1. Introduction

Lasers are widely used as an important light source in many fields, including communications, fiber optic sensing, medical diagnostics, and high-precision measurement. In the field of high-precision time measurement, multiple laser sources are required to develop optical atomic clocks, which are a kind of ultra-high-precision clock based on the use of resonance frequencies in the optical atomic band as time-frequency references [

1,

2]. A strontium optical lattice clock is a typical neutral atom optical lattice clock [

3], in which there are several lasers with different wavelengths that are used for different purposes (e.g., Doppler cooling of strontium atoms, optical lattice trapping, and clock transition detection). For example, the National Time Service Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences, has developed a strontium atomic optical clock for a space mission, in which two laser sources are utilized: a primary cooling light with a 461 nm laser and a secondary cooling light with a 689 nm laser [

4,

5]. In order to ensure the coverage of the strontium atomic energy level transition resonance frequency, it is essential to keep the wavelengths of these laser sources stable while allowing them to be tunable within a small range. Consequently, a Fizeau wavemeter is incorporated into the optical clock system to ascertain the actual wavelength, which serves as a closed-loop control parameter for tuning the lasers [

6].

In addition to the laser wavelength, the laser longitudinal mode also plays a significant role in the strontium atomic optical clock. Operation in a single longitudinal mode (SLM) is essential, as it ensures a narrow spectral linewidth and high temporal coherence of the output light. These characteristics are indispensable for the preceding laser cooling stages. Specifically, for efficient Doppler cooling, the laser linewidth must be narrower than the natural linewidth of the atomic transition. A laser operating in multiple longitudinal mode (MLM) possesses a broadened spectrum, which diminishes the precise velocity selectivity of the laser–atom interaction. This degradation directly compromises cooling efficiency and limits the achievable atom number in the optical lattice, ultimately affecting the stability of the clock. Therefore, accurate and efficient identification of the laser’s longitudinal mode state (SLM vs. MLM) is vital for optimizing and maintaining the clock’s overall performance.

A common method to assess the laser longitudinal mode is based on scanning interferometers [

7], or beat-frequency detection, which requires a spectrometer to detect the potential differential frequency angle produced by lasers of multiple frequencies [

8]. However, since such methods necessitate high-performance optical analyzers and relevant electronic equipment, it is not conducive to the development of a lightweight and portable optical clock system suitable for a space mission. If an existing instrument in the optical clock system, such as a wavemeter, could be utilized to monitor the laser mode, the system would be more compact and streamlined.

Chen et al. studied the tuning characteristics of lasers using a wavemeter [

9], but the wavemeter only served as an auxiliary tool and the laser mode still needed to be identified through scanning interferometry and photodetection. Zheng et al. judged the laser mode based on whether the wavelength value changed linearly with temperature [

10]. This method is suitable for scenarios with fixed laser wavelength, but has limited effects in applications that require laser wavelength tuning.

In this work, rather than examining the changes in the laser wavelength values, we directly analyze the laser interference fringe data measured by the Fizeau wavemeter. By leveraging the powerful pattern identification and feature extraction capabilities of machine learning algorithms, we have realized accurate and efficient monitoring of the laser longitudinal mode in a strontium atomic optical clock. This work establishes a new methodology for building compact laser monitoring systems and reveals possibilities for intelligent photonics instrumentation with built-in diagnostic capabilities. This innovative methodology is particularly suitable for applications with strict size constraints, such as space instrumentation, integrated photonics, and in situ laser diagnostics, where traditional bulky spectrum analyzers cannot be deployed.

The following text is arranged as follows:

Section 2 introduces the experimental methods and dataset processing schemes;

Section 3 exhibits the results of the machine learning models and offers some discussion; and

Section 4 provides a conclusion.

2. Methods

2.1. Fizeau Wavemeter

The Fizeau wavemeter adopted in our optical clock system is a WS series product from HighFinesse Laser and Electronic Systems GmbH, Tübingen, Germany, which operates based on the Fizeau interferometric principle [

11]. A schematic diagram of the optical system of a typical Fizeau interferometer is illustrated in

Figure 1a. The interferometer consists of two slightly angled reflecting surfaces, such as glass wedges, with angles of a few arcseconds. In this setup, the front surface of the wedge is partially reflective, while the back surface is fully reflective. Alternatively, separate reflectors can be used. When the two reflected beams overlap by a small angle they produce interference fringes, as shown in

Figure 1b. These interference fringes can be captured by a digital camera and the resulting data are processed by a microprocessor. Then, the wavelength of the light can be calculated based on the distance between adjacent bright or dark fringes (i.e., the fringe period), the parameters of the interferometer (such as the distance between the mirrors and the refractive index), and the number of interference fringes.

