Exploring the Impact of Socio-Economic Dynamics, Product Cost Perception on Environmental Education, and Sustainable Consumer Behavior: A Household Level Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Study Objectives

2. Literature Review

2.1. Socio-Economic Dynamics

2.2. Product Cost Perception

2.3. Environmental Education

2.4. Environmental Concern

2.5. Environmental Education, Price Consciousness, and Sustainable Consumer Behavior

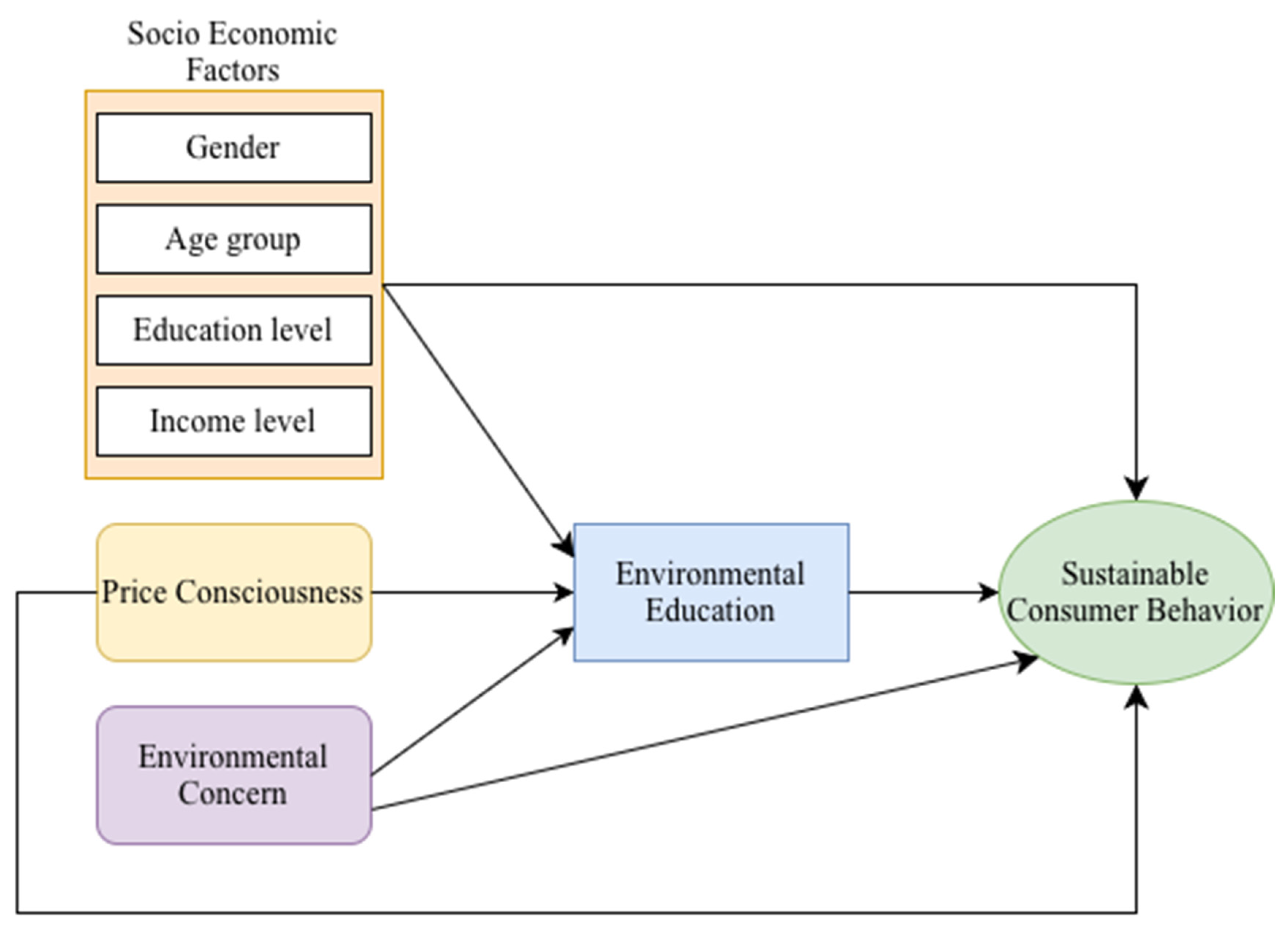

2.6. Integrated Framework

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Case and Sample

3.2. Data Collection Tool

4. Results

4.1. Scale Reliability and Measurement Quality

