process

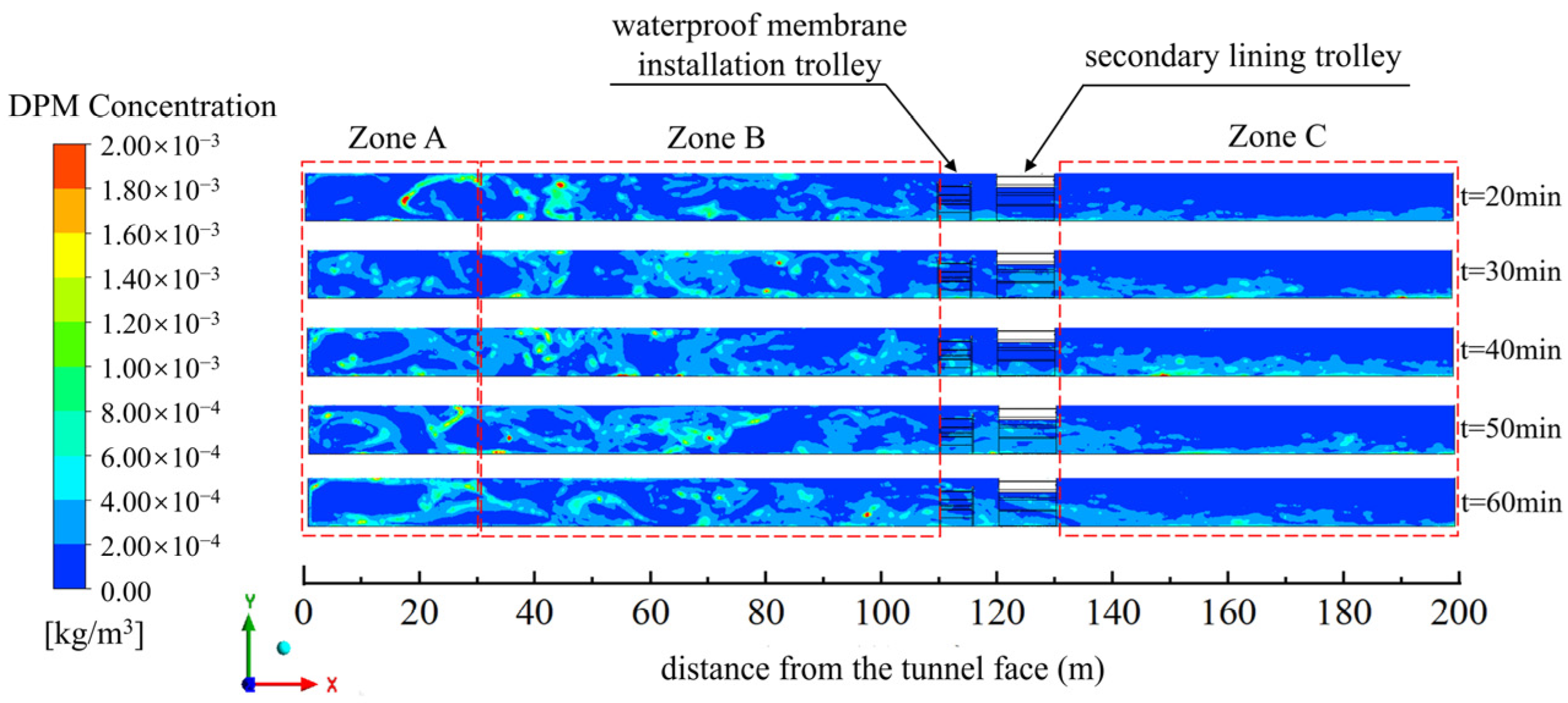

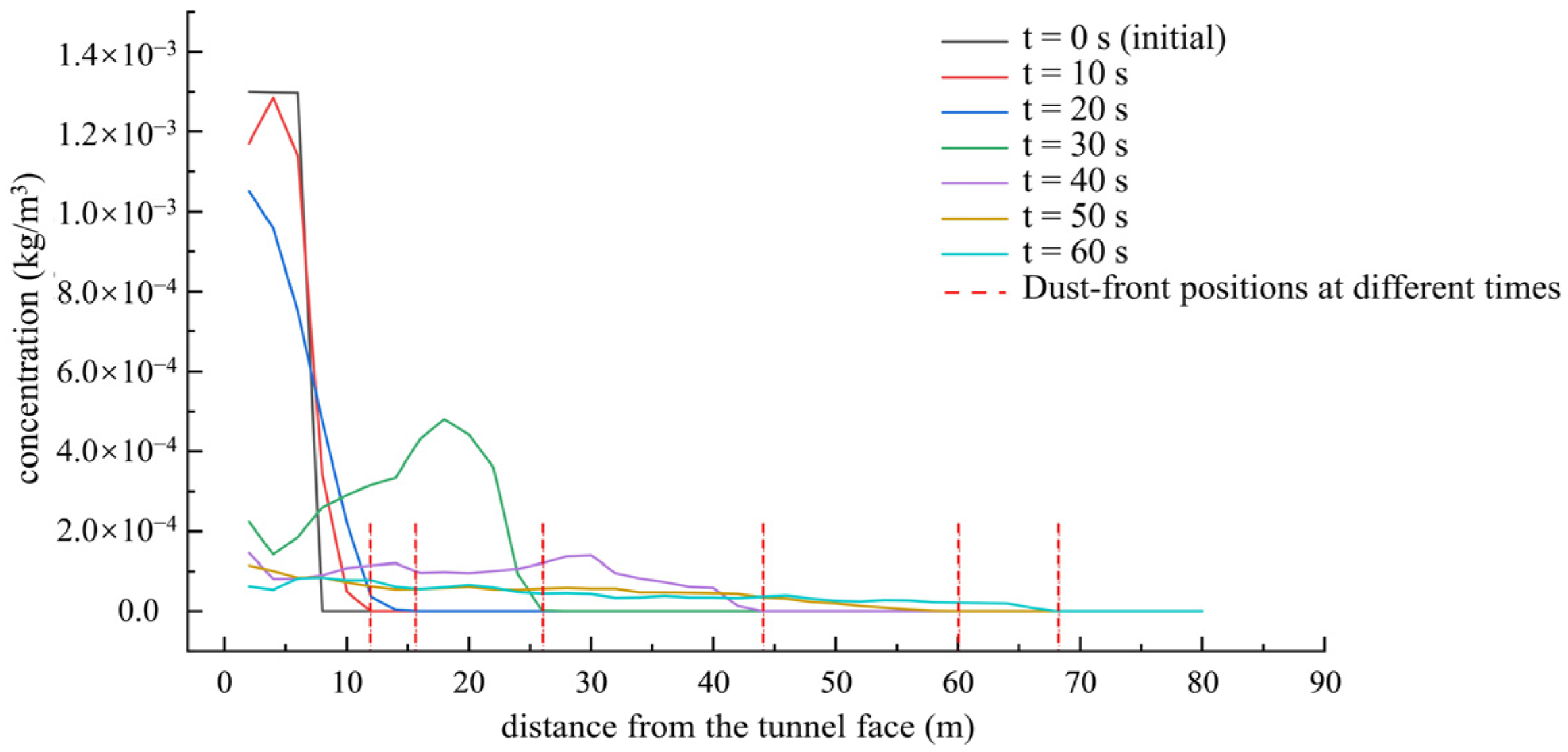

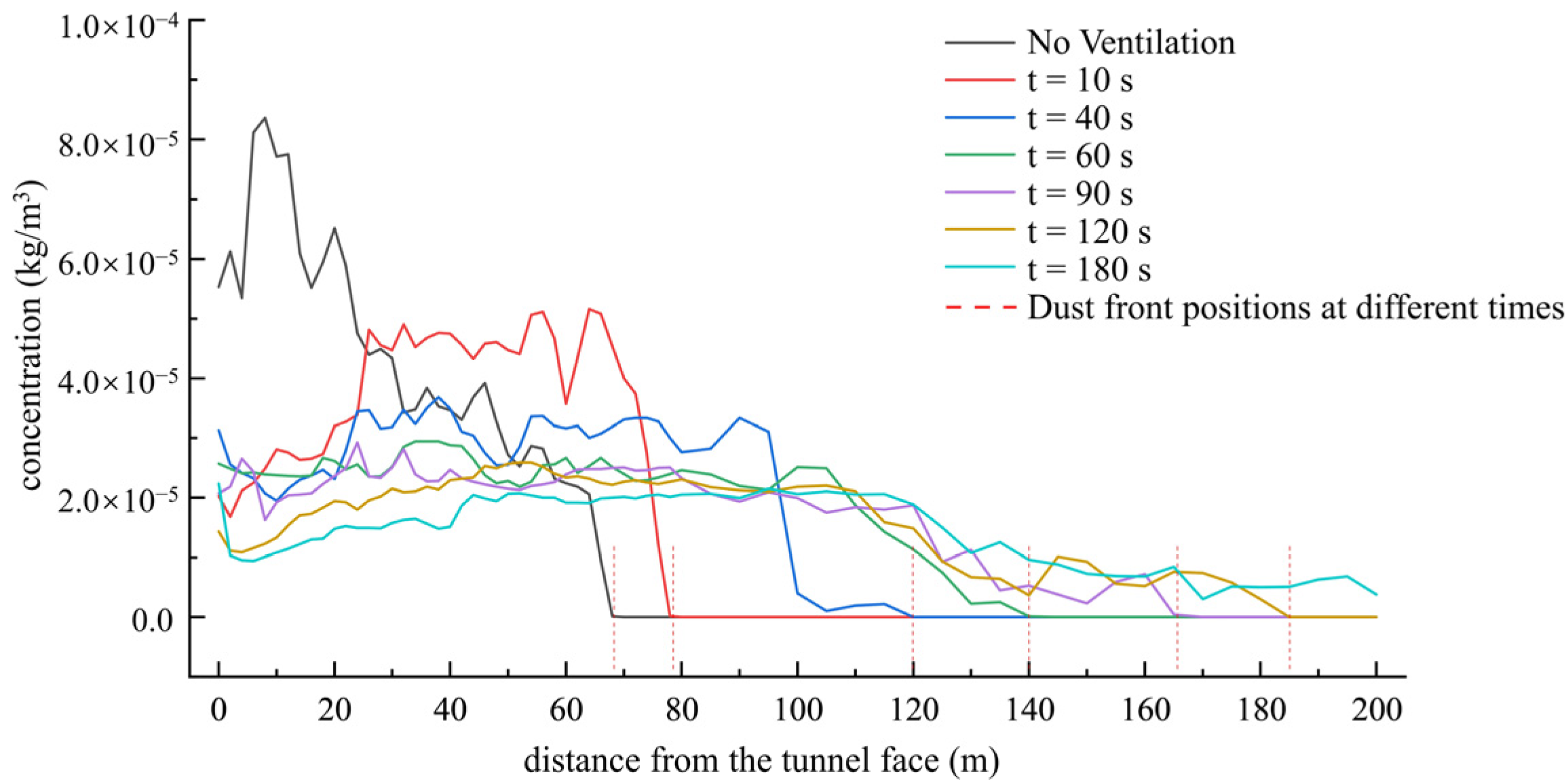

3.2.1. Dispersion Under Stagnant Air

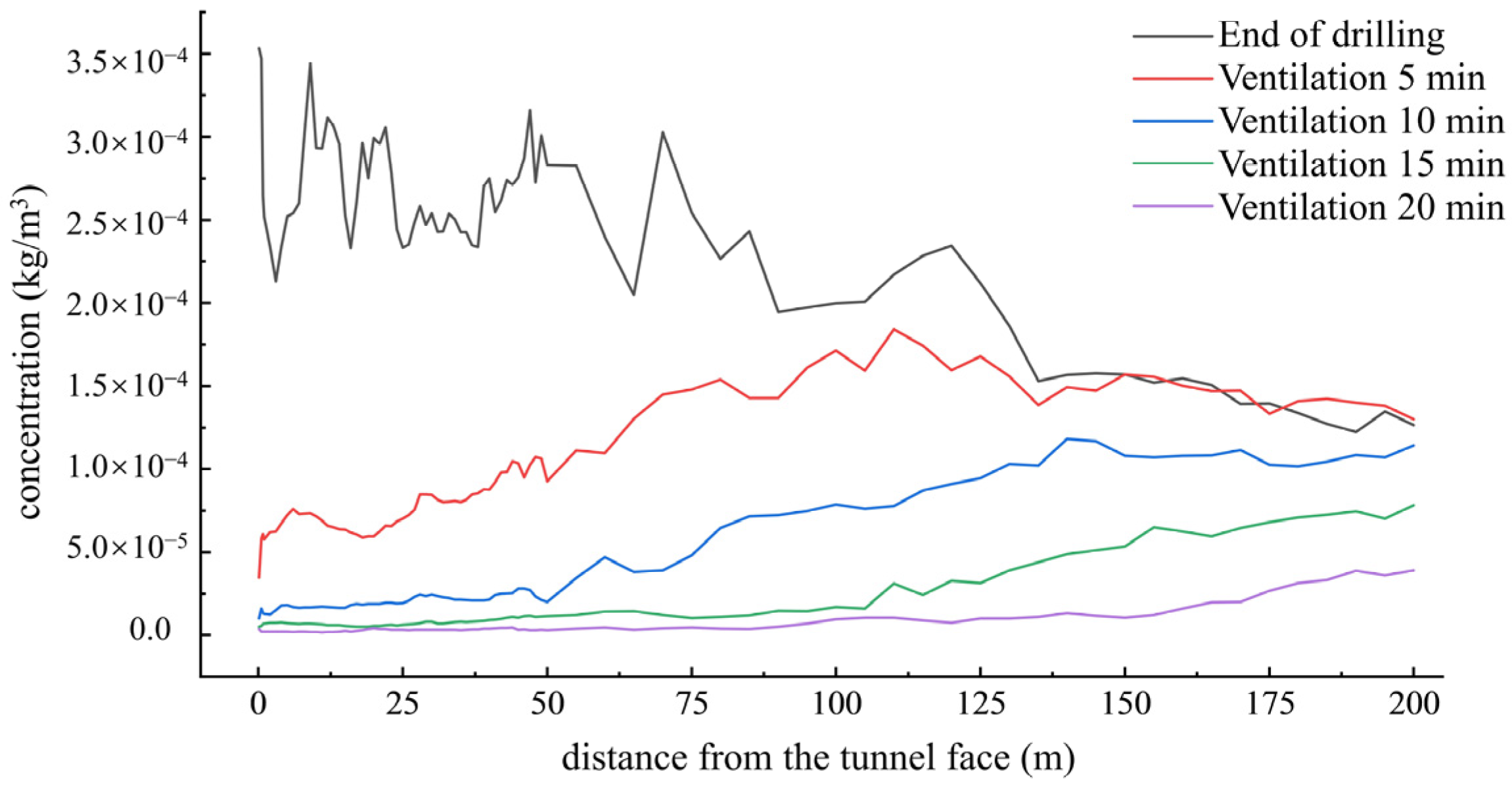

3.2.2. Dispersion and Concentration Under Ventilation

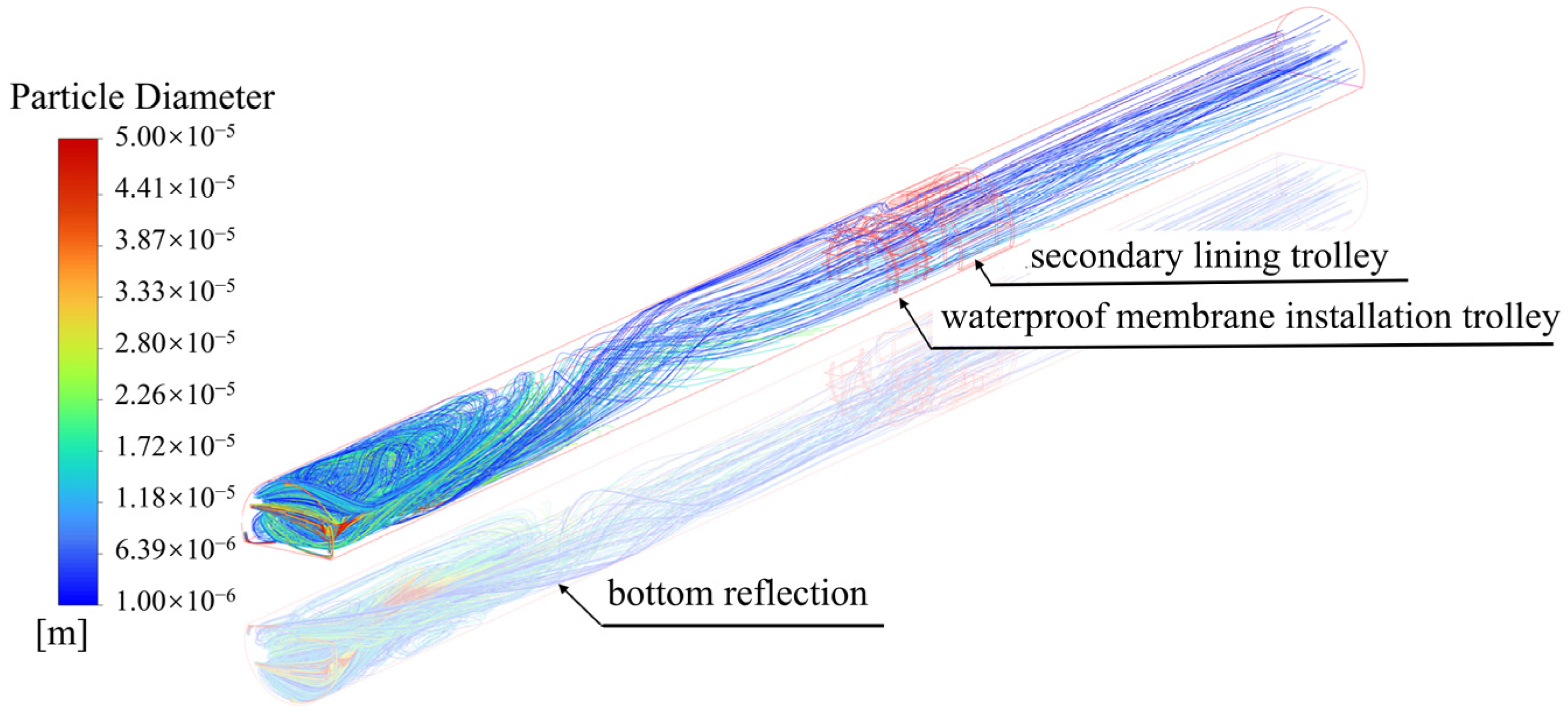

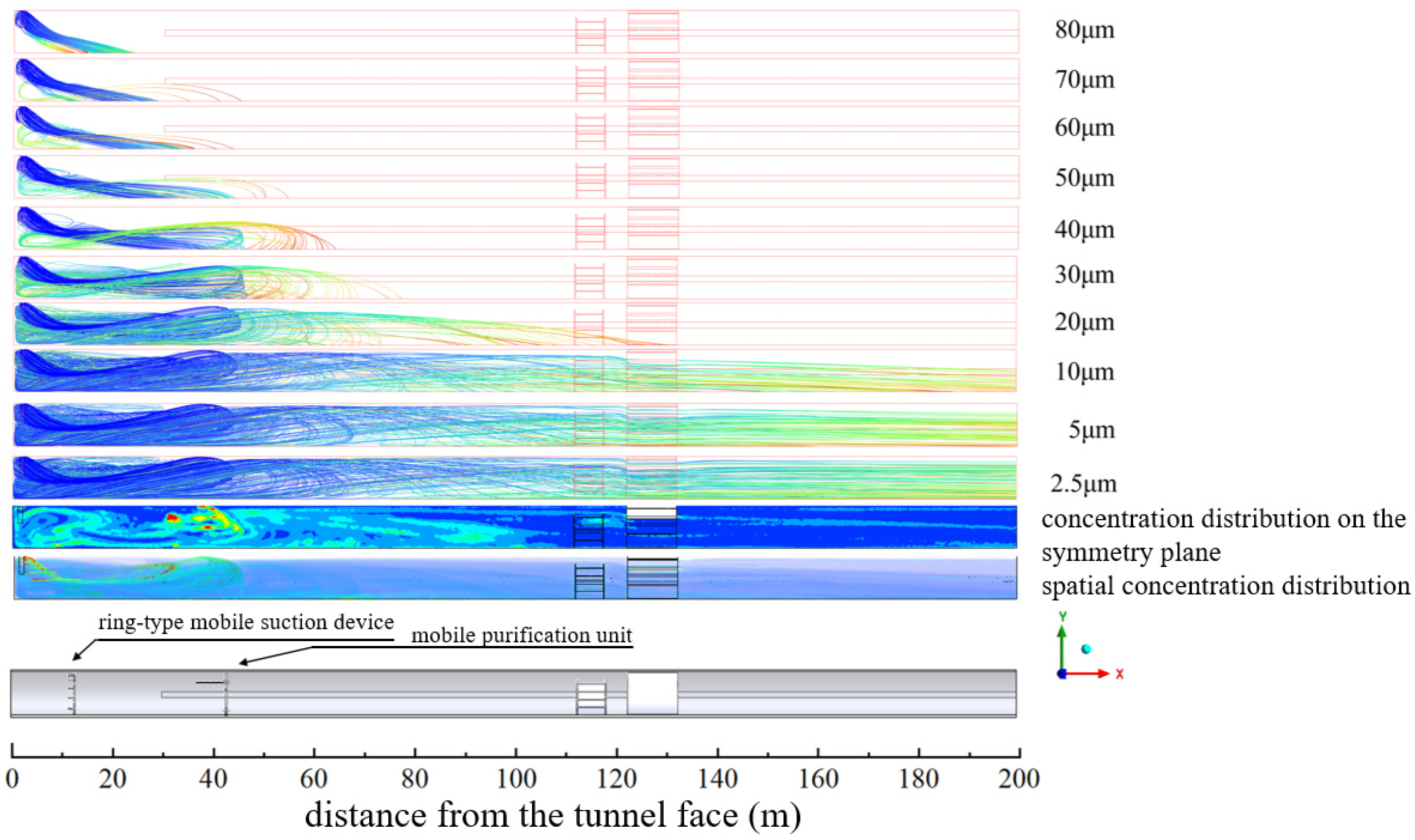

3.3. Dust Dispersion During the Shotcreting Process

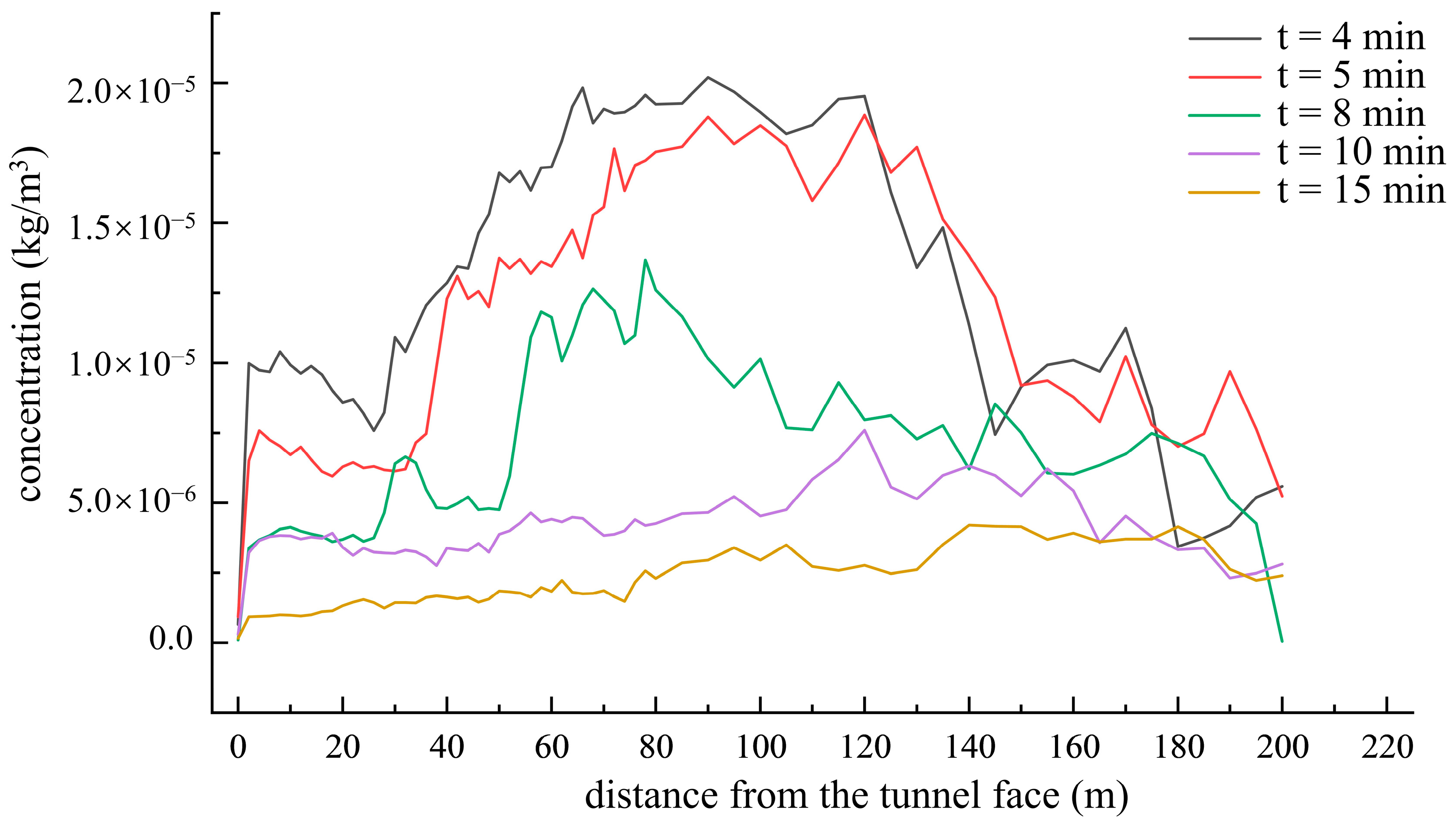

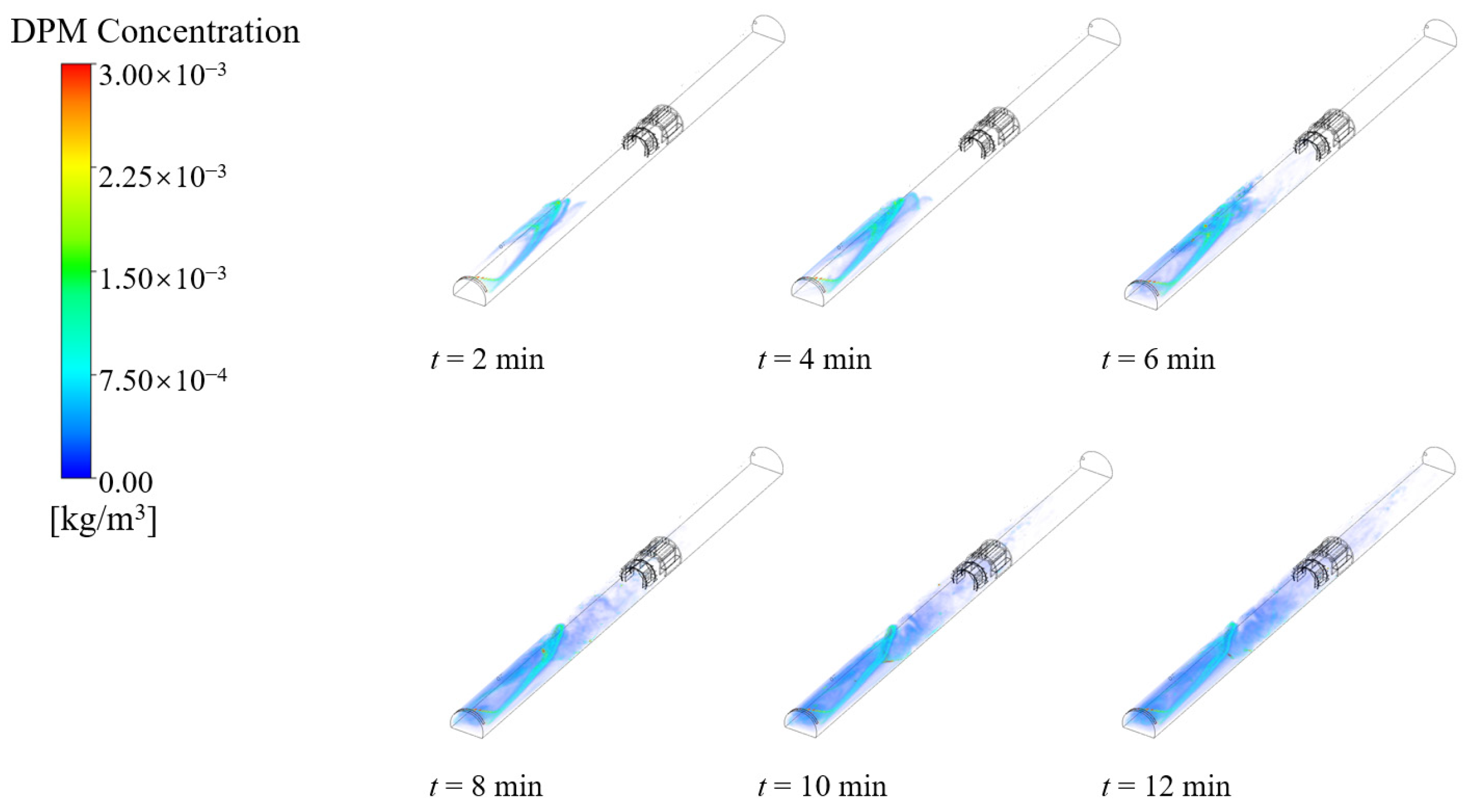

3.3.1. Dust Dispersion and Concentration Evolution Under Top Shotcreting

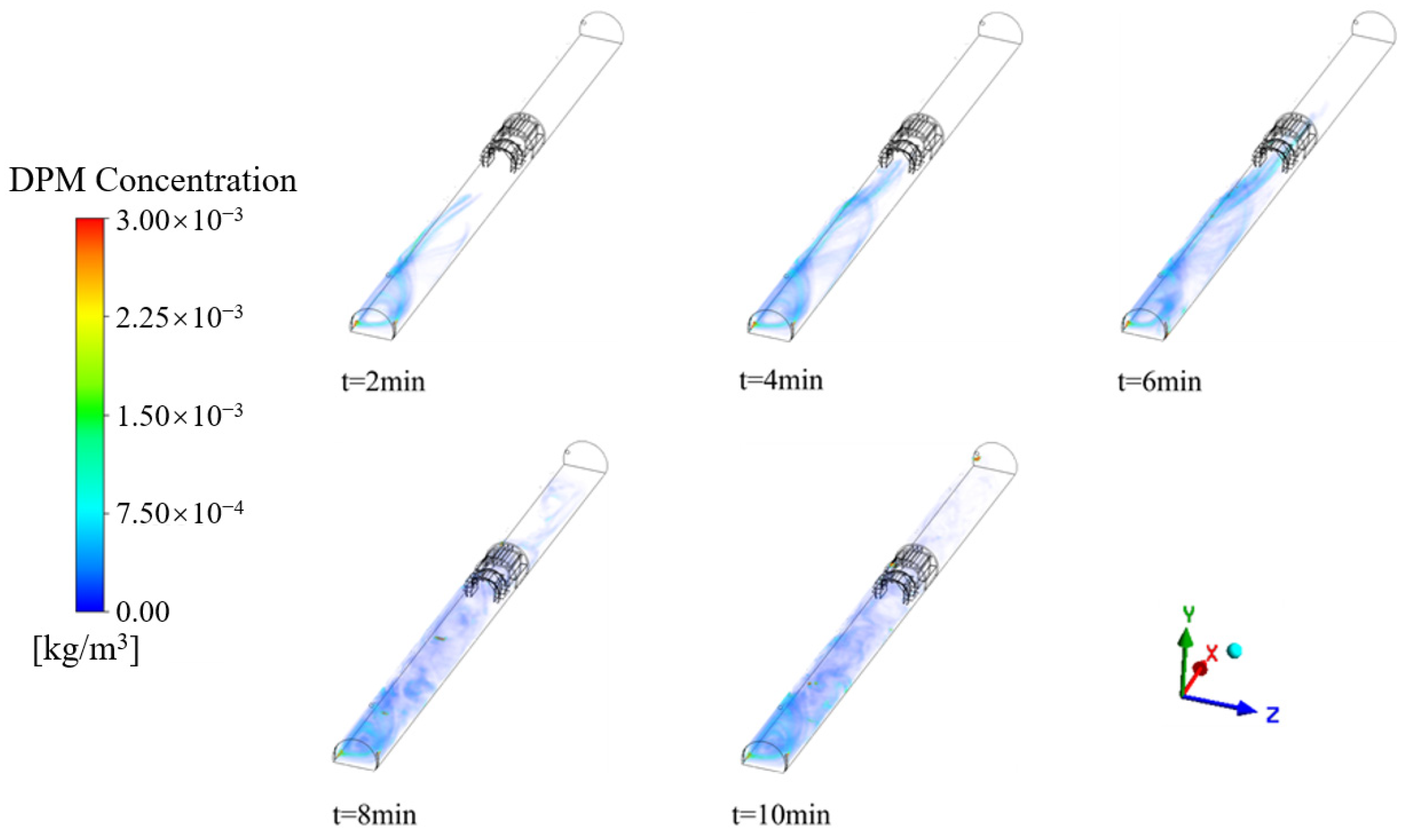

3.3.2. Dust Dispersion and Concentration Evolution Under Side Shotcreting

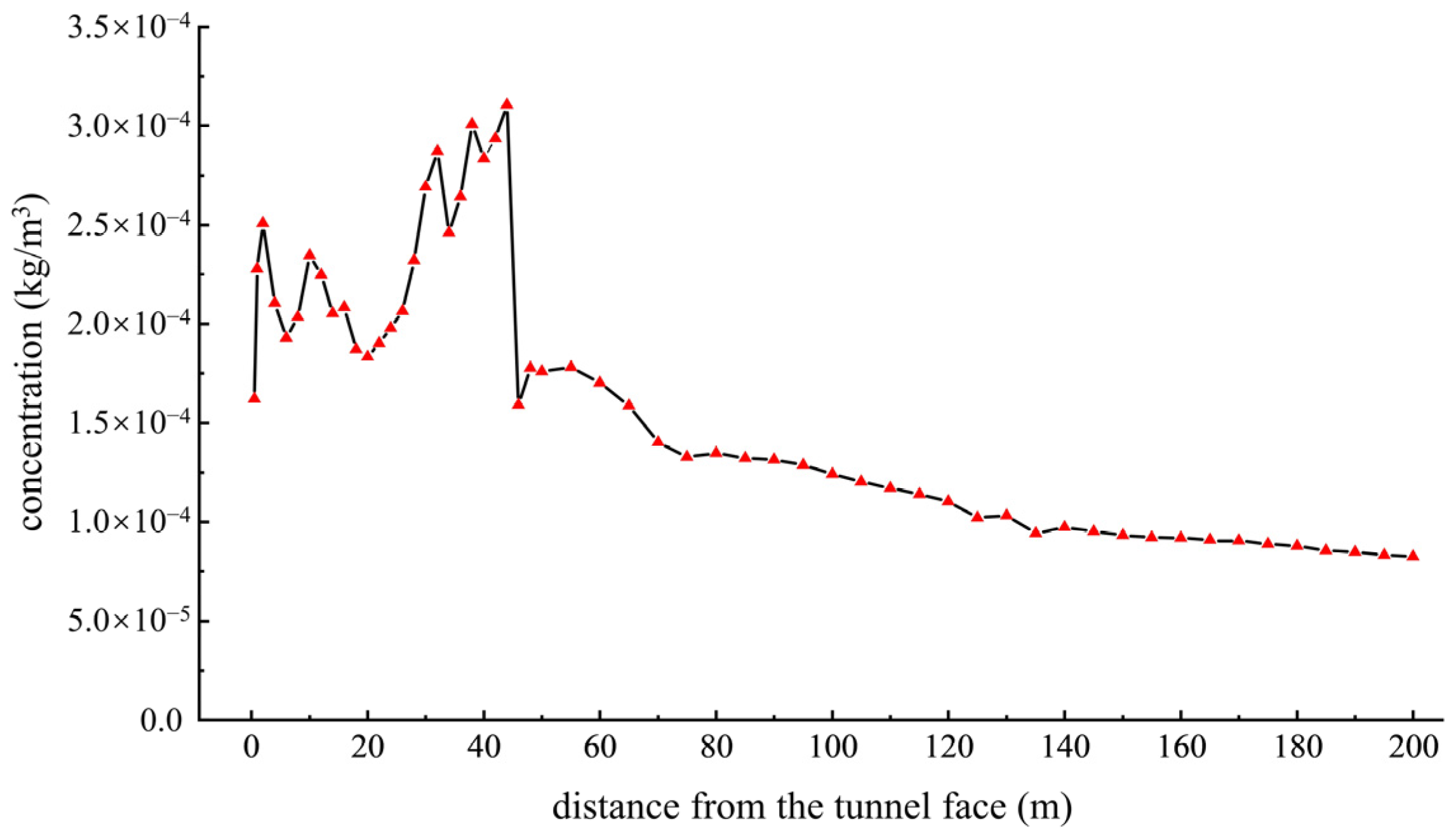

3.4. Benchmarking with Published Measurements

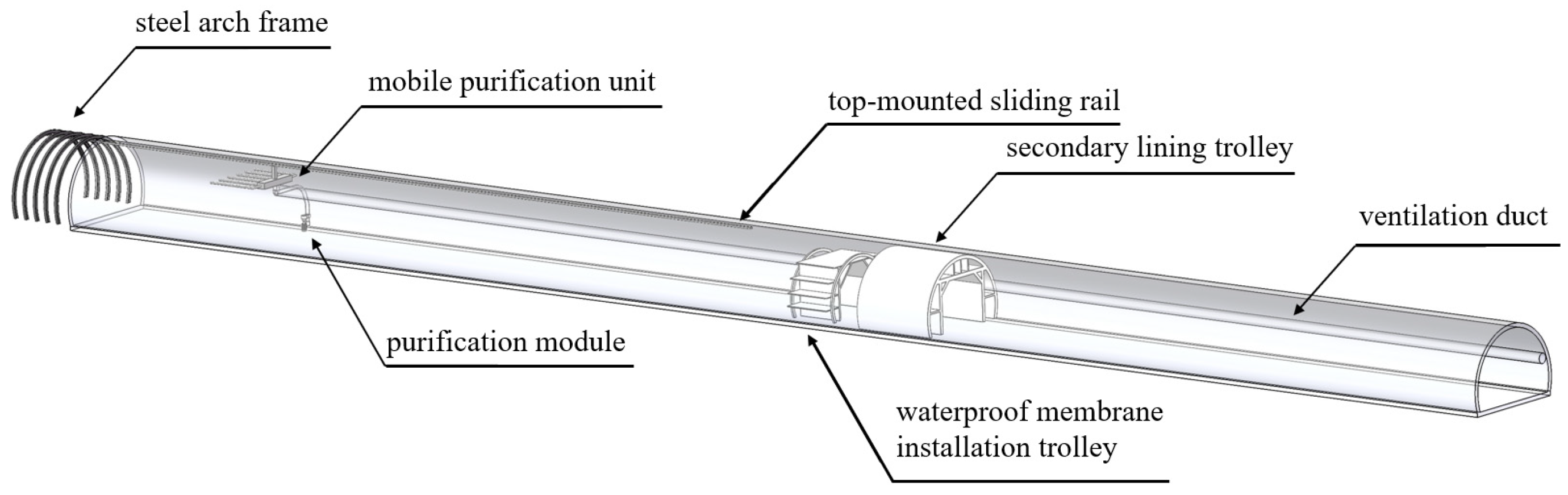

4. Design of the Rail-Mounted Purification System

4.1. Current Situation Assessment and Design Objectives

4.2. Development of the Rail-Mounted Dust Purification Equipment

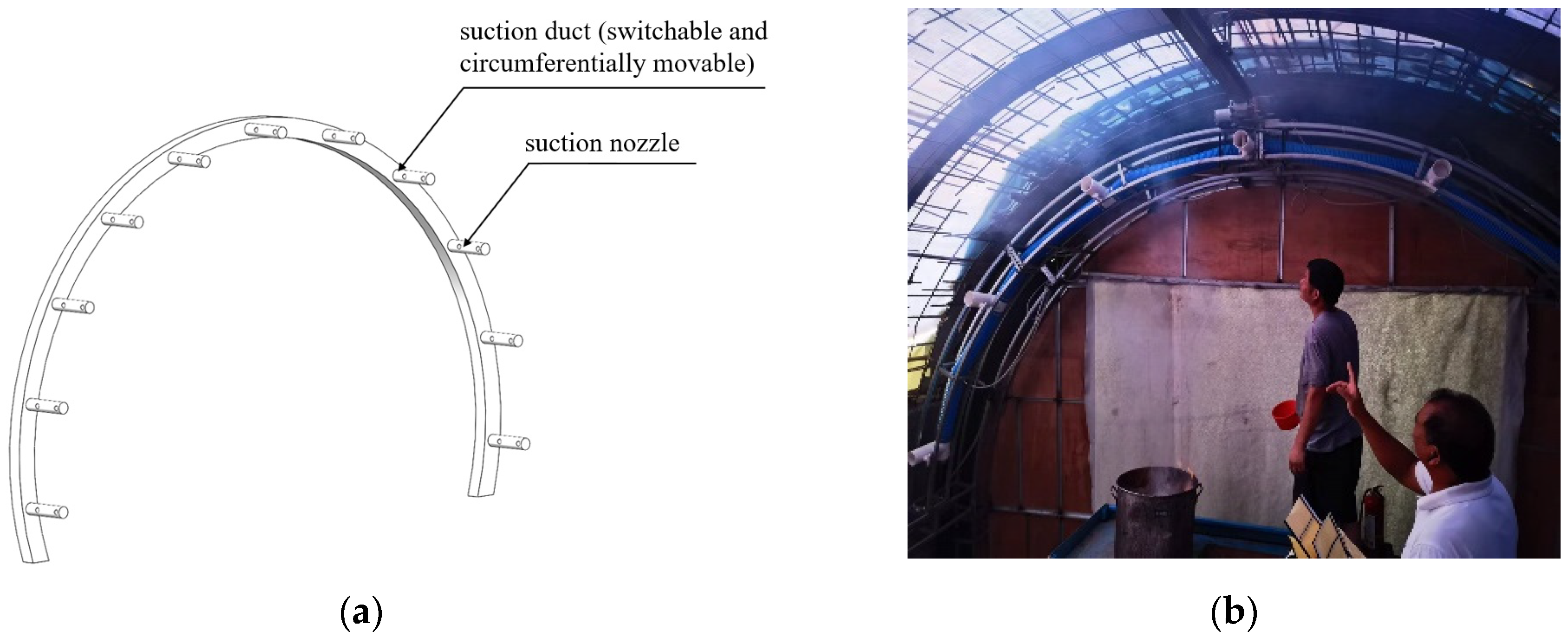

4.2.1. Ring-Type Mobile Suction Device

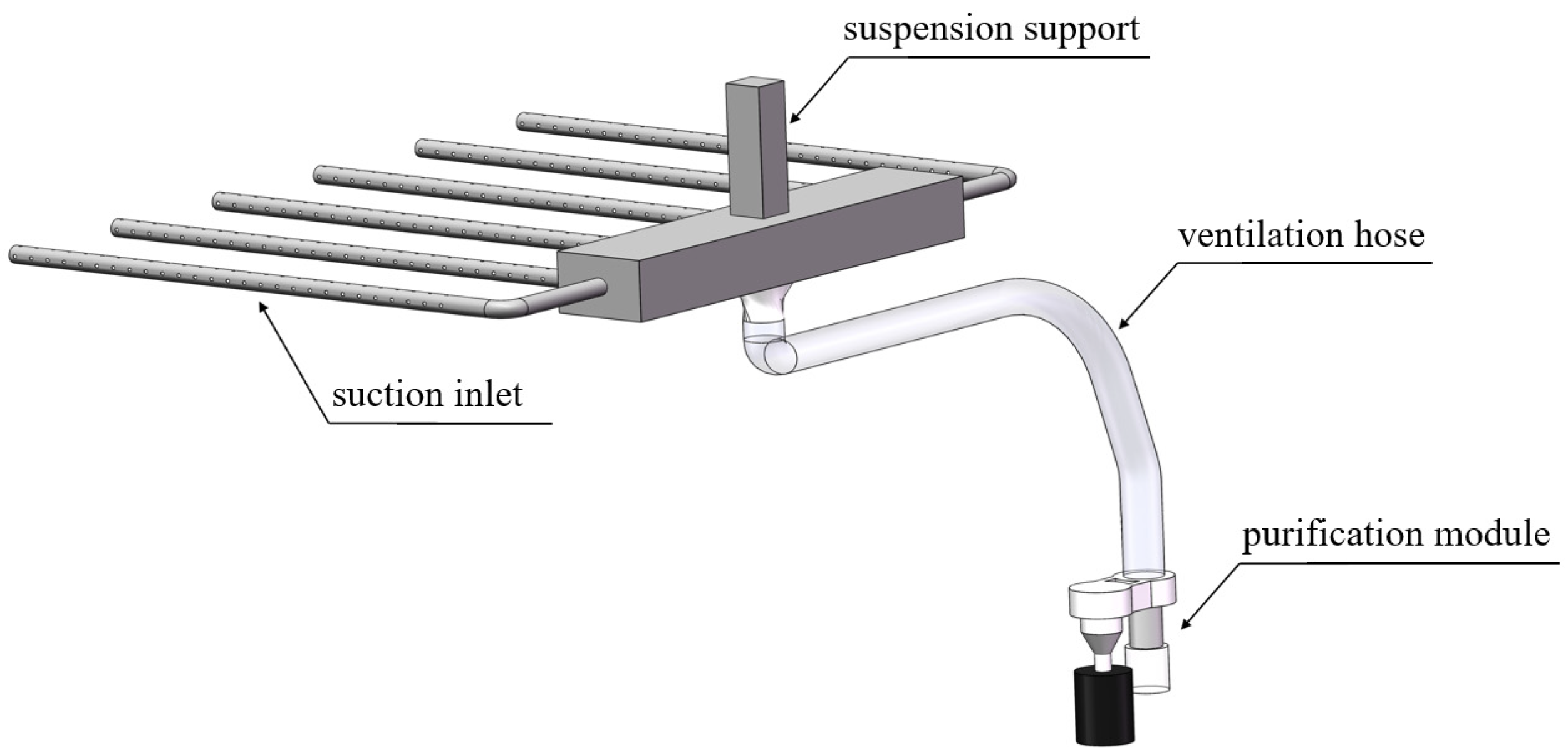

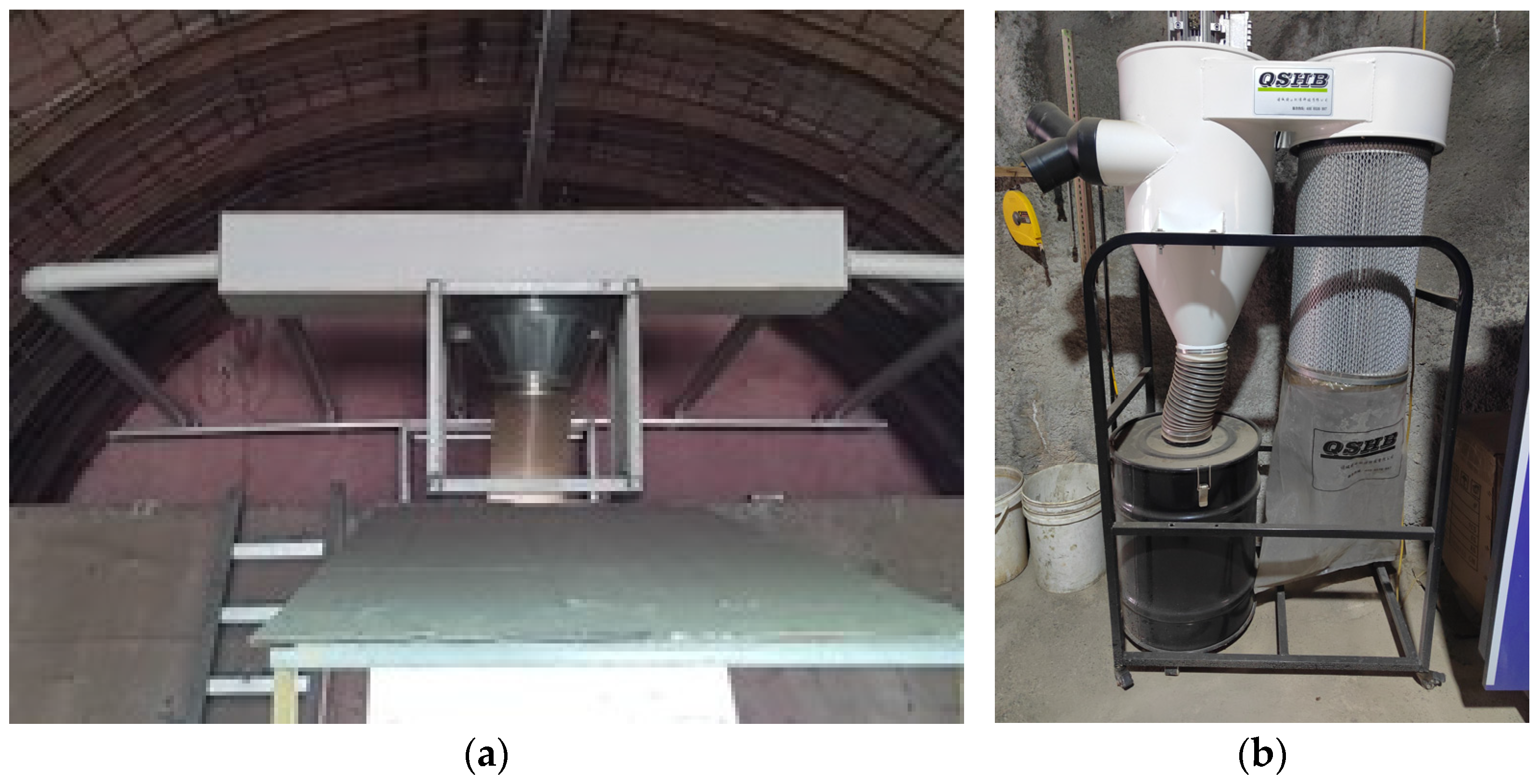

4.2.2. Mobile Purification Unit

4.3. Rail-Mounted Air Purification Schemes

4.3.1. Drilling Operation

4.3.2. Blasting Operation

