1. Introduction

With the continuous increase in the scale and complexity of software systems, the number of latent security vulnerabilities within them has shown an exponential growth trend. Traditional security protection models predominantly rely on external interception and alerts during the operational phase using network security devices such as firewalls and intrusion detection systems. Although these devices can effectively identify and block known attack patterns, and even correlate CWE (Common Weakness Enumeration) information to provide security analysts with vulnerability root cause classification, they are inherently still remedial measures representing a “right-shift” approach—taking action only after vulnerabilities have been exploited—and cannot fundamentally reduce the inherent security risks of the software itself.

Against this backdrop, the concept of “shift-left security” has emerged and gradually become a core practice direction in the field of software security engineering. This philosophy emphasizes embedding security activities as early as possible into the left-side stages of the software development lifecycle, including requirements analysis, architecture design, and coding implementation. Its core objective is to identify and remediate security defects at the source, eliminating vulnerabilities before deployment, thereby significantly reducing later-stage remediation costs and the probability of security incidents.

To achieve effective shift-left security, Static Application Security Testing technology is a key enabler. This method can discover potential coding errors by parsing program code without executing the program under test. Among these technologies, CodeQL [

1,

2,

3], as an industry-leading semantic code analysis engine, represents the technological forefront in this domain. It allows security personnel to abstract security defects into queryable data logic, enabling systematic, in-depth scanning of code repositories to accurately locate various security issues, ranging from simple input validation oversights to complex logical chain defects [

4,

5,

6]. Particularly important is the inherent tight correlation between CodeQL’s detection rules and the CWE framework, with its query library directly mapping to specific CWE weakness entries. This means that developers not only receive prompts during the coding phase indicating that “a certain line of code contains a vulnerability” but can also gain deeper insight into the CWE root cause corresponding to that vulnerability, thereby fostering a thorough understanding of similar defect patterns and enabling fundamental fixes.

To enhance the accuracy and scalability of static code analysis, researchers have developed numerous analysis tools. Among them, CodeQL is a program analysis engine based on a logical programming language. It works by abstracting source code into a queryable relational database that stores program representations such as the abstract syntax tree (AST) [

7], control flow graph (CFG) [

8], and call graph [

9]. By writing QL code, users can perform semantic analysis and vulnerability detection. This approach of treating code as queryable data provides developers with a novel methodology for discovering and understanding potential issues. Other notable static analysis frameworks include Tai-e [

10], Soot [

11], and WALA [

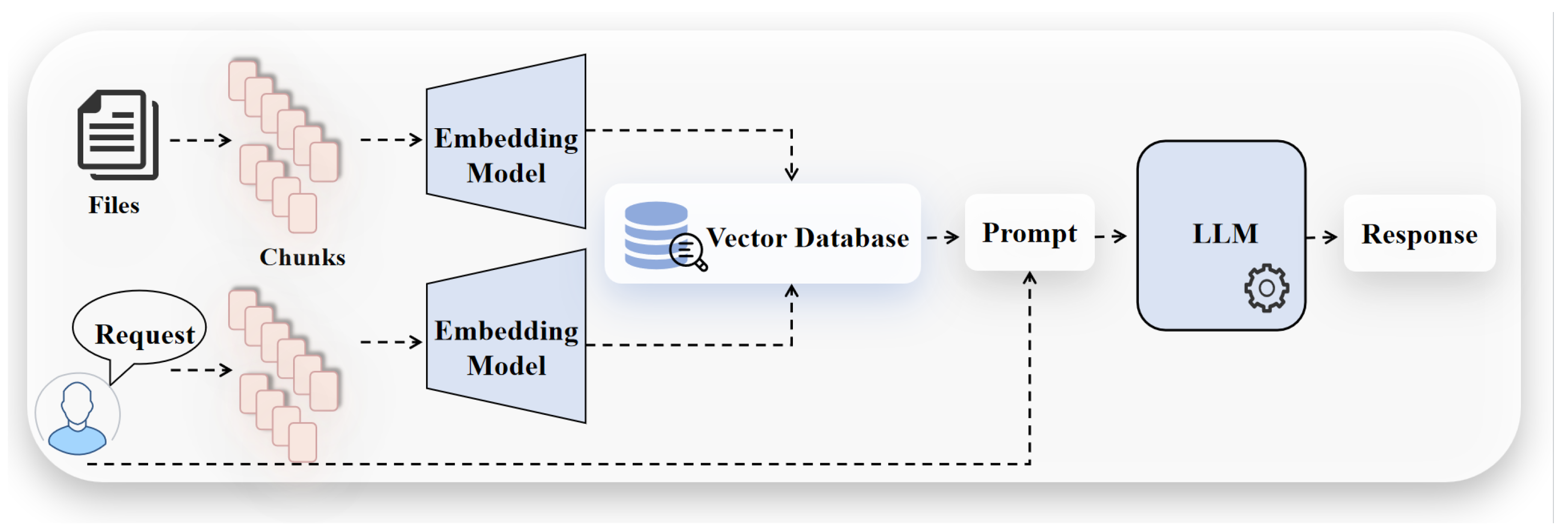

12]. CodeQL’s support for multiple programming languages, such as Java, C/C++, Python, JavaScript, and Go, makes it particularly suitable for multi-language projects.The overall workflow of CodeQL is based on database construction and querying, as shown in

Figure 1. First, the CodeQL extractor extracts and analyzes the program’s source code, converting it into a database. This database format is easier to query than raw code and stores various details of the code, such as class names, function call relationships, variables, and more. Next, users can write and execute QL code, which search the database for specified patterns. After the queries are executed, CodeQL returns all instances that match the query patterns and provides suggestions for fixing the problem.

