Energy Management Revolution in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Using Deep Learning Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of UAV Industry and Applications

1.2. Energy Management Challenges in UAVs

1.3. The Role of Deep Learning in Modern UAV Systems

2. Background and Literature Review

2.1. Traditional Energy Management in UAVs

2.2. Evolution of Deep Learning Applications in UAVs

2.3. State of the Art in Energy Optimization Techniques

2.4. Research Gaps and Opportunities

3. Deep Learning Approaches in UAV Energy Management

3.1. Deep Reinforcement Neural Network Architectures for Energy Optimization

3.2. Reinforcement Learning for Flight Path Optimization

3.3. Predictive Models for Energy Management

3.4. Real-Time Decision-Making Systems

3.4.1. Deep Learning-Enabled Real-Time Decision Frameworks

3.4.2. Energy-Efficient Adaptive Path Planning

3.4.3. Dynamic Power Management in Communication Networks

4. Implementation Strategies

4.1. UAV-Assisted 5G Communication Network

4.2. Integration Challenges and Solutions

- is the energy consumption (joules);

- is the energy mechanical (joules);

- is the energy communication (joules);

- is the vertical speed (m/s);

- is the propulsion efficiency;

- is the mass of the UAV (kg);

- is the Earth’s gravitational force, equal to 9.81 m/s2;

- is the transmission power of the wireless communication signal (watts);

- is the time spent on wireless communication (seconds);

- is the weighted value of the user’s bandwidth demand;

- is the user’s bandwidth demand (bps).

4.3. Reinforcement Learning Framework Specification

- (a)

- State Space: The state vector represents UAV environmental and operational parameters as , where is the UAV’s altitude, is the velocity, is the remining power, is the number of active users, is the signal-to-noise ratio, is the distance to the nearest base station, and is the available bandwidth.

- (b)

- Action Space: The action vector defines the adjustment to UAV altitude, the transmission power, and the dynamic energy weight . All actions are continuous and bounded within the UAV’s physical limits.

- (c)

- Reward Function: The reward function aims to jointly optimize energy efficiency and communication throughput, formulated aswhere is the instantaneous energy consumption, represents the transmitted bits, and is the throughput. The weighting coefficients are equal to 0.6 and 0.4, respectively. is the penalty factor (0.1) for violating Quality of Service constraints in order to balance between energy efficiency and transmission quality. This reward structure encourages the UAV to maintain optimal trade-offs between low energy consumption and high transmission quality, ensuring stable convergence in multi-user environments.

- (d)

- Network Architecture: The policy and critic networks both comprise three fully connected layers with 128, 256, and 128 neurons, respectively, each using ReLU activation, and batch normalization is applied to prevent overfitting and accelerate convergence. Weights are trained on an NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU (Santa Clara, CA, USA), and the Adam optimizer (learning rate = 1 × 10−4) is used.

- (e)