4.2. Bivariate Analysis

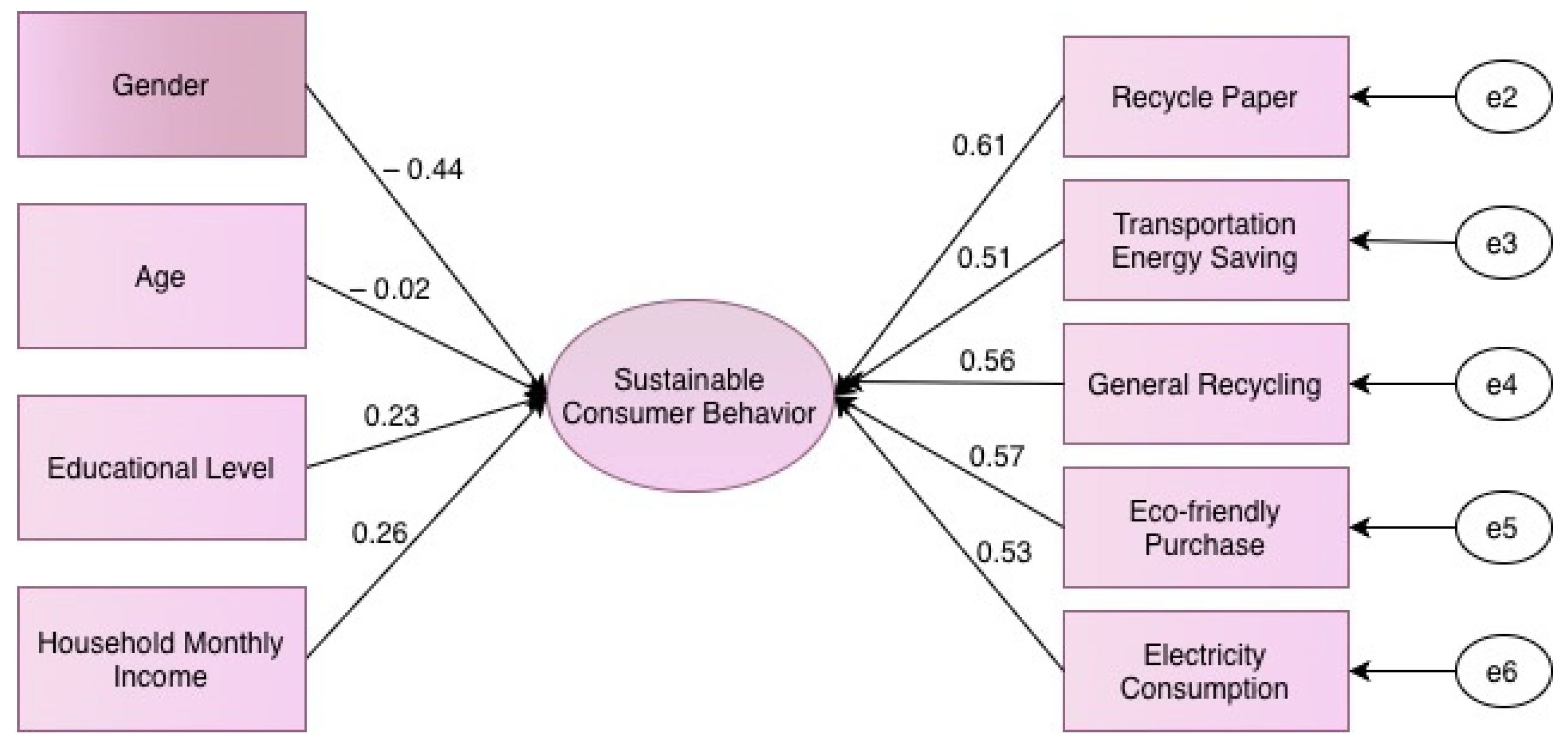

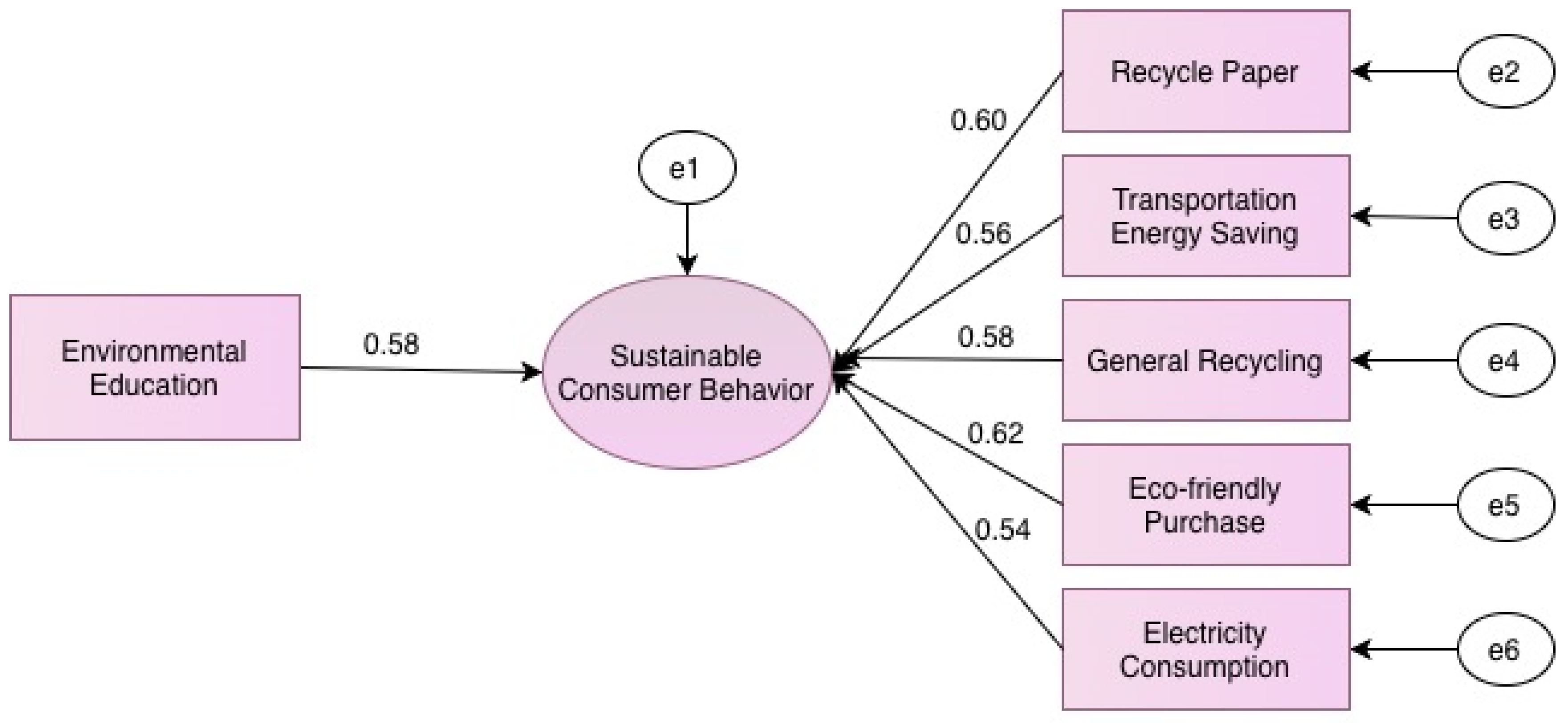

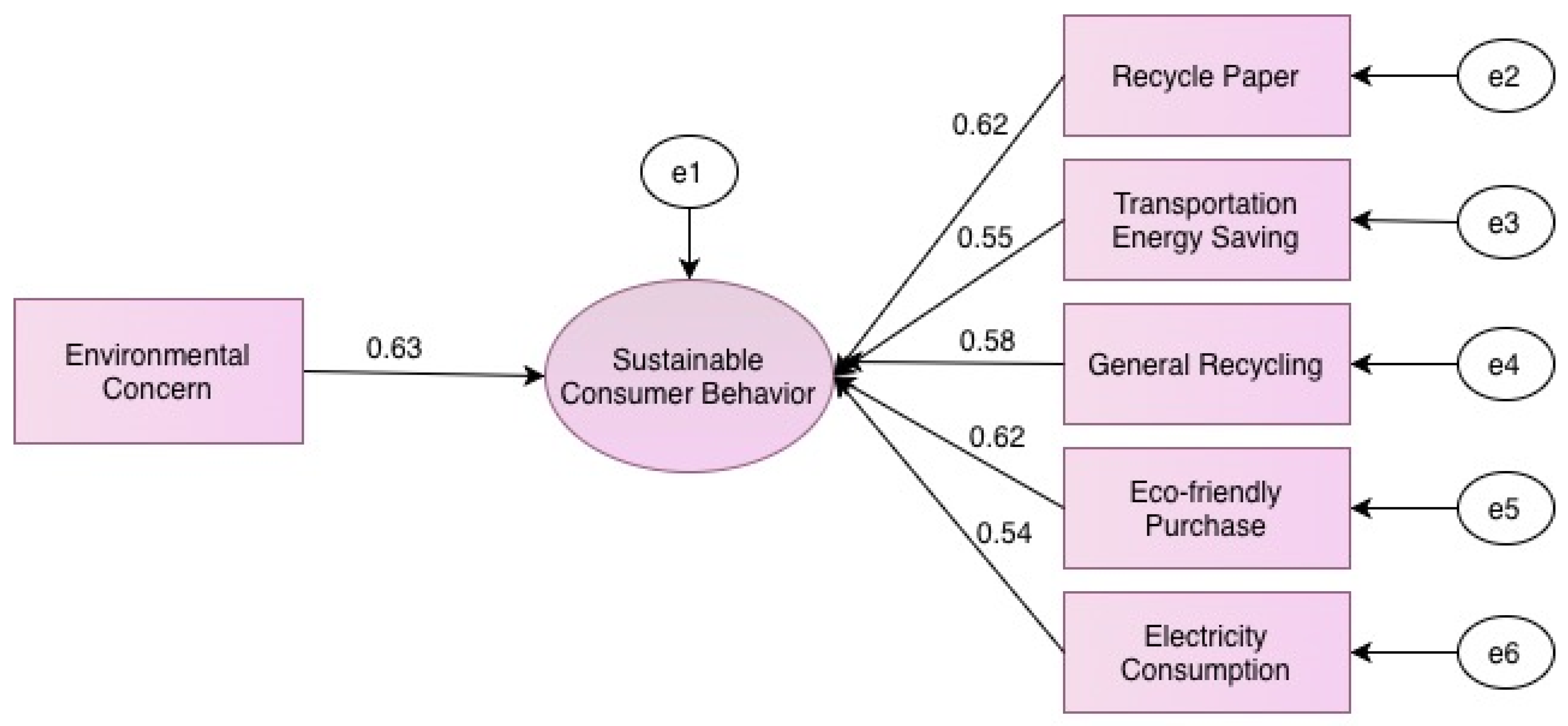

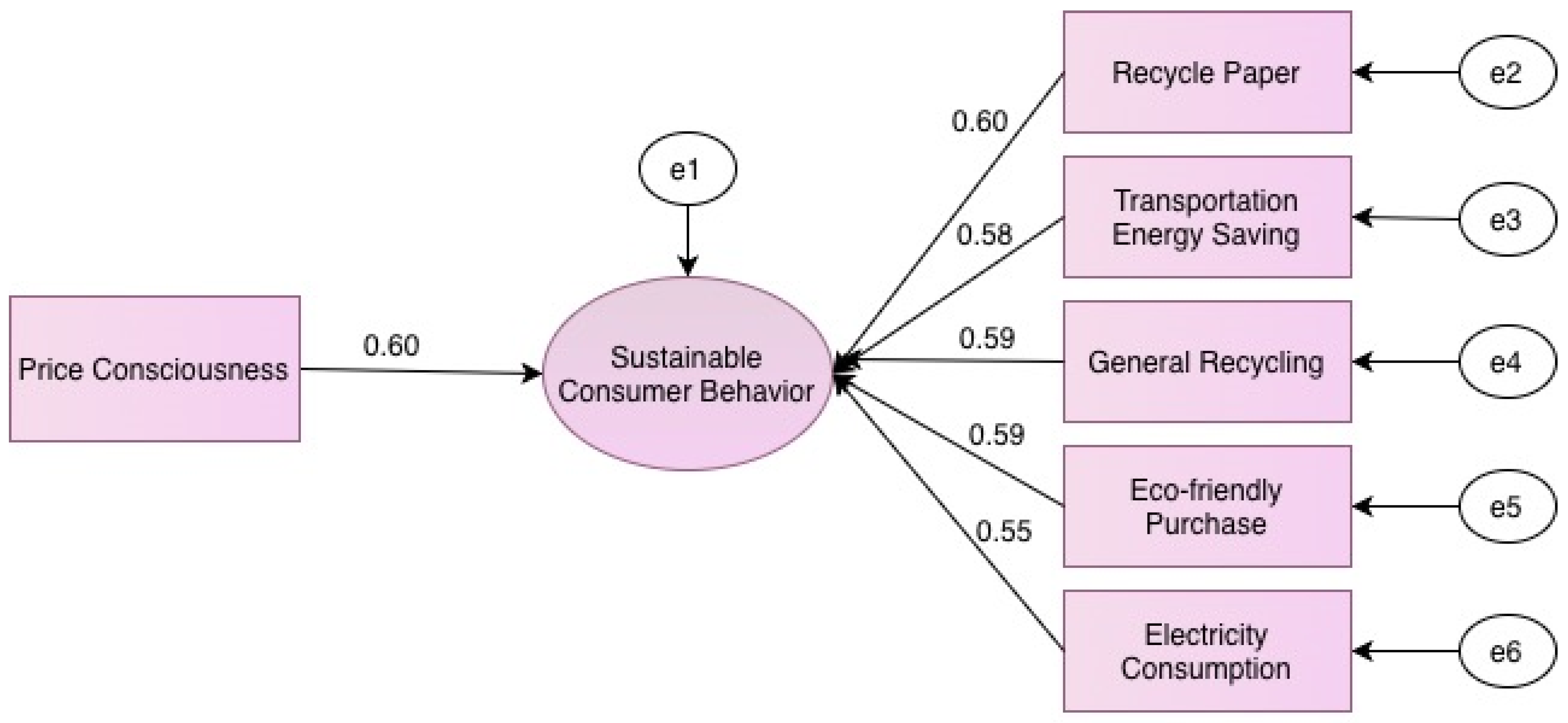

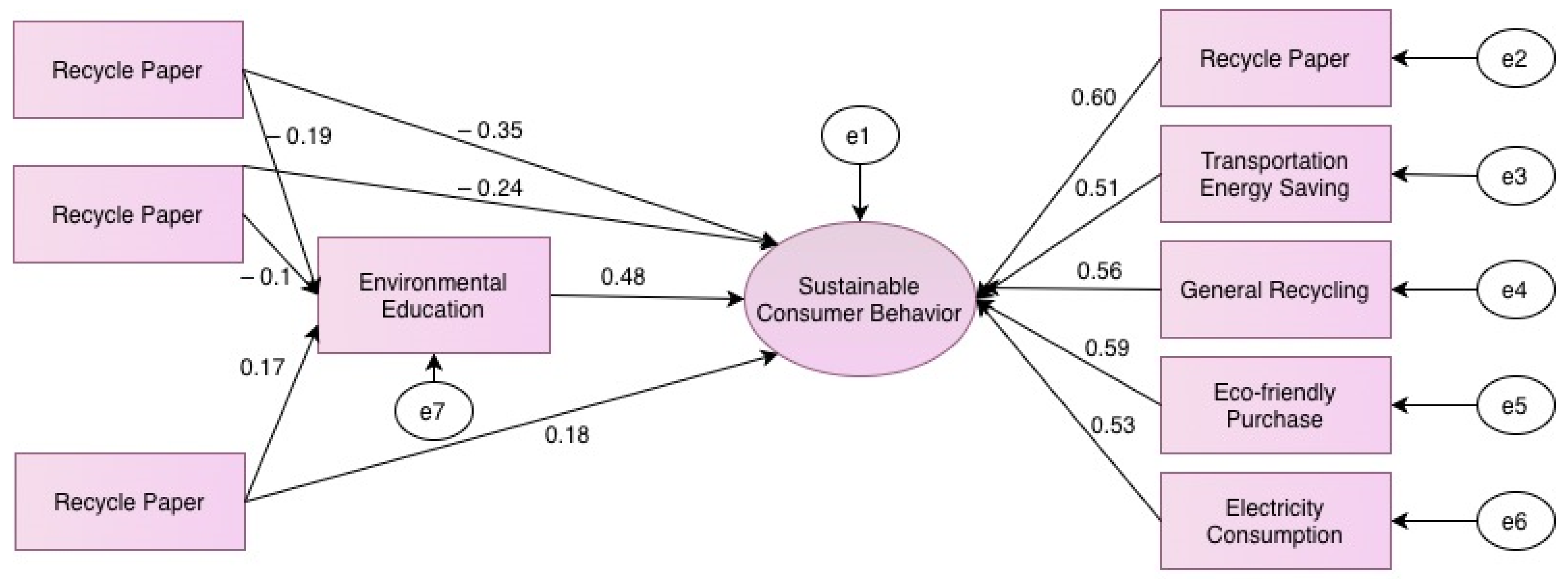