Due to the variability in vulnerability-triggering paths, manually writing QL code remains the primary approach for performing static code analysis with CodeQL. Testers must rely on their professional expertise to identify and exploit vulnerabilities, write corresponding QL code, and then execute them against the CodeQL database via the evaluator to uncover potential security issues in the system. However, this approach has significant limitations. On one hand, it demands a high level of expertise from testers, requiring not only solid security knowledge but also proficiency in CodeQL syntax and query logic. On the other hand, it is labor-intensive in practice, with low detection efficiency, and the queries written often fall short in terms of vulnerability coverage and detection effectiveness. With the development of large language model (LLM), automatically generating queries has emerged as a new direction. LLMs demonstrate strong code generation and generalization capabilities, which can partially alleviate the inefficiency of manual query writing. Nevertheless, this approach also has clear drawbacks. On one hand, inherent hallucination issues in LLMs can lead to syntax errors, calls to invalid modules, or query logic that does not align with the semantics of the vulnerabilities. On the other hand, LLMs lack deep understanding of the specific context of vulnerabilities, so the accuracy of their generated queries is often unsatisfactory.Therefore, whether through manual writing or LLM-based generation, the creation of QL code still suffers from non-negligible deficiencies.

To address the above challenges, this paper proposes CQLLM (CodeQL-enhanced Large Language Model), a framework for automatically generating executable QL code based on LLM. Given a specified CWE identifier and a vulnerability description as input, CQLLM outputs the corresponding executable QL code. The main contributions are as follows:

Proposed CQLLM, a framework for automatic generation of executable QL code based on LLM. It enables the automatic generation of QL code from CWE identifiers and vulnerability descriptions. The execution success rate increased from 0.31% to 72.48%, and CWE detection coverage reached 57.4%. This reduces reliance on manual effort while improving the correctness of generated QL code and the accuracy of vulnerability detection.

Construction of a high-quality QL knowledge base and a dataset. The knowledge base includes common vulnerability detection examples and QL dependency libraries. By using Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) to constrain the LLM’s generation process, it effectively avoids syntax errors and invalid module calls. The dataset was enhanced based on officially provided QL code. QL code generated using this knowledge base and dataset achieved an execution rate of 65.1%, significantly outperforming directly generated results from the LLM.

Domain-specific fine-tuning of the base model using LoRA. This enhances the model’s understanding of vulnerability semantics and QL syntax, improving its code generation performance in complex scenarios. After fine-tuning, the LLM achieved an executable QL code generation rate of 22.11%.

The overall structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 introduces the current research status of QL code generation.

Section 3 describes the design methodology of CQLLM, including its overall architecture and key processes.For reproducibility and further research, the implementation source code of CQLLM is publicly available online (CQLLM:

https://github.com/Arashiailing/CQLLM), accessed on 18 October 2025.

Section 4 provides a detailed account of the implementation of CQLLM.

Section 5 presents the experimental results, detailing parameter settings and evaluation metrics, and includes comparative and ablation study results.

Section 6 concludes the paper and offers perspectives for future work.

3. Our Proposed Methodology

This paper proposes a QL code generation framework, CQLLM, which integrates RAG and LoRA. As shown in

Figure 3, the overall architecture consists of the following four core modules.

Data Collection and Preprocessing Module: The data sources include official CodeQL class and function documentation, common CWE vulnerability detection examples, and executable QL code collected from technical forums and blogs. Executable CWE samples are further annotated and augmented to construct the fine-tuning dataset and the RAG knowledge base. This process alleviates the scarcity of high-quality CodeQL data and provides a reliable foundation for both model fine-tuning and knowledge retrieval.

RAG Knowledge Base Module: This module retrieves relevant dependency documentation and example code snippets from the RAG knowledge base. The retrieved results are then reranked using a re-ranking model to obtain the top-k most relevant knowledge entries. These are combined with the user’s natural language query and fed into the model, enhancing its understanding of CodeQL syntax and library functions. This approach effectively reduces syntax and function-calling errors during generation, improving the accuracy and executability of the generated QL code.

LoRA Fine-Tuning Module: Using the augmented CodeQL dataset, this module fine-tunes the pretrained LLM via LoRA to improve its adaptability to CodeQL-specific tasks. This process compensates for the limitations of general-purpose models in QL code generation, enabling the model to better understand vulnerability semantics and generate executable QL code from natural language requirements.