As mentioned above, the Fizeau wavemeter is an “intrinsic” instrument of the optical clock system for the measurement of laser wavelength, but, herein, we exploit it to play an additional role, i.e., as the indicator of the laser longitudinal mode. This novel strategy proposed in the current work allows us to acquire laser mode information without introducing additional measuring instruments into the optical clock system.

2.2. Longitudinal Modes of the Laser

Longitudinal modes refer to the stable standing wave patterns formed along the “longitudinal” direction, i.e., the direction of the laser resonator axis [

12]. The laser resonator has several resonance conditions, each supporting different amplitude and phase distributions. When multiple light waves inside the resonator satisfy distinct phase-matching conditions, multiple standing wave patterns can coexist within the same cavity. The side-mode suppression ratio (SMSR) is a key parameter that characterizes the spectral purity of a laser. It quantifies the power ratio between the main mode and the strongest side mode in the laser’s emission spectrum. Generally speaking, the laser can be regarded as operating in SLM if the power of the main mode is significantly stronger than the power of the strongest side mode and the laser is considered as operating in MLM if the opposite is the case. The SMSR threshold for discriminating between SLM and MLM in this study can be found in

Section 2.4. A laser operating in SLM instead of MLM can exhibit narrow spectral linewidth, high frequency stability, and excellent coherence, which are important merits for high-precision measurement applications.

In our optical clock system, external-cavity feedback diode lasers manufactured by TOPTICA are employed as the light source. While TOPTICA lasers achieve a large mode-hop-free tuning range by simultaneously adjusting the grating angle, external cavity length, and semiconductor laser current, we have observed that multiple mode competition may still occur during frequency adjustment. In such cases, even if the wavemeter indicates that the laser wavelength is accurate, the cooling efficiency of strontium atoms may still be unsatisfactory due to an insufficient SMSR, a broadened spectral linewidth, or an inadequate power concentration. Therefore, in addition to enhancing the drive current stability and upgrading the temperature control, it is important to employ accurate and efficient identification of the laser longitudinal mode for the increase of atom cooling efficiency.

2.3. Machine Learning Models

Machine learning is a major artificial intelligence methodology aiming to learn the mapping relationship between data features and specific attributes. Machine learning models, after proper training based on certain datasets, are expected to accomplish classification and/or regression tasks with minimal manual intervention [

13]. Compared to traditional manual and classical statistical methods, machine learning methods demonstrate stronger competence in feature extraction and learning, better adaptability to new data and new tasks, and superior efficiency in processing high-dimensional and large-scale data. In this study, we have designed two machine learning models for the classification of laser longitudinal modes, based on support vector machine (SVM) and convolutional neural network (CNN) algorithms, respectively.

SVM is a widely used machine learning algorithm for pattern recognition and classification tasks [

14]. The fundamental principle of an SVM algorithm is to map data into a high-dimensional feature space and identify a hyperplane that separates data from different categories, while maximizing the margin between the data points and the hyperplane. This approach produces a maximum-margin classifier with a strong generalization capability and robustness.

An artificial neural network (ANN) is a prominent paradigm of machine learning, suitable for solving problems that are complex, ill-defined, highly nonlinear, formed of many and different variables, and/or stochastic. As a main approach in the ANN methodology, CNN is an important representative of deep learning, which is a cutting-edge branch of machine learning. CNN is a kind of multilayer perceptron feedforward network with an error back-propagation learning scheme, but it distinguishes itself from regular networks due to its peculiar operations, i.e., so-called “convolution” and “pooling”. The CNN algorithm is most extensively applied in processing two-dimensional data like images [

15], while it has also demonstrated extraordinary performance in analyzing one-dimensional data like spectra [

16].