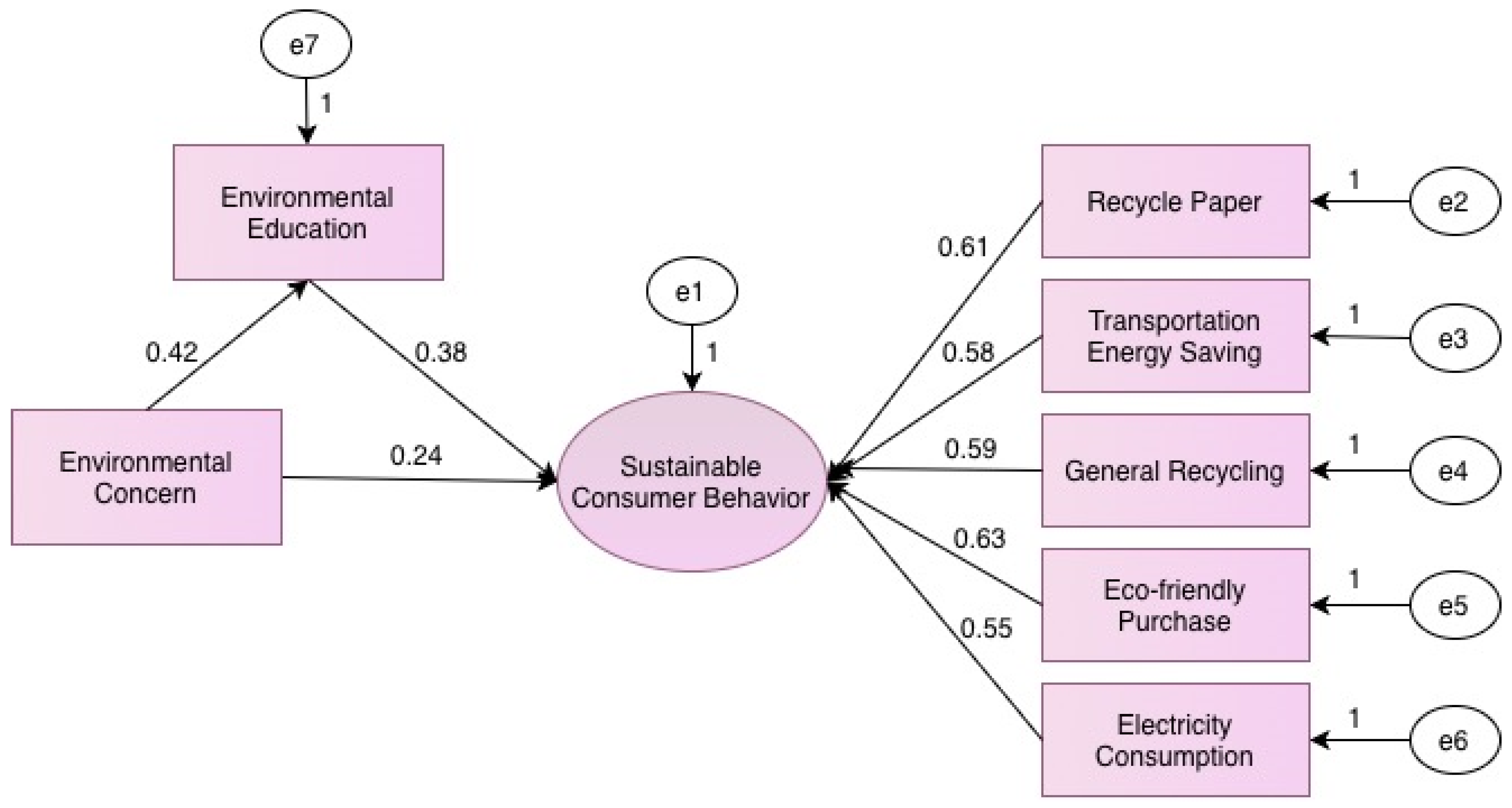

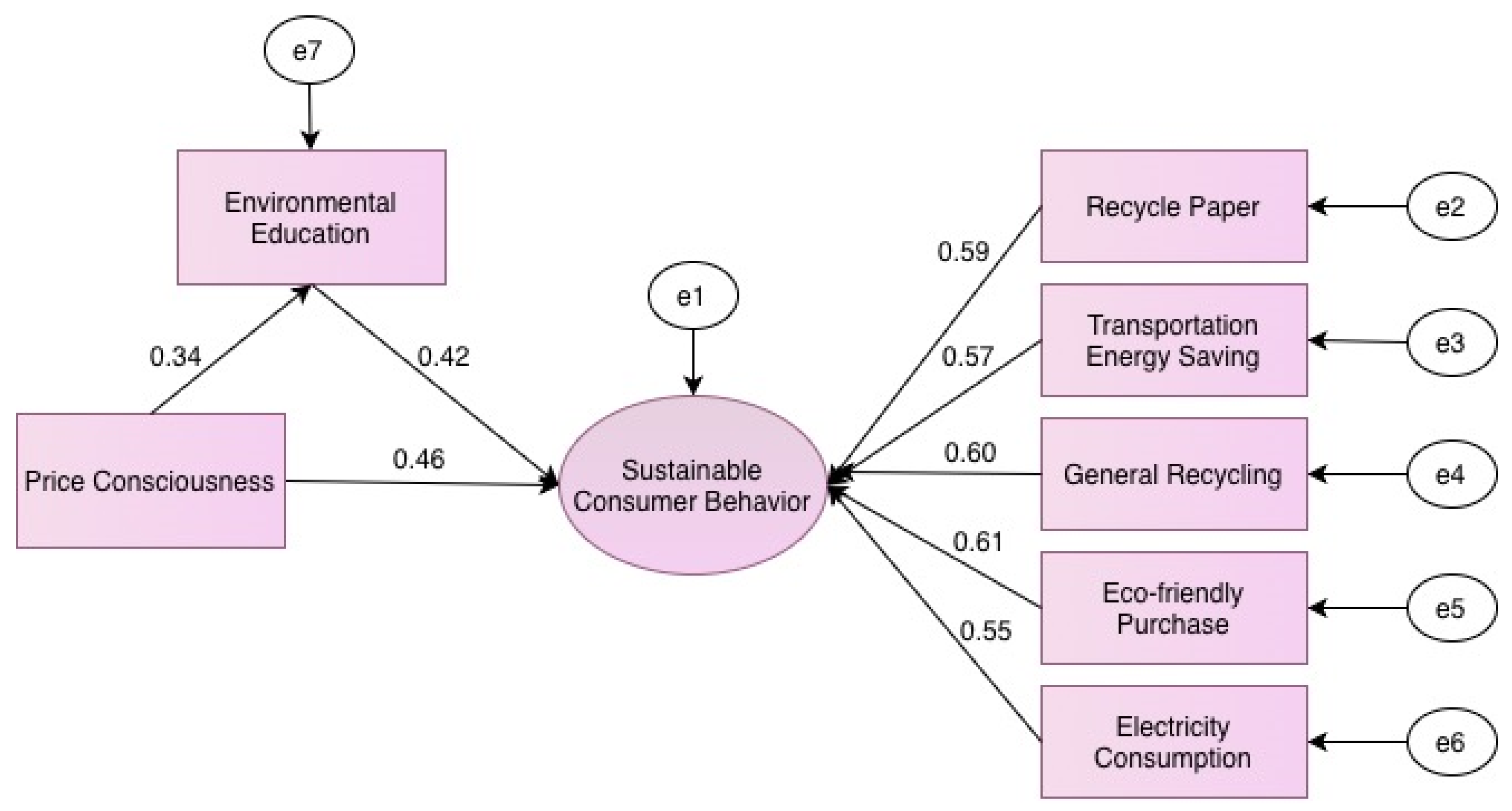

4.3. Multivariate Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. The Role of Socio-Economic Factors on Sustainable Consumer Behavior (SCB)