Inference and Generation Module: When the user inputs a natural language query, the system first retrieves relevant background knowledge via RAG. The retrieved information is then concatenated with the user input and fed into the fine-tuned model to generate high-quality QL code. This module achieves the automatic transformation from natural language to executable QL queries, significantly improving the efficiency and accuracy of vulnerability detection rule development.

4. Method Implementation

This section presents the implementation details of the CQLLM, including data preparation, knowledge base construction, fine-tuning, and inference. Each component plays a critical role in enabling accurate and efficient CodeQL query generation. The following subsections elaborate on these modules in detail.

4.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing Module

The data used in CQLLM can be divided into two main categories: the RAG knowledge base and the fine-tuning dataset.The RAG knowledge base enables the model to generate responses that better conform to CodeQL syntax. The fine-tuning dataset, which consists of both training and evaluation subsets, provides the data foundation for LoRA fine-tuning, ensuring that the model can effectively learn and assess CodeQL-specific generation patterns.

Vulnerability Database: To achieve the automatic generation of QL code for detecting security vulnerabilities in Python applications using CodeQL, it is first necessary to construct a deliberately vulnerable application composed of a series of CWE vulnerabilities. The source code of this vulnerable application is then extracted to build a CodeQL database. By executing the QL code automatically generated by the large model within this database, successful execution is considered an indicator that the model has produced a correct output. The primary source of vulnerability samples is the CVEfixes dataset. CVEfixes is a comprehensive, source-level vulnerability dataset that automatically collects and organizes repository commit information related to vulnerabilities and their fixes from CVE records in the National Vulnerability Database (NVD). From this dataset, we selected a collection of Python code samples containing vulnerabilities, covering 54 categories of CWE vulnerabilities.

RAG Knowledge Base: We used web crawlers to obtain API metadata from the official CodeQL documentation, including information such as API paths, modules, predicates, functions, and aliases. These data were then cleaned, indexed, and organized into structured tables. In addition, we collected, organized, compiled, and summarized successfully compiled official code samples to build a code dataset. After gathering the CodeQL corpus from the internet, this study focused on CodeQL queries for detecting Python security vulnerabilities. Considering Python’s wide usage, most of the collected CodeQL corpus is written in Python. Finally, the code dataset was refined and formatted, and subsequently established as the knowledge base.