4.3.3. Shotcreting Operation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, H.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Lan, Y.; Ge, Z. Experimental study on the influence of longitudinal slope on airflow–dust migration behavior after tunnel blasting. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, H.; Wang, W.; Zhou, H.; Lu, F.; Wan, L.; Luo, X.; Teng, L. CO diffusion study and spatial and temporal variation modeling during the construction period of a plateau railroad tunnel. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 42565–42575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, X.; Ren, J.; Yang, R.; Tong, Y. Study on tunnel ventilation and pollutant diffusion mechanism during construction period. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0322984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, B.; Shao, L.; Li, Y.; Ran, H.; Wei, L. Investigation into dust migration patterns in small-section tunnels and large steep-sloped inclined shafts. Fluid Dyn. Mater. Process. 2025, 21, 555–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhang, W.; Guo, S.; An, H. Numerical modelling of blasting dust concentration and particle size distribution during tunnel construction by drilling and blasting. Metals 2022, 12, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Sun, N.; Liu, Q.; Guo, L.; Xue, Q.; Liu, C.; Niu, W. Comparative study of dust pollution and air quality of tunnelling anchor integrated machine working face with different ventilation. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 122, 104377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yang, X.-E.; Wang, Z.-P.; Li, Q.-W.; Deng, J. Diffusion characteristics of coal dust associated with different ventilation methods in an underground excavation tunnel. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 184, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lai, H.; Peng, Z.; Zhong, H.; Liao, Y.; Liao, J. Dust distribution pattern and optimization of tunnel ventilation system. Staveb. Obz.-Civ. Eng. J. 2024, 33, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Ruan, C.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Lin, J. Effect of ventilation parameters on dust pollution characteristics of drilling operation in a metro tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 132, 104867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Hao, C.; Cai, F.; Teng, L.; Luo, X. Impact analysis of dust evolution pattern and determination of key ventilation parameters in highland highway construction tunnels. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, W. Optimisation of synergistic ventilation between dust and gas in a gas tunnel. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Xu, X.; Jiang, W. Influences of ventilation parameters on flow field and dust migration in an underground coal mine heading. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Wu, S.; Li, Y.; He, L.; Wang, P. Predictive analysis of ventilation dust removal time in tunnel blasting operations based on numerical simulation and orthogonal design method. Processes 2025, 13, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, C.T. On models for turbulence modulation in fluid–particle flows. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2000, 26, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerfeld, M. Validation of a stochastic Lagrangian modelling approach for inter-particle collisions in homogeneous isotropic turbulence. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2001, 27, 1829–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, J. Large eddy simulation of particle deposition and resuspension in turbulent duct flows. Adv. Powder Technol. 2019, 30, 656–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiao, J. Bibliometric analysis and review of mine ventilation literature published between 2010 and 2023. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xue, Y.; Xiao, J.; Shi, D. Diffusion characteristics of airflow and CO in the dead-end tunnel with different ventilation parameters after tunneling blasting. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 36269–36283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, S.; Dong, C.; Wang, S.; Guo, Y.; Gao, X.; Sun, B.; Chen, W.; Guo, C. Three-Stage Numerical Simulation of Tunnel Blasting Dust Diffusion Based on Field Monitoring and CFD. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 150, 105830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, L.; Liu, G.; Xiao, W. Research on Dust Suppression Technology of Shotcrete Based on New Spray Equipment and Process Optimization. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 4831215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jin, M.; Li, X.; Tian, J.; Yang, B.; Liu, J.; Zhou, S.; Wang, F. Experimental study on concentration and size distribution characteristics of particulate matter in cold and hot rolling. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Shang, K.; Cui, Z.; Xue, G. Study on mass-based particle-size distribution characteristics of 36 types of dust in railway workplaces. Railw. Occup. Saf. Health Environ. Prot. 