5.2. The Role of Environmental Education on Sustainable Consumer Behavior (SCB)

5.3. The Role of Product Cost Perception on Sustainable Consumer Behavior (SCB)

5.4. The Role of Environmental Concern on Sustainable Consumer Behavior (SCB)

5.5. Interpretation in the Libyan Socio-Economic Context

5.6. Limitations

6. Conclusions

6.1. Recommendations

6.2. Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hunjra, A.I.; Bouri, E.; Azam, M.; Azam, R.I.; Dai, J. Economic growth and environmental sustainability in developing economies. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 70, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, A.; Huang, Y.; Khan, K.; Cifuentes-Faura, J. Innovation, institutions, and sustainability: Evaluating drivers of household green technology adoption and environmental sustainability of Africa. Gondwana Res. 2024, 132, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, O.A.; Jimoh, A.A.; Abdullah, K.A.; Bello, B.A.; Awoyemi, E.D. Economic and environmental impact of energy audit and efficiency: A report from a Nigeria household. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2024, 79, 101387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, Y.; Zheng, G.; Zhou, Y. Interaction between household energy consumption and health: A systematic review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 113859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdunnabi, M.; Etiab, N.; Nassar, Y.F.; El-Khozondar, H.J.; Khargotra, R. Energy savings strategy for the residential sector in Libya and its impacts on the global environment and the nation economy. Adv. Build. Energy Res. 2023, 17, 379–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azubike, V.C.; Gatiesh, M.M. The intricate goal of energy security and energy transition: Considerations for Libya. Energy Policy 2024, 187, 114005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran, P.; Trafimow, D.; Armitage, C.J. Predicting behaviour from perceived behavioural control: Tests of the accuracy assumption of the theory of planned behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 42, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiratsuka, J.; Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. Testing VBN theory in Japan: Relationships between values, beliefs, norms, and acceptability and expected effects of a car pricing policy. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 53, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickinson, M. Learners and learning in environmental education: A critical review of the evidence. Environ. Educ. Res. 2001, 7, 207–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela-Candamio, L.; Novo-Corti, I.; García-Álvarez, M.T. The importance of environmental education in the determinants of green behavior: A meta-analysis approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1565–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, H.M.; Khan, I.; Latif, M.I.; Komal, B.; Chen, S. Understanding the dynamics of natural resources rents, environmental sustainability, and sustainable economic growth: New insights from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 58746–58761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, S.I.; Kusi-Sarpong, S. Identifying and exploring the relationship among the critical success factors of sustainability toward consumer behavior. J. Model. Manag. 2024, 19, 492–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcărea, T.; Ioan-Franc, V.; Ionescu, Ş.A.; Purcărea, I.M.; Purcărea, V.L.; Purcărea, I.; Mateescu-Soare, M.C.; Platon, O.-E.; Orzan, A.-O. Major shifts in sustainable consumer behavior in Romania and retailers’ priorities in agilely adapting to it. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topić, M.; Kostopoulos, I.; Krstić, M. Sustainability, sociodemographic differences, and consumer behavior. Am. Behav. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nuaimi, S.R.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Sustainable consumption and education for sustainability in higher education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsten, F.; Eligius Biyase, M. Environmental perceptions and sustainable consumption behavior: The disparity among South Africans. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Wang, J. The impact of pro-environmental awareness components on green consumption behavior: The moderation effect of consumer perceived cost, policy incentives, and face culture. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 580823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addae-Dapaah, K.; Wilkinson, J. Green premium: What is the implied prognosis for sustainability? J. Sustain. Real Estate 2020, 12, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusyani, E.; Lavuri, R.; Gunardi, A. Purchasing eco-sustainable products: Interrelationship between environmental knowledge, environmental concern, green attitude, and perceived behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, S. “I buy green products for my benefits or yours”: Understanding consumers’ intention to purchase green products. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022, 34, 1721–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zameer, H.; Yasmeen, H. Green innovation and environmental awareness driven green purchase intentions. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2022, 40, 624–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta Castellanos, P.M.; Queiruga-Dios, A. From environmental education to education for sustainable development in higher education: A systematic review. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 23, 622–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, A.; Zaheer Zaidi, S.S.; Islam, T. An investigation of sustainable consumption behavior: The influence of environmental concern and trust in sustainable producers on consumer xenocentrism. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2023, 34, 771–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVille, N.V.; Tomasso, L.P.; Stoddard, O.P.; Wilt, G.E.; Horton, T.H.; Wolf, K.L.; Brymer, E.; Kahn, P.H.; James, P. Time spent in nature is associated with increased pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.R.; Streimikiene, D.; Qadir, H.; Streimikis, J. Effect of green marketing mix, green customer value, and attitude on green purchase intention: Evidence from the USA. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 11473–11495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B.; Gangwar, V.P.; Dash, G. Green marketing strategies, environmental attitude, and green buying intention: A multi-group analysis in an emerging economy context. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Lee, K. Environmental consciousness, purchase intention, and actual purchase behavior of eco-friendly products: The moderating impact of situational context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj, A.; Taneja, S.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Luthra, S.; Kumar, A. Hey, did you see that label? It’s sustainable!: Understanding the role of sustainable labelling in shaping sustainable purchase behaviour for sustainable development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 2820–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boermans, D.D.; Jagoda, A.; Lemiski, D.; Wegener, J.; Krzywonos, M. Environmental awareness and sustainable behavior of respondents in Germany, the Netherlands and Poland: A qualitative focus group study. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Cui, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, M.; Zhou, Y. Study on consumers’ motivation to buy green food based on meta-analysis. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1405787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea, H.R.; Piedrahita, A.R.; Alzate, Ó.E.T. Models of environmental awareness: Exploring their nature and role in environmental education–a systematic review. Heliyon 2025, 11, e43679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, Y.F.; El-Khozondar, H.J.; Alatrash, A.A.; Ahmed, B.A.; Elzer, R.S.; Ahmed, A.A.; Imbayah, I.I.; Alsharif, A.H.; Khaleel, M.M. Assessing the viability of solar and wind energy technologies in semi-arid and arid regions: A case study of Libya’s climatic conditions. Appl. Sol. Energy 2024, 60, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammari, A.M.; Roosli, R. A Review of Prefabricated Housing Evolution, Challenges, and Prospects Towards Sustainable Development in Libya. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2024, 19, 1181–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kezeiri, S.; Lawless, R. Economic Development and Spatial Planning in Libya. In The Economic Development of Libya; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Burgat, F. The Libyan economy in crisis. In The Economic Development of Libya; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 213–227. [Google Scholar]