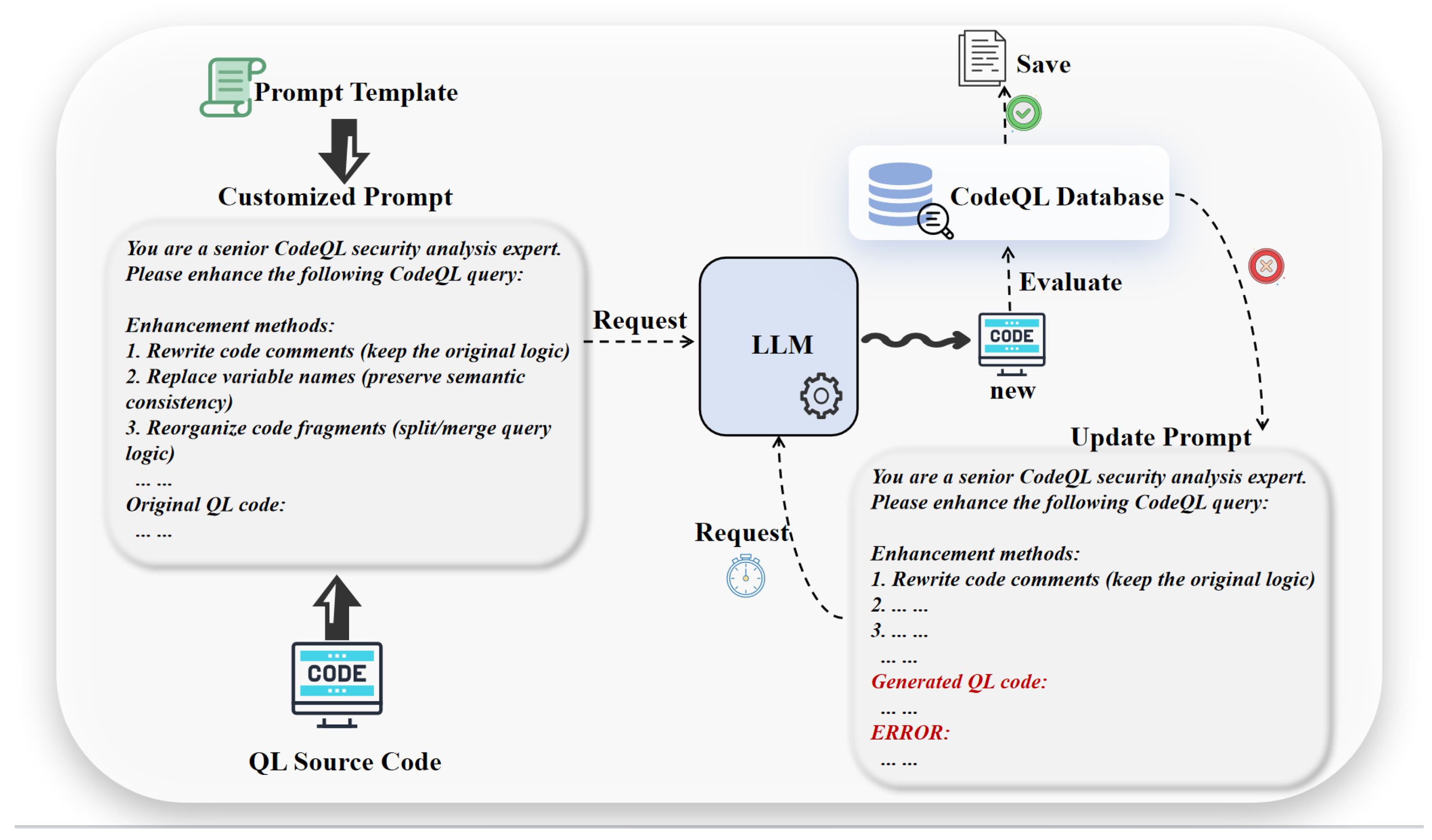

Fine-tuning Dataset: We selected the QL code officially provided by CodeQL as the training dataset. According to statistics, there are only 49 QL codes used for security detection and 351 for non-security detection, which does not meet the quantity requirements for large model fine-tuning. Therefore, we adopted data augmentation methods to expand the dataset. We used the iFlytek Spark large model to annotate the QL code dataset used for security detection, aiming to provide the LLM with accurate sample examples and knowledge to facilitate mapping natural language queries to corresponding code. To meet the dataset size required for LoRA fine-tuning, we performed data augmentation on the annotated dataset using the GLM4.5 model. The augmentation methods included comment rewriting, variable renaming, and code fragment reorganization. To improve generation efficiency, we designed an iterative prompt, as shown in

Figure 4. In the first round, the LLM generates a customized prompt for each CodeQL script. Then, using the customized prompt, it produces enhanced QL code, which is executed in the database. The QL codes that execute successfully are saved. For those that fail, we insert their content and corresponding error messages into the prompt and attempt regeneration. If the QL code still fails after three iterations, it is discarded, and the process continues with the remaining files.Finally, the hash of each QL code file is computed and compared with a hash table to filter out duplicate samples, producing a new dataset. The hash table records the hash value of every saved QL code file. When processing a new QL file, its hash value is first calculated and compared with the existing ones in the table. If the hash already exists, the file is identified as a duplicate and removed; otherwise, the new hash is added to the table for subsequent deduplication.After data augmentation, a total of 902 QL codes for security detection were obtained. Finally, the unannotated QL codes, non-security detection QL codes, and augmented QL codes were consolidated into a single QL code dataset. Based on this dataset, we constructed Alpaca-style instruction–response datasets and completion datasets, generating a total of 3754 training samples. The dataset was divided as follows: 3004 samples for the training set, 375 samples for the validation set, and 375 samples for the test set.

4.2. RAG Knowledge Base

After data collection and preprocessing, we obtained the CodeQL function dependency set and API metadata files. Correctly importing dependencies is a critical factor for the successful execution of QL code, and the function dependency set plays a key role in ensuring that the model accurately identifies and imports the required dependencies. To this end, we optimized the slicing method: to reduce the inclusion of irrelevant dependencies, the text block size was set to 128, and multi-symbol delimiters were used as text segment identifiers, enabling more precise segmentation of each dependency and improving retrieval accuracy.For the API metadata files, considering their large content volume but relatively low information density, using a text block size of 128 would slow down retrieval. Therefore, the block size was set to 512, with “\n” characters as segment delimiters.Additionally, CodeQL-provided security vulnerability detection examples were incorporated into the knowledge base to guide the model in generating semantically and functionally similar executable code snippets.Regarding the knowledge base configuration, we employed the 8B Qwen3 embedding model and a reranking model. The embedding model converts prompts and knowledge base files into high-dimensional vector representations, ensuring that semantic information is effectively captured. The reranking model rearranges the retrieved results according to relevance, providing more accurate contextual information. All of the above work was conducted on the RAGFlow platform, an open-source RAG engine built on “deep document understanding,” which offers a streamlined and generalizable RAG workflow for projects of various scales, enhancing the scalability and flexibility of RAG applications.

4.3. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning

After preparing the dataset and knowledge base, we selected Qwen2.5-Coder-7B-Instruct as the base model and performed efficient parameter fine-tuning using the LLaMA Factory—a one-stop platform for high-efficiency LLM fine-tuning. LLaMA Factory supports multiple training methods and aims to help users quickly train and fine-tune most LLM models. We adopted the LoRA method for parameter-efficient fine-tuning. Unlike traditional full-parameter tuning, LoRA introduces trainable parameters only in specific low-rank matrices, significantly reducing GPU memory usage and computational cost. This approach not only improves training efficiency but also ensures effective enhancement of the model’s generation capability under limited hardware conditions.

