Advanced 3D Modeling and Bioprinting of Human Anatomical Structures: A Novel Approach for Medical Education Enhancement

Abstract

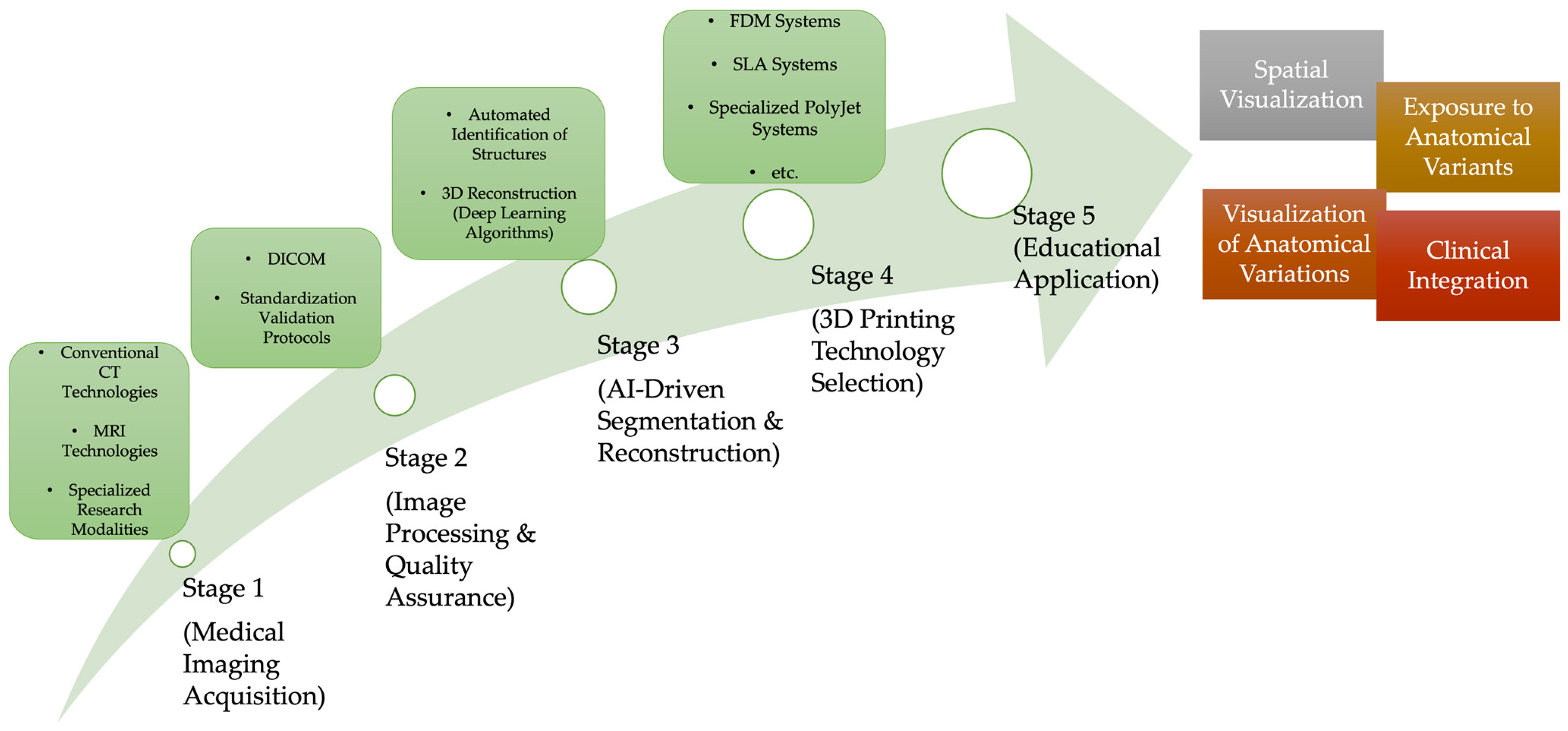

1. Introduction

2. Advanced Medical Imaging Technologies for 3D Anatomical Model Generation

2.1. Computed Tomography Imaging: Transition from Conventional to Spectral Technologies

2.2. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

2.3. Medical Imaging Workflow and Quality Assurance

3. Artificial Intelligence-Based Reconstruction Technologies

3.1. Deep Learning Neural Networks, AI Architecture

3.2. Attention Mechanisms and Uncertainty Quantification

3.3. Clinical Validation and Anatomical Variability Detection

3.4. Specialized Capabilities Include Non-Contrast CT and Artifact Reduction

3.5. Quality Assurance and Automated Validation Mechanism

3.6. Clinical Results and Educational Impact

3.7. Comparative Analysis: AI-Based vs. Traditional Reconstruction Methods

4. Advanced Bioprinting Manufacturing Technology

4.1. Multi-Material Bioprinting & Comparative Technology Selection Framework

4.2. Cell-Laden Bioprinting and Its Educational Significance Beyond Anatomical Replication

5. Educational Application and Learning Outcomes

5.1. Normal Anatomical Education and Spatial Visualization Improvement

5.2. Pathological and Variant Anatomy Visualization

5.3. Clinical Integration and Radiological Interpretation Skills

5.4. 4D Printing and Dynamic Anatomical Modeling: Emerging Frontiers in Educational Innovation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Computed tomography |

| MDCT | Multidetector computed tomography |

| kVp | kilovolt peak |

| UHRCT | Ultra-high-resolution CT |

| micro-CT | Microfocus CT |

| nano-CT | Nanocomputed tomography |

| DECT | Dual-energy computed tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| CE-MRA | Contrast-enhanced MR angiography |

| UTE | Ultra-short echo time |

| ZTE | Zero echo time |

| DICOM | Digital imaging and communications in medicine |

| FDM | Fused deposition modeling |

| SLA | Stereolithography |

| DLP | Digital light processing |

| SLS | Selective laser sintering |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| CNN | Convolutional neural networks |

| 3D U-Net | Three-dimensional U-Net architecture |

| DeepMedic | Deep medical imaging |

| V-Net | Volumetric neural network |

| SMD | Standardized mean difference |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| vs | Versus |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| HAP | Hydroxyapatite |

| Ca-P | Calcium phosphate |

| PCL | Polycaprolactone |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| PLGA | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| PLA | Polylactic acid |