In this study, the two machine learning models are constructed by libraries in Python 3.6. The SVM model is built on the basis of the Scikit-learn library [

17], with a linear kernel function adopted. The input data is preprocessed by the Standardscaler function to ensure accurate and reliable classification.

The CNN model is constructed based on the Sequential Model in the Keras framework [

18], one of the most widely used frameworks for deep learning. In total, there are eleven layers in the CNN model, including one input layer, one batch normalization layer, two convolutional layers, two pooling layers, one flatten layer, one dropout layer, two dense layers, and one output layer, as shown in

Figure 2. The ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) function is adopted as the activation function of each convolutional layer and the first dense layer [

19]. In front of the dense layers, one dropout layer is inserted to prevent overfitting by randomly inactivating a certain ratio of the network connections [

20]. The final dense layer of the CNN uses the Softmax function as the activation function and outputs the predicted result in the form of a probability distribution [

21]. The designed CNN model architecture is illustrated in

Figure 2.

2.4. Dataset Acquisition and Processing

As mentioned above, the dataset used in the machine learning models is the interference fringe data acquired from the HighFinesse Fizeau wavemeter in the optical clock. The wavemeter is equipped with RS232 and Ethernet interfaces for communication with a computer and with graphical interface software for online wavelength monitoring, parameter adjustment, and data storage. Additionally, HighFinesse provides a software development kit (SDK) that supports secondary development, allowing us to integrate our own software applications into the wavemeter.