- Surya, B.; Hadijah, H.; Suriani, S.; Baharuddin, B.; Fitriyah, A.T.; Menne, F.; Rasyidi, E.S. Spatial transformation of a new city in 2006–2020: Perspectives on the spatial dynamics, environmental quality degradation, and socio—Economic sustainability of local communities in Makassar City, Indonesia. Land 2020, 9, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levrini, G.R.; Jeffman Dos Santos, M. The influence of price on purchase intentions: Comparative study between cognitive, sensory, and neurophysiological experiments. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W.; Gaillard, E. Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 241, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Naushad, M.; Govarthanan, M.; Iqbal, J.; Alfadul, S.M. Emerging contaminants of high concern for the environment: Current trends and future research. Environ. Res. 2022, 207, 112609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Sheng, G.; She, S.; Xu, J. Impact of consumer environmental responsibility on green consumption behavior in China: The role of environmental concern and price sensitivity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravinder, E.B.; Saraswathi, A.B. Literature review of Cronbach alpha coefficient (A) and Mcdonald’s omega coefficient (Ω). Eur. J. Mol. Clin. Med. 2020, 7, 2943–2949. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, S.; Warren, M.A. Exploring the role of character strengths in the endorsement of gender equality and pro-environmental action in the UAE. Middle East J. Posit. Psychol. 2021, 7, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, T.; Ji, Q.; Lucey, B. Awareness, energy consumption and pro-environmental choices of Chinese households. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, X.; Managi, S. Determinants of pro-environmental behaviour: Effects of socioeconomic, subjective, and psychological well-being factors from 37 countries. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Li, L.M.W. The relationship of environmental concern with public and private pro-environmental behaviours: A pre-registered meta-analysis. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 53, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, R.; White, K.; Hardisty, D.J.; Zhao, J. Shifting consumer behavior to address climate change. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 42, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Items | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Education | 13 | 0.87 |

| Environmental Concern | 15 | 0.90 |

| Price Consciousness | 4 | 0.79 |

| Sustainable Consumer Behavior | 30 | 0.88 |

| Frequency (f) | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 258 | 51.6 |

| Male | 242 | 48.4 |

| Age | ||

| 21–30 years | 117 | 23.4 |

| 31–40 years | 108 | 21.6 |

| 41–50 years | 136 | 27.2 |

| 51 and above | 139 | 27.8 |

| Educational level | ||

| High school | 177 | 35.4 |

| Bachelor | 159 | 31.8 |

| MSc/PhD | 164 | 32.8 |

| Household monthly income | ||

| Less than LYD 1000 | 96 | 19.2 |

| Between LYD 1001 and 3000 | 138 | 27.6 |

| Between LYD 3001 and 6000 | 150 | 30 |

| Above LYD 6001 | 116 | 23.2 |

| Total | 500 | 100 |

| n | s | Min | Max | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Education | 500 | 37.17 | 3.67 | 27 | 48 |

| Environmental Concern | 500 | 47.64 | 5.77 | 31 | 63 |

| Price Consciousness | 500 | 12.18 | 2.74 | 5 | 24 |

| n | s | Min | Max | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recycle Paper | 500 | 8.36 | 2.69 | 0 | 18 |

| Transportation Energy Saving | 500 | 7.56 | 1.91 | 1 | 13 |

| General Recycling | 500 | 17.73 | 3.15 | 8 | 28 |

| Eco-Friendly Purchase | 500 | 34.81 | 5.28 | 18 | 52 |

| Electricity Consumption | 500 | 21.58 | 3.21 | 13 | 32 |

| Kolmogorov–Smirnov | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| İst. | sd | p | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

| Environmental Education | 0.061 | 500 | 0.000 | 0.039 | 0.145 |

| Environmental Concern | 0.057 | 500 | 0.001 | 0.016 | −0.289 |

| Price Consciousness | 0.103 | 500 | 0.000 | 0.105 | 0.448 |

| Recycle Paper | 0.091 | 500 | 0.000 | −0.056 | 0.069 |

| Transportation Energy Saving | 0.119 | 500 | 0.000 | −0.061 | 0.078 |

| General Recycling | 0.070 | 500 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.103 |

| Eco-Friendly Purchase | 0.049 | 500 | 0.006 | −0.073 | 0.052 |

| Electricity Consumption | 0.076 | 500 | 0.000 | 0.104 | 0.115 |

| Gender | n | s | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recycle Paper | Female | 258 | 9.29 | 2.52 | 8.642 | 0.000 * |

| Male | 242 | 7.36 | 2.49 | |||

| Transportation Energy Saving | Female | 258 | 7.99 | 1.96 | 5.371 | 0.000 * |

| Male | 242 | 7.10 | 1.75 | |||

| General Recycling | Female | 258 | 18.78 | 2.99 | 8.142 | 0.000 * |

| Male | 242 | 16.62 | 2.92 | |||

| Eco-Friendly Purchase | Female | 258 | 36.20 | 5.30 | 6.306 | 0.000 * |

| Male | 242 | 33.33 | 4.85 | |||

| Electricity Consumption | Female | 258 | 22.46 | 3.13 | 6.599 | 0.000 * |

| Male | 242 | 20.64 | 3.02 |

| Age Group | n | s | Min | Max | F | p | Dif. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recycle Paper | 21–30 years | 117 | 8.39 | 2.36 | 1 | 15 | 0.392 | 0.759 | |

| 31–40 years | 108 | 8.22 | 2.57 | 0 | 14 | ||||

| 41–50 years | 136 | 8.24 | 2.77 | 2 | 15 | ||||

| 51 and above | 139 | 8.54 | 2.95 | 1 | 18 | ||||

| Transportation Energy Saving | 21–30 years | 117 | 7.62 | 1.89 | 3 | 12 | 1.852 | 0.137 | |

| 31–40 years | 108 | 7.64 | 1.84 | 1 | 13 | ||||

| 41–50 years | 136 | 7.24 | 1.86 | 3 | 13 | ||||

| 51 and above | 139 | 7.76 | 2.01 | 3 | 13 | ||||

| General Recycling | 21–30 years | 117 | 17.97 | 3.17 | 10 | 26 | 0.314 | 0.816 | |

| 31–40 years | 108 | 17.65 | 2.93 | 11 | 28 | ||||

| 41–50 years | 136 | 17.70 | 3.30 | 10 | 25 | ||||

| 51 and above | 139 | 17.63 | 3.16 | 8 | 25 | ||||

| Eco-Friendly Purchase | 21–30 years | 117 | 34.32 | 5.15 | 23 | 48 | 2.692 | 0.046 * | 1–4 |

| 31–40 years | 108 | 34.47 | 5.47 | 18 | 46 | ||||

| 41–50 years | 136 | 34.41 | 5.38 | 19 | 52 | ||||

| 51 and above | 139 | 35.88 | 5.04 | 23 | 49 | ||||

| Electricity Consumption | 21–30 years | 117 | 21.62 | 2.85 | 13 | 29 | 3.663 | 0.012 * | 3–4 |