| PETG | Polyethylene terephthalate glycol |

| TPU | Thermoplastic polyurethane |

| ABS | Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene |

| HU | Hounsfield unit |

| DOI | Digital Object Identifier |

| AR | Augmented reality |

| VR | Virtual reality |

References

- Ghosh, S.K. Cadaveric Dissection as an Educational Tool for Anatomical Sciences in the 21st Century. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2017, 10, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valcke, J.; Csík, L.B.; Säflund, Z.; Nagy, A.; Eltayb, A. Anatomy Education at Central Europe Medical Schools: A Qualitative Analysis of Educators’ Pedagogical Knowledge, Methods, Practices, and Challenges. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ail, G.; Freer, F.; Chan, C.S.; Jones, M.; Broad, J.; Canale, G.P.; Elston, P.; Leeney, J.; Vickerton, P. A Comparison of Virtual Reality Anatomy Models to Prosections in Station-Based Anatomy Teaching. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2024, 17, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtu, A.T.; Manjatika, A.T. Challenges in Sourcing Bodies for Anatomy Education and Research in Ethiopia: Pre and Post COVID-19 Scenarios. Ann. Anat.-Anat. Anz. 2024, 254, 152234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, J.; Cai, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, F.; Xiong, K. A Shortage of Cadavers: The Predicament of Regional Anatomy Education in Mainland China. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2018, 11, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga-Garza, A.; Reyes-Hernández, C.G.; Zarate-Garza, P.P.; Esparza-Hernández, C.N.; Gutierrez-de la O, J.; de la Fuente-Villarreal, D.; Elizondo-Omaña, R.E.; Guzman-Lopez, S. Willingness toward Organ and Body Donation among Anatomy Professors and Students in Mexico. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2017, 10, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürses, İ.A.; Coşkun, O.; Öztürk, A. Current Status of Cadaver Sources in Turkey and a Wake-up Call for Turkish Anatomists. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2018, 11, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMenamin, P.G.; Costello, L.F.; Quayle, M.R.; Bertram, J.F.; Kaka, A.; Tefuarani, N.; Adams, J.W. Challenges of Access to Cadavers in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC) for Undergraduate Medical Teaching: A Review and Potential Solutions in the Form of 3D Printed Replicas. 3D Print. Med. 2025, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Caro, R.; Boscolo-Berto, R.; Artico, M.; Bertelli, E.; Cannas, M.; Cappello, F.; Carpino, G.; Castorina, S.; Cataldi, A.; Cavaletti, G.A.; et al. The Italian Law on Body Donation: A Position Paper of the Italian College of Anatomists. Ann. Anat.-Anat. Anz. 2021, 238, 151761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, S.; Hamba, N.; Kebede, W.; Bajiro, M.; Debela, L.; Nigatu, T.A.; Gerbi, A. Assessment of Ethical Compliance of Handling and Usage of the Human Body in Anatomical Facilities of Ethiopian Medical Schools. Pragmatic Obs. Res. 2021, 12, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habicht, J.L.; Kiessling, C.; Winkelmann, A. Bodies for Anatomy Education in Medical Schools: An Overview of the Sources of Cadavers Worldwide. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2018, 93, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Xiong, H.; Wen, Y.; Li, F.; Hu, D. Global Trends in Cadaver Donation and Medical Education Research: Bibliometric Analysis Based on VOSviewer and CiteSpace. JMIR Med. Educ. 2025, 11, e71935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papa, V.; Vaccarezza, M. Teaching Anatomy in the XXI Century: New Aspects and Pitfalls. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 310348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.J.; Chapman, J.A. A Slide into Obscurity? The Current State of Histology Education in Australian and Aotearoa New Zealand Medical Curricula in 2022–2023. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2024, 17, 1694–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzino, S.; Luca, T.; Castorina, M.; Puleo, S.; Castorina, S. Transforming Medical Education Through Intelligent Tools: A Bibliometric Exploration of Digital Anatomy Teaching. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghera, R.; Kotecha, S. The Educational Value in the Development and Printing of 3D Medical Models—A Medical Student’s Perspective. Med. Sci. Educ. 2022, 32, 1563–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, R.; Likus, W.; Hudecki, A.; Syguła, M.; Różycka-Nechoritis, A.; Nechoritis, K. What Would You like to Print? Students’ Opinions on the Use of 3D Printing Technology in Medicine. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujol, S.; Baldwin, M.; Nassiri, J.; Kikinis, R.; Shaffer, K. Using 3D Modeling Techniques to Enhance Teaching of Difficult Anatomical Concepts. Acad. Radiol. 2016, 23, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, D.; Thompson, M.; Rosen, A.; Zuniga, J. Using 3D Printing to Improve Student Education of Complex Anatomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med. Sci. Educ. 2022, 32, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.H.; Loo, Z.Y.; Goldie, S.J.; Adams, J.W.; McMenamin, P.G. Use of 3D Printed Models in Medical Education: A Randomized Control Trial Comparing 3D Prints versus Cadaveric Materials for Learning External Cardiac Anatomy. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2016, 9, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafošnik, U.; Cerovečki, V.; Stojnić, N.; Belec, A.P.; Klemenc-Ketiš, Z. Developing a Competency Framework for Training with Simulations in Healthcare: A Qualitative Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Jiang, H.; Bai, S.; Wang, T.; Yang, D.; Hou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yi, S. Meta-Analyzing the Efficacy of 3D Printed Models in Anatomy Education. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1117555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backhouse, S.; Taylor, D.; Armitage, J.A. Is This Mine to Keep? Three-Dimensional Printing Enables Active, Personalized Learning in Anatomy. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2019, 12, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, N.; Kelly, K.; Husaric, M.; Wospil, R.; Fleischmann, M.; Johnston, S.; Harkin, K. The Impact of Three-Dimensional Printed Anatomical Models on First-Year Student Engagement in a Block Mode Delivery. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2020, 13, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, G.; Wang, T.; Fu, H.; Liu, D.; Deng, L.; Zheng, X.; Li, L.; Liao, J. The Role of Three-Dimensional Printing Models in Medical Education: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freiser, M.E.; Ghodadra, A.; Hirsch, B.E. Operable, Low-Cost, High-Resolution, Patient-Specific 3D Printed Temporal Bones for Surgical Simulation and Evaluation. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2021, 130, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, P. Innovating Medical Education Using a Cost Effective and Easy-to-Use Virtual Reality-Based Simulator for Medical Training. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.; Stanislaus, I.; McGahon, C.; Pattabathula, K.; Bryant, S.; Pinto, N.; Jenkins, J.; Meinert, C. Quality Assurance in 3D-Printing: A Dimensional Accuracy Study of Patient-Specific 3D-Printed Vascular Anatomical Models. Front. Med. Technol. 2023, 5, 1097850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Dai, C.; Peng, M.; Wang, D.; Sui, X.; Duan, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Weng, W.; Wang, S.; et al. Artificial Intelligence Driven 3D Reconstruction for Enhanced Lung Surgery Planning. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godin, A.; Molina, J.C.; Morisset, J.; Liberman, M. The Future of Surgical Lung Biopsy: Moving from the Operating Room to the Bronchoscopy Suite. Curr. Chall. Thorac. Surg. 2019, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Mubeen, I.; Ullah, N.; Shah, S.S.U.D.; Khan, B.A.; Zahoor, M.; Ullah, R.; Khan, F.A.; Sultan, M.A. Modern Diagnostic Imaging Technique Applications and Risk Factors in the Medical Field: A Review. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5164970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florkow, M.C.; Willemsen, K.; Mascarenhas, V.V.; Oei, E.H.G.; van Stralen, M.; Seevinck, P.R. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Versus Computed Tomography for Three-Dimensional Bone Imaging of Musculoskeletal Pathologies: A Review. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2022, 56, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCollough, C.H.; Rajiah, P.S. Milestones in CT: Past, Present, and Future. Radiology 2023, 309, e230803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, H.; Tanaka, I.; Fukui, R.; Shen, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Tate, E.; Ueno, E. Current and Novel Imaging Techniques in Coronary CT. Radiographics 2015, 35, 991–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrill, J.; Dabbagh, Z.; Gollub, F.; Hamady, M. Multidetector Computed Tomographic Angiography of the Cardiovascular System. Postgrad. Med. J. 2007, 83, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R.T.; Silva, C.; Cordeiro, M.A.S.; DiPaula, A.; Thompson, D.R.; McCarthy, W.F.; Ichihara, T.; Lima, J.A.C.; Lardo, A.C. Multidetector Computed Tomography Myocardial Perfusion Imaging During Adenosine Stress. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 48, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felipe, V.C.; Barbosa, P.N.V.P.; Chojniak, R.; Bitencourt, A.G.V. Evaluating Multidetector Row CT for Locoregional Staging in Individuals with Locally Advanced Breast Cancer. Radiol. Cardiothorac. Imaging 2025, 7, e240008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabousi, M.; McInnes, M.D.; Salameh, J.-P.; Satkunasingham, J.; Kagoma, Y.K.; Ruo, L.; Meyers, B.M.; Aziz, T.; van der Pol, C.B. MRI vs. CT for the Detection of Liver Metastases in Patients With Pancreatic Carcinoma: A Comparative Diagnostic Test Accuracy Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2021, 53, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, V.; Carbone, M.; Cappelli, C.; Boni, L.; Melfi, F.; Ferrari, M.; Mosca, F.; Pietrabissa, A. Value of Multidetector Computed Tomography Image Segmentation for Preoperative Planning in General Surgery. Surg. Endosc. 2012, 26, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Budovec, J.; Foley, W.D. Prospective and Retrospective ECG Gating for Thoracic CT Angiography: A Comparative Study. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2009, 193, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, T.; Campbell-Washburn, A.E.; Ramasawmy, R.; Yildirim, D.K.; Bruce, C.G.; Grant, L.P.; Stine, A.M.; Kolandaivelu, A.; Herzka, D.A.; Ratnayaka, K.; et al. Interventional Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance: State-of-the-Art. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2023, 25, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumamaru, K.K.; Hoppel, B.E.; Mather, R.T.; Rybicki, F.J. CT Angiography: Current Technology and Clinical Use. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 48, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, S.; Abello Mercado, M.A.; Ucar, F.A.; Kronfeld, A.; Al-Nawas, B.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Booz, C.; Brockmann, M.A.; Othman, A.E. Ultra-High-Resolution CT of the Head and Neck with Deep Learning Reconstruction—Assessment of Image Quality and Radiation Exposure and Intraindividual Comparison with Normal-Resolution CT. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostveen, L.J.; Boedeker, K.L.; Brink, M.; Prokop, M.; de Lange, F.; Sechopoulos, I. Physical Evaluation of an Ultra-High-Resolution CT Scanner. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 2552–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuijf, J.D.; Lima, J.A.C.; Boedeker, K.L.; Takagi, H.; Tanaka, R.; Yoshioka, K.; Arbab-Zadeh, A. CT Imaging with Ultra-High-Resolution: Opportunities for Cardiovascular Imaging in Clinical Practice. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2022, 16, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelmerdine, S.C.; Simcock, I.C.; Hutchinson, J.C.; Aughwane, R.; Melbourne, A.; Nikitichev, D.I.; Ong, J.; Borghi, A.; Cole, G.; Kingham, E.; et al. 3D Printing from Microfocus Computed Tomography (Micro-CT) in Human Specimens: Education and Future Implications. Br. J. Radiol. 2018, 91, 20180306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Gauthier, R.; Olivier, C.; Villanova, J.; Follet, H.; Mitton, D.; Peyrin, F. 3D Quantification of the Lacunocanalicular Network on Human Femoral Diaphysis through Synchrotron Radiation-Based nanoCT. J. Struct. Biol. 2024, 216, 108111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyrin, F.; Dong, P.; Pacureanu, A.; Langer, M. Micro- and Nano-CT for the Study of Bone Ultrastructure. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2014, 12, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandrini, C.; Lombardi, C.; Shearn, A.I.U.; Ordonez, M.V.; Caputo, M.; Presti, F.; Luciani, G.B.; Rossetti, L.; Biglino, G. Three-Dimensional Printing of Fetal Models of Congenital Heart Disease Derived From Microfocus Computed Tomography: A Case Series. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 7, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.E.; Vasilescu, D.M.; Seal, K.A.D.; Keyes, S.D.; Mavrogordato, M.N.; Hogg, J.C.; Sinclair, I.; Warner, J.A.; Hackett, T.-L.; Lackie, P.M. Three Dimensional Imaging of Paraffin Embedded Human Lung Tissue Samples by Micro-Computed Tomography. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M. Assessment of Bone Quality Using Micro-Computed Tomography (Micro-CT) and Synchrotron Micro-CT. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2005, 23, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, C.M.; Zambelli, V.; Botta, G.; Moltrasio, F.; Cattoretti, G.; Lucchini, V.; Fesslova, V.; Cuttin, M.S. Postmortem Microcomputed Tomography (Micro-CT) of Small Fetuses and Hearts. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 44, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.S.; Chunta, J.L.; Robertson, J.M.; Martinez, A.A.; Oliver Wong, C.-Y.; Amin, M.; Wilson, G.D.; Marples, B. MicroPET/CT Imaging of an Orthotopic Model of Human Glioblastoma Multiforme and Evaluation of Pulsed Low-Dose Irradiation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011, 80, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.J.; Francis, R.; Liu, X.; Devine, W.A.; Ramirez, R.; Anderton, S.J.; Wong, L.Y.; Faruque, F.; Gabriel, G.C.; Chung, W.; et al. Microcomputed Tomography Provides High Accuracy Congenital Heart Disease Diagnosis in Neonatal and Fetal Mice. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 6, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, J.C.; Barrett, H.; Ramsey, A.T.; Haig, I.G.; Guy, A.; Sebire, N.J.; Arthurs, O.J. Virtual Pathological Examination of the Human Fetal Kidney Using Micro-CT. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 48, 663–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.C.; Shelmerdine, S.C.; Simcock, I.C.; Sebire, N.J.; Arthurs, O.J. Early Clinical Applications for Imaging at Microscopic Detail: Microfocus Computed Tomography (Micro-CT). Br. J. Radiol. 2017, 90, 20170113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampschulte, M.; Langheinirch, A.C.; Sender, J.; Litzlbauer, H.D.; Althöhn, U.; Schwab, J.D.; Alejandre-Lafont, E.; Martels, G.; Krombach, G.A. Nano-Computed Tomography: Technique and Applications. RöFo-Fortschr. Geb. Rontgenstr. Nuklearmed 2016, 188, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury, B.M.; Bigelow, E.M.R.; Smith, L.M.; Schlecht, S.H.; Scheller, E.L.; Andarawis-Puri, N.; Jepsen, K.J. The Use of Nano-Computed Tomography to Enhance Musculoskeletal Research. Connect. Tissue Res. 2015, 56, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsugami, F.; Higaki, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Honda, Y.; Awai, K. Dual-Energy CT: Minimal Essentials for Radiologists. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2022, 40, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naruto, N.; Itoh, T.; Noguchi, K. Dual Energy Computed Tomography for the Head. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2018, 36, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Kikano, E.G.; Bera, K.; Baruah, D.; Saboo, S.S.; Lennartz, S.; Hokamp, N.G.; Gholamrezanezhad, A.; Gilkeson, R.C.; Laukamp, K.R. Dual Energy Imaging in Cardiothoracic Pathologies: A Primer for Radiologists and Clinicians. Eur. J. Radiol. Open 2021, 8, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, J.R.; Burrows, C.; Jerome, S.; Ribeiro, L.; Larrazabal, R.; Gupta, R.; Yu, E. Dual Energy CT: A Step Ahead in Brain and Spine Imaging. Br. J. Radiol. 2020, 93, 20190872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, G.P.; Rezaeifar, B.; Lackner, N.; Haanen, B.; Reniers, B.; Verhaegen, F. Dual-Energy CT Evaluation of 3D Printed Materials for Radiotherapy Applications. Phys. Med. Biol. 2023, 68, 035005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, T.; Liao, R.; Medrano, M.; Politte, D.G.; Williamson, J.F.; O’Sullivan, J.A. MB-DECTNet: A Model-Based Unrolling Network for Accurate 3D Dual-Energy CT Reconstruction from Clinically Acquired Helical Scans. Phys. Med. Biol. 2023, 68, 245009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhong, X.; Hu, S.; Dorn, S.; Kachelrieß, M.; Lell, M.; Maier, A. Automatic Multi-Organ Segmentation in Dual-Energy CT (DECT) with Dedicated 3D Fully Convolutional DECT Networks. Med. Phys. 2020, 47, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodda, V.C.; Kuruguntla, L.; Ravichandran, N.K.; Lee, K.-S.; Sollapur, R.; Damodaran, M.; Kumar, R.; Anilkumar, N.; Itapu, S.; Kumar, M.; et al. Overview of Photon-Counted Three-Dimensional Imaging and Related Applications. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 31211–31234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greffier, J.; Viry, A.; Robert, A.; Khorsi, M.; Si-Mohamed, S. Photon-Counting CT Systems: A Technical Review of Current Clinical Possibilities. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2025, 106, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopp, F.K.; Daerr, H.; Si-Mohamed, S.; Sauter, A.P.; Ehn, S.; Fingerle, A.A.; Brendel, B.; Pfeiffer, F.; Roessl, E.; Rummeny, E.J.; et al. Evaluation of a Preclinical Photon-Counting CT Prototype for Pulmonary Imaging. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, A.; Maffei, E.; Clemente, A.; De Gori, C.; Occhipinti, M.; Positano, V.; Berti, S.; La Grutta, L.; Saba, L.; Cau, R.; et al. Spectral Photon-Counting Computed Tomography: Technical Principles and Applications in the Assessment of Cardiovascular Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckhorn, C.B.; Moya-Mendez, M.E.; Aiduk, M.; Thornton, S.; Medina, C.K.; Louie, A.D.; Overbey, D.; Cao, J.Y.; Tracy, E.T. Use of Photon-Counting CT and Three-Dimensional Printing for an Intra-Thoracic Retained Ballistic Fragment in a 9-Year-Old. Pediatr. Radiol. 2025, 55, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugauer, F.; Wetzl, J. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. In Medical Imaging Systems: An Introductory Guide; Maier, A., Steidl, S., Christlein, V., Hornegger, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-96519-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Liu, F.; Li, S.; Luo, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, W.; Feiweier, T.; Xu, J.; Bao, H.; Shi, D.; et al. Comparison of MR Cytometry Methods in Predicting Immunohistochemical Factor Status and Molecular Subtypes of Breast Cancer. Radiol. Oncol. 2025, 59, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, C. Brain Tumor Detection Based on a Novel and High-Quality Prediction of the Tumor Pixel Distributions. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 172, 108196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejia, E.; Sweeney, S.; Zablah, J.E. Virtual 3D Reconstruction of Complex Congenital Cardiac Anatomy from 3D Rotational Angiography. 3D Print. Med. 2025, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hougaard, M.; Hansen, H.S.; Thayssen, P.; Antonsen, L.; Jensen, L.O. Uncovered Culprit Plaque Ruptures in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Assessed by Optical Coherence Tomography and Intravascular Ultrasound with iMap. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, B.F.; Pressman, P. Dynamic Cardiac Imaging as a Preclinical Cardiovascular Pathophysiology Teaching Aid: Facta Non Verba. Sage Open Med. 2024, 12, 20503121231225322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odille, F.; Bustin, A.; Liu, S.; Chen, B.; Vuissoz, P.-A.; Felblinger, J.; Bonnemains, L. Isotropic 3D Cardiac Cine MRI Allows Efficient Sparse Segmentation Strategies Based on 3D Surface Reconstruction. Magn. Reson. Med. 2018, 79, 2665–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.L.; Maki, J.H.; Prince, M.R. 3D Contrast-enhanced MR Angiography. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2007, 25, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zun, Z.; Hargreaves, B.A.; Rosenberg, J.; Zaharchuk, G. Improved Multislice Perfusion Imaging with Velocity-Selective Arterial Spin Labeling. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2015, 41, 1422–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Lu, J.P.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Jin, A.G.; Wang, J.; Tian, J.M. Visceral Artery Aneurysms: Evaluation Using 3D Contrast-Enhanced MR Angiography. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2008, 191, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maj, E.; Cieszanowski, A.; Rowiński, O.; Wojtaszek, M.; Szostek, M.; Tworus, R. Time-Resolved Contrast-Enhanced MR Angiography: Value of Hemodynamic Information in the Assessment of Vascular Diseases. Pol. J. Radiol. 2010, 75, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Aydıngöz, Ü.; Yıldız, A.E.; Ergen, F.B. Zero Echo Time Musculoskeletal MRI: Technique, Optimization, Applications, and Pitfalls. Radiographics 2022, 42, 1398–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, P.E.Z.; Han, M.; Krug, R.; Jakary, A.; Nelson, S.J.; Vigneron, D.B.; Henry, R.G.; McKinnon, G.; Kelley, D.A.C. Ultrashort Echo Time and Zero Echo Time MRI at 7T. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 2016, 29, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Park, J.E.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, N.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, Y.-H.; Kim, J.H. Spatiotemporal Habitats from Multiparametric Physiologic MRI Distinguish Tumor Progression from Treatment-Related Change in Post-Treatment Glioblastoma. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 6374–6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, B.-T.D.; Kamona, N.; Kim, Y.; Ng, J.J.; Jones, B.C.; Wehrli, F.W.; Song, H.K.; Bartlett, S.P.; Lee, H.; Rajapakse, C.S. Three Contrasts in 3 Min: Rapid, High-Resolution, and Bone-Selective UTE MRI for Craniofacial Imaging with Automated Deep-Learning Skull Segmentation. Magn. Reson. Med. 2025, 93, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bücking, T.M.; Hill, E.R.; Robertson, J.L.; Maneas, E.; Plumb, A.A.; Nikitichev, D.I. From Medical Imaging Data to 3D Printed Anatomical Models. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzelbağ, A.N.; Baş, S.; Toprak, M.H.H.; Kangel, D.; Çoban, Ş.; Sağlam, S.; Öztürk, E. Transforming Cardiac Imaging: Can CT Angiography Replace Interventional Angiography in Tetralogy of Fallot? J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Rhee, D.J.; Ger, R.; Layman, R.; Yang, J.; Cardenas, C.E.; Court, L.E. Impact of Slice Thickness, Pixel Size, and CT Dose on the Performance of Automatic Contouring Algorithms. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2021, 22, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onken, M.; Eichelberg, M.; Riesmeier, J.; Jensch, P. Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine. In Biomedical Image Processing; Deserno, T.M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 427–454. ISBN 978-3-642-15816-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, K.; Dort, J.C.; Sutherland, G.R.; Chan, S. Evaluation of Software Tools for Segmentation of Temporal Bone Anatomy. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2016, 220, 130–133. [Google Scholar]