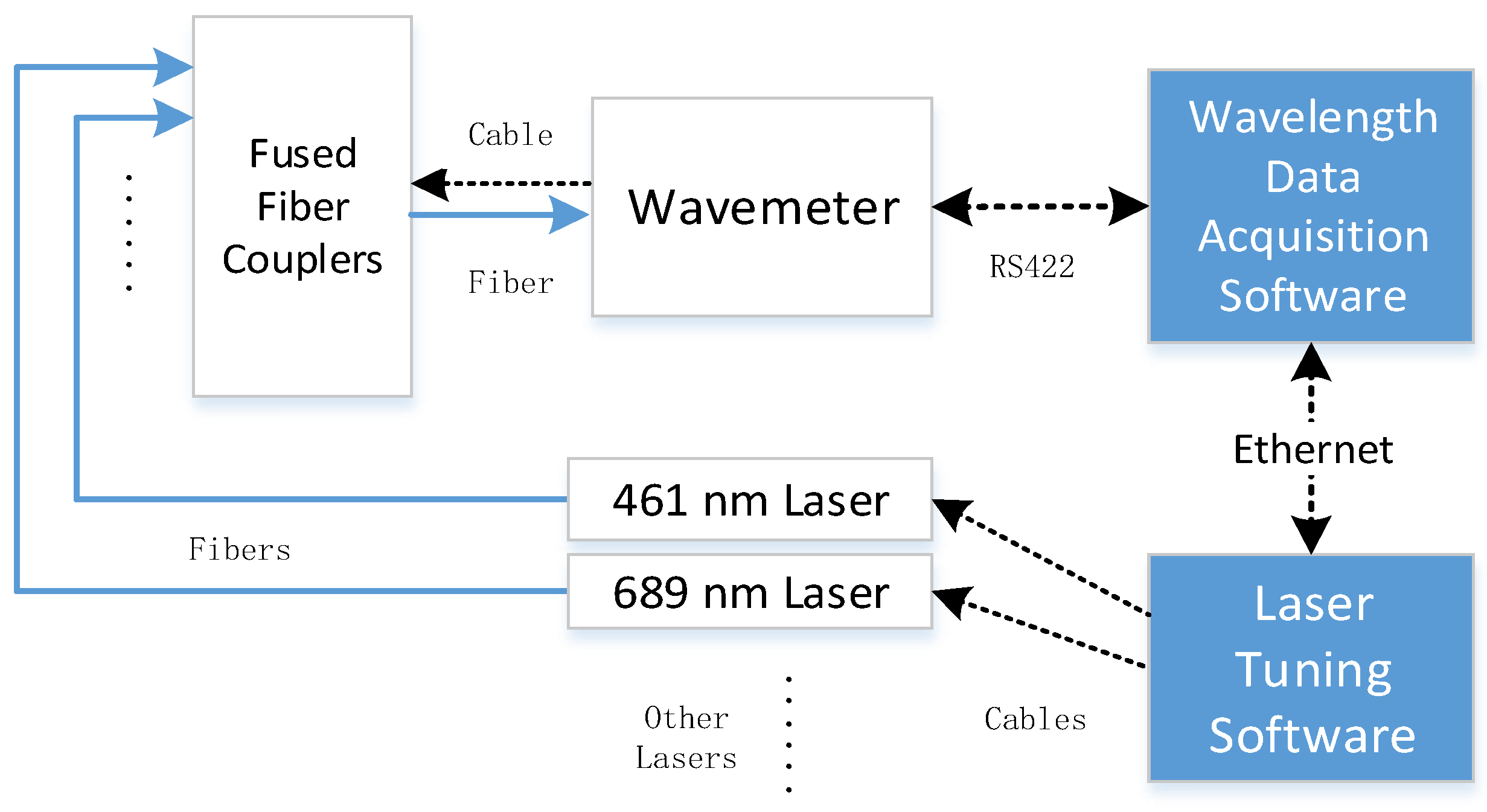

In the optical clock system, a suite of dedicated software was developed to enable automated operation via a computer, facilitating precise timing control for deceleration cooling and atom trapping. The wavelength measurement function is integrated into the control software, enabling online automatic wavelength measurement by utilizing the wavemeter’s programming interface. The layout of the laser wavelength measurement unit is shown in

Figure 3. Multiple lasers are connected to the wavemeter through a multi-channel fiber combiner, and the software controls the channel switching of the combiner. This setup enables a single wavemeter to measure multiple laser wavelengths conveniently. In this study, two laser sources were used: one was a 461 nm laser and the other was a 689 nm laser.

The HighFinesse WS series wavemeter optically generates a two-dimensional interference fringe pattern. However, the instrument internally employs a linear CCD array to detect this pattern. The CCD array outputs the intensity profile as a function of pixel position, which is inherently a one-dimensional data array. According to the wavemeter’s software manual [

22], we accessed this primary measurement channel via a dedicated application programming interface (API). Thus, the one-dimensional fringe intensity profile serves as a suitable direct input for our analysis, enabling the identification of the laser’s longitudinal mode state through either manual inspection or machine learning models.