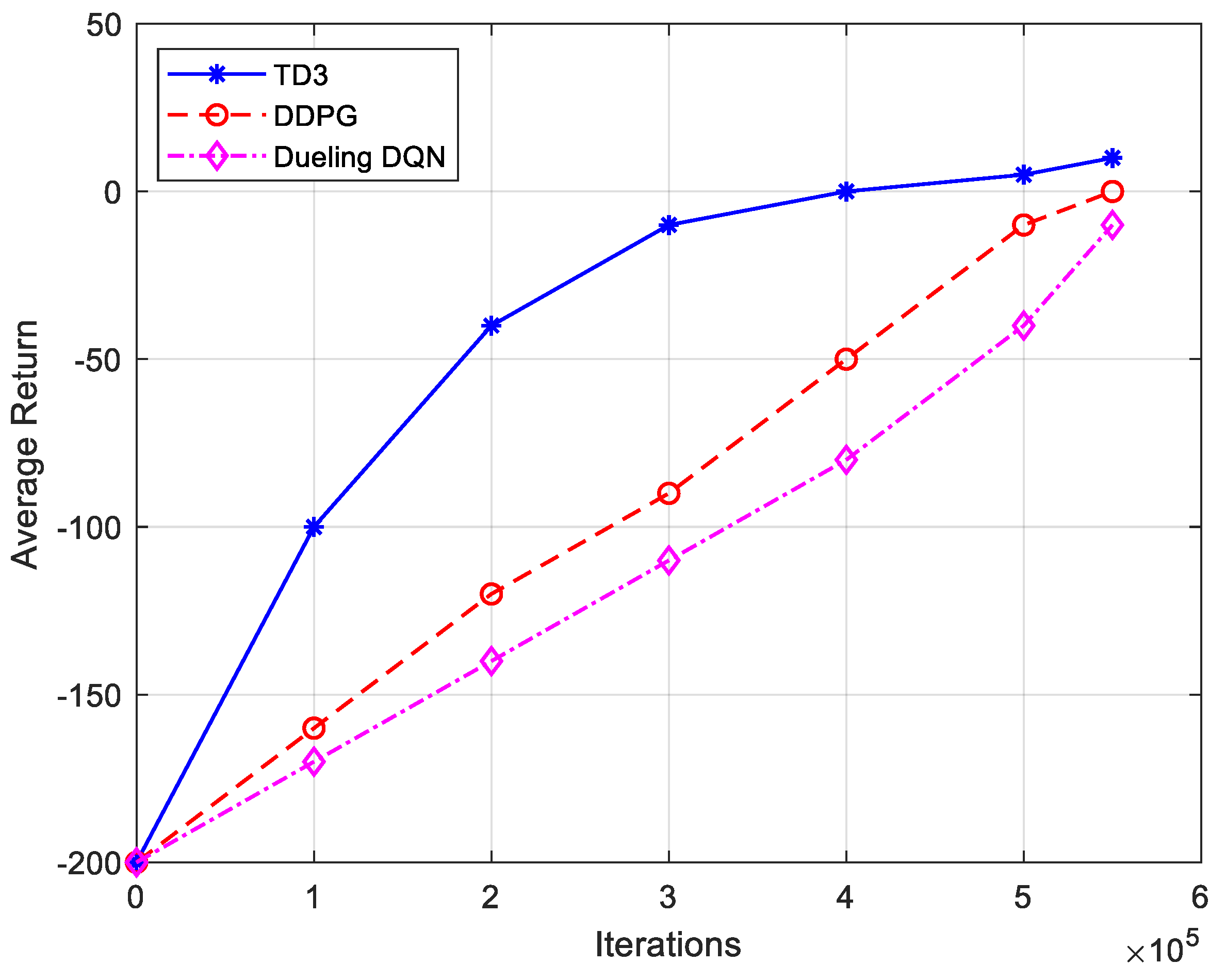

- Training Procedure: The model is trained on a hybrid dataset comprising simulated data equal to 10,000 flight instances, generated from a MATLABMATLAB R2024b-based trajectory and power models across varying environmental conditions. Experimental data from 2000 records are collected via field trials using a Yuneec H520 UAV (Yuneec International, Shanghai, China) equipped with telemetry and CSI sensors. Data are normalized to the range [0, 1], and each sample sequence consists of 30 temporal steps for recurrent learning. Training continues with 50,000 episodes, with early stopping triggered when the validation loss fails to improve over 10 consecutive epochs. The typical training time is approximately 12 h. The final trained model demonstrates stable policy behavior with Q-value reduction variance consistently below 0.02. The proposed DRNN–TD3 model demonstrates faster convergence (≈40% fewer iterations) and improves energy efficiency by 21% relative to DDPG and 27% relative to Dueling DQN with identical training with an average return greater than or equal to −10, as shown in Figure 3.

4.4. Experimental Procedure and Simulation Configuration

4.5. Performance Analysis in Experimental Design

- is the average successful data transmission rate (Mbps);

- is the maximum segment size (Mb);

- is the round trip time, the time required for a data packet to traverse the network from transmitter to receiver and return to the transmitter, measured in seconds (s);

- is the packet loss probability.

4.6. Statistical Validation

- (1)

- Sensor Precision: Telemetry logs of UAV altitude, velocity, and power were sampled at 10 Hz with ±0.5 m accuracy in altitude and ±0.05 m/s in velocity, leading to an estimated uncertainty of ±1.8% in the energy calculation.

- (2)

- Environmental Variability: The ambient air density and drag coefficient fluctuated with temperature and wind speed; Monte Carlo perturbation over 500 runs yielded a propagated uncertainty of ±2.3% in drag powe

- (3)

- Model Approximation: Aerodynamic coefficients and communication power parameters were fitted based on empirical regression curves; cross-validation against field data introduced an additional ±2.0% uncertainty in energy consumption predictions.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Clarification of Energy-Efficiency Metrics and Validation of Numerical Results

5.2. Comparative Innovation and Methodological Distinction

- (1)

- Hybrid Model Integration: Unlike traditional DRL architectures that rely solely on feed-forward or LSTM networks, our approach employs a Deep Recurrent Neural Network (DRNN) to capture the temporal correlations of UAV state transitions (e.g., altitude, velocity, and transmission power fluctuations). This enables the dynamic learning of long-term dependencies between flight dynamics and communication energy efficiency, an aspect rarely incorporated into prior UAV energy models.