For the training strategy, we employed Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT), using annotated data aligned with natural language and QL code as supervision signals, enabling the model to learn the mapping from task descriptions to executable query statements. During training, we incorporated data augmentation and diversified sampling mechanisms to improve the model’s generalization across different contexts. Additionally, a validation set comprising 5% of all samples was separated from the training set to dynamically monitor model convergence and prevent overfitting. We used Swanlab real-time logging and visualization system to continuously track key metrics, such as the loss function trend and validation performance. The RoPE interpolation method was set to dynamic to accommodate longer context windows, enhancing the model’s performance when processing lengthy query inputs.

To ensure stable training, careful design was applied to the optimizer and learning rate scheduling. AdamW was chosen as the optimizer, whose effective weight decay helps mitigate overfitting. The initial learning rate for AdamW was set to 5 × , allowing rapid convergence in the early training phase. Coupled with a cosine learning rate scheduler, the learning rate gradually decreases in the later stages, ensuring stable convergence. The total number of training epochs was set to 5 to fully leverage the dataset for model convergence while avoiding overfitting from excessive training. The maximum gradient norm was clipped at 1.0 to prevent gradient explosion. Computation was performed in bf16, with a truncation length of 1200, balancing context coverage while avoiding the computational overhead of excessively long sequences.

For LoRA parameter settings, the rank was set to 8 to maximize the potential of the base model. The scaling factor was set to 16, and the probability of dropping weights randomly was 0.1, reducing dependence on a small number of parameters.

Regarding hardware utilization, distributed training and GPU memory optimization strategies were employed. Training was conducted in a multi-GPU environment using the DeepSpeed framework, fully leveraging parallel computing capabilities. Additionally, ZeRO-3 technology was applied to shard and efficiently schedule model parameters, optimizer states, and gradients, significantly reducing per-GPU memory usage and enabling the fine-tuning of a billion-parameter-scale model under limited hardware conditions.

Through this training design, the model achieved efficient convergence with limited computational resources and demonstrated high-quality generation on the validation set. This process not only validates the advantages of LoRA in large-scale language model fine-tuning but also provides a solid foundation for subsequent model inference and QL code generation.

4.4. Inference and Generation

After model training is completed, the fine-tuned model is deployed via the LLaMA Factory platform API. The workflow combining RAG and the fine-tuned model is implemented through the RAGFlow platform, allowing users to describe their query requirements in natural language. During the inference phase, the system first converts the user input into a retrieval vector and searches the CodeQL knowledge base for relevant documents. A re-ranking model is then used to reorder the retrieved knowledge, selecting the top k most relevant knowledge blocks as reference material. The user input is concatenated with these retrieved knowledge fragments to form a context input that incorporates semantic constraints and syntactic references—for example, appending typical class usage patterns and example calls to the original user requirement. This combined input is fed into the fine-tuned model, achieving both semantic enhancement and syntax constraint, thereby enabling automated generation from natural language requirements to executable QL code. Finally, the system returns the generated executable QL code to the user. If the user modifies the requirements, the system can repeat the above process, supporting interactive generation and iterative optimization.

5. Experiments and Results

This section describes the experimental setup and evaluation results of CQLLM. The experiments cover environment configuration, comparative analysis, and ablation studies. The results demonstrate the superior performance of CQLLM in vulnerability detection and CodeQL query generation.

5.1. Experimental Setting

The experiments in this study were conducted on a workstation running the Ubuntu operating system. The hardware setup included four NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada Generation GPUs, each with 48 GB of memory, totaling approximately 192 GB of GPU memory, with CUDA version 12.4. During the experiments, single-node multi-GPU training and inference were enabled to ensure efficient model execution.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method in QL code generation tasks, this study selects execution success rate and CWE coverage (CWE_cov) as the main evaluation metrics. The execution success rate refers to the proportion of QL code generated by CQLLM that can be successfully compiled and executed by CodeQL. A higher execution rate indicates that CQLLM is well-designed and capable of generating QL code that functions correctly across different environments, reflecting the model’s usability and stability.The number of distinct detected CWE types (CWEs) represents the total number of unique CWE vulnerabilities successfully detected by all generated QL codes in the vulnerability detection task. CWE coverage measures the ratio of the detected CWE types to the expected CWE types, indicating the comprehensiveness of the detection capability.The total number of detected vulnerabilities (Total_vul) records how many vulnerabilities were successfully identified in the target QL codes. QL duplication rate (QL_dr) reflects the degree of repetition among the QL codes generated by the model. It is computed based on the hash values of the generated QL files. A high duplication rate suggests that the model tends to produce template-like outputs across tasks, indicating limited diversity in generated results.To comprehensively assess model performance, this study also employs the following metrics. BLEU-4 evaluates the n-gram overlap between generated and reference code, assessing syntactic and local semantic accuracy. ROUGE-1/2/L measures the overlap of unigrams, bigrams, and the longest common subsequences between generated and reference code, reflecting structural and semantic completeness and coherence.predict_runtime records the total time taken for the model to complete generation on the entire test dataset, reflecting inference efficiency. predict_samples_per_second indicates the number of samples processed per second, measuring generation speed. predict_steps_per_second represents the number of inference steps executed per second, reflecting batch processing efficiency. predict_model_preparation_time denotes the time required for model initialization and setup. Although typically negligible, it helps quantify the overall inference process overhead. Together, these metrics enable a comprehensive evaluation of model performance from both generation quality and inference efficiency perspectives.