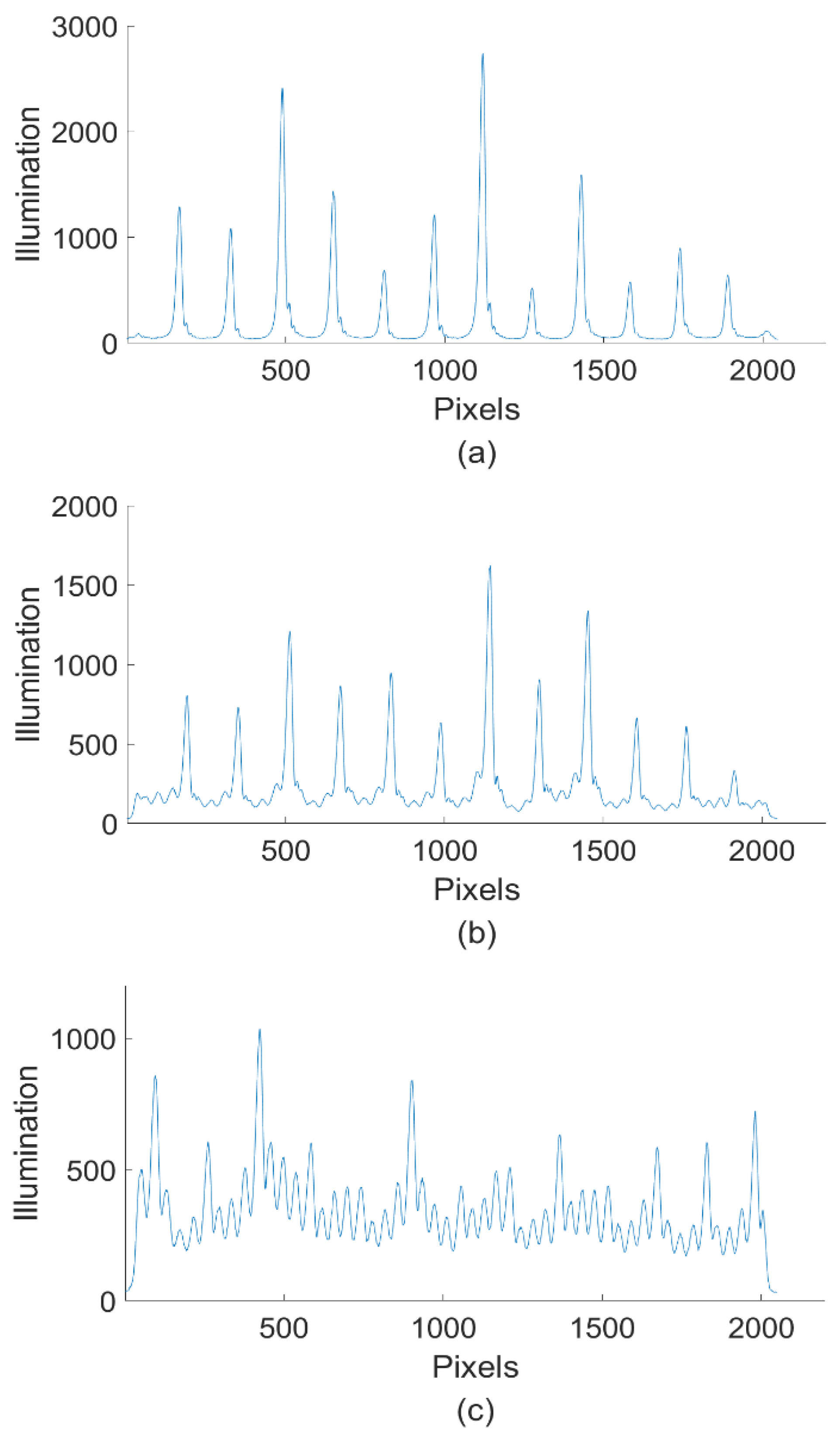

When the laser operates in SLM, the interference pattern displays distinct, alternating bright and dark fringes with high parallelism and the contrast between the brightness peaks and dark troughs is significant. A typical interference fringe pattern representing SLM features is demonstrated in

Figure 4a. On the contrary, when the laser operates in MLM and multi-mode competition occurs, the interference fringe pattern loses parallelism or becomes indistinct, with a noticeable reduction in contrast between the brightness peaks and dark troughs. A typical fringe pattern indicating slight multi-mode competition is shown in

Figure 4b and that indicating serious multi-mode competition is exhibited in

Figure 4c.

Based on the setup shown in

Figure 3, we have collected the laser interference fringe data yielded from the two laser sources (461 nm and 689 nm). The total interference fringe dataset contains 589 samples and is divided into two sets without intersection, i.e., one training set (309 samples) and one testing set (280 samples). Some example data of the interference fringes from the two laser sources are demonstrated in

Figure 5.

Either the training set or the testing set contains the fringe data samples from both laser sources. The sample number information for the two sets is displayed in

Table 1. Note that sample mixing of the wavelength dimension has been implemented. Taking the 461 nm laser data as an example, in the training set, there are 16 fringe data samples yielded from the 689 nm laser; in the testing set, there are 14 fringe data samples yielded from the 689 nm laser. Such sample mixing is designed to better examine the discrimination capability of the machine learning models.

According to the dataset design, each fringe data sample may indicate one of the following three states of laser mode: (i) the laser operates in SLM with matched wavelength; (ii) the laser operates in MLM with matched wavelength; and (iii) the condition of unmatched wavelength (UMWL) occurs. For the machine learning models, laser mode identification is actually a binary classification task, with the two labels being SLM and non-SLM (including MLM and UMWL). In this work, SLM is regarded as “positive”, while non-SLM is regarded as “negative”. The SLM/non-SLM real labels were determined by the SMSR values according to the measurements of an optical spectrum analyzer (herein a scanning Fabry–Perot interferometer [

23]). The engineering definition of SMSR is

. In this work, the SLM label would be offered if the SMSR value is at least 20 dB, while the non-SLM label corresponds to the opposite case.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results

In this section, the results of laser mode identification are exhibited and the classification performance of the SVM model and that of the CNN model are compared. The classification performance is evaluated based on the following four metrics [

24]:

- (i)

accuracy, i.e., the number of correctly classified samples divided by the total number of samples, ;

- (ii)

precision, i.e., the number of correctly classified positive samples divided by the total number of samples classified as positive, ;

- (iii)

recall, i.e., the number of correctly classified positive samples divided by the total number of actual positive samples, ;

- (iv)

F1 score, i.e., the harmonic mean of the precision and the recall, .