- (2)

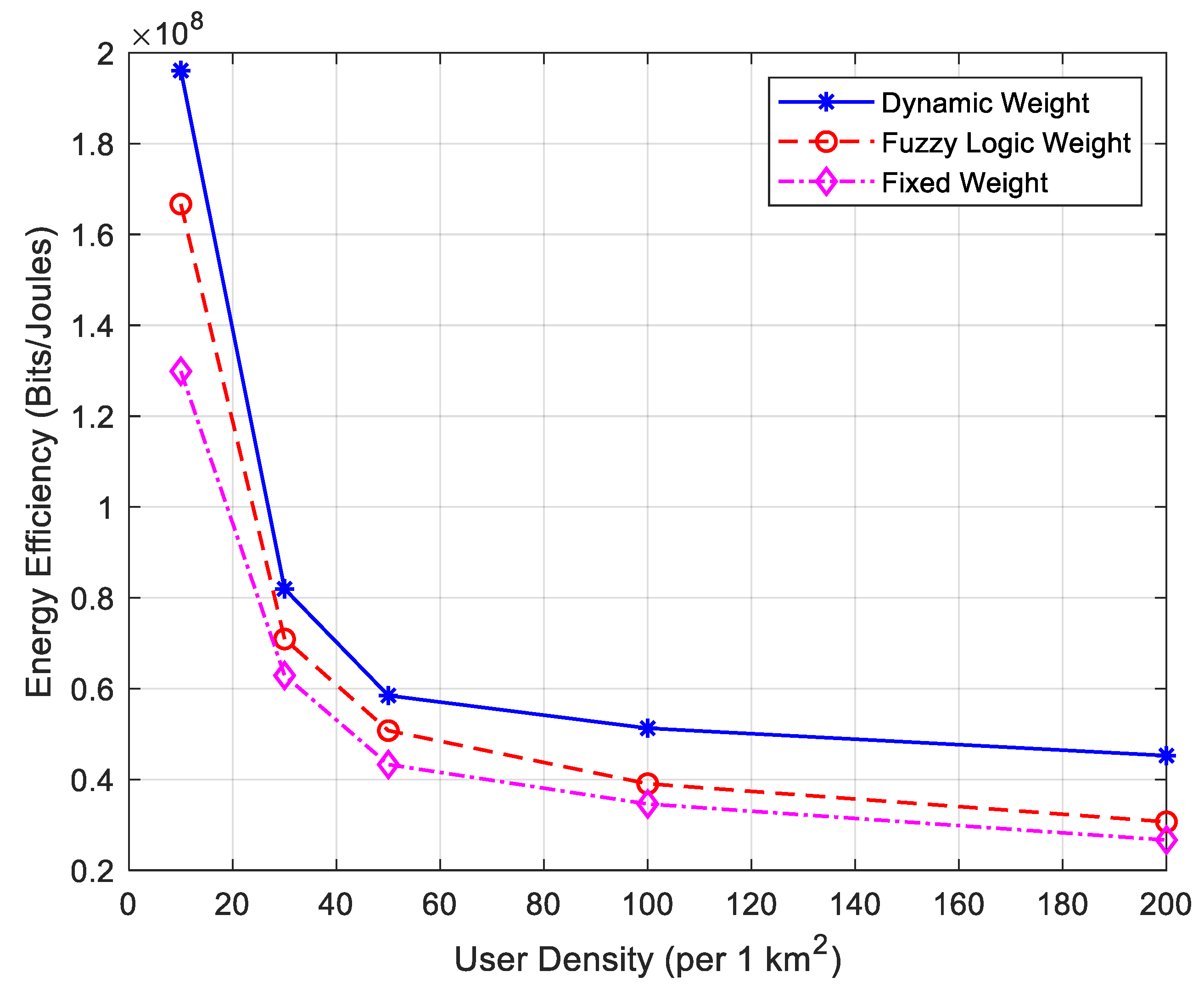

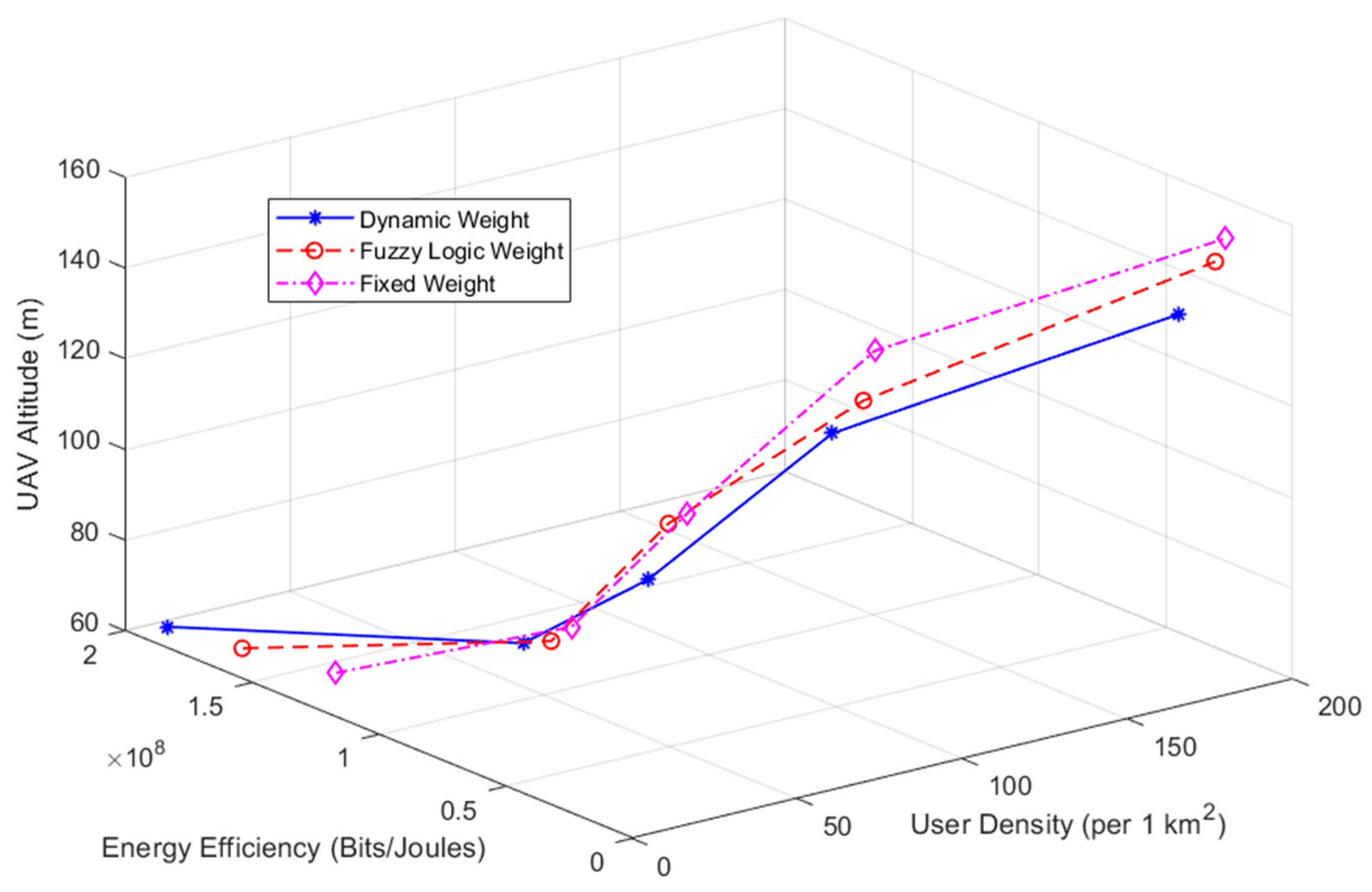

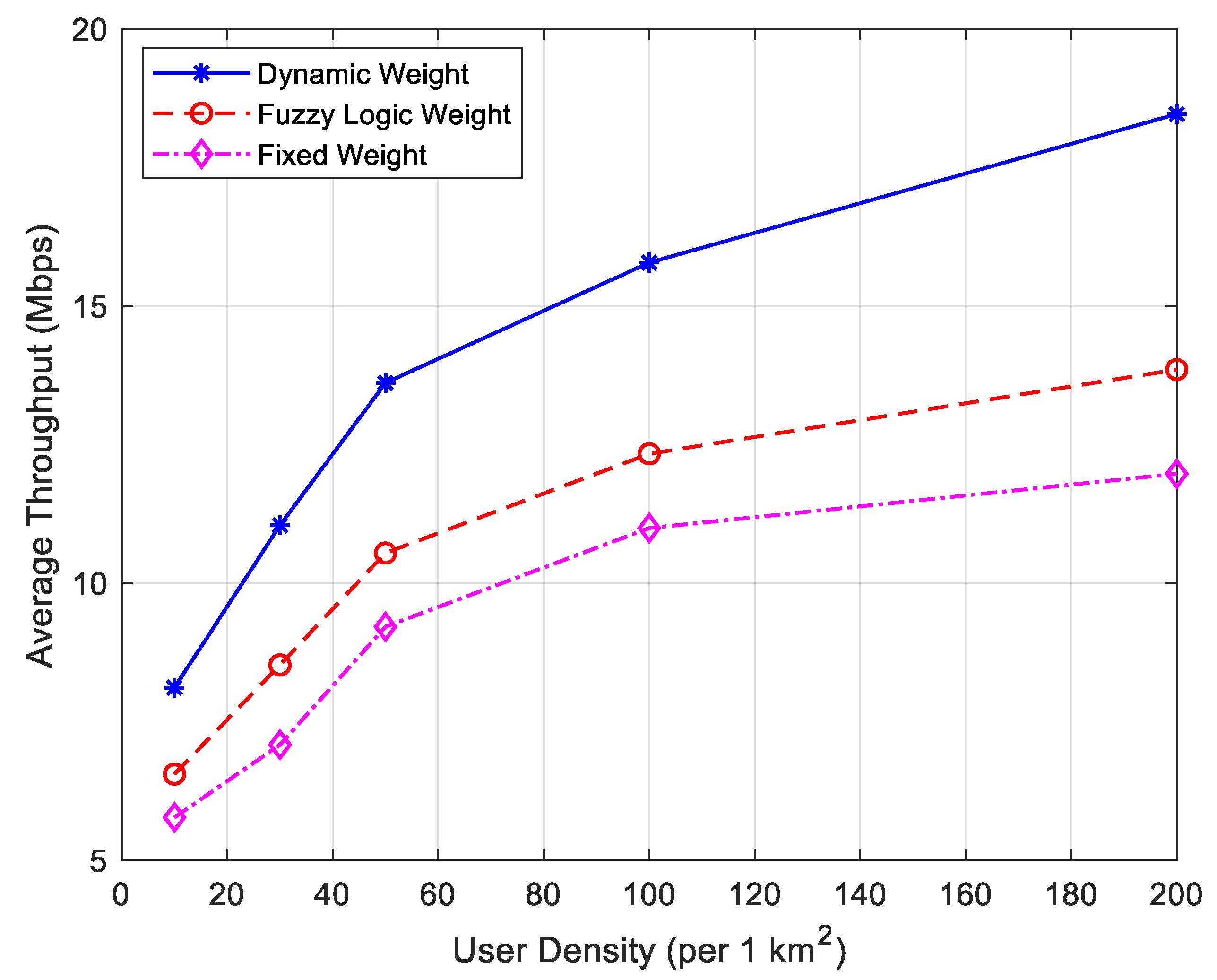

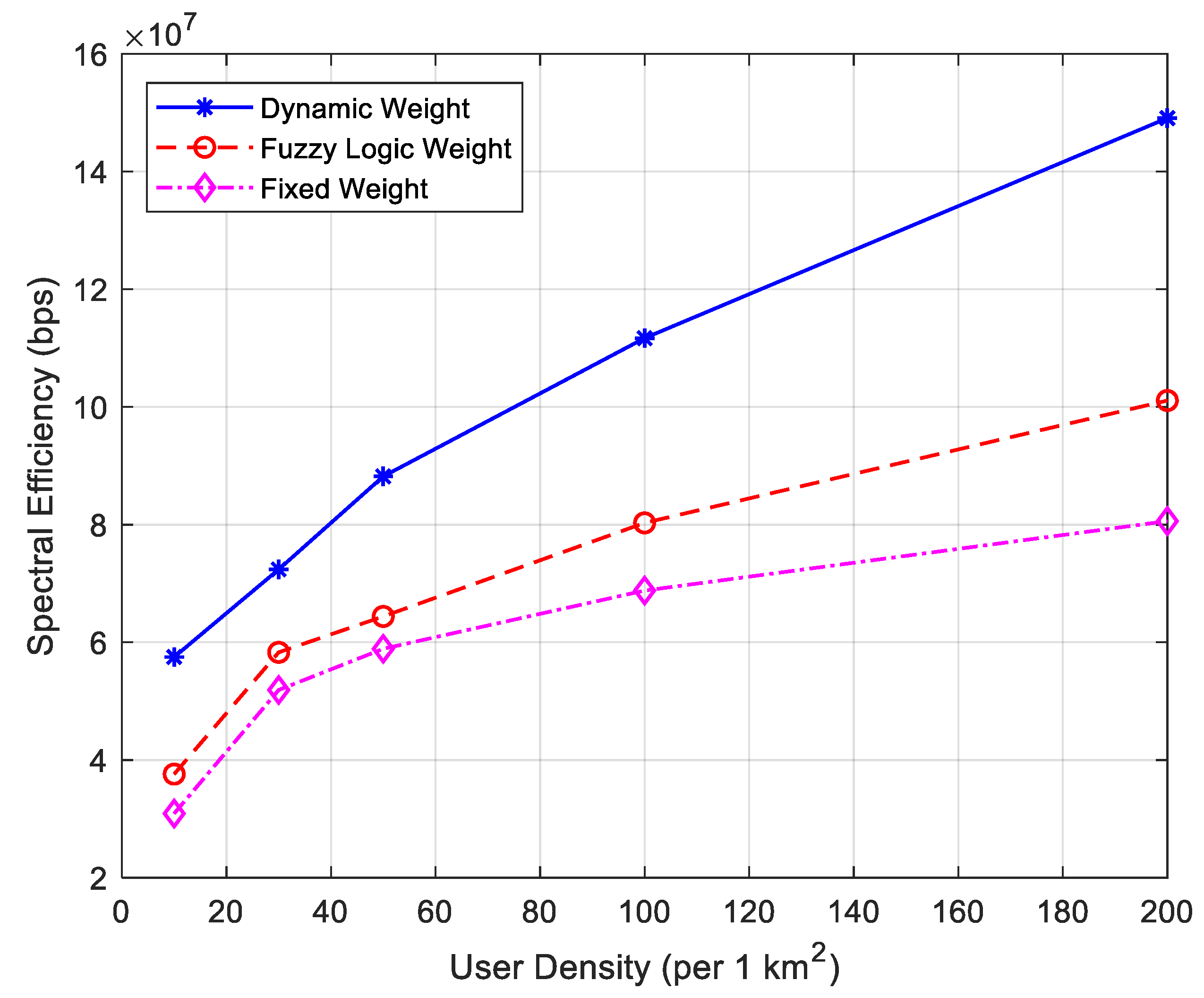

- Dynamic Weight Adaptation: The framework includes a Dynamic Weight module that adaptively balances mechanical and communication energy terms in the reward function according to instantaneous user density and channel quality. This mechanism allows the agent to reallocate decision priority in real time, improving policy adaptability under variable traffic and environmental conditions.

- (3)

- Enhanced Learning Stability Through TD3 Fusion: Integrating Twin Delayed DDPG (TD3) into the DRNN provides dual-critic evaluation, delayed policy updates, and target smoothing, reducing overestimation bias and ensuring stable convergence across continuous control spaces. This fusion enables the model to outperform baseline methods in both convergence speed and energy efficiency.

- (4)