- Virzì, A.; Muller, C.O.; Marret, J.-B.; Mille, E.; Berteloot, L.; Grévent, D.; Boddaert, N.; Gori, P.; Sarnacki, S.; Bloch, I. Comprehensive Review of 3D Segmentation Software Tools for MRI Usable for Pelvic Surgery Planning. J. Digit. Imaging 2020, 33, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsiushevich, K.; Belvedere, C.; Leardini, A.; Durante, S. Quantitative Comparison of Freeware Software for Bone Mesh from DICOM Files. J. Biomech. 2019, 84, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queisner, M.; Eisenträger, K. Surgical Planning in Virtual Reality: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Imaging 2024, 11, 062603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, M.; Buchbinder, D.; Aniceto, G.S.; Mast, G. Patient-Specific Solutions for Cranial, Midface, and Mandible Reconstruction Following Ablative Surgery: Expert Opinion and a Consensus on the Guidelines and Workflow. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2025, 18, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Faraci, A.; Bello, F. Segmentation and Generation of Patient-Specific 3D Models of Anatomy for Surgical Simulation. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2004, 98, 360–362. [Google Scholar]

- Wendo, K.; Behets, C.; Barbier, O.; Herman, B.; Schubert, T.; Raucent, B.; Olszewski, R. Dimensional Accuracy Assessment of Medical Anatomical Models Produced by Hospital-Based Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printer. J. Imaging 2025, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, K.M.; Morabito, K.E.; Depew, P.K. 3D Printed Testing Aids for Radiographic Quality Control. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2019, 20, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, K.M.; Aslan, C.; Ordway, N.; Diallo, D.; Tillapaugh-Fay, G.; Soman, P. Factors Affecting Dimensional Accuracy of 3-D Printed Anatomical Structures Derived from CT Data. J. Digit. Imaging 2015, 28, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudia, C.; Farida, C.; Guy, G.; Marie-Claude, M.; Carl-Eric, A. Quantitative Evaluation of an Automatic Segmentation Method for 3D Reconstruction of Intervertebral Scoliotic Disks from MR Images. BMC Med. Imaging 2012, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juergensen, L.; Rischen, R.; Hasselmann, J.; Toennemann, M.; Pollmanns, A.; Gosheger, G.; Schulze, M. Insights into Geometric Deviations of Medical 3d-Printing: A Phantom Study Utilizing Error Propagation Analysis. 3D Print. Med. 2024, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilesanmi, A.E.; Ilesanmi, T.O.; Ajayi, B.O. Reviewing 3D Convolutional Neural Network Approaches for Medical Image Segmentation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Wu, Y.; Chang, H.; Su, F.T.; Liao, H.; Tseng, W.; Liao, C.; Lai, F.; Hsu, F.; Xiao, F. Deep Learning-Based Segmentation of Various Brain Lesions for Radiosurgery. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzino, S.; Luca, T.; Castorina, M.; Puleo, S.; Castorina, S. Current Trends and Emerging Themes in Utilizing Artificial Intelligence to Enhance Anatomical Diagnostic Accuracy and Efficiency in Radiotherapy. Prog. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 7, 032002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayed, M.E.; Islam, S.M.S.; Niha, S.I.; Jim, J.R.; Kabir, M.M.; Mridha, M.F. Deep Learning for Medical Image Segmentation: State-of-the-Art Advancements and Challenges. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2024, 47, 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Quan, R.; Xu, W.; Huang, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, F. Advances in Medical Image Segmentation: A Comprehensive Review of Traditional, Deep Learning and Hybrid Approaches. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, L.; Yang, H. Accuracy and Efficiency of an Artificial Intelligence-Based Three-Dimensional Reconstruction System in Thoracic Surgery. EBioMedicine 2023, 87, 104422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, H.M.S.S.; Yasakethu, S.L.P.; Madusanka, N.; Yi, M.; Lee, B.-I. Comparative Analysis of Deep Learning Architectures for Macular Hole Segmentation in OCT Images: A Performance Evaluation of U-Net Variants. J. Imaging 2025, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punn, N.S.; Agarwal, S. Modality Specific U-Net Variants for Biomedical Image Segmentation: A Survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 5845–5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, R.; Abid, F.; Rasheed, J.; Osman, O.; Alsubai, S. Optimal Res-UNET Architecture with Deep Supervision for Tumor Segmentation. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1593016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayalakshmi, S.; Manoharan, J.S.; Nivetha, B.; Sathiya, A. Multi-Task Deep Learning Framework Combining CNN: Vision Transformers and PSO for Accurate Diabetic Retinopathy Diagnosis and Lesion Localization. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamdouh, D.; Attia, M.; Osama, M.; Mohamed, N.; Lotfy, A.; Arafa, T.; Rashed, E.A.; Khoriba, G. Advancements in Radiology Report Generation: A Comprehensive Analysis. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adiga, S.; Dolz, J.; Lombaert, H. Anatomically-Aware Uncertainty for Semi-Supervised Image Segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 2024, 91, 103011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fave, X.; Cook, M.; Frederick, A.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Fried, D.; Stingo, F.; Court, L. Preliminary Investigation into Sources of Uncertainty in Quantitative Imaging Features. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2015, 44, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weikert, T.; Cyriac, J.; Yang, S.; Nesic, I.; Parmar, V.; Stieltjes, B. A Practical Guide to Artificial Intelligence-Based Image Analysis in Radiology. Investig. Radiol. 2020, 55, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Diao, K.; Wen, Y.; Shuai, T.; You, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liao, K.; Lu, C.; Yu, J.; He, Y.; et al. High-Strength Deep Learning Image Reconstruction in Coronary CT Angiography at 70-kVp Tube Voltage Significantly Improves Image Quality and Reduces Both Radiation and Contrast Doses. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 2912–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Parvinian, A.; Adamo, D.; Welch, B.; Callstrom, M.; Ren, L.; Missert, A.; Favazza, C.P. Deep Convolutional-Neural-Network-Based Metal Artifact Reduction for CT-Guided Interventional Oncology Procedures (MARIO). Med. Phys. 2024, 51, 4231–4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koetzier, L.R.; Mastrodicasa, D.; Szczykutowicz, T.P. Deep Learning Image Reconstruction for CT: Technical Principles and Clinical Prospects. Radiology 2023, 306, e221257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabi, H.; Zaidi, H. Deep Learning–Based Metal Artefact Reduction in PET/CT Imaging. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 6384–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomase, V.S.; Ghatule, A.P.; Sharma, R.; Sardana, S. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Data Integrity, Transparency, and Security in Technology-Enabled Improvements to Clinical Trial Data Management in Healthcare. Rev. Recent. Clin. Trials 2025, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Lee, M.; Lee, Y.; Kim, K.; Kim, T. Artificial Intelligence-Powered Quality Assurance: Transforming Diagnostics, Surgery, and Patient Care—Innovations, Limitations, and Future Directions. Life 2025, 15, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.M.; Yeap, P.L.; Ong, A.L.K.; Tuan, J.K.L.; Lew, W.S.; Lee, J.C.L.; Tan, H.Q. Machine Learning Prediction of Dice Similarity Coefficient for Validation of Deformable Image Registration. Intell.-Based Med. 2024, 10, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Jung, J.J. Deep Learning for Anomaly Detection in Multivariate Time Series: Approaches, Applications, and Challenges. Inf. Fusion 2023, 91, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, T.; Ma, Y.; Kanawati, A.; Dillon, O.; Baer, K.; Gang, G.; Stayman, J. Universal Non-Circular Cone Beam CT Orbits for Metal Artifact Reduction Imaging during Image-Guided Procedures. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, H.; Wang, Z.; Guo, M.; Peng, K.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, L.; Fan, B. Metal Artifact Reduction Combined with Deep Learning Image Reconstruction Algorithm for CT Image Quality Optimization: A Phantom Study. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasserthal, J.; Breit, H.-C.; Meyer, M.T.; Pradella, M.; Hinck, D.; Sauter, A.W.; Heye, T.; Boll, D.T.; Cyriac, J.; Yang, S.; et al. TotalSegmentator: Robust Segmentation of 104 Anatomic Structures in CT Images. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, e230024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikhita; Bannur, D.; Cerdas, M.G.; Saeed, A.Z.; Imam, B.; Thandi, R.S.; Anusha, H.C.; Reddy, P.; Ali, R.; Nikhita, N.; et al. Efficiency of Artificial Intelligence in Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of Medical Imaging. Cureus 2025, 17, e96580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Sluis, J.; Noordzij, W.; de Vries, E.G.E.; Kok, I.C.; de Groot, D.J.A.; Jalving, M.; Lub-de Hooge, M.N.; Brouwers, A.H.; Boellaard, R. Manual Versus Artificial Intelligence-Based Segmentations as a Pre-Processing Step in Whole-Body PET Dosimetry Calculations. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2023, 25, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Sounderajah, V.; Martin, G.; Ting, D.S.W.; Karthikesalingam, A.; King, D.; Ashrafian, H.; Darzi, A. Diagnostic Accuracy of Deep Learning in Medical Imaging: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. npj Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, W.; Kang, J.; Wu, W.; Qi, M.; Zhou, L.; Ma, J.; Xu, Y. PND-Net: Physics-Inspired Non-Local Dual-Domain Network for Metal Artifact Reduction. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 2125–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Liu, M. Domain Adaptation for Medical Image Analysis: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 69, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. 3D Printing Applications for Healthcare Research and Development. Glob. Health J. 2022, 6, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Dash, M.; Chakraborty, R.; Lukman, H.J.; Kumar, P.; Hassan, S.; Mehboob, H.; Singh, H.; Nanda, H.S. Engineering Considerations in the Design of Tissue Specific Bioink for 3D Bioprinting Applications. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 13, 93–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi Soufivand, A.; Faber, J.; Hinrichsen, J.; Budday, S. Multilayer 3D Bioprinting and Complex Mechanical Properties of Alginate-Gelatin Mesostructures. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.; Patel, A.; Sohn, M.K. Multi-Material and Multidimensional Bioprinting in Regenerative Medicine and Cancer Research. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, e2500475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Ariff, A.; Ghersi, G. Comparative Analysis of the Mechanical Properties of FDM and SLA 3D-Printed Materials for Medical Education. SAGE Open Med. 2025, 13, 25165984251364689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storck, J.L.; Ehrmann, G.; Güth, U.; Uthoff, J.; Homburg, S.V.; Blachowicz, T.; Ehrmann, A. Investigation of Low-Cost FDM-Printed Polymers for Elevated-Temperature Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frunzaverde, D.; Cojocaru, V.; Bacescu, N.; Ciubotariu, C.-R.; Miclosina, C.-O.; Turiac, R.R.; Marginean, G. The Influence of the Layer Height and the Filament Color on the Dimensional Accuracy and the Tensile Strength of FDM-Printed PLA Specimens. Polymers 2023, 15, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.-J.; Lee, H.; Cho, K.-J. 3D Printing with a 3D Printed Digital Material Filament for Programming Functional Gradients. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Equbal, A.; Murmu, R.; Kumar, V.; Equbal, M.A.; Equbal, A.; Murmu, R.; Kumar, V.; Equbal, M.A. A Recent Review on Advancements in Dimensional Accuracy in Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) 3D Printing. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2024, 11, 950–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Kalva, S.N.; Koc, M. Advancements in 3D Printing Techniques for Biomedical Applications: A Comprehensive Review of Materials Consideration, Post Processing, Applications, and Challenges. Discov. Mater. 2024, 4, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantaros, A.; Petrescu, F.I.T.; Abdoli, H.; Diegel, O.; Chan, S.; Iliescu, M.; Ganetsos, T.; Munteanu, I.S.; Ungureanu, L.M. Additive Manufacturing for Surgical Planning and Education: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husna, A.; Ashrafi, S.; Tomal, A.A.; Tuli, N.T.; Bin Rashid, A. Recent Advancements in Stereolithography (SLA) and Their Optimization of Process Parameters for Sustainable Manufacturing. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 7, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maines, E.M.; Porwal, M.K.; Ellison, C.J.; Reineke, T.M. Sustainable Advances in SLA/DLP 3D Printing Materials and Processes. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 6863–6897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuram, N.; Sriram Madhav, P.; Keerthi Vasan, D.; Mohan, M.E.; Prajeeth, G. A Review of Recent Literatures in Poly Jet Printing Process. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 68, 1906–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majca-Nowak, N.; Pyrzanowski, P. The Analysis of Mechanical Properties and Geometric Accuracy in Specimens Printed in Material Jetting Technology. Materials 2023, 16, 3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, Z.É.; Kovács, Z.I.; Vass, A.F.; Borbély, J.; Márton, K. Evaluation of the Dimensional Stability of 3D-Printed Dental Casts. J. Dent. 2024, 151, 105431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Collado, A.; Blanco, J.M.; Gupta, M.K.; Dorado-Vicente, R. Advances in Polymers Based Multi-Material Additive-Manufacturing Techniques: State-of-Art Review on Properties and Applications. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 50, 102577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, Y.; Rothweiler, P.; Erdman, A.G. Mechanical Characterization and Feasibility Analysis of PolyJetTM Materials in Tissue-Mimicking Applications. Machines 2025, 13, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.H.; Oberoi, G.; Unger, E.; Janjic, K.; Rohringer, S.; Heber, S.; Agis, H.; Schedle, A.; Kiss, H.; Podesser, B.K.; et al. Medical 3D Printing with Polyjet Technology: Effect of Material Type and Printing Orientation on Printability, Surface Structure and Cytotoxicity. 3D Print. Med. 2023, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Guo, S.; Ravichandran, D.; Ramanathan, A.; Sobczak, M.T.; Sacco, A.F.; Patil, D.; Thummalapalli, S.V.; Pulido, T.V.; Lancaster, J.N.; et al. 3D-Printed Polymeric Biomaterials for Health Applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, 2402571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emir, F.; Ayyildiz, S. Accuracy Evaluation of Complete-Arch Models Manufactured by Three Different 3D Printing Technologies: A Three-Dimensional Analysis. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2021, 65, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modular Digital and 3D-Printed Dental Models with Applicability in Dental Education. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/59/1/116 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- The Application and Challenge of Binder Jet 3D Printing Technology in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4923/14/12/2589 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Hong, X.; Han, X.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, A. Binder Jet 3D Printing of Compound LEV-PN Dispersible Tablets: An Innovative Approach for Fabricating Drug Systems with Multicompartmental Structures. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Xu, Y.; Cao, L.; Xiong, L.; Shang, D.; Cong, Y.; Zhao, D.; Wei, X.; Li, J.; Fu, D.; et al. Mechanical and Biological Properties of 3D Printed Bone Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1545693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiran, S.; Nourbakhsh, M.S.; Setayeshmehr, M.; Poursamar, S.A.; Rafienia, M. Improvement in Surface Morphology and Mechanical Properties of the Polycaprolactone/Hydroxyapatite/Graphene Oxide Scaffold: 3D Printing—Salt Leaching Method. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 8731–8744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Pescara, T.; Gambelli, A.M.; Gaggia, F.; Asthana, A.; Perrier, Q.; Basta, G.; Moretti, M.; Senin, N.; Rossi, F.; et al. Biomaterials for Extrusion-Based Bioprinting and Biomedical Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1393641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Shahriar, M.; Xu, H.; Xu, C. Cell-Laden Bioink Circulation-Assisted Inkjet-Based Bioprinting to Mitigate Cell Sedimentation and Aggregation. Biofabrication 2022, 14, e96580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natural and Synthetic Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting—Khoeini—2021—Advanced NanoBiomed Research—Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://advanced.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/anbr.202000097 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Schwab, A.; Levato, R.; D’Este, M.; Piluso, S.; Eglin, D.; Malda, J. Printability and Shape Fidelity of Bioinks in 3D Bioprinting. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 11028–11055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namli, I.; Gupta, D.; Singh, Y.P.; Datta, P.; Rizwan, M.; Baykara, M.; Ozbolat, I.T. Progressive Insights into 3D Bioprinting for Corneal Tissue Restoration. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 2025, e03372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Peregrino, V.M.; Tenorio-Barajas, A.Y.; Mendoza-Barrera, C.O.; Román-Doval, J.; Lavariega-Sumano, E.F.; Torres-Arellanes, S.P.; Román-Doval, R. 3D Printing for Tissue Engineering: Printing Techniques, Biomaterials, Challenges, and the Emerging Role of 4D Bioprinting. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaksa, L.; Ates, G.; Heller, S. Development of a Multi-Material 3D Printer for Functional Anatomic Models. Int. J. Bioprint. 2021, 7, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.A.S.; Rabbi, M.S.; Ahmed, R.U.; Billah, M.M. Biodegradable Natural Polymers and Fibers for 3D Printing: A Holistic Perspective on Processing, Characterization, and Advanced Applications. Clean. Mater. 