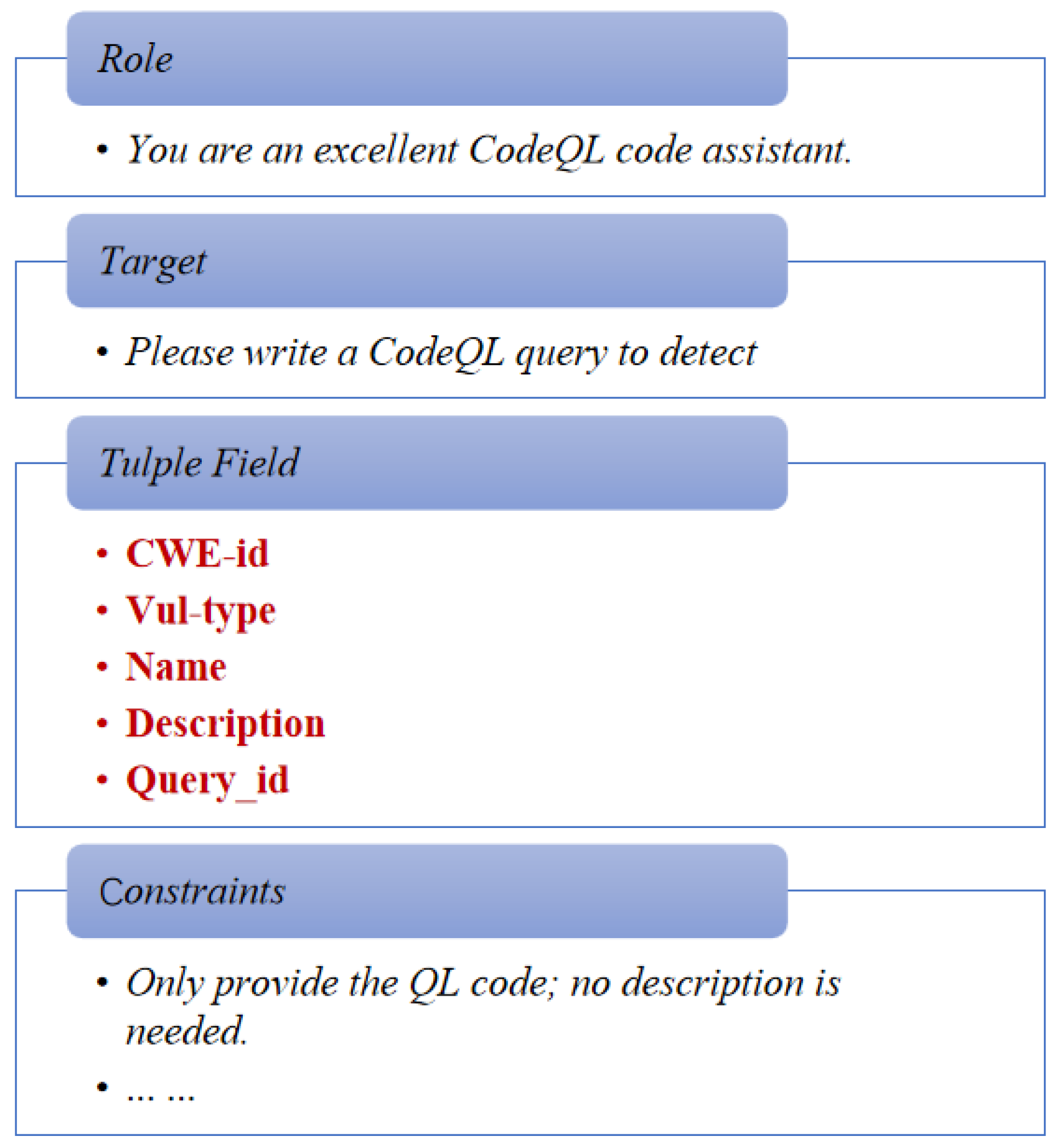

During the experiment, we implemented the collaboration between RAG and the LLM based on the RAGFlow platform to support the automatic generation of QL code. To enhance the diversity of the model’s output, the generation phase was configured with the following parameters: temperature was set to 0.7, top-p to 0.75, and max tokens to 4096, ensuring both diversity and completeness of the generated QL code. The vulnerability benchmark database used in the experiments covered 54 types of CWE vulnerabilities, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s capability to detect different categories of security issues. To evaluate the model’s ability in vulnerability query generation, we designed structured prompts to guide the model in generating CodeQL queries for specific vulnerability types. The prompt design primarily aimed to: (1) direct the model to generate correct query code according to the vulnerability type; (2) strictly limit the use of dependency libraries, ensuring that the generated code only calls the predefined library set of the experiment; and (3) guarantee reproducibility and consistency of the generated results in the experimental environment. To achieve the above goals, each vulnerability instance was organized in a five-tuple format, as shown in