In these equations, is the number of true positive cases, is the number of false positive cases, is the number of true negative cases, and is the number of false negative cases. For each of the four metrics, a higher value indicates a better classification performance, with the maximum value being 1.

3.1.1. The SVM Model with Normal Fringe Data

As described before, each interference fringe data sample is normally treated as a one-dimensional vector. Using the samples and labels in the training set, we have trained two SVM classification models, corresponding to the two laser sources. After training, the two SVM models were used to classify the fringe data samples in the testing set with corresponding wavelengths.

The SVM models’ classification performance in both training and testing, evaluated by the above four metrics, can be found in

Table 2. It is apparent that the models’ training is effective, with the classification results for both laser sources being completely correct. For testing, the trained SVM models achieved high performance, with the precision values still being 1 and the other three metrics being a bit lower than 1. It is noteworthy that each data sample herein is a 2048 × 1 vector with a 2048 × 2 byte size.

3.1.2. The SVM Model with Frequency Domain Data

The above method that treats the interference fringe data as a 2048 × 1 vector requires a relatively high computational cost due to the large size of each sample. Hence, we have tried to convert the original data samples into frequency domain samples, which are expected to provide clearer insights into the data features [

25]. We have performed fast Fourier transform (FFT) on every fringe data sample. In

Figure 6, we present three typical amplitude spectra acquired based on FFT operations, corresponding to the three interference fringe data samples shown in

Figure 4.

In the spatial frequency domain, the SLM pattern exhibits a spectrum with highly concentrated energy. This is evidenced by a dominant, high-amplitude peak at the fundamental spatial frequency (

Figure 6a), which is determined by the laser’s wavelength and the interferometer resolution. In contrast, the MLM pattern shows apparently lower peak amplitudes, along with more irregular noise appearances (

Figure 6c).

After analyzing the above characteristics, we select the following five parameters to characterize each amplitude spectrum: (i) Amp_max, the maximum amplitude value across the entire spectrum; (ii) Freq_max, the spatial frequency corresponding to Amp_max; (iii) FWHM, the full width at half maximum of the Freq_max; (iv) Amp_tot, the sum of the absolute values of the amplitudes across the entire spectrum; and (v) Inten_r, the ratio between the square of the Amp_max and the sum of the squares of the remaining amplitudes (i.e., the sum of the square of the amplitudes minus the square of Amp_max). Hence, each normal fringe data sample, after being converted into a frequency domain sample, can finally be characterized by a 5 × 1 vector with a 5 × 4 byte size, which is employed as the input for the SVM model training and testing herein.

The classification performance of the SVM model based on the frequency domain samples is displayed in

Table 3. The results reveal that the extracted frequency domain features can outperform the normal fringe data samples, achieving almost perfect accuracy on the testing set.

3.1.3. The CNN Model

For the CNN model, the original interference fringe data samples (2048 × 1 vector) are employed as the input for the classification. The training is conducted based on the Adam optimizer, and a cross-entropy loss function is selected as the objective function to guide the optimization. Three important hyperparameters, i.e., the initial learning rate, the weight decay, and the dropout rate, have been carefully tuned and finally set as 0.001, 10−5, and 0.4, respectively.

The classification performance of the CNN model based on the normal fringe data samples is exhibited in

Table 4. Using the normal fringe data, the CNN model can achieve perfect accuracy on both the training set and the testing set, surpassing the SVM model described in

Section 3.1.1 and equaling that of the SVM model described in

Section 3.1.2. These results indicate that the CNN algorithm has a stronger ability to extract and learn meaningful features among large-scale data. Moreover, the CNN method is able to achieve perfect accuracy without the necessity of domain transformation and manual feature engineering, showing higher convenience compared to the SVM method in

Section 3.1.2.

3.2. Discussion

The longitudinal modes of two lasers at different wavelengths have been correctly identified, demonstrating that machine learning algorithms can effectively learn the characteristics of different types of laser interference fringe data. This method can also be extended to process laser sources at other wavelengths.