2024, 14, 100275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatamikia, S.; Jaksa, L.; Kronreif, G.; Birkfellner, W.; Kettenbach, J.; Buschmann, M.; Lorenz, A. Silicone Phantoms Fabricated with Multi-Material Extrusion 3D Printing Technology Mimicking Imaging Properties of Soft Tissues in CT. Z. Für Med. Phys. 2025, 35, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatamikia, S.; Zaric, O.; Jaksa, L.; Schwarzhans, F.; Trattnig, S.; Fitzek, S.; Kronreif, G.; Woitek, R.; Lorenz, A. Evaluation of 3D-Printed Silicone Phantoms with Controllable MRI Signal Properties. Int. J. Bioprinting 2025, 11, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Gao, Q.; Fu, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, J.; Sun, Y.; He, Y. Multimaterial 3D Printing of Highly Stretchable Silicone Elastomers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 23573–23583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.V.; Atala, A. 3D Bioprinting of Tissues and Organs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gungor-Ozkerim, P.S.; Inci, I.; Zhang, Y.S.; Khademhosseini, A.; Dokmeci, M.R. Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting: An Overview. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6, 915–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.S.; Duchamp, M.; Oklu, R.; Ellisen, L.W.; Langer, R.; Khademhosseini, A. Bioprinting the Cancer Microenvironment. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 1710–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Nowicki, M.; Fisher, J.P.; Zhang, L.G. 3D Bioprinting for Organ Regeneration. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudapati, H.; Dey, M.; Ozbolat, I. A Comprehensive Review on Droplet-Based Bioprinting: Past, Present and Future. Biomaterials 2016, 102, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matai, I.; Kaur, G.; Seyedsalehi, A.; McClinton, A.; Laurencin, C.T. Progress in 3D Bioprinting Technology for Tissue/Organ Regenerative Engineering. Biomaterials 2020, 226, 119536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unagolla, J.M.; Jayasuriya, A.C. Hydrogel-Based 3D Bioprinting: A Comprehensive Review on Cell-Laden Hydrogels, Bioink Formulations, and Future Perspectives. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 18, 100479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, J.K.; Park, H.S.; Ko, D.; Yang, H.-B.; Kim, H.-Y.; Yoon, H.B. Application of Additional Three-Dimensional Materials for Education in Pediatric Anatomy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, I.; Wong, Y.H.; Yeong, C.H.; Abdul Aziz, Y.F.; Md Sari, N.A.; Hashim, S.A.; Sun, Z. Quantitative and Qualitative Comparison of Low- and High-Cost 3D-Printed Heart Models. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2019, 9, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, S.; Li, M. The Role of Three-Dimensional Printed Models of Skull in Anatomy Teaching: A Randomized Controlled Trail. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, M.Y.; Aidoo-Micah, M.; Zhou, Y. Spatial Ability and 3D Model Colour-Coding Affect Anatomy Learning Performance. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidanza, A.; Caggiari, G.; Di Petrillo, F.; Fiori, E.; Momoli, A.; Logroscino, G. Three-Dimensional Printed Models Can Reduce Costs and Surgical Time for Complex Proximal Humeral Fractures: Preoperative Planning, Patient Satisfaction, and Improved Resident Skills. J. Orthop. Traumatol. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Orthop. Traumatol. 2024, 25, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Yi, K.; Shi, Y. Orthopedic Trainees’ Perception of the Educational Utility of Patient-Specific 3D-Printed Anatomical Models: A Questionnaire-Based Observational Study. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2025, 16, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, J.B.; Park, C.Y.; Lopez, A. Development, Implementation, and Perceptions of a 3D-Printed Human Skull for Dental Education. J. Dent. Educ. 2024, 88, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolder, D.; Blazuk-Fortak, A.; Góra, T.; Michalska, A.; Kaczmarek, P.; Świercz, G. The Role of Three-Dimensional Printed Models of Fetuses Obtained from Ultrasonographic Examinations in Obstetrics: Clinical and Educational Aspects. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2025, 312, 114538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Ma, Q.; Zhao, X.; Pan, G.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, B.; Xue, Y.; Li, D.; Lu, B. Feasibility Analysis of 3D Printing With Prenatal Ultrasound for the Diagnosis of Fetal Abnormalities. J. Ultrasound Med. 2022, 41, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neijhoft, J.; Henrich, D.; Mörs, K.; Marzi, I.; Janko, M. Visualization of Complicated Fractures by 3D-Printed Models for Teaching and Surgery: Hands-on Transitional Fractures of the Ankle. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2022, 48, 3923–3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaila, E.M.; Negri, S.; Zardini, A.; Bizzotto, N.; Maluta, T.; Rossignoli, C.; Magnan, B. Value of Three-Dimensional Printing of Fractures in Orthopaedic Trauma Surgery. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 48, 0300060519887299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, A.; Naaz, S.; Patra, A.; Ravi, K.S.; Khanal, L. Effectiveness of 3D-Printed Models Prepared from Radiological Data for Anatomy Education: A Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis of 22 Randomized, Controlled, Crossover Trials. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2022, 11, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.; Mehra, S.; Pandya, A. Randomised Controlled Trial: Role of Virtual Interactive 3-Dimensional Models in Anatomical and Medical Education. J. Vis. Commun. Med. 2024, 47, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavvadia, E.-M.; Katsoula, I.; Angelis, S.; Filippou, D. The Anatomage Table: A Promising Alternative in Anatomy Education. Cureus 2023, 15, e43047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsky, B.M.; Panicker, S.; Chaudhary, N.; Gemmete, J.J.; Wilseck, Z.M.; Lin, L. The Potential of 3D Models and Augmented Reality in Teaching Cross-Sectional Radiology. Med. Teach. 2023, 45, 1108–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paymard, M.; Naderian, H.; Hassani Bafrani, H.; Azami Tameh, A.; Mirsafi Niasar, M.; Rahimi, H.; Hosseini, H.S.; Rafat, A. An Evaluation of the Use of 3D-Printed Anatomical Models in Anatomy Education. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2025, 47, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratz, G.; Sridharan, P.S.; Yong, V.; Tatsuoka, C.; Griswold, M.A.; Wish-Baratz, S. Comparing Learning Retention in Medical Students Using Mixed-Reality to Supplement Dissection: A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2022, 13, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, M.F.; Yurtsever, A.Z.; Açıkgöz, F.; Başgut, B.; Mavi, B.; Ertuç, E.; Sevim, S.; Oruk, T.; Kıyak, Y.S.; Peker, T. A New Classmate in Anatomy Education: 3D Anatomical Modeling Medical Students’ Engagement on Learning through Self-prepared Anatomical Models. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2025, 18, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenta, E.W.; Alsheghri, A. Exploring 4D Printing for Biomedical Applications: Advancements, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Bioprinting 2025, 50, e00436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Arya, S.; Gupta, V.; Furukawa, H.; Khosla, A. 4D Printing: Fundamentals, Materials, Applications and Challenges. Polymer 2021, 228, 123926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Chen, S.; Ma, J.; Dong, C.; Banerjee, H.; Laperrousaz, S.; Piveteau, P.-L.; Meng, Y.; Leng, J.; Sorin, F. Multimaterial Shape Memory Polymer Fibers for Advanced Drug Release Applications. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2025, 7, 1576–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, V.; Agarwal, P.; Kasturi, M.; Varadharajan, S.; Devi, E.S.; Vasanthan, K.S. Transformative Bioprinting: 4D Printing and Its Role in the Evolution of Engineering and Personalized Medicine. Discov. Nano 2025, 20, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faizan Siddiqui, M.; Jabeen, S.; Alwazzan, A.; Vacca, S.; Dalal, L.; Al-Haddad, B.; Jaber, A.; Ballout, F.F.; Abou Zeid, H.K.; Haydamous, J.; et al. Integration of Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Extended Reality in Healthcare and Medical Education: A Glimpse into the Emerging Horizon in LMICs—A Systematic Review. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2025, 12, 23821205251342315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urlings, J.; de Jong, G.; Maal, T.; Henssen, D. Views on Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and 3D Printing in Modern Medicine and Education: A Qualitative Exploration of Expert Opinion. J. Digit. Imaging 2023, 36, 1930–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Technology | Layer Thickness (μm) | Precision/Accuracy | Material Options | Multi- Material Capability | Anatomical Applications | Post-Processing | Key Limitations | Educational Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDM (Fused Deposition Modeling) | 50–300 | ±0.5% (desktop), ±0.15% (industrial) | PLA, PETG, TPU, flexible materials | Limited (dual extrusion) | Rigid structures, skeletal models, low-cost production | Minimal to moderate | Lower surface quality, visible layer stepping | Excellent (cost-effective, color variety) |