Table 1, consisting of the fields CWE-id, Query_id, Name, Vul-type, and Description. Here, CWE-id denotes the vulnerability type identifier, Query_id uniquely identifies each query, Name refers to the query name, Vul-type provides a brief description of the vulnerability type, and Description gives detailed information about the vulnerability behavior and its potential impact, helping the model better understand the semantics of the vulnerability. The use of the five-tuple structure not only clearly presents the key information of each vulnerability but also facilitates the batch generation of prompts, thereby improving both experimental efficiency and standardization.

For each quintuple data entry, we constructed a templated prompt and embedded the quintuple information into it. For example, for an input validation vulnerability of type CWE-20, the structure of the prompt is shown in

Figure 5.

In practical use, we automatically convert each quintuple data entry into the corresponding prompt via a Python script and feed it into the CQLLM model. The model generates the corresponding QL code based on the prompt without producing any additional descriptive information. Furthermore, the design of the library constraints is of significant importance: on one hand, it ensures that the generated queries can be executed in the experimental environment, avoiding failures caused by calling non-existent modules or functions; on the other hand, it encourages the model to fully utilize the modules and predicates available in the known knowledge base, improving the rationality and accuracy of the generated queries. This constraint, combined with the structured information of the quintuples, makes the experiment highly controllable and reproducible, while also ensuring that the evaluation of the model’s generation capability is scientific and rigorous.

5.2. Comparative Experiment

To verify the effectiveness of the CQLLM proposed in this paper for vulnerability detection tasks, we designed comparative experiments. The experiments were divided into three groups: the Qwen2.5-coder-14B series, the Qwen2.5-coder-7B series, and the Qwen3-8B series. In each group, the original model (Noft-NoRAG) directly called the large model interface using a format compatible with the OpenAI API; the model was neither fine-tuned nor enhanced with external knowledge. The CQLLM, on the other hand, constructs a RAG workflow based on the RAGFlow platform, fine-tunes the model on vulnerability knowledge corpora, and incorporates external knowledge bases for reasoning and generation. The core comparison metrics include QL redundancy rate, the number of different CWEs detected, CWE coverage, total detected vulnerabilities, and successful execution rate, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the improvements achieved by the CQLLM over the original models.

As shown in

Table 2, under the Noft-NoRAG scenario for all three model groups, the original models were almost incapable of performing vulnerability detection. Taking Qwen2.5-coder-14B as an example, it was able to detect only 1 CWE, with a CWE coverage of just 1.90%, zero detected vulnerabilities, and a successful execution rate of 0%. Qwen2.5-coder-7B and Qwen3-8B completely failed in this scenario, with all metrics being zero.

Under the CQLLM, performance was significantly improved: Qwen2.5-coder-14B-ft-RAG detected 31 different CWEs, achieved a coverage of 57.40%, and had a successful execution rate of 58.38%, representing an order-of-magnitude increase across all metrics. Qwen2.5-coder-7B-ft-RAG showed similar improvements, detecting 29 CWEs, achieving 53.70% coverage, and maintaining a successful execution rate of 58.38%. Although Qwen3-8B-ft-RAG exhibited overall lower performance than the Qwen2.5 series, it still showed substantial improvement over the original model, with a CWE coverage of 25.90% and a successful execution rate of 47.42%.

In addition, regarding QL code redundancy, models under the CQLLM generally showed an increasing trend. For example, Qwen2.5-coder-14B had a redundancy rate of 24.30% in the ft-RAG scenario, Qwen2.5-coder-7B had 17.70%, and Qwen3-8B had 9.30%. This phenomenon indicates that while the model exhibits some patterning in its outputs when leveraging external knowledge and fine-tuning information, it simultaneously ensures the effectiveness of CWE detection.

To evaluate the performance of the models in the automated QL code generation task, we conducted assessment tests on three model series: Qwen2.5-coder-14B, Qwen2.5-coder-7B, and Qwen3-8B. This performance evaluation was carried out without incorporating RAG techniques. In the experiments, we used a pre-partitioned test dataset, and each model generated QL code for all samples, with both generation quality metrics and reasoning efficiency metrics recorded.

As shown in

Table 3, BLEU-4 and ROUGE metrics indicate that

Qwen2.5-coder-14B slightly outperforms the other models in generation quality, while

Qwen2.5-coder-7B and

Qwen3-8B perform similarly but slightly lower. In terms of reasoning efficiency, all three models exhibit comparable performance, with

predict_runtime ranging approximately between 51–53 min, and all models are able to complete the tasks reliably. Overall analysis suggests that the model parameter scale contributes to improvements in generation quality. At the same time, larger model sizes do not result in significant delays in efficiency.