- Cross-Domain Generalization: The proposed framework is designed to be hardware-agnostic and scalable to various UAV classes. Its structure allows for retraining across datasets from different propulsion or communication subsystems, offering a higher generalization capability than previous single-domain models.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ishu, S. Evolution of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) with Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Technology, Management & Education, Bhopal, India, 8–9 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, C.; Liang, B.; Liu, W. An efficient energy management strategy of a hybrid electric unmanned aerial vehicle considering turboshaft engine speed regulation: A deep reinforcement learning approach. Appl. Energy 2025, 390, 125837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Lei, T.; Deng, F.; Min, Z.; Yao, W.; Zhang, X. A Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Energy Management Strategy for Fuel-Cell Electric UAV. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Power Energy Systems and Applications, Singapore, 25–27 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Na, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, D.; Yao, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, K. Optimal Energy Consumption Path Planning for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Based on Improved Particle Swarm Optimization. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xiang, J.; Ye, Z.; Yan, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, P.; Xiao, M. Deep Learning-Based Energy Optimization for Edge Device in UAV-Aided Communications. Drones 2022, 6, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, P.; Guo, R. Review of energy management technologies for unmanned aerial vehicles powered by hydrogen fuel cell. Energy 2025, 323, 135751–135771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, J.; Yan, Z.; Wu, L. Energy Management of Hybrid UAV Based on Reinforcement Learning. Electronics 2021, 10, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xi, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, A.; Huang, W. Research on energy management strategies of hybrid electric quadcopter unmanned aerial vehicles based on ideal operation line of engine. J. Energy Storage 2024, 97, 112965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.S.; Elmustafa, S.A.; Maha, A.; Raed, A. Energy Efficient Path Planning Scheme for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Using Hybrid Generic Algorithm-Based Q-Learning Optimization. IEEE Access. 2023, 12, 13400–13417. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Li, H. Enhanced energy efficiency in UAV-assisted mobile edge computing through improved hybrid nature-inspired algorithm for task offloading. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2025, 243, 104290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Gu, C.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H. Heterogeneous Flight Management System (FMS) Design for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): Current Stages, Challenges, and Opportunities. Drones 2023, 7, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiad, S.; İlyas, E. Hybrid Power Systems in Multi-Rotor UAVs: A Scientific Research and Industrial Production Perspective. IEEE Access. 2023, 11, 438–458. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Y. Autonomous Driving with Deep Learning: A Survey of State-of-Art Technologies. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.06091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Kwon, S.; Park, P.; Kim, K. Active power management system for an unmanned aerial vehicle powered by solar cells, a fuel cell, and batteries. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2014, 50, 3167–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, H.; Azade, F.; Prasant, M.; Sajal, K.D. Trends and Challenges in Energy-Efficient UAV Networks. Ad Hoc Netw. 2021, 120, 102584. [Google Scholar]

- Golam, M.N.; Mohammad, A.K.; Khaled, S.F.; Golam, M.D.; Syed, A.M.D. Enhanced particle swarm optimization for UAV path planning. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology, Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 13–15 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yasir, A.; Shaik, V.A. Integration of deep learning with edge computing on progression of societal innovation in smart city infrastructure: A sustainability perspective. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100761. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Mishra, D.; Ng, D.W.K. A Comprehensive Review of Energy-Efficient Techniques for UAV-Assisted Industrial Wireless Networks. Energies 2024, 17, 4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourhan, E.; Nancy, A.; Tawfik, I. A Detailed Survey and Future Directions of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) with Potential Applications. Aerospace 2021, 8, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselt, H.; Guez, A.; Silver, D. Deep reinforcement learning with double Q-learning. In Proceedings of the 30th AAAI Conference Artificial Intelligence, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 12–17 February 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Taha, A.N.; Pekka, T. Deep reinforcement learning for energy management in networked microgrids with flexible demand. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2021, 25, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, W.; Xu, Q. Data-driven short term load forecasting with deep neural networks: Unlocking insights for sustainable energy management. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 232, 110376–110386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuneec. H520E User Manual, Version 1.4; Yuneec: Hong Kong, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Galkin, B.; Kibilda, J.; DaSilva, L.A. A stochastic model for UAV networks positioned above demand hotspots in urban environments. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 6985–6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phatcharasathianwong, S.; Kunarak, S. Hybrid artificial intelligence scheme for vertical handover in heterogeneous networks. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Graphics and Signal Processing, Tokyo, Japan, 14–16 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.H.; Yoo, C. Formula-based TCP throughput prediction with available bandwidth. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2010, 14, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, G.; Zander, J.; Sung, K.W.; Slimane, B. Fundamentals of Mobile Data Networks; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Specifications | Performance Values |

|---|---|

| Payload capacity (kg) | 2 |

| Maximum flight speed (m/s) | 13.5 |

| Maximum flight time (minute) | 30 |

| Maximum flight height (meter) | 150 |

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Bandwidth of wireless communication network (MHz) | 20 |

| Transmission power of wireless communication (watt) | 0.1 |

| Noise power of signal (watt) [27] | 10−9 |

| Path loss exponent due to obstructions in urban environments [28] | 3.5 |

| Path loss in open area (dB) | 24 |

| Maximum power consumption of UAV while hovering (watt) | 1650 |

| Maximum power consumption of UAV while moving (watt) | 2228 |

| Payload capacity of UAV (kg) | 2 |

| Flight height of UAV (meter) | 150 |

| Propulsion efficiency | 0.60–0.75 |

| Drag area (m2) | 0.05–0.20 |

| Air density (kg/m3) | 1.06–1.22 |

| Horizontal speed (m/s) | 5–15 |

| Vertical speed (m/s) | 1–3 |

| User Density (Users/km2) | Dynamic Weight (95% CI) | Fuzzy Logic Weight (95% CI) | Fixed Weight (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 3.85 ± 0.09 (3.78–3.92) | 3.21 ± 0.10 (3.12–3.30) | 2.97 ± 0.11 (2.87–3.07) |