1994, 21, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bentz, D.P.; Garboczi, E.J.; Haecker, C.J.; Jensen, O.M. Effects of cement particle size distribution on performance properties of Portland cement-based materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 1999, 29, 1663–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wei, D.; Lv, X.; Wu, Z.; Shen, Z.; Yu, C.; Mu, Y.; Li, T. Research on the transport mechanism of tunnel dust based on FLUENT. Eng. Lett. 2025, 33, 520–529. [Google Scholar]

- Semin, M.; Faynburg, G.; Tatsiy, A.; Levin, L.; Nakariakov, E. Insights into turbulent airflow structures in blind headings under different ventilation duct distances. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSYS Inc. ANSYS Fluent Theory Guide, Release 2022 R1; ANSYS Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, C.M. Practical Prediction of Blast Fume Clearance and Workplace Re-Entry Times in Development Headings. In Proceedings of the 10th International Mine Ventilation Congress (IMVC 2014), Sun City, South Africa, 17–22 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tiile, R.N. Investigating Blast Fume Propagation, Concentration and Clearance in Underground Mines Using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). Doctoral Dissertation, Missouri University of Science and Technology, Rolla, MO, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- TZ 204-2008; Technical Guide for Railway Engineering Construction. China Railway Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2008.

| Process | Dust Particle | Particle Size Range (μm) | Median Particle Size (μm) | Initial Velocity (m/s) | Mass Flow Rate (kg/s) | Distribution Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drilling | Granite | 1–50 | 18.3 | 0.2 | 0.005 | 1.41 |

| Blasting | Granite | 1–50 | 18.3 | 7 | 0.837 | 1.41 |

| Shotcreting | Cement | 1–80 | 16.8 | 0.5 | 0.005 | 1.31 |

| Boundary Name | Model Location | Boundary Type | Parameters | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inlet | Ventilation duct outlet | Velocity-inlet | Velocity: Turbulence intensity: Hydraulic diameter: | 15 m/s 2.77% 1.2 m |

| Outlet | Tunnel exit | Pressure-outlet | DPM Condition: | escape |

| Work | Tunnel face | Wall | DPM Condition: | reflect |

| Floor | Tunnel invert | Wall | DPM Condition: | trap |

| Wall | Other tunnel boundaries | Wall | DPM Condition: | reflect |

| Discrete Phase Model | Define |

|---|---|

| Interaction with the continuous phase | On |

| Number of continuous phase iterations per DPM iteration | 20 |

| Max. number of steps | 50,000 |

| Unsteady particle tracking | On |

| Physical models | Saffman lift force; pressure gradient force |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Wan, C.; Wu, Z.; Hu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Song, R.; Wang, L. Dust Dispersion Mechanisms and Rail-Mounted Local Purification in Drill-and-Blast Tunnel Construction. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010519

Wu H, Wang J, Wan C, Wu Z, Hu Z, Wu Y, Song R, Wang L. Dust Dispersion Mechanisms and Rail-Mounted Local Purification in Drill-and-Blast Tunnel Construction. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):519. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010519

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Haiping, Jiqing Wang, Changming Wan, Zhijian Wu, Ziquan Hu, Yimin Wu, Renjie Song, and Lin Wang. 2026. "Dust Dispersion Mechanisms and Rail-Mounted Local Purification in Drill-and-Blast Tunnel Construction" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010519

APA StyleWu, H., Wang, J., Wan, C., Wu, Z., Hu, Z., Wu, Y., Song, R., & Wang, L. (2026). Dust Dispersion Mechanisms and Rail-Mounted Local Purification in Drill-and-Blast Tunnel Construction. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010519