The CNN model exhibits the most powerful classification performance, achieving perfect accuracy directly on normal fringe data. This result indicates that deep learning algorithms like CNN are able to self-learn hierarchical feature representations from the input data without the necessity of manual feature engineering, hence, showing superiority over regular machine learning algorithms like SVM, regarding their convenience. Meanwhile, it should be noted that the design of the CNN model and its hyperparameter tuning may require considerable time costs and manual expertise and the operation process needs abundant computational resources. Moreover, the size and diversity of our dataset may limit the generalization ability of the CNN model. We will employ larger and more diverse datasets (e.g., by adding more wavelengths and adding more environmental variation factors) in future work.

The SVM model can also acquire nearly perfect accuracy, but the normal interference fringe data needs to be thoroughly preprocessed, including space-to-frequency domain transformation and manual feature extraction. Although the SVM method cannot realize the end-to-end effect like the CNN method, it needs fewer computational resources to deal with the preprocessed data. For the current dataset, the training time of the SVM model (in the case of frequency domain) is only about 1/50 of that of the CNN model. This speed advantage of SVM is expected to become even more pronounced with larger datasets. Therefore, for those tasks in which computational resources are limited and feature-engineering expertise is available, the SVM method might be preferred despite its slightly lower accuracy.

By integrating the functions of fringe data collection, frequency domain feature engineering, machine learning model training, and classification into the closed-loop control software, we can now employ the wavemeter to realize online analysis of the laser longitudinal mode, in addition to the original function of laser wavelength monitoring. The methodology proposed in this work has already been practically implemented in the development of a lightweight and compact optical clock system for a space mission in China. In the future, this methodology is expected to be applied to other high-precision laser systems where efficient identification of the laser longitudinal mode is necessary and researchers can choose appropriate algorithms according to the accuracy requirements and computational resources.

4. Conclusions

This study proposes a new method for efficient identification of laser mode state, based on laser interference fringe data and machine learning algorithms. Using a dataset comprising 589 interference fringe samples from two different laser wavelengths, we have constructed three classification models based on SVM and CNN algorithms to discriminate between SLM and non-SLM patterns. All three models can achieve perfect accuracy on the training set, while the CNN model can even achieve flawless accuracy on the testing set. Although SVM models do not achieve 100% accuracy on the testing set, they can still reach over 96% accuracy, while requiring a less complex model structure and fewer computational resources. In the future, this innovative method may be generalized to space-task applications like space-borne gravitational-wave detection and coherent inter-satellite laser communications. In these scenarios, the rigorous and autonomous monitoring of the laser longitudinal mode status is critical. For gravitational-wave observatories, it ensures the phase stability and long coherence length required for picometer-level interferometric measurements. For inter-satellite laser communications, it guarantees the phase coherence necessary for high-sensitivity homodyne detection. This method may also be adopted in laser spectroscopy technology for deep space exploration, such as laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS)—a laser–plasma-based technique that has already demonstrated outstanding power in Mars exploration missions [

26]. Although in the past Mars missions conventional single-pulse LIBS was employed, one may expect the utilization of upgraded LIBS techniques in the future, such as resonance-enhanced LIBS (RE-LIBS). The most common instance of RE-LIBS is in a combination of LIBS and laser-induced fluorescence (LIF), requiring a conventional LIBS pulse and an additional excitation laser pulse with a specific wavelength [

27]. The LIBS-LIF technique can selectively excite specific atoms within the plasma and dramatically boost the detection sensitivity of the selected elements, which could be pivotal in the search for potential biosignatures or trace key elements on Mars. In the LIBS-LIF scheme, the second laser pulse should have a very narrow linewidth to ensure accurate selective excitation. Therefore, real-time monitoring of laser operation mode (SLM or other) is important for such space-task applications. Our research provides a viable and intelligent framework for in-orbit laser mode diagnostics based on interference signals. Despite the fact that the payloads of future missions may not necessarily include a wavemeter to directly collect interference fringe data, the underlying methodology in this work—leveraging characteristic interference patterns for machine learning-based mode diagnosis—is inherently transferable and this methodology is expected to enhance the performance and efficiency of future space missions that require high-precision measurements and lightweight payloads.