| 50 | 3.65 ± 0.12 (3.53–3.77) | 3.02 ± 0.15 (2.86–3.18) | 2.85 ± 0.16 (2.68–3.02) |

| 100 | 3.12 ± 0.13 (2.99–3.25) | 2.45 ± 0.11 (2.36–2.54) | 2.18 ± 0.10 (2.09–2.27) |

| 150 | 2.55 ± 0.10 (2.46–2.64) | 1.96 ± 0.09 (1.88–2.04) | 1.76 ± 0.07 (1.70–1.82) |

| 200 | 2.20 ± 0.08 (2.13–2.27) | 1.47 ± 0.09 (1.39–1.55) | 1.27 ± 0.10 (1.18–1.36) |

| User Density (Users/km2) | Dynamic Weight (95% CI) | Fuzzy Logic Weight (95% CI) | Fixed Weight (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 7.2 ± 0.3 (6.9–7.5) | 6.8 ± 0.4 (6.4–7.2) | 6.6 ± 0.4 (6.2–7.0) |

| 50 | 10.3 ± 0.5 (9.8–10.8) | 9.2 ± 0.6 (8.6–9.8) | 8.5 ± 0.7 (7.8–9.2) |

| 100 | 13.8 ± 0.7 (13.1–14.5) | 11.5 ± 0.8 (10.7–12.3) | 10.6 ± 0.9 (9.7–11.5) |

| 150 | 16.2 ± 0.8 (15.4–17.0) | 13.2 ± 0.7 (12.5–13.9) | 11.9 ± 0.8 (11.1–12.7) |

| 200 | 18.5 ± 0.9 (17.6–19.4) | 13.5 ± 0.8 (12.7–14.3) | 12.0 ± 0.7 (11.3–12.7) |

| User Density (Users/km2) | Dynamic Weight (95% CI) | Fuzzy Logic Weight (95% CI) | Fixed Weight (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 2.60 ± 0.05 | 3.12 ± 0.07 | 3.38 ± 0.09 |

| 50 | 2.85 ± 0.06 | 3.50 ± 0.08 | 3.95 ± 0.09 |

| 100 | 3.10 ± 0.08 | 3.92 ± 0.09 | 4.35 ± 0.10 |

| 150 | 3.35 ± 0.07 | 4.40 ± 0.08 | 4.85 ± 0.09 |

| 200 | 3.60 ± 0.07 | 4.85 ± 0.08 | 5.20 ± 0.09 |

| Metric | Dynamic Weight | Fixed Weight | Improvement Method | Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bits/J | 2.20 | 1.27 | +73.2% | |

| Joules/bit | 3.60 | 5.20 | −30.8% | |

| Average improvement across densities | - | - | Statistical mean | 42% reduction |

| Method | Model Architecture | Energy Efficiency Improvement (%↑) | Convergence Iterations (↓) | Reward Stability (Variance ↓) | Distinctive Features/Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDPG | Feed-Forward Actor–Critic | Baseline | 100% (reference) | High (±0.35) | Standard continuous control; prone to overestimation bias. |

| Dueling DQN | Discrete-State DRL (Dueling Architecture) | +12% | 90% | Medium (±0.24) | Improves value–function separation; limited for continuous UAV dynamics. |

| PPO | Policy-Gradient | +18% | 80% | Medium–low (±0.21) | Stable convergence but slower adaptation to dynamic channel changes. |

| TD3 | Twin-Critic Actor–Critic | +22% | 70% | Low (±0.18) | Dual critic reduces bias and variance; improved robustness. |

| Proposed DRNN–TD3 | Deep Recurrent Neural Network + Twin Delayed DDPG | +27% | 60% (≈40% faster) | Lowest (±0.12) | Integrates temporal sequence learning (DRNN) into TD3 for adaptive weight control; best overall performance. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kunarak, S. Energy Management Revolution in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Using Deep Learning Approach. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010503

Kunarak S. Energy Management Revolution in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Using Deep Learning Approach. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):503. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010503

Chicago/Turabian StyleKunarak, Sunisa. 2026. "Energy Management Revolution in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Using Deep Learning Approach" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010503

APA StyleKunarak, S. (2026). Energy Management Revolution in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Using Deep Learning Approach. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010503