| 31–40 years | 108 | 21.67 | 3.12 | 14 | 30 | ||||

| 41–50 years | 136 | 20.89 | 3.40 | 13 | 31 | ||||

| 51 and above | 139 | 22.15 | 3.27 | 13 | 32 |

| Education | n | s | Min | Max | F | p | Dif. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recycle Paper | High school | 177 | 7.14 | 2.66 | 0 | 12 | 31.774 | 0.000 * | 1–2 |

| Bachelor | 159 | 9.04 | 2.32 | 4 | 18 | 1–3 | |||

| MSc/PhD | 164 | 9.01 | 2.59 | 4 | 15 | ||||

| Transportation Energy Saving | High school | 177 | 6.88 | 1.89 | 1 | 11 | 20.156 | 0.000 * | 1–2 |

| Bachelor | 159 | 8.11 | 1.77 | 4 | 13 | 1–3 | |||

| MSc/PhD | 164 | 7.76 | 1.85 | 4 | 13 | ||||

| General Recycling | High school | 177 | 16.59 | 3.04 | 8 | 23 | 19.811 | 0.000 * | 1–2 |

| Bachelor | 159 | 18.53 | 3.11 | 11 | 26 | 1–3 | |||

| MSc/PhD | 164 | 18.19 | 2.95 | 11 | 28 | ||||

| Eco-Friendly Purchase | High school | 177 | 32.63 | 5.18 | 18 | 43 | 27.239 | 0.000 * | 1–2 |

| Bachelor | 159 | 36.47 | 5.06 | 27 | 52 | 1–3 | |||

| MSc/PhD | 164 | 35.56 | 4.81 | 25 | 46 | ||||

| Electricity Consumption | High school | 177 | 20.22 | 3.10 | 13 | 27 | 27.732 | 0.000 * | 1–2 |

| Bachelor | 159 | 22.50 | 2.99 | 16 | 32 | 1–3 | |||

| MSc/PhD | 164 | 22.15 | 3.04 | 16 | 30 |

| Monthly Income | n | s | Min | Max | F | p | Dif. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recycle Paper | Less than LYD 1000 | 96 | 6.47 | 2.75 | 0 | 12 | 22.020 | 0.000 * | 1–2 |

| LYD 1001 to 3000 | 138 | 8.81 | 2.47 | 4 | 15 | 1–3 | |||

| LYD 3001 to 6000 | 150 | 8.81 | 2.46 | 4 | 18 | 1–4 | |||

| Above LYD 6001 | 116 | 8.79 | 2.50 | 3 | 15 | ||||

| Transportation Energy Saving | Less than LYD 1000 | 96 | 6.70 | 1.81 | 1 | 11 | 8.515 | 0.000 * | 1–2 |

| LYD 1001 to 3000 | 138 | 7.82 | 1.98 | 3 | 13 | 1–3 | |||

| LYD 3001 to 6000 | 150 | 7.71 | 1.81 | 3 | 13 | 1–4 | |||

| Above LYD 6001 | 116 | 7.77 | 1.85 | 3 | 13 | ||||

| General Recycling | Less than LYD 1000 | 96 | 16.29 | 3.41 | 8 | 24 | 8.919 | 0.000 * | 1–2 |

| LYD 1001 to 3000 | 138 | 17.93 | 3.41 | 10 | 28 | 1–3 | |||

| LYD 3001 to 6000 | 150 | 18.07 | 2.96 | 11 | 26 | 1–4 | |||

| Above LYD 6001 | 116 | 18.25 | 2.45 | 13 | 25 | ||||

| Eco-Friendly Purchase | Less than LYD 1000 | 96 | 31.50 | 6.23 | 18 | 45 | 18.135 | 0.000 * | 1–2 |

| LYD 1001 to 3000 | 138 | 35.25 | 4.47 | 26 | 48 | 1–3 | |||

| LYD 3001 to 6000 | 150 | 35.41 | 4.70 | 26 | 52 | 1–4 | |||

| Above LYD 6001 | 116 | 36.26 | 4.97 | 25 | 49 | ||||

| Electricity Consumption | Less than LYD 1000 | 96 | 19.51 | 3.18 | 13 | 26 | 18.498 | 0.000 * | 1–2 |

| LYD 1001 to 3000 | 138 | 22.07 | 3.13 | 16 | 31 | 1–3 | |||

| LYD 3001 to 6000 | 150 | 21.92 | 2.90 | 16 | 29 | 1–4 | |||

| Above LYD 6001 | 116 | 22.27 | 3.03 | 16 | 32 |

| Environmental Education | Environmental Concern | Price Consciousness | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recycle Paper | r | 0.332 * | 0.405 * | 0.343 * |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 500 | 500 | 500 | |

| Transportation Energy Saving | r | 0.299 * | 0.316 * | 0.350 * |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 500 | 500 | 500 | |

| General Recycling | r | 0.353 * | 0.372 * | 0.387 * |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 500 | 500 | 500 | |

| Eco-Friendly Purchase | r | 0.393 * | 0.418 * | 0.346 * |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 500 | 500 | 500 | |

| Electricity Consumption | r | 0.304 * | 0.320 * | 0.334 * |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 500 | 500 | 500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abdullah, K.S.B.; Kiraz, A. Exploring the Impact of Socio-Economic Dynamics, Product Cost Perception on Environmental Education, and Sustainable Consumer Behavior: A Household Level Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010512

Abdullah KSB, Kiraz A. Exploring the Impact of Socio-Economic Dynamics, Product Cost Perception on Environmental Education, and Sustainable Consumer Behavior: A Household Level Analysis. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):512. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010512

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdullah, Kareemah Sh Basheer, and Askin Kiraz. 2026. "Exploring the Impact of Socio-Economic Dynamics, Product Cost Perception on Environmental Education, and Sustainable Consumer Behavior: A Household Level Analysis" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010512

APA StyleAbdullah, K. S. B., & Kiraz, A. (2026). Exploring the Impact of Socio-Economic Dynamics, Product Cost Perception on Environmental Education, and Sustainable Consumer Behavior: A Household Level Analysis. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010512