From the comparative and model evaluation experiments, it is evident that the CQLLM significantly outperforms the original models. The original models, without fine-tuning or RAG, were almost incapable of completing the vulnerability detection tasks. Under the CQLLM, by integrating RAGFlow-based retrieval augmentation and domain-specific fine-tuning, the models demonstrate order-of-magnitude improvements in CWE detection capability, vulnerability coverage, and execution stability. Furthermore, the Qwen2.5 series shows the most significant performance gains under the CQLLM, whereas Qwen3-8B exhibits relatively limited improvement. This indicates that different model architectures vary in their sensitivity to retrieval augmentation and fine-tuning, providing guidance for selecting base models and optimizing the framework in future work.

In summary, the experimental results validate the effectiveness of the CQLLM in vulnerability detection tasks, with the best performance observed on the Qwen2.5-coder-14B model. This not only demonstrates the advantages of large-scale models when combined with retrieval augmentation and fine-tuning but also further confirms the applicability and value of the proposed CQLLM in the field of security analysis.

5.3. Ablation Study

To further analyze the contribution of each CQLLM component, we designed an ablation study focusing on fine-tuning and RAG. We conducted experiments using the Qwen2.5-coder-7B model under three experimental scenarios:

CQLLM (ft-RAG): Includes both fine-tuning and the RAG workflow, representing the complete CQLLM framework;

CQLLM without RAG (ft-NoRAG): Retains only fine-tuning while removing RAG retrieval augmentation, to evaluate the contribution of RAG to vulnerability detection;

CQLLM without fine-tuning (Noft-RAG): Retains only RAG retrieval augmentation while removing fine-tuning, to assess the contribution of fine-tuning to performance.

The experimental metrics include the total number of test samples, the number of successfully executed samples, the execution success rate, and the total number of detected vulnerabilities. By comparing the performance differences across the different components, we quantify the impact of each module on the vulnerability detection capability.

As shown in

Table 4, when the RAG module was removed, the number of successfully executed samples dropped to 71, with an execution success rate of only 22.11%, and the total number of detected vulnerabilities decreased to 1765. This indicates that, in the absence of RAG, fine-tuning can provide some vulnerability detection capability, but the overall performance is significantly reduced. In the scenario without fine-tuning, the model successfully executed 216 samples, achieving an execution success rate of 72.48%, and detected a total of 4755 vulnerabilities. This result demonstrates that even when only RAG is used without fine-tuning, the model is still able to detect a large number of vulnerabilities, indicating that RAG significantly enhances knowledge utilization and vulnerability coverage. Interestingly, removing fine-tuning results in a higher execution success rate but may constrain execution flexibility, suggesting that fine-tuning improves the model’s adaptability and semantic understanding of prompts, even if it slightly reduces execution efficiency.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes and implements a framework based on LLM, CQLLM, for generating executable QL code, aiming to address the insufficient accuracy of existing large models in complex code generation scenarios. For example, when a developer inputs a natural language description of a potential vulnerability, CQLLM automatically retrieves relevant CodeQL APIs and generates executable QL queries, allowing developers to detect and verify vulnerabilities more efficiently. A series of experiments validate the effectiveness of CQLLM. Experiments demonstrate that CQLLM significantly outperforms large models that are neither fine-tuned nor augmented with retrieval-enhanced generation, particularly in terms of code generation quality and vulnerability coverage. These results effectively support the hypothesis that combining RAG with fine-tuning can compensate for large models’ limitations in semantic understanding and syntax constraints in complex vulnerability scenarios. However, several areas require further improvement. First, this study uses CWE coverage as the primary evaluation metric, which only measures overall coverage across all QL codes and does not precisely locate individual samples. Future work should annotate the vulnerability database with sample-specific CWE labels to include corresponding vulnerability positions, thereby further validating the effectiveness of the generated QL code. Second, the application scope of CQLLM remains limited, as the current experiments are only conducted on existing vulnerability dependency libraries. Its ability to generate custom dependency packages still shows certain limitations. In the future, the LLM should be retrained and adapted to accommodate emerging vulnerabilities and evolving dependency environments. Finally, the original dataset for model fine-tuning is relatively small and may not comprehensively cover all vulnerability types. Subsequent work should continue to expand the QL code sample set to improve the framework’s generalization and applicability across diverse vulnerability scenarios. Moreover, CQLLM relies heavily on the capabilities of the underlying large model—the stronger the model, the better the generation results. Future research could explore integrating more powerful models to enhance framework performance. In addition, ethical considerations should be emphasized. While CQLLM provides an effective means for automating vulnerability detection, improper use of such technology may lead to malicious exploitation or unauthorized vulnerability discovery. It is, therefore, essential to ensure that the framework is applied within legitimate research and defensive security contexts.