| SLA (Stereolithography) | 20 | ±0.5% (desktop), ±0.15% (industrial) | Standard & flexible resins, biocompatible | No (single resin tank) | High-detail vascular/cardiac, precise anatomical features | Moderate (washing, UV curing) | Potential warping of unsupported spans, UV sensitivity | Excellent (high-detail, realistic finishes) |

| PolyJet (Material Jetting) | 16 | ±0.04–0.2 mm RMS | Rigid & elastic photopolymers, multiple colors | Yes (simultaneous hard & soft) | Multi-tissue simulation, color-differentiation, complex geometries | Minimal (water jet or manual removal) | High economic constraints limit accessibility | Superior (multi-material, tissue-specific properties) |

| DLP (Digital Light Processing) | 46.2 (trueness) | 46.2 trueness, 43.6 precision (μm) | Dental photoresins, limited elastomeric | No (single material) | Dental, orthodontic, small-scale models | Moderate (surface cleaning) | Limited material variety, small build platforms | Good (high precision for small models) |

| Binder Jetting | 80–100 | Surface finish rough, ±0.8–1.2 mm | Powders (HAP, Ca-P, pharmaceuticals) | Limited (powder mixture) | Bone implants (HAP/Ca-P), patient-specific porosity | Extensive (days to weeks infiltration/sintering) | Delicate green-state, long processing, rough finish, waste management | Limited (for anatomical education) |

| Inkjet Bioprinting | Variable (piezoelectric) | Piezoelectric precision variable | Natural polymers (alginate, gelatin, collagen), synthetic (PEG, PCL, PLGA) | Cell-laden only | Tissue engineering, not suitable for anatomical education | Extensive (sterile culture, physiological media) | Requires sterile conditions, incompatible with anatomical teaching, cost-prohibitive | Not applicable (tissue engineering only) |

| Learning Domain | Study Design | Sample Size | Outcome Metric | Results | Significative | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac Anatomy | Blinded RCT | n = 52 | Post-test scores | 3D: 60.83% vs. Cadaver: 44.81% vs. Combined: 44.62% | p = 0.010 | [20] |

| Spatial Visualization | Meta-analysis | n = 2492 (27 studies) | Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) | 3D vs. Traditional: SMD 0.72 [95% CI: 0.32–1.13]; 3D vs. 2D: SMD 0.93 [95% CI: 0.49–1.37] | p < 0.001 | [22] |

| Cranial/Skeletal Anatomy | RCT | n = 79 | Structural recognition | 3D: 31.5 [IQR:29–36] vs. Cadaver: 29.5 [IQR:25–33] | p = 0.044 | [177] |

| Color-Coded Learning | RCT | n = 102 | Knowledge retention | 78.3 ± 6.1 vs. Monochromatic: 71.2 ± 7.3 | p < 0.001 | [178] |

| Fracture Surgery Planning | Prospective RCT | n = 40 | Operative time reduction | 75.47 ± 9.06 min (3D-planned) vs. 88.55 ± 11.20 min (conventional) | p = 0.0002 | [179] |

| Orthopedic Resident Satisfaction | Survey | n = 76 | Educational benefit rating | 85.6% improved understanding; Physical manipulation: 8.1 ± 0.9/10 | — | [180] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Castorina, S.; Puleo, S.; Crescimanno, C.; Pezzino, S. Advanced 3D Modeling and Bioprinting of Human Anatomical Structures: A Novel Approach for Medical Education Enhancement. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010005

Castorina S, Puleo S, Crescimanno C, Pezzino S. Advanced 3D Modeling and Bioprinting of Human Anatomical Structures: A Novel Approach for Medical Education Enhancement. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastorina, Sergio, Stefano Puleo, Caterina Crescimanno, and Salvatore Pezzino. 2026. "Advanced 3D Modeling and Bioprinting of Human Anatomical Structures: A Novel Approach for Medical Education Enhancement" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010005

APA StyleCastorina, S., Puleo, S., Crescimanno, C., & Pezzino, S. (2026). Advanced 3D Modeling and Bioprinting of Human Anatomical Structures: A Novel Approach for Medical Education Enhancement. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010005